#in no small part because I was relying more on my own historical knowledge than usual so I had to double check myself constantly

Text

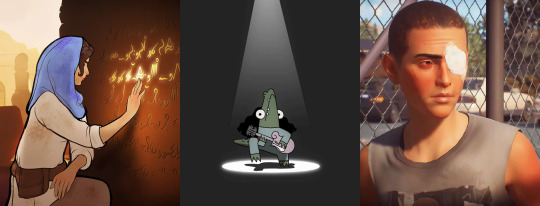

Historical Analysis: class and injustice in 'The Ressurrectionists' minisode

Alternate title: why we're tempted to be upset with Aziraphale and why that's only halfway fair

Okay so first off huge thanks to @makewayforbigcrossducks for asking the question (and follow-up questions lol) that brought me to put these thoughts all together into a little history nerd ramble. That question being, Why is Aziraphale so clueless? Obviously, from a plot perspective, we know we need to learn some lessons about human moral dilemmas and injustices. But from a character perspective? A lot of this minisode is about Aziraphale being forced to confront the flaws of heavenly logic. This whole idea that "poverty is ineffable" basically boils down to 'yeah some people are poor, but their souls can be saved just as if not more easily that way, so it's not our problem and they probably deserve it anyway for not working hard enough,' a perspective that persists in many modern religious circles. Aziraphale isn't looking at the human factor here, he's pretty much purely concerned about the dichotomy of good and wicked human behavior and the spiritual consequences thereof, because that's what he's been told to believe. His whole goal is to "show her the error of her ways." He believes, quite wholeheartedly, that he's helping her in the long run.

"the lower you start, the more opportunities you have"

So here's what we're asking ourselves: Why did it take him so bloody long to realize how stupid that is? Sure, he's willing to excuse all kinds of things in the name of ineffability, but if someone in the year of our lord 2023 told me he was just now realizing that homelessness was bad after experiencing the past two centuries, I'd be resisting the urge to get violent even if he WAS played by Michael Sheen.

Historical context: a new type of poverty

Prior to the 19th century (1800s), poverty was a very different animal from what we deal with now. The lowest classes went through a dynamic change leading up to the industrial revolution, with proto-industrialization already moving people into more manufacture-focused tasks and rapid urbanization as a result of increasingly unlivable conditions for rural peasantry. The enclosure of common lands and tennancies by wealthy landowners for the more profitable sheep raising displaced lots of families, and in combination with poor harvests and rising rents, many people were driven to cities to seek out new ways of eeking out a living.

Before this, your ability to eat largely would have depended on the harvest in your local area. This can, for our purposes, be read as: you're really only a miracle away from being able to survive the winter. Juxtapose this, then, with the relatively new conundrum of an unhoused urban poor population. Now if you want to eat, you need money itself, no exceptions, unless you want to steal food. Charity at the time was often just as much harm as good, nearly always tied deeply up in religious attitudes and a stronger desire to proselytize than improve quality of lie. As a young woman, finding work in a city is going to be incredibly difficult, especially if you're not clean and proper enough to present as a housemaid or other service laborer. As such, Elspeth turns to body snatching to try to make a better life for herself and Wee Morag. She's out of options and she knows it.

You know who doesn't know that? Aziraphale.

The rise of capitalism

The biggest piece of the puzzle which Aziraphale is missing here is that he hasn't quite caught onto the concept of capitalism yet. To him, human professions are just silly little tasks, and she should be able to support herself if she just tried. Bookselling, weaving, farming, these are all just things humans do, in his mind. He suggests these things as options because it hasn't occurred to him yet that Elspeth is doing this out of desperation, but he also just doesn't grasp the concept of capital. Crowley does, he thinks it's hilarious, but Aziraphale is just confused as to why these occupations aren't genuine options. Farming in particular, as briefly touched on above, was formerly carried out largely on common land, tennancies, or on family plots, and land-as-capital is an emerging concept in this period of time (previously, landowners acted more like local lords than modern landlords). Aziraphale just isn't picking up on the fact that money itself is the root issue.

Even when he realizes that he fucked up by soup-ifying the corpse, he doesn't offer to give them money but rather to help dig up another body. He still isn't processing the systemic issues at play (poverty) merely what's been immediately presented to him (corpses), and this is, from my perspective, half a result of his tunnel-vision on morality and half of his inability to process this new mode of human suffering.

Half a conclusion and other thoughts

So we bring ourselves back around to the question of Aziraphale's cluelessness. Aziraphale is, as an individual, consistently behind on the times. He likes doing things a certain way and rarely changes his methodology unless someone forces his hand. Even with the best intentions, his ability to help in this minisode is hindered by two points: 1)his continued adherance to heavenly dogma 2)his inability to process the changing nature of human society. His strongest desire at any point is to ensure that good is carried out, an objective good as defined by heavenly values, and while I think it's one of his biggest character hangups, I also can't totally blame him for clinging to the only identity given to him or for worrying about something that is, as an ethereal being, a very real concern. Unfortunately, he also lacks an understanding of the actual human needs that present themselves. Where Elspeth knows that what she needs is money, Aziraphale doesn't seem to process that money is the only solution to the immediate problem. This is in part probably because a century prior the needs of the poor were much simpler, and thus miraculous assistance would never have interfered with 'the virtues of poverty'. (You can make someone's crops grow, and they'll eat well, but giving someone money actually changes their economic status.) Thus, his actions in this episode illustrate the intersection of heavenly guidelines with a weak understanding of modern structures.

This especially makes sense with his response to being told to give her money. Our angel is many things, but I would never peg him as having any attachment to his money. He's not hesitant because he doesn't want to part with it, he's hesitant because he's still scared it's the wrong thing to do in this scenario. He really is trying to be good and helpful. So yes, we're justifiably pretty miffed to see him so blatantly unaware and damaging. He definitely holds a lot of responsibility for the genuine tragedy of this minisode, and I think Crowley pointing out that it's 'different when you knew them' is an extremely important moment for Aziraphale's relationship with humanity. Up until now, he's done a pretty good job insulating himself from the capacity of humans for nastiness, his seeming naivity at the Bastille being case in point.

