#Classical Greek Philosophy

Text

I love you people going into "useless" fields I love you classics majors I love you cultural studies majors I love you comparative literature majors I love you film studies majors I love you near eastern religions majors I love you Greek, Latin, and Hebrew majors I love you ethnic studies I love you people going into any and all small field that isn't considered lucrative in our rotting capitalist society please never stop keeping the sacred flame of knowledge for the sake of knowledge and understanding humanity and not merely for the sake of money alive

#classics#mythology#ancient greek mythology#ancient roman mythology#comparative literature#latin#hebrew#ethnic studies#fuck capitalism#communism#i love my useless degree idc#academia#university#dark academia#Greek#philosophy#liberal arts#humanities#women and gender studies#cultural anthropology

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Human beings exist for the sake of one another: so, either teach them or endure them.

Οἱ ἄνθρωποι γεγόνασιν ἀλλήλων ἕνεκεν: ἢ δίδασκε οὖν ἢ φέρε.

--Marcus Aurelius, Meditations VIII.59

#quote#quotes#classics#tagamemnon#Marcus Aurelius#Meditations#philosophy#ancient philosophy#Stoicism#Greek#Greek language#Greek translation#Ancient Greek#Ancient Greek language#Ancient Greek translation

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

γνῶθι σαὐτὸν (know thyself)

(credit to my friend michelle for this banger of a meme)

701 notes

·

View notes

Text

—sisyphus

unknown source // titian, sisyphus // albert camus, the myth of sisyphus

#sisyphus#albert camus#quotes#web weaving#painting#art#philosophy#art detail#classic art#greek mythology#mythology#aesthetic moodboard#dark academia aesthetic#classic academia#chaotic academia#dark academia#booklr#absurdism#literature#french literature#my posts#first quote is commonly attributed to camus but i haven't actually found the source material#and apparently in france they believe it to be by zygmunt bauman writing about camus so#anyone's welcome to prove me wrong but im putting it at unknown in the meantime

362 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mhm#Film scenes#film stills#chaotic academia#books and literature#introvert#human interaction#relatble?#academia#classic academia#marauders#the secret history#greek mythology#philosophy#dark academia#politics#anxiety creature#humans are strange#I’m tired#anyway <3

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside every classics major are two wolves. One is alcibiades (whore with hubris) and one is diogenes (hates plato)

#alternatively there are two genders#ancient greek#ancient history#classics#tagamemnon#alcibiades#diogenes#philosophy

375 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am a dreamer. I know so little of real life that I just can’t help re-living such moments as these in my dreams, for such moments are something I have very rarely experienced. I am going to dream about you the whole night, the whole week, the whole year.

White Nights, Fyodor Dostoevsky

#classic literature#russian literature#dark academia aesthetic#dark academia#english literature#Literature quotes#Franz Kafka#dead poets society#cottage core aesthetic#the secret history#painting#Oscar Wilde#Song of Achilles#Greek Mythology#light academia aesthetic#philosophy#poetry#jane austen#Romanticism#Ancient Rome#love quotes#Art#taylor swift#Existentialism#nihilism#friedrich nietzsche#book aesthetic#aesthetic#richard siken#henry winter

128 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Philosophy, History and Prudence Awakening the Mind to a Desire for Knowledge (c. 1624) by Alessandro Turchi.

#art#aesthetic#painting#artwork#art history#dark academia#mythology#light academia#greek mythology#dark aesthetic#romantic academia#dark art#greek gods#oil painting#renaissance#baroque#fine art#classical art#philosophy#history and prudence awakening the mind to a desire for knowledge#alessandro turchi

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

#philosophy#dark academia#light academia#classic academia#booksbooksbooks#learners#ancient greek#history#ancient#brown#brown aesthetic#cottagecore#quotes#books#artblr#aesthetic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The gods are not aware of us. That’s what I like most about Aristotle’s cosmology. The gods are perfect, and therefore they only think about perfect things (themselves). We are imperfect, therefore we are not worth thinking about. They don’t know that they caused us.

You’re probably more familiar with the Olympians—figures like Zeus, Athena, and Poseidon, the sort of Greek gods that appear in Percy Jackson or Disney’s Hercules. Those gods are deeply invested in human affairs. Homer portrays the gods sponsoring armies, and making alliances with humans. Aeschylus has Athena begin democracy. They have children with us, they accept offerings from us, they even lash out at us in judgment. But Ancient Greece was a huge civilization that lasted an incredibly long time. Sometimes they disagreed with each other.

