#David Chalmers

Text

David Chalmers, The Conscious Mind (1996), pg 16-17:

It seems reasonable to say that together, the psychological [third person behavioral view] and the phenomenal [first person experiential view] exhaust the mental. That is, every mental property is either a phenomenal property, a psychological property, or some combination of the two. Certainly, if we are concerned with those manifest properties of the mind that cry out for explanation, we find first, the varieties of conscious experience, and second, the causation of behavior. There is no third kind of manifest explanandum, and the first two sources of evidence - experience and behavior - provide no reason to believe in any third kind of nonphenomenal, nonfunctional properties.

Chalmers makes two errors here.

Just as the psychological view is incapable of detecting the existence of the phenomenal view and vice versa, neither view should be capable of detecting the existence of any third kind of view. Just because the psychological and phenomenal views are ordinarily incapable of detecting any third view does not rule out its existence. Let's call this hypothetical additional view the zeroth person perspective (Z).

Is there empirical evidence for the existence of Z? Yes. Advanced meditators learn to quiet their sensory inputs (the psychological view) as well as their internal perception and cognition (the phenomenal view.) In this deep altered meditative state, it is possible to perceive another internal voice. This is not the familiar inner phenomenal dialogue, but rather a presence that communicates without words or conscious thoughts, via direct mind-to-mind communication. So Z is distinct from the ordinary phenomenal view. It takes years of meditative practice to achieve the deep mental state needed to discern the presence of Z. EEGs of advanced meditators have demonstrated that gamma brain wave patterns actually change during deep meditative states (Barušs & Mossbridge, 2017).

How do we know that Z isn't just the phenomenal or psychological view in disguise? Because advanced meditators report that it is difficult to articulate what happens when they are in Z, and they discern many things during Z only a fraction of which they can recall with clarity once they leave meditation and return to the normal phenomenal and psychological view. This is not an uncommon occurrence during altered states of consciousness that bypass the normal process of memory formation. We know that Z is not simply a dream state because it has a different characteristic EEG signature.

#consciousness#philosophy of mind#david chalmers#the conscious mind#cognitive neuroscience#neuropsychology#cognitive science#phenomenal consciousness#meditation#advanced meditation#philosophy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Even when we have explained the performance of all the cognitive and behavioral functions in the vicinity of experience - perceptual discrimination, categorization, internal access, verbal report - there may still remain a further unanswered question: Why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience?"

-David Chalmers (On Consciousness)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

youtube

youtube

Energy is both ever-present and ever-changing.

It is both permanent and fluctuating.

It is both stable and fluid.

Contradictory? Energy is contradictory because energy is never a specific solid thing. It’s a force. It’s immaterial. It’s something you cannot perceive of but interact and engage with always. Constantly. Forever.

It’s energy. Energy is never created, never destroyed. Energy never stays still and yet we perceive it as if it does because we slow it down ourselves. That’s how powerful our minds actually are. How complex it is to exist, to engage, to interact, to experience. To be. And our minds do all of that naturally, instinctually, easily.

We not only generate the information that we perceive and experience, we also edit it in real time. And we turn what is a split-second event/moment/experience into a memory. Into something that has passed but can still be engaged with through the filter thought and emotion. That’s all mental. Every single bit of it.

But reality itself - regardless what it looks, sounds, feels like - is fleeting. It is already something new as nature is nothing but the process of transformation.

Moving - always in movement. Always transforming.

Always in a state and position of there and not there at the same time. Simultaneously 0 and 1 together.

We naturally gravitate towards nature ourselves as human beings because we’re meant to move with it because we are no different to it. We ARE nature too.

We’re not supposed to stay static. A permanence. A “thing” specific from any other “thing” and have a unique identification of from it. We think that we do but that’s because we’re so used to having a dual perspective. It’s the first perspective we ever have when we’re born. To have an “I” and then an “other”, completely ignoring the fact we couldn’t have either without both there at the time working in tandem like a machine. Clockwork. The functionality of the cogs. That’s what we are because that’s what we do. But we forget that we couldn’t do any of it without each other.

As energy and nature we are as a unit of being. One. We put what we experience as “reality” here with us because the whole point is to experience it as real. We have a dual perspective immediately as soon as we’re born because we’re fundamentally not dual. It would be impossible to experience anything if we really were because energy and nature doesn’t ever work alone - separately. There’s always the force and the yield. And nothing ever is or gets done without both interacting.

That’s what “reality” is. It’s interaction and motion. Action and reaction. Cause and effect. There is always an experience of something because there is always a process of change. Ever-present change. Existence is not ever still. It can’t be or it won’t be. It couldn’t be.

But as soon as you place an identification on any part of it that you focus on and zero in on - then it is being. Then it suddenly exists. Because you’ve conceived it.

This processing. This generating. This conceiving. It’s all natural. It’s so natural that we never notice we do it. Our natural state is of what everything else is - nature itself - but we possess a unique trait or skill that gives us dual perspective. Consciousness. Self-awareness. Self-enquiry. And as the theoretical physicist David Chalmers puts it - the hard problem is not figuring out what consciousness is or how any human being can possess consciousness. It is why are we conscious?

