#I do not know if that is necessary for such a simplistic depiction? but I would always rather play it safe

Text

#is this anything#morrissey#the smiths#heaven knows i'm miserable now#emeto tw#I do not know if that is necessary for such a simplistic depiction? but I would always rather play it safe

9K notes

·

View notes

Note

Alright, I read your recent post and need to know - what is your interpretation of Maglor’s relationship with the twins?

askjdhslkjag my biggest self-inflicted problem in this fandom is that my take on maglor, elrond, and elros' relationship is so intensely detailed and specific i am forever tormented by none of the fic i read ever quite getting it right (from my perspective; i’ve read plenty of fic that presents a good interpretation on their own terms, it’s just never mine.) it’s simultaneously way darker than the fluffy kidnap dads stuff and nowhere near as black-and-white awful as the anti-fëanorian crowd likes to paint it, it’s messy and complicated and surrounded by darkness, and yet there’s also a sincere connection within it which mostly serves to make all those complications worse. angry teenage elrond is angry for a great many reasons, and the circumstances around him being raised by kinslayers account for at least half of them. there’s lots of complexity here, and i don’t see it in fic nearly as often as i’d like

(warning: the post... feathers? i already have an internet friend called faeiri this could be awkward - anyway, the post she’s talking about includes the line ‘everyone is wrong about kidnap dads except me.’ this post follows on from that in being as much a commentary about why various popular interpretations of both how the kidnapdoption went and the way people subsequently characterise the twins just don’t work for me as it is a setting out of my own ideas. i’m not really interested in getting into discourse here, i’m just trying to get my thoughts down. i’ve read fic with these interpretations before that i’ve liked, even, don’t take this as a Condemnation, aight? also this turned out long as hell, so i’m putting it under a cut)

i can never buy entirely fluffy depictions of kidnap dads

which isn’t to say i don’t read them! sometimes all i want is something sweet, for these kids to get to be happy for once. it’s not like i think their time with the fëanorians was completely devoid of laughter

it’s just. the pet names, the special days out, the home-cooked meals, it can get so treacly it stops feeling like the characters they are in the situation they’re in and turns into Generic Found Family #272

it soaks out all the complexity - which is the thing i am here for - and acts like oh, these kids were never in any danger, they were perfectly happy being abducted by the people who murdered everyone they knew, there’s nothing possibly questionable about this relationship at all

and... yeah. that’s not the characters i know. that’s not the context i know they belong to

i just can’t forget the circumstances that led them to meet

rivers of blood, the air filled with screams, a town ablaze, a woman choosing to die. every interaction the three of them have is going to proceed from that nightmare

(sidenote: i tend to hold it was maglor that raised the twins, with maedhros looming ominously in the background not really getting involved. it’s mostly personal preference, i’ve been in and out of the fandom since before this kidnap dads thing blew up and when i joined that was a perfectly standard reading)

(also the cave thing was a dumb idea, old man, if only because it implies beleriand had streams safe enough for children to play in at that point. the way it separates the twins from the third kinslaying is also something i don’t particularly vibe with)

probably my least favourite angle i’ve seen on the situation (edged out only by ‘maglor was actively abusive towards the twins’ which no no no no no no no no NO) is the idea that maglor (and/or maedhros, append as necessary) took the twins specifically to raise them

like, i get where it’s coming from, but it makes maglor come off as really creepy

(i have read fics where it is indeed played off as really creepy, but that’s not a maglor i have any interest in reading about)

(’mags 100% bad’ is just as facile a take to me as ‘mags 100% good’)

even if you’re saying maglor took them in because they had no one left to take care of them - i highly doubt they were the only children the fëanorians orphaned at sirion. idk, it always makes maglor seem much less sympathetic than i think it’s meant to

i prefer to think of it as more... organic? something that evolved, not something that was preordained. them growing closer gradually, the twins finding an adult who might maybe be on their side, maglor becoming invested in them almost by accident

and then the twins are so comfortable with the second scariest monster in amon ereb they frequently sass him off and maglor’s gotten so used to not hurting them he’s not even thinking about it any more. no one’s quite sure how it happened, but they’ve made a Connection

‘wait aren’t they a murderous warlord of questionable mental stability and a pair of terrified small children who’ve lost everyone they ever knew? isn’t that kinda fucked up?’ yup! that’s the point! complexity!

another idea i don’t like is the idea that maglor was an objectively better parent to the twins than eärendil or elwing

other people have talked about this already, i won’t rehash the whole thing. i will say that while i don’t think elwing was a perfect parent - someone so young, in such a horrible situation, i wouldn’t blame her for screwing up - i do think she (and eärendil) did the best by them they possibly could

this is one of the few things they have in common with maglor

something i come across now and again is the idea that sure, elwing and eärendil weren’t abusive or horrible or anything, but they were a couple of basically-teenagers with so many other responsibilities, there was only so much they could do. maglor, on the other hand, is an experienced adult who could take much better care of the twins

and...

first off, it’s not like mags doesn’t have a job. he’s a warlord, he has a fortress to help run, military shit to handle, lots of other stuff that needs to get done to stop everyone from starving or getting eaten by orcs. i feel like sirion had enough of a government there was plenty of opportunity for elwing to take days off and play with her kids, but in the fëanorian camp nobody really has the time to chase after a couple of toddlers, least of all one of the last points on the command network. they just don’t have the people any more

(seriously, the twins getting a formal education with tutors and classes and shit is a weirdly specific pet peeve of mine. this is a band of renegades, not a royal household; if there’s anyone left with those kinds of skills they almost certainly have more important things to do)

more than that, though - well, a quick glance through my late stage fëanorians tag should tell you a lot about what i think maglor’s mental state is like at this point. he is so accustomed to violence death means nothing to him, he’s lost most of his capacity for genuinely positive emotion to an endless century of defeat and despair, he hates everything in the universe, especially himself, he’s only able to keep functioning through a truly astounding amount of denial, and he covers it all up with a layer of snark and feigned apathy, which he defends aggressively because he’s subconsciously realised that if it breaks he’ll have absolutely nothing left

(maedhros, for the record, is... i’d say more stable, but at a lower point. maglor may interact with the world mostly through cold stares and mocking laughter, but at least his mind is firmly rooted in the present)

(on the other hand, at least maedhros lets himself be aware of what they are and where their road will lead)

which... this doesn’t mean maglor doesn’t try to be kind to the twins, or rein in his worst impulses around them

there’s just so little of him left but the weapon

he stalks through the halls like a portent of death and gets into hours-long screaming matches with maedhros and has definitely killed people in front of the twins

not even as, like, a deliberate attempt to scare them, but because when you solve most of your problems by stabbing them it’s pretty much a given that people who spend a lot of time around you are going to see you do it at least once

and sometimes, he curls up in an empty hallway, and weeps

... suffice it to say i don’t think elwing’s the more preoccupied, or the less mentally ill, parent here

just. in general, the fëanorians aren’t cackling boogeymen, but they’re not particularly nice either

no one has the energy left for that. not these isolated and weary soldiers at the end of a long losing war and the beginning of the end of the world. they don’t really bother to guard the kids against them escaping. where else are they going to go?

the sheer despair that must have been in the fëanorian camp after sirion, the knowledge that the cause cannot be fulfilled, that they are utterly forsaken, that they’re really just waiting to die -

it can’t have been a happy place to grow up in, under the shadow of loss and grief and deeds unrepentable, and the slow march of inevitable defeat

they would have had a better childhood if they stayed in sirion, raised by people who knew how to hope

but that isn’t the childhood they had. and despite everything i’ve said, i don’t think that childhood was an entirely awful one

yeah, see, this is where the other side of my self-inflicted fandom catch-22 comes in. just as much of the pro-kidnap dads stuff comes off as overly saccharine and simplified to me, i find much of the anti-kidnap dads stuff equally simplistic in the opposite direction

the idea that maglor and the fëanorians never meant anything to elros and elrond, that they had no effect on the people they became at all, that it was just a horrible thing that happened when they were children, easily thrown in the rear-view mirror...

