#student historians

Text

people who don't study history will simply never understand the joy of reading historian beef. there's nothing like it

#when they're reviewing each other's work and they're just SHITTING ON IT????? wonderful#when you can tell the historian HATES whichever historical figure(s) they're writing about? incredible#one thing we must remember is that historians are just academic gossipers xx#what is JSTOR for if not to read the DRAMA#reading an absolutely SCATCHING rebuttal of an article on New England migration and honestly??? having a wonderful time#sometimes the history student just jumps out#history

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yandere Student Council

You just needed to get your schedule officialized. Having gained special permissions to take a desired course you needed the student council’s collective stamps of approval to proceed. Normally all you would need to do was slip in the necessary documents. But something seems to keep happening to yours and it just works better for you to do it in person. Thus begins you’re journey of getting the obsessed student council’s approval.

The first one you go to is the one with the easiest access –the Secretary. Gill Hunter has an absolute poker face when his boyfriend isn’t around. So you’re pleasantly surprised when he’s actually willing to hear you out. Keeping his amber eyes on you he listens to your plea for his stamp, seemingly not reacting at all he promises to help you—for a price. You have to step in for him and his boyfriend from time to time. He says it's just a week as he demands you shadow him for the day. Calling to you in his monotone voice to join him in the student council lounge. Don’t bother bringing up you’re friends or your desire to eat your lunch alone. Even as the week comes to an end and you get your stamp he has you working closely with both him and his boyfriend very closely as an honorary assistant.

“Most if not all schedules go through me, you don’t want your schedule being messed up again. Do you?”

The next one is Gill’s beloved–the Historian. June Frimroar is a different kind of person you need to get a stamp from. Where Gill strings you along with his stone-cold face and hardly hidden intentions, June will do the exact opposite. With a smile that flirts with scheming and altruism, he’ll ask for the most innocent kind of help. Only to somehow become something far more intimate and demanding of you in the first place. How else would simply taking notes during student council meetings lead to you smushed in a locker with the historian and his boyfriend? Or how you’ll be forced to help undress June whose hands inexplicably might be sprained? He’s an enigma to loosely associate with trouble, easily put off by how kind he is to you and your friends as you start spending more time with him and the rest of the student council. Certainly, those rumors of him crippling classmates for fun are far from true, right?

“Don’t you trust me, (Y/n)? Just listen to me and I’m sure everything will work out…even if that blackmail situation with your friend is completely separate.”

Like clockwork, you fall into being the student council’s lackey suddenly trusted with helping the seemingly overwhelmed Treasurer. Min Su is an odd fellow who’s been dignified a living legend with his accounting possibilities; rumored to casually be hired by the government a couple of times. So it's odd that he suddenly must have you spending your club hours documenting receipts. He’s so apologetic and jumpy that you don’t feel right questioning him. So it's normal that he has a fierce blush on his face as you take the records from his hand. Or the little noises of excitement pleasure he seems to have when you lean over him to admire his speed as he’s calculating the books. He’s likely to forget that you needed to get his stamp until you off-handedly mention how you’re going to miss him when you get that stamp.

“Oh, you wanted that? I-I’m happy to give it to you, n-no problem! But you’ll still visit me right?”

At this point, your presence is much more normalized in the student council quarters, and naturally, the Sergeant of Arms or more well known as the student council’s hype man is happy to welcome you. Popular beyond belief Roman Ferris arguably has the largest fan and friend base in the entire council. Knowing everything about everyone he already knows what you’re asking for and he’s cheekily telling you he’s already prepared how you’re going to get it. If you thought Gill was forward then you’d be mistaken Roman straight-up demands every weekend that you come with him on a date. Movies, restaurants, ice cream, trips to the park, he’s doing it all with you. Demanding you dress up for these ‘definitely not dates’, hold his hand while you walk, and smile at him only him when you pose for the camera. It's odd how he knows your every like and dislike, always ordering for you and smiling ominously when you ask. But he’s definitely not giving you this stamp if you suddenly stop coming to his dates hangouts, even if he promised he would. It’d be bad if the whole student body considered you a harlot for playing with the golden boy’s feelings. So just smile while you eat your favorites and keep your mouth sealed about your suspicions.

“Don’t worry about it babe, I already know just how you like it! Don’t worry how I know~ You’re so cute when you're well-fed!”

Practically cemented to your unwritten obligation the Vice President is well aware of what you’re after. Spencer Lyle will wait until the end of the day mindlessly stamping your document as he scrambles through his hefty pile of paperwork. Bags under his eyes and his lids dropping dangerously you figure you’ll help him, already familiar with the kind of work he was doing anyway. He thanks you when you eventually wake him up and from then on something sinister a friendship is born. Suddenly he’s coming up to you in your classes, during lunches keeping you talking casually as he leads you to the student council room. You were going there anyway, right? He’s just the perfect friend for you. Great at warding off bullying fans or teachers that get a little too snippy, he becomes your go-to friend. Not too popular but well-respected feared by the student body; totally perfect for relying on him to be relatable. Completely complacent with letting him into your life and it feels so normal now that he rings your dorm bell for an early morning. You know him so well so it's natural he does the same.

“Hey, you ready to go cupcake? Bags under my eyes? Yeah, I was up all night protecting you doing council stuff, you know how I work.”