In the end, I think Aziraphale's role in this minisode is incredibly complex, especially within its historical context. He's obstinate and clueless but also deeply concerned with spiritual wellbeing (which is, to Aziraphale, simply wellbeing) and doing the right thing to be helpful. While it's easy to allow tiny Crowley (my beloved) to eclipse the tragic nature and moral complexity of this minisode, I think in the end it's just as important to long-term character development as 'A Companion to Owls'. We saw him make the right choice with Job's children, and now we see him make the wrong choice. And that's a thing people do sometimes, a thing humans do.

~~~

also tagging @ineffabildaddy, @kimberellaroo, and @raining-stars-somewhere-else whose comments on the original post were invaluable in helping me organize my thoughts and feelings about this topic. They also provided great insight that, in my opinion, is worth going and reading for yourself, even if it didn't factor into my final analysis/judgement.

If I missed anything or you have additional thoughts, please please share!!! <3

#this was a monster of a post to write#in no small part because I was relying more on my own historical knowledge than usual so I had to double check myself constantly#but I had a lot of fun and I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did#good omens#good omens 2#neil gaiman#good omens analysis#good omens meta#the resurrectionists#good omens season 2#good omens minisode#nerd shit#ineffable husbands#aziraphale good omens

560 notes

·

View notes

Text

Divination Basics

From the Roman priest reading auguries to interpret the will of the gods to the modern fortune teller reading with a deck of playing cards, divination has been a part of human spirituality for thousands of years. Today, divination is an important part of many witches’ practices, and can be an important tool for self-reflection and analysis.

Merriam-Webster defines divination as, “the art or practice that seeks to foresee or foretell future events or discover hidden knowledge usually by the interpretation of omens or by the aid of supernatural powers.” Divination can be used for many things, not just to predict the future. It can be used to understand the past, identify patterns at work in your present, or as a tool for working through trauma.

In the book You Are Magical, author Tess Whitehurst describes divination as, “a way of bypassing your linear, thinking mind and accessing the current of divine wisdom and your own inner knowing.” As I’ve discussed in a previous post, all of us are receiving psychic information all the time, though many of us don’t realize it. Divination tools like tarot cards or rune stones act as triggers to help kickstart our natural psychic gifts.

Divination relies on the use of our intuition. Intuition is defined my Merriam-Webster as, “the power or faculty of attaining to direct knowledge or cognition without evident rational thought and inference.” These are the things you know without needing to be told. Another way of thinking of it is this: your intuition is the way you interpret the information you receive through your psychic senses.

The most important thing to remember when doing divination is that the tool you are using isn’t giving you information — it’s simply helping you to access information you already know. The revelations come from you, not from the cards or whatever other tool you may be using.

When using divination to foresee the future, it’s important to remember that the future is never set in stone. These tools can only show you the most likely outcome based on your current direction.

Beginner-Friendly Divination Tools

These are the divination methods I would recommend for beginners. For one thing, most of these systems are fairly easy to learn and use. For another, these are some of the most popular divination methods among modern witches, so it’s easy to find information about them and/or talk to other practitioners about their experience.

As you’ll see, each divination method has its own strengths and weaknesses, so you may choose to learn several methods that you can combine to get stronger readings. Or you may find that you can get all the information you need from a single method, which is also okay.

Tarot. This is my personal favorite divination method, but it’s also the one with the most misconceptions surrounding it. Tarot cards do not open a portal to the spirit world, and they probably didn’t originate in Ancient Egypt. In fact, evidence suggests that the tarot comes from a medieval Italian card game called Tarocchi, although the modern tarot deck as we know it didn’t come around until the 20th century. Tarot cards are not any more or less supernatural than ordinary playing cards. (Which, incidentally, can also be used for divination.)

Tarot makes use of archetypes, and many readers interpret the cards as a map of an archetypal spiritual journey. For this reason, tarot cards are especially useful for identifying the underlying patterns and hidden influences in any given situation.

Most tarot decks follow the same set of basic symbolism. Unfortunately, this does mean that new readers will need to study the accepted meanings. This isn’t to say that your readings will always match up 100% with the standard meanings of the cards — you may receive intuitive messages that deviate from tradition. Still, it’s helpful to know a little of the history and traditional symbolism behind this powerful divination tool. The good news is that, since most decks use similar symbolism, once you learn the traditional meanings you can successfully read with almost any tarot deck.

I’m planning to post a more in-depth introduction to tarot very soon, but in the meantime, if you want to learn this divination method I recommend starting with the book Tarot For Beginners by Lisa Chamberlain and/or with the website Biddy Tarot.

Oracle Cards. Oracle cards have been rapidly gaining popularity in the witchcraft and New Age communities in the last few years, and it’s easy to see why. One major appeal of oracle cards is how diverse they are — there are countless different oracle decks out there, each with its own theme and symbolism. Another big plus is how beginner-friendly they are; Oracle cards are usually read intuitively, so most decks won’t require you to learn a complex system of symbolism. (Of course, the fact that every oracle deck uses different symbolism can be frustrating for some readers, because they have to learn a new set of symbols for every deck.)

Some readers (myself included) also find that oracle cards usually give more surface level information. Tess Whitehurst says that, “While oracle cards can help us answer the questions ‘What direction should I take?’ and ‘What is the lesson here?’ tarot cards are more suited to helping us answer the questions ‘What is going on?’ and ‘What is the underlying pattern at work here?'” For this reason, many readers choose to use tarot and oracle cards together to get a more well-rounded look at the situation.

Another common complaint about oracle cards is that many decks are overwhelmingly positive and shy away from dark themes or imagery, which creates an imbalanced reading experience. I think this is best summed up by one Amazon review for the Work Your Light Oracle, which says: “Basically, this is very much a deck for Nice White Ladies(TM) who like crystals and candles but aren’t ‘super into all that witchy stuff.'”

There ARE oracle decks out there that address darker themes, but many of the most popular decks on the market are overwhelmingly positive. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Sometimes a little positive encouragement is more helpful than brutal honesty. However, too much focus on the positive can lead you to ignore your problems, which only makes things worse in the long run. For this reason, finding balanced decks is important — if you’re going to use a very shiny happy deck, my advice would be to alternate it with more grounded decks, or with a deck specifically designed for shadow work.

That being said, oracle cards are a great divination tool if you can find a good deck, especially for beginners who are intimidated by more structured systems like tarot and the runes. If you’re interested in working with oracle cards, the best way to start is to find a deck that 1.) you feel a strong attraction to, and 2.) has a good guidebook. (My favorite oracle deck is the Halloween Oracle by Stacey Demarco, which I use for readings all year.)

Runes. The Elder Futhark alphabet is a runic alphabet that originated in ancient Scandinavia around 200 AD. While this was an actual writing system, it also had magical and mythological associations in the cultures that originally used it. While using the runes for divination is a modern practice, it is based on the historical sense of magic surrounding these symbols.

Like tarot, the runes have a traditional set of meanings. However, because there are only twenty-four runes, there aren’t as many meanings to learn as there are with tarot. Some rune sets also contain a blank stone, which has its own special meaning. I have personally found the runes to be a great source of wisdom and insight, although they do tend towards “big picture” messages rather than small details.

However, there is one major stain on the runes’ history; they were studied and used by Nazi occultists before and during World War II. Like many symbols associated with historical Germanic paganism, the runes were appropriated as part of Nazi propaganda — for example, the Sowilo rune was incorporated into the SS logo. This isn’t to say that you can’t reclaim the Elder Futhark alphabet, but I do think it’s important to know the history going in. Because of their association with Nazism, it’s best to avoid wearing or publicly displaying the runes.

There are other ancient alphabets that are used for divination, like the Anglo-Saxon runes or the Irish Ogham, but the Elder Futhark is the most popular.

If you’re interested in learning divination with runes, I recommend the book Pagan Portals: Runes by Kylie Holmes.

