#ancient Thessaly

Text

Olympus: The Fall of the Giants (Battle of the Titans)

by Francisco Bayeu y Subías

#olympus#gods#war#battle#giants#titans#art#mount olympus#olympians#greek mythology#mythology#mythological#history#europe#european#jupiter#titanomachy#ancient greece#ancient greek#ancient thessaly#thessaly#greece#gigantes#cronus#zeus#cyclopes#ancient#antiquity#neoclassical#mediterranean

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

„We shall proceed down the south slopes of the acropolis of Larisa to more familiar ground. Dionysus was worshipped here in one of his well-known settings, close to a monumental theatre constructed in the third century bc. He was invoked as Dionysus Makedonikos in a first-century dedication offered to him by the priestesses of Aphrodite. But he was also worshipped in a more Thessalian guise. A list of the priestesses of Demeter Phylaka and archousai of Dionysus Karpios was inscribed on a first-century stele found in the wider area of the acropolis. The title Karpios for Dionysus seems to have had an old Thessalian pedigree. It can be traced back to the fifth century, when the god received a dedication at Larisa. He was also worshipped at Mikro Keserli, a small settlement to the east of Larisa, and at Gomphoi in western Thessaly.

The pairing of Dionysus and Demeter is not uncommon, given the agricultural connections of both deities, a point reinforced by the title Karpios (deriving from karpos ‘fruit’) given to Dionysus. The cult of both deities, it is often stated, was very popular in Thessaly, an area famous for its agricultural produce. There is quite a lot of evidence for their cult, but we should not consider the matter entirely straightforward and unproblematic. Their cults introduce us to a number of questions concerning the relationship between agriculture and religion in Thessaly.

To help understand the issues at stake we can bring here, as a parallel, the case of Sparta. In both areas much agricultural work was done by the servile classes of the penestai and helots, while anyone with social or political aspirations should have had his hands free from agricultural labour. Related to this characteristic of Spartan society, it has been argued, was the fact that the cults of Dionysus and Demeter did not develop in the way they did elsewhere in the Greek world; only certain aspects of their cult seem to have been prominent. Thessaly, however, was no Sparta. Despite Pindar’s invocation, in the first lines of Pythian 10th, of their common Heraclid origin, the two states were in several respects very different. To boil the matter down to its essentials we could say that Sparta had a military aristocracy, while Thessaly had a landed one. The fertility of the Thessalian land was a common topos in literary sources, and the Thessalian noblemen, although never engaged themselves in agricultural labour, were still very often mentioned in the same breath as their vast estates of lands, their numerous penestai, and large flocks of animals. Neither was the status of the Thessalian under-classes comparable in all matters to that of the helots. The helots were owned by the Spartan state, while no such evidence exists for the penestai, who seem to have been closely associated with their owners; and while every year Sparta declared war against its helots, the Thessalian penestai seem to have found themselves regularly fighting at the side of their masters. In a land that boasted its fertility, it is thus no surprise to find the cult of such agricultural gods as Dionysus and Demeter housed on the acropolis of its cities.”

- Religion and Society in Ancient Thessaly by Maria Mili

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

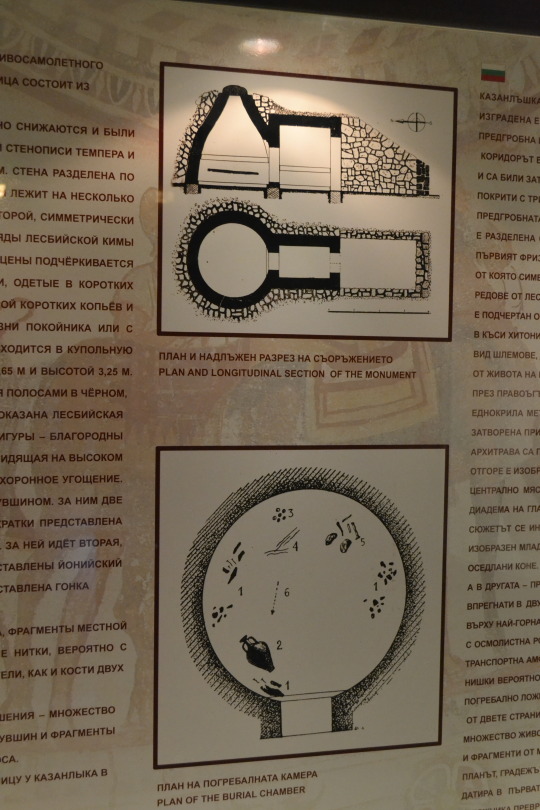

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some really good news overshadowed by the tragedy with the floods in Larissa and the rest of Thessaly but

the ancient theatre downtown in Larissa was recently open again to an audience after 1700 years! The ancient theatre was built in the 3rd century BC and operated for 600 years until it was severely damaged from an earthquake in the 3rd century AD and stopped being used. In the 7th century, another earthquake destroyed it completely.

The theatre had a capacity of 10,000 people and it was dedicated to Dionysus.

