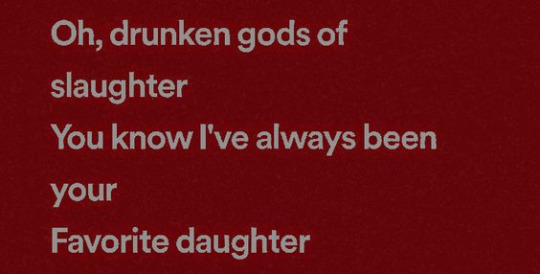

#why we write

Photo

Are you writing this month, Wrimo? Check out our “I wrote a novel… now what?” resources over on the NaNoWriMo website for tips on choosing your next writing adventure: whether that’s finishing a story you’ve been working on for a while, editing and revising, pursuing publishing... or something completely different! For some extra inspiration, author Sarah Gailey’s Pep Talk from this past November reminds you to find joy in the reasons you write. Read the full Pep Talk here!

Image description: A blue background with illustrated red flowers, with text that reads: “The worst part of not writing is that writing always lingers at the edges of it. There’s a prickle on the back of my neck when I’m not writing, an unanswered-message feeling. Because the story is waiting.” —Sarah Gailey”

#nanowrimo#writing#writing inspiration#writing quote#why we write#pep talk#by pep talker#sarah gailey

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folk tales and fairy tales, originating in oral traditions, initially functioned as vessels for cultural transmission, imparting societal norms and moral lessons. Evolving over time, these narratives transformed into dynamic expressions of individual desires and dreams, seamlessly adapting to changing societies. As cultural landscapes shifted, folk tales incorporated contemporary fears and desires, serving as mirrors to the collective consciousness of each era. In modern storytelling, these ancient motifs persist, shaping narratives across literature, film, and other stories. The use of allusions to these timeless tales becomes a vital thread connecting generations, illustrating the enduring and universal nature of storytelling as a profound means of expressing the human experience. From guiding societal values to articulating personal aspirations, folk tales continue to play a crucial role, and their allusions serve as bridges across the ages, enriching the craft of human storytelling.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

my lil baby ao3 account is a year old today and a year ago the end of this month is when i posted my first fic and so i wanted to take the opportunity to share this essay: Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore on Writing on Your Own Terms.

When we write on our own terms, with all the specificity, nuance, complication, messiness, contradiction, emotion, confusion, weirdness, devastation, wildness and intimacy, when we write against the demand for closure or explication, we write against the canonical imperative, and instead write toward the people who might actually appreciate our work on its own terms. I mean we write toward our selves.

Over and over again we are told that in order to make our work accessible, we have to speak to an imagined center where the terms are still basically straight, white, male, and Christian. When we write on our own terms, and by this I mean when we reject the gatekeepers who tell us we must diminish our work in order for it to matter, we may be kept out of the centers of power and attention, this is for sure. And yet, if writing is what keeps us alive—and I mean this literally—if writing is what allows us to dream, to engage with the world, to say everything that it feels like we cannot say, everything that makes us feel like we might die if we say it, and yet we say it, so we can go on living—if this is what writing means, then we need to write on our own terms, don’t we?

Nothing is universal, not even the period at the end of this sentence. (…) Sure, we all experience rain, sun, water, earth. But as soon as we write about them, they change too. Try it. See if we can all agree about any of this. Eileen Myles writes, “As soon as I hit the keyboard I’m lying,” and we all know the truth in this.

Often writers ask me about how to write about people they know, what to keep in and what to keep out. And my first answer is always: write everything. Write it all. Especially the parts you are most worried about. You can decide later what to keep, but don’t hold yourself back, because then you’re censoring your work before it even has a chance to exist on the page. Before it has a chance to grow.

Maybe it’s about me, and maybe it’s about you. We are always in this text together, right?

Maybe sometimes I’m writing into the gaps, and maybe sometimes I’m writing out of them. If I’m writing towards closure, but I never get there, isn’t this why we write? Not to close off, not to close in—an opening: this is what I’m after.

Sometimes I get lost in the text, and sometimes I know exactly where I’m going. Sometimes I know exactly where I’m going, but then I get lost.

