#all these ancient greek poems are about war

Note

hello!!! idk if this might be too late but pls could you share your will and nico asklepious au plot......?... very interested with morally grey will.... thank you for your service

big

asklepios au is basically just ancient greece au, somewhat historical fiction?., set post greek-roman war, will and nico become friends and then nico dies and then will brings him back to life and then will dies and then becomes immortal is the basic plot

morally grey will is that he attempts to cheat death and basically commits blasphemy, also that he may be willing to bring people back to life for his personal gain, not out of benevolence

nico's issue is that he internalizes that his character is unnecessary and his sole use is as a tool for war

so its good-at-everything-but-fighting x good-at-nothing-but-fighting

#my guy has no piety#all these ancient greek poems are about war#and all the pjo books are about war#so i think thats the only thing i can write a#bout it#asklepios au#soup ask

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

How I teach the Iliad in highschool:

I’ve taught the Iliad for over a decade, I’m literally a teacher, and I can even spell ‘Iliad’, and yet my first instinct when reading someone’s opinions about it is not to drop a comment explaining what it is, who ‘wrote’ it, and what that person’s intention truly was.

Agh. <the state of Twitter>

The first thing I do when I am teaching the Iliad is talk about what we know, what we think we know, and what we don’t know about Homer:

We know -

- 0

We think we know -

- the name Homer is a person, possibly male, possibly blind, possibly from Ionia, c.8th/9th C BCE.

- composed the Iliad and Odyssey and Hymns

We don’t know -

- if ‘Homer’ was a real person or a word meaning singer/teller of these stories

- which poem came first

- whether the more historical-sounding events of these stories actually happened, though there is evidence for a similar, much shorter, siege at Troy.

And then I get out a timeline, with suggested dates for the ‘Trojan war’ and Iliad and Odyssey’s estimated composition date and point out the 500ish years between those dates. And then I ask my class to name an event that happened 500 years ago.

They normally can’t or they say ‘Camelot’, because my students are 13-15yo and I’ve sprung this on them. Then I point out the Spanish Armada and Qu. Elizabeth I and Shakespeare were around then. And then I ask how they know about these things, and we talk about historical record.

And how if you don’t have historical record to know the past, you’re relying on shared memory, and how that’s communicated through oral tradition, and how oral tradition can serve a second purpose of entertainment, and how entertainment needs exciting characteristics.

And we list the features of the epic poems of the Iliad and Odyssey: gods, monsters, heroes, massive wars, duels to the death, detailed descriptions of what armour everyone is wearing as they put it on. (Kind of like a Marvel movie in fact.)

And then we look at how long the poems are and think about how they might have been communicated: over several days, when people would have had time to listen, so at a long festival perhaps, when they’re not working. As a diversion.

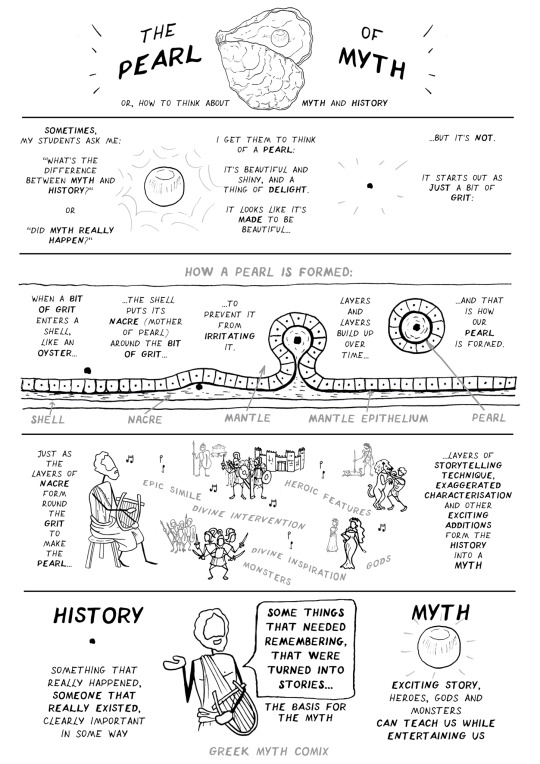

And then I tell them my old and possibly a bit tortured simile of ‘The Pearl of Myth’:

(Here’s a video of The Pearl of Myth with me talking it through in a calming voice: https://youtu.be/YEqFIibMEyo?sub_confirmation=1

youtube

And after all that, I hand a student at the front a secret sentence written on a piece of paper, and ask them to whisper it to the person next to them, and for that person to whisper it to the next, and so on. You’ve all played that game.

And of course the sentence is always rather different at the end than it was at the start, especially if it had Proper nouns in it (which tend to come out mangled). And someone’s often purposely changed it, ‘to be funny’.

And we talk about how this is a very loose metaphor for how stories and memory can change over time, and even historical record if it’s not copied correctly (I used to sidebar them about how and why Boudicca used to be known as ‘Boadicea’ but they just know the former now, because Horrible Histories exists and is awesome)

And after all that, I remind them that what we’re about to read has been translated from Ancient Greek, which was not exactly the language it was first written down in, and now we’re reading it in English.

And that’s how my teenaged students know NOT TO TAKE THE ILIAD AS FACT.

(And then we read the Iliad)

#man this week has been hard for classics teachers#Iliad#greek mythology#tagamemnon#greek myth#odyssey#homer#greek myth retellings#comix#greek myth comix#classics teacher#teaching#myth#history#ancient greek history#horrible histories#the idiots#teaching resources#teacher rant#Youtube

900 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek monster myths (1)

Various mini-articles loosely translated from the French « Dictionary of Feminine Myths », under the direction of Pierre Brunel. (You could also translate the title as “Dictionary of Female Myths” – the idea being all the myths centered around women)

Article 1: Gorgô

[Note: this mini-article is distinct from the mini-article about “Gorgons”]

The appearance of Gorgô, at the end of the eleventh chant of the Odyssey, is meant to cause fright – not just to Odysseus himself who is just done with invoking the dead, but also to the audience hearing this rhapsody (the Phaeacians listening to Odysseus’ tale), and to the very listener of the Homeric poem. Gorgô forms the dominant peak of this “evocation of the dead” (nekuia), she is the “chlôron déos”, the “green fear”. Odysseus’ mother, Anticleia, just disappeared back again nto the Hades – the hero wishes to summon other shades, such as those of Theseus and of his former companion Pirithous, “but before them, here is that with hellish cries the uncountable tribes of the dead gathered”. And Odysseus adds: “I felt myself becoming green with fear at the thought that, from the depths of the Hades, the noble Persephone might sent us the head of Gorgô, this terrible monster…” (633-635). It is barely an apparition, it is the possibility of an appearance, but it is enough to terrorize the living.

Jean-Pierre Vernant, in his work “La Mort dans les yeux” (Death in the eyes), establishes the link which ties together Gorgô and Medusa. Because Gorgô is more than a singular unification of the three Gorgons: she is a superlative form of Medusa, she is what happens when her petrifying gaze survives beyond death. By studying the depictions of Gorgô in ancient statues, Vernant establishes two fundamental traits: the faciality, and the monstrosity. He explains that “interferences” take place “between the human and the bestial, associated and mixed in diverse ways”. Maybe Gorgô is, as Vernant suggests, “the dark face, the sinister reverse of the Great Goddess, of which Artemis will most notably be the heir”. But Gorgô is also placed in the function of watchful guardian of the world of the dead, a world forbidden to the living. The mask of Gorgô expresses the radical alterity of Death and the dead.

Article 2: The Graeae

Daughters of Keto and Phorkys (they are thus also called “The Phorcydes”), sisters of the Gorgons, these divinities of shadows, which were born as elderly women and doomed to share one eye and one tooth for all three, appear exclusively in the tale of Perseus and Medusa.

