#less formal questions and more like a transcribed recording

Text

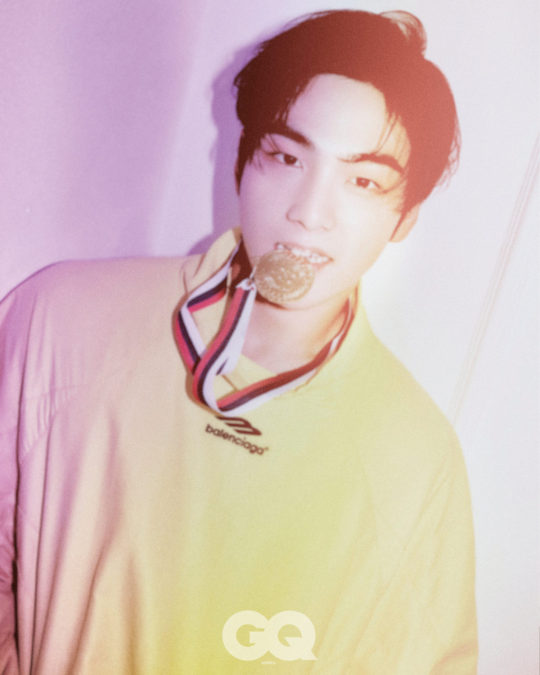

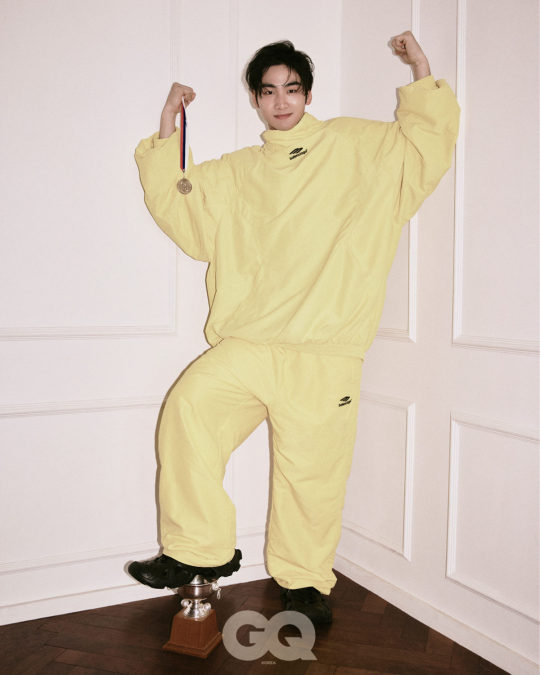

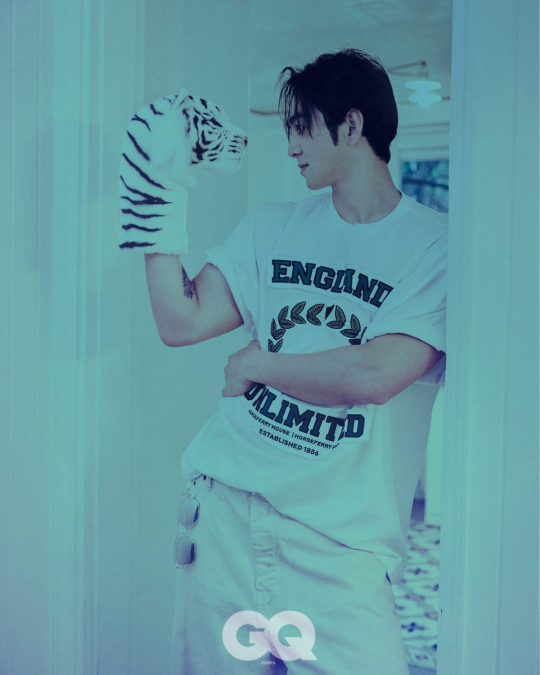

Baekho: "Out of about a hundred swings, there are about two that I like" [GQ Golf - September 28, 2022]

[source]

Firmly and clear in the distance. When Baekho swings.

GQ: Let's be honest. How many drivers have you broken?

BH: Hahahahaha, one. Just one broke.

GQ: When you were doing that tee shot and I heard that loud sound and watched the driver break into pieces, I thought I was going to meet a power golfer.

BH: So you've seen that video. Actually, people who swing well probably don't break their clubs, right? I'm bad at swinging so it broke, hahahaha. I felt a little bad then (when the club broke) but out of everyone I was with, my ball went the farthest. It didn't even hit the ground so I don't know why it broke. The driver must have been pretty worn out.

GQ: How long has it been since you started getting into golf?

BH: It's been over a year now. I started taking it seriously since summer of last year.

GQ: You mentioned in the sports variety show Sooro's Rovers (2019) that you weren't really a soccer fan. How did you come to like golf, which has a ball much smaller than a soccer ball?

BH: Just naturally. Since everyone I knew who played golf said it was really fun, I wanted to try it. I didn't know it would be this much fun of a sport. I thought, wow, this crazy tiny ball doesn't follow me at all. When I want to push it just a bit farther, it ends up going somewhere weird... With soccer, actually if someone asks me to play, I have average skills just enough to do it. Even though I like it, I don't spend time practicing to be better. Golf's different. "Oh, I really want to be better. I really want to play better." So I ended up practicing and spending my time on it, though I think it's obvious that I've gone a bit too far. It's a sport that has kind of taken over me.

GQ: People who enjoy golf all say the same thing. When it doesn't go my way, I somehow end up loving it more. Have you reached this spiritual enlightenment?

BH: It really just goes where it feels like going. And at 80, I swing about a hundred times, but only two shots come out well. I can't forget those two shots so I go for another round. Also, it's hard to look for a place to golf in Seoul, right? There are a lot of times when I had to get in my car and go somewhere far, so while driving, I get to enjoy my time with good people and eat something delicious when we're done. I love everything about that feeling. All the things I love are part of golf.

GQ: I'm curious about your opening playlist when you go on a trip. What songs do you listen to on your way to the golf course?

BH: I don't listen to songs on the way. I usually love listening to music while driving. But when I go to play golf, I don't listen to music.

GQ: That look in your eye is such a huge change. It's totally different from what you said earlier about not being too greedy or going too far.

BH: Hahaha, no, it's... I want to go there with a serious, reverent mind. You feel like going back to nature when you're in the city, right? So I want to get rid of all that man-made stuff.

GQ: Ah, to face it quietly.

BH: Yes, quietly. But I don't want to be too crazy about golf. Because I want to do it for a long time. I don't want to lose my excitement for it right away. I don't want to be too into it. I just want it to be a healthy hobby. I'm a singer, not a golf player.

GQ: Sounds good. So let's dive into more of Baekho's healthy hobby. What's your "Lifetime Best Score"?

BH: I swung a 79 once. But the next day, I hit a 100 so the 79 seemed ridiculous.

GQ: What's your average record?

BH: It foes back and forth between 80 in the latter half and 90 in the first half.

GQ: Your style of aiming seems like it's for power golf?

BH: I'm not sure about that. Because now, the thing I hear the most is "lessen your strength." It only goes where I want it to go if I ease up; it will go farther if I ease up. It seems like somehow my strength is getting in the way. I thought that no matter what, strong people will only swing far if they ease up on their strength... Anyway, I haven't been worried about my driving distance. The ball following an accurate path is my main worry.

GQ: What about the opposing forces from nearby disturbances?

BH: I'm an RC car. For example, if someone says "This ball is going to slice," it happens that way, like a remote control was telling it what to do. The people I play with can basically control me with their words.

GQ: Why do you say that so brightly?

BH: It's just funny. Golf is having fun and being comfortable with good people. I love that kind of atmosphere. Rather than having a competitive and strict game, the ball can get kind of dangerous so we try to swing safely. We tease each other and cheer each other on, that kind of thing.

GQ: Was there a particularly memorable golf day?

BH: Yes, there was. My friend's mom had just started playing golf. Since we played it and enjoyed it a lot, they asked their mom to learn, and she really did. That was the first time my friend went on a trip with their mom to play golf. I was with them when Mom stepped on the field for the first time. Moments like that are great.

GQ: Do you call your friend's mom "Mom" too?

BH: Ah! My mom is close with my friends. I'm also close with my friends' parents. My friends call my mom "Mom." I thought that was pretty nice so I followed suit.

GQ: That's great. Friends, parents, and everyone getting along and spending time together like that.