Language is a search for more language. To say what we can’t say. So we can say it.

Maybe I’m writing about how my body will never let go, and I don’t want to let go of my body. Maybe I’m writing about trauma, there it is again, I knew it would be here but I didn’t know where. There’s an inside, and an out. Writing is both.

35 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The poet worries she is writing the same poem over and over. No matter what words she puts down, it comes out with a bite. It says I love you with a mouth full of bone.

Trista Mateer, The Dogs I Have Kissed.

#trista mateer#the dogs i have kissed#literature#quote#poetry#love#on love#on writing#writing#on poetry#why we write#from books with love

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a vague impression that a lot of people these days are uncomfortable with the increasing use of the word "consume" in relation to media. Something something capitalism, something something hinging your identity on the things you buy... Certainly when I was trying to come up with a tag for "#reading etc. journal", I was trying to gesture at "media I'm consuming," but "consuming" sounded like such a reductive word.

I think the actual appeal of the word "consume" is that it is a single verb for having a story told to you in any media form. I "read" Dracula Daily, I "watch" Slings & Arrows, I "listen to" WOE.BEGONE, I "play" Myst, and they're all the same activity, not in every sense but in some senses [pun not intended].

And I suppose one potential problem with the word "consume" is that it lumps "reading" a clickbaity article and "watching" a video essay on YouTube in with those other things (not that the things in the latter group are necessarily bad, just that they don't have the same primal importance as fiction, the thing that makes "consume" feel a little bit hollow).

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Han Kang does it again! And I am obliterated every single time.

Of the Han Kang novels I’ve read, this one felt the most hopeful, and also the most personally relevant to me. I think this is because the focus is literary and linguistic: the painful power of words, the impossibility of creating them, the tension between witnessing the world and embodying a self—these central themes are questions and confusions I have also confronted throughout my life. Both characters, therefore, felt relatable in a way that is not the norm for my encounters with Han Kang characters. That being said, both characters are pushed to their emotional extremes through situations I can’t relate to: growing blindness and silence. Yet, the questions that come from these experiences felt familiar (and perhaps there are things in my life and my nature that have led me to a similar set of questions).

As is always the case, I barely know where to start with writing about a Han Kang novel, as the individual threads of the book, and even individual words and phrases, are so powerful and charged as to send my thinking and feelings off into so many different directions. I’m glad, at least, to be writing this sitting at a table in a sunlight-infused cabin, by myself, with a beautiful view of saturated green trees in Bancroft, Ontario. This was a great book to read on my self-designated “writer’s retreat,” as it is so deeply introspective and so centering in the types of concerns I share as a writer and human being.

Early on in my reading, I quickly began a kind of meta-analysis, tracking symbols and relevance to the process of literary creation. Yet, this is something that Han Kang cautions us against, I believe. In the very beginning of the novel, the Greek lecturer describes the symbol of the sword that Borges requested on death’s door be used as his epitaph, and which was taken by critics to be a symbolic key to unpacking Borges’s writing. Yet, the Greek lecturer feels this request to be far more personal, not a key to one’s career and creation, but a key to one’s self: it’s the sword that calves the world from self. Is Han Kang cautioning us in this moment against the appeal of symbolic analysis? Reminding us that sometimes symbols are not charged with literary power, but personal resonance? Sometimes objects just are; they are not symbols at all… We make symbols of our own objects and memories, like we make narratives to understand and articulate ourselves…and that can be dangerous. My instinct to search for and read for symbols is so deep, just as it is to make them of my own life, that I know I cannot resist this process in my reading of this novel. However, I did want to state that I recognize this as an approach, and not, inherently, the right or best one through which to read books and to read one’s own life. I think Han Kang might struggle with a similar tension…how are we both embracing this understanding of language (isn’t language inherently symbolic?) and rejecting it? Like our silent protagonist student, the terror of words quickly overwhelms as we start to confront the inherent contradictions in speaking or writing at all…

This caveat being given (weak, weak), I jump into my analysis. Does the original impulse of this novel come out of writer’s block for the author? It’s terrifying to reach inside and find no words. It’s terrifying to spit out words, to force them out. It’s terrifying to look at each word and find it to be so deeply insufficient for the complex concept/emotion it is supposed incapsulate. It’s terrifying to try honestly and still be misunderstood. It’s terrifying to realize the harmful power of words, where even a small mistake can cause devastation…and what would happens if you tried to harness that harm into language? Irreversible. What is the response but to retreat into silence?

