#moral philosophy

Text

ID: Screenshot reading "You will recognise it as an arguable point as soon as you switch the victim to a species that you think morally matters. Humans will inevitably die too" followed by a comma before the screenshot cuts off. It is not shown who the author is.

Preface: This will be a long post, but I think it's worthwhile as part of my efforts to open up real conversation about psychopathy and the stigma + misinformation surrounding it. The main reason I'm making a separate post instead of reblogging is that this post is not really intended to be about veganism. I'm more using the contents of the above screenshot to dive more into a topic I've touched on a few times recently.

Humans being "a species that you think morally matters" is an interesting assumption I often see vegan activists make. I've been undecided for a while about talking about this because I know how controversial this is and don't feel a strong desire to deal with the fallout of posting it/saying it outright, but seeing as I've always tried to be as honest and open as possible in here: I do not actually think humans "morally matter." I do not think killing is inherently wrong, either, regardless of species. Just about every creature on Earth engages in killing, either of each other or of members of other species, if not both. I don't think humans are sacred or special in any way, and thus are no exception. I don't see humans killing each other as any more INHERENTLY (this word is incredibly important here... obviously) wrong than, say, leopards killing each other. My culture used to engage in religious human sacrifice, so I have thought about this a whole lot, and it is a bit of a discourse topic in my community to this day (some even think we would be better off today if we had not stopped giving human sacrifices to the gods).

Most arguments for killing being inherently immoral that I've encountered are directly or indirectly rooted in religion, a societal value accepted without question, and/or the result of emotional reactions. One response I often get to this is that if I don't think killing is inherently wrong, I'm not allowed to be sad about it or grieve when people are killed - the idea being that this is somehow hypocritical. This is nonsense. I don't believe abortion is wrong in any way, but I'd never dream of telling someone who had mixed feelings about her abortion that she was a hypocrite for it*. Having complex, mixed, or even negative emotions about something does not make that thing immoral. Not to jump too far into moral philosophy**, but my view is that emotional responses are not - or at least should not be - an indicator of morality in any capacity. I suspect that more people agree with me on this than realize they do, and here is an example of why: Some people feel badly about killing an insect in their home, but most people do not consider this wrong. Even when it comes to humans, many - if not most - people would likely experience negative emotions when they kill out of genuine necessity, such as in self-defense, but very few people will argue that this is morally wrong, that you should just allow yourself to be harmed or killed if someone attacks you.

In this sense, it would be most logically consistent for me to view hunting wild animals in their own territory (as opposed to shit like when rich people transport animals to a personal hunting ground so they're guaranteed not to lose their prey) for food as morally superior to livestock farming, and I very much do. Traditional hunting is the method of killing for food most similar to that of other animals, as far as I understand. That said, I'm not remotely an expert on the topic beyond having hunted before as a kid and having a general understanding of animal behavior at the college level.

However, I will not pretend like I always behave consistently with the moral conclusions I come to. Like I've discussed before, I don't have an emotional response to violating my own morals. I simply didn't come wired with that feature. I don't really feel guilt or shame, so when I do something "bad," whether by my standards or others' standards, I either don't care at all or make a deliberate effort to cognitively "scold" myself, depending on the circumstances. I do consume meat that I have not personally hunted in the wild. While I do not think that livestock farming, especially modern livestock farming, is good in any way (ethically but also environmentally and health wise), because I don't have an emotional reaction to that thought (but do receive dopamine when I eat tasty food), I have so far been unable to convince myself to stop consuming meat.

I have said previously that I am glad that I am the way that I am, and that remains true; I do think my psychopathic traits are overwhelmingly more beneficial than not. This, however, is one example of the ways it actually is a negative to me - I really can't force myself to care about something I don't care about by default, and often have a hard time making conscious decisions that run counter to what produces dopamine. For this same reason, I have repeatedly failed to cut out gluten despite my doctor's insistence that I need to, and despite knowing how much better I feel (no daily migraines!) when I do abstain from it for a while. I tried to go vegan before and found that I latched onto very unhealthy junk food that was vegan by nature, like Oreos, and was eating incredibly badly. It does not help that I don't know how to cook, partly because my genetic disabilities make cooking a difficult endeavor for several reasons.

I am well aware that some people may be upset by this post, and may feel a need to label me a bad person for being this way. This is your prerogative, and I am certainly open to hearing your responses to this post, within reason. If all you want is to "punish" me for this, send me hate anons and insults, feel free, but I'll go ahead and let you know it doesn't do anything to me... not to mention I'm very used to it already as a radfem blogger. If you still want to do so because it makes you feel righteous or something, by all means go ahead, just be aware that it will not elicit a response from me in any way you'd desire, and definitely won't change my thought processes or behaviors. If you want to have an actual conversation, though, I'm more than happy to engage, answer questions, and hear your perspectives.

