#idealism

Quote

Reality is infinitely diverse, compared with even the subtlest conclusions of abstract thought, and does not allow of clear-cut and sweeping distinctions. Reality resists classification.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The House of the Dead

#philosophy#quotes#Fyodor Dostoyevsky#The House of the Dead#reality#abstraction#abstract#idealism#realism#distinctions#language

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

@heiiocoie

#feelings#coming of age#quotes#web weaving#web weavings#web weave#on hope#hope#romanticism#romanticize#romantic academia#light academia#light acadamia aesthetic#love#optimism#resilience#idealism#idealistic#escapism#musings#thoughts#on life#on living#on love#humanity#on humanity#peoplehood

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

And now let us believe in a long year that is given to us, new, untouched, full of things that have never been, full of work that has never been done, full of tasks, claims, and demands; and let us see that we learn to take it without letting fall too much of what it has to bestow upon those who demand of it necessary, serious, and great things.

Rainer Maria Rilke

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

Newsworthy: a collection of weird headlines and book titles.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think a lot of the uproar whenever socialists suggest abolishing family and religion of the kind that is best expressed in this sentence: “how can you abolish religion and family, how would we then preserve traditional culture, it would mean cultural genocide and imperialism” stems from a fundamentally idealist understanding of the world. One that misunderstands Marx’s materialist view of history.

I mean idealism in the sense that ideas and culture drive history and societal change. Basically the course of history is decided by a struggle of ideas. This conflict is either peaceful in the liberal sense that people use reason to convince other people of their views, or it is waged by military means, and these military conflicts are seen as motivated by ideology, with the winner imposing their views on the conquered.

This idea is also driven by essentialist ideas literally coming from nationalism and religious “family values” conservatism, that religion, the family and ethnic identity are fundamental to human existence. And the only way for them to go away is for some authoritarian state to force people to give them up.

This creates a fantasy that abolition of family and religion will mean a totalitarian “communist state” using violence to force religious people to give up religion and breaking up families. And I presume said state waging war to force the rest of the world to give up religion and family. Literal cultural genocide with death squads. This fantasy seems to be inspired in part by Hoxhaist Albania’s “state atheism” and European colonialism forcing christianity on Africa and the Americas.

This fantasy however badly misunderstands the Marxian materialist perspective on culture, including family, ethnicity and religion, which is the basis for our predictions about the end of family and religion.

The short version is that we believe that the mode of production determines culture. Cultural institutions like family and religion and all of culture is dependent on certain modes of production, whether that will be feudal, capitalist or socialist. “The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. “ as Marx said. And that by removing the capitalist economic foundation on which family and religion as we now know it stands, a socialist revolution will lead to those institutions naturally being destroyed. People will want to abandon religion and the family because in the socialist system, it will no longer make any sense to them.

Religion acts as both moral justification of and consolation for the sufferings of a class society. A socialist society would not be “a condition that requires illusions” as Marx put it. And as Engels explained all the way back in 1847, communism will end the family “since it does away with private property and educates children on a communal basis, and in this way removes the two bases of traditional marriage – the dependence rooted in private property, of the women on the man, and of the children on the parents.“

One might object that the institutions of the family and religion have survived previous such revolutions, like the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Doesn’t that prove that they are permanent fixtures of human nature? But communism will be something radically different, as the The Communist manifesto explains:

“The history of all past society has consisted in the development of class antagonisms, antagonisms that assumed different forms at different epochs.

But whatever form they may have taken, one fact is common to all past ages, viz., the exploitation of one part of society by the other. No wonder, then, that the social consciousness of past ages, despite all the multiplicity and variety it displays, moves within certain common forms, or general ideas, which cannot completely vanish except with the total disappearance of class antagonisms.

The Communist revolution is the most radical rupture with traditional property relations; no wonder that its development involved the most radical rupture with traditional ideas. “

It’s a contradiction in terms to want to “preserve culture” and also want to radically change the economic foundation on which culture stands, any type of “left-wing” position that claims to do both is ridiculous. A wish to “preserve traditional culture” can only lead to a reactionary position, one in which society is kept in stasis, or somehow returned to an earlier state, a stasis which preserves both the economic foundation and with it the culture.