Last but certainly not least the Student Council President: Lucoa Grander the college’s prodigy cryptid. Known to be a living genius and prominent underground business personality it seems only natural that he gets such a powerful, prestigious position. He is such a celebrity you go to Spencer to deliver your schedule confirmation only to receive a disappointing answer. Apparently, the president’s only willing to stamp yours personally, and thus your witchhunt for the illusive president begins. Searching high and low, stringing on his fan base’s own timeline and the other council members’ accounts you try to find him. But after a while, you give up fully prepared to abandon your desired course to have the blue-haired pierced-up president mysteriously showing up. He greets you so casually, sitting next to you as he asks mundane questions. When you finally ask for his stamp he gives it to you…on a major condition.

“We’ve been looking to widen our ranks and I’ve we’ve been keeping a close eye on you. And we’re thinking of making you an honorary member–it's a new position to diversify our team. You’ll get your stamp this way and we get you our beloved a new member that’s fair enough isn’t it?”

#yandere x reader#yandere x you#lovelyyandereaddictionpoint#yanderexrea#yandere#yanderes#yandere harem#yandere ocs#yandere oc x you#yandere x darling#male yandere x reader#yandere drabble#yandere ocs x reader#yandere oc x reader#yandere oc#yandere student council#yandere student council president#yandere student council vice president#yandere secretary#yandere historian#yandere sergeant of arms

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm working on a full drawing and needed to figure out gregori's outfit, and that made me want to draw lisa next to her, and that made me want to draw everyone else...

so here's all my (current) dragons who are part of some magic college or whatever in the sunbeam ruins

#eye guy art#drawings#ocs#flight rising#frfanart#in order it's gregori - lisa - hermetica - gilding - verbena#gregori and lisa are students or smth. they're besties <3#hermetica is a wizard who's mentoring lisa#gilding is a librarian and art historian#(<- these two middle aged men are in love)#and verbena is the head of the whole thing

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

It would be sooo funny if I applied to the University of Warsaw to do a PhD po polsku with Anna Nasiłowska but since Anna Pilch died and I'm not focusing on film like the Małgorzatas she is in many ways literally the only person qualified to supervise my Fake Thesis on Stefania & assimilation

#The problem when fewer than five living people really work on your research subject#Diana W. is great but I'm not an art historian I am a regular historian#Jakub O. is also a grad student#We are so few. The Stefania Stans (academic)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1594 Gwen Ferch Ellis was the first person to be executed for witchcraft in Wales. Like most accused female witches, Gwen was previously known to have carried out healing of sick humans and animals in the town of Landyrnog.

Gwen was accused of having a charm written backward; something that was assumed to be a form of bewitching. Gwen was taken to Flint goal to await trial.

During her trial, Gwen was accused of having murdered a man called Lewis ap John through witchcraft and was subsequently found guilty and executed as a witch.

Unlike in England, there were very few witch trials in Wales, with only five executions having taken place. It has been estimated that 500 executions of accused witches had taken place in England during the Early Modern Period.

#witchcraft#witch#witch trials#witch craze#welsh history#medieval wales#medieval history#historyblr#historian#history student#history lover#history buff#welsh witchcraft#welsh witch#occult history#early modern history#early modern wales#tudor wales#tudor britain

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

year 5 and I'm still mocked for being an art student attending art hist lessons

#it's always like this at the beginning of the semester and at the end it's gonna be all like#''wowwww congrats on doing so wellllll i didnt think you were from the academyyyyyyy wowwwwww''#this professor even taught me 3 years ago and gave me the top grade at this point it's willful ignorance#eernatalk#ok out of context this makes no sense. art students and art historians are in separate schools and i have to go to the art historian school#for the type of art hist classes needed for my major. it's at that school that people look down on artists

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

im really having a moment right now.

i dropped out of school and college and i really had no hope, i quit my job and i thought i was a failure but i’m starting uni this year after 3 or so years of pure stress 😭 i might cry.

#nobody in my family has a degree and i felt so much pressure but now i can just do it on my own terms#alèssi says things#having a crisis#cmon student loans let’s get sickening!!!#im going to be a historian 🤓☝️i’m making it happen