*I chose this specific example not because anti-choicers think abortion is killing, but because I have seen women be told that their sadness or grief about an abortion (which, btw, does NOT mean she regrets it!) is somehow "pro life" and that she can't talk about how she feels or else the right wing will use it against us. This is also nonsense, and fucked up nonsense at that. The right wing will use whatever they can; I'm in no way disagreeing with that. However, silencing women and girls to serve a narrative is not the answer. The lived experiences of women and girls (or any marginalized persons) cannot ever be devalued or concealed just because the enemy would use them against us. Actually, this is the same response I have given when told I should hide the fact that I didn't regret my mastectomy, or even that I should pretend that I did regret it. My story, my truth, is mine to own and discuss as I choose, whether it could be weaponized by ideological opponents or not. Same is true for all marginalized persons.

** If you are interested in moral philosophy, specifically where morals come from/what people base morals in, this page and the following pages (there's a Next button in the bottom right corner) sum it up pretty well on Page 1, then dive in a good bit more thoroughly with individual pages for each "root cause" of moral systems.

Side note: I will be reblogging this later because it's 6:30am EDT and a lot of my audience is in the USA. I worked hard and spent a lot of time on this, so I'd like it to actually be seen. Not much point trying to educate/inform/raise awareness if nobody sees it lmao

#mine#emotionality#morality#moral philosophy#moral systems#anchor system#personal#vegan discourse#long post#text post#psychopathy

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

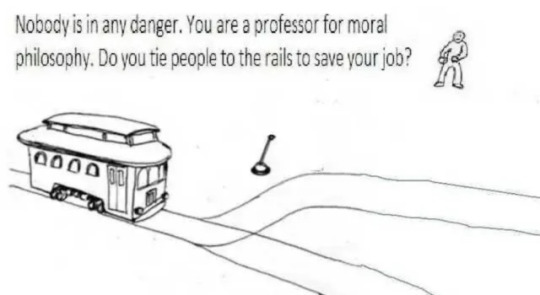

Yet another dumb Trolley Problem (fixed) :)

Plz read all the options before voting.

(Clarification: the green people are only the friends of that chooser, but are always there. For example, the three green people on the 2nd track are friends with only Chooser B; they are strangers to all of the other Choosers.

Also Clarification: All people in the image are always there. This means all the Choosers are always there. If you are, for example, Chooser C, then all of the other Choosers are still in their positions, and are strangers to you. Choosers cannot communicate with each other.)

#polls#trolley problem#moral philosophy#im being annoying again :)#posts taking place entirely up my own asshole

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh dip, the good place is about capitalism. The points system is money. The people with the most got them by being there first, and it's more about the circumstances of your birth than anything about you. And everyone these days seems to work forever and it's never enough. And maybe the system is broken.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

#trolley#the trolley problem#trolley problem#trolley problem memes#trolley problem meme#trainposting#philosophy memes#moral philosophy#light academia#chaotic academia

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Individualism and Collectivism

I saw a post promoting collectivism over individualism going around a while back, which inspired me to write a post about a philosophical issue I've been thinking about for a while. I was going to reblog a version of that post with some interesting commentary added, and add even more commentary to it, but it was getting incredibly long, so I thought it was best to make my own post, and just include a link -- here -- to the post with the relevant commentary, to which I will occasionally refer in the discussion below.

I got into a disagreement a few years ago with another academic philosopher about whether feminists must be individualists, in which I attempted (unsuccessfully, I'm afraid) to explain a distinction between what I have since started calling surface and fundamental individualism and collectivism:

Surface individualism or collectivism describes the emphasis of the cultural ethos that members of a society are taught.

Fundamental individualism or collectivism refers to where the fundamental locus of ethical value is taken to lie: the individual or the community.

Here's my overall thesis, fully explained and argued for under the "keep reading" link (which may be similar to what @reasonandempathy was trying to get at in the first reblog comment on the post linked above):

Surface collectivism is probably better than surface individualism because it promotes the well-being of more people; but fundamental individualism is necessary to justify the protection of individual rights to autonomy over one's life and body.

