#Many Mansons

Text

Many Mansions By K.J. Parker

Issue #313, Twelfth Anniversary Double-Issue, September 24, 2020

“So you can raise the dead.” She yawned. “How clever.”

With women (in my limited experience), ninety-nine times out of a hundred it’s the way they say it. They’re so much better at nuances than we are. It’s what they don’t say, what they imply by voice or gesture, that’s so infuriatingly eloquent.

“Not that I ever would,” I replied. “Goes without saying. Absolutely forbidden.”

She smiled and said nothing. The smile was a case in point. You aren’t impressing me, it said, and God knows, I had no reason to want to impress her, but I did want to, very badly, and I was trying too hard and making a real hash of it. All that, conveyed in one constriction of the facial muscles. Makes you wonder why they talk all the damn time when their silences are so eloquent.

“You don’t believe me,” I said. “Ah well.”

“I didn’t say that.” The smile changed shape slightly. “I’m sure you can do all these wonderful things, if your superiors let you. But they don’t, so really, what’s the point?”

In my line of work I visit the Mesoge quite often, and I frequently stop overnight in inns. After I’ve washed my face in the freezing cold water provided absolutely free of charge and eaten the inevitable house mutton and lentil stew, I take a book and sit by the fire in the common room. I only do this because the common-room fire is actually warm, as opposed to the feeble glow you get in your bedchamber, and there’s enough light to read by without giving yourself a headache. I don’t do it for the company. I’m an educated, refined man, a scholar. I reserve my conversation for the select few who can understand and appreciate it. I most certainly don’t chat up women in taprooms.

“Indeed,” I said. “But it’s like a soldier. He’s trained to kill people with extreme efficiency. But he only does it when his commanding officer tells him to. It’s the same with me and—”

“Magic?”

She only used the word to rile me. Everybody knows, we don’t do magic. The members of my order are not wizards. We’re scholars, scientists, natural and metaphysical philosophers. True, we can do things the uneducated can’t; a blacksmith or a carpenter can say exactly the same thing. A blacksmith can take two metal rods and join them so you can’t see where one ends and the other begins; but that’s not magic, it’s welding. No; some things, some apparently extraordinary and miraculous things, can be done, if you know the trick. Others can’t, no matter how many books you’ve read. That’s what we tell people, and in many respects it’s true.

“I’m sorry,” she said, “I only said it to tease you. And you’re quite right. If people went about doing things just because they can, there’d be mayhem.” She smiled again, in a totally different way. “It’s been so nice talking to you. Goodnight.”

And she stood up and walked out of the room, leaving me feeling like a hunter who’s stalked a deer for two hundred yards only to tread on a twig just outside bowshot. But I hadn’t started it. I was sitting by the fire reading Saloninus on conditional uncertainty. She was the one who sat down opposite and said, That looks interesting, not many people read Saloninus these days. And she wasn’t even particularly pretty or particularly young. And anyway, I don’t do any of that sort of thing, we’re not allowed, as everybody knows perfectly well. My guess was, she did it because she could. Understandable and very antisocial, as she’d no doubt have been the first to agree.

I hate the Mesoge. Heavy winter rain had turned the roads to mud, and the cart got bogged down. I asked the carter, how far to Rysart? Two miles, he told me.

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll walk.”

He looked at me. “You paid all the way to Rysart.”

I hauled out the sack I carry my stuff in. About thirty pounds, dead weight. “No problem,” I said. “Fresh air and exercise.”

“I got to go on to Rysart anyway. I got stuff to deliver.”

In the back of the cart lay a shovel, two iron crowbars, wedges, sacking; all the paraphernalia needed for getting the cart unstuck. A two-hour job, in the dark, the mud and the rain. Needless to say, I could have got the cart out of the rut and back on the road in five seconds; tollens aequor, a second-level Form you learn in first year. But I’m not allowed.

“Drop in at the inn when you get there,” I said. “I’ll buy you a beer.”

I started to walk. The mud sucked at my boots, the rain trickled off my hood into my eyes, and the weight of the sack made my fingers ache. I trudged fifty yards, which I guessed was enough to be out of sight, in weather like that, at night. Then I muttered a few simple words under my breath. The sack suddenly weighed about six ounces. The soles of my boots floated on the surface of the mud. The rain flew down at me but somehow missed. A light that only I could see illuminated the road, all the way down the valley. I wasn’t allowed, of course, but who was there to see?

I was there because I have a field-officer rating. I wanted that rating about as much as I wanted a sixth toe on my left foot, but you have to get your field ticket before you can be made up to seventh grade, and I’m deplorably ambitious. I’m also a theorist, not a man of action; naturally contemplative, at home in the study, the cloister, the library, the chapter-house. Outdoors, in the wet mud, on my way to deal with problems in the real world, is not where I belong. But they send me because I get the job done—an early mistake on my part. On my first field assignment, I was under the impression that a splendidly successful outcome would win me merit and commendation. Silly me. What it got me was a reputation for being able to do this sort of thing. What I should’ve done was make a total hash of it, and they’d never have sent me again, and I’d be an abbot by now.

(“You understand these people,” Father Prior said to me, after he’d broken the bad news about this job. “You talk their language. You’re one of them.” I didn’t hit him because it’s not allowed. Perfectly true, of course. I was born and raised on a farm, in the horrible, primitive Mesoge. I left it to get away from backbreaking work and stupid people. So, what happens? They keep sending me back there.)

How can I begin to describe Rysart in the rain and the pitch dark? Yet another nasty little Mesoge village; the smell told me everything I needed to know before the first silhouetted barn loomed up out of the darkness. I knew the inn would be opposite the meeting-house, which would be at the north end of the one broad street. There’s no reason why it always should be, but it always is. It’s the way it’s always been done, you see. Lots of alwayses in the Mesoge.

The inn door was shut, but there were cracks of light under it. I tried the handle, but the bolts were shot. I banged on it and waited for a very long time, during which rain fell on me. I’d cancelled fulvens dissimilis as soon as the smell hit me, just in case, so I was getting wet.

“What the hell do you want?”

I smiled. “A bed for the night, please. You’re expecting me.”

She looked like I’d insulted her, but she opened the door anyway. The smell of dogs and wet wool made me catch my breath. I grew up with it, but when you’re used to a smell, you don’t notice it, until you’ve been away for a while, and then it hits you like a fist. It’s not actually an unpleasant smell, but it said home to me, and I left home a long time ago.

The room was the sort of thing you’d confidently store logs in without worrying too much about mould. The lentil and mutton stew came with a mountain of fermented cabbage. The water had that taste. The fire in the common room had burnt down to embers. “In the morning,” I said, “I want to see the Father and the mayor, and probably the reeve and the constable.”

She stared at me, as though I’d asked her to bring me her son’s head in a cream of asparagus sauce. But my tone of voice was just right. She nodded and got away from me as quickly as she could.

I wake up at sunrise, even when I don’t have a window. It’s a farm-boy thing, and I get teased about it all the time.

Even so; by the time I’d washed and had a good scratch, they were all waiting for me in the taproom, sitting in dead silence; six extremely worried men, the answer to whose prayers was me. They looked at each other as I walked in. I guess they’d had a vote and elected the Father to be the spokesman; fair enough. Did you ever meet a country priest who didn’t love the sound of his own voice?

“Are you—?”

I nodded. Spare him the embarrassment. “My name is Father Bohenna, and I’m from the Studium,” I said. “Now, I know the basic facts, but I’ll need you to fill me in on specifics. Then I can decide whether our intervention is called for, and if so, what the procedures will be, where your jurisdiction ends and ours begins, and so on and so forth. If we could start with some names.”

They introduced themselves. I’m hopeless with names. Unless I write them down, they’re in one ear and out the other. There are men I’ve known and worked with for fifteen years, but I have no idea what they’re called; they told me once, and you can’t keep asking or you make yourself look ridiculous. But I never forget a face, or a voice, or a body odour. So, the names washed over me like the spring floods, but I made a mental note. The tall, thin, crafty looking man, around fifty-five, bushy white hair, was the mayor. The two round-faced bruisers with the red cheeks—brothers—were the reeves. The little rat-faced man was the constable; I knew his sort, looks like the wind would blow him off his feet, but he draws the strongest bow in the village and God help you if you pick a fight with him. The seven-foot fair-haired idiot was somebody’s son, there to open doors for his father and sit still when not in use. A competent body of men. I’ve dealt with far worse.

The Father took a deep breath. “It all began,” he said—

Obviously, you hear some crazy stories in this job. Some of them you can safely discount. It depends on who tells them, and how they tell them. The thing in this case was that the Father couldn’t ever possibly have had an imaginative thought in his entire life. He wasn’t the sort. If you told him you were having a whale of a time, he’d look round the room for a whale.

