#hans beckert

Text

Just some really cool shots of Peter Lorre in "M," the first four of which are courtesy of Minovsky.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Peter Lorre tarot: featuring Hans Beckert from M as The World. This card stands for assured success, an overwhelming positive change, but reversed it can stand for stagnation, inertia, permanence. To me, Hans Beckert is a good fit for both: it was this role that brought Peter onto the screen to give us the films we now enjoy. It was what helped him escape Germany and it made him a star. But it was a mixed blessing, because it also trapped him in a perception he spent the rest of his life struggling with. On the one hand he enjoyed some of his cinematic villainy, on the other he hated it and longed for different material. As the last card of the Major Arcana I wanted to end with a bang, and I think nothing is better than the beginning, the role that shaped Lorre's world - M.

#peter lorre tarot deck#peter lorre#hans beckert#m#m - eine stadt sucht einen mörder#m 1931#fritz lang#german cinema#tarot#major arcana#the world

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The quality is very CRUNCH-y, but this is the only snippet I could find of the Hungarian dub of M.

The speech textually is the same as in the original, but the delivery feels a lot more accusatory when Beckert is saying that the criminals could have avoided becoming robbers and killers and etc. if they would have learned an honest profession. In the original Beckert seemed a bit more reserved only really raising his voice when he was talking about the murder. The line delivery is still very good, especially the pain in the voice. Wish I could credit the VA, but there is no information who did it (the voice sounds familiar tho, I just cannot place it and it’s really annoying). Even on the dub list site it says “If you know, let us know as well” lol.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Lorre in "M"

Joseph Grant (India ink, ink wash and pencil on illustration board, 1931)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pete characters from the 30s films I've seen

#i dont love all these alignment charts#but this is a good one so i intend to use it for all of petes characters#so far im going decade to decade#but ive seen so few of petes 50s and 60s stuff that i might combine the decades#peter lorre#m#hans beckert#the man who knew too much 1934#abbott#die koffer des herrn o.f.#stix#crack-up#crime and punishment#roderick raskolniknov#mr moto#the secret agent#the hairless mexican#lancer spy#sigfried gruning#was frauen träumen#otto fuessli#the things ill do out of boredom#mememes#Barron Rudolph Maximillian Tagger

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

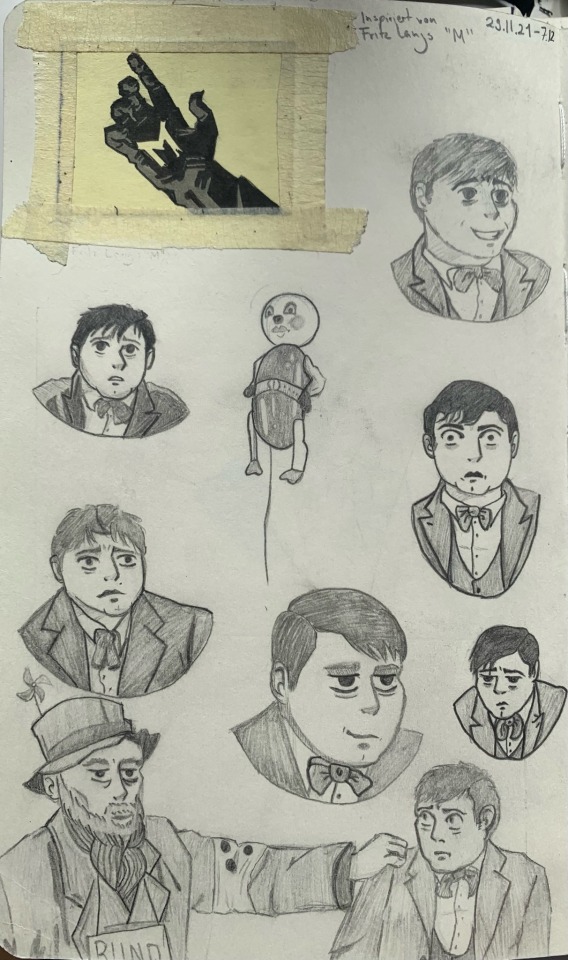

A few skribbles of Peter Lorre as Hans Beckert in M-Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Lorre as Hans Beckert

M (1931)

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the 19th Century, US banks and southern states would sell securities that helped fund the expansion of slave run plantations. To balance the risk that came with forcibly bringing humans from Africa to America insurance policies were purchased.

