#jane ussher

Text

One of the most common questions put to any feminist attempting to discuss women's experiences in a public forum is 'What about men?'. Any talk I have ever given about the psychology of women, or about women's madness, has invariably provoked such a response. One retort is that men have long been the (often sole) focus of interest for psychologists, and that researchers or theoreticians who exclude women from their analysis are never taken to task on the matter; they never have to justify their exclusion of women. In fact, one could posit that psychology has developed as a singularly male enterprise, with men studying men and applying the findings to all of humanity, and thus it is time to redress the balance. But I usually manage to confine myself to a less confrontational analysis - actually answering the question - even though I find it lamentable that it is the one most frequently asked. The answer is that men are 'mad' too; that men need help too; but that often men's madness takes a different form in our society. It may have different roots. It certainly exists within a different framework from that of women's madness, within a different discourse: it has a different meaning. One of the easiest ways of illustrating this is the argument that if you compare the statistics on psychiatric admissions, and those on female depression, with the statistics on prison populations, and on male violence and criminality, the scales are evenly balanced. So men may be mad - but are likely to be positioned as bad. They are likely to manifest their discontent or deviancy as criminals. Whilst women are positioned within the psychiatric discourse, men are positioned within the criminal discourse. We are regulated differently.

I will explore these arguments further in the analysis of why women are mad but I will leave the case of men here. Feminists should not have to justify their concentration on women. This does not necessarily mean a lack of interest in, or neglect of, men. But this is an analysis of women's madness, not of men's. And it is thus the experience of women that I shall focus on; in particular on the discourse associated with that women's madness which positions us and regulates our experiences. The research which merely describes or illustrates gender differences in madness, however it is manifested, is thus not the core of this debate. It merely provides an interesting set of validating evidence. We should not become enmeshed in the rigmarole of the sex differences research - research often carried out with little theoretical justification and no analysis of why it is being done, or by those desperate to prove 'the existence of the Other' through the establishment of difference (Walkerdine, 1990: 62). I wish to avoid the trap of the liberal feminists' examination of difference (or absence of difference) to prove equality by concentrating in this present analysis on the particular manifestation of madness in women, the reasons posited for its occurrence, and the way in which it is placed within the discourse which controls and confines our experience. Let the men dissect their own madness. I shall focus on women, with no apology!

-Jane Ussher, Women’s Madness: Misogyny or Mental Illness?

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taika Waititi photographed by Jane Ussher, 2007

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Libido is obviously affected by enjoyment. After menopause, the vagina shrinks and loses some elasticity (this is called atrophy), and along with vaginal dryness, this could cause pain during sex, which in turn could reduce libido. Jane Ussher points to studies of lesbians that show increased sexual enjoyment compared to heterosexual women at this stage of life because they were able to discuss their body changes more openly and negotiate different ways of pleasuring each other, ‘largely because they shared a broader definition of “sex” which wasn’t tied to penetration’.

Pain and Prejudice — Gabrielle Jackson

#Pain and Prejudice#Gabrielle Jackson#endometriosis#adenomyosis#women's health#female anatomy#female physiology#menstruation#menopause#hysteria#chronic pain#pelvic pain#autoimmune#chronic illness#disabled#perimenopause#atypicalreads#bipolar#BPD#borderline personality disorder#bi polar#mental illness#mental health#sexism#misogyny#negative#wlw#lgbtq

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Transgender Parent: Experiences and Constructions of Pregnancy and Parenthood for Transgender Men in Australia

The 2018 article about transgender men and gestational pregnancy by the authors Rosie Charter, Jane M. Ussher, Janette Perz, and Kerry Robinson goes over the experiences and thoughts of transgender men and pregnancy. Many transgender men do not desire pregnancy because it can be a very dysphoric period for them as they have to put a pause on their testosterone therapy. Even while being aware of this some trans men still desire pregnancy and parenthood as they see it as a “functional sacrifice”. It is important to note the article also delves into how healthcare systems are not generally supportive of trans bodies and identities and trans men encounter significant issues when interacting with healthcare providers. This brings to light the importance of inclusive and specialized health services to support trans men through pregnancy.

For this research article, the authors used a mixed-methods research design for this article. Which included using online survey data and one-on-one interviews, with 66 trans individuals, 25 were trans men, who had experienced a gestational pregnancy. The participants had gestational children ranging in age from 3 years to 12 years old. Twenty-four participants had one gestational pregnancy, and one participant had experienced two gestational pregnancies. The majority of participants also parented other children, whom they had not carried gestationally. Thus, only 25 trans men have experienced gestational pregnancy. The authors were able to analyze the data by using thematic analysis.

For many participants, the desire to become a parent was kindled when they came out as transgender or started transitioning. This shift of identity from “potential mother” to “potential father” was a powerful experience, giving many “a way to imagine parenting”. These accounts demonstrate the transformative power of coming out and transitioning, wherein participants renegotiated parenthood identities to bring them into alignment with their experiences of masculine gender. This shifting of identities facilitated the ability to challenge both personal and societal assumptions around their capabilities of parenthood. Future research must also include trans men who have not been able to conceive, which may be associated with access to services, in order to provide a more inclusive picture of trans men's experiences of their fertility and pregnancy. Additionally, it may provide further insight into ways in which the provision of fertility services and information can be improved for trans men, and the broader trans community, who remain largely underrepresented in reproductive health research.

