#the dangerous lover

Text

The Dangerous Lover premieres tomorrow and it already owns me, I MEAN:

Insane, scorching chemistry, blindfold foreplay...

Sexual asphyxiation...

But fret not, she wants to stab his carotid artery with her embroidery scissors, but it's him who lands the killing blow, ON THEIR WEDDING BED. That wasn't the bleeding they told her would happen.

So apparently, female lead foresaw the end of her family, with the whole family being slaughtered in the chess game for power. In order to prevent their demise, she wins over Su Yan Li, a fallen prince who has also experienced "rebirth" and strives to guide the villain to do good. However, he just might be the culprit behind the demise of her family!!!

I've been counting down hours until the premiere for the past week, because whoever is writing the script knows all my secret fantasies.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The figure of the vampire literalizes the undead state of the dangerous lover. The vampire’s near immortality links him to Cain, the Wandering Jew, and those ghastly characters in Byron who live eons of pain in a matter of days. In John Polidori’s introduction to his The Vampyre (1819), he points out that vampirism was often considered as a punishment after death for some dark crime committed when living, and the punishment encompassed not only the torment of a lonely and desolate immortality, but also the compulsion to visit the curse on those most loved by the man when alive.

Byron’s Giaour is just such a cursed soul: But first on earth, as Vampyre sent, Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent; Then ghastly haunt the native place, And suck the blood of all thy race; There from thy daughter, sister, wife, At midnight drain the stream of life; Yet loathe the banquet which perforce Must feed thy livid living corse. (755–62) The dangerous lover vampirizes those who love him, as with Manfred’s driving Astarte to take her own life; Glenarvon’s seduction of his victims, which leave them pale and lifeless; and the hero of the modern gothic romance and the erotic historical whose mysterious and terrifying eroticism fascinates the heroine into a helpless passivity.

The Victorian seduction narrative often likens the seducer to a kind of vampire like Dorian Gray, or a frenzied animal like Carker who might attack with fangs. The vampire, like the dangerous lover, steps out of timeless myth. In both myths eroticism might bring about death, transformation, or a transcendence of time and place. Both trace their roots to the Gothic demon who rises out of a supernatural realm of superior strength, agility, and the ability to change shape and form. Those who were already marginalized figures in society were thought to return as vampires after death, Laurence Rickels explains.

In medieval Eastern Europe alcoholics, thieves, excommunicated people, non-Christians (specifically Jews), those who died under a curse, and suicides were some of the excluded who might not stay dead. Dangerous lovers come down through myth with a similar constellation of vampiric symptoms; they are often alcoholics (Carton, Rhett Butler, and numerous erotic historical romance heroes), thieves (Conrad, the Corsair, and many other pirates); they are seen as unholy or cursed (Manfred, the Gaiour, Cain-like figures, Rochester, Heathcliff, and contemporary heroes linked with demonism, especially in gothic romances); they are effeminate or gay-coded (Rhett Butler, the dandy); and they desire death above all else (Manfred, Carton, Heathcliff, etc.).

Vampires after Byron, Tom Holland argues, descend from the Byronic hero, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), surely the most influential version of the vampire story, was largely based on Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), a story Holland notes was originally told by Byron, which his sometime doctor heard, recorded, and embellished. Contemporary film versions of vampirism, as well as such popular narratives as those of Anne Rice, represent an even more eroticized, sophisticated, celebrity vampire haunting the fashionable world with dandified grace, full of Byronic decadence, satiated ennui, melancholy, and pallid beauty.

An interesting and tenuous link can be traced between the vampire and the dandy, with Byronism as a background influence for both. Curiously, Lord Ruthven of The Vampyre appears to be something of a Regency dandy, and he has many of the characteristics that the Silver-Fork will later incorporate for its hero. The story opens in a familiar way: It happened that in the midst of the dissipations attendant upon a London winter, there appeared at the various parties of the leaders of the ton a nobleman, more remarkable for his singularities, than his rank. . . . His peculiarities caused him to be invited to every house; all wished to see him, and those who had been accustomed to violent excitement, and now felt the weight of ennui, were pleased at having something in their presence capable of engaging their attention. (265)

Lord Ruthven has “the reputation of a winning tongue,” and he loves to gamble, especially when it means he can ruin promising young men, Dorian Gray-like. He moves through the drawing rooms of London with a magnetic aloofness, “a man entirely absorbed in himself, who gave few other signs of his observation of external objects, than the tacit assent to their existence, implied by the avoidance of their contact” (267). He has, like so many dangerous lovers, “the possession of irresistible powers of seduction” (269). Lord Ruthven, like all vampires, is a dangerous lover of the melodramatic villainous type, and he eroticizes a sexual cannibalism, an act that involves violent, sadistic seduction.