These policies protected against the risk of a boat sinking, and the risks of losing individual slaves once they made it to America.

Some of the largest insurance firms in the US - New York Life, AIG and Aetna - sold policies that insured slave owners would be compensated if the slaves they owned were injured or killed.

American banks accepted their deposits and counted enslaved people as assets when assessing a person's wealth. In recent years, US banks have made public apologies for the role they played in slavery.

In 2005, JP Morgan Chase, currently the biggest bank in the US, admitted that two of its subsidiaries - Citizens' Bank and Canal Bank in Louisiana - accepted enslaved people as collateral for loans. If plantation owners defaulted on loan payment the banks took ownership of these slaves.

JP Morgan was not alone. The predecessors that made up Citibank, Bank of America and Wells Fargo are among a list of well-known US financial firms that benefited from the save trade.

"Slavery was an overwhelmingly important fact of the American economy," explains Sven Beckert, Laird Bell Professor of American History at Harvard University.

In the 1830s, Southern slaveowners wanted to import capital into their states so they could buy more slaves. They came up with a new, two-part idea: mortgaging slaves; and then turning the mortgages into bonds that could be marketed all over the world.First, American planters organized new banks, usually in new states like Mississippi and Louisiana. Drawing up lists of slaves for collateral, the planters then mortgaged them to the banks they had created, enabling themselves to buy additional slaves to expand cotton production. To provide capital for those loans, the banks sold bonds to investors from around the globe - London, New York, Amsterdam, Paris.

���••

En el siglo XIX, los bancos estadounidenses y los estados del sur vendían seguros para ayudar a expandir las plantaciones de esclavos. Para balancear el riesgo de traer humanos forzadamente de África a América, se compraban pólizas de seguro.

Las pólizas cubrían la posibilidad de que los barcos se hundieran y el riesgo de perder esclavos individualmente una vez que llegaran a América.

Algunas de las compañías de seguro más grandes de los Estados Unidos; New York Life, AIG y Aetna, vendían pólizas a los dueños de esclavos y les aseguraban que serían compensados si los esclavos que les pertenecían se lastimaban o morían.

Los bancos americanos aceptaban los depósitos y contaban a las personas esclavizadas como propiedad cuando se encontraban evaluando la riqueza de una persona. En los años recientes, bancos estadounidenses han emitido disculpas públicas por el rol que jugaron durante la esclavitud.

En el 2005, JP Morgan Chase, actualmente uno de los bancos más grandes de los Estados Unidos, admitió que dos de sus compañías subsidiarias, Citizens' Bank and Canal Bank ubicados en Louisiana, aceptaron a esclavos como garantía para préstamos. Si los propietarios de las plantaciones incumplían con los pagos de los préstamos, los bancos se apropiaban de estos esclavos.

JP Morgan no estaba solo. Los antecesores que formaron a Citibank, Bank of America y Wells Fargo se encuentran en la lista de empresas financieras que se beneficiaron de la trata de esclavos.

"La esclavitud fue un hecho abrumadoramente importante para la economía estadounidense", explica Sven Beckert, profesor Laird Bell de Historia Estadounidense en la Universidad de Harvard.

En 1830, los dueños de esclavos ubicados en el sur querían importar más capital a sus estados para poder comprar más esclavos. Se les ocurrió una nueva idea que consistía de dos partes: hipotecar esclavos; y luego convertir las hipotecas en bonos que podrían comercializarse en todo el mundo. Primero, los plantadores estadounidenses organizaron nuevos bancos, generalmente en nuevos estados como Mississippi y Louisiana. Elaborando listas de esclavos como garantía, los plantadores los hipotecaron a los bancos que habían creado, lo que les permitió comprar esclavos adicionales para expandir la producción de algodón. Para proporcionar capital para esos préstamos, los bancos vendieron bonos a inversionistas de todo el mundo: Londres, Nueva York, Ámsterdam, París.

