#native american poets

Text

"I came into this world already scarred by loss on both sides of my family. My Indigenous side; my European side. My father and my mother were the kind of damaged people who should never have had children. But of course, they had me, and so my first language was loss."

Deborah Miranda, When Coyote Knocks on the Door (2021)

#quotes#literature#lit#poetry#spilled ink#modern literature#poets of color#native literature#indigenous literature#native authors#native writers#women authors#women writers#queer authors#queer writers#indigenous writers#indigenous authors#indigenous women#native american literature#deborah miranda#american literature

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

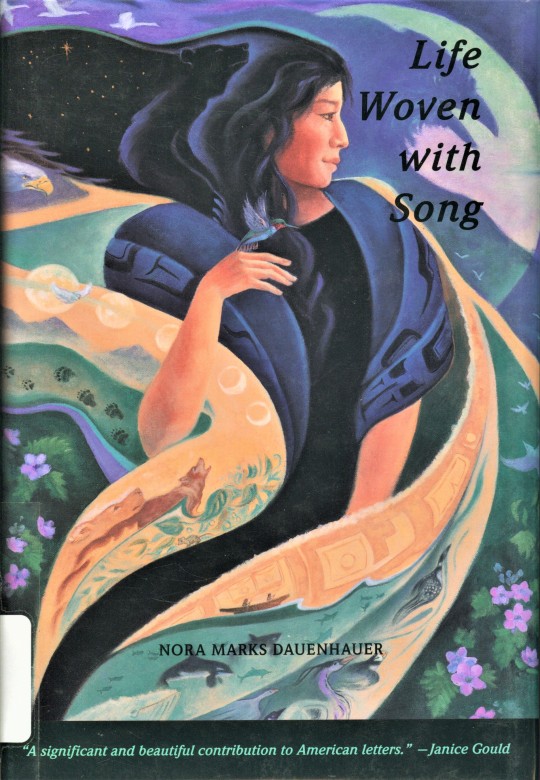

Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week

NORA MARKS DAUENHAUER

Continuing on our trek through what remains of March, I offer you another Indigenous woman writer, Nora Marks Keixwnéi Dauenhauer (1927-2017), a Tlingit writer from Juneau, Alaska. Born in Juneau, Dauenhauer grew up there as well as in Hoonah, Alaska with a father who was a fisherman and carver, and a mother who was a beader. Dauenhauer lived at times with her parents on a fishing boat and in seasonal camps. Being a member of the Tlingit tribe, her first language was Łingít, and she did not learn English until she was eight.

Following her mother in the Tlingit matrilineal system, she was a member of the Raven moiety of the Tlingit nation, of the Yakutat Lukaax̱.ádi (Sockeye Salmon) clan, of the Shaka Hít or Canoe Prow House, from Alsek River. She was chosen as clan co-leader of Lukaax̱.ádi (Sockeye Salmon) in 1986 and as trustee of the Raven House and other clan property. She was then given the title Naa Tláa (Clan Mother) in 2010, becoming the ceremonial leader of the clan.

Dauenhauer earned a BA in anthropology from Alaska Methodist University in Anchorage. In the early 1970s, she married poet and Tlingit scholar Richard Dauenhauer and together they made significant contributions to preserve the Tlingit oral traditions in their Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature book series. Nora Dauenhauer became a Tlingit language researcher for the Native Language Center at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks from 1972-1973, and then became the principal researcher in language and cultural studies at the Sealaska Heritage Foundation in Juneau from 1983-1997.

On the subject of preserving the Tlingit oral tradition and its importance, Dauenhaur said:

People are now beginning to take action for language and cultural survival, and my work is to help provide inspiration and tools for this through my writing.

Dauenhauer had several accomplishments, including being named the 1980 Humanist of the Year by the Alaska Humanities Forum. Together, the Dauenhauers were awarded the Alaska Governor’s Award for the Arts, two American Book Awards, and a Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award. In 2005, Nora Dauenhauer was the recipient of the Community Spirit Award from the First People’s Fund.

