#wwi fantasy

Text

A Peace Militia troopmaster stationed on the frontlines in 1501.

As the CEPP 2nd Army approached the Kondrian capital city of Pripal, Imperial Command grew more and more desperate. Reaching for any and all methods they could find to swell their numbers, they began reaching into the Peace Militias of their western territories. However, most Peace Militias were unsuited for frontline combat, having served as police, paramedic, and firefighting units while at home. Moving onto the frontline, Peace Militia units would see high casualties as they were unfamiliar with trench warfare, despite their uniform. However, as the CEPP 2nd moved into urban zones to fight, PM Urban Order units---formerly a branch of PM law enforcement---became valuable assets in urban combat.

On the topic of uniforms, supplies were often too thin to provide a new field coat for Peace Militiamembers. This meant that PM units would go into combat wearing their standard uniform, complete with sewn on ranks and shoulder rank pins. The purple metal and fabric made PM soldiers easier to target and kill on the battlefields. While the shoulder rank pins were usually taken off, the sewn on ranks remained.

PM units---unused to having to differentiate units, since Peace Militias often operated alone in their jurisdiction---usually stuck scraps of paper naming their militia unit on their helmet, tucked into the PM helmet bands. Even in the last months of the war, soldiers still found time to express their emotions---mostly grief---in song. The song "Unfortunate Militiamen/We Unfortunate Few" was a popular song among PM soldiers that circulated around the last months of the war.

#world building#worldbuilding#drawing#lore#low fantasy#ww1 fantasy#wwi fantasy#still don't know what i'm doing#how do i use this app#elstre#tke#true kondrian empire

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This isn't an attempt at a flex I swear and I recognize people can have different learning experience and still be intelligent even if they don't/can't read, but given my abysmal education growing up I have to wonder what would have happened to my brain if I wasn't such a voracious reader as a kid

#i read everything from fantasy to nonfiction to Shakespeare#i once proved my fourth grade teacher was abysmally wrong about WWII solely because i had just read a book about the Holocaust#just a few months prior#otherwise i and the rest of the class would have internalized her 'lesson' that hitler died in WWI and WWII was solely about pearl harbor#God only knows where that train of belief would have led us#she had no business being a teacher and yes she hated me from then on and made my school life even more miserable#like literally sending me home in tears miserable

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love setting fantasy around and after WWI. It's such a good combination. WWI was a loss-of-innocence on a societal level. There had been this assumption that technology and progress could solve all our problems and make us better people, and then WWI comes and shows us horribly and violently that it does not, and then in the aftermath we have to deal with what this means for us as a society and as people.

Throwing magic into that is a perfect thematic fit, because magic and technology are basically the same thing--people trying to impose their will upon nature. It can do good things or terrible things, but the issue is not necessarily the technology or the magic itself, but the hearts of the people using it, the cost to bring it about, the drain on resources and the effect on the environment and people. In the aftermath of a major conflict, we have to take a long hard look at ourselves and the choices we've made and will continue to make. Are the benefits worth the cost? What is the true nature of man--can we ever trust ourselves again? Have we progressed to a better stage of humanity or reverted back to beasts? There is just so much to explore there. The WWI connection has been built into the genre ever since Tolkien, and it continues to be relevant to our modern world.

#random thought of the day#adventures in writing#fantasy#wwi#history is awesome#i've been thinking about this since i reread chunks of 'the fairy's daughters' last week#i started writing that not long after 'rilla of ingleside' first sparked my wwi interest#and i didn't know nearly as much about the war back then#i managed to hit upon a core truth that makes the central story pretty compelling#like there are big issues with the story on a logic and character level#but the core thing is that the fae have cut off contact with the human realm after seeing what horrors they were wreaking with technology#but the humans distrust my half-fairy girls because they're afraid of what they can do with magic#the girls fit in nowhere#and neither side realizes they're both making the same mistake#trusting or distrusting a certain method of imposing one's will on the world#and forgetting that it comes down to the choices of the person who has access to the technology or magic#and that theme is strengthened because it's a twelve dancing princesses retelling#so the story pivots around one human man who is trusted with a powerful magical item because he has a good heart#and my explanation here is really bad#but what i'm getting at is that the history weaves together with the fantasy here in really cool ways#because the specific conflict of post-wwi lends itself really well to this magical setting#i've also got my story idea where the spanish flu is replaced with a plague that gives people animal-shapeshifting abilities#so people are literally having to grapple with their beastly natures#which plays out a different aspect of the post wwi conflict#and no matter what form it takes wwi is just a really good setting for fantasy hence the above post#that refuses to put the words in my head into sensible order#i hope maybe a little of this makes sense

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

While goofing around in Discord for a bit, I ended up writing a quick short story the other day. Thought I'd share it here.

We open with the sound of gunfire...

A scraggly little man runs through a bombed out village in the French countryside. With him, he carries nothing but the clothes on his back and the papers in his pockets. Not a weapon on him as his gun was emptied long ago, and it's weight abandoned. His appearance is just as meaningless: brown hair, brown eyes. Streaks of white trailed from his forehead to his chin where a coat of dust and dirt had been carried down by trails of sweat, all that was washed caught in the creases of his face. He couldn't have been more than 20, but his soul felt much, much older. Even as he dodged bullet after bullet with youthful ease, his worn face burned through, juxtaposing the scene into something unbelievable. None of this was believable. None of this felt real.

As the sun stretched a tired hand over the horizon and grabbed the French ruins to pull itself up, the soldier started to worry. There was nowhere to go. The German camps already knew he was here, and without the dark, it wouldn't be long until they found him. Farmland stretched for miles in almost every direction save for the east, where beyond the river, the blackened skeletons of trees stood together in naked unity. The other side was either leveled by artillery or laid with more Germans, but surely the charred posts could provide at least a minute more coverage. A minute more was all he needed.

It was towards the middle of this final sprint where the pavement began to hurt beneath his feet. His boots smacked along the cobblestone almost rhythmically, though he could feel his gait grow clumsy. **Thud. Thud. Thud.** The machine gun followed, blindly reaching its hands through the twilight in hopes of grasping something still alive and squirming. **Thud.** *RATATATATATATATAT.* **Thud.** *RATATATATATATATATAT.* A drop of sweat fell from his chin. The bridge was in view now. It wouldn't be long until-

A light. A pale blue light flashed just beyond the first few lines of trees. Like a candle or lantern it seemed to flicker with a kind of uncertainty. All at once the overwhelming racket of machine fire subsided. The sounds of his feet, the creaking of his bones, the chatter of his teeth all stopped. Even the wind seemed to stop its groans. Someone was there, and regardless of being friend or enemy, they were waiting.

So entranced by the glimmer in the wood he'd made it to the bridge before he'd even noticed, and by that time had paused… As he stared into the glowing light he realized how curious it was, and yet how terrible. And among the hubbub he'd decided how little an extra minute really meant. Robbed of all other options he jumped.

The icy waters took him gracefully. He plunged in like so many of the civilians before, and like them, he dove to touch the river's rocky bed.

The current swept him along for what felt like miles, though it was very likely less than that. Flakes of white fell into the water around him, floating at his side, catching in his hair, only to be swept away again by his continuous thrashing… he never did learn to swim... Ash, he thought. That's what it must've been. Yet it didn't crumble in the waves or disperse into finer particles. And the air was sweet of honey, not the stale smoke of the village.

When the water finally began to thin he caught onto a branch bowing over the bank and started to pull himself out and onto the shore. There he collapsed. His woolen coat was heavy enough when it was dry, while wet it was even more burdensome, and not nearly as warm. With desperate hands he clawed at his belt until he had the garment off, then cast it to the ground with a wet *slop.* Next to come were his boots. It was only then, after being relieved of the cold pressures, that he could put his mind together for a moment.

Petals, he realized. All over the ground and clumped along the river's edge. What he thought was ash in the water now appeared to be cherry blossoms. All above him the trees were in bloom, crowning the pink skies with branches black as coal and flowers soft as waves of the sea. The wind rocked them gently but sent no chill down his spine as he took up his belongings and wandered barefoot into those woods, listening as the birds warbled softly. Just one more minute, he thought. Just one minute more and he'd go back…

“Hail! What brings you to this part of the woods?”

Stunned, the soldier turned to locate the source of the call. Just a few meters away another man stood, tall and round. His torso seemed to be a cage built from intricately woven wires. The head and limbs were of similar construction but also displayed simple facial features cut from sheets of weathered brass. He wore no clothes save for a cloth wrapped around his waist. Inside his chest a morning dove rested on a crossbar, cooing gently to itself. None of this seemed to shock the soldier, he simply stared on with hollow eyes, marveling at the monument before him. It was odd, by all means, but shock in this moment would be too much.

“Have you gone mad, friend?” it continued, leaning forward with hands on its knees, moving with such human fluidity. Someone had taken the time to weld on fingernails, he noted.

“Mad? Well… more than probably.”

The brass man hummed, the bird cooed once more, thinking about what he'd just said. “Well, you should come with me to the aviary.”