For Aristotle, praying to the gods can’t ensure a good harvest or military success. It can’t even get their attention. We are able to relate to the gods, but it is a completely one-sided relationship. If your motivation for practicing religion is purely transactional, then there is no reason to care about these solipsistic prime movers. But for Aristotle, the gods can help us achieve virtue.

We can imitate them. We will never win their favor, we will never have their love, but we can follow their example. Although we will never be perfect, we can observe perfection and try to learn from it. We can be a little better than we are today. Perhaps that is enough.

#Im NOT saying this is better than religions with a personal or devotional or transactional god#but it’s a fascinating position#if your religion is important to you then one way to nurture your religiosity#is to compare and contrast with the alternative religions and spirituality#so if you have a devotional religious practice#then this is good to know about#this is NOT a knock on Percy Jackson#shoutout to rick riordan fr#gotta be one of my favorite young adult authors#I’m just saying he didn’t have time to cover every single theological position ever held by an Ancient Greek#nate's writing#philosophy#greek philosophy#classical theism#god#aristotle#original post

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't live as if you'll live ten thousand years. Necessity looms above you: while you're alive, while it's possible, become good.

Μὴ ὡς μύρια μέλλων ἔτη ζῆν. τὸ χρεὼν ἐπήρτηται: ἕως ζῇς, ἕως ἔξεστιν, ἀγαθὸς γενοῦ.

--Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 4.17

#quote#quotes#classics#tagamemnon#ancient philosophy#Stoicism#Marcus Aurelius#Greek#Greek language#Greek translation#Ancient Greek#Ancient Greek language#Ancient Greek translation

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

My cover illustration for "The Bloomsbury Handbook of Plato"

I was lucky enough to be contacted by Mateo Duque, one of the editors for the book, and we had a really exciting collaboration to come up with this cover image.

In the sky we have the symbolism for Platos "platonic solids" (polyhedra with identical faces) and Socrates is having a dialogue with Phaedrus under a plane tree alongside the Ilissos river. In the distance is the Acropolis of Athens with a swan in flight, a bird that was associated with Apollo and Plato associated the swan with himself, saying that the swan sang most beautifully nearest death.

This was a dream commission. I hope to get more projects like this in the future. What an honor to do a Plato cover for such a respected publishing company like Bloomsbury!🙌😁🤟❤ a true high point of my illustration career thus far.

If you could share this image with your followers it makes a big difference for exposure and gaining more commission work. As always, your support is everything. xoxo love you all!

#hellenism#greek mythology#tagamemnon#mythology tag#percyjackson#classicscommunity#dark academia#greek#greekmyths#classical literature#plato#socrates#bloomsbury#bloomsburypublishing#ancient philosophy#philosophy#greek philosophy#greece

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

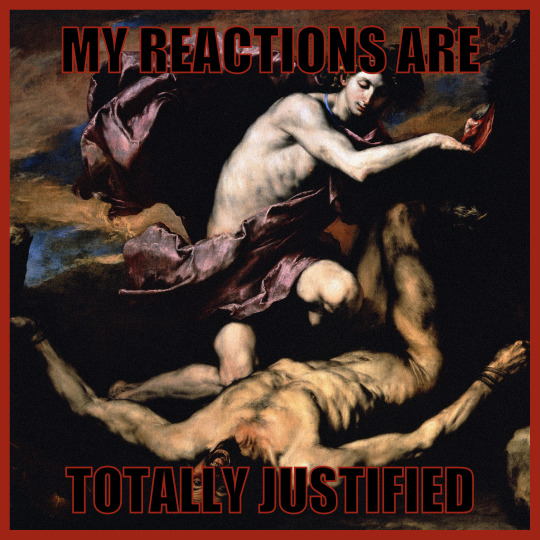

tonight at the woodshed:

#affirmations#saschirmations#classics#classical art#greek mythology#apollo#marsyas#philosophy#plato#cultist simulator#edge and winter moment with a characteristic dash of moth and grail#the wolf divided#tarot#the moon#werewolf moment ladies#saint sebastian#catherine howard#katherine howard#dnd#dominate monster

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Του βίου καθάπερ αγάλματος πάντα τα μέρη καλά είναι δει.

- Socrates

Like in a statue, all parts of a life must be beautiful.

