#the faerie queene

Text

Una and the Lion (from Spenser's 'The Faerie Queene'), circa 1860

William Bell Scott

#oil on canvas#Una and the Lion#William Bell Scott#1860s#The Faerie Queene#literature#character#art#art history#scottish art

626 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Tumblr! You get to see this first because I do not want to deal with the horrors of Instagram cropping.

I made this comic for a creative writing assignment, which was to do 4 pages with absolutely no dialogue. The concept probably came from a mix of The Faerie Queene (which I’ve been reading) and Tears of the Kingdom (which I’ve been playing a lot of.) It took way longer than intended, but here’s the result!

#comic#original comic#medieval#the faerie queene#i dont really have any good tags for this tbh#my silly knight guy

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Faerie Queen by Edmund Spenser

1953

Artist : John Austen

260 notes

·

View notes

Video

The Ancient Magus’ Bride | 魔法使いの嫁 | Mahoutsukai no Yome

#Mahoutsukai no Yome#The Ancient Magus' Bride#Mahoyome#The Ancient Magus Bride#Kore Yamazaki#Mahou Tsukai no Yome#魔法使いの嫁#Oberon#Titania#The Faerie Queene#The Faerie King#Spriggan#Elias Ainsworth#Yamazaki Kore#Anime#Video

226 notes

·

View notes

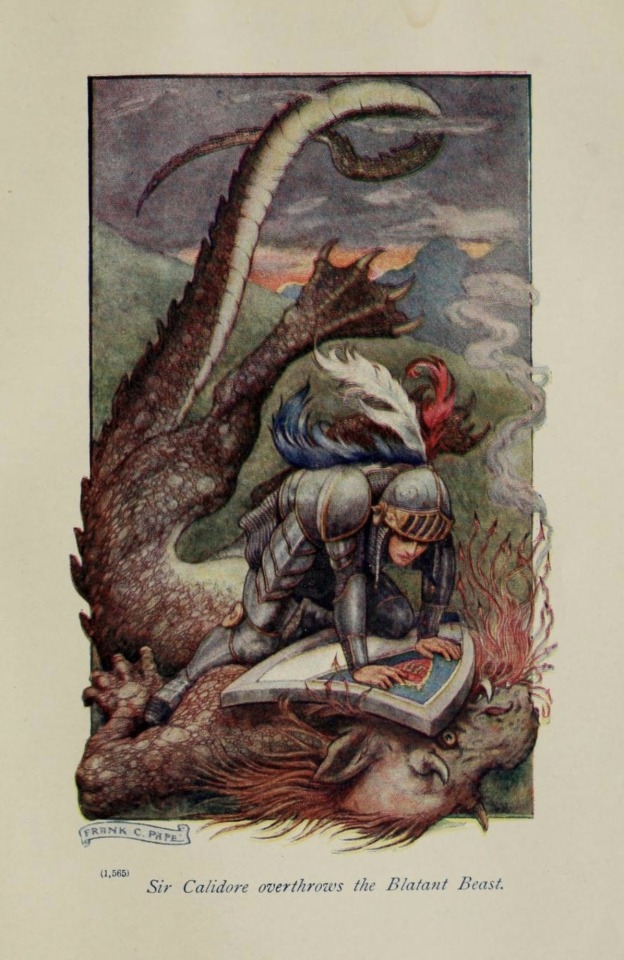

Text

#sir calidore#knight#beast#art#the faerie queene#edmund spenser#english#poem#allegorical#allegory#knights#chivalry#adventure#quest#history#mythology#england#knighthood#chivalric romance#medieval#magical#middle ages#armour#knight errant#beasts#monsters#dragons

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Then came old January, wrapped well

In many weeds to keep the cold away;

Yet did he quake and quiver like to quell,

And blowe his nayles to warme them if he may:

For they were numbd with holding all the day

An hatchet keene, with which he felled wood,

And from the trees did lop the needlesse spray:

Upon an huge great earth-pot steane he stood,

From whose wide mouth there flowed forth the Romane floud.

~ Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queen

#edmund spenser#the faerie queene#quotes#british literature#british lit#english literature#english lit#british author#english author#british poetry#english poetry#poetry#classic literature#classic lit quotes#classic poetry#classic literature quotes#poetry quotes#elizabethan era#elizabethan poetry#16th century literature#16th century poetry#16th century#january#january quotes#seasonal poetry#seasonal quotes#e

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

For my last Helluva Boss celebration I made a whole series of posts about the Nine Circles of Hell in Dante’s Inferno (see a few reblogs below). For my new Helluva Boss celebration, I wanted to take a look at various literary depictions of the seven deadly sins as personifications. This post was originally prepared to celebrate Mammon’s Magnificent Musical, but given the release of “Look My Way”, it will still work even though I post it quite late.