#my post#my writing#story#short story#wwi#wwi writing#wwi short story#the boy in the mews#wwi fiction#isekai#yeah i guess technically this would be an isekai#tw guns#leonardo eats carrots#creative writing#fantasy short story

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

You know I have to ask about Fae boy romance

omg freckle thank you for asking this because i LOVE this project so much and talking about it makes me so happy. :)

the most basic premise is: a monster hunter tries to banish some faeries and accidentally binds one of them to him instead. (he's in over his head and needs to take a nap, it's a whole thing). the faerie he binds is obviously not pleased; he is also not pleased. the contract includes lots of forced proximity-relevant clauses and the two of them have to travel to the fae realms to undo it. there is a slow burn, enemies to grudging allies to friends to lovers, bdsm undertones and overtones, etc etc

#ask meme#thank you!!!#also world on the brink of fantasy wwi#honestly i'm so exited to fully dive into this#also im going to try for the most horrific faerie lore like dark horror nature vibes#fae boy will have some traumaaa

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

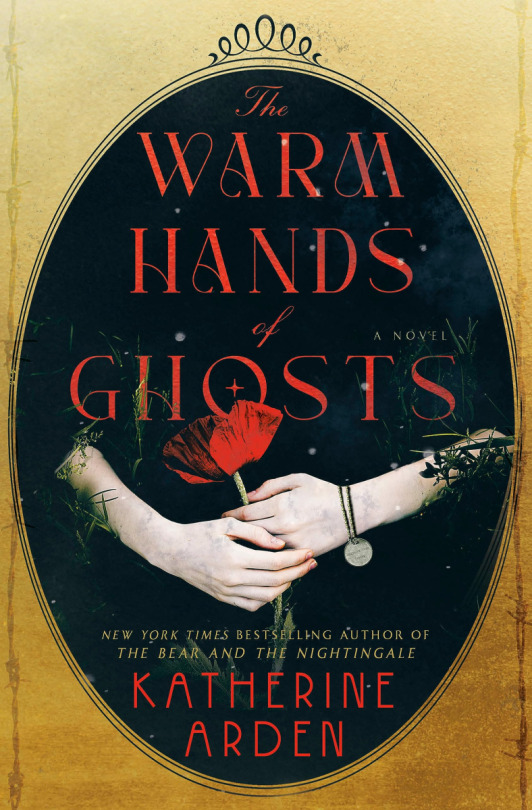

In the author's note, Katherine Arden calls the time period of WWI "darkly surreal" and I must agree, especially considering the care and knowledge the author put into this recreation of a time that is less understood by many than, of course, WWII.

A brother and a sister separated by this war. Laura is in Nova Scotia when a ship explodes, killing many, including her parents and destroying her home. Soon after, she receives a box of her brothers belongings, including his jacket and tags, a note saying that Freddie is missing and presumed dead. After some strange occurrences, Laura travels to France with a few friends to once again take up the mantel of the nurse and search for her brother.

Freddie, meanwhile, finds himself trapped and only survives with the help of a soldier from the enemy's side. To save this person, he sacrifices himself, but not in the way you may think. Will Laura find him? And, what will she risk in the process?

I have feelings!!!!! Romantic, devastating.. . This book is not just "one of my favorites"... this has to be the best book I have read in quite some time. I can not wrap my head around the author's ability to in this one book, break my heart, and then completely rebuild it. The attention to every single harmful effect of war on all different people juxtaposed with a touch of magical realism that scorched me completely... this is absolutely brilliant. I'm honestly speechless, and I know I'm going to now be searching for the next book that hits this hard, this deeply and yet has me holding onto it for dear life.

Out February 13, 2024!

Thank you, Netgalley and Publisher, for this Arc!

#book#bookish#books#bookworm#currently reading#book review#read#bookblogger#reading#fantasy#magical realism#wwi#WWI#World War I#katherine arden#the warm hands of ghosts#just read this#read this book#just listen to me for once and read this book

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So it turns out that opening the door changes history...

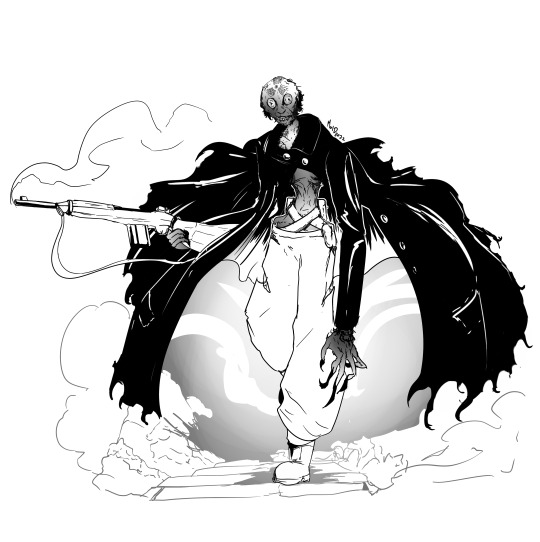

A series of commissions for Basheer Ghouse's GUNS BLAZING!

It's a Dieselpunk Alternate History setting where we opened up a path to a different dimension, and weird supernatural stuff came through to our world.

#fantasy#urban fantasy#alternate history#dieselpunk#ink#black and white#moidarts#commission#ttrpg#tabletop games#knight#guns#wwi era

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

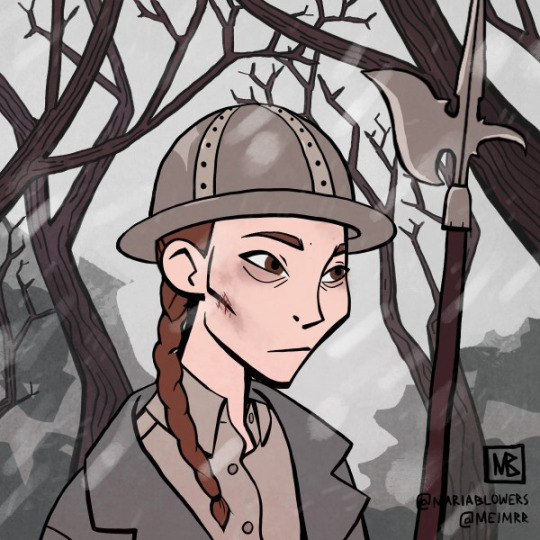

Picrew: Fantasy icon maker

This one doesn't have a name. She was conscripted into a war that never ends. As you can see, she's tired and worn out from the long winter's fight. May be depressing but I find this cathartic somehow. Are the humans fighting fairies or monsters? Does her iron helmet protect her? Iron helmets usually do that...

#war#similar to WWI#world war 1#fantasy#worldbuilding#character design#picrew#like hunger games but less glamorous

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little story

Let's be honest, I finally started using this space to have somewhere to put my writing. So have a thing.

Those Songs We Sung

Or, Fifteen Songs Arthur Sang to the Battalion and One That Was Just for Bell

I joined the battalion on January fifth, 1916. We crossed to Le Havre three days later, when I had only just managed to learn everyone’s names; if we’d been a full platoon instead of just a section and too bloody many officers, I don’t know how I would’ve managed. I certainly couldn’t’ve, even as we were, without Arthur.

When McCrae, a mundane himself but in the know about his magical soldiers, built the 17th, as an extra, magical platoon in Company D, he didn’t tell D Company’s commander we were magic. He told him the officer of the 17th would be beside not below him in the chain of command. He told him we were to be scouts for the company, instead of each platoon doing their own scouting. But he didn’t tell Hendry we were magic, and he didn’t tell him I was coming.

Hendry, mundane, brilliant, and missing a platoon commander, put Lieutenant Stone in command. Sweet, lovely Arthur, the poor mundane stuck blind under our crazy magical orders. When I arrived, I asked to keep him, instead of taking his place; part of me didn’t want him to get shipped off to another unit after spending all this time training with the 16th Battalion, part of me didn’t want to come in as the new guy replacing a friend, and part of me could do math and thought sixteen, four teams of four led by an officer or nco, made more sense than fifteen, three teams of five.

Either way, Arthur stayed, a second officer in a section that barely needed the one. I never asked McCrae why he agreed, and I never regretted it. Arthur introduced me to the lads and kept a running commentary about each until I could build profiles in my mind and keep them separate. He briefed me on the training and expectations. He told me how the lads interacted with the other platoons (polite, but distant) and how the other officers accepted our weird position (cheerfully). He warned me about the Roslin Lads (Ross, Woods, Stirling-- mischief makers, the three of them) and Nevin’s attitude (bad) and Menteith’s disposition (sensitive). He quickly became my right hand, and one of my closest friends.

And I learned within days something the rest of the platoon already knew: Arthur could sing.

All Through the Night

They had come ashore at Le Havre that morning, though by the end of the day’s journey not one of them could say where in France they were. The billets for the 16th Battalion were comfortable; D Company was in an old inn, Bell thought, and the officers had taken the ground floor, and the men were organized by section. There were, Bell was sure, more men crammed into each room than the expected capacity when this operated as an inn, but they weren’t camping like some of the other battalions.

“Your lads all find a place?” Hendry asked Bell, handing over the kettle for tea. It was nearly ten pm.

Bell nodded. “Aye, sir,” he said softly. Hendry only nominally outranked him, but Bell liked the man, and respected him. “But I can hear them from the hallways.”