And of course no such stasis has ever actually existed. No economic system and its cultural superstructure is truly static, as history proves. Every culture has gone through multiple cycles of death and rebirth, the most serious are periods of social revolution that transition from one mode of production to another. But between those periods there is usually a constant process of cultural evolution. In the end all cultures have gone though a ship-of-theseus-like total transformation multiple times.

As the manifesto puts it: “What else does the history of ideas prove, than that intellectual production changes its character in proportion as material production is changed? The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class. “

In fact, because capitalism is not a static system, we can see changes already happening in existing societies. The widespread secularization in the most advanced capitalist countries in western Europe, for example, shows how the decline of religion can happen peacefully and naturally. It wasn’t violent repression that has caused Swedes to abandon the Lutherean Christanity that once heavily defined Swedish culture, it was because it no longer made any sense in an advanced capitalist society.

In a socialist revolution, there will probably be violence, but it would largely be the reactionaries who would cause it. There was revolutionary violence against the Orthodox Church in the Russian revolution and against the Catholic Church in the Spanish revolution, but that was because the churches sided with the forces of reaction. And the men who benefit from the family, actual patriarchs, will probably react with violence towards any attempt to lessen their power. Even as we speak, men often react to women divorcing them by stepping up their abusive violence.

As for the accusation of imperialism, it’s true that this revolution will be global, because there is no other way to defeat global capitalism. “It is a universal revolution and will, accordingly, have a universal range.” as Engels put it. But it will have to be the work of the working class themselves, which precludes a state, local or foreign/imperialist, doing it for them.

As the manifesto puts it: “In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.”

For more information on Marx’s material conception of history, just read Marx and Engels. This is basically all based on Marx’s works specifically. It’s why I don’t use terms like “dialectical materialism” or “historical materialism” or even “marxism”, because he didn’t use those terms, those descriptions came from later interpreters of his work, but that’s outside the scope of this text.

The works I quoted above are a good starting point. The preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy has a great introduction to his views, Marx himself summarizes them in a single paragraph and the whole book is worth reading. Regarding religion, another preface that states Marx’s view very clearly is the often-quoted introduction to A Contribution to the critique of Hegel’s philosophy of right, the source of the “religion is the opium of the people” quote. The Communist Manifesto is of course worth reading and quoted at length above. Engels wrote a FAQ-style draft of the manifesto called The Principles of Communism in 1847 that quite literally answers common questions about communism, particularly relevant to this post are the answers to questions 19-23.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vemos lo que queremos para sentirnos como mejor nos conviene; y ¿qué es la conveniencia si no aquella con antítesis naturaleza resultante de sus maneras subjetivas?

- Melady Guizado, El precio de la idealización (2024).

#tumblr#mis citas#mis notas#mis escritos#melady guizado#frases#escritos#amor#citas#desamor#idealization#idealizar#idealism#idealistic#idealización#notas de dolor#notas de vida#citas reflexivas#citas de reflexion#reflexiondeldia#frases reflexivas#notas de amor

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It shouldn't be like this."

"There isn't a way things should be. There's just what happens, and what we do."

"Well, couldn't you help him by magic?"

"I see to it that he's in no pain, yes," said Miss Level.

"But that's just herbs."

"It's still magic. Knowing things is magical, if other people don't know them."

Terry Pratchett, A Hat Full of Sky

#tiffany aching#miss level#a hat full of sky#discworld#terry pratchett#magic#medicine#witches#life#life philosophy#knowledge#context#idealism#pragmatism#education#the way things should be#the way it is#knowing things is magical

406 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing in The New York Times the photograph of Helen Keller in the Observation Tower of the Empire State Building, I [Dr. John H. Finley] wrote her asking her what she really “saw” from that height. This remarkable letter written by her came in answer and was published in The New York Times Magazine. It will be agreed by all who read it that, as she said, she “beheld a brighter prospect than my friends with two good eyes.”

January 13, 1932

Dear Dr. Finley:

After many days and many tribulations which are inseparable from existence here below, I sit down to the pleasure of writing to you and answering your delightful question, “What Did You Think ‘of the Sight’ When You Were on the Top of the Empire Building?”