0 notes

Text

Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body (Women and Psychology)

Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body (Women and Psychology)

Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body (Women and Psychology) Jane M. Ussher

Managing the Monstrous Feminine takes a unique approach to the study of the material and discursive practices associated with the construction and regulation of the female body. Jane Ussher examines the ways in which medicine, science, the law and popular culture combine to produce fictions…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Super stoked to reveal Good magazine’s latest cover featuring the vibrant and witty Wendyl Nissen photographed by Jane Ussher. Super proud of this issue which is packed full of practical tips, insightful features and inspirational people. Don’t forget to grab a copy! 💚 #goodmagazinenz https://www.instagram.com/p/Ci0mOTgP1ur/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Jane M. Ussher, “Woman as Object, Not Subject: Madness as Response to Objectification and Sexual Violence,” in: The Madness Of Women: Myth and Experience

143 notes

·

View notes

Photo

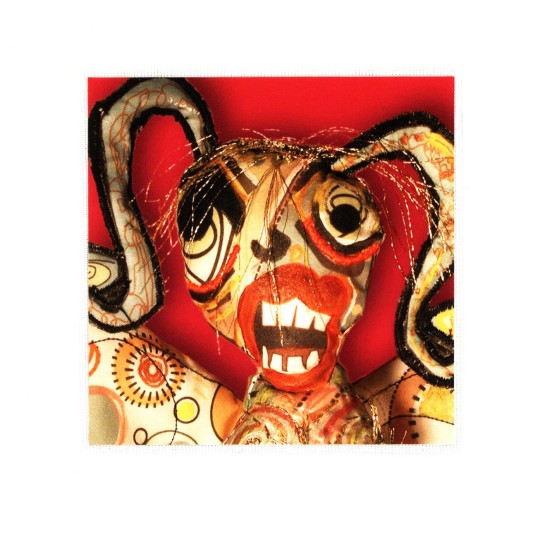

Spotlight: #LISMentalHealth week and Hysteria

February 17th-23rd is LIS Mental Health Week, which aims to raise awareness of mental health among library and archives workers. To that end, I’ve scoured Special Collections for the resources to help us all learn more about our own mental health. Today I am featuring, Hysteria: An Anthology of Poetry, Prose, and Visual Art on the Subject of Women's Mental Health.

This book was conceived of and edited by Jennifer Savran, designed by Keren Cohen, and includes the work of over 30 authors and artists. It was published in 2003 by Savran’s LunaSea Press, whose mission it is to publish "limited edition hand-bound books that focus on women's issues and to donate proceeds from sales to organizations that assist women in need." The proceeds from Hysteria went to MADRE.

The poems, prose, and art within Hysteria deal with both the experiences of women who are affected by mental illness but also the problems within our society that lead to the increased prevalence of mental health issues within women. The artists and poets not only reflect on the experience of mental illness but also deconstruct women's madness as a concept and critique "institutionalized investigations and interventions."

Jane M. Ussher’s introductory essay, titled "Understanding Women's Madness: Listening to Women," is a thought-provoking piece on the historic and symbolic relationship between womanhood and madness and misguided medical interventions.She warns: "To be woman is to be mad—in today's world, at risk of falling into the abyss of psychiatric diagnoses control.... Women's madness has clearly moved from mythology to mass industry. No longer a mystery, we are assured that it can be categorized, contained and cured."

The book was published in 2 limited editions: a hand-bound cloth edition of 100 and a paper edition of 150. Our copy is #28 of the cloth edition and is signed by Jennifer Savran.

-Katie, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#fine press books#lismentalhealth#Spotlight#Katie#mental health awareness#women activists#activist art#LIS Mental Health Week#Hysteria#Jennifer Savran#Keren Cohen#LunaSea Press#MADRE#@mindfulinlis

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

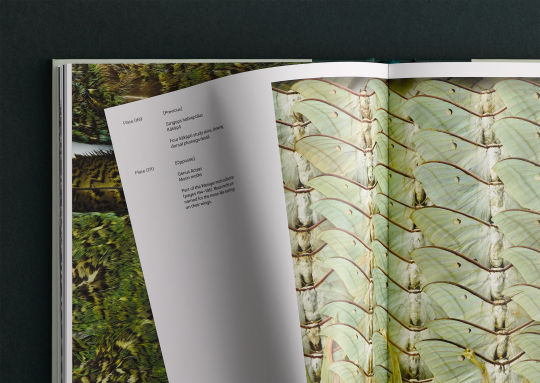

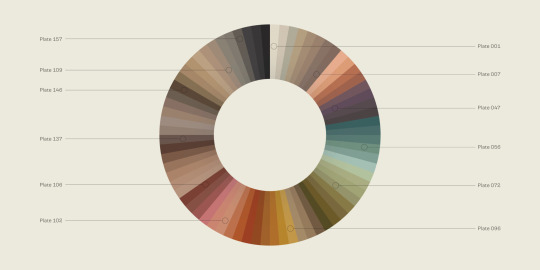

Inhouse 78 Nature Stilled

The concept of this book as fascinating as photographer Jane Ussher spent weeks photographing images of insects, molluscs, fish and other botanical specimans that were stored in the Natural history collection at Te Papa.

Instead of presenting them in their obvious categories, she displayed and categorised them herself acording to colour. Each of her images was a colour swatch and this became part of her colour wheel.

To Ussher, it was not just about photographing the stored sepcimans (that she was unable to touch), she wanted to know the stories behind each and every speiman so spent weeks discussing with the curators of the museum so she could learn the stories behind each and every piece.

What is so interesting and what I admire about what Ussher acieved here is that she made the colour wheel concept her design system and overall theme of her book.