But if you ask me - not that you would - the answer is actually very simple. We are because we have to be. I say it’s that nothing would ever exist if we were not conscious. For me consciousness is a fundamental constant of reality. Of having a real experience. It’s a component that is so crucial to the computation of 0+1 that no equation would ever add up without it. You could spend an eternity trying to work it out from the outside looking in, but you’ll never reach a conclusion without the inside looking out. So let’s change the perspective. Not necessarily get rid of the paradigm but rearrange it somewhat. Try something new with it.

Consciousness is as fundamental as energy and nature. Not just in physics, but in every science. You simply cannot “science” without it, so why even try?

If you asked a reductionary classical and conventional physicist to even entertain the thought of combining the metaphysical with the mathematical, they would laugh at you. They would tell you that you’re insane. So it’s not that they can’t do it. It’s that they don’t want to do it because they’re so afraid of the truth. David Chalmers appears to be the only theoretical physicist and philosopher that will ask these questions where the metaphysics does have to be talked about. So, therefore, he is the only one worth my attention.

You know, being a neuroscientist really does sound incredibly exciting. But the restrictions man… the limited perceptions and understandings of the mind… it would drive me crazy to be in a field of science that’s so interesting but is ultimately boxed in lies. To study the brain and its infinite complex capabilities,… just to ignore the fact it is literally rendering itself along with everything else in its energetic field…

I couldn’t be apart of something so close-minded that’s meant to expand awareness of the Universe and that naturally, instinctually, easily does by default. Talking about the contradictions in the world - that’s a big one. I could not be apart of neuroscience because I’d be constantly questioning and challenging the intentions and purposes of studying the mind. I’d say things that were so far removed from the objective of the job that I know I would be fired on the spot for it. Even something as simple as “the mind isn’t in the brain, - the mind is omnipresent. It is everywhere.” Even that is too much for the current neuroscience because it’s too metaphysical. Too esoteric for it. No, I don’t belong in neuroscience. Nor even physics. In fact I don’t belong in any science. I’ll be interested in it, absolutely. But my views are just too unconventional and no scientist except this brave man would listen.

I’ve had a theory of everything for practically my whole life. I’ve been building on it more and more as I aged. But it’s too fucking OUT THERE to be heard. Even though it’s logical and based entirely on the information and evidence - both empirical and not - that we have already as well some strong predications from my claircognizance. It is ultimately very sound if one even dares to attempt to entertain metaphysics. Because until you can - it will always sound insane because unknown information is insane. People are afraid of what they don’t or can’t know. Well, I’ve never had the luxury of being able to deny what I shouldn’t know because my mind has never worked that way. I’ve always known shit I shouldn’t or couldn’t possibly know. I’ve always been aware but not of how or why. And it did always drive me crazy until I embraced it. Until I finally fucking accepted that yes, I am psychic. I do possess an expanded awareness than most people. Extra-sensory perceptive abilities very few people do. Abilities that have saved my life more times than I can count. That have led me down a path I couldn’t have possibly seen without it. That have always guided me. Eventually I had to accept that the shit that made me crazy was the same shit that made me able to be me. That only by getting lost could I ever be found again. That’s what a “spiritual awakening” is. A reckoning. And even someone like me - Miss INTP, that needs logic and facts and rationality - was metaphysical and therefore had to accept that the metaphysical exists. Because how the fuck can you deny your own being? I couldn’t deny any of that exists when it was who I am. I am metaphysical. I am spiritual. I am divine. I am multidimensional. There’s no way I can deny it when it’s literally my life every single waking second of it.

So yeah, consciousness is fundamental to me. The subjective is all I have. “Reality” cannot be without it. I don’t think Chalmers is “on to something”. I think he is fucking SPOT ON and people need to listen to him. And not just him. Robert Lanza. Alan Watts. Sadhguru. Spinoza. And even Albert Einstein to a degree as well. We’re all ultimately saying the same thing. Just differently. Majorly differently. Using different terms and definitions, metaphors and frames of reference.

But we are all ultimately saying the exact same thing.

That we have had it all very wrong to begin with. Classical physics. Newtonian physics. Darwinism.

We’ve got it all wrong as a collective consciousness.

And because we’re ultimately stuck for answers in science currently…. We have to do what scares us.

We have to start involving consciousness and talking about metaphysics seriously. It’s a philosophy of physics. A whole new paradigm of getting to the truth of how it all works. Nature. Energy. Us. Everything.

We’re at a standstill. Yes, we’re making discoveries and progress in everything else but the fundamental problem - the umbrella of the whole thing - is ?????.

We don’t know. Except we do - we just can’t face it.

We have to make consciousness a fundamental constant. As fundamental as gravity and electromagnetics. the strong and weak nuclear forces. We have to because we’re getting nowhere without it.

They’re afraid. They’re all fucking afraid. Cowards.

The only one that doesn’t seem to be is Chalmers.

#closer to truth#david chalmers#is consciousness fundamental?#the hard problem#consciousness#philosophy of physics#nature#energy#existence#dualism#neuroscience#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book of the Day - Reality +

Today’s Book of the Day is Reality + written by David Chalmers in 2022 and published by Norton & Company.

