#and also explicitly mentioning socialism is counterproductive

Text

You know that Chris Fleming line that goes "Call yourself a community organizer even though you're not on speaking terms with your roommates"?

I honestly think every leftist who talks about the "revolution" like Christians talk about the rapture needs to spend a year trying to organize their workplace. Anyone who sincerely talks about building a movement so vast and all-encompassing that it overwhelms all existing power structures needs the dose of humility that comes with realizing they can't even build a movement to get people paid better at a badly run AMC Theaters where everyone already hates the manager.

#method speaks#union stuff#politics#i guess#best case scenario in this plan we get some successful union drives#worst case people realize that movement building is hard#and also explicitly mentioning socialism is counterproductive#mostly i'm just venting#it's only april how is election discourse this unhinged already?

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Make Ralsei Say Heck No (Part 2)

As specified in Part 1, it’s quite odd Ralsei is so cooperative, submissive, and eager to help Lightners even when not explicitly asked to do so. He practically can’t say no, even to absurd or outrageous demands.1 Even to Susie, it takes a while for him to become the slightest bit assertive, visibly frustrated with her, or otherwise non-apologetic and submissive.

Why is this so?

Option 1: Lack of a Choice

Ralsei may believe he has no choice but to be a Delta Warrior, so he must act as hero-like as he can. He apparently thinks hero-like behavior is cooperative, polite, and peaceful, at least relative to Susie’s aggression.

To Kris, he says:

“As heroes we have the power to make a peaceful future. So from now on let's try to avoid FIGHTing OK?”

Later, after listing three instances of Susie’s aggression and how bad it was, he tells Susie:

“Susie...Whether you like it or not...You're a hero. One with the power to bring peace to the future. Could you please start... acting like one?”

Furthermore, he strongly believes getting by without fighting will ensure a happy ending to their tale, and if not, the result will not be “favorable”. Ralsei therefore might think he must be the best hero possible to ensure the best ending, or perhaps to ensure a happy ending to the tale at all.

Counterpoints

As much as he talks about non-violence, he does goes along with Kris’s orders, even if it’s to beat up people not even affiliated with the Spade King’s armies. Regardless of whether he beats people up, he remains polite and cooperative.

Option 2: Delta Warrior at All Costs

It’s also possible Ralsei believes he does have a choice to be one of the Delta Warriors, as a “prince from the dark”. He believes serving Lightners is the only way for Darkners to feel truly fulfilled, and Seam and the Spade King corroborated part of Ralsei’s claim. Ergo, being one of the Delta Warriors would not only let him assist Lightners, but be able to interact with two of them a lot, and so feel very fulfilled.

However, Ralsei isn’t the only “prince from the dark”: there’s also Lancer. (If he didn’t know that at the beginning, he surely learns it early on in the journey.) More specifically, as Lancer has actual subjects, he has a greater claim to the position. If Ralsei makes himself a valuable, pleasing party member, Kris and Susie won’t go searching for other princes from the dark.

The interpretation is suggested in the following dialogue:

Lancer: Just walking along with you guys...Feels nice. Like I'm doing something... important.

Ralsei: That's because you're alongside the Lightners, Lancer. Our purpose—Darkners' purpose—is to assist them. It's the only way we can feel truly fulfilled.”

Strangely, Ralsei doesn’t exactly look happy when he says “It’s the only way we can feel truly fulfilled”, suggesting his desire is deeper than just wanting a fun adventure.

Option 3: Friend Desperation

Overlapping with Option 2, Ralsei may be so desperate to be friends with Kris and Susie that he doesn’t have any boundaries or social standards. In fact, he says: “I've been waiting alone here...um...my whole life for you two to arrive. So...I'm really happy to meet you.”

Though Ralsei would logically be friends with the other Delta Warriors, his sheer conflict avoidance suggests he thinks he has no other options. It might be something like “country niceness”: when a countryside kid has only ten playmate options, alienating any of them is a big loss, necessitating extra-polite behavior. Most of the time, he acts as helpful as he can, deferring to Kris’s judgement. If “...” is selected when he talks to Kris before exiting through the great door, Ralsei says: “Kris in the end what you choose is up to you. As long as you're happy with it I'm happy too.”

Furthermore, he obeys even strange commands, such as Kris telling him to “offer his services” to Lancer and Susie during a fight with them. (he offers to braid hair) Most worryingly, in the first Lancer encounter, Ralsei even says he’ll “protect the heroes with my life!”. 2

Oddly, Ralsei is helpful even when his teammates are mean to him or go against his beliefs. Although Susie is consistently aggressive, uncooperative, insulting and otherwise rude, Kris, too, can be mean to Ralsei. (dropping the manual, attacking the dummy repeatedly, making Ralsei eat the stump salsa) Though Ralsei points out multiple times that “FIGHTing is unnecessary in this world” and he believes it will give an unfavorable ending, he nonetheless obeys Kris when told to FIGHT, and even equips the Ragged Scarf, which improves his fighting ability.

He might act strange to Kris and Susie not only because they’re his only (even first) friends, but also “cool kids” he puts on a pedestal. After all, Kris and Susie aren’t simply two people his age who arrived in the kingdom, but two Lightners, worshipped like gods, who he believes are the prophecized “heroes of light”.

This contrasts with his blunter behavior to Lancer. After he attacks with two Hathies, Lancer asks how much money he gets after the battle, and Ralsei says he doesn’t get any because he lost. He also acts unusually blunt when pointing out Lancer hasn’t made the thrash machine yet: although he’s talking about something both Lancer and Susie were working on, he was addressing Lancer.3 One of the few times Ralsei is gets angry is when Lancer taunts Ralsei on the swear-word name of their team, as he tells Lancer: "OK, fine! We can keep the name! I just won't say it." However, there’s also a time he was clearly, loudly angry at Susie: on the third post-designed machine encounter, (see video) Ralsei says: "Fine!!! We don't want to be bad guys!!!" (with three exclamation marks, even)

Counterpoints

Although Lancer is not one the “cool kids” (if that’s synonymous with Lightners), Ralsei’s different behavior towards him might not have anything to do with him being a Darkner, less cool, or less suitable for friendship. Ralsei might act differently to Lancer because he’s an obstacle to their goals, annoys them, or mocks them. Rouxls Kaard himself describes Lancer as “more annoying than a fistful of fleas!” and a “strange and irritating darling”.

Option 4: Crush on Kris

Ralsei might be so obedient and eager to please because he has a crush on Kris. According to Kidshealth, people might feel shy, giddy, or both around a crush. Concerning giddiness, he believes Darkners can only feel true fulfilment by serving Lightners, and he is quite eager to serve Kris. Concerning shyness, Ralsei acts submissive, polite, eager to please, and shy or socially-anxious around Kris. As mentioned in Option 3, he says: “Kris in the end what you choose is up to you. As long as you're happy with it I'm happy too.” His submissive-polite speech pattern could indicate nervousness around his crush, and a lack of experience with his feelings and how to act around crushes. Social inexperience is quite plausible: he has barely, if ever, socialized with anyone, since he says he’s been “waiting his whole life for” Kris and Susie, alone in his castle.

At multiple points, Ralsei blushes or acts lovestruck while Kris is physically affectionate or complimentary to him. He blushes when Kris hugs him in the battle tutorial against the dummy. He also blushes when Kris gives the White Ribbon to him, and he asks Kris if he looks pretty. (If Susie’s in the party at that point, he still blushes, but asks Susie instead) More convincingly, when Kris stands really close to Ralsei, Ralsei blushes (but doesn’t ask Kris to move) and when Kris repeatedly attacks the dummy, Ralsei says it’s okay if Kris attacks him, too. (while also blushing) He also amusedly says Kris doesn’t need to donate to the tutorial masters to get him to call Kris “honey”, and that's something married couples, not friends, call each other.

