#homeless teen

Text

Hey guys, I'm still currently homeless and I'm trying to save up money for a small foldable bed because I just can't take waking up with extreme joint pain and poor sleep every day from sleeping on floors and I barely make enough money to get by alongside college, please if you could donate I'd really appreciate it,

If you could boost this post even if you can't donate I'd be happy just please share this if you can I'm really struggling right now

thank you guys, I love you so much.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unhoused Joy: Cardboard Sleds

So often are unhoused youth stripped of the simple joys of childhood. Even if we weren’t homeless at a young age, most of us never had the type of childhood where you sled for hours and come inside to a cup of hot cocoa. But Chris and I were young teenagers and both trying our best to stay sober as friends around us struggled to do so.

We were living in the teen shelter together. We had grown close. Not like friends close, but like siblings close. He always poked me and pushed my buttons and in return I steered him away from trouble. Just like any good brother would.

In the harsh New England winters, there wasn’t much to do. We were both in high school and had too much energy for the library. There wasn’t anywhere else indoors to hang out for people our age in this god awful small town.

So Chris and I went for walks. We liked to hang out at this random tiny gazebo next to the fairgrounds. I’d chain smoke and we’d joke back and forth. I’d give him advice about the most recent trouble he absolutely was at fault for.

One night I see stacks of cardboard at the nearby dumpster. We grab them and use them to take turns sliding down the small hill. Chris eats shit and I die laughing. We repeat until the cardboard boxes have disintegrated from the weight of us and the cold freshly melted snow.

We walk back laughing and shivering to the youth shelter. We come inside and staff asks if we’re high and we can tell them honestly, no. Chris sits in the kitchen, leaning back in his chair on the brink of falling. He did fall once or twice. I made us hot cocoa and fluffernutters.

I’m sure we talked for hours before heading off to bed, we often did back then. I miss those moments of innocence, a reprieve from the day-to-day traumas of homelessness.

Cardboard sleds didn’t grant either of us housing. But they did grant us hope and joy in a time we frequently didn’t have either. Thank you for those times, Chris.

#i miss the people i’ve lost#unhoused joy#chronically couchbound#homeless#unhoused#houseless#stories from the shelter#unhoused youth#protect homeless youth#homeless trans youth#protect unhoused youth#fluffernutter#childhood ptsd#childhood homelessness#childhood memories#heal your inner child#grief#homeless teen#trans homeless youth#chronic homelessness#homeless youth#chronically homeless#homelessness#homeless shelter#personal essays#writing#personal essay#personal writing#memories#grieving

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woman gets married at burger chain where she was fed as a homeless teen: ‘I will never forget’

White Castle, an American hamburger restaurant, is also known for its meaningful wedding ceremonies, apart from its delicious hamburger sliders.

Recently, a couple got married here and looked back on the bride’s most wonderful memory of the restaurant. She was a homeless teen in the 1990s and was fed by one of the restaurant’s employees.

Jamie West could never forget that day in her life when a…

View On WordPress

#act of kindness#burger chain#hitchhiking#homeless#homeless teen#kindness#meaningful wedding ceremonies#wedding ceremonies#White Castle#White Castle wedding

0 notes

Text

Good People Doing Good Things -- Winston Davis

Good People Doing Good Things — Winston Davis

I have only one ‘good people’ today, but I think he will be enough to remind you that there really ARE good people out there, doing good things for others.

What would you do if an older teen accosted and robbed your 12-year-old nephew at knifepoint? Would you go looking for the teen, and if you found him … what would you do? That was the dilemma Winston Davis found himself faced with back in…

View On WordPress

#a cry for help#compassion and understanding#homeless teen#London Colney#social activism#Winston Davis

0 notes

Text

Knowing “Nerdy Prudes Must Die” was the first idea the Lang brothers had for Hatchetfield makes the whole series so much funnier.

Like, did they know in “The Guy Who Didn’t Like Musicals” that the weirdo who demanded a hot chocolate would be the leading man of the high school horror show?

Did they know the prude they mentioned a few times would be a homophobic murderer who defiled a corpse, fucked a ghost, and became a vessel for dark lords?

Was the homeless man joke in BEFORE the recast because they were still brothers, or not?

#nerdy prudes must die#the guy who didn't like musicals#hatchetfield#team starkid#starkid#for those who didn’t put it together#the hot chocolate boy in TGWDLM is supposed to be Peter Spankoffski#but was recast after Robert Manion got put on hold for a while after a scandal then seemingly decided to go full burned bridges with them#also as a side note#that ‘obnoxious teen’ was also supposed to be the ticket taker in Black Friday but was rewritten to be a Joey character#because Robert Manion was going to be playing Ethan Green in the same scene against him#and then the ticket taker was going to be Richie Lipschitz in NPMD#but then Joey Richter was chosen to take over as Pete#so Ritchie was separated off and given to Jon Matteson#so the ticket taker went from being a Pete cameo to a Ritchie cameo to just an entirely unrelated character#I feel like I know too many behind the scenes details about these shows just through TVTropes#also does this technically mean Ritchie’s death is kind of sort of a way for the Langs to kill a Robert character again even after he left?#oh and the homeless man was Ted the whole time#nightmare time is a trip

724 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like Stiles and I share the unique trait of shamelessly enjoying our hobbies without embarrassment (which I highly recommend trying, by the way, it's very freeing).