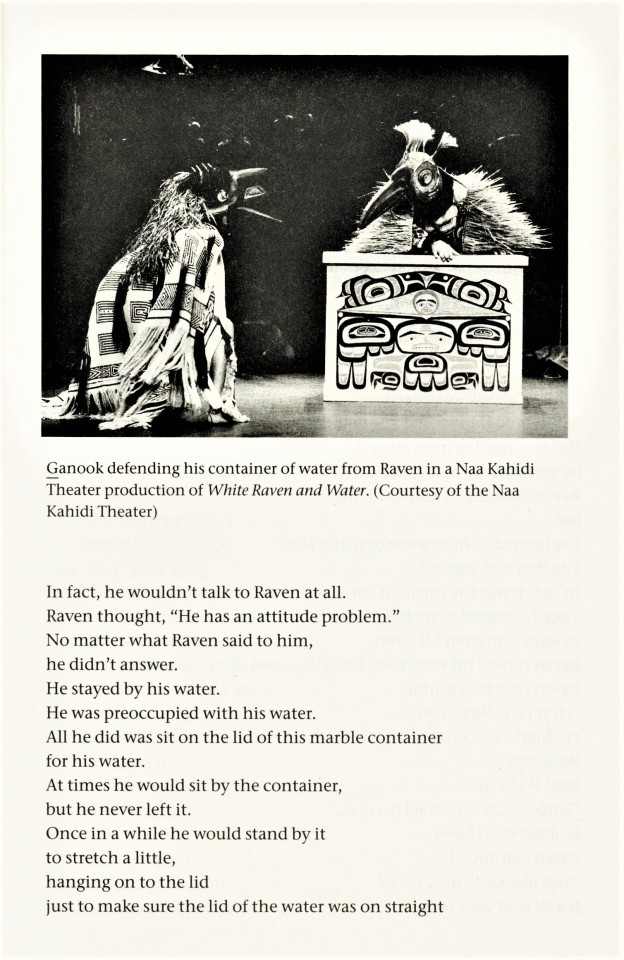

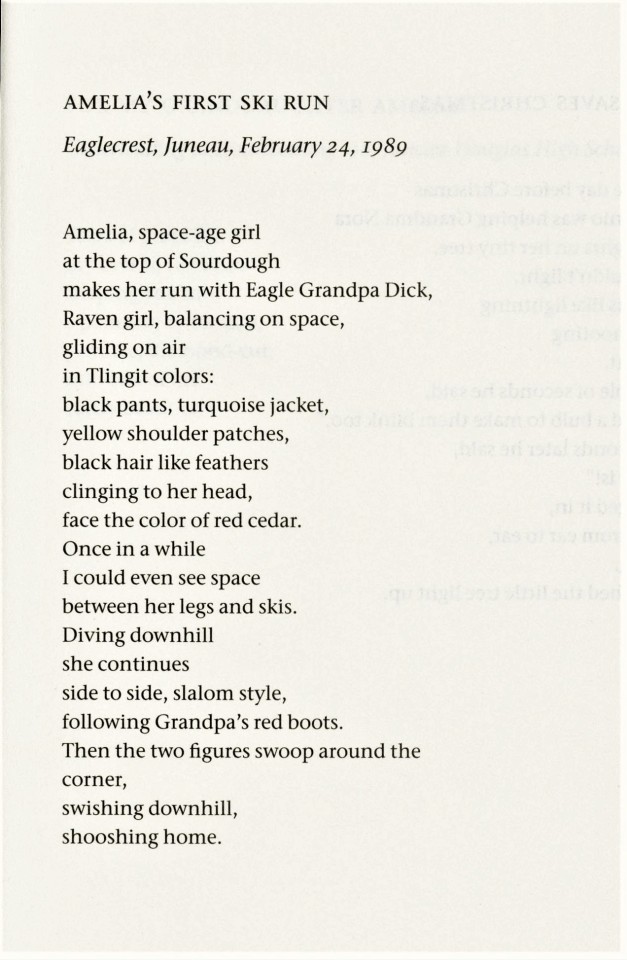

As a poet, Nora Dauenhauer published two collections, one of which we hold in Special Collections, Life Woven With Song, published by the University of Arizona Press in 2000 (the other is The Droning Shaman, Black Current Press, 1989). This book recreates the oral tradition of the Tlingit people through written language in a variety of literary forms, and records memories of Dauenhauer’s heritage from old relatives and Tlingit elders, to trolling for salmon and preparing food in the dryfish camps and making a living by working in canneries.

Author Photo is by Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie

See other writers we have featured in Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week.

View other posts from our Native American Literature Collection.