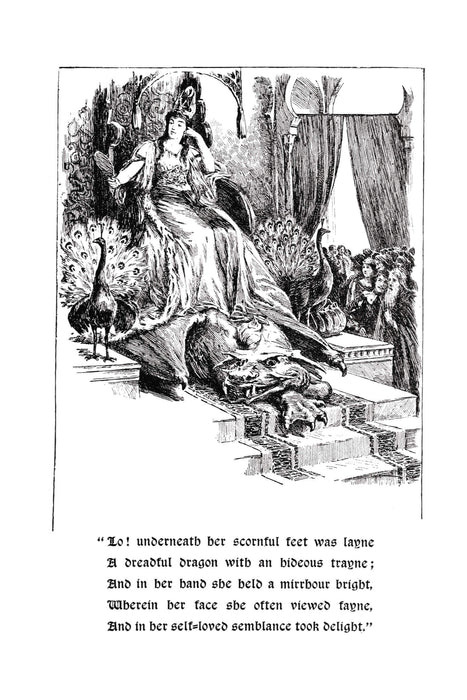

When it comes to looking at classic embodiments of the deadly sins, I want to begin with one of the “modern, non-Antique epics” that marked the history of literature, like the Orlando Furioso or Paradise Lost. I want to take a look today at Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, the great British epic of the 16th-17th centuries, a medieval-romance-like set of stories depicting the adventures of allegorical knights fighting allegorical monsters. The poem is filled with characters embodying various vices and virtues – the very heroes of the story are a set of knights acting as the champions of the various Christian virtues (the Redcross Knight is the champion of Holiness, as an avatar of saint Georges the patron of England ; Guyon, first of the Faerie Queen’s knights, is the champion of Temperance ; Britomart, the woman-knight, is the champion of Chastity, Artegal is the champion of Justice, etc, etc.) ; while the villains are very unsubtle in their nature (a female demon named Ate is assisted by Duessa – deceit – and spreads discord among friends ; a lonely man named Despair convinces the hero to kill himself, etc, etc.)

But today I want to focus on a specific episode of the epic’s first book. An episode usually known as the “House of Pride” and where the main hero (the Red-Cross Knight, the protagonist of the epic’s first book) encounters the embodiments of the seven deadly sins.

For a bit of context, the depiction of the seven deadly sins here is meant to parallel and counter-exemplify two other parts of the poem. On one side, the House of Pride is later opposed by the “House of Holiness” where the Redcross-Knight is helped, healed and cared for by a lady named Caelia, who has three daughters, Fidelia, Speranza and Charissa. This is all supposed to embody the Christian concept of the “three theological virtues”, the three virtues that come from God – Faith, Hope and Charity, born of “The Sky/The Heavens”. On the other side, the House of Pride and its queen are meant to mirror the titular Faerie Queene of the poem, Queen Gloriana – a very flattering fictional portrait of Elisabeth the First, but also the embodiment of “Glory” as her name says. Aka the positive, well-deserved and non-sinful twin of the viceful Pride – here embodied by the dreaded lady Lucifera.

Lady Lucifera is, it comes to no surprise, the owner and ruler of the House of Pride. The other deadly are all male, and act as both her counselors and her court wizards (being called alternatively “sage counselors” and “old wizards”). This all fits within the accepted idea that pride is not just the most dangerous and “important” of the seven deadly sins, it is also their root and their “superior”. In many metaphors, it is translated by pride being seen as the “king” or “mother” of the other deadly sins: in the Faerie Queene, she is their ruler, their queen. But, in an interesting twist, Spenser establishes a true relationship of co-dependency between the sins: the other six might be Pride’s servants… but they are still her advisors, counselors, and they are later literally seen pulling her chariot, clearly showing that while Pride leads them and gives them order, without the other sins, Pride would literally go nowhere.

But let us return to Lucifera before looking at her “old wizards”. Lucifera is obviously named after Lucifer, the figure of the fallen angel that became a devil, if not THE devil, for thinking of himself as better than humanity, and ultimately rebelling against God and trying to cast Him down. Lucifer is commonly seen as THE demon embodying pride – and Spenser also loves to throw various references to the mythological origins of Lucifer, as his name meaning “light-bearer” is due to how, in Greco-Roman mythology, Lucifer was the spirit of the Morning Star, announcing dawn. Here, Lucifera is constantly described as “bright” or as “shining”, and when she leaves her castle on her chariot, she is explicitly compared to “Aurora in her purple pall” coming out from the east of the world – aka, Eos, the Greek goddess of Dawn. Not only that, but the excessive “shine” and almost blinding light that is emitted by the lady of Pride is also put in parallel to the light of Phaeton. Remember Phaeton? The human who thought he could drive the chariot of Helios/Phoebus, the god of the sun? And who in the process almost destroyed the earth, and had to be killed by being thrown out of the sky with a fire-bolt? Another example of pride punished, and one explicitly meant to mirror Lucifer’s own fall from Heaven. But this woman is not a fallen angel, no: rather she is described as an actual goddess, “daughter of grisly Pluto and sad Proserpina, queen of Hell”. So, she is a deity, but part of the grim, sinister, chthonian gods of death, and she is a princess true, but a princess of the Underworld (aka Hell, since the two are treated as one and the same, and Pluto/Proserpina gained demonic connotations by this time). Already we have here a Pride that is explicitly rooted in death and the afterlife, in darkness, oblivion and rot – we are in the same logic as the “vanities” and the “memento mori”, the lesson that ultimately nothing is eternal, and vanity is a folly because all beautiful faces will end up as a skull.