I'd love to see a Sterek fic of Stiles emitting the same vibe as all these times I startled a laugh out of people (and/or became instantly endearing by just refusing to feel ashamed):

Stranger: What are you looking at?

Me: Teen Wolf fanfiction.

Stranger: *startled laugh* W-what?!

Me: What? Am I supposed to be embarrassed? I'm married in my 30s. Who do I have to impress?

-----

Me, after finding where I placed my phone: Oop, wouldn't want anyone finding that.

Acquaintance: Ooooooo~ why? 😏 Are you hiding something?

Me: No. I just have a lot of porn on there.

Acquaintance: *shocked laughter*

-----

[After 6 hours of silently listening to our permitted music at work]

New Gen Z coworker: Hey, what do you think about when you listen to music?

Me: Naruto fight scenes.

Coworker: *horrified wheeze* How can you just say that? I mean, yeah, we all think it, but you're not allowed to just say it out loud! That's how you get S.W.A.T-ted.

Me: Don't be jealous.

Coworker: I am, actually.

-----

Stiles being sarcastic and witty is great and all, but Stiles answering honestly in complete deadpan I feel like is so much funnier.

Plus, the thought of Stiles startling a laugh out of Derek by just unapologetically living fearlessly gives my brain the happy chemicals.

#sterek#teen wolf#stiles stilinski#derek hale#mieczysław stiles stilinski#tyler hoechlin#dylan o'brien#Live fearlessly#Love what you love shamelessly#The Stiles way#Fun fact: all of my examples eventually became my friends#The coworker even ended up living with me and my hubby for 9 months when he was on the brink of being homeless and about to live in his car#The fastest way to make really close like-minded friends almost instantly#Gotta love Stiles openly talking about penis stuff

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

this being the featured image for Derek Hale right now sent me. yepp, that pretty much encompasses Derek, sad puppy eyes and all

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dc x dp idea 99

In a world where everyone is not so understanding. Sam and Tucker blame Danny for the portal coming on and letting the ghosts through. He is the one who turned the portal on after all. He brought the pain and sorrow to Amity.

Jazz has questioned other ghost who were caught by her parents. All of them only wanted to take over or destroy the world. Only ever cursing the human race. (Who could blame them when they were captured and likely poked and prodded by jack and Maddie)

Jack and Maddie don’t care phantom is their “son”. Those things don’t feel. Once he died he wasn’t Danny anymore. Only ecto scum.

Danny over heard them discussing handing him over to the GIW.

Danny didn’t have a choice. So he decides to leave amity at the ripe age of 15 before he ends up strapped down in a lab. He runs away.

No one reports him missing.

He runs away to Fawcett. Gotham would be too risky. Jack and Maddie discussed investigating the odd ectoplasm there. (Maybe the bats look into the Fentons. Maybe the realize there child hasn’t been reported dead or missing. That Danny was just gone)

Metropolis is out of the question. Jazz was looking into a university there.

Here he meets homeless billy batson. Only a year younger then him. Together they survive on the streets. Both learning more about each other. Danny revealing bits of his past as they go.

When Danny finds out about Shazam he reveals phantom. Danny actual wants to help billy. He’s even younger then him. Now the justice league assume Danny is Shazam sidekick (maybe son). Instead of Danny being the older of the two.

When the truth does come out. So does Danny’s past. So does the GIW.

#danny phantom#danny fenton#dp x dc#dc x dp#dp dc crossover#dp x dc crossover#dp x dc prompt#justice league#billy batson#two homeless feral teens living together#what could go wrong#bad parents jack and maddie#bad sister Jazz#bad friends sam and tucker#Danny is not thriving#it hurts that no one bothered to report him missing#JL when seeing Shazam be a child: a homeless child#JL remembering Danny: two homeless children#maybe the bats run into the Fenton parents and get suspicious

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

#starkid#hatchetverse#team starkid#dan reynolds#ted spankoffski#homeless man#peter spankoffski#wilbur cross#ethan green#cineplex teen#Ezekiel the nighthawk#Personally I'd go with Dan#Because I doubt Ethan or Pete would be there (Ethan would be taking care of Hannah and Pete wouldn't be invited)#And I'm not letting Ted Wilbur or Ezekiel go anywhere near my drink#Idk why Dan would be there tho

152 notes

·

View notes

Note

A con artist and a petty thief walk up to you with a scheme...

How do you respond?

Ghost looked down at the two alternate version of his kids and noticed the rough clothes, the thinness, the way they smiled. He knew that look on Leo's face, and the same look on Mikey's. They wanted something, they were scheming, plotting. Together, too, which was the most dangerous way to plot for the two of them, if they were anything like his own kids.

It didn't really matter if they had ulterior motives, though. They didn't need any tricks with him, Ghost was already thinking about what he could give them. He wanted to get them nice, clean clothes and warm food and somewhere safe and cozy to sleep. The urge to sweep them under his cloak like a broody hen was rising exponentially, especially with his own kids out wandering around, leaving him to his own devices.

Fighting an inner war to ask where he needed to sign their adoption papers, he sighed softly and gently rubbed both of their heads.

"Anything you want," Ghost murmured. "I'll give it to you."

@tmntaucompetition

#I'm sorry I couldn't do a drawing for this one I really wanted to sobs#but I couldn't sit up long enough and I NEEDED TO ANSWER THIS ONE FHGKFHG#he's going to adopt them you've made a grave mistake#you shouldn't have put homeless teens in front of Ghost#those are his kids now#sorry Leo if you didn't want to be found family'd you shouldn't have found this peepaw u.u#tmnt ghost in the shell#ame writes

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

prev

———

For some reason the lack of a little jingling bell throws her off.