-- Elizabeth V., Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

#Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week#women's history month#Native Americans#Native American writers#Native American women writers#Nora Marks Dauenhauer#Richard Dauenhauer#Tlingit#Life Woven With Song#University of Arizona Press#Alaskan writers#poets#poetry#Elizabeth V.#Native American Literature Collection

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

timers and curfews.

i find myself,

starting to hate timers.

why?

i'll never know.

well

actually

i

do.

as you wrap your

arms around my waist,

i feel my body shiver;

twitch.

i feel the concept

of

time start to become

the least of my worries...

images of what we could do

while frank ocean plays,

flash in my

perverted mind.

my breathing quickens.

your hands trail further.

my body leans in closer.

i respond with a soft sigh.

and there it is.

that god awful.

timer.

to ruin our moment.

we awkwardly say goodbye.

i roll over as you drive away.

and i lay,

and think,

"maybe another time."

maybe i'm just bad at acting on affection.

the song i listened to today:

#loserpoetrv#creative writing#creative poetry#new writer#new poet#writers and poets#writing#poets of tumblr#you are loved#you are not alone#and you are beautiful#remember this.#poetry#original poetry#original poem#poetscommunity#female poets#poc poet#native poet#native american#shitty poetry#wlw post#wlw yearning#wlw poetry#wlw poem#if you know me irl no you dont#theyre so good at kissing#im so gay#oh my god#help

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I’ve lost my long hair; my eagle plumes too. / From you my own people, I’ve gone astray. / A wanderer now, with no where to stay."

Read it here | Reblog for a larger sample size!

#open polls#polls#poetry#poems#poetry polls#poets and writing#tumblr poetry#have you read this#the indian's awakening#zitkála-šá#gertrude simmons bonnin#native american#sioux#residential schools

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

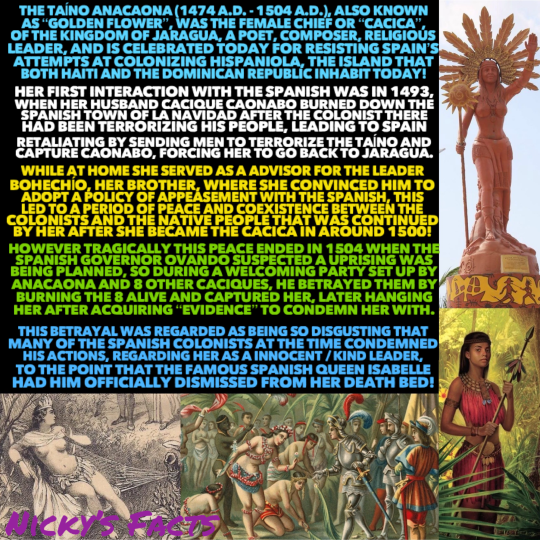

Anaconda remained a advocate for peace to the very bitter end.

🏵️

#history#anacaona#taino#historical figures#hispaniola#native american history#cacica#haiti#dominican republic#womens history#queen#female rulers#royalty#indigenous peoples#jaragua#girl power#caribbean history#female poets#colonization#peacemaker#historical women#royal history#new spain#queencore#1400s#1500s#caribbean sea#nickys facts

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joy Harjo is an internationally renowned performer and writer of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. She served three terms as the 23rd Poet Laureate of the United States from 2019-2022 and is winner of Yale's 2023 Bollingen Prize for American Poetry. Read her full bio. here

Perhaps the World Ends Here by Joy Harjo

The world begins at a kitchen table. No matter what, we must eat to live.

The gifts of earth are brought and prepared, set

on the table. So it has been since creation, and it will go on.

We chase chickens or dogs away from it. Babies teethe at the corners. They scrape their knees under it.

It is here that children are given instructions on what it means to be human. We make men at it, we make women.

At this table we gossip, recall enemies and the ghosts of lovers.

Our dreams drink coffee with us as they put their arms around our children. They laugh with us at our poor falling-down selves and as we put ourselves back together once again at the table.

This table has been a house in the rain, an umbrella in the sun.

Wars have begun and ended at this table. It is a place to hide in the shadow of terror. A place to celebrate the terrible victory.

We have given birth on this table, and have prepared our parents for burial here.

At this table we sing with joy, with sorrow. We pray of suffering and remorse. We give thanks.

Perhaps the world will end at the kitchen table, while we are laughing and crying, eating of the last sweet bite.

"Perhaps the World Ends Here" from The Woman Who Fell From the Sky by Joy Harjo. Copyright © 1994 by Joy Harjo.

#american poetry#joy harjo#native american poet#poet laureate#poetry#native american heritage month#muscogee (creek) nation#academy of american poets

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any native folklore you’ve always wanted to write about? I can say I’m educated enough on the topic to offer ideas, but I do love to hear others passions

I have a lot of ideas. Lol. I’m sure you’ve seen but I always love hearing more ideas too! The only ones that I won’t write about are Sk1nw@lk3rs and W3nd1g0s. Don’t even like spelling them out. Feel free to ask me to write about whatever Indigenous monster/folklore/story you’d like to read

#writers on tumblr#writing#fantasy romance#author#monster lover#monster romance#anon ask#answered asks#writers and poets#asks open#anon asks#ask blog#send asks#send me asks#ask me anything#indigenous mythology#indigenous folklore#indigenous#native american#native folklore#native author#indigenous author#native writer#indigenous writer

