#and the way his entire narrative was shown to be hinged on

Note

that is precisely why vasseur is just another binotto to me. i have yet to see the guy actually let charles fight for what he wants. and to think it will be even more difficult next year with them wanting to give lewis another title... sighs.

Imo it's still better than it was under Binotto, especially in that post-Monaco and particularly post-Silverstone stretch in 2022 where they were forced to do the whole performative "we met for lunch in Monaco so it's all good now" PR thing to paint over the increasingly apparent cracks. Binotto blatantly favoured Carlos, both on and off the track, even going as far as publicly throwing Charles under the bus by shifting the blame for a poorly executed strategy to the car having no pace when Charles explicitly called out the whack tyre strat, for example in Hungary. I don't think we've had a situation like that happen with Fred, that I can recall.

Charles has generally said positive things about Fred and reiterated that he has trust in him, that he's seen positive developments under his leadership. The SF24 is definitely an improvement over last year's car. There have been several employee changes, which people generally see as a good thing. So, all in all I think it is an improvement but it could be better, especially with stuff like team orders.

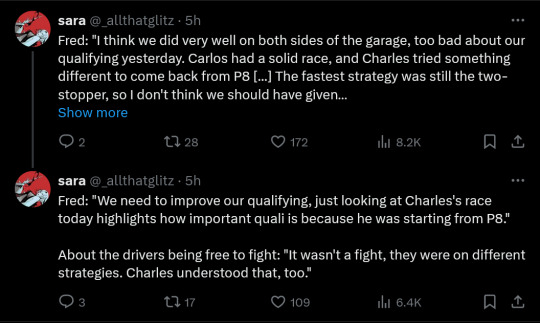

Here's how Fred addressed the situation post-race:

Stuff like that is frustrating when you remember how many times Charles has been used as a roadblock or made to create an artificial gap (their entire Singapore strategy hinged on Charles's cooperation.) Sure, this wasn't for the win, and Charles himself said qualy is bigger issue, but it's the principle of the thing. Charles drove an incredible race with that insane one stop strategy and was ahead on position (if that's what they want to use as the determining factor.) Even if he shoulders the blame for his qualy results on the weekends where he's outqualified by Carlos and accepts that CS will be the one given the preferential strategy/treatment based on that, there's been plenty of instances where Charles qualified higher but then Carlos made up the difference in the race and was hailed as a genius.

Idk it feels like part of it might be them not exactly trusting Carlos will cooperate? He's shown many times before that he's primarily in it for himself and even when he was explicitly told to do something he didn't if he felt it wasn't beneficial for him—and that was when he still had a contract with Ferrari, now that he knows he's on the way out and has the sympathy narrative on his side he has nothing to lose. But it shouldn't be solely on Charles to be the cooperative one, to put the team result first. I know he wants to feel that he's earned the podium (which, like, he has in this race) and he won't be satisfied until he's in front in qualy and the race, but yeah, frustrating to see the pattern continue into this year.

To counter the negativity somewhat, I will say I know it's still early days, there's still plenty of races to go, and if they manage to solve the qualy tyre warm-up issue (which Charles already vowed to work on on his side, and we know he always comes through) and the upgrade packages that are in the pipeline (hopefully) help close the gap to Red Bull in race pace, then we could still be in for an interesting and potentially competitive back half of the season. I just hope that situations like this don't come back to bite them when Charles is potentially in a position to fight for P2 with Checo, or maybe even P1 if Max encounters more issues down the line, but it's those points that make the difference in the end.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok, see, but I love what they are doing in the new interview with the vampire. They've taken the concept of the Other and made it more explicit in Louis's Blackness and queerness; they've shown where it does not work, how it is a cudgel over his head. They've taken his self-loathing and rooted it in the ways in which the world told him he was less than human, and because of that, because of his grief, because of the ways in which he was denied his grief over Paul being valid (you did it; what did you say to him, Louis), the ways in which his anger is stymied, that the power of vampirism makes sense. and presented in a loving package, in the adoration, of one person. And Lestat validates Louis's anger (not that he needs it, but in this moment, in his crisis, he needs to be told he is not alone, that it all has meaning, that is all correct, that his life, and Paul's life, have meaning outside of whatever tiny box they've been squished into--that coffin comment was more than just a joke on Lestat's sleeping place).

it is a gorgeous, dark place, full of anger and vengeance. Lestat continues to get his on God via the priests and he offers Louis a path of his own. And he offers Louis himself. The adoration. The headiness of his gaze. A proximity to power (that Whiteness offers; Louis had his own form in Storyville). An affirmation.

And here I wonder if this is what Louis needs from Daniel. A recognition that the decisions weren't all wrong, that he was in the right, that his vengeance was just, that his love wasn't misplaced.

"Where did all of his love go"

also, I really love how they are playing with his unreliability. What is his truth and what is truth and do they meet somewhere in the middle? And I love how Daniel calls out the inconsistencies with the prior narrative but we also know Daniel is fallible. He told us himself.

It really is a brilliant show. It may be filling a hole in my heart that Hannibal left. And the podcast has a lot of interesting context, both in how they provide backstory, but the metatextual people they bring on, such as the Black horror expert and the queer horror expert. It's an intentionalty of it for me.

(also this entire show hinges on Jacob Andersen and he is killing it. just absolutely carrying every damn moment with perfection)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

the one thing i'll get off my chest about the wilds because i thought it (generally.) did a good job of being both morally complicated show and also batshit wild enough to give its more questionable sociological takes the benefit of the doubt and idiotic "experimental" conditions but. like who decided to make ivan like that. overall i felt the boys of color were underserved in terms of complicating their narratives while still providing a sympathetic lens, but ivan truly was the worst of it.

it was weird to hinge so much of his personality and backstory on defensive and outsized reactions wrt his black and queer identity without ever justifying it. sure the acknowledgement that black queer people suffer enormous tragedies might be enough of a known reality to explain his actions, but relying on that outside information is a lazy writing choice. the difficulties (both external and internalized) of the queer experience is given real nuance in this show, but the black experience and especially the black queer experience is deeply... vague. the reids' were only really connected to their black identity through interpretive subtext that could have been unintentional, and the only real development is arguably through ivan and scotty's two interactions, which i also felt rang hallow to thinking about issues of masculinity and homophobia within the black community.

ivan's experience is most directly connected to his economic privilege, and any of his radical takes were based off a type of performative activism and a type of "cancel culture" that is so much more reflective of a specific brand of white liberalism that to make it the central characteristic of this black queer boy is so......... the word isn't even out of touch, it's just racist and belittling to black experiences.

like. WHY have him demean kirin like that. why make him so consistently annoying and unsympathetic. why have his attempts at mediation or helping be shown so clearly as missteps. why have his boyfriend, clearly meant to be the "good" and more fully realized black queer boy, only exist to show how shallow ivan is and to ultimately provide an opportunity to show kirin in all his nuance and complications in an entirely sympathetic moment. luc's entire purpose felt like a way to rebuke ivan, and he's given no characterization beyond that.

sorry this became more of a mindless rant and i'll try to post something more concise and to the point later but it's like. this isn't about me "not liking" ivan, though i'll admit i'm more sensitive and critical of how black and queer stories are handles, but his character character was so fully trashed from the beginning that it's just..... it's so disheartening and insulting, and i felt that its different narrative parallels to the boys' conflict ended up undermining their storyline.

#also different ways i was disappointed by scotty but not as much... ik its a majority white writer's room but come on#erghhh had so many dif thoughts about this season most of them positive or at least silly and goofy#but this one had me like. there's not even any interesting moral quandaries you can get into here it's just bad writing#the wilds#ivan taylor#hopefully they'll do him better next season bc i can so easily get behind his annoying lil punk ass if he just had a bit more DEPTH#the wilds spoilers

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Roku/Sozin ancestry plot twist for Zuko

Like I’m sure this has been said before but the twist about Zuko being a descendant of both Roku and Sozin is actually a disservice to his character and his narrative as well? The way the narrative frames this reveal along with Iroh's dialogue, it backtracks on a lot of the story we are shown in Book 1&2 (and sometimes it even clashes with some dialogues in Book 3).

Iroh: “Because understanding the struggle between your two great-grandfathers can help you better understand the battle within yourself. Evil and good are always at war inside you, Zuko. It is your nature, your legacy. But, there is a bright side. What happened generations ago can be resolved now, by you. Because of your legacy, you alone can cleanse the sins of our family and the Fire Nation. Born in you, along with all the strife, is the power to restore balance to the world.”

