#it's not a Bad cultural import it's just... the calculated cynicism of it all. and having watched it happen live

Text

When I’m an old lady I’ll still be informing young people that Halloween never existed in this country until the 90s /early 00s when people who sell us stuff realised they could use it to sell us more stuff, and Halloween-themed stuff suddenly appeared in shopping centres without warning and was relentlessly marketed to children, and adults saw right through it and disliked it (“what’s this American sh*t, why are there pumpkins and witches in shop windows this never used to be a thing”) until they got used to it and young generations grew up thinking Halloween had always been a thing here even though kids born just a decade earlier had to be taught about it by the TV or school. Also it trampled over our pre-existing Fun Cultural Event When Kids Get Dressed-Up which had never needed to be marketed so aggressively and therefore became less relevant

I don’t mind at all if you love Halloween but it’s so weird to see my younger cousins convinced that it was always a thing in France when I remember being taught at school what trick or treating was, like “let’s learn about cultural traditions that are exotic and fun and different from ours!!” and I’m not old. Millennials literally saw Halloween get astroturfed into our culture with no explanation when shopping centres just went “from now on this is something we’ve always done” and we had no choice but to be like well OK I guess 🤷♀️

#i took the bus to the Big City and there's halloween stuff everywhere and i'm like old woman yells at cloud#it's not a Bad cultural import it's just... the calculated cynicism of it all. and having watched it happen live#and the homogenisation of cultures#when i tell my cousins how recent it is it kind of blows their minds#if an older cousin had told me when i was 10 that she had to be taught what christmas was in school i would have been befuddled too

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Worldbuilding Diaries- Chapter Two; Your Main Character

Main characters are the crux of a story and they can carry it well or sink it in seconds. As I began constructing and developing my main character for my fantasy series I realized that there are lot of things a main character can be and how the way we, as writers navigate creating our main characters can be super influential in the outcome of our stories.

This post is going to delve into a couple points

1. What are main characters and what’s their purpose?

2. How the rest of the cast can effect the mc

2. ...and how to make your mc memorable

Main characters are the vessels that the events of our stories pass through and their opinions, perceptions and interpretations of events can change depending on who they are, their purpose is to tell the story the way you want it told and to experience as many of the inciting incidents or main events as they can. Sometimes our desires for our main character are incompatable with the plans for our stories for example as I began drafting Project Sun Ballad I realized my main character was stupid...frustratingly stupid and a scaredy cat which was not intentional. He lost all the stubbornness and brute anger I initially intended and as a result the events of the opening chapter felt underwhelming and childish less adult fantasy and more scary Dr.Seuss book. This was because of his new personality and all the softer language I used in my first drafts, so I aged him up into his early twenties and made him slightly more cynical.

Your main characters personalities should help communicate or add to how your story is relayed. Their voice (the thoughts they add in) should help drive the story forward. Their actions should either have consequences or improve/propell them toward their goal. Your main character can care about everybody or nobody and still make decisions that help or hurt people. Figuring out those consequences or how they are going to learn about a secret meeting via non-coincidental means can help spur your creativity and can lead to some really interesting plot points or scenes. When making your main character imagine that they are the blurb of your story and details about them, their name, where they live and their personality should give the reader information and a basic idea of what they are about to read.

So you have a main character, they could be a lone-wolf ranger in the wild south with a trusty dog by her side or a glamourous prince suddenly trapped in a heavenly domain but whats just as important is their side kicks, the antagonist in the story, the wise mentor etc Your stories cast, whether that be a handful of small secondary characters or a full set of royal families and servants to suit are important and their engagement with the main character helps support your mc’s narrative and story. Compatability within your cast helps add life to dying scenes, banter, encouragement, calculated insults and emotive decisions are so much stronger and memorable than a main character with some sweet monologues. Whenever I read a book and the main characters and side characters, interact and remember each other and think about each other before they act???? It’s great and I live for it. In my book every three of the four main cast come from different cultural backgrounds, with differen’t patrons and goals, their differences helps them connect with each other and help my mc grow and establish his worldview and moral beliefs.

I like to place my main character in a room with every character even if they could never reasonably come into contact and forcing them to have a conversation, will they talk about similar things, will one apologize to the other it helps me identify whether certain characters are too similar or if my main character is terrible and has nothing to add or nothing to say to anyone.

There are billions of characters out there with varying physical descriptions and personalities and sometimes it can feel impossible for your main character to feel anything but another carbon copy of the usual main voice in your chosen genre. For my fantasy novel I took the time to step back and reflect on my main character and the tropes associated with the genre, young boy, small town, magical abilities, simple features, mentor figure he leaves behind. So I took him and pretended that he in my minds eye had levelled up like he would in a video game to level 20. I dropped the simple features and gave him violet eyes and made violet eyes as common as blue eyes normalizing it within my world but still giving my character a memorable physical description. I was also inspired by a lot of my favourite main characters, specifically Aang from Avatar and slapped a symbolic geometric shape on my mc’s face, an upside down triangle painted with black liquid chalk. It helped clarify his appearance in my mind and hopefully the readers mind. You can create memorability in an array of things simply by deviating from the carbon copy, cookie cutter mold and in order to do that I encourage you to actively look out media and stories no matter how short that feature unique and rarely seen main characters, voices and setting. By diversifying your reading you reduce the risk of seeing a simple pale unexciting cast as a normal background to prose perfected by watching writing tip youtube videos. One of the best ways is to treat your characters like people, humans have disabilities or simple issues, I’m a writer with inflammatory arthritis, vertigo and stunted fine motor skills from a bad birth, people have these issues today and people had those issues throughout history. Here are some other ways...

