#epistemology

Text

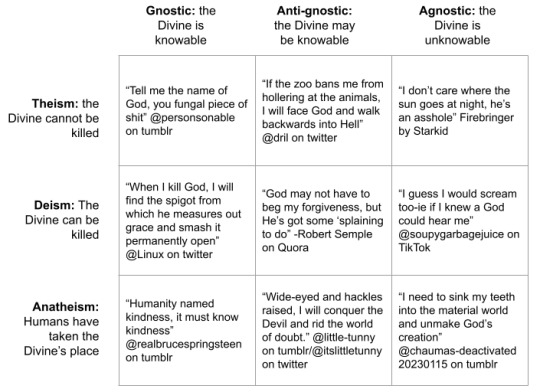

Religious alignment chart w/ internet quotes

I am not a theologian, hope this helps

Links and alt text under the cut:

Gnostic Theism: “Tell me the name of God, you fungal piece of shit” @personsonable on tumblr [link]

Anti-gnostic Theism: “If the zoo bans me from hollering at the animals, I will face God and walk backwards into Hell” @dril on twitter [link]

Agnostic Theism: “I don’t care where the sun goes at night, he’s an asshole” Firebringer by Starkid [link]

Gnostic Deism: “When I kill God, I will find the spigot from which he measures out grace and smash it permanently open” @Linux on twitter [link]

Anti-gnostic Deism: “God may not have to beg my forgiveness, but He’s got some ‘splaining to do” -Robert Semple on Quora [link]

Agnostic Deism: “I guess I would scream too-ie if I knew a God could hear me” @soupygarbagejuice on TikTok [link]

Gnostic Anatheism: “Humanity named kindness, it must know kindness” @realbrucespringsteen on tumblr [link]

Anti-gnostic Anatheism: “Wide-eyed and hackles raised, I will conquer the Devil and rid the world of doubt.” @little-tunny on tumblr/@itslittletunny on twitter [link]

Agnostic Anatheism: “I need to sink my teeth into the material world and unmake God’s creation” @chaumas-deactivated20230115 on tumblr [link]

#theology#epistemology#religion#philosophy#dril tweets#in case you couldnt tell#i am doing really well right now

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

The fact that "politically correct", "identity politics", "intersectionality", were all birthed and come from Black feminism, had very specific meanings that have been wholly flouted or extraordinarily distorted is...interesting.

"This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough." from the Combahee River Collective

"And a man cannot be politically correct and a chauvinist too" from On The Issue of Roles by Toni Cade Bambara

Intersectionality is not primarily about identity, it's about how structures make certain identities the consequence of and the vehicle for vulnerability.

Kimberlé Crenshaw

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

😎

Via

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Conspiratorialism and the epistemological crisis

I'm on tour with my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me next weekend (Mar 30/31) in ANAHEIM at WONDERCON, then in Boston with Randall "XKCD" Munroe! (Apr 11), then Providence (Apr 12), and beyond!

Last year, Ed Pierson was supposed to fly from Seattle to New Jersey on Alaska Airlines. He boarded his flight, but then he had an urgent discussion with the flight attendant, explaining that as a former senior Boeing engineer, he'd specifically requested that flight because the aircraft wasn't a 737 Max:

https://www.cnn.com/travel/boeing-737-max-passenger-boycott/index.html

But for operational reasons, Alaska had switched out the equipment on the flight and there he was on a 737 Max, about to travel cross-continent, and he didn't feel safe doing so. He demanded to be let off the flight. His bags were offloaded and he walked back up the jetbridge after telling the spooked flight attendant, "I can’t go into detail right now, but I wasn’t planning on flying the Max, and I want to get off the plane."

Boeing, of course, is a flying disaster that was years in the making. Its planes have been falling out of the sky since 2019. Floods of whistleblowers have come forward to say its aircraft are unsafe. Pierson's not the only Boeing employee to state – both on and off the record – that he wouldn't fly on a specific model of Boeing aircraft, or, in some cases any recent Boeing aircraft:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/22/anything-that-cant-go-on-forever/#will-eventually-stop

And yet, for years, Boeing's regulators have allowed the company to keep turning out planes that keep turning out lemons. This is a pretty frightening situation, to say the least. I'm not an aerospace engineer, I'm not an aircraft safety inspector, but every time I book a flight, I have to make a decision about whether to trust Boeing's assurances that I can safely board one of its planes without dying.

In an ideal world, I wouldn't even have to think about this. I'd be able to trust that publicly accountable regulators were on the job, making sure that airplanes were airworthy. "Caveat emptor" is no way to run a civilian aviation system.

But even though I don't have the specialized expertise needed to assess the airworthiness of Boeing planes, I do have the much more general expertise needed to assess the trustworthiness of Boeing's regulator. The FAA has spent years deferring to Boeing, allowing it to self-certify that its aircraft were safe. Even when these assurances led to the death of hundreds of people, the FAA continued to allow Boeing to mark its own homework:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8oCilY4szc

What's more, the FAA boss who presided over those hundreds of deaths was an ex-Boeing lobbyist, whom Trump subsequently appointed to run Boeing's oversight. He's not the only ex-insider who ended up a regulator, and there's plenty of ex-regulators now on Boeing's payroll:

https://therevolvingdoorproject.org/boeing-debacle-shows-need-to-investigate-trump-era-corruption/

You don't have to be an aviation expert to understand that companies have conflicts of interest when it comes to certifying their own products. "Market forces" aren't going to keep Boeing from shipping defective products, because the company's top brass are more worried about cashing out with this quarter's massive stock buybacks than they are about their successors' ability to manage the PR storm or Congressional hearings after their greed kills hundreds and hundreds of people.