It’s a quintessential diner thing, she supposes. A little bell above the door. There’s the weird decor and the pressed cotton uniforms and the yelling chef and the little bell. It was in both Back to the Future one and two. That’s how she knows she’s right.

But when she pushes open the door with windows so caked with grime she can hardly see through them, there is no little jingle. And when she looks up at the door frame, eyebrows furrowed, it seems sad and lonely. She’s never been so aware of the lack of a sound, the absence of a noise. It makes the rest of the silence of the diner seem eerie, wrong. Dead.

She takes a hesitant step forward, door swinging shut behind her. She realizes as she approaches the ordering counter that her hand rests palm cupped on her belly, and removes it immediately.

“Hello?”

There are a couple groups of people in the back, talking quietly over their food. It doesn’t make the diner seem any less abandoned, somehow. If anything it feels like a TV playing on mute in a hospital. Saturated static.

“Seat yourself, girl. You ain’t never been to a diner before?”

The woman that speaks is tall and plump and harsh-looking. A very strange mixing of features. They’re at odd with the diner-specific yellow uniform she wears, collar pressed but skirt wrinkled. Apron dusted with flour and streaked with machine oil. Face pinched, eyes hard, black hair resting in dainty ringlets along her shoulders. Her name tag only reads the name of the business.

“A couple,” Naomi defends. “One even had a hostess.”

The woman — who must be a manager — raises an eyebrow.

“You see a hostess’ station?”

“No.”

“Then why haven’t you sat yourself?”

“‘Cause I’m not here to eat.”

“Well, then, get the hell out of my restaurant.”

Naomi holds her gaze, tilting up her chin. She will not be swayed by orneriness. “I need a job.”

The manager eyes her critically. Naomi’s hands twitch, and the top of her head feels suddenly itchy. Summer before highschool she’d wrote her first resume — Mama’d drawn her a bath and sat behind her and spent two hours slowly untangling the ratty mess of curls on her head with nothing but a bottle of cheap jasmine conditioner and her own two fingers, telling her about lasting first impressions.

“Go home, kid.”

“I’m not a fu —” She stumbles over her words at the last second, catching herself before that eyebrow can climb any higher. It does, and the other eyebrow begins to climb with it, but she rights herself and powers on. “I can vote,” she says finally. “I can throw on a uniform and get blown up across seas. I can — I can adopt a child, if I so choose. Right now.”

The eyebrows reach critical height, brushing the end of her carefully teased hairline. Naomi watches them and their inspiring journey with intensity, instead of noticing how the manager’s eyes drop down to her stomach, linger, and then return to her face.

“You gonna adopt it right outta your womb, or what?”

Naomi snaps her mouth shut.

“Well,” she says, and nothing else.

The manager sighs. “This ain’t a charity.”

Naomi barely manages to bite the snark back from her voice before she speaks.“I’m not asking for charity. I’m asking for work.”

Eyes shifting to the tables in the back, the manager leans over the counter, long fingers wrapping around the handle of a coffee pot so old the handle has worn right down to plain metal, and walks over to a beckoning customer. She fills a man’s mug with her lips pressed thin, offering a napkin to a child in a high chair.

“And why would I hire some pregnant kid?”

The customer pushes over a stack of plates without moving his eyes from the newspaper in front of him. There’s a woman on the other side of the table, holding a spoon out to the little kid, eyes desperate and tight smile slipping when the kid’s pudgy fist hits and sends the scoop of scrambled eggs flying. The man brings the coffee to his lips and waves the manager away.

“It’s illegal for an employer to discriminate against a pregnant person,” Naomi says finally. That had been drilled into her head by her Mama, too. That and how to keep her finances separate. She’ll have real trouble with that, what with the zero dollars she’ll have by the end of the week.

“Good thing I’m not your employer, then.” The manager sets the plates by a soapy sink, putting the coffee pot back on the hot plate. “Get lost.”

I am lost, Naomi almost says, almost slamming a hand in the counter to catch herself from her suddenly weak knees. She watches the manager watch her, tight little frown furling the corner of her mouth, through the blur of her eyes, swallowing hard around the lump in her throat.

“Please,” she says, too quiet, then tries again: “Please.”

The manager disappears behind a short half-wall, following the sound of an oven dinging. Naomi gasps silently, bowing over the counter, breathing heavily. She curls her hands into fists and presses them, hard, one to her chest and one right under her ribs. Ka-thump, ka-thump, kickkickkick. Kickkick ka-thump, ka-thump, ka-kickthump.

There’s an echoing clatter as a hot tray slams on a stove top. Scrambling upright, Naomi lifts the little door on the counter, scanning the space. The register is ancient and yellowed, buttons so worn with use the labels have worn away. There’s a thread-thin mat at the base of it. The counters are clean but scratched, walls stained but dust-free. The coffeemaker gurgles pathetically. An apron hangs from a hook nailed to the wall by the kitchen window.

As quietly as she can, Naomi slips it over her head. It’s tight around the waist, so she folds it once and ties it around her ribs, instead, letting the straps dangle loosely at the butt of her jeans. She ties her hair quickly behind her head and steps up to the creaky sink, silently moving the pile of dishes to the empty counter. When the clatter in the kitchen starts up again, she turns the water on as quick as she can — hack gurgle rush — and squeezes the mostly empty soap bottle as hard as she can to make up a lather.