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

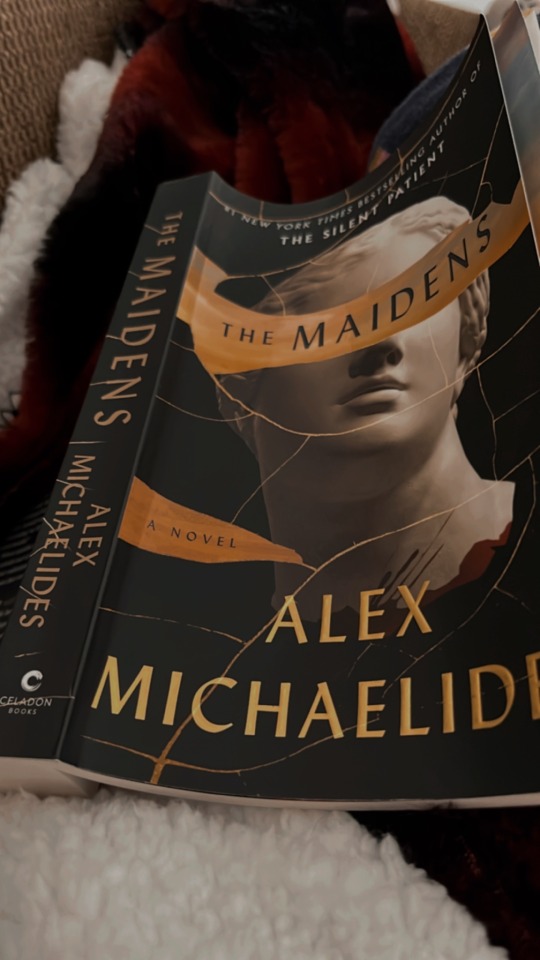

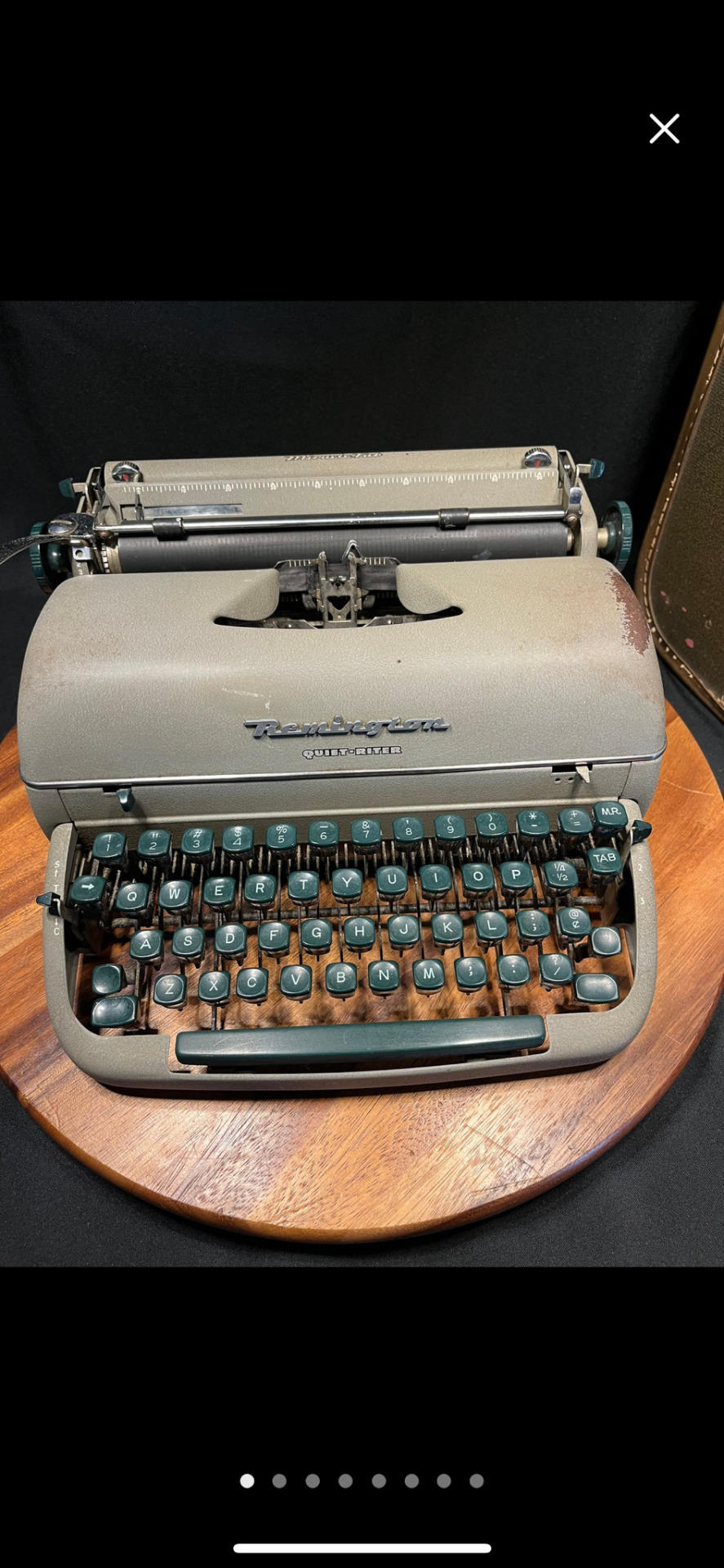

I took a day for myself. I arranged for a day off work and went to the bookstore and picked up some goodies to read and write. I had a pumpkin chai tea latte with oat milk and a pumpkin stack (so much sugar!). I am going to read and watch films today and try not to do anything academic. Tomorrow I plan to go to the salon to change up my hair and grab some new makeup. I may have ordered a Remington Quiet Riter typewriter after watching one of R. C. Waldun’s videos on YouTube. Self-care is so crucial during your academic studies. It’s so easy to become consumed in assignments, social life, work, and still not make time for yourself. I am grateful I took today off to spoil myself and to choose rest. It’s helped me feel alive again.

How are you taking care of yourself today?

#study#university#studying#college#collegelife#student#studyblr#books#universitylife#bookstagram#studentlife#school#studytime#english major#history major#historian#grad studyblr#grad student#graduate school

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trunk or Treat with The Yandere Student Council Pt. I

Based Off the OCs in this Post

“Alright everyone let’s start talking about ideas!”

“Uhm do you mean ideas for what to do with Halloween coming?”

“Oh no darling, we always do a Trunk or Treat kind of thing.”

“We are talking about our costumes.”

As bizarre as it sounds the college’s students look forward to the costumes of the student council

Allowed to enjoy whatever festivity that comes with their choice

For reference they share that last year they had a ‘kiss–in–the–coffin’ booth for their shared vampire costumes

“J-j-just so you know the kisses were on the cheek only!”

“I didn’t ask but okay.”

It set the precedent for this year to be just amazing if not better

“Since we have you now (Y/n) we should have something special that welcomes you in!”

“I-i-i-i think that’s a great idea.”