- Embrace culture, face paint is prevelenant in many cultures and a character that embraces their culture and/or wears it regularly can make them distinctively unique. Interesting clothing, jewellery, hair etc can make characters more recognizable and provide a good point of departure in a scene to explore some characters culture.

- Make their body unique in ways that can lightly impact them and show them growing to learn ways around it, an extra finger, deafness in one air, a physiological limp, rosacea, port-wine stains and other cosmetic things (I love giving characters who can shapeshift unique details that can subtly give them away like missing fingers, scars and/or birthmarks.

Overall how you decide to go about the construction of your main character and cast and whether you decide to change their designs or personalities is up to you!

Till next time, stay creative

#worldbuildingdiaries#worldbuilding#projectsunballad#wip#writingtips#writing#novel#fantasy#nanowrimo#maincharacter#characterdesign

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse Movie Review

Spider-Man 2 set the standard for the wall-crawler’s celluloid escapes, and the movies have been trying to catch up to that ever since. Thanks in large part to poor decisions by Sony, it never came close until Marvel got a hand on the property again. The last thing I ever expected from Sony’s own spin-off movies was that they’d be any good, especially after surviving Venom. As it turns out, the soul of the character just needed animation to set it free. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse is not only a great entry in the webslinger’s mostly forgettable filmography, it’s in the top tier of superhero films, period.

Miles Morales (Shamiek Moore) is a black teen being sent to a private school after winning a scholarship; his father (Brian Tyree Henry) is a by-the-books cop who struggles to understand his growing son but loves him anyway, which sounds cliche but works because the character is so well-written. His mother (Luna Lauren Velez) is unfortunately sidelined, and spending more time on her in the sequel would be welcome. He looks up to his uncle Aaron (Mahershala Ali), who shares Miles’s love of graffiti art but who is also some sort of a criminal. I mention Miles’s race because it’s important: the movie elects for a happily stable family and a smart kid with a bright future, a rare focus for African American characters in cinema. The movie is not political in the slightest, and treats this as if it’s not uncommon, because it isn’t. It’s a deliberate contrast to Peter Parker, whose life is a constant mess. Miles gets his powers with a similar spider bite and without much fanfare.

Speaking of Peter Parker, he shows up, voiced by Chris Pine, and gets in a big fight involving the Green Goblin (Jorma Taccone) and the Kingpin (Liev Schreiber), classic Spider-Man villains somewhat re-imagined for the setting. When things go wrong trying to stop a dimension-combining device, Miles lands the gig of stopping the machine from firing again, but can barely use his own powers. Another Parker (Jake Johnson), an older and out-of-shape one who has given up on life, shows up and doesn’t make a very adequate mentor. He’s eventually joined by numerous other versions. Spider-Gwen (Hailee Steinfeld), who is clearly here to launch her own spin-off, is cynical and calculating. Peni Parker (Kimiko Glenn) is an anime take on the character whose powers are actually invested in a machine that I think is piloted by a spider itself. I’ll be honest, I lost the details in the rush, but she works because she’s more homage to the form than parody. Spider-Ham/Peter Porker (John Mulaney) is sadly underutilized and didn’t really add as much as he could; there’s too many other Spider-guys for him to stand out. By far my favorite was Spider-Man Noir, a version who is almost all shadow, wears a fedora and trench-coat, and is voiced brilliantly by Nicolas Cage, who channels Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney. Indeed, the voice cast is so stuffed that Lily Tomlin and Zoe Kravitz end up in tertiary roles. Each of these alternate heroes got sucked into Miles’s universe and will see their molecules fracture like a bad radio signal if they don’t get back. For this, they seek the help of a batty-but-brilliant scientist (Kathryn Hahn), who provokes one of Parker’s best lines. Each is accompanied by a quick and humorous rundown of their respective origins, which both serves as a nice send-up of the now-tedious origin story and fills in whatever small amount of info the audience might need.

A disclaimer for those who are understandably confused about Spidey’s cinematic history: none of these Spider-People are the same one from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, that interconnected place of Guardians and Avengers. The Parker here appears to be some version of the one from Sam Raimi’s first trilogy, and considering the divided reception of that line, it’s an interesting choice (it still contains the best Spider-Man movie, and a couple lackluster ones). It matters far less than it does in the MCU, because this movie feeds more on energy, humor and heart than on continuity. To my recollection (it’s been a while), all of these characters exist in some way in the comics, but you don’t have to care. On screen, they play off each other wonderfully. The jaded Parker is like those wizened mentors from every movie ever made about a plucky kid finding his way, except this guy, while having the skills, doesn’t care. That’s a decidedly different look for Spider-Man, one that only an animated film, specifically only an animated film this unique, could pull off; an apathetic hero is just not something audiences would accept if he were the main character. The Noir version has the most potential for his own movie, as his universe is the most different from what we’ve seen before. Like Rey in Star Wars, Spider-Gwen is unfortunately given the least interesting character, but there’s room for development later. For some reason, the same people that decided we need more female heroes (which we do) also decided they always have to be---pardon the expression---the straight man. Will we maybe have a female take on Tony Stark at some point? I won’t hold my breath; the culture just isn’t there yet.