Because the vampire must always be invited in, he represents the paradoxical fascination and repulsion of sex that is desirable because it is dangerous, because it might lead to pain, expulsion, and/or death. This desire to be ravished, to be “taken,” to be greedily consumed, has a role in so many of the demon lover narratives discussed here. When Jonathan Harker first meets the vampire of Stoker’s Dracula, his charm and personable qualities relax Harker after his frightful journey.

Although when Dracula is later encountered in England he is repeatedly described as a kind of crazed animal with a “hellish” look and flaming red eyes, here in the beginning his gently seductive and thoughtful manners draw Harker to him. Like the many melancholy heroes we have encountered he remarks, “I love the shade and the shadow, and would be alone with my thoughts when I may” (26). Dracula is another night brooder like Manfred or Eugene Aram who must do his work under cover of the darkness, when others are safe within their beds.

Cast out of the everyday activities of the living and the permanent stasis of the dead, Dracula haunts the night caught in a liminal state between death and life. Like a melancholy insomniac—Romeo, for instance—he is unable to live in the light of day. Dracula mourns the many who have died during his very long lifetime, both by his hand and by other means. Rickels explains that Dracula represents, like Heathcliff after Catherine’s death or Manfred, unmitigated mourning. Dracula apologizes for his melancholia in one of his few speeches: “[M]y heart, through the weary years of mourning over the dead, is not attuned to mirth” (26).

Dracula must die in order to open the possibility for a future that comes from Mina’s repurification after being “sullied” by Dracula and her engendering of a new narrative through her baby by Harker. That Mina can become a part of the heterosexual couple again and can escape the “outside” as represented by vampirism points to the future of many dangerous lover narratives. Thus we are brought full circle to the collection of dark, mysterious strangers in the twentieth century whose crimes do not need to be expiated by death, or by the punishments and inquietude that might happen after death, but instead their immanence comes on earth and in life, and their terrible self-exiled bitterness is absolved by love in the contemporary romance.”

- Deborah Lutz, “The Absurdity of the Sublime: The Regency Dandy and the Malevolent Seducer (1825–1897).” in The Dangerous Lover: Gothic Villains, Byronism, and the Nineteenth-Century Seduction Narrative

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your breasts are a battlefield

And my fingers are coming to edit.

#love quotes#dangerous romance#desire#intimacy#intimate#poetry#quotes#lovers#love#kiss#touch me#touch#neck kiss gif#neck kisses#kisses#kissing#huggies#hugging#romantic#romance#passion

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

The very foundations of love for the Byronic hero are based on failure and the forgetting of what is possible. The Byronic hero in his purity can, by definition, never be redeemed by becoming a couple, he is interminably thrown back upon black despair; he is unremittingly cast adrift into absence and dark night. [...] But finally the hero fails because this is the definition of the Byronic hero. He is the tormented melancholy failure who nears success and then fails and experiences the eternal loss, the repetition of the impossibility of bliss. He retains his status as the outcast, the dangerous lover whose subjectivity is as large and as impoverished as the world. For Jane Eyre and innumerable other romantic heroines (and heroes), to become an ideal lover, to turn this impoverished world into a plenitude, is to obtain an impossibility. To make the impossible possible is the erotic excitement of the dangerous lover romance.

(Lutz, Deborah. The Dangerous Lover: Gothic villains, Byronism and the nineteenth-century seduction narrative)

1 note

·

View note

Text

this fucking parallel gets me every time

#they are both on the ending tracks too#i’m gonna sob#mcr#my chemical fucking romance#my chemical romance#my chemical gerard#mychem#gerard way#three cheers for sweet revenge#i brought you my bullets you brought me your love#danger days#the black parade#demolition lovers#i never told you what i do for a living

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanna fuck you like an animal

#lovers#sexy content#desire#little tease#intimate#luxury#lust#passion#dangerous romance#touch#grab my hair#k!nky thoughts#h0rnyposting

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Omg I just had the most disgusting stepcest thought...

Stepdad!Toji has you on his lap spread eagle as he talks stepbro!Choso through giving you oral... Toji's hands wandering over your tits pointing out things in your pretty cunt etc while Choso is on his knees observing learning and eating you out.....

I know megumi makes more sense but I don't care lol...

✮ tags. . objectification, toji is a pervert, stepcest, he slaps your pussy. ꒱₊˚⊹ divider credits!

you sob. toji has been doing that for long minutes now and your plump clit is so sensitive that you don't know how much longer you can stand to keep being used as a demonstration of how to satisfy a woman before you reach orgasm without permission.

with the help of your arousal, he slides two thick fingers around your clit without actually touching it. he opens your pussy and spreads it apart so choso can watch closely how hard you're squeezing… choso leans forward, you see him lick his upper lip and mentally note everything his stepfather tells him.

"you have to wait for her body to ask to be used, okay? you have to be patient."

you tilt your neck down to look at choso sitting at toji's feet, his legs crossed, knees in opposite directions as he gazes intently at your open pussy.