You also don't have to be an aviation expert to understand that these conflicts persist even when a Boeing insider leaves the company to work for its regulators, or vice-versa. A regulator who anticipates a giant signing bonus from Boeing after their term in office, or a an ex-Boeing exec who holds millions in Boeing stock has an irreconcilable conflict of interest that will make it very hard – perhaps impossible – for them to hold the company to account when it trades safety for profit.

It's not just Boeing customers who feel justifiably anxious about trusting a system with such obvious conflicts of interest: Boeing's own executives, lobbyists and lawyers also refuse to participate in similarly flawed systems of oversight and conflict resolution. If Boeing was sued by its shareholders and the judge was also a pissed off Boeing shareholder, they would demand a recusal. If Boeing was looking for outside counsel to represent it in a liability suit brought by the family of one of its murder victims, they wouldn't hire the firm that was suing them – not even if that firm promised to be fair. If a Boeing executive's spouse sued for divorce, that exec wouldn't use the same lawyer as their soon-to-be-ex.

Sure, it takes specialized knowledge and training to be a lawyer, a judge, or an aircraft safety inspector. But anyone can look at the system those experts work in and spot its glaring defects. In other words, while acquiring expertise is hard, it's much easier to spot weaknesses in the process by which that expertise affects the world around us.

And therein lies the problem: aviation isn't the only technically complex, potentially lethal, and utterly, obviously untrustworthy system we all have to navigate. How about the building safety codes that governed the structure you're in right now? Plenty of people have blithely assumed that structural engineers carefully designed those standards, and that these standards were diligently upheld, only to discover in tragic, ghastly ways that this was wrong:

https://www.bbc.com/news/64568826

There are dozens – hundreds! – of life-or-death, highly technical questions you have to resolve every day just to survive. Should you trust the antilock braking firmware in your car? How about the food hygiene rules in the factories that produced the food in your shopping cart? Or the kitchen that made the pizza that was just delivered? Is your kid's school teaching them well, or will they grow up to be ignoramuses and thus economic roadkill?

Hell, even if I never get into another Boeing aircraft, I live in the approach path for Burbank airport, where Southwest lands 50+ Boeing flights every day. How can I be sure that the next Boeing 737 Max that falls out of the sky won't land on my roof?

This is the epistemological crisis we're living through today. Epistemology is the process by which we know things. The whole point of a transparent, democratically accountable process for expert technical deliberation is to resolve the epistemological challenge of making good choices about all of these life-or-death questions. Even the smartest person among us can't learn to evaluate all those questions, but we can all look at the process by which these questions are answered and draw conclusions about its soundness.

Is the process public? Are the people in charge of it forthright? Do they have conflicts of interest, and, if so, do they sit out any decision that gives even the appearance of impropriety? If new evidence comes to light – like, say, a horrific disaster – is there a way to re-open the process and change the rules?

The actual technical details might be a black box for us, opaque and indecipherable. But the box itself can be easily observed: is it made of sturdy material? Does it have sharp corners and clean lines? Or is it flimsy, irregular and torn? We don't have to know anything about the box's contents to conclude that we don't trust the box.

For example: we may not be experts in chemical engineering or water safety, but we can tell when a regulator is on the ball on these issues. Back in 2019, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection sought comment on its water safety regs. Dow Chemical – the largest corporation in the state's largest industry – filed comments arguing that WV should have lower standards for chemical contamination in its drinking water.

Now, I'm perfectly prepared to believe that there are safe levels of chemical runoff in the water supply. There's a lot of water in the water supply, after all, and "the dose makes the poison." What's more, I use the products whose manufacture results in that chemical waste. I want them to be made safely, but I do want them to be made – for one thing, the next time I have surgery, I want the anesthesiologist to start an IV with fresh, sterile plastic tubing.

And I'm not a chemist, let alone a water chemist. Neither am I a toxicologist. There are aspects of this debate I am totally unqualified to assess. Nevertheless, I think the WV process was a bad one, and here's why:

https://www.wvma.com/press/wvma-news/4244-wvma-statement-on-human-health-criteria-development

That's Dow's comment to the regulator (as proffered by its mouthpiece, the WV Manufacturers' Association, which it dominates). In that comment, Dow argues that West Virginians safely can absorb more poison than other Americans, because the people of West Virginia are fatter than other Americans, and so they have more tissue and thus a better ratio of poison to person than the typical American. But they don't stop there! They also say that West Virginians don't drink as much water as their out-of-state cousins, preferring to drink beer instead, so even if their water is more toxic, they'll be drinking less of it:

https://washingtonmonthly.com/2019/03/14/the-real-elitists-looking-down-on-trump-voters/

Even without any expertise in toxicology or water chemistry, I can tell that these are bullshit answers. The fact that the WV regulator accepted these comments tells me that they're not a good regulator. I was in WV last year to give a talk, and I didn't drink the tap water.

It's totally reasonable for non-experts to reject the conclusions of experts when the process by which those experts resolve their disagreements is obviously corrupt and irredeemably flawed. But some refusals carry higher costs – both for the refuseniks and the people around them – than my switching to bottled water when I was in Charleston.

Take vaccine denial (or "hesitancy"). Many people greeted the advent of an extremely rapid, high-tech covid vaccine with dread and mistrust. They argued that the pharma industry was dominated by corrupt, greedy corporations that routinely put their profits ahead of the public's safety, and that regulators, in Big Pharma's pocket, let them get away with mass murder.

The thing is, all that is true. Look, I've had five covid vaccinations, but not because I trust the pharma industry. I've had direct experience of how pharma sacrifices safety on greed's altar, and narrowly avoided harm myself. I have had chronic pain problems my whole life, and they've gotten worse every year. When my daughter was on the way, I decided this was going to get in the way of my ability to parent – I wanted to be able to carry her for long stretches! – and so I started aggressively pursuing the pain treatments I'd given up on many years before.

