#frieda hughes

Text

📝 En este poema Frieda Hughes nos muestra una mirada íntima sobre Silvia Plath y Ted Hughes, sus padres

Mi madre

La están matando otra vez.

Ella dijo que lo hacía

una vez de cada diez años,

pero ellos la matan anualmente, cada semana,

algunos incluso lo hacen a diario,

llevan su muerte en sus mentes

y la ejecutan. Les ahorran

crear sus propios problemas;

pueden morir a través de ella

sin tener que tomar

esa trágica decisión. La desentierran,

la hacen repetir sus actos.

Se les ha ocurrido hacer una película

para aquellos incapaces

de imaginar su cuerpo, cabeza en el horno,

dejando hijos en la orfandad. Luego

la rebobinarán

para poder verla morir

una y otra vez desde el inicio.

Devoradores de cacahuete,

después de haber entretenido

a costa de la muerte de mi madre, se irán a casa,

cada uno llevará su imagen,

sin vida -un suvenir.

Quizás hasta comprender el vídeo.

Cuando alguien lo ve por televisión

solo tendría que presionar “pausa”

si desea poner a hervir una tetera,

mientras mi madre contiene su aliento en la pantalla

para terminar muriendo después del té.

Los productores han reunido

trozos de su cuerpo,

quieren que los vean.

Requieren apósitos para cubrir uniones

y disimular las prótesis

de esta nueva versión de mi madre.

Quieren usar su poesía

como costuras y suturas

para darle credibilidad.

Piensan que debería fascinarme-

tenerla de regreso, piensan

que debería darles los versos de mi madre

para llenar la boca de su monstruo,

esa muñeca suicida llamada Sylvia,

que caminará y hablará

y morirá a voluntad,

y morirá, y morirá

y por siempre seguirá muriendo.

#Ted Hughes#Frieda Hughes#silvia plath#literatura#cultura#narrativa#herederos del kaos#poesía#poesías#poemas#cuentos#relatos

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

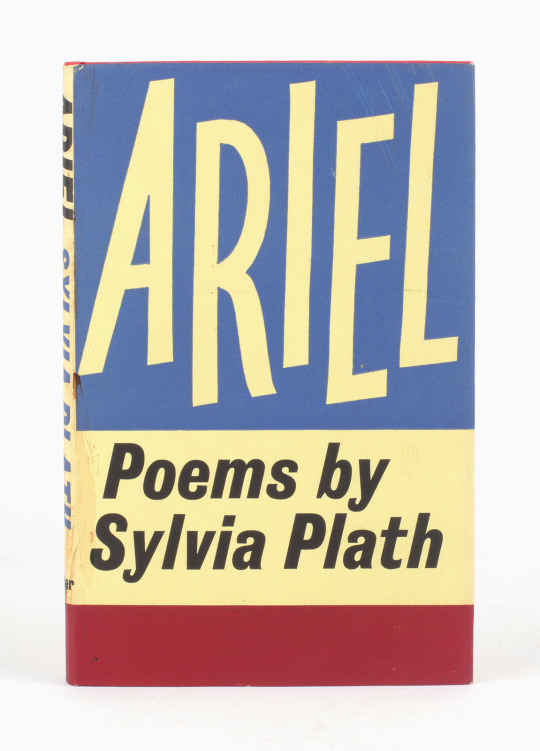

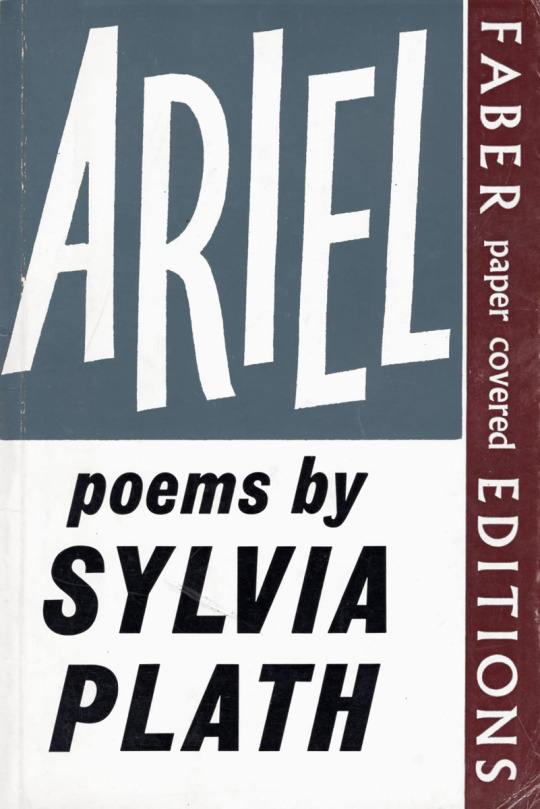

Sylvia Plath, Ariel, Introduction by Robert Lowell, Edited by Ted Hughes, Faber and Faber, London, 1965 [altered for publication by Ted Hughes; then Ariel: The Restored Edition, Foreword by Frieda Hughes, Faber and Faber, London, 2004, Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement (Internet Archive here)] [Jonkers Rare Books, Henley-on-Thames]

#graphic design#typography#poetry#book#cover#book cover#back cover#sylvia plath#robert lowell#ted hughes#frieda hughes#faber and faber#1960s#2000s

