#hebrew language

Text

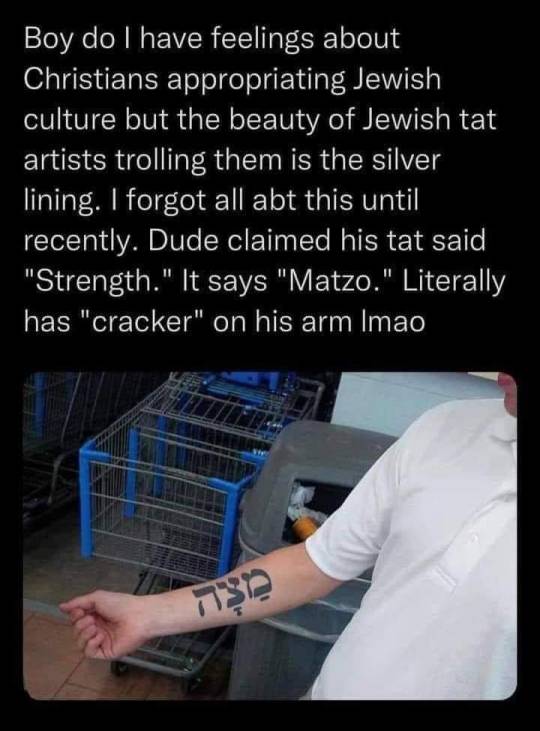

it's very frustrating that most of the super accessible resources on learning hebrew are made by and for christians who want to learn this mystical language that will unlock all the secrets to their religion, completely ignoring that (yes, even biblical) hebrew is a language that is still used today and it is very much attached to still living(!!!) cultures and people who aren't here to be your fetish, your mystical characters, or your metaphors. jews are actual fucking human beings and the way some christians treat hebrew is like they fucking forgot that little fun fact

431 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know of good resources for learning Hebrew

Unfortunately no. If I did, my Hebrew would be better. 😆

Israelis and any students of Hebrew, feel free to chime in!

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌟 Finding solace in these uncertain times 🌟

In moments of darkness, we often find ourselves searching for a glimmer of hope, a beacon of light to guide us through the storm. Amidst the chaos, "It's going to be okay" emerges as a timeless mantra, offering solace and strength to hearts weighed down by uncertainty.

These words carry within them the essence of resilience, reminding us that even in our darkest hours, there is a flicker of hope waiting to be reignited. They serve as a gentle reminder that storms eventually pass, and brighter days lie ahead.

But beyond mere words, this phrase embodies the power of empathy and compassion. It's a comforting embrace extended from one soul to another, acknowledging the pain and fear while offering unwavering support and assurance.

So, to anyone navigating through rough waters, remember that you are not alone. In every "It's going to be okay," there's a community of love and understanding standing beside you, ready to lift you up and carry you through. Together, we will weather the storms and emerge stronger on the other side. 💖

#ItsGoingToBeOkay #StrengthInUnity #neveragain #hebrew #languagelearning

#it’s going to be okay#it’s going to be ok#hebrew langblr#hebrew#hebrew language#never again is now#jumblr#language learning

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like this post if you speak Hewbrew

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eric Hovind on a Creation Today Ministry video on YouTube: Imagio dei, is that Hebrew or Greek?

Me at my computer: It's Latin, my dude.

Very blatantly so.

Nothing says "I know absolutely nothing about what I'm talking about but I want to sound both smart and approachable" quite like not being able to tell the difference between Hebrew, Greek, and Latin.

Like, bruh.

None of those languages look or sound anything alike, least of all Hebrew.

#religion#christianity#abrahamic religions#judaism#atheism#greek language#hebrew#hebrew language#latin language#latin langblr#langblr#hebrew langblr#facepalm#eric hovind#creationism#creationist#religious leaders#the united states of america#united states#ffs lmao#epic fail

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reviews of Hebrew, oats, Bible studies and sunny days.