He is also polite, submissive, and waffling to Susie, cares a lot about her, wants her on the team, and goes along with her plans when it’s not outright counterproductive (e.g., being launched at K. Round). However, he still treats Susie differently: he doesn’t blush when talking to Susie, nor does he anticipate Susie’s needs as he does for Kris. (The closest he gets to that is mentioning he “WAS going to bake a cake later” when Susie alludes to her hunger over three sentences.) This suggests he doesn’t have a crush on Susie, too.

It’s likely that this crush is combined with putting Kris on a pedestal or being intimidated by then. Seam says “[Lightners] were like gods to us.” and the Spade King continues with the godlike characterization, telling Ralsei to “perish with the pathetic Lightners you worship!” An NPC also points out the Delta Warriors took the Ragged Scarf in the chest without even asking, and claims it's a "gift to help you defeat the KING!" but also points out they're "potentially criminals". When Kris does the wrong thing, such as repeatedly hugging Ralsei in a combat tutorial, he might be too intimidated to say no, especially for harmless actions. Furthermore, Ralsei might lack integrity or feel insecure at the start, making him especially socially malleable.

Counterpoints

Though blushing in certain circumstances (e.g., saying Kris can hit them) could indicate Ralsei is lovestruck and possibly a masochist (see below), blushing can also show shame or anxiety. Therefore, Ralsei might blush when saying Kris can hit him due to his anticipation of Kris’s needs and inability to say no combining with discomfort on the matter.

It’s unclear whether he enjoys being hugged in general, hugged by people he likes, or specifically being hugged by Kris. After all, he said he’s never hugged anyone before, so he, logically, would never have been hugged back.

Option 5: Social and Physical Masochist

It’s possible he actually likes some combination of getting hurt, insulted, or bossed around, as well as serving Lightners. This is unusual: other Darkners also respond unhappily to getting hurt or insulted, such as Jigswaries getting attacked by Susie or Susie being mean to Bloxer. Even Lancer, as much as he likes Susie, doesn’t act submissive or servile towards her. There’s no evidence Lancer likes getting bossed around or insulted, and he doesn’t like getting hurt. Lancer even imprisons Susie to prevent her and the other Lightners from fighting (and potentially killing) his dad: Ralsei never poses such an obstacle.

Although the Rudinns are unhappy fanning Susie and Lancer, Ralsei offers to fan Kris just in case they’re envious of an evildoing lifestyle. If Kris throws away the manual, Ralsei offers to make a better one next time. The biggest piece of evidence is that, when Ralsei says it’s okay if Kris hits him, Ralsei blushes.

This is one of the less likely interpretations. Although he has a strangely high tolerance for others being mean to him, he does eventually ask Susie to stop being mean to him. However, he’s still a pushover: he entices her into simply being nice to him on a journey to save the world by offering cake, rather than for the sake of decency.

Option 6: Slightly Insane

Mental disturbance is another less likely possibility. After all, Seam says “Around here, you learn to find ways to pass the time...or go mad like everyone else.” If Seam is right, descending into madness is a risk for Darkners, so Ralsei could be mildly insane.

Still, even without supernatural explanations, his behavior and beliefs could easily become erratic if he was alone in the quietude of his castle for long enough, especially without a variety of fun activities. Seam may describe the Dark World as a “prison”, but Ralsei’s kingdom is a prison within a prison: except for two hedges in the tiny Castle Town, there apparently aren’t any living things there but him. Even hermits have richer nature surroundings, and animals for company. Yet, unless Ralsei climbs a cliff to the starting zone to meet with the spoon-like hazards and the sleeping dust lumps, he doesn’t even have animals: just the dummy based off himself.

Conclusion

Although there’s definitely something psychologically weird about Ralsei, it’s hard to figure out what, since there are many ways to interpret his behavior. Some explanations can even be combined: he could, for example, be happy about inevitably becoming a Delta Warrior, solitude eroded his social boundaries (if he ever had any), and he’s simultaneously in love with and intimidated by Kris.

There’s not enough data to say which interpretations are true, or how many, or to what extent. But one thing’s for sure: Ralsei ought to put up some boundaries and say “heck no!” a lot more.

If you enjoyed this post, you may be interested in the author's Patreon and Ko-Fi.

Related Reading

Flowey and PTSD series (also analyses the causes and symptoms of strange behavior)

When the Spade King tells him to "perish with the pathetic LIGHTNERs you worship", Ralsei says: “Sorry, but we’re not going anywhere!” Even when responding to the villain of the story who wants to kill him, he sounds almost apologetic. ↩︎

He says this as if he’s not a hero himself. It might mean he knows he's a not one of the prophecized heroes, or that he doesn't have have a high opinion of himself. ↩︎

Lancer: The WHAT machine?

Ralsei: The machine... ? We had a whole sequence about it...?

Lancer: Oh that. Yeah we'll make it at the last minute.

Ralsei: You two should REALLY start working on it earlier...

↩︎

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

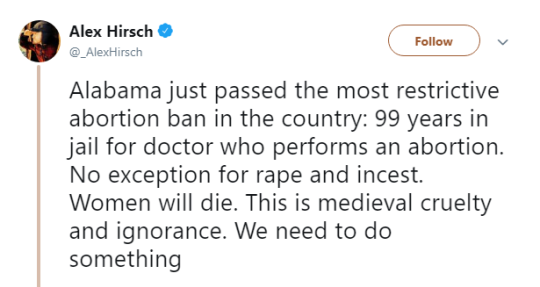

Women and “medieval cruelty and ignorance”

Okay. So. We could probably have guessed that this tweet was like waving a red flag in front of a bull, but here we are anyway.

(Tagging @artielu because I know she enjoys my history smackdowns and this is right in her wheelhouse of interest.)

First: nobody denies that the Alabama bill and similar efforts are absolutely heinous, are designed to be test cases to get Roe v. Wade overturned, and are deliberately gratuitous in their constitutional overreach and general horrible Handmaid’s Tale nature. But for well-meaning liberals, such as above, calling them representative of “medieval cruelty and ignorance” is a) not accurate and b) counterproductive. If we insist on using “the medieval” as a conceptual category inferior to “the modern,” these recent bills bear a complicated, at best, resemblance to medieval canon law and social practice. And there was never, I promise you, any law that prescribed a 99-year jail term for abortionists. So if we want to point out how the modern Republican party is actually much worse than their medieval counterparts, we can do that, but also: trust me, this is thoroughly modern cruelty and ignorance, and we should insist on that distinction.

First, obviously, women’s bodies have always been subject to a social discourse of power, control, gendered anxiety, and attendant responses. This was certainly the case in the medieval era, but our modern interpretations of that discourse can be... iffy, at best. In discussing the feminization of witchcraft in the late 15th century, M.D. Bailey critiques how scholars have tended to take the Malleus Maleficarum, the famous witch-hunting handbook, as representative of a self-evident and endemic medieval and clerical misogyny. In fact, the Malleus was the equivalent of the extreme right wing today, was relatively quickly condemned even by the church itself, and was largely reworked from earlier ecclesiastical anti-sodomy polemics, because the idea of “disordered gender” was certainly one that occupied medieval moralists and theorists. I have discussed the Malleus in other posts, but while it certainly is virulently and systematically misogynist, it also was a work of rhetoric rather than a reflection of historical reality. Medieval misogyny absolutely and obviously existed, and it impacted women’s lives, but we also really need to get rid of The Medieval Era Was Bad For Women, (tm), Therefore Everything Was Worse Back Then.

