#new spain

Photo

The maximum extension of New Spain.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cristóbal de Villalpando (Spanish/New Spain, 1649-1714)

The deluge, 1689

Catedral de Puebla, Zaragoza

#Cristóbal de Villalpando#the deluge#el diluvio#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#oil painting#fine arts#europa#mediterranean#spanish art#spanish#new spain#hispanic#latin#1600s#artwork#flemish#flemish art#classic art#painting#christian art#christian#genesis#bible#catholic#christentum

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earliest European depiction of the city of Tenochtitlan, Mexico, 1524 (3 years after it was destroyed by Cortés). Note the Habsburg flag indicating the city as a domain of Charles V. Even so, it is believed to be generally accurate in proportion and overall features of the city pre-Conquest.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emiliano Zurita and Miguel Bernardeau in Zorro (2024)

#zorro#new zorro#new zorro series#emiliano zurita#miguel bernardeau#diego de la vega#monasterio#amazon prime#hot soldier#1800s#mexico#new spain#california#sexy actor

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

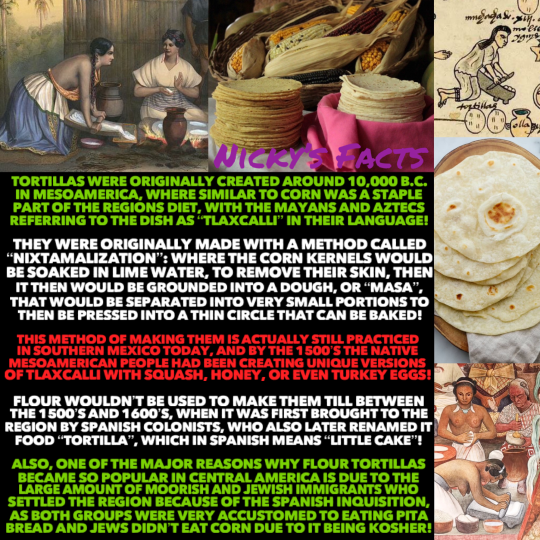

After around 12000’s years, tortillas still remains a delicious stable of Central American cuisine!🫓

🌮🇲🇽🌯

#history#tortillas#tlaxcalli#mesoamerica#corn tortillas#mexican history#aztec#corn#flour#mayan#food history#immigration#new spain#flour tortillas#indigenous peoples#latin america#spanish inquisition#latina#aztec history#nixtamalization#mexican food#ancient#1500s#mayan history#tex mex#indigenous americans#central america#nickys facts

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Img: Spain showing off the jewels of the Spanish Empire ft my Mexico design who is judging the hell out of Spain

So it’s canon that Spain was so busy looking after Romano, he didn’t pay attention to his other colonies. So who was looking after the colonies of New Spain? Mexico, obviously

I tried my hand on what I think Mexico would look like and here she is being shown off like a trophy along with little Philippines and young Cuba cause these three made the empire the most money. And yeah, she pretty salty about not only that but also having to be in charge of the other kids while not being that much older herself

Spain: I have made a formidable empire

America: You fucked up a country, is what you did. Look at her, she’s got older sister syndrome

#hetalia#historical hetalia#did my best to draw the clothes of the time period#hetalia headcanons#hetalia spain#aph spain#hws spain#hetalia mexico#aph mexico#hws mexico#hetalia philippines#aph philippines#hws philippines#hetalia cuba#aph cuba#hws cuba#new spain#my art#hetalia fanart

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

from An Account of a Voyage Up the River de la Plata and Thence Over Land to Peru by Acarete du Biscay, published in English in 1698.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spain’s occupation of Mesoamerica violently disrupted the latter’s evolution, destroying Mesoamerican social institutions, religion, and infrastructure. Within 80 years, 1519–1600, the native population fell from at least 25 million to about a million. What followed was 300 years of colonial rule, accompanied by political and economic exploitation, the categorization of people by color, and the projection of the dominant class’s worldview. It pulled Spain and, ultimately, all of Europe out of the dark ages.

The Spanish Conquest

In 1492, Columbus landed in what are now the islands of the Caribbean. When he could not find sufficient gold and wealth, he turned to trading in slaves.