However Spenser cleverly also prepares us, by this mythological references, to the presentation of what Lucifera’s behavior and crimes are. Because Lucifera is not one of those “vain fools” who think of themselves as beautiful when they are not – on the contrary. Lucifera is immensely beautiful, and even if it wasn’t for her beauty, she sits in an array of immense luxury, wearing the most refined and outstanding clothes and dazzling jewelries you can imagine. Lucifera is a truly admirable figure – quite literally since it is said that knights and lords from all four corners of the world come to her palace to admire her. The twist lies in HOW she behaves and acts. Because Lucifera does not care for her many guests, hosts and admirers, treating them with only scorn and disdain – breaking the basic law of hospitality and the rules of courtly behavior by her immense selfishness. Her many admirers and courtiers are said to constantly make themselves prettier, shinier, more noble and more appealing, attracting, charming, all in the hope of pleasing her – but she does not care at all for all their effort, and probably does not even notice them. When great knights and lords offer themselves to her, she does thank them… But in a disdainful way, and with very brief words, and only because they promised to spread words of her fame and glory and beauty. She is said to hate everything that is “low” (which is why, out of allegorical joke, she always sits on a high throne and makes sure she is above everyone else) – but given she thinks of everything outside of herself as “low”, she ends up hating everybody. She only looks at two things – either her hand-mirror (because her own reflection brings her “great delight and joy”), either the heavens. Again, due to a hatred of “anything low” and a desire to only have the highest, tallest and grandest things – but also because she rejects her own chthonian, underworld-roots. Indeed, while she is the daughter of Pluto and Proserpina (Hades and Persephone), she rather places herself on the same level (and sometimes above) as Jove (aka Zeus). Zeus/Jove, Eos/Aurora, and Phaeton: Lucifera dreams and fashions herself after the celestial beings of the sky and of light, when in truth she is a chthonian entity of death, earth and darkness.

Not only that, but she fashions herself a queen when she is not… Remember when I said that she was the daughter of Pluto and Proserpina, king and queen of Hell? It makes her a princess alright… An eternal princess, since her parents are immortal gods and thus will never pass any crown onto her. But Lucifera, devoured by ambition and arrogance, HAD to be a queen. So what did she do? She went onto earth and there obtained a crown… “with wrong and tyranny”. She literally stole and took by force a crown that was not hers, usurped a territory and made herself the sole and absolute ruler of it. Not only is she a false ruler with no actual right to sit on the throne, but she even went as far as to usurp a domain that had no relationship to her parents, lineage or world – daughter of the principles of death and the underworld, she decided to make herself a queen of the livings onto earth’s surface… Even worse, she is not a good queen, because according to Spenser, beyond being a “tyrant”, she does not rule with “laws” but with “policies”. And in the language of the time, “policies” are here to mean “cunning and crafty devices”. She is a tyrant who not only brutally seized a crown and usurped a thrown, but on top of that establishes her rule through cunning, trickery and unlawful behavior (it is not surprise that here, her counsel is explicitly described as being formed of “six wizards” – they are not men of the law, they are not men of politics or courtiers, they are not men of war or economy, they are wizards and sorcerers, forming a government of magic tricks and deceiving enchantments). As a visual touch to denote the evilness and danger inherent to her superb appearance: at her feet, lies a dragon, that forms a “hideous trayne” to her glorious, shining, sparkling and luxurious dress.

[There is also a “gentle husher” that works for queen Lucifera, and notably always prepare her passage before she goes anywhere, obviously called Vanity, but there isn’t much to say here since he is a one-line reference]

Just as important as Lucifera herself is the palace she lives within and rules from: the House of Pride, which is the architectural twin of Lucifera, and the inanimate embodiment of the sin of Pride (and of all sins and vices in general). The House of Pride is described as a great and grandly palace, all filled with luxuries, all shining and bright… It is covered in gold! Or rather… it is foiled in golds. The walls of the palace were covered in a thin layer of gold to hide the actual material in which the castle was made – a very rough and very poor material. Great and high walls that impress everyone by their size – but which are made of bricks without mortar, and are thus very easy to destroy. The palace is thought of as grandiose because it has many hallways and numerous towers and a LOT of rooms – but its foundations are actually very weak, since the castle was built… on a “sandy hill”. A hill of sand that is very unstable and regularly collapses – threatening the entire palace, which “shakes with every strong wind”. Finally, while everybody amasses themselves and awaits by the front of the palace, its backrooms and back-parts, those not seen from the path leading to the House, are noted to all be old ruins… but “painted cunningly” to hide their own decrepitude. You could say that Vanity, the “gentle husher”, is an extension of the House of Pride itself – since it all depicts the sin of vanity itself. A great care of appearances and an obsession with beauty forcing one to hide the truth, to fight foolishly and senselessly the effects of time or one’s true nature, all to create a deceptive idea of an ideal self that never truly existed. More generally, the House of Pride represents the very trap that is a sin, or a vice in general – it is the House of Evil if you want. It is grandiose, immense, beautiful, shining, with all sorts of riches and treasures… But it is built out of poor materials, it offers no real protection or comfort, its riches are only skin-deep (or wallpaper-deep), and it is overall an unstable structure that is already a half-ruin. The danger of the House is made even more explicit by the large road that leads to it – a large pathway that many people take to go to the House, but that very few people use to leave… And when Lucifera leaves her castle on her chariot, and goes down the road, the protagonist can suddenly see what paves the way and that he missed before – the things the wheels of Lucifera’s chariot gleefully crushes. The bones and skulls of all those that “went astray” and went by the House of Pride…