“I’m all for it too!”

Despite your protests, in fear of being singled out by their fans your haters they forge on

“They won’t be bothering you. Not on my watch.”

“You say that but–”

“Seriously (Y/n) believe us! We’ll make sure there won’t be any problems.”

“And if there are we will kill them.”

“What?!”

“Joking. Joking.”

They’re not

Anyway it was decided on that the council will be Ghostly Royalty

Which makes costumes really easy or so you thought

According to Min, quite a large part of the budget went into your costumes

“Pick your jaw up (Y/n)! This is the best part! You don’t think we get this big of a budget without showing off, do you?”

“Still…it feels a bit overkill…especially when I don’t have a fan base at all.”

“Ohhh that’s what you think–ow!”

“Roman, always such an optimistic chatterbox. Always saying things that are not true.”

Lucoa takes the role of the king naturally

Spencer is forcefully given the role of the queen

Min takes the role of the dungeon master, despite his meek character

Roman takes the role of an advisor

Gil as a duke

June as a duchess

“Wait so what am I?”

“Our dragon.”

“What?!”

“We wanted to put a spin on the old system!”

“But that isn’t really accurate…nor does it really fit the ghost royalty theme.”

“.....”

“....”

“So? We’re doing fantasy ghosts then.”

In your opinion, it's just an excuse to make your costume as ridiculous as they please

“This is an early draft of your costume.”

“What!? Wait where are the actual clothes? I’m just seeing gold necklaces and bangles.”

“...That was the idea.”

“I’m not wearing that if there aren’t actual clothes underneath there.”

“...But it will ruin the integrity of the design and disrupt the choreography and–”

“Then hide it under the gold! I’m not going to be half-naked for the entire school.”

“...I will consult the President.”

You owed him a favor after that

Saying you agreed to this as an honorary member

But when you’re not having to fight Gill on your costume designs

You are helping the others

“June…this is just a dress.”

“Right, it’s a perfect occasion to wear it. And don’t my hips feel and look great.”

Adjusting the golden belt meant to hang off his waist you try to ignore how his poses requires that he touch you in some way shape or form

“Well yeah but don’t you feel like your fans would want you in something else?”

“Oh baby! You don’t have to worry, they love this sort of thing.”

And helping with their research

“Roman I know you never seem to run out of ideas to hang out but why a medieval diner?”

“It's for research! By the way, how do you like the food? I made sure the critiques were as positive as they could get.”

“Roman.”

“Yes?”

“Why did that waitress, compliment our relationship?”

“OMG they brought another plate of bread and for free? So cool.”

“Roman!”

Or helping organize their booths

“So Spencer what are you going for?”

“A kind of dunk tank except it drops on me.”

“Oh okay….this says that you’re not actually using water but…oil?”

“Yeah Lucoa suggested I show off my scars and muscles.”

“Wait you have those?”

“Hahaha very funny but seriously give me your opinion.”

“Oh wow….yeah, I think they’ll like it…no they’ll love it.”

“Oh really? Well, thanks!”

As if he didn’t already know

But eventually as the date comes closer it comes time to focus on your booth

But it seems that as an honorary member you don’t get to have much control over your own booth

Or any decision involving your event

“Hey Min what are you building over there?”

“Oh this is the art for your exhibit. Lucoa put me in charge of matching the gold from your costume to the setting around there.”

“Aw thanks can I help?”

“N-n-no!”

“Oh.”

“S-s-s-sorry the President gave us explicit instructions not to include you in the making of it. I’m r-r-r-r-really so sorry!”

“It’s fine Min, don’t worry about it.”

It’s just so apparent how little you would be included in your own activity no one really bothered to hide that fact from you

“Hey Gill this meeting on your calendar, I don’t remember getting your usual reminder for it.”

“That is because you are not invited to it.”

“Don’t be sad (Y/n)~Afterwards we can just come visit you after.”

“No no that’s okay I’ll just take the day off then. Catch up on homework.”

“Aw~ Don’t be like that we’ll come over to your house after.”

“No I’m not sad. I’m going to be happily doing my homework alone!”

“Putting that on our private calendar: Going to (Y/n)’s house an hour after the meeting.”

At the end of the day you’re just as surprised when the event begins and they shove you in the room under the stage with nothing but a warning not to move from the chair you’re in:

Part 2

#yandere x reader#yandere x you#lovelyyandereaddictionpoint#yanderexrea#yandere harem#yandere#yanderes#yandere oc x you#yandere oc#yanderes x reader#yandere ocs x reader#yandere ocs#yandere original character#yandere student council president#yandere student council#yandere secretary#yandere historian#yandere student council vice president#yandere student council ocs#yandere sergeant of arms

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historians In Everyday Life! Or HIEL!

Two colleague students studying for a Bachelor of Arts in History stumble across a strange old well in their hang-out place. Both of them are unsure how or when it appeared when one looked inside the well. The water inside was fresh and clean water.

When one of them gently tossed a pebble inside the well, they wished to talk to a person from 1953-1957. A spiritual lady appeared in their presence after being expected there, and she was indeed a person from 1953-1957. The two historians were speechless and amazed by what this well granted them, so from now on, they encountered several people from the past to talk to them and wonder what it was like back then.

Of course, these two historians' life isn't about talking to spiritual people but also about encountering other troubles. Let's say they met lovely and caring people in high school; friendly of them to see each other again after a long time. Of course, they also meet dreadful and irritating people; how unfortunate that those people support awful politics that aren't even doing good in the country.