My journey led me to many specialists – physios, dieticians, rehab specialists, neurologists, surgeons – and I tried many, many therapies. Luckily, my wife had private insurance – we were in the UK then – and I could go to just about any doctor that seemed promising. That's how I found myself in the offices of a Harley Street quack, a prominent pain specialist, who had great news for me: it turned out that opioids were way safer than had previously been thought, and I could just take opioids every day and night for the rest of my life without any serious risk of addiction. It would be fine.

This sounded wrong to me. I'd lost several friends to overdoses, and watched others spiral into miserable lives as they struggled with addiction. So I "did my own research." Despite not having a background in chemistry, biology, neurology or pharmacology, I struggled through papers and read commentary and came to the conclusion that opioids weren't safe at all. Rather, corrupt billionaire pharma owners like the Sackler family had colluded with their regulators to risk the lives of millions by pushing falsified research that was finding publication in some of the most respected, peer-reviewed journals in the world.

I became an opioid denier, in other words.

I decided, based on my own research, that the experts were wrong, and that they were wrong for corrupt reasons, and that I couldn't trust their advice.

When anti-vaxxers decried the covid vaccines, they said things that were – in form at least – indistinguishable from the things I'd been saying 15 years earlier, when I decided to ignore my doctor's advice and throw away my medication on the grounds that it would probably harm me.

For me, faith in vaccines didn't come from a broad, newfound trust in the pharmaceutical system: rather, I judged that there was so much scrutiny on these new medications that it would overwhelm even pharma's ability to corruptly continue to sell a medication that they secretly knew to be harmful, as they'd done so many times before:

https://www.npr.org/2007/11/10/5470430/timeline-the-rise-and-fall-of-vioxx

But many of my peers had a different take on anti-vaxxers: for these friends and colleagues, anti-vaxxers were being foolish. Surprisingly, these people I'd long felt myself in broad agreement with began to defend the pharmaceutical system and its regulators. Once they saw that anti-vaxx was a wedge issue championed by right-wing culture war shitheads, they became not just pro-vaccine, but pro-pharma.

There's a name for this phenomenon: "schismogenesis." That's when you decide how you feel about an issue based on who supports it. Think of self-described "progressives" who became cheerleaders for the America's cruel, ruthless and lawless "intelligence community" when it seemed that US spooks were bent on Trump's ouster:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/12/18/schizmogenesis/

The fact that the FBI didn't like Trump didn't make them allies of progressive causes. This was and is the same entity that (among other things) tried to blackmail Martin Luther King, Jr into killing himself:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FBI%E2%80%93King_suicide_letter

But schismogenesis isn't merely a reactionary way of flip-flopping on issues based on reflexive enmity. It's actually a reasonable epistemological tactic: in a world where there are more issues you need to be clear on than you can possibly inform yourself about, you need some shortcuts. One shortcut – a shortcut that's failing – is to say, "Well, I'll provisionally believe whatever the expert system tells me is true." Another shortcut is, "I will provisionally disbelieve in whatever the people I know to act in bad faith are saying is true." That is, "schismogenesis."

Schismogenesis isn't a great tactic. It would be far better if we had a set of institutions we could all largely trust – if the black boxes where expert debate took place were sturdy, rectilinear and sharp-cornered.

But they're not. They're just not. Our regulatory process sucks. Corporate concentration makes it trivial for cartels to capture their regulators and steer them to conclusions that benefit corporate shareholders even if that means visiting enormous harm – even mass death – on the public:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/05/regulatory-capture/

No one hates Big Tech more than I do, but many of my co-belligerents in the war on Big Tech believe that the rise of conspiratorialism can be laid at tech platforms' feet. They say that Big Tech boasts of how good they are at algorithmically manipulating our beliefs, and attribute Qanons, flat earthers, and other outlandish conspiratorial cults to the misuse off those algorithms.

"We built a Big Data mind-control ray" is one of those extraordinary claims that requires extraordinary evidence. But the evidence for Big Tech's persuasion machines is very poor: mostly, it consists of tech platforms' own boasts to potential investors and customers for their advertising products. "We can change peoples' minds" has long been the boast of advertising companies, and it's clear that they can change the minds of customers for advertising.

Think of department store mogul John Wanamaker, who famously said "Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don't know which half." Today – thanks to commercial surveillance – we know that the true proportion of wasted advertising spending is more like 99.9%. Advertising agencies may be really good at convincing John Wanamaker and his successors, through prolonged, personal, intense selling – but that doesn't mean they're able to sell so efficiently to the rest of us with mass banner ads or spambots:

http://pluralistic.net/HowToDestroySurveillanceCapitalism

In other words, the fact that Facebook claims it is really good at persuasion doesn't mean that it's true. Just like the AI companies who claim their chatbots can do your job: they are much better at convincing your boss (who is insatiably horny for firing workers) than they are at actually producing an algorithm that can replace you. What's more, their profitability relies far more on convincing a rich, credulous business executive that their product works than it does on actually delivering a working product.

Now, I do think that Facebook and other tech giants play an important role in the rise of conspiratorial beliefs. However, that role isn't using algorithms to persuade people to mistrust our institutions. Rather Big Tech – like other corporate cartels – has so corrupted our regulatory system that they make trusting our institutions irrational.

