#welsh literature

Text

See, I personally find this quest to find pagan/pre-Christian elements in Welsh/Irish literature quite unnerving - I don't know about anyone else.

There's something to be said about genuinely discovering pre-Christian elements in a narrative or story and that being where evidence and study has led you. But I see some people on this fruitless quest to find pagan elements in very Christian texts and sometimes it feels like if no pagan elements can be found, people start making stuff up out of whole cloth - and that can be very dangerous for already not-well known texts in minoritised languages!

There's already so much misinformation out there about Irish/Welsh texts and literature in general - so it hurts to see people carelessly adding to the misinformation either out of ignorance or lack of respect for the source material.

I promise you the source material being Christian doesn't ruin it - you can in fact, enjoy these myths without making them into something they're not!

#I feel like general ire towards (particularly) colonial Christianity has informed how people think of and view anything that is associated#with Christianity - and ire towards some of the ills committed in the name of Christianity is very valid actually#but what it isn't is approaching any text written in a Christian context and immediately disregarding it for having anything unique or#insightful to say. And in a Celtic languages context#this can be especially othering and almost fetishistic of an imagined pagan Ireland and Wales which was 'covered up' by Christianity#and that desire for people outside of Ireland and Wales to impose a kind of 'pagan faerie culture' onto the modern countries directly feeds#into false depictions of Ireland and Wales as 'lost in time' or as magical places full of latent pagan culture &c. which can be really#damaging in its own way against people who live in Wales or Ireland or who speak Welsh or Irish#this goes for other Celtic speaking nations too like Scotland Brittany Isle of Man and Cornwall#But Wales and Ireland tend to be the most focused on for this kind of treatment#luke's originals#Welsh#Wales#Cymblr#Irish#Ireland#welsh mythology#irish mythology#irish literature#welsh literature#Arthurian legends#arthurian literature

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

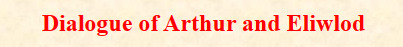

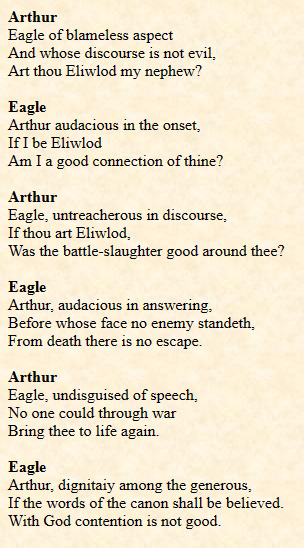

Arthur: If God's so big, why won't he fight me?

#the audacity of this man#arthur and the eagle#eliwlod son of madoc#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian legends#arthurian mythology#king arthur#celtic mythology#welsh literature

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

I let the stars inject me

with fire, silent as it is far,

but certain in its cauterising

of my despair. I am a slow

traveller, but there is more than time

to arrive.

R.S. Thomas, 'Night Sky' (1978)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes from Ronald Hutton's lecture "Finding Lost Gods in Wales" from Gresham College

A major problem for locating Welsh paganism in historical terms is that there really is very little source material to work with, certainly not much medieval literature seems to have survived in Wales, at least when compared to other countries such as Ireland and Iceland. It was thought that several Welsh stories and poems reflected the presence of an ancient Druidic religion and thereby some form of paganism, but this idea has since been rejected. It is now believed these stories and poems originated much later, possibly dating to around 500 years after "the triumph of Christianity". Only four manuscripts written in the 13th and 14th centuries might contain some possible relevance to paganism. Hutton tells us that these are The Black Book of Carmarthen, The White Book of Rhydderch, The Red Book of Hergest, and The Book of Taleisin (so-called). About 11 stories from the White Book and Red Book were compiled into what was called The Mabinogion in the 1840s. None of these are stories are certain to be older than the 12th century, although the oldest stories in the Four Branches of the Mabinogion may have been written as far back as 1093, and according to Hutton some of the stories of the Mabinogion were actually inspired by foreign literature, including not only French troubadour stories but also Egyptian, Arabic, and Indian stories that were brought to Europe.