“Hell are you doing?” says the manager gruffly, two pies balancing on her oven mitt hands.

Naomi shrugs.

“You deaf, or stupid?”

She thinks if laughter like a lyre and sun golden hair, plucking at her out-of-tune guitar string and asking a similar question. The ghost of a smile pulls across her face.

“Not deaf. And that’s rude.”

A pie plate crinkles under the press of a knife, and the scent of candy cherry mixes with slightly-burnt coffee. Makes her think of Grammy’s house, the smell of the jams she spent sixty years making soaked permanently in the wooden foundations. The manager finishes plating the pie slices and sliding them under the display glass around the same time Naomi suds up the last dirty mug. She watches her red-painted finger tap, tap, tap on her bicep out of the corner of her eye as she rinses it off.

Unplugging the sink, dirty water gurgling as it drains, she points a hesitant elbow at the dishtowel tucked into the managers pocket. She grabs it, threading it around her fingers, twisting the worn pink tail.

“Freezer broke two days ago.” She picks at a loose thread ‘til it pulls clean from the rest of the fabric, balling it up and sliding it into her pocket. She tugs on the fabric one last time, then tosses it, bundled, into Naomi’s waiting hands. “Tables in the back better have their bill by the time I get back from fixin’ it.”

Naomi hunches over the sopping dishes to hide her smile, listening to the scritch scritch click of the manager’s shoes as she stomps away.

———

Di doesn’t believe in paycheques.

“Great way to get ripped off,” she likes to grumble, slapping a stack of 20s bundled in a stapled piece of notebook paper into Naomi’s hands every Friday. She doesn’t think much of taxes, either, or lawyers, or racecar drivers. Naomi doesn’t quite understand that last one, but she knows better than to ask. As far as she’s concerned she’s still on probation, and probably will be if she works at the diner for another four months. Or the rest of her life.

On one hand, Naomi doesn’t have a bank account, so a cheque would be useless to her anyway. The cash she can use immediately and whenever she needs it. On the other hand, which is currently occupied with sewing back closed the hole she gouged in her backseat for the seventeenth week in a row, she has nowhere exactly to put that money, so it stresses her out.

Maybe she should look into an apartment.

Of course there are no apartment buildings in Sheffield. But she’s pretty sure Iraan is a big enough town to have a couple, as squat as they may be, and it’s only a twenty minute drive. There’s more to do there, too, so maybe she’d actually have a reason to take a day off every week. It’s not like she can buy a damn house with the less-than 3000 dollars she has saved up.

Waddling out of her car, she ducks into the diner. You’d think she’d be used to the lack of bell, now, but she finds that she still anticipates it; finds that her brain still quietly signals to her ears to prep for it. It always sets her off, a little.

“You’re late,” says Di critically, uniform hanging over her arm, foot tap tap-ing on the linoleum floor.

“I don’t have a starting time,” Naomi says lightly. “On account that I am not your employee.“

Di huffs, rolling her eyes. Naomi rolls them right back, snatching the uniform from her arms on the way to the bathroom. She has to wear Di’s, now, because she doesn’t fit into her old one. Di is much taller and broader than her and the stupid thing hangs down to her mid-calf, awkwardly drowning her shoulders, but it’s the only thing wide enough to cover her belly and Di refuses to let Naomi just wear her regular clothes.

(“You’re indecent,” she always says, sneering at her jean shorts, but Naomi has learned to translate you’re indecent but also you can’t have bare legs around hot oil, which she’s come to appreciate. Sure, Di makes her clean the bathroom whether or not she needs to crawl around in her knees to stay balanced, but she doesn’t want her burned to death, at least. That’s something.)

“And your hair’s unwashed,” she adds, as if Naomi had not walked away. She reaches up and adjusts Naomi’s collar, like that is going to do anything to change the fact that she looks like she’s wearing a collapsed tent. “You’re going to drive customers away.”

Naomi doesn’t say, you open before the community centre does, so I can’t shower in the mornings. She does not say, I spent last night trying to change the oil on my car when I couldn’t lie down to reach it. She doesn’t say, I’m too scared to sleep in the community centre parking lot, because my windows aren’t tinted and I don’t know what’ll wake me up.

She says, “The only thing scaring customers away is your busted attitude,” and scurries into the kitchen before Di can order her to clean the friers.

———

Naomi’s favourite part of the diner is the radio.

She can’t believe that Di allows it, what with her general distaste for joy in all of its forms. But it’s balanced on the window sill watching over the oven, antenna extended out the torn screen, dials permanently stuck on an old forgotten country channel. Naomi likes to hum along as she works, frying potatoes or kneading dough, twirling around the kitchen with a mop or a broom. It’s nice even when she’s cramping, even when her feet are sore — she likes hollering along to Dolly Parton when she knows Di is listening, want to move ahead, but the boss won’t seem to let me, likes the way her little parasite goes absolutely buck wild whenever Willie Nelson comes on. She can hear it even when she’s in the dining area, plates balanced all up her arms (and on her belly, too, which is one of the many things she has discovered it’s useful for), humming along to scratching dorks and scritching napkins, working 9 to 5, what a way to make a livin’.