It all started, he said, when two of the village girls began having fits. Nothing unusual in that, or at least not in the Mesoge. My sister was singularly prone to them; temper tantrums, floods of tears, right up till the day she realised that prospective husbands don’t really like that sort of thing, at which point she calmed down remarkably until the ring was safely on her finger. But these weren’t the usual sort of fits.

There’s something profoundly unsettling about hearing wild, spooky stories told by an utterly prosaic man. He described what the girls claimed they’d seen.

One night— You’re reading this, so you can read, so I don’t suppose you’re familiar with daily life in the Mesoge, so I’d better explain. Our houses have two rooms, one for the family and one for the livestock. The family room is square, with a hearth in the middle. We never quite got around to inventing the chimney, so we pitch our roofs high, to give the smoke somewhere to flock up and hover. We sleep on straw or feather mattresses in a square around the hearth. Rich folk with pretensions curtain off the back end for the man of the house and his wife—we did in our family; I can picture the curtain to this day, it was heavy felted wool painted to look like tapestry, the Ascension, and to the day I die the Invincible Sun will always have that crude, slightly half-witted face, like he’s just been woken up in the middle of the night. Children sleep in a heap, like puppies, on the opposite side from their parents, with the elderly, the poor relations, the dog, and the hired help making up the other two sides of the square. None of this should matter; the idea is that you should come in from work so tired out from your honest labours that as soon as you’ve bolted down your food you go straight to sleep. In practice; yes, we get on each others’ nerves like you wouldn’t believe, which is probably why the murder rate has always been so high in the Mesoge.

Anyway. One night these two girls (fifteen and fourteen) started screaming in their sleep. It took a lot to wake them up, and once they were awake they were lashing out, biting and scratching. Their father laid into them with a broom-handle to quiet them down. When they were coherent again, they said that a tall, well-dressed woman in a white lace cap had knelt down beside them and stuck them repeatedly with a brooch-pin.

Don’t be so bloody stupid, said their father, or words to that effect; but it happened again the next night, and the night after that, and then in broad daylight. Their mother went to see the Father, much to her husband’s annoyance. The Father found himself in a difficult position. He was and always had been a convinced sceptic. He didn’t believe in witchcraft, but he looked in his book—like most Mesoge priests, he only had one—and sure enough, the facts as related were a classic case of bewitchment, and he had no alternative but to treat it as such. He told the parents that their girls were bewitched, then sat down with his head in his hands and tried to figure out what he was supposed to do about it.

Now, so far, the only people who knew about all this were the family and the Father; but shortly after that, three girls in another family on the other side of the parish started doing exactly the same thing. They too were terrorised by an elegant woman in a white lace cap, though sometimes she came as a tall black-and-white nanny-goat, and sometimes she had a goshawk on her wrist. When the Father went to see them, the eldest girl started to tell her story, then broke off and tried to bite off her own tongue; she did quite a lot of damage before her mother got her jaws apart and stuffed her mouth with rags. And then a man in the village jumped out of a tree and broke his back; he lived long enough to say that a fine lady in a white bonnet had scooped him up off the ground, carried him to the top of the tree and pushed him off. A rich farmer in the valley lost ninety sheep to some sort of scouring sickness he’d never seen before. Six hay-ricks caught fire in the space of a week. A man came home from market to find a huge black bear waiting for him on his doorstep, in a district where the bears are brown and never come into the villages. It scratched up the side of his face pretty badly—the scars were plainly visible—he hit it with his stick, and it vanished into thin air.

By this point, the Father’s scepticism was wearing rather thin. He called in the mayor, who sent for the reeves and the constable, who convened an assembly of heads of families in the meeting-house. Needless to say, the meeting just made things worse. Everybody had strong views about the identity of the witch, and no two people had the same candidate in mind. When at last the Father could make himself heard, he told them there was only one thing they could do. And now, here I was, and what did I intend to do, and how soon could I start?

By this point, apparently, the witch was definitely getting above herself. She no longer operated at night—presumably she needed her sleep like everyone else, and she appeared to be operating on a massively overcrowded schedule, so who can blame her? On average there were between six and ten attacks a day, affecting roughly half the families in the village. Although the witch appeared only as herself or the black-and-white goat, there was no recognisable description, because as soon as anyone tried to describe her they bit their own tongue or bashed their head against a wall. She was visible on her own terms, generally only to the person she was afflicting, but very occasionally to three or four bystanders as well. The Father and the other elders tried to meet a few times to discuss a plan of action, but they gave up when she took to sitting down with them, on a chair that hadn’t been there before she arrived but which stayed there after she left. In fact, the same chair I was sitting in right now—

I stood up quickly, then slowly sat down again. “So you’ve seen her.”

The Father nodded. “But please, don’t ask me to describe her.”

I nodded. “No need,” I said.

He frowned, then all the colour drained from his face. “You can see inside my—?”

“Yes. But don’t worry. I’m an expert, and anything else I might happen to see I’m really not interested in.” He didn’t seem reassured, but I couldn’t help that. I mumbled aspergo devictos under my breath and looked straight at the side of his head and through it. “Thank you,” I said. “All over.”

The look on his face; he’d be happier dealing with the witch than me, any time. “You saw her?”

“Clearly.”

The constable said; “She’s standing behind you, right now.”

Nobody moved, especially me. “Is she now,” I said.

No reply. The constable’s mouth was open, but he didn’t seem able to speak. The others were looking down, at the ground, as though they were afraid of catching something really nasty through their eyes. Slowly I reached for my tea-bowl and drank what was left in it. Then I stood up and turned round.

Something lashed out at me. Scutum fidei and lorica will stop practically anything, but I felt the smack. Like a man in armour; the arrow or the javelin is turned and doesn’t pierce, but even so you get a hell of a thump. Instinctively—no, I’m ashamed to say, impulsively, with no proper control at all—I hit back with stricto ense or benevolentia or something of the sort, like you do in second year when you’re just starting on the military Forms; suddenly I’d regressed twenty years and forgotten everything I’d ever learned about fighting. It must have worked, though. I distinctly heard a scream, and then there was nothing there, except a bloodstain on the rushes.

I felt a complete fool. But the constable said, “Did you kill her?” in a tiny voice.

“No,” I said.

“But you beat her.”

I was still feeling disgusted with myself, and I really didn’t want to talk or deal with the public. I sat down again, carefully not looking at any of them. My hands were shaking. “Thank you for coming, gentlemen,” I said. “You can leave it to me now. This shouldn’t take long.”

“You can—?”

“Yes. Now, I think it would be advisable for everyone to stay in their houses for the rest of the day, if that’s at all possible. There’s no immediate danger, but it’s best to be on the safe side.”

That got rid of them, and I sat for a while perfectly still, thinking; what the hell was all that about? A stripe hard enough to put a dent in scutum and lorica, and a twenty-year professional panicking, overriding a lifetime of training and conditioning to swipe wildly with thunderbolts. I wasn’t afraid—there’s no power on Earth, literally, that scares me any more, because I know I can beat them all—but I was bewildered and unnerved and unsettled, and I had to think to remember things that are usually part of the furniture of my mind; the Rooms, the Wards, the precepts of engagement. I felt like I was heading for a duel with a sword in one hand and a fencing text-book in the other.

Still. The hell with it. I was able to outfight tenured professors when I was fourteen years old. I despise fighting, of course. That’s why I’m so good at it. I just want it done with and out of the way.

Someone asked me why there aren’t any women at the Studium. I said, the same reason there aren’t any fish. She gave me a foul look and changed the subject, but it’s a valid answer.

There are things men can do and women can’t (and vice versa, goes without saying) and what we do is one of them. To put it crudely, they don’t have the parts. We don’t actually know what the parts are—we’ve picked over God knows how many brains, looking for a particular blob of mush or twist of gristle, all to no effect. I don’t suppose we’ll ever find it until we get a chance to dissect one of the very, very few women (we figure something like one in two million) who’s got it, and that’s not likely to happen any time soon.

No great loss, is how we see it. What we do, the power we have, is of very limited practical value. We’re theorists, pure scientists; we aren’t actually very much use to anybody, and where we could make ourselves useful—wiping out armies, destroying cities, sinking whole continents under the sea, bringing the dead back to life—we don’t allow ourselves to, for obvious reasons. Stripped of all pretences, euphemisms, justifications, and obfuscations; the main reason we do magic is because we can. Generally speaking, though, either it’s useless or it mustn’t be used. Now, why would women, who are so much more sensible and practical than us, want to bother with something so pointless?

Witches are, of course, the exception. It’s a sad fact that, out of the tiny number of women who are born with the talent and figure out how to use it, ninety-nine out of a hundred go on to make insufferable nuisances of themselves; hurting, persecuting, terrorising the district with acts of petty spite.