The most ancient mention of the Graeae comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, which only counts two of them and names them Pemphredo and Enyo (Enyo was also the name of a goddess of war within Homer’s Iliad). The third of the sisters appears within a fragment of the Athenian logographer Pherecyde: Deino (“The Dreadful”), later called Persis by Hyginus (in his “Preface to fables”). Other authors, like Ovid, prefer to stick with two Graeae. Hesiod makes a quite flattering portrait of them: he makes them elegant goddesses with a “beautiful face”, even though they were “white-haired (understand “having white hair due to old age”) since birth”. And while their very name means “old women”, the Antique iconography actually follows the Hesiodic model: the depictions of the sisters as disfigured by the effects of time are quite rare… At most the artists will just put a few wrinkles. These mysterious hybrids between youth and old age, virginal seduction and sinister ugliness, finds an echo within a few lines from Aeschylus “Prometheus bound”: “Three ancient maidens, with swan bodies, that share a single eye and a single tooth, and who never receive a look from the shinng sun or the crescent of the night.” Aeschylus had an entire tragedy written about them (Phorcydes) which was unfortunately lost – but Aristotle wrote about it in his “Poetics” and implies that the play insisted on their monstrous aspect, placing them within the legendary area known as “the gorgonian fields of Kisthene”, and closely associating them with their sisters, of which they form a reversed image. Indeed, the Gorgons have a very powerful eyesight which no mortal being can face, while the Graeae have an extreme form of blindness. This trinity of women, old by nature, can also be understood as the antithesis of the three Charites, the Graces which embodied eternal youth.

The Graeae seems to have only a role within the myth of Perseus. And, outside of a few details, this legend does not change much from Pherecyde to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, passing by Lycophron, Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca, and Hyginus’ Astronomy. In all those versions the Graeae are the jealous keeper of the secret path that leads to the Gorgons, and Perseus must steal their eye in order to obtain the knowledge needed to reach Medusa. However, Pherecyde did change an element: according to him the Graeae do not protect the path leading to the Gorgons, but rather the path leading to the nymphs that hold the magical items Perseus needs to fight Medusa.

Due to their limited presence in Greek mythology, the Graeae have quite a poor cultural posterity. In the 19th century Goethe will remember them: in his “Second Faust”, Mephistopheles appears under the guise of “Phorkyas”, a monster with only one eye and one tooth. In the world of paintings, Edward Burne-Jones, who created a true “Perseus cycle”, had a strong interest for them: he worked for a very long time on a painting of the Graeae. Their face is barely visible, but the cloth that wraps itself around their body is menacing ; they are within an arid desert, under a dark sky heavy with clouds – they perform a sinister dance, in a mockery of the Graces. Perseus comes to steal their eyes, and the grey color that invades all the nuances of the picture symbolizes the unique presence of those strange crones, both disquieting and pitiable.

Article 3: Echidna

Echidna, “the viper”, is according to Hesiod the daughter of Phorkys and Keto, themselves born of Pontos, the Sea, and Gaia, the Earth. Echidna’s sisters are female monsters like her: the Graeae, and the Gorgons. Hesiod describes her as having half of the body of a “fair-cheeked nymph”, while the rest of her body is the one of an enormous, big, cruel, spotted and terrible snake which “lies within the secret depths of the divine earth”. Echidna as such belongs to this large mythological family of snake-women, of which the most famous case in France is the fairy Mélusine. But unlike Mélusine, Echidna can never leave the snake-half of her body, and thus a better French heir would be Marcel Aymé’s depiction of the vouivre with her cohort of vipers.

Theodore de Banville, when he imagines Hesiod scolding him for sanitizing Classical mythology, makes of Echidna the symbol of the archaic mythology: he tells him that he is “making a toy out of the history of the gods” by depicting Love as “a sweet child, free of carnivorous appetites, ignored by the Furies and by bloody Echidna”.

Echidna precisely appears as a being led by an amorous desire within Herodotus’ tales, that he claims to have collected among the Greeks of Pontus Euxinus: as Herakles was sleeping, Echidna steals his horses away. She only agrees to give them back if he sleeps with her. When Herakles leaves her, she tells him that she will bear three sons from their union. He advises them to only keep with her one that would be able to bend a bow just like him, and to force the others to leave. She does that, and this favorite son is supposed to be the one that created the Scythian people. This meeting between Herakles and Echidna might be derived from the famous encounters between Herakles and three of Echidna’s other children: the Nemean Lion, the Hydra of Lerna, and Cerberus.

In Aeschylus, Orestes compares his mother, Clytemnestra, to “a horrible viper”. Sophocles has Creon call Ismene, which he believes to have helped Antigone, “a viper that slid in my house against my will to drink my blood”. These examples show a link between the Ancient metaphorical speech, and the mythological allusions. Indeed, only the context can allow us to determine if these authors meant “viper” as a common name, or as a proper name: as “Viper”, “Echidna”. But it confirms the idea that, in Ancient Greece, Echidna is a monster born of an archaic fear of the women, and embodying their supposed perfidy.

#greek mythology#graeae#gorgon#gorgo#medusa#echidna#greek monsters#female monsters#ancient greek monsters#greek myths

78 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I read your post about the difference between Ukrainian and russian literature, with a couple of quotes that looked really promising. Could you tell me what books or poems was quoted? And if you have the will, could you list Ukrainian literature references? I know Russian invested a lot to get their literature translated and I think it is time we make Ukrainian literature more known.

Hi! Thank you for the ask. I suppose you’re talking about this post, so here are the quotes mentioned in it, as well some links to Ukrainian literature.

“Ти знаєш, що ти людина” means “Do you know that you are human”. It’s from a poem by a Ukrainian poet Vasyl Symonenko (full English translation here). In the USSR, a human was just a screw in the system, easily replaceable. The Soviets didn’t care about individual people, only about the whole. You were supposed to die for the sake of the system if need be. And Symonenko’s poem is the opposite. It reminds us that each of us unique, that every human deserves happiness and freedom. The poet died after he was beaten up by the local militsya.

“Тварь ли я дрожащая или право я имею» is something like “Am I a trembling beast or do I have the right” is a quote from Raskolnikov, the protagonist of “Crime and Punishment” by russian writer Dostoyevsky. Raskolnikov says this as he thinks he has more rights than others and is superior to them. He divides humanity in two categories: those who have the right (who don’t need to care about laws and rules) and “trembling beasts” (who must be slaves).

“Борітеся й поборете” means “Keep fighting — you are sure to win!” It is from a poem “Caucasus” by Taras Shevchenko, the most famous Ukrainian poet. Full english translation. At the time of the writing, the russian empire was at war in the Caucasus region. Russia said that this war is actually needed to give the locals “the civilisation”, “russian laws” etc. Shevchenko gives a satirical characterisation of the empire and calls out against the war. He also encourages the locals to fight with the quote above, because “the right is on their side”.

Another writer who described the russian war in Caucasus is a famous and largely celebrated russian poet Mikhail Lermontov and his poem “Izmail Bey”. “Пускай я раб, но раб царя вселенной” - “Maybe I’m a slave, but I’m the slave of the ruler of the world”. Ah yes, the mysterious russian soul. No wonder they don’t protest.

Lermontov also wrote a poem glorifying a gang rape by the military. Here’s a video with English subtitles about Lermontov and what the hell was that poem (TW for the poem. 18+)

Ukrainian literature was always about fight for freedom, because that’s what our people always wanted more than anything. Meanwhile russian literature justifies imperialism all the time.

Links to translations of Ukrainian literature (for free!)

I am (romance) by Mykola Khvyliovyi, a psychological novel about Bolshevik revolution

Forest song (english, polish) by Lesia Ukrainka, a drama about mythological creatures in a Ukrainian forest

The city(part 1, part 2)by Valerian Pidmohylnyi, an urban novel. Recreates the atmosphere of Kyiv

Eneida by Ivan Kotliarevskyi is a parody of the classic poem where the Greek heroes are Ukrainian cossacks, describing Ukrainian customs and traditions

Zakhar Berkut by Ivan Franko is a historical novel about the struggle of ancient Carpathian communities against the Mongol invasion

Enchanted Desna by Oleksandr Dovzhenko is a cinematic novel that consists of short stories about the daily life of the author as a child in a Ukrainian village.

Tiger Trappers by Ivan Bahrianyi - a story of a political prisoner who escaped Gulag and lives in taiga with local hunters. One of my personal favourites.

