#philosophy of mind

Text

You probably know that humans can experience “phantom limbs,” but did you know that the limbs of an octopus can have a “phantom body”? If you cut off an octopus’ tentacle, it will try to feed a mouth that is no longer there. A severed octopus tentacle also curls up when it’s exposed to negative stimuli like acid. Essentially, if an octopus dies and its tentacle is cut off, the tentacle can outlive the original animal by a whole hour.

Octopi have as many as 130 million neurons, but the vast majority are located in their limbs, not their brains. Their mind is “distributed.” That is fundamentally unlike the human mind. We have muscle memory, but our arms can’t move completely independently of our brains.

What does this mean for octopus consciousness? Well… we don’t know. There’s no way to observe or deduce via experiment what it’s like to be a particular animal. We can see how they behave, but we won’t ever see the world through their eyes. Science can study what is outside, but not what’s inside. So, animal consciousness isn’t really the domain of science.

As is always the case, philosophers have attempted to do what scientists cannot. The philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith has a really great way of explaining what’s at stake: “Octopuses let us ask which features of our minds can we expect to be universal whenever intelligence arises in the universe, and which are unique to us.”

There’s a decent chance you’ve seen a popular Tumblr post about Umwelt Theory—the idea that animals have access to senses that we do not. Smells too refined for our noses, pitches too high for our ears, colors outside the range of our eyes. But the inner worlds of animals might be even stranger than that. The postmortem movement of octopus limbs suggests that some animal minds might be fundamentally different from ours. Simply put, it’s not just that some animals have access to sensations that we will never feel. They might have access to types of thoughts that we will never be able to think.

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Which of the following statements best describes your sense of identity?

❤️: I'm an individual with a stable, firm sense of identity. I know exactly who I am and can easily define myself.

💛: I'm an individual with a fluid sense of identity that keeps evolving over time. However, there is a "core me" that remains the same, and I have at least a vague idea of who this person is.

💚: My sense of identity is fluid, and I contain multitudes. I am not sure which me is the real me or if there is a real me at all, which causes me a bit of distress.

💜: My sense of identity is fluid, and I contain multitudes. This does not cause me distress as I don't seek to define myself.

🖤: I frequently experience being more of a 'pure awareness' than a person. Oftentimes I find myself observing the world rather than interacting with it. Any identity I take on in this life feels like a mask / a temporary role.

💙: Something else.

Feel free to expand on your choice in the tags/comments :)

Reblog for a bigger sample size!

#neurodivergent#neurotypical#self-concept#psychology#philosophy of mind#actually autistic#actually adhd#identity#ego#tumblr polls#tumbler polls

427 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the Brain a Driver or a Steering Wheel?

This three part series summarizes what science knows, or thinks it knows, about consciousness. In Part 1 What Does Quantum Physics Imply About Consciousness? we looked at why several giants in quantum physics - Schrodinger, Heisenberg, Von Neumann and others - believed consciousness is fundamental to reality. In Part 2 Where Does Consciousness Come From? we learned the "dirty little secret" of neuroscience: it still hasn't got a clue how electrical activity in the brain results in consciousness.

In this concluding part of the series we will look at how a person can have a vivid conscious experience even when their brain is highly dysfunctional. These medically documented oddities challenge the materialist view that the brain produces consciousness.

Before proceeding, let's be clear what what is meant by "consciousness". For brevity, we'll keep things simple. One way of looking at consciousness is from the perspective of an outside observer (e.g., "conscious organisms use their senses to notice differences in their environment and act on their goals.") This outside-looking-in view is called behavioral consciousness (aka psychological consciousness). The other way of looking at it is the familiar first-person perspective of what it feels like to exist; this inside-looking-out view is called phenomenal consciousness (Barušs, 2023). This series is only discussing phenomenal consciousness.

Ready? Let’s go!

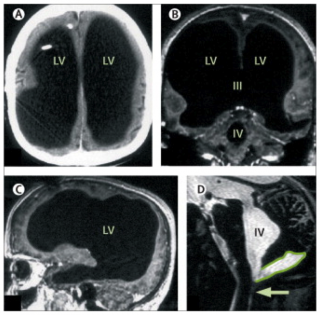

Source: Caltech Brain Imaging Center

A Hole in the Head

Epilepsy is a terrible disease in which electrical storms in the brain trigger seizures. For some people these seizures are so prolonged and frequent that drastic action is needed to save their lives. One such procedure is called a hemispherectomy, the removal or disconnection of half the brain. Above is an MRI image of a child who has undergone the procedure.

You might think that such radical surgery would profoundly alter the memory, personality, and cognitive abilities of the patient.

You would be wrong. One child who underwent the procedure at age 5 went on to attend college and graduate school, demonstrating above average intelligence and language abilities despite removal of the left hemisphere (the zone of the brain typically identified with language.) A study of 58 children from 1968 to 1996 found no significant long-term effects on memory, personality or humor, and minimal changes in cognitive function after hemispherectomy.

You might think that, at best, only a child could successfully undergo this procedure. Surely such surgery would kill an adult?

You would be wrong again. Consider the case of Ahad Israfil, an adult who suffered an accidental gunshot to the head and successfully underwent the procedure to remove his right cerebral hemisphere. Amazingly, after the five hour operation he tried to speak and went on to regain a large measure of functionality (although he did require use of a wheelchair afterwards.)

Another radical epilepsy procedure, a corpus collosotomy, leaves the hemispheres intact but severs the connections between them. For decades it was believed that these split-brain patients developed divided consciousness, but more recent research disputes this notion. Researchers found that, despite physically blocking all neuronal communication between the two hemispheres, the brain somehow still maintains a single unified consciousness. How it manages this feat remains a complete mystery. Recent research on how psychedelic drugs affect the brain hints that the brain might have methods other than biochemical agents for internal communication, although as yet we haven't an inkling as to what those might be.

So what's the smallest scrape of brain you need to live? Consider the case of a 44-year-old white collar worker, married with two children and with an IQ of 75. Two weeks after noticing some mild weakness in one leg the man went to see his doctor. The doc ordered a routine MRI scan of the man's cranium, and this is what it showed.