that’s even more impossible to me than the idea that life with the fëanorians was 100% fluffy and nice

like, i’ve seen the take that elros and elrond hated the fëanorians from start to finish. they were perfect little sindarin princes, loyal to their people and the memory of doriath, spurning every scrap of kindness offered to them and knowing just what to say to twist the knife into the kinslayers’ wounds

... dude. they were six. hell, given their peredhelness, mentally they could easily have been younger

what six year old has a firm grasp of their ethnic identity? what six year old is fully aware of their place in history? what six year old would understand the politics that led to their situation?

don’t get me wrong, i can see hatred in there. but something else that doesn’t get acknowledged alongside it often enough is the fear

some of the stuff i’ve read feels like it gives the kids too much power in the situation. they’re perfectly happy to talk back to and belittle the people who burned down their hometown and killed everyone they ever knew, like miniature adults who don’t feel threatened at all

and, like, six. i can see them going for insults as a defensive measure, but it is defensive. it’s covering up fear, not coming from secure disdain

(and a lot of those insults sound, again, like things an adult who’s already familiar with the fëanorians would say, not a scared child who’s lost almost everything. why would a six year old raised by sindar and gondolindrim know what the noldolantë is, let alone what it means to maglor?)

(... i’m just ranting about this one fic that’s been ruffling my feathers for five years straight now, aren’t i)

i mean, i write elrond as the world’s angriest teenager, who snipes at maglor pretty much constantly, but the thing about angry teenage elrond is that he’s angry teenage elrond

he’s spent long enough with the fëanorians he has a pretty secure position within the camp, and he knows that maglor won’t hurt him from a decade and change of maglor not, in fact, hurting him

but as a small and terrified child abducted by the monsters his mother had nightmares about? he fluctuated wildly between ‘randomly guessing at things to say that wouldn’t get him killed’ ‘screaming at maglor to go away in words rarely more complicated than that’ 'desperately trying not to do or say anything in the hopes of not being noticed’ and ‘hiding’

(and i don’t think the twins were never in any danger from the fëanorians, either. quite besides the point that before they started orbiting maglor nobody was really sure what to do with them... well, they wouldn’t be the first children of thingol’s line the minions took revenge on)

(fortunately for them, maglor did, in fact, take them under his wing. by this point even their own followers are shit scared of the last two sons of fëanor, nobody’s going to mess with their stuff and risk getting mauled. tactically, it was a pretty good decision for a couple of toddlers)

more to the point, i feel like a child that young, in a situation that horrible, wouldn’t reject any kindness they were offered, any soothing touch in a universe of terror

in a world full of big scary monsters, the best way to survive is to get the biggest scariest monster possible to protect you. that’s how elros rationalises it when they’re, like, eight, mentally, but at the time they were just latching on to the only person around them who seemed to care about them

that’s how it started, on their end. two very young very scared children lost in a neverending nightmare clinging tightly to the lone outstretched pair of hands

as for maglor...

i’ve called mags evil before, but i see that as more of a... technical term? he is evil because he did the murder, he remains evil because he won’t stop doing the murder. hot take: murder bad

but that doesn’t make him, like, a moustache-twirling saturday morning cartoon villain. he is deeply unhappy with the position he’s in and the person he’s become, and he’s always trying not to take that final step over the edge

it’s not that i can’t see a maglor who is abusive or manipulative or who sees the twins more as objects than people. it’s just that that characterisation is one i am profoundly uninterested in. i do occasionally read fic with it, but it never enters my own headcanons

horrible people can do good things!! kinslayers can do good things!! the fallen are capable of humanity!! people can do both good and evil things at the same time, because people are complicated!! maglor is not psychologically incapable of actually taking pity on these kids!!!!

it’s... again, complexity. the fëanorians straddle the line between black and white, which is a lot less sharp in the legendarium than it’s sometimes characterised as. it’s what draws me to their characters so much, why i have so many stupid headcanons about them. pretending they fall firmly on either side of the line is my real fandom pet peeve

and, like, this moment? this sincere connection between a bloodstained warlord and two children who will grow up to be great and kind in equal measure? i may not entirely like the direction the fandom’s taken it recently, but that beat, that relationship, it still gets me

so no, i don’t think elrond and elros’ years with the fëanorians were an endless cavalcade of abuse and misery. i think there was love there, despite the darkness all around them

an old, tired monster, and the two tiny children it protects

maglor never hurts the twins, not ever, not once. his claws are sharp and his fangs are keen, if he so much as swatted them he’d rip them in half. instead he folds down the razor edges of his being, interacting with them ever so carefully. he has nightmares of suddenly tearing into their skin

seriously, the power differential between them is so great, maglor so much as raising his voice would break any trust they have in this horribly dangerous creature. fics where he does corporal punishment always get the side-eye from me

the mood of their relationship is... i find it hard to put into words. melancholy, maybe, like a sunny afternoon a few days before the end of the world. three people who’ve lost so much finding what respite they can in each other as the world slowly crumbles around them

there are times when it feels like the three of them exist in a world of their own, marked out by the edges of the firelight. maglor telling stories of the stars, elros giving relaxed irreverent commentary, elrond getting a few moments to just be, all their troubles kept at bay

they are the last two lights in a world sunk into darkness, the last two living beings he does not on some level hate. he will tear his own heart out before he sees them in pain

he teaches them to ride, he teaches them to read, he gives them everything he still has left. the twins should never have been in this situation, maglor probably isn’t entirely fit to take care of them, but it is what it is, and they take what love they can

(maglor depends on the twins emotionally a bit more than any adult should rely on any child. he’s still very much the caretaker in their relationship, but that relationship is the only one he has left that’s not stained by a century of rage and grief. he’s obsessed with them, maedhros tells him frequently. maglor’s standard response to this is to try to gouge maedhros’ eyes out)

(that particular darker side to their relationship, where maglor’s attachment to the twins turns into a desperate possessiveness - that’s not something i think i’ve ever seen in fic. which is a shame, it feels much closer to my own characterisation than the standard ways this relationship gets maleficised. darker, in a different way than usual. horribly compelling in its plausibility)

however you want to read it, i don’t think you can deny this is a relationship that defines elrond and elros’ childhood. they were raised in the woods by a pack of kinslayers, the text is quite clear on this

but i’ve seen a lot of talk about how elros and elrond are only sirion’s children. they are completely 100% sindarin, they love and forgive eärendil and elwing thoroughly and without question, they identify with doriath over - even gondolin, let alone tirion. the fëanorians - the people who raised them - had zero effect on the people they grew into and the selves they created

and that, more than anything else, i find utterly unbelievable

look, i get what this is a reaction to. a lot of the kidnap dads stuff paints the fëanorians as elrond and elros’ ‘real’ family, and i’ve already talked about what i think of the idea that maglor-and-possibly-also-maedhros were better parents than eärendil and elwing. i think it’s reductive and overly optimistic and just a little too neat

but to say instead that elrond and elros held no great love in their hearts for maglor, no lingering affinity with the fëanorians, no influence on their identity from the people they grew up around, none at all? that after it happened they just left it behind and resumed being the same people they were in sirion?

that strikes me as just as much an oversimplification. it sands down all the potential rough edges of their identity, all that inconvenient complexity that stops them from fitting into any well-defined box, and replaces it with a nice safe simple self-conception i find just as flat and boring as declaring them 100% fëanorian

we can quibble over who they call ‘father’ (i personally find that whole debate kinda petty) but denying that it was actually maglor who was the closest thing they knew to a parent for most of their childhoods, and that that would, in fact, affect the way they thought of themselves and their family, elides so many interesting possibilities out of existence

(i’m not even going to get into the most braindead take i have ever heard on the subject, namely that because their time with the fëanorians was such a small fraction of elrond’s total lifespan it was like being kidnapped for two weeks as a toddler and had no greater significance than that. do you not understand what childhood is????)