BH: It is really great. We can all do it together regardless of age, so it's really amazing.

GQ: If we use golf as a metaphor, we prepare for a new tee shot at a new hole, right? Like how you've prepared for your solo activities simply as Baekho, not as NU'EST Baekho.

BH: Hm? No, I think it's better to call it my second shot.

GQ: Really?

BH: Since the tee shot went well, the fairway is in a good spot so it feels like the second shot is going to go well, too.

GQ: So it's not like the hole is over, but the tee shot succeeded through the name "NU'EST."

BH: Right. So it feels like I'm in a good place to make the second shot. It really does. It really feels like I'm having a new start, because it's a new shot. I'm nervous and excited and anxious and worried. But somehow I feel kind of assured in my heart too. I was so happy when I promoted as NU'EST. Because of NU'EST, I've come to a good place. From this place, I can go anywhere I want to go next.

GQ: The solo album that's coming out in October seems to be the direction in which you're going. Are you also participating in all aspects of this album - writing, composing, producing?

BH: Yes. I'm working hard preparing for it. I recorded the title track yesterday, and I really like it.

GQ: Was the song you sang at your fan meeting a hint about your new album? "I, who felt change, have changed" [t/n: literal translation]

BH: Yes, that was a hint. Strictly speaking, it's one of the finished new songs. The fan meeting was decided while we were working on the album, so I wanted to reveal one of the new songs in advance at the fan meeting.

GQ: The NU'EST albums you've produced for about three years have been described as "silk." This song is like a pair of jeans that have softened after a rough washing and sanding. [t/n: i'm sorry WHO described it this way??] Though it's more natural and rough, it still has a soft strength to it.

BH: Really? That was intentional. When I was singing NU'EST songs, I had a lot of high-pitched vocals, but while I was working on this album, my intention was "Let's try to find power without high vocals." What kind of strength can I show effortlessly? I did a lot of research on that.

GQ: This solo album is like another piece of you. If you could express it through a color, what color would it be?

BH: Um... I hope it can be clear. Though the process of working on it and the way I approached it was different, it's really all just me. Then and now, I'm still the same person. So that's why I just want its color to be clear. [t/n: clear as in 'transparent'; not clear as in 'vibrant']

GQ: Just the way it is.

BH: Right.

GQ: You said that when you go for a round, you don't listen to music and face it with silence. What about the drive back?

BH: That's when I have to monitor the time. There are a lot of people like us who work at night and sleep during the day, right? So we go for a round in the morning, and in the afternoon, we have to face all the work we put off.

GQ: So you're considering that as well. You're not tired after golf?

BH: No, not at all. It's great. I feel refreshed.

GQ: What are the values you stand for while playing golf?

BH: I don't accept mulligans from my friends. (*mulligan: when a bad swing is invalidated and the player can swing again)

GQ: Why?

BH: I just hit it. I hit it just the way it is. Whether I hit it well or I hit it terribly, it's still my ball.

[this is a fan translation by a non-native korean speaker and may contain inaccuracies. it has not yet been proofread or edited.]

#i'm so sorry if i got a lot of golf terms wrong#i know nothing about golf and had to look up a lot of stuff lol#but that golf metaphor about the second shot though :(((((#i really wanted to translate this interview because i think i've only had one other baekho post on this blog so far#also THESE PICTURES??? UGH#maybe i'm just going through a heavy baekho phase but all his posts since he started promoting for his album LORD HELP ME#i just also want to say the spacing in the original article is so wack#idk if it's a stylistic choice because the interview seemed more casual#less formal questions and more like a transcribed recording#but man the spacing was part of why this took so long#baekho#kang dongho#nu'est#백호#강동호#뉴이스트#translation#shanibugi trans

1 note

·

View note

Text

post-traumatic synthesized dreamscape no. 1

youtube

this digital sound composition is an attempt to transcribe (record, mollify, exorcise) my emotions looking back on the events of last february as i experienced them.

i was living in st. petersburg as a graduate student researcher, one of the dwindling ragtag lot of americans with no family ties to russia still trying to live there, when the russian military invaded ukraine early in the morning the day after february 23rd, the federal holiday honoring military men that was once red army day. i had already given up on my dream of living in russia for anything approaching the long term and was trying to stay for just as long as i safely could as History unfolded around me. i left russia 24 hours after the start of the invasion and made it back to the u.s. safe but mentally shattered. I’d spent months navigating or avoiding tense encounters with russian migration police as weekly updates to civil law gradually made it very nearly impossible to legally reside in russia as citizen of a designated “enemy nation;” and then finally found myself alone in a windowless room with an fsb agent in the remote checkpoint by the finnish border that terrible morning. my battered psyche imploded before the questioning, which was, objectively, very mild, even began.

back in the u.s., i spent months struggling to operate my own person before i realized that i had ptsd from a war to which i had barely been a distant bystander. i started therapy and saw massive improvement after just a few months. good fortune, which saw me safely through so many close calls and near-disasters during the grinding buildup and violent lurch into fully-fledged military rule in russia, blessed me yet again.

before entering formal therapy, i leaned very heavily on intoxicating substances (alcohol in russia, marijuana in the u.s.) and movies to keep the terror at bay. my understanding of myself in this phase of my life is heavily mediated by cinema, especially cinema made or set in the wwii and early “post-war” era. this time when society’s psychic wounds were only just scabbing over and could be seen on nearly everyone who crossed a camera feels less like the past and more like a parallel present still playing out in ever-more garbled reproductions in the nightmare fantasies that govern life in the places that never healed properly from the traumas of the ‘40s. to make beautiful or joyful art has become impossible, but the need to externalize our disordered response to trauma in art is stronger than ever. our voices can no longer carry a tune, but we have all history’s old recordings to grind and reshape into new kinds of music that may somehow express the emotions no amount of time and treatment can resolve.

some notes on the recordings i used as material for this piece

during this last year of trauma recovery, i saw myself most vividly in one particular cinematic incantation of postwar psychosis co-created by a brit and an american both too young to have experienced wwii but raised in its fallout as men in societies where the publicly synthesized idea of maleness is overwhelmingly suffused with the radioactive particles still emitting from the atoms of that war. watching mickey rourke’s performance in alan parker’s metaphysically-canted neo-noir “angel heart” (1987) somehow made a narrative out of the glossolalia of confusion and pain humming at the core of my being during the strung-out spring that followed the terrible winter of ’21-’22.

in the autumn before that winter, i had found strength and solace from the encroaching fascist terror in russia in the exploration and nurturing of my own masculinity. i had long identified more with a masculine perspective than a female one, but various factors limited the extent to which i expressed this identification. various other factors led to me reaching new levels of masculine identification and expression that fall, and this was a positive, self-actualizing experience that nurtured me during the months in which i lived under increasingly dire threat of repression from a government officially opposed to the existence of queers, americans, and gender studies researchers within its borders.

months of trudging alone through seedy hotels, anxious crowds, and icy boulevards, all while looking over my shoulder for police, were bearable if i saw myself as a sort of postmodern pastiche of film noir protagonists, a hardboiled detective working an increasingly dangerous case, an existentially bedraggled man in the wrong time, space, and body muttering clever wisecracks for the benefit of none but himself and perhaps some imaginary audience of ghosts and angels. at that time i hadn’t, to my knowledge, actually watched any of the classic bogart & co. detective movies, so my metaphysical drag act was itself composed from impressions and parodies. i was, however, quite intimate with other strains of 1940s cinema (i was in the archives mainly to study a film from that decade) and though my active memory has retained nothing of “casablanca” (1942), i did see that film at a Formative Age and this would seem the most likely source of my improbable and ultimately impossible lifelong obsession with becoming a jaded-yet-romantic american expat on the fringes of europe.

lying prone in the rubble of my exploded expat fantasies back in my native california, i watched movies projected on my ceiling and in most cases enjoyed a vacation from my psychological perspective through the temporary occupation of another. but once in a while, i caught my own reflection in the kino-eye. such was the case with “angel heart,” a meticulously formalist meditation on the fractured collective psyche of “postwar” america via the methodical deconstruction of a man composed entirely of echoes and fictions masking unbearable trauma from participating in ritual human sacrifice both literally (as an occultist) and metaphorically (as a soldier in the war). as a supernatural creation bearing the souls of both perpetrator and victim of the sacrifice, his trauma response is self-annihilating – a mystical representation of the psychosis experienced by all us cogs in the war machine, one-souled or otherwise. the two souls bound up in harry angel/johnny favorite both experienced the war from a sidelined, un-masculine position: one as a section 8 discharge dismissed after a brief, traumatizing stint of service, the other as an enlisted entertainer. this allegory resonated in the contours of my imagination with incredible sonority, but i saw my reflection well before the plot unfolded, in the very first scenes of the film, in the physical demeanor affected by mickey rourke loping awkwardly through dirty manhattan snow in a wool trenchcoat. i had caught a similar reflection many times in the windows of moscow and petersburg as i trudged through dirty snow, insulating my frightened self from a hostile world with a similar wool trenchcoat and self-effacing butch affect cribbed from cinema-mediated memories of ‘20s-‘30s tough guys.

my identification with this character/performance is only one undercurrent of this noise-music composition, but it is the one i feel needs the most explication. the meanings carried by the other voices (among them those of vyacheslav tikhonov portraying an exhausted soviet agent within the ss in early 1945 berlin, leonid utesov singing the praises of his beloved odessa, and alexander vertinsky crooning an emigrant’s lament for distant st. petersburg) are more self-apparent.