Pendulums. Pendulums are interesting because, unlike tarot, oracle cards, and runes, they can be used to answer yes or no questions. For this reason, many readers use pendulums to get clarification on readings they’ve done with other divination methods, but you can also use pendulums on their own.

A pendulum is any small, weighted object hanging from a chain or string. You can buy a pendulum made specifically for divination from a metaphysical shop or an Etsy seller, but you can just as easily use something you already have: a necklace, your housekey, or a small rock or crystal tied to a string.

Pendulums may be the easiest divination method to learn. The only thing you need to do to learn how to interpret a pendulum is ask it what its “yes” and “no” motions look like. To do this, simply hold your pendulum in your hands and focus on your connection to it. Then, let the pendulum hang from its chain or string so it can swing freely. Say or think, “Show me ‘yes’.” Allow the pendulum to swing, and pay attention to its movements. “Yes” is often a forwards-and-backwards swing or a clockwise circle, but your “yes” may look different. (Some witches even notice that different pendulums in their collection have different “yes” and “no” movements!) Once you’ve gotten the pendulum to show you its “yes,” ask it to show you its “no.” For many readers, “no” is a side-to-side swing or a counterclockwise circle, but again, yours may be different.

The biggest downside to pendulums is that because they typically only answer “yes” or “no,” you have to be very specific with your questions. Pendulums aren’t the best tool for general energy readings or open-ended advice. However, that specificity makes them great for validating your gut feelings, interpreting your dreams, identifying a deity or spirit that you think may be reaching out to you, or any other situation that requires a little clarification.

#baby witch bootcamp#long post#baby witch#witch#witchcraft#witchblr#divination#divination witch#tarot#tarot cards#tarot meme#oracle cards#runes#runestones#elder futhark#pendulum#fortune teller#psychic#intuition#intuitive#pagan#pagan witch#christian witch#heathen#norse paganism#my writing#mine

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Making My Own Post™️ because im not indigenous, and because the post that spurred this on was about Palestine as well, so i don’t want to derail it. that said, it does have me very emotional because i grew up in the central valley of california, and i do my best to pay attention to the land i’m on and the people who know it best. i think that anybody who really cares about the land that america encompasses and learning about what it was like before it was devastated by the arrival of white people would be able to understand my frustration.

i love the valley now, even in its dry and wounded state, because it is where i grew up, but it is obvious that the land was far, far healthier when it was in the care of the indigenous people of the area. that is because the ecosystem was maintained by and for those people.

i’m not indigenous, so i don’t presume to have any better knowledge than what was shared in the other post (which you really should check out before reading on), but what @omusa-inola and @dojense shared was the same as what i learned in my own personal research. the valley used to be home to black oak forests, which were maintained by the indigenous people that live there. black oaks are huge trees which provide essential shade from the intense central valley sun. black oaks also build a root network that nourishes other plants that the indigenous people of the area (including the miwoks, but also other tribes) relied on prior to the destruction of the oaks.

there is a very small black oak grove near where i used to live (that is now being threatened by kudzu, sadly) and standing underneath the cathedral-like shelter of a black oak’s sprawling branches and seeing what grows in their shadow really contextualizes the struggle of the valley. it’s obvious if you open your eyes and look. things grow easily under the black oaks. they don’t elsewhere. meanwhile, white people struggle to grow non-native crops under the direct sun, in huge monocultural fields, by dousing them with water daily. white people act like the valley is dry and barren by nature now, but it doesn’t have to be. it wasn’t before.

if you read that other post, you might be finding it clear that genocidal action and ecological disaster absolutely go hand in hand. both play into each other. california is just one example of that. the healthy, abundant ecosystem that worked for the valley, that was maintained by and for the indigenous people, was destroyed. the oaklands were chopped down, taking the livelihood of the indigenous people with them— all in order to make way for the white way of life. even now, surviving native plant and wildlife continues to die off every day as farms till to prepare for another season of stripping the soil of water and nutrients for profit, and even as farms are torn up and replaced by houses and apartments for the ever-increasing number of those who want to strike it rich in the golden state. public schools in CA continue to refuse to teach the truth about the indigenous people of the region, denying their importance and existence. sacred & historic sites are torn up because they’re worth so much more to capitalism if they’re replaced by a shitty apartment building or whatever.

the disturbed land of the valley is not only home to crops and densely-packed little houses, but it is also home to viciously invasive and highly flammable grasses that literally didnt exist in california before white people brought them over in bags of grain and crop seeds. the native plants that do manage to sprout up between the strawberries and almond trees are destroyed by tilling, but the tilling literally perpetuates the life cycle of these invasive grasses which choke out other life, suck the nutrients and water out of the soil, and then die on top of it in a dry, flammable heap. those invasive grasses also dominate the yellow, barren cow pastures between the orchards, and the black-burnt shoulders of the highways.

it’s confusing and mind-numbing to try to understand how California keeps making ecologically devastating decisions while maintaining the reputation of a Good, Liberal State. at least it was that way for me, until one of my visits to the black oak grove during that period of my life where i was struggling to grow my own food to eat. i saw how easily life springs up under the shadows of the trees even in the heat of a valley summer, and remembered that white people tore all of those life-giving trees down to plant rows of crops to sell off and to build labyrinths of identical houses. the answer is that the state of california is just another part of the capitalist colonial government that exists to perpetuate itself and kill everything and everyone that stands in its way, even until there is no california to rule over, burnt to the ground and then swallowed by the pacific.

no one has cared for the land better than the indigenous people who colonizers set out to erase. dont forget the damage that is done, because colonizer governments with no attachment to the land will never fix the ecological disasters they benefit from, even if that government is california, which brands itself as the most climate-conscious and progressive state. i encourage other americans to research the land you live on to learn what it was and who took care of it before it became built cookie-cutter houses, lawns, and factory farms. listen to the voices of indigenous people around you. it will be frustrating and saddening to learn what has been destroyed, but we have to learn.

anyway. #landback

#mine#my source is a lifetime of curiosity and research and living in the valley#also me trying to figure out what that dry yellow shit killing all of my plants was#also me trying to figure out why things grew better if they were closer to the neighbor's tree lol#also me going to the oak grove and just looking around whenever i was this close to ending it (:#and so on and so forth#valley ag

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Existence of Capitalism in Skyword Sword and How it Makes No Sense Contextually

First off, before I begin, I would like to make it clear that this is not meant to be a a post to bring politics into Zelda; it is my analysis of the information we are given about Skyloft and subsequent questioning of a lot of different canonical aspects. This also won't contain any major spoilers for Skyward Sword, as this is viewed almost entirely from a world-building perspective.

Continued beneath the cut (because this is a monstrous post)

The Canon Economy

In game, the citizens of Skyloft rely on a monetary system of trade, i.e. using money to purchase goods. This in and of itself works fine for the game, but I'll get into later why it's not very well founded later on. We see that the Skyloftians have to pay for necessities such as food in game. Seeing as this isn't something that carries much weight story-wise, it's hard to find lots of information, but it can be asssumed that Skyloft operates on a typical "use money to purchase goods" system.

Furthermore, the only large source of food we see in game (pumpkin island), appears to be owned privately. Patrons must pay to consume pumpkin soup. This indicates that other islands with the means for producing food may also be owned privately, though these theoretical islands do not exist canonically.

Most of this will become relevant as this post goes on; for now it offers contextual knowledge.

The Money Problem

Across the Zelda franchise, Rupees act as the main currency. It is not stated anywhere how or where Rupees are created, so there's a few potential routes.

1.) Rupees are mined from the earth.