The possibility of magic being used to cause impotence/loss of fertility was another concern, and one of the main anxieties about the practice of witchcraft was that it would bring “sterility” and irregular sexual activity (usually with the devil). However, an extensive corpus of contraceptive and abortifacient knowledge has existed since antiquity, and in tracing the representation of unborn children in medieval theological thought, Danuta Shanzer notes:

My findings suggest that it is overstatement to claim that from the start Christianity considered the fetus a living being from conception. Augustine is a major agonized and agnostic counter-example.

Hence, contrary to right-wing claims that the church has “always” thought that life began at conception (spoiler alert: the church has never once “always” thought the same thing on anything), it was almost never the case in medieval legal or theoretical practice. Thomas Aquinas and other medieval theologians argued that “ensoulment” or the separation of the fetus into a living being happened at quickening, when the baby could move on its own (which medieval medical treatises had various standards for measuring, but it would be the equivalent of about 20 weeks of pregnancy). Monica Green, a leading medieval medical and gender historian, has examined a vast corpus of obstetric and gynecological Middle English texts, and in “Making Motherhood,” argues:

Texts on women’s medicine might also be concerned to “unmake” or prevent motherhood, either by preventing conception in the first place or expelling a dead foetus that would not emerge spontaneously. Abortion per se was almost never mentioned.

In other words: abortion was not paid attention to in nearly the same way we do today, and while canon law, in theory, prescribed penalties for contraception and abortion, historians have consistently (surprise!) discovered a disconnect between this and secular law and everyday practice. And while some twelfth-century (male) jurists did attempt to equate miscarriage with homicide, and to install it in canon law, these laws were almost never practically used or prosecuted. In Divisions of Labor: Gender, Power, and Later Medieval Childbirth, c. 1200-1500, Rebecca Wynne Jones surveys the extant literature and notes:

In his 2012 book The Criminalization of Abortion in the West, Wolfgang Müller documents how 12th‐century jurists' increasing tendency to equate violence resulting in miscarriage with homicide was institutionalized in canon law. Though this development led to the widespread criminalization of abortion in ecclesiastical jurisdictions, Müller has little to say about gender relations on the ground. Rather, by highlighting local communities' reluctance to prosecute, he presents laws that might once have been seen as proof of a medieval “war on women” as legislative enactments whose practical power remained limited.

Once again: medieval ecclesiastical proscriptions against abortion were, at best, sporadically enforced, communities were reluctant to actually prosecute women or to criminalize early-term pregnancy loss, and church law was not identical with secular law, which was the standard ordinary people used and were subject to. This concords with what Fiona Harris-Stoertz has found in her survey of pregnancy and childbirth in twelfth and thirteenth-century French and English law:

It is striking that in these thirteenth-century English texts, no penalty was assigned for the loss of less developed fetuses. This absence flew in the face of high medieval church legislation, which, in theory at least, took all contraception and abortion seriously. John Riddle finds that the idea that early-term abortion is less serious than late-term abortion occurred in the work of Aristotle and appeared occasionally throughout the early Middle Ages, particularly in church penitentials, although it also appeared in the early medieval Visigothic code.

While late-term abortion of potentially viable fetuses was still a crime, secular law still essentially held to quickening as the moment at which a pregnancy could not be terminated. Before that, however -- anywhere in the first 4-5 months of pregnancy -- it could often be dealt with, if desired, without any penalty. Anne L. McClanan has investigated the material culture of abortion and contraception in the early Byzantine period. And Ireland, which as recently as last year remained one of the last European countries to outlaw abortion, had a medieval hagiography that actively canonized abortionist saints:

Medieval hagiographers told of Irish Catholics par excellence, the saints themselves, performing abortions as well as of “bastards” becoming bishops and saints. In hagiography and the penitentials, virginal status depended more on a woman’s relationship with the church than with a man. To my knowledge, no other country in Christendom, medieval or modern, produced abortionist saints or restored virgins, apart from the nun of Watton. Why Ireland is among the few European countries to maintain severely restrictive policies on reproduction remains an unanswered question, but it clearly cannot be attributed to its medieval Catholicism.

Last part bolded because important. Modern bans on abortion don’t relate to how these notions were conceptualized or used in the past, and they are not holdovers from The Medieval Era (tm). They don’t represent medieval concerns or medieval ideas of gender, or at least certainly not in a direct genealogy. Even as late as the seventeenth century, when ideas of childbirth, marriage, and reproduction were more strictly controlled, the period prior to quickening, or the movement of the baby, was still generally not penalized or subject to legal control or coercion. So in sum: while religious moralists and canonical lawyers absolutely did object to abortion (aka right-wing men, the same ones who object to it today, funnily enough), in secular law and daily practice, a pregnancy that was terminated prior to quickening was not subject to practical prosecution or legal punishment, and medieval women had access to a vast corpus of gynecological texts, medical practices, herbal recipes, rituals, and charms intended to accomplish a wide range of fertility goals: conception, contraception, abortion, a healthy pregnancy and delivery, and so forth. I also answered an ask a while ago that discussed all this in detail.

Also: abortion was explicitly mobilized as a wedge issue in the 1970s and 1980s with the rise of the religious right in American politics, and that happened not because of abortion, but in resistance to the IRS penalizing them for refusing to racially integrate evangelical schools and colleges. Randall Balmer has written about the history of the “abortion myth”; do yourself a favor and read it. The Southern Baptist Convention campaigned in 1971 for the liberalization of American abortion laws, and hailed the 1973 Roe decision as a win for the rights of the mother. (Oh how the mighty have fallen?) The right wing came together as a political force to resist racial integration, exemplified by their loss in the 1983 Supreme Court case Bob Jones University v. United States. But since it was not a winning political strategy (yet, at least) to fly the flag of “let us be racist in peace,” they, as Balmer discusses, created the “abortion myth” to make themselves look better and to present a narrative of holy/moral concern for the lives of the unborn. The reason abortion is as huge as it is in the present American political landscape owes to modern religious conservatism and extremism, resistance to racial equality, ideological control over women, and other bigotry, and (again) not to medievalism or medieval practices.

So, yes. Let us call the Alabama bill and other heinousness exactly what it is: a modern effort by a lot of terrible modern people to do terrible things to modern women. We don’t need to qualify it by fallacious equivalences to so-called “medieval cruelty” -- especially, again, when medieval practice and perspective on these issues was nowhere near the stereotype, and certainly nowhere near this “99 years in prison for performing an abortion” dystopian nightmare. If we want to shame the GOP, by all means, do so. But we should not resort to distorting and simplifying history to do it, and using the imagined “bad medieval” as a straw man to club them with. There’s plenty on its own. The modern world needs to take responsibility for its own misogyny, and stop trying to frame it as a historical issue that only existed in the past, and that any manifestations of it must be medieval in nature. Because it’s not.

#history#medieval history#women in history#history of sexuality#history of medicine#cw abortion#long post

675 notes

·

View notes

Text

Violent protest

It seems like a distant memory now, but it was less than two months ago that protests and riots were occurring throughout the country to protest police brutality against Black people in the wake of George Floyd’. It’s easy to see the situation as muddy or conflicted; while most people agree, at least somewhat, with the premise of the Black Lives Matter movement, how far is too far? Murder – especially murder sanctioned by the government and carried out according to race – is, obviously, wrong. And protesting is an incredibly powerful tool to help those of us without a large platform to make our voices heard. Rioting, however, has been largely condemned by the people who support peaceful protest. It raises the question: Can violent protest be a legitimate and justifiable method of advocating for social change?

Many chose to address this issue by saying it doesn’t really matter; when you’re talking about a system that murders people on the basis of their skin color, property destruction pales in comparison. Still, this isn’t really a discussion of the question but a rejection of it, and only allows it to be put aside until the next time . Instead, I want to try to analyze the factors that cause these issues and the ways that a violent response addresses them.

