#vasily grossman

Text

In the terrible winter of 1932–33, brigades of Communist Party activists went house to house in the Ukrainian countryside, looking for food. The brigades were from Moscow, Kyiv, and Kharkiv, as well as villages down the road. They dug up gardens, broke open walls, and used long rods to poke up chimneys, searching for hidden grain. They watched for smoke coming from chimneys, because that might mean a family had hidden flour and was baking bread. They led away farm animals and confiscated tomato seedlings. After they left, Ukrainian peasants, deprived of food, ate rats, frogs, and boiled grass. They gnawed on tree bark and leather. Many resorted to cannibalism to stay alive. Some 4 million died of starvation.

At the time, the activists felt no guilt. Soviet propaganda had repeatedly told them that supposedly wealthy peasants, whom they called kulaks, were saboteurs and enemies—rich, stubborn landowners who were preventing the Soviet proletariat from achieving the utopia that its leaders had promised. The kulaks should be swept away, crushed like parasites or flies. Their food should be given to the workers in the cities, who deserved it more than they did. Years later, the Ukrainian-born Soviet defector Viktor Kravchenko wrote about what it was like to be part of one of those brigades. “To spare yourself mental agony you veil unpleasant truths from view by half-closing your eyes—and your mind,” he explained. “You make panicky excuses and shrug off knowledge with words like exaggeration and hysteria.”

He also described how political jargon and euphemisms helped camouflage the reality of what they were doing. His team spoke of the “peasant front” and the “kulak menace,” “village socialism” and “class resistance,” to avoid giving humanity to the people whose food they were stealing. Lev Kopelev, another Soviet writer who as a young man had served in an activist brigade in the countryside (later he spent years in the Gulag), had very similar reflections. He too had found that clichés and ideological language helped him hide what he was doing, even from himself:

I persuaded myself, explained to myself. I mustn’t give in to debilitating pity. We were realizing historical necessity. We were performing our revolutionary duty. We were obtaining grain for the socialist fatherland. For the five-year plan.

There was no need to feel sympathy for the peasants. They did not deserve to exist. Their rural riches would soon be the property of all.

But the kulaks were not rich; they were starving. The countryside was not wealthy; it was a wasteland. This is how Kravchenko described it in his memoirs, written many years later:

Large quantities of implements and machinery, which had once been cared for like so many jewels by their private owners, now lay scattered under the open skies, dirty, rusting and out of repair. Emaciated cows and horses, crusted with manure, wandered through the yard. Chickens, geese and ducks were digging in flocks in the unthreshed grain.

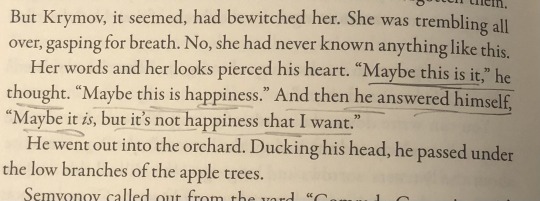

That reality, a reality he had seen with his own eyes, was strong enough to remain in his memory. But at the time he experienced it, he was able to convince himself of the opposite. Vasily Grossman, another Soviet writer, gives these words to a character in his novel Everything Flows:

I’m no longer under a spell, I can see now that the kulaks were human beings. But why was my heart so frozen at the time? When such terrible things were being done, when such suffering was going on all around me? And the truth is that I truly didn’t think of them as human beings. “They’re not human beings, they’re kulak trash”—that’s what I heard again and again, that’s what everyone kept repeating.

— Ukraine and the Words That Lead to Mass Murder

#anne applebaum#ukraine and the words that lead to mass murder#current events#history#politics#russian politics#sociology#psychology#communism#warfare#totalitarianism#propaganda#holodomor#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#ukraine#viktor kravchenko#lev kopelev#vasily grossman#kulaks

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

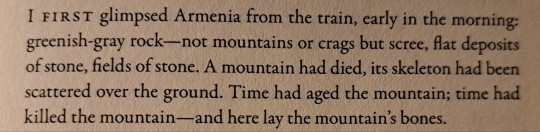

Vasily Grossman, An Armenian Sketchbook

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like most narrow-minded people, he was extraordinarily self-assured.