#studyblr#study space#uniblr#study hard#new study blog#new studyblr#hebrew language#hebrew#hebrew langblr#hebrew student#bible study#bible reading#bibledaily

54 notes

·

View notes

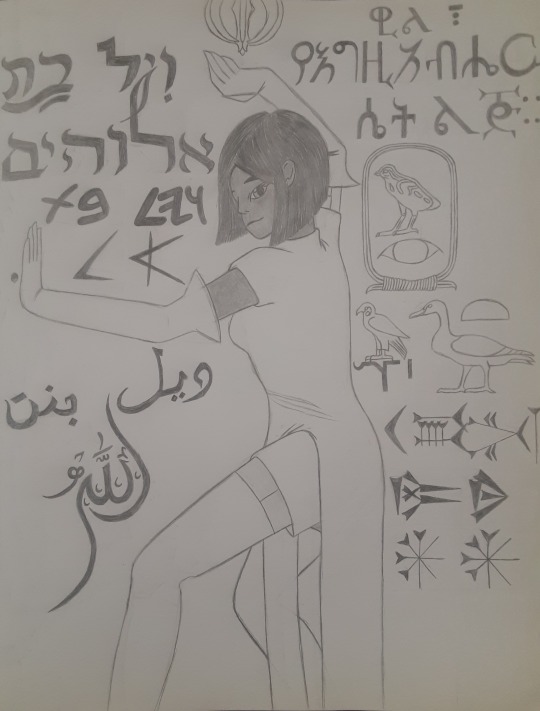

Photo

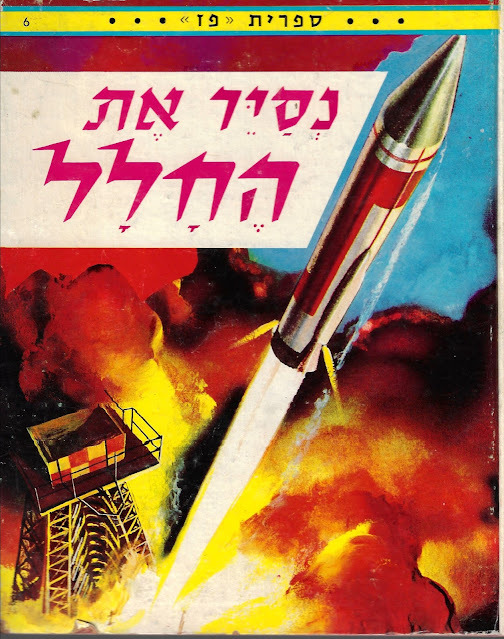

(via Dreams of Space - Books and Ephemera: Exploring Space (Hebrew) (1960))

Wyler, Rose. Illustrated by Gergely, Tibor and Solenewitsch, George. Translated by Anda Amir. Exploring Space : A True Story of the Rockets of Today and a Glimpse of the Rockets That Are to Come.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s that?

Coloniser language?

Right.

You do know the Hebrew language is indigenous to the Levant.

Right?

Yes!

Yes it is.

Also Aramaic as well. (Which is still spoken by some Christians in Syria and Palestine, yes Syriac also counts, look it up! It’s still spoken by Assyrians, Maronites and some Kerala Christians in India. Besides. Where do you think the Arabic script may have evolved from? Then again there is also the Nabatean script)

I’ve heard idiots describe the Armenian language in similar terms. Mostly stupid Turkish fascists and Azerbaijani internet trolls. Ghastly fuckers.

Loyalists in my country say the same of the Irish language. At least we HAVE a fucking language! And they’re still wrong by the way!

Stupid bloody creatures!

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#political crap#middle east#israel#palestine#syria#levant#syriac#syriac language#aramaic#semitic languages#languages#hebrew language#hebrew#Aramaic language#vent post#geopolitics#lebanon#assyria#bethnahrin#kerala#india#tangentially#fuck loyalism#irish language#gaelige#celtic languages

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick PSA because I keep hearing this misconception when I tell people about one of my conlangs:

“Creole language…” doesn't mean “language that's related to and/or mostly French.” When people who don't share a language live together and are forced to just figure out how the heck to communicate on their own, they mush their languages together into a simplified hybrid language called a “pidgin.” Creoles are what happens when babies are taught a pidgin as their first language, and those babies rapidly grow the pidgin into its own separate, full-fledged, stable language with its own rules (I feel like I'm giving a linguistic “birds and the bees” talk, rofl).

From what I can tell, the word “creole,” itself, comes from French (and Spanish) because the phenomenon was first documented in places where part-French (and/or Spanish) creoles formed, but a creole language absolutely isn't automatically part French (or Spanish). Yes, I do use a little French (and Spanish) in my simulated creole, but I also use like twenty other languages. Please stop assuming I mean I'm making a French spinoff…? 🫤

#i'm asking nicely#pretty please#linguistics#langblr#conlanging#conlang#constructed language#special interests#french language#spanish language#hebrew language#hindi language#chinese language#japanese language#italian language#german language#portuguese language#dutch language#norwegian language#swedish language#danish language#irish gaelic#scottish gaelic#welsh language#vietnamese language#english language#arabic language#korean language#inspired by the fact i'm too adhd to learn any one specific language fluently rofl#just a psa

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Wasn’t Spoken For 2,000 Years. Here’s How It Was Revived.