Poems and stories by Ivan Franko

Contemporary Ukrainian literature in English (not for free)

What we live for, what we die for by Serhiy Zhadan - selected poems by a Ukrainian musician and poet

Apricots of Donbas by Lyuba Yakimchuk - about the East of Ukraine

The voices of Babyn Yar by Marianna Kiyanovska about the history of Babyn Yar in Kyiv

Life went on anyway by Oleg Sentsov, who was kidnapped from his home in the occupied Crimea and forced to go through a russian military trial

Fieldwork in Ukrainian sex by Oksana Zabuzhko

Also here you can buy a book “Torture camp on paradise street” by Stanislav Aseyev, who survived a russian concentration camp and described what it was like.

413 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I’m pretty new to the world of Achilles and Patroclus (I read The Song Of Achilles last month) and I just saw your post about your love for them. When you said “there's just so much stuff out there about them (tsoa, hades game, the iliad, a bunch of other myths and adaptations, non fiction books, academic papers etc)” I was wondering if you could touch on the other myths and adaptations part maybe? I’m not exactly sure where to begin there but I would appreciate any guidance you could give!

Oh boy I don't know where to start either because there's a LOT. I don't want to overwhelm you so I'll just list a few key myths and adaptations off the top of my head:

Adaptations

So as far as adaptations go, I will include works where both Achilles and Patroclus show up and that are inspired by the Iliad.

Hades Game: I'm pretty sure you're already familiar with this, just mentioning it just in case!

Aristos the musical: it's a musical as the name suggests, and it revolves around Achilles and Patroclus' lives from Pelion all the way to Troy. It's really lovely and has made me emotional on numerous occasions and I love revisiting it every so often! It also has a Tumblr account: @aristosmusical

Troilus and Cressida: this is Shakespeare's take on the Trojan War and it's quite interesting, not really faithful to the Iliad but offers a sort of different perspective on the characters and the events that led to Hector's death.

Achilles (1995) by Barry JC Purves: it's a short stop motion film using clay puppets, it's on Youtube and it's only 11 mins and I think it's worth a watch! I find it very compelling visually and any adaptation where Achilles and Patroclus are lovers is a plus in my book 🫶

Holding Achilles: this is an Australian stage production by the Dead Puppet Society, I really enjoyed it and I found it an interesting blend of TSOA and Iliad Patrochilles, which also featured some cool new elements that I hadn't really seen before. It used to be free to watch for a while but now I think you have to pay to watch it, there's more info on their website.

The Silence of the Girls: a novel by Pat Barker, it's a take on the events of the Iliad mostly through Briseis' eyes, I personally didn't really like the book or the characterisations but hey both Achilles and Patroclus are in it so it might be worth a read.

There are some other novels I've heard of where Achilles and Patroclus appear (A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes, Wrath Goddess Sing by Maya Deane) and also a TV show called Troy: Fall of a City but I haven't read/watched them so I can't really rec them

Myths

Most myths revolve around Achilles, there aren't that many with Patroclus I'm afraid, but here are some of my favourites:

Achilleid by Publius Papinius Statius: this is an epic poem about Achilles' stay on Skyros disguised as a girl and his involvement with Deidameia. It's interesting but I'd personally take the characterisations and events in it with a grain of salt because Romans were notorious for their unsympathetic portrayal of Greek Homeric heroes but it's still a cool thing that's out there and free to read online.

Iphigenia at Aulis: a tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Euripides, it's basically the dramatised version of the myth of Iphigenia's sacrifice in Aulis which predates the Iliad, there are many obscure versions of this myth but Euripides' sort of updated version is my favourite, I will never shut up about this play!! Lots of a nuance and very interesting portrayals of Achilles, Agamemnon, Menelaus, Clytemnestra, Iphigenia and pretty much everyone in there, well worth a read.

Lost plays: there are several plays in which Achilles appears but that have been lost or survive only in fragments, but two of my favourites are Euripides' Telephus and Aeschylus' Myrmidons. Telephus takes place before the Trojan War, while the Greeks are on their way to Troy. I really like Achilles' characterisation in the fragments that remain and also the fact that he was already renowned for his knowledge of medicine and healing despite how young he was. The fragments that survive from Aeschylus' Myrmidons I think are fewer but the play was extremely popular at the time it was presented to the public and it sparked a lot of controversy re: Achilles and Patroclus' relationship and who tops/bottoms so I think that's kind of funny lol.

There are lots of other obscure little myths about Achilles that I've picked up by reading various books, papers and wiki posts on the matter and that are just too numerous to list here, but what I will mention and that I think concludes the myths section of this post pretty neatly is that the Iliad and the Odyssey are not the only works about the Trojan War that were written, merely the only works that survived. The rest of the books in the Epic Cycle have been preserved either in fragmentary form or in descriptions in other works, and I think the Epic Cycle wiki page is a good place to start if you want to get an idea of what each of those books contained.

I hope this helped! 💙

#patrochilles#achilles#patroclus#the iliad#homer's iliad#if I remember anything else I'll probably add to this post but I think that should be enough for now#there's just! so much stuff!!#happy reading/viewing/listening 😁

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

i realise something

casa tidmouth bwba is like the odyssey where thomas, like odysseus, wants to go home but is ping ponged around the world. But instead of losing crewmembers he gains some (ace and nia). Does this make sense

funny you said that junie XD I've had homer's two epics in my reading list for quite some time now! the format of them being poems are a bit challenging for me to process the stories but I managed to get through goethe's faust so I'll just have to believe in myself

and of course!!! of course it does make sense!!! >:] now that you've mentioned it, odysseus and cstm thomas has quite a lot of similarities, from their ever-struggling journey to how they "lost" their people one by one (though like you mentioned thomas does gain new allies). both odysseus and thomas have their respective gods following them (calypso and lady respectively) especially when the fact that there are so many ancient greek myth and legends in the odyssey and how cstm has this reoccuring urban fantasy themes to it...

does this mean that act 1 is "the illiad" while act 2 is "the odyssey"? :0 the illiad focuses on the trojan war (similar to how busy act 1 of cstm is with its worldbuilding and setups to thomas' prime and downfall), while the odyssey is about odysseus' journey way home (similar to how act 2 is more mellow and thomas trying to fix things/pick himself back up while getting thrown all over the place)... oh I gotta pick up the odyssey again!!! then the illiad!!!

now I can just imagine thomas confronting diesel 10 for the umpteenth time and solemnly saying "my name is nobody... nobody I am called by my coworker, coworker, and by all my coworkers..."

#asks#juniebugsss#casa tidmouth#thanks for this ask junie! makes me think#mentioning anything related to classic literature is like opening the floodgates to the extremely nerdy part of me.... (nerd emoji)#what if... percy as penelope ..... lol#telemachus' parts of the story reminds me of journey beyond sodor and misty island rescue where thomas' folks try to rescue him#.... without the slaying of the suitors of course.#btw I looked up the odyssey audiobook on youtube and by jove it's 11 hours long?

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know, I’ve been thinking a lot about the Palestinian conflict recently. My heart goes out to all the innocent victims, men, women, children. I could have been them, I’m not special. I am just very, very lucky.

So I found myself thinking about the concept of war. Which is one of the oldest things in the world. It’s sad, very sad that while facing something slightly different from us, one of our first instincts was to fight it and eventually kill it.

And I’ve been thinking about one of the most ancient wars we have a record of, the Trojan War, which might have happened or not, but there are some details that make it look very, very real.

I’m sure you heard of this passage: the final goodbye of prince Hector, the greatest Trojan warrior, to her wife Andromache and their son Astyanax, before going to fight in duel with the strongest greek warrior, Achilles.

He leans in to kiss the newborn in his wife’s arms one last time, but is unable to do it because of his helmet. While he laughs with Andromache, Astyanax is frightened and starts to cry.

The beauty of the whole scene elevates this poem to something completely different from what it was supposed to be, but this little moment, this moment alone is absolutely heartbreaking.

Think about how Astyanax doesn’t even recognize his father. And how the helmet he didn’t even try to take off keeps him from showing affection to his only son.