The heroes are of course opposed by the afore-mentioned villains, joined by many others: Prowler, a Batman-esque fighter, Scorpion (Joaquin Cosio), Tombstone (Marvin “Krondon” Jones III) and a surprise bonus pick who I will not mention because you should discover it for yourself, except to say this person really works while, in a way, bringing back a long-absent, long in demand foe. When machines are activated and villains are fighting, the movie does occasionally veer somewhat close to confusion, but it always recovers, with the exception of some of the villains being rather generic. Animation has unshackled the agility, speed and wit Spider-Man has always evoked in the minds of people flipping through comic panels. There’s a litheness to the movements of the characters that no amount of CG could ever replicate, and a boundless energy that the unique animation style---designed to look like comic panels in motion and, to my eternal shock, actually successful in this---works perfectly with.

Still, the most surprising thing is how the emotions carry through. Each Spider-Dude-or-Dudette has their own tragedy and loss, and the sense that no matter what universe he exists in, he’ll always have to deal with that is sadly poignant, especially for anyone who grew up on the Spider-Man mythos. There are actual stakes here; even the motivations of the Kingpin have real heft. The movie has been handled by Lego Movie producers Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, with a small army of co-writers joining along the way, and the surprise is that for once, so many cooks have managed to concoct something that feels so sincere.

If you aren’t a comic person, don’t worry. There’s enough heart here to sweep you up even if you don’t know your spiders from your bats. Stan Lee’s posthumous cameo feels fitting, in a movie that does right by his (and Steve Ditko’s) best creation. Nerds tend to declare amazing absolutely every comic movie that comes out. And every once in a while, they’re right.

Verdict: Highly Recommended (3 1/2 out of 4 stars)

Note: I don’t use stars, but here are my possible verdicts.

Must-See

Highly Recommended

Recommended

Average

Not Recommended

Avoid like the Plague

You can follow Ryan's reviews on Facebook here:

https://www.facebook.com/ryanmeftmovies/

Or his tweets here:

https://twitter.com/RyanmEft

All images are property of the people what own the movie.

#spider-man#marvel#Nicolas Cage#the lego movie#mahershala ali#hailee steinfeld#movies#shamiek moore#brian tyree henry#luna lauren velez#chris pine#jake johnson#zoe kravitz#lily tomlin#kimiko glenn#john mulaney#joaquin cosio#superheroes#comics

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'm trying to understand where the idea that lotor is self-serving and only cares about himself and what he wants came from? we still don't even know his real plan, and his motive over going to voltron is to like... live, probably.

This is actually an interesting question, so, I wanna break this down a little and talk about Lotor, and reads on him, and what I think they’re playing off of.

1. History

I’m not sure how strong an influence this is, but the idea of Lotor as a pampered, materialistic, vain asshole is actually completely founded in other continuities. Quite a few of them- GoLion, DotU, and DDP in particular, depict Lotor literally keeping harems of beautiful women who waited on him, massaged him, poured him wine- and he drank a lot of wine.

Voltron Force broke away from the harem thing, but he was still shown drinking that’s-probably-an-alcoholic-beverage-but-they-won’t-say-so-because-cartoon in the bath while allegedly important things were going on. Admittedly with Force Lotor, this is moderately more understandable since he was undead and needed repeat exposures to a specific substance in order to keep the “un” part in there- and chose the sauna option over injection or radiation because he was sick of the alternatives.

It still comes back to, frankly, prior incarnations of Lotor absolutely deserved to be identified as spoiled, or at least used to the good life. While I’ve yet to find a single incarnation of Lotor that has a good relationship with Zarkon, in most other continuities, Lotor had ample resources separate from him (in a few, such as Force, Lotor is in charge as Zarkon is long dead) and was very inclined to indulge in them- and, as the very nature of a slave harem necessitates- often directly at others’ expense.

Of course that’s only as logical an explanation as making assumptions about VLD Lotor based on other incarnations of the character, when Lotor, like every other character in VLD, is a very different creature from his prior selves. Never in VLD’s canon have we witnessed Lotor doing anything that looks like partying or relaxing- or even not immediately related to his ambition. This continuity sets him up as a counterpart to Shiro, after all, and Shiro is a rather dedicated workaholic.

The only pleasant company Lotor entertains is the generals, and that’s about the furthest thing from a “harem” as you can get- the generals are autonomous, ambitious people, and, like Lotor, they spend their onscreen time working. Their relationship is businesslike in nature, and while Lotor clearly considers them friends and is more personal with them than mere coworkers, we have no evidence their relationship ever moved out of the territory of allies and conspirators. And Lotor hasn’t shown romantic or sexual interest in anyone else, much less acting on it.

It’s a facelift very similar to Zarkon, when prior incarnations of his character were also inclined to extravagant opulence. However, while in VLD Zarkon’s case, his spartan inclinations still come with their own flavor of ostentation, and it’s simply that he has nothing to prove as he’s already considered something approaching a god- in Lotor’s case the specific lack of pampered settings is used as one word in a different ongoing message- that Lotor’s ambition and calculation in this continuity is rooted not in entitlement, but a deep, abiding bitterness.

Other incarnations of Lotor were selfish people, and their unhappiness rooted in Zarkon’s abuse drove some of their selfish grabs, but even then, their behavior was neither understandable, nor sympathetic. (GoLion’s Sincline, for example, lusted after Allura out of misplaced grief over the traumatic loss of his mother, but he was still trying to abduct and forcibly wed an unrelated teenager who happened to look like his mom)

And that leads into my second point…

2. Self-serving versus selfish

Talking purely VLD here, Lotor is established as a manipulator, and someone who’s not afraid to lie through his teeth to other people. Given that this is the same context in which his more noble, political reform ambitions also come to light, I think many people have come away with the assumption that Lotor is inherently selfish- that his manipulation and behind-the-scenes discarding and mockery of Throk is evidence that Lotor is ultimately a cruel person.