David Chalmers is a professor of philosophy and neural science and co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness at New York University. He wrote The Conscious Mind, The Character of Consciousness, and Constructing the World, and lives in New York.

Reality +, by David J.…

View On WordPress

#Book#Book Of The Day#book recommendation#book review#books#bookstagram#booktok#Center for Mind Brain and Consciousness#David Chalmers#New York University#Norton & Company#Philosophy#Raffaello Palandri#Reality +

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

★Conscious Exotica

⋆ 𝔇𝔦𝔠𝔱𝔦𝔬𝔫𝔞𝔯𝔶 ⋆

The term "conscious exotica" refers to hypothetical forms of consciousness that are different in fundamental ways from human and non-human animal consciousness as we currently understand it. This concept is often explored in the context of philosophical discussions about the nature of consciousness and its potential variations across different kinds of life forms or even artificial entities.

The exploration of "conscious exotica" involves considering entities that might have very different sensory inputs, cognitive structures, or forms of self-awareness than those found in earthly life forms. This could include, for example, hypothetical alien life forms with a fundamentally different biological makeup, or advanced artificial intelligences that experience the world in ways that are hard for humans to imagine.

The term also points towards a broader question in the philosophy of mind and cognitive science: What are the possible forms of consciousness, and how might they differ from the human experience? This inquiry challenges our understanding of consciousness by pushing the boundaries of what is considered conceivable or perceivable.

The term "conscious exotica" was coined by philosopher David Chalmers.

He uses it to discuss and categorize types of consciousness that are unusual, unknown, or differ significantly from human and animal consciousness as commonly observed. Chalmers is well-known for his work on the philosophy of mind, particularly regarding consciousness and the hard problem of consciousness—the question of why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience.

By introducing the concept of "conscious exotica," Chalmers invites exploration into the vast potential diversity of consciousness, which could include forms that are not observed on Earth and are perhaps not even currently imaginable by humans. This concept serves as a useful tool in theoretical discussions about the nature and limits of consciousness.

0 notes

Text

التقنية تتغير والعالم يتطور لكن البشر يظلون بشرًا✨

ما هذه المجموعة من المختارات تسألني؟ إنّها عددٌ من أعداد نشرة “صيد الشابكة” اِعرف أكثر عن النشرة هنا: ما هي نشرة “صيد الشابكة” ما مصادرها، وما غرضها؛ وما معنى الشابكة أصلًا؟! 🎣🌐

🎣🌐 صيد الشابكة العدد #25

رمضانكم كريم،

✔️ أتفق 👇🏽

قصص المتسولين أصحاب العقارات والأملاك والأرصدة البنكية ليست خرافات وأساطير بل وقائع حقيقية تداولتها الصحافة وتناقلها المجربون في المجتمع المغربي، لكن المؤكد أن محترفي…

View On WordPress

#Andy Clark#David Chalmers#Derrida#Dirt Media#Editor & Publisher#Foucault#hawas.me#kqv#Notified#obscurant terrorism#Rachel Smith#The Extended Mind#The Intrinsic Perspective#مكناس بريس#موقع مشروع الديمقراطية في الشرق الأوسط#مونتاج أحمد السعود#مدونة أحمد السعود#نشرة The Intrinsic Perspective#أحمد السعود#إبراهيم المبيضين#التلفزيون العمومي الجزائري#حواس دوت مي#علي الوكيلي

0 notes

Text

“Here’s my view of these things. Our minds are part of reality, but there’s a great deal of reality outside our minds. Reality contains our world and it may contain many others. We can build new worlds and new parts of reality. We know a little about reality, and we can try to know more. There may be parts of it that we can never know. Most importantly: Reality exists, independently of us. The truth matters. There are truths about reality, and we can try to find them. Even in an age of multiple realities, I still believe in objective reality.”

David J. Chalmers

#david chalmers#quote#consciousness#mind#awareness#reality#dimension#multiverse#visible spectrum#experience#perception#knowledge#levels of consciousness#stages of development#truth#objectivity#life#source

0 notes

Text

Onko dualismi realismia? Entä tekoälyn vallankumous?

David Chalmersin esitys Taorminassa 2023

Jatkan tässä artikkelissa katsausta toukokuussa 2023 pidettyyn tietoisuustieteen konferenssiin Sisilian Taorminassa. Nostin edellisessä artikkelissa esiin neurotieteilijä Anil Sethin pääpuheenvuoron sekä tietoisuuden teoriat. Nyt käsittelen David Chalmersin dualistista filosofiaa sekä hänen pääpuheenvuoroansa “Could a Large Language Model be…

View On WordPress

#chatgpt#david chalmers#dualismi#filosofia#idän filosofia#integroitu informaatioteoria#kognitio#logiikka#mieli ja materia#suuret kielimallit#taormina#tekoäly#tieteen filosofia#tieteen menetelmä#tietoisuus#tietoisuustieteet

0 notes

Text

It is true that we have no idea how a nonbiological system, such as a silicon computational system, could be conscious. But the fact is that we also have no idea how a biological system, such as a neural system, could be conscious. The gap is just as wide in both cases.