“The Roslin lads’re giggling, sirs,” Sergeant Duffy contributed as he passed through the lobby. “I’ve told ‘em to pack it in, but they’re not settling.”

Hendry, who’d heard of the notorious threesome’s shenanigans, rolled his eyes. “We’re in France now; everything’s real. The lads are keyed up. I’ve heard the same from Whyte and Martin, too.”

“Not Mackenzie?” Bell asked, wondering if the fifteenth platoon’s officer would share the trick.

“I just haven’t seen him yet,” Hendry said dryly.

Bell sighed.

“The NCOs are trying to shut it down,” Hendry said. “I’m giving it another hour before I get involved and have to start discipline.” He shook his head. “I can’t blame them, but they need the sleep.”

Bell nodded in agreement of the wait. “Sounds reasonable.” Hendry was a good man, Bell thought, not for the first time.

There was a whoop from upstairs loud enough that Bell and Hendry exchanged a dry look. It was followed by a rough shout from one of the NCOs, words not audible but biting tone clear. Hendry sighed.

Whyte appeared in the doorway of the lobby. He groaned wordlessly and dropped into the seat next to Hendry.

Hendry and Bell nodded in solidarity.

“Where’s your better half, Rathbone?” Whyte asked, glancing around for Arthur.

Bell shrugged. “He headed out to the courtyard a bit ago,” he offered. “Haven’t seen him since.”

As if summoned, Arthur’s voice rang through the lobby. Hell, Bell thought, it probably rang through the whole inn. “Sleep my lads and peace attend thee, all through the night,” Arthur sang. His voice was rich and smooth and deep, and it reverberated through down to Bell’s bones.

“Guardian angels God will send thee, all through the night,” Arthur continued, and the low hum of noise drifting in the doorway lessened, and then disappeared entirely.

Bell was aware that his mouth was open unattractively, but not quite together enough to stop himself.

Hendry and Whyte both had soft grins on their faces.

Arthur was singing the lullabye slower than Bell had ever heard it, giving the lads time to settle and listen, giving them time to resign to rest and quiet. By the time he’d reached the last verse, Bell’s eyes were closed, head tipped back against his chair, and the inn was resoundingly quiet except for Arthur’s resonant voice.

“There's a hope that leaves me never, all through the night,” Arthur ended, slow and sweet. Silence reigned.

Arthur appeared a moment later in the doorway from the courtyard, and nodded tiredly at them. “Sirs,” he said; his voice had a little bit of rasp in it.

“You’re a hero, Stone, thanks for that,” Hendry said warmly, nodding at the chair next to Bell in silent invitation.

“They might even sleep now,” Whyte agreed, grinning.

“You’re gawping, Rathbone,” Hendry told Bell teasingly.

Bell was still staring at Arthur.

“Oh,” Arthur said. “He’s not heard me sing yet.” There was some pride in his voice, but mostly warmth and teasing.

“That’s right,” Whyte said. “He fit in so nicely, I forgot he’s new.”

Bell blinked a couple of times. “Holy shit,” he said finally.

Arthur laughed. “There you are, Captain.”

“You sing,” Bell said, probably stupidly. Scratch that, definitely stupidly.

Arthur’s eyes were warm. “Yes sir. Choirboy, voice lessons, and all, back in New York. It’s about as useful as my half a law degree, and I only do it in my aunt’s shop when I’m bored of late, but you don’t lose the things bashed into your knuckles with a ruler.” The rasp was getting worse, not better as he spoke.

“Seems pretty useful to me,” Hendry answered.

Bell, conscious of the eyes on Arthur instead of him, traced a spell across the bottom of his cup to rewarm the tea and silently passed over his tin mug; he’d been holding it, more than drinking anyway.

Arthur grinned at him. “You need a minute still, Captain?” He drank the tea, though.

“Probably,” Bell admitted. “Holy shit, Arthur.”

Arthur’s face went soft, a little embarrassed, a lot fond.

McManus, the company Command Sergeant Major, paused in the doorway on his way past. “All right sirs?” He asked. “Lads’ve gone quiet, if you want to turn in.”

“Thanks Tom,” Hendry said. “We may just, at that.”

“You look done in, sirs,” McManus admitted. “Twas a lovely song, Lieutenant Stone,” he added, dipped his head, and carried on.

“He’s not wrong about the rest of you,” Whyte said wryly, “And if I look half as tired as I feel, I look worse than all three of you combined. To bed, gents.”

“Bed,” Arthur agreed. “Up you come, Captain,” he said cheerfully, offering Bell a hand.

Bell felt like he had lead in his bones, but he took Arthur’s hand and groaned as he came to his feet. “Night all,” he called as he followed Arthur to the tiny room they’d been allotted.

“Night Bell,” Hendry called back. “Night Arthur.”

Arthur was humming the lullabye as they awkwardly maneuvered around each other. Between the two beds and their kits, there was approximately two feet of floor for them to stand on as they wrestled out of leathers, boots, and putties. The third time they bumped elbows, Arthur huffed a laugh. “If your arms weren’t so absurdly long,” he muttered.

Bell could admit he was still off kilter from Arthur’s song. He hummed a reply, but didn’t say anything aloud. It certainly wasn’t his usual playful tease.

Arthur looked at him. “You all right, Pup?” he asked softly. The nickname had come on day two, when Hendry had remarked about Bell ‘nipping after Arthur’s heels’. Arthur only used it in private, and it warmed Bell through every time.

Bell was too tired to wrestle his brain back from wherever it had gone when Arthur had sung, but it wasn’t a bad daze. “Fine, Arthur,” he replied, just as soft.

Arthur nodded, accepting this. As they settled into their bunks side by side, Arthur started humming again, a low rumble that chased Bell into sleep.

The Wild Rover

The billeting didn’t stay that good. Mostly, they camped. They were in the hollow of an abandoned farmyard, neat rows of tents for the men in the field, and the officers headquarters in the lee of the half-collapsed farmhouse. Their orders had them staying there for a few days, so Hendry called for a relaxation of discipline for the evening.

Most of the NCOs had settled themselves around a fire between the farmhouse and the field, tacitly offering to keep an eye on the troops as the lads drank, sang, and played cards. Bell had no hopes that the Roslin lads, at the very least, and probably Nevin and Hume as well, wouldn’t find some kind of mischief to cause, but Duffy and Crewe had assured Arthur they’d keep an eye on things. His section tended to keep casually aloof from the rest of the company--they were even camped closest to the edge of the wilderness--and he didn’t doubt that the shifters in his section (the Roslin lads, Caithness, and Sergeant Duffy) would wind up in the woods in animal form before the night was through.

Tom McManus, battalion CSM, passed Whyte, who he’d served with before, a bottle of spirits he’d produced from somewhere. He winked at Bell and Mackenzie, who were standing nearby, and wished them a good evening with a jaunty wave.

Whyte raised the bottle in cheerful salute, and herded Bell and Mackenzie back towards the little bonfire Hendry had jokingly called the Officers’ Mess. There were four logs to sit on, between the six of them, so Mackenzie wedged on beside Martin, leaving Whyte to take the empty log (and a long swig before passing the bottle on) while Bell flopped cheerfully down on the dirt next to Arthur’s legs. While the others were watching Martin and Mackenzie and the movement of the bottle, Bell flicked his fingers at the fire to keep it burning without consuming the little bit of wood they’d scavenged.

Martin elbowed Mackenzie, but didn’t shove him off when Mackenzie passed him the bottle, and Hendry greeted them (and Tom’s spirits) cheerfully. Arthur ruffled Bell’s hair fondly, his other hand accepting the bottle from Hendry. He murmured a soft greeting just for Bell.

“Oi, Rathbone,” Martin said, rounding on Bell.

Bell, his mouth still around the neck of the bottle of spirits, turned wide eyes up at Martin. He swallowed wrong, and his nose and sinuses burned fiercely as he coughed.

Whyte snorted at him as he took the bottle from Bell. “Smooth, Rathbone,” he teased.

Arthur patted his shoulder sympathetically. “Swallow, Captain,” he said mildly. “Don’t inhale.”

Eyes streaming, Bell leaned back on Arthur’s knee to look up at him, upside down. “Thanks,” he wheezed. “Never’da thought it.” Bell coughed again to clear his sinuses, and then turned to Martin. “Did you need something?” he drawled, “Or did you just want to see me breathe spirits?”

Martin laughed. “Admittedly a fine alternative,” he answered wryly. “But no, I wanted to ask what the devil is the problem with that little shite in your section?”

Bell groaned and tipped his head back against Arthur’s leg again, covering his eyes.

“Nevin,” Arthur muttered darkly.

“What’s he done now?” Bell asked the sky, despairing.

Hendry silently handed Bell the bottle again, skipping Arthur.

Bell took a long swig and then passed it back to Arthur.

“The mouth on that boy!” Martin said, almost admiringly. “He had some fine words for Macfarlane at the well earlier this afternoon.”

Bell groaned dramatically into his hands.

“He does have a mouth on him,” Arthur agreed dryly. “And a problem with authority.”