My learned colleagues say that this is because in everyday life, women are powerless and marginalised; they have no way of striking back against a society that subordinates and belittles them. Thus, when one-in-two-million suddenly finds herself powerful, her first instinct is to settle scores. Personally I dispute this. Anyone who says women are powerless never met my mother. What they really mean is, upper-class women are powerless and marginalised—which is entirely true; and of course, that’s the only sort of women my colleagues have ever had dealings with. But most witches are your basic peasant stock, simply because so are most people. There’s no higher incidence of witchcraft in the gentry, and so the oppressed-and-victimised theory doesn’t convince me. Myself, I figure that anyone, man or woman, who has the talent but isn’t identified and whisked off to the Studium at age ten to be taught polite behaviour would naturally use such powers to bully and torment others because that’s human nature for you. Let any man pick up a stick and he’ll use it to hit someone else, unless the other man’s got a stick too. And nothing will ever change that, believe you me.

My colleagues and I, however, are civilised, educated men. We know what to do in practically every eventuality. Which is why we have nothing whatsoever to be afraid of.

Finding her was no problem. Insignia verborum; you learn it in third year because it’s nominally a restricted Form; God only knows why, it’s harmless enough. It lights up a glowing trail, like a phosphorous snail. A tiny drop of blood, or a hair, or a nail-clipping, is all you need. I picked up one of the bloodstained rushes, and I was off.

It was raining again, and when I opened the door I could see the trail winding away over the hills and far away. I considered requisitioning a horse, but I hate horse-riding, my back gives me hell for days afterwards. You’re not supposed to use Forms just to keep from getting wet and muddy, but who was there to see or care, and if they did, so what? It’s the Mesoge. Nothing that happens there matters worth a damn. I fortified myself discreetly and set off on my long trudge.

It was well after sunset when the trail petered out, and by then I’d walked further than I had since I joined the Studium. Forms can give you strength, but they can’t stop your feet aching. But anyhow, I found myself on the wrong side of a gate set in a thick hedge; the quality live here, it said. Gates don’t hinder me much, locked or unlocked. On the other side, I saw a short drive leading to a large square black shape. I tweaked the view a bit with lux in tenebris and made out one of those fortified manor-houses that you get in the Mesoge; half farmhouse, half castle, our legacy from the Troubles three centuries ago. Curious, I thought. No reason to assume my witch was the lady of the house. Probably between fifteen and twenty women would live in a house that size, most of whom would be working for a living. My witch could just as easily be a scullerymaid or a cook.

But she wasn’t. I looked for her—standing in the pitch dark, with rain dripping off my hood—with victrix causa and spotted her in the great hall. She was sitting on a stool by the fire, sewing a cushion. A few feet away, her husband was serving the loops on a new bowstring. He was about fifty, a fine-looking man with a neatly trimmed grey beard and broad shoulders. Two sons played chess on a low table; twins, most likely, around twenty. A greyhound slept on a bearskin rug. Your ideal picture of the country gentry at home, a beatific vision of aspiration for yeomen farmers and uppity merchants. Awkward. I had a problem.

I was, of course, entirely within my rights to burst in, seize her by force, and blast anybody who tried to stop me. I was perfectly capable of all that. I had the power, the strength, and the authority. But you don’t do stuff like that just because you can. It’s insensitive and uncivilised, and we aren’t thugs or bullies. I was going to have to wait until they’d all gone to bed. I went and stood under a tree, from where I could watch the windows. The bedroom would be on the first floor of the big round tower; it always is. After an eternity, a faint light flared in the narrow window. I muttered victrix causa and peeped in.

Country squires in the Mesoge are old-fashioned, and they don’t throw out good furniture just because it’s two hundred and fifty years old. The bed, therefore, was a huge thing, size of a small shed, with heavy tapestry drapes. I’m no voyeur; I cut the Form and gave them plenty of time to undress, get into bed, and blow out the candle. The window went dark. I gave them another eternity to fall asleep, then squelched in my sodden boots up the drive to the front door.

Any fool can draw bolts with summa fides, but it takes real skill to do it quietly. There’d be servants and dogs sleeping in the hall, and anybody I woke up would have to be put back to sleep with benevolentia or some other unpleasantness. But I’m really very good at all the sneaking-about side of things. I’d have made a good thief or assassin; now there’s something to be proud of. I climbed the stairs without a sound. The bedroom door had old-fashioned leather hinges, and the floor was spread with rugs. Perfect.

She was fast asleep, her head on one side, her hair loose. When we met at the inn, she’d had it done up in those horrible spirals, like wicker mats; it suited her much better au naturel. She was still neither particularly pretty nor particularly young, but a part of me envied the silver-haired gentleman lying with his back to her. Still; if there’s one thing I hate, it’s being made a fool of.

I slipped into her mind, exactly the way she’d do it. I kept my scholar’s robe, because that’s what people see when they look at me; not the prematurely bald head or the weak chin or the silly little snub nose. I wanted to be sure she recognised me.

You can’t take anything into someone’s dream; you have to use what you find there. In her dream, on the bedside table lay a fine old silver and amber brooch, heirloom quality—my guess is, a real brooch she’d always hankered after but never managed to acquire. I picked it up and unfolded the pin. In her dream, she was fast asleep. I stuck the pin through the lid of her closed eye, then pulled it out.

She opened her eyes. One she couldn’t see through, the other stared at me. “Hello,” I said.

In her dream, she yelled. I shook my head. “Nobody can hear you,” I said. “We need to talk. You’ll find me at the inn.” Then I stuck the pin in her other eye and got out fast.

She hadn’t moved, though her eyes were tightly screwed up. Her husband was still fast asleep, so I guess she was a restless sleeper at the best of times. I blew her a kiss and went back down the stairs. I think a servant opened one eye and saw me as I thumbed the latch of the front door. So what?

I slept well that night. Genuine Mesoge sleep; healthy exhaustion after a hard day of useful, profitable work.

Some fool woke me up while it was still dark outside. Just as well for him I have perfect control; there are horror stories of servants at the Studium being blasted into cinders after waking up senior faculty members who weren’t morning people. There’s a lady to see you, said whoever it was. Note the choice of noun. He sounded deeply impressed.

I’m afraid of nothing, but I’m still capable of embarrassment. How do you start a conversation with a witch you recently blinded in her sleep, who also happens to be the local bigwig’s wife? As I pulled my hose on I decided I’d better be cruel and heartless, though I know full well I’m not very good at it. Probably she’d see through it straight away. As I stuffed my feet into my boots, which were ice-cold and clammy with last night’s rain, I thought; the hell with it, I’ll just be myself. Not a part I’ve ever been happy playing, but it’s less of a drain on my limited imaginative faculties.

She was sitting on the chair she’d conjured up and then not known how to dissolve. I don’t think she meant anything by it; probably she didn’t recognise it. A spiteful man would’ve vanished it with her still sat in it, but I’m not like that. I had no idea how to address her, so I settled on ‘Madam’, which is usually correct in the country.

She looked at me. Her eyes were bloodshot. Also, she had a cut on her cheek, just starting to scab over. I hadn’t noticed it the night before, so presumably she’d been lying on it. I did that, I thought guiltily, lashing out like a schoolboy. She was wearing a white lace cap and a heavy wool cloak, fastened at the shoulder with a simple silver starburst brooch.

I cleared my throat. “The cap,” I said. “Indiscreet.”

She shook her head. “I wear it all the time, so naturally nobody sees it any more. I assume you’ve told them.”

I was shocked. “No, of course not. I think we ought to find somewhere a bit more private.”

That made her grin. “Are you suggesting I go up to your room? I don’t think so.”

“Allow me.”

So, I wanted to impress her; of course I did, from the first moment I saw her, in the inn. So what? A show of power would terrify her, let her know she was dealing with someone infinitely stronger than herself; it would serve a useful purpose and therefore was allowed.

I touched her shoulder with the tip of my finger and took her to the third Room.

It’s just occurred to me that you may not know about Rooms. You’re not supposed to. Rooms are classified top secret, not to be mentioned or hinted at in front of unqualified personnel. I could get in big trouble if I were to tell you anything at all about Rooms. Basically, it’s like this.

Imagine you’re in a big house, or a palace, or a government building. There are lots of rooms in it, but for some reason I can’t begin to imagine, you’ve lived your entire life in just one of them. The concept of a door is so weird and unnatural to you that either you dismiss it as some crazy fantasy or else it terrifies you—anathema, abomination, and other words beginning with A to convey pious disgust.

At the beginning of second year, the class tutor shows you how to make a door. It’s the most extraordinary thing that ever happens to you, and you remember it for the rest of your life. After that, your sense of wonder gets work-hardened; miracles make you yawn, inconceivable wonders are just another day at the office. But your first door is always with you. It’s the moment when the world changed for ever.