And this very flavor of guile, on prior incarnations, did have the take-home that Lotor was ultimately a nasty guy only in it for himself.

However, again, in VLD, Lotor is a good deal more desperate, and more vulnerable, than his prior selves.

There is no Altea left. It’s dead and gone. And Lotor is not only biologically half-Altean, but frankly, from a cultural perspective, even down to his accent- he’s basically an Altean with a thin coating of just purple and pointy enough to be palatable to the average galra. This puts a very different spin on his relationship with the empire, and with his father, especially given the latter very actively and deliberately is trying to complete his earlier genocide of the Altean people.

Prior incarnations of Lotor didn’t have this problem- even Sincline, who was half-Altean, still felt safe enough that he acted as a conqueror in furthering Zarkon’s empire, and actually, before he started to struggle against Voltron, entertained a fairly cozy position.

VLD Lotor, however, is a vulnerable minority neck deep in the heartland of the empire and he has basically no illusions whatsoever that his title won’t save him. He’s not scheming against Zarkon because “boy, it sure would be neat to have more power here, too bad my smelly old dad is immortal, is there any way I can help the natural process along here” nearly as much as “it’s inevitably going to be me or him, and if I don’t shoot first, he will.”

Lotor’s a survivalist. And in that sense, he is self-serving, but not in the way of someone who’s gonna use your tears to salt his martini, so to speak. We see this a lot in, say, his interactions with Puig, or in s4e5 when he bails on the generals.

Lotor does, in fact, make decisions that serve himself. Sometimes this is at others’ expense. His attitude, virtually always, is “I don’t particularly want to be doing this. I can tell you’re hurting, and I don’t really want you to be. But… if I don’t take this, I’m going to die, and I also don’t want that. Well, then. take care of yourself.”

The only people Lotor’s consistently shown to have no sympathy for is Zarkon, Haggar, and people like Throk who are gleefully and unabashedly part of their empire. And that’s not really surprising, and it’s certainly not a villainous trait. Our heroes are the same way- they really don’t have much empathy for the commanders and generals that are happy under Zarkon.

The specific way Throk frames his criticism of Lotor in s3e1 boils down to Throk perceives Lotor’s more merciful approach as a threat to the empire. Compassion and empathy are hazards to Throk, who is, in short, an aristocrat who bought his way to the top with other people’s blood and tears. He brings this up repeatedly when fighting Lotor- that he has hurt others, that he is proud of his violence and cruelty onto others.

And Throk? Throk is the guy Lotor genuinely throws under the bus, chews him out and spits him out coldly, and I’m willing to bet there is more than a little bitterness and vengefulness in there. But pulling this back to our original topic:

Guile, manipulation, scheming, are in short, not stereotypically heroic traits. Seeing Lotor lie to Throk, from a viewer’s perspective, awakens a reflexive discomfort in us, because seeing people lie to each other and undermine them behind the scenes is stereotypically villainous behavior. The audience becomes suspicious and on edge towards Lotor, and this causes them to read the rest of Lotor’s behavior in a very cynical light- any compassion or empathy we see out of him going forwards has to be a lie, has to be a trick.

The thing this read misses is that Throk again, defined himself by his cruelty and vindictiveness. He isn’t a guy we should be weeping for all that hard. Our heroes would have messed him up just as much had they gotten their hands on him first. That’s why Throk is given so much time to speak for himself, and establish that yeah, he’s a violent bigot and proud of it, and how heavily, thematically, Lotor’s manipulation of Throk is framed as a counterattack.

Because both practically in the duel and in the larger situation, Lotor hangs back and lets Throk pound on him, only focusing on blocking and protecting himself. He doesn’t even come out of it unscathed- there’s a notable moment of Throk clipping Lotor’s hair, which Lotor doesn’t once acknowledge.

The entire time Throk and his friend are speaking of Lotor, we see Lotor in the ring, set upon by his larger opponent- dodging, evading, weaving around. This is a very direct visual allegory- Lotor is an underdog. If there’s anyone who picked this fight first, it’s the thousand injuries of the galra empire Lotor’s endured first.

So what this all comes back to, I think, is that there’s a failure to distinguish prior continuities’ selfish, arrogant Lotor, who had plenty and wanted more, from VLD’s Lotor, who’s more of a starving wolf on the prowl. Both are dangerous- both will take what they want and if need be hurt you to get it.

But one of them wants without any real need behind it- wants, in the way that someone sitting in a comfortable room surrounded by beautiful people sees someone that doesn’t belong to them and salivates. And that’s unsympathetic, even if it’s rooted in genuine tragedy- because GoLion’s Sincline made the choice to fill his void by trapping other people inside of it.

VLD Lotor is not a selfish person. He’s aggressive, he’s ambitious, he’s calculating, the same way prior incarnations of his character were. But need and want are really the same for Lotor- there’s nothing he doesn’t try to hold onto that he doesn’t need, and those needs are unfulfilled.

It’s actually really kind of a fascinating contrast to look at DotU Lotor who has so many people waiting on him hand and foot that he throws them away and basically ignores them (I don’t think we ever learn any of his attendants’ names, nor are they treated as full characters who have lives outside of him, with the exception of other people he tries to kidnap, such as Romelle) and compare that to Lotor where the only four people whose company he genuinely seems to enjoy, all named and full characters, all left him one way or another, partially through his own actions, but with an overwhelming sense of helplessness from him the entire time.