“What did Macfarlane say?” Bell asked, dreading it.

“I only overheard,” Martin said, “Didn’t get involved. Once I heard the swearing I figured he was your authority issue, so I stayed out of it.”

Bell cracked an eye to look at his companions.

Hendry, Whyte, and Mackenzie were all nodding along. Hendry, catching his glance, said, “Oh we all knew about him-- he was a legend back at Sutton Veny. Not his name, but that you’d drawn the short straw.”

“Oh no,” Arthur said, sounding gleeful. Bell covered his face again. “He likes Bell,” Arthur continued. “Listens to him, even.”

“So if I need to yell at him for mouthing off to Macfarlane, I can,” Bell said, trying to head off all the mocking sure to come. “He’ll take it from me, at least.”

“How?” Hendry asked, sounding startled.

Bell shrugged. “He was about the first person I met when I came on base. One of the sergeant-majors was hitting a recruit with a crop for bumping into him, and Nevin took offense to it. I got into the middle of it.”

“Of course you did,” Arthur muttered from behind him.

“I took charge of the recruit and Nevin, sent the sarn-major off thinking I was going to rip Nevin a new one, and once he was gone I sent the recruit to the medic, Nevin to wherever I figured he ought to be, and reported the dickhead to the base commander.”

“Of course you did,” Arthur repeated dryly. “And Nevin now thinks you’re all right, for an officer, and you’re fond of the little shit.”

“A little,” Bell admitted. “But if he was awful to Macfarlane, I’ll reign him in.”

Hendry was laughing. “You’re the one that got Angus discharged? Bless you, Rathbone!”

“Of course it was Angus,” Whyte said, and passed the bottle back to Bell in thanks. “He needed to go, so good on you.”

“Macfarlane didn’t seem to take it too personal,” Martin added. “Surprised more than anything. Your lads are usually so polite.”

“Except Nevin,” Arthur agreed. “They’re a good bunch.”

“I for one,” Hendry admitted with the air of someone confessing a secret, “Cannot wait to hear what the Roslin Lads have done this evening.”

Bell groaned and covered his face again. “Don’t remind me,” he muttered, muffled.

“It’s good for you,” Martin insisted. “Spoiled brat that you are, with such a small section of lovely, polite young men, and Arthur, of course.”

“Of course,” Bell agreed, laughing.

“Not going to protest being spoiled?” Mackenzie asked.

“Oh, no- well, I mean, I went to Eton,” Bell stuttered.

As the others dissolved into laughter, Arthur said fondly, “I don’t know what that means, and I don’t know if it’s agreement or denial.”

“Agreement,” Hendry said at the same time Whyte said, “Denial,” and then the Brits were all laughing too hard to explain.

“New question, Rathbone,” Martin said.

“Aye?” Bell asked.

“Your parents never named you Bell,” Martin observed.

“That’s not a question,” Arthur murmured.

Bell laughed. “Oh boy,” he said ruefully.

Hendry, who knew the answer to this question from Bell’s transfer paperwork, grinned.

“Where’s Bell come from, then?” Whyte asked deliberately.

“It’s a shortening,” Bell replied. “Of my given name, which is Bellerophon.”

Martin choked on the drink.

Arthur whistled.

“Bellerophon Rathbone,” Whyte said. “Did they hate you?”

Bell shrugged one shoulder. “Could be worse,” he said wryly. “My father’s name was Endymion.”

Arthur said, “What an appalling family tradition.”

Bell laughed. “Mother is already plotting my firstborn’s name, though she has yet to find a suitable mother for this hypothetical heir.”

“Never been more glad I’m not posh,” Mackenzie muttered.

“Same,” Arthur agreed.

Bell sighed, deeply put upon and Arthur ruffled his hair, tumbling his cover askew.

The sounds of cheer drifted from the fields, and they smiled at each other, the bottle moving easily around the circle, shared among friends. The teasing continued, and the conversation flowed. When music began to drift over from the men, Whyte produced his harmonica and began playing along with whoever was playing in the camp.

Arthur picked up the song immediately, grinning.

Bell perked up, twisting around so he could watch Arthur.

Arthur sang with his eyes closed, swaying slightly to the bouncing tune. “And I never will play the wild rover no more,” Arthur proclaimed. His eyes opened, eyebrows lifting expectantly.

Hendry and Martin joined in on the chorus, bellowing, “It’s no, nay, never!” in time. Mackenzie joined in on the second line, “No nay never no more!”

Bell tilted his head, listening. He joined in on the second iteration of the chorus, one verse later, with less certainty than his friends, but no less enthusiasm. He was just drunk enough to not care that he was a terrible singer.

Arthur grinned down at him, meeting his eyes as he sang what turned out to be the last verse, promising to go home and confess what he’d done, “And I never will play the wild rover no more!”

There was a whistle and some cheers from the direction of the field; Arthur’s voice and the harmonica had carried clearly to them, and received a raucous response.

But Arthur was grinning at the other officers, accepting the bottle and ignoring his distant fans, his eyes bright. “You are terrible at that, Captain,” he told Bell.

Bell nodded earnestly, grinning up at him. “Absolutely awful,” he agreed. “I’ll leave it to you.”

“Well that sucks all the joy out of teasing him about it,” Mackenzie complained.

“Come here, Captain,” Arthur said fondly, tugging at Bell’s shoulder until he turned back around and leaned back against Arthur’s legs again.

Bell let his head loll back in Arthur’s lap. “You’ve an excellent voice,” he said warmly.

“Thanks, Bell,” Arthur said. “Here,” he said, handing Bell the bottle.

Bell drank carefully, not lifting his head from Arthur’s lap, and blindly held it out in Whyte’s direction.

“You are drunk, Rathbone,” Whyte told him, enunciating carefully in the way of the just-passed-sober.

Bell nodded solemnly. “A little,” he agreed. “Don’t tell Hendry.”

“I promise,” Whyte answered, taking a drink and passing the bottle on to their grinning commander.

Hendry took his own drink, teeth gleaming in the firelight as he grinned. “Your secret’s safe with us, Rathbone,” he promised.

“There’s so much of you,” Martin observed to Bell. “How are you a lightweight?”

Bell was the tallest of the six officers, by several inches, and broader than all of them but Mackenzie, who was built like a rugby prop player.

“He’s English,” Mackenzie replied, as if this answered the question. The other Scots officers laughed as though it did.

Bell considered this idea for a long moment, and then got distracted by Arthur’s hand in his hair. Then he realized his eyes were closed, and opened them again. The world was a little blurry, but the sparks flying from the fire were fascinating. “I’m definitely drunker than I thought,” he observed after a long moment, into what appeared to be a conversation that he hadn’t noticed moving on without him.

“Definitely,” Arthur agreed, smiling fondly down at him. Arthur didn’t seem to be paying attention to the conversation either. “I think I’m going to put him to bed,” he told the others.

Bell realized Arthur meant him, and struggled to sit up straight.

Whyte, closest to him except Arthur, ruffled his hair fondly, which was not as nice as when Arthur had been petting him, but was friendly so he accepted it. “Good luck with the hangover, Rathbone,” he said, grinning.

Bell thanked him gravely, wished the others goodnight, and stumbled a little until Arthur tucked himself under his arm. When the ground refused to stay still, Bell observed to Arthur quietly as he realized it for himself, “I am very drunk.”

“I think so, yes, pup,” Arthur agreed, pouring him into his bedroll.

“Sorry,” Bell said.

“Not necessary,” Arthur answered. “I don’t mind.” He lay in his bedroll at Bell’s side and reached out to resume petting Bell’s hair.

Bell made a happy noise and leaned into the touch.

“Sweet boy,” Arthur murmured, and it was the last thing Bell remembered before falling asleep.

Danny Boy

Their intensive training over the spring had not prepared them at all for what the Somme Offensive was. And yet, the 16th Royal Scots had achieved their objective. Bell, Arthur’s shoulder against his as they stood in a quiet huddle with their men, wasn’t sure how much their presence--their magic-- had to do with that.

But they’d been relieved and sent back to the rear trenches now, and the remaining men of D company had pulled together in their sections. They’d been assigned sleeping areas, but no one had even taken their packs off before crowding close and looking to Bell for news.

“Battalion lost more than four hundred men and ten officers,” Bell reported lowly to the group of them. “Hendry’s hurt badly; Whyte’s taking command and he’s being evacuated back to Rouen.”

A chorus of prayers and well-wishes rippled quietly through them. Hendry was well-liked.

Bell continued with the litany of bad news. “Duncan’s going to lose the leg, probably surgery tonight, if the doc has the time. Carter’s lungs are ruined. They’re both going back on the next transport.”

Menteith looked away--they’d been outside his shield, but that wouldn’t stop him from feeling guilty about it, Bell knew. Rab was by far the kindest of Bell’s men, and his shields were the best Bell had ever seen: powered by his generous heart. Lennox, at his side, squeezed his wrist.

“We got what we were sent for, though,” Bell told them. “I’m proud of us for that, lads. 15th, 16th Scots are just about the only ones who made our objective last week.”

That got a murmur and some nods, but their faces were still grim. It had been a grim few days, and Bell was worried about his boys. Crewe, Duffy, and Arthur shared his concern, by the tension in their faces.