Hutton notes that, unlike in medieval Irish and Scandinavian literature, the stories of the Mabinogion don't seem to feature any gods or goddesses or their worshippers (at least not explicitly anyway), despite being set in pre-Christian times. Many characters have superhuman abilities, but it's apparently not clear if these are meant to be understood as gods, or magicians, or just narrative superhumans. If there are pagan survivals in these stories, it may be the presence of an otherworld realm called Annwn, often equated with the underworld, and/or the presence of shapeshifting abilities (and on this point I believe Kadmus Herschel makes a convincing point in True to the Earth about this being reflective of a non-essentialist pagan worldview). Of course, Hutton believes that these are generalized themes and no longer linked to paganism in themselves, but of course I'd say there's room for skepticism here (I'm not exactly picturing a Christian Annwn here).

An important figure within the Four Branches of the Mabinogion is Rhiannon, a woman from Annwn who often believed to be a surviving Welsh goddess or survival of the Gallo-Roman goddess Epona. Her marrying two successive human princes has been interpreted as signifying Rhiannon as a goddess of sovereignty. Hutton argues that this is not certain because Rhiannon does not confer kingdoms to her husbands, there is no clear sign of a sovereignty goddess outside of Ireland or British horse goddesses in Iron Age archaeology or Romano-British inscriptions. Hutton argues that it's more likely that Rhiannon was a member of human royalty or nobility rather than a goddess. Of course, this is perhaps a zone of contestation. Hutton does not deny the possibility that Rhiannon was a goddess, but believes that the decisive evidence is lacking. For what it's worth, Rhiannon is a unique figure in the literature of the time, as a being from the otherworld who chooses live in the human world and willing to stay there even after every misfortune or crisis she encounters, responding to every problem with an indomitable and perhaps "stoical" willpower and courage.

The mystical poems, or the court poets from 900-1300, are also thought to contain some aspect of lost Welsh paganism. These were to be understood as a kind of artistic elite that delighted in prose that was sophisticated to the point of being almost beyond comprehension. They apparently believed that bards were semi-divine figures, permeated by a concept of divine inspiration referred to as "awen". They drew on many sources, including Irish, Greek, Roman, and even Christian literature, but also apparently the earlier Welsh bards. Seven mystical poems are credited to Taliesin, and these could be dated any time between 900 and 1250, though contemporary scholars typically favour 1150-1250 as the likely timeframe. Despite probably being written at a time when Wales was likely already Christianized, the poems are repeatedly referred to as sources of paganism and ancient wisdom by modern commentators.

The poem Preiddeu Annwn is one "classic" example. It is the story of an expedition into the realm of Annwn, which is undertaken to bring back a magical cauldron. The poem that we have seems to be explicitly Christian, but it is often believed that this is merely a Christian adaptation of an older pre-Christian text. But apparently no one really knows the real meaning of the Preiddeu Annwn, not least because no one can agree on what a third of the actual words in the poem mean. No one really knows if Taliesin was demonstrating a certain knowledge that only he possessed or what, if anything, he was referencing, so in a way we just don't "get" his poem.

Over the years the court bards ostensibly developed a new cast of mythological characters, or simply an enhanced an older cast of characters, to the point that they seem superhuman or even divine, yet just as medieval as King Arthur or Robin Hood. One example of this is Ceridwen, a sorceress who first appears in the Hanes Taliesin. Court poets apparently interpreted her as the brewer of the cauldrons of inspiration, and eventually the muse of the bards and giver of power and the laws of poetry. In 1809 she was called the "Great Goddess of Britain" by a clergyman named Edward Davies, which has been taken up by many since. Then there's Gwyn ap Nudd, who appears in 11th and 12th century texts as a warrior under the command of King Arthur. In 14th century poetry he seems to have been interpreted as a spirit of darkness, enchantment, and deception, and in the 1880s professor John Rhys identified him as a Celtic deity. Another major character is Arianhrod, who first appears in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion as a powerful enchantress whose curses were unbreakable. Over time it was also believed that she could cast rainbows around the court, the constellation Corona Borealis was dubbed "the Court of Arianrhod", and somehow since the 20th century she was identified as an astral goddess.