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

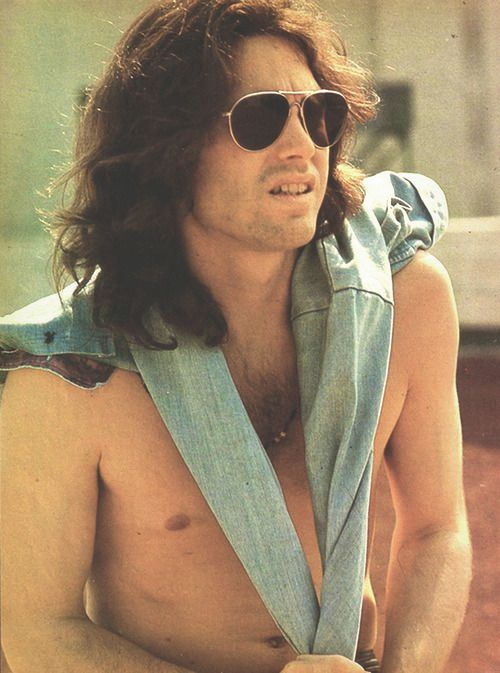

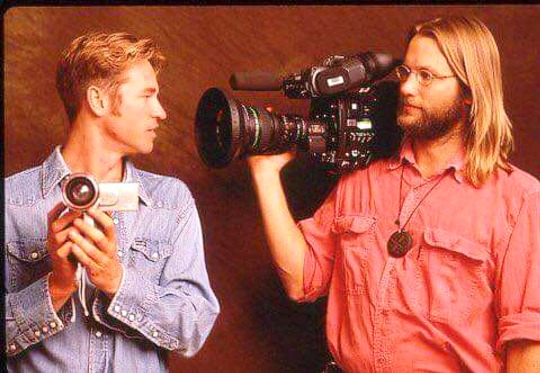

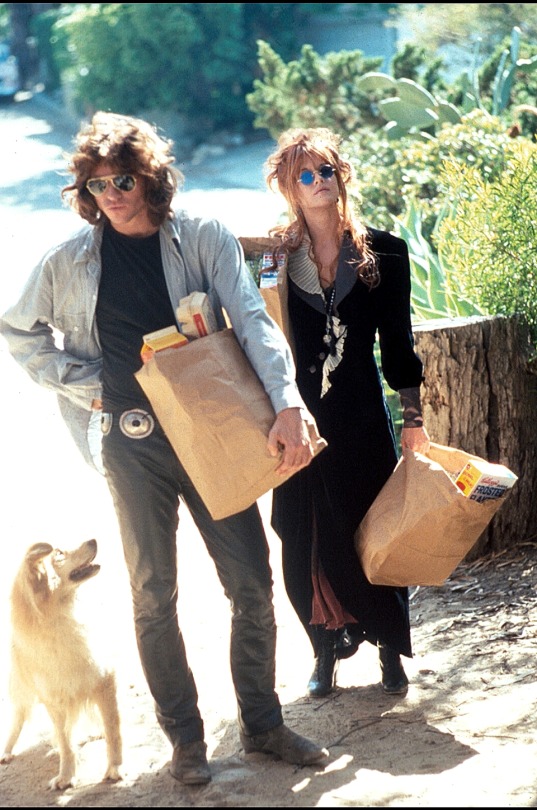

Val and Jim being unofficial twins

part 2

Part 1

#Val Kilmer#The doors#Jim morrison#the lizard king#The doors 1991#Part 2#Twins with 15 year age gap#mr mojo risin#Kindered spirits#Minus the substance abuse#And the alcohol#Poets#Rebels#Icons#Native American#Val is quarter Cherokee

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Something my step-dad would say to me)

“Rain, there are two wolves inside us; a white wolf and a black wolf, and they are constantly fighting. The question isn’t ‘who will win the fight?’, the question is ‘which one will you feed more?’.

#writeblr#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#poetry#writing#artists on tumblr#poem#poets on tumblr#nostalgia#native american#proverb#quotes#inspiring quotes#inspiration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Natalie Diaz

youtube

Natalie Diaz was born in 1978 in Needles, California. Diaz's poetry deals with her own experience growing up on an Indian reservation and the issues facing Native Americans. Her debut poetry collection, When My Brother Was an Azetc, was published in 2012 and won the American Book Award. Her poetry collection Postcolonial Love Poem won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and was a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award. Diaz has received numerous other honors, including a MacArthur Fellowship and the Nimrod/Hardman Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry.