By the early 1500s, sugar-growing plantations emerged on the islands.

On his second voyage of 1493, he introduced sugar cane plants to the Caribbean. Columbus knew that sugar and slavery were inseparable and that tremendous profits could be gotten from sugar.

Columbus himself justified the enslavement of the indigenous people, claiming they were cannibals. The Spaniards repeated this pretext throughout the colonial period.

Faith versus Rationality

The Laws of Burgos were almost never enforced.

Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda based his arguments on Aristotle’s doctrine of natural slavery: “that one part of mankind is set aside by nature to be slaves in the service of masters born for a life of virtue free of manual labor.” Sepúlveda wrote a treatise justifying war against the natives. According to him, the Spaniards had the right to rule the “barbarians” because of their superiority. He compared the natives to wild beasts.

The Spanish Invasion of the Mexica

The Spaniards slowly explored the Caribbean coastline of Middle America, gathering information. In the late 1510s, Hernán Cortés landed on the mainland that was to become Mexico. On the island of Cozumel, Cortés encountered the Maya. In 1519, Cortés sailed to what today is Veracruz, and within two years Cortés’s forces conquered the great Azteca Empire and began the colonization of what they later called New Spain.

Throughout the advance to the Azteca capital of Tenochtitlán, the Azteca would stop fighting periodically to remove their dead and wounded from the battlefield. At close range, the Native Americans used wooden clubs ridged with razor sharp obsidian.

The Azteca were not immune to smallpox and other European diseases, so outbreaks of these diseases had the effect of germ warfare. At a critical moment, when it seemed as if the Azteca might drive out Cortés’s men, a smallpox epidemic ravaged the native population.

The Colonization of Native Mesoamerica

After the conquest of the Azteca, the Spaniards—through looting and torturing conquered the Tarasco; they executed the Cazonci, the Tarascan ruler, by dragging him through town behind a horse and burning him at the stake. Cortés’s men also subdued the natives of Oaxaca, but the conquest of the Maya proved more arduous. Many Maya fled to the dense forests and remained out of the control of the Spaniards for 200 years.

Smallpox and Other Plagues

The distinguishing characteristic of the subjugation of the Mesoamerican native populations was its genocidal proportion. The term genocide is used here because when people lose 90 plus percent of their population, millions of lives, an explanation must be forthcoming. As with a nuclear disaster, saying it was accidental is no excuse. After the conquest of Tenochtitlán, smallpox and other epidemics spread throughout the countryside, subsiding and recurring, until eventually as many as 24 million died in what is Mexico. Certainly, the smallpox, measles, and influenza outbreaks hit urban areas hardest because of the population concentration. (These three diseases are highly communicable, being transmitted mainly by air.)

There were four major epidemics in the first 60 years of Spanish occupation. Smallpox caused the first epidemic of 1520–1521, the second year after Spanish contact and untold thousands died. The second epidemic of smallpox (possibly combined with measles) broke out in 1531. The Azteca called it tepiton zahuatl, or “little leprosy.” The third epidemic began in 1545 and lasted three years. The Azteca called this cocoliztli, or “pest,” thought today to have been hemorrhagic fever. A fourth epidemic, again named cocoliztli, lasted from 1576 to 1581, and an estimated 300,000–400,000 Native Americans died of it in New Spain.

Apologists argue that it was the indigenous’ predisposition to diseases that made them vulnerable to European diseases. A plausible explanation is that the lack of larger-sized domesticated animals shielded the natives from diseases carried by animals. The introduction of domestic animals, accordingly, contributed to the spread of diseases to the natives.

The Columbian Exchange refers to widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations that included slavery, communicable disease, and ideas between Spain and the New World. This exchange cost lives and the destruction of cultures. It brought the Atlantic slave trade, the enslavement of indigenous populations, and the diseases that killed millions of Native Americans. The Americas as part of the exchange sent corn, the potato, the tomato, peppers, pumpkins, squash, pineapples, cacao beans (for chocolate), and the sweet potato and animals such as turkeys. The Europeans brought smallpox, influenza, malaria, measles, typhus, and syphilis. The exchange wiped out the indigenous peoples’ religions, submerged their languages, and tried to blank out their history. It introduced a European construct of race that lasts to this day.

