#the crux of the conflict still is -- can he accept this without hating himself?

Text

was starting to hijack in the tags of that post i just reblogged but ohhhhh it is so juicy to me that the end of TKM is just part of the rising action of andrew's character arcs. and yet the way the novel leaves off, you can have so much hope in the ways its going to continue -- especially because neil proves to us on the last page that he's going to fight like hell to hold onto him whatever comes next.

it's just !!!! all andrew's deals are done. neil's big happy moment of relationship security comes from the fact that andrew didn't deny its existence lol. BUT neils correct to be happy about this, because he knows andrew is a black & white thinker, and he's entering unchartered territory! all his lil lies he uses to duct tape his sanity together are coming apart, and that break is going to be FASCINATING. i doubt it'll be explosive or anything -- andrew's more the "quietly self-destruct climax" type than the "defeat the mafia thru the power of sports climax" type -- but it'll sure be something interesting. and then once it all breaks, we know he'll have neil and kevin and his family and the foxes to help him heal -- and he'll have to believe it when they show they care about him, because he literally doesn't owe anyone anything

#i think thats why all my aus put andrew in his Self Destruct Era#because im just so positive that he well on his way to that at the end of tkm#actually im amending the tags a bit bc i think what i sometimes end up doing w him in aus is a product of the fact that my stories rarely#have extreme external plot elements#like andrew never thinks neil DIES lol#baltimore is so fucking integral to andrews development#he did not have time to do the full self destruct 'oh no can i live without him' era because#he literally got tested on that and he FAILED HAHAHA#so he def knows that he needs neil#the crux of the conflict still is -- can he accept this without hating himself?#because if THATS not addressed then eventually his logic is going to warp#and hes going to do stupid shit#and yeah :) i love when he does stupid shit and then ppl are like#NOPE. unfortuantely you have fucked up severely#and in order to get back what you cant live without#you must board the Self Love Express !!!!#its a journey lil man!!!!!#youre gonna hate it!!!!!!!! youre gonna go on it anyway!!!!#SCRMEEEEAMMMM i love andrew minyard

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Characters Arcs

When writing a story, whether it be a novel or an epic film, it’s important to have subplots. While all stories should have, in addition to the main plot, something called a “B Plot,” C plots, D plots, and E plots should play a role too. Smaller plots wouldn’t change the entirety of the plot if removed...but when included, they can enhance the main plot, deepening it, and providing a greater meaning to the overall story.

While it isn’t always the case, the B Plot is often the “romance” of a story. While the hero is trying to defeat the bad guy, he develops a friendship or rivalry with a companion, before ultimately falling in love. Of course, romantic or platonic, the best sub plots explore the characters in relation to one another.

These character arcs - the changes to not only the characters themselves, but the evolution of their connection to others - give readers a reason to root for not only your hero, but the whole cast.

The film which exemplifies this point well is the first Lord of the Rings. While the groundwork for these characters, and their relationships, are laid in the book, I will be focusing on the movie version. When adapting Tolkien’s story, Peter Jackson knew the characters had to be more than names on a page. In order to foster a connection between the audience and each member of the fellowship, bonds were strengthened, or even invented, between the various members.

Merry and Pippin & Boromir

The bond between Merry and Pippin is solid in the books, but little is known about Boromir - beyond knowing he’s Denethor’s son, and a future steward of Gondor who attempts to steal the ring from Frodo, there is little else. In the books, he is a tragic figure and a lesson in how destructive the craving for power can be.

In the films, though, he becomes a friend to Merry and Pippin. He teaches them how to fight, and laughs when the two hobbits doggy pile him. It’s only one scene, but it gives us a relationship. When Boromir is later overwhelmed by orcs, it isn’t as punishment for his actions - instead, he redeems himself. He races to the defense of Merry and Pippin, giving his life for them. His death is that much more tragic because of his connection with the two. When they see him fall, he isn’t just their companion - he’s a good friend, who once laughed with them and ultimately died for them.

Aragorn & Boromir

Boromir also has a connection with Aragorn. The sub plot between the pair, which focuses on Aragorn’s mistrust in Gondor and Boromir’s belief in Gondor, is set up before the Merry and Pippin arc, beginning when Boromir drops the fragments of Isildur’s sword to the ground. His comment that these shards are no more than the remains of a broken sword underscores his lack of faith in Gondor needing a king - a point of tension between him, and the man who could be king if he cared to.

Boromir is an idealist, seeing the best in Gondor and loving it to an almost blind degree. Aragorn, by contrast, seems to care more for the elves than his “own” people. He leads the party towards Lothlorion, home of the elves, but makes a point of avoiding Gondor. He seems to hate Gondor, connecting it with the failure of his ancestor, Isildur; like Aragorn’s antecedent, Gondor is weak. When Aragorn refers to Gondor, he calls it “your city,” to Boromir, rather than theirs.

Following the capture of Merry and Pippin, and the seeming conclusion of their arc, Aragorn swoops in to fight off Boromir’s assailants. Though Aragorn wins, Boromir is fatally wounded. He dies, but not before regarding Aragorn with the respect he would to a king. Aragorn, in turn, seems to have hope for Gondor, promising to do what he can for their people.

This arc enhances Aragorn’s own character arc in accepting not only Gondor, but his role as it’s king. Boromir is a metaphor and embodiment of Gondor, and Aragorn’s feelings towards him are actually the feelings Aragorn has towards Gondor itself. His relationship with Boromir allows him to verbalize his inner conflict about his homeland, and who he is. In the end, he accepts Boromir as his fellow - along with accepting the city as his.

He hasn’t accepted his role as king yet, but Boromir’s relationship with him has set him in the right direction.

Gimli & Legolas

Though the relationship between Gimli and Legolas has little effect on the main plot, it adds both humour and character development to the story. Initially, being a dwarf and an elf, the pair are resentful towards one another. Gimli more or less joins the fellowship to one up Legolas, and the two aren’t above making snide remarks towards one another.

After Gimli’s own experience in Lothlorion, though, when the dwarf realizes that elves can be both kind and beautiful, the dwarf is able to soften towards his companion. Their enmity transitions into a rivalry - they aren’t friends, but they make battles fun by beginning a competition where they try to kill more orcs than the other. As they fight in more battles together, and swap kill numbers at the end of each fight, they develop an actual friendship (in the extended edition of the third film, they even end up drinking together). Their relationship is light hearted, but it adds depth to the story, and makes the audience want to root for the pair.

Both characters are enjoyable on their own, but together they are that much easier to love.

Frodo & Sam

In the books, Sam is Frodo’s gardener and servant. In the movies, he is Frodo’s best friend. While there is still a master and servant relationship between the two, with Sam addressing his friend as “Mr. Frodo,” the term comes to feel more habitual than formal. At the start of the film, the hobbits share drinks. Frodo pushes Sam into his crush, Rosie, and gives Sam assurance when he’s fretting over the competition he has for her affections.

When Sam eavesdrops on the conversation between Frodo and Gandalf, the wizard decides Sam will pay for his listening in by accompanying Frodo to Bree. On their journey, Sam panics at one point when he thinks he’s lost Frodo. He explains that Gandalf made him promise he wouldn’t “lose” Frodo.

Even when he’s no longer obligated to follow, Sam insists on joining the fellowship. Elrond notes there is no separating them, secret meeting or not. Later, towards the end of the story, Sam tries to comfort Frodo, citing his promise to look after his master. When the fellowship splits, Sam chases after Frodo. Frodo can go alone, but Sam is coming with him. He repeats the line that is the crux of his bond: he made a promise to Gandalf not to lose Frodo, and he’s going to keep it.

Sam stays with Frodo to the end, even coming back after being sent away at best (and betrayed at worst) by his master in the final movie. While their bond is implicit, the repeated promise, and the ups and downs their relationship takes, adds another layer to the story. Destroying the ring is challenging - not only because of it’s effect on Frodo’s health, but because of how it tests his friendship with someone who proves to be more loyal than most.