like, i tend to think of elrond as a child as being very loudly not-a-fëanorian. elros is more willing to go with the flow - hey, if the creepy kinslayer wants kids, elros is happy to play into that in order to not be murdered - but elrond is very firm that he’s not happy to be here and he doesn’t belong with them

(this is after they get over their initial terror, of course, when they’ve realised they won’t be fed to the orcs for the tiniest slight. even so, elrond only really gets shirty about it around people he’s comfortable with, whose reactions he can reasonably guess at. naturally, the first person he does it to is maglor)

elros calls maglor their father exactly once, when they’re... maybe early preteens? this is because elrond hears him do it and immediately loses his shit. they have a dad, elrond says, in tears, and a mum, and any day now their real parents are going to come to pick them up and take them home

... right?

it gets harder to believe as the years roll on, as their memories of sirion fade, as they find their own places within the host, as maglor watches over them as they grow. elrond still mentally sets himself apart from the fëanorians, but it’s more of an effort every year. life in the fëanorian camp is the only one he’s ever really known. he can barely remember his mother’s voice

then the war of wrath starts, and the fëanorian host drifts closer to the army of valinor, and the twins come into contact with non-fëanorians for the first time in forever, and it becomes clear just how obviously fëanorian elrond is. he always insisted he wasn’t like the kinslayers at all, but he dresses like them, talks like them, fights like them

the myth cycles the edain tell are almost completely unfamiliar to him, he barely remembers the shape of the songs of lost doriath. even these sarcastic commentary and subversive reinterpretations he made of maglor’s stories - those were still maglor’s stories! he’s been trying to guess at the person he was meant to be, but it’s growing nightmarishly blatant how little elrond ever knew about him

instead, the people he was born to are as alien to him as the orcs of morgoth. he is a fëanorian, through and through

... yeah, elrond (and/or elros) having an absolutely massive identity crisis upon being reintroduced to his quote-unquote ‘true kin’ is another angle i’d love to see in fic that i don’t think i’ve ever come across. all those potential grey areas around who they are and who they’re supposed to be sound utterly fascinating, and i think it’s the complexity i hate to see elided over the most

i really, really doubt they could effortlessly slot back into being eärendil and elwing’s children. not when they’ve been surrounded by, lived alongside, been raised by the people who were supposed to enemies for most of their lives

they just don’t fit into that box any more. they can’t

speaking of eärendil and elwing, while i do agree that they both (especially elwing) get a lot more flak than they deserve, i don’t agree that therefore elrond and elros were never the slightest bit mad at them and fully forgave them for everything with no reservations

because, well, they were left behind. elwing had no other choice, but they were still left behind; it led to the world being saved, but they were still left behind. all the best intentions in the universe don’t erase the weeks and months and years of waiting, of a hope that grew thinner and frailer until it finally quietly broke

that’s a real hurt, and a real grievance. even if the twins rationally understand that their parents were making the best out of their terrible situation, you can’t logic away emotions like that. it’s perfectly possible for them to know they have no reason to resent eärendil or elwing, and yet still harbour that bitterness and pain

(i did write a thing once where elrond loudly rejects eärendil as his father in favour of maglor, but something i didn’t add in that i probably should have is that elrond later regretted doing that)

(not like, several centuries later, when he’d grown old and wise. two hours later, when he’d calmed down. but he was still legitimately angry at eärendil, because the one thing angry teenage elrond was not lacking in was reasons to be mad at the adults around him, and before he could figure out if he had anything less furious to say the hosts of the valar left middle-earth behind)

(it’s another element to the tragedy of the whole thing. in that particular story, which is mostly aiming for maximum pain, the only thing elrond’s birth parents know about their son for thousands of years is that he hates them)

(and he doesn’t, not really. you can’t hate someone you’ve never known)

not that i think they couldn’t ever make up with their parents! fics where elrond and his birth parents work past all the things that lie between them and form a functional familial bond despite it all give me life. i just don’t like the idea that there’s nothing difficult for them to work past

i don’t like the idea that elrond and elros would naturally, effortlessly identify with the mother they last saw when they were six and the people they only vaguely remember. i can see them doing it as a political move, i can see them going for it as a deliberate personal choice, but i can’t seeing it being immediate and automatic and easy

no matter how great a pair of heroes eärendil and elwing are, that doesn’t change the fact that to elrond and elros, they’re at most a few scattered memories and a collection of far-off stories. and so long as the twins stay in middle-earth, they’re never going to draw any closer

compared to the dynamic, multifaceted, personal, and deep bonds they have with the fëanorians - who, and i know i keep saying this but i think it gets tossed aside way more casually than it should, are the people who actually raised them, their birth parents must feel like a distant idea

and that’s why i can never buy interpretations of elrond as 100% sindarin, a pure son of doriath, with no messy grey areas or awkward jagged edges to his identity. given everything we know about his life, it seems almost cartoonishly simplistic

honestly it seems like a narrative a bunch of old doriathrin nobles trying to manouevre elrond into being high king of the sindar or something would propagate. it's neat and nice and tidy, something that’d be much more convenient for everyone if elrond did feel that way

but i just don’t see how he can. this narrative is easy and simple in a way real people never are, it ignores all the forces pulling him apart. elrond being uncomplicatedly sindarin with the life he lives and the people he's close to - that doesn’t make any sense to me

which isn’t to say i think he’s 100% noldorin, from either a gondolindrim or a fëanorian perspective. (i find it a little more believable, given, again, who he grew up around and who he hangs out with, but it’s still a bit too reductive for my tastes.) it’s also not to say i couldn’t believe an elrond who made an active choice to emphasise his sindarin heritage

it’s not how i think of him, but it works. i don’t have a problem with other people interpreting the complexities of the twins’ identities differently

i just have a problem with people acting like it doesn’t exist

in general i think there’s a lot untapped potential that gets left behind when you declare the twins, separately or together, as All One Thing

they’re descended from half the noble houses of beleriand, and they have deep personal ties to most of the rest. they belong to all of the free peoples even the dwarves, somehow, probably and i feel like that was kind of the old man’s point? so many peoples meet in them, to say they wholly belong to any one species is probably an oversimplification

they sit at a crossroads of potential identities, and rather than narrowing down their worldviews to one single path, they take the hard road and choose all of them. that’s what you need to do, if you want to change the world

and, to bring this back to my ostensible topic, in my estimation at least this mélange of possible selves does include them as fëanorians! it’s not overpowering, but it’s certainly there, and the adults they grow into long after they’ve left the host still bear influence from their childhood

nothing super obvious, nothing that wouldn’t stand out if you didn’t know what to look for, but there’s something almost incandescent in how fiercely elros reaches out for his dreams

there’s something almost defiant in elrond’s drive to be as kind as summer

as for who they publically claim as their family... honestly, it depends. while it’s usually more tactically prudent for elros to connect himself to his various human ancestors, on occasion he does find a use for his free in with the elf mafia, and elrond, code switcher par excellence, is famously the son of whoever is most politically convenient at the moment, which is rarely, but not never, maglor