Stalingrad, Vasily Grossman

#stalingrad#vasily grossman#quotes#literature#books#classics#classic literature#book quotes#dark academia

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Non c’è niente di più difficile che dire addio a una casa in cui hai sofferto.

Vasily Grossman

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't want you to be young and beautiful. I only want one thing. I want you to be kind-hearted - and not just towards cats and dogs.

vasily grossman, life and fate

#self care is reading russian classics#books#one of my favorite things#love books#writers#i love reading#i am a writer#readers on tumblr#connecting with readers#life and fate#vasily grossman#ww2 history#ww2#stalin#marxism leninism#writing#writers on tumblr#love of my life#reader#currently reading#i'm reading it right now#reading#long reads#books and reading#to read#reader insert#read free ebooks#book readers#writers and readers#readers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Before slaughtering infected cattle, various preparatory measures have to be carried out: pits and trenches must be dug; the cattle must be transported to where they are to be slaughtered; instructions must be issued to qualified workers.

If the local population helps the authorities to convey the infected cattle to the slaughtering points and to catch beasts that have run away, they do this not out of hatred of cows and calves, but out of an instinct for self-preservation.

Similarly, when people are to be slaughtered en masse, the local population is not immediately gripped by a bloodthirsty hatred of the old men, women and children who are to be destroyed. It is necessary to prepare the population by means of a special campaign. And in this case it is not enough to rely merely on the instinct for self-preservation; it is necessary to stir up feelings of real hatred and revulsion.

It was in such an atmosphere that the Germans carried out the extermination of the Ukrainian and Byelorussian Jews. And at an earlier date, in the same regions, Stalin himself had mobilized the fury of the masses, whipping it up to the point of frenzy during the campaigns to liquidate the kulaks as a class and during the extermination of Trotskyist-Bukharinite degenerates and saboteurs.

Experience showed that such campaigns make the majority of the population obey every order of the authorities as though hypnotized. There is a particular minority which actively helps to create the atmosphere of these campaigns: ideological fanatics; people who take a bloodthirsty delight in the misfortunes of others; and people who want to settle personal scores, to steal a man's belongings or take over his flat or job. Most people, however, are horrified at mass murder, but they hide this not only from their families, but even from themselves. These are the people who filled the meeting-halls during the campaigns of destruction; however vast these halls or frequent these meetings, very few of them ever disturbed the quiet unanimity of the voting. Still fewer, of course, rather than turning away from the beseeching gaze of a dog suspected of rabies, dared to take the dog in and allow it to live in their houses. Nevertheless, this did happen.

The first half of the twentieth century may be seen as a time of great scientific discoveries, revolutions, immense social transformations and two World Wars. It will go down in history, however, as the time when - in accordance with philosophies of race and society - whole sections of the Jewish population were exterminated. Understandably, the present day remains discreetly silent about this.

One of the most astonishing human traits that came to light at this time was obedience. There were cases of huge queues being formed by people awaiting execution - and it was the victims themselves who regulated the movement of these queues. There were hot summer days when people had to wait from early morning until late at night; some mothers prudently provided themselves with bread and bottles of water for their children. Millions of innocent people, knowing that they would soon be arrested, said goodbye to their nearest and dearest in advance and prepared little bundles containing spare underwear and a towel. Millions of people lived in vast camps that had not only been built by prisoners but were even guarded by them.

And it wasn't merely tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands, but hundreds of millions of people who were the obedient witnesses of this slaughter of the innocent. Nor were they merely obedient witnesses: when ordered to, they gave their support to this slaughter, voting in favour of it amid a hubbub of voices. There was something unexpected in the degree of their obedience.

There was, of course, resistance; there were acts of courage and determination on the part of those who had been condemned, there were uprisings; there were men who risked their own lives and the lives of their families in order to save the life of a stranger. But the obedience of the vast mass of people is undeniable.

What does this tell us? That a new trait has suddenly appeared in human nature? No, this obedience bears witness to a new force acting on human beings. The extreme violence of totalitarian social systems proved able to paralyse the human spirit throughout whole continents.

A man who has placed his soul in the service of Fascism declares an evil and dangerous slavery to be the only true good. Rather than overtly renouncing human feelings, he declares the crimes committed by Fascism to be the highest form of humanitarianism; he agrees to divide people up into the pure and worthy and the impure and unworthy.