In the very first installation of the franchise, rupees are referred to as Rubies by the game manual. Rubies being used to refer to them implies that they may share similar properties -- so from here we can assume that rupees are some sort of gemstone that are mined from the earth and made into money. If you're thinking, "but money is made out of paper, why would they use gemstones?", then I will direct you to the historical use of silver and gold as currency.

2.) Rupees are created magically.

In game, rupees can be obtained in an eclectic variety of methods. Killing monsters, cutting grass, and so on and so forth. This could imply that they are generated by some outside force at seemingly random. This particular theory is the weakest of the three.

3.) Rupees are formed via living organisms.

Hear me out. Seeing as a potential drop of enemies is rupees, the creation of rupees is not explicitly stated, and they're not so common that they're essentially worthless, one could assume that, similar to pearls, rupees are created by living organisms. This would explain why they are dropped sometimes by enemies, and even why you find them in the grass (outside of the minish) -- if a monster dies, the rupee(s) could be left behind in the grass and so forth.

When taken in the context of Skyloft, the theoretical origin of rupees that makes the most sense at a first glance is the second one -- there are few monsters on Skyloft, which rules out no. 3, and seeing as they have very limited ground to work with, mining is out of the question. However, when we look at the option of magical origins, it starts to break down -- they can't exactly disperse any excess money, as they are extremely limited in who they can trade with, and if money just keeps showing up out of nowhere the economy will inevitably undergo inflation, which wouldn't be good for anyone.

So, this leaves us with a limited supply of rupees on Skyloft, following either theory 1 or 3.

The problem here is that they live on a floating island, and frequently travel between multiple of these islands. If, say, one was to drop something off the edge, we know that it would be as good as lost canonically -- they cannot reach the surface, and therefore have no method of retrieving any objects lost in this manner.

In my initial ramble about this, the example I used was this: Young children clearly exist on Skyloft, and typically children enjoy playing with things and imitating their parents. I'm sure most people have had an experience in which a young child has either destroyed or lost money. If there's one toddler that has the idea to start chucking money over the edge, they could potentially even wreck the economy depending on the current finite amount of rupees available on Skyloft and the amount of which is being thrown off. Basically, the economy of Skyloft could be wrecked by a child.

They could potentially use something other than rupees as money, but options here are pretty much nonexistent -- what would they use? The amount of resources they'd have to use to produce money simply wouldn't make sense, seeing as they have limited resources -- which brings us to our next section.

Limited Resources

To add to the dubious monetary system of Skyloft, we have the very clearly limited resources. They live on floating islands. In the sky. With no access to the greater world below. They have very limited room for production. Even with the small canonical population of Skyloft (we're strongly going to assume that the npcs present in SkSw are not the extent of the sky's population, however, because otherwise they'd be competing with the lines of the european royalty), managing food would be a large and very important undertaking. In order to keep myself going a rant worthy of its own post, I won't be going too into depth on how they would make use of the land for survival. All that is needed to know is that food is very much limited and also, obviously, essential for survival.

When looking at an isolated community like this, food would likely be the most important part of life on Skyloft. If food isn't available, you die. Given that it is so important to have food in this situation, it would be a reasonable assumption to have a community in which everyone works to ensure the production of food. With these circumstances, the private ownership (for profit) of gardens is both unrealistic and extremely unethical. Farmers could charge a premium for food, making themselves extremely wealthy, and everyone else would be forced to pay these rates in order to survive.

Summary of Canonical Issues

Basically, we have this community in which resources are vastly limited, obtaining replacements for lost money is more-or-less out of the question, and the community would likely be all working together for the collective benefit of said community. In this context, having both money and capitalism make very little sense, and capitalism on its own is horribly unethical.

Potential Solutions

The full scope of world-building solutions to the "look at it wrong and it crumbles" situation of Skyloft gets into far more than the economy, and this post particularly was spawned from a conversation about Skyloftian food production. This will be pretty much a summary, but if I get around to making a separate post for the food and resources of Skyloft, I'll link it here and reblog this with a link as well. Anyways.

The conclusion I eventually came to falls into socialism. There's not really a central government on Skyloft, so production would be in the hands of the community at large. They would all be working for the benefit of one another and continued survival of their civilization, and seeing how essential food is, wages wouldn't really be a factor either -- you garden, or you die. This eliminates the need for money, as essential goods can be obtained via working for them and contributing to the community.

Outside of essentials, any luxury items could be obtained through the trade of items or skill, which would make sense. Someone who is, for example, a woodcarver, could want silk from a weaver. Instead of paying in money, which wouldn't serve any purpose outside of luxury items, they could instead carve something for the weaver. This continues to promote the learning and use of specialized skillsets while avoiding the money conundrum. Plus, seeing as Skyloft would likely be tightly knit as a community, it fits far nicer than charging your neighbor ridiculous prices.

Also, as a bonus thought, Rupees would probably just be seen as gemstones on Skyloft. They could be used by craftsman or as decoration.

I'm at a loss as to how to end this post, because I pretty much summed up the bulk of everything I could without going on wild tangents, so I leave you with this:

#long post#skyward sword#skyward sword worldbuilding#skyward sword anaylsis#analyzing video games#my mom poked her head into my room like halfway through and thought it was a school assignment and asked how the essay was coming#i didn't have the heart to let her know that her kid is ranting about the unethicality of capitalism in a fictional world in a video game#essay#casey gone feral#essays theories and worldbuilding#worldbuilding#i need a tag for posts like these#uhhhhhhh#zelda worldbuilding#zelda analysis#questioning canon#questioning things that were clearly meant to not be questioned#i blame faye /lh#ask me about how this affects my take on Sky#or don't i'll probably ramble about it at some point anyways#zelda theory#i guess technically sorta#caseyworldbuildsandetc

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

OC Questionnaire

I was tagged by @enasallavellan Thank You! This was really fun!

Answering for my Dragon Age: Inquisition OC from my ongoing fanfic series on AO3.

(This got a little long so more below the cut)

THE BASICS:

Character’s name:

Anyssa McBride

Role in story:

Inquisition Historian from Earth (MGIT story; Anchor series on AO3)

Physical description:

5ft 6in, wavy honey blonde hair that currently reaches midway down her back (on Earth it was roughly shoulder length, ice blue eyes

Age:

She is 26 when she arrives in Thedas and currently is 29 in my story. (She will be 30 shortly after the events set in Trespasser)

MBTI/Enneagram Personality Type:

I took two different tests when I created Anyssa and both labeled her as ‘ENFJ’—the giver or mentor. (I would argue that while she tested as an extrovert she does appreciate introvertedness and the current situation dictates which she chooses to be)

INTERNAL LIFE:

What is their greatest fear?

Being used and taken for granted

Inner motivation:

To help others and support them, hoping to see them happy

Kryptonite:

Having her self-doubts realized

What is their misbelief about the world?

Anyssa believes that everyone wants help and they just do not know how to ask for it. Unfortunately she has found out that some people just don’t want help no matter how sincere you are.

Lesson they need to learn:

She needs to learn to trust herself. Those around her know of her past on Earth and have made efforts to help her learn that. But no matter what, she still struggles with it, sometimes to the point of questioning whether she deserves the life she now has.

What is the best thing in their life?

A group of people who love and care for her. In other words, Friends

What is the worst thing in their life?

A history on Earth of those that were supposed to care for her, using her instead…and abuse. After her parents died in a car crash during her junior in high school, she went to live with her aunt and uncle who proceeded to steal the money her parents had left her for college. Later she entered into a relationship with a seemingly charming man named Bryan who turned out to be emotionally and physically abusive towards her. After two years she worked up the courage to attempt to leave. After multiple tries, she finally succeeded only to end up in Thedas.

What do they most often look down on people for?

Taking advantage of others, being cruel/mean to others, judging other without taking into consideration what they have been through

What makes his/her/their heart feel alive?