The Conquest of Race and Labor in Mesoamerica

The invaders practiced a “scorched-earth” strategy, causing widespread environmental destruction and social disorganization. Large numbers of displaced, disoriented, and depressed refugees roamed the countryside, suffering severe nutritional deficiency and often starving to death. Illness often prevented many natives from caring for their crops or from processing corn into tortillas. The acute food shortage resulted in starvation, and contaminated food and water spread other diseases. Meanwhile, the Spaniards forcefully herded natives into new farming schemes. Alcoholism took an additional toll with the distilling of native drinks. Before the invasion, pique, which was low in alcoholic content and rich in vitamins, was used for religious purposes. When the Spaniards introduced distilled alcohol, addiction became common. Urban resettlement plans only reinforced substantial crowding and lack of hygiene, and native centers became breeding grounds for epidemics.

Indigenous Labor

The crown gave former conquistadores (meaning “leaders of the crusades”) encomiendas, large tracts of land with native subjects which was also used in the Caribbean islands. The encomendero received tribute from a village along with indigenous labor. The invaders often maltreated and abused the natives, keeping them in a state of serfdom.

Indigenous slavery and the encomienda flourished on the peripheries and frontiers of New Spain well into the nineteenth century. Employers often ignored giving indigenous populations wages for their labor. The repartimiento included the requirement that natives purchase goods from Spanish authorities.

Structural Controls

In order to control them, colonial authorities grouped native communities into municipios, townships. The largest town of the municipios was the cabecera, or head community. It strengthened colonial control of the native village. The purpose was to isolate natives in order for them to identify with the local village rather than forming class or ethnic identities. This division made it difficult for the different communities to unite against Spanish rule, destroying intercommunity regional networks and the pre-invasion world system.

Spanish was the official language. All official government business was conducted in Spanish. If the native or the casta, of mixed race, spoke Spanish, he or she was considered superior to those who did not. The Catholic Church was the state religion, and the Christian God supplanted the indigenous gods. The paternalism of the Spanish friars was racist, and they saw the natives as being childlike.

Influenced by the Spanish Reconquista, they were intolerant and hostile toward any person who was non-Catholic. To hold office or be a noble, the nominee was required to prove a limpieza de sangre (purity of blood), that is, that they were not of Jewish or Moorish blood. The intolerance extended to Spain’s colonies. To further consolidate its power, Spain imposed a caste system based on race that designated an individual’s rank according to color. There were four main categories of race: the “peninsular,” or Spaniard born in Spain; the “criollo/a,” a person of Spanish descent born in Mesoamerica; the “indio/a,” or native; and the “negro/a,” of African slave descent. Innumerable subcategories of hybrids developed over time. This system, used for social control, lasted in various forms throughout the colonial period, although it became more difficult to keep track of one’s class position as the castas (those of mixed race) moved north. The advantage of moving up in race is obvious: The more Spanish one looked and claimed to be, the more privileges the person enjoyed.

Women in Colonial Mesoamerica

From riches extracted from the labor of the indigenous, colonial society could afford to produce literature and the arts.

The social and economic roles of women varied between pre-colonial and colonial societies. Women were the victims of rape, the ultimate symbol of subordination, and the economy opened only limited opportunities for them. In Yucatán the introduction of sheep led to the commercial production of wool. Women were generally responsible for making woolen goods. The repetitive motions in textile work resulted in physical ailments.

Azteca women were recognized as adults. They had rights before the law and society. Under Spanish rule, their standing was weakened. Native women were not always recognized as hijas del pueblo, daughters or citizens of the town, with communal land rights. Women’s rights to property narrowed under colonialism, and their participation changed as commercial agriculture put pressure on los de abajo (the poor and powerless) to abandon or sell their land.

Institutionalizing Inequality

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, women generally married when they were about 20 years of age. After the arrival of the Spaniards, however, Church friars encouraged females to marry at 12 or 14. Early reproduction often resulted in health disorders, including anemia. Society was patriarchal, and men received preferential treatment in nutrition. Even in death, men received favored treatment. In sum, the colonization worsened the status of women and increased violence toward them.