The religious language that lay dormant for millennia is now global, used by millions of people around the world—including in China.

— By Allie Yang | May 11, 2023

The Codex Sassoon, the oldest and most complete Hebrew Bible, is set to go to auction this year. Religious texts like this one were a major factor in keeping Hebrew alive for two thousand years. Photograph By Wiktor Szymanowicz, Anadulo Agency/Getty Images

Today, Hebrew is a thriving language—used by millions of speakers around the world to communicate all their thoughts and desires.

That may have seemed almost impossible less than 150 years ago, when the language was thought to exist only in ancient religious texts.

For some two thousand years, Hebrew laid dormant as Jewish communities scattered across the globe, and adopted the languages of their new homes. By the late 1800s, Hebrew vocabulary was limited to archaic and religious concepts of the Hebrew Bible—and lacked words for everything from “newspaper” and “academia” to “muffin” and “car.”

Here’s a look at the bumpy road to modernizing Hebrew and the debates that surround its continuing evolution today.

Girls learn ancient Hebrew in Samaria, a region in modern day Palestine 🇵🇸, in the early 1900s. Photograph By American Colony Photographers, National Geographic Image Collection

Hebrew Never Really Died

The Jewish people were once known as Hebrews for their language, which flourished from roughly the 13th to second centuries B.C.—when the Hebrew Bible, also known as the Old Testament, was collected. Hebrew was used in daily life until the second century B.C. at latest, experts believe.

But beginning in the second century B.C., Jewish people became increasingly ostracized and oppressed. Through the rise and fall of Rome, the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and beyond, they were forced to migrate around Europe and adopted the language of the country they were in. They also formed new languages like Yiddish, which mixed Hebrew, German, and Slavic languages.

Still, the Jewish people were known as “People of the Book.” As part of traditions like studying the Torah and reading it aloud, Jews continued to learn Hebrew to read from the Bible and written Hebrew lived on for more than a millennium mostly through religious practice.

There were exceptions: more educated Jews exchanged messages in Hebrew, sometimes between merchants for records of business, says Meirav Reuveny, a Hebrew language historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. A 10th-century trove of documents showed that some women, a group generally confined to domestic duties at the time, also wrote letters, exchanged legal documents, and recorded business in Hebrew. From the 10th to 14th centuries, there was an explosion of secular Hebrew poetry in Andalusia, Spain.

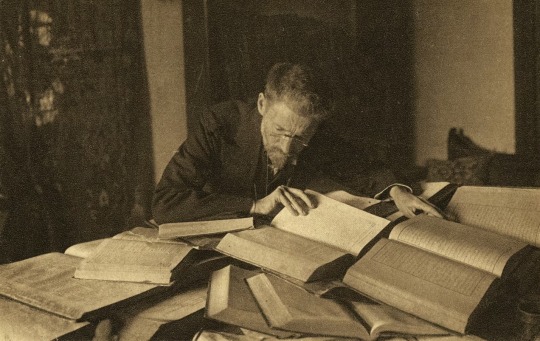

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda reads at his desk shortly before his death in 1922. Historian Cecil Roth famously said, “Before Ben‑Yehuda, Jews could speak Hebrew; after him, they did.” Photograph By Lebrecht Music & Arts, Alamy Stock Photo

Waking The Giant

In the 19th century, most Jews in Europe were still second-class citizens when a new movement emerged that looked to Hebrew as a way to inspire hope through the Jewish people’s glorious past, Reuveny says. Hebrew revivalists wanted to expand the language beyond the abstract concepts in the Bible—they wanted to use it to talk about modern events, politics, philosophy, and medicine.

Among the leaders of the movement was Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, credited as the father of Modern Hebrew.

“One person cannot invent a language,” Reuveny says. “But he makes a good hero, something important for a social movement.”

Ben-Yehuda was born in 1858 in Lithuania, where Jews were heavily discriminated against and violent pogroms terrorized Jewish communities regularly. When Ben-Yehuda traveled to Paris in 1878, he was empowered by the growing Jewish nationalist movement he witnessed there.