It has been a well known historical attraction in Larissa, however now after some progress in the long restorations, it is becoming again a functioning theatre like all ancient theatres in Greece that are in a decent enough condition.

#greece#europe#theatre#ancient theatre#ancient greece#greek history#history#larisa#larissa#thessaly#mainland

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coin of the Thessalian city of Larissa, minted in 440 BCE. On the obverse, a man wrestling a bull, perhaps representing Heracles' Seventh Labor (the struggle with the Cretan Bull). On the reverse, a bridled horse galloping. Thessaly was famed in antiquity for the excellence of its cavalry and the fine quality of its horses. Photo credit: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Classical Greece#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Classical Greek art#Thessaly#Thessalian art#coins#ancient coins#Greek coins#Ancient Greek coins#numismatics#ancient numismatics

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

So the book I'm reading keeps mentioning the witches of Thessaly, so I looked up a few and I came across this article Witches of Thessaly by Brian Clark. Who is Brian Clark? What authority does he have? I can only find reference to this one article and nothing else is pulling up. I'm very skeptical. I haven't read the article yet, but it's just sitting in a tab on my computer.

#anyone know anything#idk im just sitting here#helpol#witchblr#theres so many references to witches of Thessaly in ancient greece and rome#and im kind of surprised i havent heard of it before because I spent a good summer immersing myself in ancient greek texts

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Neil. I am happy to report there is at least one other ancient photo of us from around 1991.

I've been asked if I ever wore glasses like Thessaly's, and I've said no. But there it is. Right in front of me. Thessaly's glasses.

Man, the things we forget. Like, glasses.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Greek Temple Complex Reveals Thousands of Votive Figurines

Archaeologists excavating a hilltop sanctuary on the Aegean Sea island of Kythnos have discovered “countless” pottery offerings left by ancient worshippers over the centuries, Greece’s Culture Ministry said Wednesday.

A ministry statement said the finds from work this year included more than 2,000 intact or almost complete clay figurines, mostly of women and children but also some of male actors, as well as of tortoises, lions, pigs and birds.

Several ceremonial pottery vessels that were unearthed are linked with the worship of Demeter, the ancient Greek goddess of agriculture, and her daughter Persephone, to whom the excavated sanctuary complex was dedicated.

The seaside site of Vryokastro on Kythnos was the ancient capital of the island, inhabited without break between the 12th century B.C. and the 7th A.D., when it was abandoned for a stronger position during a period of pirate raids.

The artifacts came from the scant ruins of the two small temples, a long building close by that may have served as a temple storeroom and a nearby pit where older offerings were buried to make space for new ones. The sanctuary was in use for about a thousand years, starting from the 7th century B.C.

The excavation by Greece’s University of Thessaly and the Culture Ministry also found luxury pottery imported from other parts of Greece, ornate lamps and fragments of ritual vases used in the worship of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, an ancient Athens suburb.

It is unclear to what extent the site on Kythnos was associated with Eleusis — one of the most important religious centers in ancient Greece, where the goddesses were worshipped during secret rites that were only open to initiates forbidden to speak of what they saw. The sanctuary at Eleusis is known to have owned land on the island.

Kythnos, in the Cyclades island group, was first inhabited about 10,000 years ago. Its copper deposits were mined from the 3rd millennium B.C., and in Roman times it was a place of political exile.

The excavations are set to continue through 2025.

#Greek Temple Complex Reveals Thousands of Votive Figurines#island of kythnos#pottery#pottery offerings#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#greek art#long reads

530 notes

·

View notes

Text

During the second or first century BCE, a woman pretended to be able to control the moon. This was Aglaonice, who is regarded by some as the first known female astronomer.

She’s mentioned in the writings of Plutarch and the scholia to Apollonius of Rhodes and lived in Thessaly, Greece. Being “skilled in astronomy”, Aglaonice used her knowledge to predict eclipses and make people believe she caused the moon to disappear.

According to Plutarch:

“Thoroughly acquainted with the periods of the full moon and when it is subject to eclipse, and, knowing beforehand the time when the moon was due to be overtaken by the earth’s shadow, imposed upon the women, and made all believe she was drawing the moon down.”

The scholia adds that Aglaonice lost a close relation as a punishment for having angered the moon goddess.

Interestingly, Thessaly is associated with women skilled in astronomy and occult practices. Several female astrologers from the third to first centuries BCE were for instance known as “The Witches of Thessaly”. These women were said to study the movements of the moon and trick people into believing that they caused lunar eclipses.

In Plato's Gorgias, Socrates mentions the "Thessalian enchantresses who, as they say, bring down the moon from heaven at the risk of their own destruction."

Today, a crater on Venus bears Aglaonice’s name.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading:

Bicknell Peter, "The witch Aglaonice and dark lunar eclipses in the second and first centuries BC."