A small, powerful image of how dehumanizing war can be.

How the most righteous, loving man can turn into an unrecognizable shadow.

And it takes really, really little for that to happen.

Maybe it’s stupid, I don’t know. I was just thinking about it.

Thinking about how many children cried their eyes out, and screamed until their lungs were soaking in blood, at the sight of those men.

🇵🇸

#free gaza#gaza#gaza strip#palestine#palestinians#war crimes#israel#humanity#human rights#trojan war#the iliad#hector#andromache of troy#astyanax#greek mythology#homer

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a Greek i find hilarious and bitter that people still remember the ancient tales of our ancestors and are studied globally hoe well written they were but we modern Greeks don't produce that anymore like why?

Where did all the creativity go instead of making the same stories everyone globally make that sometimes don't even reflect our society?

I understand what you mean cause I've heard the same comment many times, but let me come to this from another angle.

Fuck what foreigners think. The ancient Greek works have great merit and no one in the world is wrong for studying them and appreciating them. However, the overstudy of these manuscripts has led to needless over-analyzing of texts and the overlook of other great Greek works. The Western world has focused so much on ancient Greek works and has talked only about them for such a long time that more than half the world has forgotten that Greeks existed beyond that era.

We have GREAT literary Greek works from medieval times. It wasn't "the Dark Ages" for us, baby! I'm talking about the Alexeiad, the Digenes Akritas Epic cycle, the satiric works "Timarion" and "Mazaris", the poem the "Spaneas", the (huuuge) "Fountain of Knowledge" by Ioannis Damaskinos, the historical work of Ioannis Malalas, the works of Mihail Psellos, the HUNDREDS of medical and scientific books, and other works that influenced the East and the West alike. That's just the tip of the iceberg!

Why don't we feel proud about those? Because we don't know them. Why don't we know them? Because it's not trendy to study these periods.

We also don't talk about the hundreds of amazing writers we had the last century - including those who got Nobels - because that's not trendy right now.

We have to stop seeing the value of Greek literature through the eyes of foreigners. We have to promote Greek works because we can't just wait for a Shannon in New Jersey, US, to discover it and like it, in order for us to appreciate it too.

Also, we cannot re-invent the wheel. Our ancestors wrote some great stuff for their era. In 2023 this stuff is still great but it's not THAT revolutionary. So there's no comparison in regards to novelty. But we can produce good works regardless.

Greece is not a colonial power or a former colonial power like the European "Big Powers" (these 8 countries), or an empire like the US. Our nation is still recovering for 400-600 years of slavery and occupation AND the dozens of traumatising conflicts and wars that came after that. We can't expect the same growth at the same numbers as these luckier countries. We can't afford as a nation to have extremely popular events and promote the arts like they do in LA, or in Berlin, or London. Let's be kind to ourselves.

In continuation of the previous point, Greece today doesn't have enough powerful publishing houses to back great writers. Our writers, except 4-5 names in the whole country, don't see a penny from their work even after selling hundreds of copies. Even if you earn something, it's not even enough for a month's groceries. So writers either have to choose to spend only 10% of their time writing, or 80% of their time writing and live penniless.

The creativity is there, but Greeks rarely have the time and resources to pursue their writing passion to the point of greatness.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I.

Some general points when it comes to ancient Greek culture and certain attitudes relevant to the topic:

-both men and women were supposed to show self-restraint when it came to sex; it was a virtue, and furthermore, self-restraint and moderation (in all things, but especially this) was part of what made a man "manly", if you will. Women being modest and chaste were similar for them, and an extra step further than a man's "moderation".

-At the same time, women were considered "naturally" more sexual, and having less self-control (that was why it was extra important they exercise self-restraint and being chaste), which leads into the connected idea that a man who does not… becomes feminized.

(Something illustrated by Lucian of Samosata's A True Story, in the very first parts of it, and talked about below:)

For the Iliad specifically, Christopher Ransom in his Aspects of Effeminacy and Masculinity in the Iliad (2011) summarises up a couple other points:

"In the Iliad, childishness and effeminacy are often referred to in order to define masculine identity. Women and children are naturally not operative in the adult male world of warfare, and so can be clearly classified as ‘other’ within the martial sphere of battlefield insults. Masculine identity cannot be formed in a vacuum, and so the feminine or the childish is posited as ‘other’ in order to define the masculine by contrast."

and "Idle talk is characterised as childish or feminine, and is repeatedly juxtaposed with the masculine sphere of action."

as well as "Effeminacy is linked to shame […]; if acting like a coward is a cause for shame, and prompts Menelaos to call the Achaians ‘women’, then effeminacy is seen as shameful in the context of the poem."

And while neither dancing nor sex are something that a man who engages in will become effeminate for, the former is explicitly posited as a peace-time pastime only, and sex is only to be had at the right time (and in the right amount). So, in the Iliad's (as well as the whole war) circumstances, neither of those two activities are proper to prioritise, and are at points set up in juxtaposition and contrast to war and martial effort.

Additionally, physical beauty alone doesn't make a man in any way feminized - otherwise quite a few male characters would be effeminate! - and in fact, a well-born, "heroic" man will be beautiful because it befits his status. (Insert basically any big-name male character in Greek mythology here.) But, there's a limit and some caveats to this; physical beauty in a man (not a youth) must be balanced out against other "virtues", and if, in especially the context of war as in the Iliad, a man's martial ability is lacking, his handsomeness becomes a source of scorn instead, because he can't "back it up".

Here's our most notable "offenders":

Nireus of Syme, who in the second book of the Iliad is called the most beautiful among the Achaeans after Achilles, but "he was weak, and few men followed him". Syme is a small island, but I don't think the "few men" here is supposed to be assumed because of a lack of numbers on the island. His beauty is all there is to him, and no one wants to follow him because he's not sufficiently (manly) able in war.

Nastes and/or Amphimachus of Miletus, wearing gold in his hair "like a girl", which the narrator then calls him a fool for and that he will be stripped of those pieces of jewellery when Achilles kills him, and, again from Ransom's article; "Thus, the effeminised male, characterised by his feminine dress, is brought down by the ‘proper hero’, and the effeminate symbolically succumbs to the masculine."

Euphorbos, the man who first injures Patroklos - this is an edge-case, because the text itself isn't obviously condescending or condemning Euphorbos compared to Nastes/Amphimachus. It simply describes him wearing his hair in a style of hair ornaments that pinches tresses in at the middle. But, the narrator still goes to the effort to make this extra description, not just the more general/usual mention of the hair being befouled in the dust as the man killed falls to the ground.

(In the intent of being somewhat exhaustive, two other potential edge-cases:

Patroklos, who does perform some tasks at the embassy dinner in Book 9 that would usually be done by women. And it's not as if Achilles doesn't have women who could deal with the bread and similar. It's not remarked on, or marked in the text in any way, compared to the other characters previous.

Menelaos, even more of an edge case, but like Patroklos he's described as gentle, and by Agamemnon and Nestor's indictment doesn't act when he should, being more prone and willing to let Agamemnon take point. Could say it ties into how Helen in the Odyssey is the more dominant partner in terms of social interaction, as well.)

And then there's our last "offender", who we see more of in terms of his lacking in living up to proper (Iliadic) masculinity; Paris. Before going into that, though, I want to touch on something else.

II.

That being what the idea of the Trojans being "barbarians" does to the Trojans in later sources. In the Iliad itself, while the Iliad does have a pro-Achaean bias, the Trojans and their allies aren't really portrayed in the same way as happens later (but not consistently so), coming into shape during and after the Persian Wars. In summary, it's during this time the Trojans gain the negative stereotypes of the eastern "barbarian"; luxurious, slavish (but also tyrants! one basically ties into and enables the other), and effeminate.

Not all "barbarians" were considered the same, with the same stereotypes attached to them; northern (Scythians, etc.) barbarians were considered violent and warlike, "savage" if you will.