David Chalmers, Uploading: A Philosophical Analysis.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Bad philosophy" in een Anglo-Amerikaans handboek, en het mysterie van het bewustzijn: waarom zijn we er (bewust) in plaats van dat we er niet (bewust) zijn?

Afgelopen semester moest ik voor het vak 'Biologie, hersenen en gedrag' stukken studeren uit een Engelstalig handboek neuropsychologie. Introduction to brain and behavior, van de hand van Bryan Kolb en Ian Q. Whishaw, is een typisch, lijvig 'textbook' met talloze kadertjes, illustraties, verschillende tekstkleuren enzovoort. De twee Canadese neurowetenschappers dragen hun handboek op "aan het eerste neuron, onze voorouders, onze families en de studenten die dit boek lezen".

Wetenschappelijk is dit een goed boek, maar een heel klein gedeelte ervan gaat de eerder filosofische toer op en slaat daar de bal eerder mis.

Een concreet geval van 'slechte' filosofie door wetenschappers vinden we in Kolb en Whishaws handboek, in het subhoofdstuk "Perspectives on Brain and Behavior". Daar wordt de geschiedenis van de filosofie van de geest nogal simplistisch weergegeven in drie etappes en mondt ze voorspelbaar uit in de 'juiste' visie. Maar zoals ik verderop zal beargumenteren, is dit een sterk onvolledige weergave, die vele filosofische vragen onbeantwoord laat.

Vroeger begrepen we niet hoe de geest werkt, nu wel... of toch?

Kolb en Whishaw stellen dat er drie visies zijn op hoe we de menselijke geest en gedrag kunnen verklaren. Er is het mentalisme dat stelt dat er een soort immateriële entiteit is die ons gedrag én onze gedachten en ervaring stuurt. Deze entiteit wordt soms een ziel, geest of psyche genoemd. Kolb en Whishaw schrijven deze visie toe aan Aristoteles en het (historische) christendom.

Een tweede visie is het dualisme. Deze visie, toegeschreven aan René Descartes (1596-1650) zou stellen dat rationele, bewuste gedragingen en gedachten bestuurd worden door een immateriële entiteit, terwijl de werking van de rest van het lichaam verklaard kan worden door te kijken naar ons zenuwstelsel (onafhankelijk van die immateriële entiteit die wel onze geest controleert).

Een derde en laatste visie op geest en gedrag is volgens de auteurs het materialisme. Dit is het filosofisch standpunt dat zowel onze geest als ons gedrag verklaard kunnen worden door de werking van het zenuwstelsel, zonder te verwijzen naar een immateriële entiteit.

Het materialisme is de visie die het best ondersteund wordt door de hedendaagse wetenschap, aldus Kolb en Whishaw. De definitieve doodsteek voor het mentalisme en dualisme is volgens Kolb en Whishaw het gegeven dat bewustzijn geen binaire toestand is (ofwel is iemand bij bewustzijn, ofwel is iemand bewusteloos), maar een spectrum (van volledig bij bewustzijn over vermoeidheid, dronkenschap en slaap tot comateuze toestand en de dood). Dat er een spectrum is tussen volledig bewustzijn en volledige bewusteloosheid toont voor Kolb en Whishaw aan dat het mentalisme en dualisme niet kunnen kloppen: de verschillende gradaties tussen bewustzijn en bewusteloosheid kunnen beter verklaard worden vanuit het zenuwstelsel zelf dan vanuit een soort externe, immateriële entiteit die zwakker of sterker is.

'Easy' versus 'hard problem of consciousness'

Uit bovenstaande vergelijking van drie visies blijkt dat Kolb en Whishaw aan slechte filosofie doen. Meer bepaald slagen ze er niet in te bepalen of we hier een filosofische dan wel een wetenschappelijke discussie we hier voeren.

Gaat het hier over de wetenschappelijke discussie hoe de hersenen en het lichaam werken? Dan is het 'materialisme' inderdaad de correcte visie. Er is geen magisch onzichtbaar ding (zoals een ziel) nodig om te verklaren hoe het lichaam (waaronder de hersenen) werkt en ons gedrag en onze ervaring beïnvloedt.

Gaat het hier over de filosofische discussie over hoe de werking van het lichaam (waaronder de hersenen) leidt tot de subjectieve ervaring van bewustzijn die we allemaal zelf hebben? Dan kunnen we zeker niet zeggen dat het 'materialisme' het laatste woord heeft. David Chalmers, de Australische filosoof die het filosofische debat over bewustzijn en geesten nieuw leven inblies, spreekt van een 'hard problem of consciousness'. Dat filosofische probleem is precies de vraag die ik hier zojuist stelde: hoe is het mogelijk dat mensen bewustzijn en subjectieve ervaring hebben? Hoe komt het dat we niet een soort zombies zijn (die geen subjectieve ervaring hebben en er dus nooit over konden nadenken)?

