#ironheart series

Link

Alden Ehrenreich is set to star in a key role in Marvel’s “Ironheart” series for Disney+.

Ironheart will star Dominique Thorne as Marvel character Riri Williams, a genius inventor and creator of the most advanced suit of armor since Iron Man. Anthony Ramos is also on board. It’s still unclear who Ehrenreich will play.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

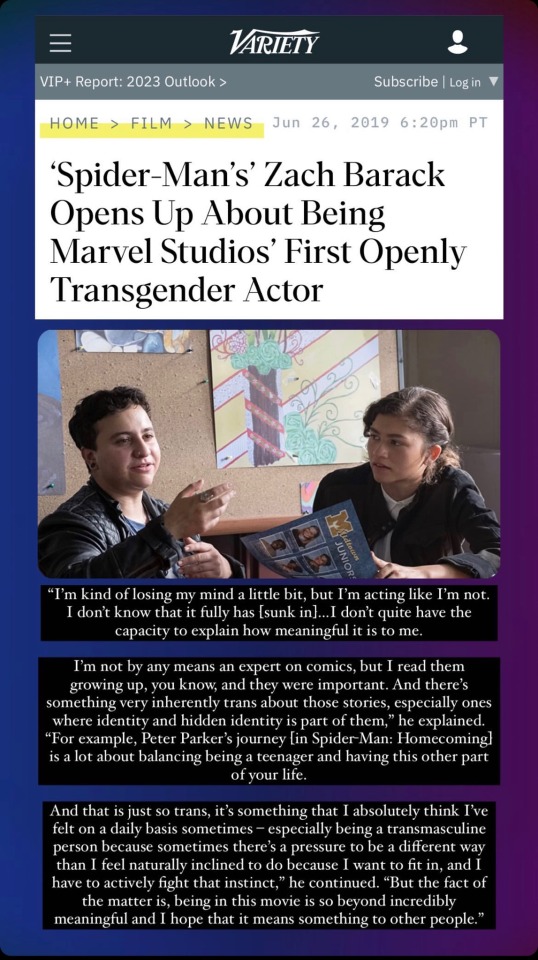

Diversity in the MCU

In recent years, Marvel (and Disney) has been making some effort to diversify their stories, characters, and actors/actresses. There is still a very, very long way to go, even in the industry (even in the world around us, really) for proper representation of underrepresented communities.

As such, I don’t know if I have the right to post this, but I do think this deserves at least a bit of a look.

The first is an old article that I’ve only recently found.

The second I found also yesterday:

Do let me know what you think.

#mcu#spider man far from home#sm ffh#Zach Barack#transgender#variety magazine#ironheart#ironheart series#zoe terakes#transmasc#collider#the direct#diversity#trans representation#what do you think?#penny for your thoughts#reblogging#representation matters

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay so from what I understand, the Ironheart series is going to debut with just 6 episodes, which is unacceptable to me but I'll allow it because it's better than nothing.

But if that's what we're doing each episode had better be 45-60 minutes long. I have no idea how they're going to squish her backstory, friends, allies, enemies, adventures into just 6 episodes but regardless, we need to show up and show out for this one.

A lot of Black and brown women are contributing to this show and there's enough Black and brown women in the audience/Marvel fandom for this series to really take-off and for all us Black female nerds out here, this is long overdue.

We're still over 6 months away from the premiere but my blog will definitely be a hotspot for for any news, updates, videos, etc, related to promoting Ironheart as we close in on Fall 2023. I'm not expecting any major sneak peeks, trailers, etc to drop before this summer so we'll just have to hang tight until then. Word on the street is Shuri makes a cameo appearance in the series (probably in a video chat or something) so I'm definitely hyped for that.

I'm trying to ignore all the hate and bashing from palm colored men in the Marvel fandom are already spewing about this character for even debuting in the first place, most of it is nonsense of course. I've been waiting on the Ironheart wave all my natural life so they can kick rocks. (Don't forget to follow Dominique Thorne on IG if you haven't already.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARVEL SHOWS

New posters!