First, it is important to establish what rioting accomplishes. In general, rioting can be viewed as a violent form of protest, with most riots involving physical resistance against law enforcement, as well as looting or other forms of unorganized activity. The surest consequence of violent protest is that it attracts attention, although it’s usually negative. It can also be viewed as a protest against state control of free speech (violating orders by law enforcement to disband), and, in many contexts, more generally against law enforcement. Looting against large businesses also carries an anti-capitalist message, which is fitting as any large company is guaranteed to uphold the capitalist, discriminatory systems that make systemic racism (and, secondarily, other forms of inequality) a fundamental part of life. Although some looters are opportunistic with the goal of stealing without supporting a particular cause, it’s important to note that their actions do not, by definition, reflect the motivations of the majority, which I would generally summarize as anti-establishment, anti-government control, and anti-capitalist (at least in a sense of opposing some capitalistic control of human rights).

Now, the question has become: Is violence a reasonable and justified response to oppressive systems of government and commerce? In this case, I think the first step is to examine the violent nature of capitalist government oppression.

Violence, when used in this context, can be taken to mean, “control of choice or autonomy by physical means.” For example, laws contain an element of violence in the sense that they are, ultimately, based in physical enforcement by the police, military, or other government forces (i.e. arrest or detainment). Even if a prior non-violent warning is issued, ignoring it will eventually result in physical violence against the person in violation of the law. Capitalism operates in tandem with this form of violence, with money being a primary way to avoid being the target of violence. This is particularly clear when looking at homelessness, which is the usually-criminalized result of not having enough money — not to mention the wealthy elites who get away with much larger crimes with no legal consequences, thanks to their immense political and social power and perceived role as vital to society. In other words, capitalism provides a system of focusing governmental violence on the working class in order to protect wealthy elites and the capitalist structures that keep them in power.

Having established the violence that is used by the government as part of the capitalist system, the original question gains new context. Rather than protestors acting in senseless violence, they are replicating the same conditions of reckless violence that Black people endure on a daily basis. Seen under this lens, violent protests begin to look more rational. By looting large businesses, the protesters force themselves to be listened to (Notably, small businesses are not the criminals here, since they also lack the influence that causes these societal problems and are often victims of large corporations themselves). Violence against the police serves a similar purpose, especially when those same police are engaging in dangerous and barbaric crowd-control methods on mostly peaceful protestors. As a result, I would argue that violence, in these cases, can be a powerful tool for forcing society to pay attention to people who are usually ignored, and can hardly be viewed as the brutal, senseless violence that most news shows.

The other major argument against protests of this nature is public image. Many people claim violence is counterproductive because it ultimately discredits the movement’s message and believe it will give it a bad image. While there may be some truth in this argument, I would argue that anyone who is willing to ignore a system that intentionally criminalizes and kills Black people because someone broke into their favorite Starbucks is probably shortsighted at best, and flat-out racist at worst. It also ignores the failure of peaceful protesting to capture the attention needed to create systematic change. I think the best way to address this issue is not to stop participating in what has shown itself to be an effective means of protest, but to show why it can be the most effective option, as well as limiting violence to law enforcement (or other direct antagonizers of the protestors) and stealing to large corporations rather than extending it to civilians and small businesses, which are not the main vehicles of violence in our society. I also want to explicitly condemn the opportunistic looters whose primary motivation was not a commitment to racial justice but a desire to steal things, which contributes to viewing the movement as a self-serving attack.

Taking this into consideration, I think violence can be an appropriate response to police brutality, which is responsible for over a thousand deaths each year and kills Black men at three times the rate of white men. Peaceful protest and legislative action has failed to create meaningful change, as evidenced by steady rates of police violence and abysmally low conviction rates of officers. Although these are huge issues that won’t be quickly addressed, police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement has become a movement that attracted major attention, and efforts to defund the police have gone from a fringe issue to a serious suggestion in some cities. While these measures are still hugely inadequate to truly end police brutality, they do represent a shift from what was possible two months ago. In other words, these protests — many of which were violent — worked.

Overall, I think that the extreme violence of the government and the effectiveness of violent protest creates a strong case for its use, at least in some cases. While violence is a tool that must always be used with caution, in cases as clear and horrific as the killing of George Floyd and the hundreds of other Black people killed each year by the police, the failure of peaceful protests to create change means that more drastic action must be taken. And, to anybody who sees riots as unjustified, chaotic violence, remember that they are often the only option available to groups of people who have been systematically denied human rights. This is the context behind that Martin Luther King Jr. quote that has been going around: “A riot is the language of the unheard.” That is exactly what we’re seeing now — and to not listen is ignoring their struggles to be treated like human beings.

#blm#black lives matter#anarchist#police brutality#acab#defundhate#george floyd#fuck cops#fuck the police

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(CW: helicopter parenting mention, law enforcement mention):

So I found this post someone shared and, oh boy:

“Dear families I am begging you to listen to me. Over the last few years I have heard heart breaking stories of our young adults getting into trouble with the law in a variety of ways. The individuals with autism are usually innocent, entrapped or unaware of the situation unfolding. Several of these young adults have served time and families have lost huge amounts of money trying to protect their children from the system.

Here are my recommendations based on these families experiences.

Here is my plea:

1. Get guardianship. You can always give it up later.

2. Teach your child to reach out and use you as a resource. Teach them to ask for help even as adults.

3. Being a helicopter parent is important as we release our adults in the world. There will be a huge transition and we should be actively involved in double checking they are handling life okay and not being taken advantage of or bullied in any way.

4. Be brutally honest about your child’s strengths and weaknesses and put measures in place to help them build those weaknesses up. Set goals and really think about what tools they need and create them. Denial is not your child’s friend.

5. Understand all the technology your child uses and double check it. There are people including law enforcement on social media and playing games who may entrap your child without the child knowing they are doing anything wrong. According to Homeland Security Officer I talked to there is no privacy in any of the technology platforms and every thing is recorded.

6. Make sure to put your child thru the Be Safe Program. Be Safe helps our young adults interact safely with law enforcement. One of the issues discussed is understanding their right to remain silent and their right for an attorney. You have to understand this right to get this right and it needs to be explicitly taught.

We want our individuals with autism to be included in society but society does not always accommodate them and that is ESPECIALLY true of the legal system. I have tried for years to do trainings for courts, so far I have trained people who work within the system excluding the real people needing the training like judges and prosecutors and defense attorneys. Our Be Safe Program has made huge changes in our relationships with law enforcement but the legal system is still a train wreck. So we must be very vigilant and protect our kids!”

What. the fuck. are they thinking?

I have a lot of qualms over this. I understand that the law isn’t responsive to us or even trained to help us, but that gives no excuse to enforce what I consider to be the biggest problem of this post (besides calling us kids when talking about adults), which I replied with:

“I have some qualms over this, but there's one in particular; helicopter parenting. It's fine to be protective, but DO NOT become a helicopter parent. It's scientifically proven that those whose parents are helicopter parents are less able to handle the world. On top of that, speaking as an autistic woman who has felt like her parents have been kinda helicopter parents, it's stressful to the autistic person because it makes us feel like we always need to be acceptable. It makes us feel like we have no sense of control over our lives whatsoever and it makes us LESS likely to ask you for help about things or tell you about things like if we're LGBT+, things that we may not be quite comfortable with you knowing right away, things that we ourselves may need time to come to terms with. Like a lot of young adults who are not autistic, we're more desiring of independence and trying to develop our own identity. Hovering over your autistic son or daughter all the time will make them stressed out and perhaps lash out because even WE like our privacy. It's totally understandable that you want us to be safe and that's cool, but how are we supposed to handle the world if we can't be left to make a few mistakes of our own? In short, for big decisions, some guidance is okay, but only if they ask you. You can tell your autistic son or daughter that "hey, I know this is a pretty big decision. if you need help with anything, I'm here." If it's something huge, then maybe step in a bit. But if it's something like withdrawing money or depositing a check or going to the doctor's office, unless they say they would like help from you, please step back and let them do this themselves. You can ask them "hey, would you like me to go with you to do this thing?" but if the answer is no, then step back and respect their answer. Another important thing is to ask them what their boundaries are in terms of these things; when they give their answer, respect what they say. If it doesn't feel safe to you, then work with them on a compromise that both of you can be happy with. Not only does this give them a sense of independence and you a sense of security, but they may be more likely to come to you to ask for help because they trust that you'll keep to those boundaries you two have established.”