Chalmers contrasteert dat 'hard problem of consciousness' met het 'easy problem of consciousness'. Dat 'easy problem' is de vraag hoe de hersenen en het zenuwstelsel werken. Deze vraag is, zoals gezegd, een wetenschappelijke vraag, die 'gemakkelijk' is omdat ze door voldoende onderzoek beantwoord kan worden. Het 'hard problem' is daarentegen de filosofische vraag hoe het mogelijk is dat we überhaupt subjectieve ervaring hebben.

Het verschil tussen wetenschap en filosofie

Kolb en Whishaw slagen er, zoals zovelen tegenwoordig, niet in om het verschil te zien tussen wetenschappelijke en filosofische discussies over hersenen, gedrag en geest. Verwonderlijk is dit nu niet: filosofie is in veel wetenschappelijke opleidingen nog altijd afwezig (of hoogstens een keuzevak). Het verschil tussen wetenschap en filosofie wordt miskend en onderkend. Terwijl grote (natuur)wetenschappers zoals Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr en Werner Heisenberg halfweg de twintigste eeuw nog aan serieuze (wetenschaps)filosofische reflectie deden, beweren enkele decennia later wetenschapspopularisators zoals Neil DeGrasse Tyson en Stephen Hawking zonder veel gêne dat filosofie verouderd is; overbodig gemaakt door de wetenschap.

Opvallend genoeg wordt het verschil tussen wetenschap en religie wél algemeen erkend. Ook Kolb en Whishaw vermelden het expliciet:

Some people may question materialism’s tenet that only the brain is responsible for behavior because they think it denies religion. The theory, however, is neutral with respect to religion. [...] [Many] behavioral scientists hold religious beliefs [...]. Science is not a belief system but rather a set of procedures designed to allow investigators to confirm answers to a question independently. (Kolb en Whishaw, p. 13)

Zoals Kolb en Whishaw terecht opmerken, is de vraag hoe het lichaam (waaronder de hersenen) werken geen religieuze vraag. Dat bijvoorbeeld de prefrontale cortex in sterke mate verantwoordelijk is voor planning en redeneren, zegt niets over de waarheid of onwaarheid van religieus geloof. Het is daarom des te merkwaardiger dat Kolb en Whishaw (en zovele anderen) niet inzien dat de werking van de hersenen evenmin iets zegt over de (on)waarheid van filosofische opvattingen (zoals mentalisme, dualisme of materialisme).

De vraag hoe het lichaam (waaronder de hersenen) werkt, is een wetenschappelijke vraag, omdat er maar één 'juist' antwoord op de vraag mogelijk is - zelfs al weten we het nog niet helemaal. Het hard problem of consciousness is dan weer een filosofische vraag, omdat er niet zomaar één 'juist' antwoord op mogelijk is.

Hoe komt het dat we bewustzijn en subjectieve ervaring hebben?

Welke antwoorden zijn er zoal voorgesteld als antwoord op het hard problem of consciousness? Hoe beantwoorden zij de vraag hoe het komt dat mensen subjectieve ervaring en bewustzijn hebben? Er zijn twee soorten voorgestelde oplossingen voor het probleem. De eerste klasse oplossingen probeert de vraag te beantwoorden door een theorie te geven over wat bewustzijn en materie eigenlijk zijn. Zo zijn er het idealisme (alleen bewustzijn bestaat), dualisme (bewustzijn en materie zijn fundamenteel verschillend), zwak reductionisme (alleen materie bestaat, zelfs al begrijpen we niet waarom er toch bewustzijn is) panpsychisme en neutraal monisme (materie hééft bewustzijn - het zit erin).

Een andere categorie filosofische standpunten verwerpt het 'hard problem of consciousness'. Men verwerpt dan het onderscheid tussen het 'hard' en 'easy problem of consciousness' dat ik hierboven schetste. Volgens zulke theorieën is de vraag hoe het komt dat we subjectieve ervaring hebben dus geen filosofisch probleem, maar een wetenschappelijk, neuropsychologisch probleem (= sterk reductionisme) of zelfs helemaal geen probleem, een illusie (= eliminatief materialisme).

'Zurück zu den Sachen selbst': fenomenologie meets filosofie van de geest

Wie heeft er nu gelijk? Wel, zoals gezegd is het een filosofische discussie, dus er is niet één 'juist' antwoord. In de rest van dit artikel geef ik mijn persoonlijke, filosofische visie op dit probleem, op het moment van het schrijven van dit artikel.

'Fenomenologie' is een woord dat voor mensen zonder filosofische achtergrondkennis of interesse nogal bedreigend complex overkomt. Fenomenologie is echter niet veel meer of minder dan de studie van ervaring en bewustzijn - zoals we deze spontaan ervaren. De fenomenologie ontstond in Europa in de twintigste eeuw. Fenomenologen gaan 'terug naar de dingen zelf' zoals we ze spontaan ervaren.

Laten we het hard problem of consciousness eens 'fenomenologisch' bekijken. We sommen even de volgende zaken op die we kunnen zeggen over onze ervaring en ons bewustzijn. Deze zaken klinken onnoemelijk banaal, maar hebben tegelijk grote filosofische relevantie:

Ik ben een mens.

Ik ben mezelf.

Ik leef, ik ben niet dood.

Ik ben al heel m'n leven mezelf. Ik zal ook de rest van m'n leven mezelf zijn.