People have compared the generals’ betrayal of Lotor to the fall of Azula, when one of the meaningful differences is that Azula was completely outraged and shocked to lose Mai and Ty Lee.

Lotor, once he gets over the initial surprise of being shot? Just kind of takes it as a given.

It comes down to the difference between a glutton and someone who’s been living on the street without reliable food for years. Both of them are going to be preoccupied with their next meal, but in very different contexts- one goes “ho hum, what shall I eat today,” and the other one is going “will I be able to eat today?”

And to me, I think sympathy entirely aside, that’s something that makes VLD Lotor a lot more dangerous than his DotU self. Because DotU Lotor could be counted on to indulge (the oft-quoted birthday party episode) and this was something his enemies could exploit- he’d lower his guard to have a good time.

VLD Lotor is a terrified, embittered person who takes almost nothing for granted and even if he’s far more ethical than his older incarnations, Narti’s fate alone is a magnificent case study in how far Lotor will go doing things he doesn’t want to because he lives his entire life with his back to a wall knowing if he doesn’t personally carve a way out here through whatever might be in his way, he’s not leaving.

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dezeen's top 10 most talked-about stories of 2020

This year had its fair share of provocative stories, from Donald Trump drafting new legislation on federal buildings to Bjarke Ingels plotting to redesign Earth. For our review of 2020, digital editor Karen Anderson looks at 10 of the most talked about.

Harikrishnan's inflatable latex trousers create "anatomically impossible" proportions

Readers debated our coverage of menswear designer Harikrishnan's billowing latex trousers, which were created for his graduate collection at the London College of Fashion.

"I really like the pear shape of the white pants," praised Rose Winkler. "I picture them with the same shaped arms on a stage. They feel very medieval. Reminds me of Popeye when he eats his spinach."

"Absolutely love the concept!" added Karen Thomas. "Mad technical skills have gone into creating such art. Especially the time invested in getting those beautiful beads made. Curious to see what's next!"

Find out more about the inflatable latex trousers ›

AIA opposes President Trump's draft rules for Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again

One of the biggest stories this year was news that the Trump Administration planned to introduce an order that all federal buildings should be built in the "classical architectural style".

In response to the draft order, called Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again, the American Institute of Architects called on members to sign an open letter petitioning against it. The story on Dezeen attracted more than 323 comments.

"Does this sound familiar? Hitler did that." said Pam Weston. "Similar in aesthetics too. Is anyone besides me scared yet?"

"What's the big deal here?" asked Elrune The Third. "This classical style is part of the national identity and design language of the USA. No one will die because Studio BIG doesn't win the next contract for a courthouse."

Find out more about the opposition to Trump's draft order ›

Zaha Hadid Architects and Grimshaw among architects to criticise Autodesk's BIM software

The story that received the second most comments this year was news that Zaha Hadid Architects and Grimshaw were two of 17 architecture studios to sign an open letter to software company Autodesk, criticising the rising cost and lack of development of Revit.

The president and CEO of Autodesk responded to criticisms of its software, admitting improvements "didn't progress as quickly" as they should have but rejecting claims it is too expensive.

Readers weren't convinced. It's "like charging 2020 prices for a Cadillac on a 2005 Ford Focus," said UTF.

"This software is bad," agreed Michal C. "My life got way shorter thanks to constantly fighting its limits and bad design. Using it in building design is like doing brain surgery using two bricks as the only tools."

Find out more about criticism of Autodesk ›

Masterplanet is Bjarke Ingels' plan to redesign Earth and stop climate change

In October, commenters furiously debated news that BIG founder Bjarke Ingels is creating a masterplan for redesigning Earth.

Approaching Earth like an architect master planning a city, Ingels calculates that even a predicted population of 10 billion people could enjoy a high quality of life if environmental issues were tackled holistically.

But some readers struggled to take Ingels seriously. "Please wake me up when BIG reveals a plan to redesign human behaviour," said Chris Becket.

Don Griffiths was more optimistic: "Lots of good things come from dreaming and scheming outside the box. This man might not have all the answers, but the future is better attended to by the actions of thinkers from the past."

Find out more about Ingels' plan to redesign Earth ›

Coronavirus offers "a blank page for a new beginning" says Li Edelkoort

Some readers reacted with cynicism to Li Edelkoort's predictions for a post-coronavirus future.

Edelkoort described how the disruption caused by coronavirus will lead people to grow used to living with fewer possessions and travelling less.

"How many times has history shown that's not how this works?" responded Rd. "Things will just go back to normal and change will happen slowly over time."

Others found the article comforting. "I take a lot of solace in what Li Edelkoort is saying," said Gerard McGuickin. "In a way, the Coronavirus is perhaps a reckoning for things that have gone before."

Ukrainian architect Sergey Makhno also shared his predictions on how our homes will change once the coronavirus pandemic is over whilst Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky shared his thoughts on how the coronavirus pandemic is likely to change travel.

Find out more about Edelkoort's coronavirus predictions ›

Steel and concrete steps cut through facade of Stairway House by Nendo

Opinions were divided over Japanese design studio Nendo's unusual addition to a multigeneration house in Tokyo – a giant decorative staircase dividing the house in two.

Some felt that the sculptural stairway was too much of a health and safety risk. "I can't imagine living there with a kids," worried Salamoon.

And Room advised people to live a little more dangerously. "If everyone here wants a run-of-the-mill cosy little cottage or bungalow or timber-framed three-bedroom suburban potted plant safety palace, why are you reading this magazine?" they quipped.