#native american#indigenous#native americans#writers#poets#poetry#native writers#mojave#american indian#Youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iyáaní (Spirit, Breath, Life) | Sara Marie Ortiz

– Acoma Pueblo poet

At Haak’u

Within the community,

on the land, in it, and of it,

there is a way in all things

that Acoma (Haak’u) children are taught.

Shadruukaʾàatuunísṿ

It is a way of saying.

It is a way of saying our life and the way

things grow and grow. It is a way of saying

the children are growing so quickly. It is a way

of saying the plants, which we so lovingly care

for in the…

View On WordPress

#native american heritage month#native american heritage month 2023#native poets#Poem#poet#Poetry#Sara Marie Ortiz

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Sometimes you lose something so big, so immeasurable, that bearing your grief requires an act just as complicated and unfathomable as that loss."

Deborah Miranda, When Coyote Knocks on the Door (2021)

#quotes#literature#lit#poetry#spilled ink#modern literature#poets of color#women authors#indigenous authors#indigenous writers#native writers#native american literature#native women#native authors#queer writers#queer authors#deborah miranda

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

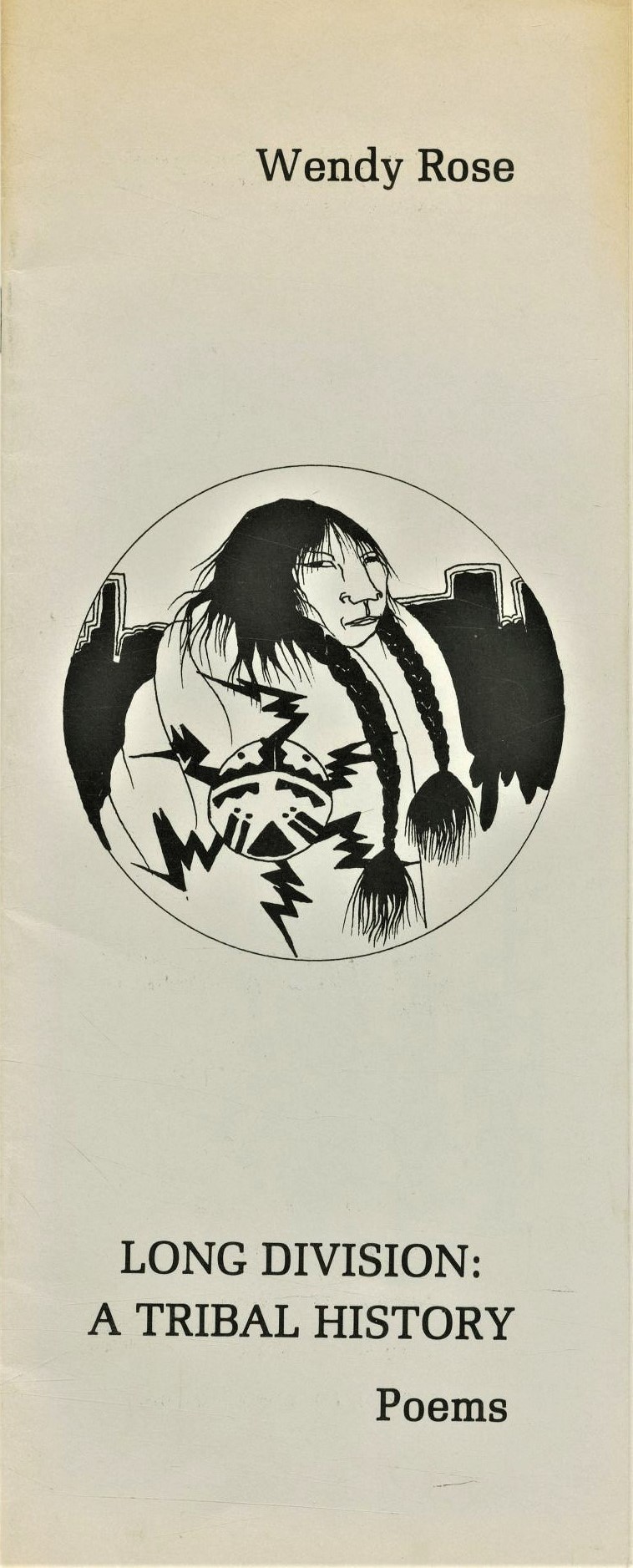

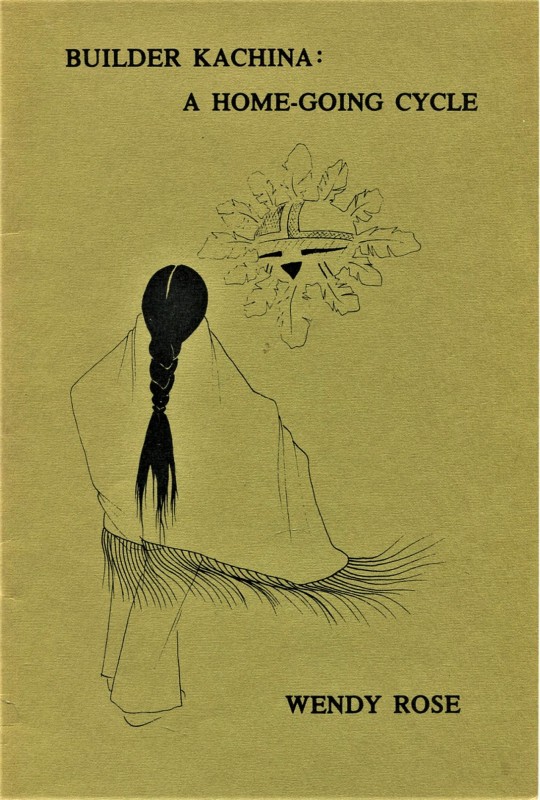

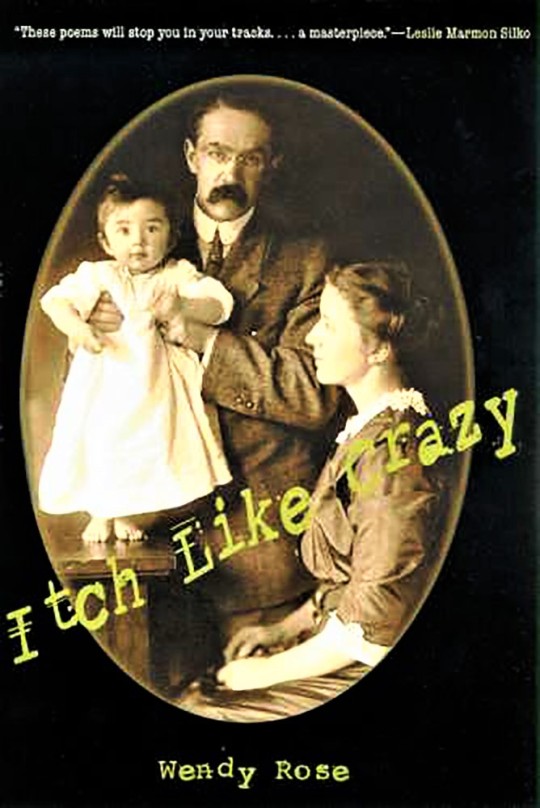

Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week

WENDY ROSE