2/23/2023

media sampled here:

audio from the films

“the third man” (1949)

“семнадцать мгновения весны” (1972)

“angel heart” (1987)

“black angel” (1946)

“casablanca” (1942)

song recordings

“у черного моря” (leonid utesov, 1953)

“girl of my dreams” (etta james, 1960)

“чужие города” (alexander vertinsky, 1936)

“крейсер «аврора»” (choir of the leningrad pioneers’ hall, 1982)

additionally

personal audio recordings

midi file created from the composition “песня о далекой родине” (1972) by mikаеl tariverdiev

the accompanying video was created with samples from the above-mentioned films, as well as personal recordings and archival footage from a filmed concert performance by leonid utesov in 1940.

audio edited & produced using ableton live 9

video edited & produced in windows movie maker + microsoft clipchamp

some notes on the recordings i used as material for this piece

during this last year of trauma recovery, i saw myself most vividly in one particular cinematic incantation of postwar psychosis co-created by a brit and an american both too young to have experienced wwii but raised in its fallout as men in societies where the publicly synthesized idea of maleness is overwhelmingly suffused with the radioactive particles still emitting from the atoms of that war. watching mickey rourke’s performance in alan parker’s metaphysically-canted neo-noir “angel heart” (1987) somehow made a narrative out of the glossolalia of confusion and pain humming at the core of my being during the strung-out spring that followed the terrible winter of ’21-’22.

in the autumn before that winter, i had found strength and solace from the encroaching fascist terror in russia in the exploration and nurturing of my own masculinity. i had long identified more with a masculine perspective than a female one, but various factors limited the extent to which i expressed this identification. various other factors led to me reaching new levels of masculine identification and expression that fall, and this was a positive, self-actualizing experience that nurtured me during the months in which i lived under increasingly dire threat of repression from a government officially opposed to the existence of queers, americans, and gender studies researchers within its borders.

months of trudging alone through seedy hotels, anxious crowds, and icy boulevards, all while looking over my shoulder for police, were bearable if i saw myself as a sort of postmodern pastiche of film noir protagonists, a hardboiled detective working an increasingly dangerous case, an existentially bedraggled man in the wrong time, space, and body muttering clever wisecracks for the benefit of none but himself and perhaps some imaginary audience of ghosts and angels. at that time i hadn’t, to my knowledge, actually watched any of the classic bogart & co. detective movies, so my metaphysical drag act was itself composed from impressions and parodies. i was, however, quite intimate with other strains of 1940s cinema (i was in the archives mainly to study a film from that decade) and though my active memory has retained nothing of “casablanca” (1942), i did see that film at a Formative Age and this would seem the most likely source of my improbable and ultimately impossible lifelong obsession with becoming a jaded-yet-romantic american expat on the fringes of europe.

lying prone in the rubble of my exploded expat fantasies back in my native california, i watched movies projected on my ceiling and in most cases enjoyed a vacation from my psychological perspective through the temporary occupation of another. but once in a while, i caught my own reflection in the kino-eye. such was the case with “angel heart,” a meticulously formalist meditation on the fractured collective psyche of “postwar” america via the methodical deconstruction of a man composed entirely of echoes and fictions masking unbearable trauma from participating in ritual human sacrifice both literally (as an occultist) and metaphorically (as a soldier in the war). as a supernatural creation bearing the souls of both perpetrator and victim of the sacrifice, his trauma response is self-annihilating – a mystical representation of the psychosis experienced by all us cogs in the war machine, one-souled or otherwise. the two souls bound up in harry angel/johnny favorite both experienced the war from a sidelined, un-masculine position: one as a section 8 discharge dismissed after a brief, traumatizing stint of service, the other as an enlisted entertainer. this allegory resonated in the contours of my imagination with incredible sonority, but i saw my reflection well before the plot unfolded, in the very first scenes of the film, in the physical demeanor affected by mickey rourke loping awkwardly through dirty manhattan snow in a wool trenchcoat. i had caught a similar reflection many times in the windows of moscow and petersburg as i trudged through dirty snow, insulating my frightened self from a hostile world with a similar wool trenchcoat and self-effacing butch affect cribbed from cinema-mediated memories of ‘20s-‘30s tough guys.

my identification with this character/performance is only one undercurrent of this noise-music composition, but it is the one i feel needs the most explication. the meanings carried by the other voices (among them those of vyacheslav tikhonov portraying an exhausted soviet agent within the ss in early 1945 berlin, leonid utesov singing the praises of his beloved odessa, and alexander vertinsky crooning an emigrant’s lament for distant st. petersburg) are more self-apparent.

#music#personal#noise#sound art#soundscape#trauma#ptsd#war#movies#my life in movies#film#russia#ukraine#ussr#cinema#digital music#art experiment#noise art#sound collage#audio collage#россия#украина#война#кино#музыка#video art

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Unlikely Advocate - No Spindle Required (PART 2)

Baldwin’s decision to make Isobel his blood sworn daughter draws the condemnation of the witches and provokes Lady Percy, the child’s grandmother, to request custody.

Brought before the congregation to answer for his actions in the wake of Eileen’s condition, and demonstrate his suitability as Isobel’s father, he has one last card to play.

PART 1

Tags: @adowbaldwin @butternuggets-blog @sylverdeclermont @lady-lazarus-declermont @ordinarymom1 @thereadersmuse @marirable @pleasereadmeok

———

“You had no right to proceed before notifying the Congregation!” Satu lectured Baldwin, standing, not in his place of power, but in the centre as an accused.

In his place was Diana.

“I request that Mrs Bishop-Clairmont-“ Gerbert started.

“Doctor Bishop-Clairmont,” Diana interrupted, “if you wish to address me formally, you should at least do so correctly!”

“My apologies,” Gerbert sneered, “I request that Doctor Bishop-Clairmont recuse herself from this proceeding due to her familial connection with the accused.”

“There must be a de Clermont present in order to start a meeting and since no-one holding the title of de Clermont is without a familial tie to the accused, this meeting could not proceed.”

“Awfully convenient.” Gerbert interjected.

“The rules are not on trial,” Janet Gowdie gave Diana a knowing glance, “let us get back to haranguing a single father for doing what’s best for his daughter. Tell me, Mr Montclair, how old is the child in question?”

“Six, she will be seven on the tenth of next month.”

“Why did you mark her as your blood sworn daughter when she has a family already.” Janet prompted.

“Both the child’s mother and her aunt, my wife, who is the guardian chosen by this very body, were estranged from the family, it was Eileen’s wish that Isobel not be returned to them.”

“That is not a decision that can be made cross species,” Satu interjected, “the child is a witch she must be raised by witches, it is our rules!”

“Rules are rules.” Domenico needled Baldwin with his own words.

“Regardless of the actions that led to this,” Agatha spoke up, “the fact is that the child was lawfully adopted by Baldwin, it is binding, by both human and creature doctrine. She is now a de Clermont.”

“I agree,” Diana added, “the same authority that permits me to act as the de Clermont representative also makes her Baldwin’s daughter.”

“So his haste is to be rewarded?” Satu argued.

“What reward,” Baldwin snarled at her “my wife lies in a permanent coma and my daughter has lost not only her birth parents, but a beloved aunt who raised her. For my part, I had the honour of assisting in this for almost five years alongside Eileen. It was her wish that I take responsibility in the event that anything should happen to her. It happened. I took responsibility.”