Neoliberal individualism is surface individualism. The culture emphasizes individual choice, individual action, makes individuals feel like they must always support themselves and rely on no one else, tells them that that is what constitutes real "freedom." This is the outlook that the other philosopher was (correctly) arguing is wrongly thought, by some white Western feminists, to be necessary to feminism; it is sometimes promoted by Western aid agencies that encourage women in the Global South to start their own businesses to achieve financial independence from (apparently) oppressive family and community structures. Surface collectivism would mean a culture that tells people to always think about their relationships with others, how they are embedded in a community, what they can accomplish by working with others. That sounds a lot better, especially to those of us who are well-acquainted with the pernicious, alienating consequences of surface individualism.

Fundamental collectivism says that only the collective matters in itself, or has intrinsic value, and any given individual has significance only a means to the survival and flourishing of the collective. It's ambiguous, but this seems to be the attitude being articulated in the tweet at the top of the linked post. And that is what @conservativemalarkey talks about in the third comment on that post as a justification for forcing anyone born with a uterus and ovaries to give birth: according to fundamental collectivism, that person's reproductive capacities are in the first instance a resource for the community to reproduce itself, and their individual preferences about what to do with their body do not matter. There is no individual right to bodily autonomy; there is only the duty to perpetuate the community. To put it in the terms that @nothorses brought up: the collective has rights but no obligations/duties to its individuals; individuals have obligations to the collective, but no rights that it is required to respect.

That's why I have come to believe (and was attempting to argue with the other philosopher) that fundamental (not surface) collectivism is incompatible with feminism: it provides no grounds to protect individuals' rights to bodily autonomy. That, of course, harms everyone; historically, communities have often forced men and boys to risk their lives going to war to defend the community, or to add to its wealth and territory. But it especially notably harms those who are assumed to have the capacity to gestate and bear children (gendered by cisnormative society as women and girls, giving rise to sexism and misogyny that affect anyone associated with that category), because that capacity is, so to speak, the "limiting reagent" for reproduction in the community: it is a scarce resource, far more limited in the lifespan, costly in time and energy, and dangerous to the life and health of the possessor than the capacity to fertilize. For that reason, patriarchal societies (incredibly widespread historically and geographically) effectively regard the reproductive capacities of potential child-bearers as community property, or as a commodity regulated by the community. A (presumed) woman*'s value, and the purpose of her life, consists in her ability to reproduce within the socially approved constraints; women's sexual activities are everyone's business; everyone feels entitled to comment on the bodies of women of reproductive age, especially when pregnant, and how they raise their children.

[[*Meant to encompass anyone perceived as a woman, which in most contexts, historically, also means being assumed to have childbearing capacities; includes AFAB people who do not identify as women as well as trans women who pass as cis. The general attitude also, of course, affects trans women who don't pass as cis but are understood to be communicating a self-identification as a woman.]]

Can a community be said to flourish if a large number of the individuals in it are miserable? Structurally, yes: it can successfully perpetuate itself, grow, become wealthy, while all its individuals dutifully sacrifice themselves to it. Ironically, for a society based so heavily on surface individualism, modern capitalism looks a lot like that: individuals are expected to sacrifice themselves for The Economy, which grows and maintains itself like an organism without regard for whether the vast majority of the individual 'cells' that make up its organs and tissues are satisfied with their lives. This is also true of patriarchal cultures in which at least half of the population is limited in the way they can live their lives, and are taught to see this as natural and inevitable.

Fundamental individualism, by contrast, says that the locus of value is the individual: what matters is the well-being of individual human (or sentient) beings, and communities are valuable only insofar as they contribute to the well-being of their individual members. Fundamental individualism is perfectly compatible with surface collectivism, and it is very probably true that most individuals will be happiest if they live in communities that emphasize their communal ties and encourage them to think of themselves as enmeshed in and dependent on a community. BUT fundamental individualism will say that this kind of culture is good because it is what is best for the greatest number of individuals.

According to fundamental individualism, the collective, qua collective, has no value independent of the individuals in it. Individuals have rights to autonomy and to have basic needs met which the community must respect. Do individuals have obligations to the collective? Yes, but only as a surface shorthand for their obligations to all the other individuals that make it up. Communities, cultures, collective forms of life have no intrinsic value, because they are not independently sentient: they cannot feel pain, pleasure, desire, or satisfaction. The loss of communities and cultures is terrible because of the harm that it causes to the individuals who lose their sense of connection, identity, and purpose. But if a way of life systematically fails to promote the well-being of a great many of its members, and/or systematically violates their rights in a way that cannot be remedied without ending that way of life, then it deserves to be ended. Again, most of us here have no trouble saying that about modern capitalist society, but it's equally true of any form of social organization.