Hopi/Miwok writer Wendy Rose (1948-) was born in Oakland, California, and did not experience a reservation childhood. She had few connections to her Hopi and Miwok heritage save for stories from her father’s Hopi people. This childhood experience helped shape Rose’s poetry and her focus on reclaiming her cultural identity. Her work is influenced by ethnography, her personal experience of identity, and both her political and feminist stances. Besides poetry, Rose also writes nonfiction that addresses issues of appropriation of Native American culture.

As a young woman, Rose dropped out of high school, joined the American Indian Movement (AIM), and participated in the 1969-71 occupation of Alcatraz. Rose did return to school and earned a BA, MA, and a PhD in anthropology, all from the University of California, Berkeley. Her studies in anthropology helped bridge the gap between her early experiences and her indigenous identity, and she stated that during her time at Berkeley she often “felt like a spy in the field of anthropology.” This experience also led to a decades-long academic career.

UWM Special Collections preserves seven collections of Rose’s poetry: Hopi Roadrunner Dancing (Greenfield Review Press, 1973); Builder Kachina (Blue Cloud Quarterly, 1979); Long Division: A Tribal History (Strawberry Press, 1981); What Happened When the Hopi Hit New York (Contact II Publications, 1982); Going to War With All My Relations ( Northland Publishing, 1993); Bone Dance, (University of Arizona Press, 1994); Itch Like Crazy (University of Arizona Press, 2002).

See other writers we have featured in Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week.

#Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week#women's history month#Native Americans#Native American writers#Native American women writers#women writers#Wendy Rose#Hopi#Miwok#poetry#Native American poetry#women poets#Native American Literature Collection#Elizabeth V.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

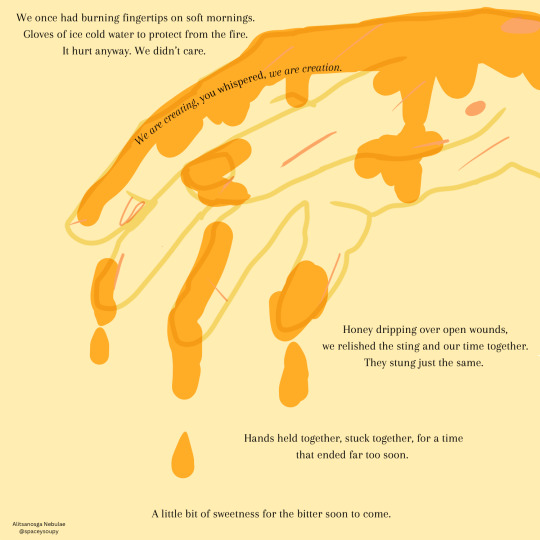

Sweetbitter

“We once had burning fingertips on soft mornings.

Gloves of ice cold water to protect from the fire.

It hurt anyway. We didn’t care.

We are creating, you whispered, we are creation.

Honey dripping over open wounds, we relished the sting and our time together. They stung just the same.

Hands held together, stuck together, for a time that ended far too soon.

A little bit of sweetness for the bitter soon to come.”

Full image description below

[image ID: A square image of a drawing of a hand facing palm side down outlined in golden yellow on a cream yellow background. The hand is covered in a golden orange honey color and has multiple pale pinkish red scratches and sores. Text on the image reads "We once had burning fingertips on soft mornings. Gloves of ice cold water to protect from the fire. It hurt anyway. We didn't care. We are creating, you whispered, we are creation. Honey dripping over open wounds, we relished the sting and our time together. They stung just the same. Hands held together, stuck together, for a time that ended far too soon. A little bit of sweetness for the bitter soon to come." End text. Copyright “Alitsanosga Nebulae @spaceysoupy” pronounced Ah Lee Zah No-Shh Gah end image description]

#alitsanosga poetry#alitsanosga art#indigenovember#poets corner#poets on tumblr#poems on tumblr#my artwork#poetry art#indigeneity#indigenous#indigenous poetry#tsalagi#ᏣᎳᎩ#grief#grief poem#sad poem#native american heritage month#writers on tumblr#queer writers#queer poets on tumblr#writeblr#alitsanosga.txt#this post brought to you by bean bread and generational trauma#poem#poetry

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

38

Here, the sentence will be respected.

I will composed each sentence with care by minding what the rules of writing dictate.

For example, all sentences will begin with capital letters.

Likewise, the history of the sentence will be honored by ending each one with appropriate punctuation such as a period or a question mark, thus bringing the idea to (momentary) completion.

You may like to know, I do not consider this a “creative piece.”

I do not regard this as a poem of great imagination or a work of fiction.

Also, historical events will not be dramatized for an interesting read.

Therefore, I feel most responsible to the orderly sentence; conveyor of thought.

That said, I will begin.

You may or may not have heard about the Dakota 38.

If this is the first time you've heard of it, you might wonder, “What is the Dakota 38?”

“The Dakota 38” refers to the thirty-eight Dakota men who were executed by hanging, under orders from President Abraham Lincoln.

To date, this is the largest “legal” mass execution in U.S. history.

The hanging took place on December 26th, 1862—the day after Christmas.

This was the same week that President Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation.

In the preceding sentence, I italicize “same week” for emphasis.

There was a movie titled Lincoln about the presidency of Abraham Lincoln.

The signing of The Emancipation Proclamation was included in the film Lincoln; the hanging of the Dakota 38 was not.

In any case, you might be asking, “Why were thirty-eight Dakota men hung?”

As a side note, the past tense of hang is hung, but when referring to the capital punishment of hanging, the correct tense is hanged.

So it's possible that you're asking, “Why were thirty-eight Dakota men hanged?”

They were hanged for The Sioux Uprising.

I want to tell you about The Sioux Uprising, but I don't know where to begin.

I may jump around and details will not unfold in chronological order.

Keep in mind, I am not a historian.

So I will recount facts as best I can, given limited resources and understanding.

Before Minnesota was a state, the Minnesota region, generally speaking, was the traditional homeland for Dakota, Anishinaabeg and Ho-Chunk people.

During the 1800s, when the U.S. expanded territory, they “purchased” land from the Dakota people a well as the other tribes.

But another way to understand the sort of “purchase” is: Dakota leaders ceded land to the U.S. Government in exchange for money and goods, but most importantly, the safety of their people.

Some say that Dakota leaders did not understand the terms they were entering, or they never would have agreed.

Even others call the entire negotiation, “trickery.”

But to make whatever-it-was official and binding the U.S. Government drew up an initial treaty.

This treaty was later replaced by another (more convenient) treaty, and then another.

I've had difficulty unraveling the terms of these treaties, given the legal speak and congressional language.