"this is the most important place," toji murmurs behind your back, his silken, husky voice sending tingles through your body. "see how she reacts if I touch her here…" two fingers massage one of your breasts giving special care to the nipple, tugging at it as if hoping to draw milk from there, the other hand is in the middle of your legs moving to the tune of his words over your clit and between your wet folds. "you see how wet it is."

"I see that." muses Choso, almost drooling.

you moan again. "toji…" you call out to him, you try to cling to his arms and improve the position you're in but his arms hugging your legs below your knees, keeping you open for him with your thighs pushing up to your chest prevent you from doing so.

toji slaps your pussy.

"hold still." then he turns to choso. "do you want to try?"

"yeah, i'm ready. i want to taste it."

#asks#lovers ₊˚ᰔ#this with megumi is such a dangerous scenario#🤧#wr#cw stepcest#cw objectification#tw stepcest#cw dark content

753 notes

·

View notes

Text

#couple goals#relationship goals#romance#romantic#اقتباسات حب#عشق#حب#love#couple#passion#intimate#intimacy#dangerous romance#cute and dangerous#neck kiss gif#kisses#kiss#neck kisses#love quotes#lovers#touch#quotes#love poem#big and beautiful#big round butt#phat ass white girl#desire#casal#body art#meusposts

870 notes

·

View notes

Text

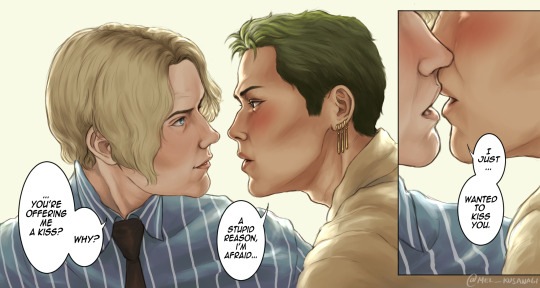

just one lil smooch

#my first one piece fanart and its gay as it should be#lowkey inspired by the sample dialogue of dangerously yours from tv girl's lovers rock#would draw mishanks next if i have more free time#zoro coming up with that rare w rizz#roronoa zoro#vinsmoke sanji#black leg sanji#zoro#sanji#zosan#zoro x sanji#one piece#one piece live action#my art

779 notes

·

View notes

Text

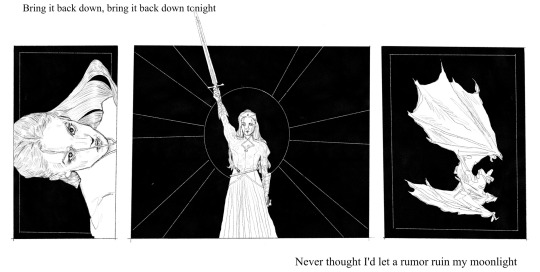

I'd end my days with you, in a hail of bullets……

#fanart#artists on tumblr#digital art#illustration#digital illustration#procreate#mcr#demolition lovers#mcr5#mcr gerard#mcr fanart#mcr art#mcr mikey#mcr memes#mcr danger days#my chemical romance#my chemical fucking romance#my chemical art#gerard way#frank ireo#my chem romance#my chem art#my chemical gender crisis#three cheers for sweet revenge#i brought you my bullets you brought me your love#ray toro#mikey way

958 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The Dangerous Lover' stills

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The pallid thinker, the intellectual, and the student: many Byronic heroes, most famously Manfred and such Romantic and Gothic Fausts as Melmoth and Victor Frankenstein (whom Mary Shelley modeled after Percy Bysshe, himself a studier of the occult), study late into the night. They study to gain Adam and Eve’s forbidden knowledge, the kind that will bring them closer to the gods, that will raise them up above a society for which they feel no fitness. They study at night to define their work hours differently than daytime industry.

Nocturnal research serves to move them outside of the social code; their knowledge does not seek to inform, to be disseminated, but rather they study to hoard, to collect and acquire what is generally not believed in, or is thought to be evil, perverse, against what is good and right. This “wrong” knowledge, a subterranean magic, dream knowledge, burrows into the depths of that which can never be fully known or owned. The accumulation of knowledge without discipline, without an end of action, of scholarly merit, is to fall, like Eve, from the grace of properly bounded thought which illuminates, elucidates.

In the rebellious stance of his fall the dangerous lover gathers a Luciferian darkness, casting him in the role of the demon lover, a midnight usurper who knows and is the only one to both read and approve the forbidden knowledge behind his truelove’s eyes and innocent face. Manfred studies his books on occult knowledge, reading all through the night, greeting the dawn with bleary eyes. The Byronic figure, often a chronic insomniac, desires not only forgetfulness and oblivion but also the rest of sleep, the mind’s calming from the cycle of tormenting remorse.