Credit to Marvel on Instagram

#dots updates#dots marvel updates#marvel#marvel shows#marvel series#marvel studios#echo#echo series#agatha harkness#agatha coven of chaos#agatha wandavision#ironheart#ironheart series#secret invasion#loki show#loki series#loki season two#what if show#what if#what if season two#what if season 2#loki season 2

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Note

MM and Mae working together again possibly……. To be a fly on the wall 🤣😂😭

Anon, I have been laughing about this for d a y s.

It's only a short film and the cast is so (bizarrely) stacked I don't reaaallllly imagine they'll have any scenes together or even have been on set at the same time, but who knows.

The idea of actors like Anthony Carrigan, Alan Tudyk, Jay Baruchel and Wendi McLendon-Covey potentially being looped into GG set drama is also unbelievably funny to me.

#thanks for this anon#i've had a pretty weird-to-bad few days so to laugh about this again has been very nice#mm only seeming to get jobs through his friends right now too is lowkey interesting to me#the ironheart series not coming out until september 2025 now is um#pretty rough for him professionally#and not a great sign for the project tbh#a shame because i thought riri was cute in bp#anyway retta christina and mae stay booked and busy!#i'm v v v excited for retta in hitman and the greatest hits and christina in hacks and small town big story <3#(but yes to be a fly on the wall hahah)#gg asks#welcome to my ama

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

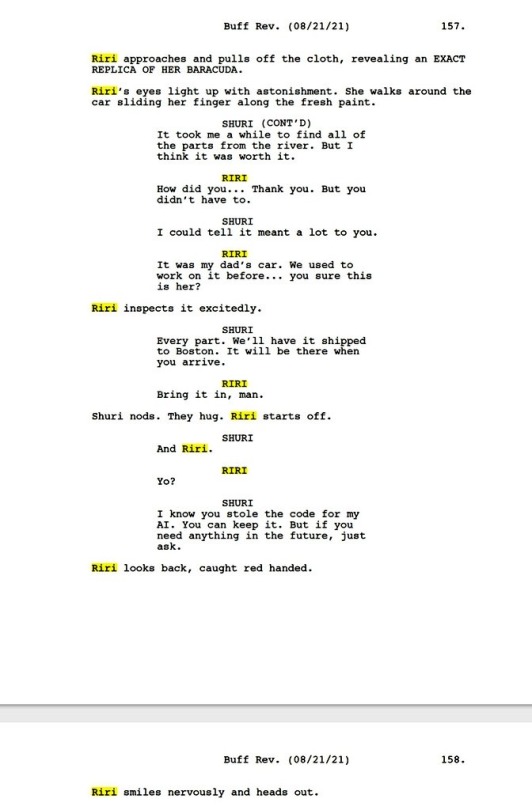

i see your “riri was asking shuri out on a date to chicago” and i raise you “riri taking shuri to coachella or disneyland just like what she wanted in bp1”

#just let them go on a date man#ironheart series writers im looking at yall#tbh t’challa would take shuri there if they had more time tgt :(#great now im sad#bpwf#black panther#ironheart#shuriri#pantherheart#shuri#riri williams#t’challa#shuri x riri#riri x shuri

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shuri and Riri have even more homoerotic subtext than Steve and Bucky in Captain America: The Winter Solider (and that was movie was incredibly gay). they are in gay love.

#When Shuri appears in the Ironheart Disney+ series I expect a love confession#marvel#mcu#shuri x riri#shuriri

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

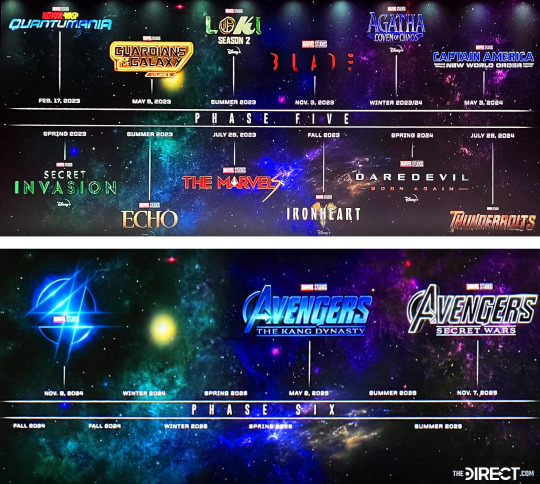

Hm...