#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#english#spanish#blackhistory#history#share#read#blackpeoplematter#blackhistorymonth#knowyourhistory#culture#like#newpost#historyfacts#no justice no peace#black lives matter#blackownedandoperated#blackbloggers#louisiana#banks#jpmorgan#slavery#black history is american history#america#blm#bilingual#knowledgeisfree#knowledgeispower#bank of america

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustaf Gründgens in M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

Cast: Peter Lorre, Ellen Widman, Inge Landgut, Otto Wernicke, Theodor Loos, Gustaf Gründgens, Friedrich Gnaß, Fritz Odemar, Paul Kemp, Theo Lingen, Rudolf Blümner, Georg John, Franz Stein, Ernst Stahl-Nachbaur. Screenplay: Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang. Cinematography: Fritz Arno Wagner. Art direction: Emil Hasler, Karl Vollbrecht. Film editing: Paul Falkenberg.

Point of view is everything in a thriller. Let the viewer see events through the wrong eyes, and suspense goes out the window. The remarkable thing about Lang's great thriller is that the point of view changes so often. It starts with that of anxious parents, knowing that a child-killer is on the loose, then narrows to one particular parent, waiting for her daughter to come home from school for lunch. But then we see the object of her fears, her daughter, making contact with a strange man, and our suspense builds as we return to the worried mother. But as strongly as we sympathize with the mother, we also eventually learn to focus our anxieties elsewhere: on the beleaguered police, on innocent victims of people's suspicions, on the criminal underworld harassed by the police, and eventually even on the murderer himself. There are even moments when, as he becomes the object of the manhunt, trapped in the attic of a building swarming with the criminals in search of him, we find ourselves semi-consciously rooting for him to escape. Then we find ourselves rooting for the criminals to capture him and to escape being caught by the cops. And then, when he is put on trial by the criminals, we root for the police to arrive and rescue him. In short, the movie is a study in the ways in which sympathy can be manipulated. Lang and his soon-to-be-ex-wife Thea von Harbou wrote the screenplay, and the atmosphere of the film is superbly maintained by the cinematography of Fritz Arno Wagner and the sets of Emil Hasler and Karl Vollbrecht. But none of it would work without the presence of some extraordinary performers, starting with Peter Lorre as the sniveling, obsessed Hans Beckert: a career-defining performance in many ways, considering that Lorre had been known for comic roles on stage before Lang made him a movie star. Then there's Otto Wernicke as Inspector Lohmann, whose performance was so memorable that Lang brought him back as the same character in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), stereotyping Wernicke as a cop for much of his career. And Gustav Gründgens, the imperious leader of the criminal faction, who later became identified with the role of Mephistopheles in stage and screen versions of Goethe's Faust (Peter Gorski, 1960) -- not to mention in Klaus Mann's 1936 novel, Mephisto (and István Szabó's 1981 film version), based on Gründgens's embrace of the Nazis to advance his career.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"what do you want to eat"

hans beckert: the souls of the innocent

also hans beckert: a bagel

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What would you say your top 5 favourite peter lorre characters are?(this can be your top 5 at this current moment or consistently throughout all the time you've been a peter lorre fan. Maybe both if the lists are different enough)

An excellent question! I'll try to pick some top favorites, though it may be hard to choose!

Dr. Einstein, Arsenic and Old Lace. I have to put him high on the list because for one, he's so darn cute, but for another, he was responsible for starting my obsession in the first place. Peter played him absolutely perfectly with a truly sad pathetic quality that I've never seen in any other adaptation. From the moment he appeared, he was instantly my favorite character and I had to know more about the actor.