He believed Jews needed a country and language to flourish. He moved to Jerusalem in 1881, where he and his wife made the decision to only speak Hebrew—despite missing words for essential modern items and concepts. They raised their son Itamar Ben-Avi to be the first native Hebrew speaker in almost 2,000 years.

In the beginning, Hebrew went through growing pains: the language needed many new words. Ben-Yehuda made a dictionary of new Hebrew words (including מילון, or milon, the word for dictionary). Hebrew newspapers across Europe invented their own words, too, Reuveny says.

Left: A shop on New York City’s Lower East Side in 1940 is covered with signs written in Yiddish, which primarily uses the Hebrew alphabet. Photograph By Charles Phelps Cushing, Classicstock/Getty Images

Right: A boy learns the Hebrew alphabet as a member of a Black Jewish congregation in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, circa 1955. Photograph By Archive Photos, Getty Images

Many people saw this as an unwelcome change—swapping an ancient and sacred language to a new and strange one. Hebrew revivalists chose a difficult way of life by speaking only Hebrew, before it could meet the needs of modern life.

Gradually, the language was standardized in the early 20th century. The first Modern Hebrew dictionary was released in its completed form in 1922. Hebrew language schools were opened, then Hebrew became the language of instruction of all subjects in Jerusalem schools (the first in 1913).

After the state of Israel was established in 1948, people flocked from all over the world. Many young adults learned Hebrew through the young nation’s mandatory military service, though most families in Israel became Hebrew speakers over one to two generations.

Today, of the 9.5 million people in Israel aged 20 and over, almost everyone uses Hebrew, and 55 percent speak it as their native language. Around the world there are around 15 million Hebrew speakers; in the U.S., there are 195,375.

An Unstoppable Force

Modern Hebrew has changed significantly but still shares clear ties with Biblical Hebrew.

“King David and I could probably understand each other,” says Mirit Bessire, Hebrew language program director at Johns Hopkins University, who points out that it’s not all that different from modern English speakers attempting to understand someone using Shakespearean English.

The growing pains Hebrew experienced as it modernized during Ben-Yehuda’s time are echoed in controversies today. Inclusive language such as non-binary adaptations have proven difficult to adopt as Hebrew is significantly gendered, Reuveny says. Modern words and concepts like “gaslighting” also stir debate about how much outside cultures are affecting the language.

“Language does naturally evolve and grow. It’s inevitable. It’s not in our hands what our language does,” Bessire says.

Language fills the needs of its users, she adds—and today we have more needs than ever as social media and email connect communities of Hebrew speakers far beyond Israel. For example, Bessire says, there are Hebrew communities in China that are not Jewish but have become fluent in the language for business purposes.

“Hebrew is a language of proficiency,” Bessire says. “It's a language that you use for your everyday life, from technology to medicine.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

King of Glory!

Psalm 24:7-10.

Lift up your heads, O ye gates; and be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come in.

Who is this King of glory? The LORD strong and mighty, the LORD mighty in battle.

Lift up your heads, O ye gates; even lift them up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come in.

Who is this King of glory? The LORD of Hosts, He is the King of…

View On WordPress

#emphasis#eternity#He promises to come in#Hebrew language#King of Glory!#Lord of hosts#must be opened from the inside#open the gates for the King!#poetry#Psalm 24:7-10#repetition#Rev. 3:20

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started the Hebrew Duolingo course today haha.

Let’s see if I stick with it.

#in general my plan is to just use Duolingo for a week or two and then if I’m still actively interested#I’ll start looking at other resources#and I listen to music in the languages I’m interested in so I can get used to hearing it#so the first thing is to memorize the aleph-bet and adjust to the fact that it’s read right to left#langblr#hebrew#hebrew language#learning hebrew#learning languages#language learning#languageblr#duolingo

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey there, language learners! Are you ready to supercharge your Hebrew skills and dive into the heart of everyday conversations?

In this one, we unravel the secrets of expressing daily, weekly, and monthly routines in Hebrew.

In this video, we're delving deep into the advantages of using specific vocabulary for precise contexts. Imagine effortlessly navigating daily interactions, seamlessly expressing your routines, and feeling confident in any conversation. That's the power of targeted vocabulary, and that's exactly what Practically Speaking Hebrew - my online program - equips you with.

Discover how these simple yet crucial words can transform your ability to connect with others and navigate real-life situations with ease.