Echo could be interesting.

Agatha: House of Harkness seems like a bit of a reach.

I’ll hold out hopes for Ironheart.

I liked Loki Season One, so Season Two should be good.

And I honestly have no idea why they’re doing Secret Invasion when the Skrulls aren’t evil.

Overall, a pretty...meh lineup.

...Am I getting over Marvel?

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

#movie magic#movie news#movies#mcu#marvel#marvel cinematic universe#news#mcu phase 4#disney+#tv series#armour#armor wars#don cheadle#secret invasion#ironheart#ironman#iron man#tony stark#tony stank#kevin feige#james rhodes#war machine#robert downey jr#riri williams#black panther wakanda forever#marvel phase five#phase 5#mcu phase 5#marvel news#iron man 3

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

marvel so irritating like if you gon ruin wlw pairings at least set em correctly cause now i gotta give riri/viv a devestating teen wlw breakup and they not even the main pairing in this fic

#mcu#riri williams#canon is a suggestion actually#even tho im not writing in strictly the comics canon i am enjoying reading up on them#theyre so cute#marvel release the ironheart tv series im fighting for my life rn

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

after the announcements at sdcc and the trailers that came out tonight, there’s no chance of me ever being normal, especially about marvel

#marvel phase 4#marvel phase four#mcu phase four#mcu phase 4#marvel phase 5#mcu phase 5#secret invasion#she hulk#she hulk attorney at law#black panther#black panther wakanda forever#ant man and the wasp#ant man and the wasp quantumania#guardians of the galaxy#gotg vol 3#echo series#loki tv series#blade#ironheart#agatha coven of chaos#captain america#captain america 4#daredevil#daredevil born again#thunderbolts

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Estreias das séries da Fase 5 da Marvel.

Invasão Secreta – Entre Março e Maio de 2023

Loki: Temporada 2 e Echo – Entre Junho e Setembro de 2023

Ironheart – entre setembro e dezembro de 2023

Agatha: Coven do Caos - Final de 2023/inicio de 2024

#SDCC#MCU#Marvel#Serie#Series Disney+#Disney+#Disney Plus#Invasão Secreta#Loki#Ironheart#Agatha: Coven do Caos#Agatha#marvel phase five#marvel fase 5

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iron heart (2025): Release Date, Cast, Trailer, Plot, where to watch?

Marvel fans rejoice! The highly anticipated Iron heart TV series on its way, bringing another thrilling superhero tale to screens. With its captivating plot, talented cast, and the promise of heart-stopping action, heart is poised to become one of the most-about shows in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). In this blog post,’ll take a closer look at the release date, cast, trailer, plot, and…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Flying Toward a Twenty-First Century Aesthetics of Technomagic Girlhood

by Ravynn K. Stringfield

What is Technomagic Girlhood?

When I began thinking, reading and writing about Black girl superheroes in my dissertation, I found I wanted a way to explore how characters like Riri Williams as Ironheart and Lunella Lafayette as Moon Girl were both performing fantastic feats while defining and creating their Black girlhood with the scientific, technological, and digital tools available to them. Their oft favorite feat? Flight. This list of characters includes but is in no way limited to: Shuri from Black Panther lore, Karen Beecher as Bumblebee, Lunella Lafayette as Moon Girl, and Max from Batman Beyond, the animated television show which ran on the Kids’ WB from 1999 to 2001. There are arguments to made for extending the category to include characters like Marvel Comics’ Misty Knight or even young Diana (Dee) Freeman from HBO Max’s Lovecraft Country, a speculative horror show adapted as a continuation of the 2016 Matt Ruff novel of the same name. In entering a conversation around Black superheroines that scholars like Sheena Howard, Deborah Whaley and Grace D. Gipson have nourished, technomagic girlhood became the term I used, as I was fascinated by the way innovative digital practices and self-making become intertwined for Black girls in superhero stories where our current reality and its technologies were recognizable, but where these girls could manipulate technology to give themselves the ability to literally (and metaphorically) fly.