Chrystal Paul, Women in Ancient Greece

Plutarch, On the failure of oracles

Plutarch, Conjugalia Praecepta

Reser Anna, McNeil Leila, Forces of Nature: the women who changed science

#aglaonice#history#women in history#women's history#women in science#herstory#greece#ancient greece#antiquity#scientists#astronomy#historyedits#1st century BCE#ancient world#historical figures

104 notes

·

View notes

Note

I can't help but think that, after a certain point, the only thing keeping Hob from devouring Morpheus like he hasn't eaten since 1689 every time Thessaly opens her mouth is that Morpheus...Might not appreciate that(What with his track record for romantic obsession/near-ironclad monogamy). Your thoughts?

SO there is that (Morpheus being obsessively focused on one romantic partner at a time) keeping Hob from saying much, but also I don't see it being quite as territorial as going at Morpheus like a chew toy. Not that Hob wouldn't ever territorially get his teeth everywhere if given half a chance, but it'd probably be mostly once they're established as a couple (and partially fueled just by the fact that he knows Morpheus is INSANE for someone wanting to devour him like a starved animal, and Morpheus deserves to have that damnit so Hob Gadling is going to deliver!)

The reason Hob has to be held back from throwing hands with one of the most ancient witches is more than the sort of possessiveness implied by wanting to eat someone alive. I imagine it's like

-Hob at this point has known that Morpheus has been in relationships and that they've affected him deeply. Maybe he even met Calliope and it led to a bit of "JFC Gadling that is a beautiful actual goddess of poetry with a sweet smile and soothing voice so you best just settle your history professor ass down mate, can't compare to that holy fuck." But he has not seen Morpheus IN a relationship.

-Now he is seeing it. Hob is seeing all the "I will give you worlds like strung jewels. I can create the most breathtaking dreams solely from the way the light hits your eyes. We got together two weeks ago here are floor plans for the rooms I'm creating just for you within my palace when do you think you can move in??????" He sees Morpheus revealed as the obsessively romantic, clingy lunatic he is; grasping and looking like a half starved puppy for the slightest sign of returned affection. It's everything Hob could have wished for! (Plus yeah it's super obvious that Morpheus is too head over ass to hear anything, let alone respond positively to someone else trying to move at him.)

-Hob's also seeing Thessaly, current object of all this obsessive grabbing and sappy lovestruck eyes and wistful sighing. And she isn't even appreciating it!!! Sure she likely enjoys the attention (judging by the fact that she bounces once Morpheus stops paying sole attention to her). But she's just like "sure" back at Morpheus launching heart eyes like grenades. And we've all seen a friend who is over the moon for someone who is so obviously not nearly as invested.

A lot of the frustration is just the universal experience of a friend who is obviously going to get his heart broken and you're gonna need to be breaking your jaw biting down on the "oh noooooo 🙄 " trying to comfort them after. Because there is no way "mate we fuckin told you" is gonna fly well with Morpheus.

- also every time Thessaly opens her mouth Hob isnt as focused on furiously chewing on Morpheus because it's more

And him blasting "Girlfriend" by Avril Lavigne every time Morpheus sighs over this woman who said he wasn't even that good looking what the fUCk then move out of the way for someone who will treAT HIM RIGHT

#the devouring him like a starving peasant comes later#Dreamling#thessaly like '.....'aight'#this isnt a thessaly hate blog I just think Hob runs a thessaly hate blog

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hair offerings: historical context, purpose and uses

Offerings of hair, locks of hair or ritual hair-cutting is quite a regular occurrence in ancient sources and textbooks discussing various religious customs of the ancient Greek world. It also seems to be a fairly forgotten offering in a modern context, which is why I wanted to delve back in and write this post. I will be focusing on laying out the historical contexts in which we find this specific offering in order to understand the core logic behind what it means to offer a lock of hair to a deity.

Rites of passage

It is impossible to mention offerings of hair without touching on the topic of “rites of passage”. However, this is an umbrella term that encompasses different kinds of rites or life events depending on the environment and stage of life of the participants.

Kourotrophic hair-cutting

Arguably the most common example of offerings of hair is the one done by boys, typically when entering adulthood (typically referred to as paides or ephêboi), but there are important variations depending on the era and local customs, with the youngest example known being the one of a 4-year-old boy in the 3rd century BC.

Kourotrophic deities typically refer to Apollo, Artemis and the plentitude of local river gods. However, this is far from being the only gods considered kourotrophoric since we also have evidence that includes Poseidon, the Nymphs, Asklepios and Hygieia in that group.

There were several occasions for which young boys would offer their hair. In Athens, later sources mention that the 3rd day of the Apatouria festival included the ritual cutting and offering to Artemis of the hair of the young men who officially entered their phratries after having made an offering of wine to Herakles.

In a wider context, kourotrophoric deities are concerned with the growth and well-being of children and adolescents. It seems common that offerings were made pursuant to a vow, often done by a parent while the adolescent is still a child (or even just born). Their purpose is to help assure successful maturation, but they seem to work by establishing a positive relationship with the kourotrophic deity. These rites unfold over a long period of time: there is a vow, a period of hair growth that might last for many years, and then, a ceremonial cutting.