“We should hear from the complainant,” Satu suggested, “bring in Lady Percy.”

“Will I have to talk?” Isobel asked Miyako as they sat in the congregation waiting chamber.

Miyako grinned playfully.

“It’s not like you to not want attention.” She teased the child who giggled at the statement.

“That’s different,” she smoothed out her brand new dress, effortlessly slipping into the serious de Clermont manner, “that’s with you and Uncle Baldwin...” she trailed off.

“What’s wrong?” Miyako noted her troubled look.

“I call him Uncle Baldwin because that’s what I’ve always called him but now, isn’t he my Dad, what does he want me to call him?”

Miyako sighed, there was no easy answer to give her.

“I think he wants you to call him whatever you feel comfortable with. The ritual we did was to make sure he can protect you, that nobody could take you away.”

Isobel nodded in understanding before a mischievous grin appeared.

“But I’m your only little sister, right?”

“Yes, I always wanted one, but you know, be careful what you wish for!” She caught the child, administering tickles which caused Isobel to giggle loudly.

“Take your hands off my grand-daughter!”

The blonde witch hissed from the door. She had two guards at her back.

Instantly, Miyako was on her feet in front of Isobel.

“Ma’am, we must proceed to the chamber!” One of the guards eyed Miyako nervously.

“Isobel, listen to me,” Lady Percy shook off the grip of the guards, “she is not your family, I am.”

“Family doesn’t do what you tried to do with yours!”

“What are you talking about?” The witch hit back.

“You’ll see!”

Miyako turned away to check on Isobel when the older witch summoned a fire-bolt and aimed it towards the vampire.

It was instantly deflected with a gust of witch-wind from Isobel.

“That’s my big sister you nasty, old...” Isobel hesitated, unsure if she should continue, “bitch!”

The Congregation had heard the commotion but until the doors opened, they were unsure on the events.

“Well, using offensive magic on this ground is not a great start,” Diana scowled, “do you have an explanation for yourself?”

“That vampire was upsetting my grand-daughter!”

“The grand-daughter we heard yell ‘that’s my sister’,” Baldwin started, “along with some questionable language that I will address with her later.”

He wondered where he could purchase a room sized teddy bear for the girl.

“It’s not appropriate for a witch to fraternise with vampires. Just because the covenant is no more, doesn’t mean we have to like it, bad enough my own daughter married one but she pulls my grand-daughter into this sin too!”

“I move to present my evidence demonstrating the unsuitability of this woman to be the guardian for a young child.” Baldwin continued with his case.

“What is this evidence? I have a right to know!”

“Peter Knox, your brother-”

“Oh, so my brother’s crimes are also my own? Or is it because I didn’t cave to social demand to denounce him. What he did was ill advised...”

“Silence,” Satu spoke up sharply, “your brother provided countless witches to Benjamin Fox, to be tortured, raped, forced to carry and miscarry his children until the mercy of death took them. Explain to me how that is I’ll-advised?”

“I did none of those things thusly I think you had better strike whatever evidence you have against him from my list of offences.”

“Unless you were involved,” Diana prompted, “did you offer him anyone, anyone at all?”

“N-No, of course not!” She hastily denied.

“I will continue,” Diana glared, “Knox kept a meticulous record of transcribed telephone conversations, many have been confirmed by the members in this chamber. Was there ever any conversation you might have had that could have been misconstrued by him?”

“Not to my knowledge,” she shook her head but looked decidedly less confident.

“He needs a powerful witch, Sophia would be ideal,” Diana read from a leather journal, “she would be the mother of a new race, guaranteeing the power and position of our family for eons.”

“What is that?” Gerbert asked.

“One of his transcribed calls, with Lady Percy,” Diana answered and turned to the woman, “do you remember this conversation, perhaps your response?”

The woman straightened up but remained silent.

Diana returned her attention on the book.

“Not Sophia,” Diana continued to read, “she is much too important to this family to risk on an uncertainty, what about Eileen?”

“You were going to bargain with your own daughter?” Janet Gowdie asked, the disgust evident on her face.

“Isobel was not even a factor in her decision,” Baldwin argued, “if Sophia was any less powerful she would have betrayed her, regardless of whether it would leave her grand-daughter without a mother!”

“I have heard plenty,” Satu spoke up, “and despite my distaste for the girl being raised by a vampire, I believe him to be the best placed to protect her.”

“Agreed,” Janet nodded and, along with Satu, glared at the young male wizard that had not long joined.

“Me too!” He added hastily.

“I do not,” Gerbert objected, “by all accounts the child is very powerful and the de Clermont’s already have two witch-vampire hybrids. How much power do you all want to give them?”

“As the only person here who understands and who has seen the love and care he has for the child, I must find in his favour.” Diana argued.

“I vote no,” Domenico sighed, “it’s too much power concentrated in one place. The risk of discovery by humans is too great and I believe that used to be a concern.”

“We vote for Baldwin also.” Agatha concluded.

“You are all fools, she needs a witch or her powers will become unstable.” Lady Percy hissed.

“I was raised by my aunt’s, witches, if she requires assistance with her magic, I, as her aunt will help her.” Diana answered.

“I won’t stay here and be lectured to by a traitor!”

The woman turned to find the guards directly behind her.

“What is the meaning of this?”

“You betrayed your own kind,” Diana stood, “they have the right to pursue action against you.”

She directed her words to the other witches.

“Do you want her released to your custody?”

“Yes, we need to hold our own hearing.” Janet answered definitively.

“Wait,” the newer witch objected, “what’s the sentence, what will happen to her?”

“She would be spellbound,” Satu answered, glancing nervously at Diana, “but in this case I believe it to be appropriate.”

“I’ll defer to both of your judgement,” the third witch gave a nod of approval.

“You can’t,” Lady Percy sneered towards Baldwin, “not if you want your wife back!”

“What did you say?” He glowered.

“It was a stroke of genius to keep her suspended in a magical state, she would have kept deteriorating, until I got what I want!”

“You would murder your own daughter to get the chance to pour your malice into another child?” Satu asked.

“I already have,” she shrugged, “Sophia found out what Peter was involved in and was going to expose him. It would have ruined our family name and I couldn’t allow that. You don’t understand how far I’d be willing to go to protect the Percy legacy!”

“And I thought witches were supposed to be intelligent,” Gerbert chuckled, “this one freely confessed to a crime nobody accused her of committing!”

“Shut up,” Baldwin snarled at him before turning his ire onto the witch, “you murdered your own daughter, and are willing to let another die. What of Isobel, would you sacrifice her for the good of your family?”

“No,” she spat, “my sons have power but not like Sophia. If Isobel is half the witch my daughter was, she is our future. Anyway, you are without another option, this is a negotiation. I give you what you want, you give me what I want!”

“Let me guess, the child?” Diana glared.

“Just to see her one last time.”

Baldwin laughed, a sound that surprised everyone in the room and had Diana look at him as though she questioned his sanity.

“Eileen’s power wasn’t just her magic, it was her conviction, her strength and her compassion,” he spoke with calm confidence, “but you mistook that for weakness, you thought she had less power because she didn’t channel it into what you thought was valuable! You will never see Eileen or Izzy again!”

“Her name is Isobel!” The witch shrieked.

“It is,” he remained calm, “Isobel Sophia Évelyne de Clermont and you just told me everything I need to know to save my wife!”

“Baldwin?” Diana prompted.

“The spell was never on Eileen, it was on Izzy, she knew Eileen would give up her magic and life force to save her. That’s why she wants to see Izzy, to kill both of them!”

“You have no proof of that, vampire!”

“Not yet,” he hissed, biting back the intense desire to rip out her throat, “but if anything happens to either of them, there will be nothing left of your legacy!”

“This meeting is over, we have voted and it is now up to the witches to administer punishment,” Diana looked to the three witches, “is that acceptable?”

“Yes, go, quickly, bring our sister witch back!” Janet encouraged and received a grateful nod from Diana.

“Come on!” She grabbed Baldwin by the arm, pulling him through the doors and towards the waiting area.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinner And A Show

Part of the Ellis AU. @lonesome--hunter, @iaminamoodymoodtoday, @wildfaewhump, @ishouldblogmore, @lektricwhump

@just-a-whumping-racoon-with-wifi.

He was wearing an emerald-green silk shirt and black slacks. His shoes were polished and his hair was brushed and tied back. The ponytail was a little off centre, so that it lay over one shoulder and made a striking contrast with the shirt. He looked amazing – and the button-up sleeves hid all of his scars.