MacDonnell, Arch. “Inhouse Nature Stilled”. Best Awards. Retrieved from https://bestawards.co.nz/graphic/editorial-and-books/inhouse/nature-stilled/

Phillips, Nicole. “Design & Books… Nature—Stilled”. Design Assembly. Retrieved from https://designassembly.org.nz/2020/10/23/design-books-nature-stilled/

0 notes

Text

The images of woman as object, not as active agent or creative autonomous subject, ensure that women remain on the outside, that women's voices are not heard. As history describes the doings of men, as fine art is the art created by men, as literature is writing produced by men, and as classical music is that composed by men, so the science, the news, the art, the literature, the music of today is that produced by men. The patriarchs are adamant that this should be so. The conductor, Sir Thomas Beecham, pronounced, “There are no women composers, never have been, and never will be.” John Ruskin confidently declared “No woman can paint.” And Swinburne claimed that, “When it comes to science we find women are simply nowhere. The feminine mind is quite unscientific.” Virginia Woolf's ponderings on the (im)possibility of ‘Shakespeare's sister’ who might have wanted to write, characterize the position of women in the creative sphere. As Tillie Olsen illustrates, in her now classic text, Silences, woman's voice has been absent from the world's creative arena for centuries. Unfortunately, it seems as if it still is.

But why are women so silent in the scientific, professional or creative spheres of life? The traditional reductionist argument, rehearsed earlier, is that women are somehow unable to think, to paint, or to write because of affinity with nature and lack of intellect. Or is it rather that we are not allowed to, through the systematic exclusion of women's work in the public sphere, or through the maintenance of women's work in the home the maintaining of women as servers, as the 'angel in the house', rather than as active creators of artistic discourse? Is it that women are producing creative material, but it is being systematically ignored? For there are many who profit from the reification of the male creator and the simultaneous reduction of women's creativity to the sphere of childbirth, as this extract from a misogynistic male critic illustrates:

A few years back I read a neo-feminist's approving review of another neo-feminist's book. The reviewer said that she agreed with the author that for a woman, a career is more creative than being a mother. That puzzled me: without having given much thought to it, I had assumed that about the closest the human race can get to creation is when a woman bears a child, nurtures him, and cares for him [sic]. (Himmelfarb, 1967: 59; my emphasis)

If women can believe that childbirth is unsurpassable as a creative act, perhaps they will put down their pens and their paints, cease thinking and continue breeding. Is it a coincidence that the male pronoun is used to refer to the product of female creativity? Is it as creative to produce a female child? Or is this yet another comment produced without having given much thought to it?

The reason for women's absence on the world stage of creativity is not biological inferiority, nor an absence of desire to create beyond the realms of the family. The real reasons for the silence are not very difficult to discern; nor are the effects. Take the case of art, as many feminist scholars recently have, rewriting the history of art through a feminist prism. Our Old Masters and masterpieces - the art which fetches astronomical prices, elevating the artist to an almost godlike status, his creativity seen to be drawn from some higher power - are all the work of men. The history of art is peopled with men, not women. The male artist is the hero; the female artist is invisible. The woman is present only as the object of the artist's gaze, to be consumed, to be frozen and framed, to be possessed. Feminist analysis has identified the way in which women's voices and women as active agents have been suppressed; the way in which women are destined 'to be spoken' (in Lacanian terms) rather than to speak. It is the same process that silences talent, as recent texts on the 'forgotten' women artists, scientists, or authors has shown. It is produced by a systematic suppression - a systematic oppression - achieved by promoting and validating the work of men whilst ignoring, or denying the existence of, the work of women.

Whilst women writers from Aphra Behn to Mary Wollstonecraft have been rediscovered by feminist literary scholars and feminist publishers, many others have not. Many women never had the time or opportunity to publish - and their voices will never be heard. Many women remain silent, following in the painful footsteps of our foremothers who never have the time or legitimacy for reflection and creation. It is moving to consider how many brilliant voices have not been heard, how many brilliant careers have been thwarted. As Olive Schreiner reflected:

What has humanity not lost by suppression and subjection? We have a Shakespeare; but what of the possible Shakespeares we might have had who passed their life from youth upward brewing currant wine and making pastries for fat country squires to eat, with no glimpse of freedom of the life and action necessary even to poach on deer in the green forests; stifled out without one line written, simply because of being the weaker sex, life gave no room for action and grasp on life?

In addition to marginalizing women, and ensuring that we cannot find a voice with which to declare our anger, our desperation, or our fears, the images can be seen to have a more invidious function in that they objectify women. They ensure that we have few role models to turn to for inspiration. We expect to be confined and constricted. We expect to serve men. Is it any wonder that we despair, that we cry out, that we are mad? And if the woman herself was not treated as mad for daring to be creative, she may have been driven so by the restrictions upon her. It is an insidious double bind: women who do attempt to create may be vilified for their talent, and for their temerity in daring to speak out. Whether a woman's creativity is an expression of inner conflict and turmoil, or merely a desire for self-expression, it is in danger of becoming the tool which condemns, a centuries-old process, as Virginia Woolf eloquently shows:

.. any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed, shot herself, or ended her days in some lonely cottage outside the village, half witch, half wizard, feared and mocked at. For it needs little skill in psychology to be sure that a highly gifted girl who had tried to use her gift for poetry would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity to a certainty. (Woolf, 1928: 48)