84 notes

·

View notes

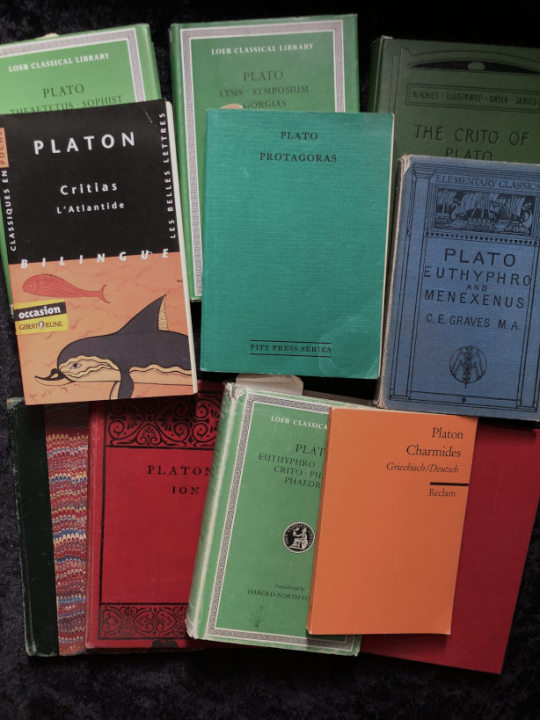

Text

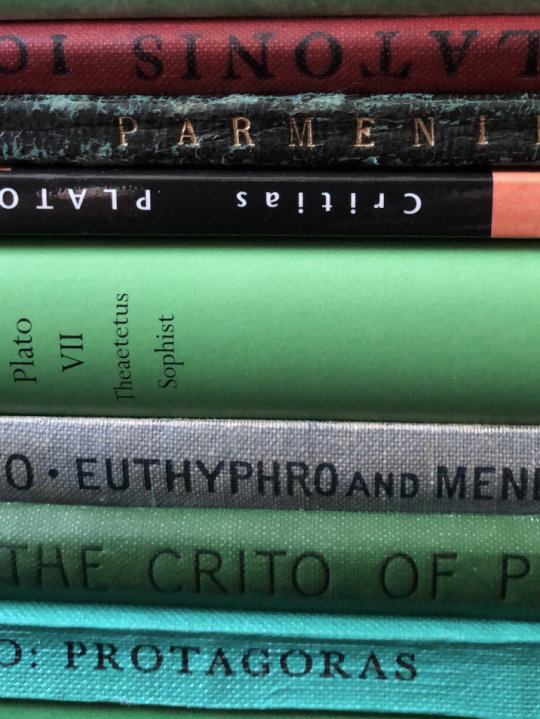

#platonic love#plato#platon#dark acadamia aesthetic#dark academia#classic academia#classics#grey academia#classical studies#books#book photography#old books#philosophy#philosophie#ancient greek#ἐποίησα

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Divine Epithets: How We Can Use Mythology to Learn About Human Authenticity

WC: 2,504

Disclaimer: I wish to clarify that my exploration of mythology and spirituality/religion is undertaken with the aim of understanding myself and my interactions with others, similar to how I use philosophy for the same purpose. It is important to note that I am not a theologian, and I do not claim to offer definitive or universally accepted interpretations of these myths or religious texts. My interpretations of mythological narratives and religious symbolism are personal reflections based on my own pagan beliefs, cultural background, education, and experiences. I acknowledge that interpretations of myths and religious texts can vary widely among individuals and communities, and my perspectives can and will differ from those of others. I encourage readers who are interested in exploring these culturally rich stories and lessons to engage in their own research and critical inquiry. Ultimately, my goal is to foster curiosity, dialogue, and self-reflection, rather than to impose a singular interpretation or belief. I invite readers to approach these topics with an open mind and a willingness to explore the diverse and complex tapestry of human culture and spirituality.

Introduction

In my last post, I talked about the Obsessed Artist and how it is a reflection of the human pursuit of authenticity. I wanted to talk about another aspect of literature that many of us are fans of that also reflect that aspect of philosophy.

Authenticity, a cornerstone of human existence, embodies the alignment between one's actions, beliefs, and values. It reflects the quest for inner harmony and integrity, wherein individuals strive to live in accordance with their true selves. Furthermore, philosophical ideals surrounding authenticity provide a conceptual framework for understanding the complexities of human identity and self-expression. Existentialist thinkers like Sartre and Heidegger offer insights into the existential angst and quest for authenticity inherent in human existence. Sartre’s concept of “bad faith” highlights the tendency to adopt inauthentic roles and identities imposed by societal norms, while Heidegger’s notion of “authenticity” calls for enacting roles and expressing character traits that contribute to realizing some image of what it is to be human in our own cases.