Source: The Lancet

What you are seeing here is a giant empty cavity where most of the patient's brain should be. Fully three quarters of his brain volume is missing, most likely due to a bout of hydrocephalus he experienced when he was six months old.

Last Words

Many unusual phenomena have been observed as life draws to an end. We're going to look at two deathbed anomalies that have neurological implications.

The first is terminal lucidity, sometimes called paradoxical lucidity. First studied in 2009, terminal lucidity refers to the spontaneous return of lucid communication in patients who were no longer thought to be medically capable of normal verbal communication due to irreversible neurological deterioration (e.g., Alzheimers, meningitis, Parkinson's, strokes.) Here are three examples:

A 78-year-old woman, left severely disabled and unable to speak by a stroke, spoke coherently for the first time in two years by asking her daughter and caregiver to take her home. She died later that evening.

A 92-year-old woman with advanced Alzheimer’s disease hadn’t recognized her family for years, but the day before her death, she had a pleasantly bright conversation with them, recalling everyone’s name. She was even aware of her own age and where she’d been living all this time.

A young man suffering from AIDS-related dementia and blinded by the disease who regained both his lucidity and apparently his eyesight as well to say farewell to his boyfriend and caregiver the day before his death.

Terminal lucidity has been reported for centuries. A historical review found 83 case reports spanning the past 250 years. It was much more commonly reported in the 19th Century (as a sign that death was near, not as a phenomenon in its own right) before the materialist bias in the medical profession caused a chilling effect during the 20th Century. Only during the past 15 years has any systematic effort been made to study this medical anomaly. As a data point on its possible prevalence a survey of 45 Canadian palliative caregivers found that 33% of them had witnessed at least one case of terminal lucidity within the past year. Other surveys found have that the rate of prevalence is higher if measured over a longer time window than one year, suggesting that, while uncommon, terminal lucidity isn't particularly rare.

Terminal lucidity is difficult to study, in part because of ethical challenges in obtaining consent from neurocompromised individuals, and in part because its recent identification as a research topic presents delineation problems. However, the promise of identifying new neurological pathways in the brains of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's patients has gotten a lot of attention. In 2018 the US National Institute on Aging (NIA) announced two funding opportunites to advance this nascent science.

Due to the newness of this topic there will continue be challenges with the data for some time to come. However, its impact on eyewitnesses is indisputably profound.

Near Death Experiences

The second deathbed anomaly we will take a look at are Near-Death Experiences (NDEs.) These are extraordinary and deeply personal psychological experiences that typically (but not always) occur during life-threatening emergencies such as cardiac arrest, falls, automobile accidents, or other traumatic events; they are also occasionally reported during general anesthesia. Much of the research in this area has focused on cardiac arrest cases because these patients are unconscious and have little to no EEG brain wave activity, making it difficult to account for how the brain could sustain the electrical activity needed to perceive and remember the NDE. This makes NDEs an important edge case for consciousness science.

NDEs are surprisingly common. A 2011 study published by the New York Academy of Sciences estimated that over 9 million people in the United States have experienced an NDE. Multiple studies have found that around 17% of cardiac arrest survivors report an NDE.

There is a remarkable consistency across NDE cases, with experiencers typically reporting one or more of the following:

The sensation of floating above their bodies watching resuscitation efforts, sometimes able to recall details of medical procedures and ER/hallway conversations they should not have been aware of;

Heightened sensations, occasionally including the ability of blind and deaf people to see and hear;

Extremely rapid mental processing;

The perception of passing through something like a tunnel;

A hyper-vivid life review, described by many experiencers as "more real than real";

Transcendent visions of an afterlife;

Encounters with deceased loved ones, sometimes including people the experiencer didn’t know were dead; and

Encounters with spiritual entities, sometimes in contradiction to their personal belief systems.

Of particular interest is a type of NDE called a veridical NDE. These are NDEs in which the experiencer describes events that occurred during the period when they had minimal or no brain activity and should not have been perceived or remembered if the brain were the source of phenomenal consciousness. These represent about 48% of all NDE accounts (Greyson 2010). Here are a few first-hand NDE reports.

A 62-year-old aircraft mechanic during a cardiac arrest (from Sabom 1982, pp. 35, 37)

A 23-year-old crash-rescue firefighter in the USAF caught by a powerful explosion from a crashed B-52 (from Greyson 2021, pg. 27-29)

An 18-year-old boy describes what it was like to nearly drown (from the IANDS website)

There are thousands more first person NDE accounts published by the International Association for Near-Death Studies and at the NDE Research Foundation. The reason so many NDE accounts exist is because the experience is so profound that survivors often feel compelled to write as a coping method. Multiple studies have found that NDEs are more often than not life-changing events.

A full discussion of NDEs is beyond the scope of this post. For a good general introduction, I highly recommend After: What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond by Bruce Greyson, MD (2021).

The Materialist Response

Materialists have offered up a number of psychological and physiological models for NDEs, but none of them fits all the data. These include:

People's overactive imaginations. Sabom (1982) was a skeptical cardiologist who set out to prove this hypothesis by asking cardiac arrest survivors who did not experience NDEs to imagine how the resuscitation process worked, then comparing those accounts with the veridical NDE accounts. He found that the veridical NDE accounts were highly accurate (0% errors), whereas 87% of the imagined resuscitation procedures contained at least one major error. Sabom became convinced that NDEs are real. His findings were replicated by Holden and Joesten (1990) and Sartori (2008) who reviewed veridical NDE accounts in hospital settings (n = 93) and found them to be 92% completely accurate, 6% partially accurate, and 1% completely inaccurate.

NDEs are just hallucinations or seizures. The problem here is that hallucinations and seizures are phenomena with well-defined clinical features that do not match those of NDEs. Hallucinations are not accurate descriptions of verifiable events, but veridical NDEs are.

NDEs are the result of electrical activity in the dying brain. The EEGs of experiencers in cardiac arrest show that no well-defined electrical activity was occurring that could have supported the formation or retention of memories during the NDE. These people were unconscious and should not have remembered anything.