The feminist martyrs, diagnosed as mad, 'treated' by patriarchal experts, and (often) destroyed by their own hands, have fuelled arguments that madness is protest, an expression of thwarted creativity. And within a culture which refuses to recognize women's creativity (except in the area of motherhood) it is argued that its frustration leads to madness. Phyllis Chesler opens her book, Women and madness, with a testimonial to four such women, Elizabeth Packard, Ellen West, Zelda Fitzgerald and Sylvia Plath. In her description of their madness as 'an expression of female powerlessness and an unsuccessful attempt to reject and overcome this state', Chesler argues that the experiences of these women symbolize the oppression of women's power, women's creativity - an oppression with fatal consequences (Chesler, 1972: 16). Her argument - that the inability of these women to express themselves, their silencing by men, has led to their madness and their suicide - has obviously struck a chord in the hearts and minds of many women. Their icons and heroines are women like Sylvia Plath, women seen as victims of the individual men who thwarted their intellect, as well as victims of a society which sees women, not as active subjects, but as objects. When we read Plath's words, ‘Dying/Is an art, like everything else./I do it exceptionally well,’ a chill hand clutches the heart: although many would like to emulate her creativity, they fear the fate that befell her. We must, however, be careful not to glorify these women, raising them to the status of martyrs, for, as Tillie Olsen demonstrates, suicide is rare among creative women. What is undoubtedly more common is the slow creeping frustration, the inability to think, to breathe, to work at anything other than the daily grind. For women's creativity is not frustrated only by the structural barriers provided by the male-dominated academies and universities, and the male publishing houses, but also by the lack of time. For if male writers such as Hardy, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Joseph Conrad can share this experience described by Conrad, how must it be for the woman whose main task is the care of her children, her husband, her home?

I sit down religiously each morning, I sit down for eight hours, and the sitting down is all. In the course of that working day of eight hours I write three sentences which I erase before leaving the table in despair.

It is no coincidence that 'in our century as in the last, until very recently, all distinguished achievement has come from childless women' (Olsen, 1978: 31). How many women can find time to await the visit of the muse in moments snatched between children and housework? It is a wonder that Jane Austen managed to write - hiding her papers under a blotter in her parsonage drawing room - by snatching a few lines, a few thoughts, when the scarce moments of solitude were upon her. How many others must have given up, despairing, angry and defeated?

Even those women who manage to ward off the angel in the house, and can find a room of their own, may be remembered chiefly for aspects of their personal lives, their work forgotten, and their creativity reduced to voyeuristic intrusions on their sexuality. As French says:

Whether a woman had a sex life, what sort of sex life it was, whether she married, whether she was a good wife or a good mother, are questions that often dominate critical assessment of female artists, writers and thinkers. (French, 1985: 97)

The critics who pore over men's work with an academic glee, hardly noticing their personal lives, seem unnaturally interested in the woman creator's personal habits and especially in her sexuality. This allows the creative woman to be presented as unbalanced, unnatural, and certainly not representative of women. Thus, 'Harriet Martineau is portrayed as a crank, Christabel Pankhurst as a prude, Aphra Behn as a whore, Mary Wollstonecraft as promiscuous' (Spender, 1982: 31). Sylvia Plath, one of the foremost creative women of the late twentieth century, has been similarly treated. Biographers, commentators and critics seem more interested in her adolescent sexuality, her relationships with men during her college years, and her marriage, than with her work.

That a woman who produced brilliant poetry could also be sexual is seen to be a peculiarity. That she killed herself allows her to be seen as mad, and thus as not a normal woman. This over-concern with her sexuality and sanity detracts from her work, and is an insult to this gifted poet, and to others who might follow her. The message to women is clear - dabble with the muse, attempt to enter the male world of learning, of thinking, of creativity, and you may pay the highest price.

-Jane Ussher, Women’s Madness: Misogyny or Mental Illness?

#jane ussher#female artists#female mental health#female oppression#female erasure#female creativity#female voice

51 notes

·

View notes

Video

“The pregnant body was also profoundly contradictory: as scholar Jane Ussher explains, pregnancy is, at its most essential, the most vivid proof of women’s sexuality —which is precisely why representations of mothers took on the opposite characteristics.”

The pregnant body was also profoundly contradictory: as scholar Jane Ussher explains, pregnancy is, at its most essential, the most vivid proof of women’s sexuality — which is precisely why representations of mothers took on the opposite characteristics. The most significant mother of Christianity, for example, is the Virgin Mary: asexual, idealized, immaculate. Mary is rarely represented while actually pregnant, only afterwards, when the child is safely born, both mother and child clean and content. This beatific mother is contained, pure — the antidote to the abjectly pregnant mother. Historically, the easiest way to contain that abjection was to keep the pregnancy out of sight. Women of a certain class often receded entirely from public view until after the baby was born and the visible signs of pregnancy had diminished. When the birth occurred, it happened in the domestic space and was managed by midwives. Like all things hidden for fear of abjection (women’s sexuality, menstrual periods, feces), it became societally unacceptable to even speak openly of pregnancy: according to historian Carol Brooks Gardner, in nineteenth--century America “talk of pregnancy was forbidden even between mother and daughter, if either hoped to claim breeding and gentility.” Colloquialisms were developed to refer tactfully to the obscenity of a woman’s condition: she was “with child” or “in a family way,” never “pregnant.” —Anne Helen Petersen

www.buzzfeed.com/annehelenpetersen/how-kim-kardashian-pus...

1 note

·

View note

Text

From the moment she’s old enough to understand, almost every girl is taught that it’s her role to be a pleasure giver—after all, what does pleasure have to do with herself?

In Down Girl, Manne explains how society raises human beings, ‘white men who are otherwise privileged in most if not all major respects’, and human givers, ‘a woman who is held to owe many if not most of her distinctively human capacities to a suitable boy or man, ideally, and his children as applicable’.8 From the youngest possible age, girls are trained to give their full humanity: ‘A giver is then obligated to offer love, sex, attention, affection, and admiration, as well as other forms of emotional, social, reproductive, and caregiving labor’, writes Manne. Meanwhile, boys are raised to express their full humanity, to be competitive, inquisitive, autonomous, to do whatever it takes to be fulfilled—they are human beings.9 Manne’s book is one that Emily Nagoski—an American author, sex educator and former Kinsey Institute researcher—tells me that she can’t stop talking about. ‘So,’ she says, ‘if we raise our children within this dichotomy of human givers and human beings, then of course by the time they get to a place where they’re having sex with each other, who’s going to have sexual pleasure? Who’s going to do the giving? And who’s going to do the receiving? There is a really straightforward narrative in place for them already—that narrative is reinforced by all of the porn they watch, it’s reinforced by everything their parents are talking to them about. And it’s reinforced by the actual experiences that they have.’