Think of federal privacy law. The last time the US got a new federal consumer privacy law was in 1988, when Congress passed the Video Privacy Protection Act, a law that prohibits video store clerks from leaking your VHS rental history:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2008/07/why-vppa-protects-youtube-and-viacom-employees

It's been a minute. There are very obvious privacy concerns haunting Americans, related to those tech giants, and yet the closest Congress can come to doing something about it is to attempt the forced sale of the sole Chinese tech giant with a US footprint to a US company, to ensure that its rampant privacy violations are conducted by our fellow Americans, and to force Chinese spies to buy their surveillance data on millions of Americans in the lawless, reckless swamp of US data-brokerages:

https://www.npr.org/2024/03/14/1238435508/tiktok-ban-bill-congress-china

For millions of Americans – especially younger Americans – the failure to pass (or even introduce!) a federal privacy law proves that our institutions can't be trusted. They're right:

https://www.tiktok.com/@pearlmania500/video/7345961470548512043

Occam's Razor cautions us to seek the simplest explanation for the phenomena we see in the world around us. There's a much simpler explanation for why people believe conspiracy theories they encounter online than the idea that the one time Facebook is telling the truth is when they're boasting about how well their products work – especially given the undeniable fact that everyone else who ever claimed to have perfected mind-control was a fantasist or a liar, from Rasputin to MK-ULTRA to pick-up artists.

Maybe people believe in conspiracy theories because they have hundreds of life-or-death decisions to make every day, and the institutions that are supposed to make that possible keep proving that they can't be trusted. Nevertheless, those decisions have to be made, and so something needs to fill the epistemological void left by the manifest unsoundness of the black box where the decisions get made.

For many people – millions – the thing that fills the black box is conspiracy fantasies. It's true that tech makes finding these conspiracy fantasies easier than ever, and it's true that tech makes forming communities of conspiratorial belief easier, too. But the vulnerability to conspiratorialism that algorithms identify and target people based on isn't a function of Big Data. It's a function of corruption – of life in a world in which real conspiracies (to steal your wages, or let rich people escape the consequences of their crimes, or sacrifice your safety to protect large firms' profits) are everywhere.

Progressives – which is to say, the coalition of liberals and leftists, in which liberals are the senior partners and spokespeople who control the Overton Window – used to identify and decry these conspiracies. But as right wing "populists" declared their opposition to these conspiracies – when Trump damned free trade and the mainstream media as tools of the ruling class – progressives leaned into schismogenesis and declared their vocal support for these old enemies of progress.

This is the crux of Naomi Klein's brilliant 2023 book Doppelganger: that as the progressive coalition started supporting these unworthy and broken institutions, the right spun up "mirror world" versions of their critique, distorted versions that focus on scapegoating vulnerable groups rather than fighting unworthy institutions:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/05/not-that-naomi/#if-the-naomi-be-klein-youre-doing-just-fine

This is a long tradition in politics: hundreds of years ago, some leftists branded antisemitism "the socialism of fools." Rather than condemning the system's embrace of the finance sector and its wealthy beneficiaries, anti-semites blame a disfavored group of people – people who are just as likely as anyone to suffer under the system:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antisemitism_is_the_socialism_of_fools

It's an ugly, shallow, cartoon version of socialism's measured and comprehensive analysis of how the class system actually works and why it's so harmful to everyone except a tiny elite. Literally cartoonish: the shadow-world version of socialism co-opts and simplifies the iconography of class struggle. And schismogenesis – "if the right likes this, I don't" – sends "progressive" scolds after anyone who dares to criticize finance as the crux of our world's problems as popularizing "antisemetic dog-whistles."

This is the problem with "horseshoe theory" – the idea that the far right and the far left bend all the way around to meet each other:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/26/horsehoe-crab/#substantive-disagreement

When the right criticizes pharma companies, they tell us to "do our own research" (e.g. ignore the systemic problems of people being forced to work under dangerous conditions during a pandemic while individually assessing conflicting claims about vaccine safety, ideally landing on buying "supplements" from a grifter). When the left criticizes pharma, it's to argue for universal access to medicine and vigorous public oversight of pharma companies. These aren't the same thing:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/25/the-other-shoe-drops/#quid-pro-quo

Long before opportunistic right wing politicians realized they could get mileage out of pointing at the terrifying epistemological crisis of trying to make good choices in an age of institutions that can't be trusted, the left was sounding the alarm. Conspiratorialism – the fracturing of our shared reality – is a serious problem, weakening our ability to respond effectively to endless disasters of the polycrisis.

But by blaming the problem of conspiratorialism on the credulity of believers (rather than the deserved disrepute of the institutions they have lost faith in) we adopt the logic of the right: "conspiratorialism is a problem of individuals believing wrong things," rather than "a system that makes wrong explanations credible – and a schismogenic insistence that these institutions are sound and trustworthy."

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/25/black-boxes/#when-you-know-you-know

Image:

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (modified)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nrcgov/15993154185/

meanwell-packaging.co.uk

https://www.flickr.com/photos/195311218@N08/52159853896

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

#pluralistic#conspiratorialism#epistemology#epistemological crisis#mind control rays#opioid denial#vaccine denial#regulatory capture#boeing#corruption#inequality#monopoly#apple#dma#eu

291 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is epistemic violence?

To paraphrase Gayatri Spivak, the coiner of the term, epistemic violence is the systematic silencing of Othered (or, in Spivak's term, subaltern) groups via a refusal of the dominant group to hear them, and to understand their knowledge as legible or hearable at all. The effect of this is that marginal knowledges are iced out of dominant discourse.

More recently, philosopher Miranda Fricker has opened up new paths in this area with her book titled Epistemic Injustice. She describes two forms of epistemic injustice (testimonial, in which a knower's testimony is systematically delegitimized, and hermeneutic, in which a knower is not permitted the language with which to describe the conditions under which they live).

When I talk about epistemic injustice, I am thinking about Spivak and Fricker's more recent interventions. Spivak is also drawing on her reading of Foucault, who used the term "biopower" to describe the productive power of state efforts to make [populations] live (in conditions of silence, marginality, toil, etc.) and let them die (by knowingly abandoning the noncompliant –– including those who do not submit to the epistemic conditions required of them).