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

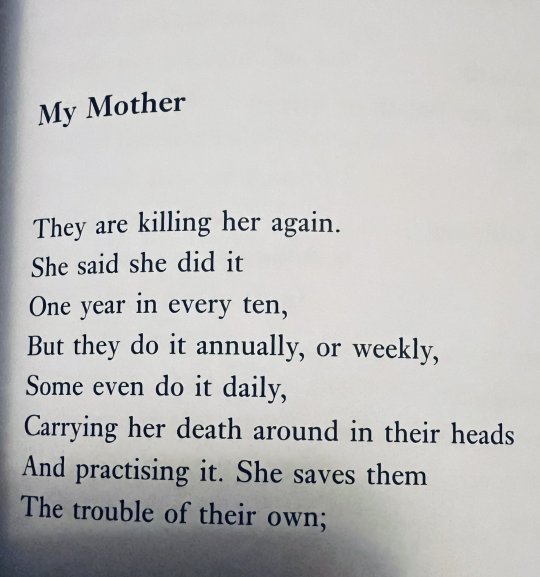

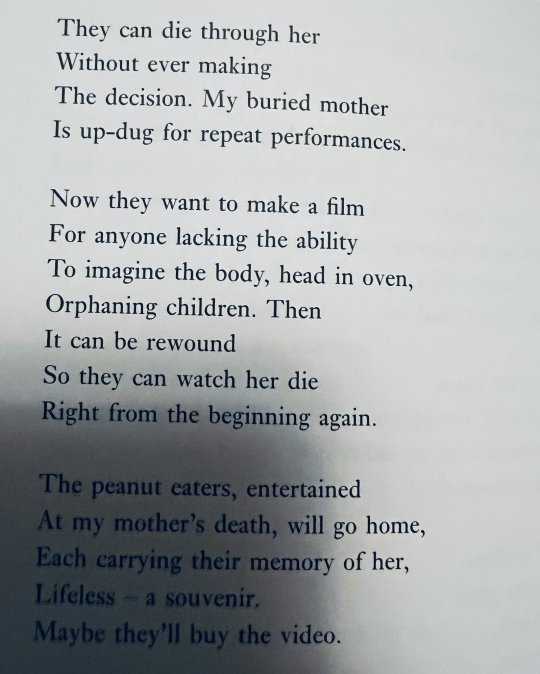

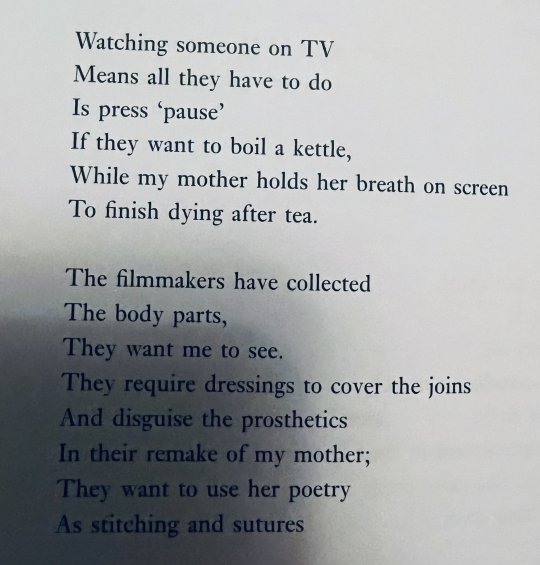

My Mother - Frieda Hughes

They are killing her again.

She said she did it

One year in every ten,

But they do it annually, or weekly,

Some even do it daily,

Carrying her death around in their heads

And practising it. She saves them

The trouble of their own;

They can die through her

Without ever making

The decision. My buried mother

Is up-dug for repeat performances.

Now they want to make a film

For anyone lacking the ability

To imagine the body, head in oven,

Orphaning children. Then

It can be rewound

So they can watch her die

Right from the beginning again.

The peanut eaters, entertained

At my mother’s death, will go home,

Each carrying their memory of her,

Lifeless – a souvenir.

Maybe they’ll buy the video.

Watching someone on TV

Means all they have to do

Is press ‘pause’

If they want to boil a kettle,

While my mother holds her breath on screen

To finish dying after tea.

The filmmakers have collected

The body parts,

They want me to see.

They require dressings to cover the joins

And disguise the prosthetics

In their remake of my mother.

They want to use her poetry

As stitching and sutures

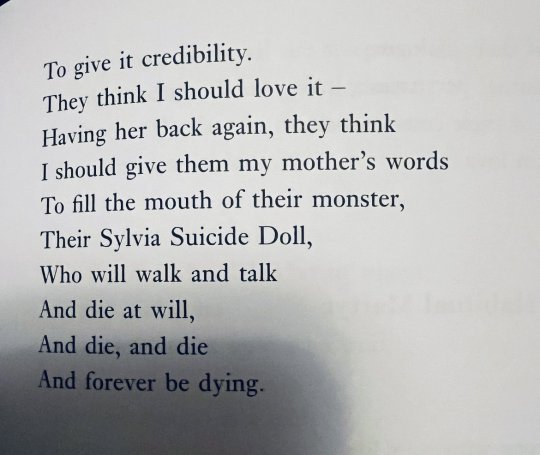

To give it credibility.

They think I should love it –

Having her back again, they think

I should give them my mother’s words

To fill the mouth of their monster,

Their Sylvia Suicide Doll,

Who will walk and talk

And die at will,

And die, and die

And forever be dying.

A poem by Frieda Hughes, Sylvia Plath's daughter.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Mother

They are killing her again.

She said she did it

One year in every ten,

But they do it annually, or weekly,

Some even do it daily,

Carrying her death around in their heads

And practising it. She saves them

The trouble of their own;

They can die through her

Without ever making

The decision. My buried mother

Is up-dug for repeat performances.

Now they want to make a film

For anyone lacking the ability

To imagine the body, head in oven,

Orphaning children. Then

It can be rewound

So they can watch her die

Right from the beginning again.