Likewise, in The Madness of Women, Jane Ussher explains that because ‘women are taught to believe that they are not loved for who they are, but for how well they meet the needs of others’,10 they learn to silence their desires and feelings. The widespread cultural standards imposed on women of ideal femininity also leave many women in a constant state of self-judgement, ‘leading to feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness’.11

These cultural messages are mixed in with those received at school, home and possibly church, that sex is dirty, disgusting and dangerous—but also something a woman should give to a man she loves, and if she’s not good at it no one will love her. Confusing, right?

Pain and Prejudice — Gabrielle Jackson

#Pain and Prejudice#Gabrielle Jackson#endometriosis#adenomyosis#women's health#female anatomy#female physiology#menstruation#menopause#hysteria#women pain#IBS#migraine#pelvic pain#PCOS#autoimmune#chronic illness#disabled#perimenopause#atypicalreads#bipolar#BPD#borderline personality disorder#bi polar#mental illness#mental health#sexism#misogyny#negative

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography

Webster, Cecil R., and Cynthia J. Telingator. 2016. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Families.” Pediatric Clinics of North America 63(6):1107–19. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.010).

Carroll, Megan. 2018. "Gay Fathers on the Margins: Race, Class, Marital Status, and Pathway to Parenthood." Family Relations 67(1):104-117. (https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12300.)

Goldberg, Abbie E. and Katherine R. Allen. 2007. “Imagining Men: Lesbian Mothers’ Perceptions of Male Involvement during the Transition to Parenthood.” Journal of Marriage and Family 69(2):352–65. (https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00370.x)

Goldberg, Abbie E., Katherine R. Allen, and Megan Carroll. 2020. “‘We Don’t Exactly Fit in, but We Can’t Opt out’: Gay Fathers’ Experiences Navigating Parent Communities in Schools.” Journal of Marriage and Family 82(5):1655–76 (https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12695)

Charter, Rosie, Jane M. Ussher, Janette Perz, and Kerry Robinson. 2018. “The Transgender Parent: Experiences and Constructions of Pregnancy and Parenthood for Transgender Men in Australia.” International Journal of Transgenderism 19(1):64–77. (https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.unlv.edu/10.1080/15532739.2017.1399496)

Cahill, Sean. 2008. “The Disproportionate Impact of Antigay Family Policies on Black and Latino Same-Sex Couple Households.” Journal of African American Studies 13(3):219–50. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-008-9060-7)

Stolk, T. H., E. van den Boogaard, J. A. Huirne, and N. M. van Mello. 2023. “Fertility Counseling Guide for Transgender and Gender Diverse People.” International Journal of Transgender Health 24(4):361–67. (https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.unlv.edu/10.1080/26895269.2023.2257062)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ancient Greek Monsters

Sources:

Boddens-Hosang, F. J. E. and Carole d’Albiac. "Sphinx." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed April 6, 2017, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T080560.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. Monster Theory: Reading Culture. University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths, Baltimore: Penguin, 1955.

J.E. Robson, “Bestiality and Bestial Rape in Greek Myth.” In In Rape in Antiquity, edited by Susan Deacy and Karen Pierce, London: Duckworth in Association with the Classical Press of Wales, 1997.

Lestel, Dominique. "Why Are We So Fond of Monsters?" Comparative Critical Studies 9, no. 3 (2012): 259-69.

Low Schmitt, Marilyn. "Bellerophon and the Chimaera in Archaic Greek Art" American Journal of Archaeology 70.4 (October 1966), pp. 341–347.

Padgett, Michael J. The Centaur’s Smile: The Human Animal in Early Greek Art. Yale University Press New Haven and London, 2004.

Rabel, Robert J. 1948-. "The harpies in the Aeneid." Classical Journal 80, (April 1985): 317-325. Art & Architecture Source, EBSCOhost (accessed April 6, 2017).

Rose, Carol. Giants, Monsters, and Dragns: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2001.

Scobie, Alex. "The Origins of 'Centaurs'" Folklore 89.2 (1978:142–147); Scobie quotes Martin P. Nillson, Geschichte der griechischen Religion, 1955, "Die Etymologie und die Deutung der Ursprungs sind unsicher und mögen auf sich beruhen".

Smith, Cecil. "Harpies in Greek Art." The Journal of Hellenic Studies 13 (1892): 103-14. doi:10.2307/623895.

Ussher, Jane. Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body. London: Routledge, 2006.

Wilk, Stephan R. Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Links:

http://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/KentauroiThessalioi.html

Listen to Full Episode Here

Subscribe on iTunes

#sources#research#ancient greek monsters#ancient greece#ancient greek art#monsters#centaurs#sirens#harpies#sphinx#greece#art#podcast#art history#art history babes#art history babes podcast

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jane M. Ussher, Diagnosing difficult women and pathologising femininity: Gender bias in psychiatric nosology, 23 Feminism & Psychology 63 (2013)

The genealogy of women’s madness

The pathologisation of femininity and regulation of ‘difficult’ women through psychiatric nosology has a long history. If we look to accounts of hysteria, the most commonly diagnosed ‘female malady’ of the 18th and 19th century, we can trace the genealogy of the ‘regimes of truth’ reified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), which define and regulate women’s madness today. Whilst hysteria was first described by the ancient Greeks, appearing in the writings of Plato and Hippocrates, it was in the 17th century that it emerged as one of the most common diseases treated by medics. Thus Thomas Sydenham commented that ‘the frequency of hysteria is no less remarkable than the multiformity of the shapes which it puts on. Few of the maladies of miserable mortality are not imitated by it’ (Sydenham, 1679: 85). Although the causes of this nebulous disorder were widened to include the nervous system in the late 18th century, allowing men to receive a diagnosis of hysteria (Showalter, 1997:15), it was always considered to be ‘woman’s disease’, a disorder linked to the essence of femininity itself. Indeed, Laycock (1840), described hysteria as a woman’s ‘natural state’, whereas it was deemed a ‘morbid state’ in a man (Smith-Rosenberg, 1986: 206), and in 1903 Otto Weininger asserted that ‘hysteria is the organic crisis of the organic mendacity of woman’ (Bronfen, 1998:115).