Cliff Tan weighed in with some important cultural context. "This is really obvious if you are East Asian," said Tan. "In Feng Shui terms, this site, sitting at the top of a long road, invites too much energy into the site," he added. "The staircase takes all this energy and swoops it towards the sky, keeping the rest of the home calm and protected."

Find out more about Stairway House ›

Bjarke Ingels meets Brazil's president Jair Bolsonaro to "change the face of tourism in Brazil"

Bjarke Ingels previously made headlines when the architect met with the president of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro to discuss developing a tourism masterplan for the northeast region of the country.

"Glad to still see starchitect clamouring to work with corrupt governments," said WYRIWYG. "As long as the fees are high enough..."

"Yeah, because a Danish architect knows exactly how to deal with beaches and the social background of our country," added Edson Maruyama. "We have great architects and urbanists in the country.

Ingels released a statement defending his decision and rejecting the idea that countries such as Brazil should be off-limits to architects.

Find out more about Ingels meeting Jair Bolsonaro ›

Eva Franch i Gilabert fired as AA director for "specific failures of performance"

Another controversial story in 2020 was news that Architectural Association (AA) director Eva Franch i Gilabert was fired.

The decision was taken by the London school two weeks after Gilabert lost a vote of no confidence in her leadership.

"Eva absolutely deserved an opportunity to lead," said AA Dipl. "AA is a testbed for creative ideas and methodologies and sometimes an experiment doesn't prove successful. Yet AA is the only place where one can try and fail and we should admire the school for that reason. "

Hotel Sphinx also commented: "Surely those of us outside the AA community cannot truly understand what has transpired over the past two years, culminating in this decision."

Find out more about Gilabert's dismissal ›

Groupwork designs 30-storey stone skyscraper

Amin Taha's architecture studio Groupwork attracted attention when it designed a conceptual 30-storey stone office block.

The studio said the building would be cheaper and more sustainable than concrete or steel equivalent, but some readers thought it was dull.

"The discussion is all about the material and nothing about the boring design," said Egad.

"I'd rather call it straightforward rather than boring," replied K Anderson. "It's an elegant and well-proportioned tower while taking advantage of the material's natural qualities and production process. Gold doesn't have to glitter.

Taha himself responded in the comments section, saying: "The tower is a simple, sober, yes boring design for the purpose of comparing like for like against standard commercial offices. It is after all only a material, not a style."

Find out more about Groupwork's stone skyscraper ›

Urban planning is "really very biased against women" says Caroline Criado Perez

British writer Caroline Criado Perez wrote a book claiming that cities haven't been designed to suit the lives of women, sparking debate amongst readers.

"I agree with this completely," said Sim. "Last week the design for the longest cycling bridge in Europe was revealed. While it was hailed a triumph, as a woman all I could think of were the evenings I would be cycling home alone and the idea of this bridge scared me."

"Come on!" replied Architecte Urbaniste. "This whole man versus woman urban design discussion is missing the point. Most architecture is designed by teams of people containing both men and women. I've seen groups of women designing completely unliveable urbanism too."

Find out more about Perez's book ›

Read more Dezeen comments

Dezeen is the world's most commented architecture and design magazine, receiving thousands of comments each month from readers. Keep up to date on the latest discussions on our comments page.

The post Dezeen's top 10 most talked-about stories of 2020 appeared first on Dezeen.

0 notes

Text

On Healing After A Break Up by Lauren Sarrantonio

In late 2017, memories of my long ended relationship flooded me. These were memories I had not recalled since they happened. I hadn’t made the space for myself to reflect on any of it until over two years after our breakup, two years that were comprised of harbored resentment, spiteful acts, and shame. My delayed grief was self inflicted; I established thinking-about-it-after-the-fact as an impossible option. In retrospect, he was too much a part of my everyday, and so to sit and attempt to calculate that loss in its immediate aftermath would have stifled me. I had to keep moving.

Life belongs to those who are unafraid to feel. In a world where our senses are constantly being exploited and capitalized on, it can sometimes be hard to feel anything amidst the overstimulation. Merely being present on a street in New York will render your sensory cortex to the saturation of smoky smells, screeches and bangs, lights and faces. In other words, we’re not allotted the space to feel from anyone. We need to show up and make that space for ourselves.

For me, carving out that space means sitting at my desk and journaling, even if it hurts to hold the pen that day. Even if I can only write a sentence at the moment.

It means driving up the mountain to see my small, stirring world beyond the overlook.

It means breathing deep enough to feel the heaviness in my chest stretch and wake.

It means doing the exact thing I am afraid of doing, because I already know that it’s still good and important for me to do. Because even though I am afraid, I still want to.

Vulnerability, fear and love are inextricably linked and they play vital parts in our lives every day. You know how you can’t really see the sun? You can look toward it for a few sparing seconds, but then you’ve got to look away. And yet, this burning star illuminates everything else in its path, and we may look at these other things for however long we’d like.

Vulnerability, like the sun, cannot be contained, stopped or blocked. At least, not for long. It will come, and when it does ,in the right situations, it will shine light onto everything right in front of us. No, vulnerability is not like the light. It is the light. At high noon we can see that what it makes visible is love.

Fear rests in shadows. It’s important to distinguish that fear is not the shadows themselves, but something more elusive within them. I don’t mean to stigmatize darkness. But fear is comfortable there. Hidden, still. One day in the red hue of a traffic light, I was thinking about what it means to be afraid. The notion, ‘fear is the absence of love’ didn’t seem totally accurate to me. Besides, there cannot be shadows if there is no light. Rather, fear is the burial of love. And fear likes shadows because they are weightless graves. The love is there, it’s just not able to breathe. Love, paired with fear, is hidden away in the shadows.