As the silence stretched and none of them knew how to break it, as the grief and the tension tightened until it was choking, as the weight on his men’s shoulders pushed them further and further down, Bell knew something had to give. He nudged Arthur with his arm, careful and subtle.

Arthur cut his eyes up at Bell.

‘Danny Boy?’ Bell mouthed. Crewe was the only one looking at them, and his eyes widened, but he nodded slightly.

Arthur raised an eyebrow.

Bell nodded once.

Arthur nodded back. Then he turned slightly to lean his back against Bell’s arm, tipped his head back on Bell’s shoulder, and closed his eyes as he started to sing. “Oh Danny boy, the pipes the pipes are calling,” he sang.

As the song went on, Bell watched his men pull closer together, Lennox’s arm around Rab’s shoulders, Caithness and Nevin gripping each other’s hands, the Roslin lads tucking their faces into each other’s necks, Aitken and Murry leaning into each other’s shoulders. Crewe had leaned into Murray as well, as the only remaining member of his team. Duffy was gripping Ross’ shoulder where Ross was hugging Sterling and Woods. Hume was a singer too, his voice not as warm or rich as Arthur’s, but his comfort singing clear; he joined in as Arthur’s voice crescendoed into “Come ye back, when summer’s in the meadow.”

From the other sections, voices joined in, here and there, but Arthur’s voice soared through the trench. Bell bowed his head, tilting slightly to rest his temple against Arthur’s hair as he let the tears roll, unchecked, down his face.

“For you will bend, and tell me that you love me,” Arthur finished, clear and sweet and sorrowful, “And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me.”

Bell wasn’t the only one crying, he was glad to see; the terrible tension had broken, and while they were all still wrecked by the last few days, at least now they were draining the poison out. They retreated to their sleeping places in small groups, talking, mourning, and processing together.

Duffy nodded politely to Bell and Arthur and shooed the Roslin Lads towards sleep. Crewe touched Arthur’s shoulder in silent gratitude, and followed Lennox and Rab.

“Thank you,” Bell said roughly.

Arthur turned silently and tucked himself into Bell’s embrace. Bell obediently wound himself around his friend, tucking his chin over Arthur’s head and winding his arms around his shoulders and chest as tightly as he could, until there was no space between them. It had been what the men had needed, and Arthur had been glad to do it, but it had taken a toll on him, too, to crack the shell of distance between them all and their grief.

Arthur’s cheek against his neck was cold despite the warm summer night, so Bell sketched a subtle warming charm on Arthur’s jacket-back, disguising the gesture as a stroke to his friend’s spine.

Arthur leaned into him, murmuring, “Hellfire, pup,” but he didn’t follow it up with anything.

“Arthur,” Bell replied, and they stood together as the stars came out.

Goodbye, Dolly Gray

Stationed in the rear trenches, there wasn’t a great deal to do, except maintain their weapons and their practice, so when word came summoning Bell to Macrae’s headquarters, Bell was pretty sure his section would be sent on a scouting mission. He left orders for Arthur and Crewe to get the men ready for a patrol, and took Duffy with him.

He took Duffy because the sergeant was a shifter like Bell, and they would get to headquarters and back faster that way. As soon as they were out of sight, Duffy traced the shape that focused his shift and took to the wing. He was some kind of hawk, though Bell didn’t recognize the species.

Their meeting was brief, and they returned the same way and transformed around a bend in the trench.

As Bell had suspected, they were to scout the area around Longueval and bring back, if possible, detailed maps of the German lines, with the best count they could make without being caught. As he and Duffy wound their way back through the trenches to their billet, they could both hear Arthur’s voice raised cheerfully in song.

“Goodbye Dolly, I must leave you, though it breaks my heart,” Arthur sang. It sounded like a few of the others might have been singing with him.

The lads were around a little stove, each of them working at some kind of repair or maintenance of their gear. Arthur, it sounded like, was in the little dugout room that was his and Bell’s sleeping place-- there was hardly room for more than their two bedrolls, so they didn’t do much more than sleep there--singing and working on his own gear.

Bell nodded to Duffy to tell the lads, and he turned into the dugout to tell Arthur.

As Bell walked in, Arthur sang, “Hark, I hear the bugle calling, Goodbye, Dolly Gray!” and made a sharp gesture with a strangely-flexed hand--two littlest fingers curled down, thumb tucked in, pointer straight and middle half-curled--and the torn leather on the strap of Bell’s pack smoothed itself together as if it had never been damaged.

There was only silence in Bell’s head, but he must’ve made a noise, because Arthur turned to look at him.

Arthur’s face turned white. “You- shit,” he muttered.

Bell’s mouth opened, and then closed. “Arthur,” he gasped.

“It’s-- Bell, pup, I--” Arthur fumbled.

“You’re magic too?” Bell demanded, finding his tongue.

“I-- yes-- wait. Too?” Arthur said.

Bell nodded eagerly, whole body thrumming with excitement. If Arthur was magic too, this would be perfect. “We’re with the 1st Magical Division,” Bell explained, bouncing up to the balls of his feet. “Just got seconded to the 34th, to support the mundane army’s efforts.”

“The whole section?” Arthur asked.

Bell nodded. “Hendry-” he fumbled. “Whyte and the others don’t know, but Macrae does.”

“I wondered why the devil Macrae built a scout section.” He shook his head wonderingly. “I’m mostly hearth,” he said. “What do you do?”

“No specialty,” Bell replied reluctantly, used to this, when meeting new officers in the magical army.

“Because you’re good at everything, or because you’re terrible?” Arthur asked, wry smile suggesting he’d already guessed the answer.

Bell sighed and admitted awkwardly, “Good.”

“No need to sound so embarrassed, pup, I’m sure it’ll be bloody useful.” As usual, the thick Scots emphasis on ‘bloody’ in Arthur’s otherwise painfully American accent made Bell smile. “What’re our orders, then?” Arthur asked.

“Scouting,” Bell answered. “Like I thought. Longueval.”

Arthur nodded. “Got a plan?”

“About half of one,” Bell answered. “Roslin lads are shifters, so’s Duffy. They’ll go to no man’s land and look for emplacements and mines. Lad’s’re weasels, and Duffy’s a hawk.” Eventually, the Roslin Lads would correct Arthur, as they did with everyone, that they were not weasels (Sterling was a stoat, Woods was a ferret, and Ross was a polecat), but that was much easier in the short run. He continued, “Caithness and I shift too, and we’ll go to the town and count the Germans. Crewe does illusions and Lennox is nearly as good, so your two teams will map the fields around the town.”

“What are you and Caithness?” Arthur asked.

“He’s a border collie,” Bell answered. “I’m a fox.” There would be time later to outline each of the lads’ specialties and strengths, and learn Arthur’s, but for now, they needed to focus on their immediate mission.

“Pup,” Arthur said fondly, taking one minute for the connection between them, unutterably glad to know that this wasn’t a secret they needed to keep from each other any longer.

Bell grinned shyly. “There’s a reason I let you keep it.”

Arthur nodded, grinning back. “Come on; let’s tell the lads.” He led Bell back out of the dugout, whistling cheerfully the same song he’d been singing.

The Water is Wide

Hearth magic, Bell had been taught at the magical branch of the Royal Military Academy, was mostly useless in war. After a month of plain rations, Caithness had taken over mealtimes, and Bell was convinced that hearth magic was actually an integral part of every war effort; if the army marched on its stomach, Caithness kept their section, at least, moving forward.

Bell returned to their billet trench and found the whole section around the stove. Sterling was telling a story, with frequent interruptions from Woods, while Ross struggled against Woods to try to get to Sterling, presumably to silence the story.

Bell arrived just in time for the punchline, which involved a goat in a henhouse, but didn’t hear enough of the story to know why it was funny. He dropped into the empty place next to Arthur--the lads had started leaving the space open at all times sometime in the spring and Bell didn’t think it was worth addressing, especially as he didn’t actually want them to stop--with a grin on his face.

Arthur was darning a sock, and Bell could see the sparkle of magic on his fingers. Bell watched curiously, ostentatiously ignoring Ross and Sterling tussling. Arthur was using real needle and thread, but his little and ring fingers on the hand with the needle were curled in what was obviously a magic-focus gesture and when Bell reached for it, he could feel the magic twining around the threads.

“Hey, that’s mine,” Bell realized, recognizing another darn near the toe that was not nearly as well done as the one Arthur was working on.

Arthur hummed absent agreement, eyes on his work. He finished his row, and then looked up at Bell. “It is, Captain,” he said. “And I’ve reinforced the other darn already, because it was coming out.”

“Thank you,” Bell said earnestly.

There was a squeal, and Menteith and Hume hastily lifted the rickety card table the two of them and Caithness were preparing dinner on up out of the way as Ross and Sterling rolled through, still scuffling. Caithness kicked them back the other direction.

Duffy, who had the unfortunate job of corralling the Roslin lads in the field, thumped Woods on the shoulder (“What did I do?”) and scruffed Sterling as he rolled on top.

Crewe caught Ross by the collar and kicked him playfully in the rear to make him let go of Sterling. “D’ye ever feel ancient?” he inquired dryly of Duffy and the officers.