Yet, in the face of this crisis of language, there is true fascination with language and words. The descriptions of tenses in Greek unlock layers of articulation, the parting of roads under sheets of ice. The way Greek’s “middle voice” operates, referring to the self, reflexive, inspires a meditation on impact and change. Just so, the concepts in words become the concepts in our selves, or the reverse. To change something is to change the self, the Greek lecturer reflects, and he applies this to love/foolishness (recalling his first love that went south when he spoke a question he should not have asked). Love/foolishness: two sides of the same coin in which his foolishness destroys love and love destroys his foolishness (himself). The student (neither protagonist is ever given a name—perhaps names are too personal, too specific and insufficient) feels a similar fascination with the structure and nature of language, as it was a singular new word, bibliothèque, that drew her out of her silence as a teenager, that gave her words again. She pays attention to grammar, to language itself, to the act of translation. Both the Greek lecturer and the student have this in common, although the Greek lecturer longs more for literature, for narrative, for world (as it fades from his eyes, as it is relegated to dreams and memories). The student exists in a more immediate and practical sphere, experiencing the necessity of language itself.

This difference in desire is reflected in the narrative structures of the interwoven stories of both protagonists. The Greek lecturer’s sections take a direct “you” address to different figures in his life: his first love, his sister, his best friend in college. Each of these letters (missives, unsent) captures an array of memories and a portrait of deep love, which sustained and drove him. Each is also infused with tragedy and loss—the break-up with his first love after he asked her to speak, using the experiences she had at speech therapy as a young deaf child; the distance from his sister after he moved back to South Korea from Germany; the death of his college friend at age thirty-eight—and in unfolding each confessional, it is clear how much the Greek lecturer wants to say to each of these people. Some is shared, much is left unsaid. His is a different kind of silence.

The portrait of sibling-hood in the section addressed to the sister moved me deeply, both in its portrait of connection and in its individual lines: “it was in the company of your scowling, crying, laughing face that my childhood cracked, broke, was put back together unharmed, and so passed” (pg. 73). These siblings understand each other deeply, beyond language, having passed through their alienation in “togetherness.” This section—and the description of the shock of the father’s loss of eyesight, the Greek lecturer’s dread of his future—made me remember something I don’t think about often (I think I blocked it from my mind) that happened maybe seven or eight years ago. My younger sister had a disturbing eye doctor appointment and, for a brief time, we all thought she was going to go blind. During the two or three weeks until her follow-up, she wore dark sunglasses every time we went outside. I recall the devastation of this news—it was a kind of tragedy I would have never seen (ah) coming. I thought a lot at the time about how my sister was so fundamentally someone who saw the world; I thought about her life-long love of colors, visual art, drawing and painting, and her field work as a scientist in which she excelled at identifying plants, particularly grasses with nuances in green that no one else could see. She lived with, honed, and internalized an advanced ability to see and transmute her seeing—through details, lines, colors, and shapes—into both art and science. Seeing was part of her identity. Who would she be without this? The happy ending of this story is my sister had only a fleeting condition and the first optometrist she visited was overly dire. Her eyes recovered fully. It feels impossible to imagine the inverse narrative, and yet I did for a brief window of time.