The idea of technomagic girlhood draws energy from a number of related terms, primary among them being Afrofuturism, the artistic/aesthetic movement and critical framework around the relationship of folks of the African diaspora to the future, technology, and questions of liberation.1 Technomagic girlhood sits underneath the large Afrofuturistic umbrella, though it takes as its large focal point the fantasy genre, magic, the unexplained, whereas much of the strongest Afrofuturistic theorizing prioritizes science fiction as a genre. Work is being done amongst scholars all over to push the boundaries of what constitutes Afrofuturism, and what is in conversation with it.

Also related is Moya Bailey’s term, digital alchemy, which she uses in Misogynoir Transformed to refer to “the ways that women of color, Black women, and Black nonbinary, agender, and gender-variant folks in particular transform everyday digital media into valuable social justice media that recode the failed scripts that negatively impact their lives” (24). Hashtags under the work of Black women, Black queer folks and Black gender expansive folks become entire movements, with “alchemy” implying a chemistry. The chemistry of it all denotes a type of a work, rather than the social justice media appearing as if by will alone, and not backed by the labor of Black women and femmes. I prefer technomagic rather than alchemy because magic connotes, for some a discipline, but contains a joy of use as well. Bailey continues: “Digital alchemy shifts our attention from the negative impact stereotypes in digital culture to the redefinition of representations Black women are creating that provide another way of viewing their worlds” (24). There is a joy in learning to manipulate science, technology and the digital to your own ends for experiments in redefinition and self-making in technomagic girlhood.

For this playful turn, I draw from digital ethnomusicologist Kyra D. Gaunt’s work on embodied play and Black girlhood. I also use “magic” because it locates me more clearly in a legacy of the Black speculative, the Black fantastic, longer traditions of Black girls in magic—and accounts more clearly for how it is possible for these girls to fly. But to fly does not always mean “magic” is afoot. Flight is a condition of reality in texts such as Virginia Hamilton’s retelling of African American folk tales, The People Could Fly (1985), in which Africans take flight back home, and Toni Morrison’s critically acclaimed novel, Song of Solomon (1977), in which Pilate takes to the air. The “techno” prefix is inspired in part by film scholar Anna Everett’s work on Black technophilia and draws us more toward a legacy of Black participation in technology and the digital.

As in #BlackGirlMagic, a commonplace example of technomagic girlhood practice to me, the magic and the fantastic are deeply rooted in reality. This hashtag originates with CaShawn Thompson, who in an interview with journalist and author Feminista Jones says: “I was the first person to use Black Girl Magic or Black Girls Are Magic in the realm of uplifting Black women. Not so much about our aesthetic but jut who we are.” Our magic, Thompson argues, is simply the truth; it was true of her everyday life and how she experienced the world. There is nothing speculative about it, and simply and uniquely of Black girlhood. In many ways, Thompson’s understanding of Black Girl Magic is in conversation with how I understand technomagic girlhood and the potential of what it could be.

I specifically came to use “technomagic” when writing about Marvel Comics’ teenage superhero Riri Williams, also known as Ironheart. The young Chicagoan was able to create her own version of Tony Stark’s Iron Man suit, making her supergenius hypervisible on a large scale, but which she uses locally to help her community. Afrofuturism was the term that I had used for a long time in my work on her, but when we are first introduced to Riri in Eve L. Ewing and Luciano Vecchio’s run, this Black girl, in her tech suit by which she has engineered herself the ability to fly, her face turned skyward, reveling in joy and legacy as seen below…something else occurring. Something that needed to center Riri’s Black girlhood, her experimental and creative self-making through technology, and the joy of impossibility now made tangible…2

Technomagic girlhood is in part a response to some of the questions that André Brock, Jr. asks in Distributed Blackness about whether or not his work on technology and the internet is Afrofuturistic: what about the digital present? Afrofuturism, Brock argues, “is rightly understood as a cultural theory about Black folks’ relationship to technology, but its futurist perspective lends it a utopian stance that doesn’t do much to advance our understanding of what Black folk are doing now” (15). In considering the “now” in possibilities of Black technophilia, technomagic was where I had space to spread out and play as Riri does, as many of the contemporary Black girls do, informed deeply by the legacies and lineages that have come before.