The bond Frodo has with Sam is also integral to the plot. After all, if it weren’t for Sam, Frodo would have been killed. With such a role, Sam needed to be more than a dedicated servant. He needed to be a loyal friend, capable of being tested and still willing to fight for their friendship.

In Conclusion

The set up of these sub plots allows the rest of the movies to be deeper too. While it goes without saying that establishing a connection between Frodo and Sam would improve their shared story arc, other sub plots are revived.

The connection Boromir shares with Merry and Pippin, for example, becomes integral to Pippin’s own arc. With Merry removed from his side, Pippin is then influenced by none other than Boromir, when guilt over his death pushes Pippin to pledge himself to the service of Boromir’s father, Denethor.

Gimli and Legolas go on to have journeys together, and start another body count contest in the third film (where an elephant “still only counts as one” when Legolas dispatches it).

New sub plots are also introduced, such as the bitterness between Faramir and Denethor, but most of the plots are established in the first movie. The relationships between characters make the story matter, and carry it through; the groundwork laid by these bonds even sparks new storylines. Even after his death, Boromir’s relationship with Pippin influences his actions.

#writing inspiration#writing advice#writing#lotr movies#lord of the rings#lotr#character arcs#sub plots#writing tips#writing blog#writing community#book blogger#book blog#hobbits#fantasy books#book plotting#authors#writers#writers of tumblr#writers life#tolkien

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

yuki’s character arc: gay subtext edition

this has probably been a while coming but i’m finally here to talk about the gay subtext in yuki’s story.

[a lil note before i get into things: i know takaya didn’t intend to include this subtext in his story, and with that this is very obviously getting into “death of the author” matters. however, the subtext, though unintentional, is still prevalent, and leads to both an interesting analysis of yuki’s character and, for many, a deeply relateable storyline regarding gender, compulsory heterosexuality, and being closeted.]

yuki’s character arc is, in large part, a story about self-understanding and self-acceptance. he starts off as a character unsure of his true qualities, or of his place in the world; he is self-conscious and driven by other people’s acceptance of him, which causes him to have deeply different private and public personas. he hides away his “real” character in part out of a fear of being disliked or ostracized, and in part because he is still struggling with accepting himself. the result is that he puts on an act to please others, playing a role that is not true to him, and a role that he knows is false, in order to be accepted. his story bears a distinct resemblance to stories and lives of people who struggle with accepting their sexuality: matters of hiding the true self out of fear of being misunderstood or abandoned, dealing with gender and gender expression, coming to terms with compulsory heterosexuality, and finding people who both accept and cultivate his true identity.

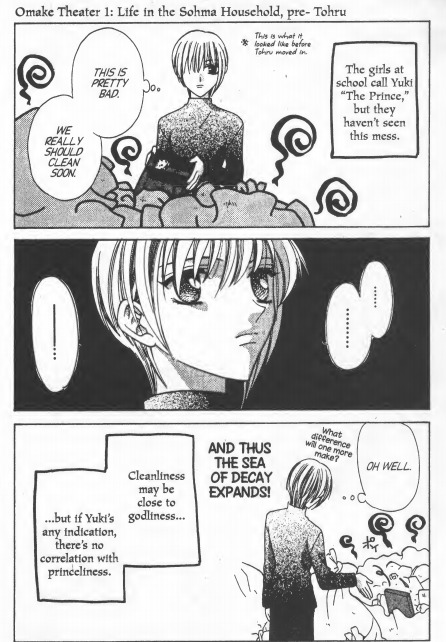

from the moment we’re introduced to him, we’re to understand that yuki has a distinct persona for his social and school life, which is in direct conflict with the persona he leads in his private home life. before even introducing our main protagonist tohru, takaya first introduces us to yuki in an omake -- he’s presented at home, surrounded by trash, and not bothered enough by it to take it out or care that it’s expanding.

it’s a short, but apt intro for his character. we know that people outside of his home circle call him “the prince,” and that he’s actually kind of a mess. we don’t know yet why people call him “the prince” (if it’s because of his looks, his family’s status, if he has a personality that seems princely in some way), or if his school friends (if he has any) refer to him this way, or what his family views him as in contrast to how he’s viewed at school. regardless, we do get to see the crux of yuki’s character and story straight away, even before the story has really started. yuki is someone who has conflicting personas between his private and social life, and considering that these do conflict so heavily, we can assume that the persona he shows at home (his “real” character, in a sense) is hidden from his peers.

we learn rather quickly from tohru, and her interactions with other girls at school, that he’s considered the “reigning prince” because of his beauty, his mystery (caused by him being rather distant from his peers despite his popularity), and his polite nature. we also understand him to be somewhat socially isolated, not of his own accord but because of his fan club “protecting” him, as well as the curse, which keeps him from being close to the girls who adore him anyway. this isolation is something that tohru herself doesn’t immediately perceive, but she comes to realize that he’s someone who not only bottles up his emotions, but cares deeply about what others think of him. he then admits to her his isolation, feeling caged by his family, and his struggles with getting close to others, saying:

“I wanted to have a ‘normal’ life, surrounded by ‘normal’ people. So I applied to a co-ed school and left home. But I couldn’t get out of the cage after all... I just wound up at another Sohma house. And I still can’t associate with ‘normal’ people. I don’t mean to turn them away, but some part of me can’t deal with people. I cut myself off from other people because I’m afraid of getting hurt, and because I’m [cursed]... I’m only being nice because I want people to like me... My being nice is entirely selfish.”

from this, we understand how he perceives his curse: it’s something distinctly socially isolating for him, and as it’s something he was born with and can’t be rid of, he feels unable to navigate his social life without leaning into the persona given to him, and expected of him, by his peers. however, although he feels as though the curse is what keeps him from associating with “normal” people, this is not a mutually understood feeling among all of the cursed sohmas. while the curse is something physically isolating (as they’re unable to hug or be closely intimate with the opposite gender), we see that the curse is interpreted by the zodiac members in different ways outside of this physical isolation. for kyo, it’s not an isolation from his peers as it is for yuki, but rather an isolation from his family, both cursed and immediate; for momiji, the curse isn’t socially isolating, as he doesn’t struggle with his peers, and he instead views it as something that bonds him to the other cursed sohmas when he has been abandoned by his parents. there are varying levels of accepting the curse among the family, and though they are bound by the same manner of physical isolation, how it manifests outside of that is different for each zodiac.

this is to say that yuki’s curse, and how he perceives it, follows the sentiment of being closeted. he feels unable to associate with “normal” people because of a part of him he is unable to control. he views his family, and his curse, as a cage, as something he wishes to escape but cannot run away from. this cage follows him when he attempts to integrate himself into a “normal” life, and thus causes him to further struggle with feelings of resentment towards the curse, as he perceives it as being central to his struggles of achieving social normalcy. meanwhile, from viewing how other cursed sohmas do not have this issue of social isolation, and can lead social lives that yuki would perceive as normal -- even if they, too, resent the curse, such as kyo -- we can take this to understand that yuki’s struggle with social isolation comes from a fear of being socially ostracized for this part of him that he can’t control.

he attempts to repress it via leaning into the social persona given to him by his peers, as acting as “the prince” retains his connection to others despite it being isolating in and of itself, via his fan club deeming him untouchable and harshly dissuading others from getting too close. his performance as “the prince” is as much a means of protection as it is to his detriment; he takes comfort in being liked by others, even though it is both superficial and goes beyond normal reasoning by encroaching on his personal boundaries (his fan club taking photos of him without his permission, stealing flowers he made for the culture festival, etc.), but is to his detriment as he feels he has to live up to this persona, which causes him to then hide his real self, and even become unsure of where the “real” yuki ends and “prince” yuki begins. by this i mean, he is shown to view the attributes given to him by his peers as false, because they aid in his false persona, and that he uses these attributes to gain the trust and liking of others -- this includes his kindness.

yuki’s low self-confidence and insecurity causes him to be unable to see the positive attributes that others see in him. as he understands that the attributes that lend to this princely persona include his kindness, he takes this to believe his kindness isn’t genuine, and that it’s merely a part of the act. it’s only when tohru, who is involved in both his social and private life, and has thus been the recipient of his kindness at school and at home, explains to him that his kindness is very much real and a part of him that he begins his journey in trying to understand himself.