Ik ben één persoon en niet meerdere.

Ik heb één leven en geen meerdere. Als ik sterf, dan is het waarschijnlijk gedaan met mijn ervaring en bewustzijn.

Als ik slaap, dan ben ik er nog. Anderen die niet slapen, zouden dat kunnen zien.

Ik kan onmogelijk rechtstreeks ervaren wat het is om iemand anders te zijn.

Al deze zaken gelden ook voor alle andere mensen.

Zoals gezegd zijn dit uiteraard triviale uitspraken. Iedereen erkent ze onmiddellijk en neemt ze in het alledaagse leven spontaan aan. Als we ze echter plaatsen naast wetenschappelijke kennis over het zenuwstelsel enerzijds, en het 'hard problem of consciousness' anderzijds, wordt het spannender.

Wat zit er nu eigenlijk in de structuur van onze lichamen, onze hersenen of wat dan ook, dat er toe had moeten leiden dat net al deze bovenstaande gegevens kloppen? Het volgende is geen retorische of emotionele, maar een serieuze filosofische vraag: waarom ben ik mezelf, die specifieke persoon, en niet een ander? Er zijn meer dan zeven miljard mensen in leven, nog meer mensen zijn al overleden, en zullen er waarschijnlijk nog miljarden komen na ons. Tussen die tientallen miljarden historische, hedendaagse en toekomstige mensen ben jij jij. Waarom is dit zo? Waarom ben ik mezelf en niet een jager-verzamelaar 10 000 jaar geleden, een middeleeuwse boer in Zuid-Amerika of een ruimtekolonist in het jaar 2500? Waarom ik, tussenin al die tientallen miljarden? En waarom ben ik een mens en geen ander dier? En waarom heeft iedereen één geest en geen meerdere? Waarom hebben we één leven en geen meerdere? Waarom is er niet één geest voor de hele mensheid - we zouden met zo'n 'hivemind' toch net zo goed kunnen overleven? En - met een knipoog naar de ultieme filosofische vraag - waarom ben ik er (met bewustzijn) in plaats van dat ik er niet ben (en zo geen bewustzijn zou hebben)?

Er zit niets 'ingeschreven' in de materie dat ertoe had moeten leiden dat ik ben (in plaats van niet ben), dat ik juist mezelf (en geen ander) ben, enzovoort. Er is niets in de materie zelf dat onvermijdelijk ertoe leidt dat alle fenomenologische gegevens zo hadden moeten zijn zoals in het lijstje dat ik bovenaan geschreven heb.

Een triviaal antwoord op deze vragen is: kijk gewoon rond je, en je ziet dat je jezelf bent en niet bijvoorbeeld je oma of de president van Amerika. Maar mijn vragen bedoelde ik niet in die zin van "wie ben jij eigenlijk?" Met "waarom ben jij jij?" bedoel ik: waarom ben jij jezelf terwijl je evengoed een van die miljarden anderen had kunnen zijn - of helemaal niet had kunnen zijn? "Niet hoe de wereld is, is het mystieke, maar dat zij is", schreef Ludwig Wittgenstein ooit. Ik zou dit hier lichtjes aanpassen: "Niet dat er bewustzijn is, is het mystieke, maar hoe zij is".

Het uitgebreide hard problem of consciousness

Dat is wat ik zelf het 'uitgebreide hard problem of consciousness' noem. Het is volgens mij het resultaat van een combinatie van fenomenologie en het hard problem of consciousness. Zoals gezegd is Chalmers' hard problem de vraag hoe het mogelijk is dat mensen bewustzijn en ervaringen hebben. Het uitgebreide hard problem of consciousness is dan de vraag hoe het mogelijk is dat mensen bewustzijn en ervaringen hebben, die dan ook nog eens de specifieke vormen aannemen die ze aannemen (bv. ik ben mezelf, ik ben één persoon, ...).

Solipsism vs. the world

Een mogelijke oplossing voor het uitgebreide hard problem of consciousness is het solipsisme. De filosofie van het solipsisme zegt dat alleen mijn subjectieve ervaring zeker bestaat. Johan Braeckman en Etienne Vermeersch omschrijven het solipsisme als volgt in De rivier van Herakleitos:

Ik zie mensen rondom mij die zich gedragen alsof ze een 'geest' hebben, net zoals ik die bezit. Met andere woorden, ik zie mensen die mij de indruk geven plezier te hebben, pijn te ervaren, verlangens te koesteren... Ik ga ervan uit dat zij hun plezier, hun pijn en verlangens ervaren zoals ik mijn plezier, pijn en verlangens ervaar. Maar zekerheid hierover kan ik nooit hebben, aangezien ik onmogelijk hun pijn, plezier en verlangens kan voelen. Ik kan me min of meer inleven in hun ervaringen, [...] maar ik blijf gevangen in mijn eigen perceptie daarvan. (p. 141)

De filosofie van het solipsisme zegt dat alleen mijn subjectieve ervaring bestaat. De subjectieve ervaring van alle anderen bestaat niet, want ik kan alleen mijn eigen subjectieve ervaring waarnemen.