270 notes

·

View notes

Text

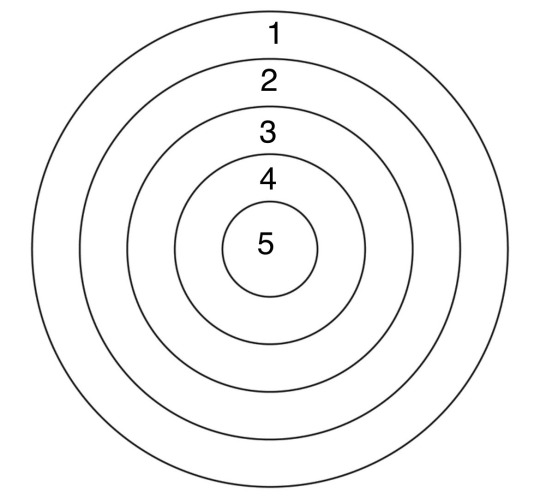

A Ward against Hubris

All Knowledge

All Knowledge that has been written down

All Knowledge that has been written down and is accessible via internet

All Knowledge that has been written down in a language that you can read and is accessible via internet

All Knowledge that you have gained via the internet

115 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Before Kant, an inquiry into "the nature and origin of knowledge" had been a search for privileged inner representations. With Kant, it became a search for the rules which the mind had set up for itself (the "Principles of the Pure Understanding"). This is one of the reasons why Kant was thought to have led us from nature to freedom. Instead of seeing ourselves as quasi-Newtonian machines, hoping to be compelled by the right inner entities and thus to function according to nature's design for us, Kant let us see ourselves as deciding (noumenally, and hence unconsciously) what nature was to be allowed to be like. Kant did not, however, free us from Locke's confusion between justification and causal explanation, the basic confusion contained in the idea of a "theory of knowledge."

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature#Kant#belief#representation#justification#causality#knowledge#epistemology

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

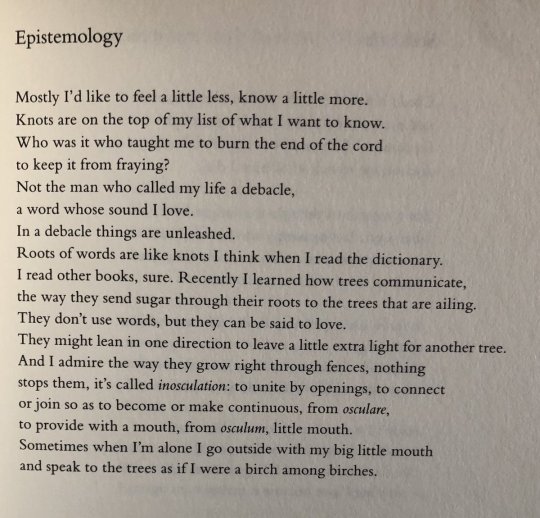

Catherine Barnett, 'Epistemology', 2017

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Curiosity

The philosophy of curiosity explores the nature, origins, and implications of human curiosity, which drives individuals to seek knowledge, explore new experiences, and ask questions about the world around them. Curiosity has long been recognized as a fundamental aspect of human cognition and behavior, playing a central role in scientific inquiry, philosophical reflection, and everyday life. Here are some key aspects and theories within the philosophy of curiosity:

Epistemic Curiosity: Epistemic curiosity refers to the desire for knowledge and understanding, motivating individuals to seek information, explore new ideas, and engage in intellectual pursuits. Philosophers have debated the nature of epistemic curiosity, its origins in human cognition, and its role in shaping scientific progress and cultural development.

Aesthetic Curiosity: Aesthetic curiosity pertains to the exploration of beauty, art, and creativity, driving individuals to seek out new experiences, appreciate diverse forms of expression, and engage with works of literature, music, visual art, and other cultural artifacts. Aesthetic curiosity raises questions about the nature of artistic inspiration, cultural interpretation, and subjective experience.

Existential Curiosity: Existential curiosity concerns the exploration of existential questions about the nature of existence, meaning, and purpose, motivating individuals to reflect on their own lives, values, and beliefs. Existential curiosity encompasses inquiries into topics such as the nature of consciousness, the search for transcendence, and the quest for personal fulfillment.

Philosophical Curiosity: Philosophical curiosity involves the pursuit of philosophical inquiry, critical thinking, and self-reflection, prompting individuals to question assumptions, challenge conventional wisdom, and explore fundamental concepts such as truth, morality, justice, and reality. Philosophical curiosity underlies the practice of philosophy as a discipline and informs broader intellectual endeavors.

Ethical Curiosity: Ethical curiosity concerns the exploration of ethical questions and moral dilemmas, motivating individuals to consider the consequences of their actions, empathize with others, and strive for moral growth and development. Ethical curiosity raises questions about the nature of moral values, ethical principles, and the pursuit of the good life.

Cognitive Curiosity: Cognitive curiosity encompasses the exploration of cognitive processes, mental states, and psychological phenomena, driving individuals to understand how the mind works, how knowledge is acquired, and how beliefs are formed. Cognitive curiosity informs research in fields such as psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science.

Cultural Curiosity: Cultural curiosity involves the exploration of diverse cultures, traditions, and worldviews, prompting individuals to learn about different societies, languages, and customs, and to appreciate the richness of human diversity. Cultural curiosity fosters intercultural understanding, global awareness, and cross-cultural communication.

Metacognitive Curiosity: Metacognitive curiosity pertains to the exploration of one's own cognitive processes and learning strategies, motivating individuals to reflect on their own thinking, monitor their own understanding, and adapt their learning strategies to achieve greater intellectual growth and self-improvement.