The instinct for self-preservation is supported by the hypnotic power of world ideologies. These call people to carry out any sacrifice, to accept any means, in order to achieve the highest of ends: the future greatness of the motherland, world progress, the future happiness of mankind, of a nation, of a class.

One more force co-operated with the life-instinct and the power of great ideologies: terror at the limitless violence of a powerful State, terror at the way murder had become the basis of everyday life.

The violence of a totalitarian State is so great as to be no longer a means to an end; it becomes an object of mystical worship and adoration. How else can one explain the way certain intelligent, thinking Jews declared the slaughter of the Jews to be necessary for the happiness of mankind? That in view of this they were ready to take their own children to be executed - ready to carry out the sacrifice once demanded of Abraham? How else can one explain the case of a gifted, intelligent poet, himself a peasant by birth, who with sincere conviction wrote a long poem celebrating the terrible years of suffering undergone by the peasantry, years that had swallowed up his own father, an honest and simple-hearted labourer?

Another fact that allowed Fascism to gain power over men was their blindness. A man cannot believe that he is about to be destroyed. The optimism of people standing on the edge of the grave is astounding. The soil of hope - a hope that was senseless and sometimes dishonest and despicable - gave birth to a pathetic obedience that was often equally despicable.

The Warsaw Rising, the uprisings at Treblinka and Sobibor, the various mutinies of brenners, were all born of hopelessness. But then utter hopelessness engenders not only resistance and uprisings but also a yearning to be executed as quickly as possible.

People argued over their place in the queue beside the blood-filled ditch while a mad, almost exultant voice shouted out: 'Don't be afraid, Jews. It's nothing terrible. Five minutes and it will all be over.'

Everything gave rise to obedience - both hope and hopelessness.

It is important to consider what a man must have suffered and endured in order to feel glad at the thought of his impending execution. It is especially important to consider this if one is inclined to moralize, to reproach the victims for their lack of resistance in conditions of which one has little conception.

Having established man's readiness to obey when confronted with limitless violence, we must go on to draw one further conclusion that is of importance for an understanding of man and his future.

Does human nature undergo a true change in the cauldron of totalitarian violence? Does man lose his innate yearning for freedom? The fate of both man and the totalitarian State depends on the answer to this question. If human nature does change, then the eternal and world-wide triumph of the dictatorial State is assured; if his yearning for freedom remains constant, then the totalitarian State is doomed.

The great Rising in the Warsaw ghetto, the uprisings in Treblinka and Sobibor; the vast partisan movement that flared up in dozens of countries enslaved by Hitler; the uprisings in Berlin in 1953, in Hungary in 1956, and in the labour-camps of Siberia and the Far East after Stalin's death; the riots at this time in Poland, the number of factories that went on strike and the student protests that broke out in many cities against the suppression of freedom of thought; all these bear witness to the indestructibility of man's yearning for freedom. This yearning was suppressed but it continued to exist. Man's fate may make him a slave, but his nature remains unchanged.

Man's innate yearning for freedom can be suppressed but never destroyed. Totalitarianism cannot renounce violence. If it does, it perishes. Eternal, ceaseless violence, overt or covert, is the basis of totalitarianism. Man does not renounce freedom voluntarily. This conclusion holds out hope for our time, hope for the future.” (p. 213 - 216)

The Moloch of Totalitarianism in the Levashovo Wasteland, St. Petersburg, Russia

#grossman#vasily grossman#life and fate#totalitarianism#hitler#stalin#wwiii#world war 2#obediance#hoplessness#holocaust#holodomor#nazi#communism#fascism#russia#germany#russian lit#russian literature#soviet literature#books#bookshelf#library#book lover#moloch

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you want to read a meditation on the evils of militarism, ideological fanaticism and authoritarianism written by a Jewish guy from Ukraine, may I recommend Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman? I basically recommended this book to everyone even before it once again became Very Topical but horrifyingly it gets more topical with each passing year. Like I joked not joked about a Vasily Grossman book club in 2016 and here we are. I have literally told multiple people at wedding receptions that they need to read this book, because I am fun at parties.