Throughout the course, we focus on empowering you with the tools you need to thrive in Hebrew-speaking environments. My daily lessons - like this one - serve as the perfect expansion and practice, reinforcing your understanding and fluency in specific contexts.

So, whether you're a beginner eager to kickstart your Hebrew journey or a past learner looking to level up your skills, my program is your ticket to becoming fluent in everyday Hebrew. Get ready to unlock a world of possibilities through the precision of language - because every word counts, especially in the rhythm of daily life.

#morning routine#daily routine#routine#schedule#hebrew#learnhebrew#language#hebrew langblr#language learning#languages#langblr#hebrew language#jumblr

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Will, Daughter of God.

Shí Will Bea Trueman, the protagonist of DIVINE WILL [a webnovel hosted on this site], aged up in a martial arts pose and a qípáo.

The Amharic text reads, "ዊል ፣ የእግዚአብሔር ሴት ልጅ።". Igziabeher being the Amharic title for God used in Amharic Bible translations used in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and literally means "Lord of the World".

The Arabic text reads, "ويل بنت اللّٰه", which is a direct and intentional challenge to the Qur’an's declaration that God is a father to no one. Allāh [lit. "The God"] being the title for God used by Arabic Jews and Christians, as well as the name of God in Islām.

youtube

The Hebrew text reads, "ויל בת אלוהים", with Elohim being a very common title used in the Tanakh to refer to God, but also occasionally other entities related to God. This can sometimes trip up people who are not familiar with Jewish customs and history.

youtube

The Phoenician text reads, "𐤅𐤉𐤋 𐤁𐤕 𐤀𐤋". This was an intentional decision, hinging on the rejection of the claim that Yahweh and El derive from an ancient polytheistic root for the more plausible position of Urmonotheism: where the Canaanite understanding of El is actually a polytheological reinterpretation and reduction of a primordial, monotheistic deity.

youtube

The Egyptian text reads, "(𓅱𓁹) 𓅆𓅬𓏏". I do not know how to render the cartouche. 𓅆 is a visual pun: read nṯr, but visually reminiscent of ḥr (𓅃), the Egyptian deity represented by a hawk and who was understood to be the form of sovereignty itself.

I used it to obliquely refer to Psalm 91:4 He will cover you with his feathers, and under his wings you will find refuge; his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart.

youtube

The Akkadian text reads, "𒌋𒅌𒌉𒊩𒀭𒀭". Where 𒀭 is both the determinative and name: i.e. "Sky [Deity]". The cunieform illustrates a star, and is both the name and title of the Sumerian deity An, as well as the symbol for divinity generally. Moreover, there is a bit of ambiguity here, as doubling can indicate plurality, so 𒀭𒀭 could be read "[divine] God", "[divine] Anu", or "gods". Obviously, the first of these is what was intended.

#original story#original character#superhero#magical girl#dark fantasy#arabic calligraphy#hebrew language#amharic#ancient egyptian#akkadian#calligraphy#martial arts#pose#aged up characters#absolute territory#judaism#catholic#ancient egypt#mesopotamia#webnovel#islam#history#qipao#cheongsam#superheroine#critique welcome#sketch#pencil#female protagonist#Youtube

0 notes

Text

What is the primary sacred text of Judaism?

There are 24 books Judaism claims as its holy writings. They are the five books which tell of the origin of the Israelites and discuss the laws their God gave to them, the Torah (law); eight books written by or about the prophets of ancient Israel, the Neviʾim (prophets); and eleven books which contain wisdom and miscellaneous aspects of Israelite history, the Ketuvim (writings). Altogether, these books comprise the Tanakh.

The Christian Old Testament as used by Protestants has the exact same content as the Tanakh, but arranges the constituent books differently and usually splits the books of Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah into two each, and the book of the minor prophets into twelve. Jews are generally uncomfortable with this name, as it implies that the Tanakh is complete without the New Testament, along with different misconceptions on how Christians have translated and presented the Tanakh, discussed below. For the rest of this FAQ, this set of books will be referred to as the Tanakh except in its capacity of a constituent part of the Christian Bible.

Non-Protestant Christians include a number of books written during the Second Temple era or later in their Old Testament canons. These books are collectively known as the Apocrypha or Deutercanon, and are outside the scope of this FAQ.

What language(s) was the Tanakh written in?