(in the privacy of their own minds, well, eärendil and elwing may have been the parents elros was supposed to have, but maglor was the parent he actually had, and elros doesn’t particularly care to mope over what might have been. elrond, for his part, figures that after all the shit maglor has put him through, the least that bastard owes him is a father)

but honestly? i think before any of their mountain of identities, before thinking of themselves as sindarin or gondolindel or hadorian or haladin or fëanorian or anything, elrond and elros identify as themselves

they are peredhil, they are númenóreans, they are whoever they make themselves to be. that’s how elrond finally resolved his identity, figured out who he was and found something past the pain and the rage

he wasn’t doriathrin, or gondolindrin, or falathrin, or fëanorian, or whatever else. he was elrond, no more and no less

and that person, elrond, could be whatever he chose to be

... elros came to a similar conclusion, with much less sturm und drang that he’s willing to admit. being able to go ‘hey, i can’t possibly be biased towards any one of your cultures, because i’m descended from all of you and i was raised by murderelves’ makes it a lot easier to unite people around your personal banner, turns out

the stories other people tried to force on them shattered into pieces, and the peredhel twins were free to shape themselves into anything they could dream of

and as the new world struggles alive, these lost children of an Age of death begin to bloom into their full glorious selves -

i just. i love the poetry of that. despite every single shadow that hangs over their past, despite all the clashing notes pulling them apart, they harmonise it all into a greater, kinder theme, determined to make their world a better place in whatever way they can

they fail, of course, but so do all things. the inevitable march of entropy doesn’t diminish the long millennia they (and their descendants) held onto the light

and their growing up in the fëanorian host definitely had a huge effect on the noble lords they became. you can see it in elros’ loud ambition to create a land of happiness and hope, elrond’s quiet resolve to heal all the hurts inflicted by this marred reality

it wasn’t a perfect time by any means, but neither was it a nightmare. it was what it was, a desperate existence at the edge of a knife where, nevertheless, they were loved

even after years upon decades upon centuries have passed, it’s hard for the wise king and the honourable sage to separate out and identify all the conflicting emotions swirling around their childhood. they never knew eärendil or elwing, true, but they also never really knew maglor

not as equals, not as adults, not as people who could truly understand him. he disappeared into the fog of history, leaving only childhood memories of razor-sharp, gentle hands

it’s messy and it’s complicated and getting any real closure would be like shoving their way through a thornbush with bare hands even if elrond could find the shithead, and yet at the core of it all, there is light. not the brightest of lights, maybe, but an enduring one

that contrast, above all, that note of warmth amidst the shadows, is what fascinates me so much about their relationship. three screwed up people in a screwed up world, finding a little peace with each other

and the fact that somehow, it does have a good ending - the children grow up magnificent and compassionate and just, they become exemplars of all their peoples, lodestars of the new world born out of the ashes of the old - that makes it seem to me like this relationship must have contained some fragment of happiness

but, fuck, all the darkness that surrounds that love, all the tangled-up emotions its existence necessitates, all the prefabricated self-identities it can never slot into - nothing about it is simple, nothing about it is easy, and i find that utterly enthralling. especially how, despite everything, that flickering light never goes out

well, i don’t think it does, anyway. my take on this relationship is both complicated enough no one else ever quite gets it right and well-defined enough every single ‘error’ in other people’s interpretations sticks out like a kinslayer in rivendell

it is an entirely self-inflicted problem, i will admit. other people are allowed to interpret those complexities differently from me, and it’s entirely my own fault i lack the :waves hands around nebulously: to write my own hypothetical fic on the subject at a pace faster than glacial

still, though. i do wish there was more fic out there that engaged with these complexities. a lot of the common fandom interpretations of this relationship just sweep it all away

#ask#my terrible headcanons#elros#elrond#maglor#elwing#earendil#feanorians#niphredilien#yellow feathered faerie#putting your old url in the tags for archival purposes#post nyanyannya askbox clearout#ironically it turned out almost as long as the songfic that clogged up my askbox in the first place#and it is DONE#fuck this took forever to write#stayed up late just to get it out the door so i don't have to think about it any more#this is a long ramble and i'm pretty sure the end is just me repeating myself ad nausem sorry#i'll admit to a certain pro-feanorian bias in my interpretation#but i also don't want elros and elrond to just. live in a neverending horrorshow for decades#the silm's cruel enough we don't need that#narratively i feel like elrond being All Of The Elves is a good mirror for elros being All Of The Humans#but it didn't really fit the angle i was going for#bleck#let's see how many followers i lose for this

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawin’ Hamnds

I think another one of the reasons that tutorials for difficult things to draw like hands or faces fall short is because the artist has neglected to mention, or possibly hasn’t even noticed, that they’ve been mastering another technique alongside whatever they’re showing you. Most will talk about learning 3D forms and how easy that makes it, whatever. Sure, that’s a little important.

The skill they haven’t mentioned that is necessary is rendering. Creating a convincing illusion that this 2D object exists in space. They’ve been learning how to create the illusion of ridges, texture, dips and valleys, how value interplays with these. The Elements of Art, and how they apply to drawing hands, or eyes, or whatever (likely something they’ve been doing subconsciously).

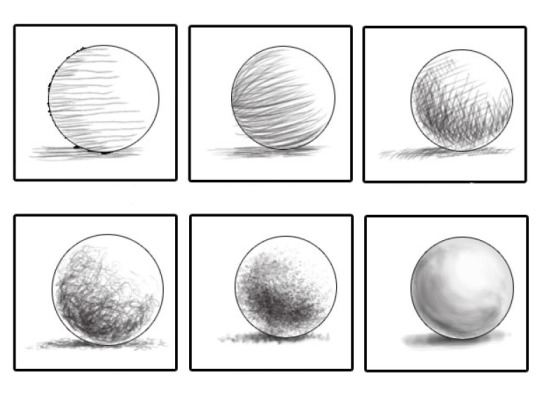

Here’s a few examples. These are all different rendering techniques. Ways to use line, shape, and value. (In digital art, “ink wash” correlates to “gradients.”)

Notice that each of these creates a different illusion of texture! They’re all depicting essentially the same value range, and are depicting spheres with light coming from the top right corner. But if I take away the names...

These could be drawings of six different objects. The bottom-right sphere immediately gives off sort of a metallic sheen, it could be a polished silver sphere. The bottom left reminds me of that scraggly texture of a tennis ball.

As an artist, we need knowledge of many different kinds of rendering techniques, in black and white, greyscale, and in color. Without these, that’s how our hands end up looking like turkey-hands.

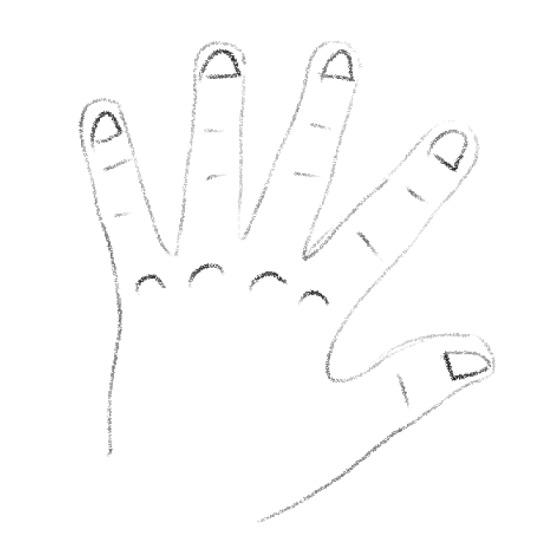

Yes that is my hand I traced on my tablet.

With only a basic knowledge of the element of Line, yes, of course this hand is going to come out wonky. (This technique here, only using line where the lines seem most “obvious,” is sometimes called the Stained Glass Technique or the Animation Cel Technique.) Hands are, despite what any artist tells you, full of weird shapes and forms that are not easily conveyed in only simple lines like this. Our eyes know this. But watch what happens when I put knowledge of different rendering techniques at work to convey texture and value.

Looks a lot more like a hand, huh! Didn’t even have to go into things like 3D shapes. With this knowledge of rendering, I can even go back and do more stylistic interpretations, using simplistic lines and implied lines in more complicated, nuanced ways than before to give the illusion of form.

See? I’ve used only some contour lines, a little hatching here and there, and shapes, to convey textures and depressions and crests in the tendons and wrinkles on my knuckles and implied lines to create the softer difference between the pink and white of my fingernails.

This is the heart of style! This is learning rendering techniques to interpret the world around you. Rendering techniques are the grammar and vocabulary of the language of art; you’re not gonna be able to communicate complicated sentences and ideas if you only know baby words!

To understand these, google search “the elements of art” and “the principles of art,” as well as “rendering techniques” There’s a ton of online classes, instructions, tutorials, examples, and videos that can help you learn all three subjects.