Hans Beckert, M. On the other end of the scale, it's the frightening role that made him world-famous, and it's not hard to see why. Hans is an endlessly fascinating character to me. We as the audience barely know anything about him, and yet we don't really need to. I consider the ambiguity vital to the story and it's something that later adaptations wrongfully try to erase. But the killer just is. He has committed unspeakable acts and yet he inspires our sympathy because he cannot prevent himself. Why? It doesn't matter--no reason will ever bring the children back. I have seen this film too many times and it frightens me and I love it.

Professor Koenig, Hotel Berlin. I always thought his big scene with Helmut Dantine was one of the most heartbreaking things in a film at that time. The war was grinding to an end, Koenig had suffered much at the hands of the Nazis, and he was more than ready to end it all if only he could summon the will to do it. His cynicism, ironically, may have been the only thing keeping him together, which spoke to me years ago as a cynical student, and still does as a cynical adult.

Polo, I Was An Adventuress. I always thought it was amazing that Peter could express the darkest parts of the human soul, and then turn around and play the exact opposite with seemingly no effort at all. Polo is a delight! He is a dear little sweetheart who deserves all the sugar lumps and I couldn't even be mad at him if he stole from me.

Dr. Rothe, Der Verlorene. I had wanted to see this film for decades. Literally. It just wasn't available to me for so long. When I finally got my hands on the restored DVD, I was blown away. It's a masterpiece, plain and simple. Rothe is like death itself: dark, complex, compelling. The whole film is a hard, accusatory look at Germany in defeat and the twisted circumstances that brought them there.

Thanks for this question! It wasn't easy picking only 5. :)

#peter lorre#asks#my choices are either absolute fluff or the dark abyss but I've always been that way#I am of two minds about practically everything

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Lorre on the left in this atmospheric scene from "M", 1931.

#even just standing there he's so present#peter lorre#M#hans beckert#1930s movies#german movies#peter lorre movies

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

CUE "DÜSSELDORF MONSTER" BY CHURCH OF MISERY FOR THIS ONE.

PIC INFO: Resolution at 1280x1832 -- Spotlight on an Italian movie poster for the 1960 re-release of the groundbreaking and crirtically-acclaimed crime thriller "M" (1931), (renamed "The Monster of Düsseldorf), co-written & directed by Fritz Lang. Artwork by Niso "Kremos" Ramponi.

FILM/POSTER OVERVIEW: "Inspired by the crimes of a real-life murderer at large in Düsseldorf, Peter Kürten, German director Fritz Lang created yet another classic that ventured outside the normal bounds of early filmmaking, and laid the foundations for a whole new genre in the process. Peter Lorre gave the performance of a lifetime as child killer Hans Beckert, a part specifically written for the actor by Lang himself.

Despite it being his first ever starring role, Lorre's bone chilling performance disturbed audiences and enthralled critics, gaining international praise and the attention of Hollywood. Lang considered this picture his greatest work, a well-earned distinction considering its instrumental influence on the burgeoning film noir genre."

-- HERITAGE AUCTIONS (movie posters)

Source: https://movieposters.ha.com/itm/crime/m-unitis-1960-first-post-war-release-italian-4-fogli-55-x-78-niso-kremos-ramponi-artwork/a/7162-86012.s?ic4=GalleryView-Thumbnail-071515.

#FritzLang'sM#FritzLang#M1931film#M1931#MforMörder#CrimeThriller#MMörder#GermanExpressionism#M#EuropeanCinema#GermanCinema#Cinema#Expressionism#Germanfilm#Mfilm#Movieposter#VintageIllustration#Illustration#Italianmovieposter#1930s#Posterart#ProtoNoir#Protofilmnoir

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm learning about the production behind M and something I find interesting is that Fritz Lang specifically had Peter Lorre in mind to play Hans Beckert after seeing him act onstage, but the thing is he always played these comedic minor roles and it was subversive at the time that the killer would be this unassuming sort of guy because as much as that trope is milked by today's standards back then murderers were like, mustache twirlers. But anyway, the mental picture of this well established film director seeing this doe-eyed babyfaced man go onstage and be silly in a play and being like "he would be PERFECT as the child killer in my movie!" is so funny to me

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serial Killers: The Reel and Real History

“Serial killing, contrary to popular belief, was not a product of the twentieth century. The figure of the serial killer in American culture has been noted as far back as the American Revolution, with the Harpe brothers of 1790s Tennessee possibly falling into the category. Such a lengthy genealogy, however, misses the fact that the serial killer, as a phenomenon, became popular in cinema, in films that explored killing in graphic and unique ways on-screen.