Pausanias gives us an example of ritual growing of the hair for the river god Alpheios in his story about Leukippos, stating he “wove the hair he was growing for the river Alpheios in the same way that maidens do.” (Pausanias 8.20.3)

The organization of the final cutting seems to have been a familial event that included the participation of the parents, if they didn’t even make the offering themselves on behalf of the son. Three inscriptions from the island of Paros in the 3rd century AD describe the offering of “childhood” or “ephebic” hair done by a parent to Asklepios and Hygeia, instead of being performed by the boy himself.

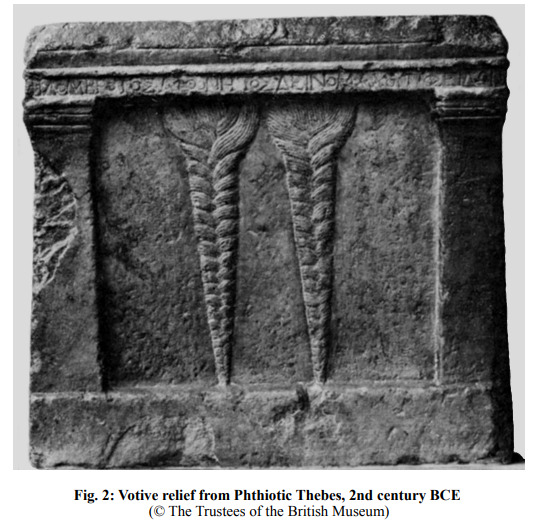

A noteworthy example from Thebes shows the participation of a brother instead of the parents (see image below). In this case, the dedication of the hair, shown braided, is made to Poseidon by Philombrotos and Aphthonetos, sons of Deinomachos. David Leitao rules out the possibility of this inscription being about a votive, in favour of it being a rite of passage for two reasons: firstly, the locks that are sculpted in relief on the stele are long and carefully braided, and reminiscent of the braids frequently seen elsewhere on the heads of boys and adolescents in Greek sculpture. Secondly, Poseidon seems to play an important role in the growth of children in Thessaly in particular.

Further reading for this section:

→ Leitao, David D. "Adolescent hair-growing and hair-cutting rituals in ancient Greece: A sociological approach." Initiation in ancient Greek rituals and narratives. Routledge, 2013. 120-140.

→ Pilz, Oliver. "Water, Moisture, Kourotrophic Deities, and Ritual Hair-Cutting among the Greeks." Les études classiques 87.1-3 (2019).

Marriage

If young men grew and offered their hair to kourotrophoric deities at a young age, girls and young women tended to offer a lock of hair a bit later, as part of the pre-nuptial rites. While the practice was widespread throughout the Greek world, we can use this passage from Herodotus (4.34) concerning the citizens of Delos to illustrate the phenomenon:

“And in honor of these Hyperborean girls who died in Delos, the girls and boys of Delos cut their hair. The girls cut off a lock before marriage, wind it around a spindle, and place it on the tomb (the tomb is within the sanctuary of Artemis, on the left side as one enters, and an olive tree grows there); and the Delian boys wind some of their hair around a kind of grass and they, too, place it on the tomb.”

Similar pre-nuptial rites are attested elsewhere: in Troezen, the brides dedicated a lock of hair to the temple of Hippolytus (Pausanias 2.32.1) while in Megara, the brides made the offering on the tomb of the maiden Iphinoe.

Offerings of hair before marriage is only one of the many pre-nuptial offerings. Katia Margariti calls it a “very symbolic premarital offering” and notes that in most of the cases mentioned, the brides offered their hair to maidens who had died before they could transition into adulthood. Hippolytus, son of Theseus, stands as an exception, the aetiological myth behind the rite being that he angered Aphrodite by staying chaste in honour of Artemis, which caused his tragic death (before being resuscitated by Asklepios). It is in this context that he places himself as an appropriate recipient for the offering of brides.

In Athens, the offering of hair from brides was addressed to Artemis directly instead, but it could also be made to Hera and/or to the Nymphs.

Let me quote Evy Johanne Håland to summarize what has been said so far:

“The cutting of hair, ‘the crown of childhood’, admits boys and girls to society, announcing their passage to adulthood and marriage. By offering the aparchai, first fruits or primal offerings, to the life-giving waters, boys who were initiated as warriors and girls ensured their fertility in their married lives. Haircutting symbolizes the transition to another stage in life. This practice is found in ancient and later periods of Greece, where the fountains were decorated with maidenhair until modern times. In this connection the theme of death and rebirth is important, since the initiates are reborn into a new life. Moments of transition from one state of life to another are high points of danger, and the person is especially vulnerable to spirits, agencies, influences, or invisible mischief.”

Further reading for this section:

→ Oakley, John Howard, and Rebecca H. Sinos. The wedding in ancient Athens. University of Wisconsin Press, 1993.

→ Margariti, Katia. "The Greek Wedding outside Athens and Sparta: The Evidence from Ancient Texts." Les Études Classiques 85.4 (2018).