Frankly, I was so entranced “seeing” that I did not think about the sight. If there was a subconscious thought of it, it was in the nature of gratitude to God for having given the blind seeing minds. As I now recall the view I had from the Empire Tower, I am convinced that, until we have looked into darkness, we cannot know what a divine thing vision is.

Perhaps I beheld a brighter prospect than my companions with two good eyes. Anyway, a blind friend gave me the best description I had of the Empire Building until I saw it myself.

Do I hear you reply, “I suppose to you it is a reasonable thesis that the universe is all a dream, and that the blind only are awake?” Y—es—no doubt I shall be left at the Last Day on the other bank defending the incredible prodigies of the unseen world, and, more incredible still, the strange grass and skies the blind behold are greener grass and bluer skies than ordinary eyes see. I will concede that my guides saw a thousand things that escaped me from the top of the Empire Building, but I am not envious. For imagination creates distances and horizons that reach to the end of the world. It is as easy for the mind to think in stars as in cobble-stones. Sightless Milton dreamed visions no one else could see. Radiant with an inward light, he sent forth rays by which mankind beholds the realms of Paradise.

But what of the Empire Building? It was a thrilling experience to be whizzed in a “lift” a quarter of a mile heavenward, and to see New York spread out like a marvellous tapestry beneath us. There was the Hudson—more like the flash of a sword-blade than a noble river. The little island of Manhattan, set like a jewel in its nest of rainbow waters, stared up into my face, and the solar system circled about my head! Why, I thought, the sun and the stars are suburbs of New York, and I never knew it! I had a sort of wild desire to invest in a bit of real estate on one of the planets. All sense of depression and hard times vanished, I felt like being frivolous with the stars. But that was only for a moment. I am too static to feel quite natural in a Star View cottage on the Milky Way, which must be something of a merry-go-round even on quiet days.

I was pleasantly surprised to find the Empire Building so poetical. From everyone except my blind friend I had received an impression of sordid materialism—the piling up of one steel honeycomb upon another with no real purpose but to satisfy the American craving for the superlative in everything. A Frenchman has said, in his exalted moments the American fancies himself a demigod, nay, a god; for only gods never tire of the prodigious. The highest, the largest, the most costly is the breath of his vanity.

Well, I see in the Empire Building something else—passionate skill, arduous and fearless idealism. The tallest building is a victory of imagination. Instead of crouching close to earth like a beast, the spirit of man soars to higher regions, and from this new point of vantage he looks upon the impossible with fortified courage and dreams yet more magnificent enterprises.

What did I “see and hear” from the Empire Tower? As I stood there ’twixt earth and sky, I saw a romantic structure wrought by human brains and hands that is to the burning eye of the sun a rival luminary. I saw it stand erect and serene in the midst of storm and the tumult of elemental commotion. I heard the hammer of Thor ring when the shaft began to rise upward. I saw the unconquerable steel, the flash of testing flames, the sword-like rivets. I heard the steam drills in pandemonium. I saw countless skilled workers welding together that mighty symmetry. I looked upon the marvel of frail, yet indomitable hands that lifted the tower to its dominating height.

Let cynics and supersensitive souls say what they will about American materialism and machine civilization. Beneath the surface are poetry, mysticism and inspiration that the Empire Building somehow symbolizes. In that giant shaft I see a groping toward beauty and spiritual vision. I am one of those who see and yet believe.

I hope I have not wearied you with my “screed” about sight and seeing. The length of this letter is a sign of long, long thoughts that bring me happiness.

I am, with every good wish for the New Year,

Sincerely yours,

Helen Keller

Top photo: Times Wide World Photos/Letters of Note

Bottom photo: Associated Press

#vintage New York#1930s#Helen Keller#Empire State Building#Empire State Bldg.#Jan. 13#13 Jan.#blind#deaf#imagination#seeing blind#how blind see#idealism#materialism#American materialism

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“When I Met You”

(Bust of Akhenaten, Neues Museum in Berlin)

#akhenaten#egypt#sculpture#twins#gemini#kiss#dialog#berlin museum#reflection#diary#idealism#ancient mystery#self love

75 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Real life is, to most men, a long second-best, a perpetual compromise between the ideal and the possible; but the world of pure reason knows no compromise, no practical limitations, no barrier to the creative activity embodying in splendid edifices the passionate aspiration after the perfect from which all great work springs.