Follow along in these historians' life as they encounter different situations in their everyday life. Learning history can be exciting and spine-chilling, but as long as you know the history of your own country, what happened in ww2, and so on, you know that other people will spread misinformation you know not to believe in those lies. Have fun sticking into this fun adventure with these historian's life.

#cosmistuff#Historians In Everyday Life!#Hiel#fantasy#slice of life#my original characters#original characters#history#philippines#filipino#ocs#my ocs#forgot to explain what's hiel#you get to see the silly college students#and ghost too#but their pretty chill so !!#everything here is fictional#except for any of the history facts and stuff that I'll mention occasionally#fiction#fictional characters#fictional story#i wanna talk to people in the past so badly too#lgbtq#lgbtqia#main cast is heavily lgbtq#be scared homophobe people#screw dds people ew

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acadamia was a mistake I think

#I was invited to lunch with my favorite professors old professor#Because he's doing a guest lecture at our university#And the anxiety brain worms are telling me I embarrassed myself in front of him at lunch#And I'm about to go to his actual lecture and I'm Nervous#He's a apparently a very well known ancient Greece historian#And I was very afraid of embarrassing myself because that's one of my favorite fields#Anyway. Anxiety is fake and I'm sure he does not care about a first semester grad student#Fumbling their words because they're socially awkward and a little too working class at the academic lunch#The lecture is about Greek religion and I WILL enjoy myself because ancient religion is my favorite thing in the entire world

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the love of all that is holy, please stop saying that Robert was a Communist. You are completely misunderstanding who he was as a person if you honestly believe that that was the only political ideology that he subscribed to. He believed in aspects of Communism, and he realized after two of his friends returned from Russia that true Communism could never be achieved. He believed in giving to the people who were going to get shit done, but he himself was a New Deal Democrat (aka a Socialist). I am so heartbroken that people to this day continue to call the man a Communist when he made it clear to Chevalier that he had never been one. This was long after his security clearance was removed that he said this after Chevalier wrote a shit book that was so clearly based off of Robert. No doubt to sell more copies, but thankfully most of the scientific community and historians knew that that was bullshit.

#god why are people so blind I swear people on this website see what they want to#Oppenheimer#Julius Robert Oppenheimer#history#He also was friends with everyone even Republicans#Lawrence was a hardcore Republican and they were fairly close#as was the man who taught him Sanskrit#He understood that while Communism has wonderful aspects to it that it can never and will never work#y’all need to read some primary fucking sources 😭#the saddest part is that the propaganda against him won#he cared deeply for the causes that communists believed in but not necessarily the entirety of Marxist ideology#so tired of bad takes#history is never black and white#stop projecting your beliefs onto history and get the facts straight#it’s cool if you want to believe in whatever but Robert is not you and you are not him#ranting ignore me I’m just pissed#yes I know that he tried to make his stance more ambiguous in his book but it was clear that he was straight up calling Robert a Communist#even before the Red Scare Robert still hadn’t truly been a member of the party but he did support his students who were members and staff#as a historian I cannot tell you how much it upsets me how people twist the truth

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrote a vintage car ad for an art project today but i was in a rush so i decided to just fuck around write down the first shit that came to mind. I don't know how i got here tbh. will update with my final grade once i get it

#car#vintage cars#1920s#art project#art student#art stuff#art school#art school things#i wonder how ralph is doing#historians will say they were close friends#illustration#illustrator#illustration student#art college#vintage#vintage advertising#vintage ads#art on tumblr#artists on tumblr#artist#artists#small artist#illustrators on tumblr#gay probably#vintage car ad#1920s cars#1920s car

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not just trauma. I'm also academics.

Zach Reynolds

Dr. Nancy Chase

December 2, 2010

Engl 3040

Analyzing the Tragedy of Septimus Smith

Captured in Mrs. Dalloway there is a reflection of the socioeconomic structure of early 20th century England, as well as the patriarchal class and imperial ideologies that marked this era in British history. The burden a civilization informed by these ideologies puts on its constituents, both its lower and upper class members included, is of focal importance to the novel, because despite its celebrated achievements in psychology and temporal analysis, “it nevertheless incarnates a critique of Empire and the war, taking the state as the embodiment of patriarchal power, and the upholder of what even Richard Dalloway calls ‘our detestable social system’” (Tambling 58; Woolf 116). Central to this critique is the tragedy of the character Septimus Smith, a literary-minded veteran who survives the war only to succumb to the more subtle violence of imperial social ‘justice.’

The portrayal of Septimus’ ambitions, military service, and mental collapse provokes a sharp Marxist criticism of the classist and imperialistic tendencies of early 20th century England, and creates through its criticism an interpretation of this moment in history that is defined by the opposite discourses of Septimus and the aristocracy that drives him to suicide.

When Septimus is first introduced to the reader, he is described as “pale-faced, beak-nosed . . . with hazel eyes which had that look of apprehension in them which makes complete strangers apprehensive too” (Woolf 14). One cannot help but to label him a lunatic immediately following the passage detailing his hallucination of a sparrow chirping his name and singing in Greek, or his vision of “the dead . . . assembling,” with an unknown man, “Evans . . . behind the railings!” (24-25). In the passage that falls between pages 84 and 86, however, a brief biography is given of Septimus Smith, which informs the reader of his disposition before the war. Here, Septimus is made un-extraordinary as one of “millions of young men called Smith” (84), and characterized in his youth as a typical middle class idealist. He is “on the whole, a border case, neither one thing nor the other, might end with a house at Purley and a motor car, or continue renting apartments in back streets all his life . . .” (84). His experiences are summed up satirically in botanical terms, with Woolf imagining that were a gardener to voyeuristically look on Septimus at this early phase in his life, he would say that the young man, consumed with “such a fire as burns only once in a lifetime” with his love for “Miss Isabel Pole, lecturing . . . upon Shakespeare,” and his passion for “Antony and Cleopatra . . . Shakespeare, Darwin, The History of Civilization, and Bernard Shaw”(85) was flowering into a man ardently moved by his reverence for English society and the legacy of art of which his love Miss Pole was the beautiful embodiment.