Writing stories based on those around her, sharing her knowledge with people who appreciate it, learning about the cultures and people around her, horseback riding, rock climbing, exploring the tunnels under Skyhold

What makes them feel loved, and who was the last person to make them feel that way?

The people she had come to know as friends in Thedas. They have become her ‘found’ family—something she thought to never have again. The last person to make her feel that way is Cullen. He always knows the right thing to say or the right thing to do to let her know she is loved.

Top three things they value most in life?

Acceptance by others, support of others, friendship

EXTERNAL LIFE:

Is there an object they can’t bear to part with and why?

No personal items from Earth made it through the rift to Thedas with Anyssa. What she has come to cherish most is the small items her friends have given her in an effort to make she feel at home. Most notably is the Cullen’s coin she wears around her neck and a stuffed dragon named Puff he gave her before they ever began their relationship.

Describe a typical outfit for them from top to bottom.

For her normal duties as historian, she wears simple dresses common to Ferelden fashion as well as blouses and skirts. For more formal affaires she wears one the many dresses Vivienne had made for her that incorporates Orlesian, Fereldan, and Free Marcher styles. For when she explores the caverns below Skyhold or travels away from the keep, she prefers typical traveling clothes and pants over skirts.

Most of her clothes are shades of light blue which Cullen said matches her eyes. She also wears purple in various shades being as it is her favorite color.

What names or nicknames have they been called throughout their life?

Nyssa and Nys. Most of her friends have called her Nyssa at some point in her life. Nys is only used by Cullen. He has also been known to use the endearment “sweetling” after they began their relationship.

What is their method of manipulation?

Anyssa isn’t known for manipulating anyone out right. Most of the time, she will rephrase an argument point to make the other party believe they are making a choice freely. This is not something she employs with people she is friends with or allied with. It a trick she holds in reserve when dealing with unreasonable nobles, especially when she has been called on to aid Josephine.

However, she is not above manipulating Cullen to either ensure he does not take on too much or because she would like some private time with him. A bright smile and repeatedly saying ‘please’ usually works. The first time Cullen realized he could not say no to her was when she asked to see a real dragon. In the end, he gifted her a stuffed dragon she named Puff and then took her to Crestwood to see the dragon there (from a safe distance of course.)

Describe their daily routine.

Anyssa’s routine various from day to day depending on the work load and what other duties she’s been tasked with. Normally, she holds any meetings in the morning and she makes time to watch the sparring ring from the battlements (especially if Cullen is participating). After that she may conduct any research she can on historical items the Inquisition has acquired and writes any correspondence to allies that might have knowledge she does not. She frequently checks in with Dagna in the Undercroft and reports the archanist’s progress to those interested. (Most people tend to shy away from Dagna but Anyssa finds her fascinating and funny.) She often finds Cullen for lunch and reminds him to eat. Her afternoons might involve cataloging artfifacts and tomes recovered in the hopes of returning them to their proper owners. If time allows, she can be found exploring and mapping the caverns and tunnels below Skyhold much to Cullen’s dismay. Throughout her day though, Anyssa has learned to work in time for her friends as well as for herself (though it has been a struggle in learning to do so)

Their go-to cure for a bad day?

There a several different answers to this. One is Sera. Both Anyssa and the Red Jenny enjoy pranks. Frequently Anyssa may provide the idea or inspiration while Sera carries out the actual pranks itself.

Horseback riding alone or with Cullen.

Playing Wicked Grace with Varric and/or Bull, Blackwall, and the Chargers. (Drinking and storytelling maybe involved.)

Reading a book with Cullen.

GOALS:

How are they dissatisfied with their life?

Overall, Anyssa is exceedingly happy with her life in Thedas. It is something she never thought to have again after her parents death and the abusive relationship with her ex-boyfriend. She had friends, a family, a career, someone to love her (whom she loves with all her heart), and a new purpose in life. If there was one thing that she would be dissatisfied with, it would be the knowledge that despite all the good the Inquisition did there will still be people who still cling to the old ways. In other words, she wishes that everyone could find the acceptance and support she has found but knows that the old ways are easier for some to hold onto instead of embracing change.

What would bring them true happiness or contentment?

Finally realizing that she did nothing wrong and it was not her fault that anyone left her or treated her poorly. Those were decisions made by others and she is not responsible for that. Cullen has aided her greatly in making progress with this but it is a struggle she will always have. But then again she has found a support network and love, so in the end she is already happy/content.

What definitive step could they take to turn their dream into a reality?

This is something Anyssa initially struggled with. Cullen was the first to admit he loved her and it took seven months before she could say it back. After that, they talked circles around making concrete plans about their future. Finally, they decided to just make the plans as they went (making a list of things they wanted.) When Cullen decided to start a Templar sanctuary after retirement, that solidified things. Now all that remains to be done is see the Inquisition through to the end and then begin their future.

How has their fear kept them from taking this action already?

Her past relationship colored how she reacted to Cullen’s affections and made her question whether she could trust his words. (she learned to trust his actions first and then his words)

Haven and Skyhold were the places she first felt welcomed in Thedas, like she had a real home again.

She questioned whether she could be lead historian in a world she knew nothing of, questioning even the skills she had learned on Earth.

How do they feel they can accomplish their goal while still steering clear of the thing they are afraid of?

Anyssa has decided to focus on what she can do in the present and prepare for the future she wants. She has begun making plans for how to transfer her skills to a slightly different career path aft her the conclusion of the Inquisition and has told Cullen she will support his dream of a Templar sanctuary while pursuing her own path. To ensure that happens, she will more than likely rely on Cullen for reminders to believe in herself and trust that she knows what she is doing. In the end, it all comes down to trust for Anyssa and her Commander is the one she trusts the most.

Tagging @commanderadorkable, @shadoedseptmber, @raflesia65, @noire-pandora and anyone else who would like to play! No pressure, just fun!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avenge My Twistery Depth — Thoughts on: Trail of the Twister (TOT)

Previous Metas: SCK/SCK2, STFD, MHM, TRT, FIN, SSH, DOG, CAR, DDI, SHA, CUR, CLK, TRN, DAN, CRE, ICE, CRY, VEN, HAU, RAN, WAC

Hello and welcome to a Nancy Drew meta series! 30 metas, 30 Nancy Drew Games that I’m comfortable with doing meta about. Hot takes, cold takes, and just Takes will abound, but one thing’s for sure: they’ll all be longer than I mean them to be.

Each meta will have different distinct sections: an Introduction, an exploration of the Title, an explanation of the Mystery, a run-through of the Suspects. Then, I’ll tackle some of my favorite and least favorite things about the game, and finish it off with ideas on how to improve it.

If any game requires an extra section or two, they’ll be listed in the paragraph above, along with links to previous metas.

These metas are not spoiler free, though I’ll list any games/media that they might spoil here: TOT, WAC, mentions of GTH.

The Intro:

Let’s talk about Trail of the Twister, shall we? No clever intro, no pun, no sassy statement on the quality (whether lacking or overflowing) of the game…let’s just Talk.

Like I said at the beginning of my WAC meta, TOT is one of two games that doesn’t really fit into a category besides it and WAC demonstrating HER’s growing pains. The world opens (kinda), the characters get a little deeper (kinda) and a few new things are tried with plots and character (to varying degrees of success). Both WAC and TOT — but especially TOT — represent a shift in the tone of the games and their approach. You can ascribe this to a lot of reasons — an aging fanbase, technology marching on, a new writer in the mix — but you really can’t ignore it, no matter if you’re a Classic Games Elitist or a Newer Games Snob (or neither one).

To paraphrase a fabulous song, there’s something there that wasn’t there before.

This is not me saying in any way that TOT is a fabulous — or even moderately successful — game. In fact, it whiffs a lot where WAC hit solidly, which makes playing them one after the other a sort of chore; WAC is weighed down by the knowledge of what comes next (after such a brief respite from games like ICE, HAU, and RAN), and TOT’s repetitive chore list seems even bleaker after the snack shop and secret societies of WAC.

Which is truly unfortunate, because hiding behind the rat traps and the car chases (or drives, if you drive like a normal person in this game) and the endless moon chunk offerings is one heck of a story. Unfinished and beleaguered and (to my suspicions) censored as it is, there is a definite, multilayered, morally ambiguous, honest-to-moon-chunk story in TOT.