Then we get to the canon known as "Arthurian legends": that is, the stories of King Arthur. Hutton says that these tales originated as stories of Welsh heroes who fought the English, and these stories also contained what are thought to be residual pagan motifs. One example is the gift of Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, which is either based on memories of an older pre-Christian custom of throwing swords into lakes, the rediscovery of an older custom through finds, or even a persisting medieval custom of throwing a knight's weapons into a water. The Dolorous Blow which strikes the maimed king and turns his kingdom into a wasteland is thought to suggest a residual belief in the link between the health of a king and the health of a land, though the blow itself is inflicted by a Christian sacred object. The Holy Grail is often believed to derive from a pre-Christian sacred cauldron, but it was originally just a serving dish before becoming a Christian chalice.

And of course, there's Glastonbury, featuring as the Isle of Avalon, the refuge and possible burial site of Arthur. It has been thought since at least the 20th century that Glastonbury was a centre of paganism, but no remains have been found there which might suggest the presence of a pagan reigious site. And yet, in 2004, some prehistoric Neolithic post-holes were discovered near the Chalice Well garden in Glastonbury after the Chalice Well house started a kitchen extension. Although no deposits were found that suggest anything about the religious life of the area, the point stands that it was the first trace of anything Neolithic at Glastonbury. But there is perhaps always more to be found. As Hutton says, there are always new kitchen extensions, garden developments, street work, or any other renovation that might result in archaeological excavations, and we could find almost anything at any time. For my money, if there's hope anywhere, it's in that. Almost makes me want to get back into my childhood metal detecting hobby. It would certainly have a purpose: to rediscover anything from our pre-Christian past that could possibly be found.

From the Q&A we can incidentally note that many contemporary artefacts of Welsh national/cultural identity are very modern, they have nothing to do with some ancient past, but they weren't always to do with the romantic nationalism of Iolo Morganwg. The daffodil, for example, was probably first taken up as symbol of Wales in 1911, during the investiture of the then Prince of Wales. The leek, on the other hand, seems to have been symbolically associated with Wales since the Middle Ages, possibly as a reference to St David as his favorite dish, or possibly as a less then flattering reference to Welsh agriculture. The dragon, or rather Y Ddraig Goch (literally "the red dragon") as it is called here, dates back to a medieval narrative about a tyrannical king named Vortigern. He tries to build a castle but it repeatedly collapses, and according to the legend that's because two dragons, one red and the other white, are always fighting beneath the ground. The white dragon is supposed to represent the English and/or the Saxons, while the red dragon represents the Welsh and/or Celtic Britons. Although traditionally, at that time, Welsh princes took up the lion as their symbol much like English and other European royalty did, the Tudors established the red dragon as an official heraldic symbol of Wales to distinguish from English iconography, and that has been a mainstay of Welsh culture ever since. All-in-all, however, probably nothing to do with paganism here, unless the dragon has some older significance that we don't know about (and I'm inclined to be charitable here, considering that dragons in Christian symbolism usually represent Satan and/or evil).

There is the suggestion that Arianrhod is to be identified with Ariadne, the Cretan princess who became the lover and consort of the Greek god Dionysus. Both Ariadne and Arianrhod are associated with the Corona Borealis, which in Greek myth was a diadem given to Ariadne as a wedding present from Aphrodite. But that's about it. Any identification based solely on that would be a stretch.