The family structure also changed during the colonial period. For a time, the native nobility kept much of their prestige. But the colonization led to the breakdown of the traditional indigenous family framework, which was based on an extended family rather than the highly patriarchal nuclear family that the Spaniards favored. This not only reduced the authority of the elders but also removed the support network for women within the clan.

Early marriage also influenced gender relations and increased the power of the male within the nuclear family, reducing the authority of native women within the clan. The age difference between male and female spouses favored the male.

The Assimilation of Native Women

The Catholic Church promoted rigid attitudes toward women, making women the scapegoats for its failures in converting the natives. Priests blamed indigenous mothers for not assimilating their children, although little attention was paid to educating indigenous women and children. By contrast, during the pre-conquest period, women worked as marketers, doctors, artisans, and priests, and perhaps occasionally as rulers.

The Virgen de Guadalupe is the symbol of Spanish social control, representing a passive female role model, subservient to male authority. The supposed appearance of the Virgin Mother to Juan Diego at Tepeyac in 1531 is an example of a substitution by church authorities of the Virgin of Guadalupe for the indigenous goddess Tonantzin, mother of gods.

Al Norte

The Spaniards sent expeditions from Colonial Mexico in every direction searching for riches. Meanwhile, a viceroy sent scouting expeditions from central Mexico to investigate rumors of another Tenochtitlán to the north. In 1533 Diego de Guzmán, a slave trader, penetrated as far as Yaqui Valley, in what today is Sonora, Mexico.

The northern tribes resisted the Spanish encroachments, and the Spaniards called them indios bárbaros, or barbaric Indians. In short, the invaders felt entitled and were offended that the indigenous people did not meet them with open arms.

Meanwhile, the Spanish named the colonial administrative region in western Colonial Mexico “Nueva Galicia”; it made up roughly the present states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and south Sinaloa. Guadalajara was its administrative capital and base of operations for expeditions into the northwestern frontier. An expedition led by Nuño de Guzmán left a trail of depredations, enslavement, and mistreatment of natives as the Spaniards moved through the area as far north as Sinaloa. The most notable of the native rebellions were those of the Tepeque and Zacatecos indigenous at Tepechitlán.

The move to the north was not easy, as the northern tribes resisted the encroachment.

The Chichimeca, sometimes called Otomí or Zacatecos, and their allies fought the advance of the Spaniards throughout the 1560s and 1570s, with Spanish settlements forming a large triangle between Guadalajara, Saltillo, and Querétero.

The Decimation of the Indigenous Population

The Spaniards’ arrival on the northern frontier and domesticated animals, devastated the native ecology and intensified competition for rivers and valleys. They pushed the native peoples off their lands. The Spanish authorities responded to native resistance by organizing presidios, forts. As with the Mesoamerican civilizations, the numbers of natives fell drastically during the Spanish occupation.

The Living Patterns of the Northern Corn People

Most natives lived in rancherías, semi-fixed farming settlements. Three-quarters of all indigenous ranchería natives were Uto-Aztecan. But they varied greatly as to their population density, mode of living, and organization, depending on rainfall and the flow of rivers. For example, at the time of the arrival of the Spaniards, fixed villages did not exist in Chihuahua; instead, natives moved in search of water. In the spring they would travel to the headwaters in the sierras, farm, and live there for the summer, and then migrate east to the deserts during the winter where they would subsist on desert vegetation. This pattern of migration meant that the size of the ranchería was smaller than a traditional native village, numbering between 30 and 50.

The Tarahumara people of modern Chihuahua/Durango lived over a large area; they would come together at tesgüinadas, festivals. In Sonora, the Pima and the Yaqui lived in areas that were more compact. Their rivers, such as the Great Rio Bravo or Grande, gave life to villages of thousands and complex social and political systems.

The Changing Order

With the arrival of European invaders in Zacatecas, near the mines, haciendas for cattle raising sprang up, which caused tensions with the native populations in these valleys as the invaders usurped the best land and believed themselves entitled to native labor. As in the south, the Spanish elites considered themselves entitled to encomiendas of natives.