The 19th-century physicians were highly critical of this feminine ‘state’ describing hysterical women as difficult, narcissistic, impressionable, suggestible, egocentric and labile (Smith-Rosenberg, 1986: 202). The affluent hysteric was characterised as an idle, self-indulgent and deceitful woman, ‘craving for sympathy’, who had an ‘unnatural’ desire for privacy and independence (Donkin, 1892) and was ‘personally and morally repulsive, idle, intractable, and manipulative’ (Showalter, 1987: 133). Some went as far as to describe such women as ‘evil’, with the physician Silas Weir Mitchell, declaring that ‘a hysterical girl is a vampire who sucks the blood of the healthy people around her’ (Mitchell, 1885: 266). In contrast, women suffering from the ‘nervous disorder’ of neurasthenia, which shared many of the symptoms of hysteria, yet was characterised by an ‘ill defined set of symptoms – a form of nervous exhaustion’ (Busfield, 1996: 130), were described as having a ‘refined and unselfish nature’, and as being ‘just the kind of woman one likes to meet’ (Showalter, 1987: 134). Neurasthenic women were ‘sensible, not over sensitive or emotional, exhibiting a proper amount of illness. . .(with) a willingness to perform their share of work quietly and to the best of their ability’, in the words of one 19th-century physician (Playfair, 1892: 851). Politeness and compliance on the part of the patient was clearly of the essence, as is still the case today, when ‘difficult’ women are at risk of being diagnosed with borderline personality disorder or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

By the late 19th-century, as Rosenberg has argued (1986: 202), ‘every known human ill’ was attributed to hysteria, meaning that the diagnosis ceased to mean anything at all (Micale, 1995: 220). Women diagnosed with hysteria could exhibit symptoms of depression, rage, nervousness, the tendency to tears and chronic tiredness, eating disorders, speech disturbances, paralysis, palsies and limps, or complain of disabling pain. Many women also exhibited a hysterical ‘fit’, which could either come on gradually or could occur suddenly, mimicking an epileptic seizure (Smith-Rosenberg, 1986: 201). Indeed, hysteria has been described as a ‘veritable joker in the taxonomic pack’ (Porter, 1993: 226), and as the ‘wastebasket of medicine’ (Bronfen, 1998: xi) largely because of its nebulous and multifarious nature. Hysteria has also been described as a ‘mimetic disorder’ because it mimics culturally permissible expressions of distress – hysterical limps, paralyses and palsies were accepted symptoms of illness in the 19th century, but have virtually disappeared today, as they no longer stand as a ‘sickness stylistics for expressing inner pain’ (Porter, 1993: 229).

At the beginning of the 21st century the ‘legitimate’ symptoms of madness are laid out for all to see in the DSM. As new diagnoses are added with each edition (and others, such as hysteria or homosexuality, removed), details of the necessary symptoms for diagnosis are circulated through interactions with the psyprofessions, or through pharmaceutical company advertising, media discussion of madness, and ‘self-help’ diagnostic websites. Is it surprising that so many women self-diagnose with these disorders and then come forward for professional confirmation of their pathological state? Their distress is no less real than that of the women diagnosed as hysterics in the 19th century. However, the myriad disorders with which we are now diagnosed are no less mimetic than hysteria was then – we signal our psychic pain, our deep distress, through culturally sanctioned ‘symptoms’, which allows our distress to be positioned as ‘real’. Or we are told by others that we have a problem, and are then effectively positioned within the realm of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, with all the regulation and subjugation that this entails (Ussher, 2011). Femininity is still central to this process, as is evidenced by the diagnosis of the modern ‘female maladies’, hysterical and borderline personality disorders, and PMDD.

Exaggerated femininity: Hysterical and borderline personality disorders

Hysterical personality disorder’s depiction in the DSM-II, published in 1968, has been described as ‘essentially a caricature of exaggerated femininity’ (Jimenez, 1997: 158), as the ‘symptoms’ included excitability, emotional instability, over-reactivity and self-dramatisation. Indeed the description in DSM-II of hysterics as ‘attention seeking, seductive, immature, self-centred, vain . . . and dependent on others’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1968: 251) is almost identical to the 19th-century description of hysteria. In DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), published in 1980, hysterical personality disorder was renamed ‘histrionic personality disorder’, to avoid the negative connotations that were associated with ‘hysteria’ (Jimenez, 1997). However, the descriptors of the typical patient outlined in DSM-III still depict an exaggerated femininity, someone who is ‘typically attractive and seductive...overly concerned with physical attractive- ness’ as well as interested in ‘control(ling) the opposite sex or enter(ing) into a dependent relationship (and continuously demanding) reassurance, approval or praise’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1980: 348). Isn’t this how we are taught to ‘do girl’ through teenage magazines, romantic fiction, and ‘chick flicks? (Ussher, 1997). But we should be careful. Enacting this particular version of ‘seductive’ femininity may attract more than a man – it can also clearly attract a psychiatric diagnosis. This was evidenced in a study where psychiatrists were asked to judge a range of case descriptions, wherein a diagnosis of histrionic personality disorder was given to women, even though the case studies gave little indication of the ‘disorder’ (Loring and Powell, 1988).