it’s important to understand the intricacies of how yuki goes about viewing his personas, as he shows to not only hide his true self from others, but also lacks an understanding of himself. he struggles to find the precise line at which his true self ends and the prince begins; he believes that his bad attributes are his truth, while his positive attributes are reserved for the prince. this lack of personal understanding, and viewing himself in such a harsh and negative light, stems from his emotional and mental abuse sustained by his mother and akito. his mother insists that yuki is unable to make decisions for himself and, in making all of his major decisions for him (his attending prestigious compulsory schools, her adamance on selecting his college) gives him no foundation for building his self-esteem. akito’s possessive, cruel, and belittling attitude towards him further damages his self-esteem, as he believes her when she tells him that he is worthless and hated. in addition, both are the basis of his isolation and abandonment issues, which then stems into his need for his peers to like him -- causing him to repress his true self as he has come to believe it’s no good, and hanging onto the prince persona that is given to him even though it is, in itself, isolating. although the prince role makes him lonely, he hangs onto it because it is less isolating than the social isolation he experienced through his compulsory education, his isolation from his mother and brother, and far less isolating than the physical isolation he experienced from the “special room” akito kept him in.

it’s only when tohru coaxes him away from the idea that he isn’t genuinely kind, and becomes his friend, that he can begin to understand who he is outside of his family, the curse, and how his peers view him. rather than separate himself by private and social personas, he begins to grow into an identity that is applicable for both his private and social spheres. by the end of the story, the yuki who is shown at home, and the yuki who is shown at school, are much the same person.

included in this journey, too, are yuki’s issues with how others perceive his gender.

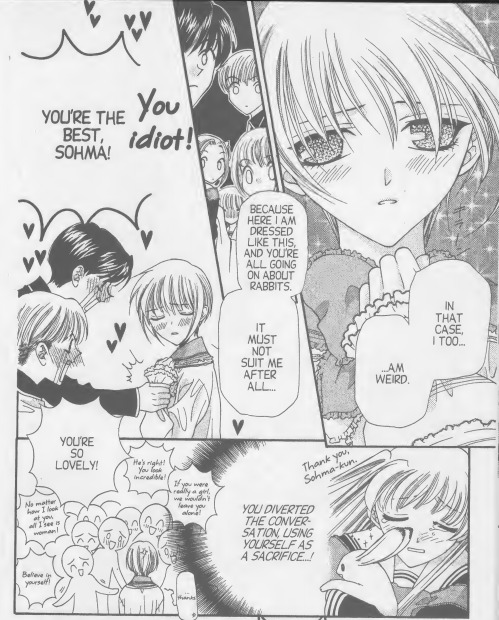

we see multiple times how people regard yuki’s appearance: they call him pretty, they question whether he’s a boy or a girl, and some are convinced he’s a girl until told otherwise. he’s dismayed by his looks, with kyo saying that he’s “really self-conscious about his pretty face,” but despite this isn’t against using them when the situation calls for it -- which is never for his own want or gain, but always for others. we see this in particular during the first culture festival, when he agrees to wear a dress as a means of appeasing the third-year girls. he agrees to do it in order to avoid breaking his social persona, and in doing so disregards his own wants and comfort levels. he clearly doesn’t like the attention he receives from this act, but at the same time uses his beauty in order to protect his family:

when kyo suggests that yuki actually enjoys this type of attention, in which people call him cute, pretty, “womanly,” and the like, yuki reacts violently, solidifying that it’s something he is seriously uncomfortable with (though he admits to tohru that he doesn’t mind when she, a friend, perceives him as such, and this is perhaps because he has a level of trust and comfort with her, and at this point feels she sees more of him than most do). he acts on his beauty a few other times, such as distracting the postman when kagura transforms, and even gets out of situations when he’s perceived as a woman without acting on it, such as when he and kyo retrieve tohru from her grandfather’s house and her male cousin, who displays an attraction to yuki, is stunned to the point of inaction at learning yuki is a boy.

this distinct discomfort of how people perceive his gender seems to come from multiple channels. there is the general viewpoint of a teenage boy trying to fit in socially, while also giving in to what his peers expect and create of him -- the pull between acting masculine, as that is typically expected of his gender, and acting polite and soft with his “prince” persona, which is socially perceived as detracting from the former. he takes a long time to come to terms with how he wants to present himself, as he doesn’t want to come off as un-princelike to his peers, but also often gives in to these more masculine traits outside of school (getting in physical fights with kyo, having little to no sense of keeping tidy surroundings at home, being short-tempered and harsh-tongued with shigure and haru, and the like). while his at-home persona is never quite as tough as how kyo or haru present themselves, it’s still more masculine than the personality he shows while at school.

his relationship with his brother ayame also weighs on this matter, as ayame is someone who is extremely comfortable in his flamboyant gender expression and doesn’t care how others perceive him. while yuki doesn’t necessarily dislike him for this reason, it is something that puts a wall between them simply because yuki cannot relate. this is shown as ayame and yuki are perceived by others quite similarly, as we see people question ayame’s gender and see how others fawn over his beauty. the difference is that ayame doesn’t have the distinct personal and social personas that yuki has created -- ayame’s true self is being someone who is quite comfortable blurring the lines of gender expression, and is someone who truthfully leans into his androgynous beauty, regardless of how others view him. yuki, on the other hand, is uncomfortable with his androgyny, but frequently leans into it due to social pressures. he doesn’t quite understand how his brother can so easily be the way he is.

it’s not until later, after yuki has befriended kakeru, that we see his true expression begin to emerge. interestingly, it’s in part because kakeru both sees him for who he is, as tohru does, and teases him over his beauty and princely status at school. kakeru calls him “yuki-chan” after first meeting him, and even more frequently calls him a princess as a means to denounce and poke fun at his prince status. though this is a sore spot for yuki at first, and causes some resentment towards kakeru before they’re able to befriend each other, kakeru teasing him by calling him a “princess” in some ways validates yuki’s emergence into becoming his own person; beyond teasing yuki for being pretty, kakeru is making fun of the princely persona that his peers have put onto him. it’s part of how yuki understands kakeru to see him -- he’s able to see that yuki really isn’t this prince that people believe him to be, and that the moniker is unfitting to the point of being laughable.

however, considering that being called a princess still denotes that yuki is in a way girlish, it’s still something that yuki fights kakeru about, but in a far less severe manner than his fights with kyo over the same words. his fights with kakeru are far more playful, and come from kakeru’s penchant for pushing yuki’s buttons out of fun rather than a point of unkindness, as is the case for kyo. this is similar to how yuki doesn’t mind if tohru calls him cute -- he has a level of trust and understanding with kakeru, and feels that kakeru really sees him rather than a false persona, and fights kakeru more because he’s being teased. his fights with kyo are more defensive as kyo says these things as a means of belittling him, while viewing him as someone who he really isn’t.

gender expression, and how one’s gender is perceived, is often another point of contention within lgb+ narratives, as there come certain social stereotypes for how gay people are to express their gender. by which i mean, gay men are often stereotyped as coming off as effeminate, lesbians are stereotyped as being somewhat masculine, and the like. this in turn causes society (in a general sense) to believe that boys and men who deviate from the straight, masculine norm must be gay, and similarly that girls and women who deviate from the hyperfeminine norm must be lesbians (though, it is generally more socially acceptable for women to take on boyish or masculine traits than it is for men to take on feminine traits). as being gay is socially ostracizing, boys and men who are perceived as such due to their feminine traits may then reject or deny them.