“Act like my granny,” Nevin muttered snidely.

Crewe ignored him, as was usually the best recourse with Nevin if you were someone who wasn’t Bell.

Bell quirked an eyebrow at Nevin.

Nevin rolled his eyes, but subsided.

“Only around these raucous lads,” Duffy said.

“All the time lately,” Arthur agreed.

“I hadn’t till I met this lot,” Bell said. “But now, almost daily.”

Crewe and Duffy looked at Bell skeptically.

Arthur laughed warmly. “Captain, you know you’re one of the lads, right?”

Bell clutched dramatically at his chest as though Arthur had shot him. He allowed himself to topple straight out of the chair.

“Due respect, Sir,” Crewe drawled, “But you’re only proving our case.”

Bell, on the tarp they’d laid down to keep down the mud, with his head on Arthur’s boot, grinned up at them. “I accept that.”

There weren’t actually enough chairs for them, so with Bell out of his, Hume--done with his kitchen duties--slowly and carefully took Bell’s chair, watching to see if his captain was going to object.

Bell rolled over so he was sitting leaning on Arthur’s legs, and let the private take the chair. It wasn’t proper Officer Discipline, but they were hardly a proper army section.

As Menteith and Caithness started handing around supper, Bell tipped off his cap and accepted his sock back from Arthur.

“Any orders, sir?” Lennox asked Bell.

Bell, who’d been meeting with Whyte and the other officers of D company before returning for the meal, shook his head. “Whyte just wanted to check on morale, I think.”

There was another squeal from the direction of the Roslin lads, but when Bell looked, it honestly appeared that Nevin had done something to Sterling, rather than the three of them messing with each other. They were now, the four of them, hissing at each other in whispers.

“Can you lot not?” Arthur inquired dryly. Smirking, he added, “Especially today, on this the day of my birth.” Several wide, startled gazes were sent towards Arthur and Bell, and Arthur started to laugh. “You’re not subtle, lads,” he told them gently. “But I appreciate you.”

Caithness, whose magic had been sparkling in the corner of Bell’s eye since he sat down, tilted the iron skillet he was working in for Arthur’s inspection. “It’s not exciting, sir,” he said apologetically, “But it’s a sponge.”

The Roslin lads and Nevin were still pushing and hissing at each other. “Menteith should do it,” Nevin growled, the first audible words between them. “They like him better.”

“Which could be an argument for you to do it, little shite,” Crewe told Nevin fondly, the insult very nearly an endearment by now. “Make him like you better.”

Nevin flipped him off. He didn’t, he’d made it clear, care if anyone liked him. Then he glanced furtively at Bell to see if the Captain was displeased by him flipping off the nco.

Bell let him have it, smirk playing about his mouth. He thought he knew what the lads were about (Arthur was right; they weren’t subtle), and he knew Nevin would never want to claim his role in it.

Arthur chuckled, and waved imperiously at the lads as a whole. “I am going to sit here with the Captain and enjoy the evening. You lot feel free to sort yourselves, and let me know when you’re ready.”

The Roslin lads, Nevin, Menteith, Lennox, and Aitken immediately disappeared further down their part of the trench. Caithness was still working on his sponge, and Hume busied himself with cleaning up from supper.

Duffy and Crewe kicked their feet up, and Bell leaned his head back into Arthur’s lap. Arthur had produced another sock from somewhere, along with his yarn, needle, and darning egg, but he ruffled Bell’s hair fondly before resuming his mending. Soon enough he was humming, and Hume quickly joined in.

Arthur picked the words up midway through the line, Hume still just humming counterpoint. “A boat, that can carry two, and both shall row, my love and I,” he sang, easy and low.

Hume joined in with words on the second verse, and Crewe picked up the humming.

Bell closed his eyes, listening peacefully. He actually knew this song, but was too content to listen to Arthur, and knew his lacking skills well enough as well.

Arthur and Hume were in the middle of the last verse when the lads returned at a shuffle, nudging and pushing at each other, but silent in deference to the song.

“When roses bloom,” Arthur sang alone, Hume dropping back out as he scrubbed at a stubborn spot on their pot, “In winter’s gloom, then will my love return to me.”

Menteith had obviously been nominated, or lost the draw, or however they had decided. Probably Nevin had declared it, and swore at the others till they gave in. “Lieutenant?” he asked softly into the silence after the song.

“Loo-tenant,” Nevin muttered, ostensibly mocking Arthur’s accent, but the look on his face was full of fondness and mischief.

“Rab,” Arthur greeted, ignoring Nevin.

“You ready, Caith?” Rab asked Caithness.

The oldest of Bell’s men beyond the ncos (at an ancient 22), nodded cheerfully. “Your timing’s ace.” He started dishing out the sponge, the first piece going on the table before Arthur.

“Lieutenant Stone,” Rab said formally. “We’re glad you’re with us.”

“And glad you’re magic too!” Lennox called.

Arthur smiled.

“And we wanted to give you a little token, for your birthday,” Rab continued.

“It’s not much,” Aitken added.

“We’re in the arse end of France, sir, or we might’ve done something different,” Rab continued.

“And not a nice arse,” Woods called.

Rab sighed and pushed on. “So this is from all of us, and he didn’t want me to say but I’m going to anyway, it was Nevin’s idea.”

“Wasn’t,” Nevin growled. “I just said it was his birthday!”

“If you wanted me to do it, let me do it,” Rab complained. “Sir,” he said, pushing on gamely, “For you,” and he offered a newsprint-wrapped parcel.

“Thank you. All of you,” Arthur said warmly. And he met Nevin’s eyes as he said it, to clearly indicate he understood and wasn’t going to say anything more.

Nevin snarled silently.

Arthur delicately opened the paper to examine the box within.

Bell propped his chin on Arthur’s knee, watching with a little grin as Arthur carefully opened the fragile cardboard without tearing it. Bell had a front row seat to Arthur’s understatedly joyous smile.

“Lads,” he said softly. “This is lovely.”

“Sarn’t Duffy helped,” Ross offered. “He did the transformation, anyway. And Aitken did the sketch and Woods did the engraving. Lennox and Menteith got the materials for the cake, and Caithness baked.” Left unsaid, but implied, was that the Roslin lads had found whatever object had become this beautiful, delicate thing.

It was a pocket watch, with the Magical Army’s shield on the cover, and on the back, his name, the section’s full unit designation, the year, and around that, a careful stylized rendition of a fox’s head.

Arthur had tears in his eyes, so the lads scattered, taking his thanks and bailing. The ncos nodded politely to the officers before they too, left them alone with Arthur’s emotions.

“Happy birthday Arthur,” Bell said softly when the last of them had gone.

“Thanks, pup,” Arthur murmured, and tucked the pocket watch away.

“A good one?”

“In the arse end of France?” Arthur replied, chuckling. He pronounced the r in arse, just to see Bell’s nose wrinkle. “As good as it could be.”

Bell nodded. “Good,” he said softly, and rested his cheek back on Arthur’s leg.

Arthur hummed The Water is Wide and petted Bell’s hair.

Scottish Soldier

Bell and Caithness returned from a patrol of the area between the rear trenches and the front, both in their animal forms, and both their white points coated in mud.

They found the section in a grim, silent huddle, with no sign of Arthur except his voice, echoing in the trench. He was singing, “The Scottish Soldier,” Bell realized distantly.

“Fought in many a fray, and fought and won,” Arthur’s voice said, drifting from the far end of their billet.

Bell trotted, still four-footed, up to Duffy’s feet, nudged his shin with his nose, and tilted his head deliberately.

“News from Macrae,” Duffy said quietly over Arthur’s song. “Hendry didn’t make it.”

“As fair as these green foreign hills may be, they are not the hills of home,” Arthur continued, and his voice, deeply uncharacteristically, cracked on the word home.

Bell headbutted Duffy’s shin, and turned from his men to bound onwards, following the song.

“Leaves are falling, and death is calling, and he will fade away in that far land.” Arthur had tears on his cheeks as he sang to the setting sun.

Bell padded on quiet paws to stand with his shoulder against Arthur’s leg. He tilted his head into Arthur, nuzzling the only part of his friend he could reach. He briefly considered shifting, but honestly, rather thought his fur--muddy and matted as it was--might be more comforting.

Arthur, indeed, folded slowly to his knees, still singing, to sink his hand into Bell’s ruff. “So the soldier, the Scottish soldier will wander far no more, and soldier far no more. And on a hillside, a Scottish hillside, you’ll see a piper play his soldier home,” Arthur sang, and scooped Bell up.

Bell squirmed around until he could rest his muzzle in the crook of Arthur’s neck. He licked gently at Arthur’s cheek, drying his tears, and rubbed his face against Arthur, trying to comfort. His own small chest was a tangled knot of ache.

“As fair as these green foreign hills may be, they are not the hills of home,” Arthur finished, voice cracking again. Then he buried his face in Bell’s ruff, cradling the fox close.

Bell let himself lay limp in Arthur’s grasp, both wanting to offer comfort and desperately wanting it.

“Did they tell you?” Arthur asked softly.