“You’re going to ace it,” Nic said as they fastened his cufflinks. “Just be confident, and don’t hesitate. Remember, this is work, not a real date. You just have to seem genuine.”

“Not a problem,” Ellis said. He briefly flashed a look of wide-eyed, guileless innocence, and Nic laughed. They laughed even as they remembered just how Ellis had come to possess that skill.

“Yeah, like that. You’ll be in control the whole time, honey.”

Ellis nodded, consulting his file one last time before setting it down on the floor. Alistair knelt there, hands holding the chain in his lap, head bent. He would be reading the file, Ellis’s strategy guide, the whole way through the outing, providing Ellis with the ability to check any detail he’d forgotten. No information would escape him. No surprises. He would be in control.

Nic kissed his cheek, and smiled. “Perfect. Go on, taxi’s waiting.”

They watched him go with a wistful smile. His back was straight and his head held high as he descended the stairs to leave. He’d never used to walk like that. He’d never been comfortable as the centre of attention. But then, they were starting to understand. The person he was day to day...wasn’t really him. He only came back to them in those private moments alone.

They hated what he was doing. They hated why he was doing it even more. He’d come out of it, one day.

For Ellis’s part, he was too busy thinking about the meeting. When he arrived, he was still thinking through information he could use. When he greeted her, he made sure his handshake was one she liked.

Handshake: Like she’s trying to crush your fingers and she wants you to do it back.

“Mr Engels,” she said, seeming impressed. “In the flesh.”

Ellis smiled sweetly. “That’s me. Pleasure, Ms Farringdon.”

She allowed him to lead her into the restaurant, and didn’t speak until they were seated. Only once the waiters were at a distance did she say, “I have heard rumours about you. You are... Different to the image I had.”

Ellis smiled a little less warmly now. He knew what the rumours about him were. Some of them, he had planted. “Let me guess. A terrifying crime lord, or Alistair’s sugar baby.”

“The latter,” she acknowledged. “They said you were... Pretty.”

He smiled again. Self-effacing, a touch embarrassed. “I’m glad you think so. But back to the pertinent topic. Why did you agree to meet me? I know you’re not on best terms with the original Engels.”

She looked to the side, prefacing her avoidance of the question. “I don’t recall any significant animosity between us.” Then her eyes returned to him and she smiled. “I was curious, of course. Alistair has worked alone for so long.”

“He has,” Ellis agreed neutrally. He looked down at the menu, considering.

Food: Hates seafood of all kinds. Hates hot food. Subtle flavours.

“I recommend the risotto,” he offered, as he selected the vegetarian ravioli for himself. “Mild flavour, delicate seasoning.”

She raised a sardonic eyebrow. “No starter?”

“Oh, naturally,” he said smoothly. “But the main course should be accounted for, when ordering the first.”

She hummed a brief chuckle. One slip, navigated successfully. He returned to looking at the drinks, until she spoke again.

“Why didn’t he come himself?”

Her tone was hardened around the edges, marked by her suspicion. There were rumours about him, yes, but she didn’t know that this was the person she’d expected to meet. He could have sent a decoy. He could be the decoy, for Alistair.

“Indisposed,” he said simply. None of her doubt was being expressed aloud, and he didn’t need to address it yet. “He sends his regards.”

She rolled her eyes. “Unlikely. He doesn’t like me.”

Alistair: ‘She’s a ruthless egomaniac who would kill her own mother for a tactical advantage.’

“He respects you,” he replied, setting his menu aside for the sake of signalling to their waiter that they were ready. “He did not think you should be subjected to dinner with him. Colleagues you may be, but friends, you are not.”

She considered that for a moment. He sat still under her blue eyes, reading his expression as best she could. He made sure to look simple, pleasant and honest, and while she wouldn’t truly believe that, the plausible deniability was useful.

She looked all the way to his shirt cuffs before looking back up. “Nice cufflinks.”

The formality was eroding. Ellis smiled, touching one. “Thank you. I hope you find dinner with me tolerable, if not pleasant.”

She propped her elbow on the table, chin resting across the back of her hand as she regarded him more intensely. Under his shirt the scars hid, and itched, and she kept looking.

Farringdon shook her head. “You don’t have to try so hard, cherub. Your partner and I have worked together enough in the past that you have some goodwill. Let’s just try to have fun.”

Ellis smiled properly, eyes bright with perfectly practised sincerity. “Let’s.”

-

Ellis closes his eyes with his hands poised over the keyboard.

Absolute silence in his home. Alistair is by the desk, waiting for an order. Nic is outside in the garden, reading under the porch. It’s raining, but Ellis had the office soundproofed a while ago. No sound in. No sound out.

He reaches for her.

Vision. Hearing. He connects himself up to her, taking in everything that she does. His hands start to move on the keyboard.

Computer, OS, email client, email address, every one that he can read down the side of her screen. Subject titles, as fast as he can type them, before she clicks off.

Email drafting. He transcribes in synchronicity with her, a second behind the movements of her body. He follows her pauses, her typos, her corrections, her edits. He is exactly as focused as she is, her words flowing onto her page and onto his without pause.

Email sent. Closed. More subject titles for what’s in her inbox. More in her sent items.

A video of horses. Even professional murderers have hobbies.

Then she checks it. Finally, she opens her phone and checks it, and he sees clearly the little GPS tracker she put on his bag when she thought he wasn’t looking - and he wasn’t, not with his own eyes, he practically handed her the opportunity. The bag is on a bus right now, and she closes the app, returning her attention to the computer.

A file. Title, date, last modified, author, and the content as fast as he can type it, which is faster than she can read it. Some distant thought recognises that the file is about him. He doesn’t pause. He will have her knowledge, all of her knowledge, and then he will know exactly what she thinks of him.

A notification on her phone pings and she looks down at it. Payment confirmation. He catches the banking app, the mobile network, the amount. She checks the GPS again, and sees its location.

She looks back at the profile of him and he types out the details of his own weekly routine without stopping to think about what it might mean until she gets up, and picks up a pre-packed bag, and takes one last look at her file and his photo and he watches her read the line about where he will be at this time of day, which he isn’t, because he’s watching her, and she heads out of the house.

She gets into her car, license plate noted, make, model, colour, landmarks around where she is driving from, street names, he can work out where she’s based later, and then she drives to his gym.

Before she gets out of the car, she checks her bag. He’s not surprised to see what’s inside.

In the pause as she looks, he writes a note to himself. Cancel gym membership.

He watches her move through the rooms in search of him. He watches her circle the property. He takes notes on how she enters and exits, how she avoids notice, the way she glances for cameras and speaks to those she passes as though she were a normal patron. He will learn from her, as he has learned from everyone in his life.

She leaves after half an hour of looking for him, bag still slung over her shoulder. She gets back into her car and pulls out a different phone. Dials a contact, and Ellis’s fingers fly to record the number.

“Hello.”

Ellis’s fingers stop.

“He wasn’t there.”

“Well, keep trying. You only have to find him once. I’m a patient man.”

The line disconnects.

Ellis opens his eyes. At the bottom of his garbled, rushed, typo-ridden document, there is a single word spelt with precision.

Harvey.

He takes a deep breath, and rests his wrists on the desk as the assassin drives home.

Harvey is trying to kill him.

#psychological whump#ellis: a whumper#my fic#whump#paranoia fuel#telepathy#failed assassination#manipulation#manipulative whumper#ellis#harvey#farringdon#nic

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like I should remind everyone that I actually write sometimes too — shocking, I know. So here’s a thing I wrote a long time ago, just to pretend that I’m a real Writeblr for a bit.

If there ever was a reason to be grateful, it was that Blake lives in a time where coffee and other sources of caffeine are readily available. Although it was just before 9 o'clock in the morning, she was already half-way through her second mug and a small tower of used creamers were stacked unevenly at the corner of her desk. Damn those early morning meetings; was it really necessary to gather everyone under the age of twenty-five early in the morning to discuss the implications of retweets? The Capital was full of old, decrepit people who would still use fax machines if they could. At this point, Blake was sure she was spending more time teaching her superiors how to use computers instead of her actual job.

And they said that the life of a journalist wasn't glamourous.

Her desk was full of unfinished drafts, photographs, and other piles of papers stacked haphazardly over every inch of the surface. With a sigh, Blake just piled the existing piles on top of each other to create a precarious mountain of paper to clear out some space. It was organized chaos at its finest — her desk may be a mess, but she knew where everything was... Or at least she hoped.