#vasily grossman#life and fate#russian literature#ukrainian literature#jewish literature#antifascism#dissident literature#socialist realism#the holocaust#wwii

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The twentieth century is a critical and dangerous time for humanity. It is time for intelligent people to renounce, once and for all the thoughtless and sentimental habit of admiring a criminal if the scope of his criminality is vast enough, of admiring an arsonist if he sets fire not to a village hut but to capital cities, of tolerating a demagogue if he deceives not just an uneducated lad from a village but entire nations, of pardoning a murderer because he has killed not one individual but millions.

Such criminals must be destroyed like rabid wolves. We must remember them only with disgust and burning hatred. We must expose their darkness to the light of day.

And if the forces of darkness engender new Hitlers, playing on people's basest and most backward instincts in order to further new criminal designs against humanity, let no one see in them any trait of grandeur or heroism.

Vasily Grossman, Stalingrad

#This book has taken me like eight months so far because it's so tremendous#Almost every page has some incredible insight into the human experience or history or politics#so I've had to go through it slowly to digest it all#q#vasily grossman#stalingrad

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your first minutes on the streets of an unfamiliar city are always special: what happens in later months or years can never supplant them. These minutes are filled with the visual equivalent of nuclear energy, a kind of nuclear power of attention. With penetrating insight and an all-pervading excitement, you absorb a huge universe – houses, trees, faces of passersby, signs, squares, smells, dust, cats and dogs, the color of the sky. During these minutes, like an omnipresent God, you bring a new world into being: you create, you build inside yourself a whole city with all its streets and squares, with its courtyards and patios, with its sparrows, with its thousands of years of history, with its food shops and its shops for manufactured goods, with its opera house and its canteens. This city that suddenly arises from nonbeing is a special city; it differs from the city that exists in reality – it is the city of a particular person.

Vasily Grossman, An Armenian Sketchbook

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who can I ask? Who's going to answer? Who can turn this blade away from my heart?

Stalingrad, Vasily Grossman

#stalingrad#vasily grossman#russian literature#quotes#literature#books#classics#classic literature#book quotes#dark academia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today’s new release is paired with some soul-shaking books about war.

#my reading life#new release#vasily grossman#curzio malaparte#wwii#fiction#literature#armenian genocide

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vasily Grossman's The People Immortal (Book acquired, 30 Aug. 2022)

Vasily Grossman’s The People Immortal (Book acquired, 30 Aug. 2022)

A copy of by Vasily Grossman’s 1943 novel The People Immortal arrived at Biblioklept World Headquarters. It’s a new translation by Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler, available next month from NYRB.

(It’s also a reminder to pick up the copy of Grossman’s massive novel Life and Fate that’s been staring me down for years).

NYRB’s blurb:

Vasily Grossman wrote three novels about the Second World…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In the chaos, amidst the roar of five-ton trucks, were the outlines of the future streets of a new Moscow. Ivan Grigoriyevich wandered in the emerging city, where as yet there were no roadways or sidewalks. Where people scuffled to their homes along paths that wove around the heaps of garbage. Everywhere the buildings bore all of the same signs: 'Meat' and 'Hair salon.' In the twilight the upright signs for 'Meat' burned with a red flame, the signs for 'Hair salon' shone with a piercing green. Those signs, which appeared with the first residents, seemed to reveal the fleshly nature of man.

Vasily Grossman, Everything Flows (Все течет)

В хаосе, среди рева пятитонок, угадывались будущие улицы новой Москвы. Иван Григорьевич бродил в возникающем городе, где не было еще мостовых и тротуаров. Где люди добирались к своим домам по тропинкам, юлящим среди груд мусора. Повсюду на домах имелись одни и те же вывески: "Мясо" и "Парикмахерская". В сумерках вертикальные вывески "Мясо" горели красным огнем, вывески "Парикмахерская" светились пронзительной зеленью.

Эти вывески, возникшие с первыми жильцами, как бы раскрывали плотскую суть человека.

#vasily grossman#everything flows#все течет#books#quote#allie reads#this quote isn't about that#but i have encountered almost no one#who is as horrifyingly brutally and empathetically good#at showing the effects of totalitarianism on the human psyche#he writes people who are almost broken#and who have flashes of humanity#and those matter!#but the sheer abject shame and fear that they feel so much of the time#can't be escaped#and it's the ones who do have humanity who feel the sham#shame#there's also those who don't#he's just very good#moscow#and apparently translates if need be#<- forgot the tag

1 note

·

View note