The peanut eaters, entertained

At my mother’s death, will go home,

Each carrying their memory of her,

Lifeless – a souvenir.

Maybe they’ll buy the video.

Watching someone on TV

Means all they have to do

Is press ‘pause’

If they want to boil a kettle,

While my mother holds her breath on screen

To finish dying after tea.

The filmmakers have collected

The body parts,

They want me to see.

They require dressings to cover the joins

And disguise the prosthetics

In their remake of my mother.

They want to use her poetry

As stitching and sutures

To give it credibility.

They think I should love it –

Having her back again, they think

I should give them my mother’s words

To fill the mouth of their monster,

Their Sylvia Suicide Doll,

Who will walk and talk

And die at will,

And die, and die

And forever be dying.

Frieda Hughes, about her mother Sylvia Plath

Published in The Stonepicker and The Book of Mirrors

#Frieda Hughes#poetry#Sylvia Plath#Ted Hughes#poem#mother#suicide#death#unaliving#unalive#TV#entertainment#sad#sorrow#memories#parasocial

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Keziah Weir

Frieda Hughes and I are an hour into our conversation when Wyddfa the snowy owl enters the chat. With some coaxing, he has hopped down the hallway, lined with woven rugs, to perch next to Hughes in her high-ceilinged kitchen. The pair of them, framed by a Zoom square, are in their home in Wales, where they live with 12 other owls, plus “five chinchillas,” Hughes says, “one aging ferret, a python called Shirley, and the two rescue huskies.” By publication of this piece, she has added a fourteenth owl.

Wyddfa, who is so dapper that he immediately elicits very silly comments from this interviewer—Hello, sir! He’s a little gentleman!—joined the household in 2016 after a zoo could no longer care for him because of a damaged wing; another of the owls has “wonky feet.” All of them have an avian forebear, without whom the parliament might never have found their way into Hughes’s care: an orphaned fledgling, now the eponymous subject of her new book, George: A Magpie Memoir (Avid Reader Press). The book chronicles the five months in 2007 during which Hughes hand-raised the magpie after finding it tossed from a nest in her garden. “I had no idea how much I was going to fall in love with that bird,” Hughes tells me. “Oh, dear.”

London-born Hughes, a painter and poet, describes her growing up as peripatetic. “I felt as if the ground on which I stood was constantly changing and shifting,” she writes in the introduction to George, “because, following the suicide of my mother, Sylvia Plath, on 11 February 1963, my father, Ted Hughes, found it difficult to settle.” Her parents play a small role on the memoir’s pages, though the reverberations of their loss are felt throughout; most explicitly, Hughes notes the surreal feeling of strangers knowing, or believing to know, the intimacies of her personal history. (In the early aughts, the filmmakers behind the 2003 Gwyneth Paltrow vehicle Sylvia requested that Hughes grant them the right to use Plath’s poems. The film, Hughes wrote in her own poem, “My Mother,” would be “for anyone lacking the ability / To imagine the body, head in oven, / Orphaning children.” Needless to say, she did not grant the request.)

As a child, the ability to keep animals became an elusive sign of permanence—“if I had a pet it should mean that I’d have found a home in which to be stationary,” she writes—something she says she has finally found.

During the five months of George, Hughes was grappling with the impending dissolution of a marriage—she and her husband had, three years earlier, moved together from his native Australia to Wales and he longed to return home—and her own chronic fatigue. An incessantly needy and increasingly tricksy young magpie proved to be a consuming diversion for Hughes, though not everyone was as charmed by his penchant for stealing food off plates or landing on heads. “Oh, there’s a magpie on the sofa,” Hughes quotes one visitor saying “with an offhand sort of grimace.” As a reader, it’s hard not to fall a little in love with him, an attachment aided by Hughes’s illustrations of him that run throughout the text.

Hughes has long been attracted to what she describes as “the wounded and the limping.” As a child, she says, “there were lots of little tragedies because I wanted to save everything, and couldn’t”—a theme that continues in her memoir. “If only I could have found it before the cat and the fly eggs,” she writes of another orphaned bird that died in her care, “if only I had a magic wand.” Still, as much as she acknowledges the difficult inevitability of death, she clocks lifeforce all around too. Of the wiggly garden creatures she collects to feed to baby George: “If worms had only a single thought in their little nematode bodies, it was that they wanted to LIVE.”

Before our interview, Hughes had been riding around the countryside on her motorbike when it broke down, stranding her, but she seems unbothered by the hiccup outside of apologizing that it had made her late for the call. There’s a forward momentum to her, a sort of indefatigable sense of thrust. One accepts difficulty, and moves forward. “He’s stuck on the ground,” she says fondly of Wyddfa, before we say goodbye—but “he makes the most of it.”

Here, we discuss George, learning to open up after years of secrecy, and how to love despite the promise of loss.

Vanity Fair: I’m always interested in the why now of memoir. What made you want to revisit this time with George?

Frieda Hughes: Well, actually, I wrote it as George happened. A year later, I turned it into a book and then I tried to get it published. I had a publisher who was interested and then, I'll be perfectly frank, my brother committed suicide, and I thought I can't actually cope with the book and dealing with my brother's death at the same time, and so I put it on the back burner.

When, finally, my brother's affairs were all sorted out, and everything else, I thought, okay, I can revisit the book, I can get back to my art, I can get back to my painting and my poetry. I think I probably rewrote the book over the following years. Then I wrote an article about keeping owls for the Financial Times, and Cecil Gayford, my editor, saw this article and said to my agent, would Frieda consider writing about her love for birds, and she said, well, she already has.

I have a new appreciation for magpies after reading the book—I had always really loved crows and ravens, but I hadn't thought so much about magpies.