While the Greek lecturer’s story hinges on introspective accounts of memories, the story of the student is revealed to us in little practical bursts: she has recently lost her mother (to cancer) and her son (in a legal battle with her ex-husband). She experienced a similar silence as a teenager, so that when she cannot force out the next word as she lectures at the blackboard her first thought is, it’s happening again. Throughout the book—until the very end—she is silent, and her sections are written in third-person, as if experiencing her life externally. Her words that we do hear, that she says “from a deeper place than throat and tongue,” are italicized and few. When she begins to communicate with the Greek lecturer by writing on his palm, her words are focused on practicalities, caring for him and helping him. This practicality feels both part of her nature and a part of the minimalist relationship she has developed with words. Words are, for her, so deeply buried that she can’t speak even to say her child’s name. She can’t speak in order to stand up for her son when he tells her he’s going away for a year, as his father has planned. In this moment, the language she wishes to use on her ex-husband is violent, angry. Which thing, I wondered, between silence and fury is powerlessness? In silence, we cannot defend ourselves. In anger, the words take over us and, bursting into the world, cut in ways that are terrible and unforeseen and final. We’re at the mercy of words. I wondered whether her silence (a removal of language) was an attempt to buffer herself from feeling? If we cannot put voice to feelings, does silence destroy feelings, just as feelings destroy silence (another set of reflexive inverses, interlocked, and self-impacting)? She dreams, in horror, of a singular word that contains all language. This is not a promising possibility, but a kind of nuclear bomb of language, with the power for infinite destruction if unleashed. This is the thinking of someone who understands how powerful and central language inherently is to ourselves.

When her therapist attributes her silence to the recent losses in her life, the student says, “it’s more than that” about her silence, but throughout the novel the losses of her child and her mother seem so acute. Later, the memory of the violent words her husband said to her—labeling her as insane, a “crazy bitch,” and ill-fit to care for her child—are recalled. She doesn’t want to remember this and she doesn’t want to feel the emotions of that memory. She also recalls the violence with which she wanted to respond in that moment, and the words cutting her up inside before they ever had a chance to get out. This memory may be the heart of her silence, yet, it is, as she herself shared, so much more complex than any one moment: an all-encompassing realization of the terrible nature of language.

While the unfamiliar and awe-inspiring grammar and structure of the Greek language is what the student seeks as a cure to her silence, time is also given in this book to the content of the writings of Plato and the philosophy of Socrates. These two thinkers form a compelling backdrop for this book, and the Greek lecturer views them as key thinkers that he circles around and around, facing his impending darkness. The Greek lecturer demonstrates the nearly identical verbs in Greek: to suffer and to learn. In pointing out their visual and aural proximity, the Greek lecturer points out how Socrates brings these words together, asking us to see the similarities in their actions. This was one of many moments in the first part of this book that reminded me of BTS (thinking here of RM’s word play with live/love in Trivia: Love). This was the point at which I realized this wasn’t a new Han Kang book—just a new translation—and she actually wrote this back in 2011. So, I came to conclusion that I just see BTS in it (the organizing narrative/symbolism of my brain), although perhaps RM has read this book. I found it interesting to consider Socrates’s famous reframe and philosophical position, “I know nothing,” as the basis for this book…beginning from a state of “knowing nothing” is an approach that takes the teeth out of words and language, by positioning oneself as not an authority or cause, but as a recipient or effect. Yet, I think Plato was the more central philosopher for the Greek lecturer. His longing for the “Forms” of things, of Beauty, which can only be understood cognitively and not seen in this world seems like a poignant obsession for the thoughts of a man on the brink of blindness. And the Greek lecturer is, like my sister, a man so in love with sight, with seeing, with imagery, with the visuals of the world: his memory of the beauty of the Buddha’s Birthday night, when he sat underneath the strings of lanterns with his mother and sister, and which he tries to revisit years later, is his most formative early memory.

During the Buddha’s birthday scene, I reflected on my life-long impulse to write. I think I have encountered writing as a response to the kind of desperation brought on by the sublime that the Greek lecturer experiences in this scene. What are we to do with those transcendent moments that haunt and transform us? That seem beyond our ability to contain inside ourselves? That will drive us to insanity, we fear, if we just hold them inside. I’ve tried to write that feeling out of myself. I’ve tried to transmute that experience I had into words. I have treated my writing as alchemy. I have tried to state change the memory moment into language. I have tried to reach across the “separateness of persons” and will that memory moment into you, or at least summon up your parallel moment with identical feelings. There is a similar self-intrinsic need to speak for Plato who the novel describes once as “know[ing] this is a dangerous soliloquy, that he is, in fact, answering his own question, as do we who are reading” (pg. 85). Writing feels like trying get into some impossible space, to leap and hope you find the parachute on the way down. For the Greek lecturer, like for Plato, words remain the impulse, as what else can he use to search for answers in the face of gigantic questions? For the student, words are smothered by the questions, by the horror of the answers. Both understandings of language can coexist.