So, when it came to war, it’s no surprise that “Septimus was one of the first to volunteer. He went to France to save an England which consisted almost entirely of Shakespeare’s plays and Miss Isabel Pole in a green dress walking in a square” (86). The war changes Septimus though. He faces the traumatizing experience of watching his friend die in front of him, yet he stoically does not mourn his friend, Evans, and is rewarded with a wife, a promising promotion in his career in England, and honors for his military service. Yet these things bring Septimus no contentment; the effects of the war on his personality begin to emerge, and he finds upon opening Shakespeare again that what mattered to him before the war, the “business of the intoxication of language – Antony and Cleopatra – had shriveled utterly” (88). Septimus exits the war with his idealism atrophied; but even worse, his connection to civilization is severed:

“He looked at people outside; happy they seemed, collecting in the middle of the street, shouting, laughing, squabbling over nothing. But he could not taste, he could not feel. In the tea-shop among the tables and the chattering waiters the appalling fear came over him – he could not feel” (87-88).

So disillusioned does Septimus become that he no longer can make the association of beautiful Miss Pole to the arts; rather he finds “the message hidden in the beauty of words . . . is loathing, hatred, despair” (88); and “human beings,” he observes, “have neither kindness, nor faith, nor charity . . . They hunt in packs . . . scour the desert and vanish screaming into the wilderness. They desert the fallen” (89). Compared to the idealistic youth who fell in love with Miss Pole, the post-war Septimus is a different person entirely, and suddenly there is an explanation for the lunatic introduced to the reader several pages earlier in the novel with his hallucinations of a man named “Evans.”

Following the detailed deterioration of Septimus’ mind comes his interaction with two different doctors, each a member of the English aristocracy; they are Dr. Holmes and Sir William Bradshaw. Septimus meets with these men at the request of his wife to receive diagnosis and treatment for his nervous breakdown. Coming from the proletariat places Septimus immediately in a position that is submissive to the bourgeoisie doctors Holmes and Bradshaw; it also puts his mental collapse into a context that allows for a Marxist interpretation of how his role in society has caused his neurosis to develop. In Dr. Holmes, Septimus first encounters the discourse of the English aristocracy, and finds to his disgust that it is a language informed by oppressive classist and patriarchal values that are ignorant of or deny the basic emotional needs that, not being met, are at the heart of Septimus’ mental breakdown.

In the passage written from Holmes’ point of view, the Smith’s are portrayed in condescending language that serves to communicate their lesser social rank and Dr. Holmes supposed superiority as a member of the bourgeois. He speaks down to his patient as one would to a child, and invokes the privilege of his rank as a doctor and aristocrat to force his way into the Smith’s home when his entry is refused by Septimus: “Did he indeed?” said Dr. Holmes, smiling agreeably. Really he had to give that charming little lady, Mrs. Smith, a friendly push before he could get past her into her husband’s bedroom” (91-92). In another example, Dr. Holmes belittles Septimus’ illness by telling him that “there [is] nothing whatever the matter” (90) with him, and suggests hobbies he could take up to distract himself, rather than offering any real medical advice. Patronizing Septimus’ illness as mere neuroticism is Dr. Holmes first step to establishing his superiority to Smith. In his second visit, a response to the patient’s talk of suicide, he invokes the patriarchal mores of male programming, and scolds Septimus for giving his wife “a very odd idea of English husbands” (91), implicating him as guilty of failing in both his duties to stoicism and patriotism as a male and a veteran.

In his failure to conform to typical male programming, Erika Baldt sees an applicability of Julia Kristeva’s definition of abjection to Septimus’ situation. Kristeva defines abjection as “the ambivalent, the border where exact limits between same and other, subject and object, and even beyond these, between inside and outside, [are] disappearing—hence an Object of fear and fascination" (qtd. in Baldt 14). Kristeva goes on to say that “at the limit, if someone personifies abjection without assurance of purification, it is a woman, ‘any woman’” (qtd. 14). Therefore, Septimus, for suffering from shell-shock, a form of hysteria, which was considered a feminine “extreme of emotion,” is seen as deviant because he does not comply with the “exact limits” of masculinity, and thus is deemed a “traitor to [his] sex” (Baldt 14). Just from his encounter with Dr. Holmes, then, Septimus is labeled as a deviant and potential threat to society. In addition, implied through the portrayal of traditionally feminine qualities in a male character, there is in the text a discourse of opposition to the biological essentialism that defined gender roles at the turn of the 19th century conflicting directly with a misogynistic and patriarchal discourse that is part of the discourse of the British Empire.