The dual of nature of the House and Lucifera (who represent the two sides of pride – Lucifera is scorn, disdain, ambition and arrogance, while the House is vanity and vainglory, Lucifera is the “superbia” pride while the House is the “vanagloria” pride) is even reflected in a sort of bizarre “competition” that is sets between the two. Indeed, when we see Lucifera sitting on her throne… The poet sarcastically describes how both the throne and the queen on it shine brightly, and they glitter and sparkle so much as if “the blaze of the glorious throne” and the blaze of the queen herself tried to “dim each other”. Pride will always be the most envious and jealous of itself…

After spending some times inside the House, we follow Lucifera as she leaves her castle and takes her coach by the road. The coach is just as luxurious and glittering and blazing as the House and the queen, since it is all of “gold and garlands”. And again, we have explicit mythological comparisons: Lucifera, with all those flowers around her, make her look like “Flora in her prime”… But she actually tries to imitate and surpass another goddess – Juno, aka Hera, queen of the gods and the heavens. The parallel is even reinforced by the presence of peacock feathers on the chariot. “Argus’ eyes”, on one side, the mythological emblems of Juno/Hera… But also the common symbol of vanity and pride, the peacock being considered THE bird of this sin.

And if it was not clear enough that this was an EVIL queen, the coachman of Lucifera, the one holding the whip… Is said to be none other than Satan himself. Aka THE actual Christian Devil, THE Great Fiend himself who gleefully leads queen Lucifera wherever she wants to go. And whips the six other sins to ride faster… Because, as I said before – Lucifera’s chariot is not pulled by horses… But by her six “sage counsellors/old wizards”, aka the other deadly sins. However, since this post is already getting quite long, I’ll keep them for another time.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

edmund spenser really said, i'm gonna make redcrosse knight the himboest of all the himbos, and I respect that.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

It's not Arthurian, but have you ever read The Fairy Queene? If so would you share your thoughts?

No, but I've been meaning to. So many things to read, so little time!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