The beginning of Manfred shows the pain of impossible sleep. The lamp must be replenished, but even then It will not burn so long as I must watch: My slumbers—if I slumber—are not sleep, But a continuance of enduring thought, Which then I can resist not. . . . (1.1.1–5) Manfred’s needed sleep and highly strung wakefulness associate him with night journeys, done in lunar light. The stable temporality that flows with the daylight workday and with nighttime sleep is disrupted into a nonworking wakefulness. Interrupting the duty of hours, he is outside the workaday world, connected to the evil deeds that happen at night, the guilty pillow, the vampire, and the night-ghoul.

Blanchot writes of night as figural for an “outside”—outside the neat circle of the Hegelian dialectic. The circular return of Hegel’s thesis/antithesis/synthesis is broken by the secret night of no return, of the journeyer who does not come home. Byronic lucubration takes on a melancholy hue in Edward BulwerLytton’s Newgate novel, Eugene Aram (1831). Like the noctambulists Manfred, Faust, and Melmoth, Eugene estranges himself from others by withdrawing into his occult studies. Manfred, Faust, and Melmoth take this research too far—they come to know too much about the supernatural, the superhuman realm, thus becoming too great to dwell with common mortals.

Eugene’s fugitive retreat from the world comes from both his bloody secret—his role in a man’s murder—and his insatiable thirst for knowledge, itself a means of escaping his terrible mindscape. Manfred and his ilk become demonic and otherworldly while Eugene’s night studies take him merely into a melancholy darkness. Eugene’s guilt, his desire for self-annihilation, lead to the further desire to dissolve his self in knowledge, in his books, in staying up. He holds onto his terror of guilt with a fearful grasp, all the time flinging himself into constant study. “Eugene Aram was a man whose whole life seemed to have been one sacrifice to knowledge” (433).

From the beginning of the narrative, Eugene is already cursed with the pangs of remorse, the forsaken sense of an unresting torment. Eugene remarks, “It is a dark epoch in a man’s life when sleep forsakes him; when he tosses to and fro, and thought will not be silenced; when the drug and draught are the courters of stupefaction, not sleep; when the down pillow is a knotted log; when the eyelids close but with an effort, and there is a drag, and a weight, and a dizziness in the eyes at morn” (469). Eugene reads to attempt to make time move forward, to avoid the paralysis of his mind caught in his terrible past.

The night brings on the phantoms of a lost place in temporality, and even sleep teems with the feverish dreams of the guilty soul. Insomnia needs filling with the eyes moving over pages, the pen scratching the paper. Sidney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities practices self-exiled destruction, a continued search to remain estranged, cast out, and ruined through his feverish night research, fueled by alcohol and despair. Keeping awake while others sleep, Dickens seems to say, undercuts the possibility for Carton to participate in the “honorable ambition, self-denial, and perseverance” that the man of “good abilities and good emotions” (155–56) should uphold.

James Eli Adams dubs Carton a “dandy-dilettante” who is an affront to Carlylean earnestness. Carton with “waste forces within him and a desert all around him” is “incapable of his own help and his own happiness, sensible of the blight on him” (155–56). Like the Gothic villain whose blasted life comes from passionate failure, Carton lets his failure “eat him away” and, after a night full of research and reading the law, he “threw himself down in his clothes on a neglected bed, and its pillow was wet with wasted tears” (156). He often stays up nights like this, to help the ambitious Mr. Stryver with his cases.

But the benefit of this useful work doesn’t fall to Carton; in fact, he uses it as a means to further alienate himself from society by dissipation, which ruins his health. The intensity of his concentration when he lucubrates belies his carelessness in all other parts of his life (except for his desires to sacrifice himself for Lucie) and shows a kind of escape through loss of self-cares (an “anxious gravity” [152]), which is surprising for Carton whose central problems lie in self-absorption. “With knitted brows and intent face, so deep in his task that his eyes did not even follow the hand he stretched out for his glass” (154).

Heathcliff’s chronic wakefulness after Catherine’s death keeps his nerves highly strung, raking his body such that his nightwalking becomes his only work. Trying to sleep, Heathcliff describes his insomnia, which is caused by Catherine’s wandering ghost: “I closed my eyes, she was either outside the window, or sliding back the panels, or entering the room, or even resting her darling head on the same pillow as she did when a child. And I must open my lids to see. And so I opened them a hundred times a-night” (230). Nelly describes him as a person “going blind with loss of sleep” (262).

Brontë thus creates Heathcliff as a figure so self-absorbed (and “other”-absorbed, the “other” being Catherine who is, in some sense, still his self) that he transcends time and embodiment itself—still in love and haunting the moors after his death. Desire turns inward, feeding on fantasy, auto-obsession, pulling outward the deep interior of the self by wielding it as a weapon of world-decimation, through self-decimation. While the tortured quality of this starved state is clear, escape also opens as a possibility, pointing to an explanation as to why the outlawry of the Byronic figure is attractive to love narratives.