NDEs are the product of dream-like or REM activity. Problem: many NDEs occur under general anesthesia, which suppresses dreams and REM activity. So this explanation cannot be correct.

NDEs result from decreased oxygen levels in the brain. Two problems here: 1) The medical effects of oxygen deprivation are well known, and they do not match the clinical presentation of NDEs. 2) The oxygen levels of people in NDEs (e.g., during general anesthesia) has been shown to be the same or greater than people who didn’t experience NDEs.

NDEs are the side effects of medications or chemicals produced in the brain (e.g. ketamine or DMT). The problem here is that people who are given medications in hospital settings tend to report fewer NDEs, not more; and drugs like ketamine have known effects that are not observed in NDEs. The leading advocate for the ketamine model conceded after years of research that ketamine does not produce NDEs (Corraza and Schifano, 2010).

Summing Up

In coming to the end of this series, let's sum up what we discussed.

Consciousness might be wired into the physical universe at fundamental level, as an integral part of quantum mechanics. Certainly several leading figures in physics thought so - Schrodinger, Heisenberg, Von Neumann, and more recently Nobel Laureate Roger Penrose and Henry Stapp.

Materialist propaganda notwithstanding, neuroscience is no closer to identifying Neural Correlates of Consciousness (NCCs) than it was when it started. The source of consciousness remains one of the greatest mysteries in science.

Meanwhile, medical evidence continues to pile up that there is something deeply amiss with the materialist belief that consciousness is produced by the brain. In a sense, the challenge that NDEs and Terminal Lucidity pose to consciousness science is analogous to the challenge that Dark Matter poses to physics, in that they suggest that the mind-brain identity model of classic materialist psychology may need to be rethought to adequately explain these phenomena.

Ever since the Greeks, science has sought to explain nature entirely in physical terms, without invoking theism. It has been spectacularly successful - particularly in the physical sciences - but at the cost of excluding consciousness along with the gods (Nagel, 2012). What I have tried to do in this series is to show that a very credible argument can be made that materialism has the arrow of causality backwards: the brain is not the driver of consciousness, it's the steering wheel.

I don't think we are yet ready to say what consciousness is. Much more research is needed. I'm not making the case for panpsychism, for instance - but I do think consciousness researchers need to throw off the assumption drag of materialism before they're going to make any real progress.

It will be up to you, the scientists of tomorrow, to make those discoveries. That's why I'm posting this to Tumblr rather than an academic journal; young people need to hear what's being discovered, and the opportunities that these discoveries represent for up and coming scientists.

Never has Planck's Principle been more apt: science advances one funeral at a time.

Good luck.

For Further Reading

Barušs, Imants & Mossbridge, Julia (2017). Transcendent Mind: Rethinking the Science of Consciousness. American Psychological Association, Washington DC.

Barušs, Imants (2023). Death as an Altered State of Consciousness: A Scientific Approach. American Psychological Association, Washington DC.

Batthyány, Alexander (2023). Threshold: Terminal Lucidity and the Border of Life and Death. St. Martin's Essentials, New York.

Becker, Carl B. (1993). Paranormal Experience and Survival of Death. State University of New York Press, Albany NY.

Greyson, Bruce (2021). After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond. St. Martin's Essentials, New York.

Kelly, Edward F.; Kelly, Emily Williams; Crabtree, Adam; Gauld, Alan; Grosso, Michael; & Greyson, Bruce (2007). Irreducible Mind: Toward a Psychology for the 21st Century. Rowman & Littlefield, New York.

Moody, Raymond (1975). Life After Life. Bantam/Mockingbird, Covington GA.

Moreira-Almeida, Alexander; de Abreu Costa, Marianna; & Coelho, Humberto S. (2022). Science of Life After Death. Springer Briefs in Psychology, Cham Switzerland.

Penfield, Wilder (1975). Mystery of the Mind: A Critical Study of Consciousness and the Human Brain. Princeton Legacy Library, Princeton NJ.

Sabom, Michael (1982). Recollections of Death: A Medical Investigation. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

van Lommel, Pim (2010). Consciousness Beyond Life: The Science of the Near-Death Experience. HarperCollins, New York.

#consciousness#cognitive science#near death experiences#nde#terminal lucidity#terminal illness#cognitive neuroscience#paradoxical lucidity#hemispherectomy#corpus collosotomy#psychadelic#psychonaut#psychonauts#psilocybin#lsd#ketamine#materialism and its discontents#neurology#neuropsychology#philosophy of mind#brain#quantum physics#consciousness series

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

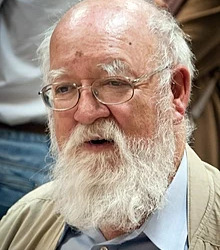

Daniel Dennett (1942 - 2024)

Many of us today woke up to a world that felt a little less vibrant, a little less intellectually stimulating. Daniel Dennett, a philosopher who revolutionized our understanding of the mind, science, and consciousness, passed away yesterday.

Daniel Dennett, image taken from Wikipedia

For me, Dennett was a guiding light in his study field. His work, particularly his early books “Content and…

View On WordPress

#academia#Artificial Intelligence#biology#cognitive science#computationalism#consciousness#cultural commentator#Daniel Dennett#Darwin#free will#mental processes#Mind#multiple drafts model#naturalistic approach#nature of reality#philosopher#Philosophy#philosophy of mind#philosophy of science#Raffaello Palandri#science#wisdom

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“A high degree of intellect tends to make a man unsocial.”

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation.

#Pessimism#Will and Representation#Metaphysics#Ethics#Existentialism#Philosophy of Mind#Kantianism#Aesthetics#Solipsism#Nihilism#Idealism#Compassion#Individualism#World as Illusion#Transcendental Idealism#Suffering#The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason#Eastern Philosophy Influence#Art and Beauty#Critique of Hegel's Philosophy#today on tumblr#quoteoftheday

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ramanuja (vs Hume et. al.): "...the essential character of consciousness or knowledge is that by its very existence it renders things capable of becoming objects...of thought and speech. This consciousness...is a particular attribute belonging to a conscious self and related to an object; as such it is known to every one on the testimony of his own self--as appears from ordinary judgments such as 'I know the jar,' 'I understand this matter,' 'I am conscious of (the presence of) this piece of cloth.'