The student remembers a kaleidoscope she made in school as a child, and she uses this memory to explain the way the worlds appears to her—“fragmented, each piece distinct and separate” (pg. 91)—once she loses words. I began to treat the kaleidoscope as the symbolic key to this text, operating like the scholar of Borges who I mentioned above. Han Kang writes, “The shards of memories shift and form patterns. Without particular context, without overall perspective or meaning. They scatter; suddenly, decisively, they come together” (pg. 92). Yet, borrowing the Greek lecturer’s interpretation of Borges’s epitaph as deeply personal, I strove to see the kaleidoscope symbol operating on a personal level in addition to a literary one. As the Greek lecturer writes to his loved ones, and accumulates their memories by jumping around in space and time, the structure of the writing mirrors the fragmentation of a kaleidoscope, making a point of the structure of memories contained within a singular being. Yet, isn’t it the very self, too, that is in fractals? Fascinatingly, as the Greek lecturer and the student arrive at his home and he begins to tell her the stories of his life, her memories, too, start to interweave and intersperse, again like the fracturing effect of a kaleidoscope.

While the first half of the novel assembles the characters and their situations, like a reverse kaleidoscope effect of bringing the pieces together, it is the sprint to the finish—after the bird incident, when our two protagonists come together—that is so powerful. I had to read the second half of this novel in one sitting because the momentum builds, like two magnets drawn closer and closer together, invisibly and forcefully. As one being, our two protagonists navigate the world together, pairing an outpouring of words with close observation, pairing dream-like intensity with practical reality. In this scene, they remind me of a poem by Mary Szybist called The Cathars Etc.:

The Cathars Etc.

By Mary Szybist

loved the spirit most

so to remind them of the ways of the flesh,

those of the old god

took one hundred prisoners and cut off

each nose

each pair of lips

and scooped out each eye

until just one eye on one man was left

to lead them home.

People did that, I say to myself,

a human hand lopping at a man's nose

over and over with a dull blade

that could not then slice

the lips clean

but like an old can opener, pushed

into skin, sawed

the soft edges, working each lip

slowly off as

both men heavily, intimately

breathed.

My brave believer, in my private re-enactments,

you are one of them.

I pick up in the aftermath where you're being led

by rope

by the one with the one good eye.

I'm one of the women at the edge of the hill

watching you stagger magnificently,

unsteadily back.

All your faces are tender with holes

starting to darken and scab

and I don't understand how you could

believe in anything that much

that is not me.

The man with the eye pulls you

forward. You're in the square now.

The women are hysterical,

the men are making terrible sounds

from unclosable mouths.

And I don't know if I can do it, if I can touch

a lipless face that might

lean down, instinctively,

to try to kiss me.

White rays are falling through the clouds.

You are holding that imbecile rope.

You are waiting to be claimed.

What do I love more than this

image of myself?

There I am in the square walking toward you

calling you out by name.

Poetry is the right place to go during this unspooling of the novel, during this near-magical coming together of the protagonists into one strange, incredible, better being. The interspersing or memories and dreams becomes stranger…the student leaves, and the lecturer’s memories become dreams. She returns and the descriptions grow even more fragmented, like poetry in their structure— solitary words in a line down the page. Is this spaced-out writing mirroring what the lecturer’s eyesight has become—fragmented, seeking space for clarity—like the concept of writing in the dark that the novel describes, handwriting with cautious extra space, so that no lines overlap, so that each word can be understood? The logic of this novel, whether kaleidoscope or sword, linguistic or literary, is inherently deeply poetic, I feel.

