#Asian American poetry

Text

A poem by Franny Choi

To the Man Who Shouted “I Like Pork Fried Rice” at Me on the Street

you want to eat me

out. right. what does it taste like

you want to eat me right out

of these jeans & into something

a little cheaper. more digestible.

more bite-sized. more thank you

come: i am greasy

for you. i slick my hair with msg

every morning. i’m bad for you.

got some red-light district between

your teeth. what does it

taste like: a takeout box

between my legs.

plastic bag lady. flimsy white fork

to snap in half. dispose of me.

taste like dried squid. lips puffy

with salt. lips brimming

with foreign so call me

pork. curly-tailed obscenity

been playing in the mud. dirty meat.

worms in your stomach. give you

a fever. dead meat. butchered girl

chopped up & cradled

in styrofoam. you candid cannibal.

you want me bite-sized

no eyes clogging your throat.

but i’ve been watching

from the slaughterhouse. ever since

you named me edible. tossed in

a cookie at the end. lucky man.

go & take what’s yours.

name yourself archaeologist but

listen carefully

to the squelches in

your teeth & hear my sow squeal

scream murder between

molars. watch salt awaken

writhe, synapse.

watch me kick

back to life. watch me tentacles

& teeth. watch me

resurrected electric.

what does it

taste like: revenge

squirming alive in your mouth

strangling you quiet

from the inside out.

Franny Choi

Source: Poetry (March 2014)

Listen to Franny Choi read her poem.

Watch Franny Choi recite a different version of this poem.

More poems by Franny Choi are available through her website.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scabrous streets, dead nerves cushioned deep below.

Jenny Xie, from “The Rupture Tense”, The Rupture Tense

#jenny xie#chinese american poetry#chinese american poets#chinese poets#poetry#asian american poetry#quotes#2020s#the rupture tense#queuetzalcoatlus

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

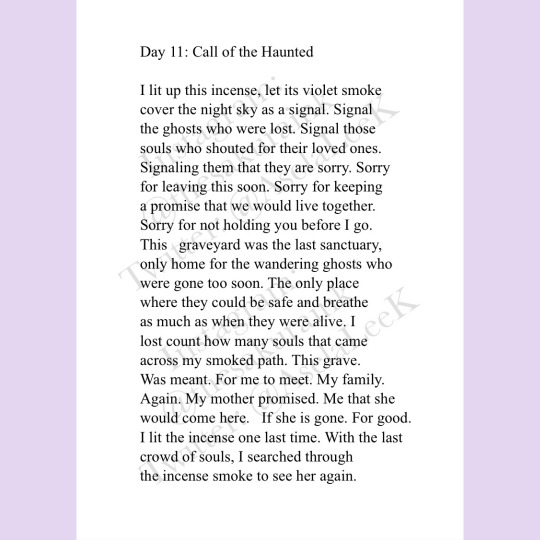

Day 11: Call of the Haunted

Writing this poem was very haunting (bad pun intended), but it really helped me sit with this card and think about how I want to write it. I hope you all enjoy reading this poem to the trap card, Call of the Haunted.

#aselawritewhateverchallenge

#aselawritewhateverchallenge#poetry#poem#asian american#asian american poetry#poetblr#poetry community#female poets#poets corner#poets on tumblr#yu gi oh#yugioh#short poetry#short poem#original poem#dead poets society

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I smack my gum it's to signal

that I do perceive space and time, it's just

I'm kind of over it.

Franny Choi, It's All Fun and Games Until Someone Gains Consciousness

#Franny Choi#Soft Science#It's All Fun and Games#over it#space and time#reality#reality quotes#Asian American literature#Asian American poetry#poetry#poetry quotes#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