for yuki, this struggle with what others perceive as his femininity comes at a crossroads, as he both finds these traits to be embarrassing, but doesn’t fight against them as his peers seem to enjoy his unmasculine beauty. in the series, the only person who really disparages yuki for his more feminine traits is kyo; he is otherwise not socially ostracized for it, and instead feels a deep insecurity around it simply because he doesn’t enjoy the attention (from both boys and girls) and just wants to present as more masculine in his social life. however, as he hangs onto the acceptance of his peers through his femininity, he struggles to really present his more masculine traits in social settings -- that is, until he joins the student council and befriends people who see him for who he is rather than who he is expected to be. it’s through his socializing with the student council that he begins to bring the more typical masculine traits he presents in his private life to school (through being more physical, raising his voice, etc.).

this is not to say that yuki is gay/non-straight because of his femininity (we never see other characters assume he’s gay, but rather see other male characters seem to question their own sexuality upon realizing that yuki isn’t a woman, or otherwise by admitting to being attracted to him because they focus on his femininity). to say so would be stereotypical, and narratively wrong. rather, this is more to do with how expected gender presentation can be in conflict with personal gender presentation (this can occur regardless of sexuality, however tends to be particularly prevalent in lgb+ circles due to the inherent subversion of expected gender norms that comes with being non-straight; this is part of a much larger dialogue in how heterosexuality is the basis for expected gender conformity, and how “masculine” and “feminine” traits are perceived as being applicable to men and women respectively, when in truth these traits are applicable across the gender spectrum.) in typical narratives, the expected presentation for men is to take on masculine traits, and a deviation from that towards the feminine brings the subject’s sexuality into question (even if the subject is straight).

for yuki, the matter is more complicated, as his expected gender presentation actually falls into both masculine and feminine -- he’s expected to present masculine traits on the basis that he’s a boy, however is also expected to present feminine traits due to the social persona of the prince that his peers have placed on him. for yuki, the matter of gender presentation is in constant conflict, as he feels uncomfortable in being perceived as feminine, yet leans into that presentation in order to appease the expectations of his peers. again, his conflicts with gender presentation alone do not necessarily make him non-straight, but the presence of such a conflict is prevalent in lgb+ narratives.

it’s important, too, to recognize the matters of sexuality that present themselves in yuki’s immediate circle, namely through haru and ayame. when we’re first introduced to haru, he tells tohru that yuki was his first love; when we’re introduced to ayame, he tells a story of his youth where he told the boys at his school to “direct their passions at [him]” in order to keep them from getting in trouble for being intimate with girls. the matters of talking about the sexuality of these two characters becomes difficult if only because they’re presented as a means to shock or joke, rather than as something that is discussed seriously. haru and ayame’s attraction to men isn’t meant to be taken seriously by the audience (the reveal of these attractions are met with shock/distaste by our main cast), and as such yuki’s response to their sexualities is that of annoyance. if we’re to remove the (maybe less than gentle) mockery of non-straight identities, yuki’s reactions to both haru and ayame could instead be read as him internally tying their sexualities to their odd and outlandish demeanors -- and yuki, as a character who by and large tries to keep his head down and do what is expected of him, pushes the notion of homosexuality away because he finds it to be in conflict with his character. he doesn’t consider it, because it doesn’t fit with his expected personas.

(compare these moments, which happen early on in the series, to a much later scene where kakeru openly discusses how attractive the men in the sohma family are, and yuki isn’t annoyed with him despite kakeru also being in a close relationship to him and having a similar outlandish behavior to haru and ayame; the line for how acceptable it is to discuss the attraction of and to the same gender becomes murky, and because so much time has passed and yuki has gone through some personal growth, it’s unclear if he has become more accepting of these attractions or if he just perceives them as being different.)

but, again, the discussion of how homosexuality is presented in the series is difficult to analyse, because it’s not presented as something to be taken seriously. it’s fair to say that yuki’s reactions to haru, ayame, and kakeru are more about the context they’re presented in than just their attraction to men alone -- he gets annoyed with haru because haru insists that he was his first love (an unrequited attraction, and one he doesn’t take seriously), he gets annoyed with ayame because he finds ayame’s person to be too outlandish as a whole to even begin to understand, and he doesn’t get annoyed with kakeru because he knows kakeru is in a committed relationship with a girl, and that saying that men are attractive doesn’t necessarily imply an attraction to them.

the matter of sexuality, though, is prevalent in yuki’s story despite the narrative’s dismissal of it, and this comes to light through his discussion of his compulsory heterosexuality towards tohru.

chapters 83 and 86 primarily deal with this matter, and it starts off with the quite literal scene of yuki being trapped in the student council’s storage closet, thinking about both the trauma of his isolation in the dark room and having a moment where he imagines akito belittling his feelings towards tohru. while not immediately apparent, it’s here that he internally faces his true feelings for her after having ignored them for so long. at first, he continues to feel pathetic and demonizes his feelings, imagining akito saying these words instead of hearing them through his own internal dialogue (a means of filtering his negative thoughts through the image of his abuser). these have been the personal demons he’s been fighting since after kyo’s true form arc (numbers-wise, that’s roughly fifty chapters out of a 136 chapter series), and in that period we’ve seen him struggle with whether he should “open the lid” on his feelings

then, in continuing the visual of yuki being in the closet, the door is broken down by machi, at which point she says that she thought he “wouldn’t like being alone and helpless in there,” mirroring the sentiments he felt being physically isolated and mentally abused under akito’s care. and in leaving the closet, he finally admits to himself, kakeru, and the audience, that he isn’t romantically attracted to tohru, and his attraction to her was compulsory. he loves her, but views her as a mother figure.

this is one of those moments in the series where the subtext is almost so, so blatant that it’s just text, but i digress.

the acceptance that tohru gave him in the very beginning of the series, when he was incredibly conflicted in his identity and buried in his low self-esteem, cultivated his growth into finding out his own worth and who he is. as mentioned, his family life growing up did not give him this foundation, and so in her giving it to him instead, he received from her what he should have received from a parental figure -- his mother in particular, as his father wasn’t present.

however, being that she’s the same age as him, and finds this relationship to be strange, he attempted to warp his own feelings towards her into something more acceptable, and has this conversation with kakeru in explaining those feelings:

Yuki: “I needed a mother’s love. And before I knew it… I found it in Honda-san.”

Kakeru: “Even though she’s a girl you can be attracted to?”

Yuki: “Yes. Well… before she was someone of the opposite sex, she was really more like a mother to me. And that’s what I’d been looking for. But I panicked. When I realized I was thinking of her that way, I got confused. Very confused, actually. The whole thing was embarrassing, and I didn’t want to admit to it. I pretended not to realize, at first, anyway. I put a lid on my feelings. I told myself it wasn’t like that. I tried to talk to her, like boys do to girls. But I was wrong. That’s not the way it is with us.”

admitting that he tried to bury his real feelings, and attempted to force his feelings to be romantic for her instead, can be at face value read as him having a sudden understanding of his sexuality -- here, becoming confused to the point of panic when he realized he wasn’t romantically attracted to her -- in a way that indicates that he isn’t straight. his embarrassment here comes from his seeing her as a mother figure (and with that, his feeling that their relationship isn’t balanced), but still follows the narrative of compulsory heterosexuality. he assumed that, because he was a boy, and she was a girl, and he was experiencing intense feelings for her, those feelings should have been those of romantic attraction.

compulsory heterosexuality is just about as it sounds -- the “straight until proven otherwise” argument. acting under the assumption that one is heterosexual, there’s the sense that strong romantic or sexual feelings towards the opposite gender must be cultivated, and when those feelings fall short (such as coming to the realization that the feelings aren’t romantic or sexual in nature), there comes confusion; as compulsory heterosexuality is cultivated by a heteronormative society, it also creates a confusion on a social level. we can see this here with kakeru questioning yuki’s feelings, asking why he can’t view tohru as both a mother figure and someone he can pursue romantically, and telling him that he’s essentially giving up for no reason. yuki, in turn, tells him he’s not giving up -- it’s just that he truly is not, and cannot, be romantically attracted to her.