But American gothic literature and other earlier forms do provide a necessary background for reading the serial killer as a particular instantiation of American gothic. The gothic writings of Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne, especially, prefigure this phenomenon by pointing to the darkness within protagonists who struggle with fractured psyches and personal damnations, leading them towards murder and the macabre.

Unlike European gothic excess, where ruins and dark secrets lead to terrible acts of depravity and murder, often as a response to Catholicism and repression, American gothic turns inward: serial killers in fiction and film tend to be the product of deeply destructive psychological fractures: madness that masquerades just below the surface of everyday normalcy.

Serial killers act out impulsive and buried desires that have been unleashed – recalling the split gothic self of Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde (1886) or Edgar Allan Poe’s unreliable murderous narrators in ‘The Black Cat’ (1843) and ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ (1843) – filtered through a ferocious, destructive individualism, spawning countless screen and literary imitators.

This rooting of the serial killer as a psychological product of ‘cultural damage’ or ‘wound culture’, as Mark Seltzer describes, is an important feature if we are to claim modern serial killer cinema as a product of American fascination with violence, excess and psychological trauma. This psychological trauma also serves as a larger allegory for the nation.

Through the history of cinema, we have witnessed the evolution of the serial killer, from folk tales to news coverage of real murderers, towards the contemporary valorization of the serial killer as a form of celebrity in the American popular imagination. Monsters have moved from the margins to the centre of our world, and it is through the collapse of these boundaries, previously separating them from us, that serial killers have become distorted mirrors of ourselves.

Serial killers regularly feature as a form of the Other that lies just beneath the facade of the normal in our world. The terror of their aesthetic normalcy, of blending in, is central to understanding their invisibility. Yet serial killers on-screen, much like other filmic monsters such as the zombie and vampire, have evolved beyond their earlier perceived fixed states; unlike these monsters, serial killers have always worked from within society itself, and hide their chimeric faces amongst the crowd.

The fixation on the psychological is thus foundational to the modern, cinematic serial killer. The image of, and psychologized concept of, the modern American serial killer is largely shaped by the notorious figure of Ed Gein from Plainfield, Wisconsin. Gein’s case, which came to light in 1957, included cannibalism, necrophilia, skinning his victims, grave robbing and decorating his home with body parts of the deceased; it is still figured as a shocking account of desecration and sexual perversion nestled within a small rural farming community.

Gein’s case featured in Life magazine (2 December 1957), complete with pictures of his filthy home, bringing the case to national attention, and it subsequently became inspirational for numerous screen depictions of serial killers. Gone was the suggestive European strangeness of Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), from Fritz Lang’s M (1931), and his ilk; American serial killers were now found and made in the homeland of Middle America.

Though Gein was certainly not the first American serial killer since the inception of cinema – H. H. Holmes is believed to have committed at least thirty murders in his gothic ‘Murder Castle’, a labyrinthine hotel which housed unsuspecting visitors to Chicago’s World’s Fair in 1893 – Gein remains, without doubt, the most influential on contemporary film.

He has become ‘multiply interpretable’ (Sullivan 2000: 45) and unfixed, repeatedly cited, re-imagined and revisited as the touchstone in serial killer narratives for its shocking and abject content. While Gein was a partial inspiration for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Silence of the Lambs, to which we will return, perhaps the most famous fictional adaptations inspired by his case are Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, Psycho, and its 1960 screen adaptation of the same name, directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

Bloch’s novel and Hitchcock’s film both explore psychological trauma and murderous insanity through motel manager and taxidermist Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), an outwardly odd but passive man subject to the whims of his demanding, neurotic mother. That ‘mother’ and Norman are revealed to be one and the same ties Psycho very closely with contemporaneous thought on psychosexual dysfunction, expressed here as a violated and consumed psyche, and murderous impulses.