Learn them.

Live them.

Breathe them.

Dream them.

(Did you even notice that the hand proportions were off? :>)

#art reference#drawing reference#hand tutorial#hand reference#Steph is sick of tutorials saying it's Just That Easy with 3D shapes#it is not!!#Yes I enjoy drawing hands!#Yes I am good at drawing hands!#No hands are not easy!#not unless you learn how to render!!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let it all go

Think, speak, do.

We shine through these formed notions.

No secret we’re all the byproducts of passion. So It’s no wonder innately we excel under that pacific condition. Or feel so strongly compelled to it. Whether it’s lust, ambition or undertaking our creative outlet.

Morally people depict you differently by confessing or being earnest. Because of this, that characteristic trait has become deserted.

If you convey too much emotion, you’re weak.

Should you be ill, you’re pitied or invalidated from any struggles you accomplish or unknowingly given a farce bond.

To debate is a conflict that many believe only can be of hatred intent. Or to win with senseless ego. When often in reality it’s to be polar educated, for betterment.

Our society has pressurized this naturalness that attention of others warrants a higher value.

Appeasement to be perceived by others, will never be relevant.

Simplistically being real is what matters. We’re all diverse. Unique and special, our weaknesses they’re really strength’s awaiting you to channel them. I’d implore to seize them! All you are.

Identifying yourself is how you’ll reach an apex and find true enjoyment, happiness, your flame of passion cannot be extinguished, even when you stumble. One thing or person, will never dictate your worth.

Despite how it should feel… Confidence and openness isn’t a sin. If I could spread my abundance many times over, I would.

However this is where I introduce myself. Typically where any wisdom comes from is because of firsthand experiences. Achieved a piss-poor job in updating and letting everyone know, I’m alright, those who do care.

For them,

I lay it all here.

I’m incredibly impulsive, stubborn, and most importantly a loser.

With only one thing in common in symmetry to a pirate, I play. These things are quintessential, instead of allowing us to be defined. We’re rebellious.

In realism. Little I’ve told in life, but I’m mildly autistic. I try desperately to be more and otherwise never show, but denials don’t heal. Furthermore, I also have a rare disease, but again I am not conveying myself for sorrow or anything else. The people I have come to know here, you’re my friends alongside inspirations. You all mean a lot even though I struggle in communicating it.

Perhaps should my confession here be splayed out, It’ll hold a few understandings.

So I struggle horribly in remaining socially energized in connection with everyone that I really do, wish too.

In regards to any RPer’s that may have felt inadequate or vice-versa that I felt suddenly distant, I do apologize. But know, that I assure you, I’m the only one who’s ever felt anything but obsolete.

My passion stems because It’s required and necessary. It’s my intense obsessive tick. Within it, pain is foreign. I’ve painstakingly dealt with struggling in my learning’s, teachings, my attention span requires desire. Though, I’ve a lot of exercises.

Never did I think or sought to have gotten as many people’s time that I have had, whether their eyes, or Role-play, sharing. It’s valued and appreciated. Builds me up and no matter the amount, has gotten me back up.

I am convicted strictly to achieve one thing, to be good enough, to find and maintain that.

It’s really it. My impulsiveness is my fault, my unpredictable and lackluster energy of little sleep leaves me never the same, it’s like waking up with a reset button, often. So a majority of the time, I have to write all in one-shot.

My quality under that fluctuates, worsens, or shifts. For me, quantity more often is better than quality. Because the more repetition I practice in things, or train for it’ll cancel out being reset. I want to be able to effortlessly write quality so the more extensive the better. As I stand, I continuously never feel I can sustain or stay in one place long but that’s not in another it’s because of my inability to remain like I’m giving them my everything. Or gifting it.

I cannot ever put in real words or meaning when it matters, and I often just push away or out those who matter, I always act when it’s too late. And, due to this, I’ve failed and failed, and failed. It’s under that pressure, anxiety builds, the dam breaks, and suddenly, no matter what you set out to do or the purpose, it’s for not. Then like many in this abyss, you don’t even try anymore, or become almost weightless. Or you reunite back to where often it starts, alone. And maybe that’s just where I’m destined to perform within as recommended by the closest.

And I don’t say any of that for sympathy or edginess. This is just finding identification. Writing is the only avenue I eventually even am able to convey my truths or show my authenticity.

In us lies world’s only we witness within our minds. Only able to be written and given life by you to allow others a sharing. So I know there’s many factors that can discourage but do unleash, only you can ever bring that light.

Even should my pen ever be hollowed, I assure you my heart does roar.

With each word and thing I do, there’s a heartbeat.

So hopefully this all covers a lot of the missing tags I never got too. Thanks for the inclusions, invitations, whether FC’s, dungeons, weddings. They weren’t unseen and the inbox of asks, either chain’s or otherwise, and love, support, hell even if there’s any resentment or hate out there for me and disdain, any emotion I gladly absorb, It’s all energy. That sustains my well-being.

With all this cleansing, it’s probably better I go on reserved with RP and maybe just discontinue altogether. Outside of the long-term people or other’s who can even tolerate my insanity, I’m probably just one-shots, shorts, erotics, shipping, or hashing established out already RP. Or like in the case of few people already if there’s deep interest can just include when I do stories. Been getting few people that join Crew regarding things and I just work on giving them mentions and inclusions or figure out what they’d partake in.

Centering myself out and creating so many Crewmates and antagonists and things, gives a lot of balance. Especially with hyper imagination. Hard to ever feel empty.

Not nearly good or reliable enough, for long-term. Though I’ll keep practicing forward, I’ve managed to improve greatly compared to where I first began. With the right mindset and psyche, I’ve found there’s little I cannot conquer. In my hope’s one day, I’ll make my destination.

You gave me a beautiful world to know and hold.

Stay precious, life.

#This is just essentially a Mun - About Me#OOC stuff#Updates#Sorry for the month's gone#Soul searching courage

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baptize Me (T, 2k)

on AO3

Regulus woke, terrified again, screaming at the nightmare that would probably plague him for the rest of his life. As with every night, he was momentarily disoriented, looking around in confusion at the softly decorated room, pale walls offset by the rich raspberry furnishings. He was settling back onto the mounds of comfortable cushions littering the bed, taking deep breaths to calm himself, when the door opened and a woman with long red hair stood in the light from the landing, rubbing sleep from her eyes.

"Regulus," her voice was as comforting as the room. And familiar. "Was it the dream again?"

He swallowed his remaining fear and nodded, watching as she made her way across the room to sit on the edge of his bed, taking his hand in hers and studying his face with kind, green eyes.

"Lily," he breathed in recognition, leaning forward to wrap his arms around her, taking comfort in her steady presence. "I woke you, didn't I? You don't have to always come in here. I think you'd be doing it the rest of your life if you did."

"Yeah, well just be glad you got me and not James, he's a grumpy bugger when he's just woken up." Her laugh was light, and it added an extra glint to her eyes.

"Do you want to talk about it?" she asked him, her voice taking on a more sombre tone. "If it'll help, you know."

Regulus just shook his head. "It's exactly the same as all the other nights I've been here, Lils. I don't know why you don't just turn me out with Sirius."

"Because you've got a price on your head, silly," she says, mussing up his dark, Black family hair. "You're safest here."

He'd been there, in Godrics Hollow, staying with James and Lily Potter for about a month now, every night waking from the same dream, the same nightmare of what might have happened had Kreacher not managed to pull him out of that cave.

He had given the locket to the wizened house elf and begged him to go, to destroy it, yelling what he was sure would be his final orders as the Inferi dragged his weakened body further into the water. Kreacher had surprised him by appearing in the water beside him and dragging him through the ether, with magic unique to house elves, back to Grimmauld Place. One second, Regulus' lungs had been filling with icy water and the next, he had been coughing it up onto Sirius' old, dusty, scarlet bed cover.

"Sirius' room?" he had questioned Kreacher between his wracking coughs. "I won't be able to get out of here, the door's locked."