→ Dillon, Matthew PJ. "Post-nuptial sacrifices on Kos (Segre," ED" 178) and ancient Greek marriage rites." Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (1999): 63-80.

→ Håland, Evy Johanne. "“Take, Skamandros, My Virginity”: Ideas Of Water In Connection With Rites Of Passage In Greece, Modern And Ancient." The Nature and Function of Water, Baths, Bathing and Hygiene from Antiquity through the Renaissance. Brill, 2009. 109-148.

Death, the dead and departures

With everything that has already been brought up, it comes as no surprise to find offerings of hair in funerary context. Death is, after all, a great transition, both for the deceased and the one suffering the loss of a loved one.

The premarital offerings of hair already hinted towards a link to death, whether it is through the remembrance of a dead hero or, more symbolically, the death of childhood.

While not a dedication to a deity, the symbolism of hair in the context of remembrance is something also found in a gesture connected with the memory of fallen soldiers: the warrior cuts strands of his hair, which after his death were then handed over to his relatives.

It is tempting to link this gesture to the funerary rituals that involved hair. As such, already in the Archaic era, it was customary for each attendee of a funeral to place a lock of their own hair upon the remains of the deceased. The Iliad gives us an idea of such a rite in Book 23 and to the rite of growing hair for a river god.

“No, before Zeus, who is the greatest of gods and the highest, there is no right in letting water come near my head, until I have laid Patroklos on the burning pyre, and heaped the mound over him, and cut my hair for him, since there will come no second sorrow like this to my heart again while I am still one of the living.”

“In the midst of them his comrades bore Patroklos and covered him with the locks of their hair which they cut off and threw upon his body. Last came Achilles with his head bowed for sorrow, so noble a comrade was he taking to the house of Hades.”

“He went a space away from the pyre, and cut off the yellow lock which he had let grow for the river Spercheios. He looked all sorrowfully out upon the dark sea, and said, "Spercheios, in vain did my father Peleus vow to you that when I returned home to my loved native land I should cut off this lock and offer you a holy hecatomb; fifty she-goats was I to sacrifice to you there at your springs, where is your grove and your altar fragrant with burnt-offerings. Thus did my father vow, but you have not fulfilled the thinking of his prayer; now, therefore, that I shall see my home no more, I give this lock as a keepsake to the hero Patroklos. […]As he spoke he placed the lock in the hands of his dear comrade, and all who stood by were filled with yearning and lamentation.”

The implications of this passage would deserve its own post, and I won’t dwell on this, but we can clearly see the double layer of symbolism at play with the locks of hair alone.

When it comes to burial rites, beyond the Archaic customs, Ochs interprets the custom this way: “Rhetorically, cutting a lock of hair and placing it in the grave can be understood as a message of collective solidarity. All mourners in the polis engaged in the same action and, thus, by doing so reaffirmed the cohesion of their beliefs. Note also that the collective, dedicatory message is directed at the deceased. The symbolic behavior, therefore, visually links the living community with the dead person or, more accurately, the dead person's spirit. In other words, the message is one of aggregating the living with each other and the living with the soul of the deceased.”

We can also find another purpose in the scope of ancient tragedies about Orestes and Elektra, where post-burial offerings are used to pacify the dead and to convey personal affection primarily through the use of food and drink. The lock of hair is also found but it functions in the plays as a device for recognition.

Further reading for this section:

→ Closterman, Wendy E., A. Avramidou, and D. Demetriou. "Women as gift givers and gift producers in ancient Athenian funerary ritual." Approaching the Ancient Artifact: Representation, Narrative, and Function. A Festschrift in Honor of H. Alan Shapiro (2014): 161-174.

→ Barbanera, Marcello. "Dressing to Hunt: Some Remarks on the Calyx Krater from the So-Called House of C. Julius Polybius in Pompeii." Approaching the Ancient Artifact: Representation, Narrative and Function. A Festschrift in Honor of H. Alan Shapiro (2014): 91-104.

→ Ochs, Donovan J. Consolatory rhetoric: Grief, symbol, and ritual in the Greco-Roman era. Univ of South Carolina Press, 1993.

Votives

Last but not least, now that the heavier ritual uses have been covered, is the topic of hair offerings as a way to say “thank you”. Similarly to how the offering of hair from young boys to river gods came as a petition for safety, we find locks of hair being used as thanks to surviving dangerous situations like illnesses or an escape from a disaster.

A Hellenistic epigram names the rescue from distress at sea as reason for a ritual hair-cutting, where a man named Lukillios shaves off his hair for Glaukos, the Nereids, Melikertes, Poseidon and the Samothracian gods as thanks for surviving the incident.