Where I live in the country, magpies are not regarded with great affection. They're regarded as pests and killers of baby birds. They get an awful lot of bad press, but in fact, all corvids are more interested in clearing up dead things. Ravens are apparently the supreme intelligence of the corvids; crows are very serious—so smart, so clever, but very, very serious. Magpies are complete imps, absolutely mischievous, curious. Honestly, I swear they have a sense of humor.

I remember a couple of girlfriends coming to visit and one of them was taking loads of photographs, and George was performing for them. He sat on my head, he nibbled my eyelashes, which is a bit unnerving because I could feel his beak against my eyeball, but he was adorable, and afterwards, my friend contacted me and said, "Frieda, I took all these photos and you can hardly see him. He's just a little bird." The thing is, we can't photograph the personality, can we, and that's what's so frustrating. His personality was extraordinary, and one of the things that really hooked its way into my heart was the fact that he related to me. The dogs would come up for a pet or a stroke or a snack, but George would look at what I was doing and play with it. When I was doing sketches of him, he would come and sit on the paper and try and pull the lines off the paper.

He was probably only a couple of days old when you found him. I wondered how you think that played into the attachment that you had to George, that you had rescued him and that he needed you.

Hugely, because the more needy and desperate an animal or bird is, the higher up the priority list they come. George really needed feeding. He had the droopy wing, I didn't even know if he would ever learn to feed himself. It wasn't until I was working in the garden and I would uncover, on more than one occasion, a dead mouse, and George would be watching and suddenly, he appears and grabs the mouse and flies off and I thought, you know what? I think George is going to be fine.

It is such a different project to raise an animal with the hope that they will be able to return to the wild. I think that's something that most people don't experience. Usually, you're raising an animal who you hope will be with you till the very end. In some ways, your experience seems almost much more like child-rearing where the goal is for children to grow up and take care of themselves.

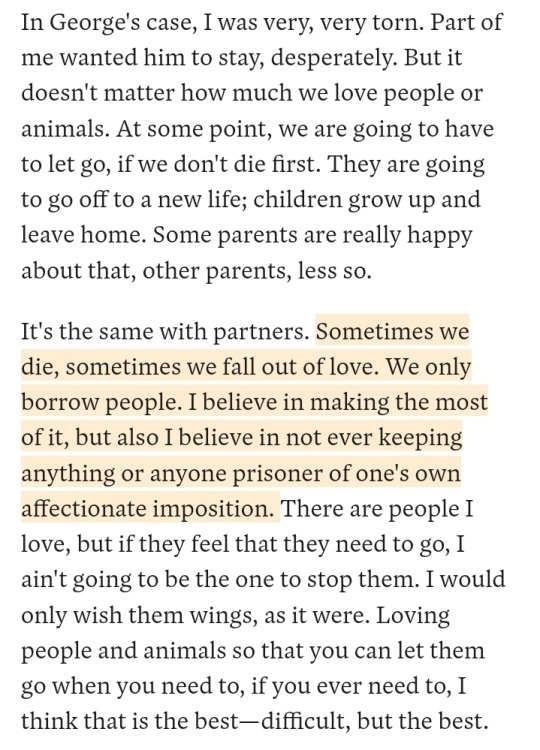

In George's case, I was very, very torn. Part of me wanted him to stay, desperately. But it doesn't matter how much we love people or animals. At some point, we are going to have to let go, if we don't die first. They are going to go off to a new life; children grow up and leave home. Some parents are really happy about that, other parents, less so.

It's the same with partners. Sometimes we die, sometimes we fall out of love. We only borrow people. I believe in making the most of it, but also I believe in not ever keeping anything or anyone prisoner of one's own affectionate imposition. There are people I love, but if they feel that they need to go, I ain't going to be the one to stop them. I would only wish them wings, as it were. Loving people and animals so that you can let them go when you need to, if you ever need to, I think that is the best—difficult, but the best.

In the book, you wrote about your now ex-husband. There was a mirroring going on—him wanting to go back to where he was from, and dealing with that in the relationship as you were also dealing with the fact that your bird was wanting to go back to the wild, where he was from.

Yes, very much. He had said that he wanted to move back when he got old, only he wasn't able to tell me what old meant. He was 14 years older than me, so he was 14 years ahead of where my head was. He, too, ultimately needed his freedom. One might make all the effort one could to make things nice, but if somebody wants to go, they want to go—and also, quite often, by the time they want to go, we are quite glad for them to go.

In George's case, not. But having said that, he was complicated by these bad habits he developed, like the one of jumping on heads, which scared my elderly neighbor to the point where she wouldn't go out of the house if there were magpies in the garden. Hence the aviary, that enormous aviary, now populated by six very large Eurasian eagle owls.

They are alluded to at the very end of the book. I want to hear about who you have right now.

The first owl was Arthur, with the broken wing. Three of the owls that I have were given to me by other people who could no longer look after them; one had an operation on his shoulder, and another one was just incredibly sick and had diabetes, and so I got these owls and they came with two eggs. So I bought an incubator and hatched Charlie and Mac in 2015, and then two years later came Eddie, and they are fabulous. They're very, very handleable. They come in the house for a couple of hours at night just to play around in the kitchen

In the time period of the book you were working on a collection of autobiographical poems, which seemed to take a lot out of you emotionally. Over the years, how have you juggled a desire for a certain amount of privacy, but then also wanting to draw from your life and feelings in your writing?

I'm working on balancing it all the time, because the answer is I'm not sure how to balance it. When I was younger and my father was still alive, the wish to be private on his behalf, not to say... I'll give you an example. The other kids would come back from a weekend and say, we did this and we did that and we did the other. I wasn't ever sure what I could give away or not give away, what would be okay.