The novel’s ending is stunning as the protagonists progress into a hopeful interwoven state, described like rising to the surface of a lake. And, on the final page, we resolve with a section labeled 0 and, for the first time, narration is included in the first person point of view of the student. Language seems to bubble up in her in this final moment, in a reclamation of herself, but the book ends and we are left to interpret, to reach our own conclusions, in silence. It’s a powerful ending that feels less literal than gestural and emotional. I think there is so much I could get out of this book from re-reading it, from reading it in reverse, from reading it out of order. It raises more questions than it supplies answers, but it does demonstrate a central enduring faith in human connection, which both relies on and rejects language in order to be born, to bloom.

#greek lessons#han kang#important reading#why we write#reflections on human connections and intimacy#the world and the self#powerful books#reading reflection#south korean literature

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“No, you already have the information, all the names and dates are inside your head. What you want, what you’re really after, is a story.” --(V for Vendetta)

I think about this a lot, especially in juxtaposition with Carl Sagan pointing out that it’s not the molecules, it’s how they’re arranged.

I also think a lot about a typo I make regularly. I type “destory” for “destroy”.

To de-story something (or someone) is to destroy it (or them).

What is an artifact without a story? Pull it from the ground, where it’s rested for thousands of years. What’s the first thing you ask?

“What is this? How was it used?”

What you’re really asking is, “What did this mean?”

Human beings want stories. We make sense of the world through them. We tell each other and ourselves stories to figure out the bewildering flood of sensation, chance, consequence, and other stuff we’re subject to not only while we’re awake, but while we dream.

Without the story, we don’t know if it was a bedpan or a fine dining dish. Was it a doll or a ritual figurine? Who the hell used this thing, and why?

And I also think about Victor Frankl. How a person can survive horrible things with some hope of remaining intact, by finding some meaning in them.

A story. Because that’s what it is—meaning. An arrangement of meaning.

Stephen King called being a historian “sitting close to the engine-seat of God’s creation.” (Michael Hanlon, in IT.)

What is a historian but someone who knows the story? Who can guess at the meaning, however imperfectly, and explain it to the curious?

And then I think of a Wheel of Time line. “Nothing’s more dangerous than a man who knows the past.” (Thom Merrilin.)

To de-story is to destroy. Stories are powerful whether or not they’re objectively true. To tell a story is to create meaning, to remake the world.

This is why fascists want to privatize education, so that only certain people have access to historical information and context. This is why Fox News is powerful—because it tells the stories of grievance its viewers use to arrange their world into hateful patterns.

The stories you tell yourself matter. The meaning you find in the world matters. Knowing whether the thing you just dug up out of the ground was a bedpan or a royal salver matters.

Because here’s the thing about stories: You, as a human being, can tell any goddamn story you like. You have that cosmic power. It came preinstalled. You can’t help it; that shit is hardwired in.

The stories your family tells about ancestors. The stories you tell your friends about your childhood. The stories your friends tell you about the time you guys went and did something, do you remember?

The stories about gods, about heroines, about ancient rulers and Ea-nasir the copper merchant, the stories about wars and eruptions.

Stories matter. Who tells them and how they are told matter.

You possess this power just by virtue of being alive and human. The great advantage of the internet is that no matter how alien you feel, someone out there will “get” your story. Someone will say, “oh hey, me too” on a forum post and all of a sudden…

…you are no longer alone.

There’s a story. There is meaning.

To de-story is to destroy. Some Egyptian king chips all mention of predecessors off stelae. A city is razed, survivors slaughtered. Famines are created by ruling classes. Survivors’ testimony is buried. Fascists scream about “CRT” to elide the truth people live with daily.

See? Destruction.

You have facts and figures, names and dates. You have artifacts, and you have feelings.

What you want, what you’re really after, my friends, is a story.