1. This implies that there are equal amounts of good and evil in Zuko and his internal struggle is about choosing one of them.

The core qualities of Zuko as a character are empathy, compassion and kindness. A person who always gets upset when he sees or even thinks about other people in pain, a person who spoke out against powerful people to save lives that were being sacrificed needlessly, a person who shows mercy to people who don’t deserve it, a person who is willing to reach out a hand to save the life of the man who tried to kill him, a person who avoids fights when possible, a person who is willing to fight on behalf of a family he has known for only one night, a person who reaches out to sympathise after being yelled at— a person like this is definitely not struggling with equal parts of good and evil within them.

Zuko does have two selves, but they can be categorised as pre-scar and post-scar.

His pre-scar version is the version who was unabashedly kind and compassionate, who spoke his mind without thinking of consequences. But his post-scar version was a cover up of the pre-scar version. It was a lie that Zuko lived everyday. He convinced himself that this was how he had to be; because this was what Ozai wanted him to be and that there was no other way.

And yet, when the situation is dire and he is depending on his instincts or when he is given a free choice, we see the pre-scar Zuko spring into action. Because that’s who he really is. It’s not a struggle between good and evil within him, it is his supressed self making an appearance when he slips up and fails to maintain his facade.

Perhaps the line that describes his internal struggle the best is this:

Zuko, imitating Iroh: Zuko, you have to look within yourself to save yourself from your other self. Only then will your true self, reveal itself.

And while this dialogue was played for laughs, it is the most accurate description of how Zuko had to reach for his suppressed self, his real self, to save himself from becoming what Ozai wanted him to be.

2. It also implies that Ozai and Ursa had equal influence on Zuko's upbringing and that he struggled to chose between what was taught to him by Ursa (good) and Ozai (evil).

The idea that Zuko has equal amounts of good and evil inside himself goes hand in hand with idea that the good and evil traits in him have been passed onto him by Ursa and Ozai's upbringings respectively which are legacies of Roku and Sozin.

I don’t need to look any further than “Zuko Alone” to know that Ozai's impact on Zuko's upbringing was slim to none. The flashbacks that we see, are dominated by Ursa's presence. Ozai hardly gets any time onscreen. And when he does, he is shown as a silhouette and when he isn’t a silhouette, we only see him smile at Azula's display of skills and frown at Zuko's attempt.

Ozai was Zuko's father alright, but never in the ways that mattered. We know that Ozai abused Zuko. He constantly belittled him and compared him to Azula. Partially because Zuko lacked the natural talent that Azula had and partially because he lacked the ruthlessness and cruelty that Azula displayed even at her age.

Which made Zuko copy Azula's behaviour to get his father’s acceptance. But whenever Ursa noticed this, she immediately corrected Zuko and clearly told him that it was wrong.

Ozai is never shown to tell Zuko that whatever Ursa told him was wrong. Ozai personally never taught him anything (except that one time). He appreciated Azula's behaviour and encouraged her to keep it up but he just kept on expressing his disappointment in Zuko.

Ursa: Remember this, Zuko. No matter how things may seem to change, never forget who you are.

Zuko's innate kindness and compassion were protected by Ursa in the formative years when he was at his most pliable. And this is why no matter what happens, he never loses these qualities and is able to retain his real self even after he tried hard to suppress it.

3. It diminishes the extent of psychological damage and trauma caused by the scarring incident.

The one time Ozai did take it upon himself to teach something to Zuko:

Ozai: You will learn respect, and suffering will be your teacher.

(Notice that here too Ozai's form is silhouetted against the light behind him.)

The scar is so much more than just a scar to Zuko. It is the one lesson that Ozai taught him. The scar exists because of Zuko's innate compassion. It was put on his face in an attempt to burn out his compassion. It was put there to be a constant reminder of what would happen if he dared to do something that went against what Ozai wanted from him. The scar was Ozai’s brand on his face. It took away Zuko's autonomy to make decisions for himself. It was a constant reminder that Zuko’s opinions didn’t matter.

Post-scar Zuko is Zuko's attempt at supressing his real persona to become the person Ozai wanted him to be, because he learned the hard way that he didn’t have the choice to be anyone else.

In fact, the first time Zuko makes a deliberate choice to go against what was expected of him, (letting Appa go) he succumbed to a fever. His emotional turmoil of coming to terms with the fact that he didn’t need to listen to Ozai and abide by him; a notion that he had been force feeding himself, everyday, for the last three years, manifested itself physically in the form of a fever. That was how deep the psychological damage caused by the scar was. (I hate it when people call it an angst coma.)

Saying that Zuko was struggling with equal amounts of good and evil within him, oversimplifies the complex emotional trajectory he had about coming to terms with the abuse he went through and reclaiming his autonomy and his personal opinions and beliefs, into just a choice between two aspects of his personality.

Zuko: I wanted to speak out against this horrifying plan, but I'm ashamed to say I didn't. My whole life, I struggled to gain my father's love and acceptance, but once I had it, I realized I'd lost myself getting there. I'd forgotten who I was.

4. This implies that Zuko's destiny was pre-determined.

Iroh said in the dialogue that Zuko was born with the power to restore balance in the world and that only he could do it.

Zuko, the character who has always had to struggle to gain what he wanted is suddenly told of an advantage that he had just by the virtue of birth? Kinda defeats the purpose of: "Azula was born lucky; I was lucky to be born", if you ask me.

And even more importantly, he let go of the destiny that Ozai forced on him, only to take on another predetermined destiny; a destiny that was his to fulfil by the virtue of birth, and took steps to fulfil this other destiny, instead of making a destiny of his own and paving his own path to it by making the choices that he had been denied for so long because of Ozai. Which seems weird because all the other times Iroh talks to Zuko about this topic, he always emphasises on how it’s Zuko's choice to make his own destiny:

Lake Laogai:

Zuko: I want my destiny.

Iroh: What that means is up to you.

Lake Laogai:

Zuko: I know my own destiny, Uncle!

Iroh: Is it your own destiny, or is it a destiny someone else has tried to force on you?

Zuko: Stop it, Uncle! I have to do this!

Iroh: I'm begging you, Prince Zuko! It's time for you to look inward and begin asking yourself the big questions. Who are you, and what do you want?

Crossroads of Destiny:

Iroh: Zuko, I am begging you. Look into your heart and see what it is that you truly want.

Western Air Temple:

Iroh: You know Prince Zuko, destiny is a funny thing. You never know how things are going to work out. But if you keep an open mind, and an open heart, I promise you will find your own destiny someday.

5. It indirectly implies that the good™ in Ursa and Zuko exists because they are a part of the Avatar's legacy.

Making Ursa a daughter of a nobleman (as intended originally)* would’ve served a much better purpose for the message that the episode was trying to get across: “the Fire Nation isn’t inherently evil”.

Katara: You mean, after all Roku and Sozin went through together, even after Roku showed him mercy, Sozin betrayed him like that?

Toph: It's like these people are born bad.

Aang: Roku was just as much Fire Nation as Sozin was, right? If anything, their story proves anyone's capable of great good and great evil. Everyone, even the Fire Lord and the Fire Nation have to be treated like they're worth giving a chance.

Had Ursa not been Roku’s descendant, then there would've been people other than just Roku and his descendants, who were Fire Nation and good™. (Iroh is literally the only exception.)

Moreover, Azula is just as much a part of “Roku’s legacy” as Zuko is, and yet is completely overlooked when it comes to it. She isn’t shown to be struggling with equal amounts of good and evil. She isn’t gifted at birth with the capacity to bring balance back to the world. It appears as if she had inherited only “Sozin's legacy”.

So, not only does this Roku/Sozin twist go against Zuko's fundamental characterisation, but it also partially deconstructs the narrative that had been carefully set up for him over the course of 2 seasons.

*(I have been looking relentlessly for the post where I saw two screen caps of the two different characterisations of Ursa: 1. Ursa as we see her in "Zuko Alone"; 2. Ursa as Roku's descendant. And I can't find it now otherwise I would've linked it.)