There is the discussion of the legend of Bran, or Bran the Blessed, a king of Britain whose head was said to be buried in a part of London where the White Tower now stands. Hutton says it's possible that this may have reflected an ancient pre-Christian custom of burying parts of "special" people in "special" places to give them enduring magical/divine power, or alternatively that it references a Christian tradition of similarly venerating the relics of saints (itself possibly adapted from pre-Christian traditions in the Mediterranean, but that's another story; any input on that subject though would be much appreciated!). Hutton suggests that Bran's head being specifically buried beneath The White Tower is one of the best indications that the Four Branches of the Mabinogion as we know them were composed no earlier than the early 12th century, because the White Tower was built by William the Conqueror in 1080, and the Norman occupation in Wales as well as England at the time was part of the backdrop of the writing of the Four Branches. Hutton also suggests that stories concern parables from a distant, lost ancient time that were marshalled by Welsh poets who applied them as lessons for how to survive in the present, against the threat of Norman occupation. I should like to have answers on that front, because something about the reactivation of a distant past against the present order resonates very well with Claudio Kulesko's concept of Gothic Insurrection. It makes for interesting horizons, especially when applied to radical political dimensions relevant to things like the question of political identity in the context of the British union.

Relating to the legend of Wearyall Hill, the place in Glastonbury where Joseph of Arimathea supposedly planted the "holy thorn", there is the point made by the late historian Geoffrey Ashe (who, incidentally, died in Glastonbury) that none of the legends concerning Glastonbury have been or even can be disproved, which means that they all just might be correct. Hutton seems inclined to take what could be described as the "glass half full" side of that problematic, in that he thinks the great thing about myths and legends is that there also the possibility that there's something to them. I think that this presents possibilities for paganism, but in the sense that we are to look at it as an act of assemblage, or rather re-assemblage, and in a sense it works to the precise extent that we take it as medieval and contemporary mythology, without at the same time believing the lies that we tell ourselves through our romance and mythology.

Then there's the subject of the demonization of Gwyn ap Nudd in the Buchedd Collen, which incidentally counts as yet another Glastonbury legend. Hutton says that there is no doubt that Gwyn ap Nudd was demonized by Christians, but says that this was not specifically the work of the St. Collen myth. The legend of St. Collen was already fairly well-established in the Middle Ages, and the Welsh town of Llangollen takes its name from St. Collen. The legend goes that Collen was preaching in Glastonbury when Gwyn ap Nudd had taken over the Glastonbury Tor (Ynys Wydryn) and set up a mansion from which to tempt and seduce the inhabitants with vices and pleasures. Collen then goes to Gwyn ap Nudd's mansion and sprinkles holy water everywhere, causing it to explode and leave nothing but green mounds. Hutton suggests that by the 14th century Gwyn ap Nudd was already interpreted as a demon, but we don't really know how or why that happened. Here a horizon of assemblage emerges from the context of Christian demonization.

Gwyn ap Nudd, if taken as a Welsh or Brythonic deity, is interesting to consider as a demon invading Glastonbury and being exorcised by a Christian monk with holy water. There's an obvious question, albeit one that may have no answer: why does Gwyn appear as the subject of an exorcism myth in the context of a Christianized society? It seems plausible to consider Christians interpreted Gwyn ap Nudd as a demon by way of his already being the ruler of Annwn, an otherworld realm then recast as Hell. It may also be possible that Gwyn was a persistent reminder of an older pre-Christian polytheism, even if it's unlikely that he was actually worshipped by anyone living in the Middle Ages. Everything sort of hinges on the fact that the figure of Gwyn ap Nudd was pre-eminent enough in medieval culture, and enough of a thorn on the side of the Christian imaginary, to first of all be recast as an evil demon and then become the central antagonist of the legend of a Christian saint who exorcises him. That might allow Gwyn's presence in the legend to be interpreted as symbolic of the pre-Christian past, albeit through Christian eyes, and a figure who could represent its potential reactivation in Wales.