Further critique of the Empire comes out of Septimus’ encounter with Dr. Holmes in regard to the injustice of the war. It is, in fact, the callousness of his society that, internalized in Septimus, has caused his mental collapse – his interior monologue in reaction to Holmes’ insistence that nothing is wrong with him reveals this plainly: “So there was no excuse; nothing whatever the matter, except the sin for which human nature had condemned him to death; that he did not feel. He had not cared when Evans was killed; that was worst . . .” (91). It is this lack of remorse, which, because it is felt at the core of Septimus’ society and has been instilled in him through honors, through decoration as a war hero, that he has his nervous breakdown. This drives his guilt and drives him to condemn himself, and by extension, condemn the society that has instilled in him such callousness. As one critic aptly points out in his analysis, “This kind of satire on the author's part surely reveals the point of the outstanding irony in Smith's continuous self-condemnation of himself for his inability to feel. For it is precisely because he can feel that he is in such difficulty, and at such odds with society” (Samuelson 66). Having witnessed the devastation of war, in particular Evans’ death, places Septimus in the difficult and isolating position of knowing the truth of the war that is denied by the bellicose rationalization of leaders (embodied in Dr. Holmes, and later Bradshaw) who never saw the front line and dictated the terms of the war from the relative safety of their homes. Thus, “Septimus, appalled and revolted by the patriotic lies by which his fellow Londoners transform collective murder into "pleasurable . . . emotion" and himself into a war hero, is diagnosed as mad” (Froula 147).

At his encounter with Sir William Bradshaw, Septimus has worked up to his most vehement critique of his society. “Once you fall,” he says to himself, “human nature is on you. Holmes and Bradshaw are on you. They scour the desert . . . The rack and thumbscrew are applied. Human nature is remorseless” (Woolf 98). Indeed, the conflict between imperial discourse and humane discourse is at its most vehement in this encounter too. It is also worth nothing that the narrator sympathizes strongly with Septimus Smith when, for instance, she criticizes the real motivation behind Bradshaw’s socially celebrated benevolence:

“Sir William would travel sixty miles or more down into the country to visit the rich, the afflicted, who could afford the very large fee which Sir William very properly charged for his advice . . . Her ladyship waited [in the car] with the rugs about her knees . . . thinking . . . of the wall of gold mounting minute by minute while she waited . . .” (94).

The portrayal of Sir William that follows in the remainder of the passage is equally satirizing, invoking Septimus’ discourse of anti-classism and overall cynicism. This becomes apparent again especially when Sir William says that “he never spoke of ‘madness’; he called it not having a sense of proportion” (96). After which he invokes his power as a doctor and knight and makes Septimus’ case a matter of law, ‘prescribing’ him rest and isolation, as per the norm of the medicalized society of early 20th century Britain, when this is actually equivalent to a death sentence for Septimus. For Bradshaw, however, the rest cure – or isolation and quarantine to put it more plainly – is the only recourse for deviant cases such as the Smith case. Though it is disguised, this is actually a reaction of fear; “The discourse of the lunatics, who lack what Sir Bradshaw euphemistically refers to as a sense of proportion, threatens to undermine the strength of the British Empire, already in danger at the historical moment of the novel . . . the insane threaten to contaminate the "sane" who uphold and submit to the order of the Empire” (Smith 18). In other words, the discourse of the “insane” Septimus, who recognizes the impersonal treatment of Evans as a crime, must be suppressed.

Thus, Bradshaw, “worshipping proportion . . . not only prospered himself but made England prosper, secluded her lunatics, forbade childbirth, penalised despair, made it impossible for the unfit to propagate their views until they, too, shared his sense of proportion” (Woolf 99). Just as Septimus views the rest cure as a sentence rather than a treatment, so apparently does the narrator. It is a means used to silence the unruly “lunatic” who questions the established social order and the callousness of his society. This more violent side of proportion the narrator embodies as its sister: “Conversion is her name and she feasts on the wills of the weakly, loving to impress, to impose, adoring her own features stamped on the face of the populace” (100). Calling to mind images of colonialism in Africa, in India, and around the world, the word “conversion” finally sums up Septimus’ and the narrator’s view of imperial England. Through criticizing the figures in the novel who most symbolize the top of the power structure in England, the policies of the English state are criticized, both for their brutality within the country and without.

Ironically, Septimus is condemned by Bradshaw and Holmes not because he cannot feel, but because he feels too much. While the socially prescribed norm values stoicism and blind patriotism, he nevertheless can’t help but to feel repulsed by the lack of humanity in such values. Indeed, “Septimus is in many ways more sane than the "civilized" society to which he returns” (Henry 233). Septimus is not the only character in the novel to recognize his society is insane, however. Speaking of Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf herself states in the introduction to one of the early editions of her novel that “Septimus, who later is intended to be her double, had no existence; and that Mrs. Dalloway was originally to kill herself, or perhaps merely to die at the end of the party” (qtd. in Samuelson 60). Though the two characters never meet, it can be observed that Clarissa does share some of the same emotional qualities that Septimus has, if only to a lesser extent. She knows nothing of the war, and the trauma that it has inflicted on Septimus’ mind, for example, but she shares in his oppression by the patriarchal ideology of imperial England. She expresses her awareness of being so oppressed most keenly with her intense dislike of Sir Bradshaw, judging him “a great doctor yet to her obscurely evil, without sex or lust . . . but capable of some indescribably outrage – forcing your soul, that was it –“ (Woolf 184-85).