In theory (and if I do manage to get tenure, it’s the area of theory I intend to devote the rest of my life to) there’s an infinite number of Rooms, linked by an infinite network of doors, stairways, and passages. In theory, you could get so good at this shit that instead of going to the Rooms, you could just sit there and all the Rooms would come to you. In practice, there are seven Rooms, and if you’re really brave and incredibly skilful and outrageously lucky, you might get to visit six of them by choice before you end up in the seventh very much against your will. In everyday life, you use three. I chose the third Room on this occasion because it’s always been my favourite. If there’s anywhere in the world this Mesoge farm boy is at home, it’s the third Room. When I’m there, I’m in control.

Normally, wherever and whoever you are, you aren’t in control. You may think you are, but you’re not. If you’re the Great King of the Sashan, brother of the Sun and bridegroom of the Moon, and you happen to let your favourite crystal goblet slip through your fingers, it’ll fall on the marble floor and smash into a thousand pieces, and if you cut yourself on one of the pieces and get blood poisoning, you’ll die. But when I’m in the third Room, if I drop something, it needs my permission to fall. Don’t get the idea that it’s like that for everyone in the third Room, by the way. I know a tenured professor of applied metaphysics who wouldn’t go in there if you paid him, because there are monsters under the bed. I know how he feels. You wouldn’t get me in the fifth Room if the rest of the world was on fire; yet my friend the professor goes there to relax and hide from his married sister when she calls for a visit.

I’m a bit of an old fusspot when it comes to décor. I know what I like. My small-r rooms in the West cloister of the Old Building are small, cold, and damp so I can’t really be bothered with them, but I’ve fixed up the third Room exactly how I like it. The walls are panelled oak, sort of a dark honey colour, with genuine late Mannerist tapestries depicting scenes from Chloris and Sorabel. On the floor I’ve got a rattan mat, because I love the smell and the way it cushions your feet. The ceiling is plaster mouldings with the details—birds nesting among the acanthus leaves, that sort of thing—picked out in gold leaf, because what is life without a few restrained splashes of vulgarity? The furniture is dark oak, almost black; two carved chairs, a table, a bookcase which only occupies half a wall but which somehow manages to hold all the books I ever want to read; three brass lamps; my grandfather’s sword on the wall just above my head, nice and handy if ever I need it; a footstool. And the nice thing is, I can go there for a whole afternoon and when I get back, I’ve only just left.

“What the hell?” I said.

I don’t usually swear in front of women, especially upper-class ones. I stared at her. She smiled.

It was the third Room, because I’d brought us here, up the second staircase, across the dark landing. I’d opened the door, my thumb on the old-fashioned wooden latch. More to the point, I was in front of her. It’s different when someone gets into a Room ahead of you, or you go in and it’s already occupied. I’m always very careful about that, believe me. But no, I’d opened the door and walked in, and then she followed me. “What have you done?” I said.

She pushed past me and sat down. There was only one chair. I had to make do with a low three-legged stool by the fire. She picked up her embroidery and carried on where she’d left off the night before. The boarhound lifted its head and growled at me.

“You can’t bring dogs into the third Room,” I objected.

“Can’t you?”

“It’s against the rules.”

“Then the rules are silly,” she said, licking the end of her silk before threading her needle. “You wanted to talk to me about something.”

I stood up. This wasn’t right. I headed for the door, which wasn’t there.

Father Anthemius taught me how to make a door. The shameful fact is, I was a slow beginner. All the other kids could do it, I couldn’t. Not for want of trying; but it’s one of those things where effort is useless, bordering on counter-productive; like falling asleep, the more you try, the less you succeed. It’s easy, they all told me, you just think of a door and there it is.

So I thought of a door, and there one wasn’t. All right, they said, try this. Think of a door, but you can only see it out of the corner of your eye. Didn’t work. So they explained to me about peripheral vision, and how you can see things without looking straight at them. Made no difference. I was ashamed and desperate. If I couldn’t make a door, I couldn’t learn anything else, they’d have to send me home, back to a two-room shack in the Mesoge. I wasn’t having that. In all other respects I was well in advance of the rest of my year and I’d already sneaked a look at the basic military Forms in the textbook. I reckoned ruans in defectum standing in front of a mirror would do the trick nicely, and there wouldn’t be enough of a body left to be worth shipping home.

Enter Father Anthemius. He had retired from the teaching staff the year before I arrived and nobody was sorry to see him go. He was a miserable old bastard who hated kids, and he’d only got into teaching because he couldn’t make the field grades, which was all he’d ever wanted to do. His students had hated him, partly because he was hypercritical, judgemental, and mean, partly because of his habit of farting loudly during tutorials; the smell, they told me, had to be experienced to be believed. He found me in a corner of the cloister, crying my eyes out. He looked at me.

“You’re pathetic,” he said.

I looked up at him. “I know,” I said.

He sighed. A stupid little kid bawling like a girl because he couldn’t do the simplest thing in the syllabus. “You’re trying too hard,” he said.

“I know.”

“No bloody good you knowing if you keep on doing it.” He slapped my mind with eget regimine and I squealed, which made him even angrier. “You’re disgusting,” he said. “The sooner they throw you out and you go back to mucking out pigs, the better for all of us. They shouldn’t let you people in here in the first place. You’re no good for anything.”

I think he was trying to provoke me. He could see I knew some military forms, and if I lashed out with one of them he’d be justified in blasting me till I glowed. He filled my head with bees and locusts so I couldn’t think, then started up again with eget regimine. I don’t know if you’re familiar with it; they call it the teacher’s friend, because it hurts like hell but leaves no marks or traces whatsoever. I tried to get up and run, but he’d locked me down with something or other that made me feel like the whole building was pressing down on me. I could hardly breathe. He was grinning at me, and I felt him inserting something into my mind; memories, false ones, about having fits when I was a baby. Clever; he’d crush me until a blood vessel burst and I had a stroke, and when they looked inside my head they’d find memories of similar attacks going right back through my life. I wasn’t sure why he hated me as much as he did, but there was no doubt in my mind at all. Something about me was so objectionable that I couldn’t be allowed to continue, and he was going to see to it that I didn’t. I felt his hand pass through my skull, feeling for the vein he was going to pinch shut. Out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of a door. I jumped to my feet, wrenched it open, tumbled through, slammed it shut, and collapsed.

“See?” said a voice. “Nothing to it, really.”

I looked up. Father Anthemius was sitting in a carved oak chair with his feet up on a footstool. “This,” he said, “is the third Room. Most kids your age wouldn’t make it this far, but you’re precocious.”

I turned my head and looked at what I was leaning against; a massive oak door, studded with nails, like you see in castles. The nails are clenched over to hold the plies of wood together. You lay six plies with the direction of the grain alternating at right angles. A door made that way is practically unbreakable, even with a battering ram.

“You came here because it’s safe,” he said. “Once that door’s shut, nothing can get in unless you want it to. Nobody taught you that, you figured it out all by yourself.”

“I made a door?”

He laughed. “I certainly didn’t, so you must have, mustn’t you? I told you it was easy.”

I lashed out at him with ruat caelum. He swatted it aside. “Too slow,” he said. “Do it again.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t know what I was—“

“Do it again.”

Nobody taught me ruat caelum. I do it better than anyone else in the world. I’d been practising it for years on birds, flies, anything really small and fast, before I found out it was called that. To do it right you have to focus on a pinprick. I narrowed everything right down and let him have it. But he wasn’t there.

I stared. Had I hit him so hard he’d completely disintegrated? But then a door opened in the wall and he stepped through. “Which proves my point,” he said, sitting down and putting his feet up. “Rooms are everything. Doesn’t matter that you’re faster than anyone else I’ve ever seen. All I have to do is go next door and you can’t touch me.”

I felt as though a tap had been opened and my soul drained out of it. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I got mad.”

“Of course you did,” he said. “You were angry with me, instead of yourself. And before that you were afraid of me, instead of afraid of failing. You could be good at this. But you won’t ever be unless you stop feeling sorry for yourself all the damn time.” He stood up. “Like I said, you’re pathetic. If I hadn’t taken pity on you, you could’ve gone on trying the rest of your life and never got there. Lucky for you I’m such a sweetheart.” He stood up. “Till we meet again,” he said. Then he walked through the door he’d made and closed it behind him, and I was sitting alone on a stone bench on the cloister. I never saw him again; he died that afternoon. I didn’t find out he died until a week later. Apparently he was born at Spire Cross in the Mesoge, just a few miles downhill from where I used to live. Small world.

Anyway, the point is, ever since then I’ve been really good at doors. I can make one in a flash, and my doors go to places my esteemed colleagues would never dream of being able to reach. It’s the one thing I’m supremely good at. Hopeless at many things, good at doors, that’s me.

I tried to make a door. Nothing happened.

She yawned. “You can try again if you like. Won’t do you any good. This is my place. I’m in control here.”

I fixed my eyes on her so she was the centre of my field of vision. At the edge there should be, had to be, a door. There wasn’t.

“You’re pathetic,” she said. “Did you know that?”

“Actually, yes,” I said. “Let me out of here right now, or I’ll kill you.”