Another example is one told to us by Pausanias concerning the cult of Asklepios and Hygieia in the city of Titane:

“Of the image [of Asclepius] can be seen only the face, hands, and feet, for it has about it a tunic of white wool and a cloak. There is a similar image of Hygieia; this, too, one cannot see easily because it is so surrounded with the locks of women, who cut them off and offer them to the goddess, and with strips of Babylonian raiment. With whichever of these a votary here is willing to propitiate heaven, the same instructions have been given to him, to worship this image which they are pleased to call Health.” (Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.11.6–7)

While it is impossible to know the exact reasons why each of the women offered their hair to Hygieia, the idea that it was in return for health sounds the most logical.

In the sanctuary of Zeus at Panamara in Caria hair was either enclosed in a small stone coffer in the form of a stele and set up in the precinct with an inscription placed upon it, or placed in a hole in the wall or hung upon the wall with a small label placed upon it. The former was probably for the wealthiest citizens, while the latter reserved for those with less means. In the case of the former, the hair itself was no longer visible, but the stele and inscription were. In the case of the latter the hair remained visible in conjunction with a label that named the dedicant. The care put into storing the locks in these examples is telling of an offering that is symbolically charged and likely lasted a lifetime, due to the durability of hair.

Similarly, an epigram in the Palatine Anthology, attributed to Antipater of Thessalonica poetically tells of the hair offering of a young man to Apollo:

“Having shaved the down that flowered in its season under his temples, [he dedicated] his cheeks’ messengers of manhood, a first offering, and prayed that he might so shave gray hairs from his whitened temples. Grant him these, and even as you made him earlier, so make him hereafter, with the snows of old age upon him.”

While this epigram is clearly related to the idea of hair-cutting for young boys, as it refers to the growth of the first facial hair, it also begs the question of the quality of the appearance of the first white hair. Aside from being a poetic call to the blessing of living a long life — long enough to know old age — we might want to wonder about what it would mean to offer one’s white hair within the logic of transition from adulthood to seniority.

Further reading for this section:

→ Draycott, Jane. "Hair today, gone tomorrow: The use of real, false and artificial hair as votive offerings." Bodies of Evidence. Routledge, 2017. 77-94.

Final thoughts

If there is something to take away from the historical uses of hair in the religious setting of the Ancient Greeks, it is the idea of transition. From the entrance into adulthood to death, hair offerings come up at key moments in one's life, or at least, in answer to brushes with death, placing hair in a very important position. It is a highly personal, intimate and symbolic offering.

While this post isn't the place to discuss modern reinterpretations, I think the key to integrating hair offerings in reconstructionist practice comes down to asking yourself the question of what the milestones in our modern lives are and what they mean, alongside other life-changing events.

#hellenic pagan#hellenic worship#hellenic revivalism#hellenic reconstructionism#hellenismos#hellenic paganism#hellenic polytheism#hellenic gods#offerings

514 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deucalion’s Flood by Giulio Carpioni

#deucalion#flood#deluge#art#giulio carpioni#pyrrha#prometheus#zeus#greek mythology#ancient greece#ancient greek#angel#angels#gods#mankind#mythology#religion#ark#boat#chest#floods#classical antiquity#animals#humanity#mount parnassus#thessaly#mediterranean#europe#european#rebirth

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

„The evidence concerning Hera’s status in Thessaly is ambiguous, and has given rise to diametrically different interpretations: for some Hera’s cult was introduced to Thessaly only at a late date and was of little, if any, importance, while for others she was one of the oldest and most important divinities of the area. The kinds of evidence that form the main source material for Thessalian religion, that is coins, inscribed dedications, and archaeological remains, are mostly late in date and give us very little and uncertain information about her cult in Thessaly and in the various perioikic areas. It is hardly worrying that Hera may not have been depicted on Thessalian coins. As one moves to examine the evidence of inscribed dedications the absence of any offerings to Hera from almost all Thessalian cities, and indeed from the rich corpora of Atrax and Gonnoi, becomes more alarming. Atrax, Gonnoi, and yet other Thessalian cities have furnished a wealth of dedications made by women on different important occasions of their lives, sometimes no doubt in connection with marriage, as is probably the case with some dedicatory inscriptions to Artemis and Demeter. One might have expected Hera to be markedly present in the evidence. … To be fair, she is not totally absent. There are a couple of Hellenistic inscribed dedications to her from Larisa and Demetrias. The idea that the dedications from Larisa and Demetrias should not be dismissed as simply late and circumstantial evidence gains support from the fact that in both places there is further epigraphic evidence for Hera’s cult. …

Be that as it may, in one context Hera’s absence is definite and demands further explanation. A fourth-century monument found at Pherai, persuasively reconstructed as an altar, has inscribed on one of its long sides the names of six goddesses. It seems to have been only one-half of a larger monument consisting of two separate altars dedicated to the twelve gods (the second altar would have borne the inscribed names of six male gods). Several of the well-known Olympians are included among the six goddesses: Athena, Demeter, Aphrodite, and Hestia. Hera and Artemis, however, are omitted and in their place we find the lesser divinity Themis and the local Thessalian deity Ennodia. … According to scholarly consensus, the cult of Themis, who was one of the earlier wives of Zeus in mythology, was very important and had deep roots in Thessaly. Themis, however, cannot have replaced Hera in Thessaly, at least not so straightforwardly and simply as a scholar such as Miller seems to imagine. Thessalian Themis does not seem to have been involved in marriage, Hera’s traditional domain. Her role was mostly political. And it seems that it was precisely thanks to her important political role that she was included among the twelve gods on the Pheraian monument.