Being either so large that he might trace a line of escape out of the dreary world of commonplace concerns, or so slender that he might slip out under cover of the secret night, the Byronic figure traces a path of freedom with his homelessness. Literally starving oneself, going on a hunger strike might be the only way out of an intolerable existence. When Catherine dies, Heathcliff loses all appetite for things of life in this world, including nourishment of any kind.

Byron himself dieted off and on throughout his life, desiring to represent with his body the romantic figure, “pale and slender,” as Eisler writes in her popular biography, “haunted by secret sorrow and wasting loss” (120). Being consumed from within, the pallid wraith might become so miniscule he could almost disappear. Slipping away would free him from a dreary life into a fantasy of pure ideals, passion fulfilled.”

- Deborah Lutz, “Love as Homesickness: Longing for a Transcendental Home in Byron and the Brontës (1811–1847).” in The Dangerous Lover: Gothic Villains, Byronism, and the Nineteenth Century Seduction Narrative

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

أثْمَلتُها بِقبلاتي

#desire#intimacy#intimate#love quotes#poetry#kiss#quotes#love#dangerous romance#lovers#touch#neck kiss gif#neck kisses#kisses#kissing#romantic#romance#passion

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

The dangerous lover romance lends its voice to the buzz of existential questioning. Indeed, it is not too much to say that the forces at work in the attraction to the dangerous lover mirror basic ontological structures. [...] Heidegger describes being as a process of misunderstanding the authentic self. Caught up in an everyday world of all that appears closest and most familiar to us, we believe that our existence can be explained by what we know well. But ontologically, our most authentic selves lie in what is most mysterious and strange—what appears to be furthest from us. Confronted with authentic being, we feel a sense of terror in the face of the unknown. The dangerous lover narrative makes the same argument about ontology—that our “true” selves reside in what is most strange and enemy-like, in the dangerous other. Related closely to Heidegger’s proximity theory is our “being-toward-death”—that our lives can be understood only in relation to our end. The end of the romance transforms love into a possibility, into divine immediacy. Unfolding in the midst of stumbling error, unheard whispers, achingly misunderstood gestures, painful secrets bursting to be exposed, comes a day of grace. The romance story speaks always in relation to the full immanence of love which reaches its culmination at the end of the narrative.

The process of such a love has its uncanny qualities, and it is to the dangerous lover figure we must look in order to find a full embodiment of both Heidegger’s and Freud’s renderings of uncanniness. The romance

heroine finds her most authentic self at the heart of what seems at first most foreign and outside her way of being—an arrogant, hateful other. Romance moves always toward discovery and approaching the impenetrable: what is uncovered is authentic existence in the uncanny other; at the very heart of what appears to be not ours comes what we must fully own as ours.

(Lutz, Deborah. The Dangerous Lover: Gothic villains, Byronism, and the nineteenth-century seduction narrative)

1 note

·

View note

Text

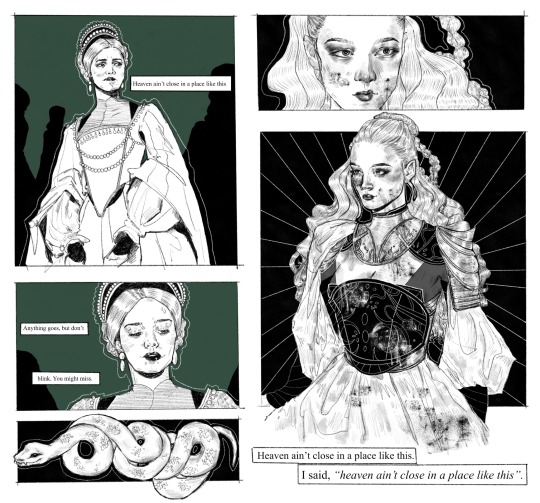

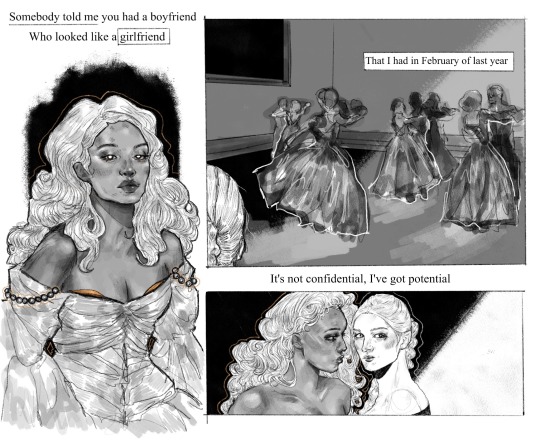

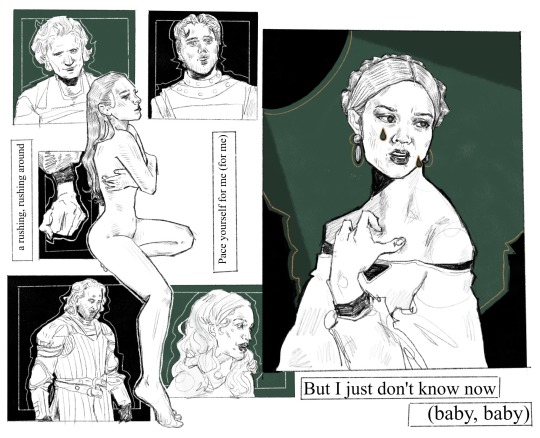

[ “SOMEBODY TOLD ME”]:

BREAKING MY BACK JUST TO KNOW YOUR NAME. SEVENTEEN TRACKS AND I’VE HAD IT WITH THIS GAME. A BREAKIN’ MY BACK JUST TO KNOW YOUR NAME—BUT HEAVEN AIN’T CLOSE IN A PLACE LIKE THIS.

— The Killers, Hot Fuss (2004)

Princess Rhaenyra’s insolence is wearing her stepmother’s patience thin. Queen Alicent is not ten years her senior, but even during her own sixteenth year, she cannot recall herself behaving so brazenly. She would never burst into courtly discussions in nothing but gilded armor and the underskirts of her riding leathers, awash in blood. (She would never be spotted in blood that was not her own, anyway. Alicent has never picked up a sword, not one that belonged to her.) Nevermind that Rhaenyra is attending to diplomatic affairs with bared teeth and scales, no—the crux of the matter is just that, her affairs. Rhaenyra is the Realm’s Delight, a beauty incomparable to any fair maiden, Alicent included. She indulges herself with appetite of a spoiled child, the confidence of man, and the pickings befitting only to her royal blood. Criston Cole. Daemon Targaryen. Harwin Strong. Laena Velaryon. She’s full of love, isn’t she? That selfish, foolish girl. What does Rhaenyra Targaryen know of love, of duty? She is a child in so many ways—she thinks killing makes her a man, thinks the throne is hers despite being a woman, thinks she can have her knight and her uncle and her protector and Laena Velaryon in one fail swoop. She’s wrong. She doesn’t know herself half as well as Alicent does. Alicent, who sees her for what she truly is, who wants to see all of her and more of her and none of her. Alicent has been stolen into the Keep by her own father—both of their fathers—but Rhaenyra is the key to this place, is the window to everything barred. Rhaenyra Targaryen has a dragon. Rhaenyra can fly.

That’s what Rhaenyra had promised her once, with her lips pulled back in a grin, exposing the white of her teeth like the violently radiant creature she was. “Perhaps when you grow tired of plotting against me, we shall ride on dragonback together,” she had said. The tease.

Alicent had yanked her into an empty corridor by the silk of her sleeve, ready to chastise her for her ill behavior. Conversing with the lords and ladies of the court at a feast was one thing, but chattering about her bloody encounters in battle over the pudding tureen were another. The lord at her elbow was going green. Alicent’s own face was likely red; her heart raced whenever Rhaenyra got like this. Alicent had never seen the battlefield—only seen battered men in dented armor and the slumps of corpses lined along dirt roads in the aftermath of war—but her own imagination terrified her like nothing else.

(Rhaenyra is better with a sword than half of the knights in Westeros, and more lovely than the lot. Her reign has not yet begun, but already the commoners flock to her—lured in by tales of her beauty and fine hair—and soldiers would follow her into battle. Alicent would not follow, but she would watch and bite her nails down to the quick.

She thinks of the figure Rhaenyra cuts in full armor, the heat in her gaze underneath the slots of her helmet. Alicent remembers the weight of her own hand in Rhaenyra’s—which was gloved—when the princess rode up to the spectators box and grasped it in her own, bringing Alicent’s knuckles to her lips. She thinks of Rhaenyra murdered in the sky, skewered with another man’s sword, plummeting to the ground, torn in half, streaking crimson across the clouds. Alicent would scream, or cry. She might laugh. She would throw herself from the window of her tower. Rhaenyra’s bloody exploits terrified Alicent for reasons she could not identify, and excited her for reasons she refused to.)

“I’d sooner be confined to the castle for the rest of my days than get on the back of that bloody lizard,” Alicent scoffed. Rhaenyra only tucked her hand over Alicent’s, where it was resting on her forearm. She flexed her fingers, moving to release her grip on the dark fabric, but Rhaenyra intertwined their fingers and held them fast.

“You’re confined already. You are already accustomed to such a thing. I know you. But—”

“But you forget yourself. You think you’re invulnerable, Rhaenyra. You don’t know who you are.” Alicent intends for it to be a sneer, but instead it comes out quietly, and too gentle for disdain. She can’t know. Rhaenyra is as trapped as she is, but they’re trapped together. They belong together. She belongs with Alicent.

“I am Rhaenyra Targaryen, Heir to the Iron Throne and all of Westeros. I am a dragonrider. I am—I am your daughter. In a way. Your sister, too. Your enemy. Your sword, your shield.”