Changes in gender roles after the 1960s and 1970s, which saw Western women enter the workforce in unprecedented numbers, and reshaped sexual and family relations, resulted in the marginalisation of hysteria as a diagnostic category. However, as Jimenez (1997: 161) has argued, this did not mean that exaggerated femininity was no longer pathologised, as borderline personality disorder simply took the place of hysteria, capturing ‘contemporary values about the behaviour of women’. Borderline Personality Disorder is described as a ‘feminised’ psychiatric diagnosis (Becker, 1997), because it is applied more often to women than men, at a rate of 3:1–7:1 (Becker, 2000). The criteria for diagnosis consists of symptoms that characterise ‘feminine qualities’ (Jimenez 1997: 163). These include depression and emotional lability, as well as ‘impulsiveness in areas such as shoplifting, substance abuse, sex, reckless driving, and binge eating’, and ‘identity disturbance’, evidenced by ‘uncertainty about self-image, sexual orientation, long term goals or career choice’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1987: 347). However, where borderline personality disorder differs from hysteria (or histrionic personality disorder) is the inclusion of the more masculine characteristic of ‘inappropriate intense anger’ as a criterion for diagnosis (Jimenez, 1997). So whilst both diagnostic categories adopt gender stereotypes in positioning particular women as ‘mad’, Jimenez comments, ‘if the hysteric was a damaged woman, the borderline woman is a dangerous one’ (p. 163). As almost half of the women who qualify for a histrionic or a borderline diagnosis meet the criteria for both disorders (Becker, 2000), many women are clearly seen as both damaged and dangerous.

The typical borderline patient has been described as a ‘demanding, angry, aggressive woman’, who is labelled as ‘mentally disordered’ (Jimenez, 1997: 162, 163) for behaving in a way that is perfectly acceptable in a man. Evidence that there is a clear gender difference in the pathologisation of emotions, in particular anger, is supported by recent research by Lisa Feldman Barrett and Eliza Bliss-Moreau, who examined judgements made about emotions expressed by men and women. They found that men’s sadness and anger was considered to be related to situational factors – such as ‘having a bad day’ – whereas sad or angry women were judged as ‘emotional’ (Barrett and Bliss-Moreau, 2009). Thus women’s emotions are deemed a sign of pathology, whereas men’s are understandable. Dana Becker has described borderline personality disorder as ‘the most pejorative of personality labels’ which is ‘little more than a shorthand for a difficult, angry, female client certain to give the therapist countertransferential headaches’ (Becker, 2000: 423). As many women diagnosed as ‘borderline’ have been sexually abused in childhood (Ussher, 2011), their anger is understandable, as is their ‘difficulty’ with men in positions of power over them – the therapists who give out diagnoses. These women are pathologised, occupying the space of the abject, that which is ‘other’ to all that is desired in the feminine subject (Wirth-Cauchon, 2001).

Menstrual madness: Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

The same could be said of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), another example of the positioning of ‘difficult women’ as mad (Chrisler and Caplan, 2002; Ussher, 2006). Women who report a range of feminised psychological changes premenstrually, primarily anxiety, tearfulness, and depression, can be diagnosed as having PMDD – as can women who contravene idealised femininity through ‘symptoms’ of anger and irritability. The fact that these ‘symptoms’ are often experienced in a relational context, as a reaction to over-responsibility and absence of partner support (Ussher and Perz, 2012), and take the form of a rupture in the self-silencing, which is practiced for 3 weeks of the month (Ussher and Perz, 2010), is completely absent in bio-medical accounts of PMDD.

Whilst a ‘mood disorders work group’ is ‘accumulating evidence’ as to whether PMDD should be included in DSM-5 (Fawcett, 2010), its inclusion in the DSM-IV met with widespread feminist opposition, on the basis that there is no validity to PMDD as a distinct ‘mental illness’ (Cosgrove and Caplan, 2004). Feminist critics have dismissed this process of pathologisation, arguing that premenstrual change is a normal part of women’s experience, which is only positioned as ‘PMDD’ because of Western cultural constructions of the premenstrual phase of the cycle as a time of psychological disturbance and debilitation (e.g. Chrisler and Levy, 1990; Rodin, 1992). In Eastern cultures, such as Hong Kong or China, where change is accepted as a normal part of daily existence (Epstein, 1995), women report premenstrual water retention, pain, fatigue, and increased sensitivity to cold, but rarely report negative premenstrual moods (Chang et al., 1995; Yu et al., 1996). This has led to the conclusion that PMS is a culture-bound syndrome (Chrisler and Johnston-Robledo, 2002) that follows unprecedented changes in the status and roles of women in the West, with the belief that women are erratic and unreliable premenstrually serving to restrict women’s access to equal opportunities (Chrisler and Caplan, 2002). Indeed, belief in the negative influence of premenstrual ‘raging hormones’ has been used to prevent women being employed as pilots (Parlee, 1973), physicians, and presidents (Figert, 2005), which by extension casts doubt on the reliability of all women occupying positions of responsibility.