She smiled. “I wouldn’t,” she said. “I’m sure you could, you’re so much bigger and stronger and more aggressive than me, but then you’d be stuck in here for ever and ever, since you can’t make doors. Of course you wouldn’t be entirely on your own, you’d have the dog for company. But he farts. It can be pretty unbearable in a confined space, believe me.”

That draining feeling I told you about. Only the second time in my life I’d experienced it, but once endured, never forgotten. “Fine,” I said. “You win.”

She clapped her hands together in girlish glee. “Do I really? How nice.” I felt a searing pain in the backs of my knees, as though someone had cut the tendons. Then I slumped forward, kneeling before her. I couldn’t feel my feet at all. “Now then,” she said. “The thing is, I don’t know how to do the next bit, never having been to college. But that doesn’t matter, because you do.” She smiled. “Much better really,” she said. “Why should I give up years and years of my life sitting in draughty libraries learning stupid old theory when all I actually need to do is open up your head, and there it all is, ready for me to use?”

My head was splitting; now there’s a coincidence. “It doesn’t work like that,” I said.

“Doesn’t it?” She reached out and picked up a book, the only one in the room. She opened it, and I screamed. It was as though she’d pulled the two halves of my skull apart, like opening a clam. “What a pity. No, you’re wrong, here it all is.” She ran a finger down the page. “Chapter six, how to steal someone’s mind.” She turned a few pages. “Doesn’t look too hard. Shall we have a go?”

I slashed at her with stricto ense. She parried with the cover of the book. I yelled and clamped my hand round the gash in my cheek. Blood was gushing between my fingers.

“Let’s see,” she said, turning a page. “It’s all pretty straightforward by the look of it. Stands to reason, really. If it was hard, you couldn’t do it.”

Desperately I tried to remember about Room theory, but I couldn’t.

“I feel a bit guilty,” she said, as I felt my mind emptying. “Playing all those nasty pranks on my neighbours. They’re stupid and dull as chicken broth but there’s no real malice in them. But it was worth it, to get you down here. I knew it was the only way. I’d never be able to go to your stupid college or read your stupid books, so all this wonderful talent I’ve been given would just go to waste, and where’s the sense in that? But then I thought, what’s a book? It’s the inside of someone’s head put down on paper so anyone can see it, and it’ll never, ever die. Do you know I can’t read? Women don’t, not even delicately nurtured ones like me, it’s not ladylike. So it’s just as well I’ve got a wise, clever man like you to do it for me.”

“Please,” I said. “Don’t.”

She looked at me over the top of the book. “You’re pathetic,” she said, and carried on reading.

I tried ruat caelum, which I’ve known since I was thirteen years old. I couldn’t remember it. I tried to think of a Form, any bloody Form. They’d all gone. She looked up and folded down the corner of a page. The pain made me howl like a dog, and the boarhound lifted its head off its paws and growled again. “Don’t set him off,” she said, “or he’ll start barking.”

And he farts, I know, you told me. I could feel slices of myself falling away like apple-peel in spirals, things that had been a part of me before I was truly myself. Meanwhile she read, calm and steady, and each time she turned the page I screamed, and she took no notice.

“I don’t know what you’re making all that fuss about,” she said. “Anyone would think I was skinning you alive. It’s only knowledge, after all. When I’m done I shall turn you loose, and then you can live the rest of your life the way I’m supposed to live mine. I think that’s only fair, don’t you?”

I didn’t have the strength to argue, or the words or the wit to argue with, or even enough understanding to know if she was right or wrong. The only argument left was strength; she was strong and I was weak, so presumably everything she was doing to me was just fine and exactly how it ought to be. I can live with that, I remember thinking; it’s so simple even I can understand it, and if it pleases her to spare my life and let me crawl away, I’ll be grateful and worship her for her goodness and loving kindness.

She knew what I was thinking, of course. “You’re pathetic,” she said. “But I guess you know that.”

“I’d sort of gathered.”

That made her laugh. “You’re just a book, see?” She held up the book. She had it upside down. “All those clever men spent years copying things into you, and now I’ve copied them out again. Actually, not copied.” She grinned. “A real book must be a wonderful thing. It can be read over and over again and it’s not diminished. You’re not a book after all, you’re just a barn.”

“Make your mind up,” I said. It cost me the last of my strength. One last wisecrack and now I’d be stupid for ever. Ah well. Everything was, no doubt, all for the best.

“I ought to thank you,” she said. It was one of those books that has clasps and a hasp for a tiny lock. “But screw that. The hawk doesn’t thank the sparrow, because it’s rude to talk with your mouth full. All right, you can go now. I don’t need you any more.”

A door opened and swung wide. She wasn’t looking at me. She had her nose in the book. I tried to stand up, but my legs were numb, so I started to crawl toward the door, pulling myself along with my elbows. I had a horrible feeling that I wasn’t going to like what lay on the other side of that door. The sort of life she’d have had if she’d been born normal, without the talent. I’ve come across some terrifying things over the years, inside Rooms and out of them, but nothing quite as bad as that. We use the phrase fate worse than death frivolously, like children playing with a spear they found in a corner of the barn; but there are things much worse than simply being dead, and a life like that would be one of them. Somehow, though, I didn’t seem to have a choice. She was just stronger than me, that was all.

The boarhound lifted its head again and made that ominous grinding noise. I pulled myself a few inches closer to the door, and the boarhound sprang up and leapt at me—over me—

I turned my head in time to see her on the ground, the huge dog standing over her, worrying at her neck locked between its jaws. It used its shoulders and back to rip her throat out; a quick, spasmodic movement, a snatch. It’s rude to snatch, my mother used to tell me. Now I could see why.

The dog lifted its head and swallowed, two big gulps, all gone. She’d stopped moving. The dog sat up straight and farted.

It was really bad, enough to make your eyes water. When they cleared and I could see again, Father Anthemius was sitting in a chair. The room was different. There was a big, broad table covered in clutter—rolls of paper, books, empty cups, chunks of mouldy stale bread, rat droppings—and a fireplace. The fire was lit. That room was always too hot, I remembered people telling me. What with the heat and the godawful smell, how was anybody expected to learn anything?

He was reading a book. He closed it, looked at me, and tossed it into the fire. The pain, which was worse than anything I’d ever felt before, lasted as long as it took the book to burn. He reached over with the poker and pounded the dove-grey ashes into dust, then looked at me.

“Well?” he said.

I nodded. It was all back again, everything she’d taken from me. I felt as though I’d had a big brush, like the sort sweeps use to clean chimneys, shoved down my throat and pushed really hard until it came out through my arse. “I saved your life,” he said. “Again. You’re pathetic. But you know that.”

“Yes.”

“Obviously I didn’t do it for your sake,” he went on. “You’re worthless. I did it simply in order to survive. If you were stripped of your talent, where would I go? I would be lost, like the only copy of a book burnt in a fire. That would be a tragedy. Naturally, I couldn’t allow it to happen.”

“Naturally.”

“Even so,” said Father Anthemius, “I suppose I owe you a certain degree of gratitude. Don’t you think?”

I nodded. “You were dying,” I said.

“I was,” said Father Anthemius.

“You knew you didn’t have long. It made you angry.”

“Very angry. If there’s one form of vandalism I can’t stand, it’s burning books.”

I reckoned I could afford one wan smile. “Quite,” I said. “You’d spent your entire life writing all that learning and wisdom into a book, and the moment you write the last word, it’s snatched away from you and thrown into the fire. Where’s the sense in that?”

He nodded. “I don’t mind cruelty,” he said, “But I can’t abide waste.”

“So,” I went on, “you considered Room theory. It’s always been your best thing. Whenever there’s any danger, you just duck into another room. You showed me that, when I got angry.”

“Fancy you remembering.”

“You saw me,” I went on. “And you saw that I was—“

“Defective,” said Father Anthemius. “Or would you prefer inadequate?”

“Defective, thank you. You saw I wasn’t capable of making a door. I could do Forms and other stuff, but I was missing the ability to make a door, which meant I could never progress any further, or qualify, or be a practitioner. Which meant they’d throw me out of the Studium and I’d have to go back to the Mesoge and spend the rest of my life ploughing and herding pigs.”

“Actual useful work.” He grinned. “Perish the thought.”

“So you pretended to teach me how to make a door,” I said. “But that’s not what you did. You got me scared out of my wits so I wouldn’t see what you were doing—“

“Like a fly,” he said, “laying its eggs in a wound. A dreadful thing for a man of my distinction, but what choice did I have?”

“You turned my head—me—into a Room,” I said. “Your body died, but you weren’t in it. You were—”

“Plenty of space in there,” he said, “which you weren’t ever going to use. Admit it, I’ve been as quiet as a little mouse. You never even knew I was there. And thanks to me, you became a great wise scholar, which you never ought to have done.”

The maggots of wisdom, I thought, gnawing away at me and building nests of scholarship in the holes they’d made.