Bell yipped a soft affirmative. And then he nodded when Arthur pulled back to frown at him.

“Macrae said he finally succumbed to his wounds. They’ll bury him in a military cemetery in Rouen.” Pressing his face back into Bell’s ruff, he muttered, “He had a wife and child.”

Bell nodded again; he’d known, vaguely, about both wife and child, though Hendry rarely mentioned either, and mostly only to praise his wife’s courage and grace. Hendry had been one of the best officers Bell had ever served under, the perfect mix of warm and stern, steady and brave and stubborn. D Company had missed him terribly in his absence, and the world was a poorer place for his loss.

Arthur knelt in the trench with Bell cradled close to his chest for a long time, and Bell rested his muzzle on Arthur’s shoulder as they mourned their captain together. It was dark before they slowly made their way back to their dugout room and their bedrolls, Bell still a fox at Arthur’s heels.

Duffy was waiting by the stove, but everyone else had retreated to bed already. Duffy nodded once at them, and stood from his chair. “Nevin took the watch, sirs,” he offered softly. “And Lennox’ll take his place at midnight.”

“Thanks, Duffy,” Arthur answered.

“Get some rest, sirs,” Duffy said.

“You too,” Arthur replied.

Bell yipped agreement.

“Aye sir,” Duffy agreed. “Goodnight, Lieutenant. Captain.”

“Goodnight, Sergeant,” Arthur answered, and led the way into the dugout.

Bell stood in the entryway, head tilted, listening to Duffy put out the stove and head to his bed, before padding across the little room to curl up in the curve of Arthur’s throat.

Arthur didn’t protest, didn’t push Bell back to his own bedroll. He curled around the fox in his bed and closed his eyes, but neither of them slept for a long while.

Auld Lang Syne

A year, Bell thought sadly. In a few days, it would be a year that they’d been in Europe. He should have been celebrating, like everyone else; for once, the officers of D company had released their separation from the men, and everyone was passing around cigarettes, alcohol, little tins of treats from home, regardless of rank. Even Nevin was being passably polite.

But Bell couldn’t settle. He’d shifted to fox form in a quiet corner and watched the revelry from afar, his heart aching.

“We’ll take a cup o’ kindness yet,” Arthur’s voice rang over the throng on the traditional song. Even at the distance, Bell could hear the Scots burr in his voice that never appeared in his spoken words, and only rarely in his songs. But he’d clearly learned this song in Edinburgh, and it rang true. “For auld lang syne!”

The whole company joined in on the chorus, raucous and cheerful and drunk. Bell chittered softly, unable to help himself.

“Ey, Captain,” Lennox said softly, looking down at Bell in surprise. “What’re you doing out here by yourself?” He was clearly tipsy, and had clearly slipped off to relieve himself, and found Bell as he returned. “I hope it’s you, sir, or else some poor fox thinks I’m a nutter.”

Bell tipped his chin up and chittered again, nodding clearly.

Lennox nodded. “Aye sir, question stands, then.”

Bell yipped.

Lennox checked the perimeter and nodded.

Bell shifted. “Lennox.”

“Captain.”

Bell smiled. “Just getting some quiet,” he reassured the younger man.

Another rousing chorus of Auld Lang Syne echoed.

Lennox nodded. “Aye, Captain, understandable. Sorry to disturb you.”

Bell shook his head, and fell in beside the private as they headed back to the revelry. “Never a disturbance, Lennox,” he promised.

Lennox flashed him a bright smile, and then peeled off to join the crowd around the Roslin Lads, who appeared to be juggling odds and ends.

Bell shook his head and wandered on.

“Happy New Year, Captain,” Nevin muttered, almost furtively, as Bell went past.

Bell just winked at him in return.

“And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere,” Arthur sang as Bell approached where he was near the fire. “And gie's a hand o' thine! And we'll tak' a right gude-willie waught, for auld lang syne.” As the unit took up the chorus again, Arthur dropped out of the song to take a long drink and flash Bell a warm grin. “Happy New Year, Bell,” he said under the noise.

“Happy New Year, Arthur,” Bell said softly.

Arthur tilted his head. “Are you all right?”

Bell paused, taking stock of himself. “Maudlin,” he decided on. “I’m fine, just… sulking.”

Arthur smiled at him, tugging him close. “You? Never,” he teased.

Bell smiled and leaned into Arthur’s side.

Lennox must have said something to the section, because over the next two hours or so, every one of them wandered amiably past and greeted the pair of them warmly, offered well-wishes, and wandered off again, at nearly perfectly regular intervals.

“Do you ever feel thoroughly monitored?” Arthur asked him wryly in an undertone as Aitken ambled away. He’d kept a steady stream of commentary and rambling, and he’d taken the lead in every conversation as people stopped to talk to them, letting Bell stay caught up in his head.

Bell chuckled softly, but didn’t reply.

As midnight neared, Arthur was pressed to sing Auld Lang Syne again, and he did so, smiling fondly. He stood from the crates they’d been sitting on, but stayed tucked close, their knees brushing and his palm warm on Bell’s nape.

Bell closed his eyes, leaning into the grounding touch, and joined in on the first chorus.

Oh Shenandoah

Neither Bell nor Arthur were particularly surprised when muffled shouting woke them in the night. They’d both had enough nightmares of their own to recognize unquiet dreams in their men. They exchanged a quiet glance, debating whether officers would improve matters or make them worse, but in the end, the desire to support won out over propriety.

When they stepped quietly into the dugout where the lads slept, they found that Aitken had lit a magelight, shining a soft yellow glow over where Rab had curled around Hume. Hume was still asleep, but his face was creased and he was muttering still.

Lennox sat cross-legged on Hume’s other side, and his fingers traced delicate patterns through the air, like an orchestral conductor. His eyes were half-closed in focus, and his fingers sparkled in the magelight as he carefully twisted and shaped Hume’s dreams to make them more pleasant.

Arthur started to sing softly, voice a low rumble. Bell didn’t recognize the song, but it was soft and slow.

“Oh Shenandoah, I long to see you, away you rolling river,” Arthur crooned. “Oh, Shenandoah, I long to see you, away, I’m bound away, across the wide Missouri.”

Bell smiled; obviously an American folk song, and the repetitive tune was quickly lulling the handful of them awake back to sleep. Aitken’s light flickered, and Bell took it over with an open-palmed sweep, his own magic a little more orange, but just as gentle.

Aitken and Rab dozed off again quickly, but Lennox continued to hold his control of Hume’s dreams for the duration of the song.

As Arthur sang, “Oh Shenandoah, I’m bound to leave you, away, I’m bound away, across the wide Missouri,” and slowed into the obvious end of the song, Lennox slowed his hands and then released the magic entirely.

Hume sighed softly, face gone lax and body relaxed between Rab and Lennox.

Arthur hummed another verse of the song as Lennox settled in for the night, and then Bell and Arthur returned to their own quarters.

“Like that one,” Bell murmured as they bedded down.

“Sweet pup,” Arthur replied. “It’s a sea song, about an Indian chief’s daughter.”

“Soothing,” Bell slurred sleepily.

Arthur huffed a soft breath, not quite a laugh, and hummed until Bell fell asleep.

Blue Bonnets Over the Border

It had been a bad day. Perhaps not the unrelenting terror and misery of the Somme, but the survivors of the 16th would remember the freezing sleet and bloody trudge of the First Scarpe for the rest of their lives.

The section hadn’t lost anyone, but D Company, and the 16th had both suffered heavy losses. The lads were huddled down in groups, leaned close and murmuring together. Duffy and Crew had slipped off to be with their friends among the ncos. Bell sat watching over his men, waiting for sleep to come; he was pretty sure it would be a long wait.

Arthur, however, couldn’t seem to settle. When he sat at Bell’s side, his leg bounced, and when he stood, his fingers tapped an intermittent pattern on his jacket. Every now and again, he hummed a scrap of tune.

Bell caught Arthur’s sleeve on one of his loops past as he paced. He swept a gaze over his--exhausted, shell-shocked, mostly settled--men and deemed them ‘well enough’. He tugged Arthur down into the chair across from him.

Arthur met his eyes ruefully, shook his head, and sat.

Bell caught Arthur’s tapping fingers. “Athur,” he murmured.

Arthur tipped his forehead into Bell’s and closed his eyes. “It’s stupid,” he muttered hoarsely.

“Nonsense,” Bell said gently.

“I can’t get the damn song out of my head.”

Bell gathered Arthur up into an embrace.

“I just-” Arthur choked off the words, his tapping fingers turning into a full-body tremor. He huffed out a soft breath, and then hummed enough notes for Bell to finally recognize the song.

Willie Duguid, the battalion piper, had played “Bluebonnets Over the Border” as they’d overtopped the trenches. The song had played as they’d entered no-man’s land, as the bullets had rained, and as the earth had shaken. As hell reigned on earth, and every one of them broke their own hearts.

Bell didn’t know the words, but he thought the tune might wind through his dreams for years to come, somehow integral to the horror of the day. He could see how for Arthur--already so musically oriented--it would haunt him.

“He didn’t finish it,” Arthur muttered against his neck.