Go.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a girl of fear, a woman of anger— look how we've grown

girls contain multitudes, heather o'neill / king, florence + the machine / The Affront (L'affronto), by Antonio Piatti / In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado / this pin / cassandra, florence + the machine / What If This Were Enough?: Essays by Heather Havrilesky) / crush, richard siken / the closest thing i could find was this soundcloud link / a womans beauty, susan sontag / a vision of fiammetta, dante gabriel rossetti / stop me, natalia kills / fury, yevgeny yevtushenko

everyone say god bless you to @pe4rl-diver for the sources

#and they ask why we need feminism#feminism#gender inequality#poetry#quotes#spilled ink#poems and quotes#spilled poetry#words#webweaving#webweave#aesthetic#poems and poetry#writing#poem#spilled thoughts#web weaving#*mine: graphics

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

'The Human Being Appears' - Abdulrazak Gurnah on the Pleasure and Importance of Writing

Abdulrazak Gurnah's rousing 2021 Nobel Prize acceptance speech raises the fundamental question of why we write.

“I believe that writing has to show what can be otherwise.”– Abdulrazak GurnahTweet

In this rousing acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature awarded to him in 2021, Tanzanian-born British writer Abdulrazak Gurnah describes how his writing evolved from a classroom exercise to an activity that enabled him to make sense of his own alienation and poverty as an immigrant, as well as the…

View On WordPress

#fiction#Immigration#Literature#Nobel Prize#Postcolonial Writing#race#Racism#Revolution#Tanzania#trauma#Turmoil#Why we Write#Writing#Zanzibar

0 notes

Text

i love when words fit right. seize was always supposed to be that word, and so was jester. tuesday isn't quite right but thursday should be thursday, that's a good word for it. daisy has the perfect shape to it, almost like you're laughing when you say it; and tulip is correct most of the time. while keynote is fun to say, it's super wrong - i think they have to change the label for that one. but fox is spot-on.

most words are just, like, good enough, even if what they are describing is lovely. the night sky is a fine term for it but it isn't perfect the way november is the correct term for that month.

it's not just in english because in spanish the phrase eso si que es is correct, it should be that. sometimes other languages are also better than the english words, like how blue is sloped too far downwards but azul is perfect and hangs in the air like glitter. while butterfly is sweet, i think probably papillion is more correct, although for some butterflies féileacán is much better. year is fine but bliain is better. sometimes multiple languages got it right though, like how jueves and Πέμπτη are also the right names for thursday. maybe we as a species are just really good at naming thursdays.

and if we were really bored and had a moment and a picnic to split we could all sit down for a moment and sort out all the words that exist and find all the perfect words in every language. i would show you that while i like the word tree (it makes you smile to say it), i think arbor is correct. you could teach me from your language what words fit the right way, and that would be very exciting (exciting is not correct, it's just fine).

i think probably this is what was happening at the tower of babel, before the languages all got shifted across the world and smudged by the hand of god. by the way, hand isn't quite right, but i do like that the word god is only 3 letters, and that it is shaped like it is reflecting into itself, and that it kind of makes your mouth move into an echoing chapel when you cluck it. but the word god could also fit really well with a coathanger, and i can't explain that. i think donut has (weirdly) the same shape as a toothbrush, but we really got bagel right and i am really grateful for that.

grateful is close, but not like thunder. hopefully one day i am going to figure out how to shape the way i love my friends into a little ceramic (ceramic is very good, almost perfect) pot and when they hold it they can feel the weight of my care for them. they can put a plant in there. maybe a daisy.

#warm up#writeblr.#i am not going to personally comment on the pineapple debate#some things are too big for me.#maybe we could have everything on earth choose their own names.#wouldn't that be fun#it is a creative writing exercise. okay. ily#''why only these languages?'' ..... bc i dont know every language#sorry :(#PLEASE leave me comments about what words u think are correct. i love learning them#btw! this isn't saying these are the most BEAUTIFUL words for it... just the words that are the most CORRECT#like i quite like the word ''keynote'' as mentioned. it's got a lot of fun sounds in it.#but it is not CORRECT.#''gloaming''' is interesting and fun and poetic but it is NOT correct . evening is MORE correct#but less beautiful.#does that make sense?

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

SO IVE BEEN GOIN INSANE SINCE THIS TRAILER DROPPED. JUST. SIMON. SIMON. SIMON.