Like I said, something there that wasn’t there before.

Playing through the games in order, it seems like the reason WAC is so solid is, in part, because the games before it have so little cohesive story as to be laughable. Playing them out of order will show you that though WAC does come off a little better than it actually is due to the games that came before it, it’s also actually a step-up from a lot of games in the complexity of its plot and characters. At this point in the series that’s about to happen a lot, but WAC is the first real instance where you get it. Like I said, these two games mark a tonal and approach-based shift in the games.

So let’s turn our attention to TOT.

There are a lot of things that bog down this game — it feels sometimes as if you’re simply going through Farmville-esque tasks to get from Point A to Point B — but its plot and characters (save in one large instance) aren’t actually the culprits. Surprisingly enough, we have a mystery here with enough twists, turns, small crimes, and red herrings to make for a perfectly serviceable plot with relatively well-developed (for the length of the game) characters (whom I’ll go into more below).

A huge difference from a lot of the games is that we have a prominent unseen character who isn’t the one who hired Nancy or who is part of the historical background. Brooke’s actions actively move the plot along no matter what Nancy does, and I do like that the world of TOT goes on spinning (as it were) without Nancy driving everything.

You get the sense that Nancy truly was just dropped into the middle of this without having any control over the situation, and that she spends the entire game (or most of it) playing catch-up, rather than being on the scene for the crime(s) or arriving shortly thereafter.

In TOT, this sabotage has been going on for a while — the competition is nearly over, in fact — and Nancy has to actually do some detective work to even get caught up, let alone to try to step a few feet in front of the guilty party.

One interesting thing is what TOT and WAC share: they both feature casts who are only a few years off of Nancy’s age; in WAC, they’re a tiny bit younger, while in TOT, they’re a tiny bit older. Nancy, being Nancy, is much more in her element with the ages of her suspects in TOT than she is with high schoolers — with how much time Nancy spends around people significantly older than her, I’d be shocked if she got along well with high schoolers when she was in high school herself.

As a side note, I know it’s sort of a fandom thing that Nancy gets along well with children, but honestly outside of Lucas, it’s not something we really see (no, I’m not counting pelting Freddie with snow 10 times sans mercy as getting along with children) — and honestly Lucas is just charming, so I see no reason why Nancy wouldn’t get along with him. Generally speaking, kids who grow up the way Nancy has [especially as an only child] are far more comfortable with ‘adults’ — well established, 35/40+ adults, who make up the majority of her suspect pools — than they are with peers or children.

There’s also a great deal of care taken with making all the suspects (mostly) equally likely for a large portion of the game; it’s not until past the halfway point that a suspect (Chase) is cleared due to his confession of a different crime, and even then, he doesn’t really become Nancy’s helper, as is the usual case with cleared suspects. This is actually one of the few games where Nancy doesn’t really have a helper; she relies on herself, the Hardy Boys, and (questionably) P. G. Krolmeister to get the job done.

And speaking of the Hardy Boys…you knew an intro wouldn’t be complete without my mentioning them, hush.

The Hardy Boys are arguably the set piece that benefit most from Nik’s writing (and yes, I’m going to ascribe it to him; he’s the most prominent variable). Don’t get me wrong, the Hardy Boys were great before, but the Nik games are where they start attaining a place of more prominence and solidify their distinct personalities other than “focused killjoy and playful scamp”. In this game, you get more of Frank’s protectiveness (directed towards Nancy) and Joe’s actual sleuthing abilities — not the least of which because this game coincides with that DS Masterpiece “Treasure on the Tracks”.

Oh yeah, we’re going there. It’s relevant.

Treasure on the Tracks, as mentioned, was a game for the Nintendo DS (and the only one, mind you) focusing on the Hardy Boys. In the game (as in TOT), they’re tracking down the Romanov treasure with the help of a surprising ally — Samantha Quick herself. Samantha is under orders (from who, she never says, but a future game makes it obvious) to help the boys find the treasure aboard the royal train that the Romanovs used to own.

And yes, I would have loved that to be a joint Nancy Drew/Hardy Boys PC game, but I’ll push the bitterness aside for the facts. Which are that this game has a rad premise and would have been a very cool addition to the ND series…but I digress. Regardless, that’s what the boys are doing during TOT, so we get little hints to their investigation as well as having them help Nancy out.

I love that the Hardy Boys have an actual mystery that they’re investigating, as beginning with this game we see a lot more of their ‘agent’ side being brought out. It’s nice to feel that Nancy isn’t alone out there fighting against the forces of evil, and gives excuses to have the Hardy Boys in the games more, so I’m a big fan in general. It also helps build them up as investigators; while they offer hints to Nancy a lot, we don’t get to see them doing a lot of spy/detective work, and it’s lovely to be able to see it here.

And I love their sibling banter. It’s obvious that JVS and Rob Jones have a lot of fun with their roles, and it really lightens and enhances any Nancy Drew game that they’re in.

The last interesting thing that I’ll point out before diving into the game itself is what TOT does for the world of Nancy Drew. Beginning with this game, we start the tradition of each game leading directly into the next one; for her help in TOT, Krolmeister sends her to his favorite ryokan in Japan, which leads to her being hired for CAP; her absence and fight with Ned in CAP lead her back home for the Clues Challenge in ASH, and so on and so forth.

It really makes the world feel solid and cohesive, and lets our characters grow and shift and change without making it feel episodic or sudden. The Nancy of SPY is quite different from the Nancy of TOT in how she behaves and tackles mysteries, but her character growth throughout the games in between make it feel right and natural — like actual character growth.

The Title:

As a title, “Trail of the Twister” isn’t bad — it’s got that alliteration that ND books tend to like doing, and makes it feel a little classic. It also gets a play with words in there — you’re tracing the actual trail of the actual twister, and you’re also walking through the evidence left behind (aka a trail) of a twisting plot. Solid, if not exceptional, with its only real detriment being the hilarious acronym (TOT).

The book it’s (loosely) based off of is called “The Mystery of Tornado Alley” which, obvious to anyone with eyes, is a much worse title while telling us the same thing. It also doesn’t apply to the game as much – you’re not figuring out a mystery as much as unwinding the tangled threads of character motivations — and is supremely clunky to boot.

The Mystery:

Called in by P.G. Krolmeister to go undercover, Nancy joins a team of storm-chasers bent on winning a grant for their research — and beating the opposing team that wants the same thing. Nancy begins the mystery by finding a tin box full of cash (payment for an as-of-yet unspecified action) and it spirals from there, putting the not-so-amateur teen sleuth through her paces learning about tornados and storms, taking pictures, and trying her best to keep everyone happy and working towards the money.

It’s not as easy as it sounds, however. There are competing forces at work outside (and sometimes within) the two teams, and the personalities of the storm-chasers that Nancy must investigate mean that no one trusts anyone else. Things continue to go wrong and Nancy chases down the clues until the mother of all tornados hits town, and our culprit takes advantage of the distraction…

I mentioned above some censorship that I suspect went on in this game, and I’ll talk about it here. Given the darker themes of this game and the mentions of death and serious injury (more than most other games in the series at this point), I would say part of the reason why our story is a little more…displeasing, especially by the end, is that HER was really intent on the 10 part of the 10+ rating.

There’s lots to explore — the Ma storyline that goes nowhere, the collateral damage of these tornadoes, the fact that our cast is filled with genuinely unpleasant criminals — and yet it gets glanced over while feeling like the game is building up to it. Like CRE and ICE where I postulated a lot of the attention went to the new engine, I’m going to postulate here that the reason why we have hanging plot threads and injustice at the end (which I’ll talk about later) is that the game was censored by the HER bigwigs to ensure it still fit in a 10+ rating.

As a mystery, like I said above, there’s absolutely nothing wrong here. We’ve got plenty of means/motive/opportunity spread out in our cast (and in the periphery cast, just to keep things interesting), the threads and smaller crimes/wrongdoings/etc. are realistic in scope and in motive to keep them hidden, and it’s the personalities of the suspects that give us our conflict and tension, rather than random “interferences” by the writers. And speaking of our suspects, let’s go to the other area that TOT does (almost) nothing wrong.

The Suspects:

First off is Chase Releford, a junior who took Scott’s class for a science credit who got super interested in the actual work. The team’s handyman, Chase has noticed (and fixed, and fixed again) the equipment acting up, and is being stretched pretty thin in order to keep it all shipshape and in working order.

He’s also one of Nancy’s sources of Pa Pennies, if you wanna spend hours doing circuit boards.

As a culprit, Chase is a great option (which is a sentiment you’ll hear repeated for all of our suspects, never fear). He’s secretly spending his time looking for oil with Pa’s divining rods, which puts two crimes on his conscience (stealing the rods and not working on company time) and helps the team fall even further behind. It’s important to note that for a large chunk of this game, the likelihood of the suspect also hinges on how much they want Scott to fail, and Chase is pretty much the only one without any real anger towards Scott.

The owner of the local general store, Pa Ochs might be a surprising option to put ahead of Chase in order of culprit likelihood/suitability, but I stand by it. Having lost his wife (Betsy “Ma” Ochs) to a tornado (the warning sirens, which were Scott’s responsibility, didn’t go off), Pa alone mans the counter, helping Nancy find everything she needs — for a price, of course.

The price being annoyingly hard to get Pa Pennies. Unless you exploit a glitch.

Here’s where we start with the culprit possibilities that have an actual grudge against Scott. Though not as angry as he could be, Pa is deeply hurt by the loss of his wife Betsy, and has grounds for an axe to grind with Scott. As much as I would have loved to have the ‘friendly general store owner’ be the culprit, it would have been like a mix of DOG’s Emily and FIN’s Joseph (minus the Crazy), and it’s (sadly) best to leave that ground alone without re-treading it.

Frosty Harlow is next up; a second-year grad student in digital media, Frosty got his nickname (his real name is Tobias) from his storm photography and is, well, trying to re-capture that lightning in a bottle.

He also screams like a little girl. So that’s fun.

Like Chase and Pa, Frosty is a wonderful option for a culprit. His crime is selling university property (the video of the storm he and Nancy shot) to an aspiring photographer (who happens to be on the rival team) to help them get a toehold into the business, along with working with Debbie to try to stress Scott into quitting.

What really makes Frosty stand out is that, unlike Chase, Frosty doesn’t feel bad about what he did at all. He also holds far more animosity towards Scott than Pa does, and has a little more…innate anger as a person.

If you haven’t noticed by now, we’re going in order of “worst” culprit option to “best” (and then the actual culprit), and it really says something about how fleshed out these characters already are that we start with people who are solid options to begin with.

Though only appearing vocally and for a few minutes total of the game’s runtime, I’m going to list Brooke Tavanah as our next most likely culprit — in part because, well, she kind of is our culprit. The leader of the rival storm-chasing team, Brooke offered Scott money to sabotage his own team to let her team win the grant — an offer that he takes her up on.

Of course, Brooke isn’t the only one sleeping with the enemy (so to speak) to ensure her team’s victory; her videographer, Erin, is apparently so talentless as to need to buy footage from Scott’s team as well.

Things don’t exactly look great for the Kingston University team — as they can’t really get ahead even through sabotage and skullduggery, and one does wonder if they’d even be able to put the grant to good use. That, of course, is not the point; Brooke wants her team to win, come hell or high…wind…and a little thing like scientific ability isn’t going to stop her.

(Interestingly enough, this is the first of three times we’ll see Kingston University pop up; we meet their alumni again in TMB and DED).

I love that Brooke is guilty, because so often in Nancy Drew games the tendency is to implicate an unseen character and then to have that implication be a poorly done red herring. Instead, Brooke isn’t a distraction, nor a smoke screen — she’s just another piece of the puzzle.

Our last non-Culprit (by the games’ common definition) suspect is Debbie Kircum, a recent PhD graduate who is on her fifth time working with Scott in chase season, and who has gotten a lucrative offer to teach at a university in New York.

Worrying that Scott would let his resentment towards the college hurt their chances in the competition, Debbie leads the conspiracy to stress him out so much that he just quits. I’ll talk more about this later, but it is both one of my favorite and least favorite things about this game. For now, I’ll say that her plan works…but not the way that she planned; for her and lots of other suspects in this and upcoming games, the quote “the price for getting what you want is getting what you once wanted” works perfectly to describe their arcs.

As a culprit, (as Debbie fully qualifies as a culprit), Debbie certainly has the shortsightedness and nastiness that Nancy Drew culprits tend to have. She’s extremely good at getting what she wants…but see the quote in the previous paragraph.

She also over-contours her cheeks so much that it looks like someone slapped her with an open compact of bronzer.

That takes us to our final culprit and character, Scott Varnell, genius professor of meteorology and the leader of the Canute team. Scott is my personal favorite character not just because he’s the most interesting, but because he’s a tragic figure who isn’t historical/dead, and those are a bit of a rarity in Nancy Drew games, especially at this point.

Being an expert on tornadoes yet denied tenure based on his personality, rather than his academic prowess (a gripe I share as it applies to jobs/academia), Scott holds a grudge against those who don’t recognize his contributions to meteorology and to the study of tornadoes specifically. Unbeknownst to him, two members of his four-man team have been conspiring to stress him out so badly that he’ll just quit, as they think he’ll be a hindrance (again, due to his personality) in winning the competition.

Scott is in some ways the obvious option, and yet the game never turns into a howdunnit. Throughout the mystery he tends to be the prime suspect, but is also the prime victim — a dichotomy we’ve never seen before in the Nancy Drew Games. I’ll talk more about Scott below (a sentence increasingly common in this meta), but I both love and hate him as the culprit, and that’s something new (and interesting) that TOT brings as well.

The Favorite:

Don’t worry, we’ll get into TOT’s myriad flaws soon enough, but for now I want to focus on what it does right.

The first thing the game nails is the Hardy Boys. Their inclusion, their plot, their characterization, the voice acting — all of it is nigh-flawless, and is by far the most enjoyable part of the game. Don’t get me wrong, the Hardy Boys are usually quite far up there on the list of things I love about a game with them in it, but they really start to shine more in TOT, gaining some character development, plot relevance, and just overall depth.

Oddly (or perhaps not oddly at all) I don’t have a favorite moment nor a favorite puzzle in this game; barring that, I’ll talk about some of the great threads to the game, rather than any particular moment/puzzle that stands out.

I love that we get new and interesting layers to our story and characters. As I mentioned briefly above, there’s a real sense of the world existing before Nancy’s arrival, which works wonders for the world of the games, and our characters here are more layered, more distinct, and more ‘realistic’ (for the value of ‘realism’ in stories) than they ever have been before.

This is a game unafraid to deal with the topics of death and mistakes, and that accounts for part of the depth to the game as well. No, not the whole “Where’s Ma” thing — which I fully believe to just be a script that didn’t fire/didn’t stop firing in the game’s code after finding the newspaper that says exactly what happened to Ma — I’m talking about Scott’s mistake in the tornado warning system, Debbie and Frosty’s mistakes in dealing with Scott (which I’ll talk more about), and even Brooke’s miscalculations that lead to the ending of the game. Everyone here deals with the fallout of their mistakes, and it’s how they handle it that forms the basis for our plot.

It’s a seemingly small thing, but I love the sheer level of detail in this game. You can click on everything, read everything, explore everywhere — there’s a lot of information crammed into the game that sometimes you won’t get until the second or third replay (that is, if you have the stomach to play through this game repeatedly).

The use of our tertiary NPCs (Brooke, Krolmeister, Erin) is also inspired; they help the world feel whole and varied rather than existing simply for the benefit of the game, and show that Nancy doesn’t have control over everything when she’s investigating — and that she can be wrong in her focus of investigating (whether because she pays too much or not enough attention to the ‘minor’ characters).

Speaking of characters, I also love that our characters in this game – our suspects — are able to be fully formed without (on purpose, I feel) being particularly likable. It’s always fun to get a cast of characters that are hostile to Nancy, but TOT’s characters are slightly different from that: they just don’t care about her. She’s another intern to them, nigh-invisible except when they need a chore done. Nancy also doesn’t really try to befriend anyone because of it, and I like that too. Sometimes, a game should just be 1 vs 4, with some backup in the wings courtesy of phone friends.

The last facet of the game that I love is Scott himself as a character. Sure he’s cantankerous, blunt, egotistical, and a thousand other things, but the game is very clear that these ‘faults’ don’t make him anything other than what he is — a brilliant meteorologist and the foremost mind when it comes to tornadoes and tornadogenesis. The university undervalues him, but the team really can’t function without him, sabotage or no sabotage.