“He’s fine,” Bell promised. He’d heard the battalion casualty reports at their evening officer’s call, and Duguid hadn’t been on the list. “Probably just had to watch his feet or his gun,” he said into Arthur’s hair. He rubbed Arthur’s back slowly.

“Finish the song, Lieutenant,” Rab said softly.

Bell and Arthur both looked at him.

Rab was in the middle of a puppy-pile of the Roslin Lads; his shields had probably saved all their lives at least once over the course of the day, and the three of them, in turn, had kept him from seeing the worst of the sights.

“Aye,” Lennox agreed, magic already sparking at his fingertips, hand flexed in his conductor’s pose. “Sing the song, sir.”

Arthur left his head on Bell’s shoulder, and his voice was rough and jagged, but he sang. His voice curled in the peculiarly Scots way of songs he’d learned in Edinburgh as he croaked out the marching song. “March, march, Ettrick and Tevot-dale, why my lads dinna ye march forward in order.”

Hume joined in, to Bell’s absolute lack of surprise, and to his actual surprise, so did Nevin.

As they sang, Lennox carefully leeched the poison out of their memories; Bell could feel the pull of it, and let him. His mind-magic was among the most focused Bell had ever seen. In the field, Lennox used it to make scouts forget they’d seen anything, or to make everyone who saw them look past, but he used it more in the camp to soothe their nightmares.

They wound through the whole song, voices quiet and only barely rhythmic, but by the end of it Bell could tell they all felt better.

Arthur, as usual, sang the last lines alone: “March! March! Eskdale and Liddesdale! All the blue bonnets are over the border!” Then he turned his face back into Bell’s neck and let the last of the tension ease from his shoulders.

“Should stay here tonight, sirs,” Aitken suggested.

“Hardly proper,” Bell said, not at all a protest.

Nevin was the only one who scoffed aloud, but it was written across most of the lads’ faces. “We’re hardly proper, sir,” Nevin said.

“Well you’re certainly not,” Caithness drawled, “Little Shite,” he added playfully, repeating Crew’s fond nickname.

Nevin flipped him two fingers, sneering, but then looked back at Bell and Arthur. “We’re sleeping out here tonight,” he said. “Want to see stars, not that dark hole. Should stay with us.”

It was certainly not proper officer’s decorum, though neither was the easy way Bell and Arthur were still leaning into each other; neither was most of the way Bell and Arthur handled the section. But the Magical Army was laxer in their divide between the officers and the men, and as a special action section Bell had more leeway to his command than most.

Silently, they exchanged a glance and decided to stay, where the sound of the others sleeping might keep the horrors at bay for one more night. They wound up tucked together in a corner, leaned together and more upright than prone. They fetched their bedrolls, though; it was bloody cold, and they weren’t mad.

Loch Lomond

Arleux had not gone much better than the Scarpe; in many ways, indeed it had gone worse. Bell’s section had been scattered in the assault, and he was still waiting to see who made it to the rendezvous.

Arthur was at headquarters, checking in with Whyte, and Crew was at D Company’s grouping, sending any lads who made their way there to Bell. There’d been no sign of Duffy yet.

Aitken and Nevin were still with Bell, and Caithness had shifted and was securing the perimeter. But Lennox, Hume, Menteith, and the Roslin lads were all still missing.

Bell stood as near as he could to Nevin without being obvious about it, since it was clear the younger man was upset, but also that he wouldn’t take kindly to Bell ‘coddling’ him.

Aitken chewed his lip, and then said absently, “Twas a helluva couple of days, sir.”

Bell nodded. “A mess, to be sure. We’ll be trying to regroup for a while yet.”

“Captain!” Crew called, trotting around the corner of the trench.

“Crew,” Bell greeted, and let some of the tension ease out of his shoulders when Lennox, Hume, and Menteith followed Crew around the corner. “Lads,” he added, relieved.

“Evening, Captain,” Hume said with some forced cheer. “Glad Crew found us; we’d never have got here without him.”

Bell nodded and welcomed his men into their huddle. “Lieutenant Stone is talking with headquarters, but we haven’t seen Sergeant Duffy or the Roslin lads yet.”

Rab murmured a prayer, and the others nodded.

Caithness trotted back on four feet, and transformed to join the group. “Everything’s quiet,” he reported.

Bell nodded to him, and stood quiet, waiting.

After a few quiet minutes, the cry of a bird of prey caught Bell’s attention, and he looked skyward, searching. A few moments later, Duffy circled down into the trench.

Bell offered his arm, and Duffy landed in a rustle of feathers. After a moment, he shifted easily. “Captain,” he said, ducking his head.

“Sergeant, you’re okay?”

“Yes sir,” he said, looking around. “The lieutenant?”

“Headquarters,” Bell answered.

“Here, actually,” Arthur said, rounding the corner. “Whyte wants us to settle in and we’ll take stock in the morning.”

Duffy still seemed to be taking a headcount. He looked grave. “Sirs,” he said. “The lads.” His voice cracked and he looked away for a moment.

Bell’s heart dropped. “Duffy,” he said softly.

Jaw clenched, eyes on a point off Bell’s shoulder, Duffy rasped, “Lost all three, sirs,” he said.

Arthur turned away, his hand over his mouth.

“They took the gun nearest the tracks,” Duffy continued, struggling to give a detached report. “I saw the whole thing from above. Sterling and Woods held the trench while Ross fragged the gun.” He shook his head, eyes closing.

Bell swallowed the lump in his throat. That gun had been hammering D Company, and they must have shifted to get behind enemy lines. “It was bravely done,” he said hoarsely.

Duffy nodded. Crew stepped up into his shoulder and leaned, and Rab walked straight into Duffy’s open arms and buried his face in Duffy’s shoulder. Rab was crying openly, and the others huddled close, grieving in their own way.

Bell looked for Arthur, who mostly tried to grieve alone, and Bell would have none of it. Arthur leaned into Bell’s embrace when Bell stepped up to his side. “Those boys,” he said roughly.

“They were together,” Bell answered. “And they saved us. They wouldn’t have wanted anything more.”

“They never talked about going home,” Nevin said. “Wasn’t anything there for them. They’d’ve been glad to die heroes.” His eyes were red, but his face was stone.

They’d been orphans, all three of them, Bell knew. Ross had made a comment once about Stirling’s terrible, finally-deceased father; the old man had refused to let Stirling join up, and Ross and Woods had refused to leave without him. They’d wound up in the 16th because of the timing of the old man’s much-anticipated demise.

“Woods had a girl,” Rab protested wetly from Duffy’s embrace.

“He told her not to wait,” Nevin argued. “Why do you think he was always singing Loch Lomond?”

“Won’t be the same without them,” Lennox said softly.

“Whose shenanigans will I complain about now?” Bell said, his own eyes wet.

“Who will tell us useless facts about weasels?” Aitken added.

“Not weasels,” Rab, Nevin, and Caithness said simultaneously. They didn’t quite laugh, but there was some wet chuckling.

There was a moment of silence as they all reflected on their fallen brothers.

“Come on Lieutenant,” Duffy said gruffly after a moment. “Sing the song for us, then.”

Arthur huffed and dried his tears on Bell’s shoulder. Then he straightened and launched into the song. “By yon bonnie banks and by yon bonnie braes, where the sun shines bright on Loch Lomond,” he started.

Hume, Lennox, Duffy, and Caithness joined in on, “Where me and my true love will were ever wont to gae, on the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond!”

By the end of the first chorus, they were all singing, wet-faced, red-eyed, and hoarse-voiced. By the end of the song, something had cracked open in Bell’s chest, and he no longer felt like he was choking.

Into the silence after the song, Duffy asked roughly, “Remember when they exchanged all the desk sergeant’s pens for sheep ribs?”

“They what?” Bell demanded.

“No one knows how,” Crew said, laughing.

“Even the one in his pocket,” Rab added.

Bell shook his head wonderingly.

“Or the time they dressed the cow in the battalion colors and brought it to formation?” Lennox offered.

“When they spiked the mess’ coffee,” Caithness offered.

“That was them?” Arthur demanded, then, ruefully, “Of course it was. They were always up to something.”

“And not a thing that would hurt anyone, and always when spirits needed lifting the most,” Crew said softly. “I wanted to strangle them more often than not, but they were good lads.”

Bell gently shooed his men into seats and to the ground, gathered in a huddle, and he and Arthur began passing around rations from headquarters. Caithness took up the stove and, as the lads continued to exchange stories of the Roslin Lads’ particular brand of mischief, started dinner.

There was no alcohol, but they had a good wake over the meal, and as dark drew on, they settled into something like contentment, as near as could be found in the muddy hell of France.

Wayfaring Stranger

Bell was not a fantastic healer, but he could manage to close a gash, though not, it became apparent, without leaving a scar. Three days after Nevin had half-carried Rab, blood pouring from a deep bullet graze on his scalp, to the rendezvous in the trenches near Hargicourt, the wound looked years old.

Less well healed were the wounds to Rab’s gentle heart--concussed, blood-blinded, stumbling more under Nevin’s power than his own, he’d been in no shape to cast his usual shields, but nothing would convince him Hume’s death hadn’t been his fault.