Yet, the pursuit of authenticity is not confined to the realm of human experience alone; it permeates the narratives of divine beings across various religious traditions. For example, as I’ve mentioned in previous posts, Kierkegaard held authenticity as a matter of passionate commitment to a relation to something outside oneself that bestows one’s life with meaning.

Divine epithets, ranging from the majestic “Aegidu’chos” (bearer of the Aegis with which he strikes terror into the impious and his enemies) attributed to Zeus in Greek mythology to the “Lamb of God” associated with Jesus Christ, encapsulate the essence of divinity within linguistic constructs. These epithets are not mere labels but serve as portals into the complex and nuanced understanding of gods.

Thus, the exploration of authenticity through divine epithets opens up a Pandora’s box of philosophical inquiry, inviting us to interrogate the nature of identity, selfhood, and the human condition. By traversing through the historical, cultural, and philosophical landscapes surrounding divine epithets, we embark on a transformative journey that promises to illuminate new pathways for understanding the enigma of authenticity in both human and divine realms.

Authenticity and Divine Epithets

Epithets associated with gods across various religious traditions serve as linguistic manifestations of divine attributes, functions, and qualities. Through the lens of authenticity, these divine epithets reveal deeper layers of meaning, reflecting not only the divine nature but also the human longing for spiritual authenticity and connection.

At its core, authenticity involves the alignment between one’s inner self and outward expression, reflecting sincerity, integrity, and congruence in beliefs, values, and actions. When applied to the culture around bestowing various epithets among deities, authenticity invites contemplation on the genuineness of human-divine relationships mediated through religious language and symbolism.

For example, in Greek mythology, Hermes is known by a plethora of epithets, each revealing a different facet of his character and function. For instance, Argeiphontês, by which he is designated as the murderer of Argus Panoptes, embodies the role of his ability to overcome obstacles through wit, guile, and ingenuity rather than brute force. It also alludes to Hermes’s role as a psychopomp, a guide of souls. In some interpretations, Argus, with his many eyes, symbolizes the all-seeing gaze of death, suggesting that Hermes’s slaying of Argus represents his function as a guide of souls, leading the deceased safely to the underworld.

The epithet “Argeiphontês,” then, can imply several aspects of human authenticity when examined within the context of Greek mythology and the character of Hermes.

Cunning and Resourcefulness: Hermes’s epithet as “Argeiphontês,” underscores his ability to navigate challenges through wit, cunning, and resourcefulness. In the human realm, authenticity can be expressed through similar traits, such as creativity, adaptability, and the ability to think outside the box. Humans who embody authenticity may demonstrate a willingness to confront obstacles with ingenuity and innovation rather than relying solely on conventional methods.

Individuality and Non-Conformity: Hermes’s role as a trickster figure challenges conventional notions of divine behavior, highlighting the importance of individuality and non-conformity in the pursuit of authenticity. Similarly, human authenticity may involve the rejection of societal norms and expectations in favor of embracing one’s unique identity and values. Authentic individuals may resist pressures to conform and instead strive to live in alignment with their true selves, even if it means deviating from societal conventions.

Quest for Meaning and Purpose: As per the second interpretation of the myth, “Argeiphontês” is intertwined with his role as a guide of souls, reflecting a deeper existential dimension related to the journey of life and death. Human authenticity often involves a similar quest for meaning and purpose, as individuals seek to understand their place in the world and navigate the existential challenges of existence. Authenticity may entail a sincere exploration of one’s beliefs, values, and aspirations, as well as a commitment to living in alignment with one's sense of purpose and meaning.

Furthermore, the authenticity behind divine epithets is intimately tied to the human expression of religious experiences. For believers, the use of epithets in prayer, meditation, or ritual serves as a means of forging a genuine and intimate connection with the divine. Through the repetition and contemplation of divine epithets, individuals seek to cultivate their understanding of the human experience in their religious practice, aligning their innermost beliefs and desires with the divine presence.

However, the quest for authenticity in divine epithets is not without its challenges and complexities. In some cases, the proliferation of epithets and theological interpretations may lead to tensions or conflicts within religious communities. Debates over the validity of certain epithets or theological doctrines may arise, reflecting differing interpretations of religious texts and traditions.