In my first book of poems, it became really difficult because that's where we start, with our innermost emotions and feelings. I had all these poems boiling away. For years, I wrote poetry and never told anybody. Ultimately, I worked up to showing my dad my poems. He'd have criticism, and finally one day—I think I must have been about 15, 16, 17—I said, "Daddy, don't you have anything good to say?" He looked at me in complete surprise and he said, "But I thought you knew they were very good. I was only mentioning the bits that need pushing.” From then on, he would say, “Okay, this bit's brilliant and that works really well.” He was a very good teacher, but at the same time, I was trying not to read any of his poetry or my mother's poetry because I didn't want to be influenced.

My first book I wrote while I had chronic fatigue. I wanted to be autobiographical and I didn't dare. I'd trained myself so seriously to be private for the family's sake. So allegory became my best friend. And then in 2007, I set myself certain parameters for the autobiographical poetry book, 45. One was that I could be open about myself. When you say it must have been emotionally taxing or challenging, it was, because it was like stripping my skin off because I wasn't used to it. I hadn't had that practice.

In the end, as I get older, I think, does it matter? I'm getting older. One day, we're going to die. If I was publishing my autobiography at the age of 96, I wouldn't care much about what I put in it. I'd just put everything in it, but I'd have to be 96 because then I know I was probably on the way out. So I don't know. I'm working on it.

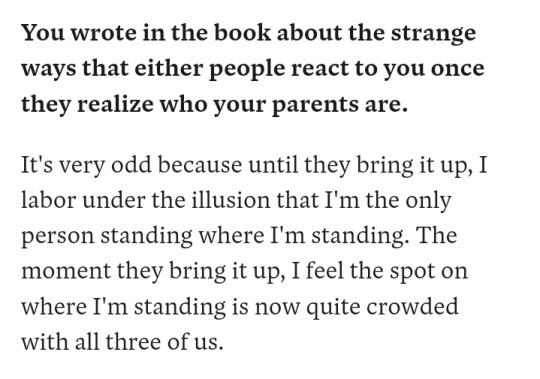

You wrote in the book about the strange ways that either people react to you once they realize who your parents are.

It's very odd because until they bring it up, I labor under the illusion that I'm the only person standing where I'm standing. The moment they bring it up, I feel the spot on where I'm standing is now quite crowded with all three of us.

In your poem “Mother,” you’re writing about the strange idea that there are people who are portraying your parents in different ways and dramatizing, or writing biographies or making movies. Is that something that has gotten easier, emotionally, as you have dealt with it over the course of your life?

One of the difficulties is when people make up whole sentences and relationships and ways of speaking and there's nothing to support it. I've been very determined to make a home in which I feel safe, and create my own support and not look at those things because there's no point. I could rant and rave. I'm not going to change anything.

So poetry is where I put things I feel very, very strongly about, and reading a poem like that on stage, you feel as though you're delivering it as a killer blow. It might only be for one moment in the ether, but it's something. When people reinvent my parents, it'd be like anybody reinventing yours or anybody else's parents. It's wounding and it takes them away.

When articles or books have come out that depict negative versions of your parents’ relationship, do you just try to steer clear of that as well?

Well, they're rehashing it. It's been written about a lot. There was the very good recent biography by Heather Clark, Red Comet, very thorough. I had to read that for permissions, and I thought it was a really masterful piece of work. It didn't impose judgment and it didn't guess at anything. Everything was backed by research and reading, and for that reason, I found it really impressive.

You have this rule, you wrote, to live each day the best you can no matter what—having experienced significant and public loss, and then also dealing with chronic health problems, how have you kept that up?

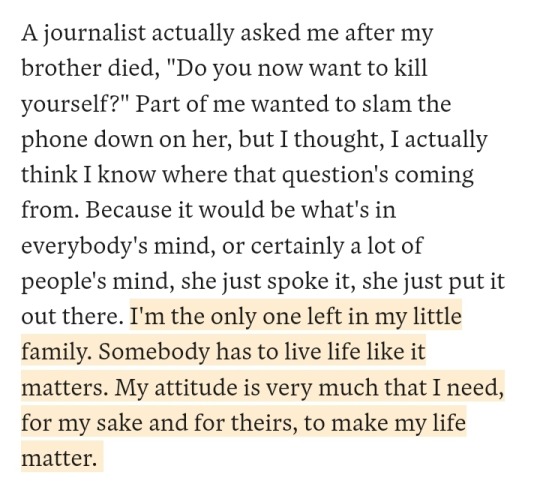

I can't believe I was in such pain when I was looking after George. I still get back pains, I still have problems with it, but I'm so much better. I work out at the gym three times a week, I do the gardening. I'm actually in better nick than I was then, and although they say that we never get rid of chronic fatigue, it's like a little warning sign; if I ever feel that coming, I now know, hey, I'm doing something wrong

A journalist actually asked me after my brother died, "Do you now want to kill yourself?" Part of me wanted to slam the phone down on her, but I thought, I actually think I know where that question's coming from. Because it would be what's in everybody's mind, or certainly a lot of people's mind, she just spoke it, she just put it out there. I'm the only one left in my little family. Somebody has to live life like it matters. My attitude is very much that I need, for my sake and for theirs, to make my life matter.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Mother by Frieda Hughes

#frieda hughes#poetry#the way we consume celebrities and spit them out like all they are is entertainment like their suffering was okay bc it fed you#let them rest

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wild oats pale as peroxide lie down among

The bottle brushes. A beaten army, bleaching.

Life bled into the earth already, and seeds awaiting.