Also the phrase I bolded: The individuals with autism are usually innocent, entrapped or unaware of the situation unfolding.

Fuck me gently with a chainsaw. That post is another plea to treat us like helpless, innocent children. Which may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If we aren’t given AT LEAST SOME autonomy and control, we won’t know how to be independent, so this post is somewhat counterproductive to what some parents want for their autistic sons or daughters. They want us to be able to be independent and functioning adults, but by treating us like helpless, innocent children, that’s what we may start to become. Because psychology.

This is one of my main problems (out of many problems) with autism parents/NT-exclusive advocacy of autistic people; they treat us like we have no autonomy or that we can’t be independent. And, in its core, it’s one of the things the Autistic Rights Movement seems to be founded on; the idea that we CAN be independent, that we DO have autonomy, and that we ARE able to advocate for ourselves in some way. Even those who society considers to be “severely autistic” can probably advocate in some way with the right kind of help and adaptions. Because what society seems to disregard is that they are people as well, people who have opinions, people who have likes and dislikes, people who have emotions.

“Autism Parents” take them into regard when it comes to THE PARENTS AND NTs advocating over them and to argue that those of us who society considers “mildly autistic” don’t speak for them because we’re not like them, but it seems like they refuse to acknowledge them when it comes to our rights.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

my first, and possibly only, official statement on the new doctor.

i've honestly been truly and thoroughly baffled, and rather disappointed, by the lack of discussion occurring around this polarizing issue. in fact, in my brief experience on various social media platforms, discussion is rarely, if ever, allowed. the tiniest expression of discontent with the new doctor immediately elicits a slew of insults and accusations of misogyny. i have yet to have an actual conversation with anyone about this, aside from close personal friends who share my views, because those who don't share them will not even engage them. they instead immediately resort to name calling and shut down any attempts at conversation i make. honestly, it has driven a wedge between me and doctor who and its fandom like i've never experienced, not even in all my suffering through the moffat era.

i hesitated for a while about coming back on here at all. but i figured it would be wrong of me to not give my friends and acquaintances here a chance to really hear me out, since before i took a hiatus i hadn't really properly articulated my reasoning (for the aforementioned reasons). so to anyone interested in my thoughts on the matter (and let me explicitly mention here that i am referring only to rational people who are willing to either read silently and go about their day or else engage in a polite discussion with me, not people who are just going to send me vicious anonymous asks), here they are.

i’m sure it’s no surprise to any of my followers that i haven’t been actively watching the show for some time now. in fact, i stepped away indefinitely sometime early season 8, not because i had any issue with capaldi, but because i didn’t feel moffat’s writing had improved any since the last season.

so, it may have come as a surprise to many of you that i even had a strong reaction of any kind, be it positive or negative. and i can certainly see where you’re coming from, if that’s the case.

when it was announced early last year that moffat would finally be leaving, i threw a party. i literally did. i got together with my one other real-life friend who watches the show, watched rtd episodes, and made blue cupcakes (that were supposed to be TARDIS colored but turned out more of a pale teal and baby blue combo). i can’t even explain how happy i was at the mere suggestion of him leaving. because in my eyes, he took my favorite show and turned it into something i resented. it was such a slow and painful process to come to terms with the fact that a show i once loved was causing me so much grief, and finally part ways with it (at least in the sense of following along with the new episodes; i’ve obviously remained active in the rtd sect and continue to devote a significant chunk of my life to the doctor and rose *blush*). but i just couldn’t deal with the constant disappointment and rage anymore. i knew it was for the best.

i liked broadchurch well enough, with the exception of the second season, and i thought there was no way chibnall could be worse than moffat. and best case scenario, he could potentially resurrect the show into something i’d enjoy again. maybe it was foolish to hope for such a thing, but i owe far too much to this show after all it’s done for me to not give it a second chance under new leadership. so when, a few weeks ago, they told us the date they’d be announcing the new doctor, i got properly excited again. to put a face to my renewed hope in the series? it was hard not to get excited. the sound of the tardis still makes my heart swell with joy and gratitude. i’m still invested. just look at my room or my wardrobe. i’m a self-proclaimed doctor who geek through and through. if i wasn’t, i don’t think it would be possible for me to be genuinely upset about anything that happened to the show. the things we love are the things that can hurt us the most.

so, without prolonging the inevitable any longer, i’ll try to explain why i was/am upset by the casting announcement.

i really have three main reasons.

1. the issue of representation.

let me start out by saying i am a passionate advocate for better (i won't say more, because i don't think that's the issue at hand) female representation in media. especially film. i desperately want more intelligent, strong, powerful women in fiction. but what i absolutely do not want is to recycle traditionally male characters into female ones. doesn't this seem counterproductive to anyone else? its almost as though a man always has to pave the way, and only once he's established a character can a woman potentially take over. it’s trite and more than a little insulting.

give me more original female characters who kick ass. give me more natasha romanoffs, more reys, more elle woods, more leslie knopes.

don’t give me more batgirls or supergirls. don’t take a character as prominent and culturally significant as the doctor and morph him into a woman after 50+ years (or 2000+, depending on your perspective).

and you know, i've actually seen people say (addressing people who are upset about the casting): ‘a character’s gender doesn't have to match yours to be a good role model for you.’ you know what? to an extent, i actually agree. as a matter of fact, i strongly identify with and take inspiration from the doctor, even though he's a man. does nobody hear how hypocritical it sounds to say you want a woman to play the doctor purely so girls can have another role model, and then turn around and in the next sentence say gender is irrelevant to role models? yeah, this one really floored me.

but though i do think that one’s role models don’t have to match one’s gender 100% of the time, it is important to have some that do. and i do think there is an imbalance in the number of strong male leads in tv and film versus the number of strong female leads. keyword: strong. i’m tired of sexist stereotyping and failed bechdel tests, too. probably more than most, actually. but i think taking existing male characters and gender bending them is the absolute worst way to go about rectifying this imbalance.