Overall, the philosophy of curiosity explores the multifaceted nature of human curiosity and its profound influence on knowledge, creativity, personal growth, and the human condition.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#chatgpt#education#psychology#Epistemic curiosity#Aesthetic curiosity#Existential curiosity#Philosophical curiosity#Ethical curiosity#Cognitive curiosity#Cultural curiosity#Metacognitive curiosity#Human cognition#Inquiry#Exploration#Intellectual curiosity#Human experience#Curiosity and creativity#Curiosity and learning

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The jobs of the magician, the priest, the mathematician, the psychiatrist, and the philosopher are approximately all the same: to let you know what deep shit you're in so that you can begin trying to save yourself.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Epistemology and Why It Matters for Witchcraft

Epistemology, as one of my professors articulated, is "the study of truth." It's the theory of knowledge, investigating what we consider to be fact/truth and how we decide what constitutes reality. The scope goes way beyond just spiritual/religious belief, but that's what I'll primarily be discussing here.

That's really vague and esoteric, so to give a more concrete example: think about Hell. To many folks, Hell is entirely fictional, just a theory used to scare people into submission. Others believe the existence of Hell is a cold hard fact. To them, taking steps to avoid going to Hell is a very real and legitimate thing to be concerned about, because that's a part of how they perceive reality. Both "sides" have equal conviction, because both consider their belief to be the truth. Epistemology asks why that is. How do we get two equally-strong, opposite beliefs?What makes people consider something opinion vs. fact? What makes people change their mind? How do we decide these ways of measuring "truth" are accurate? How do we decide what's accurate? This keeps going indefinitely. Don't give yourself an existential crisis over it.

A lot of arguments debates pop up in spiritual/religious communities when people butt heads with opposing beliefs, both considered fact by someone. Someone believes that intent is the only thing that matters when practicing witchcraft just as much as I believe that's bullshit. Both of us have our reasons why, also based on things we consider fact. We might even have the same beliefs backing our opinion, just arranged differently. Neither of us have any way to prove our belief is "true."

This is important to keep in mind for many things.

Interacting with the community in general. Is that person an idiot or are they just coming at it from a different perspective? Are you bothered because they're actually being rude, or because it's in conflict with your own beliefs?

Analyzing resources. What beliefs and assumptions does the author hold beyond the specific thing they're conveying here? How is it influencing their take? Is it congruent with how I believe the world works?

Analyzing yourself. What do I believe?How did I form these beliefs, what's behind them? Do I feel like I need to update anything? I'm allowed to decide I was "wrong" about something before. Are my actions in line with these beliefs, or holdovers from an old way of thinking?

Assessing the results of your craft. How do I measure when something was effective? How much faith and skepticism and I comfortable putting into the process? Am I coming to this from a perspective I consider balanced and rational?

It's honestly helpful for way more than just spiritual practices, but it's especially important when dealing with things as esoteric as, well, esotericism, mysticism, the occult, and spiritual practices. It may not be healthy to constantly question yourself and everything you know, but an occasional, compassionate check-in can really elevate a person's work. That's my belief, anyway! What's yours?

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

All knowable light is shadow.

Ahmed Salman

#quote#light#shadow#AHMED#darkness#knowledge#ignorance#transcendence#philosophy#infinite#unknowable#intelligence#epistemology

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

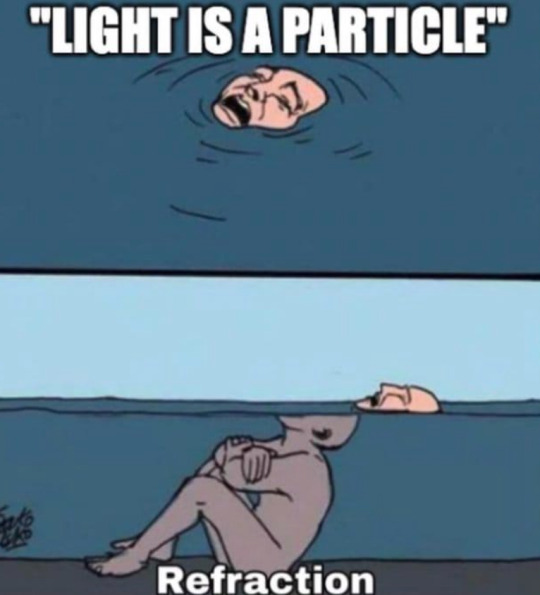

Ok, light is both, or neither. 😎

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You know, I never meant for people to believe in the Turtle," said Didactylus unhappily. "It's just a big turtle. It just exists. Things just happen that way. I don't think the Turtle gives a damn. I just thought it might be a good idea to write things down and explain things a bit."

Terry Pratchett, Small Gods

#Didactylus#great a'tuin#small gods#Discworld#terry pratchett#Philosophers#Scientists#Belief#Facts#Reality#Epistemology#Good idea#Turtles#Natural laws#explanation#Things just happen that way#The turtle doesn't give a damn

187 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Sorry if you’ve posted about this somewhere already/if it’s redundant, but I thought your coinage of “transMad” was very cool and I’m wondering what that term means to you? I’m really happy to see other people talking about madness being intertwined w their gender/transness and looking forward to checking out your reading lists :))

thank you so much for asking about one of my favorite things to infodump about!! rather than rehash a bunch of stuff, if it's okay, I'm going to borrow a few quotes from past!me that i've published in different places // offer you some things of mine to read.

broadly, though, i use transMadness as a way to explore the identificatory, epistemological, methodological, and theoretical implications of an orientation (to use Sara Ahmed's term) toward bodymind noncompliance and self/selves-determination. this orientation refuses to delineate diagnostically between Maddened / transed experiences of the world/our many worlds, and instead takes this shared/overlapping ground as a jumping off point for solidarity and speculation - that is, something that allows us to imagine otherwise worlds / make them manifest through creativity and collaboration.