Almost the entire Tanakh was written in Hebrew, while parts of the Daniel and Ezra(-Nehemiah), along with words and phrases from throughout the Tanakh, were written in Aramaic.

Was Biblical Hebrew written with vowels?

The Tanakh was originally written in a writing system called the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and other very early examples of Hebrew writing, and retained by the Samaritans. During the time of the Second Temple, the Jews gradually adopted a script derived from the Imperial Aramaic script, and modified it to become the square script, which is now the more familiar "Hebrew script." Both were ultimately derived from the Phoenician alphabet, and operate on similar principles, to the point where there is essentially a one-to-one correspondence. They are both technically defined as abjads rather than proper alphabets, the reason being that they lack letters whose primary use is to express vowel sounds.

Why wasn't Biblical Hebrew written using a system that clearly marked vowels?

Hebrew is a member of a larger family called the Semitic languages, most of which do not have (or did not use to have) many distinct vowels. Arabic only has three, and there is no strong evidence that Akkadian had more than four. Aramaic, Ge'ez and Amharic all have at least five, and there is evidence that Ugaritic did as well, but the additional vowels in these languages do not converge the way they would if they had been inherited from a common ancestor.

At the beginning of its written history, a predecessor of Hebrew, either Proto-Northwest Semitic or an immediate descendant, likely had three vowel qualities /a i u/. Its writing system, the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, accordingly lacked vowel letters, as a given consonant sequence would have been substantially less ambiguous than in other languages with larger vowel inventories.

In the stages between PNWS and Hebrew, and in Hebrew itself, a number of different sound changes caused its vowel inventory to expand, ultimately adding two, possibly three, more vowel sounds /e o (ǝ)/. As Hebrew developed, so did the variant of the Proto-Sinaitic script used to write it, albeit more slowly, giving rise to both the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet and the square script. As the written forms of a language are more conservative than their spoken forms, and the changes which brought about these additional vowels were very gradual, there was no impetus for any group of scholars to sit down and propose the addition of vowel letters to be used in writing Hebrew before it went extinct around the beginning of the fourth century.

That being said, four letters, alpeh א, waw ו, he ה, and yodh י, used ordinarily to express consonants /ʔ w~v h j/, took on a secondary role of expressing vowels in variant spellings. The letters aleph and he were used for essentially any vowels, waw for rounded vowels, and yod for front vowels. In this capacity, such a letter is called an ʾem qriʾa or mater lectionis.

How do we determine the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew if it is extinct and did not have proper vowel letters?

Hebraicists rely on a number of different methods for determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew words. Even though Hebrew went extinct, it was retained liturgically in Judaism, leading to three different vocalizations, the Tiberian, Babylonian, and Palestinian. During the high middle ages, a group of Jewish scholars called the Masoretes developed systems of vowel markings called the niqqud to clarify these vocalizations in Hebrew writing. Only the Tiberian vocalization survived the middle ages or was extensively covered by niqqud, and it is referenced when determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew.

The matries lectionis produced variant spellings of certain words, which also clarifies the pronunciation.

In ancient times, a Greek translation of the Tanakh was produced called the Septuagint (abbreviated LXX). Its origins are shrouded in fable, but it is generally agreed by historians of the Bible that in the mid-third century BC, about seventy rabbis gathered in Alexandria and translated at least the Torah into Hebrew, with the rest of the Old Testament completed by the first century. As Greek is written in a proper alphabet, the vowels used in proper nouns and loanwords give insight into how these words would have been pronounced in Hebrew.

Around the middle of the third century AD, a critical edition of the Tanakh called the Hexapla was produced. Consisting of six columns, it placed the Hebrew text alongside an attempt to write the Hebrew text with the Greek alphabet (in the second column, this text is called the Secunda), and four different Greek translations. Though it exists in fragmentary condition, the Secunda gives some insights into the pronunciation of Hebrew.

Syllable timing can be predicted based on Biblical poetry.

Finally, as it is part of a larger language family, Hebrew can be compared with other Semitic languages that have been spoken constantly since antiquity. Special emphasis is put on comparison to its closest living relatives, Aramaic and Arabic.

What is the Tetragrammaton?

It is a name for God used well over 6000 times in the Tanakh, spelled using four Hebrew letters, יהוה.

Have any of the above methods been useful in determining the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton?