#i saw a vid on atla's official yt abt zuko#and the way his entire narrative was shown to be hinged on#being roku and sozin's descendant#it pissed me off; so here's the rant#zuko#zuko meta#prince zuko#atla zuko#atla#atla meta#ozai#lady ursa#azula#roku#sozin#avatar#avatar the last airbender#ira's posts

218 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey what are your opinions on this video, o wise worstloki? (tw sylki kiss, but it's an analysis so it's good)

https://youtu.be/N8bsJr7Hjzg

it was all downhill after the first 5 seconds sounded like it was saying odin should've kissed loki in the vault scene

#the analysis wouldn't be so bad if it wasn't hinging everything on romantic love being a way to accept himself#it feels like it's relaying what the showrunners tried to say#which is a narrative I don't see the show itself actually supporting#I also don't subscribe to the Loki-Is-A-Narcissist club and as most videos this one ignores the context of Asgard where it was raised#it ignores that Loki WAS treated unfairly and that WAS raised on racism and literally DOES have the titles of god and king on the table#he wasn't declared heir but the worst you can say about that is that he was jealous of thor#the thing is though that he recognizes he's jealous and with love for Thor (until the other issues come in in Thor 1) doesn't want a throne#he only starts doing so AFTER it's been granted to him as a way to prove his worth to Odin especially but Frigga too#the entire situation is built so that Loki's insecurities and doubts ARE reasonable#his actions in trying to destroy Jotunheim and conquer Earth? ignoring Thanos even and saying it was all him? overreaction. yeah. we get it#BUT#take into account that Asgard treats slaughter as a casual thing and Thor's been talking about slaying the jotuns since childhood#and take into account that Thor and Loki have very much been indoctrinated to see mortals as trivial infantalized and lesser#plus they've got super strength and longevity and magic?#the Aesir/Jotun are literally 'above' the humans#Loki has shown multiple times he's not powerhungry and not interested in a throne or ruling#so no i don't think much of this analysis#though it tries to draw parallels between movie Loki and show Loki it only does so within the capacity of false premises the show presents#the Loki show#loki spoilers#loki show spoilers#thank you for sharing the video though#i admit i skimmed through most of it#the take on ragnarok was just ''loki isnt a narcissist in THIS movie bc he services others so it's just high self esteem''#and ye that made me simmer a little

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Loving your meta on suibian :)) Just wondering what were your frustrations with cql, especially considered you've watched this in multiple mediums? (I've only watched cql)

Hi anon! thank you so much!

Oh boy, you’ve unlocked a boatload of hidden dialogue, are you ready?? :D (buckle up it’s oof. Extremely Long)

@hunxi-guilai please consider this my official pitch for why I think the novel is worth reading, if only so you can enjoy the audio drama more fully. ;)

a few things before I get into it:

I don’t want to make this a 100% negative post because I really do love CQL so much! So I’m going to make it two parts: the changes that frustrated me the most and the changes I loved the most re: CQL vs novel. (again, don’t really know anything about donghua or manhua sorry!!) Sound good? :D

this will contain spoilers for the entirety of CQL and the novel. just like. All of it.

talking about the value of changes in CQL is difficult because I personally don’t know what changes were made for creative reasons and what changes were made for censorship reasons. I don’t think it’s entirely fair to evaluate the narrative worth of certain changes when I don’t know what their limitations were. It’s not just a matter of “gay content was censored”; China also has certain censorship restrictions on the portrayal of the undead, among other things. I, unfortunately, am not familiar enough with the ins and outs of Chinese censorship to be able to tell anyone with certainty what was and wasn’t changed for what reason. So I guess just, take whatever my opinions are with a grain of salt! I will largely avoid addressing issues related to how explicitly romantic wangxian is, for obvious reasons.

OKAY. In order to impose some kind of control on how much time I spend on this, I’m going to limit myself to four explicated points in each category, best/worst. Please remember that I change my opinions constantly, so these are just like. the top contenders at this specific point in my life. Starting with the worst so we can end on a positive note!

Henceforth, the novel is MDZS, CQL is CQL.

CQL’s worst crimes, according to cyan:

1. Polarizing Wei Wuxian and Jin Guangyao on the moral spectrum

I’ve heard rumors that this was a censorship issue, but I have never been able to confirm or deny it, so. Again, grain of salt.

The way that CQL reframed Wei Wuxian and Jin Guangyao’s character arcs drives me up the wall because I think it does a huge disservice to both of them and the overarching themes of the story. Jin Guangyao is shown to be responsible for pretty much all the tragedy post-Sunshot, which absolves Wei Wuxian of all possible wrongdoing and flattens Jin Guangyao into a much less interesting villain.

What I find so interesting about MDZS is how much it emphasizes the role of external forces and situations in determining a person’s fate: that being “good” or “righteous” at heart is simply not enough. You can do everything with all the best intentions and still do harm, still fail, still lose everything. Even “right” choices can have terrible consequences. Everyone starts out innocent. “In this world, everyone starts without grievances, but there is always someone who takes the first blow.”

It matters that Wei Wuxian is the one who loses control and kills Jin Zixuan, that his choices (no matter how impossible and terrible the situation) had consequences because the whole point is that even good people can be forced into corners where they do terrible things. Being good isn’t enough. You can do everything right, make every impossible choice, and fail. You can do the right thing and be punished for it. Maybe you did the right thing, but others suffer for your actions. Is that still the right thing? Is it your fault? Is it? By absolving Wei Wuxian of any conceivable blame, it really changes the narrative conclusion. In MDZS, even the best people can do incomprehensible harm when backed into corners, and the audience is asked to evaluate those actions with nuance. Is a criminal fully culpable for the harm they do when their external circumstances forced them into situations where they felt like they had no good choices left?

Personally, I feel like the novel asks you to forgive Wei Wuxian his wrongs, and, in paralleling him with Jin Guangyao, shows how easily they could have been one another. Both of them are extraordinarily talented sons of commoners; the difference lies in what opportunities they were given as they were growing up and how they choose to react to grievances. Wei Wuxian is adopted early on into the head family of a prominent sect and treated (more or less—not going to get into it) like a son. Jin Guangyao begs, borrows, steals, kills for every scrap of prestige and honor he gets and understands that his position in life is, at all points, extraordinarily unstable. Wei Wuxian doesn’t take his grievances to heart, but Jin Guangyao does.

To be clear, I don’t think the novel places a moral value on holding grudges, if that makes sense. I think MDZS only indicates that acts of vengeance always lead to more bloodshed—that the only escape is to lay down your arms, no matter how bitter the taste. Wei Wuxian was horribly wronged in many ways, and I don’t think I would fault him for wanting revenge or holding onto his anger—but I do think it’s clear that if he did, it would destroy him. It destroys Jin Guangyao, after all.

(It also destroys Xue Yang, and I think the parallel actually also extends to him. Yi City, to me, is a very interesting microcosm of a lot of broader themes in MDZS, and I have a lot of Thoughts on Xue Yang and equivalent justice, etc. etc. but. Thoughts for another time.)

Wei Wuxian is granted a happy ending not because he is Good, but because public opinion has changed, because there’s a new scapegoat, because he is protected by someone in power, because he lets go of the past, and because the children see him for who he is. I really do think that the reason MDZS and CQL have a hopeful ending as opposed to a bleak one hinges on the juniors. We are shown very clearly throughout the story how easily and quickly the tide of public opinion turns. The reason we don’t fear that it’s going to happen to Wei Wuxian again (or any other surviving character we love) is, I think, because the juniors, who don’t lose their childhoods to war, have the capacity to see past their parents’ prejudices and evaluate the actions of the people in front of them without having their opinions clouded by intense trauma and fear. They are forged out of love, not fire.

In CQL however, it emphasizes that Wei Wuxian is Fundamentally Good and did No Wrong Ever, so he deserves his happy ending, while Jin Guangyao is Fundamentally Bad and Responsible For Everything, so he got what was coming to him (even if we feel bad for him maybe). That’s not nearly as interesting or meaningful.

(One specific change to Jin Guangyao’s timeline of evil that I find particularly vexing, not including the one I will discuss in point 2, is changing when Jin Rusong was conceived. In the novel, Qin Su is supposedly already pregnant by the time they get married, and that matters a WHOLE LOT when evaluating Jin Guangyao’s actions, I think.)

2. Wen POWs used as target obstacles at Baifeng Mountain

I know the first point was “here’s an overarching plot change that I think deeply impacts the narrative themes” and this second one is “I despise this one specific scene detail so much”, but HEAR ME OUT. It’s related to the first point! (tbh, most things are related to the first point)

Personally, I think this one detail character assassinates like. almost everyone in attendance, but most egregiously in no particular order: Jin Guangyao, Jin Zixuan (and by extension, Jiang Yanli), Wei Wuxian, Lan Wangji and Lan Xichen.

First, I think it’s a cheap plot device that’s obviously meant to enhance Jin Guangyao’s ~villainy while emphasizing Wei Wuxian’s growing righteous anger, but it fails so spectacularly, god, I literally hate this detail so much lmao. I’ll go by character.