The evidence of myths adds further depth to our analysis of the status and role of Thessalian Hera. Hera looms large in the story of Pelias, the mythical king of Iolkos. Pelias, the story went, was very disrespectful of the goddess, while he honoured mostly Poseidon, who was his father. As is usual with similar stories, divine punishment ensued. Hera’s wrath fell upon Pelias, and it was with her help that Jason won the golden fleece and returned with Medea to Iolkos, who caused the death of Pelias. The story, it could be argued, concerns the division of timai between the two powerful deities, as the growing powers of one encroached on those of the other. It is in this context of division of timai between Hera and Poseidon that we should place a group of inscriptions found in the wider area of Larisa and which give Poseidon two cultic epithets, Impsios and Zeuksanthios, which resonate closely with epithets attributed to Hera in her stronghold, the Argolid. Impsios is the Thessalian equivalent of Zygios (the one who yokes), and Zygia was a well-known epithet of Hera; while Zeuksanthios seems to be a combination of Antheia, another well-attested epithet of Hera, and Zeuksidia, a variation of the epithet Zygia. …

A closer reading of the fragmentary second-century inscription from Larisa, referred to already, reveals a landscape saturated with Hera’s myths. Amongst the various sanctuaries and sacred properties listed, which include a sanctuary of Zeus and Hera, there is also a reference to the little-known hero Epaphos. Epaphos was, according to mythology, the son of Io, the tortured priestess of Hera at Argos, who crossed the world haunted by the gadfly that Hera had sent to punish her, in search of a place to rest and give birth to her son. That this Argive set of myths is found here, transplanted to the northern plains in the shadows of Mount Olympus, is not surprising: after all this was once Pelasgian Argos. We have come full circle, from Hera’s exclusion from the twelve of Pherai, and her faded trace in the material evidence, to her unmistakable stamp on the mythical landscape of Thessaly. Some focus on the first to underline her supposed absence; others on the last: Hera is there, as powerful as ever, it is the evidence that falls short! But in truth, each of the different kinds of evidence allows us only a partial and distorted view of the role of the goddess in the area. Only by piecing it all together can we trace the contours of Hera’s place within her Thessalian family.”

- Religion and Society in Ancient Thessaly by Maria Mili

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

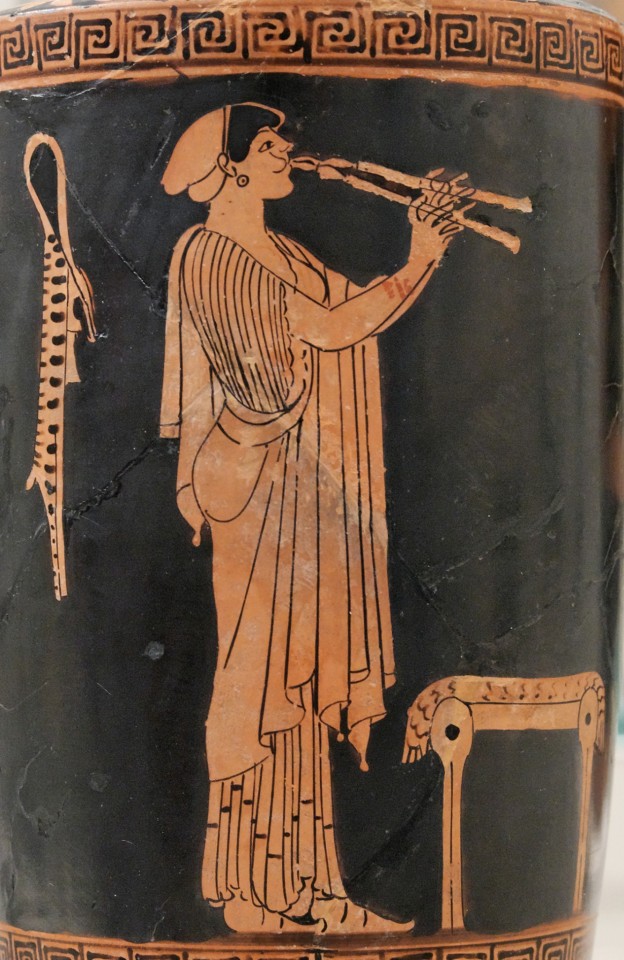

Ancient Greek pottery showing figures playing the auloi. The aulos (plural auloi) [Roman tibia, plural tibiae] is a double or single reed wind instrument, played in pairs, that "sounded more like the modern oboe than the modern flute." [source]

"Perhaps the most commonly played instrument in Greek music, the aulos was played in festivals, processions of births and deaths, athletic games ... It was associated with the god Dionysos and often played at private drinking parties." [source]

"Made from cane, boxwood, bone, ivory, or occasionally metals such as bronze and copper, the circular pipe (bombyke) was fitted with one, two or three bulbous mouthpieces which gave the instrument a different pitch." [source]

"The earliest surviving examples of auloi have been found at Koilada, Thessaly and date from the Neolithic period (c. 5000 BCE). These instruments are carved from bone and have five holes, irregularly placed down their length." [source]

#aulos#auloi#tibia#tibiae#ancient greece#pottery#ceramics#musical instruments#wind instruments#antiquities

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atalanta #4 (Atalanta Outwrestles Peleus)

At the funeral games for King Pelius, Atalanta wrestles the Argonaut, Peleus, winning the match through strength and technique.