Slowly, the Spanish imperial system moved up the Pacific coast to Culiacán, and, simultaneously, up the Zacatecas trail to Durango and Chihuahua. Because of the lack of population and capital, Catholic missions played an essential role in extending the empire’s borders and congregating a religious presence on the frontier. The growth of the mining industry increased the need for food production, forcing the natives to work longer hours, while the mines and the haciendas pressured the missionaries to provide more native workers. These demands, along with the frequent droughts and epidemics that depopulated the region, made the natives restless. Their frequent uprisings made the Franciscan and Jesuit missionaries, as well as the outside invaders, increasingly dependent on the presidios to maintain order by force.

Meanwhile, the missions profoundly changed the lives of indigenous people. For example, women always held strong roles in their communities. Females and males seem to have inherited wealth equally, and women were involved in the trades of weaving and pottery. Both men and women could marry multiple times before they found the ideal mate. A native woman had the choice of abortion, and women participated in ceremonies. Pre-conquest women shared these cultural memories and religious values; however, the missions ended these choices, as they imposed the attitudes and values of Spanish society on the natives. A hierarchical structure made clear distinctions between the male and female spheres. Finally, Spanish institutions such as the repartimiento shifted women to work that men had previously done.

The invaders uprooted Native Americans from their villages and destroyed their institutions. Consequently, natives caught in a work-or-starve situation formed a large sector of the wage earners.

The northern expansion did not come without cost as the indigenous resisted the encroachment as well as enslavement and other forms of forced labor. Due to war and epidemics, the indigenous populations of Chihuahua dwindled radically. Throughout the frontier, from 1560 to 1650 the population declined by 50 percent. The population fell 90–95 percent by 1678. In the 1690s, yet another epidemic of measles broke out. Droughts and labor shortages affected the supply of food.

Forced Labor

Coercion was part of the colonial process. Government officials in collusion with the agricultural establishment perceived the indigenous populations as key to production. Landowners and miners sought arrangements that bound natives without being required to pay wages or credit advances. In the mines and haciendas indigenous slaves were used.

Periodic bonanzas increased demand for labor. Mine owners and hacendados pressured the missions for workers. The encomenderos were in full control of the native population under their charge, often abusing the natives by renting “their” natives to mine owners and other hacendados.

The repartimiento, although primarily used for agricultural labor, was sometimes used for the mines.

The Northern Corridor

Nueva Vizcaya was the “heartland” of the northern frontier for some 250 years. It encompassed the area north of Zacatecas and included most of the modern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Durango, and, at different times, parts of Sinaloa, Sonora, and Coahuila.

The 1680 Revolt of indigenous people spread and affected the whole of Nueva Vizcaya and Sonora; it became known as the “Great Northern Revolt.”

When the Spanish army put down the rebellion, military authorities tried the rebels in Spanish courts and sentenced them to hanging, whipping, dismemberment of hands or feet, or slavery.

Most of the mestizo colonists were of humble birth, although they fashioned themselves Spaniards to distance themselves from the indigenous and other lower castas.

In 1688, the Tlaxcalán participated in the building of the presidio of San Juan Bautista near today’s Eagle Pass in Texas.

In the 1700′s Spain chose to invade the rich valleys of the upper Rio Grande and districts of Nuevo León and Coahuila to prevent French encroachment into this area. The incentive for this expansion was the need for more pasturage for their herds and cattle. The colony of Nuevo Santander included the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. As in other areas, the natives resisted Spanish invasion.

The Native American population in Nuevo Santander was estimated at 190,000 in 1519; by 1800 it fell to 3,000. The administrative structure of the colony was stratified into large landholders, high government officials, and merchants. The rancheros made up a middle group along with artisans, while the natives and servants lingered at the bottom of the social ladder.

The Occupation of Alta California

The colonization of Alta, or Upper, California began in 1769. Upper California had been one of the most densely populated regions in what is now the United States, with a native population of nearly half a million. The population fell to half that number during the Spanish colonial period. The Franciscans led the colonization of Alta California where they established 21 missions. At the height of their influence, the missions had 20,000 natives living under their control.