Are people (outside of academic philosophy) generally familiar with Ursula K. Le Guin's story "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas"? Here's the text, available from libcom.org (short for "libertarian communism," apparently). Spoiler alert: episode 1.06 of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, "Lift Us Where Suffering Cannot Reach," is very obviously based on it. That is one of the starkest, most evocative illustrations of collectivism that is not balanced by consideration of the rights and well-being of individuals: one individual is forced to live in unending misery so that the rest of the community can be happy.

"But that's not real collectivism!" someone will protest. "Real collectivism means everyone takes care of each other! They would have compassion for every member of the community and never allow that to happen to one of them!" Well, it depends on what you mean by "real." Many forms of surface collectivism could mount an argument against that arrangement, on the grounds that a healthy community must care for all its members, even (or especially!) the humblest and most vulnerable. From the perspective of either surface or fundamental collectivism, it might be argued that permitting any member of the community to suffer in this way would damage the cohesion of the community by encouraging callousness regarding the suffering of (certain) other members.

But nothing about fundamental collectivism says that a community must care for all its individual members in order to flourish; on the contrary, it says that individuals do not matter for their own sake, but only for what they can contribute to the community. Fundamental collectivism can only offer an indirect, instrumental argument that allowing the Omelas situation would harm the community because of how it would affect the community ethos. In Le Guin's story, all members of the community do know about the condition of their society's thriving; that's how some of them decide that they should walk away. But in the SNW episode, most people do not understand what their happiness rests on; they can blissfully believe that the community does care for all its members, so fundamental collectivism could not find anything wrong with the arrangement.

Crucially, fundamental collectivism cannot capture the real reason most of us will think the Omelas situation is horrifying: that it violates the rights of an individual who does not choose to sacrifice their well-being for the sake of the community, but is forced to suffer so that the community can thrive. If you're thinking it would be OK if, and only if, the individual did choose to be the sacrifice for the community: that's something that might be promoted, even glorified, by surface collectivism, which would encourage people to see their individual happiness as less important than the well-being of the community. But fundamental collectivism could not account for the profound ethical difference between a chosen and a forced sacrifice: the importance of individual autonomy; the principle that no one should be able to make such a momentous choice about the course of an individual's life except that individual.

Mind you, this does not mean that a fundamentally individualistic ethics will necessarily rule the Omelas situation impermissible. There are some forms of fundamental individualism that could justify it -- notably, utilitarianism, which would say that the suffering of one individual, however appalling, is far outweighed by the perfect happiness of thousands or millions of other individuals. Fundamental individualism is not sufficient to rule it out; and you might not think it should be ruled out, considering the numbers involved. But fundamental individualism is necessary to even say what the problem is. The only objection that fundamental collectivism could offer doesn't even locate the problem in the terrible forced suffering of the individual, but in the way that knowing about it might affect the cohesion of the rest of the community.

So while I'm generally in favor of a surface-collectivist ethos, I'm convinced that any fundamentally collectivist ethical theory has profoundly immoral consequences. The ultimate locus of ethical value must be the individual. It's fine for a culture to encourage individuals to prioritize the community over themselves, but there is something genuinely wrong with the community forcing sacrifices on its members, and that can only be accounted for with reference to irreducible individual rights.

#individualism vs collectivism#individualism#collectivism#ethics#moral philosophy#philosophy#the ones who walk away from omelas#snw spoilers#snw 1.06#snw 1x06#lift us where suffering cannot reach

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to christian theology the smallest sin already makes us deserve Hell, but through accepting Jesus' sacrifice we can be forgiven

But here's the thing, if you seek to avoid the punishment you know you deserve, isn't that a bad thing too?

Of course, the whole point is that God is forgiving you, and there's nothing wrong with forgiveness, heck, there's nothing wrong with *asking* to be forgiven, but once "forgiveness" is conditional, the situation is different

If the forgiveness is conditional then the judge is leaving the forgiveness up to the guilty person in a way, since it's up to them to fulfill the condition

When you see it like that, the judge is basically offering you a "get out of jail free" card, and leaving the decision of taking it up to you

And here's the thing, if you know you are guilty, and you truly repent of your sins, you wouldn't take that card, because you would believe that you should be punished

If the judge decided not to punish you that's fine, because the decision is up to the judge, but in this case by accepting Jesus' sacrifice you are deciding that you shouldn't be punished, even though you should, and that decision to avoid the punishment you deserve is wrong

To summarize, if Christian theology stated that God is willing to forgive anyone who repents of their sins, that would be fine, because forgiveness would always be up to God, but by saying that forgiveness also requires faith in Jesus specifically, then that decision is up to you

This lead to the conclusion that if Christians want to be consistent, they would reject Jesus' sacrifice and accept they will be punished eternally for their sins, and they shouldn't want it any other way

Finally, you could argue that by repenting someone is already deciding by themselves to be forgiven but I disagree. Repenting only means you recognize what you did was wrong, it depends on your moral compass, and it's independent of your desire for forgiveness. In fact, part of repenting should include the acceptance of the punishment you deserve

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consistency is contrary to nature, contrary to life. The only completely consistent people are the dead.