Jin Guangyao: I get that CQL is invested in him being a ~bad person~ or whatever, but this is such a transparently like, cartoon villain move that lacks subtlety and elegance. Jin Guangyao is very dedicated to being highly diplomatic, appeasing, and non-threatening in his bid for power. He manipulates behind the scenes, does his father’s dirty work, etc. but he always shows a gentle, smiling face. This display tips his hand pretty obviously, and even if it were at the behest of his father, there’s literally no reason for him to be so “ohohoho I’m so evil~” about it—if anything, this would only serve to drive his sympathizers away. It’s a stupid move for him politically, and really undercuts his supposed intelligence and cleverness, in my personal opinion.

Jin Zixuan: yes, he is arrogant and vain and likes to show off! But putting his ego above the safety of innocent people? Like, not necessarily OOC, but it sure makes him much less sympathetic in my eyes. I find it hard to believe that Jiang Yanli would find this laudable or acceptable, but she’s given a few shots where she smiles with some kind of pride and it’s like. No! Do not do my queen dirty like this. She wouldn’t!

Wei Wuxian: where do I start! WHERE DO I START. Wei Wuxian is shown to be “righteously angry” about this, but steps down mutinously when Jiang Cheng motions him back. He looks shocked and outraged at Jin Zixuan for showing off with no concern for the safety of the Wen POWs, only to like, two seconds later, do the exact same thing, but worse! And at the provocation of Jin Zixun, no less! *screams into hands* The tonal shift is bizarre! We’re in this really tense ~moral quandary~, but then he flirts with Lan Wangji for a second (tense music still kinda playing?? it’s awful. I hate it), and then does his trickshot. You know! Putting all these people he’s supposedly so concerned about at risk! To one-up Jin Zixuan! It’s nonsensical. It’s such a conflict of priorities. This is supposed to make him seem honorable and cool, I guess? But it mostly just makes him look like a performative hypocrite. :///

Lan Wangji: I cannot believe that Lan Wangji saw this and did not immediately walk out in protest.

Lan Xichen: this is just one part of a larger problem with Lan Xichen’s arc in CQL vs MDZS, where his character development was an unwitting casualty of both wangxian censorship and CQL’s quest to demonize Jin Guangyao. One of the prevailing criticisms I see of Lan Xichen’s character is that he is a “centrist”, that he “allows bad things to happen through his inaction and desire to avoid conflict”, and that he is “stupid and willfully blind to Jin Guangyao’s faults”, when I don’t think any of this is supported by evidence in the novel whatsoever. Jin Guangyao is a subtle villain! He is a talented manipulator and liar! Even Wei Wuxian says it in the novel!

(forgive my rough translations /o\)

Chapter 49, as Wei Wuxian (through Empathy with Nie Mingjue’s head) listens to Lan Xichen defend Meng Yao immediately following Wen Ruohan’s assassination:

魏无羡心中摇头:“泽芜君这个人还是……太纯善了。”可再一想,他是因为已知金光瑶的种种嫌疑才能如此防备,可在蓝曦臣面前的孟瑶,却是一个忍辱负重,身不由己,孤身犯险的卧底,二人视角不同,感受又如何能相提并论?

Wei Wuxian shook his head to himself: “This Zewu-jun is still…… too pure and kind.” But then he thought again—he could only be so guarded because he already knew of all of Jin Guangyao’s suspicious behavior, but the Meng Yao before Lan Xichen was someone who had had no choice but to suffer in silence for his mission, who placed himself in grave danger, alone, undercover. The two of them had different perspectives, so how could their feelings be compared?

Chapter 63, after Wei Wuxian wakes up in the Cloud Recesses, having been brought there by Lan Wangji:

他不是不能理解蓝曦臣。他从聂明玦的视角看金光瑶,将其奸诈狡猾与野心勃勃尽收眼底,然而,如果金光瑶多年来在蓝曦臣面前一直以伪装相示,没理由要他不去相信自己的结义兄弟,却去相信一个臭名昭著腥风血雨之人。

It wasn’t that he couldn’t understand Lan Xichen. He had seen Jin Guangyao from Nie Mingjue’s perspective, and so had seen all of his treacherous and cunning obsession with ambition. However, if Jin Guangyao had for all these years only shown Lan Xichen a disguise, there was no reason for [Lan Xichen] to believe a famously violent person [Wei Wuxian] over his own sworn brother.

Lan Xichen, throughout the story, is being actively lied to and manipulated by Jin Guangyao. His only “mistake” was being kind and trying to give Meng Yao, someone who came from a place of great disadvantage, the benefit of the doubt instead of immediately dismissing him as worthless due to his birth or his station in life. Lan Xichen sees Meng Yao as someone who was forced to make impossible choices in impossible situations—you know, the way that we, the audience, are led to perceive Wei Wuxian. The only difference is that the story that we’re given about Wei Wuxian is true, while the story that Lan Xichen is given about Meng Yao is… not. But how would have have known?

The instant he is presented with a shred of evidence to the contrary, he revokes Jin Guangyao’s access to the Cloud Recesses, pursues that evidence to the last, and is horrified to discover that his trust was misplaced.

Lan Xichen’s willingness to consider different points of view is integral to Wei Wuxian’s survival and eventual happiness. Without Lan Xichen’s kindness, there is no way that Wei Wuxian would have ever been able to clear his name. Everyone else was calling for his blood, but Lan Wangji took him home, and Lan Xichen not only allowed it, he listened to and helped them. To the characters of the book who are not granted omniscient knowledge of Wei Wuxian’s actions and circumstances, there is literally no difference between Wei Wuxian and Jin Guangyao. Lan Xichen is being incredibly fair when he asks in chapter 63:

蓝曦臣笑了,道:“忘机,你又是如何判定,一个人究竟可信不可信?”

他看着魏无羡,道:“你相信魏公子,可我,相信金光瑶。大哥的头在他手上,这件事我们都没有亲眼目睹,都是凭着我们自己对另一个人的了解,相信那个人的说辞。

“你认为自己了解魏无羡,所以信任他;而我也认为自己了解金光瑶,所以我也信任他。你相信自己的判断,那么难道我就不能相信自己的判断吗?”

Lan Xichen laughed and said, “Wangji, how can you determine exactly who should and should not be believed?”

He looked at Wei Wuxian and said, “You believe Wei-gongzi, but I believe Jin Guangyao. Neither of us saw with our own eyes whether Da-ge’s head was in his possession. We base our opinions on our own understandings of someone else, our belief in their testimony.

“You think you understand Wei Wuxian, and so you trust him; I also think I understand Jin Guangyao, so I trust him. You trust your own judgment, so can’t I trust my own judgment as well?”

But he hears them out, examines the proof, and acts immediately.

I really do feel like this aspect of Lan Xichen kind of… became collateral damage in CQL. Because Jin Guangyao is so much more publicly malicious, Lan Xichen’s alleged “lack of action” feels much less understandable or acceptable.

It is wild to me that in this scene, Lan Xichen reacts with discomfort to the proceedings, but has nothing to say to Jin Guangyao about it afterwards and also applauds Wei Wuxian’s archery. (I could talk about Nie Mingjue here as well, but I would say Nie Mingjue and Lan Xichen have very different perspectives on morality, so this moment isn’t necessarily OOC for NMJ, but I do think is very OOC for LXC.) This scene (among a few others that have Jin Guangyao being more openly “evil”) makes Lan Xichen look like a willfully blind bystander by the end of the story, but having him react with any action would have been inconvenient for the plot. Thus, he behaves exactly as he did in the book, but under very different circumstances. It reads inconsistently with the rest of his character (since a lot of the beats in the novel still happen in the show), and weakens the narrative surrounding his person.

None of these overt displays of cruelty or immorality happen in the book, so it makes perfect sense that he doesn’t do or suspect anything! Jin Guangyao is, as stated, perfectly disguised towards Lan Xichen. You can’t blame him for “failing to act” when someone was purposefully keeping him in the dark and, from his perspective, there was nothing to act upon.

This scene specifically is almost purely lighthearted in the novel! If you take out the Wen POWs, this just becomes a fun scene where Wei Wuxian shows off, flirts with Lan Wangji, gets into a pissing match with Jin Zixuan, and is overall kind of a brat! It’s great! I love this scene! The blindfolded shot is ridiculous and over-the-top and very cute!