...we clearly see that this agent (the subject of consciousness) is permanent (constant), while its attribute, i.e., consciousness, not differing herein from joy, grief, and the like, rises, persists for some time, and then comes to an end. The permanency of the conscious subject is proved by the fact of recognition, 'This very same thing was formerly apprehended by me.'

...

...But the fact is that the state of consciousness presents itself as something apart, constituting a distinguishing attribute of the I, just as the stick is an attribute of Devadatta who carries it. The judgment 'I am conscious' reveals an 'I' disginguished by consciousness; and to declare that it refers only to a state of consciousness--which is a mere attribute--is no better than to say that the judgment 'Devadatta carries a stick' is about the stick only..."

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

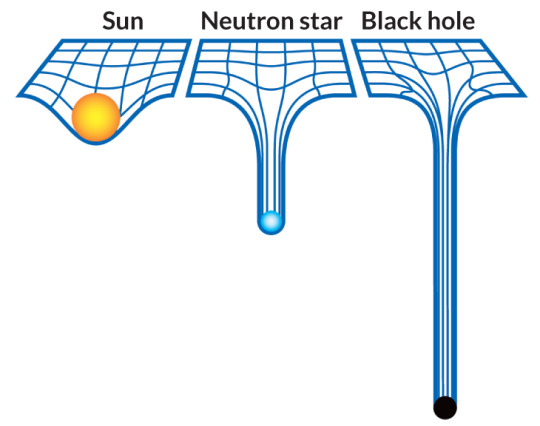

Everything across history has happened with the same intensity that real life feels to you right now today. Its easy to forget that the past is comprised of people exactly like ourselves. That each and every person in the world shares the universal experience of experience. In the philosophy of the mind theres a view of consciousness referred to as panpsychism. Essentially, this is the idea that consciousness is a fundamental feature of reality. If this is the case, we can imagine a field of consciousness not entirely unlike a field of gravity.

You've probably seen a diagram like this before explaining the strength of gravity with relation to the masses of objects. Within the view of panpsychism beings of higher levels of consciousness are analogous to objects of larger mass.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mind Starts at Conception

Every abortion risks the creation of a bodily traumatized abortion survivor. The body remembers what our conscious mind does not record. It seems ridiculous to suggest to a survivor that what happened did not happen to them. Why?

Even if the body isn't harmed physically by an abortion, the stress still registers in the body-mind. You CAN stress out an embryo, literally. But then aren't epigenetics (inherited stress) part of a mind? I think so. That doesn't mean I think every cell with genes is a mind.

Gametes cease to exist upon fusion. They don't go through a stage of development; they become an entirely new thing. When their substances change there is a break in continuity between the gametes and the human minds to whom the gametes contribute genes and material. Meanwhile, a human organism doesn't cease to be at any point between fertilization and death, substantially or metaphysically.

A gamete not only ceases to be in physical substance at fertilization, (sperm in particular more or less dissolve,) but also metaphysically, in identity. For a lone gamete, the possibilities for which humans would inherit its DNA and material is an infinite set. It is unspecific. The zygote, on the other hand, is limited to about 4 potentialities. They are a specific, individual set. After the primitive streak, that set converges. Ergo, the set of a gamete is divergent, the set of a zygote is convergent.

"Markov blankets" is a theory related to the Free Energy Principle of Karl Friston that the mind is statistically boundaried to its most complete set. In other words, we can make a reasonable guess that a mind is definitely in some locations, not others.

I think we have good reason to suspect that the boundary lies somewhere between where the subsets of convergent series end (all the proprietary cells of the new person) and the divergent series begin (gametes). (We treat gamete cells more as 'your property' than as 'you'.) You could fairly speculate that the donor gamete MIGHT be in an individual's markov blanket. But if it is, it appears to be a statistical outlier. (One of these things is not like the other = outlier.) We're not unreasonable in saying gametes fall outside the line of best fit.

This shift from divergent series to convergent series seems like an extremely reasonable place to draw the metaphysical boundary of "I end and you begin". Like drawing the fault lines where two geological plates shift in different directions, but mereological! Of course, I could be wrong. If you can show me that the sets I am including pre-brain birth are meaningfully metaphysically different than the sets post-brain birth, then I'll reconsider my mereological stance. Perhaps the blanket is smaller than I think. But perhaps not.

When I ask myself, "which subsets of markov blankets act within this surprise-minimizing system" (a bare-bones definition of an individual mind,) I cannot say the donor gamete is clustered with the whole. On its own the gamete minimizes surprise in singularity, not individuality—individual, here referring to indivisible.

When I cut my hair, I don't look down and say "that's me on the floor". That hair isn't contributing to my system's perceptions in order to minimize surprise. I also wouldn't say that about my eggs if I froze them. They're divisible! But if you touch the living skin connected to my surprise-minimizing system, I'd say, "stop touching me". Not divisible. My zygote? Not divisible! Its perceptions are continuous with my system. If you tamper with a gamete, infinite individuals could inherit the effects. But once the tampered gamete fuses into a zygote, the effects are limited to an individual set of about 4 specific people. (4 because that's about how many times an embryo can bud a twin.)

An individual set of people in one blanket? You know what's cool about this?? This means up to about four people can exist as an individual set simultaneously in a single spatial and temporal location!! That's fucking neat. Yes, while these people's specific markov blankets will eventually diverge, they originate with convergent overlap. In this way, identical siblings can be said to LITERALLY share a mind, to some extent! Their markov blankets overlap!!

We cannot draw the boundary line for personhood based on substance, location, time, or ability alone. I'm drawing upon bayesian logic to make metaphysical inferences. Ergo, the pertinent question to me is not "is this a mind". Yes, I think my surprise-minimizing system, my sophisticated ability to think in predictions, is continuous with and contingent upon the rudimentary perceptive ability of my zygote.

The question is rather, why should you care? I think you should care about minds that are not like yours, but if all keeps going well, will be. I think you should care about minds that would be like yours, but all did not go well, so they are not. I think you should have unconditional regard for human minds in all forms.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not reblogging it because I don't want to spread it, but just read a science fiction author (treated as an expert) saying the reason that LLMs aren't artificial intelligence is because they learn by a system of training connections to weight some results more than others and that's not how we learn.