Bertrand Russell, The Study of Mathematics

#philosophy#quotes#Bertrand Russell#The Study of Mathematics#ideals#idealism#possibility#reason#rationality

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

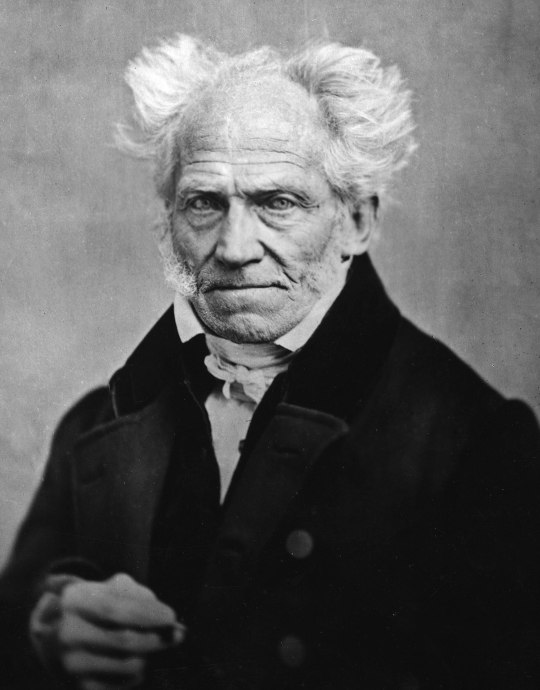

"Why read Hegel? It is a good question, one no Hegel scholar should shirk. After all, the burden of proof lies heavily on his or her shoulders. For Hegel's texts are not exactly exciting or enticing. Notoriously, they are written in some of the worst prose in the history of philosophy. Their language is dense, obscure and impenetrable. Reading Hegel is often a trying and exhausting experience, the intellectual equivalent of chewing gravel. 'And for what?' a prospective student might well ask. To avoid such an ordeal, he or she will be tempted to invoke the maxim of one of Hegel's old enemies whenever he lost patience with a tiresome book: 'Life is short!' [Footnote revealing that the enemy is Schopenhauer]"

— Frederick Beiser, from “Hegel”

#frederick beiser#georg wilhelm friedrich hegel#hegel#german philosophy#philosophy#german idealism#idealism#19th century#arthur schopenhauer#schopenauer#lit#literature

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

#reality#perception#idealism#disappointment#expectations#relationships#self-awareness#self-reflection#honesty#communication#authenticity

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“A high degree of intellect tends to make a man unsocial.”

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation.

#Pessimism#Will and Representation#Metaphysics#Ethics#Existentialism#Philosophy of Mind#Kantianism#Aesthetics#Solipsism#Nihilism#Idealism#Compassion#Individualism#World as Illusion#Transcendental Idealism#Suffering#The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason#Eastern Philosophy Influence#Art and Beauty#Critique of Hegel's Philosophy#today on tumblr#quoteoftheday

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

one thing that i really appreciated in tsotl that i wasn’t able to articulate until recently is clarice’s relationship with idealism, and the way that its framed: clarice fails to save the one lamb she could carry in her past, but that desire to save lives, even if it is just one, is never ridiculed within the story. instead, even in jaded circumstances in a less-than-perfect world, she saves catherine martin. there is no scene where clarice is shown that this desire to help others is foolish, no, she wins on her own terms, she’s saved that one lamb. saving one person is enough—catherine martin walks out of that house alive, and if that isn’t uplifting then i don’t know what is

#tsotl#the silence of the lambs#clarice starling#catherine martin#horror tropes#idealism#movie analysis#while the movie is far from perfect#i feel i can still really appreciate clarice’s character arc#like#a strong female character who is kicks ass AND is complex AND is empathetic AND is allowed a happy ending on her own terms?#yes please#the fact that im even talking about this proves theres still a long ways to go with modern cinema though#idealism and hope not as ephemeral concepts#but as digging your hands into the dirt and screaming at god

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 notes

·

View notes