With a heavy sigh and tapping fingers fueled by coffee jitters, Blake impatiently waited for her computer to load web pages. Fingers automatically typed up ‘twitter.com’ into the address bar, but she thought better of it and quickly hit backspace. After lecturing a sixty-year old crusty, balding man on how to navigate the 'tweeter-sphere', she really wasn't in the mood to revisit the social media site and its apparently impossible-to-use interface.

When she logged into her email account, it was no surprise that hundreds of unread emails were blinking on the browser. 317 emails to be exact, the red bubble notification on her phone had been mocking her for days now. Wearily, Blake started clicking and manually sorting through useful emails and trash that didn't even need to be read. Passive-aggressive work memos from loud coworkers (shut up Patricia, no one cares about your lunch), junk mail (there's a sale going on in a nearby department store apparently), and death threats (only 12 emails, significantly less than yesterday) were among the ones immediately deleted without even opening.

Several rapid clicks later, her inbox was emptied of all unnecessary emails, and she could focus on what actually mattered — once she sorted through all of the false leads, that is. Days ago, Blake had published a request for the Other to contact her if they wanted their stories heard. It was a good idea in theory to gather information and first-hand accounts, but she really, really should've seen the amount of humans pretending to be the Other coming. Internet anonymity was a bitch, and a lot of trolls, people that were obsessed with the Other and bored humans who had way too much time on their hands were claiming to be special.

Somehow, Blake sincerely doubted that a real vampire or werewolf would throw in blatant Twilight or Vampire Diaries references into these emails. Just a hunch. On the off chance that they were truly what they said they were, it wasn't the type of person (could they still be called a person?) she wanted to write about. Now that article would immediately become the laughing stock of the internet. Blake's mouse hovered over the trash can icon for a long second as she fought the urge to delete the lot of them. Duty won out, just in case she was deleting important information. The things she would do for a story...

There was one email in particular however, that seemed more genuine for whatever reason. Call it journalist's intuition, or just a lack of modern (if slightly outdated) pop culture references.

Dear B. Preston,

Apologies for the throwaway email address – I don’t like paper trails. I saw your call for stories from the Other in The Capital, and after serious deliberation, I have decided to express my own interest in the project. I am a vampire of not insignificant experience who would be willing to answer any questions you might have, from my condition in general to my personal history, so long as the result is anonymised.

As this is uncharted territory for the both of us, and perhaps even both our kinds, I am an unsure as to whether the best medium would be in writing or an in-person interview. Whichever option you would feel more comfortable with. Obviously, dining with the stuff of nightmares isn’t everyone’s cup of tea.

Looking forward to your reply.

Sincerely,

Someone who would rather not sign his name in writing.

Blake leaned back into her office chair as she read and reread that email, thoughtfully chewing off the lipstick she had hastily smeared on so that she could claim that she cared about appearances. It was impossible to gleam whether this email rang true or not, but there was something different about this one that felt like it was worth following up on — at least the throwaway email wasn't something like totallyabloodsucker69 that she saw about three emails prior.

After quickly doing her carpal tunnel prevention hand stretches, Blake wrote out a long reply, then went back and deleted an entire unnecessary paragraph and several other snarky comments that had just slipped out. She was a professional, and should probably act as such. No need to scare off a potential vampire contact — as silly as that sounds.

Dear someone who would rather not sign their name in writing,

Thank you for your response, your willingness to share your story to the public is greatly appreciated. I can promise it will be put to good use.

An in-person interview probably would work best, if only to be able to say that I've confirmed that you're a vampire in person. It's far too easy for people to pretend to be something they're not online — there's simply not enough credibility over the internet. I conduct a lot of interviews over at The Daily Grind for the casual atmosphere, but I'm open to any alternatives you have in mind. I've attached my schedule to this email, let me know when you're available.

And finally as a formality — and I honestly have no idea what I'm looking for — is there any way you can send me proof of your claim? As mentioned before, there are far too many people pretending to be anything other than human.

Regards,

Blake Preston.

Perhaps only a split-second after she hit send, a roar of "Preston, turn the radio on now!" was shouted at her from behind. Blake spun around in her chair in alarm, staring at Jones who just barged through the door with wild, panicked eyes.

"What are you——"

"Do it! Now!"

Jones didn't even give Blake another moment to respond as he flew forward to fiddle the radio to the right broadcast, not bothering to wait for the shocked journalist to catch up to his intensity. Precious few seconds were evidently lost as Jones' fumbling fingers finally managed to push the right set of buttons. Blake actually listened to On the Edge radio quite often, but an unfamiliar voice flowed through the speakers.

Think of the teenagers lost during Nick Bloodfang’s rampage: three young girls, on their way home from a party on the wrong night of the lunar cycle, left for dead. That is only the tip of the iceberg...

Though she didn't quite understand what was going on yet, Blake turned on the recording function of her phone after seeing Jones frantically gesticulated to her. Blake's brows were knit in confusion as she listened to the broadcast. Something wasn't right, something didn't feel right.

Blake's jaw dropped along with her stomach as the 'segment' ended with a human call for action. It was pathos at its finest, playing up on the fear that she knew swept throughout the humans when the Other first came to light a month or so ago. Even though the current position of most people was uncertain, tension and fear grated roughly on most humans that she knew. Jones and Blake shared a slack-jawed stare of disbelief.

This was hate speech, inciting people to violent acts because they painted the Other as mere criminals with no other purpose besides murdering innocent people.

By the time Louise's voice came back on the air, Blake snapped out of her stupor to open a brand new word document on her computer. Although the highjack had ended only seconds before, she was already replaying it on her phone as her fingers flew over the keyboard, transcribing it to the best of her ability. "I can't believe I missed the bloody beginning. Colin, did you get——"

Blake's fingers kept moving as she glanced over to her partner's desk, suspiciously empty and untouched since yesterday.

"Where the hell is Colin!?"

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s also a problem with the skills of many of the interpreters I hear in court. I can’t tell whether this happens just because they’re not confident public speakers or perhaps because they are really more translators (working with the written word which can be revised) and not specialised in on-the-spot interpretation, but often their answers are difficult to hear and ungrammatical, sometimes to the point of being confusing as to meaning.

It’s also not unusual to hear a lawyer ask a question in English, the interpreter repeat it in the witness’ language, the witness answer in that language, and then the interpreter saying something in English that just doesn’t sound like an answer to the question that was put. Of course sometimes you get that even when everyone speaks English because a witness misunderstands the point of the question or is just being evasive (or believes the lawyer is asking trick questions and responds to what they think they’re “really” asking), but it’s worrying.

Bilingual colleagues of mine have heard factual errors in translation, and on one occasion I transcribed when the witness was bilingual and answering in English, followed by the interpreter repeating what he said in Cantonese for the defendant‘s benefit, the witness stopped and said “That’s not what I said. She’s translating me wrong.” The whole trial had to be put on hold for both interpreters working on it to listen again to the in-court recordings and check their (and each other’s) interpretations in the transcript for errors. At least they could do that!

I would guess that because of an overall shortage, the courts are often settling for interpreters who might be able to do good written translations or interpretation in a less formal and specialised setting, but do not have the appropriate skills for interpreting in a trial, and it makes it hard to have faith that either defendants or complainants who aren’t fluent in English are getting a fair court process.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Voice Content and Usability

We’ve been having conversations for thousands of years. Whether to convey information, conduct transactions, or simply to check in on one another, people have yammered away, chattering and gesticulating, through spoken conversation for countless generations. Only in the last few millennia have we begun to commit our conversations to writing, and only in the last few decades have we begun to outsource them to the computer, a machine that shows much more affinity for written correspondence than for the slangy vagaries of spoken language.

Computers have trouble because between spoken and written language, speech is more primordial. To have successful conversations with us, machines must grapple with the messiness of human speech: the disfluencies and pauses, the gestures and body language, and the variations in word choice and spoken dialect that can stymie even the most carefully crafted human-computer interaction. In the human-to-human scenario, spoken language also has the privilege of face-to-face contact, where we can readily interpret nonverbal social cues.

In contrast, written language immediately concretizes as we commit it to record and retains usages long after they become obsolete in spoken communication (the salutation “To whom it may concern,” for example), generating its own fossil record of outdated terms and phrases. Because it tends to be more consistent, polished, and formal, written text is fundamentally much easier for machines to parse and understand.