Looking to Homer and the Iliad and the funeral games for Patroclus, we can get a overview of the ancient greek funeral games. The body of the fallen was placed upon a funeral pyre, offerings or sacrifices are made, and the pyre burnes. In the funeral games was an opportunity for Greek men to compete and show their Arete, or excellence, in a given skill. Events like; Chariot races, boxing, wrestling, running, sword fighting, shotputting, archery, and javelin throwing. The winners of the contests could hope to be awarded the glorious olive wreath crown; or other precious objects like tripods or horses. In fact these funerary competitive games are seen as the ancient roots of the Olympic games. Although it was Hercules who created the first Olympic games to honor his father, Zeus.

Let’s take a look at Atalanta’s wrestling partner; Peleus, who plays an important role in Greek myth. As one of the heroes of the Argonautica, he later becomes a king of Phthia (in Thessaly) and is most famous for his marriage to the sea nymph Thetis. Zeus learned the prophecy that through his coupling with Thetis, her offspring would overthrow the Olympians, so he gave Thetis to a mortal; King Peleus. Chiron the centaur gave King Peleus the tip that he should ambush and hold tight to Thetis, as she transformed between forms. After succeeding to capture her, she agrees to marry, and the gods attend the wedding ceremony. This is the banquet where Eris, goddess of discord, sneaks in the golden apple inscribed with “for the farest,” setting off an argument between Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite. When Paris, prince of troy is Aphrodite promising Helen to Paris, setting off the Trojan war.

Like this art? It will be in my illustrated book with over 130 other full page illustrations coming in June to kickstarter. to get unseen free hi-hes art subscribe to my email newsletter

Follow my backerkit kickstarter notification page.

Thank you for supporting independent artists! 🤘❤️🏛😁

#greekmythology#greekgods#pjo#mythology#classics#classicscommunity#myths#ancientgreece#argonauts#ovid#homer

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

⭐ give us the bonus features/making of for your big bang fic!

Ooooh! OK!

For "Hell or High Water" it all started with a poll I made in May 2023 to decide which kind of fish half to give merman Hob. The British or Common Skate won and my merman Hob was born. The rest is kinda history lol.

For months I drew sketches and came up with a few scenes, like Morpheus being a freediver and dropping the ruby for Hob to find. I watched a documentary on freediving ("The Deepest Breath"), and skates of course. I talked a lot to mutuals like @amielot who helped me come up with some ideas for the story and whose drawings of Hob and Johanna shaped the way I wrote their relationship a lot.

Thinking about mermaids and movies with mermaids made me remember "Dagon", which has an ending scene that has very much made a lasting impression on me (and made me realise that I am quite a bit thalassophobic), and so I thought - "let's make it a bit creepy, a bit Lovecraftian."

I listened to "The Shadow over Innsmouth" and a lot of other Lovecraft over the next months, put together a playlist for writing and got to work on gathering more information to build my world. I decided to go with Lovecraft's love for ancient cultures as the cradle of weird/inhuman cults and made Hob's ancestors be descendents of Tiamat, originally living in the Mediterranean and Red Sea, using Accadian and Cuneiform writing as their form of communication. I have a whole Gdoc dedicated to notes for the fic, and another one for the story outline.

I really put in a lot of effort but it was worth it. I love research and world building, I loved learning about freediving and revisiting my knowledge about Accadian language (I did two semesters of "Oriental studies" at the beginning of my time as a university student).

At that point I don't think that I had decided to write the fic for the Big Bang, but then I thought, "why not? The pressure will help me actually write it." And it worked!

While writing I think I changed a few ideas of the story. For example, I had debated to let Thessaly try and romance Morpheus and make Hob even more jealous, but I decided to cut that short and let her focus on the ruby.

I also needed a lot of time to figure out what to do about Johanna's selkie skin, there were different ideas, like have Morpheus stumble upon it where Jo had simply forgotten it. I think the final solution came to me fairly late into writing, but I'm very glad I thought of Rachel.

It was my first time taking part in a Big Bang and I hope to take part in the next. There's nothing better for me than a project deadline actually forcing me to focus on one thing, as I tend to let my creativity wander and drop things halfway if I don't have to finish something.

Thank you for asking, I hope this was a bit interesting. 🥰

12 notes

·

View notes