Stiff little spiked children wanting water.

Above the creek that split apart the earth

With drunken gait and crooked pathway,

Kookaburras sit in eucalyptus. Squat and sharp-throated

They haggle maggots and branches from ring-necked parrots.

I have watched the green flourish twice, and die,

And the marsh dry. In this valley I have been hollowed out

And mended. I echo in my own emptiness like a tongue

In a bird’s beak. My words are all gone.

Out of my mouth comes this dumb kookaburra laugh.

How my feathers itch.

0 notes

Text

But it doesn't matter how much we love people or animals. At some point, we are going to have to let go, if we don't die first. They are going to go off to a new life; children grow up and leave home. Some parents are really happy about that, other parents, less so.

It's the same with partners. Sometimes we die, sometimes we fall out of love. We only borrow people. I believe in making the most of it, but also I believe in not ever keeping anything or anyone prisoner of one's own affectionate imposition. There are people I love, but if they feel that they need to go, I ain't going to be the one to stop them. I would only wish them wings, as it were. Loving people and animals so that you can let them go when you need to, if you ever need to, I think that is the best—difficult, but the best.

- Frieda Hughes, Vanity Fair interview 2023

0 notes

Text

from this interview with Sylvia Plath's daughter, Frieda Hughes

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Alchemy Spoon on friendship

Thank you Tamsin Hopkins for selecting one of my poems for The Alchemy Spoon (issue 10), where the theme of ‘Friends’ inspired some cracking poetry. From stories of herring girls, travel companions and brothers-in-law, to doggy friendship, childhood friends and friendly divorce, all of life is here.

Poets featured in this issue include: Sharon Ashton, Julian Bishop, Claire Booker, Matthew Caley,…

View On WordPress

#Claire Booker#contemporary poetry#Frieda Hughes#new writing#poems#Robin Houghton#Sylvia Plath#Tamsin Hopkins#The Alchemy Spoon

0 notes

Text

HAPPY 64th BIRTHDAY Frieda Rebecca Hughes!!!

(born 1 April 1960 in London, England)

http://www.friedahughes.com/

...

Photo: Frieda Hughes, photographed in her garden by Francesca Jones/The Observer

Source: https://www.theguardian.com

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sylvia Plath, (1965), Ariel, Introduction by Robert Lowell, Edited by Ted Hughes, Faber and Faber, London, 1971 [altered for publication by Ted Hughes; then Ariel: The Restored Edition, Foreword by Frieda Hughes, Faber and Faber, London, 2004, Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement (Internet Archive here)]

#graphic design#typography#poetry#book#cover#book cover#back cover#sylvia plath#robert lowell#ted hughes#frieda hughes#faber and faber#1960s#1970s

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Keziah Weir

Frieda Hughes and I are an hour into our conversation when Wyddfa the snowy owl enters the chat. With some coaxing, he has hopped down the hallway, lined with woven rugs, to perch next to Hughes in her high-ceilinged kitchen. The pair of them, framed by a Zoom square, are in their home in Wales, where they live with 12 other owls, plus “five chinchillas,” Hughes says, “one aging ferret, a python called Shirley, and the two rescue huskies.” By publication of this piece, she has added a fourteenth owl.

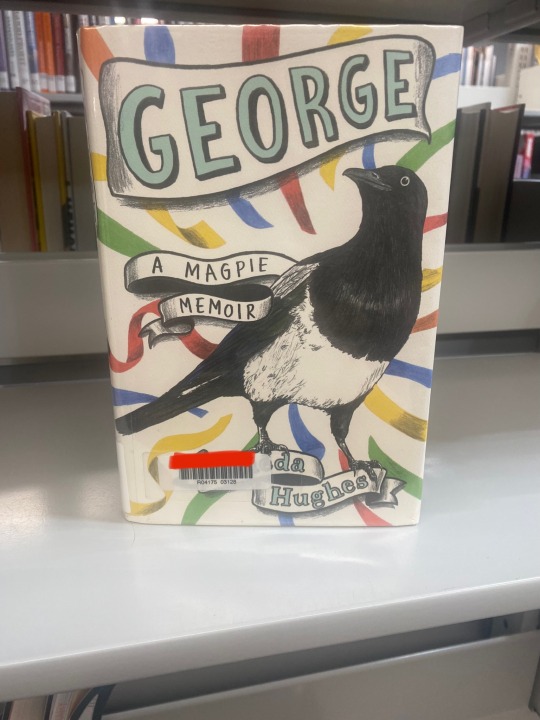

Wyddfa, who is so dapper that he immediately elicits very silly comments from this interviewer—Hello, sir! He’s a little gentleman!—joined the household in 2016 after a zoo could no longer care for him because of a damaged wing; another of the owls has “wonky feet.” All of them have an avian forebear, without whom the parliament might never have found their way into Hughes’s care: an orphaned fledgling, now the eponymous subject of her new book, George: A Magpie Memoir (Avid Reader Press). The book chronicles the five months in 2007 during which Hughes hand-raised the magpie after finding it tossed from a nest in her garden. “I had no idea how much I was going to fall in love with that bird,” Hughes tells me. “Oh, dear.”

London-born Hughes, a painter and poet, describes her growing up as peripatetic. “I felt as if the ground on which I stood was constantly changing and shifting,” she writes in the introduction to George, “because, following the suicide of my mother, Sylvia Plath, on 11 February 1963, my father, Ted Hughes, found it difficult to settle.” Her parents play a small role on the memoir’s pages, though the reverberations of their loss are felt throughout; most explicitly, Hughes notes the surreal feeling of strangers knowing, or believing to know, the intimacies of her personal history. (In the early aughts, the filmmakers behind the 2003 Gwyneth Paltrow vehicle Sylvia requested that Hughes grant them the right to use Plath’s poems. The film, Hughes wrote in her own poem, “My Mother,” would be “for anyone lacking the ability / To imagine the body, head in oven, / Orphaning children.” Needless to say, she did not grant the request.)