Beyond the psychological, Psycho is also the most infamous American film to align serial killing with a psychotic break from reality into a realm of fantasy and consumption, a pairing that finds its material echo in the proliferation of serial killer cinema. Alongside the post-Psycho rise of the slasher film of the 1970s and other representations of excess, serial killer cinema came to dominate in later years by sequelization, commodification and blatant imitation.

As Brian Jarvis notes, there are numerous types of serial killer films, which cross-pollinate into other film genres, which ensure their endurance: Serial Killer cinema has many faces: there are serial killer crime dramas (Manhunter (1986), Se7en (1995) Hannibal (2001)), supernatural serial killers (Halloween (1978) Friday the 13th (1980), Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)), serial killer science fiction (Virtuousity (1995), Jason X (2001)), serial killer road movies (Kalifornia (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994)), . . . postmodern pastiche (Scream (1996), I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)) and even serial killer comedies (So I Married an Axe-Murderer (1993), Serial Mom (1994), Scary Movie (2000)) . . . the serial killer has also become a staple ingredient in TV cop shows (like CSI and Law and Order) . . . (Jarvis 2007: 327–8)

Serial killers are now so ubiquitous as to be commonplace within multiple genres; indeed, they may even feel clichéd or tired as a metaphor for American malaise. Yet, there is something distinctly uncanny about their generic endurance and destructive individualism that is wholly bound to the foundations of the American imagination.

Thus, following Psycho, popular serial films of the mid to late twentieth century have linked psychological disturbances, murderous sexual desires and consumerism run amok; these connections give rise to at least a cursory understanding of the direct connection between what is represented as the serial killer’s compulsive desire to kill again and again, and the larger culture that pours over the minutia of the killers’ lives, their methodologies, and victims’ wounds and corpses.

Seltzer notes, ‘Serial killing has its place in a culture in which addictive violence has become a collective spectacle, one of the crucial sites where private desire and public fantasy cross’ (Seltzer 1998: 253). However, the source or drive of this compulsion has varied substantially on screen from 1960, from sexual deviance to expressions of psychosexual rage, social and economic exclusion, and political and cultural articulations on greed and consumption, through to representations of class, intellect and taste.

More recently, a near superhero status has been conferred onto twenty-first century serial killers through a highly problematic code of ‘morality’, which allows them to operate and thrive amongst the masses as near guardians of justice. That serial killers are hugely popular in film is unsurprising – those who cross moral boundaries are more interesting and appealing on-screen than those who strive to defend and delimit them.

The fiction of presenting an embodiment of evil – one that looks like us – contains enormous narrative appeal, and acts as a framing device by which we encounter, experience and eventually contain the psychological or consumerist cultural threat (temporarily) through a filmic frame. Contrary to the majority of film representations of serial killers in American cinema, real serial killers have been documented by reporters, psychologists and biographers as bland interfaces, rather than the monstrous figures we imagine.

The banality of real-life serial killers in the face of such terrible deeds is in itself uncanny, as we desire the binary equivalence that they must be wholly different and separate from us, entirely other in some capacity, in order to act out in such extreme and violent ways. As Nicola Nixon notes:

The real . . . Gacys, the real Bundys or Dahmers, unlike the charismatic gothic killers of, say, Thomas Harris’s recent fiction, are deeply dull and blandly ordinary . . . it is precisely their ordinariness, their characteristic of ‘sounding like accountants’ and being employed in low-profile ‘unexciting’ jobs like construction/contracting, mail sorting, vat mixing at a chocolate factory that makes their crimes seem all the more shocking. (Nixon 1998: 223)

The conjunction between the real-life serial killers who dominated media in the 1970s and 1980s and film representations of charismatic figures and their shocking crimes all becomes blurred when an uninteresting, and distinctly un-cinematic, blank central figure is unmasked – the killer must be made visually interesting yet abject in order to match the gravity of his crimes and transgressions. Abhorring the narrative vacuum that reveals the true banality of evil, serial killers on-screen must present some depth and command attention if they are to contain, reflect or represent our collective cultural fears.