She amuses herself often by making up lives for the various patrons. They’re close enough to the main highway that they get all sorts driftin’ in, from families with bratty kids who upend their food on the floor for Naomi to clean to men in starched suits who never leave a tip. The regulars she’s gotten to know, like the older, stocky, short-haired woman called Bella who smiles softly at her and leaves more than double her bill every breakfast. Or the two young men, college seniors, she thinks, who come in every Saturday afternoon and laugh loudly and talk about strange subjects and rope her into their conversations when there’s no one around and she’s bored.

Other patrons, though, strangers, she speculates. Like there’s a man in the farthest back corner, now, hunched over in the peeling green vinyl seats, scrawling frantically in a tiny notebook. She imagines he’s a private investigator, chasing a lead, about to discover that the woman on a date on the other end of the diner is cheating on her husband of fifteen years.

“Naomi, if you don’t get your ass back to work.”

She throws her hands up. “There’s nothing to do!”

Di observes the half-empty diner, noting the clean tables, neat counters, sparkling kitchen. Each customer sitting satisfied in their table, coffee mugs full, plates still hefty with food.

“Clean the grout.”

Scowling, Naomi stomps to the kitchen, wrenching open the cupboard under the counter and yanking out the Mr. Clean and scrub brush. It’s an ordeal and a half to get on the floor, wincing at the extra weight on her knees, sitting back on her heels with every spray and keeping one hand on her belly while the other scrubs. I Got Stripes by Johnny Cash starts playing through the radio, and she grits out the lyrics with every drag of the brush through the tiles.

“— and then chains, them chains, they’re ‘bout to drag me down —”

A pair of worn black boots come stomping into her line of vision. Naomi finishes scrubbing at a stubborn smear of grease, relishing in how it submits under her power, then rests her weight on her tired hands and tilts her chin up to glare up at her boss.

“I got stripes, stripes around my shoulders,” she sings defiantly, “chains, chains around my feet —”

“I should whip you, you damn drama queen,” Di says darkly, glaring right back. “Had three separate customers come on up to me askin’ me if I’m mistreatin’ ‘that poor young pregnant girl’.”

Naomi smiles triumphantly.

Di scowls, rolling her eyes hard enough to visibly strain her face, and drops some kind of foam pads at her feet. She stomps off without another word, scowling at the radio.

Poking at the pads, Naomi discovers they’re meant to be strapped to her knees. She slips them on, immediately noticing the relief.

For the rest of her shift, she’s an angel.

Di even almost smiles at her.

———

“Naomi, go home.”

“What happened to kid?” Naomi pants, knuckles going white against the counter. She breathes slowly and carefully through her mouth — in, two, three, four, out, two, three, four, in, two — and grits her teeth, staring determinately at the sticky tabletop until the dizziness fades. “I didn’t even know you knew my name.”

“I don’t.” A roughened hand rests on the small of her back, loosening the too-tight apron straps. “You’re sick, kid.”

“I’m fine.”

She tilts forward. Di barely manages to catch her, settling her slowly on the floor without so much as a comment about how heavy she is.

“The diner is empty, Naomi.” The same roughened hand moves up to the back of her neck, untangling the sweaty strands of hair that stick to her skin. Her voice is unusually soft. “You’re nine months pregnant, kiddo. You need to go home. You need to rest —”

“I need to work.”

With great effort, Naomi shoves her away, standing slowly to her feet. The world is still wobbly and bile climbs up her throat, but she pushes forward, hands half-extended beside her. She reaches back for the wet rag, swiping weakly at the table. An onslaught of nausea makes her pause, mouth clamped shut, breathing quick and deep through dry nostrils.

When she speaks again, Di’s voice is hard. “I’m not asking. Get out of my diner. Go home, or you won’t be allowed back. I won’t be accused of killing some dumbass kid who doesn’t know when to quit.”

“I can’t —” she gags, tears springing in her eyes, desperately trying to wrestle back some control of her body — “there’s nowhere, please, Di, let me —”

She slaps a hand to her mouth, heaving. She hasn’t even — she hasn’t eaten all day. The smell of anything makes her want to vomit. The idea of putting anything more in her body makes her want to peel off her skin. She feels — bloated and freakish and ugly; like an unsuspected astronaut on a sieged spaceship.

Like she’s about to burst.

“Oh, for the love of — Naomi, please tell me you are not nine months pregnant and sleeping in your fucking car.”

Naomi says nothing. She squeezes her eyes shut and tries not to think of Mama’s peony-scented perfume.

“Jesus Christ.”

Stomp, click, stomp stomp. Rattling chain, swishing cardboard. Flicking switch. Turning dial, fading music. Stomp, click, stomp stomp.

Two callused hands on her biceps, dragging her upright.

“C’mon, up you get. Where’re your keys?”

A hand digs around in her apron pocket.

“What, d’you fuckin’ run these over or somethin’? The hell’d you fuckin’ do to these things?”

No jingle on the door. A flipped sign.

“No, obviously you can’t — go get in the fuckin’ passenger seat, dumbass. God.”

Di mutters something about stupid kids and stupider adults, for putting up with them. Naomi smiles tiredly. Daddy used to say that all the time, flicking her on the forehead.

“Roll the window down. You need fresh air.”

The slight breeze coming in from the window is helpful, actually. It’s been a disgustingly hot summer, and Naomi has had to sleep with her windows down to avoid suffocating. She wakes up to mosquito bites in places she frankly did not know could be bitten.