Except it is. It really is.

Look, his explanation was a little garbled (I don't know if he was confused or trying to dumb it down for his readers), but what he's talking about is the structure of a neural net computer. They mirror and are inspired by neurons in our brains.

In cognitive science we call this the connectivist model.

Rather than the classic Computational Theory of Mind picture of an idealised Universal Turing Machine* (where we imagine the mind as a computer that has an input, a library of answers, and a processor that matches the input to something in the library of answers to produce an appropriate output) neural nets don't have a library of stock answers. Instead they have a vast net of connections that can be set to either on or off. This is equivalent to neurons that either fire (emit an electrical impulse) in response to a stimulus, or don't.

The connections start out randomised and produce results that are nonsense (like a baby burbling) but you then 'teach' the computer by telling it when it produces something more like the right answer. Like when parents get excited that the baby said something closer to 'Dada'. This amounts to telling it to keep the connection node in its current on or off position. If you tell it it got it wrong, it switches the connection to the other position.

This can be done by a human 'teacher' manually looking at the result and saying... yeah, that sort of looks like a cat (or whatever), or an algorithm. You may have played with a program that was learning to create cats and laughed at the terrible results. If you told it 'no, that is not a cat', you were being the teacher. You made it very slightly less likely to produce an eldritch abomination next time.

This is exactly how our brains work when we learn. Computer scientists were inspired by the brain because they weren't gonna get the results they wanted using classic Turing Machines. And it pisses me off that I'm seeing a lot of science fiction authors declaim that this isn't 'learning'.

It's true that it's not *artificial intelligence* because this method of learning is not all our brains are doing that differentiates us from LLMs.

First up, the processing power of a brain is ENORMOUS. Nothing like it exists in modern computing. Quantum computers are looking interesting, though.

Secondly, LLMs are trained to do just One Thing. Create something that looks like art. Produce something that fits the pattern of a story, or advertising copy. You can't ask an art LLM to write a story that goes with the picture it draws. By contrast, our brains have different modules devoted to processing different parts of the world. We know this because of how people's behaviour changes when different parts of the brain get damaged.

(Fun fact: we also know from how people can manage to function perfectly normally with certain kinds of brain damage or genetic abnormalities that the brain can often repurpose these dedicated areas to do different things. This reflects the flexibility of being founded on a connectivist structure. Why this happens with certain kinds of brain damage and not others is a whole other complex story.)

But it's not just that the brain is made up of a bunch of independent neural nets taped together. They overlap in some ways, and brains have evolved in really cool ways to maximise what they can do with what they have, reusing portions of the nerual net to save space. The same neuron, or set of neurons, may be used in multiple different processes. Which enables us to do stuff like not just say recognisable words in response to certain prompts, but associate them with a complex array of images (or other sensory stimulous) and behaviours. 'Dada' doesn't just get delivered as the right response in a bunch of sentences about dads, or even your specific dad, it's associated with what your dad looks like, with a bunch of events (memories) you experiences with him, maybe with some punishments for being naughty and some rewards for being nice. But these aren't just yes/no rewards that reset or affirmed your neural connections. These memories are connected to complex behaviours you had, maybe pain receptors firing, maybe the taste of vanilla ice cream. The number of connections that use and reuse the neural settings for a single word are so huge I couldn't begin to create a complete description.

What's more there may be a lot about being embodied that is required in order to achieve consciousness. It's not just producing the right response to the right stimuli, but going out into the world and giving stimulus to other things, and receiving their response as further input in return.

You'll have heard me mention that Donald Davidson argues that self-consciousness requires successful interactions with other minded beings about a shared external world about which you both hold largely correct beliefs. I think that's broadly right.

MEANING is created intersubjectively by agreeing and disagreeing about shared/publicly available stimuli.

I think this is the source of the confusion.

When most people think of learning, they envision a parent and child or a child and teacher - embodied, complex creatures. And that the child doesn't merely learn to make the right responses, but to 'understand' the meaning of what they say.

The connectivist model BY ITSELF cannot account for everything involved in learning that involves meaning and understanding. But that doesn't mean it's not what's going on in a child's brain as they learn. It's just that the child is fantastically more complicated. They're composed of overlapping neural nets and genetic algorithms and evolutionary shortcuts. AND WE HAVE THINGS IN COMPUTER SCIENCE THAT MIRROR A LOT OF THIS. INSPIRED BY THIS. Genetic algorithms and feedback loops and 'evolutionary' learning.

What we don't have right now is the processing power, the complexity of overlapping neural nets, the memory space, and maybe embodiment.

If you say 'artificial intelligence does not exist', that's technically true right now. The output from these machines isn't meaningful right now. They are LLMs, not AIs. Calling it AI is a marketing tool. It's machine learning. But we're working on it.

And the *learning* portion... we have the mechanics of it. Neural nets aren't just producing impressive-looking results, they are based on how our brains learn.

So it annoys me when people throw out that it's not how learning works. It's exactly how learning works. It's just not the complete picture required for UNDERSTANDING, MEANING, and SELF-REFLECTION.

It doesn't pass the requirements for MINDEDNESS. But that's not the same as matching the mechanical ways in which we learn.

*Do not get distracted by the Turing Test, if you've heard if it. The Turing Test was a thought experiment, but it's by no means the most interesting thing Turing did. No one treats the Turing Test seriously in cognitive science anymore. Arguably, Eliza the computer psychiatrist could fool at least some humans in the 1960s. Behaviourism as a philosophy of mind (that behaving the right way is all there is to being minded/having meaning) is a very out-dated theory.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Responses to the hard problem of consciousness: a flowchart

I have created a chart that shows the responses that have been given to the hard problem of consciousness, which has fascinated me for quite a while now.