in a similar manner, as yuki comes to terms with how he understands his own romantic feelings, he’s rather blind to when girls have romantic feelings for him. this comes to light when he realizes that the leader of his fan club, motoko, has also been harboring romantic sentiments for him, alongside the many third-year girls who he has had to turn down as they attempt to confess to him before graduation. he remarks that he’s dense, and that he feels bad because he can “do nothing but hurt those girls.” this more or less goes along with his coming to terms with understanding how he experiences romantic attraction, but is also an interesting reveal of how he has misunderstood his role as the “prince” -- though he sought after the affections of his peers, and got that tenfold from his fan club (despite their overbearing and obsessive mannerisms), he never believed that the girls in this club liked him to the point of romantic attraction. he’s confused when he navigates his non-romantic feelings for tohru, and confused when he realizes motoko loves (or, loved) him, despite her creating the prince yuki fan club, and being its dutiful leader for two years.

at this point in his story, though he is at a much better point in his self-confidence and identity, he admits that he still holds the same weakness as he always had. this includes his self-worth, and being unsure of how people really feel about him. that wraps around to a part of him that is still socially isolated, that makes him feel unable to fully associate with “normal” people, in this case, girls in particular: his curse.

this is going back to my earlier sentiment that the way in which yuki perceives his curse closely follows narratives of being closeted. at this point, he has found a confidant in kakeru, and finds kakeru to be the one person who he feels safe discussing personal matters with -- not just his relationship with tohru, but also talking to him about some parts of his family life. he did, in a sense, “come out” to kakeru when telling him that he doesn’t have romantic feelings for tohru, and for a relationship between two boys, this seems apt. he was closeted by the “lid” he kept on his feelings for tohru, and is closeted still by his curse. he doesn’t consider going to kakeru about the curse because that doesn’t affect his relationship with him the way admitting his lack of attraction to a girl does; rather, it affects his relationships with girls, and still leaves him somewhat stunted in understanding the give and take of emotions between him and them. machi becomes an outlier, if only because she’s the only girl who has ever seemed to view him differently (sans tohru; and even then, kakeru points out that yuki is slow to understand machi’s feelings for him). she had always rejected his prince persona, and was extremely slow to warm up to him. but, as he reaches out to her and becomes her confidant, she reaches out to him in turn and actively seeks his presence above anyone else’s. he feels seen by her, and feels needed by her.

he and machi start dating at the end of chapter 125, and it’s a few chapters later that he begins to question whether he should open up to her about the curse. in his thought process, he directly reflects the language he used with tohru in the beginning of the series, when he told her he struggled with associating with “normal” people:

“Honda-san knows that Kyo’s not a normal person. She already knows, and she has for a while. But… in my case… I have to tell [Machi]. If I want to stay with her… then I have to tell her the one thing that she may or may not accept.”

similar to his “coming out” to kakeru, yuki now has to “come out” again with his secret of the curse to machi. although this is an essay about gay subtext, it is important that it’s machi who he’s coming out to, if only because the mechanics of the curse are inherently straight, and, well, he’s dating a girl who this directly affects. there is still the distinct story of hiding something so integral and important to your very being away in order to avoid isolation, ostracization, and abandonment -- and this comes to a head when it affects one of the very relationships that helped him grow out of his shell and into his identity.

in a twist, we never actually witness yuki “come out” to machi. the curse lifts just before he is able to do so. instead, he feels freed from the last wall of isolation that kept him from her, and in the moment says “right now, this is enough” as he’s finally able to hold her. and i don’t think this is something to feel cheated out of by any means -- while it would have been interesting to see machi’s reaction, at this point in the story, he already has been accepted by her, as she is one of the few to take him as he is without any presumptions attached. and this reflects an earlier thought he had of her, in which he said:

“Crowds used to make me wonder: how many people would notice if I disappeared? I used to mull over that kind of thing constantly, once upon a time. But now… I’m a little different. It’s not like that. It doesn’t have to be a lot of people. Even if it’s just one person, that’s enough. Having one person is an incredible thing, because then it can’t be zero. I was happy. I was happy then, too… In the midst of all those people, she singled me out and found me. Having someone other than yourself thinking of you, looking for you… you can’t take that for granted.”

this isn’t meant to be an argument that yuki “should have” ended up with someone else, or should have been canonically non-straight -- the story is what it is, and at the end of the day the story is predicated on basic heteronormative social aspects, centered around a curse that, while it symbolically goes deep into abuse, trauma, isolation, and the problem of those things being cyclical, mechanically functions as hetero isolation. for yuki to come to terms with his curse, and his ever-present anxiety over not being able to fully integrate with “normal” people, it was narratively necessary for him to be pushed by his relationship with machi. while he experienced social isolation on all fronts, his ending up with a guy likely wouldn’t have created that same sense of urgency (hence, why he never so much as thinks to tell kakeru about the curse, despite their closeness and his ease with him in opening up about personal matters), or resulted in a finality of his curse that allows for a physical act of symbolism to announce the end of his isolation.

it’s regardless of the heterosexuality of it all that makes yuki’s story so very relateable on the basis that it can be interpreted as gay-coded. it doesn’t really matter that he ended up with a girl** -- what matters is that his curse, the thing he needed to “come out” to her about, in itself is easily read as his struggles with accepting his sexuality as part of his long, winding road in accepting himself fully. his similar “coming out” to kakeru about his comphet feelings, his long-standing struggles with his gender, and his overall struggles with understanding himself in the face of his fears of abandonment and social isolation, all come together to make yuki’s story one that is easily read as coming to terms with one’s sexuality in their journey of self-acceptance and self-love.

**here, i mean ‘matter’ in terms of narrative -- gay representation in media is of course necessary, and even though yuki can be so easily read as a gay or otherwise non-straight character, that doesn’t mean that the story upholds positive gay rep.

#fruits basket#yuki sohma#im done hyperfocusing on this im sleepy#anyways sorry if its uhhhh a mess LMAO i guess i've forgotten how to format like.....essays#anyways if u wanna know how i managed to not mention like the yukeru-ness of a lot of this story.........#idk u can ask but it just didn't feel right to put in this essay ig#the gay subtext of his story in large part doesn't even need to be explained by his relationship or chemistry w kakeru#shocker i know#this thing is like 6k words long and i still feel like there are major things i'm missing lmaooo#o well#yunsoh meta#fruits basket spoilers

410 notes

·

View notes

Text

TT Liveblogs Evangelion Masterpost & Final Thoughts

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Final Thoughts after the cut!

By reputation, I had a strong feeling that Evangelion was not going to be my kind of story, and now that I’ve seen it I can say that both kind of is and kind of isn’t the case. The character writing is incredibly strong (even if I feel End of Evangelion has a few major wobbles), its approach to its cosmic horror conflict and uncanny monsters is incredibly interesting, the animation is gorgeous, and the plot is compelling. It’s way more tragic than I usually prefer my stories of this length to be, but I feel it earns that tragedy and has a point to it. At the very least, it ranks among works like Heart of Darkness and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which I respect for their artistry even if I struggle to stomach their content. I would say it’s objectively great, even if subjectively it doesn’t always suit my personal tastes as far as stories go.

Given the two endings Evangelion (both the original show’s last episodes and the alternate ending offered by End of Evangelion) has both explore the idea of there being different realities than the one we’ve watched, I almost wonder if my discontent is a feature rather than a flaw. I feel like Evangelion invites you to consider the possibility of this story going very different ways - if we’re supposed to leave it longing for a better version of these events, like a player hoping there’s a new game plus after watching the depressing ending of a JRPG.

As a person who’s struggled with self loathing his entire life, this series spoke to me in its analysis of that particular psychological problem. As the final episodes of the show take great pains to make clear, this is a show about how we understand and define ourselves in the context of others, and the myriad reasons why our self definitions can become toxic and hateful. Hating oneself should, after all, be rather counter-intuitive, so why are we prone to it?

Evangelion posits that it comes down to the Hedgehog’s Dilemma - this (probably not biologically accurate) idea that hedgehogs want to huddle together for warmth when it’s cold, but can’t because their spikes will stab each other if they do. They need their spikes for defense, of course, but those same spikes can also hurt people trying to help them, and thus the hedgehogs suffer alone in the cold. Every character in this show - human and, I would argue, angel alike - is this allegorical hedgehog: they crave warmth and affection, but are kept lonely and cold by the defenses they deem necessary. The problem isn’t just that they’re denied warmth by others, but that they also fear hurting others in the process of seeking that closeness - that they are both helpless and incapable of helping those they wish to protect.