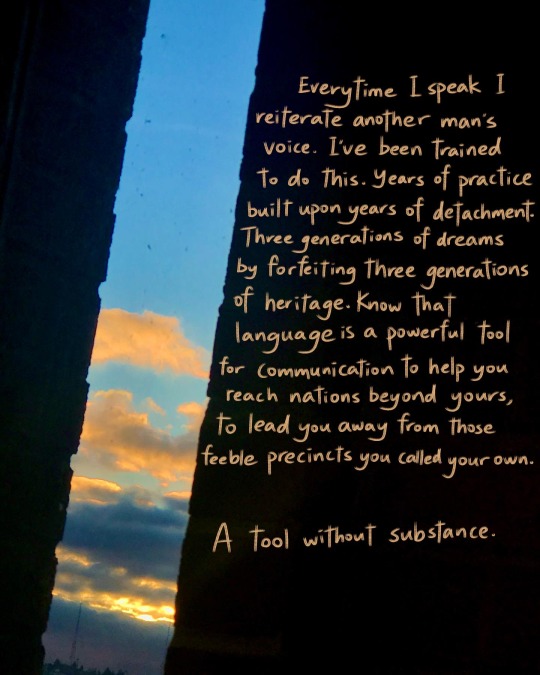

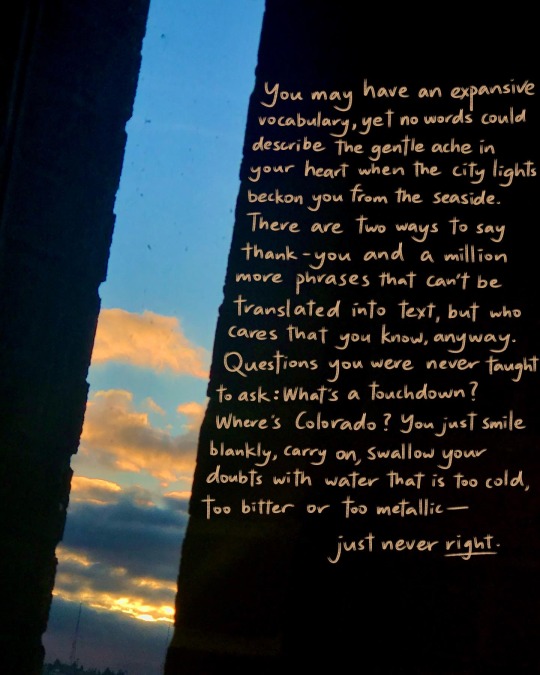

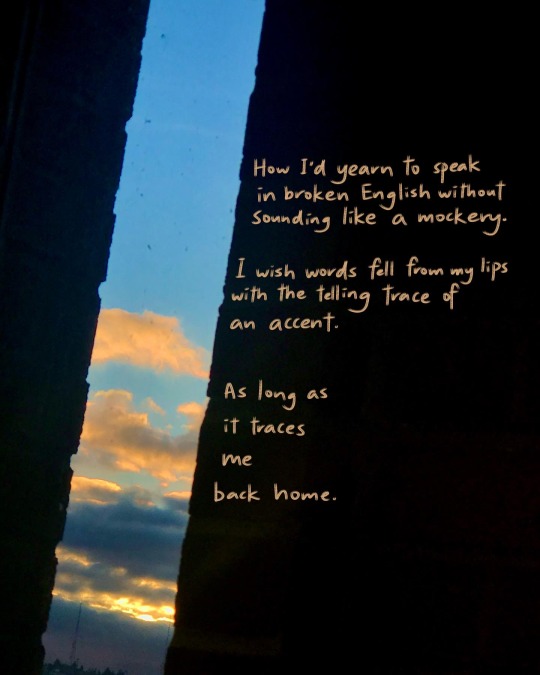

“Part of Them”, a poem about homesickness, language, and cultural dissonance

read here

How did you learn to speak in English so well? How did you effortlessly imitate being a part of them?

Every time I speak I reiterate another man’s voice. I’ve been trained to do this. Years of practice built upon years of detachment. Three generations of dreams by forfeiting three generations of heritage. Know that language is a powerful tool for communication to help you reach nations beyond yours, to lead you away from those feeble precincts you called your own.

A tool without substance.

You may have an expansive vocabulary, yet no words could describe the gentle ache in your heart when the city lights beckon you from the seaside. There are two ways to say thank-you and a million more phrases that can’t be translated to text, but who cares that you know, anyway. Questions you were never taught to ask: What’s a touchdown? Where’s Colorado? You just smile blankly, carry on, swallow your doubts with water that tastes too cold, too bitter or too metallic- just never right.