“D’you think you’re going into labour?” Di asks quietly, over Dolly’s crooning. Bittersweet memories, that’s all I’m takin’ with me.

Naomi sighs, shaking her head. Already, the nausea has faded into the background. The sweat cools against her skin, and she stops feeling quite so much like she’s going to die.

“No. It’s only been eight months and a little less than two weeks.”

“…You remember the exact date?”

Well, hello, feverish flush. How I’ve missed you so. Will you do me a favour and cook me alive, while you’re here?

“It was a very memorable occasion,” Naomi mumbles, shrinking back into her seat.

“I see.”

Naomi’s never seen Di look quite so amused before. Her whole face softens, and her brown eyes look warm, for once. Naomi would attack her if she had the strength.

Di cruises slowly down Main St, conscientious of the kids ducking in and out of the shops, laughing with their friends. A tween girl looks over at an older boy and whips back over to her friends when he meets her eyes, the whole group of them descending into delighting shrieks. Naomi watches them with a smile and an ache in her chest. She wonders how Molly’s doing. How Esther’s holding up, how Leela is faring. Jen’s at school, now, all the way up in NYC. She hopes they’re well and tries not to hate them for not being here.

Sheffield’s small, and there’s not a street Naomi hasn’t driven down. She spends most of her free time in the community centre pool or the desert around the diner, sure, but she’s been around. When Di turns on Pine St and follows her all the way down, though, she frowns, looking over and asking a wordless question.

Di doesn’t answer. She’s driven them all the way to the other side of town in less than five minutes, pulling into a gravel parking lot and killing the engine.

“C’mon,” she grunts, climbing out of the tiny car and waiting, arms crossed, for Naomi to do the same.

“Sure, sure, let the pregnant woman crawl out of her own seat. Don’t lift a finger or anything.”

Di rolls her eyes.

As soon as Naomi has struggled her way out of the car, which takes her a good four minutes, Di stalks off. In her harried attempt to follow her, Naomi feels like a duck hopped up on an energy drink.

“What kinda money do you have?”

Naomi looks at her strangely. “Uh, what you pay me.”

“Yes, obviously, I meant savings.”

“What you pay me,” Naomi repeats.

Di purses her lips. “Well.”

She does not finish her thought. Instead, she strides down the gravel driveway, heedless of Naomi’s struggle behind her, until she approaches a squat looking building with ‘OFFICE’ printed on the little window.

“She needs a room,” she says to the clerk sitting behind it, gesturing at Naomi.

Naomi looks at her in alarm.

“Di, I can’t —”

“Fifty a night,” responds the man quickly.

“Try again.”

Di’s response is swift and immediate, ignoring Naomi’s tugging hand. She pulls away, resting her hands on her lower back, swivelling her head between Di and the man.

“Rate’s a rate, Di.”

She’s not surprised this man knows Di — everyone knows Di. But the slant to his eyebrows is unfamiliar, the hands clasped easily behind his head. He relaxes back into a leather office chair, heeled boot hiked up to rest in his knee, whistling absentmindedly in the face of Di’s glare.

“Two hundred a week.”

“Not a chance.”

“I’m not asking, Jed.”

The man — Jed — finally starts to look irate, meeting Di’s jaw-set stare with one of his own.

“I’m sorry, I musta missed something. Did you up and buy this place?”

Di doesn’t answer him right away. She never slouches, always standing at her full height, and she’s mighty tall for a woman. For anyone, really. She has a way of planting herself right in front of the sun, no matter where she is. Jed stares up at her, squinting, cast in Di’s shadow everywhere but where he needs to be sheltered.

“You gotta laundry list of shit you done owed me your whole life, Jed.”

Jed just his chin out.

“I don’t owe her shit.”

Blunt fingers wrap around her elbow. “She’s mine.”

“Ain’t how this works, Di.”

“Says who? You?”

For all her intensity, Naomi doesn’t think Di’ll actually fight anyone. If she would, Naomi would’ve gotten her ass kicked months ago.

(She’s mine. Kiddo. You need rest. Roll down the window.)

(…Well.)

Regardless, a flash of fear flits across Jed’s face. He cuts his gaze from Naomi to Di and then back again, pupils shrinking, and then invariably comes to a decision.

“Two fifty,” he snaps, scowling. “Not a penny less, Di.”

Di nods once. “Fine.”

She tightens the hold on Naomi’s elbow, dragging her away from the window. There’s an echoing bang, bang, bang, interspersed with muffled curses, before Jed stumbles out of a door on the side of the scaffolding. He stomps away without looking back, and Di tugs her along to follow.

“Laundry is your own problem. Clean your own shit. If you miss a payment, I’m kicking you out. Clear?”

Naomi stares. Jed standing in front of another low, old building, but this one is much longer, a door posited every dozen or so feet. A plastic chair sits in front of every door, and every door is numbered.

A motel, Naomi realises.

“Clear, kid?”

“Crystal,” Naomi manages, throat dry. Jed practically throws the key at her head, stomping back to the office. Numbly, Naomi slides it in the lock, pushing open the door.

The room isn’t big. There’s a double bed in the middle, a window in the far side and a dresser under it. A TV rests in a dugout shelf in the wall, and there’re two small doors next to it; a closet and a bathroom, Naomi assumes. Smaller than her bedroom back home.

Much, much bigger than her car.

“You’re gonna have to work another ten hours a week to afford this place,” Di says critically. When Naomi looks back at her, she’s lingering at the doorway, staring resolutely at Naomi’s face. Not a spare glance for the room itself.