The hard problem of consciousness is the philosophical debate over how it is possible that consciousness, as we experience it, exists (rather than not exist). At least, that is how it typically seems to be understood. I would add, as Raamy Majeed and Wolfgang Fasching have done, that, besides being about explaining why consciousness exists at all, the hard problem of consciousness can additionally be understood as being about addressing the (possibly even more mysterious) question of why consciousness takes those forms that it does (or appears to do). This will be discussed in a brief essay (in Dutch) soon to appear on this blog.

The chart is my attempt at mapping this debate as clearly as possible. When one learns about the responses to the hard problem, it is easy to get lost in a maze of exotic sounding -isms that are not always defined in a very understandable way. My flowchart can hopefully clear up the positions. All errors in the chart are my own.

Click here to view the chart in full-size, so that you can read the text.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theories of The Philosophy of Other and The Philosophy of Self

The philosophy of other refers to the study of how we relate to other individuals and groups within society, and how we understand and define concepts such as identity, difference, and otherness. It involves examining questions such as: What is the relationship between self and other? How do we define and construct the boundaries between self and other? How do we understand and respond to difference and diversity? What ethical and political implications arise from our relationships with others? The philosophy of other draws on a range of philosophical traditions, including ethics, social and political philosophy, phenomenology, and existentialism.

The philosophy of the "other" is a broad and complex field that can cover many areas, including ethics, political philosophy, and social philosophy. Some theories in the philosophy of the "other" include:

Recognition theory: This theory focuses on the idea that human beings are social creatures who require recognition and respect from others to maintain a sense of self. This theory is often associated with the work of philosopher Axel Honneth.

Postcolonial theory: This theory examines the ways in which colonialism and imperialism have shaped our understanding of the "other." Postcolonial theorists often explore the ways in which dominant cultures have imposed their values, beliefs, and practices on colonized peoples.

Critical race theory: Critical race theory examines the ways in which race and racism impact our social and political systems. It aims to challenge and dismantle systemic racism and discrimination. This theory is often associated with the work of scholars such as Kimberlé Crenshaw and Richard Delgado.

Phenomenology: Phenomenology is a philosophical approach that focuses on subjective experiences of the world. This approach has been used to explore questions about the nature of selfhood and the ways in which we perceive and understand the "other."

Existentialism: Existentialism is a philosophical approach that emphasizes individual freedom and choice. This approach has been used to explore questions about the nature of the self and our relationships with others.

Psychoanalytic theory: Psychoanalytic theory examines the unconscious mind and the ways in which our unconscious desires and impulses impact our relationships with others. This theory is often associated with the work of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan.

Critical theory: Critical theory is a broad field that examines the ways in which power and domination operate in society. Critical theorists often explore the ways in which dominant groups oppress marginalized groups and the ways in which social change can be achieved.

Social Contract Theory: This theory focuses on the idea that people give up some of their individual rights in order to live together in a society governed by certain rules and laws.

Cultural Relativism: This theory suggests that different cultures have their own unique values and ways of looking at the world, and that there is no universal standard for what is right or wrong.

Feminist Theory: This theory focuses on the ways in which gender affects social relations and power dynamics, and aims to challenge and change patriarchal norms and structures.

Queer Theory: This theory explores the ways in which sexual orientation and gender identity intersect with power dynamics and social norms, and aims to challenge and subvert heteronormative and cisnormative structures.

Disability Studies: This theory examines the ways in which disability intersects with social and political power dynamics, and aims to challenge and change ableist norms and structures.

Environmental Philosophy: This theory explores the ethical and political implications of our relationship with the natural world, and aims to challenge and change anthropocentric and exploitative attitudes towards the environment.

The philosophy of self is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the self or the individual. It concerns questions about the nature of personal identity, the mind-body problem, consciousness, and the self's relationship to society and the world. Some of the central issues in the philosophy of self include: What is the self? What makes us the same person over time? How do we know that we have a self? Is the self a real entity or just an illusion? What is the relationship between the self and consciousness? How does the self relate to the world and others around us? These questions have been approached by various philosophical traditions, including phenomenology, existentialism, analytic philosophy, and Eastern philosophy.

The philosophy of self, or selfhood, is a complex and multifaceted field that has been explored by many philosophers throughout history. Some of the main theories and approaches within this field include:

Cartesian dualism: This theory, named after philosopher René Descartes, posits that the self or soul is separate from the body and that the two interact through the pineal gland in the brain.

Bundle theory: This theory, developed by philosopher David Hume, suggests that the self is simply a bundle or collection of experiences, sensations, and perceptions.

Narrative theory: This theory, championed by philosopher Paul Ricoeur, proposes that the self is constructed through the stories we tell ourselves and others about our lives.

Self-organizational theory: This theory, put forward by philosopher Francisco Varela, suggests that the self is a complex system that emerges from the interactions between the brain, body, and environment.

Phenomenological theory: This theory, developed by philosopher Edmund Husserl, emphasizes the first-person experience of the self and suggests that the self is constituted by conscious experience.

Social constructivism: This theory, which has been developed by a number of philosophers including Judith Butler and Michel Foucault, proposes that the self is a socially constructed identity that is shaped by cultural norms and discourses.

Buddhist philosophy: Within Buddhist philosophy, there are a number of different theories about the self, including the idea that the self is an illusion and that it does not exist independently of other phenomena.

Existentialism: This philosophical movement, which includes thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger, emphasizes the importance of individual choice and freedom in the formation of the self.

Minimalism: This theory holds that there is no self at all, and that the idea of a unified, enduring self is an illusion.

Eastern philosophy: Many Eastern philosophical traditions, such as Buddhism and Taoism, reject the notion of a fixed and unchanging self, and instead view the self as impermanent and interdependent with the world around it.

#philosophy#epistemology#psychology#social philosophy#knowledge#education#learning#chatgpt#self#other#mind#power relations#theories#agency#multiculturism#politics#society#identity#philosophy of mind

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Čovek osudjuje ono što ne razume, definišući to kao "pogrešno". Ako tu istu stvar drugi čovek razume i definiše je kao "razumnu, prihvatljivu", koji je čovek u pravu?