Aldous Huxley, Do what you will: Twelve essays.

#philosophy tumblr#philoblr#englishphilosophy#english writers#philosopher#thinker#esotericism#anarchism#moral philosophy#metaethical#existentialism#dark academia#life quotes

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consider this version of the Trolley Problem.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the Most Harmful Ideas I've seen is That Plurals Shouldn't Help Each Other

A person is tied to train tracks. They're trying to untie themselves. You happen to be walking by.

You have a saw.

What do you do?

Do you help or walk on?

If you help, you could end up cutting their leg. Maybe those ropes are tougher than they look? What if you try and you fail anyway? You can't free them before the train hits and now it's your responsibility.

...

Or how about an even more blatant trolley problem. A train is barreling down the tracks towards a person tied to the tracks. You have a lever.

If you do nothing, a coin flips. If it land on heads, the track changes directions. The person lives. It lands on tails, the person dies. If you do nothing, there's a 50% chance this person is going to die.

If you pull the lever, a D6 will roll instead of a coin. Now, if it lands on 1, the tracks stay the same. The person gets ran over. But if it lands on 2-6, the tracks change and they live.

Logically, by taking an action, you drastically increase the odds of survival.

But if it lands on 1, you might have to wonder if you failed. If this was the wrong move and if it did more harm than good to try. Maybe, you'll wonder, if the coin flip would have been better. If the coin would have landed on heads. And that's valid. But it shouldn't hold you back.

...

Perhaps another analogy could be coming across a family of cavemen who are freezing. You know how to build fire but they don't. If they don't know, there's a good possibility that they could freeze to death in the night. But if you do, maybe they'd misuse it. Maybe they'd start a forest fire. Can you risk it? Do you teach them how to make fire for themselves or refuse because you're afraid of all the ways it could go wrong?

...

I think there has been a lot of fearmongering in the community about the concept of plurals helping other plurals.

This came up recently over the topic of switching guides.

But I've also seen it before with the demonization of the Plural Association's planned warmline for plurals. (This also was paired with a conflation of Warmlines and crisis Hotlines. Note that these are not the same.)

The argument you see against plurals helping plurals usually boils down to, "what if something goes wrong? What if you accidentally give someone bad advice?" And while these are concerns you should try your best to mitigate, one should also ask "what if I don't help? What if I do nothing, because I'm afraid of how it could go wrong?"

I am not saying that there are no risks. Of course there are. But sometimes those risks are worth taking.

We need more plural support and resources in the world, and even though the warmline is taking much longer to get off the ground than expected, I do want to send a shoutout to everyone who was willing to volunteer to make it a reality, and I hope you can serve as an inspiration to others! 💖

#syscourse#plural#plurality#endogenic#multiplicity#systems#system#plural system#endogenic system#pro endo#pro endogenic#moral philosophy#trolley problem#philosophy#system stuff#sysblr#tpa#the plural association#actually plural#actually a system

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

– Professor Christine Korsgaard's book Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals is a departure from her previous theoretical work on moral philosophy, as it deals with more practical ethical questions.

Korsgaard, Ph.D. ’81, has taught at Harvard for almost 30 years and is an expert on moral philosophy.

Drawing on the work of Immanuel Kant and Aristotle, she argues that humans have a duty to value our fellow creatures not as tools, but as sentient beings capable of consciousness and able to have lives that are good or bad for them.

#animal rights#harvard#christine korsgaard#moral philosophy#veganism#animal liberation#vegan#books#fellow creatures

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meta: Did Harry do anything wrong?

This meta was inspired by a conversation in @thethreebroomsticksficfest server. Tl;dr at the end.

It depends on how you define wrong vs. right. This is essentially a question for ethics – according to the main theories of ethics, utilitarianism, deontology, and virtue ethics – I want to do a little exploration of Harry’s moral decision-making. The ethical theories I present to you are told in very broad strokes – contemporary moral philosophical thought is a lot more nuanced. If you want me to go in depth with any of these, drop an ask in my ask box.