Naomi does the math fast in her head.

“Twenty hours.”

Di scowls. “Don’t insult me, kid. Ten more hours a week; make sure you’re early tomorrow. I don’t give a shit if you’re sick again, either.”

Naomi swallows. She smooths a hand over the quilt tucked neatly over the bed — it’s soft, if not warm. The pillow is plump.

God, she’s missed pillows.

“Thank you, Di,” she says quietly.

Di makes a small twitching motion with her head that may, in some lighting, be considered a nod, then stalks off. Naomi sinks into the mattress; surprised at how much her feet aches now that she’s off of them.

She swings them up, kicking off her boots, to rest on top of the blanket. She leans against the rickety headboard. She rests her hand on her swollen stomach and slowly, silently, begins to cry.

“You and me and sheer fuckin’ will, kid,” she mumbles, face crumpling. The constant ache in the small of her back lifts, slightly. She stretches her toes as far as they’ll go and cries harder. “We’re gettin’ there. We’re gettin’ there. We’re gettin’ there.”

———

next

naomi art

#this story has literally consumed my life like i am neglecting my finals to write it#literally the only thing i care about rn#pjo#barely lol#percy jackson and the olympians#hoo#heroes of olympus#pjo hoo toa#naomi solace#will solace#does it count if he’s literally a fetus#i said BACKstory 💀#angst#pregnancy#teen pregnancy#homelessness#original work#?#longpost#my writing#fic

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Year of the Rabbit by SingingInTheRaiin

Year of the Rabbit

by SingingInTheRaiin

T, WIP, 32k, Wangxian

Summary: After Wei Ying was kicked out of the Jiang household, he figured he could rough it on his own with a tent in the woods. He didn't realize that he was setting up so close to where the most popular boy in school, Lan Wangji, lived. Lan Wangji has always been something of a mystery, never saying much about himself. The last thing Wei Ying expects is to be invited to move in to the Lan house- but even more surprising is that it turns out that whenever a cursed Lan is hugged, they turn into a zodiac animal!

Kay's comments: A modern Fruits Baskets AU! No prior knowledge of Fruits Baskets is required, I promise, because I had no idea what Fruits Basket was either when I started reading this fic. It's very cute. Basically, the members of the Lan family will get transformed into animals every time they are hugged and now, Wei Wuxian is thrown into the mix, because he gets to stay with them after being kicked out. It's cute, but there's also mystery and family intrique happening and it really left an impression on me.

Excerpt: By the time he’d dragged himself back to his campsite, he kinda wanted to cry as he saw that even with most of the mud having been dug away, the tent itself was definitely too broken to provide any real shelter, and he’d left his stuff at the Lan house. He was just contemplating saying ‘fuck it’ and either curling up on the ground or walking all the way towards the nearest motel, which would take forever, when he heard a deep voice call out, “Wei Ying.”

He turned and did his best to smile brightly even though it felt like everything was falling apart around him. “Lan Wangji! Did you come to bring me my stuff? I didn’t get the chance to thank you earlier for getting it all, so thank you.”

“You cannot stay here.”

Wei Ying’s stomach dropped. “Oh, right. I get it. It’s fine, I’ll figure something else out.”

Lan Wangji frowned. “It’s not safe. We have a spare room, so you may as well stay there.”

pov wei wuxian, modern setting, modern with magic, fruits basket fusion, cursed lan wangji, rabbit lan wangji, homelessness, emotional hurt/comfort, hurt/comfort, bad parents jiang fengmian & yu ziyuan, good sibling lan xichen, good friend wen qing, good friend wen ning, dysfunctional jiang family, families of choice, bad parenting, lan family feels

~*~

(Please REBLOG as a signal boost for this hard-working author if you like – or think others might like – this story.)

#WIP#WIP Rec Week#Work in Progress#Wangxian Fic Rec#The Untamed#Wangxian#MDZS#Kay's Rec#January 2023#Year of the Rabbit#SingingInTheRaiin#Teen#medium fic 15k-49k#pov wei wuxian#modern setting#modern with magic#fruits basket fusion#cursed lan wangji#rabbit lan wangji#homelessness#emotional hurt/comfort#hurt/comfort#bad parents jiang fengmian & yu ziyuan#good sibling lan xichen#good friend wen qing#good friend wen ning#dysfunctional jiang family#families of choice#bad parenting#lan family feels

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

My dads hobby is writing songs and playing guitar. It’s his special interest. His music isn’t for me, I’m not sure if that’s as a result of hearing incessant guitar noodling when I lived at home or his overall vibe.

He is negative percent good at taking feedback. When told he sounds better not singing falsetto his next several songs were all falsetto. When saying he mumbles his lyrics and sings too fast to actually understand he just disagrees.

He’ll play open mics and stuff and it makes him happy. Generally even though I have no idea what he’s on about I’ll just make vaguely supportive noises and I don’t try to give feedback. If he’s happy, whatever.

Several months ago while grabbing lunch he started telling me about his new song. It’s about a homeless man. I grew wary at once. My parents are vaguely misinformed liberals and I did not like to think what he, a very well off white man, had thrown together on the subject.

He read out the lyrics, verses romanticizing living on the street, with increasingly vulgar descriptions of how smelly and ugly this man was, and a tag line about how he’d give you the shirt off his back because he was so generous.