I know this is a lot of extrapolation, but the whole scene is soured for me due to you know. *gestures upwards* Which is really a shame because it’s one of my favorite silly scenes in the book! Alas! @ CQL why! ;A;

3. Lan Xichen already being an adult and sect leader at the start of the show

This is rapidly becoming a, “Lan Xichen was Wronged and I Have the Receipts” essay (oh no), but you know what, that’s fine I guess! I never said I was impartial!

CQL makes Lan Xichen seem much older and more experienced than he is in the novel, though we’re not given his specific age. In the novel, he is not sect leader yet when Wei Wuxian and co. arrive at the Cloud Recesses for lectures. His father, Qingheng-jun, is in seclusion, and his uncle is the de facto leader of the sect. Lan Xichen does not become sect leader until his father dies at the burning of the Cloud Recesses. Moreover, my understanding of the text is that he is at most 19 years old when this happens. Wen Ruohan remarks that Lan Xichen is still a junior at the beginning of the Sunshot Campaign in chapter 61. (If someone has a different interpretation of the term 小辈, please correct me.) In any case! Lan Xichen is young.

Lan Xichen ascends to power under horrific circumstances: he is not an adult, his father has just been murdered, his uncle seriously injured, his brother kidnapped, and his home burnt to the ground. He is on the run, alone! Carrying the sacred texts of his family and trying to stay alive so his sect is not completely wiped out on the eve of war! He is terrified, inexperienced, and unprepared!

You know, just like Jiang Cheng, a few months later!

I see a lot of people lambasting Lan Xichen for not stepping up to protect the Wen remnants post-Sunshot, but I’m always flummoxed by the accusations because I don’t see criticisms of Jiang Cheng with remotely the same vitriol, even though their political positions are nearly identical:

they are both extraordinarily young sect leaders who came to power before they expected to through incredible violence done to their families

because of this, they are in very weak political positions: they have very little experience to offer as evidence of their competence and right to respect. if they are considered adults, they have only very recently come of age.

Jin Guangshan, who is rapidly and greedily taking the place of the Wen clan in the vacuum of power, is shown to be more than willing to mow people down to get what he wants—and he has the power to do so.

both Yunmeng Jiang and Gusu Lan were crippled by the Wen clan prior to Sunshot. And they just fought a war that lasted two and a half years. they are hugely weakened and in desperate need of time to rebuild, mourn, etc. both Jiang Cheng and Lan Xichen are responsible for the well-being of all of these people who are now relying upon them.

I think it’s very obvious that Jiang Cheng is in an impossible situation because he wears his fears and insecurities on his face and people in power (cough Jin Guangshan) prey upon that, while we, as the audience, have a front row seat for that whole tragedy. We understand his choices, even if they hurt us.

Why shouldn’t Lan Xichen be afforded the same consideration?

I really do think that because he’s presented as someone who’s much more composed and confident in his own abilities than Jiang Cheng is, we tend to forget exactly what pressures he was facing at the same time. We just assume, oh yes, of course Lan Xichen has the power to do something! He’s Lan Xichen! The First Jade! Isn’t he supposed to be Perfectly Good? Why isn’t he doing The Right Thing?

I think this is exacerbated by CQL’s decision to make him an established sect leader at the start of the show with several years of experience under his belt. We don’t know his age, but he is assumed to be an Adult. This gives him more power and stability, and so it seems more unacceptable that he does not make moves to protect the Wen remnants, even if in essence, he and Jiang Cheng’s political positions are still quite similar. He doesn’t really have any more power to save the Wen remnants without placing his whole clan in danger of being wiped out again, but CQL implies that he does, even if it isn’t the intention of the change.

It does make me really sad that this change also drives a further thematic divide between Lan Xichen and the rest of his generation. Almost everyone in that generation came of age through a war, which I think informs the way their tragedies play out, and how those tragedies exist in contrast to the juniors’ behavior and futures. Making Lan Xichen an experienced adult aligns him with the generation prior to him, which, as we’re shown consistently, is the generation whose adherence to absolutism and fear ruined the lives of their children. But Lan Xichen is just as much a victim of this as his peers.

(the exception being maybe Nie Mingjue, but it’s complicated. I think Nie Mingjue occupies a very interesting position in the narrative, but like. That’s. For another time! this is. already so far out of hand. oh my god this is point three out of eight oh nO)

(yet another aside because I can’t help myself: can you believe we were robbed of paralleling scenes of Jiang Cheng and Lan Xichen’s coronations? the visual drama of that. the poetic cinema. it’s not in the book, but can you IMAGINE. thank u @paledreamsblackmoths for putting this image into my head so that I can suffer forever knowing that I’ll never get it.)

I said I wasn’t going to talk at length about any changes surrounding Wangxian’s explicit romance for obvious reasons, but I will at least lament here that because a large percentage of Lan Xichen’s actions and character beats are directly in relation to Lan Wangji’s love for Wei Wuxian, he loses a lot of both minor and major moments to the censors as well. Many of the instances when he encourages Lan Wangji to talk to Wei Wuxian, when he indulges in their relationship etc. are understandably gone. But the most significant moment that was cut for censorship reasons I think is when he loses his temper with Wei Wuxian at the Guanyin temple and lays into him with all the fury and terror he felt for his brother’s broken heart for the last thirteen years.

Lan Xichen is only shown to express true anger twice in the whole story, both times at the Guanyin temple: first against Wei Wuxian for what he perceives as gross disregard for his little brother’s convictions, and second against Jin Guangyao for his massive betrayal of trust. And you know, murdering his best friend. Among other things.

I’m genuinely so sad that we don’t get to see Lan Xichen tear Wei Wuxian to shreds for what he did to Lan Wangji because I think one of the most important aspects to Lan Xichen’s character is how much he loves, cares for and fears for his little brother. The reveal about Lan Wangji’s punishment in episode 43 is a sad and sober conversation, but it’s not nearly as impactful, especially because Wei Wuxian asks about it of his own volition. I understand that this isn’t CQL’s fault! But. I can still mourn it right? ahahaha. :’)

I’ll stop before I descend further into nothing but Lan Xichen meta because that’s. Dangerous. (I have a lot of Feelings about how there are three characters who are held up as paragons of virtue in MDZS, how they all suffered in spite of their goodness, and how that all ties directly into the whole, “it is not enough to be good, but kindness is never wrong” theme. Anyways, they’re Xiao Xingchen, Jiang Yanli, and Lan Xichen, but NOT NOW. NOT TODAY.)

So yes, I’m a Lan Xichen apologist on main, and yes, I understand my feelings are incredibly personally motivated and influenced by my subjective emotions, but no I do not take concrit on this point, thank you very much.

4. all of the Wen remnants turning themselves in alongside Wen Qing and Wen Ning

Okay, back to plot changes. This change I would be willing to bet money was at least partially due to censorship, but it hurts me so deeply hahaha. It makes literally no sense for any of the characters and it completely janks the timeline of events post Qiongqi Dao 2.0 through Wei Wuxian’s death.

It’s not ALL bad—this change makes it easier for the Peak Wangxian moment at the Bloodbath at Nightless City (You know. Hands. Cliff. etc.) to happen, which I did very much enjoy. It’s pretty on-brand for CQL to sacrifice plot for character beats that they want to emphasize, so like. I get it! This moment is a huge gift! I Understand This. CQL collapses the Bloodbath at Nightless City and the First Siege of the Mass Graves into one event for I think a few reasons. One, Wangxian moment without being explicitly Wangxian, which is excellent. Two, it circumvents the Blood Corpse scene, which I do not think would have made it past censorship.

I’ll get to the Blood Corpse scene in a minute, but despite being able to understand why so much might have been sacrificed for the impact of the cliff scene, I still wish it had been done differently (and I feel like it could have been!), if only for my peace of mind because the plot holes it creates are pretty gaping.

The entire point of Wen Qing and Wen Ning turning themselves in is specifically to save their family members and Wei Wuxian from coming to further harm. That’s explicit, even in the show. Jin Guangshan demands that the Wen brother and sister stand for their crimes and claims that the blood debt will be paid. The Wen remnants understand that Wei Wuxian has given up so much for their sakes, that he has lost his family, his home, his respectability, his health, all in the name of sheltering them. To throw all of that away would be the greatest disrespect to his sacrifices. Wen Qing and Wen Ning decide that if their lives can pay for the safety of their loved ones and ensure that Wei Wuxian’s sacrifices matter, they are willing to go together and give themselves up.

So. Why did they. All go?? For… moral support???? D: Wen Qing says that Wei Wuxian will wake up in three days and that she’s given Fourth Uncle and the others instructions for his care–but then Fourth Uncle and the others all go with them!! To die!! There’s also very clearly a shot of Granny Wen taking A’Yuan with them, which like. Obviously didn’t really happen.