Here’s the thing they never taught you about homesickness:

The instant you start life anew in a foreign land, you’re too awash with aspirations to notice it.

(But it’ll catch up with you, eventually.)

One day

between the hours of midnight and daybreak

you’ll wake up in a stranger’s bed

As you’re ripped from mirages of those oh-so-familiar streets and faces

And you bawl

you sob

into a cold, dark, empty room

Too many miles away that no ancestor could heed your desperate prayer.

How I’d yearn to speak in broken English without sounding like a mockery.

I wish words fell from my lips with a telling trace of an accent

As long as

it traces

me

back home.

#poetry#spilled ink#spoken word poetry#picture poetry#sunset#sunset photography#lofi photography#language#homesickness#cultural identity#cultural heritage#original poem#poems on tumblr#writing#writblr#handwritten#poemblr#asian american#asian american poetry

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

My mother’s last gift

was to slow dying down

until we could catch up.

Had her death been sudden,

we would have mourned an illusion,

a picture we took and framed

and chose to remember.

We would not have seen

ourselves in the fullness of her light.

- excerpt from My Mother’s Last Gift by Cathy Song

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

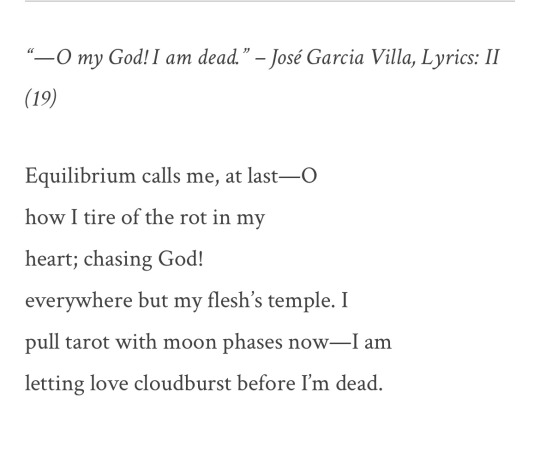

I had a poem published in The Offing last week, titled “Golden Shovel with José and my Tarot Deck”.

#poetry#poem#poets of color#poet of color#bipoc poet#Asian American poetry#poemblr#bipoc poets#my poetry

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

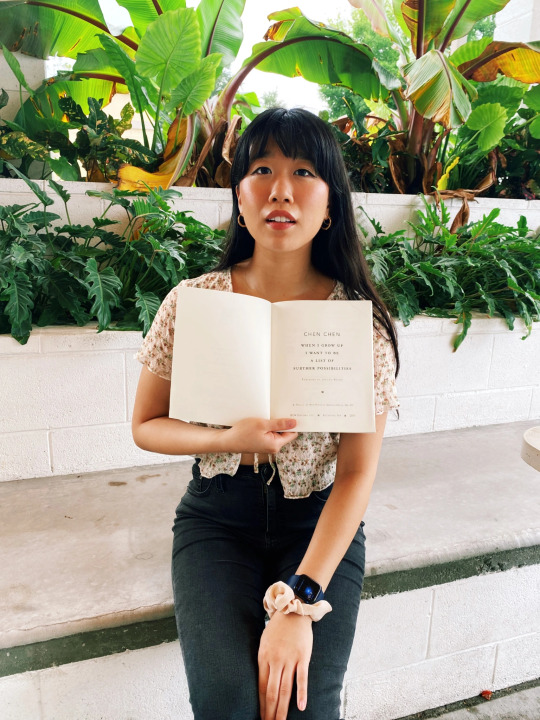

I want this winter

inside my lungs. Inside my brain & dream.

- Chen Chen, Song of the Anti-Sisyphus. From When I Grow up I Want to Be a Further List of Possibilities (2017).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Chinese American Poet, Chen Chen, on being a representative Asian American voice in poetry

HL: Thank you so much for meeting with me! I know in another interview that you said you’re working on saying no, so I’m super grateful that you’re making time for me today. One fun icebreaker question I like to start with is, where did your parents meet?

CC: I don’t know! I should ask them. My parents are both from Southern China—I’m from the city called Xiamen. My mom grew up in the country, and my dad is from the city. So I know that.