Cover Girls

I choose to examine here Riri Williams as the catalyst for my interest in the topic, along with DC Comics’ Natasha Irons. In what follows, I address these characters’ relationship to technomagic, as seen in the covers for the collected edition of Ironheart: Meant to Fly (Marvel, 2020) and Action Comics #1054 (DC Comics, 2023) that exemplify a few core characteristics of a visual aesthetics of technomagic girlhood and work in tandem.

Technomagic describes a particular quality of contemporary Black girlhood, expansively defined. While this idea most certainly can be applied to other groups of people, I use it as a way of understanding the relationship Black girls in superhero media and other fantasy narratives have to science, technology and digital media, to creativity and joy, and to self-making. By Black girlhood, I often think of how Aria S. Halliday and the authors of the Black Girlhood Studies Collection interrogate the ways in which society tends to conflate Black girlhood and Black womanhood, in both seemingly innocuous and explicitly dangerous ways. Black girls’ joy practices are central to education scholar Ruth Nicole Brown’s work and are resonant here when viewing Riri in Ironheart #1, skyward facing, heart open and Natasha’s focused joy on the cover shown below.

To remember that Black girlhood can be expansive, it is important to incorporate writers who consider girlhood to be a state of mind and being, rather than exclusively an age range. Digital ethnomusicologist Kyra D. Gaunt, for example, asks readers to engage questions of girlhood that include women who might begin their intimate stories to each other with a resonant, “Giiiirl” (p. 2). And Moya Bailey urges readers to consider a wider breadth of possible people who might be brought in by widening what we consider womanhood in her book Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance—in particular, she argues that more than cisgendered heterosexual Black women are harmed by misogynoir (p. 18-22). This is relevant for Natasha (above right), who is canonically a lesbian in the comics, and whose cover brings to mind the colors of the bisexual flag: pink, purple and blue.

After the primary condition of Black girlhood is established, there are secondary conditions that are present in an aesthetics of technomagic girlhood. These include elements of:

impossibility, whether feats or conditions;

creativity, ingenuity, or innovation, often expressed as a practice of the girl in question;

technology, science, or digital media;

self-making or alter-ego creation; and

unbridled joy.

The magic emerges from the clear masterful manipulation of most of these elements in a playful fashion, often for heroic ends, though regularly for their own enjoyment as well.

When we look at these two covers together, we can see elements from many of these categories. On Riri’s cover (by Amy Reeder for Ironheart #43), we see a young Black girl who has presumably engineered herself the ability to fly—impossibility—but who, in this instance, is now falling. Riri falls downward and, judging by the surprise on her face, it appears that the Ironheart suit she has created for herself has fallen apart. It calls to mind the image of the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus, though Riri is both: she is both the famed inventor and also the child who maybe has flown too close to the sun. Riri’s relationship to this myth calls to mind the ingenuity and technology inherent to technomagic girlhood. But the image is juxtaposed with the title phrase “meant to fly”—so, perhaps it is that Riri’s suit is coming to her, not away from her, to save her, to enable her flight, because that impossible feat is what she deserves, and she knows it is hers. She created the impossible and trusts in her own ability—self-making. Notably, in issue #1, Riri can find who she is within the suit, and within a larger legacy not just of superheroics, but of Black women who made her possible. This is both self-making and joy.

DC Comics’ Black girl science genius, Natasha Irons, has a longer history than Riri Williams. Where Riri’s origins date back to the Invincible Iron Man run in 2016 (Vol. 3 #7) written by Brian Michael Bendis and illustrated by Mike Deodato, Natasha Irons was introduced as Dr. John Henry Irons’ precocious niece in Steel #1 (February 1994), written by Jon Bogdanove and Louise Simonson, with art by Chris Batista and Rich Faber. While Irons earns his claim to fame by filling in for Superman, going on to becoming a hero in his own right, over time Natasha develops an aptitude for science as she hangs around her uncle, eventually proving adept at working on Irons’ suit and going on to develop her own. Natasha’s heroism in her own right has only deepened with time. With a new Steelworks run beginning in the summer of 2023, there have been opportunities for Natasha fans to get excited. Most recently, Action Comics #1054 had a variant cover (1:25) by Milestone Initiative artist Yasmín Flores Montañez featuring a solo Natasha in a similar vein to the iconic Riri “Meant to Fly” cover (shown above).4