(Ha, and I claimed i wouldn't talk too much...famous autistic last words)

ANYWAY. here are some clips that might help explain more dimensions of transMadness. note that, in my dissertation-in-progress, i'm focusing on xeno/neogender and/as self-diagnostic cultures among queercrip and transMad internet users. i'm interested in the anti-psych liberatory potential of this digital community work, especially as it centers forms of knowledge and scholarship devalued within Academia Proper, especially because so much of it is made by and for disabled, Mad, queer, trans people, esp. youth. Onward to quotes!

On transMad epistemologies: citation/power/knowledge:

I’ll spend most of this piece looking not at what transMad is, but what it does. First and foremost, transMad cites. Even its name alludes to other portmanteaus: neuroqueer and queercrip being the best-known among them. Many people have offered many different (ever-“working”!) definitions of these terms; today, I offer co-coiner Nick Walker’s (2021) definition of neuroqueer: a verb and an adjective “encompass[ing] the queering of neurocognitive norms as well as gender norms” (p. 196). In terms of queercrip, I also return to its coiner, Carrie Sandahl (2003), who for whom the queercrip (as person and as method/movement) confuses the diagnostic gaze, bears sociopolitical witness, and performs glitchful[4], incongruous, confusing in(ter)ventions into possible community. At base, “queer” and “crip” appear as analogous, reclaimed slurs signifying marginalized transgression. When combined, they describe a loop, perhaps a Möbius strip: crip (ani)mates queer, queer tells-on crip. The specter of crip haunts queer—and even more explicitly, as we will see, trans—and the crip(ped) bodymind holds, moves, and fucks queerly. Who knows where “queer” stops and “crip” and “neuro” begin? Likewise, transMad, whose citational style leaves little room for diagnostic clarity amidst a pastiche of noncompliant text.

On transMad epistemologies: multiplicity (h/t @materialisnt):

They encourage us to remove others’ names from our bodies, to reign in unruly citations, to set “boundaries” which violate Mad, crip ethics of care (see Fletcher, 2019). In truth, any framing of individual authorship in which the body text is “mine” and the citations gesture “elsewhere” belie the inherent interdependence of all intellectual life, and particularly of transMad intellectual life. transMad plural scholar mix. alan moss (2022) argues in relation to the pathologization of multiple systems: “all people, indeed all that exists, is a system that itself is constantly enmeshed in several overlapping and interconnected systems.” In short, I am full of Is, and will continue as many more. Just as disability justice helps us understand all life as interdependent and deserving of access, a transMad approach sees our selves as numerous and fuzzy. We have permission to dispense with the need for tidy texts, with our interlocutors, edits, and iterations either obfuscated entirely or exclusively relegated to a bibliography. transMad citation may thus be considered akin to visible mending[6], creating flamboyantly messy, multiplicitous work that does not seek to pass as objective or discrete.

On the value of (crip) failure and/as "virtuality":

Don’t get me wrong: Zoom PhD work is a failing enterprise. That is to say, it is a queercrip, transMad enterprise, which is to say, it is a beautiful, beautiful project. Mitchell, Snyder, and Ware describe such “fortunate failures” in the context of “curricular cripistemologies.”5 Coined by Merri Lisa Johnson, the term “cripistemologies,” refers to “embodied ways of knowing in relation, knowing-with, knowing-alongside, knowing-across-difference, and unknowing,” ways which frequently exist outside the purview of mainstream academia.6 Curricular cripistemologies, then, refer to an intentional, queercrip deviation from normative pedagogical approaches which trades the corrective impulse of “special ed” and other rehabilitative programs, and offers instead a generative noncompliance.7 That is, rather than trying to identify, isolate, and ameliorate difference, curricular cripistemologies lean into difference as it is experienced by disabled students ourselves, querying how atmospheres of in/accessibility shape normative approaches to education and how the embrace of “failure,” not as a last-resort but as a first choice, poses potentially transformative possibilities.

On transMadness and fat liberation: (for @trans-axolotl's Psych Survivor Zine)

A transMad, fat approach to disorderly eating requires making connections with humility and understanding, and, as I discussed above, engaging in compassionate, critical interrogation of our own anti-fatness.

[...]

A transMad, fat, abolitionist politic is one that makes room. We imagine beyond the cage, even if the details of that imagining are not yet clear. Just as we have carved micro-sites of support within violent digital and in-person contexts, just as we have learned to think about our lifeworlds beyond the paradigm of “recovery or death,” we can also reconceptualize fatness not as the enemy, but as another form of bodymind noncompliance in alliance and/or entanglement with disorderly eating practices. For thin disorderly eaters, this requires us to fundamentally challenge the way we view food and embodiment, even while maintaining a Mad respect for alternative ways of approaching reality.

On xenogenders, virtuality, and self-determination:

It is this very “irrationality” –– the “unrealness,” the “you’ve-got-to-be-kiddinghood,” that is most frequently weaponized against xenogenders, as well as their newly-coined sets of xenopronouns. The perceived and actual virtuality of xenogenders is often placed against the notion of “actuality,” in this case, of “real” (or “practical”) genders and pronouns to be used in one’s “real life.” Disabled activists have rightly resisted the distinction between online and (presumed-offline) “real life,” given that this categorically excludes homebound bodyminds, as well as those without IRL social and support circles. That said, I believe the virtual –– as almost, not-quite, proximite, making-do –– is incredibly useful in thinking about xenoidentities as transMad tools –– particularly, as transMad tools of underground collaboration / co-liberation.

[...]