2. the issue of the nature of gender.

i want to preface this by saying that, until fairly recently, i was something of a fundamentalist when it came to gender. but over the years, i’ve realized how problematic such views are. i’ve invested hours upon hours of my free time scouring reddit threads and watching documentaries about trans issues to understand this crucial part of the LGBT community. to learn. and what i’ve gathered from my thorough research, and heard from the many personal experiences of transgender individuals i’ve read, is that gender is something distinct from biological sex that is immutable. the gender you’re born with is the gender you are for life. (and yes, as i understand it this does also apply to genderfluid individuals - they’ve always been genderfluid even if it was not always expressed.) and changes made to physical appearance are merely affirming one’s gender, not changing it.

changing the doctor into a woman flies directly in the face of this very concept. and to me, it really, truly feels like an insult to the trans community.

it’s going back to the regressive fundamentalist view that sex = gender. that because the doctor has a woman’s body now, he must therefore identify as a woman. though this hasn’t been explicitly confirmed in so many words, given the widespread use of feminine pronouns and the term ‘woman’, i think it’s safe to conclude this is the case for the show. and this is so contrary to the whole message the LGBT community is trying to put out.

now. i’ve heard several potential counterarguments to this, so bear with me as i go through them.

first, people say ‘but the doctor is an alien, not a human. our gender expectations don’t apply.’ true. yes. he is an alien. but is the show really about his alienness? i think you’d be hard-pressed to convince me that it is. the truth is, though it’s told through tales of distant planets and creepy aliens, it’s really a show about humanity, and always has been. doctor who has always espoused a meaningful kind of secular humanism. it’s explored what it means to be human in so many impactful ways. and it’s because the doctor looks and acts human much of the time, succumbs to human emotions and has such human flaws, that he is so relatable. yes, it’s a sci-fi show about time travel and regeneration and spaceships, but if the doctor were completely alien and had no human qualities, it wouldn’t have become such a hit. don’t try to deny that. trying to distance the doctor from humanity is a detriment, not a benefit, to the show.

and though some may argue we ought to hope for and potentially work towards a future where gender is irrelevant, the fact is in today’s society gender is exceedingly relevant. and important. transgender people and feminist movements wouldn’t exist - wouldn’t need to exist - if it weren’t.

second, i see people say ‘the doctor has no gender.’ this one admittedly really throws me. no gender? where is the evidence for that?

for one thing, what point would there be to differentiating between time lords and time ladies if gender was not of import on gallifrey?

there is also a plethora of evidence to the contrary: the doctor has in fact consistently identified as a man. starting JUST with ten:

in ‘the christmas invasion’: he says ‘same man, new face. well, new everything.’

also in tci: ‘oh, that's rude. that's the sort of man i am now, am i?

also in tci: ‘no second chances. i’m that sort of man.’

in ‘fear her’: ‘look at my manly hairy hand’

in ‘evolution of the daleks’: ‘the only man in the universe who might show you some compassion’

in ‘utopia’: ‘i was a different man back then.’

in ‘voyage of the damned’: ‘i’m the man who’s going to save your lives’

in ‘the end of time’: ‘even if i change, it feels like dying. everything i am dies. some new man goes sauntering away.’

a couple of these quotes actually indicate that he has an innate sense of being a man that transcends regeneration. depending on his current level of angst, it seems, he sees himself as a different man or the same man, but the ‘man’ part remains the same. he doesn’t say ‘person’ or ‘character’ or anything to that effect. he says ‘man.’

not to mention, the doctor consistently objects to being called a human (or martian), and corrects those who mislabel him as such, but never once objects to being called a man (which is quite often).

and just so that no one accuses me of singling out one doctor too much, here’s a quote from the first doctor from the pilot, an unearthly child: ‘i’m an old man. how can an old man like me harm any of you?’

right off the bat. the doctor has been identifying as a man for literally thousands of years.

sorry for lingering on that sub-point for a while. it’s just so mind-boggling to me because there’s so much freely available evidence to the contrary.

third, i’ve noticed there seems to be some level of collective amnesia of the backlash from when the master made a comeback as missy. given what i’ve observed of people praising the decision retroactively, no one seems to remember the fandom’s response from that revelatory episode anymore. but i remember it vividly. a number of people were furious, the trans community and its allies in particular. and this outrage returned with a vengeance when missy kissed the doctor (12) later on. though i had already given up on watching the show by then (at least as long as moffat’s hellish reign continued), the anger and frustration i was seeing really resonated with me.

i have never forgotten that, and it is undoubtedly a big part of the reason i’m so angry and frustrated now. i am at least consistent, if nothing else. but conversely, there seems to be a lack of consistency among much of the fandom, as i sense none of the widespread ire from the past making a resurgence now, and it’s unclear why. the same issues regarding gender are at play. it’s leading me to assume that many people are embracing this decision purely for perceived representation, while disregarding potential cultural issues it may raise, which i think is dangerously selfish and shallow.

3. the choice of actress.

i’m not going to pull any punches here, since i’m already putting my blog’s reputation in jeopardy by making this post at all. i don’t like jodie whittaker, specifically. i think she’s a terrible actress.

this is based purely off of watching broadchurch, because it’s the only thing i’ve seen her in. but her performance paled miserably next to david’s and olivia’s, and even some minor characters’. i mean, beth’s life thoroughly sucked, and everything in it went from bad to worse for a while, but i didn’t really care. she didn’t make me care. i think that’s a huge red flag for any actor. because, i mean, compare that to olivia’s performance. i mean, SHIT. miller made me feel things every episode. intense things. and beth didn’t. at all. ever.

so, even IF the other two issues were somehow resolved, i still wouldn’t be happy with the casting choice, because i am not at all impressed with this person’s acting ability. the doctor is a huge role. a critical one. and i’m honestly not sure what she did to earn it.

so, that’s it. it’s not every nook and cranny of my position, but it’s the gist of it.

as my final thought, i’ll reiterate what i said at the beginning, to anyone considering responding to this: hostile ad hominem responses will be resolutely ignored, but (time and volume of responses permitting) polite intellectual debate will likely be engaged. but let it be said that though i’m willing to listen to reason, it’s highly unlikely anyone will change my mind.

i don’t want this to widen the chasm between me and the fandom. i already feel so distant from it already, like i’m hanging on by a thread. in all likelihood, i won’t discuss the subject at all any more after this post, save for when responding to others’ comments or questions about it. and even then, i will do so privately whenever i can. because i really don’t want to dwell on it anymore. i’ve finally sunk myself back into ep after an extended hiatus due to surgery and work, and that’s what i’d really like to dedicate my free time to from here on out. that and my other d/r fics. that’s what makes me happy; not bickering with people who don’t agree with me.

so please! feel free not to respond to this at all. it is completely optional and even somewhat discouraged, because i am tired of thinking about it and being yelled at and insulted for it. i’d love to forget about it and move on, at least until i’m forced to confront it again this christmas. i want to get back to what my blog is all about - nine and ten’s era. david. the fun smattering of friends and parks gifs. but above all else, the doctor and rose. the couple i’ve dedicated the past four years of my life to.

no matter what happens, i’m going to stay with them. whether or not i stick around on tumblr, i’ll continue posting my fics on ao3. they’re my happy place. these characters mean the world to me. and doctor who will always be very dear to my heart, regardless of how the future of the show pans out. i hope my followers never doubt that.

#please do not reblog#negativity cw#if you don't want to see it#don't read it#i know it's long#but it's me#i'm nothing if not thorough#meta#hope i don't regret this#there's also a substantial amount of anti moffat talk in here#fair warning for that too

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leo Kant & Elisabeth Norman, You Must Be Joking! Benign Violations, Power Asymmetry, and Humor in a Broader Social Context, 10 Front Psychol 1380 (2019)

Abstract

Violated expectations can indeed be funny, as is acknowledged by incongruity theories of humor. According to the Benign Violation Theory (BVT), something is perceived as humorous when it hits the “sweet spot,” where there is not only a violation, but where the violation is also perceived as benign. The BVT specifies how psychological distance plays a central role in determining whether a certain event, joke, or other stimulus is perceived as benign or malign. In line with the aims of this research topic, we specifically address how this “sweet spot” may be influenced by social distance. This form of psychological distance has so far received less attention in the BVT than other forms of distance. First, we argue that the BVT needs to distinguish between different perspectives in a given situation, i.e., between the joke-teller and the joke-listener, and needs to account for the social distance between the two parties as well as between each of them and the joke. Second, we argue that the BVT needs to acknowledge possible power asymmetries between the two parties, and how asymmetries might influence the social distance between the joke-teller and joke-listener, as well as between each of these and the joke. Based on the assumption that power influences social distance, we argue that power asymmetry may explain certain disagreements over whether something is funny. Third, we suggest that cultural differences might influence shared perspectives on what is benign vs. malign, as well as power balance. Thus, cultural differences might have both a direct and an indirect influence on what is perceived as humorous. Finally, we discuss potential implications beyond humor, to other social situations with border zones. Close to the border, there is often disagreement concerning attempted violations of expectations and norms, and concerning their nature as benign or malign. This can for instance occur in sexual harassment, #MeToo, bullying, aggression, abusive supervision, destructive leadership, counterproductive work behavior, organizational citizenship behavior, parenting, and family relations. New understanding of border zones may thus be gained from BVT along with our proposed systematically mismatched judgments which parties could make about attempted benign violations.