As treaties were abrogated (broken) and new treaties were drafted, one after another, the new treaties often referenced old defunct treaties and it is a muddy, switchback trail to follow.

Although I often feel lost on this trail, I know I am not alone.

However, as best as I can put the facts together, in 1851, Dakota territory was contained to a twelve-mile by one-hundred-fifty-mile-long strip along the Minnesota river.

But just seven years later, in 1858, the northern portion was ceded (taken) and the southern portion was (conveniently) allotted, which reduced Dakota land to a stark ten-mile tract.

These amended and broken treaties are often referred to as The Minnesota Treaties.

The word Minnesota comes from mni which means water; sota which means turbid.

Synonyms for turbid include muddy, unclear, cloudy, confused and smoky.

Everything is in the language we use.

For example, a treaty is, essentially, a contract between two sovereign nations.

The U.S. treaties with the Dakota Nation were legal contracts that promised money.

It could be said, this money was payment for the land the Dakota ceded; for living within assigned boundaries (a reservation); and for relinquishing rights to their vast hunting territory which, in turn, made Dakota people dependent on other means to survive; money.

The previous sentence is circular, which is akin to so many aspects of history.

As you may have guessed by now, the money promised in the turbid treaties did not make it into the hands of the Dakota people.

In addition, local government traders would not offer credit to “Indians” to purchase food or goods.

Without money, store credit or rights to hunt beyond their ten-mile tract of land, Dakota people began to starve.

The Dakota people were starving.

The Dakota people starved.

In the preceding sentence, the word “starved” does not need italics for emphasis.

One should read, “The Dakota people starved,” as a straightforward and plainly stated fact.

As a result—and without other options but to continue to starve—Dakota people retaliated.

Dakota warriors organized, struck out and killed settlers and traders.

This revolt is called The Sioux Uprising.

Eventually, the U.S. Cavalry came to Mnisota to confront the Uprising.

More than one thousand Dakota people were sent to prison.

As already mentioned, thirty-eight Dakota men were subsequently hanged.

After the hanging, those one thousand Dakota prisoners were released.

However, as further consequence, what remained fo Dakota territory in Mnisota was dissolved (stolen).

The Dakota people had no land to return to.

This means they were exiled.

Homeless, the Dakota people of Mnisota were relocated (forced) onto reservations in South Dakota and Nebraska.

Now, every year, a group called The Dakota 38 + 2 Riders conduct a memorial horse rider from Lower Brule, South Dakota to Mankato, Mnisota.

The Memorial Riders travel 325 miles on horseback for eighteen days, sometimes through sub-zero blizzards.

They conclude their journey on December 26, the day of the hanging.

Memorials help focus our memory on particular people or events.

Often, memorials come in the forms of plaques, statues or gravestones.

The memorial for the Dakota 38 is not an object inscribed with words, but an act.

Yet, I started this piece because I was interested in writing about grasses.

So, there is one other event to include, although it's not in chronological order and we must backtrack a little.

When the Dakota people were starving, as you may remember, government traders would not extend store credit to “Indians.”

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakotas by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations on Myrick's words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick's body was found, his mouth was stuffed with grass.

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There's irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

I have italicized the previous sentence to indicate inner dialogue, a revealing moment.

But, on second thought, the particular words "Let them eat grass" click the gears of the poem into place.

So, we could also say, language and word choice are crucial to the poem's work.

Things are circling back again.

Sometimes, when in a circle, if I wish to exit, I must leap.

And let the body swing.

From the platform.

Out

to the grasses.

— Layli Long Soldier (1973–)

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry (2020)

#Layli Long Soldier#38#Dakota 38#Native American#poem#poet#poetry#history#American history#When the Light of the World Was Subdued Our Songs Came Through

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

These type of nights hurt the most, when you realise somebody out there is hurting because of you.

How do I move on from tasting something so sweet, loving you was like a dream. from kisses to bruises. It's was nightmarish and foolish but everytime we inhaled eachothers existence I couldn't help but melt away with you.

Everything baby blue boy my melody was for you. you were mine and that right there is the truth. Oh These type of nights hurt the most I wish I was holding you close but it's time I open my eyes .... and realise everything was just a dream and nothing about us meant a thing to you, now I'm hurting out here because of you.

#another breakup poem#breakups suck#breakups#breakup#deep depression#depression sucks#depression#depressing shit#recovering alcoholic#recovery#i miss the old days#i miss the old you#i miss the old us#i miss you#dont look back#native american#sad girl club#back at it again#kinda poetry#poet#sad notes#original poem#original art#original#feel my heart#the real me#anxiety#anxiety sucks#high and low#420stoner

3 notes

·

View notes