As a child, the ability to keep animals became an elusive sign of permanence—“if I had a pet it should mean that I’d have found a home in which to be stationary,” she writes—something she says she has finally found.

During the five months of George, Hughes was grappling with the impending dissolution of a marriage—she and her husband had, three years earlier, moved together from his native Australia to Wales and he longed to return home—and her own chronic fatigue. An incessantly needy and increasingly tricksy young magpie proved to be a consuming diversion for Hughes, though not everyone was as charmed by his penchant for stealing food off plates or landing on heads. “Oh, there’s a magpie on the sofa,” Hughes quotes one visitor saying “with an offhand sort of grimace.” As a reader, it’s hard not to fall a little in love with him, an attachment aided by Hughes’s illustrations of him that run throughout the text.

Hughes has long been attracted to what she describes as “the wounded and the limping.” As a child, she says, “there were lots of little tragedies because I wanted to save everything, and couldn’t”—a theme that continues in her memoir. “If only I could have found it before the cat and the fly eggs,” she writes of another orphaned bird that died in her care, “if only I had a magic wand.” Still, as much as she acknowledges the difficult inevitability of death, she clocks lifeforce all around too. Of the wiggly garden creatures she collects to feed to baby George: “If worms had only a single thought in their little nematode bodies, it was that they wanted to LIVE.”

Before our interview, Hughes had been riding around the countryside on her motorbike when it broke down, stranding her, but she seems unbothered by the hiccup outside of apologizing that it had made her late for the call. There’s a forward momentum to her, a sort of indefatigable sense of thrust. One accepts difficulty, and moves forward. “He’s stuck on the ground,” she says fondly of Wyddfa, before we say goodbye—but “he makes the most of it.”

Here, we discuss George, learning to open up after years of secrecy, and how to love despite the promise of loss.

Vanity Fair: I’m always interested in the why now of memoir. What made you want to revisit this time with George?

Frieda Hughes: Well, actually, I wrote it as George happened. A year later, I turned it into a book and then I tried to get it published. I had a publisher who was interested and then, I'll be perfectly frank, my brother committed suicide, and I thought I can't actually cope with the book and dealing with my brother's death at the same time, and so I put it on the back burner.

When, finally, my brother's affairs were all sorted out, and everything else, I thought, okay, I can revisit the book, I can get back to my art, I can get back to my painting and my poetry. I think I probably rewrote the book over the following years. Then I wrote an article about keeping owls for the Financial Times, and Cecil Gayford, my editor, saw this article and said to my agent, would Frieda consider writing about her love for birds, and she said, well, she already has.

I have a new appreciation for magpies after reading the book—I had always really loved crows and ravens, but I hadn't thought so much about magpies.

Where I live in the country, magpies are not regarded with great affection. They're regarded as pests and killers of baby birds. They get an awful lot of bad press, but in fact, all corvids are more interested in clearing up dead things. Ravens are apparently the supreme intelligence of the corvids; crows are very serious—so smart, so clever, but very, very serious. Magpies are complete imps, absolutely mischievous, curious. Honestly, I swear they have a sense of humor.

I remember a couple of girlfriends coming to visit and one of them was taking loads of photographs, and George was performing for them. He sat on my head, he nibbled my eyelashes, which is a bit unnerving because I could feel his beak against my eyeball, but he was adorable, and afterwards, my friend contacted me and said, "Frieda, I took all these photos and you can hardly see him. He's just a little bird." The thing is, we can't photograph the personality, can we, and that's what's so frustrating. His personality was extraordinary, and one of the things that really hooked its way into my heart was the fact that he related to me. The dogs would come up for a pet or a stroke or a snack, but George would look at what I was doing and play with it. When I was doing sketches of him, he would come and sit on the paper and try and pull the lines off the paper.

He was probably only a couple of days old when you found him. I wondered how you think that played into the attachment that you had to George, that you had rescued him and that he needed you.

Hugely, because the more needy and desperate an animal or bird is, the higher up the priority list they come. George really needed feeding. He had the droopy wing, I didn't even know if he would ever learn to feed himself. It wasn't until I was working in the garden and I would uncover, on more than one occasion, a dead mouse, and George would be watching and suddenly, he appears and grabs the mouse and flies off and I thought, you know what? I think George is going to be fine.

It is such a different project to raise an animal with the hope that they will be able to return to the wild. I think that's something that most people don't experience. Usually, you're raising an animal who you hope will be with you till the very end. In some ways, your experience seems almost much more like child-rearing where the goal is for children to grow up and take care of themselves.

In George's case, I was very, very torn. Part of me wanted him to stay, desperately. But it doesn't matter how much we love people or animals. At some point, we are going to have to let go, if we don't die first. They are going to go off to a new life; children grow up and leave home. Some parents are really happy about that, other parents, less so.

It's the same with partners. Sometimes we die, sometimes we fall out of love. We only borrow people. I believe in making the most of it, but also I believe in not ever keeping anything or anyone prisoner of one's own affectionate imposition. There are people I love, but if they feel that they need to go, I ain't going to be the one to stop them. I would only wish them wings, as it were. Loving people and animals so that you can let them go when you need to, if you ever need to, I think that is the best—difficult, but the best.

In the book, you wrote about your now ex-husband. There was a mirroring going on—him wanting to go back to where he was from, and dealing with that in the relationship as you were also dealing with the fact that your bird was wanting to go back to the wild, where he was from.