Take the myth of Medusa, from her origins as a Gorgon to the later narrative of her being cursed by Athena. In her earliest depictions, Medusa was portrayed as being born as one of the Gorgons, monstrous beings with snakes for hair, whose gaze could turn onlookers to stone. The Gorgons were often associated with chaos, danger, and the darker aspects of the natural world. In this context, Medusa’s monstrous form can be interpreted as a symbolic representation of primal forces beyond human comprehension or control. Her terrifying appearance reflects humanity’s fear of the unknown and the inherent unpredictability of the natural world. The stories of heroes like Perseus can symbolize the ideals of heroism and bravery triumphing over these uncertainties, asserting human agency despite otherworldly magic.

As the myth of Medusa evolved over time, her character underwent a transformation, particularly with the introduction of the narrative in which she is cursed by Athena, which wasn’t written until Ovid. According to this version of the myth, Medusa was originally a beautiful maiden who caught the unwanted eye of Poseidon, the sea god. In a fit of rage, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and warfare, transformed Medusa into a Gorgon, cursing her with a hideous appearance and the power to turn others to stone with her gaze.

The shift in Medusa’s characterization from a Gorgon to a cursed mortal reflects broader changes in cultural attitudes towards femininity, power, and agency. In this later version of the myth, Medusa becomes a tragic figure, victimized by the capricious actions of powerful deities. Her transformation into a monster is depicted as an act of divine punishment rather than an inherent aspect of her nature. This narrative underscores the complexities of human identity and the ways in which external forces, including societal expectations and divine intervention, can shape individual authenticity.

On the other hand, the myth also raises questions about the authenticity of religious or spiritual explanations for human behavior and experiences. In being distant from the source material of the original mythology as well as the writers of each transformative myth, we are left with interpretations of interpretations. In this sense, one must question how valid our understanding of human nature is through these stories when we are unable to solidify a concrete narrative.

On one hand, the evolution of Medusa’s character highlights the role of mythology and religious belief systems in shaping cultural narratives about identity, morality, and the conditions in which humans, as a society, progress forward.

Historical and Cultural Context

By examining these mythological narratives within their historical and cultural contexts, we can attempt to answer that question. To understand the significance of divine epithets, it is crucial to consider the historical and cultural contexts in which they originated. Using Hermes as an example again, in ancient Greece, he occupied a central role in religious and everyday life.

The epithet “Hermes Psychopompos,” for instance, emerges from ancient Greek funerary rituals and beliefs about the afterlife. In ancient Greek society, death was regarded as a significant transition, and rituals surrounding funerary practices were deeply ingrained in cultural and religious traditions. Hermes’s role as a guide of souls, as reflected in the epithet “Psychopompos,” underscores the Greeks’ reverence for Hermes as a mediator between the realms of the living and the dead. This epithet not only highlights the cultural significance of death and the afterlife but also offers insights into the Greeks’ understanding of humanity in relation to mortality. The guidance of souls by Hermes suggests a belief in the importance of the transition from life to death.

As for Ovid’s myth of Medusa being turned into a Gorgon by Athena, Ovid wrote Metamorphoses in exile and used his writing as a form of rebellion against the Roman government. He wove subtle criticisms and subversive messages throughout his work. The use of mythological narratives and divine figures in Metamorphoses provided Ovid with a powerful tool to critique the moral and political landscape of Rome, while also offering a means of catharsis and self-expression. The question then lies in our modern use of this version of the myth in serving other narratives and perpetuating aspects of human nature and authenticity while ignoring the historical context in which it originates. How valid can our interpretations be when citing works that have the intention of “divine defamation?” Or, on the other hand, does Ovid’s equating of the gods to authority figures represent his own search for understanding human nature?

The Fluidity of Authenticity

The concept of authenticity is often perceived as a static state, wherein an individual’s actions, beliefs, and values align consistently with their inner self. However, the exploration of divine epithets within mythology offers a different perspective, one that emphasizes the fluidity and dynamism inherent in authenticity. Just as gods in various religious traditions are represented by multiple epithets, each expressing a different facet of their identity and attributes, humans similarly navigate a multiplicity of identities and roles throughout their lives.

Jean-Paul Sartre, as a matter of fact, rejects the idea of a fixed, predetermined essence or identity for individuals, arguing instead that human existence is characterized by radical freedom and responsibility. In his work Being and Nothingness, Sartre famously asserts that “existence precedes essence,” meaning that individuals first exist as free agents and then define themselves through their actions and choices.