Gothic monsters in fiction tend to mask their nightmarish selves by exuding charm, intellectualism and depth to lure unsuspecting victims. This is the fictive construct projected onto serial killers, which in turn contributes to their on-screen appeal, in that ‘gothic paradigms allow for the creation of a compelling narrative and consequently the generation of character and plot out of “bland ordinariness” and incomprehensible randomness’ (Nixon 1998: 226).

- Sorcha Ní Fhlainn, “Screening the American Gothic: Celluloid Serial Killers in American Popular Culture.” in American Gothic Culture

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Lorre character related questions I think about a lot

•Did Herman let Elaine go on purpose when Jonathan made him take her to the cellar?

I've always wondered since not only does Herman seem so hesitant to harm her, but neither of them seem like there was much of a struggle between them while they were in the basement. Plus, with Elaine not escaping till after Mortimer and the aunts showed up, it's possible Einstein heard their voices upstairs and saw it as an excuse to let Elaine go without Jonathan being able to just throw her back in

•Was Hans Beckert telling the truth about not being able to control his urge to kill and feeling disgusted with himself for his crimes?

Perhaps it takes away some of the films complexity, but I'm partial to the idea that Beckert isn't as haunted by his actions as he claims to be. I feel like the only negative emotion about his crimes Beckert displays before he's caught is a fear of getting caught and every step he takes in finding a victim seems intentional and done in a sound state of mind. Not to mention, as others have pointed out, the letter he sends the police and infamous mirror scene make it seem like he enjoys his reputation as a killer

•Was Roderick remorseful for murdering the pawn broker?

I wanna say yes because he's one of Petes few leading man characters and there are enough moronic critics from around the time who vastly overestimated how much of a villainous character Rod was just because he was played by Peter Lorre and killed someone. But if I'm being honest, I don't feel he was all that guilty, at least not after the night of the murder. Again he seems more frightened of being caught than guilty to me. But on the other hand he's obviously shown to be sensitive and compassionate in general in the film so perhaps its just unrealistic to assume he wouldn't feel at least some guilt for taken a life? I really go back and fourth on this one

•What is Professor Fenningers real name?

I've guessed Moritz Veidt in the past

•What is Mr Munseys first name?

I've heard 'Henry' here and there as a potential first name for Prentiss, but I don't believe I've ever heard one for Munsey. I personally like Rudolph Munsey. 'Rudy' to those he's close with

•Is Cairos hair naturally curly?

I prefer to assume it is, but it works either way for me if you have an interesting enough HC about why he chooses to curl his hair

•Who is the Emily, that Dr Lorentz mentions a few times?

I feel like I heard someone suggest that she's Arthurs sister once, but I prefer to imagine she's Arthurs maid or housekeeper. Specifically a very underpaid, world-weary, unlucky, chainsmoking one who hates her job and Arthur and Arthurs cat(who hates her back and goes out of her way to make Emily's job harder) and Arthurs crazy boyfriend and the bickering straight couple that lives in Arthurs crazy boyfriends attic and her life

Well that'll do for now. Feel free to add more questions or throw your two cents in about any of these. Or don't. You're your own person with your own agency. I assume

#peter lorre#the maltese falcon#joel cairo#arsenic and old lace#herman einstein#the boogeyman will get you#dr arthur lorentz#emily#the left fist of David#mr Munsey#m#hans beckert#youll find out#professor karl fenninger#crime and punishment#roderick raskolniknov#this was fun i should make lists of my general unanswered questions for each of petes films#i have a lot of questions about other characters and aspects of petes films that dont specifically have anything to do with him#like that question i posed a while back about why jonathan doesnt seem to feel pain#or whether or not spade and o Shaughnessy really had feelings for eachother and if so to what extent for each of them#not to mention questions about characters from petes radio plays#i had one about the character from the horla that i cut because this post is already so long and im so sad i couldnt fit it in here#professor nathaniel billings#elaine harper brewster#mr Prentiss

10 notes

·

View notes