The grief over the end of my relationship was only deferred, not diminished. It stayed with me. I carried my grief like an object. I took it everywhere I went. Briefly I’d forget about it, as if it had moved to a back pocket. But it was there.

That’s the thing about grief. You don’t have the luxury of forgetting. It will tint your relationships and dreams and health until you decide to pay its respects. You may defer the grief, but time will bring it back. And finally after two years, instead of running, or chasing, or hiding in shadows, I saw the option to surrender.

If a smell triggered a memory, I wouldn’t escort it away like before. I would search that memory and remember the sweet moments I got to share. The sweaty dance studio. The dying cornfields. The empty auditorium. One particularly vivid memory was triggered while I was in warrior one at yoga. Okay, maybe I’m supposed to let thoughts go in yoga, but I explored this one. Suddenly I felt the space that lived between us become a tenderness. My recollections were warm gifts, not threats of abandonment, or doubt, or anything other than loving moments that I had the privilege to experience. I think these moments were waiting to be honored, they were stuck inside my grief, and now that I have acknowledged them, they feel much lighter; they are allowed to be in the past.

My healing became the antidote to what our overstimulating, productivity-obsessed culture says we must do. I sat quietly with my emotions. I let bad dreams have their way with me. I didn’t tune it out. It took years to come around to it, but I faced the ache until it was tended to enough so that it may begin to dissipate.

Growing up, it had been natural for me to avoid vulnerability. I could A) deflect any emotionally stimulating conversation with quick-grab humor, B) wear my cynicism armor (which appeared to solve everything and make me look cool while doing so), C) not raise my voice at all and play the doormat, or D) a nauseating cocktail of all of the above. This issue is not unique to me, in fact, the reason it became natural behavior growing up is because it was just that for everyone else around me: normal. Sure, everyone has their own style of running, chasing, hiding.

What matters is that there is a light waiting for you beneath, where you can be vulnerable—where you can be brave. There are no bells and whistles. Come as you are. The light will envelope you in warmth. And it feels important to note that each of our light comes from the same source.

I forgive myself for deferring my grief. I know it was because of my fear of vulnerability. If I admitted to being sad, and hurt, and lonely, that meant that I was breakable.

But the problem is not that I am breakable, the problem is that I was never told that breaking open allows the light to meet me in new places, so long as I don’t hide from it. It’s actually a blessing to get broken. I am not alive in spite of my heartbreak, I am alive because of it.

Let me make clear, I’m in no way cured of heartbreak, nor exempt from experiencing it ever again. But I know that if I go forth without the fear of feeling, and trusting myself in my capability to make space to heal, I will be rapt for whatever life may bring.

By Lauren Sarrantonio

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

MMH Does Architectural Theory Part 5: Empiricism & The Picturesque (Conclusion)

Hello Friends! Boy is this going to be a little bit of a wild post. This is the part where ish hits the fan and things fall apart. It’s also just going to be a long post, so I’m sorry.

The architectural theory we’ve known and loved so far revolved around a Platonic concept of absolute harmony, or innate beauty, a concept the Renaissance tied to proportions in architecture.

However, what if it’s not proportions in architecture that make architecture beautiful? What if beauty really is relative? What if there’s more to great architecture than beauty alone?

Bickering About Beauty

Is Beauty Absolute or Relative? Or both? Why, if we don’t have any innate thoughts, do we find the same things beautiful?

As it turns out, it was mostly the Irish and the Scots who argued this one out while mainland Britain was content with its cool new gardens.

Francis Hutcheson, an important Irish philosopher, found a loophole that, while clever, was ostensibly of the past.

In his 1725 essay “An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue,” Hutcheson describes beauty not as an external attribute, but as an innate sense in all people. AKA, absolute beauty is not an objective quality, but an actual part of the human mind. This was Hutcheson’s way of getting around Lockean ideas of sensation - by calling beauty a sense within us rather than a reaction to that which is perceived by our senses.

Hutcheson was very into the writings of Shaftesbury, which attached our ability to determine what is beautiful to our moral character. Therefore only good people or geniuses could have good taste. Sure, claimed Hutcheson, all people can sense things, but only an elite few can use their senses in the “correct” way.

This is, of course, total bullsh*t.

George Berkeley, another Irish philosopher, rebuked these ideas savagely. Berkeley believed in Lockean empiricism, but unlike other philosophers, emphasized perception and human rationality rather than blind sensation or abstract thoughts.

Berkeley, in his rather humorous “Third Dialogue” of Alciphron (1732) uses a fake conversation (aka a dialogue) to completely wreck Hutcheson’s idea.

Basically, these two dudes Alciphron (Hutcheson) and Euphranor (Berkeley), are arguing. In the beginning of this conversation, Alciphron says that beauty is not just that which pleases but is actually that which is perceived by the eye, namely proportions. To paraphrase:

E (playing extremely dumb): but these proportions aren’t the same for everything, right?

A: of course not, idiot. the proportions of an ox don’t work for a horse, dummy.

E: so proportion is the relation of one thing to another

A: Duh, idiot.

E: So, these parts and their sizes and shapes must relate to each other in such a way to make up the best possible, most useful whole.

A: dude, of course.

E: So, like, you’re using reason to choose and match and assemble this whole from each part.

A: y-yeah...