HL: Mine met on a ski trip. My mom kept falling so my dad kept having to hold her hand.

CC: Oh my god that’s adorable.

HL: Alright I am just going to go in and start with the heavy questions about race. Do you remember the first moment that you realized you were Asian, and how did this affect your image of yourself?

CC: I grew up feeling a pretty firm sense that I was Chinese because that’s really how my parents identified and would always talk to me in those terms. I saw myself as a Chinese immigrant or a child of immigrants. I was born in China and then came to the States when I was very young. I was about four. So I had that sense of my self, that’s how I saw myself. But the term Asian? It took a while for me to feel like that was descriptive for me because it just seemed so big. It wasn’t until college that I started to think more about identifying in that way—particularly as an Asian American. It’s a term that has its own particular political and cultural history, and I learned a lot more about that in college. Before that, I didn’t know what it meant to call myself Asian American, so that changed things for me.

Just in terms of any racial awareness, I’d say from a pretty young age I was aware of that difference, aware of how different people, non-Asian people, saw me as Asian. I had an awareness of that very early on, but in terms of, you know, just the word, the terminology, it wasn’t until college.

HL: What specifically changed in college?

CC: I became interested in learning about the history of Asian Americans versus Asian people in the United States because I realized that I didn’t know that much. I was also becoming friends with other Asian American students on my campus, and on other campuses, and they were talking about the identity as this pan-ethnic one—you can be East Asian, you can be South Asian, you can be West Asian—and the idea of this political coalition community that could form with this term this umbrella term. So I became interested in learning more about the history of that.

I was becoming interested in seeking out other Asian American writers, particularly poets, because I realized that I hadn’t read that many before. You know that they weren’t taught as much in high school. There are some, but usually they’re fiction, and so I had to seek out a lot of the poetry on my own, too. I remember reading Rose by Li-Young Lee, his first book, in high school at the suggestion of an encouraging English teacher sophomore year. She recommended that I check out Li-Young Lee’s work. I remember looking at the back cover and seeing his author photo on there and being moved—Oh, here is a Chinese American, someone who likes me and is doing this poetry thing. Doing it his own way.

HL: Yeah it’s always the English teachers in high school.

CC: They just get it.

HL: Do you have any unique struggles as an Asian American, and is it amplified by your queer and immigrant identity?

CC: I think so many of us have struggled with this, this kind of invisibility, and in a lot of areas of culture and politics. So I feel I can understand why representation is such a big issue for many Asian Americans. I do think it’s not the only issue, or it doesn’t have to be the primary one. But yeah, I’d say, especially as a queer Asian American with this immigrant experience, that I have very rarely seen this kind of experience depicted anywhere. I feel motivated to depict my own experiences in my writing because of the lack because there’s been such a huge lack.

HL: I went to the library and I specifically asked for Asian American authors, and the librarian could only name Amy Tan and no one else. It was frustrating for me.

CC: It feels like we’re always fighting for that recognition. Other non-Asian people are always behind, either catching up or they have static knowledge about Asian American literature. It just stops developing at a certain point—after they’ve read one author, or two, maybe, and then that’s it. It can be frustrating to see that because there’s such a wealth of literature that I think people are missing out on.

HL: We only read boring old dead white men in high school and college.

CC: So many people just did not move on. I want people to be more curious and also take the initiative to educate themselves because I just think it’s so exciting and enriching what’s happening in Asian American literature.

HL: Do you feel like you feel stuck in your identity as an Asian American poet? For example, I remember when I was reading Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, a collection of essays, she talked about how she felt like no one would take her seriously as an Asian poet.

CC: I do think that some of that has changed in recent years. I feel very lucky to have come up as a poet when I did because there was already a lot more going on in editing and publishing. There were a lot more books by Asian American poets, fiction writers, and non-fiction writers. Just in the last ten years, there’s been an explosion. It’s been great to see that. I didn’t feel as much pressure when my book came out. I didn’t feel like I needed to speak to the Asian American or Chinese American experience in a particular way, which I feel very fortunate about.