To the extent that amusement can be seen as an emotion, it is perhaps the emotion for which there is the strongest uncertainty as to what type of antecedents elicit it (McGraw et al., 2014; Martin and Ford, 2018). The fundamental question that any psychological theory of humor needs to explain is why something is perceived as funny and other things are perceived as not funny. A theory developed to answer both questions is the Benign Violation Theory (BVT) (McGraw and Warren, 2010; McGraw et al., 2012, 2014; Warren and McGraw, 2016). According to this theory, two types of appraisals must be simultaneously present for something to be regarded as funny. First, the stimulus must represent a violation which is contrary to expectations and threatens the person’s view of what the world “ought” to be. Examples could range from being “attacked” by a friend trying to tickle you, to violating a linguistic norm. Second, the violation must be perceived as benign, which may be influenced by several factors. In the current paper, we specifically focus on the social component of psychological distance (cf. Trope and Liberman, 2010). As will be accounted for in more detail later, increased psychological distance makes minor events appear less funny, and more serious events more funny (McGraw et al., 2012).

However, the BVT has certain limitations, which constitute the starting point for this paper. One is that even jokes that include norm violations not regarded as benign can sometimes be perceived as funny (Olin, 2016). Another is the failure of the theory to account for disagreements between people as to whether something is funny within a given situation (Meyer, 2000). In our view, theories of humor also need to address why people sometimes tell jokes that others may find insulting or inappropriate. Clearly, what is intended to be funny by someone telling a joke is not always perceived as such by others. Even seemingly intelligent and emotionally sensitive people sometimes make jokes that others find offensive. For instance, a sexual joke told by a leader to a follower in a workplace, may be perceived as harassment rather than a joke. The #MeToo campaign has shown that sexual harassment often occurs in cases where someone tried (or claimed to try) to be funny. Additionally, it often occurs in relationships of asymmetric power, and may be influenced by culture (Luthar and Luthar, 2002).

We suggest that the BVT could potentially be applicable to a broader array of situations if it included three additional elements: firstly, a distinction between the joke-teller and joke-listener; secondly, the role of power differences; thirdly, the acknowledgement of the cultural context in which a joke is told. All three elements are relevant to the model’s predictions about the role of psychological distance in humor. Note that we limit our discussion to cases in which humor is used with the intention of amusing others, rather than for other communicative purposes (cf. Meyer, 2000).

Psychological Distance in the Benign Violation Theory

According to the BVT, psychological distance reduces the tendency for people to perceive aversive stimuli or events as threatening (McGraw et al., 2014). When something is perceived as psychologically distant, people tend to represent them more abstractly (Trope and Liberman, 2010). The more psychologically distant a violation is, the more likely it therefore is to be perceived as benign. A violation can take the form of a threat to a person’s physical well-being, identity, or cultural, communicative, linguistic, and logical norms (Warren and McGraw, 2016; Warren et al., 2018). A threat is benign when perceived as “safe, harmless, acceptable, nonserious, or okay” (Warren et al., 2018, p. 5). Examples used by McGraw et al. (2012) include joking about someone stubbing their toe yesterday or being hit by a car 5 years ago. Importantly, the theory is not only concerned about what makes something funny, but also about what makes something not funny. A violation that is too harmless or too severe is not funny. Examples include, respectively, making a joke about someone stubbing their toe 5 years ago, or someone being hit by a car yesterday (McGraw et al., 2012).

The BVT builds on Trope and Liberman (2010, p. 440), construal level theory of psychological distance, in which psychological distance is defined as the “subjective experience that something is close or far away from the self, here, and now.” The theory distinguishes between four dimensions of psychological distance: firstly, temporal distance, i.e., whether something happened recently or a long time ago; secondly, geographical distance, i.e. whether something is physically near or far away; thirdly, hypotheticality, i.e. whether something is actually happening/perceived or only imagined; fourthly, social distance, which Liberman et al. (2007) exemplified as being determined by whether something happens to oneself or others, involves someone who is familiar or unfamiliar, or involves someone who belongs to an in-group or out-group. They also highlighted the relevance of social power.

The “Sweet Spot” of Humor is Also a Matter of Social Distance

A fundamental question in the BVT is to identify the area within which something is regarded as simultaneously benign and a violation. In a longitudinal study on temporal distance and humor, McGraw et al. (2014, p. 567), “posit the existence of a sweet spot for humor—a time period in which tragedy is not too close nor too far away to be humorous.” Throughout this paper, we use the term sweet spot synonymously with the distance range (temporal, geographical, social, or hypothetical) at which a violation is seen as benign for a given person or a dyad, and thus being potentially funny.

One limitation to empirical studies of the BVT is that they have not addressed all forms of psychological distance to an equal extent. Even though all four forms of distance are mentioned in the BVT literature, the main focus seems to be on temporal and geographical distance (e.g., McGraw et al., 2012, 2014). Accordingly, more is known about the sweet spot of humor in relation to these two distance dimensions than about hypothetical and social distance. Importantly, we know little about how the sweet spot for humor is influenced by social factors, including whether it happens to yourself or someone else, whether that “someone” is familiar or unfamiliar to you, or belongs to an in-group or out-group. Similarly, we know little about whether and how the sweet spot for humor may be influenced by social power.

The main emphasis here is on social distance, defined as the felt distance or closeness to another person or groups of people (Stephan et al., 2011). When we address the psychological distance between a person and a joke, social distance refers to the felt distance between the focal person and the individual, group, cultural practice, norms, or roles that the joke is concerned with. In the instances where our claims refer more broadly to psychological distance, we use this broader term.

A stronger focus on the role of social distance in humor also requires that theories explicitly distinguish between different social perspectives. This is because the sweet spot for humor may differ between people. The existence of different perspectives is not explicitly acknowledged in BVT, which instead largely focuses on situations where there is agreement over whether something is funny or not.

Notably, Kim and Plester (2019) also addressed the social element of humor, including the existence of multiple social roles and perspectives. They demonstrated how the perception and usage of humor in an organizational setting may be influenced both by the persons’ relative social positions and the culture at large.

The Importance of Social Context, Power, and Culture

Olin (2016) pointed to questions that theories of humor need to explain, over and above the fundamental question of what makes something funny or not funny. The majority of these questions related to the social/societal context in which humor takes place. The importance of knowing more about the social context of humor is also implicated in the current research topic. This goes both for the organizational context (Kim and Plester, 2019) and for the larger societal context (e.g., Jiang et al., 2019).

In the BVT, the sweet spot of humor has to do with identifying something which is a violation of the expected, while simultaneously being benign. However, to the extent that a humorous situation involves multiple persons, the sweet spot would also be likely to depend on social variables. One example is roles. You can play around with roles—violate them—in a benign fashion. For example, a violation can occur when a person by telling a joke steps out of their expected role. Such violations may be funny, for instance when a teacher starts dancing on the table. However, there are also potentially adverse sides of breaking roles or creating ambiguity around them (e.g., Örtqvist and Wincent, 2006; Eatough et al., 2011). One example would be a general practitioner who jokes with a patient about breaking doctor-patient confidentiality.