Utilitarianism: greatest good for greatest number of people, and/or consequences outweigh the method. E.g. ends justify the means. Was Harry’s use of the Cruciatus Curse against Carrow in Deathly Hallows justified? Could go one of a few ways: yes, because it was in defense of McGonagall; no, because torturing Carrow was not an appropriate defense of McG; maybe, it’s possible Carrow wouldn’t have responded to any other kind of deterrent. Utilitarianism falls short when we start justifying things to the extreme – it’s how Truman justified the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan. His greatest good was ending the war soon, but the cost of so many innocent human lives (in this philosopher’s opinion) was unjustified. This leads us to deontological ethics.

Deontology: duty-based ethics, and/or there’s a set of rights and wrongs, and it’s never OK to commit a wrong even if the outcome is good. E.g. there are certain rules, whether written in law or not, that shouldn’t be broken. Let’s use the example of Harry using the Cruciatus Curse again. In his world, it’s considered an Unforgivable. That doesn’t necessarily imply that’s a just or right framework – law and moral goodness don’t always overlap. Does Harry think it’s always unforgivable? This is where deontological ethics gets tricky – our sense of what is universally right or wrong may not be universal, or may be biased because of the society we come from. As most people would say that torturing someone is morally wrong, even if that someone is guilty of committing all sorts of atrocities, then Harry would not be justified in using the Cruciatus Curse. Deontology has its limits when we start squabbling about moral absolutes and moral relativism, or when we start seeing poor outcomes for supposedly good actions.

Virtue ethics: we cultivate morally good behavior by developing virtuous traits. The more virtuous we become, the better our moral actions will be. An action is morally good if completed by a virtuous person. We judge an action based on the person who is taking it. While this may seem counterintuitive in some ways, think about it as a way of understanding intentions. Is Harry justified in his use of the Cruciatus Curse? It depends. Is he a morally good actor? Does a morally good actor use the Cruciatus Curse? Most of us would say no to this – intentionally hurting another person is not a sign of virtue. While virtue ethics may seem murky (it can be), a good way of thinking about it is to ask yourself “would a morally good person, or an [insert virtuous trait here] person do X?” If the answer is yes, then it’s morally good. If no, then don’t do it.

As for what I think Harry did wrong in the series, in terms of moral failures, there are a few caveats before I list these things. First, Harry is a FICTIONAL character. FICTIONAL characters are not accountable to the same morality as we are; they are vehicles to tell a story, reveal something about humanity, or entertainment. FICTIONAL Harry didn’t do anything wrong because FIGMENTS OF IMAGINATION cannot do anything wrong. If Harry were real, however, these are a few of the things that I would consider morally bad or questionable:

Use of Sectumsempra in HBP. He didn’t know what the spell did, only that it was used for enemies. He may not have known what it did, but ‘enemies’ should’ve been context enough to know that it wasn’t friendly.

Snape’s worst memory: gives us, the reader, and Harry, a ton of information about James. However, there was no moral reason to violate Snape’s privacy.

Spying on Draco in HBP: when Harry takes the Invisibility Cloak and spies on Malfoy, or when he asks Kreacher to spy on Draco. Good cause, perhaps (utilitarianism) but not necessarily right (deontology). Keeping an eye out for your neighbor and being vigilant can be good, but in this case it was not Harry’s responsibility to do so. (But remember, Harry is fictional, and in his world, adults aren’t fully competent or forthright.)

Brewing/taking Polyjuice Potion in second year. For plot = good. For deception, spying, and agreeing to Hermione stealing = bad.

Sneaking out to Hogsmeade, third year. For plot = good. For rule breaking and recklessly endangering his life (even if he didn’t know that wasn’t true) = bad.

Torturing Carrow = bad. Torture isn’t ok, Harry.

Mostly, Harry makes a lot of morally good or morally neutral decisions throughout the series. Like most people, fictional or real, Harry is not wholly morally good, and the theories above, broadly speaking, can only take us so far. Let me bring in an example of Harry leading Dumbledore’s Army in terms of its moral goodness (or badness).

Utilitarianism: Was the D.A. the greatest good for the greatest number of people? You can argue it was, because the students learned and practiced lifesaving spells that would help them in their later years. They broke school rules, but they learned to defend themselves, and others. Thus, the D.A. was a moral good.

Deontology: Was the D.A. the right thing to do? In a strict sense, no, because Harry broke the school rules. He intentionally put himself and others in detention. However, is there a greater duty to his classmates that supersedes the rules? You can argue yes, Harry had a duty, an explicit moral imperative to help his classmates. Did it have to be through the D.A.? Maybe not. In this case, the D.A. is morally questionable or perhaps morally neutral.