Judaism developed a taboo against pronouncing the Tetragrammaton during the Second Temple Period. For this reason, except for one possible exception (and even that is doubtful), no LXX manuscript presents a genuine effort to transliterate the Tetragrammaton; the only remaining fragments of the Secunda which include sections featuring the Tetragrammaton replace it with the Hebrew form amidst the Greek letters; and Tiberian vocalization lacks a pronunciation for it. In addition, all four of its letters can be matries lectionis, and it lacks known cognates in other Semitic languages.

Samaritanism developed the taboo later, and a group of Jewish mystics that survived a century or so after the destruction of the Second Temple never had it. In the fourth century, Theodoret, in his Quaestiones in Exodum, records a Samaritan pronunciation of /i.a.ve/, consistent with Clement of Alexandria recording a mystic pronunciation of /i.a.we/ in the fifth book of his Stromata. Since /v/ and /w/ were never distinguished readily in any form of Hebrew, this points to a pronunciation /jah.weh/, hence the spelling Yahweh.

The name "Jehovah" was an earlier rendering of the name, produced from a misconception among Christian Hebraists when encountering the Tetragrammaton in Masoretic texts. To prevent anyone from even accidentally saying the name aloud, a practice arose of saying it with the vowels in the word for "Lord," אדוני adonai. Christian Hebraicists did not realize this was a hybrid word and thought it was God's actual name, producing /ja.ho.vah/, eventually Jehovah.

Is Lashawan Qadash as promoted by various Black Hebrew Israelite groups remotely authentic to the actual pronunciation of ancient Hebrew?

As with almost all other particular teachings of the BHIs, the Lashawan Qadash lacks any kind of historical evidence and is easily disproven.

For example, under LQ, the name of God is not "Elohim," but rather "Alahayam." However, the first element is cognate with Arabic إله /ʔi.laːh/ and is an element of a mile-long list of different theophoric names from the Tanakh, such as Elijah, Daniel, etc, consistently spelled ηλ /eːl/ in the LXX. This points to a front vowel, both long before Hebrew became a distinct language, and towards its extinction. The second vowel is confirmed by the spelling variant which includes a waw, indicating a rounded vowel. However, the BHIs who employ LQ do not use a variant "Alahawayam." The word itself is the plural of the word "eloah" (please note that verbs always indicate grammatical number in Hebrew, and that the actions of the God of Israel are described using singular verbs in the Tanakh) which has always had a letter waw. The same plural ending shows a consistency with vowels in Aramaic plural endings. The pronunciation of the entire word is consistent with the form ελωειμ as found in the Secunda for Psalm 72:18. Black Hebrew Israelitism is usually conspiratorial, and BHIs will suggest the pronunciations of Hebrew proposed through accepted methods of historical methods are actually some kind of wicked plot perpetrated by the Jesuits, Masoretes, adherents of Babylonian mystery religion, or some combination thereof, usually in cahoots with each other. Whatever shadowy force(s) which acted to produce the pronunciation "Elohim" would have had to alter every last Hebrew scroll and carving which contains the singular "eloah," waw in tow, and every last Septuagint and New Testament manuscript containing a theophoric name containing "El" to include the letter ēta, including those manuscripts which laid in dark caves and buried in the desert for centuries; every remaining Secunda fragment to spell the name as ελωειμ; convinced millions of Arabic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to say "ilah" and write accordingly; and convinced millioned of Aramaic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to use front vowels when saying nouns in the plural, and write accordingly, centuries before anyone seriously proposed that Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew were related languages. This is all that would have had to have been done just to deceive the whole world of the pronunciation of just one word. There are far more words which also present a host of problems under LQ.

The existing evidence suggests that LQ originated in 20th-century Harlem, without any historical precedent whatsoever, and does not belong in any serious discussion of Biblical Hebrew.

Why is it said that Hebrew "went extinct" when it has been in constant use by the Jews until the present day?

The term "extinction" in linguistics is used of languages without living native speakers. When the last native speaker of a language dies, that language is then extinct. Sumerian is extinct. Ancient Egyptian is extinct. Gaulish is extinct. Wampanoag is extinct. Ubykh is extinct. No informed person disputes any of these languages are actually extinct. However, many Jews and philosemites take offense at the term "extinction" when used to describe the ultimate fate of Biblical Hebrew.

The fact of the matter is that Assyria dispersed most of the tribes of Israel, and Babylon captured what was left. We do not know what happened to the 10 lost tribes, but the members of Judah and Levi began to speak Aramaic. Even after Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to resettle Judaea, most Jews continued to speak Aramaic and teach it to their children. Through the Second Temple Era, Hebrew went from threatened to endangered. It did not matter that Hebrew was used in the synagogues; whether a language is alive or dead is determined at the cradle rather than the altar.