“Without me,” said Father Anthemius, “you were pathetic. You were as weak and useless as a woman. Actually,” he added, “I take that back. I was tempted, you realise. She was so strong, more natural untrained ability than I’ve ever seen in one human being in my entire life. I could have slipped into her mind and she’d never have known I was there, and I’d have had access to more strength, more sheer ability than I’d ever thought was possible.” He shook his head. “But she was still a woman,” he said. “Even with me to guide her, nobody would ever have taken her seriously. And then what? She’d have ended up making war on the whole world, like she did on the people in her silly little village, out of frustration and sheer spite. I hate waste,” he said. “I would’ve been wasted on her. So I decided to stay with you, even though you’re pathetic.”

But very good at Forms nonetheless. I formed stricto ense in my mind and aimed it at him. He smiled at me. “Sure,” he said. “Go ahead. You kill me, I die, you’ll never be able to make another door as long as you live. Well, get on with it. I’m waiting.”

That was a long time ago. He’s still waiting.

I met the mayor and the constable on my way out of the village. All done, I told them.

“You found out who it was?”

I nodded.

“Who was it?”

I took a deep breath. “Tell you what,” I said. “Give it a week, then ask around. Whoever hasn’t been seen for a week, that’s who it was. All right?”

They wanted to ask me questions, buy me a drink, hold a parade, give me money, put up a statue, make speeches, rename the village after me, all that sort of thing. Go away, I told them. I just want to get out of the horrible Mesoge. I think I offended them. So what?

I can raise the dead. Not that I ever would, it goes without saying, because it’s absolutely forbidden. Actually, I always assumed that was a convenient cop-out on the part of the profession—yes, we could do it, of course we could, we can do anything. But we don’t, because it’s illegal and unethical, so you’ll never know if we’re telling the truth or not. Big deal.

But yes, I can do it. Crazy, really. I can call back the dead, take those ashes and that dust and turn them back into pages. I can unburn books, but I can’t make a simple door. A bit pathetic, really, but there you go.

And it was the Mesoge, for God’s sake. There was nobody to see me do it, and if someone did see, nobody would ever believe them, because all country people are superstitious idiots, everybody knows that. A talking rat with LIAR branded on its forehead would stand more chance of being taken seriously by my esteemed colleagues at the Studium than anyone born within fifteen miles of Spire Cross. So why not?

I won’t tell you the Form, not that it really matters. What matters is standing in the narrow passage off which opens the door to the seventh Room. I’d been there before, but this time I was all too painfully aware that he was there with me. I couldn’t see him, but the lingering stench of dog fart was unmistakable. Never mind. I knocked on the door. “Come in,” she said.

She was sitting in front of the fire, embroidering something. “Oh,” she said. “It’s you.”

I stood in the doorway. Believe it or not, I was in no tearing hurry to go fully inside the seventh Room. You’re all right if you have one foot firmly planted in the passageway, or so they tell me. How they would know that I have no idea.

“Don’t give me that look,” I said. “I didn’t kill you.”

“No, your dog did. Big difference.”

I grinned. “Actually, I think it’s a moot point whose dog was whose, if you see what I mean. You go through life thinking you’re the owner and it’s the dog, and then you realise, who’s actually walking who?”

She gazed at me. “You’re an idiot,” she said.

“I suppose I must be,” I replied. “All that time and I never realised. How about you?”

“Oh, I always knew, right from the start. I knew I was better than everybody else in the whole world, but they wouldn’t let me be myself.”

“So you took to sticking pins in people. To show them how much better you were.”

She shrugged. “Not through choice. If I’d been allowed to use my gifts and realise my true potential, it’d have been thunderbolts, not pins.”

“What did they ever do to deserve it?”

“What did you ever do to deserve what you’ve got and I could never have?” She put down her needlework and took in the room with a wide, circling gesture. “I spent my whole life stuck in this place,” she said. “And now I’m dead, and look where I end up.”

The Mesoge, I thought. It’s where you go when you die, if you’ve been really bad. Or you’re born there; same difference. The Mesoge is where I belong.

Just because I can do something, it doesn’t necessarily follow that I want to. Or that I should. Besides; giving her back a life like hers—I don’t think I could be that cruel.

So I left her to her vengeful wallowing, which I regarded as pathetic, and went back to the third Room. But I couldn’t stay there for more than a minute, because of the smell.

© Copyright 2020 K.J. Parker

0 notes

Text

Dead Ringer

"Screaming.

It’s the first thing he’s aware of..."

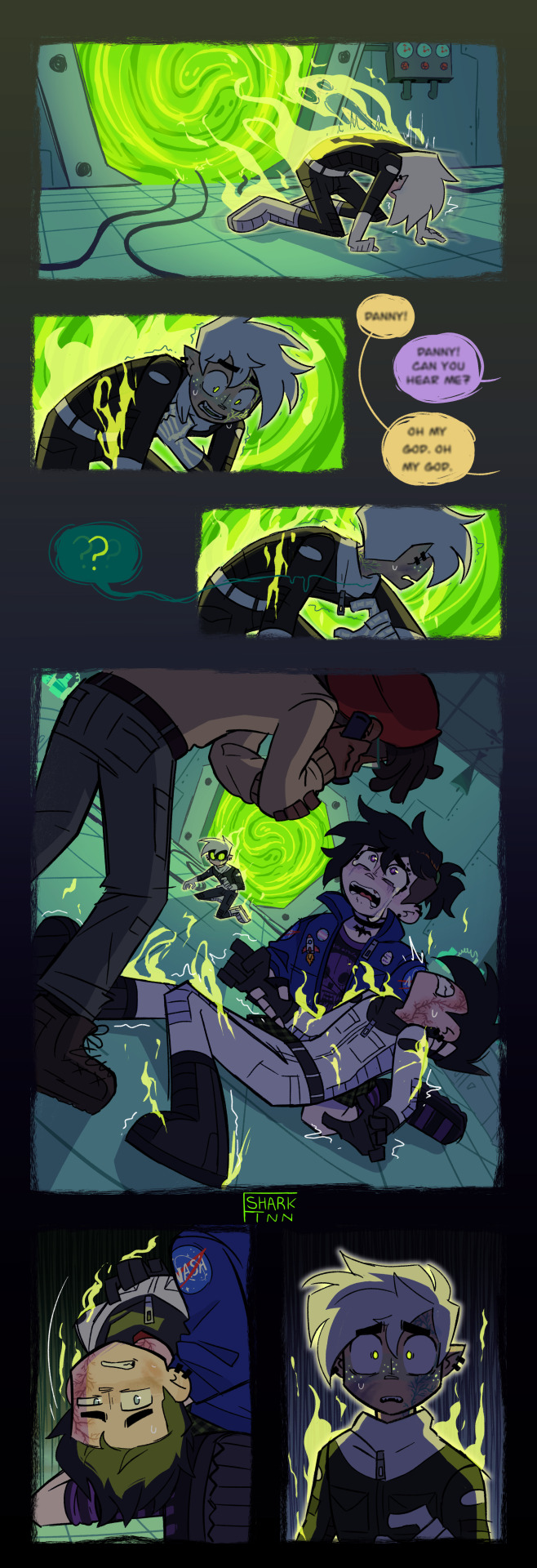

Here's my submission for @ecto-implosion !!!

And a link to the amazing fic @browa123 wrote based on it!!!!! It's REALLY well done, it was sooo fun working with you and I couldn't have hoped for a better end result 💚

Thanks for having me!! I've had this idea for years and finally got to use it for something COOL, I'll definitely participate again if there's another implosion in the future. I met so many talented people

#ectoimplosion2023#ectoimplosion#danny phantom event#danny phantom#danny fenton#dp fanart#dp art#danny phantom comic#danny phantom fanfiction#phanart#sam manson#tucker foley#separate fenton and phantom#split fenton and phantom#dead ringer#sharkfinnarts#sharkfinn#browa123#i was so obsessed with putting as many tiny details and headcanons into this as i could lol#anyway seriously go read the fic its so well set up i was kicking my feet and screamin

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

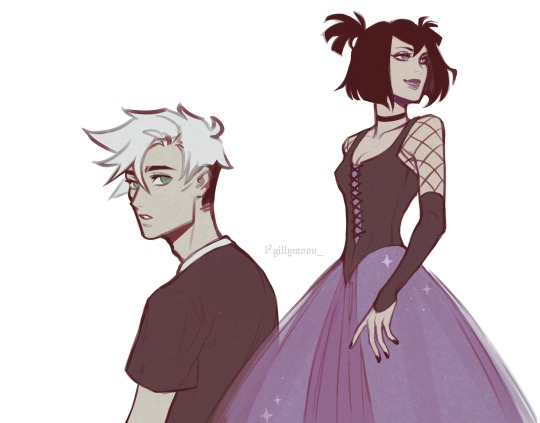

If Danny Phantom was set in a modern D&D world.