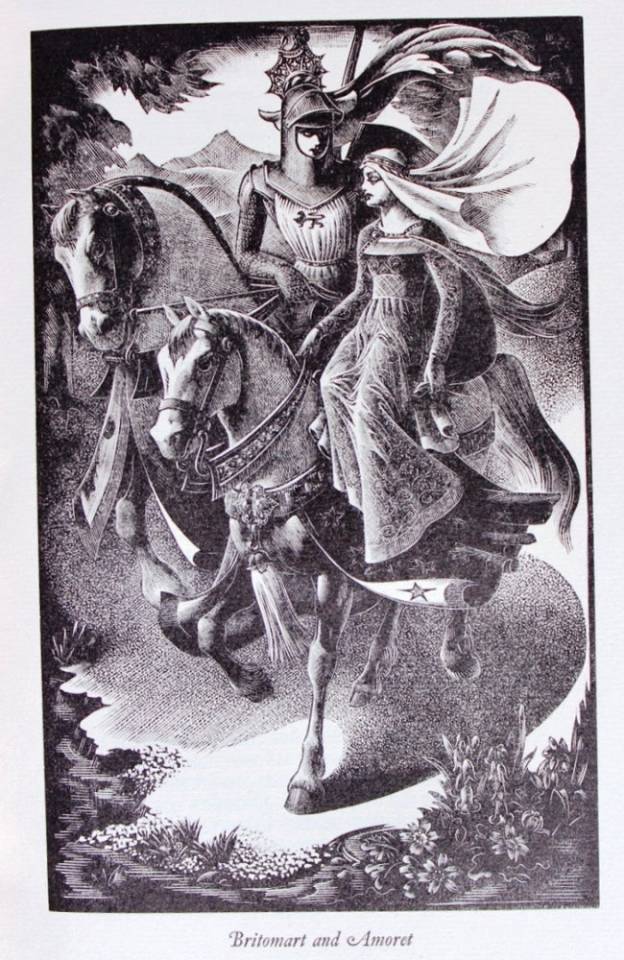

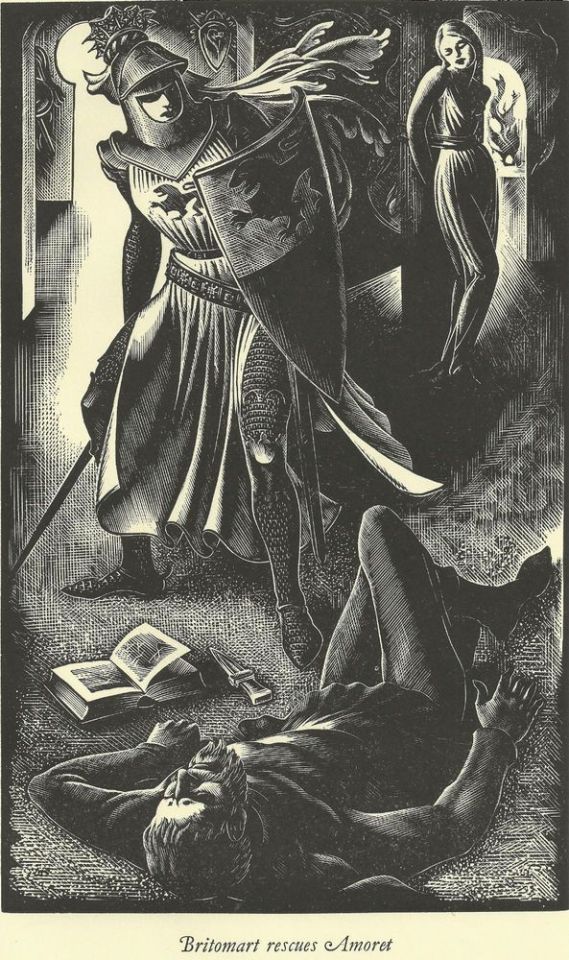

once again britomart and amoret posting I love them so dearly .♥️guys sometimes elizabethan epic poem characters are really lesbian

#vintage#aesthetic#vintage art#vintage aesthetic#art#britomart and amoret#the faerie queene#the faerie queene 1590#vintage lesbians#sword girls#sword lesbians#!!!!!!#epic poems

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHECK out this cool project!

A text-faithful prose rendering of the 1590s epic poem (The Faerie Queene) by Rebecca K. Reynolds, with nearly eighty new illustrations by Justin Gerard.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

This reminded me of Rhian.

#school for good and evil#fall of the school for good and evil#rhian#rhian mistral#sge#sfgae#the school for good and evil#tsfgae#fotsge#fotsfgae#my post#the faerie queene#edmund spenser#the blue dragonfire

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is an essay about poetry, and the crusades, among other things. The ideal of the Christian Knight is a centerpiece of Spenser's Psychomachia.

Zach Reynolds

Dr. Erickson

July 13, 2011

English 4120

Pyrrhochles’ Implacable Fyre

The embodiment of irascibility, Pyrrhochles appears in Book II of The Faerie Queene acting out his demonic heritage in ways so contrary to reason and temperance that he appears as a wholly unsympathetic character to the reader. Approaching Guyon on his “bloody red” steed, which “[foams] yre,” and wearing armor that, glinting in the sunlight, “round about him [throws] forth sparkling fire,” Pyrrhochles truly seems to be a vision out of Hell sent to torment the good knight Guyon (II.v.2). Yet when meeting his demise at the hands of Arthur after his third defeat in combat, the narrator portrays Pyrrhochles in more tragic light by depicting him “as one that loathed life, and yet despysd to dye” “for vile disdaine and rancour . . . did gnaw / his hart in twaine with sad melancholy” (II.viii.50). As Arthur embodies magnanimity, the mercy that he offers Pyrrhochles can be interpreted as the divine grace or saving grace that Christianity offers to sinners through the body of the crucified redeemer; that the narrator says Pyrrhochles “so wilfully refused grace” after naming him “the Pagan” supports this interpretation (II.viii.52). But besides making a religious commentary, the depiction of Pyrrhochles’ death reveals the fell knight’s ambivalence towards life by contrasting his refusal for mercy from Arthur with his cry to Guyon for mercy after his first failed combat in the book. Pyrrhochles’ ambivalence towards life and his decision to die finally “in despight of life” places him in a similar position to the Redcrosse Knight when he attempts suicide in the cave of Despayre – the Redcrosse Knight would have likewise died “in despight of life” if Una were not there to stop “diuelish thoughts” from “[dismaying his] constant spright”(II.viii.52, I.ix.53). Thus, by reading Pyrrhochles’ death as a suicide, his character comes to embody more than merely irascible behavior, and his irascibility seems to derive from the more pensive aspect of despair, complicating the appearance of Pyrrhochles as an oversimplified villain and raising the question of what motivates his fiery demeanor.