“And what am I?” What else is left for me? Alicent wonders.

“My Queen. For now.” Rhaenyra cocks her head, and the gleam in her eyes burns like fire raining down. “When I am Queen, you will be my lady.”

#rhaenicent#rhaenyra targaryen#alicent hightower#house of the dragon#hotd#rhaenyra x alicent#my art#a book show fusion where alicent is the wicked resentful older stepmother first and foremost but even so she and rhaenyra have a connection#burdened by envy and fixation and reluctant affection. in this universe rhaenyra is given more liberties and trains as a knight would#is given a sword and flies into battle frequently and wears extravagant clothes which endears her to the small folk and makes her a hot#topic amongst royalty for her strangeness and charisma. alicent is expression not only of her freedom and expression#but of the company she keeps. rhaenyra has so many lovers and so many who are willing to follow her and it’s just not fair ok. alicent#and rhaenyra understand each other and know each others misery like no other. those other flings and beloved friends are going to get#her killed w how much they indulge her and encourage her dangerous habits and alicent may be in a cage but she won’t live in it alone. with#out her stepdaughter to torment and be tormented by (she represses the urges rhaenyra inspires bc she is devout to the faith) then there is#no meaning to suffering. god she’s in love w her. she hates her so much she wants to be her she wants to be with her she needs to touch her#she need rhaenyra to stop looking at other people bc it’s killing alicent by the day

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

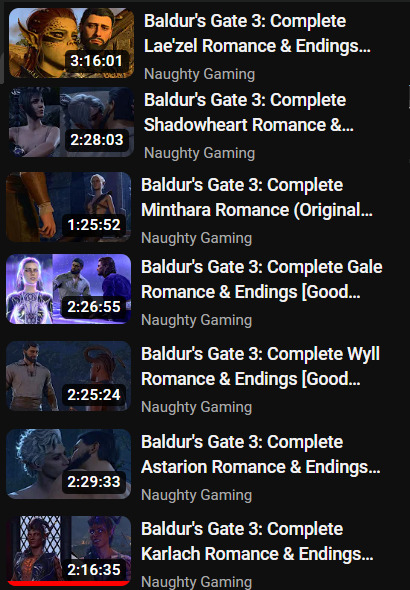

i’m not here to claim that wyll doesn’t deserve more extra content or that larian’s perspective of him isn’t rooted in racism in any way whatsoever. however, i sincerely believe that it’s always important to list the facts first before misinformation continues to spread which only results in more needless outrage.

these are all of wyll’s scenes that exist in the game as of now:

meeting karlach, mizora, and his transformation, the tiefling party kiss, the dance scene, mizora visiting camp, another scene where mizora visits camp, and the proposal scene. additionally, mizora and uldred can join camp, if he is alive.

in strict comparison - this is the exact amount of scenes the other origin characters have:

Astarion has 9 scenes, 6 of which can possibly be romantic.

Lae’zel has 7 non-standard dialogue scenes, 3 of which can possibly be romantic.

Shadowheart has 6 non-standard dialogue scenes, 3 of which can possibly be romantic.

Gale has 6 non-standard dialogue scenes, 3 of which can possibly be romantic.

Karlach has 4 non-standard dialogue scenes, 3 of which can possibly be romantic.

Wyll has 5 non-standard dialogue scenes, 2 of which can possibly be romantic.

source: [x]

wyll is lacking one scene compared to characters like shadowheart and gale. lae’zel merely has another non-standard dialogue scene, while astarion has double the amount of possible romance scenes and 9 scenes in total.

here is a video of wyll’s entire story: [x] at a duration of 2:25:24 in total it’s very similar in length to the romances of the other companions the same channel uploaded. (minthara & halsin excluded)

i have also seen many people refer to the datamined voicelines as proof of how much content wyll lacks. this, however, doesn’t tell us much since those compilations include battle grunts, noises, and other repeated lines. if you want to check them out for yourself, here is chubblot’s playlist on youtube: [x]

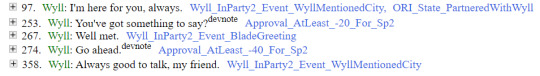

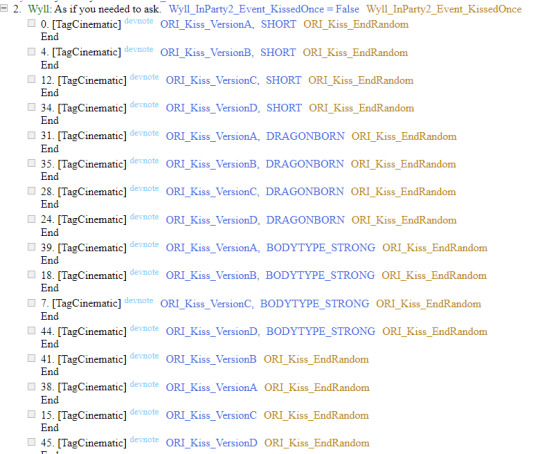

wyll’s romance/approval-specific greetings also exist, they are merely bugged. although i have heard that some people have been able to trigger them. bugged content is something that also affects other companions – in fact, most of gale’s romance scenes and some integral dialogue have been bugged for months now with no fixes anywhere in sight. if you don’t want to look for wyll’s greetings in the files, i took the liberty of doing it for you:

alas, his general reactivity after act i remains the same as with the others. aka: he's barely responsive to his surroundings nor to any key decisions the player makes.