Tucker is a Gunslinger / Artificer multiclass, picking up old tech from Danny's parents and improving it.

Dani is the princess of ghosts and was so excited for Danny to join her and become her actual big brother.

Danny originally found Dani's skull in Vald's dungeons, he brought her to life with his awakening ghost powers (sorcerer).

Sam would be a Warlock whose patron was Danny but has moved to Dani as they work forward to save their friend/brother.

(these are just some ideas I had while working on the piece)

#dnd#dungeons and dragons#danny fenton#danny phantom#tucker foley#sam manson#vlad plasmius#dark danny#dnd art#digital art#fantasy#digital painting#digital fanart#cartoon#how many ghost can you spot

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

First sketches after I got back into the Phandom ☆

#danny phantom#sam manson#tucker foley#how many goths were born from the childhood combo of sam manson and raven lol#its me im the goth#my art

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gotham-Amity Co-op AU Part 3

Part 1 | Previous | Next

“Hola beauties, and welcome back to Fashionable History, I’m Paulina,”

“And I’m Star, and on this channel, we teach you how to be at the height of fashion, no matter what time period you find yourself in.”

“Now for our long-time viewers who missed our community posts, you might be wondering about the change in location. Well, we are moving up in the world. That’s right, fam, we are officially-

“College girlies!” The two shouted into the camera.

“Ah, such a big step,” ‘Star’ sighed.

“Indeed it is. And to celebrate, let us dress up like we’re going to meet the queen of fashion herself: Marie Antoinette!”

***

“So you would think it would be hard to demonstrate Amity Park’s weirdness while no longer living there, but you would be wrong,” a black man said into the camera while walking down a hallway, his glasses fallen ever so slightly down his nose. There were voices in the background progressively getting louder. “You see, Danny’s mentor popped by this morning, and apparently, he decided that the perfect way to tutor Danny and piss off his bosses at the same time was to allow a bunch of college kids to summon a historical figure of their choosing to discuss their area of expertise. Once a week.

“Jazz got to go first.”

The black man stopped in a doorway. Much clearer in the background was a woman’s even voice. “And Jazz, being the future psychologist that she is, picked the most sex-obsessed man in history.”

The camera flipped to show a young red-head sitting across an older man with a white beard in a blue three piece suit. In the background was a younger man, his blue eyes glazed over as he sat there sipping from his mug, his head of black hair bobbing as he fought to stay awake. Really, it wouldn’t gather a second glance, except for the tiny detail that the older man’s skin was as green as a sunburnt person’s was red.

“-indeed homosexuality is not an illness, and in fact the only link between it and mental health has been observed to be caused by familial and community reactions.”

“That is good to hear. Indeed, many people throughout history were homosexual, and a lot of them did not show any other signs of mental illnesses.”

“It is. However, with the recent pushes for public acceptance of those not heterosexual, many have come forward with sexual orientations beyond just hetero and homosexuality, including those that are attracted to both men and women at the same time, as well as those who experience no sexual attraction or are completely repulsed by the idea of anything sexual.”

The camera flipped back to the first man. “She is explaining how psychology has developed in the last 100 years without trying to rip apart Freud’s work.

“This isn’t even the first time something like this has happened. Occasionally, we’d get guest speakers that would turn out to be some famous author or pioneer in their field. It’s how our English teacher got his copy of the Tempest signed by the original author. I think this might be the first one that won’t end in a raid by government idiots in white, though.

“So yeah, we occasionally get to talk to dead celebrities and don’t bat an eye at it. Amity Park is very weird.”

***

“Danny! You left your cups in the sink again!”

“How can you tell it’s mine?”

“They’re glowing green and you’re the only one that drinks ectoplasm! Now take care of them before you bring the food to life again!”

“Fine…”

The camera pans over to a goth woman giving the camera a flat look. On screen, there’s some text that reads: ‘When your boyfriend forgets to clean off his dishes after his mildly radioactive smoothies.’

***

“Urgh!” Just die you stupid, lazy skeleton!”

“How long is this attack going to be!”

“I don’t care, because when it’s finally my turn, I am going to stab the dust out of this depressed sack of bones!”

On screen was a couch, and on that couch sat 3 young adults, two women and one man. One of the women was Valarie Gray, US National Taekwondo Silver Medalist, was jabbing her thumb down on the d-pad of her controller, lips pulled back in a snarl. The other was Samantha Manson, more known for the TikTok channel Our Strange Lives. The man was a muscular blond. All three were focusing on the screen, their eyes emitting faint light and Valarie’s teeth seemed to be getting sharper.

Quietly a blond woman walked on screen, a backpack slung over her shoulder. The woman was Star Strong from Fashionable History.

“You guys are still streaming?”

“This boss is stupid difficult and Manson and Gray are the only ones willing to play.”

“What happened to the guys?”

“Fowley, Wes, Singh all had work. Fenton got to the first boss and then lost it because ‘Goat Mom just wanted to protect us’ before getting a call from his lil sis asking for help. Kwan is working on a lab with a guy from his chem class, and Kyle passed out a couple hours ago.”

“Stop dodging!”

“Wanna play?”

“Can’t. Going to the library to study for a calc exam I have coming up. See you guys later.”

“Later.”

“FUC-”

***

“And so, with this polaroid image, we have evidence to prove that-”

“Hey, Wes, do you have something I can use for a collage? Oh sweet, thanks bro!”

“What? No! Kyle! Get back with that! That was the proof I was going to use to prove the existence of Yetis!”

“Oh damn. This is some nice creature work! Danny, your friend has an incredible costume, man!”

“Thanks, Kyle! I’ll pass it on!”

***

Tim paused the video right as Wesley Weston stood to chase his older brother.

There.

The red-head’s eyes had a slight glow to them. Tim clicked over to the other images he had gathered of the Amity Park teens, all with their eyes glowing or other signs of something inhuman.

Tim had been introduced to this group by Stephanie when she found a martial arts demonstration Gray did that involved breaking multiple boards, all several feet above her head. Stephanie had meant it as a ‘check out his cool person doing what we’re doing,’ but Tim noticed something. All the boards were being held by seemingly the same person- or at least people dressed very similarly. And not in a way where they’re sitting on a ledge above Gray and are switching out the board each time she broke one. More that there were multiple companies of the same white glove all holding a board and all floating several feet above where they should have been. That was already a little weird, but it could’ve been some special effects or just a uniform.

No, what caught Tim’s attention was the quick glimpse of the face of one of the board holders. It was youthful- late teens- but with paper white hair that showed no signs of bleaching. Now these features would have been a thing to cement the mysterious person in Tim’s mind. But it wasn’t that.

No, what got Tim to do some digging to find out about a previously unknown supposed hero from a small town that has been blacked-out by the US government, was his eyes.

His calm, glowing Lazarus green eyes.

***

So we finally get a taste for the shenanigans our liminals are up to. Sam, Tucker, and Danny all share a TikTok where they show off how weird the other two are and how weird their town is. Wes is trying to prove cryptids exist, which Kyle ruins. Dash has a gaming stream that most often Kwan joins in on, and Paulina and Star do dress history. Oh, and Valarie is a national taekwondo because karate has only been an event for one Olympic games, but taekwondo has been an event since 2000 and Val seems more like a kicker than a thrower. Plus, I actually took taekwondo when I was younger.

We do get another Bat showing up at the end. There is absolutely no plot, however, so who knows where this is going. Certainly not me!

I'm still looking for names (please, I need them). As for majors:

Jazz-Psych (obviously)

Kyle- Liberal Arts (I wanna put him in accounting, but Liberal Arts works for now)

Tuck- Comp Sci

Danny- Poly Sci, minor in Astronomy

Sam- Double Poly Sci and Environmental Science

Val- Criminal Justice

Dash- Undecided (both me and him)

Kwan- Pre-Med for now, though he wants to do Child Development/Education

Paulina- Fashion Marketing

Star- Sports Science

Mikey- Music

Wes- Journalism

#liminal amity park#dp x dc crossover#danny fenton#paulina sanchez#dash baxter#sam manson#jazz fenton#tucker foley#valarie gray#star strong#wes weston#kyle weston#mikey#tim drake#finally some more dc#also our kids acting liminal#or at least they glow#danny drinks ectoplasm smoothies#amity park is weird#amity park/gotham co op#no beta we die like danny and jason#part 3 of idk how many still

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

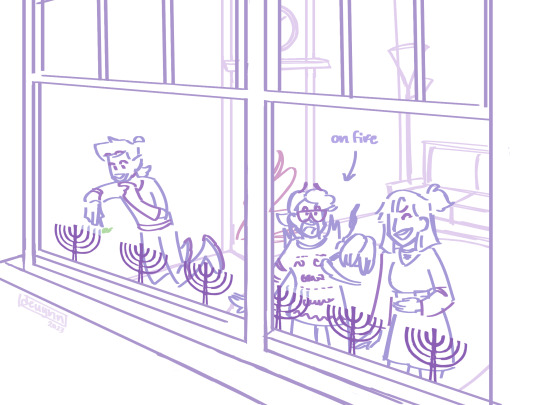

[id: two hannukah themed sketches featuring the main trio from danny phantom.

in the first, the camera is outside a window, looking into a cozy living room with the fireplace roaring. several menorahs lay on the windowsill. closer to the viewer, tucker holds a shamash and waves his hand erratically; sam laughs at him. an arrow declares that he's "on fire". further down the windowsill, danny floats in phantom form, lighting his menorah with ectoplasmic fire.

in the second, sam and danny sit on the floor, playing dreidel. tucker sits in a chair, watching them, eating a sufganiyah. there's a large pile of gelt in the pot, while sam and danny only have a couple pieces. a plate of sufganiyot and latkes sits next to danny. sam grins, ג (gimel) announcing her as the winner. danny looks at her, deadpan. end id]

happy hannukah!