Pyrrhochles’ defeat by Arthur does not signify his first attempt at suicide; in fact Pyrrhochles first attempts to kill himself by “[drowning] him selfe for fell despight” in Idle Lake and must be rescued by his attendant Atin and Archimago (II.vi.43). In the dialogue that ensues in this passage between Pyrrhochles, Atin, and Archimago, Pyrrhochles expresses how the “implacable fyre” that “nothing but death can doe [him] to respire” “torment[s]” and “consume[s]” him from “within [his] secrete bowelles” (II.vi.44, 49). While identifying the “implacable fyre” that burns Pyrrhochles as a kind of physical poison sustained from wounds he received in his fight with Furor, the allegorical implications clearly suggest that Pyrrhochles’ outwardly fiendish nature derives from an inward turmoil that “nought can quench,” i.e., some emotional trauma tormenting Pyrrhochles causes him to be so abrasive (44). The emblem on his shield, “Burnt I doe burne,” reinforces this interpretation. That fire characterizes the nature of Pyrrhochles’ trauma suggests that his injury is akin to a brand, and as such, his trauma is irresolvable, permanent, and as the source of the flames which burn him inwardly, drives him to perpetual acts of self-destruction that ultimately climax in suicide.

Additionally, Pyrrhochles engages in actions that correspond to the Kuebler-Ross model of grief. His immediate reaction to defeat in his fight with Guyon combines denial and bargaining when he cries, “Mercy, doe me not dye, / Ne deeme thy force by fortunes doome vniust, / That hath (maugre her spight) thus low me laid in dust” (II.v.12). Here, Pyrrhochles insists that fortune, or chance, caused him to lose the battle by unjustly favoring Guyon while he yet pleads with the knight of temperance for his life. Pyrrhochles follows his defeat by unbinding Furor and Occasion, and in fighting Furor he sustains the injuries that drive him into his first suicidal frenzy. Thus, Pyrrhochles observes the second stage of grief, anger, in his fight with Furor, followed by the fourth stage of grief, depression, when “to the flood he came” and “without stop or stay he fiersly lept, / And deepe him selfe beducked in the same” (II.vi.42). Pyrrhochles’ claim that “nothing but death can doe [him] respight” supports the notion that his state when he plunges into Lake Idle is overwhelmingly depression rather than anger (44). Furthermore, the reference to Lake Idle as “the flood” alludes to the Palmer’s prior assertion to Phaon that “griefe is a flood,” and since the Palmer also says “wrath is a fire,” the image of the inwardly burning Pyrrhochles diving into “the flood” suggests that Pyrrhochles attempts to soothe his anger with depression, but, in doing so, he finds himself only further embroiled in grief and so he is unable to overcome his agitated state (II.iv.35).

When Pyrrhochles next encounters Arthur and faces another defeat in battle he again expresses denial of the fact of his loss, again blaming “fortune, as it doth befall” and claiming that “not overcome [does he] dye, / But in despight of life, for death [does] call” (II.viii.52). Since he calls for death it first seems that Pyrrhochles’ denial this time is mixed with acceptance, yet by calling for death “in despight of life” Pyrrhochles never actually accepts death, but rather only embraces it as a way to deny life from further tormenting him. Thus, the narrative statement that Pyrrhochles “loathed life, and yet despised to dye” most succinctly captures the complexity of his character. Burning with unreprieved, disconsolate grief, Pyrrhochles fiendishly engages in every action contrary to temperate life that he can conceive of, effectively courting death, and forcing the magnanimous hand of Arthur to euthanize him so as to finally put an end to the infernal fires that burn him without cessation from within.

Works Cited

Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene.Ed. A.C. Hamilton, Yamashita, Suzuki, Fukuda. 2nd ed. Harlow, England: Pearson Educations Limited, 2001. Print.

#essay writing#essay#poetry#edmund spenser#the faerie queene#academics#queens#kings#knights#crusaders

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Here have I cause, in men just blame to find,

That in their proper prayse too partiall bee,

And not indifferent to woman kind,

To whom no share in armes and chevalrie

They do impart, ne maken memorie

Of their brave gestes and prowess martiall;

Scarse do they spare to one or two or three,

Rowme in their writs; yet the same writing small

Does all their deeds deface, and dims their glories all,

But by record of antique times I find,

That women wont in warres to beare most sway,

And to all great exploits them selves inclind:

Of which they still the girlond bore away,

Till envious Men fearing their rules decay,

Gan coyne straight laws to curb their liberty;

Yet sith they warlike armes have layd away:

They have exceld in artes and policy,

That now we foolish men that prayse gin eke."

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Midsummer Night’s Dream ~ Oberon & Titania | にうろん

#The Ancient Magus' Bride#Mahoutsukai no Yome#Mahoyome#The Ancient Magus Bride#Mahou Tsukai no Yome#魔法使いの嫁#Oberon#Titania#Oberon x Titania#A Midsummer Night's Dream#The Faerie Queene#The Faerie King#Kore Yamazaki#Yamazaki Kore#Anime#PixIV#Fan Art