wyll also isn’t the only character who isn’t able to make his own choice on whether he agrees to sell his soul for his father’s life or not. in fact, the only characters who can decide their own fate are shadowheart and lae’zel. the latter option only now being added with patch 6.

so what exactly did wyll get after patch 6? the same amount of kisses like everyone else: 4 in total. as well as some new idle animations and polished facial expressions. the kiss where he invites tav for a quick twirl had already been added in an earlier update (patch 5, 30th november 2023). which means it’s understandable that certain characters who didn’t receive any new animations or other content before were now added with patch 6 as well.

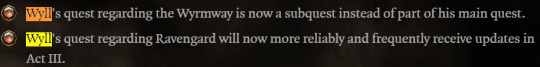

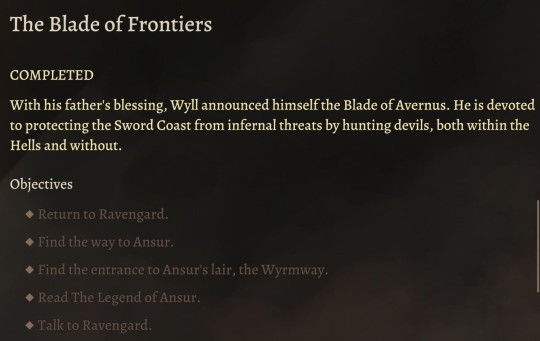

wyll’s quest regarding ansur also didn’t get removed from the game. this is plain false. larian merely changed the subcategory in the journal (which larian had done previously with astarion’s gur-related quest as well)

if you have a gripe with this particular decision: that is valid. the quest, however, is still the exact same as it was before.

i see fandom heading in this really dangerous direction where people fully believe they have the right to attack others for pointing out the existence of false information. i understand that people are upset about wyll having less content than characters like astarion and i am in no way here to claim that you should refrain from calling out racism where it’s due. however, this hostile behavior directed at anyone who dares to disagree with you is creating a really toxic environment within online spaces, where people hesitate to engage with the wyll side of the fandom at all (out of fear of immediately receiving the racist card for merely correcting inconsistencies in logic). and in case it needs to be said again: it is never justified to harass real people or send death threats to others under any circumstances, much less if it concerns a fictional character.

i, much like everyone, really want wyll to receive more love from fandom and larian alike. but it is no one’s place to police other players on how they should engage with this specific character in their own game. if others simply couldn’t connect to wyll as much as you personally have – for whatever reason – that is on them. it's them who are missing out. this shouldn’t hinder your enjoyment of this character in any way or discourage you from creating more fan content.

TL;DR: it’s completely valid to request more wyll content, but please don’t resort to “demands” or public pressure directed at the devs. this is only doing more harm in the long run (to wyll’s, as well as his fanbase's reputation within the rest of the fandom instead of actually accomplishing much). don’t spread misinformation that he’s the only one of the companions who is continuously receiving the short end of the stick in terms of content, general reactivity, and bug fixes. if anything, the biggest difference is between him and astarion (again, much like every other companion).

🙏 please be respectful to each other 🙏

update, 19th february:

a user suggested providing an alternative to petitions on this post and linking directly to larian’s official feedback form, which you can find here: [x]

you’ll be able to add screenshots of the specific issue you’re reporting. keep in mind that you need to name your exact game version if you plan to send in a report. i’ve had larian ask me to send them the specific game files in the past, so it’s best to keep them on hand in advance.

larian also has a faq page on how to submit a general bug report [x]

here is an example of what to write:

(I’d like to address the disparity in content between Wyll and the other origin companions.) As of now, Wyll is lacking an entire scene compared to the rest of the characters, and his romance-specific greetings remain bugged as well. The lack of equal scenes makes Wyll’s story feel lackluster at times and undermines the pacing of his romance and overall character arc. It is very disheartening for POC players specifically to see racial biases reflected in his treatment and that Wyll didn’t receive the same amount of resources. Considering his narrative role as the Grand Duke's son he also deserves to be in the spotlight. When can we expect any fixes or additional content?

#bg3#baldurs gate 3#wyll ravengard#informational post#racism mention#fandom discourse#it speaks#i understand that i’m treading into dangerous territory here#but please keep it civil#meanwhile minthara lovers sitting in the corner with barely any scraps to go by: this is fine#updated

305 notes

·

View notes