"No, but I will." Regulus had jumped at the sound of his brother's voice, gravelly from those muggle things he insisted on smoking. "Kreacher," he greeted the house elf cordially before thanking him for something. "I'll take him from here. And the locket too."

Sirius had wrapped a leather-clad arm around Regulus' waist and held out a hand which Kreacher dropped the locket into, then twisted on the spot, apparating them both to Godrics Hollow. There, Remus had fed him chocolate and healed the deep wound he had cut in his palm, while Lily wrapped her arms around his shoulders and James tried to get Sirius to stop pacing a hole in the carpet.

He had barely seen Sirius or Remus since then, the two of them always out on missions for the Order, reluctant to visit for fear of leading the Death Eaters to Regulus. Lily told him one evening that the intensity and frequency of the missions had increased since Regulus had found the locket. It had been destroyed by Dumbledore almost immediately, but it had also confirmed a theory he had that there were more like it out there, hidden in various objects the Dark Lord had felt an affinity with. So, the Order members had been sent off to recover them, James and Lily staying behind to protect Regulus following his defection.

Truthfully, it made him feel a little guilty because James definitely did not enjoy being cooped up in the one place. Obviously, he would have preferred an active mission with his best friends but, when Regulus broached these concerns with him, James had just clapped him on the shoulder.

"Of course I would, mate, but Lily's my number one now. Wherever she is, I will be too and right now, that is here, protecting my best mate's little brother. We're all lucky to have her, don't you think."

And that was exactly what Regulus did think. How could he not when she was here, comforting him after his nightmares yet again, willing to protect him with her life if necessary whenever the Death Eaters decided to come calling.

"Thank you, Lily," he said to her now. "I don't know what I would do without you. I always wake up just as they drag me under and then you're always here, in the doorway with your hair like fire. That's the only way to kill them you know."

"I know," she told him, voice soft as she smiled at him. "Get some rest now, Regulus. Do you want some Dreamless Sleep?"

He shook his head. "No, thank you. It makes me feel funny. I don't like being unaware."

"Alright then. I'll leave the landing light on though. Good night."

"Good night, Lily," he said as she walked out the door.

Regulus tried to get to sleep again, he really did, but after a while he found himself turning to books again to occupy his mind. He had read all the books on the shelves in his room and had finished the one he'd come to bed with. So, he slipped his feet into the slippers by the side of his bed and made his way downstairs to the living room which had bookshelves either side of the fireplace.

He noticed that one particular book had been pulled free of the others and lay flat on the front of one of the shelves. Picking it up, the red, leather-bound book was no bigger than his hand. The pages, edged in red, were so thin that they appeared almost translucent and the writing upon them was tiny, an effort to fit so many words into such a small book. Regulus finished flipping quickly through the pages and ran his thumb thoughtfully over the symbol debossed into the cover.

Making his decision, he curled his legs up under him in the large armchair with the deep, comfortable seat and pulled the crochet blanket over to cover them, intrigued by the small book. He was even more intrigued when he opened it to the title page only to find ‘Lily Evans' scrawled in childish handwriting in the top right corner.

It seemed a very strange book for Lily to have had as a child. The passages were numbered strangely and different parts of it seemed to have been written by different people. Some of the themes it dealt with were also bizarre material for a child, but it ultimately appeared to be about the same main characters. Unfortunately, even his confusion at the strange stories couldn't ward off tiredness for long and that was how Lily found him in the morning, still with her small book held loosely in his grasp.

"Regulus," she shook him awake. "Regulus, I need that book today."

"Huh," he rubbed his eyes and yawned before attempting to shake himself awake. "Oh, morning Lils. Sorry, I found it last night when I couldn't sleep."

Lily chuckled softly and Regulus noticed that she was already dressed for the day in a knee-length woollen skirt, white cotton shirt and stockings. Stockings. Now that was a far cry from the Lily he had come to know. She even had a blazer of some sort flung over her forearm.

"Yes, it probably is one of the best books to use as a sleep aid. Now come on, I need it." She held out a hand to him.

"Are you going somewhere?" He asked, thinking that was the only reason for her attire.

"Yes, somewhere I haven't been able to go for a while."

"Out?" Regulus was confused. They were safe here. Why was she going somewhere?

"Yes, out." Lily rolled her eyes at him, so he scowled and handed her the book. "You don't have to worry, Reg. I'm going to transfigure my appearance a bit. You could come too if you wanted and Remus will be there. That's the only reason I'm willing to go this week."

Regulus perked up a bit hearing Remus would be there. "Will Sirius be there too?"

Lily just smiled amusedly. "No, he doesn't hold with what we're going to do. Neither does James. He thinks it's stupid we still go."

"Go where?" Regulus scowled and quirked an eyebrow.

"I guess you could say we're going to discuss the contents of this book," she said, holding it up slightly. "It can be a great relief in burdensome times. A habit left over from my upbringing in the muggle world."

"Okay then," Regulus agreed, thoroughly intrigued. "Let me get dressed. I'll be quick."

"You'll need a muggle suit. I think there's one in the wardrobe in the spare room," she called after him as he ran up the stairs.

Twenty minutes later, Regulus was sat on an uncomfortable wooden bench in a large, single-roomed building full of muggles, wearing a muggle suit charmed to fit him and transfigured slightly to mute his distinctive looks. Lily, too, was sporting brown hair now rather than fiery red and her bright green eyes were a fairly ordinary hazel. Remus, on his other side, couldn't hide his magical scars but he had adjusted the shape of his facial features just to throw them off a bit and was now leaning forward with his elbows on the shelf in front of him that was attached to the back of another bench, hands pressed together in front of him, head bowed.

Lily was pointing out different parts of the building to him even though he couldn't understand a majority of the terms she used, but he could still appreciate the simplistic beauty of a few of the pieces, especially the windows. She had only just finished explaining who the people depicted in one of the windows were when a man in white and black robes came to stand at the front of the room, his arms raised asking for silence.

As soon as everyone began speaking in unison of sins, repentance and forgiveness, Regulus could feel a warmth starting to radiate through his chest. Then there was a sort of song called a hymn that Regulus could only mumble along to but that filled his heart with hope. It was strange really, that this meeting of people felt so different from the meetings of Death Eaters he'd been present at, even though this group also seemed to be praising a single entity. There was no fear here, no oppression. The acts of the entity that the robed man spoke of reminded him a bit of magic and he glanced curiously to Lily who smiled at him and lifted her shoulders in a shrug.

When everyone in the building bowed their heads as Remus had done earlier, Regulus followed suit and listened to the soothing voice wash over him as it spoke of the vulnerable and the downtrodden, of the lonely and the meek. He found himself joining in easily and emotion was starting to prickle the back of his throat, so much so that he couldn't keep the tune of the next hymn properly. Then, Lily pulled him up to the front of the room, towards the robed man with everyone else. He was slightly nervous now because the man had begun talking about body and blood, and Regulus had had enough bad experiences with that, but Lily reassured him it was just bread and wine, symbolising an oath, so he would just kneel for a blessing.

A blessing. Him. Regulus Black received a blessing from a muggle, and that had really put him in danger of the prickle at the back of his throat becoming tears he could barely hold back. What ended up pushing him over the edge though, just a few moments later, were the dozens of muggles, men, women and children, who grasped his hand and wished for peace to be upon him.

He didn't hear any more of the meeting after that. Not even the final hymn as the emotions had risen in him to become a river of tears that would not stop flowing. All he could do was take comfort, once again, in Lily's arms and remember this new, overwhelming feeling of peace and forgiveness that he had found.

#end of year fic countdown#regulus black#my fic#i was super proud of this one#background jily#marauders era#first wizarding war#hp fics#regulus & lily

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smuggler

“Then what are you complaining about?”

“About hypocrisy. About lies. About misrepresentation. About that smuggler’s behavior to which you drive the uranist.”

—André Gide, Corydon, Fourth Dialogue

1.