From south to north the missions housed tribes such as the Diegueño. Inhabiting the coastland, they were skilled artisans who fashioned sea vessels out of soapstone and used clamshell-bead currency. These tribes bore the brunt of missionary activity.

The Missions

Because of the friars’ puritanism and harsh treatment, they drove the indigenous populations to rebellion. Birthrates fell among the indigenous people during the mission period. Furthermore, work was associated with a complex system of punishments. The indigenous people in California were not used to the type of confined physical labor found in the missions.

Alongside the missions, presidios and pueblos were built to consolidate Spanish rule. Spanish officials granted many former presidio soldiers land, known as ranchos. Some received larger grants for haciendas. The California natives did most of the labor.

Father Junípero Serra told of how the indigenous people resisted missionization and sometimes became warlike and hostile “because of the soldiers’ repeated outrages against the women. Even the children who came to the mission were not safe from their baseness.” Evidence suggests that offenses against women were not remedied; rape and even murder went unpunished. Military officials assumed a “boys-will-be-boys” attitude.

On the Eve of the Mexican War of Independence

By the eve of the Mexican War of Independence, a new society had evolved on the northern frontier of New Spain. We should not romanticize this society as egalitarian. Though most of the inhabitants were non-European, the elites in these societies were recently immigrated and invading Spaniards and/or their criollo children. The vast numbers of subjects were castas, those of mixed race, which had limited access to land. Race established privilege, and the more Spanish the subject appeared the more privileges that person had.

Race by the nineteenth century was based more on sight. What would become the Mexican (and Central American) was a conglomerate of people whose racial identity could change from generation to generation—it went beyond the mestizo paradigm popularly portrayed. For instance, the 1810 census suggests that more than 10 percent of the population were Afromestizos, a classification that generally meant they looked mulato or more African than Spanish. Over generations, those who were originally native, and because of the hierarchy of race, wanted to look more like Spaniards.

As has been mentioned, forced labor, the wars, the enslavement of the natives, and droughts and plagues had taken their toll on the native population. Either they had become hispanicized, or they perished or were forced into exile. In some cases, like that of the Tarahumara, a large portion of them retreated further into the Sierra Madres.

On the eve of the Mexican Revolution, Mexico did not yet have a set national identity. The new nation was predominantly indigenous, and Africans were at least 10 percent of the population. Given the 300-year tradition of lying about race in order to gain category, it can be speculated that as many as 20 percent of the population had some African blood and less than stated were full-blooded Spaniards. The colonial mentality and racial ambivalence are a factor even today among the Mexican people. In 1810 the indigenous population fell from 60 percent to 30 percent.

The population of Mexico in 1810 consisted of 3,676,281 indigenous, which were 60 percent of the nation. In contrast, there were only 15,000 (0.3 percent) Europeans or peninsulares. According to estimates, criollos (Euromestizos) numbered 1,092,397 (18 percent). Mestizos (Indiomestizos) a mixture of Spanish and indigenous numbered 704,245 (11 percent), mulatos and zambos (Afromestizos) comprised 624,461 (10 percent); and pure-blooded blacks, 10,000 (0.2 percent). The problem with the data is that race was largely self reporting, and therefore the indigenous and black populations would be under reported because of the social stigma.

Three hundred years of mercantilism had left New Spain without its own commercial or manufacturing infrastructure. Spanish capital fled the country and the mainstays of its economy—agriculture, ranching, and mining—went bankrupt. The Spanish tightly ruled New Spain because it was Spain’s most valuable commodity.

Many of Mexico’s new leaders wanted a modern society based on reason rather than theology. However, Mexicans had to overcome 300 years of Spanish colonialism, which was no small order. The secularization and modernization meant not only the privatization of property belonging to the Catholic Church, but it also meant the privatization of indigenous land. The acceptance of the indigenous heritage, is a process that really did not begin until a hundred years later with the Second Mexican Revolution.