Edith Hall's book Inventing the Barbarian (1989), is all about this, but have a couple hopefully illuminating quotes about how these stereotypes were expressed, especially in drama/fiction:

So what happens is that all Trojans get tarred with this barbarism brush, as illustrated in the Aeneid (by a character, not the narrative); "And now that Paris, with his eunuch crew, beneath his chin and fragrant, oozy hair ties the soft Lydian bonnet, boasting well his stolen prize."

Notes here: 1. This is said by a character, not the narrative itself, and someone using this as an argument against Aeneas and his Trojans, but the stereotype itself isn't something new; 2. "That Paris" = Aeneas. While this might be more about Paris as a seducer and abductor of Helen, given the emasculation of the rest of the Trojans and then the additional effeminate touches with Aeneas' supposed dress and hair, I'd say it's not just about that; 3. The word translated here as "eunuch" (semivir, "half-man"), by a quick look in Perseus' word tool, is also straight up used about effeminacy, though of course a eunuch wasn't a "full"/proper man and often viewed as effeminate, too, so they're tied together.

Even with this development, in looking at the Iliad itself obviously not all Trojan characters would be equally easy to cast in an effeminate light. Again, we come back to the easiest target, the one who, by the way he's juxtaposed against another character who exemplifies the "war as (part of the) male gender performance" in the Iliad, stands outside of that. The one who basically, as he is portrayed in the Iliad, by the stereotype of the eastern barbarian becomes the archetypal "eastern barbarian Trojan".

Paris.

III.

So, let's talk about Paris!

At the very basic level when it comes to Paris and his place in the Iliad, is that he is the foil and contrast to his brother Hektor in specific, as a warrior and as a man. But in that specific reflection he is also the contrast against every other male character, Achaean and Trojan, in the Iliad.

What does this mean?

-Cowardice; he's slack and unwilling as Hektor accuses him of. No way to know if this is specifically because he's always afraid, as in the moment we see before his duel against Menelaos, since being unwilling to fight in deadly combat could be for many different reasons. (He is not always slack and unwilling, however; he is out there on the battlefield with the rest at the beginning of Book 3, and after Book 6 he is, as far as we know, out there with the rest of the Trojans, from beginning to end. His unreliability in his martial efforts is another angle.)

-He is one of, if not the worst, fighters among the commanders, on both sides. His martial prowess isn't up to snuff and as we see in Book 3 where Hektor calls him out on retreating, he notes that Paris' beauty would have the Achaeans believe Paris is one of the Trojans' foremost champions. But he's not, both because of his cowardice and his lack of martial ability, and tying into this, then, is;

-Paris' beauty. As noted earlier with Nireus, physical beauty not backed up by martial prowess makes you less than, and the epithet used for Paris to call him godlike is specifically about his physical looks. There are other epithets (also sometimes used of Paris) that mean "godlike" in a more general way, but the one most often used of Paris is specific. And, that particular word is what's used when Paris first leaps forward in Book 3; the narrative is using theoeides every single time Paris' name is used in that scene, and so we get something like this, from J. Griffin in his Homer on Life and Death (1980): "…the poet makes it very clear that the beauty of Paris is what characterizes him, and is at variance with his lack of heroism…" as well as from Ransom in his article: "Again the suggestion is that Paris’ beauty is empty, and that he is lacking the courage or other manly characteristics that would render it honourable. […] Paris is set against Menelaos, a ‘real’ man by implication, and he is told that his skill with the lyre and his beauty would be no help to him then."

-His pretty hair gets insulted at least once (by Hektor) and potentially twice, the second time by Diomedes in Book 11 (the phrase used is uncertain whether it's about Paris' hair or his bow; that it could be his hair, being worn in a particular style, has been an idea from ancient times). And we know what sort of fuss the Iliad makes of pretty hair in men who do not otherwise live up to being properly masculine according to its ethos.

-Being an archer. The bow wasn't the manliest weapon around, and the Iliad disparages its use on the battlefield (selectively!). Paris is basically our archetypical archer, who gets insulted for being an archer and less manly because of that.

-His focus on dancing and music, as brought up by both Hektor and Aphrodite (and, though in a more general insulting context with other sons being mentioned as well, by Priam). The problem is, again, of course not his skill or interest in and with these things, but that he is better at these than combat and that he shows more interest in them and probably puts more effort in when it comes to them, too.

-His sexuality. As noted earlier, a man should show moderation and self-restraint. Paris, giving in to his desires and having sex in the middle of the day and during a tense moment, even if the forces aren't supposed to be fighting at that very point in time (neither he nor Helen would know Athena has induced Pandaros into breaking the truce), is certainly not showing any sort of moderation. I can't emphasize enough how much this isn't some epitome of macho male sexuality and prowess. Rather, this is the epitome of feminized weakness to sex, and Paris throws himself whole-heartedly into it.

-Paris' physical presentation. There is a lot of focus on his dress and how it makes him look (Aphrodite practically objectifies him for Helen's pleasure when she describes him to her!), and that his clothes are gorgeus. Again, have a quote from Ransom about that Aphrodite-Helen scene: "This scene captures his essence perfectly. Once more Paris’ looks and dress are emphasised […] and, in Aphrodite’s speech, the poet explicitly disassociates him from his martial endeavour." Connected to this we have his first appearance earlier in this book, where he's described as not wearing full armour but a leopard pelt. Here's Griffin again: "[…] so he has to change into proper armour before he can fight - and we are to supply the reason: because he looked glamorous in it."

Now, I don't think it's that simple, because other people wear animal pelts in the Iliad; Agamemnon and Menelaos both do so, as does Diomedes and Dolon. However, Agamemnon and Menelaos both wear theirs as part of a full martial dress and they're clearly meant as part of a display of authority and martial prowess and Diomedes, though he's not otherwise fully armoured as this is part of his dress during the meeting before the night raid, is clearly meant to be similarly glorified (Dolon is more of a question, considering how he's portrayed otherwise). Paris is specifically not wearing a full set of armour, even if he apparently has it at home, so in the end I'd agree with Griffin that, given the other instances of Paris' clothing being extravagant/beautiful, this is indeed an instance of "because he looked glamorous in it".

But as Ruby Blondell puts it: "The destructive power of "feminine" beauty is most ostentatiously displayed, among mortals, in the person not of Helen but of Paris. In contrast to the veiling of her looks, Paris's dangerous beauty is displayed, glorified, and also castigated. […] His appearance is unusually decorative, even in battle. His equipment is "most beautiful" (6.321), glorious, and elaborate (6.504), and his outfit includes such exotic details as a leopard skin (3.17) and a "richly decorated strap (polukestos himas) under his tender throat" (3.371)." (Helen of Troy (2013))

-His attitude towards the whole (Homeric) heroic ethos of the Iliad. Not just his unwillingness or lack of martial prowess, but rather the "personal motto" he expresses to Hektor in Book 6; "victory shifts from man to man". And, while I wouldn't say this is at all a typical mark of an effeminate man in terms of the Ancient Greek outlook on these matters, you do have to set it in connection to his other martial "failings". As Kirk in his The Iliad, a Commentary, vol. 1 (1985/2001) says: "He thus attributes success in battle to more or less random factors, discounting his personal responsibility and performance." and, another point of view from Muellner in The meaning of Homeric εὔχομαι through its formulas (1976) about this same "motto":

-As a brief little point, when it comes to his being a lyrist; that, too, was often edged in ideas of effeminacy, so while, of course, no man is effeminate just because they may take up the lyre at some point, if you dedicate your life to it, that starts to have an effect on how you're viewed.

So what you have, then, in sum is Paris being very much non-masculine - or at least not conforming to the martial and cultural expectations and mores of the Iliad's/the Homeric masculine ethos. Even if you add in/change some of how the Trojans might view things, Paris would without a doubt still be non-conforming. Myth-wise, he certainly is so, both before and after the Persian Wars and the changes to the Trojans' general perception at the hands of the Athenian tragedians happened.

Here's Christopher Ransom again, to tie things up: "If gender is performance, Paris is simply not playing his part; if ‘being a man’ requires a concerted effort and a conscious choice, it seems as though Paris’ choices are in opposition to those of his more heroic brother."

IV.