On this cover, Natasha more clearly appears to be attracting the pieces of her suit to her as she leans over, possibly suspended in air—similar to some iconic scenes from the Marvel Cinematic Universe Iron Man films—anchored by a neon pink background, with a touch of blue, guiding viewer to think more critically about our gendered assumptions regarding technology and science. There’s a look of satisfaction on her face—this is where she is meant to be. She clearly wears the crest of the House of El—Superman’s iconic “S”—as a symbol of hope, though perhaps this will mean something different for Natasha in the issues to come. Natasha’s relationship to this technology, her ability to manipulate it, will inevitability lead to some creative self-making in relationship to this iconic symbol and who she is within in—and without it.

Optimally, technomagic girlhood does not prioritize a capitalistic notion of the lone Black girl science genius. It is not simply “Black Girls Code” for a means to an end. There must be a fantastic joy to it, enabling the Black girl in question to just be, to simply exist, to feel confident in exploring her sense of self, to experiment in self-making. It is not the entering into science and technology spaces to perpetuate capitalistic ideas of productivity or advancement, but for joy and exploration of the self. Therefore, those who care about the well-being of Black girls—all children—must work toward communal needs being met.

In order for this to be meaningful, it needs to be communal, or in relation to others, as it is portrayed in Eve L. Ewing’s twelve-issue Riri Williams: Ironheart run (2018-2019). The idea of the lone Black girl genius feeds into harmful stereotypes related to the magical Negro; instead, intelligence can, and should be, nurtured in community. In Ewing’s Ironheart, Riri’s mother is a loving and watchful presence. Xavier King is Riri’s friend in the series, not just a teammate as many of the other supers she encounters in other runs are. Xavier cares about Riri as a person, with no real investment in what she can offer him. Those who participate in technomagic girlhood are still, after all, girls—children—and still need to love and be loved.

Ewing’s Ironheart gives Riri something she hasn’t had until that point: space to be. We should be working towards these girls’ ability to just be. The ability to create and play in these spaces is contingent on safety. Though Black girl will continue to create and play in spite of oppressive systems, it does not mean these systems as constructed are just. What will it mean for technomagic girlhood to not just be reactive, but to be generative?5 What will it mean for technomagic girlhood to embrace Afrofuturism in so far as it connects to questions of abolition, which devalues the role of policing and commits to a politics of care, as we seek to imagine new and better worlds for Black people, especially children?6 By this I mean: when safety and care are prioritized, what new worlds might our Black girls imagine with their newfound access to digital tools?

Conclusion

With technology, science, and digital media as the backdrop of our era, Black girls who engage in technomagic are increasingly enabled. They are the girls in fantasy stories who may not be gifted with an inexplicable gift for controlling the weather or who can speak to animals, but who have a technophilia akin to magic. They make their ordinary lives extraordinary with their ability to manipulate and build their sense of self in the process. Here, I’ve examined technomagic in superhero narratives, but the principles can and likely will apply across different types of speculative media where Black girls have unique relationships to science, technology and digital media. In particular, these girls are often seen more widely in comic stories adapted for screen: most folks met Riri Williams for the first time on screen in Wakanda Forever (dir. Ryan Coogler, 2022), the sequel film to Black Panther (dir. Ryan Coogler, 2018).

While the general connotation of this term slants towards positivity, as does a related popular phrase like Black Girl Magic, or the hashtagged version: #BlackGirlMagic, it’s worth approaching it with a touch of skepticism and several doses of care. Technomagic, while it does align us with the idea of the Black girl science genius, can also perpetuate the trope of the solitary genius, an idea which Ironheart writer, Eve L. Ewing, problematizes in a 2021 interview with Catapult: “…If that [the trope of the Black girl STEM superhero] becomes the only mode through which we see Black girls, that’s also a problem… I love Ironheart, I love Riri, but Shuri and Riri and Moon Girl are all science geniuses, you know? How does that reinforce certain limited notions about what Black intelligence or Black genius has to look like? How does that play into capitalist-driven conversation about Black girls in coding or Black girls’ participation in science fields?”