I REMEMBER MY first kiss with absolute clarity. I was reading on a black chaise longue, upholstered with shiny velour, and it was right after dinner, the hour of freedom before I was obliged to begin my homework. I was sixteen.

It must have been early autumn or late spring, because I know I was in school at the time, and the sun was still out. I was shocked and thrilled by it, and reading that passage, from a novel by Hermann Hesse, made the book feel intensely real, fusing Hesse’s imaginary world with the physical object I was holding in my hands. I looked down at it, and back at the words on the page, and then around the room, which was empty, and I felt a keen and deep sense of discovery and shame. Something new had entered my life, undetected by anyone else, delivered safely and surreptitiously to me alone. To borrow an idea from André Gide, I had become a smuggler.

It wasn’t, of course, the first kiss I had encountered in a book. But this was the first kiss between two boys, characters in Beneath the Wheel, a short, sad novel about a sensitive student who gains admission to an elite school but then fails, quickly and inexorably, after he becomes entwined in friendship with a reckless, poetic classmate. I was stunned by their encounter—which most readers, and almost certainly Hesse himself, would have assigned to that liminal stage of adolescence before boys turn definitively to heterosexual interests. For me, however, it was the first evidence that I wasn’t entirely alone in my own desires. It made my loneliness seem more present to me, more intelligible and tangible, and something that could be named. Even more shocking was the innocence with which Hesse presented it:

An adult witnessing this little scene might have derived a quiet joy from it, from the tenderly inept shyness and the earnestness of these two narrow faces, both of them handsome, promising, boyish yet marked half with childish grace and half with shy yet attractive adolescent defiance.

Certainly no adult I knew would have derived anything like joy from this little scene—far from it. Where I grew up, a decaying Rust Belt city in upstate New York, there was no tradition of schoolboy romance, at least none that had made it to my public high school, where the hierarchies were rigid, the social categories inviolable, the avenues for sexual expression strictly and collectively policed by adults and youth alike. These were the early days of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, when recent gains in visibility and political legitimacy for gay rights were being vigorously countered by a newly resurgent cultural conservatism. The adults in my world, had they witnessed two lonely young boys reach out to each other in passionate friendship, would have thrashed them before committing them to the counsel of religion or psychiatry.

But the discovery of that kiss changed me. Reading, which had seemed a retreat from the world, was suddenly more vital, dangerous, and necessary. If before I had read haphazardly, bouncing from adventure to history to novels and the classics, now I read with focus and determination. For the next five years, I sought to expand and open the tiny fissure that had been created by that kiss. Suddenly, after years of feeling almost entirely disconnected from the sexual world, my reading was finally spurred both by curiosity and Eros.

From an oppressive theological academy in southern Germany, where students struggled to learn Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, to the rooftops of Paris during the final days of Adolf Hitler’s occupation, I sought in books the company of poets and scholars, hoodlums and thieves, tormented aristocrats bouncing around the spas and casinos of Europe, expat Americans slumming it in the City of Light, an introspective Roman emperor lamenting a lost boyfriend, and a middle-aged author at the height of his powers and the brink of exhaustion. These were the worlds, and the men, presented by Gide, Jean Cocteau, Oscar Wilde, Jean Genet, James Baldwin, Thomas Mann, and Robert Musil, to name only those whose writing has lingered with me. Some of these authors were linked by ties of friendship. Some of them were themselves more or less openly homosexual, others ambiguous or fluid in their desires, and others, by all evidence, bisexual or primarily heterosexual. It would be too much to say their work formed a canon of gay literature—but for those who sought such a canon, their work was about all one could find.

And yet, in retrospect, and after rereading many of those books more than thirty years later, I’m astonished by how sad, furtive, and destructive an image of sexuality they presented. Today we have an insipid idea of literature as selfdiscovery, and a reflexive conviction that young people—especially those struggling with identity or prejudice—need role models. But these books contained no role models at all, and they depicted self-discovery as a cataclysmic severance from society. The price of survival, for the self-aware homosexual, was a complete inversion of values, dislocation, wandering, and rebellion. One of the few traditions you were allowed to keep was misogyny. And most of the men represented in these books were not willing to pay the heavy price of rebellion and were, to appropriate Hesse’s phrase, ground beneath the wheel.

The value of these books wasn’t anything wholesome they contained, or any moral instruction they offered. Rather, it was the process of finding them, the thrill of reading them, the way the books themselves, like the men they depicted, detached you from the familiar moral landscape. They gave a name to the palpable, physical loneliness of sexual solitude, but they also greatly increased your intellectual and emotional solitude. Until very recently, the canon of literature for a gay kid was discovered entirely alone, by threads of connection that linked authors from intertwined demimondes. It was smuggling, but also scavenging. There was no Internet, no “customers who bought this item also bought,” no helpful librarians steeped in the discourse of tolerance and diversity, and certainly no one in the adult world who could be trusted to give advice and advance the project of limning this still mostly forbidden body of work.

The pleasure of finding new access to these worlds was almost always punctured by the bleakness of the books themselves. One of the two boys who kissed in that Hesse novel eventually came apart at the seams, lapsed into nervous exhaustion, and then one afternoon, after too much beer, he stumbled or willingly slid into a slow-moving river, where his body was found, like Ophelia’s, floating serenely and beautiful in the chilly waters. Hesse would blame poor Hans’s collapse on the severity of his education and a lamentable disconnection from nature, friendship, and congenial social structures. But surely that kiss, and that friendship with a wayward poet, had something to do with it. As Hans is broken to pieces, he remembers that kiss, a sign that at some level Hesse felt it must be punished.

Hans was relatively lucky, dispensed with chaste, poetic discretion, like the lover in a song cycle by Franz Schubert or Robert Schumann. Other boys who found themselves enmeshed in the milieu of homoerotic desire were raped, bullied, or killed, or lapsed into madness, disease, or criminality. They were disposable or interchangeable, the objects of pederastic fixation or the instrumental playthings of adult characters going through aesthetic, moral, or existential crises. Even the survivors face, at the end of these novels, the bleakest existential crises. Even the survivors face, at the end of these novels, the bleakest of futures: isolation, wandering, and a perverse form of aging in which the loss of youth is never compensated with wisdom.

One doesn’t expect novelists to give us happy endings. But looking back on many of the books I read during my age of smuggling, I’m profoundly disturbed by what I now recognize as their deeply entrenched homophobia. I wonder if it took a toll on me, if what seemed a process of self-liberation was inseparable from infection with the insecurities, evasions, and hypocrisy stamped into gay identity during the painful, formative decades of its nascence in the last century. I wonder how these books will survive, and in what form: historical documents, symptoms of an ugly era, cris de coeur of men (mostly men) who had made it only a few steps along the long road to true equality? Will we condescend to them, and treat their anguish with polite, clinical detachment? I hesitate to say that these books formed me, because that suggests too simplistic a connection between literature and character. But I can’t be the only gay man in middle age who now wonders if what seemed a gift at the time—the discovery of a literature of same-sex desire just respectable enough to circulate without suspicion—was in fact more toxic than a youth of that era could ever have anticipated.

2.

Before the mid-1990s, when the Internet began to collapse the distinction between cities, suburbs, and everywhere else, books were the most reliable access to the larger world, and the only access to books was the bookstore or the library. The physical fact of a book was both a curse and a blessing. It made reading a potentially dangerous act if you were reading the wrong things, and of course one had to physically find and possess the book. But the mere fact of being a book, the fact that someone had published the words and they were circulating in the world, gave a book the presumption of respectability, especially if it was deemed “literature.” There were, of course, bad or dangerous books in the world—and self-appointed guardians who sought to suppress and destroy them—but decent people assumed that these were safely contained within universities.