And lastly, some scattered quotes from ancient sources about Paris, roughly ordered from earliest to latest:

"No! my son was exceedingly handsome, and when you saw him your mind straight became your Aphrodite; for every folly that men commit, they lay upon this goddess, [990] and rightly does her name begin the word for “senselessness”; so when you caught sight of him in gorgeous foreign clothes, ablaze with gold, your senses utterly forsook you." (Euripides, Trojan Women)

-This one is pretty straightforward, especially keeping in mind all the above and Edith Hall's discussion of the words connected to eastern "barbarians" by this point.

"Vainly shall you; in Venus' favour strong,

Your tresses comb, and for your dames divide

On peaceful lyre the several parts of song;

Vainly in chamber hide

From spears and Gnossian arrows, barb'd with fate,

And battle's din, and Ajax in the chase

Unconquer'd; those adulterous locks, though late,

Shall gory dust deface." (Horace, Odes)

-Double focus on his hair, and through that, Paris' behaviour, all of it disassociating him from martial effort and into a more "feminine" sphere.

"[…]shall we endure a Phrygian eunuch hovering about the coasts and harbours of Argos […]" (Statius, Achilleid)

-Again, the "eunuch" here is "semivir", so Paris is explicitly emasculated and made out to be effeminate.

"And he washed him in the snowy river and went his way, stepping with careful steps, lest his lovely feet should be defiled of the dust; lest, if he hastened more quickly, the winds should blow heavily on his helmet and stir up the locks of his hair." and

"he[Paris] stood, glorying in his marvellous graces. Not so fair was the lovely son whom Thyone bare to Zeus: forgive me, Dionysus! even if thou art of the seed of Zeus, he, too, was fair as his face was beautiful." (Colluthus, Rape of Helen)

-I don't think I need to say much about that dainty description of Paris' behaviour and the care he takes to still look as put together and beautiful for when he reaches Sparta, do I?

The second quote, though, I think deserves some comment, because Collutus twice in short order compares Paris to Dionysos, and as we saw in Hall's book, Dionysus in the Bacchae is associated not just with a foreign man, but someone who would be tarred with the stereotypes of the eastern "barbarian". And Dionysos has long, of course, been portrayed with a particularly feminized beauty, not just in drama.

On top of this, much earlier than Colluthus we have Cratinus' Dionysalexandros, a satyr play where Dionysos takes Paris' place for both the Judgement and kidnapping Helen. To note is that while the satyrs are followers of Dionysos, their uses as chorus in satyr plays wouldn't necessarily have them attached to Dionysos (often, they seem in fact to have removed themselves from him). And in this circumstance, then, Paris isn't just compared to the effeminate Dionysos, Dionysos straight up (though disguised as Paris) replaces him for a part of the play.

It all starts in the Iliad, but it certainly doesn't end there, and by the end Paris' effeminacy is just all the more explicitly stated in text as effeminacy.

(While the other sources mentioned here would either have to be bought or found… in other ways /cough, Christopher Ransom's article can be read right here: https://www.academia.edu/355314/Aspects_of_Effeminacy_and_Masculinity_in_the_Iliad )

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Young Royals and the divine disruption of eros

Young Royals enthusiasts have a lot to say about the nature of love (specifically eros, or romantic and/or sexual love) in the show’s universe. Usually they identify an element of the divine in the love we see onscreen. The show itself nods to this with soundtrack choices like Elias’s “Holy” and through some of the imagery and filming choices. (Someone else can probably speak to that better than I can, and probably already has.)

But what does it mean, that love/eros has an element of the divine? Is divinity always benevolent, or kind? Does it always encourage someone toward more compassionate behavior? In a Christian context, we usually think of “love” as being associated with moral goodness, or at least a kind of selflessness or compassion. As a former classics major, however, I can’t help but look at YR’s divine eros through the lens of the ancient Mediterranean myth and folklore. Here, the divine is more a force of nature, and far more morally neutral.

Some background: in the ancient sources Greek gods and goddess are less like immortal, superpowered humanoid beings, and more like abstract and/or natural concepts personified. In Greek mythology, Aphrodite is the divine figure most associated with eros, and she is a powerful and at times vengeful goddess who should not be underestimated. Modern sources (and even a few ancient sources) tend to downplay or soften her influence—leaning into this idea of a beautiful goddess playing matchmaker for lonely individuals—but even when she’s bringing companionship into a person’s life, she’ll still shake things up in the process. The Trojan War begins because Paris chooses Aphrodite’s realm as his definition of beauty/excellence, and Aphrodite sets Paris and Helen’s relationship in motion.

What makes Aphrodite—and by extension, eros—so dangerous is that she is so disruptive to the social order. Marriages in the ancient Mediterranean tended to be arranged, and while eros certainly did exist within some of those marriages, it wasn’t a guarantee at all. You may well develop feelings for someone other than your spouse, and what if that destabilizes your marriage? You could also develop feelings for someone who makes you behave outside your assigned gender or class expectations, and then you aren’t fulfilling your class role, which causes a breakdown in the social hierarchy. Being in love may be euphoric, especially if the person you love loves you back and you’re of compatible social ranks, but it may also be unbearable if circumstances don’t work out for you. Unchecked eros can even lead to the birth of monsters, such as when Aphrodite dooms the Minoan queen Pasiphae to fall in love with a bull, which then eventually leads to Pasiphae giving birth to the Minotaur. Look at any selection of poems from the ancient Mediterranean and you’ll find as many poems cursing love as praising it.

And one of the wildest things about eros? Nothing about it is rational. People may try to rationalize their feelings of eros later, or come up with why they like a person… but feelings just are what they are. Actions can have a rational component, and an element of agency. You can technically control your actions. Still, feelings do not operate in the same way, and feelings are always trying to influence actions. Part of the reason it is important to respect Aphrodite is that she can always get you and hijack your heart when you least expect it. (Unless you’re aromantic I guess, which. Hooray exceptions?)

Let’s bring it back to the Swedish show. I think often, people want to talk about the wilmon and sargust pairings as being as far apart from one another on the spectrum as can be. I’ve even seen the idea thrown around that wilmon’s eros is the Most Real while sargust’s is Less Real, and while I get where that argument is coming from, I also don’t necessarily agree with it myself. On my end, when I look at love/eros in Young Royals as defined first and foremost not by moral goodness but by its power to disrupt, these two pairings feel very alike to me and deeply thematically connected. Moreover, they are equally exciting to watch play out onscreen. Each of the four characters involved develops feelings that conflict with something about who this character is as a person and the social role they hold. Each character at times resists their feelings and at other times gives in. Sometimes both characters give into their feelings together! (Those parts of the story are often gif’d and reblogged by tumblr, at least on the wilmon side of things.) You can also learn a lot about each character by how they deal with the disruptive power of eros, and what they allow eros to disrupt—ultimately, August tries to exert control over his romancey situation with Sara and make it fit his concept of the social order, and disrupts the well-being of the Eriksson family in the process. Wilhelm, meanwhile, is willing to challenge the structures of the monarchy and his own family because of his relationship with Simon. There’s also a lot of twists and turns along the way for each of them that are enjoyable to watch.

There’s a tendency in fandom to hold wilmon as a sort of Fixed And Unquestionable Religious Truth Of The Young Royals Universe, and I get why. There’s also a sort of tendency to see sargust as the devil to wilmon’s god, and again, I get why folks feel that way too. For me, though, I don’t really feel that way, in part because I see both pairings as equally subject to the divine nature of eros, and eros is something that is dynamic and morally neutral and constantly in flux and most of all, disruptive. I like that both pairings are a little chaotic and capable of making me feel a range of things, even if I always do come out of a YR marathon exhausted because of it. Eros is disruptive the way that war and revolution are disruptive, and sometimes they’re all happening at once, and in the end it makes a pretty good story.

Anyway, if you’re wondering, one of my favorite Greek plays is Hippolytus by Euripides, and Aphrodite is pretty terrifying there. I find her power to disrupt and destroy fascinating. And that’s probably why, against the expectations of my mlm slash-loving younger teenage self, I’m going to be writing fic about these trash-tragic horsey heteros for as long as this fandom exists and I feel compelled to do so. No apologies about that, really. You’ll all just have to put up with me.