Lastly, there's the matter of apparent similarity between Welsh and Irish mythology, and the idea of a shared "Celtic origin" between them, in which we are again at a crossroads of possibility. That whole connection comes with a problem: there are definitely similarities between the Irish and Welsh characters at least in name, but these characters also to tend to share names more than they share almost anything else. The two explanations are either that these characters were deities that were worshipped in pre-Christian Wales as well as Ireland, or that Welsh authors were just well-acquainted with Irish folklore and literature and simply borrowed ideas from there. Hutton suggests that the first explanation may not be entirely wrong, or at least not completely invalidated, and leaves it up to the individual to decide between the two possibilities. It is very difficult to be certain is the first possibility holds up, and I have the suspicion it might not, at least not sufficiently. But it doesn't seem totally impossible, given the resonances between the mythical figures in Wales vs the pre-Christian gods of other lands. A relevant example would be Nudd, or Lludd Llaw Eraint, the mythical hero whose name was cognate with the Irish Nuada Airgetlam and apparently derived from the name of the ancient god Nodens. Not to mention Lleu Llaw Gyffes coming from the name of the Celtic god Lugus. That presents the slim possibility of connection, and perhaps assemblage by way of Irish myth.

If you want to see the full thing I'll link it below, here:

youtube

#wales#welsh paganism#britain#celtic polytheism#welsh literature#medieval literature#paganism#brythonic polytheism#glastonbury#arthurian legend#mabinogion#welsh mythology#british mythology#celtic mythology#gothic insurrection#Youtube

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

"But can't you realise that Evil in its essence is a lonely thing, a passion of the solitary, individual soul?"

Arthur Machen, The White People

#Arthur Machen#The White People#evil#evil quotes#loneliness#scary stories#Welsh literature#quotes#quotes blog#literature quotes#literature#literary quotes#book quotes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

'A Child's Christmas in Wales' - as illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman

#A Child's Christmas in Wales#Dylan Thomas#children's art#Trina Schart Hyman#Welsh literature#Christmas#nostalgia

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I bought Neon Roses as soon as it was out, and I was on a roll so I thought, why not read A Little Gay History of Wales for some added context around the events depicted, and then I realised that I was accidentally doing a Queer Welsh Readathon for Pride Month and decided to just go with it.

I've read the top row so far, and the bottom row is for the rest of the month! Not sure how many more I'll get through in June but recs very welcome if you've got 'em!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i just did my welsh literature exam and omfg words can't describe how relived i am to have finished it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You will only learn in a fight how much you've got to learn.

Richard Llewellyn, How Green Was My Valley

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musings on Myrddin

Chapter 1 of THE DAY WE ATE GRANDAD is available to listen to for free - Season 03 of my podcast is serialising the whole novel, week by week.

Listen on any podcast platform or in the embedded Spotify link.

Introducing a Bearded Old Bastard

Ricky has mentioned Myrddin and his distrust of Welsh poets before – towards the end of THE CROWS, where in his POV he is sulking about Eglantine Pritchard and the dangers of speaking Welsh, in case some ‘bearded old bastard’ shows up. In the hardback edition, there’s a short story called ‘Gerald’, in which Ricky meets Myrddin for the first time as a 10-year-old.

In THIRTEENTH, when Ricky is severely depressed and threatened by Wes’s presence in the house, he explicitly thinks of Myrddin by his Latinised name – Merlinus Sylvestris – and complains to himself that Myrddin was a better prophet than he is.

In THE DAY WE ATE GRANDAD, Myrddin makes an actual appearance. He isn’t real, exactly: the idea for Myrddin was workshopped with Robert Mitchelmore, whose poem, ‘οὐκ ἔπεφνεν ὄφιν: he did not slay the dragon’ (2010), appears as an epigraph to Part 2: Fall of the Titans.