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

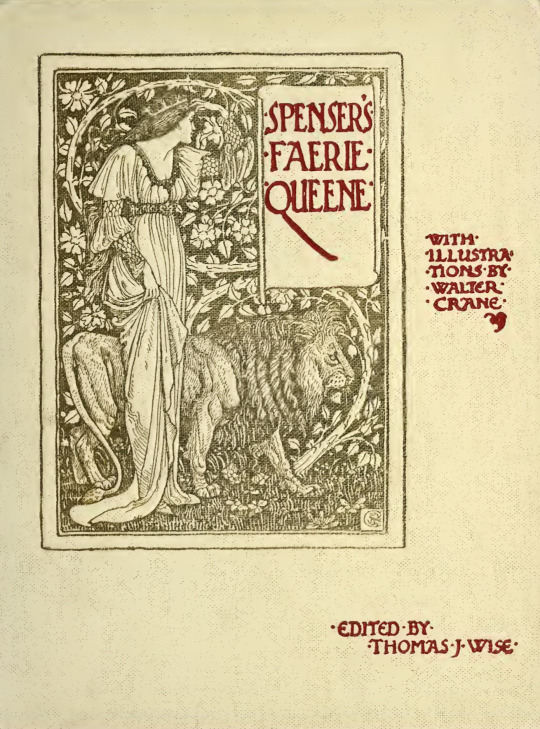

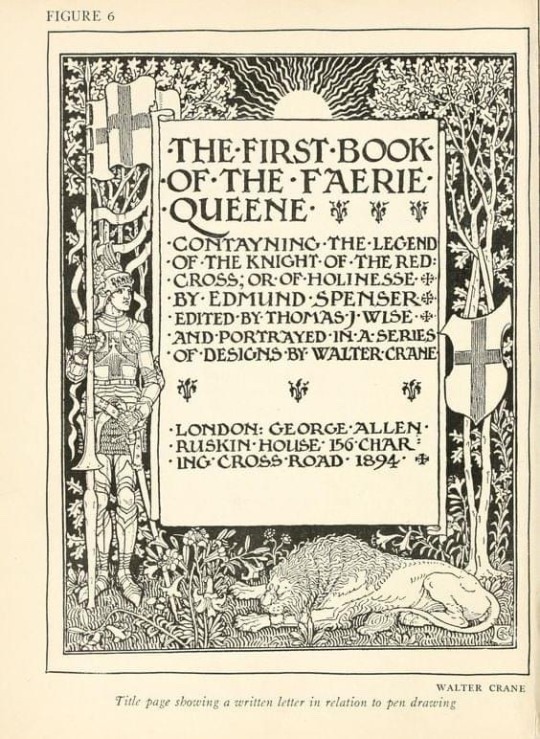

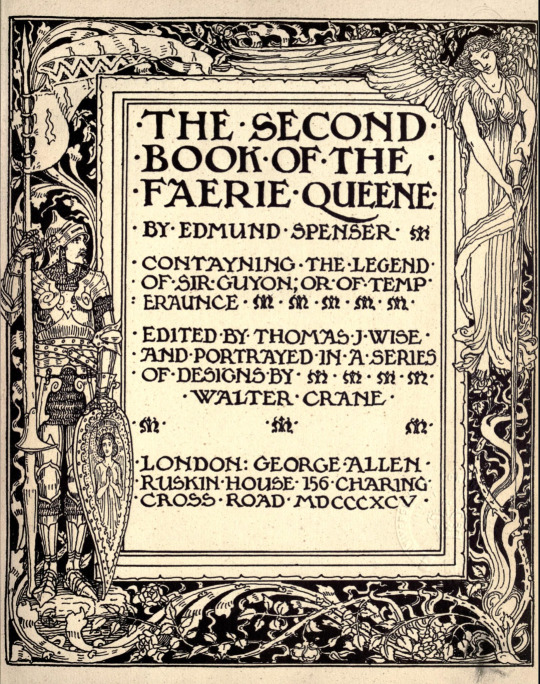

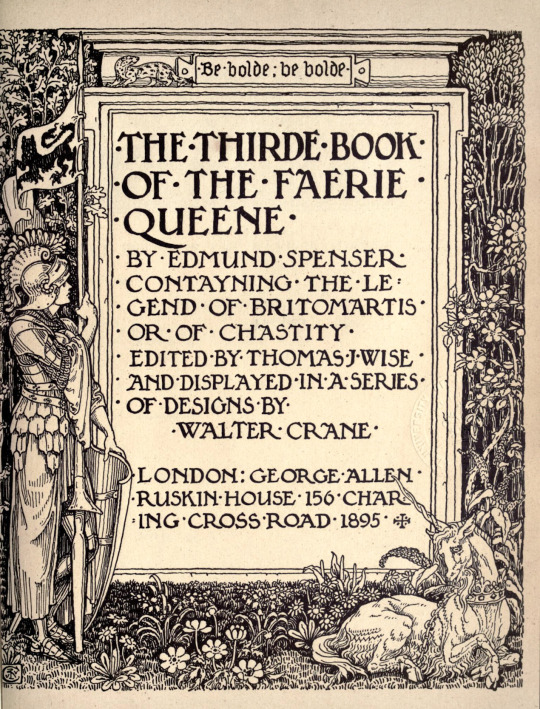

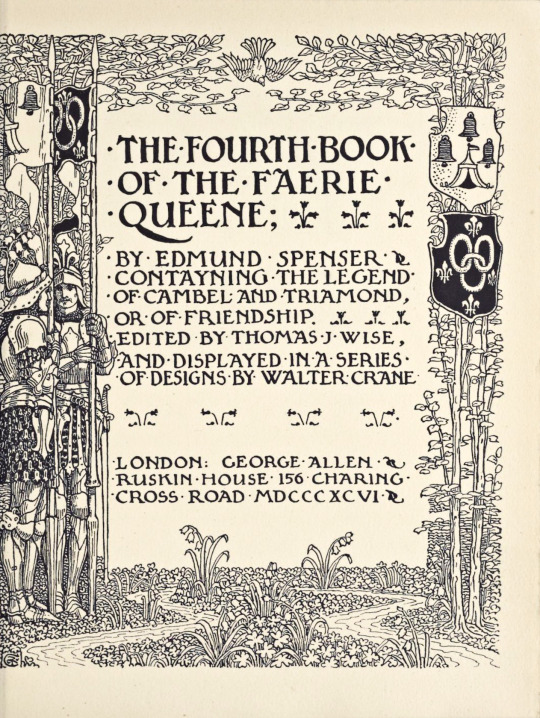

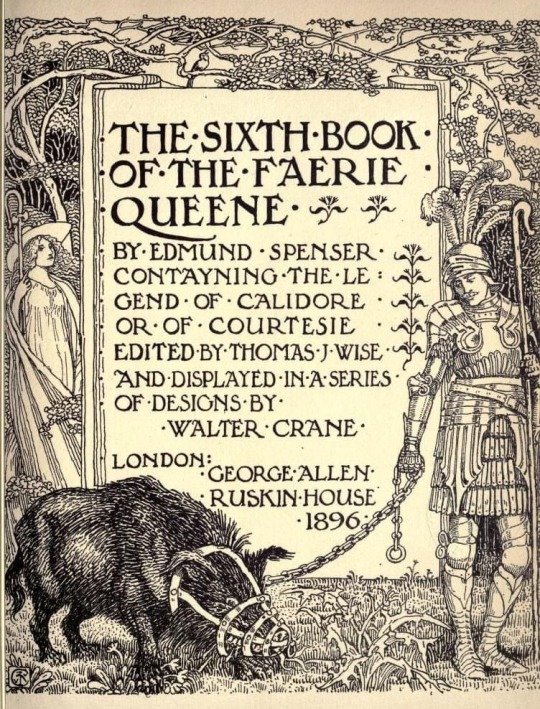

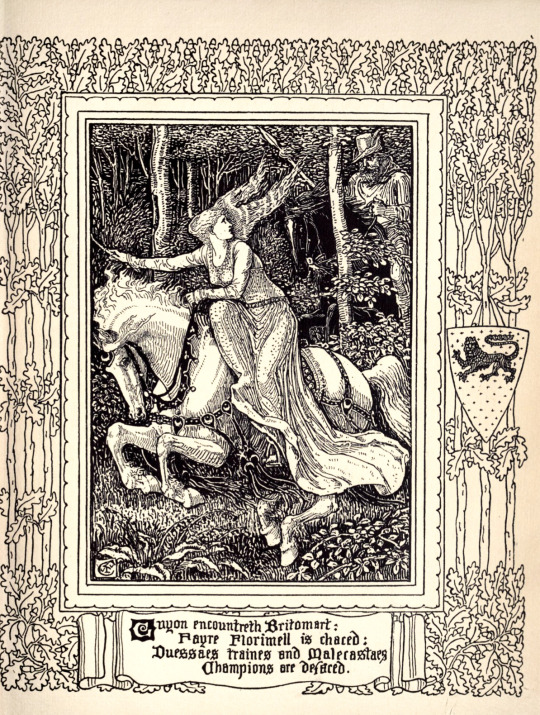

THE FAERIE QUEENE by Edmund Spenser. Edited by Thomas J. Wise. (London: George Allen, 1894 edition). Illustrated by Walter Crane.

The Faerie Queene is an epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books I–III were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 along with books IV–VI. The Faerie Queene is one of the longest poems in the English language.

The epic follows several knights as they display their different virtues. As with all allegories it, can be read on several levels. Primarily, though, it stands in praise of Queen Elizabeth I.

In a clear effort to gain court favor, Spenser presented the first three books of The Faerie Queene to Elizabeth I in 1589. There is no proof that Elizabeth ever read it, however she rewarded him with a pension of £50 a year for life. Her patronage elevated the poem to a level of success that made it Spenser's defining work.

Walter Crane’s Illustrations show an artist at the pinnacle of his career.

Source Book One

Source Book Two

Source Book Three

Source Book Four

Source Book Five

Source Book Six

#beautiful books#books books books#book blog#book cover#books#illustrated book#vintage books#edmund spenser#walter crane#the faerie queene#allegory#elizabeth i#chivalry#epic poetry

61 notes

·

View notes