#young royals#my meta#wilmon#sargust#me opining with my classics hat on again#the classics part of this meta is somewhat oversimplified but if you want to talk one on one i can really dig deep

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

poppies

In Flanders Fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

In Flanders Fields by John McCrae

I have always found the excerpt above, and the rest of the poem that comes after it to be pleasant to the ear, sweetly melancholic and, to be honest, more than a little creepy once you hit the threat at the end. The mental image of mostly desiccated World War I soldiers clawing their way out of the upturned soil, spilling flecks of half rotted uniform and red flowers from their bodies as they drag themselves forward after me just because I don't feel like holding a grudge against another country for a war nobody really should have been in in the first place isn't exactly what I suspect Lt. Col. McCrae was going for but its sure the picture he painted in my mind. Not cool, John. Not cool.

In other news, the poem did help make the poppy a popular symbol for war veterans that died in battle, especially overseas. These days red paper poppies are worn in jacket lapels and sold on street corners in multiple Western countries during Remembrance Day, Anzac Day and Memorial Day. Today that's pretty much the only association most of us have with the flowers but for the soldiers that lived during that time, the red corn poppies were a familiar sight, being some of the first and hardiest plants to grow in the churned up soil around trenches, the morass of no-mans-land between and yes, the freshly dug graves that grew almost as quickly as the poppies themselves across the battlefields.

Poppies were associated with the dead long before WWI however.

Hey, August babies! Let's talk about one of your birth month flowers (and keeping corpses in their graves)!

Did you know that poppies have been found in graves and carved on tombstones all the way back to Roman times? The Greeks and the Romans associated the poppy with forgetfulness and sleep. Giving the dead poppies was supposed to help them sleep in peace, though I did see one article speculating that the poppy seeds found in some graves was more akin to the old legend that the undead have obsessive-compulsive disorder and will be compelled to stop whatever they are doing to count scattered small items like seeds.

GIF by gifs-of-puppets

Who knew Sesame Street was so in touch with its darker side?

Back to the point, the Greek gods Hypnos (sleep), Thanatos (death), Nyx (night) and Morpheus (dreams) all have poppies as their flowers. Pappa means 'milk' in latin and the milky sap as well as the seeds of poppies have been used since ancient times to grant forgetfulness, peace and sleep, tracing as far back as the early Egyptian empires. Multiple opioids are made from the poppy with some of the most famous being opium, heroin, codeine and morphine, named after Morpheus for its dreamlike effect on the human brain and body. The opioid crisis has been with us since at least Victorian times and for many of the same modern reasons back then as well.

Speaking of escape from pain, Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, is associated with poppies as well. It was said that after Persephone was kidnapped by Hades, Demeter was so distraught that the gods gave her poppy seeds to help her sleep and escape her grief for a time. Afterward, the flower would spring up wherever her footsteps fell. The ancient Assyrians also associated poppies with agriculture and in fact, even today, poppies seen growing in cornfields are considered lucky and a sign of a good harvest to come.

Poppies in China are also considered lucky, or at least the smell of them is and they are a melancholic symbol between lovers too. The story I read claims that the poppies growing on his lover's grave gave a Chinese hero the inspiration he needed in battle.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz employed a poppy field to put its heroes to sleep.

Poppies should only ever be given in bouquet of thirteen. Any other number of poppies is considered unlucky.

Greek athletes would mix poppy seeds, wine and honey for an invigoration drink.

In Wales, sleeping with poppy seeds under your pillow will show you the face of your future lover or give you the answer to whatever question you were thinking of when you fell asleep. The seeds are a ward against forgetfulness.

#poppy#poppies#august#Demeter#morpheus#folklore#superstition#herbalism#cottagecore#birth flower#birth month#wizard of oz#vampire#flanders fields#anzac day#remembrance day

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

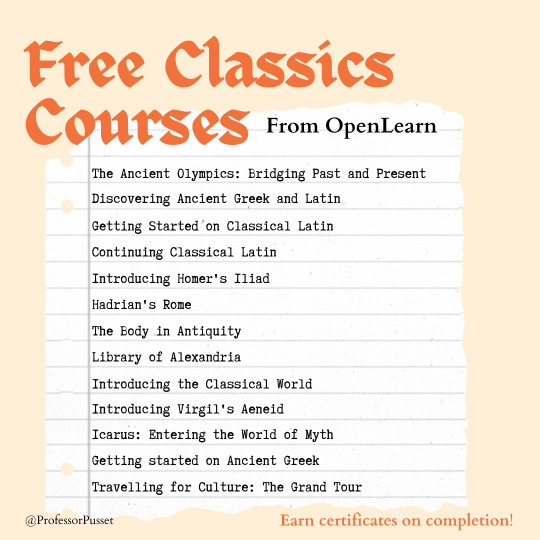

Free Classics Courses - With Certificates!

Studying "the classics" is a rich, rewarding and thoroughly enjoyable experience. Unfortunately these days, many of us lack the opportunity or resources to integrate ancient civilisations and languages into our formal education.

I, for one, am forever grateful that the advent of the digital age heralded new and interesting ways for society to share a wealth of information. Since the early noughties, I've tracked down free online courses in areas of personal interest. Naturally, the Classics is a subject I gravitated towards, and it saddened me to notice that over time free courses in the arts and humanities dwindled in favour of modern, digital, knowledge.

However, I am gladdened to share that OpenLearn (a branch of The Open University) have a growing selection of free Classics courses! All of these courses offer a free certificate to download and print on completion, and are drawn from the various undergraduate courses provided by the university proper.

These courses vary in length and difficulty, but provide an excellent starting point for anyone interested in the Classics, or who would like to sample university level content before committing to a more formal course of study.

Here is a full list of courses in the Classics category at OpenLearn, though I strongly suspect more will be added over time:

The Ancient Olympics: bridging past and present

Highlights the similarities and differences between our modern Games and the Ancient Olympics and explores why today, as we prepare for future Olympics, we still look back at the Classical world for meaning and inspiration.

Discovering Ancient Greek and Latin

Gives a taste of what it is like to learn two ancient languages. It is for those who have encountered the classical world through translations of Greek and Latin texts and wish to know more about the languages in which these works were composed.

Getting started on classical Latin

Developed in response to requests from learners who had had no contact with Latin before and who felt they would like to spend a little time preparing for the kind of learning that studying a classical language involves. The course will give you a taster of what is involved in the very early stages of learning Latin and will offer you the opportunity to put in some early practice.

Continuing classical Latin

Gives the opportunity to hear a discussion of the development of the Latin language.

Introducing Homer's Iliad

Focuses on the epic poem telling the story of the Trojan War. It begins with the wider cycle of myths of which the Iliad was a part. It then looks at the story of the poem itself and its major theme of Achilles' anger, in particular in the first seven lines. It examines some of the characteristic features of the text: metre, word order and epithets. Finally, it explores Homer's use of simile. The course should prepare you for reading the Iliad on your own with greater ease and interest.

Hadrian's Rome

Explores the city of Rome during the reign of the emperor Hadrian (117-38 CE). What impact did the emperor have on the appearance of the city? What types of structures were built and why? And how did the choices that Hadrian made relate to those of his predecessors, and also of his successors?

The Body in Antiquity

Will introduce you to the concept of the body in Greek and Roman civilisation. In recent years, the body has become a steadily growing field in historical scholarship, and Classical Studies is no exception. It is an aspect of the ancient world that can be explored through a whole host of different types of evidence: art, literature and archaeological artefacts to name but a few. The way that people fulfil their basic bodily needs and engage in their daily activities is embedded in the social world around them. The body is a subject that can reveal fascinating aspects of both Greek and Roman culture it will help you to better understand the diversity of ancient civilisation.

Library of Alexandria

One of the most important questions for any student of the ancient world to address is 'how do we know what we know about antiquity?' Whether we're thinking about urban architecture, or love poetry, or modern drama, a wide range of factors shape the picture of antiquity that we have today. This free course, Library of Alexandria, encourages you to reflect upon and critically assess those factors. Interpreting an ancient text, or a piece of material culture, or understanding an historical event, is never a straightforward process of 'discovery', but is always affected by things such as translation choices, the preservation (or loss) of an archaeological record, or the agendas of scholars.