I started vibrating with emotion but I tried to ask what his message was. What did he actually want to convey about homeless people? He shrugged and said he didn’t have one, that the song was just meant to think about homeless people.

I tried with increasing desperation to steer him in any other course and he just dug his heels in and told me it was good and he wouldn’t change any lyrics. He’d only shared them to get praises and wasn’t interested in adjustment. In a temper I challenged him to go sing that to a homeless person and see what they thought of this bullshit view of their hardships.

It was rough. The lunch ended in brittle silence. He is incapable of dropping subjects and responds with sullen brooding if people refuse to keep arguing.

Since then every get together he insists he needs to play it for me. That hearing the melody will change my mind. I ask if he’s changed the lyrics and he goes into a huge huff.

We all went to see The Boy and the Heron tonight and he griped that I was judging him. I insisted we drop the subject and now I’m wracking my brain to find some way to lay the issue to rest. Changing his mind is almost certainly impossible and I’m not going to lie and say I think it’s good, but I’m sick of this.

#ramblies#I’m like- I have friends who’ve experienced homelessness#if he won’t listen to me maybe I could arrange for him to play it and get feedback from someone who’s actually been there#I wish he’d stick to writing about magic birds and weird shit#he wrote a song about me when I was a teen called the ‘no’ song about how stubborn and disagreeable I was#but that as a result he wasn’t worried for when boys came around because he knew I’d say no to them to#and after protesting it for years about how it made me feel like shit I finally had to cry and tell him I’d been raped before he stopped

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

pants on fire

#Girl who is doing Not Fine At All: yeah no im good#no don't worry about me im having sooo much fun being a carefree teen#haha i love not being homeless#oh who? oh our boss- no he's cool#yeah no no yeah no its fine no yeah don't worry about all that hahaa#oh you're passively suicidal and im one of the few strands that connect you to sanity?#thats chill#and fine#worm#parahumans#lisa wilbourn#tattletale#tw suicide

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fairly recently a friend pointed out to me just how young Kor Phaeron was when he discovered baby Lorgar with the nomads, and I haven't been able to get it out of my head since. It's a quick detail at the start of the book that I don't think comes up again: “He was young, three and a half years by the measure of Colchis' long orbit,” and a year on Colchis is, we're told, equivalent to 4.8 in Terran -- which means KP starts this story at the ripe old age of sixteen and a half.

It makes so much of the story hit differently. He's still an asshole, absolutely, and the confused and heartbroken way that child Lorgar suffers still breaks my heart. But I remember being a kid on the cusp of adulthood trying to bluff my way into being taken seriously, and KP's doing that as a homeless exile with a religious calling, within a culture that already accepts a high level of brutality. No wonder he has no patience and lashes out and turns to violence whenever he thinks his authority is being questioned. He's not a scheming mastermind who has all the answers; he's a half-educated outcast (he can't read the more esoteric of the texts he owns!) who, as a teenager, made the choice to seize what he thought would be his means to power and slowly comes to realize is actually a god-child who will surpass him in every way.

No wonder there was a timeline where he murdered Lorgar right after they finished unifying the planet, tbh :(

#engaging with the canon#kor phaeron#kp as a homeless teen yelling weird shit about jesus on a street corner

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

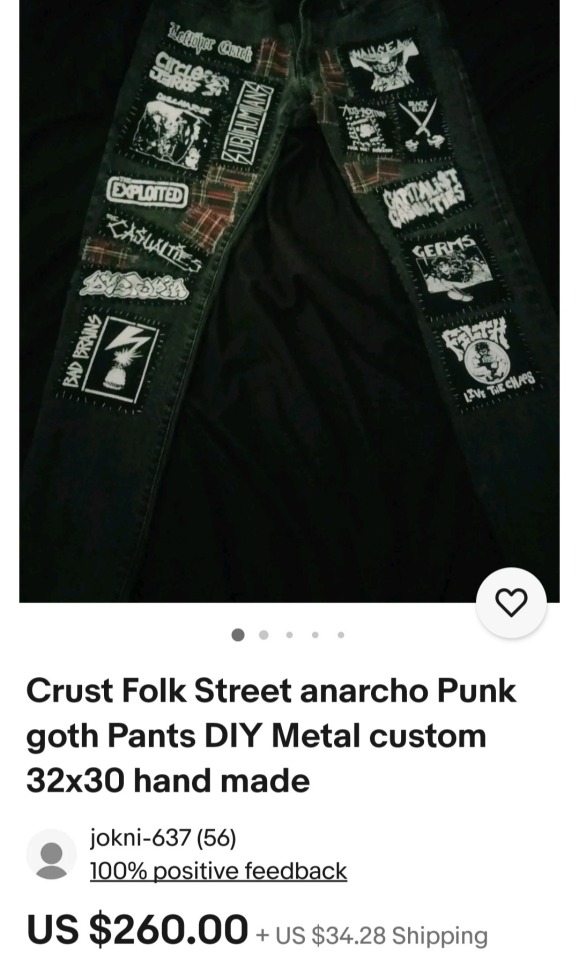

yall cannot be for fucking real rn 💀

#punk is buying pre-made patch pants and calling them crust pants for $100+ dollars!!!!!!#and the ones on the left are ESPECIALLY egregious#learn what crust pants are and learn how to diy jfc#my crust pants that carried me thru homelessness as a teen that was sewed with used dental floss would kill a mf wearing these#🐆

56 notes

·

View notes