Every character in this show has different spikes, and every character is desperately hoping that someone will reach out and understand them despite their defenses, or that maybe, just maybe, if they reach out to someone they won’t end up stabbing them in the process. That’s the real crux of this two-fold problem: people hate themselves both because they have been denied both love and the act of giving love to others in turn, all while knowing deep down that they are the reason they have these damn spikes in the first place.

And yes, I extend this to the monsters as well. While most of the angels in this series are destructive and openly antagonistic , three actually try to communicate with humanity in their “attacks.” The first two are unsuccessful because the humans are incapable of understanding them, but the third actually manages to speak humanity’s language. He expresses regret at the fact that angels and humans can’t coexist, and even urges Shinji to destroy him because it’s the only way Shinji can live - and the angel, despite knowing it means his death, prefers the idea of Shinji surviving their conflict. While we ultimately don’t learn enough about the angels to say anything concrete about their motives, the glimpse that Kaworu gives into their psyche paints them in a similarly depressing light as humanity. They lash out with their figurative (and sometimes literal) spikes not because they hate humanity, but because they believe they have no option. They can’t have warmth. There is only the path of spikes, the act of violence. Whether they want to or not, only one can survive. They have succumbed to the bleakness of the hedgehog’s dilemma.

I love the ending of the show because it focuses on its psychological problem which, ultimately, is the true conflict of the story, and examines it in depth with all the main characters, and especially Shinji (which makes sense, as his psycholgical state is the most detailed and well developed of the entire cast). In the final episode, Shinji finds the solution to the hedgehog’s dilemma that no one else was brave enough to come to. He realizes that, yes, it is impossible to interact with others without both getting hurt and hurting others in turn - that he can’t get rid of his spikes, nor can anyone else get rid of theirs. But as much as he hates the pain he’ll both experience and inflict, he realizes that he has the courage to try to reach out anyway - that though he may hate himself now, he might be able to love himself as he loves others, and that being imperfect doesn’t mean he’s worthless. Despite all the pain and the guilt, despite the prick of the spikes, Shinji decides to keep trying to find the warmth that he and those around him need, because if they all keep trying together they can find it.

Evangelion ends with Shinji, surrounded by his peers, determined to recover. He refuses to be destroyed by his depression. He refuses to die in the cold, and everyone is there with him when he does. It’s not an incongruous moment - for all the angst that people tend to define this show by, there are always moments, small but notable, impactful moments, where they come together. Few people on this show are beyond saving, and in at least one ending - esoteric and weird as it is - they have that chance.

I’m less keen on End of Evangelion as an alternate ending. Where the original show gave Shinji that moment of recovery, End of Evangelion seems deadset on destroying him and every other character in the show as utterly as possible. Shinji gives in to his absolute worst impulses in this movie, and every other character is similarly destroyed by their faults - Misato tries her hardest but fails to ultimately protect Shinji from doom, Rei is used as a tool for someone else’s designs without ever truly understanding what they are or claiming her own independence, Asuka dies trying and failing to prove her worth as a warrior, and on and on it goes. The most iconic scene of the film is scored with a song whose lyrics are a suicide note, which is fitting for a movie about depressed characters succumbing to their worst impulses and being destroyed for it. Though Shinji once again gets to survive the end of the world and create something new from the ashes, it’s not uplifting as it was in the show - instead, with only Asuka by his side (who he then tries to strangle), he slumps down into a puddle of self misery. The last word he hears isn’t “congratulations” this time around - it’s “disgusting.”

I’m not saying this is a wrong ending, or an objectively bad one. You could argue this is just as much where the story might have been heading as the show’s ending - or even that it’s more congruous, that this was always going to be a story about failure and self destruction, and that any hope these characters could have for a better life could only be achieved by fucking with the nature of their reality on a fundamental level. Objectively, End of Evangelion is valid. But for my personal tastes... I liked those kernels of hope. I’ll take Congratulations over Digusting. I want these kids to heal.

One final bit: a common thing I’ve heard about this series is that the allusions to Abrahamic religion and folklore are purely aesthetic and have no actual deeper meaning, and having watched the series I think this is at best an over-simplification and at worst completely wrong. Like most allusions in literature, I don’t think they work as a direct 1:1 comparisons - Adam in Evangelion is not literally the same as Adam in the Bible, Angels in Evangelion are not literally the same as in the Bible, etc. But there’s still a lot of meaning behind how these Biblical references are used that can’t be mere coincidence. For example, towards the end of the series it’s revealed that human being are actually half angel (or rather the spawn of a different angelic being than the angels in canon, it’s a bit more complicated than this but let’s simplify it for the sake of making this intelligible), which is why the “pure” angels are trying to wipe us out. In the book of Enoch, a fairly obscure non-canonical Biblical text, some rebel angels come to earth and crossbreed with humanity, creating the nephilim, a race of half human/half angels. Enoch posits that this is the specific crime that makes God destroy the earth in a flood. Now, how does End of Evangelion end? With humanity being destroyed and the earth flooded with their liquid remains, save for one surviving pair that is composed of one boy and one girl. It’s not a 1:1 allusion, but it would be one HELL of a coincidence that this story is so similar to an obscure non-canonical Biblical work.

And if we do accept the allusions as having some meaning, they actually work with the show’s themes fairly well. The Book of Enoch’s whole purpose is to explain why God hated humanity enough to destroy it, and the feeling that a higher, cosmic power hates us for some inexplicable reason is at the core of Evangelion. Evangelion’s whole purpose is to find an answer for why we hate and destroy ourselves, and how we, like Noah, might find a way to save ourselves from this seemingly inevitable flood of doom. Making an allusion to another stories that try to explain that - not just the Book of Enoch, but to similar Biblical stories about the origin and nature of humanity’s sin and God’s scorn, like the Genesis tale of Adam and Eve (or, as Evangelion substitutes, Adam and his semi-canonical first wife, Lilith) - is inherently meaningful. It’s on topic, and in the context of these allusions we get a clearer view of what Evangelion is trying to say about human nature. It’s not necessarily a Christian story, but its allusions to Abrahamic religion aren’t devoid of meaning.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

6.4 Basta

I actually half heartedly tried to make a proper post about 6.4 Basta, but I have too many different things to say so listicle it is, keeping with the tradition of my SkamIT meta posts.

in the very first shot, when Ele lags behind as her and Edo walk, she looks so much smaller than him. And like, she’s shorter, that’s a fact, but the shot exacerbates that and I wonder: is it her feeling particularly small? Or does Edoardo feel like the Big Bad Guy/Wolf (aka the epitome of menacing characters) to her?

then Edo starts talking and tells Eleonora how she feels and puts words in her mouth. Does he correctly guess the things Ele is thinking of saying? Yes, he probably gets very close. Does it give him the right of him to speak for her? No. He is trying to make them communicate and that’s good, that’s healthy in a relationship, but then it’s not a two way communication, it’s him telling her how she feels and what she’s gonna say.

Let’s talk about the conversation he imagines between them: he says Ele is gonna tell him to stop punching people; his answer is “Okay, but I told you to stay inside.” and guess what? That’s not a fricking answer to the problem Ele would be pointing out. She’s opposed to the frequent resort to violence on Edo’s part: if she had stayed inside, she wouldn’t have seen the violence, but it still would have happened. Besides, why should she have stayed inside? Who is he to tell her where to go and what to do? She was safe anyways, all girls were since they stayed well out of the fight and just watched. So, what he really means is: “Okay, you seeing me punch people was your own fault because I told you to stay away, so that I could (potentially) lie to you and downplay my part in the fight and how violent it was.”