Yes, very much. He had said that he wanted to move back when he got old, only he wasn't able to tell me what old meant. He was 14 years older than me, so he was 14 years ahead of where my head was. He, too, ultimately needed his freedom. One might make all the effort one could to make things nice, but if somebody wants to go, they want to go—and also, quite often, by the time they want to go, we are quite glad for them to go.

In George's case, not. But having said that, he was complicated by these bad habits he developed, like the one of jumping on heads, which scared my elderly neighbor to the point where she wouldn't go out of the house if there were magpies in the garden. Hence the aviary, that enormous aviary, now populated by six very large Eurasian eagle owls.

They are alluded to at the very end of the book. I want to hear about who you have right now.

The first owl was Arthur, with the broken wing. Three of the owls that I have were given to me by other people who could no longer look after them; one had an operation on his shoulder, and another one was just incredibly sick and had diabetes, and so I got these owls and they came with two eggs. So I bought an incubator and hatched Charlie and Mac in 2015, and then two years later came Eddie, and they are fabulous. They're very, very handleable. They come in the house for a couple of hours at night just to play around in the kitchen

In the time period of the book you were working on a collection of autobiographical poems, which seemed to take a lot out of you emotionally. Over the years, how have you juggled a desire for a certain amount of privacy, but then also wanting to draw from your life and feelings in your writing?

I'm working on balancing it all the time, because the answer is I'm not sure how to balance it. When I was younger and my father was still alive, the wish to be private on his behalf, not to say... I'll give you an example. The other kids would come back from a weekend and say, we did this and we did that and we did the other. I wasn't ever sure what I could give away or not give away, what would be okay.

In my first book of poems, it became really difficult because that's where we start, with our innermost emotions and feelings. I had all these poems boiling away. For years, I wrote poetry and never told anybody. Ultimately, I worked up to showing my dad my poems. He'd have criticism, and finally one day—I think I must have been about 15, 16, 17—I said, "Daddy, don't you have anything good to say?" He looked at me in complete surprise and he said, "But I thought you knew they were very good. I was only mentioning the bits that need pushing.” From then on, he would say, “Okay, this bit's brilliant and that works really well.” He was a very good teacher, but at the same time, I was trying not to read any of his poetry or my mother's poetry because I didn't want to be influenced.

My first book I wrote while I had chronic fatigue. I wanted to be autobiographical and I didn't dare. I'd trained myself so seriously to be private for the family's sake. So allegory became my best friend. And then in 2007, I set myself certain parameters for the autobiographical poetry book, 45. One was that I could be open about myself. When you say it must have been emotionally taxing or challenging, it was, because it was like stripping my skin off because I wasn't used to it. I hadn't had that practice.

In the end, as I get older, I think, does it matter? I'm getting older. One day, we're going to die. If I was publishing my autobiography at the age of 96, I wouldn't care much about what I put in it. I'd just put everything in it, but I'd have to be 96 because then I know I was probably on the way out. So I don't know. I'm working on it.

You wrote in the book about the strange ways that either people react to you once they realize who your parents are.

It's very odd because until they bring it up, I labor under the illusion that I'm the only person standing where I'm standing. The moment they bring it up, I feel the spot on where I'm standing is now quite crowded with all three of us.

In your poem “Mother,” you’re writing about the strange idea that there are people who are portraying your parents in different ways and dramatizing, or writing biographies or making movies. Is that something that has gotten easier, emotionally, as you have dealt with it over the course of your life?

One of the difficulties is when people make up whole sentences and relationships and ways of speaking and there's nothing to support it. I've been very determined to make a home in which I feel safe, and create my own support and not look at those things because there's no point. I could rant and rave. I'm not going to change anything.

So poetry is where I put things I feel very, very strongly about, and reading a poem like that on stage, you feel as though you're delivering it as a killer blow. It might only be for one moment in the ether, but it's something. When people reinvent my parents, it'd be like anybody reinventing yours or anybody else's parents. It's wounding and it takes them away.

When articles or books have come out that depict negative versions of your parents’ relationship, do you just try to steer clear of that as well?

Well, they're rehashing it. It's been written about a lot. There was the very good recent biography by Heather Clark, Red Comet, very thorough. I had to read that for permissions, and I thought it was a really masterful piece of work. It didn't impose judgment and it didn't guess at anything. Everything was backed by research and reading, and for that reason, I found it really impressive.

You have this rule, you wrote, to live each day the best you can no matter what—having experienced significant and public loss, and then also dealing with chronic health problems, how have you kept that up?

I can't believe I was in such pain when I was looking after George. I still get back pains, I still have problems with it, but I'm so much better. I work out at the gym three times a week, I do the gardening. I'm actually in better nick than I was then, and although they say that we never get rid of chronic fatigue, it's like a little warning sign; if I ever feel that coming, I now know, hey, I'm doing something wrong

A journalist actually asked me after my brother died, "Do you now want to kill yourself?" Part of me wanted to slam the phone down on her, but I thought, I actually think I know where that question's coming from. Because it would be what's in everybody's mind, or certainly a lot of people's mind, she just spoke it, she just put it out there. I'm the only one left in my little family. Somebody has to live life like it matters. My attitude is very much that I need, for my sake and for theirs, to make my life matter.

0 notes

Text

“my mother” by frieda hughes, sylvia plath’s daughter

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book of the day! “George: A Magpie Memoir” by Frieda Hughes. This diary style book follows the author’s experience rescuing and raising a magpie chick. The little scavenger helps her find out new thing about herself in a way only nature can.

14 notes

·

View notes