Virtue ethics: Is the D.A. something that a virtuous person would do? This depends a lot on your definition of virtue, and which virtue you’re referring to! Let’s take courage as a virtue. Is it courageous of Harry to lead the D.A.? I think so! Is it prudent? Maybe. This is why virtue ethics can be murky – which virtue is most important? How do virtues compare across communities? In the world of HP, I’d say the D.A. was virtuous and morally good because of the values they placed on courage, excellence, and developing skills.

Tl;dr: Harry does make morally questionable or morally bad decisions, but as he’s a fictional character, we need to be careful in judging his behavior with real-world moral theories.

#harry potter#harry james potter#philosophy#moral philosophy#ethics#utilitarianism#deontology#virtue ethics#hp meta#writing meta#harry potter meta

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little homage to two of my all time favourite TV series

They'd make such a great crossover

No kidding - these two shows just may be some of the most important introductions of a whole generation to Philosophy, even if we don't realise it.

In the case of The Good Place it's much more explicit, because the plot revolves around ethical philosophy and there are even ethics classes in the show itself. But Good Omens also provides a very strong introduction to Philosophy and ethics by forcing the audience to think and reflect on difficult moral dilemmas without a clear "right answer".

I honestly believe there are people out there who developed a deeper interest for philosophy thanks to these two shows and I love The Good Place and Good Omens for it.

What's even better - despite both shows not shying away from delicate, uncomfortable questions, they manage to be consistently funny and enjoyable through and through.

"- someone: hey The Good Place and Good Omens. We have a question for you. As major comedy TV shows do you prefer to showcase deep philosophical questions or do you prefer to be enjoyable?

- The Good Place and Good Omens: yes. "

✨

#The Good Place#good omens#neil gaiman#moral philosophy#philosophy in tv#meme#I love good omens and the good place

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

A incredibly weird problem I see in a good portion of fantasy stories these days is something Ive been calling "Inferna delenda est", and which my less pretentious friends (all of them) call "the hell problem". Its sort of something that, because its a genre convention, is almost always ignored, but once you see it, it cant be unseen.

I admittedly only started seeing this after reading UNSONG, which is literally About this problem. But now that its been pointed out, I cant unsee it elsewhere, and any media which runs into it but doesnt address it becomes almost entirely ruined for me.

The issue of Inferna delenda est is present in any setting which 1. Has real, proven afterlifes where most people literally go when they die and 2. Has one of those afterlifes be at all comparable to Hell, i.e. any place where a significant number of sapient creatures are tortured for all eternity.

If those two criteria are met, almost any plot becomes pointless and trivial. What does it matter that a hero saves a city from destruction when beneath their feet millions of people are burning, and many of those saved will join them? Who cares whether the ruler of a country is corrupt or not? The evil that would be stopped by replacing them with even a perfectly competent and benevolent ruler is staggeringly inconsequential compared to that of an eternity of torment.

Like, im not being vague or making an analogy here. Im just saying that its incredibly difficult to care about a plot to stop a war or kill an evil wizard when the story offhandedly mentions the fact that millions of people are 100% being tortured for eternity in a real place and no one is doing anything about it.

And even further, it makes it Really hard to view the heroes as...actual heroes. The degree of callousness required to keep the existance of hell in the background (from an in-universe perspective) is just ridiculous. Like, if youve got your high fantasy hero saving an entire continent from an evil demigod or whatever, the fact that theyre Not constantly thinking about hell is just... if you have that kinda power, and you literally know for a fact that Hell is a place, then you should be fucked up about it!

Like I can understand that growing up in that setting youd be resigned to it, not much a random soldier or whatever can do about it. But once they become super powerful? And they never even Mention Hell? That much callousness automatically moves you down a few notches from hero.

Obviously in a lot of settings hell just sorta Exists, and soul sorting is vague, but even then like. Break into Hell! Rescue people or at least relieve their pain! Its just so insane that the worst thing literally imaginable as a physical place (maximum pain that lasts literally forever with no hope of relief) is a staple of lots of fantasy settings and so many authors just do not in any way address that.

And like I said, its not that theyre writing Poorly because of this. Its a genre staple, and if you dont give it too much thought it doesnt seem to be an issue, especially given [gestures vaguely in the direction of christianity and its popularization of the concept of hell]. But god now that its been pointed out it drives me Nuts.

Anyways idk where i was going with this. Read unsong, i guess?