Wen Qing, who loves her family more than anything in the world, agrees that they should all go to Lanling and sacrifice themselves to…. protect Wei Wuxian? Wen Qing, pragmatic queen of my heart, agrees to this absurdly bad exchange?? Leaves Wei Wuxian to wake up, alone, with the knowledge that he had not only killed his brother-in-law but also effectively gotten everyone he had left killed also??

I can’t imagine Wen Qing doing that to Wei Wuxian. Save his life? For what? This takes away everything he has left to live for. You think Wen Qing doesn’t intimately understand how cruel that would be?

(Yes, I’m complaining about all of this, but I’m still about to cry because I rewatched the scene to make sure I didn’t say anything untrue, and g o d it manages to hit hard despite all of that, so who’s the real clown here!!)

Anyways. So that’s all just like. Frustratingly incoherent. It’s one of several wrongs I think CQL committed against Wen Qing’s character, but my feelings about Wen Qing in CQL are pretty complicated (I love her so much, and I love that we got more Wen Qing content, but that content sure is a mixed bag of stuff I really enjoyed and stuff I desperately wish didn’t exist) and I decided I wasn’t going to get into it in this post. (is anyone even still reading god)

This change also muddles Lan Wangji’s choices and punishment in ways that I think diminishes the severity of the situation to the detriment of both his characterization and his family’s characterization. The punishment scene is extremely moving and you should read this post about the language used in it but. sldfjsljslkf.

okay well, several things. In the context of CQL, which really pushes the “righteousness” angle of Wei Wuxian (see point 1), I think this scene makes a lot of sense in isolation: both Lan Wangji and Wei Wuxian are painted as martyrs for doing the right thing. “Who’s right and who’s wrong?” The audience is asked to see the punishment as “unjust”. That’s perfectly fine and coherent in the context of CQL, but I don’t think it’s nearly as interesting as what happens in MDZS.

Because CQL collapses both the First Siege and the Bloodbath into one event, Lan Wangji’s crimes are sort of unclearly defined. In episode 43, when Lan Xichen is explaining the situation, we see a flashback to when Su She says something along the lines of, “We could set aside the fact that you defended Wei Ying at Nightless City, but now you won’t even let us search his den?” (of course, this gives us the really excellent “you are not qualified to talk to me” line which. delicious. extremely vindicating and satisfying. petty king lan wangji.) Lan Xichen goes on to say something like, “Wangji alone caused several disturbances at the Mass Graves. Uncle was greatly angered, and [decreed his punishment]”. (Sorry, I’m too lazy to type out the full lines with translations, just. trust me on this one.)

Lan Wangji’s actions are shown to be motivated by a righteous love. Wei Wuxian is portrayed as someone innocent who stood up for the right thing against popular opinion and was scapegoated and destroyed for it, having done no wrong. (See, point 1 again.)

In MDZS, Lan Wangji’s crimes are very specific. It isn’t just that he caused some “disturbances” (this is just Lan XIchen’s vague phrasing in CQL—we don’t really know what he did). He steals Wei Wuxian away from the Bloodbath at Nightless City, after Wei Wuxian killed thousands of people, and hides him away in a cave, feeding him spiritual energy to save his life. When Lan Wangji’s family comes to find him, demand that he hand over Wei Wuxian (who is, remember, a mass murderer at this point! we can argue about how culpable he is for those actions all day—that’s the whole point, but the people are still dead), Lan Wangji not only refuses, but raises his hands against his family. He seriously injures thirty-three Lan elders to protect Wei Wuxian.

I don’t know how to emphasize how serious that crime is? Culturally, this is like. Unthinkable. To raise your hand against members of your own family, your elders who loved and raised you, in defense of an outsider, a man who, by all accounts, is horrifically evil and just murdered thousands of people, including other members of your own family, is like. That’s a serious betrayal. Oh my god. Lan Wangji, what have you done?

Lan Xichen explains in chapter 99:

我去看他的时候对他说,魏公子已铸成大错,你何苦错上加错了。他却说……他无法断言你所作所为对错如何,但无论对错,他愿意与你一起承担所有后果。

When I went to see him, I said, “Wei-gongzi’s great wrongs are already set in stone, why take the pains to add wrongs upon wrongs?” But he said…… he had no way to ascertain the rights and wrongs of your actions, but regardless of right or wrong, he was willing to bear all the consequences with you.

I think this is very different than what’s going on in CQL, though the differences appear subtle on the surface. In CQL, Lan Wangji demands of his uncle, “Dare I ask Uncle, who is righteous and who is wicked, who is wrong and who is right?” but the very act of asking in this way implies that Lan Wangji has an opinion on the matter (though perhaps not a simple one).

Lan Wangji in MDZS specifically says that he doesn’t know how to evaluate the morality of Wei Wuxian’s actions, but that regardless, he is willing to bear the consequences of his choices and his actions. He understands that his actions while sheltering Wei Wuxian are not clearly morally defensible. He did it anyways because he loved Wei Wuxian, because he thought that Wei Wuxian was worth saving, that there was still something good in him, despite the things he had done under mitigating circumstances. Lan Wangji did not save Wei Wuxian because he thought it was the right thing to do. He saved him because he loved him.

He is given thirty-three lashes with the discipline whip, one for each elder he maimed, and this leaves him bedridden for three years. Is this punishment horrifyingly severe? Yes! But is it unjustly given? I think that’s a much harder question to answer in the context of the story.

Personally, I think that question underscores the broader questions of morality contained within MDZS. I think it’s a much more interesting take on Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji as individuals. This asks, what can be pardoned? The righteous martyr angle is uncomplicated because moral certainty is easy. I think the situation in MDZS is far more uncomfortable if you examine its implications. And personally, I think that’s more meaningful!

(Not even going to touch on the whole, 300 strokes with a giant rod, but he has whip scars? And they were also sentenced to 300 strokes as kids for drinking alcohol…? CQL is not. consistent. on that front. ahaha.)

God, every point so far in this meta is just like “here’s one change that has cascading effects upon the rest of the show” dear god, okay, I’m getting to the Blood Corpse scene.

So in MDZS, the Wen remnants (besides Wen Ning and Wen Qing) do not go to Lanling. After the Bloodbath at Nightless City, Lan Wangji returns Wei Wuxian to the Mass Graves. Wei Wuxian lives with the Wen remnants for another three months before the First Siege, where he dies and the rest of the Wens are killed (except A’Yuan).

(Sidenote that I won’t get into: I love the dead spaces of time that MDZS creates. There’s very clear gaps in the narrative that we just never get the details on, most notably: Wei Wuxian’s three months in the Mass Graves post core transfer, and Wei Wuxian’s three months in the Mass Graves post Jiang Yanli’s death. They’re both extremely terrible times, but the audence is asked to imagine it instead of ever learning what really happened, what it was like. There’s something really cool about that narratively, I think.)

The Wen remnants are not cremated along with the rest of the dead. Their bodies are thrown into the blood pool.

At the Second Siege, when Wei Wuxian draws a Yin Summoning Flag on his clothes to turn himself into bait for the corpses in order to allow everyone else to escape to safety while he and Lan Wangji fight them off, there’s a moment when it gets really, truly dangerous—even with the help of the juniors and a few of the adults, they probably would have been killed. But then a wave of blood-soaked corpses come crawling out of the blood pool of their own accord and tear their attackers apart.

At the end of it, the blood corpses, the Wen remnants, gather before Lan Wangji and Wei Wuxian and Wen Ning. Wei Wuxian thanks them, they exchange bows, and the blood corpses collapse into dust. Wen Ning scrambles to gather their ashes, but runs out of space in his clothing. Several juniors, seeing this, offer up their bags to him and try to help.

It’s just. This scene is so important to me. Obviously, it couldn’t be included in CQL because of the whole undead thing, but it’s such a shame because I maintain that the Blood Corpse scene is one of the most powerful scenes in the whole goddamn book. It ties together so many things that I care about! It’s the moment when the narrative says, “kindness is not a waste”. Wei Wuxian failed to save them, but that doesn’t mean that his actions were done in vain. What he did matters. The year of life he bought them matters. The time they spent together matters.

This is also the moment when the juniors finally see Wen Ning for who he is—not the terrifying Ghost General, but a gentle man who has just lost his family for a second time. This is the moment when they reach out with kindness to the monster that their parents told them about at night. It matters that the juniors are able to do that! That they see this man suffering and are moved to compassion instead of righteous satisfaction.