In the past, I think there was a lot more pressure. I mean tokenizing still happens, but I think there was a lot more of that. And so there was the sense that to call yourself an Asian American writer can only mean one thing, that you have to represent a whole culture, a whole experience, in a simplified way and a palatable way, mainly for a white mainstream audience. I think that pressure has lessened, to some degree over the years, so I feel fortunate about that.

And also just for me, I feel like identity is just so expansive and so complicated. I feel like I’m continuing to learn. I don’t feel like I can definitively say that being Asian American means X, Y, and Z. Because for me it changes too, at different points in my life, my relationship to that term. On thinking of myself as an Asian American writer, I embrace that label. I don’t find it restrictive really, because there are so many different styles and approaches and subject matter that you could call Asian American literature.

HL: One thing I have been dying to ask you about because I identify with it so much in your debut collection, you talk a lot about your fraught romantic relationships with white boys. I remember in elementary school when I would have a crush on the white boys in the class, I would just automatically assume he wouldn’t like me. I think I’m cute, but I’m not white, so I just automatically assumed he wouldn’t like me. I wanted to ask about how we don’t meet Eurocentric beauty standards. How did that influence your self-image?

CC: I think I internalized a lot of racism, because of that very issue—feeling like I wasn’t up to those beauty standards, those Eurocentric beauty standards, and being socialized to seek the attention of white men. So many of us are socially conditioned to do that in this culture. It’s taken me a long time to examine that, and I think I’m still processing it and examining it and unlearning certain things. Writing has been a way to process those experiences and those emotions. And, yeah, I feel especially in recent years, I’ve become a lot more self-loving. A lot more just embracing as well, of being Asian.

I used to be very self-conscious and embarrassed about how I looked in photographs and I would beat myself up about it, feeling like I’m not attractive or I’m not good-looking in the standard ways. But I love taking selfies. I love posing in photos. I realized that in the past, I used to always make a funny face sort or strike a funny pose in photos. That was my way of getting around my discomfort. But I was looking back on it, and I realized that I was also trying to make other people comfortable. I was overcompensating for this anxiety and this insecurity that I had. And so now, I mean I still love doing funny things in photos, but I feel a lot more comfortable now just taking a regular picture and just looking like myself in photos. That’s taken a long time, to become more comfortable in my own skin.

HL: I think I also used to do the same thing actually, like I would purposely try to make myself look bad in photos so that no one else could be like, oh, that’s not a good photo.

CC: You kind of sabotage it. Or you try to change the tone of it in a way so that it can’t be disappointing because it’s already funny or weird.

HL: One more poetry question! As a poet, you tend to capitalize on really striking emotional moments in your life. Your poem, “Race to the Tree,” was very emotional for me to read. Is there any cost to tapping into this vulnerability? Are you ever afraid to release a poem into the world?

CC: Yeah, I do get nervous. I remember before this book was published, the first full-length book, I published these two chapbooks—much shorter collections—and the first one set the car on fire. It’s extremely autobiographical, personal poems, a lot about my family, a lot about being an immigrant, and a lot about sexuality. An earlier version of that poem that you just mentioned, “Race To The Tree,” is in that chapbook. I remember getting the galleys for that chapbook—the physical copy that the publisher sends you. It’s not the finished book yet, so it didn’t have the cover on it, but it was bound. Holding it in my hands for the first time, I vividly remember freaking out. Both in a good way, I was super excited, but also I was super nervous at the same time. It hit me that, oh, this is gonna go into the world. It’s still a small publication—this is a chapbook from this tiny press, but still, it just suddenly felt very real.

I had a similar feeling with the first book, although by that point I’d gotten used to it a bit. It takes some practice. In writing, I often tell my students this can be a really good sign. If you do feel scared about what you’re writing about or how you’re writing about it, it can be a good sign that you’re tapping into something complicated, not neatly resolved. It’s still this messy set of emotions that’s brought up for you. So, because of all that, usually, it leads to some good writing. But at the same time, I advise people to take care of themselves as well. Don’t push it if you’re not ready to, but if it feels urgent to you to go there, just allow yourself to do it in a certain way where it doesn’t harm you, ultimately, to be writing about those difficult subjects.

HL: When I write I want to tap into old relationships that ended badly, but I don’t want to annihilate people along the way. Do your parents ever get upset that you mention very intimate moments with them in your poems?