To Ewing’s inquiry and to Bailey’s assertions that digital alchemy helps us think about the possible ways Black women are redefining and rethinking about themselves, technomagic girlhood might offer one potential answer. Where we are able to keep joy practices, build and form community together, and experiment in self-making, we protect the essence of technomagic girlhood.7

Notes

1 The term “Afrofuturism” was originally coined in the 1994 roundtable essay “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose” by cultural critic Mark Dery in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. It is noted in the essay that Afrofuturism, both as an aesthetic and as a critical framework, has a much longer history, including origins that are often thought of as musical, thinking about the contributions of experimental musicians such as Sun Ra.

2 In this panel, Ewing invokes the legacy of Maya Angelou's poem “Still I Rise” (1978). The entire stanza reads:

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

3 Notably for this essay, Reeder is also known for her artwork on Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur.

4 Milestone Media was an African American centric superhero comics publishing company founded in 1993 by Dwayne McDuffie, Denys Cowan, Michael Davis and Derek T. Dingle. DC Comics is currently relaunching Milestone and reintroducing its characters by bringing in a class of artists and writers specifically dedicated to the mission of Milestone. Flores Montañez is part of the Milestone Initiative’s inaugural class.

5 This question is in the spirit of Moya Bailey, whose work and distinction between generative and defensive alchemy as one which is creative for the community and one which is responsive to hatred. It is my hope that technomagic girlhood is framed similar to a generative digital alchemy.

6 I think here of the necessary and timely work of abolitionist organizers and writers Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba in their new book Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care (2023).

7 Gratitude: Many thanks to early readers of this piece for offering kind words and useful insights: Vanessa Anyanso, Shira Greer, Dr. Autumn A. Griffin, Dr. Jordan Henley, Grace B. McGowan, Kristen Reynolds and Dr. Justin Wigard. Conversations with KàLyn Banks Coghill and Dr. Francesca Lyn were also invaluable. Though they are not cited here, the scholarship of education scholars Drs. Ebony Elizabeth Thomas and S. R. Tolliver remain deeply influential to how I think and write. I would like to thank Dr. Shawn Gilmore for his careful editorial eye.

Works Cited

Bailey, Moya. Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance. New York University Press (2021).

Bogdanove, Jon and Louise Simonson. Steel #1. DC Comics (1994).

Brock, André. Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. New York University Press, (2020).

Everett, Anna. “On Cyberfeminism and Cyberwomanism: High-Tech Mediations of Feminism’s Discontents.” Signs (Vol. 30, No. 1).

Ewing, Eve L. & Luciano Vecchio. Riri Williams: Ironheart #1-12. Marvel Comics (2018-2019).

Ewing, Eve L. & Luciano Vecchio. Riri Williams: Ironheart: Meant to Fly. Marvel Comics (2020).

Gaunt, Kyra D. The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double Dutch to Hip-Hop. New York University Press (2006).

Halliday, Aria S. ed. The Black Girlhood Studies Collection. Women’s Press, CSP (2019).

Jones, Feminista. “For CaShwawn Thompson, Black Girl Magic Was Always the Truth,” Beacon Broadside (2019). https://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/2019/02/for-cashawn-thompson-black-girl-magic-was-always-the-truth.html

Montañez, Yasmín Flores. Action Comics #1054, 1:25 Variant Cover. DC Comics (2023).

Stringfield, Ravynn. “How Eve L. Ewing Makes Her Stories Fly,” Catapult Magazine, May 19, 2021. https://catapult.co/dont-write-alone/stories/interview-with-dr-eve-ewing-by-ravynn-stringfield

#Ravynn K. Stringfield#feature#comics#Ironheart (comic-book series)#Action Comics (comic-book series)#Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)#film

1 note

·

View note