#simon petrikov#fionna and cake#adventure time#goin insane over him#thers no words to describe how im feelin#i wish i could draw somehtin better but i am goin INSANE#FINALLY. AFTER ALL THESE YEARS. we are being FED.#ALSO?? HOW THEY SHOWED HIM EXACTLY WHEN THE LYRICS GO ''WHATS WRONG WITH ME'. LIKE HELLO???????#ive seen so many good theories PLEASE GOD WRITE FICS I AM BEGGIN I LL DRAW U FANART BLS HEL P#IDK WOT IM GONNA DO FOR A WHOLE MONTH#SOMEONE KNOCK ME OUT TIL THE 31ST. HIBERNATE ME. HELP.#also i need to put it out there the first thing i thought when i saw this trailer was simon is tryina rewrite fionna and cake#which is why their world keeps changin so much? idk idk#ive seen so many different ideas and they are all so good please help#ALSO GOD. THIS MAN IS JUST GOIN THRU IT. AND ITS ONLY BEEN A QUICK TRAILER.#im sorry for so many tags idk where to put these help#maybe i should make an actual blog for like. whatever. n reblogs. help.

10K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I wanted to let you know that I love you and that you are one of the kindest and nicest people in fandom imo.

I wanted to ask you what you think of self inserts in fic? Being it a canon character or a oc's doesn't matter.

awww, thank you lovely anon ❤️

ooh what do you mean by self insert? i’m going to assume you mean projecting onto a character rather than x reader fic, which is my understanding of self insert and neither a canon character nor an OC!

but — projecting onto a character — heck yeah. i feel like that makes for some of the most meaningful fic, especially if you can do it consciously (or, like, semi-consciously, if consciously is too painful 😂). there are all sorts of reasons why people might want to write fic, but if you’re not doing some exploration and projection onto your characters — little bit of a missed opportunity there, imo!

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I am writing because they told me to never start a sentence with because. But I wasn't trying to make a sentence—I was trying to break free. Because freedom, I am told, is nothing but the distance between the hunter and the prey.

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.

#on earth we're briefly gorgeous#literature#quote#journal#diary#autobiography#writing#freedom#free#why we write#from books with love#on writing#life#life quote#ocean vuong

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the comments thread for What Happens Next:

-Lots of thoughtful analysis;

-Someone misgendering Milo and then another commenter explaining that at least a few TERFs have gotten into WHN and see it as "the trans community finally becoming aware of their own narcissism" or something like that;

-A long and otherwise nuanced comment helpfully explaining that Gage is an example of what happens when the "proshipper" mindset is taken too far;

-At least one person defending Milo's father.

Someday I would love to be able to write something that is just as unapologetic about showing a bunch of fucked-up people and not telling you what to think about them as WHN is. But comments like that are a reminder of why I'm afraid to do it.

I mean... I don't think fiction is obligated to try to sell people on a particular worldview, but that is one thing it can do, and maybe I am better suited to writing stories that attempt to nudge readers in a particular direction. But I want to be, like, nuanced and non-dogmatic and most of all truthful about it. And the more accurately I depict an abuser, the more people there are going to be in the world who are exactly like that abuser and are going to read my story and say, "Wow, [abuser] is the only person in this story with any sense." And I have to live with that.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

remember when miraculous ladybug finally decided to do an "adrien hangs out with The Guys" episode, like how we get scenes of marinette hanging out with The Girls all the time, but i guess the writers decided that the only way adrien would fit in an environment with a bunch of guys was if they were in a gay night club, and the night club was adrien's bedroom, and they were throwing around rainbow glitter and kissing each other and blasting The Village People so loud that it almost killed his already dead mother and

#everyone come get your bi-weekly ''buggachat thinks about Party Crasher'' post#''there is no canon evidence that adrien is LGBTQ'' yeah well try to explain the existence of party crasher to me#like why else would they write it like this#nino: hey dude let's throw a party at your house. GUYS ONLY!!!!#adrien: i dont understand the gender distinction but can we blast The Village People? on my special edition rainbow record w rainbw glitter#adrien: and can nathaniel and marc kiss me?#nino (nodding along): yes. of course.

6K notes

·

View notes