CC: They haven’t really mentioned anything. I think it does bother them sometimes, but I feel like especially at this point they get that I am my own person. I’m an adult now. I’m saying making my own choices. But I guess I always try to make it clear, too, that I’m trying to tell my own piece of the story. You know, like they’re often in the story that I’m writing about, but it’s my personal, subjective experience of it. I try to always focus on what has been my experience of our relationship—my relationship with them, rather than other aspects of their lives which I don’t feel I have as much access to. That’s where the focus is, and I hope that they understand that.

HL: Wow I learned so much about you and your writing, and it was very cool. Thank you! Can we take a selfie?

CC: For sure!

HL: I’ve been telling my friends about it, and they’re like: “Oh my gosh that’s so cool you get to interview Chen Chen.” How should we pose? What should we do?

CC: Let’s do one serious and one more playful. So let’s do the serious one first.

HL: Okay what should we do for playful?

CC: (Displays peace sign.)

HL: Thank you Chen!

CC: Thank you for your questions! It was so nice to talk.

HL: Do you have any parting words of wisdom? What’s your secret sauce to life?

CC: Sleep. Take naps if you feel like it. Eat good snacks. I feel like I’m turning into my mom a bit, because now what I want to tell everybody and tell myself, remind myself, is that you have to take care of your body, before you can do other things—to make sure that you’re eating well, getting enough rest. Because I used to not take that so seriously, but now I feel like it’s really important.

HL: Now that I’ve reached my mid-twenties, I feel like I can’t get away with stuff that I used to in the past.

CC: Yeah, I think it’s you just feel better all-around when you’re not trying to push through things all the time, and you’re making time to take care of yourself.

HL: Alright, so take naps and eat good food. Well, I hope you have a wonderful rest of your day!

CC: Thank you! Yeah! It was great to talk.

HL: Ah I don’t know how to end this.

CC: Yeah on Zoom it’s always kind of funny. Alright, see you!

0 notes

Text

Review of “A Marriage at Ancestral Hall in Sun Village” by Shelley Wong

Shelley Wonghttp://www.shelley-wong.comj’s “A Marriage at Ancestral Hall in Sun Village” is a poignant and evocative prose poem that delves into the rich tapestry of East Asian history, culture, and the immigrant experience. The poem is a testament to Wong’s mastery in blending personal and historical narratives, creating a piece that resonates deeply with themes of identity, diaspora, and…

View On WordPress

#A Marriage at Ancestral Hall in Sun Village#Angel Island#Asian American diaspora#Asian American identity#Asian American poetry#Asian cultural references#Asian women in America#Chinese immigrant narratives#Contemporary Asian American literature#Cultural identity#Cultural symbolism in poetry#Diaspora literature#Earthquake#East Asian history#Emotional depth in literature#Feminine symbolism#Gender themes in poetry#Historical context in poetry#Immigrant experience#Immigrant sacrifices#Lambda Literary Award#Narrative structure in poetry#Page Act#Personal and historical narratives#Poetic imagery#Poetic review#prose poem#Queer Chinese American poet#Shelley Wong#Shelley Wong achievements

1 note

·

View note

Text

I cannot do without love / the way I make myself / do without food or sleep or sex / I cannot do without love

Kitty Tsui, Without love

#kitty tsui#poetry#poem#love#love poem#asian american#asian american poetry#lesbian#lesbian poetry#lesbian poet#words of love#words to live by#love lexicon

1 note

·

View note

Text

A poem by Li-Young Lee

To Hold

So we’re dust. In the meantime, my wife and I

make the bed. Holding opposite edges of the sheet,

we raise it, billowing, then pull it tight,

measuring by eye as it falls into alignment

between us. We tug, fold, tuck. And if I’m lucky,

she’ll remember a recent dream and tell me.

One day we’ll lie down and not get up.

One day, all we guard will be surrendered.

Until then, we’ll go on learning to recognize

what we love, and what it takes

to tend what isn’t for our having.

So often, fear has led me

to abandon what I know I must relinquish

in time. But for the moment,

I’ll listen to her dream,

and she to mine, our mutual hearing calling

more and more detail into the light

of a joint and fragile keeping.