What if gender was a project we wanted to fail? That is, what if trans- was a process not of getting better, not of moving-toward a bodymind more sane, more straight, and more cisheteropatriarchially desirable, but rather a line of flight on a longer trail to illegibility? Indeed, what if we replaced pathology’s narrow “path” with a trail lighted by the language of our comrades, whose linguistic interventions make and break gender in ways heretofore unimaginable? Xenoidentities, both individually and as a trans-gressive M.O., are fundamental to a broader transMad project of crafted, collective illegibility; intersubjective citation (imagine what it feels like for someone to be the gender that you coined!); and collective care that refuses a politics of cure. Crucially both virtual and digital, xenoidentities are furthermore a manifestation of the power of trans, predominantly disabled digital counterpublics, who overturn the hierarchy which places the IRL-real above the digital-unreal, making unruly, Mad space in which (with apologies to Donna Haraway) a hundred xenoselves might bloom.

On Maddening queer "diagnosis":

In her indictment of all “Kwik-Fix Drugs,” Gray further indicates the practice of forced treatment as in and of itself as a project of violent normalization, regardless of specific target or reason. The intentional ambiguity between her narrative of Madness and her narrative of asexuality disrupt mounting demands for a healthy (sanitized, neoliberal, and consumable) queerness. A Mad ace approach identifies these demands as, indeed, comparable with cis heteronormative notions of sexual maturity and responsibility – the idea that participation in culturally-normative sexual practices is a prerequisite for health (Kim, 2011, 481) and thus, personal autonomy (Meerai, Abdillahi, and Poole 2016, 21). By fusing the “lack of sexual appetite” attributed to her medications for bipolar disorder with her asexuality, Gray destabilizes the binary between healthy-sexual-diversity and unhealthy-psychopathology. She is once again disrupting contemporary queer impulses to dissociate from ongoing histories of pathologization. Here, Mad and queer/asexual activism are as inseparable in text as they are in Gray.

Gray and her comrades collectively refuse both sexuality-as-“rehabilitation” (See Kim 2011, 486) and asexual acceptance predicated upon normative “health” (Kim 2010, 158) – that is, they Madden asexuality. Twoey, in her own voice, remixes the sources of her own pathologization, staggering the supposedly-divine pronouncement of the DSM across pages and bookending its extracts with her own writing and art. In this undermining of the DSM’s epistemological polish, Gray disrupts the domination of written prose over poetry and visual art, while also critiquing the role of the DSM in commercialized health “care.” Her zine opens with the lines “sex sells and sex is sold / sex was being sold and i didn’t buy” (Gray 2018, n.p.). Gray indicates a pathology perceived not only in a refusal to practice sex, but also in a refusal to buy (into) it. After all, a refusal to buy into existing sexual paradigms is for her also a refusal to buy into a feminized reproductive mandate.

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

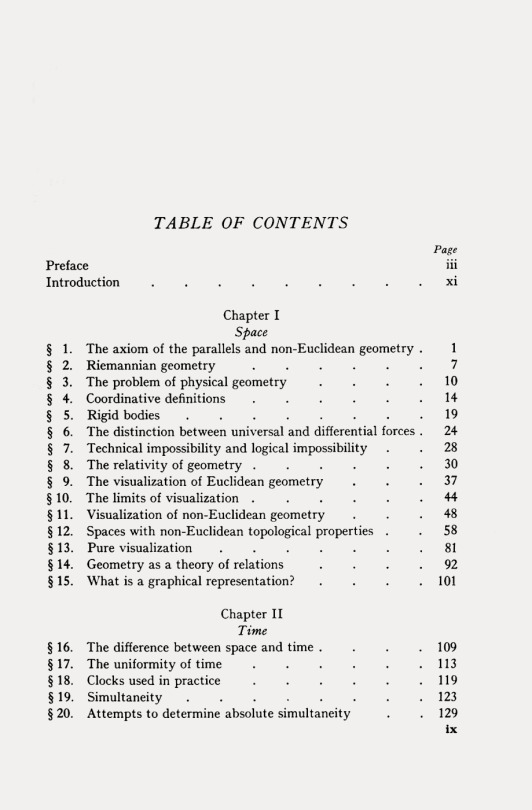

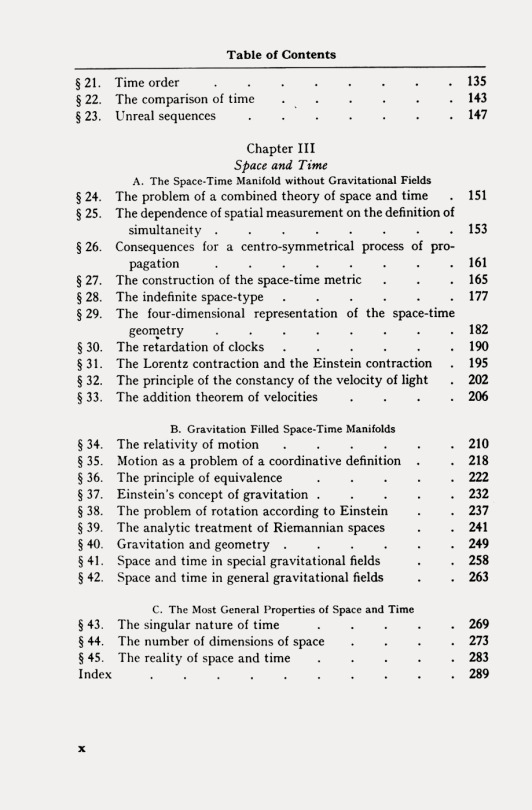

Hans Reichenbach, (1928), The Philosophy of Space & Time, Translated by Maria Reichenbach and John Freund, with introductory remarks by Rudolf Carnap, Dover Publications, New York, NY, 1958. Cover designed by Menten Inc.

#graphic design#philosophy#philosophy of science#epistemology#book#cover#book cover#hans reichenbach#maria reichenbach#john freund#rudolf carnap#dover publications#menten inc.#1920s#1950s

99 notes

·

View notes