Then Edoardo continues imagining their conversation: Eleonora would object “Okay, but you have to stop [punching people].” which is a fair assessment of how she’d react to his previous non-answer; then he says ⟪and I’ll tell you: “Okay, I’ll stop.” Peace. The end. We kiss and that’s it.⟫ and here lies the biggest problem imho: the way it sound to me is that he’d agree with her just to stop fighting so they can go back to making out, he wouldn’t do it because he understood what Ele’s problem with what he did is, he’d just agree in order to make up, he wouldn’t even stop to reflect on what he’d done so at the next occasion he’d act just the same and expect Ele to forgive him again too because he’d have a precedent. Again, no two way communication in his imagination, Ele’d be talking but he wouldn’t be listening.

and even outside of the conversation Edoardo imagines, it’s not like he listens. He hears what she says, but he’s got his answers ready, he’s already thought out which objections Ele will bring and he’s prepared to answer

and, I mean, Ele isn’t listening either, she definitely thinks she’s in the right and she’s not open to seeing Edo’s point of view, but to be honest instead of explaining his reasoning he’s just listing excuses and putting words in her mouth

the Edoardo says that thing with the guys from piazza Giuochi were basically over and that no fight would have happened if Marti and Gio hadn’t “decided” to fight. So many problems in such few words. First off, things were not over with the Piazza Giouchi guys, they might have been nearly over in his opinion/from his POV, but look at the chronology:

Edoardo headbutted one of the Piazza Giuochi guys because he hit on Emma but she refused him so the guy called her a whore so Edo intervened

the Piazza Giuochi guys beat up Canegallo and Martucci while Edo was with Ele

two Piazza Giuochi guys got kicked out of the raffle party for starting shit & being homophobic to Marti

the Piazza Giuochi guys caught Gio and Marti alone, hit them, Edo & co went after them

so what I see is a sequence of revenges: the Villa guys win, the Piazza Giuochi guys win, the Villa Guys win, Piazza Giuochi guys try to even out the score. Did Edo honestly thinking that in a general climate of animosity the other guys would just accept being thrown out of a party, because of someone they view as inferior too, and not try to get retribution? Jajaja, que fun, as my queen Lydia Riera would say. Then of course he does the horrible thing of trying to place the blame of an homophobic attack on the victims, so he’s basically digging his own grave here. He backtracks immediately when Ele points out he’s victim-blaming and tries to talk about the experience, very close to her, of a gay person suffering what’s basically a hate crime.

and here’s another thing that bugs me immensely: he doesn’t let Ele speak. He interrupts her when she’s about to go on a rant about homophobia and victim-blaming, then he tells her she doesn’t listen, then when she asks him to listen to her he starts trying to interrupt her and one-up her raising progressively his voice till he’s screaming so loud he imposes himself and shuts her up. Probably because he seems scary and intimidates her into silence, especially when you think that just a couple of days prior she saw him destroy a wooden chair on a person’s back.

he actually yells, so loud it echoes, “Listen to me for a second!” when, honestly, he’s done nothing but talk up until now.

and finally we get to the crux of the matter: Edo doesn’t want to get a lecture from Eleonora. A lecture he knows is coming, one he has imagined and against which he’s probably prepared arguments, even, so much so that even if it came at this point he wouldn’t listen to a word because he’d be too wrapped up in his own retorts. But the retorts are not even necessary cause he’s so mad because of what he expects her to say he doesn’t even let her speak, just yells over her, to avoid that infamous lecture.

So really, he’s asking Ele to see things from his perspective, when he doesn’t want to do the same. A balanced discussion and relationship? We don’t know them.

btw, I personally feel like Eleonora in this instance would be more of the “cold shoulder” inclination, not of the yelling and lecturing inclination, but that’s me; I mean, she avoided his calls for almost two days, she didn’t even want to look at him today, so… (btw, at the beginning Edo tells Ele to stop avoiding looking at him, so he wants her attention on himself, but it has to be the exact kind of attention he wants, which is why he gives her a script of what he wants her to say in a fight and gets mad when she doesn’t adhere to it)

and like, Ele sees things only in black and white, very few shades of gray, lines firmly drawn and not to be surpassed, which means she’s not willing to compromise and that’s not good for communication, the negotiation of conflicts and ultimately relationships. But Edo is also very, very firmly attached to his own cynical vision of things and his Black and Grey Morality, where he gets away with ruthless actions because he’s on the good-but-imperfect side while the other side is much worse (the homophobic assholes of Piazza Giuochi, who are obviously Evil), there is no truly good side and evil is Inherent in the System, so e.g. the police is not a real solution or any help.

so then Edoardo resorts to the Jerk Justification of Appeal to Inherent Nature: that’s just him. Which Eleonora correctly read as an attempt to use the Freudian Excuse of his Dark and Troubled Past, but a Freudian Excuse Is No Excuse so she gives him a "The Reason You Suck" Speech that closely mimics the speech she gave him in ep. 7 season 1 “Ho fatto un casino” (all capitalised and italicized words refer to tropes as categorized by TV Tropes)

the last jab about playing the victim is hella mean, but he shouted her into shutting up so I think we’re mostly even, personally

how condescending is that ���You know, no-one is forcing you to be with me”? And it’s an ultimatum at the same time. Edo. Giving Ele a ultimatum. When he’s the one who has shown signs of violent behaviour.

the last look Ele gives Edo feels pretty pointed in my opinion, she’s telling him she’s not stupid and not to condescend her and yes, she’s perfectly aware she can not be with him, would he like if she actually decided not to be?, but the she breaks, opens her mouth to say something… and Edoardo stalks away, having already decided what she’s chosen to do without letting her speak

the poetic cinema of that last shot with Edo in black going one way and Ele with her bright white bag going the opposite way… kudos, Ludo

I’d also like to add that I’m struggling a bit this season. Too few clips, too few social media updates, it feels like I’m missing a huge part of the story (without even going in about Marti facing homophobia again and again and no way for us to see the consequences) and I can never understand Ele’s state of mind. I’m not into this season as much as I hoped I’d be.

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

You know, out of all the recurring characters from RDR, the ones with the biggest personality change is John and Javier. We see John slowly becoming the John we see in RDR thanks to the epilogue but I can't say the same for Javier. (Honestly it's just me not being able to accept the fact that this badass man that is just so loyal to the gang and always plays the guitar around the campfire whenever I'm in camp turn into that guy in RDR)

I can see both sides on this, Nonny. I do think Javier’s predestined fate from RDR1 definitely drove his story in RDR2, and I’m not sure that had it been an open sandbox storywise rather than a prequel, some things might not have been different. I could as easily have seen Javier standing with Arthur and John at the end.

However, I will also say I don’t see Javier’s choice to be OOC. Look, we adore Arthur. But objectively, you’ve got a man who’s incredibly faithful to those he loves, cares about people, tries to do the best he can for his gang family and keep their spirits up, and he does some really shitty things in the name of loyalty to that gang. He’s conflicted about it, yes, but he makes some terrible decisions nonetheless, particularly in how long it takes him to finally stand up to Dutch (and even in the end, he’s still trying to believe the best in Dutch, not the worst).

So I can easily see Javier having a similar experience. But unlike Arthur, he’s unable to get over the hump of blind loyalty. He hates what happens at Beaver Hollow, but he makes the only choice he believes he can make, to support the man to whom he believes he owes everything. John and Arthur are becoming people he doesn’t know and doesn’t understand anymore, and so he’s harsh and critical, because from Javier’s POV, they’re being negative and pulling the gang in different directions right when things are the most desperate.

And it’s hard to see that, because like with Arthur, we want the better angels to win. But for Javier, they don’t. And I think he knows that, and it’s part of why he becomes the man we see in RDR1, who’s given up his ideals and his principles to the point of becoming Assante’s hired thug when Assante is everything he once hated and fought against. He’s become a tool of oppression, not the revolutionary he once was.

It sounds like he laid low for a long while and joined Assante only in the past couple of years, so I have to think Dutch inevitably failed him too, and he spent some time after that feeling very lost. At this point, with the choices he’s made, he can’t see a way out. Like Arthur says, he probably feels like all he’s good for is riding, shooting, and killing.