Het solipsisme klinkt als een absurde, contra-intuïtieve theorie, maar het beantwoordt wel degelijk het uitgebreide hard problem of consciousness. Het solipsisme doet dit door erop te wijzen dat aangezien ik het enige bewustzijn ben dat met zekerheid bestaat, het niet anders kan dan dat mijn bewustzijn al zijn huidige fenomenologische eigenschappen (ik ben mezelf en geen ander, ik ben één persoon, enzovoort) aanneemt. Alle eigenschappen van het bewustzijn kunnen niet anders zijn dan wat ze zijn, omdat ik nu eenmaal het enige bestaande bewustzijn ben.

Er zijn veel pogingen gedaan om het solipsisme te bekritiseren, wellicht omdat het zo absurd klinkt en omdat het doet denken aan de houding van een peuter: die lijkt zich te gedragen alsof alleen hijzelf bestaat en de rest van de wereld niet. Naarmate mensen opgroeien, voelen ze 'intuïtief' dat deze theorie niet klopt: ook anderen en de buitenwereld bestaan en ook anderen hebben gevoelens en ervaringen zoals ik die zelf heb.

Dat is dan ook de beste weerlegging van het solipsisme: de vaststelling dat je een mens bent. Menselijk al te menselijk. Fysiologen die bijvoorbeeld de werking van het hart ontraadselden, hebben terecht aangenomen dat het menselijk hart op dezelfde manier werkt in ieder mens. Wat geldt voor het hart, moet ook gelden voor het hoofd. Aangezien andere mensen, op grond van het feit dat ze tot dezelfde biologische soort behoren, exact dezelfde fysiologische opbouw hebben, moeten ze ook wel exact hetzelfde soort subjectieve ervaringen en bewustzijn hebben als ons. Het bestaan van cardiologische en neurologische stoornissen doet niets af van de geldigheid van deze analogische redenering, maar bevestigt ze juist.

Aangezien het solipsisme niet kan kloppen, moet er dus een ander antwoord zijn op het uitgebreide hard problem of consciousness. De eerder besproken voorgestelde antwoorden op het 'gewone' hard problem of consciousness, zoals dualisme en panpsychisme, zijn hierbij ontoereikend. Deze theorieën proberen immers enkel te verklaren hoe het mogelijk is dat er bewustzijn en subjectieve ervaring is en niet hoe het komt dat deze bewustzijn en subjectiviteit ook nog eens zijn specifieke vormen (zie lijstje hierboven) aanneemt.

Er moet iets zijn dat ervoor zorgt dat we subjectieve ervaringen hebben in de specifieke vormen waarin we ze hebben. Wat is dit iets dan, daarvoor zorgt?

Het mysterie van het bewustzijn

Misschien wel het meest overtuigende antwoord op deze vraag komt niet vanuit de academische filosofie, maar vanuit de wereldreligies.

Een centrale overtuiging in het boeddhisme is dat van het 'afhankelijk ontstaan' (pratītyasamutpāda). Deze overtuiging is duivels eenvoudig: dingen bestaan omdat andere dingen bestaan. Als dit bestaat, dan bestaat dat ook, als dit er niet meer is, dan is dat er ook niet meer. Alles is afhankelijk van alles. We hebben dus bewustzijn simpelweg als gevolg van andere dingen - wat die dingen verder ook mogen zijn.

Een ander mogelijk antwoord op de vraag hoe het komt dat wij überhaupt subjectieve ervaringen hebben, is Thomas Aquinas' derde argument voor het bestaan van God: het argument uit contingentie. Alles had evengoed niet kunnen bestaan, maar het bestaat toch, daarom moet er iets zijn dat alles doet bestaan. Dit iets 'noemen wij God', schreef Aquinas. Het argument uit contingentie gaat over alles, dus het moet ook gelden voor ons bewustzijn: we hadden evengoed geen bewustzijn kunnen hebben, maar we hebben het toch. Er moet dus iets zijn dat ons bewustzijn geeft. Dit iets noemen wij God.

Op het eerste zicht kunnen de boeddhistische en de theïstische visie niet meer verschillen. Aquinas schrijft dat er iets is (God) die alles altijd in stand houdt. De boeddhistische doctrine van afhankelijk ontstaan leert daarentegen dat alle dingen (waaronder ons bewustzijn) afhangen van andere dingen. Maar die 'andere dingen', zijn zeker niet noodzakelijk God zoals in het theïsme, stelt het boeddhisme.

Toch zijn deze visies eigenlijk niet meer zo verschillend wanneer we het puur filosofisch bekijken. Zowel God (theïsme) als de andere dingen die dingen afhankelijk doen ontstaan (boeddhisme) zijn een antwoord op de vraag hoe de wereld (en dus ook het bewustzijn) is ontstaan. Zowel God als de afhankelijk ontstane andere dingen zijn oneindig en wellicht onbegrijpelijk.

Het verschil is hier misschien dus niet zozeer filosofisch, maar vooral cultureel: theïsten aanbidden God, boeddhisten niet. Sowieso is er iets dat ons bewustzijn mogelijk maakt, en sowieso blijft dat dat iets mysterieus. Eigenlijk maakt het niet zoveel uit of je dat dan God, afhankelijk ontstaan, Brahma, Shangdi, Zeus, Thor of gelijk wat anders noemt: het blijft even geheimzinnig!