#doodles#dp#danny phantom#sam manson#danny fenton#tucker foley#eight ecto nights#eight ecto nights 2023#i tried to combine as many prompts as possible bc i knew i wouldnt finish it all!#w 1 theres: fire laughter community and light#w 2 theres fried foods and games#dw sam will put him out once shes done laughing at him#casual warning that im a gentile and if i fucked up anything it was an honest mistake#dates are 12/13/23 and 12/12/23 respectively#feel iffy bout these but i dont wanna drive myself crazy so here u go#note: i did get directions confused and they are lighting the menorahs incorrectly! do not use this as an example

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

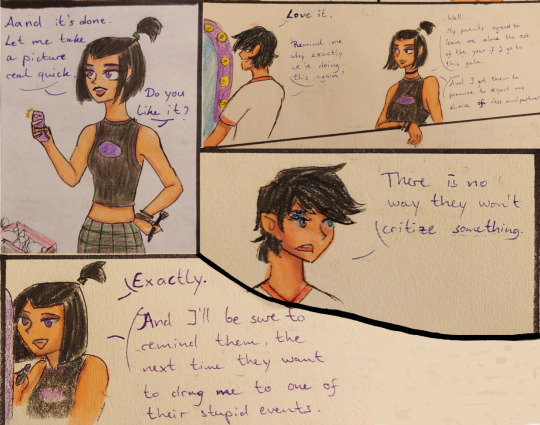

aaaaah I can finally share it :D

I put together a little comic for this year's EctoImplosion, which I'm soo hyped to show:

the wonderful @sherry-a-h wrote an awesome fic "Fancy Clothes and Kevlar Suits" inspired by this art, go check it out

#ectoimplosion#dp x dc#danny phantom#danny fenton#sam manson#later in the fic also:#jason todd#red hood#tucker foley#batman#bruce wayne#tim drake#red robin#probably the whole batfam#batfam#why is there so many of them???#dick grayson#nightwing#stephanie brown#spoiler#cassandra cain#orphan#damian wayne#robin#and whoever I forgot#i'm sorry#there's just too many#bats and birds#dead on main#dead on main ship

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mad scientist Fenton.

And I mean MAD.

Danny didn't have the intelligence of his mother, who was able to calculate complex things in a matter of seconds and come up with theories that would go against the nature of the very world and make them work.

He didn't have the kills of his father, who was able to take his mother's theories and bring them to, able to build complex machinery at the drop of the hat out of less than capable materials.

Nor did he have the mastery of the human mind like his sister, who could run circles around anyone if she so wanted, build them up from nothing or completely and utterly break their mind if she so chose.

But what he did have, was an understanding of the human body on par with that of his sister's mastery of the mind. What the body was capable of handling, how much he could push the body past its breaking put before it broke.

How much he could change before they could be considered more than human. Where exactly he needed to make their body betray them, and instead become subservient to him.

And yes, dear sister. Such a thing is far more profound than making their own mind betray them.

Danny wasn't human, not anymore at least. He modified himself far too much to be human, despite looking like one. Ghostly remnants run through his veins, not enough to make him anywhere near ghostly, but enough for it to matter.

Ghost and human biology were fascinating to him, really. It was so interesting to see how the plant his dear friend grew would affect them so, whether it was beneficial or harmful, it didn't matter to him, really.

Speaking of his dear friend.

Her mastery over Botany was as masterful as ever, so many different plants her power let her twist to her every whim, not to say that her power was the only reason she was as masterful as she is, her skill was nothing to scoff at.

From man-eating plants and all the way to ones capable of sentience. Last he heard of her, she even managed to bring back multiple plants from extinction, including multiple subspecies of blood blossoms!

He didn't know how she did it, and most probably never will, really.

But it was so fine to see the effects said plants had on both humans and ghosts.

His family all had varying achievements. From his dear mother and father, who broke the laws of nature to open a portal to the land of the dead with nothing but science, to his sister, who somehow managed to overcome human nature itself. To his dear friend Sam who brought back multiple different plants from extinction, and created entirely new species of plants, to his other dear friend Tucker, able to create living souls out of AIs.

All of them managed to do what should have been impossible, practically going against the laws of the world itself, in some cases.

Now he just needs something that would prove himself upon the same level as theirs, not that he really needed too, they'd love him regardless. But there was just something he should be capable of doing that would go against the very law of this world.

He just needed to figure out what.

#danny phantom#danny fenton#maddie fenton#jack fenton#jazz fenton#sam manson#tucker foley#Y'know#This was originally going to be a Dp x Dc post but I couldn't figure out a way to get Danny into the DC universe#But if he was you already KNOW boy woulda gon crazy over so many different aliens#And the Metagene#Oh yea#He also isn't a Halfa here#But he DOES have ectoplasm in his body

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

round 2 of

*not strictly a "how do you imagine you'd die" question. Can be also read as "how do you wish to die". Just know that in this 1845 expedition you WILL die, so choose wisely.

#the terror#how would you die poll - 2nd edition (a bit darker than the 1st)#they die in SO many ways#francis crozier#john bridgens#james fitzjames#tuunbaq#billy orren#thomas blanky#henry goodsir#tom hartnell#john morphin#billy gibson#solomon tozer#stephen stanley#cornelius hickey#jacko#magnus manson#mags tummy hurt when he died and he didn't deserve it#i need you all to know that 'ardently' comes from latin 'ardere' = 'to burn'

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

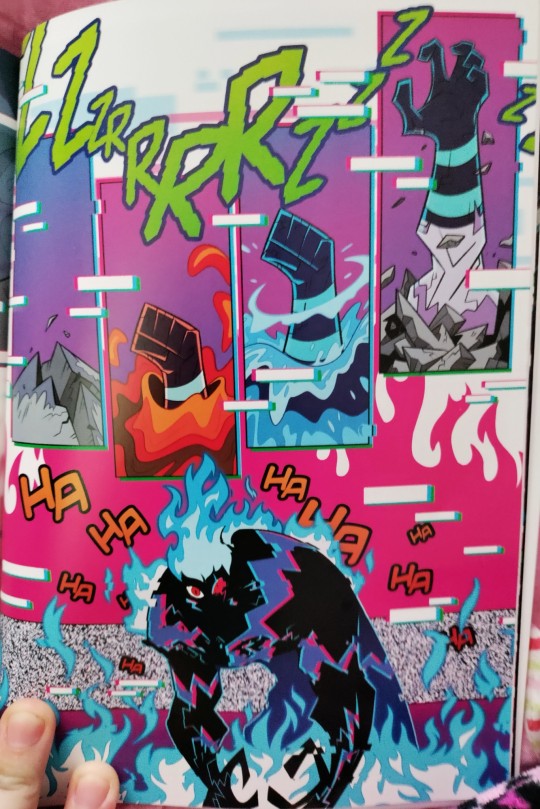

New comic :D

I started this one before the trope ones and spent months fighting with my art style to try and draw Boxy. Still unsure of how I feel about what I settled on for this but hopefully I'll get better in the future.

Dialogue and sound effects

Tucker: Are you sure this'll work?

*Bang!*

Sam: Trust me. It'll work great.

Sam: HEY BOXY!

Box Ghost: ?

Sam: I've got a box for ya!

*chatter chatter chatter* *oooooooh*

*click*

Box Ghost: NOOOOOOOOOO

*shoom*

Tucker: oh. It worked.

Sam: 'Course it did.

Danny: *phew*

Danny: Thanks guys.

*tmp*

Sam: No problem.

Tucker: Can we please leave now?

#danny phantom#art#danny fenton#tucker foley#sam manson#comic#box ghost#ive had this idea in my brain for a while and left two pages blank because i really wanted to finish it#so glad to finally be done#unsure on how well the characterization is but who cares#also#the main plot of this is that sam had the brilliant idea to put the thermos in a box#with space for the button#how many time will boxy fall for this trick#who knows#this is cropped horribly

96 notes

·

View notes

Text