Spoken language has no such luxury. Besides the nonverbal cues that decorate conversations with emphasis and emotional context, there are also verbal cues and vocal behaviors that modulate conversation in nuanced ways: how something is said, not what. Whether rapid-fire, low-pitched, or high-decibel, whether sarcastic, stilted, or sighing, our spoken language conveys much more than the written word could ever muster. So when it comes to voice interfaces—the machines we conduct spoken conversations with—we face exciting challenges as designers and content strategists.

Voice Interactions

We interact with voice interfaces for a variety of reasons, but according to Michael McTear, Zoraida Callejas, and David Griol in The Conversational Interface, those motivations by and large mirror the reasons we initiate conversations with other people, too (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-01). Generally, we start up a conversation because:

we need something done (such as a transaction),

we want to know something (information of some sort), or

we are social beings and want someone to talk to (conversation for conversation’s sake).

These three categories—which I call transactional, informational, and prosocial—also characterize essentially every voice interaction: a single conversation from beginning to end that realizes some outcome for the user, starting with the voice interface’s first greeting and ending with the user exiting the interface. Note here that a conversation in our human sense—a chat between people that leads to some result and lasts an arbitrary length of time—could encompass multiple transactional, informational, and prosocial voice interactions in succession. In other words, a voice interaction is a conversation, but a conversation is not necessarily a single voice interaction.

Purely prosocial conversations are more gimmicky than captivating in most voice interfaces, because machines don’t yet have the capacity to really want to know how we’re doing and to do the sort of glad-handing humans crave. There’s also ongoing debate as to whether users actually prefer the sort of organic human conversation that begins with a prosocial voice interaction and shifts seamlessly into other types. In fact, in Voice User Interface Design, Michael Cohen, James Giangola, and Jennifer Balogh recommend sticking to users’ expectations by mimicking how they interact with other voice interfaces rather than trying too hard to be human—potentially alienating them in the process (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-01).

That leaves two genres of conversations we can have with one another that a voice interface can easily have with us, too: a transactional voice interaction realizing some outcome (“buy iced tea”) and an informational voice interaction teaching us something new (“discuss a musical”).

Transactional voice interactions

Unless you’re tapping buttons on a food delivery app, you’re generally having a conversation—and therefore a voice interaction—when you order a Hawaiian pizza with extra pineapple. Even when we walk up to the counter and place an order, the conversation quickly pivots from an initial smattering of neighborly small talk to the real mission at hand: ordering a pizza (generously topped with pineapple, as it should be).

Alison: Hey, how’s it going?

Burhan: Hi, welcome to Crust Deluxe! It’s cold out there. How can I help you?

Alison: Can I get a Hawaiian pizza with extra pineapple?

Burhan: Sure, what size?

Alison: Large.

Burhan: Anything else?

Alison: No thanks, that’s it.

Burhan: Something to drink?

Alison: I’ll have a bottle of Coke.

Burhan: You got it. That’ll be $13.55 and about fifteen minutes.

Each progressive disclosure in this transactional conversation reveals more and more of the desired outcome of the transaction: a service rendered or a product delivered. Transactional conversations have certain key traits: they’re direct, to the point, and economical. They quickly dispense with pleasantries.

Informational voice interactions

Meanwhile, some conversations are primarily about obtaining information. Though Alison might visit Crust Deluxe with the sole purpose of placing an order, she might not actually want to walk out with a pizza at all. She might be just as interested in whether they serve halal or kosher dishes, gluten-free options, or something else. Here, though we again have a prosocial mini-conversation at the beginning to establish politeness, we’re after much more.

Alison: Hey, how’s it going?

Burhan: Hi, welcome to Crust Deluxe! It’s cold out there. How can I help you?

Alison: Can I ask a few questions?

Burhan: Of course! Go right ahead.

Alison: Do you have any halal options on the menu?

Burhan: Absolutely! We can make any pie halal by request. We also have lots of vegetarian, ovo-lacto, and vegan options. Are you thinking about any other dietary restrictions?

Alison: What about gluten-free pizzas?

Burhan: We can definitely do a gluten-free crust for you, no problem, for both our deep-dish and thin-crust pizzas. Anything else I can answer for you?

Alison: That’s it for now. Good to know. Thanks!

Burhan: Anytime, come back soon!

This is a very different dialogue. Here, the goal is to get a certain set of facts. Informational conversations are investigative quests for the truth—research expeditions to gather data, news, or facts. Voice interactions that are informational might be more long-winded than transactional conversations by necessity. Responses tend to be lengthier, more informative, and carefully communicated so the customer understands the key takeaways.

Voice Interfaces

At their core, voice interfaces employ speech to support users in reaching their goals. But simply because an interface has a voice component doesn’t mean that every user interaction with it is mediated through voice. Because multimodal voice interfaces can lean on visual components like screens as crutches, we’re most concerned in this book with pure voice interfaces, which depend entirely on spoken conversation, lack any visual component whatsoever, and are therefore much more nuanced and challenging to tackle.

Though voice interfaces have long been integral to the imagined future of humanity in science fiction, only recently have those lofty visions become fully realized in genuine voice interfaces.

Interactive voice response (IVR) systems

Though written conversational interfaces have been fixtures of computing for many decades, voice interfaces first emerged in the early 1990s with text-to-speech (TTS) dictation programs that recited written text aloud, as well as speech-enabled in-car systems that gave directions to a user-provided address. With the advent of interactive voice response (IVR) systems, intended as an alternative to overburdened customer service representatives, we became acquainted with the first true voice interfaces that engaged in authentic conversation.

IVR systems allowed organizations to reduce their reliance on call centers but soon became notorious for their clunkiness. Commonplace in the corporate world, these systems were primarily designed as metaphorical switchboards to guide customers to a real phone agent (“Say Reservations to book a flight or check an itinerary”); chances are you will enter a conversation with one when you call an airline or hotel conglomerate. Despite their functional issues and users’ frustration with their inability to speak to an actual human right away, IVR systems proliferated in the early 1990s across a variety of industries (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-02, PDF).

While IVR systems are great for highly repetitive, monotonous conversations that generally don’t veer from a single format, they have a reputation for less scintillating conversation than we’re used to in real life (or even in science fiction).

Screen readers

Parallel to the evolution of IVR systems was the invention of the screen reader, a tool that transcribes visual content into synthesized speech. For Blind or visually impaired website users, it’s the predominant method of interacting with text, multimedia, or form elements. Screen readers represent perhaps the closest equivalent we have today to an out-of-the-box implementation of content delivered through voice.

Among the first screen readers known by that moniker was the Screen Reader for the BBC Micro and NEEC Portable developed by the Research Centre for the Education of the Visually Handicapped (RCEVH) at the University of Birmingham in 1986 (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-03). That same year, Jim Thatcher created the first IBM Screen Reader for text-based computers, later recreated for computers with graphical user interfaces (GUIs) (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-04).

With the rapid growth of the web in the 1990s, the demand for accessible tools for websites exploded. Thanks to the introduction of semantic HTML and especially ARIA roles beginning in 2008, screen readers started facilitating speedy interactions with web pages that ostensibly allow disabled users to traverse the page as an aural and temporal space rather than a visual and physical one. In other words, screen readers for the web “provide mechanisms that translate visual design constructs—proximity, proportion, etc.—into useful information,” writes Aaron Gustafson in A List Apart. “At least they do when documents are authored thoughtfully” (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-05).

Though deeply instructive for voice interface designers, there’s one significant problem with screen readers: they’re difficult to use and unremittingly verbose. The visual structures of websites and web navigation don’t translate well to screen readers, sometimes resulting in unwieldy pronouncements that name every manipulable HTML element and announce every formatting change. For many screen reader users, working with web-based interfaces exacts a cognitive toll.

In Wired, accessibility advocate and voice engineer Chris Maury considers why the screen reader experience is ill-suited to users relying on voice:

From the beginning, I hated the way that Screen Readers work. Why are they designed the way they are? It makes no sense to present information visually and then, and only then, translate that into audio. All of the time and energy that goes into creating the perfect user experience for an app is wasted, or even worse, adversely impacting the experience for blind users. (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-06)

In many cases, well-designed voice interfaces can speed users to their destination better than long-winded screen reader monologues. After all, visual interface users have the benefit of darting around the viewport freely to find information, ignoring areas irrelevant to them. Blind users, meanwhile, are obligated to listen to every utterance synthesized into speech and therefore prize brevity and efficiency. Disabled users who have long had no choice but to employ clunky screen readers may find that voice interfaces, particularly more modern voice assistants, offer a more streamlined experience.