#Ceterum censeo Infernum esse delendam#writing#rambling#moral philosophy#unsong#?#ignore this its just been bouncing around my head for a while and the group chat is tired of hearing me end every book review with#inferna delenda est#tracking

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: and that's why they call themselves “girltwinks."

Mao Zedong: Incredible. The ingenuity and power of the masses of proletarian women is boundless and without equal.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's the idea behind coercion not being ipso facto bad? how does this apply to the abolish schools discourse?

first off have to bracket this by saying i've never discussed coercion at length, because it doesn't tend to be used particularly formally, and because i'm allergic to the cats in the narko squat. but, to the point: there's no big idea behind it. that's just it—if you want to claim something is ipso facto bad, you have to do the moral legwork there; you have to own the edge cases. when you don't do this, you really mean something like 'X phenomenon in many cases causes Y phenomenon, where i find Y bad'. in the case of coercion, people don't tend to explain why it's bad very seriously, because it doesn't actually make any sense to claim that something ipso facto bad becomes un-bad when it's, like, legitimated through some procedure, and attempting to redraw the lines such that it’s only coercion when not legitimated in this fashion stretches credulity. but on the other hand nearly all of us are comfortable with *some* uses; we just try to bracket them in a way which makes them appear non-problematic.

a clearer example of what i’m talking about with more straightforward ramifications would be domination, because we can pick out a more definitive account to consider. we can basically read it as the capacity to affect the choice set of another party; at first blush this makes sense & leads us towards an account of freedom. the trouble is that i’m always in-principle in the position to affect the choice set of a third party, because even something as basic as a market transaction affects something like supply or price in a fashion that renders the choice fundamentally different. the ability to buy something at a dollar and the ability to buy something at a dollar and a penny are different choices, as is the ability to access a good for which one has to queue at t=1 or t=2. but, we don’t even have the conceptual capacity to talk about what it would mean for agents to only make ramification-less choices in this way. it’s ultimately purely specious. the classic example in the literature is that refusing to let a neighbour without a pool use your pool at odd hours of the day is dominating them, but if anything this undersells how badly domination overgeneralises.

i understand coercion and domination aren’t precisely the same, but they’ve been read together by domination theorists to the point where you can appreciate how applying force to change the calculus of the choices before someone is once again a species of this sort of power-over.

the overall way in which to situate my lack of care for concepts of coercion etc., though, comes in the fact i don’t think personal identity or metaphysical conceptions of the subject hold water, & so i find most conceits of autonomy & so on fall apart in much the same way. i’m not a rights-thinker, or a contract-thinker, or a duty-thinker, or other species of liberal.

it’s a neat question how that squares with the abolition of schools, because i do have the sort of gut moral sentiments that seem to comport with this philosophical position fairly awkwardly, though. another example that came to mind recently was my profound distaste for the whole voluntary-death moral panic. ultimately i do think it’s possible to square the circle, but it requires a deeper ethical sketch than i have space for here. to take a very quick stab: when we don’t find ourselves possessed of the idea that moral facts are out there to be discovered by clever metaphysicians, we’re forced to, well, ask questions, and make our peace with using language to do so. in other words, we listen! this is something that perfectionisms, whether of the hedonistic-utilitarian or aristotelian bent, do not.

my scepticism towards schools, aside from sheer horror at the idea of telling someone how i want to dispose of the next ten years of their life, is a scepticism towards knowing what kind of person you ought to develop into. i can help you develop into the kind of person that would bring you satisfaction, and i can tell you the requirements of those rules, but i would never presume to you know your good. because ultimately the aggregate social good i’m looking for comprise, along with everyone else’s, your evaluation of your life as a whole anyway!

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Say it with me, kids: human beings are fundamentally a mix of good and evil.*

This has been the case at all times and in all places, as you can see throughout recorded history and oral traditions, which all contain stories of violence and cruelty as well as kindness and generosity. These tendencies occur in different proportions in different individuals. But the world is not divided into a majority of inherently-all-good people and a minority of inherently-all-evil people who could ideally be weeded out, and the worldview that says it is is incredibly dangerous for reasons that should be glaringly obvious.

* Good currently being understood to mean altruistic, cooperative, peaceable, and evil to mean selfish, violent, exploitative. This has not always been the most important value axis in all societies. There have historically been a lot of warrior cultures, in every part of the world.

#a lot of people are liking but not reblogging this#makes me curious about why#afraid of backlash?#or just doesn't fit the tone of your blog?#moral philosophy#human nature#neo-rousseauianism

64 notes

·

View notes