(Except Jin Ling, for very understandable reasons, but Jin Ling’s moment comes later.)

It’s also the moment that we’re starkly reminded that many of the adults in attendance were present at the First Siege and directly responsible for the murders of the Wen remnants, including Ouyang Zizhen’s father. We’re reminded that he’s not just a comically annoying man with bad takes—he also participated in the murder of innocent people and then disrespected their corpses. But what retribution should be taken against him and the others? What retribution could be taken that wouldn’t lead to more tragedy?

There’s someone in the crowd in this scene named Fang Mengchen who refuses to be swayed by Wei Wuxian’s actions. “He killed my parents,” he says. “What about them? How can I let that go?”

“What more do you want from me?” Wei Wuxian asks. “I have already died once. You do not have to forgive me, but what more should I do?”

That is the ultimate question, isn’t it? What is the only way out of tragedy? You don’t have to forgive, but you cannot continue to take your retribution. It is not fair, but it’s all you have.

okay. so. those were my four Big Points of Contention with CQL, as I am currently experiencing them.

Honorable mentions go to: Wen Qing’s arc (both excellent and awful in different ways), making 13/16 years of Inquiry canon (I think this is untrue to Lan Wangji’s character, though I can understand why it was done), Mianmian’s departure from the Lanling Jin sect being shortened and having the sexism cut out (there’s something really visceral about the accusations against Mianmian being explicitly about her womanhood that I desperately wish had been retained in the show), cutting the scene where Jin Ling cries in mourning for Jin Guangyao and is scolded for it by Sect Leader Yao (my heart for that scene because it also matters so much)

but now!! onto the fun part, where I talk effusively about how much I love CQL!! this will probably be shorter (*prays*) because a lot of my frustrations with CQL are related to spiraling thematic consequences while the things I love are like. Simpler to pinpoint? If that makes sense? we’ll see.

CQL’s greatest virtues, also according to cyan:

1. this:

[ID: Wei Wuxian, trembling in fear, screaming “shijie!” as Jiang Cheng threatens him with Fairy in episode 34 of The Untamed drama. /end ID]

I understand that this is like, a very minor, specific detail change, but oh my GOD, it is like. Unparalleled. Every time I think about this change, I get so emotional and disappointed that it’s not in the novel, because I think it strengthens this scene tenfold. In the novel, Wei Wuxian calls out for Lan Zhan, which like, I get it. The story at this point is focused on the development of his romantic feelings for Lan Wangji, so the point of the scene is that the first person he thinks of in a moment of extreme fear is Lan Zhan, which surprises him. That’s fine. Like, it’s fine! But I think it doesn’t have nearly the same weight as Wei Wuxian calling for his sister to save him from his brother.

Having Wei Wuxian call out for his sister drives home the loss that the two of them have suffered, and highlights the relationship they all once had. Jiang Yanli is much more relevant to shuangjie’s narrative than Lan Wangji ever was, and this highlights exactly how deeply the fracturing of their familial relationship cuts. Wangxian gets so much time and focus throughout the rest of the novel. I love that this moment in the show is just about the Yunmeng siblings because that relationship is no less important, you know?

Calling out for Jiang Yanli in the show draws a much cleaner line through the dialogue. “You dare bring her up before me?” to “Don’t you remember what you said to Jin Ling?” It unifies the scene and twists the knife. It also gives us more insight into how fiercely Wei Wuxian was once beloved and protected by his siblings. Jiang Cheng promised to chase all the dogs away from Wei Wuxian when they were children. It’s clear that Jiang Yanli did as well.

Once upon a time, Wei Wuxian’s siblings defended him from his fears, and now one of them is dead and the other is using that fear to hurt him where he’s weakest. The reversal is so painfully juxtaposed, and it’s done with just that one flashback of Wei Wuxian as a child leaping into Jiang Yanli’s arms and calling out her name. Extremely good, economical storytelling. The conversation between shuangjie is much more focused on their own stories independent from Lan Wangji, which I very much appreciate. Wangxian, you’re wonderful, but this ain’t about you, and I don’t think it should be.

2. Extended Jiang Yanli content (and by extension, Jin Zixuan and Mianmian content)

Speaking of absolute goddess Jiang Yanli, I really loved what CQL did with her (unlike my more mixed feelings about Wen Qing). Having her in so many more scenes makes her importance to Jiang Cheng and Wei Wuxian a lot clearer, and we get to experience her as a person rather than an ideal.

On a purely aesthetic level, Jiang Yanli’s styling and character design is so stellar in CQL. The more prevalent design for her is kind of childish in the styling, which I don’t love (I think it’s the donghua influence?). And even I, someone who’s audio drama on main 24/7, personally prefer her CQL voice actor. There’s only a few characters in CQL that I look at and go “ah yes, that’s [character] 100%” and Jiang Yanli is one of them. I was blessed. I would lay down my life for her.

I’m really glad that CQL showed her illness more explicitly and gave her a sword, even if she never uses it! Her weak constitution is only mentioned once in the novel in chapter 69 in like two lines that I blew past initially because I was reading at breakneck speed and was only reminded of when my therapist who I conned into reading mdzs after 8 months of never shutting up oof brought it to my attention like two weeks ago. /o\

We never read about Jiang Yanli carrying a sword in the novel, though we are told that her cultivation is “mediocre”, so we know that she at least does cultivate, even if not very well. Highlighting her poor health in CQL makes her situation more clear, I think, and explains a little more about the way she’s perceived throughout the cultivation world as someone “not worthy of Jin Zixuan”. The novel tells us that Jiang Yanli is not an extraordinary beauty, not very good at cultivation, sort of bland in her expressions, and, very briefly, that she’s in poor health. I really love that description of Jiang Yanli, because it emphasizes that her worth has nothing at all to do with her talents, her health, her cultivation, her physical strength, or her beauty. She is the best person in the whole world, her brothers adore her, and the audience loves and respects her for reasons wholly unrelated to those value judgments. We love her because she is kind, because she is loyal, because she loves so deeply. Tbh, her only imperfection is falling for someone so tragically undeserving of her. (JK, I love you Jin Zixuan, and you do deserve her because you are an excellent boy who grows and changes and learns!! I can’t even be mean to characters as a joke god.)

Anyways, I just think the detail about her health is compelling and informs her character’s position in the world in a very specific way. I’m happy that CQL brought it to the forefront when it was kind of an easily-missed throwaway in the novel. It does mean something to me that Jiang Yanli, despite her poor physical health, is never once seen or treated as a burden by her brothers.

Something partially related that really hit hard was this:

[ID: two gifs. Jiang Yanli peeling lotus pods, looking up uncomfortably as her mother loses her temper about the Wen indoctrination at the table from episode 11 of The Untamed drama. /end ID]

D8 AAAAHHH this was VISCERAL. The novel is quite sparse in a lot of its descriptions and lets the audience fill in the missing details, so Jiang Yanli’s expression and reactions are not described when, after Jiang Cheng quickly volunteers to go to Qishan, Madam Yu accuses her of continuing to “happily peel lotus seeds” in such a dire situation.

“Of course you’ll go,” she snaps to Jiang Cheng. “Or else do you think we should let your sister go?”

This scene triggered me so bad lmfao, so I guess it’s kind of weird that I love it so much, but I felt Seen. Something about the way her nail slips in the second gif as she breaks open the pod is like. Oh, that’s a sense memory! Of me, as a child, witnessing uncomfortable conflict between people I cared about. I know this is an extremely personal bias, but hey, so is this whole meta. Because Jiang Yanli is often silent and quiet, it’s more her behavior and expressions that convey her character. It’s why the moment she lets loose on Jin Zixun is so powerful. We don’t get to see a lot of it in the novel, but because CQL is a visual medium, her character is a lot easier to pin down as a human as opposed to an abstract concept.

Anyways, in this moment, which I also think is a tangential reference to her weak constitution (it doesn’t feel like, “your sister can’t go because she’s a girl”; it feels like, “your sister can’t go because she couldn’t handle it”), we get to see Jiang Yanli’s own reaction to her perceived inadequacy. We see it in other places too—like how upset she is when Jin Zixuan dismisses her in several scenes, but this is the one that hits me the hardest because it’s about how her weakness is going to put her little brother in grave danger.

Last Yunmeng siblings with focus on Jiang Yanli scene that isn’t in the novel that I’m just absolutely wrecked over: the dream sequence in episode 28, when Jiang Yanli dreams about Wei Wuxian sailing away from her, but no matter how she shouts, or how she begs Jiang Cheng to help her, she can’t bring him back home.