Praise poems were meant to render their subject immortal, so that their names would never die so long as the poems were still spoken. Myrddin has, by now, so many stories and faces, that he is an immortal figure wherever his myth is known, and in that sense is no longer a man but an avatar of his own fame. That means there are baked-in limitations to his powers; he can do everything the stories about him say he can do, but according to this Myrddin, no story has been written where Myrddin saves the world from a Lovecraftian entity, so in that sense, he is powerless.

Myrddin is also not a heroic figure – he’s not a man of action, but a seer, a bard-prophet, and in the Welsh tales he was given his gift of prophecy by God to annoy Myrddin’s father, who was the Devil. Myrddin was meant to be the antichrist, but was baptised on the way out of his mother by a quick-thinking nun, which restored his free will. The infant Myrddin, now able to choose for himself, decided to devote his powers for good – mainly to aggravate his dad – and thus was given the spiritual gift of prophecy.

In my version of Myrddin, I’ve conflated his shape-shifting powers with those of Taliesin, another bard-prophet, and used parts of ‘The Battle of the Trees’ in his speeches. Myrddin is a Carmarthenshire lad, and looks a bit like an estate agent until you look more closely and see that his smart suit is just another skin he wears.

As to what Myrddin is doing there: he’s been interested in Ricky for a while, and this time he’s in our world (as opposed to the Otherworld) because one of his very distant descendants has asked for his assistance. All will be revealed in Chapter 3.

If you want to read the short story ‘Gerald’, where Myrddin and Ricky first meet, you can do so in the back of the hardback edition of THE CROWS.

I have 2 signed copies left in my Ko-Fi shop which are part of the book boxes that come with bespoke Pagham-on-Sea (sea spray and peppermint) and Fairwood House (lavender and earl grey) scented candles by Avalon Alchemy. If you tell me your favourite theme or chapter, I will do bespoke annotations for you in the margins of the hardback copy, as well as sign it.

I’ll be bringing out a collection of shorter Richard Porter fiction to go with the novella THE SUSSEX FRETSAW MASSACRE as a paperback release, which will be released as THE SUSSEX FRETSAW MASSACRE AND OTHER STORIES: AN ABRIDGED BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD EDWIN PORTER.

#welsh literature#medieval welsh#myrddin wyllt#welsh mythology#merlin#pagham on sea posts#stuff i think about#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dw i'n dweud celwydd. Mae hi'n ddigon llwyr i'm temtio

#love#romance#lies#hope#lovers#women#black#white#monochrome#tegwin huws author#dark art#quotes#sayings#welsh authors#welsh literature#tempt#moving on#going back#relationships#old relationships#poisonous relationships

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

From The Window/Y Fenestr by Dafydd ap Gwillym

#dafydd ap gwillym#melwas#gwenhwyfar#king arthur#welsh literature#welsh mythology#arthuriana#gogfran gawr

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.

— Dylan Thomas, 'Fern Hill'

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

When Did King Arthur Exist?

This is pretty much where I am on this.

youtube

The Origins of Excalibur! King Arthur's Legendary Sword

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

jokingly borrowed a book from my welsh school library and now i am emotionally INVESTED in twm and math oh my fucking god

#in case anyone can speak welsh the book i borrowed is prism by manon steffan ross#its actually really good#its about a two boys who run away from home when theyre supposed to be with their ableist father over half term#manom steffan ross#manon steffan ros#welsh literature#bookblr#welsh#manon steffan ross

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been a drop in a shower;

I have been a sword in the grasp of the hand

I have been a shield in battle.

I have been a string in a harp,

Disguised for nine years.

in water, in foam.

The Battle of the Trees | The Book of Taliesin VIII. | From The Four Ancient Books of Wales

#celtic literature#welsh literature#welsh poem#taliesin#ancient books of wales#wales#the battle of the trees#poem#poetry#quote#quotes#celtic#celts#past lives#past life#metamorphosis

2 notes

·

View notes