Kako onda doneti sud o bilo čemu? Ko je u pravu? Ko deli propusnice?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

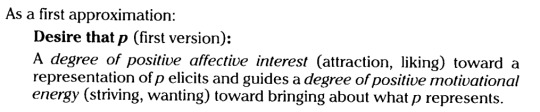

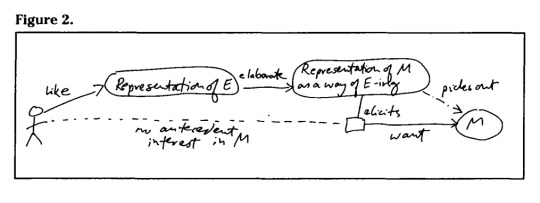

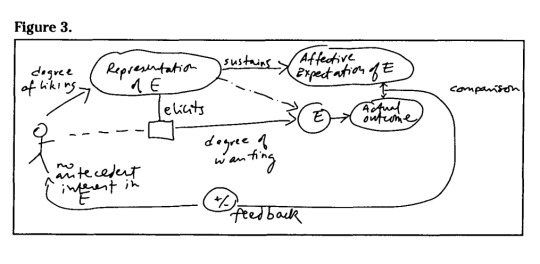

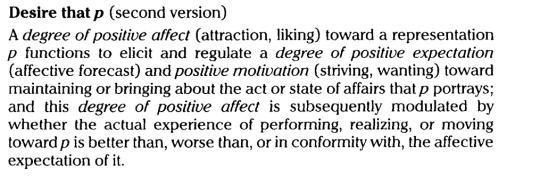

Figures from Peter Railton's "That Obscure Object, Desire"

#philosophy#philosophy of action#moral psychology#desire#peter railton#that obscure object desire#it might be sort of incoherent presented this way 🤷🏼♀️ but this was the most visually engaging philosophy paper i read in grad school lol#desire theory#grad school#practical reasoning#marketing#philosophy of mind#ethics#normativity#my library

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Does Quantum Physics Imply About Consciousness?

In recent years much has been written about whether quantum mechanics (QM) does or does not imply that consciousness is fundamental to the cosmos. This is a problem that physicists have hotly debated since the earliest days of QM a century ago. It is extremely controversial; highly educated and famous physicists can't even agree on how to define the problem.

I have a degree in physics and did some graduate level work in QM before switching to computer science; my Ph.D. addressed topics in cognitive science. So I'm going to give it a go to present an accessible and non-mathematical summary of the problem, hewing to as neutral a POV as I can manage. Due to the complexity of this subject I'm going to present it in three parts, with this being Part 1.

What is Quantum Mechanics?

First, a little background on QM. In science there are different types of theories. Some explain how phenomena work without predicting outcomes (e.g., Darwin's Theory of Evolution). Some predict outcomes without explaining how they work (e.g., Newton's Law of Gravity.)

QM is a purely predictive theory. It uses something called the wave function to predict the behavior of elementary particles such as electrons, photons, and so forth. The wave equation expresses the probabilities of various outcomes, such as the likelihood that a photon will be recorded by a detection instrument. Before the physicist takes a measurement the wave function expresses what could happen; once the measurement is taken, it's no longer a question of probabilities because the event has happened (or not). The instrument recorded it. In QM this is called wave function collapse.

The Measurement Problem

When a wave function collapses, what does that mean in real terms? What does it imply about our familiar macroscopic world, and why do people keep saying it holds important implications for consciousness?

In QM this is called the Measurement Problem, first introduced in 1927 by physicist Werner Heisenberg as part of his famous Uncertainty Principle, and further developed by mathematician John Von Neumann in 1932. Heisenberg didn't attempt to explain what wave function collapse means in real terms; since QM is purely predictive, we're still not entirely sure what implications it may hold for the world we are familiar with. But one thing is certain: the predictions that QM makes are astonishingly accurate.

We just don't understand why they are so accurate. QM is undoubtedly telling us "something extremely important" about the structure of reality, we just don't know what that "something" is.

Interpretations of QM

But that hasn't stopped physicists from trying. There have been numerous attempts to interpret what implications QM might hold for the cosmos, or whether the wave function collapses at all. Some of these involve consciousness in some way; others do not.

Wave function collapse is required in these interpretations of QM:

The Copenhagen Interpretation (most commonly taught in physics programs)

Collective Collapse interpretations

The Transactional Interpretation

The Von Neumann-Wigner Interpretation

It is not required in these interpretations:

The Consistent Histories interpretation

The Bohm Interpretation

The Many Worlds Interpretation

Quantum Superdeterminism

The Ensemble Interpretation

The Relational Interpretation

This is not meant to be an exhaustive list, there are a boatload of other interpretations (e.g. Quantum Bayesianism). None of them should be taken as definitive since most of them are not falsifiable except via internal contradiction.

Big names in physics have lined up behind several of these (Steven Hawking was an advocate of the Many Worlds Interpretation, for instance) but that shouldn't be taken as anything more than a matter of personal philosophical preference. Ditto with statements of the form "most physicists agree with interpretation X" which has the same truth status as "most physicists prefer the color blue." These interpretations are philosophical in nature, and the debates will never end. As physicist M. David Mermin once observed: "New interpretations appear every year. None ever disappear."

What About Consciousness?

I began this post by noting that QM has become a major battlefield for discussions of the nature of consciousness (I'll have more to say about this in Part 2.) But linkages between QM and consciousness are certainly not new. In fact they have been raging since the wave function was introduced. Erwin Schrodinger said -

And Werner Heisenberg said -

In Part 2 I will look deeper at the connections between QM and consciousness with a review of philosopher Thomas Nagel's 2012 book Mind and Cosmos. In Part 3 I will take a look at how recent research into Near-Death Experiences and Terminal Lucidity hold unexpected implications for understanding consciousness.

(Image source: @linusquotes)

#quantum physics#consciousness#copenhagen interpretation#superdeterminism#many worlds#philosophy#physics#philosophy of mind#brain#consciousness series

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

sharks do dream ! they share a common dreaming ancestor w us and have been recorded as dreaming also iirc

(Anon is talking about my header which currently says “Sharks Sleep, But Might Not Dream”)

Asking whether or not an animal “dreams” is a little like asking if it experiences “emotions.” Certainly, it’s possible to observe brain activity and outward behavior that suggests answers to these questions, but we will never know it’s like to be another animal. In slightly more technical language, we will never have definitive empirical evidence of an animal’s internal phenomenology.