Violation of social expectations may also be funny. Social expectations may pertain to roles, but also to the activities, tasks, and goals that social relationships involve. Our social relationships to family, friends, leaders, and coworkers can involve a goal of catching a bus, getting a work task done, or getting the children to bed at night. It is therefore possible to violate the relationship itself, but also the activities or organizational interests (cf. House and Javidan, 2004; Einarsen et al., 2007).

In line with this general focus on the social element of humor, Olin (2016) differentiated between the joke-teller and joke-listener. This distinction is drawn in Olin’s discussion of jokes that implicate negative group stereotypes. Here, attitudes and beliefs of different parties may influence the extent to which a joke is perceived as humorous or harmful.

Interestingly, Kim and Plester (2019) drew similar distinctions in an ethnographic study of the influence of roles and hierarchy on humor perception and expression in Korean work settings. They found substantial differences in the contents of and reactions to humor among subordinates and superiors. For low-power individuals, humor expressions even had negative emotional consequences. This study demonstrates the importance of addressing multiple social perspectives and power differences in humor research.

Our theoretical account is also in line with a recent empirical study by Knegtmans et al. (2018), who studied the influence of power on the perception of jokes. However, here power was conceptualized as a temporary psychological state. In contrast, our conceptualization of power goes beyond temporary states, feelings or experiences of power. We focus on more stable power asymmetries deriving from hierarchical differences in organizations, and from social roles. Examples include a leader’s position compared to a subordinate’s, an emperor’s compared to a peasant’s, and a parent’s compared to a child’s. Furthermore, we emphasize the important role of culture, which is likely to have a direct influence on the shared norms for what constitutes a violation and what is considered benign (e.g., Gray and Ford, 2013). Culture could also influence norms for expressing amusement. It might also influence power differences and social distance in various ways. Thus, it could have both direct and indirect effects on humor perception.

To the extent that humor perception is influenced by power differences and culture, this may largely take place through their influence on social distance. Even though social distance, power, and culture are discussed separately in subsequent sections, it is important to keep their interrelatedness in mind.

Three Suggested Elements that Could be Added to Benign Violation Theory

We now turn to three components that in our view need to be included in the BVT to increase its explanatory value. These are in line with Olin’s (2016) suggestion to focus on the social aspects of humor in understanding when incongruent events are perceived as humorous and when they are not. They specifically address “boundary areas” of humor (e.g., Plester, 2016). These components are (1) distinguishing between the joke-teller and the joke-listener; (2) addressing possible power differences between the joke-teller and the joke-listener; and (3) acknowledging the influence of culture on the relationship between power differences and humor.

Note that this discussion will be limited to situations in which someone intentionally tells a joke to someone else, and where the intention is to be funny by hitting the sweet spot of both joke-teller and joke-listener. This is in contrast to any intentionally dark uses of humor (cf. Plester, 2016) aimed beyond the sweet spot, deliberately hurting the joke-listener, such as in power play, conflicts, ostracism, or bullying. A joke-teller may attempt both to split a crowd, hit the sweet spot with someone, while victimizing others (cf. Salmivalli, 2010). Again, our discussion concerns attempts to hit the sweet spot, and associated risks of over- or undershooting.

Joke-Teller vs. Joke-Listener

Empirical research on the BVT seems to mostly address situations in which someone regards or does not regard something as funny (McGraw and Warren, 2010; McGraw et al., 2012, 2014; Warren et al., 2018). However, one does not specifically differentiate between a joke-teller and a joke-listener, and whether different perspectives may influence the extent to which something is perceived as benign, a violation, and funny. If one is to understand humor at a level beyond the individual, this distinction is essential.

Thus, psychological distance in the BVT seems to normally be conceived of in terms of the distance from the person (who could either be the joke-teller or the joke-listener) to the something (the stimulus, which could either be a joke or an episode). The social setting in which the something is observed, heard, or experienced is not taken into consideration. In reality, a social setting would normally involve several people who would have different roles and perspectives and could in principle disagree as to whether the joke was a violation, whether it was benign, and whether it was funny. We choose here to use Olin’s (2016)terminology of joke-teller and joke-listener. Other related concepts are humor user, target person, and audience (Meyer, 2000).

Whether a joke told by a joke-teller to a joke-listener is perceived as funny by either or both of them could depend on a number of factors that would influence the extent to which something would simultaneously be seen as benign and a violation. It can be meaningful to analyze this in terms of the following four subtypes of social distance in a joke setting, namely sections “Social Distance Between Joke-Listener and Joke”; “Social Distance Between Joke-Teller and Joke”; “Social Distance Between Joke-Teller and Joke-Listener”; and “The Relative Social Distance Between Joke-Teller, Joke, and Joke-Listener.” We think that all four forms of relationships are relevant for both parties. However, because the joke-teller is the active part, s/he is perhaps more likely to actively consider these distances when preparing for a joke delivery than the joke-listener is when hearing a joke. In the following, we only provide selected examples illustrating either of these perspectives.

Social Distance Between Joke-Listener and Joke

The one form of distance that McGraw et al. (2012, 2014) have most clearly addressed is the psychological distance between the joke-listener and the joke. They addressed how a joke-listener can feel temporally close or distant to an event, depending on whether it happened recently or long ago. Similarly, a joke can pertain to something geographically close or far away. Here, we argue that a joke-listener and a joke also may be socially distant or socially close, as perceived by the joke-listener or joke-teller.

The social distance to a joke would be conceptualized slightly differently depending on whether or not the joke directly addresses specific people. To the extent that a joke refers to a person or group of people, the social distance to the joke would directly correspond to the social distance to those involved, whether it was a specific person or a group. Even jokes that do not refer to specific people may still have contents that are relevant to the social roles, social identities, attitudes, cultural practices, values, and norms of a joke-listener. The social distance to the joke would then depend on the person’s commitment or dedication to each of these. For instance, Hemmasi et al. (1994) showed that sexist jokes targeting the opposite sex were regarded as more funny (by men and women) than sexist jokes targeting one’s own gender. Similarly, violations could be more likely to be viewed as benign if concerned with an out-group or unfamiliar persons.

The social and ethnic groups and cultures to which the joke-listener belongs or associates her-/himself with would obviously be important. The history and identity of that larger group or culture in general could also be relevant.

Social Distance Between Joke-Teller and Joke

Another form of distance seemingly overlooked by the BVT is the perceived/attributed social distance between the joke-teller and joke, as perceived by either party. This refers to whether the joke-teller is perceived as either socially distant from or socially close to the content of the joke. The joke-teller’s perception of this may be likely to influence what s/he chooses to joke about. It is well established in research on attribution that emotional responses are highly influenced by inferences of responsibility, including intent, causal controllability, free will, and other associated concepts (e.g., Weiner, 1993, 2006). Therefore, the joke-listener’s perception of this form of distance could influence how s/he perceives the intention of the joke-teller. For instance, imagine someone (with intact vision) who tells a joke about blind persons. Whether this violation is seen as benign, and whether the joke is perceived as funny, might depend on whether the joke-perceiver knows or thinks that the joke-teller has had a close personal relationship with someone who is blind.

Thus, the perceived social distance between the joke-teller and the joke might be influenced by the one person’s perception of the other’s attitudes, social roles, social identities, cultural affiliation, etc. (Liberman et al., 2007; Trope and Liberman, 2010). The perception of the joke-teller’s actual roles and identities may be more or less accurate.

Social Distance Between Joke-Teller and Joke-Listener

The social distance between the joke-teller and joke-listener is also relevant. This point is related to but not overlapping with the two previous points.

The closeness of the relationship between the two parties is important. If the joke-teller and joke-listener do not have a close personal relationship, it is relevant whether the joker is familiar or unfamiliar, or belongs to an in-group or an out-group. Note that the two parties may have a different idea of what the social distance is between them.