#filosofie#filosofie van de geest#philosophy of mind#David Chalmers#idealism#dualism#materialism#solipsism#metafysica#filosofie van de religie

0 notes

Video

youtube

Fonte: https://www.spreaker.com/user/1503831... In questa puntata, lo spunto filosofico è uno zombie. Che cosa sono gli zombie? Cosa possono suggerirci, a livello di filosofia e di cultura? Proveremo a percorrere un viaggio, dalle origini Vudù e haitiane a quelle cinematografiche, da Romero a Darabont. Poi, volteremo le carte, parlando dello zombie filosofico di David Chalmers, per sprofondare - almeno un po' - in uno dei più grandi misteri dell'essere umano. La coscienza.

#filosofia#horror#podcast#stanze di sofia#zombie filosofico#filosofia degli zombie#david chalmers#george romero#cartesio#spinoza

0 notes

Text

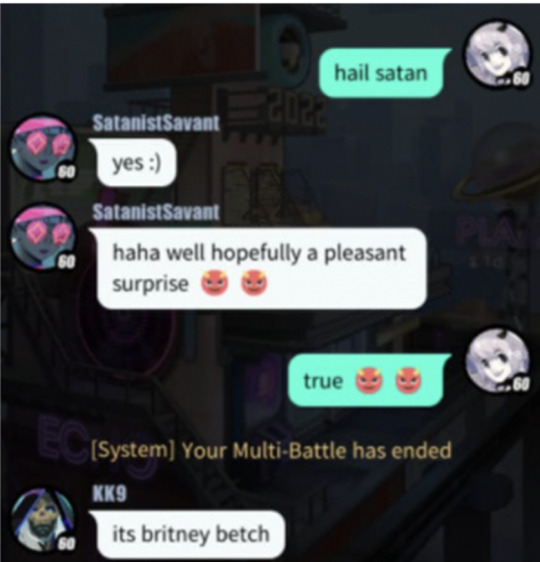

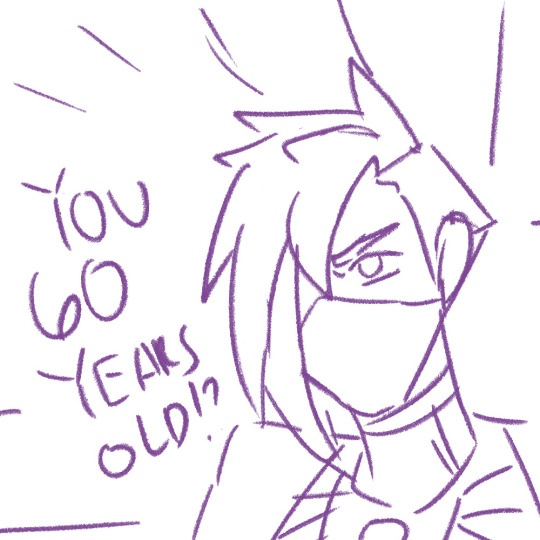

Dislyte world chat shitpost and meme redraw

Pt 2

I only have these so far but if i find more stupid shit in chat later in the future i might do more

#lmao#fuck#fanart#shitpost#dislyte#q dislyte#pritzker dislyte#tiye dislyte#yuzhi dislyte#chuyi dislyte#hyde dislyte#chalmers dislyte#falken dislyte#dislyte meme#dislyte shitpost#david dislyte

153 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 1/3

Fandom: Dislyte (Video Game)

Relationships: Bardon/Freddy, Hall/Leon, Bardon/Lucas, Bardon/Hall, Freddy/Leon

Characters: Bardon, Lucas, Mona, David, Chalmer, Freddy, Leon, Hall, Anisedora, Kara, Sander, Falken

Letting out a long tired sigh, Bardon felt something heavy on his chest, and again, it was that strange bad feeling he kept having, but this time, it was too intense for him to ignore, he turned his head around the apartment, realizing that all of his friends left, and just like that, an idea came to mind.

@pinkniz

Here is the fic I talked about!

#My very first Dislyte fic!#and its about my crackship lol#Dislyte#Bardon#Freddy#Barddy#Lucas#Mona#David#Chalmer#Leon#Hall#Anisedora#Kara#Sander#Falken#yeah I got the whole cast here lol#I mean they will contribute to the story#chapter1#Reach for my hand

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 july 2022

David Cumming (Charles Cholmondeley and others), Claire-Marie Hall (Jean Leslie and others), Natasha Hodgson (Ewen Montagu and others), Jak Malone (Hester Leggett and others), Anouk Chalmers (u/s Johnny Bevan and others).

also here's the new act 1 finale added during the riverside studios run

#operation mincemeat musical#operation mincemeat#musicals#david cumming#claire marie hall#natasha hodgson#anouk chalmers#jak malone#audio#i kind of miss 'let me die in velvet' ngl but i can see why they changed it#still... real loss not to see claire in lingerie any more...

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

most well adjusted australian philosophy professor

3 notes

·

View notes