Most importantly, Clarissa Dalloway becomes the receiving vessel of Septimus’ message in her empathetic vision of his suicide and death. Faced with confinement, Septimus finally throws himself out of a window before the approaching Holmes can deliver him to Bradshaw for conversion into a yielding imperial pawn through the abuses of the rest treatment. “Lone witness of a reality that everyone around him denies, Septimus . . . suffers, owns, and tries to bear witness to his civilization's "appalling crime" but is finally forced to reenact it through a death that he expects to be read--a death that he offers as a gift, and that the narrative insulates from dismissal as madness” (Froula 149-50). Though he is “pushed” to suicide, Septimus also “jumps” (150). His final act is an act of defiance that through her empathetic vision Clarissa is capable of reading into, and even fantasizing about, before withdrawing back into the insulating world of her upper class marriage and submissive status as Richard Dalloway’s wife. Ultimately, Clarissa can’t die because as a part of the bourgeois, her life is valued more and thus insulated, doubly so because she is a female and deemed feeble by her patriarchal society.

Septimus, on the other hand, is born into the proletariat and is expendable. Even so, the meaning of Septimus’ life is not lost on Clarissa, and more importantly, can not be overlooked by the reader:

“If Clarissa's elegy for Septimus is inadequate to arraign the world before the truths it brands madness, Mrs. Dalloway captures his message within its fictional bounds for the world beyond them. Not Clarissa but we readers receive (or not) the message of Septimus's death, the costs of the war he names a "crime," the measure of what his life means to him, the infinite possibilities of his unfurling days” (151).

Thus, though Septimus exists in an isolated world apart from the superficial reality that every other character in the novel except for him resides in, his tragedy affects them all. Clarissa recognizes how in death, Septimus has preserved through his suicide “a thing . . . that mattered; a thing, wreathed about with chatter, defaced, obscured in her own life, let drop every day in corruption, lies, chatter” (Woolf 184). This thing may be his individuality, which he is unwilling to compromise to the tune of Bradshaw’s idols “Proportion” and “Conversion,” or it may be his message to a future generation to “resist,” to “defy.” Either way, Septimus’ conflict with the society that expels him represents the turmoil of his society as it quietly grieves the catastrophe of the war while stoically denying that it has taken any injury. The discourse of Septimus’ “madness” pitted against that of Dr. Holmes and Sir William Bradshaw in Mrs. Dalloway captures the tension between the patriarchal force of the dying imperial empire and the rising class discontent and interest in socialism in the early 20th century. His tragedy, in addition to questioning the established classifications of sanity and insanity, helps new historians to understand how some of the traditional and subversive discourses of this age in England interacted.

Works Cited

Baldt, Erika. "Abjection as Deviance in Mrs. Dalloway." Virginia Woolf Miscellany 70.(2006): 13-15. MLA International Bibliography. EBSCO. Web. 14 Nov. 2010.

Froula, Christine. “Mrs. Dalloway’s Postwar Elegy: Women, War, and the Art of Mourning.” Modernism/Modernity 9.1 (2002): 125-163. Project Muse. 14 November 2010. Web.

Henry, Holly. "Woolf & The War." English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 44.2 (2001): 231-235. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 2 Dec. 2010.

Samuelson, Ralph. “The Theme of Mrs. Dalloway.” Chicago Review 11.4 (Winter, 1958): 57-76. JSTOR. Web. 02 Dec. 2010

Smith, Amy. "Bad Religion: The Irrational in Mrs. Dalloway." Virginia Woolf Miscellany 70.(2006): 17-18. MLA International Bibliography. EBSCO. Web. 15 Nov. 2010

Tambling, Jeremy. “Repression in Mrs Dalloway’s London.” Essays in Criticism 39 (April 1989): 137-155. Print Copy

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. London: Harcourt, Inc., 1925. Print.

#ptsd#trauma#marxism#imperialism#united kingdom#mrs dalloway#virginia woolf#essay#essay writing#research#student#academics#war#shell shocked#complex ptsd#suicide#mental health#New Historianism#literature#literary criticism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shortly after William of Orange arrived in Devon at the outset of the Glorious Revolution in 1688, Dutch troops stationed in Dartmouth seized the Amitié, a ship laden with marble purchased for the French court at Versailles. This seizure precipitated an extraordinary insurance dispute in Paris between two little-known royal companies: the Royal Insurance Company and the Royal Marble Company. This article analyses the fractious dispute and the companies at its heart. In so doing, it reflects on the dispute as a product of the French state’s broader exploitation of companies as tools of risk management: the state leveraged private capital in order to spread the risks of its virulently anti-Dutch commercial policy. Yet the dispute also exposed the ambiguities of war and peace in seventeenth-century thought and practice. In justifying their refusal to pay out on the insurance policy they had signed on the Amitié, the Royal Insurance Company’s directors suggested that an insurer could decide unilaterally that France was in a state of war, thereby triggering a contractual clause that would shift the onus back onto the policyholder. Although Louis XIV himself stepped in to defuse the dispute at its most contentious moment, the state proved unable to respond to the challenge posed to its sovereignty, with significant consequences for the French insurance industry and maritime commerce up to the end of the Old Regime.

#to read later#uni life#history student#king louis xiv#french history#seventeenth century#i'm telling you there's nothing historians love more than gossip scandals and fights like we feed on that sh*t

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

buddie is to me what achilles and patroclus were to the girlies (gn) back in ancient greece

#911 showrunners pulling a ‘and historians say they were great friends’ on us right in front of our eyes !!!#sorry I’m a classics student and I’m thinking about haggerty (2004) talking about gay love and loss#and how homoerotic texts were usually texts of mourning because that’s the only way it was really accepted#queer love being so intertwined with loss throughout literary history is heartbreaking and I want to sob#sorry I’m just …. :((((#mol talks#911 abc#buddie

14 notes

·

View notes