Introducing the Classical World

How do we learn about the world of the ancient Romans and Greeks? This free course, Introducing the Classical world, will provide you with an insight into the Classical world by introducing you to the various sources of information used by scholars to draw together an image of this fascinating period of history.

Introducing Virgil's Aeneid

This free course offers an introduction to the Aeneid. Virgil’s Latin epic, written in the 1st century BCE, tells the story of the Trojan hero Aeneas and his journey to Italy, where he would become the ancestor of the Romans. Here, you will focus on the characterisation of this legendary hero, and learn why he was so important to the Romans of the Augustan era. This course uses translations of Virgil’s poem, and assumes no prior knowledge of Latin, but it will introduce you to some key Latin words and phrases in the original text.

Icarus: entering the world of myth

An introduction to one of the best-known myths from classical antiquity and its various re-tellings in later periods. You will begin by examining how the Icarus story connects with a number of other ancient myths, such as that of Theseus and the Minotaur. You will then be guided through an in-depth reading of Icarus’ story as told by the Roman poet Ovid, one of the most important and sophisticated figures in the history of ancient myth-making. After this you will study the way in which Ovid’s Icarus myth has been reworked and transformed by later poets and painters.

Getting started on ancient Greek

A taster of the ancient Greek world through the study of one of its most distinctive and enduring features: its language.

The course approaches the language methodically, starting with the alphabet and effective ways to memorise it, before building up to complete Greek words and sentences. Along the way, you will see numerous real examples of Greek as written on objects from the ancient world.

Travelling for Culture: The Grand Tour

In the eighteenth century and into the early part of the nineteenth, considerable numbers of aristocratic men (and occasionally women) travelled across Europe in pursuit of education, social advancement and entertainment, on what was known as the Grand Tour. A central objective was to gain exposure to the cultures of classical antiquity, particularly in Italy. In this free course, you’ll explore some of the different kinds of cultural encounters that fed into the Grand Tour, and will explore the role that they play in our study of Art History, English Literature, Creative Writing and Classical Studies today.

#classics#ancient greece#greek mythology#classical studies#classical education#greek#latin#the grand tour#dark academia#light academia#dark academia guide#homer#virgil#openlearn#free courses#online education

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

I apologize for falling down this rabbit hole about that "Lies We Sing to the Sea" book, and I'm trying to not get too rabid because it's like...not even out yet. So this is all speculative, I guess.

But the point of "She just read the parts that were relevant/she didn't NEED to read the whole book to understand the part with the girls" I keep seeing people make.

When *yes you do.* the hanging of the girls is a culmination of one of the major conflicts of the poem, ESPECIALLY if you are analyzing it from a gender perspective.

The whole first half of the story is essentially the trials and tribulations of Odysseus being routinely shit on by the universe (sometimes because of his own hubris, but more often by the disloyalty of his crew) until he is completely emasculated. He loses his spoils of war, his ships, his crew. He ends up trapped with Calypso- where he essentially is held in sexual slavery for 7 years. And when he escapes, he washes up completely naked and helpless, only to be rescued by the kindness of Princess Nausicaa and Queen Arete. It's a story of how he is, bit by bit, brought low.

The second half- when he returns to Ithaca, he has to assess the loyalty of those around him in secret- his son, the swine herd, the suitors, and most importantly Penelope. His wife's choices here (especially her sexual choices) are his greatest threat- if she has taken a new lower (as Clytemnestra had)- Odysseus is screwed.

Those final chapters, when Odysseus regains his bow, slaughters the suitors as they beg for mercy, tortures the disloyal goatherd- that's Odysseus regaining his power, regaining his masculinity, reclaiming lordship over Ithaca. It's violent and bloody and if THIS is how manhood and masculinity is constructed in the text? Like, damn.

Hanging the girls is part of that. They are disloyal. Their sexual choices (to sleep with the suitors) make them dishonor Odysseus, Penelope, and Telemachus. His killing them is the final act in him retaking his throne. Being a powerful man again.

It's also a big moment for Telemachus- too young to take the throne himself and a cry baby up to then, Telemachus helps in the massacre. The only time he disagrees with his father is to suggest that the girls be hanged, not given a clean death by sword, and has it done. It's a moment for him to be seen as more of a man as well.

That's why the hanging of the girls has been so haunting for so long- it's a real sticking point for a modern reader. We can often excuse violence against men and monsters. But using the slaughter of the girls as a way to assert masculine dominance feels... thorny even with historical context.

You have to understand that Odysseus has *lost* his power and been emasculated in the first half in order to understand WHY the girls are hanged at the end. They are connected.

And if your whole FEMINIST book that is tackling the issue of the hanged girls is written without that context... what exactly is it trying to comment on? What is it trying to say if it is removed from that context?

I don't know! Maybe it will have something to say, maybe it will be fine. 🤷♀️

But... would it be meaningfully different if you changed all the names and it had no connection at all to the Odyssey? What conversation is it trying to have with that text? Or is it just using that name recognition as a marketing ploy to bring in readers?

Regardless, it is *mind boggling* to me that anyone thinks that they could read, what, just Book 22 out of 24? And think they have the context they need to say something interesting here.

And I've said it before, but this is a whole issue with Greek Mythology YA. These stories are compelling because they are thorny and complicated and whether it be the Romans, the Renaissance, or American writers, our own cultural lenses often butt up against these ancient texts in ways that ask fundamentally challenging questions about sex and gender and violence and power and love and fate. And that can be...not a great fit for someone writing YA unless they really want to push the bounds of those genre conventions pretty far.

265 notes

·

View notes

Note

For Barry and Hal-

What fandoms or franchises do you think they are in or follow? Could be podcast related, Reddit forums they are a part of, movie sequels or trilogies or novels!

Definitely something that should be mentioned more in canon comics so let’s use this as a manifesting moment by detailing it out 🤭

Right off the bat, I have to make it clear to absolutely everyone that Barry is 100% a Trekkie and Hal is most likely a Star Wars fan. And while we’re on the most heated sci-fi debate, I’ll add that once Hal and Barry became friends and Barry learned more about the Green Lantern Corps he undoubtedly introduced Hal to Star Trek and successfully convinced him that it was the superior sci-fi franchise, we stan two Trekkies 😜

Now then, I don’t think Hal would be very into book series or fantasy in general but he’d definitely have a particular interest in the Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings trilogy and I think he’d try Game of Thrones and The Witcher because of everyone’s recommendations but would probably not like it very much. He’s the noble-type though and would be pretty easily convinced to read the Lord of the Rings books (including the Hobbit and Silmarillion) because of the nobility of the characters and story. Same reasoning goes for Donita K. Paul’s DragonSpell series. He’d also probably be into the writings of Henry David Thoreau, Ernest Hemingway, and Raymond Carver, not hugely into them necessarily but if he was super bored and he had access to their stuff he’d dig it haha. His favorite poem would also probably be Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H.. I don’t see him being too into podcasts, but he’d definitely like rock bands like Foreigner and AC/DC. He’s also definitely into movies more so than tv shows and would love movies like The Right Stuff, Top Gun, Braveheart, The Patriot, John Wick, most blockbusters classics really, and probably anything with Bruce Lee haha. He’d probably think anime/manga was for nerds until someone pointed out that Dragon Ball Z was, in fact, an anime then he’d realize they can be pretty cool hahaha. And with video games, I’d say he absolutely doesn’t have the patience for long form RPGs but can probably be convinced to play some FPSs with friends like Call of Duty and Halo lol. Basically, this was a long way of saying that Hal is probably more sporty, not in an obsessive fan of sports way, mind you, just that he participated in mostly sports growing up and even as an adult probably prefers hanging out playing baseball with kids (Adams’ GL run has an adorable scene of just that) rather than watching/reading/listening to anything so essentially he’s just not very media-obsessed; he’s a doer! He also probably wouldn’t participate in the fandoms of any of the media he does consume because he cares more about engaging with the media itself rather than about others’ thoughts and feelings on it haha.