Sources:

#🇲🇽#mexico#indigenous#native#history#colonization#europe#spain#racism#slavery#cannibalism#white supremacy#colorism#serfdom#new spain#🧿#religion#christianity#catholocism#genocide#jewish#antisemitism#muslims#sexism#forced labor#capitalism#torture#military#soldier#mexican war of independence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#yemen#jerusalem#tel aviv#current events#palestine#free palestine#gaza#free gaza#news on gaza#palestine news#news update#war news#war on gaza#spain#unrwa

10K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aztec Empire. Viceroyalty of New Spain. Mexico

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

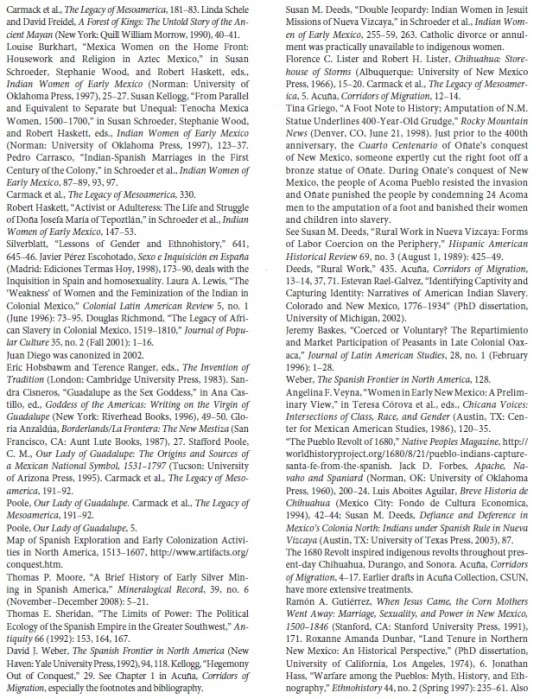

Antonio Rodríguez Beltrán, attributed (Spanish, 1636-1691)

María Luisa de Toledo e indígena, 1670

Museo Nacional del Prado

Doña María Luisa de Toledo y Carreto, Marquesa de Melgar de Fernamental, was the only daughter of Don Antonio Sebastián de Toledo Molina y Salazar, II Marquis de la Mancera and Viceroy of New Spain -between 1664 and 1673-, and of his first woman, D. Leonor de Carreto. And, therefore, she was also the granddaughter of another viceroy, in this case of Peru, D. Pedro de Toledo y Leiva, who held that position between 1639 and 1648. And also, she was the sister-in-law of a third viceroy, D. Gaspar de la Cerda y Sandoval, Count of Galve, her husband's brother, who held office in New Spain between 1688 and 1696. She was a great-great-granddaughter of the first Duke of Alba de Tormes, one of the leading noble houses in Spain, and her husband was the son of the Dukes of Pastrana and the Infantado, another of the main noble families. So, in her person, María Luisa combined an entire noble inheritance linked to some of the great Spanish aristocratic families and to the main positions in the American viceroyalties. She lived part of her childhood and adolescence in the city of Mexico, where, around 1670, she must have made this portrait of her. She returned to Spain, together with her father, in 1674.

She married Joseph de Silva, linking in this way with one of the most powerful houses in the Peninsula, which held the dukedoms of Pastrana, Infantado and Lerma among many other titles, although all of them were part of the inheritance of the eldest son, for which reason None of the consorts had, at the time of the marriage, a noble title. The title enjoyed by María Luisa and her husband, Marquises of Melgar de Fernamental, was granted as a marriage dowry by the Queen herself, Mariana of Austria, in the name of King Carlos II.

The dwarf woman who accompanies her would come from the Chichimeca area, due to the tattoos that adorn her. She has been represented wearing a long and straight huipil, which is superimposed over a green skirt or dress whose lower part protrudes from the previous one. The huipil has been arranged "a la española", that is to say, it seems to be cinched at the waist and has wide added sleeves and a bottom edge with an ova-shaped lace band. The presence of this small indigenous woman was highlighting the uniqueness and exoticism, and therefore the power and prestige of her family. The color of the complexion, the tattoo and even the type of clothing that the little woman wears reveal her connection with American places and the access that the protagonist of the canvas exhibited in relation to some networks of circulation of transoceanic goods and products.