His motive for the sabotage isn’t the money nor fame — it’s simple tit-for-tat. For such a complex game (note, I’m still not saying it’s a fun or good game), our ultimate motive is deceptively simple: do unto others what they have done unto you. Tired of being devalued and having his worth judged on his personality rather than his work, he decides that if the university doesn’t care enough to keep him around (and for his worth as a professor, look at how accomplished and passionate his team of former students is), then they don’t care to keep up their program either.

It’s hard not to sympathize with that, especially if you’re the kind of person who’s been valued based on any defects in your personality — rather than your ability to do a job and do it well — and been found wanting. Whether you’re too serious (or not serious enough), too flighty (or too inflexible), or any other stupid “personality defect” that the workforce loves to throw around, we’ve all heard it before. Scott’s thrown into an unfair situation and — wrongly or not — decides that his troubles are going to have trouble with him.

The last thing I’ll add on the topic of Scott for this section is that I do love that Debbie and Frosty create their own villain. In figuring that Scott’s personality is going to prevent them from getting the grant (never mind the 4 other years that Debbie’s been on this team with him where it hasn’t been a problem), they decide to screw him over presumptively — and thus create a Scott who actually does want to prevent them from getting the grant. It’s usually a mark of a solid story (and solid writing in general) where the villain is created not from some problem inherent in them, but because they’re perceived to be a problem in the future — and thus live down to the expectation.

The Un-Favorite:

The problem with everything TOT does right — and that’s nearly a thousand words about what it does right above — is that it never combines to make a game that’s enjoyable to play. Before I go into the specifics, I do want to make that clear; TOT is a fascinating game to think and write about, but it’s honestly nigh-unplayable. The puzzles and chores are laborious (and repeated ad nauseum), pieces of the plot don’t make sense, and the ending is the bleakest in the series until GTH’s multiple endings took the cake.

A game should be well-written, complex, and interesting, but it just has to be fun to play as well. It has to. And that seems to have been forgotten during the course of making TOT. My least favorite moment is the ending of the game (more on that below), but I don’t have a least favorite puzzle — on the basis that most of the puzzles are equally bad. There’s no real standout…but that’s not a good thing.

Now let’s get into some of the bits and parts of the game that I really despise.

The handling of Scott is one of my favorite parts of the game, but it’s also my least favorite part of the game as well. They’ve set up a character who firmly believes that everything ends poorly, that he’ll never profit no matter what, and that, ultimately, no matter how hard he tries, nothing will go the way it should. And then the game confirms that worldview to the end. There’s no other option; no matter what Scott does or doesn’t do, no matter if he tries his best or blows it off, the end result is the same, and that’s a tragedy. Sure, you can argue it’s his actions that led him to a bad ending, but he only took those actions because he was heading to a bad ending anyway.

The feeling you get at the end of the game isn’t a feeling of justice served, nor success — it’s pity in a way that’s never been cultivated for any criminal up to this point in the series. And it’s not cathartic — it’s just more misery.

The other huge thing that I hate about this game ties into it — there really is no justice. The supposed ‘happy ending’ is Debbie getting people from both teams to ‘win’ the grant (where does it ultimately go — Canute or Kingston? Can it count as winning if there’s only one team? HER certainly didn’t bother to think about these things)…but Debbie’s hands are just as filthy — and I think more so — than Scott’s are.

Debbie leads Frosty in conspiring to make Scott quit and actually created their own monster — does she even know Scott at all? He’s lead a team through at least the last 4 years, probably more, and not had a problem; why now? Power? Greed? Pride? Whichever way you spin it, she and Frosty are guilty.

Frosty and Erin (of the Kingston Team) are also guilty on a separate charge; Erin for buying the footage and Frosty for selling it. If Brooke and Scott are kicked off, Frosty and Erin (at least) should also go for the same conspiracy charge. Everyone on the team (excepting possibly Chase) knowingly sabotaged their team; why is Scott the only one punished? Why does Debbie (and Frosty, and Erin) get off scot-free (pun intended) to win the prize, despite everything?

When I say that there’s no justice nor success here, this is what I mean. The whole thing stinks from top to bottom, and any way you look at it, a culprit walks.

Honestly, the ending should have just been “Chase, guilty only of petty theft, led the team (of himself and Pa) and was given the grant, which they donated to a charity for tornado victims”. Kingston actively cheated and Canute doesn’t deserve it either. In a game where everyone deserves to lose, declaring a winner just leaves a bad taste in my mouth — and a black mark on the game.

The Fix:

So how would I fix Trail of the Twister?

My feeling is that if you’re going to go with a downer ending — which TOT is — then go for a full one. Have Nancy discover everyone’s crimes — and I do mean everyone’s — and report to Krolmeister, asking what he wants her to do. Don’t forget, Nancy’s got an actual client in this game, and can’t go off half-cocked like she tends to in her more informal mysteries.

In the end, as nearly everyone would be disqualified, the competition should go to a third party — a storm chasing team that’s not Kingston nor Canute — and create chances for less corrupt institutions to study tornadoes at a level they haven’t been able to before. Sure, our suspects would lose, but, honestly, outside Chase…does anyone deserve to win?

I’d also be a fan of Scott getting a second chance due to outside sabotage (directed solely at him) with a job opportunity to consult for storm chasers. It’d be an arena where he’d be seen as the expert he is, without having to deal with the namby-pamby bureaucracy that infects universities (and that he hates anyway). He’d get the name recognition and the ability to actually do work in his field that he needs without being put in situations where he can’t help but fail. Honestly, I’d prefer that P. G. Krolmeister offered it (while saying he’s going to be keeping an eye on him), but really anything would do.

Exposing the crimes of everyone – and focusing on more than just Scott’s — would be the quickest way to improve the story of the game. The puzzles, on the other hand, need to be completely redone; a mix of ostensibly tornado-related intern-type chores (like the circuit boards) and more detective-type puzzles (fingerprinting suspects for a match on the tin bribe box, tracking everyone’s movements, solving codes used for communication) would be a big help in making TOT not just feel like a list of chores with a bad ending.

Oh, and fix the broken code leading Nancy to ask about a man’s dead wife over and over again. She lacks tact as it is.

#nancy drew#clue crew#nancy drew games#trail of the twister#nancy drew meta#my meta#TOT#video games#long post

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you so much to @herosofmarvelanddc @cloudypaws and @mtab2260 for the tag! This was so much fun to think about :)

(fair warning, I wrote too much for many of these...)

1. How many works do you have on AO3?

Just 2 :)

2. What's your total AO3 word count?

450,577 if I did my math right!

3. How many fandoms have you written for and what are they?

Officially? Just 1 - Agents of Shield (two, I guess, if you count MCU as separate, since I use characters from both...). Off the record, many more than that! I have lots of bits and bobs from other fandoms that I tinkered with when I was younger, still getting the hang of writing, not brave enough to post things, etc. etc. Some of those include X-Men, Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, the Fosters, Star Wars, the Hunger Games, the 39 Clues, and a few others I can’t remember. None of those will likely see the light of day, mostly because they’re unfinished, not very good, and just not reflective of who I am as a writer anymore, but they were fun to play around with at the time :)

4. What are your top 5 fics by kudos?

I just have the two, but The Important Thing is to Try wins, hands down, with 1227. Shoulder to Shoulder has 95, though, which I’m also very proud of! Important Thing has a definite advantage, being as long as it is, so I don’t know if that’s really a fair comparison between them.

5. Do you respond to comments, why or why not?

Yes! Or at least, I always try to! I just can’t believe someone would be kind enough to take the time to tell me what they thought of my story, so I always want to take the time to thank them and return the favor :) Plus, as I’ve learned, it’s a fantastic way to get to know some really lovely people!

6. What's the fic you've written with the angstiest ending?

Well... I technically only have one story that has an ending, at least on Ao3, and it’s not an especially angsty one, since it ends in Phil and Melinda getting married :) I have some angsty chapter endings in Important Thing, if that counts? I’m not even sure if any of my unpublished fiddlings have angsty endings (most don’t have endings at all lol)... I don’t mind writing angst, but I don’t know if I’m capable of making something without a happy (or at least hopeful) ending.

7. Do you write crossovers? If so, what is the craziest one you've ever written?