When you say sharks have “been recorded” dreaming… what does that mean? It’s not like a scientist climbed inside a shark’s head and recorded everything she saw.

Could you be referring to news articles that claim sharks “turn off” half their brains? Then you would be absolutely correct that it has been recorded—but I’m skeptical about your implication that it necessarily means that sharks dream. Lots of animals have brain activity that looks like human brain activity even while they do things radically different from us. So, I’m always weary of people who say with certainty that an animal has a type of experience based on physiological and neurological observations that are similar to humans having that experience. (And in any case, humans don’t “turn off” half their brains when we sleep.)

There’s actually a lot of evidence that suggests animals have thoughts fundamentally unlike ours. (You could check out my pinned post about octopus minds and distributed consciousness (shameless self plug)).

Anon, you also say that sharks have ancestors that sleep. Again, I’m not totally sure what you’re referring to. This is the closest thing I could find: https://www.earth.com/news/sharks-can-literally-sleep-with-their-eyes-open/

“This rationale is particularly salient following the recent discovery of two sleep states in teleosts and in at least two species of lizard that in some respects resemble mammalian and avian non-rapid eye movement and REM sleep,” noted the study authors.

“The existence of two sleep states in birds and mammals suggests that each state performs a different, but perhaps complementary, function. Any homology between the multiple sleep states observed in ectothermic vertebrates to that of endothermic vertebrates is unclear.”

According to the researchers, their results show that – like with many vertebrates – sleep in sharks is associated with reduced metabolic rate.

This is a much milder claim than what you’re saying. It doesn’t actually assert that any animals have dreams—just that they have REM and NREM sleep. For those who don’t know, “Rapid Eye Movement” sleep is the stage at which humans have most dreams. But other animals having REM doesn’t prove that they dream, too. (article also doesn’t seem to confirm that these particular lizards and birds are the ancestors of sharks? But I honestly don’t know! Hopefully I’ll have a chance to research shark ancestors soon!)

I couldn’t find any evidence that sharks have REM sleep. This article https://xploreourplanet.com/sea/do-great-white-sharks-sleep says there’s no evidence that they do (but the article’s date doesn’t include a year, take it with a grain of salt). All in all, I just think there’s very little evidence that SUGGESTS sharks dream or don’t dream. And there will never be scientific evidence that PROVES they have dreams. Short of an omniscient messenger angel telling us all about shark dream-states, we just have no way of knowing for sure what it is like to be in a brain that isn’t human.

If anything, the first clause of my header should be more controversial. Sleep is actually a somewhat “fuzzy” term. Because it’s difficult to define, it’s difficult to say whether or not a given animal sleeps. Plenty of articles will claim absolute proof that sharks do or don’t sleep, and then imply some definition of “sleep” that they never defend. And usually, the implicit definitions of “sleep” outright contradict each other. I’ve found many pairs of articles where one author uses evidence to demonstrate that sharks sleep, and then another author uses the exact same evidence to demonstrate that sharks don’t sleep.

Now, most of those articles are for preservation charities. I think the big split really comes down to whether the author thinks saying sharks sleep will make them sound cool. Like, fundraisers that claim they DO sleep are probably trying to suggest these animals are like us in some fundamental ways. Meanwhile, I usually get the vibe that charities saying that sharks don't sleep are trying to make them sound like these spectacular, otherworldly creatures (which, to be fair, they ARE).

Most peer-reviewed scientific research is much more cautious. The article "Behavioural sleep in two species of buccal pumping sharks (Heterodontus portusjacksoni and Cephaloscyllium isabellum)" couches its conclusions in VERY hesitant language. It frequently says things like "our results suggest" instead of "we have proven". However, it ultimately does conclude that there is direct evidence that at least two species of sharks sleep.

So, by some definitions, I am absolutely correct that “sharks sleep.” By other definitions, I’m probably wrong—but we’re still gaining new information about shark behaviors all the time! The truth is we have very little data about how these animals behave! They’re difficult to study, especially in their natural habitat (because, y’know, it’s underwater) so there just isn’t enough data to solve most problems yet.

This study sums up the stakes pretty beautifully:

There is an absence of knowledge on sleep in cartilaginous fishes. Sharks and rays are amongst the earliest vertebrates, and may hold clues to the evolutionary history of sleep and sleep states found in more derived animals, such as mammals and birds. (Evidence for Sleep in Sharks and Rays: Behavioural, Physiological, and Evolutionary Considerations)

Sharks are so old that they predate the way we sleep. Does that mean they predate sleep in general? Are they some of the first sleepers? Do they sleep at all? These questions are still very controversial. So, I don’t think you should trust an article that claims to definitively prove that they dream. Anyone who believes they can answer that question is really getting ahead of themselves.

My header title is a little bit unspecific. A clearer title would read “Some Scientists Claim That Some Sharks Sleep…” but I wanted to be more poetic. That said, I don’t think my assertion that “Sharks Sleep” is technically wrong. It’s incomplete information… but I think if you’re looking for complete information in a six word title, you’re in the wrong place. What do you guys think? Is “Sharks Sleep” fair game, or do I need a new title?

#if enough of you guys think my title is just disinformation I’ll delete it#but tbh I don’t think the title is a big deal?#I try to keep my original posts factual (or obviously satirical)#but like....#does the blog description also need to be thorough and maximally clear?#asks#sharks#original post#biology#marine biology#philosophy of mind

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Men believe they are free for the reason that they are aware of their actions and ignorant of the causes by which they are determined.

//

Men think themselves free, because they are conscious of their volitions and their appetite, and do not think, even in their dreams, of the causes by which they are disposed to wanting and willing, because they are ignorant of [those causes].

Baruch Spinoza, Epistemology and Philosophy of Mind

#Baruch Spinoza#Spinoza#quote#freedom#causes#human mind#human minds#thought#understanding#cognition#causal#intention#free will#free#determinism#Epistemology and Philosophy of Mind#philosophy of mind

6 notes

·

View notes