Voice assistants

When we think of voice assistants (the subset of voice interfaces now commonplace in living rooms, smart homes, and offices), many of us immediately picture HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey or hear Majel Barrett’s voice as the omniscient computer in Star Trek. Voice assistants are akin to personal concierges that can answer questions, schedule appointments, conduct searches, and perform other common day-to-day tasks. And they’re rapidly gaining more attention from accessibility advocates for their assistive potential.

Before the earliest IVR systems found success in the enterprise, Apple published a demonstration video in 1987 depicting the Knowledge Navigator, a voice assistant that could transcribe spoken words and recognize human speech to a great degree of accuracy. Then, in 2001, Tim Berners-Lee and others formulated their vision for a Semantic Web “agent” that would perform typical errands like “checking calendars, making appointments, and finding locations” (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-07, behind paywall). It wasn’t until 2011 that Apple’s Siri finally entered the picture, making voice assistants a tangible reality for consumers.

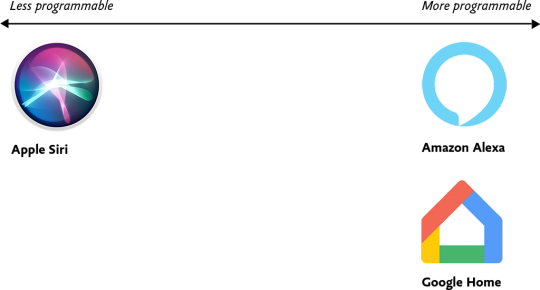

Thanks to the plethora of voice assistants available today, there is considerable variation in how programmable and customizable certain voice assistants are over others (Fig 1.1). At one extreme, everything except vendor-provided features is locked down; for example, at the time of their release, the core functionality of Apple’s Siri and Microsoft’s Cortana couldn’t be extended beyond their existing capabilities. Even today, it isn’t possible to program Siri to perform arbitrary functions, because there’s no means by which developers can interact with Siri at a low level, apart from predefined categories of tasks like sending messages, hailing rideshares, making restaurant reservations, and certain others.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, voice assistants like Amazon Alexa and Google Home offer a core foundation on which developers can build custom voice interfaces. For this reason, programmable voice assistants that lend themselves to customization and extensibility are becoming increasingly popular for developers who feel stifled by the limitations of Siri and Cortana. Amazon offers the Alexa Skills Kit, a developer framework for building custom voice interfaces for Amazon Alexa, while Google Home offers the ability to program arbitrary Google Assistant skills. Today, users can choose from among thousands of custom-built skills within both the Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant ecosystems.

Fig 1.1: Voice assistants like Amazon Alexa and Google Home tend to be more programmable, and thus more flexible, than their counterpart Apple Siri.

As corporations like Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google continue to stake their territory, they’re also selling and open-sourcing an unprecedented array of tools and frameworks for designers and developers that aim to make building voice interfaces as easy as possible, even without code.

Often by necessity, voice assistants like Amazon Alexa tend to be monochannel—they’re tightly coupled to a device and can’t be accessed on a computer or smartphone instead. By contrast, many development platforms like Google’s Dialogflow have introduced omnichannel capabilities so users can build a single conversational interface that then manifests as a voice interface, textual chatbot, and IVR system upon deployment. I don’t prescribe any specific implementation approaches in this design-focused book, but in Chapter 4 we’ll get into some of the implications these variables might have on the way you build out your design artifacts.

Voice Content

Simply put, voice content is content delivered through voice. To preserve what makes human conversation so compelling in the first place, voice content needs to be free-flowing and organic, contextless and concise—everything written content isn’t.

Our world is replete with voice content in various forms: screen readers reciting website content, voice assistants rattling off a weather forecast, and automated phone hotline responses governed by IVR systems. In this book, we’re most concerned with content delivered auditorily—not as an option, but as a necessity.

For many of us, our first foray into informational voice interfaces will be to deliver content to users. There’s only one problem: any content we already have isn’t in any way ready for this new habitat. So how do we make the content trapped on our websites more conversational? And how do we write new copy that lends itself to voice interactions?

Lately, we’ve begun slicing and dicing our content in unprecedented ways. Websites are, in many respects, colossal vaults of what I call macrocontent: lengthy prose that can extend for infinitely scrollable miles in a browser window, like microfilm viewers of newspaper archives. Back in 2002, well before the present-day ubiquity of voice assistants, technologist Anil Dash defined microcontent as permalinked pieces of content that stay legible regardless of environment, such as email or text messages:

A day’s weather forcast [sic], the arrival and departure times for an airplane flight, an abstract from a long publication, or a single instant message can all be examples of microcontent. (http://bkaprt.com/vcu36/01-08)

I’d update Dash’s definition of microcontent to include all examples of bite-sized content that go well beyond written communiqués. After all, today we encounter microcontent in interfaces where a small snippet of copy is displayed alone, unmoored from the browser, like a textbot confirmation of a restaurant reservation. Microcontent offers the best opportunity to gauge how your content can be stretched to the very edges of its capabilities, informing delivery channels both established and novel.

As microcontent, voice content is unique because it’s an example of how content is experienced in time rather than in space. We can glance at a digital sign underground for an instant and know when the next train is arriving, but voice interfaces hold our attention captive for periods of time that we can’t easily escape or skip, something screen reader users are all too familiar with.

Because microcontent is fundamentally made up of isolated blobs with no relation to the channels where they’ll eventually end up, we need to ensure that our microcontent truly performs well as voice content—and that means focusing on the two most important traits of robust voice content: voice content legibility and voice content discoverability.

Fundamentally, the legibility and discoverability of our voice content both have to do with how voice content manifests in perceived time and space.

Voice Content and Usability published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Well I’m still not entirely happy with this but theater work and holiday shopping have derailed me far more than I’d like lately so you know what? good enough. CHAPTER TIME!

This last part ends To Last the Night. I really hope that you’ve enjoyed reading it and its predecessor. I wanted to say one final THANK YOU~!! to everyone who’s liked or reblogged or sent nice comments because really you guys are the absolute best. And a super special thanks to the wonderful @spacegate whose fantastic ideas, writing, and art inspired this work and whose support meant and still means more than words can say. You are amazing!

Now the big question is; can I get anything done on my other fic? I’m sure gonna try to.

To Last the Night

Sequel to Whispers in the Dark

Pairings: None

Characters: Sans, Papyrus, Grillby, Dogaressa, Dogamy

Warnings: none for this chapter (let’s catch up with the guardians one last time before we say goodbye)

Notes: Baby Blasters AU belongs to the wonderful @spacegate, I just love writing awful angst for it.

Read on AO3 here (chapters go up on tumblr first)

Chapter 14

“Door,” a voice sang out, echoed by a small, high pitched howl that rang through the apartment above Grillby's bar. “Someone's at the door!”

“Alright, I'll be right there.”

The owner of both the home and the joined establishment smoothed barely visible wrinkles from his pressed white shirt as he strolled towards the front door. He was all but certain that he already knew who was about to arrive and that they wouldn't care or even notice if he was a bit disheveled from work, but the instinct to make sure he looked presentable wasn't to be ignored regardless.

Sans and Papyrus were already there when he arrived. The taller of the two was all but scratching at the wooden surface, excited by the approaching sounds he heard from beyond it. These days it was nothing new to see the pair so excited, especially Papyrus who hopped from fixation to fixation with all the energy and enthusiasm of an over-caffeinated bunny. And yet, this everyday sight was still something wondrous to Grillby. He'd never have imagined a life like this when he'd first met the pair, nor the dangers he'd have to face it in order to keep it.

It had been many long months since they'd escaped from what was now a lonely, burnt out shell of a house on the outskirts of Hotland. In many ways, the incident and the disturbing sequence of events that had preceded it felt so distant. Some days he had to remind himself that it hadn't all been some terrible nightmare or a story he'd read in a book years ago. But then he'd notice something small, like burn marks on wooden floors or the way the children would sometimes flinch at the shadows that had once felt so comforting to them, and the reality of it all would leave him staggered. It had been real. The scattered snippets of memory he clung to had actually happened despite the tricks his mind was constantly trying to play on him. And the mysterious erasure of it all was just as real.