Li-Young Lee

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

She sews the streets together with hurried steps

Jenny Xie, from “The Rupture Tense”, The Rupture Tense

#chinese american poets#jenny xie#chinese poets#chinese american poetry#poetry#asian american poetry#quotes#2020s#the rupture tense#queuetzalcoatlus

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

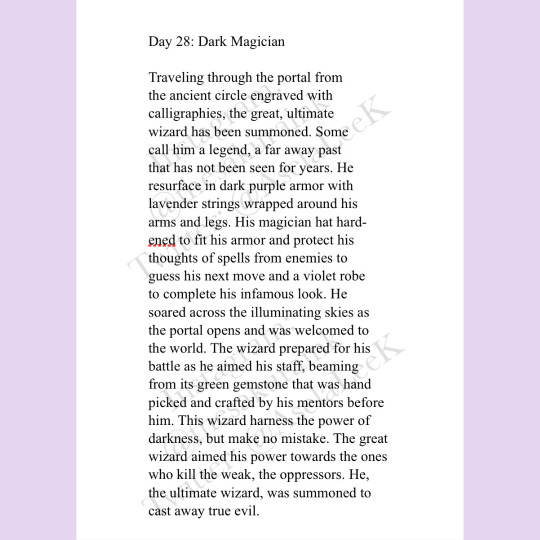

Day 28: Dark Magician

We’re a day away from the last day of AWWC. And what better way to celebrate with a poem to one of the greatest cards in Yu-Gi-Oh!: Dark Magician. I hope you all enjoy reading this piece!

#aselawritewhateverchallenge

#aselawritewhateverchallenge#poetry#poem#asian american#asian american poetry#poetblr#poetry community#female poets#poets corner#poets on tumblr#yu gi oh#yugioh#short poetry#short poem#original poem#dead poets society#writers and poets#poetsandwriters#poetscommunity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I follow the maze, push-brooming forest floor with face, followed the promise of a rapid heart. Don't ask who's the bloodhound, who's the hare, when there's a chase to be made: the clarity of a cardinal direction clicking into place. And: the quickening--the tendons that appear, sudden, when the distant, rabid howl of hunters roll across the tree line, and you lift your head in greeting.

Franny Choi, Hunter's Moon

#Franny Choi#Hunter's Moon#hunter#hunting#hunt#chase#transformation#moon#moon quotes#Asian American literature#Asian American poetry#poetry#poetry quotes#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature

21 notes

·

View notes

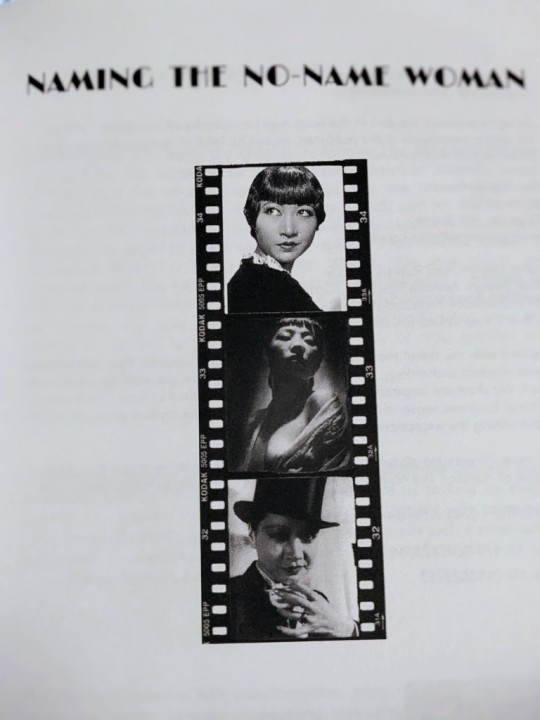

Photo

(via The Sealey Challenge: Naming the No-Name Woman)

#naming the no-name woman#Anna May Wong#Wong Liu Tsong#the sealey challenge#Jasmine An#Two Sylvias Press#Two Sylvias Press Chapbook Prize#queer poetry#Asian American poetry#Chinese American poetry

0 notes