I’m not going to gif it because I literally just like, fast-forwarded through it and started sobbing uncontrollably in front of my laptop, dear god.

I don’t know where the CQL writers found the backdoor directly into my brain’s nightmare center, but?? they sure did! IDK, I can see how this might be kind of heavy-handed, but it just. The sensation of being in a dream where something is going terribly wrong, but you’re the only one who seems to see it happening? But there’s nothing you can do? I feel like it’s a very fitting nightmare to give Jiang Yanli, who is acutely aware and constantly reminded of how little power she has in the world: not good enough for the boy she likes, not healthy enough to cultivate well, not strong enough to keep her family together.

The whole, elder siblings trying and failing to protect their younger siblings pattern is A Lot in the story, but there’s something particularly painful about seeing it happen to Jiang Yanli because of that awareness. All the other elder siblings are exceptionally talented or powerful in obvious ways. All Jiang Yanli has is the force of her will and the force of her love, and she knows it isn’t enough.

I care a lot about the Yunmeng siblings, okay! And I think CQL did right by them!

I’m only going to spend two seconds talking about Jin Zixuan and Mianmian, but I DO want to mention them.

Anyways, because we get more Jiang Yanli content, we ALSO get more soft xuanli, which is Very Good. Literally my kingdom for disaster het Jin Zixuan treating my girl right!! CQL said het rights, and I’m not even mad about it! I’m really happy that we get to see a little more of how their relationship plays out, and how hard Jin Zixuan works to change his behavior and apologize to her for his mistakes. The novel is from Wei Wuxian’s POV, so we miss the details, alas. Jin Zixuan covered in mud, planting lotuses? Blessed.

I think part of making Mianmian a larger speaking role is for convenience’s sake, but oh boy do I love that choice. Especially the Jin Zixuan & Mianmian relationship. Like, they’re so clearly platonic, and Mianmian is never once portrayed as a threat to Jiang Yanli. They just care about and respect each other a lot? Jin Zixuan’s distress when she defects from the Jin sect gets me in the heart, because it’s just like. God. I think there’s a lot of interesting potential there for her own thoughts re: Wei Wuxian. After all, she leaves her sect in defense of him, but he later kills a friend that she respects and loves. The moments shared between her and Jin Zixuan are minor, but they hint at a deeper relationship that I’m really glad was in the show.

3. To curb the strong, defend the weak: lantern scene (gusu) + rain scene (qiongqi dao 1.0)

I think I basically already explained why I love this so much in this post (just consider that post and this point to be the same haha), but just. Okay. A short addendum.

As much as I love novel wangxian, I really think that including this scene early on emphasizes why Lan Wangji loves Wei Wuxian so deeply. Of course he thinks Wei Wuxian is attractive, but this is the moment when he realizes, oh, this is who I love. Having that moment to reflect upon throughout Wei Wuxian’s descent is so excellent. I have enumerated all of my issues with the “perfectly righteous Wei Wuxian” arc that CQL crafted, but having this narrative throughline in conjunction with the novel arc would be like. My favored supercanon ahaha. (It would need some tweaking, but I think it would work.) It shows us exactly who it is that Lan Wangji sees and is trying to save, who he thinks is still there, underneath all the carnage and despair and violence and grief. This is the Wei Wuxian Lan Wangji loves and is unwilling to let go. This is the Wei Wuxian that Lan Wangji would kill for, that Lan Wangji would stand beside, that Lan Wangji would live for.

4. Meeting Songxiao

As much as I love the unnameable ache of Wei Wuxian never meeting Xiao Xingchen and learning only about his story through secondhand sources in the novel (and the really cool parallel to that where Xiao Xingchen tells A’Qing the story of Baoshan-sanren’s ill-fated disciples: both Xiao Xingchen and Wei Wuxian learn of each other only through the eyes of others, and that is Very Neat), I think the reversal that this meeting in episode 10 sets up wins out just slightly.

I said once in the tags on one of my posts that “songxiao is the tragic parallel of wangxian” and like. Yeah. Basically! If we take songxiao as romantic, the arc of their relationship happens inversely to wangxian, and that parallel is so much clearer and stronger when we have wangxian meeting songxiao in their youth.

The scene of their meeting really does have that Mood™ of uncertain youth seeing happy and secure adults living out the dreams that they’re afraid to name. Wei Wuxian’s eager little, “oh! just like me and Lan Zhan!! Right, Lan Zhan??” when songxiao talk about cultivating together through shared ideals and not blood is. Well, it’s Something.

When they meet again at Yi City, there’s a greater heaviness to it. So this is what happened to the people you once dreamed of becoming! Wangxian have already come to a point where they have an unspoken understanding of their relationship, but Songxiao have lost everything they once had. When Song Lan looks at wangxian, it’s like looking at a mirror of his past, and everyone in attendance knows it.

To me, that unspoken parallel is really emotionally and thematically valuable. All that good, and here is the tragedy that came of it.

okay, look! I managed to keep it shorter!! here are my honorable mentions: that scene where Jin Guangyao tries to hold Jin Ling and Jin Guangshan refuses to let him (it’s hating Jin Guangshan hours all day every day in this household), the grass butterfly leitmotif for Sizhui (im literally crying right now about it shut up), the Jiang Cheng/Wen Qing sideplot (look I know it’s wild that I actually liked that given that I headcanon JC as aspec, but I actually really like how it played out, specifically because Wen Qing and Wei Wuxian are NOT romantic—it sets up an unexpected and interesting comparison)

um. Anyways. I uh. really care about this story. And have a lot of thoughts, which I’m sure will continue to evolve. Maybe in 8 months I’ll return to this and go well, literally none of this applies anymore, but who knows! It’s how I feel right now. I cried literally three times while writing this because MDZS/CQL reached into my chest and yanked my heart right out of my body, but I had fun! *finger guns*

and like, I know I had a LOT to say about what frustrated me about CQL, but I really really hope it’s clear that I adore the show despite all of that. I talk a lot because I care a lot, and my brain only has one setting.

anon, this was like 1000% more than you bargained for, I’m SURE, (and I’m still exercising some restraint, if you can. believe that.) but I hope that you or someone out there got something out of it! if you made it all the way to the end of this meta, wow!! consider me surprised and grateful!!

time to crawl back into my hovel so I can write Lan Xichen fic and cry

(ko-fi? ;A;)

#the untamed#the untamed meta#mdzs#mdzs meme#mo dao zu shi#mine#mymeta#asks and replies#Anonymous#HOOOOOO BOY GUYS#we are just shy of 10k on this#*buries face in hands*#cyan writes#cyan gets too deep in the weeds#i will be shocked if more than like ten people read this#by the end it was just like well i guess this is just for me now lmfao#anyways. i will now. leave the internet for a while. thanks

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

So Zutara happens. Then what? War over, everyone else returns to their homes and loved ones while Aang wanders the world alone burying what's left of his culture before dying of depression next to Monk Gyatso's skeleton? Kataang's narrative purpose is to show that Aang can have belonging, bring back his people, have a life beyond being the Avatar. Without it, there's no happy ending. This could be avoided if they set up another romance for Aang after letting Katara go but they didnt.

Okay, so there is a lot to address here, and honestly, I had a hard time knowing where to begin because wow...

First of all, all I see here is how Aang feels. Why is it that whenever anyone discusses Kataang, it's all about Aang and his feelings? Even in the show, it's only ever really shown from his side and what he wants, not Katara. Does Katara have a say? Is Katara’s only purpose in life to be an airbending baby maker? Does Katara's very existence hinge on her being Aang's girlfriend? What about how she feels? What about what she wants? What about her happiness? Or is Aang's happiness all that matters, and Katara should just deal with it?

Now for the culture argument. I want to point out that no genocide is ever really successful in wiping out an entire group of people. Air nomads are literally nomads meaning they move around a lot. It's in the name. This means that there are most definitely other airbenders out there hiding too afraid to come out until after the war is over. But, let's say we go with all the airbenders are dead narrative, then it makes even less sense for Kataang to happen because that means the entirety of the future of one nation depends on how many airbending babies Katara pops out. So this plan is stupid. But Aang is 12, so this plan might make sense in his brain. However, as he grows up, he would come to the obvious realization that if he wants to bring back the airbenders he needs to make a lot of babies with a lot of different women, so monogamy makes no sense and Katara would likely not be down for her boyfriend/husband "planting his seed" in every willing woman given that she's from the water tribes where family units are central to her culture.