Conclusion

As the outspoken, difficult woman of the 16th century was castigated as a witch, and the same woman in the 19th century a hysteric, in the late 20th and 21st century, she is described as ‘borderline’ or as having PMDD. All are potentially stigmatising labels. All are irrevocably tied to what it means to be ‘woman’ at a particular point in history. And whilst the 19th-century hysteric was deemed labile and irresponsible, as a justification for subjecting her to the bed rest cure or incarceration in an asylum (Ussher, 2011), women diagnosed as borderline today are often considered to be mentally disabled, subjected to involuntary institutionalisation or medication, as well as being stripped of child custody or parental rights (Becker, 2000: 429), and women diagnosed with PMDD are medicated with SSRIs (Steiner and Born, 2000). At the same time, a diagnosis of borderline can be used as a justification for denying women access to mental health care, because of supposed ‘resistance’ to treatment (Morrow, 2008). However, if we examine the negative consequences of contemporary bio-psychiatric ‘treatment’ for many women (Currie, 2005; Ussher, 2011), this may not be such a bad thing.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1968) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, edition iii. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, edition iiir. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, edition iv. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Barrett LF and Bliss-Moreau E (2009) She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day: Attributional explanations for emotion stereotypes. Emotion 9(5): 649–658.

Becker D (1997) Through the Looking Glass: Women and Borderline Personality Disorder. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Becker D (2000) When she was bad: Borderline personality disorder in a posttraumatic age. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70(4): 422–432.

Bronfen E (1998) The Knotted Subject: Hysteria and Its Discontents. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Busfield J (1996) Men, Women and Madness: Understanding Gender and Mental Disorder. New York: New York University Press.

Chang AM, Holroyd E and Chau JP (1995) Premenstrual syndrome in employed Chinese women in Hong Kong. Health Care for Women International 16(6): 551–561.

Chrisler JC and Caplan P (2002) The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde: How PMS became a cultural phenomenon and a psychiatric disorder. Annual Review of Sex Research 13: 274–306.

Chrisler JC and Johnston-Robledo I (2002) Raging hormones?: Feminist perspectives on premenstrual syndrome and postpartum depression. In: Ballou M and Brown LS (eds) Rethinking Mental Health and Disorder: Feminist Perspectives. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 174–197.

Chrisler JC and Levy KB (1990) The media construct a menstrual monster: A content analysis of PMS articles in the popular press. Women and Health 16(2): 89–104.

Cosgrove L and Caplan PJ (2004) Medicalizing menstrual distress. In: Caplan PJ and Cosgrove L (eds) Bias in Psychiatric Diagnosis. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc., pp. 221–232.

Currie J (2005) Women and health protection. vol. 2009. Available at: http://www.whp- apsf.ca/pdf/SSRIs.pdf.

Donkin HB (1892) Hysteria. In: Tuke DH (ed.) Dictionary of Psychological Medicine. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, pp. 619–621.

Epstein M (1995) Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. New York: Basic Books Inc.

Fawcett J (2010) American Psychiatric Association. vol. 10. Available at: http:// www.dsm5.org/progressreports/pages/0904reportofthedsm-vmooddisordersworkgroup. aspx.

Figert AE (2005) Premenstrual syndrome as cultural artifact. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science 40(2): 102–113.

Jimenez MA (1997) Gender and psychiatry: Psychiatric conceptions of mental disorders in women. Affilia 12(2): 154–175.

Laycock T (1840) An Essay on Hysteria. Philadelphia: Haswell, Barrington and Haswell.

Loring M and Powell B (1988) Gender, race and DSM-iii: A study of the objectivity of psychiatric diagnostic behavior. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 29(1): 1–22.

Micale MS (1995) Approaching Hysteria. Disease and Its Interpretations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mitchell SW (1885) Lectures on Diseases of the Nervous System Especially in Women. London: J.A. Churchill.

Morrow M (2008) Women, violence and mental illness: An evolving feminist critique. In: Patton C and Loshny H (eds) Global Science/ Women’s Health. New York: Cambria Press, pp. 147–162.

Parlee M (1973) The premenstrual syndrome. Psychological Bulletin 80: 454–465.

Playfair WS (1892) Functional neurosis. In: Tuke DH (ed.) Dictionary of Psychological Medicine. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, p. 851.

Porter R (1993) The body and the mind, the doctor and the patient: Negotiating hysteria. In: Gilman SL, King H, Porter R, Rousseau GS and Showalter E (eds) Hysteria Beyond Freud. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 225–285.

Rodin M (1992) The social construction of premenstrual syndrome. Social Science and Medicine 35(1): 49–56.

Showalter E (1987) The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture 1830-1940. London: Virago.

Showalter E (1997) Hystories: Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

Smith-Rosenberg C (1986) Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Steiner M and Born L (2000) Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. CNS Drugs 13(4): 287–304.

Sydenham T (1679) Epistolary Dissertation to Dr. Cole. The Works of Thomas Sydenham, vol 2. London: The Sydnenham Society (1843).

Ussher JM (1997) Fantasies of Femininity: Reframing the Boundaries of Sex. London/New York: Penguin/Rutgers.

Ussher JM (2006) Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body. London: Routledge.

Ussher JM (2011) The Madness of Women: Myth and Experience. London: Routledge.

Ussher JM and Perz J (2010) Disruption of the silenced-self: The case of pre-menstrual syndrome. In: Jack DC and Ali A (eds) The Depression Epidemic: International Perspectives on Women’s Self-silencing and Psychological Distress. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 435–458.

Ussher JM and Perz J (2012) PMS as a gendered illness linked to the construction, relational experience of hetero-femininity. Sex Roles. Published online April 11, 2011, DOI: 10.1007/s11199-011-9977-5.

Wirth-Cauchon J (2001) Women and Borderline Personality Disorder. New Brunswick: Rutgers.

Yu M, Zhu X, Li J, et al. (1996) Perimenstrual symptoms among chinese women in an urban area of china. Health Care for Women International 17: 161–172.

#women#psychology#psychiatry#discrimination#hysteria#borderline personality disorder#sexism#premenstrual syndrome#femininity#patholization#medicalization#gender roles#critique

2 notes

·

View notes