New Spain (modern day Mexico) came to be called Mexico in 1821, after the Mexican War of Independence. The viceroyalty was dissolved and the Mexican Empire was established.

#european history#european art#spanish art#spanish history#new spain#spain#spanish#female portrait#world history#the americas#america#americas#indigenous#art#historical art#mexico#west indies#history of mexico#oil painting#1600s#royal#royaly#noble#nobility#María Luisa de Toledo e indígena#María Luisa de Toledo#indigena#indigenos#north america

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

some good news!! the spanish state's ministry of equality has finally passed one of the most progressive trans laws on the planet, shielded free and universal access to abortion and banned conversion therapy and genital surgery for intersex babies, among a lot of other feminist policies. the minister of equality irene montero gave a speech thanking spain's lgtb and trans associations for helping her draft these legislations. couldn't be more proud!!

#spain#trans#ill always prioritize queer&trans revolution over reformism but man. man these are good news#these are gonna make people's life so much more comfortable#i was lucky enough to live in andalucia where we have THEE most advanced regional legislation on trans rights#so i didnt have to fight too many people to access hrt and to change my name on legal docs#but other ppl on the spanish state have been suffering so fucking much#and yeah this law doesnt cover non binary people or migrants but the door is fucking open. its a step forward#and after this terrible terrible week#after the antitrans antisemite game & brianna's murder and so many rampant transphobia#it feels nice to get a win#to have someone in power be so unwaveringly supportive#the queer community in the spanish state is NEVER gonna forget this. never#anyways!!!#felicidades gente trans española!!!! nos vemos en el registro civil dkkskdkkdkxkdk#mine

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

Its really understandable why the China Poblano is a symbol of Mexican femininity, it’s so elegant and wonderfully colorful!👗

❤️🇲🇽💚

#history#china poblano#mexico#purble#traditional dress#saint#fashion#mexican history#indian style#catarina de san juan#latina#femininity#new spain#latin america#mexican culture#mexican fashion#dress#christianity#girly things#feminine#mexican women#womens history#historical figures#mexican femininity#clothing#historical women#nickys facts

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

#free palestine#gaza#spain#ceasefire now#west bank#jerusalem#middle east#social justice#feminism#lgbtq#palestine#defund israel#israel is a terrorist state#world news#european union

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Key Developments

Israel deploys 15,000 soldiers and military police in West Bank and Jerusalem ahead of Ramadan, including 5,000 reservists, 24 battalions, 20 Border Police companies, and two special forces units.

Hamas’s Izz El-Din Al-Qassam Brigades spokesperson rules out any breakthrough in ceasefire talks, and describes Israel’s position as “deceptive.”

Abu Obaida warns that Israel’s campaign of starvation against Palestinians in Gaza is affecting Israeli captives, some of whom “suffer from hunger, malnutrition and dehydration.”

Izz El-Din Al-Qassam Brigades announces names of four out of seven Israeli captives who died “due to the aggressive Israeli raids on the Gaza Strip.”

25 Palestinian children have died of malnutrition and dehydration since March. The total death toll in Gaza surpasses 31,000 people, 72 percent of whom are women and children.

Gaza City municipality says Israel destroyed a one-million-meter square of roads in the Gaza Strip.

Gaza City municipality needs heavy vehicles and fuel supplies to clean rubble and nearly 70,000 tons of rubbish.

Rescue teams transfer 37 bodies of Palestinian martyrs and 118 injured people to Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir Al-Balah overnight.

U.S. to send army vessel to Eastern Mediterranean to deliver aid and supplies to Gaza.

Wafa reports that Israeli bombing of tents of displaced Palestinians killed 15 people in Al-Mawasi area, west of Khan Younis.

Spain is considering recognizing a Palestinian state by 2027, according to Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez.

#israel#gaza strip#gazaunderattack#israel is a terrorist state#free gaza#genocide#gaza#free palestine#palestine#jerusalem#news#palestine new#rafah#israeli occupation#west bank#fuck israel#yemen#lebanon#tel aviv#spain#2027#hamas#israeli apartheid#boycott israel#this is genocide#stop genocide#cultural genocide#end the genocide#al aqsa storm#free al aqsa

975 notes

·

View notes