I’d have to find video from RDR1 but I seem to remember while Javier’s position is a brutal one, he’s still fairly polite and cordial to John, so I don’t think he’s done a total 180. He’s just unfortunately given up on himself as anything more than a thug.

I’ve said before that I consider Arthur and Javier to be very similar men. Idealistic, artistic, caring, introspective. The crux of the matter is that Arthur makes the choice to embrace loyalty to his own sense of honor and duty and compassion first, and Javier sticks to blind loyalty to Dutch.

Although gotta say, thinking ahead to Sunrise and remembering there’s an option to bring Javier in alive in 1911 makes me wonder if there’s potential there. ;) He made a bad decision 12 years before and it’s cost him dearly, but if he somehow escapes prison, maybe it’s not too late? (After all, if there’s a reasonable chance to argue for Javier’s survival, particularly without totally breaking RDR1 canon, the implication that a white American man can redeem himself but a brown Mexican man is beyond saving is an uncomfortable one, let’s be real.)

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smoke in the Sun Review

5/5 stars

Recommended for people who like: fantasy, magic, Japanese folklore/fantasy, court intrigue, multiple POV, strong female leads

The two times I've read this, I've been wary going in, only to wonder why I felt that way when I finish. Maybe it's the threat of Mariko and Okami being in danger? Maybe it's the threat of a love triangle? The first one is obvious, of coursethey're in trouble in this one. A lot of it, actually. The second one takes a bit more time to work out, but for those of you who also aren't fans of the triangle, rest assured Ahdieh doesn't go in that direction. The closest she comes is with Tsuneoki loving Ranmaru/Okami, though he does it silently and without letting Okami know.

Throughout Smoke Mariko has to face a very different kind of battle than she did in Flame. Instead of disguising herself as a boy and fighting with fists and swords and inventions, Mariko has to disguising herself as a noble lady and fight with lies and being shrewd. She does still invent some things to try and help--after all, she's not going to leave Okami in prison if she can help it--but the majority of the book is comprised of her using the things the Black Clan has taught her to wage a covert battle against the royal family, of which she is supposed to become a part of.

Despite supposedly being uncomfortable with other noble women and having to converse, Mariko does quite well blending in with the other noble ladies. She has to do and say some things that chafe at her, but no one seems to really suspect her of being duplicitous...except maybe Raiden and Roku. She wins over Raiden for the most part, playing the part of a vulnerable, traumatized young woman. Roku, on the other hand, proves a more tricky player. It would be safe to say he falls into the 'Mad King' category, and he's definitely the up-front villain in this one. Aside from the trickery part of her story line, we also get to see how much Mariko has grown since the beginning of the first book. She takes care to learn the names of the people serving her, even befriending one of the younger ones, and also makes friends with a disgraced lady from court. At one point, we see this come to a crux when she and Kenshin have a bit of a spat and she tells him what she learned about their father and the other daimyos, which in turn makes him think about the same things Mariko has already realized.

Speaking of, Kenshin is still a frustrating character. I get that he's losing time, that he's being controlled by a magical being, but even when he is in control, he takes zero time and makes zero effort to try and understand Mariko or the things going on around him. In fact, he instead chooses to go to Hanami and drink himself into a stupor at Yumi's tea house--which is fortunate for Yumi and the Black Clan, even if it isn't for him. While he begins a redeeming himself toward the end of the book--in the last 100 or so pages, I believe--it's too little too late for Mariko and it's a bit too little too late for me. I think a large part about why I dislike his character is because I don't believe in blind obedience and the samurai code, the code Kenshin tries to follow, demands it, even when you know it's wrong. I do appreciate how Ahdieh showed the conflict in Kenshin. In Wrath, Shahrzad's father's redemption comes suddenly, but here, Kenshin's (and Raiden's) redemption happens over a period of chapters, starting with small actions. I think redemption arcs like this are important, especially when they're left open ended, because it shows people that redemption and forgiveness don't happen overnight, they take time and effort and can be painful. So while Kenshin isn't one of my favorite characters, he definitely has one of my favorite arcs.

Yumi is another sister that has to deal with brothers and redemption. We get to see a lot more of her in this one, she narrates a bunch of chapters, which I like. She's an intriguing character, especially if you read the short story Yumi. I like the message she espouses to Mariko about being a woman in Flame, and it's interesting to see how those thoughts coexist with her desire to do more for the Black Clan, to be included in the goings on. It was nice to see her take her fate into her own hands more in this story, going out and setting things in motion herself as she's wanted to for a while. She also offered an interesting dichotomy to Kenshin's interactions with people. When he's with Mariko he's angry and cold, but when he's with Yumi he's more open and vulnerable (and often drunk). But something about him lets Yumi understand he's been having difficulties and shows her being more forgiving toward him than Mariko. This, in turn, reflects back on how she interacts with her own brother. She still resents how he left her to languish for years, merely an information gatherer instead of a full Black Clan member, despite her abilities. That tension is still there, but she also gains the ability to see it from the outside after dealing with Kenshin and Mariko. Speaking of Mariko, their interactions were so pure. Both girls clearly respect one another and they're of very similar minds when it comes to their roles in society and their desire to help people, their friendship was lovely.

Ranmaru/Okami also gets his chapters in this one, though he's in prison for a lot of it. The transformation of him from devil-may-care to someone who is willing to lead is phenomenal. It happens slowly, like the redemption arcs that occur, and, in a way, Okami's arc is a version of the redemption arc. But he listens to what Mariko has to say about him, he listens to Tsuneoki, he begins ruminating over their words to him and, after a fortuitous visit to his mother's old land holdings, begins to see that he is, perhaps, the leader Mariko and Tsuneoki think he is. The way the other Black Clan members refer to him and respect him also seems to impact his decision a lot, especially when it comes to Ren, who doesn't seem to respect much at all. Despite taking on a more serious role, he keeps his humor throughout the story. I really liked how Ahdieh portrayed his love for Mariko. He is one of the few characters who sees, understands, and accepts her wholly for who she is. I absolutely loved the lines where he tells Mariko that she should be worshipped, but never the worshipper. *SPOLER* I also really liked their epilogue scene together, where Mariko proposes and asks if he minds her experimenting at all hours of the night, even when the experiments might scare him. Their interaction there was so cute and light. *SPOILER END*

Raiden also gets chapters in this one. He's another one, like Kenshin, who's conflicted throughout much of the book and undergoes a redemption arc, of sorts. He also, again like Kenshin, has this whole 'blind obedience' thing going on for a lot of the book. He loves his brother and is willing to serve him blindly, even if it means casting his own mother aside (not that she's a saint either, but still). He knows what Roku is doing is wrong, he sees the downward spiral his brother is in, and yet he lets it get to the point where Roku is torturing and killing people for fun and using the thin excuse of threats against the sovereign to justify it. Thankfully, Raiden ends up walking the line, following his brother while also using the orders he was given to help people. His speech to Mariko about not needing to be lectured by a woman rankled me, and Mariko too, but much like with Okami and Kenshin, her lecture made him think. His redemption is done slowly, piecemeal by piecemeal, starting with the few people he can save from his brother's descent into madness, and then escalating to doing what's right in straight defiance of his sovereign loyalties.

Kanako is another POV in this story. Despite what she's doing, despite her being the covert bad guy in this book, about halfway through, she stopped feeling like an evil character. It helps that Roku was off his goddamn rocker, but even with the stuff she did to the people of Inako and some of the supporting clans, I didn't hate her or dislike her character. She is kind to Mariko, even if she planned to kill her in the first book, and she loves her son, even if it causes her to do twisted things. I suppose, through the lens of these two people, and through an understanding of how right she is regarding Roku's inability to rule, Ahdieh has done an exemplary job of making the, potentially, worse of the two villains a sympathetic character.

Tsuneoki gets some chapters in this one as well, though far fewer than in the previous one, I feel. Despite his claims about Okami, he's still very much the leader of the Black Clan. I do wish we got to see more of him in this one, I feel like he was very much absent, and I would've liked to see more of his friendship with Mariko, the steps he takes to repair his relationship with Yumi.