According to Sartre, authenticity involves embracing this freedom and taking responsibility for one’s choices, even in the face of uncertainty and ambiguity (re: Perseus and Medusa). Authenticity, in Sartrean terms, is not a static state but rather an ongoing process of self-definition and self-expression. Individuals must constantly negotiate and reevaluate their values, beliefs, and identities in light of their changing circumstances and experiences.

The fluidity of authenticity, as highlighted by divine epithets and thinkers like Sartre, suggests that authenticity is not a fixed destination but rather a journey of self-discovery and self-expression. Like gods who embody diverse aspects of existence through their epithets, humans traverse a complex landscape of identities, values, and beliefs, constantly negotiating and reevaluating their sense of self. The journey of authenticity involves constant negotiation and reevaluation of one’s values and beliefs, as individuals seek to align their actions with their innermost selves amidst the complexities of life. This process is not linear but rather recursive, characterized by periods of growth, introspection, and transformation. Just as gods are represented by multiple epithets, each expressing a different aspect of their divine nature, humans too embrace a diversity of identities and roles, each contributing to the richness and complexity of their authentic selves.

Authenticity and Relationality

The concept of authenticity is also inherently intertwined with relationality, as it is not solely an individual pursuit but emerges within the context of interpersonal relationships, whether it is with the divine or with other humans. The study of divine epithets sheds light on this relational nature of authenticity, as epithets serve as descriptors of divine attributes and functions that emerge within the dynamic interplay between gods and humans.

Epithets, by their very nature, are relational in that they depict the roles, qualities, and interactions of gods within the divine-human framework. For example, the epithet “Hermes Agoraios” originates from the agora, the bustling marketplace that served as a hub of economic and social activity in ancient Greek society. As a patron of commerce and social exchange, Hermes played a crucial role in facilitating trade and transactions, reflecting the economic and social dynamics of the time. The epithet “Agoraios” not only reflects Hermes’s multifaceted nature but also speaks to broader societal values and aspirations related to commerce, community, and social interaction.

Authenticity, therefore, involves not only the alignment between one's inner self and outward expression but also the recognition and validation of that authenticity by others.

Aristotle, a foundational figure in Western philosophy, explored the nature of human identity and virtue in his ethical treatises, particularly in his work Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” or “flourishing,” emphasizes the importance of living in accordance with one’s true nature and fulfilling one's potential as a human being.

According to Aristotle, authenticity involves living virtuously and in accordance with one’s telos, or purpose. Each individual has a unique set of virtues and talents that contribute to their fulfillment and flourishing. Authenticity, in Aristotelian terms, is achieved when individuals cultivate and express these virtues in their actions and interactions with others.

However, Aristotle also emphasizes the importance of social relationships and the role of others in the cultivation of virtue and authenticity. In his concept of friendship (philia), Aristotle argues that genuine friendships are based on mutual recognition and affirmation of each other’s virtues and qualities. Friends serve as mirrors to one another, reflecting and validating each other’s authentic selves.

In this sense, authenticity involves not only the alignment between one’s inner self and outward expression but also the recognition and validation of that authenticity by others, particularly in the context of friendships and social relationships. Authenticity, in accordance with Aristotle’s teachings, is not a solitary endeavor but is cultivated and affirmed through meaningful connections with others who recognize and appreciate one's virtues and qualities.

Conclusion

In essence, the study of divine epithets offers a rich and nuanced framework for exploring the complexities of human existence. By unraveling the historical, cultural, and philosophical dimensions of divine epithets, we gain valuable insights into the nature of identity, self-expression, and relationality, illuminating new pathways for philosophical inquiry into the ongoing enigma of our authentic selves. As we continue to grapple with the intricacies of this notion, the exploration of divine epithets serves as a guiding light, inviting us to engage in meaningful dialogue and reflection on the essence of what it means to be authentically human.

#philosophy#ethics#existence#authenticity#authentic self#experience#greek mythology#mythology and folklore#mythology inspired#myth#classical mythology#mythology#myths and legends#gods#paganblr#hellenic pagan#pagan witch#paganism#pagan#pagans of tumblr#pagan community#pagan blog#hellenic polythiest#hellenic deities#hellenism#hellenic polytheism#hellenic gods#hellenismos

10 notes

·

View notes