I borrowed my copy of Hesse’s Beneath the Wheel from the library, so I can’t be sure whether it contained any of the small clues that led to other like-minded books. At least one copy I have found in a used bookstore does have an invaluable signpost on the back cover: “Along with Heinrich Mann’s The Blue Angel, Emil Strauss’s Friend Death, and Robert Musil’s Young Törless, all of which came out in the same period, it belongs to the genre of school novels.” Perhaps that’s what prompted me to read Musil’s far more complicated, beautifully written, and excruciating schoolboy saga. Hans, shy, studious, and trusting, led me to Törless, a bolder, meaner, more dangerous boy.

Other threads of connection came from the introductions, afterwords, footnotes, and the solicitations to buy other books found just inside the back cover. When I first started reading independently of classroom assignments and the usual boy’s diet of Rudyard Kipling, Jonathan Swift, Alexandre Dumas, and Jules Verne—reading without guidance and with all the odd detours and byways of an autodidact—I devised a three-part test for choosing a new volume: first, a book had to have a black or orange spine, then the colors of Penguin Classics, which someone had assured me was a reliable brand; second, I had to be able to finish the book within a few days, lest I waste the opportunity of my weekly visit to the bookstore; and third, I had to be hooked by the narrative within one or two pages. That is certainly what led me, by chance, to Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles, a rather slight and pretentious novel of incestuous infatuation, gender slippage, homoerotic desire, and surreal distortions of time and space. I knew nothing of Cocteau but was intrigued by one of his line drawings on the cover, which showed two androgynous teenagers, and a summary which assured it was about a boy named Paul, who worshipped a fellow student.

I still have that copy of Cocteau. In the back there was yet more treasure, a whole page devoted to advertising the novels of Gide (The Immoralist is described as “the story of man’s rebellion against social and sexual conformity”) and another to Genet (The Thief’s Journal is “a voyage of discovery beyond all moral laws; the expression of a philosophy of perverted vice, the working out of an aesthetic degradation”). These little précis were themselves a guide to the coded language—“illicit, corruption, hedonism”—that often, though not infallibly, led to other enticing books. And yet one might follow these little broken twigs and crushed leaves only to end up in the frustrating world of mere decadence, Wagnerian salons, undirected voluptuousness, the enervating eccentricities of Joris-Karl Huysmans or the chaste, coy allusions to vice in Wilde.

Finally, there were a handful of narratives that had successfully transitioned into open and public respectability, even if always slightly tainted by scandal. If the local theater company still performed Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, who could fault a boy for reading The Picture of Dorian Gray?

Conveniently, a 1982 Bantam Classics edition contained both, and also the play Salomé. Wilde’s novel was a skein of brilliant banter stretched over a rather silly, Gothic tale, and the hiding-in-plain-sight of its homoeroticism was deeply unfulfilling. Even then, too scared to openly acknowledge my own feelings, I found Wilde’s obfuscations embarrassing. More powerful than anything in the highly contrived and overwrought games of Dorian was a passing moment in Salomé when the Page of Herodias obliquely confesses his love for the Young Syrian, who has committed suicide in disgust at Salomé’s licentious display. “He has killed himself,” the boy laments, “the man who was my friend! I gave him a little box of perfumes and earrings wrought in silver, and now he has killed himself.” It was these moments that slipped through, sudden intimations of honest feeling, which made plowing through Wilde’s self-indulgence worth the effort.

Then there was the most holy and terrifying of all the publicly respectable representations of homosexual desire, Mann’s Death in Venice, which might even be found in one’s parents’ library, the danger of its sexuality safely ossified inside the imposing façade of its reputation. A boy who read Death in Venice wasn’t slavering over a beautiful Polish adolescent in a sailor’s suit, he was climbing a mountain of sorts, proving his devotion to culture.

But a boy who read Death in Venicewas receiving a very strange moral and sentimental education. Great love was somehow linked to intellectual crisis, a symptom of mental exhaustion. It was entirely inward and unrequited, and it was likely triggered by some dislocation of the self from familiar surroundings, to travel, new sights and smells, and hot climates. It was unsettling and isolating, and drove one to humiliating vanities and abject voyeurism. Like so much of what one found in Wilde (perfumed and swaddled in cant), Gide (transplanted to the colonial realms of North Africa, where bourgeois morality was suspended), or Genet (floating freely in the postwar wreckage and flotsam of values, ideals, and norms), Death in Venice also required a young reader to locate himself somewhere on the inexorable axis of pederastic desire.

In retrospect I understand that this fixation on older men who suddenly have their worlds shattered by the brilliant beauty of a young man or adolescent was an intentional, even ironic repurposing of the classical approbation of Platonic pederasty. It allowed the “uranist”—to use the pejorative Victorian term for a homosexual—to broach, tentatively and under the cover of a venerable and respected literary tradition, the broader subject of same-sex desire. While for some, especially Gide, pederasty was the ideal, for others it may have been a gateway to discussing desire among men of relatively equal age and status, what we now think of as being gay. But as an eighteen-year-old reader, I had no interest in being on the receiving end of the attentions of older men; and as a middle-aged man, no interest in children.

The dynamics of the pederastic dyad—like so many narratives of colonialism —also meant that in most cases the boy was silent, seemingly without an intellectual or moral life. He was pure object, pure receptivity, unprotesting, perfect and perfectly silent in his beauty. When Benjamin Britten composed his last opera, based on Mann’s novella, the youth is portrayed by a dancer, voiceless in a world of singing, present only as an ideal body moving in space. In Gide’s Immoralist, the boys of Algeria (and Italy and France) are interchangeable, lost in the torrents of monologue from the narrator, Michel, who wants us to believe that they are mere instruments in his long, agonizing process of self-discovery and liberation. In Genet’s Funeral Rites, a frequently pornographic novel of sexual violence among the partisans and collaborators of Paris during the liberation, the narrator/author even attempts to make a virtue of the interchangeability of his young objects of desire: “The characters in my books all resemble each other,” he says. He’s right, and he amplifies their sameness by suppressing or eliding their personalities, dropping identifying names or pronouns as he shifts between their individual stories, often reducing them to anonymous body parts.

By reducing boys and young men to ciphers, the narrative space becomes open for untrammeled displays of solipsism, narcissism, self-pity, and of course self-justification. These books, written over a period of decades, by authors of vastly different temperaments and sexualities, are surprisingly alike in this claustrophobia of desire and subjugation of the other. Indeed, the psychological violence done to the male object of desire is often worse in authors who didn’t manifest any particular personal interest in same-sex desire. For example, in Musil’s Confusions of Young Törless, a gentle and slightly effeminate boy named Basini becomes a tool for the social, intellectual, and emotional advancement of three classmates who are all, presumably, destined to get married and lead entirely heterosexual lives. One student uses Basini to learn how to exercise power and manipulate people in preparation for a life of public accomplishment; another tortures him to test his confused spiritual theories, a stew of supposedly Eastern mysticism; and Törless turns to him, and turns on him, simply to feel something, to sense his presence and power in the world, to add to the stockroom of his mind and soul.

We are led to believe that this last form of manipulation is, in its effect on poor Basini, the cruelest. Later in the book, when Musil offers us the classic irony of the bildungsroman—the guarantee that everything that has happened was just a phase, a way station on the path of authorial evolution—he explains why Törless “never felt remorse” for what he did to Basini:

For the only real interest [that “aesthetically inclined intellectuals” like the older Törless] feel is concentrated on the growth of their own soul, or personality, or whatever one may call the thing within us that every now and then increases by the addition of some idea picked up between the lines of a book, or which speaks to us in the silent language of a painting[,] the thing that every now and then awakens when some solitary, wayward tune floats past us and away, away into the distance, whence with alien movements tugs at the thin scarlet thread of our blood —the thing that is never there when we are writing minutes, building machines, going to the circus, or following any of the hundreds of other similar occupations.

The conquest of beautiful boys, whether a hallowed tradition of all-male schools or the vestigial remnant of classical poetry, is simply another way to add to one’s fund of poetic and emotional knowledge, like going to the symphony. Today we might be blunter: to refine his aesthetic sensibility, Törless participated in the rape, torture, humiliation, and emotional abuse of a gay kid.