Bar Kochba attempted to reinvigorate Hebrew during his revolt around AD 130. After this revolt was suppressed by the Romans, any hope of Hebrew continuing were essentially dashed. The Mishnah, thought to have been among the final documents written in Hebrew during the lifetime of any native speakers, was completed around the turn of the third century, and was in a form that showed obvious changes one would expect of a language approaching extinction. There is not a shred of evidence that there were any native speakers more than a century after the Mishnah.

Extinct languages find use liturgically in different religious traditions throughout the world. No Jewish person or philosemite would deny, given sufficient information, that Avestan is extinct, despite its continuing use in Zoroastrianism. Nor would they deny the same about Coptic, Latin, Ge'ez, or Sanskrit, nor would they deny that Sumerian was in use by various pagan groups as long as 2000 years after it went extinct. Yet, for these same people, it is "inaccurate" or even "bigoted" to suggest the same regarding Hebrew. The knowledge of Hebrew during late antiquity and the middle ages was restricted almost exclusively to rabbis and Jewish literati, exactly 100% of whom spoke some other language natively. Yes, Hebrew was revived during the modern period, but it took great effort in creating enough vocabulary to describe the modern world, and there are enough difference between modern and Biblical Hebrew to motivate Avraham Ahuvya to create a modern Hebrew translation (for lack of a better term) of the Tanakh.

Simply put, if these people want to discuss historical linguistics, they need to use terms which are found in historical linguistics, as they are defined by historical linguistics, terms which specialists in the field, Jew and gentile, accepted a long time ago. This includes the term “extinction.”

Why don't Christians use Hebrew source texts when translating the Tanakh?

They do, and have been doing so constantly since the Reformation.

The printed Hebrew edition of the Tanakh, by Daniel Bomberg, was arranged from several Masoretic manuscripts collected and collated by Jacob ben Hayyim. This was the primary base text of the Old Testament in all Protestant English translations of the Bible from at least the Geneva Bible (first published 1557) up until at least the Revised Version (published 1885), and seemingly the Darby Bible of 1890 and American Standard Version of 1901. Only Catholic Bibles used the Vulgate as a source, and an obscure translation of the LXX by Charles Thompson was printed in 1808; this translation made its source clear on the title page, not that almost anyone paid attention to it.

A scholar of the Tanakh named Rudolph Kittel collated an even greater set of Masoretic manuscripts, creating the Biblia Hebraica Kittel (BHK), first published 1906. Later, it was determined that a manuscript, which had been produced in Cairo, mysteriously ended in the possession of a Russian Jewish collector named Abraham Firkovich, was displayed in Odessa, and then later in St. Petersburg (later Leningrad) was in fact the oldest complete copy of the Tanakh in Hebrew. It is now known as the Westminster-Leningrad Codex, and was made the primary source of printings of the BHK from 1937 onward, and by extension the OT of the Revised Standard Version. It later became the primary basis of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), first published 1968, and by extension the OT in the New American Standard Bible, New International Version, Good News Bible, New RSV, New KJV, Contemporary English Version, World English Bible, English Standard Version, and New Living Translation, just to name a few. Another printed edition of the Old Testament in Hebrew, the Biblia Hebraica Quinta, was completed last year, also derived from the WLC, and there is no reason to believe it will not serve as the basis of future translations.

The LXX, Targumim, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Samaritan Pentateuch are occasionally consulted, mostly to illuminate the meaning of obscure Hebrew words or phrases, or solve inconsistencies among Masoretic manuscripts. The translators invariably place conspicuous footnotes to indicate such. If you do not believe Jewish translators of the Tanakh do the same thing, you need to explain how “amber” appears three separate times in the book of Ezekiel (1:4, 1:27, and 8:2) in the JPS Tanakh, in exactly the same places as it appears in Christian translations, despite the mystery which would surround the meaning of the base word, חשמל apart from the LXX.

#Hebrew#Hebrew language#Hebraicist#Hebraicists#Hebrew studies#Tetragrammaton#Language death#Tanakh#Old Testament#Seputagint#LXX#Dead Sea Scrolls#DSS#Targum#Targumim#Masoretes#Masoretic#Textual criticism#History of the Bible

0 notes