E: So, proportions aren’t just perceived by sight, but by reason by the means of sight.

A: k

E: So beauty isn’t really of the eye but of the mind, right? The eye alone can’t tell if that chair is a great chair or that door is a great door, right?

A: Dude, where are you going with this?

E: To put it this way, you see a chair, right? Could you think this chair to be of good proportions if it looked like you or anybody else wouldn’t be able to sit your ass in it?

A: I guess not.

E: So you admit that we can’t find the chair to be beautiful without first knowing its proper use, which is of course, the domain of judgement.

A: Fine.

E: After all, if an architect finds a door to be pretty cool, and have its proportions just right, what use or beauty is left to that door if the architect instead turns it 90 degrees so it opens like, a doggy door but for people? It’s not beautiful, then, right? So the proportions don’t necessarily matter, the use of the proportions matter, u feel me, my dude?

A: gasp

This goes on for a while. But the point is the same: there’s more than just an innate sense to beauty, it must have an application or context and therefore is relative and not absolute.

ENTER MY HOMEBOY DAVID HUME

Aww yiss, it’s time for by main dude David Hume, the Scottish philosopher that would blow so many minds of other philosophers while also being less of a reactionary asshole than his contemporaries. (I’m not sorry)

Hume claimed that beauty was relative to our personal experience, and that because we all share similar experiences and a similar psychological makeup, we tend to find similar things to be beautiful. Hume, like Berkeley, believes in some sort of functional component of beauty, and even links this to architecture in his A Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40):

“In like manner the rules of architecture require, that the top of a pillar shou’d be more slender than its base, and that because such a figure conveys to us the idea of security, which is pleasant; whereas the contrary form gives us the apprehension of danger, which is uneasy.”

AKA, the rules of architecture are derived from a practical standpoint, one of structural integrity, and that appearance of stability makes us feel relaxed because, well, the building doesn’t look like it’s going to fall down, right?

But Hume is most known in aesthetics for what has become a rather pithy adage: the statement that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

‘‘Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.’’

But then the question is if each mind perceives a different beauty, which brain perceives the right beauty? Thus enters the question of “taste”.

Bickering About Taste

We’re still bickering about good taste. In fact, this blog is primarily a treatise on, well, bad taste. One of the more important documents in architectural theory about taste was a dialogue by the Scottish painter Allan Ramsey, a best friend of David Hume (he painted the above portrait).

(In fact, Hume, Ramsey, Adam Smith, Alexander Gerard, and Robert Adam formed a group in 1754 called the Select Society, which I’m sure has provided for ample historical slashfiction at some point in time.)

Anyways, Ramsey’s “Dialogue on Taste” is important because it’s the first clear articulation of relativist aesthetics in architectural theory.

The dialogue occurs between Col. Freeman, a clever, roguishly handsome, free-thinking modernist and Lord Modish a good boy who loves his traditions. Yes, this is Perrault v Blondel all over again, but with savage wit.

you, dumb & trad: there are objective rules for architecture. Proportions!

me, incredibly mod & smart: uh, those are more knowledge than taste. It doesn’t take any genius of taste to follow a dumb Palladian recipe. Anybody can read a cookbook and make a boring dish. These so-called rules are only an analysis of what others find to be culturally acceptable, and don’t actually point to any natural standard beauty.

me, continuing to slay it: give me one reason that isn’t cultural why a Corinthian column in all its proportions isn’t as beautiful if I turn that SOB upside down. Like, what if, somewhere out there there are cultures that would find my upside-down column sick af - maybe they’d be horrified to hear about our right-side up traditions.

me, increasingly sassy: after all, these so called traditions and “tastes” are just the works of powerful rich people. If a poor dude wore a coat with triangular cuffs everyone would laugh at him and call him a big dummy. If a rich dude did it, suddenly you’d start seeing triangular cuffs everywhere no matter how stupid it looks. Tell me architecture ain’t the same way.

This is probably one of my favorite hot takes of the 18th Century, especially since it calls architecture a “fashion” explicitly, which was, like, unacceptable even though it’s ultimately true.

Regardless of this relative nature of taste, the centuries have still seen general consensus on what pieces of art are superior to others, and there must be some underlying theme other than cynicism regarding why this is the case.

Hume sought to answer this question in his 1757 essay “On the Standards of Taste” where he claimed that this consensus did not lie in specific rules of artistic composition, but rather in the universal makeup of the human psyche, which must be “rightly formed” to allow the emotions related to beauty to form.

“Though some objects, by the structure of the mind, be naturally calculated to give pleasure, it is not to be expected, that in every individual the pleasure will be equally felt. Particular incidents and situations occur, which either throw a false light on the objects, or hinder the true from conveying to the imagination the proper sentiment and perception.”

AKA you’re not going to find the Parthenon to be all that great if you’re, say, stricken with food poisoning or just got a call telling you you’ve been laid off.

We all have the potential to be stricken by a beautiful thing, but beautiful things strike us differently depending on how we feel at the moment or because of our pre-existing experiences. For example, you’re not going to find that Talking Heads album to be all that great because your jerk ex used to be really into them, even if the music is objectively pretty good.

However, sometimes art strikes us in ways that are different than mere beauty - sometimes art smacks us in the face and leaves us breathless, awed even. The non-beauty reactions to art are what will be discussed in the second half of this post, after the break.

Introducing the Sublime (With Bonus Wrestling GIFS)

No, not that one.

Basically, the sublime (in art) is the quality of greatness, that which cannot be comprehended or imitated. A bunch of smart philosopher dudes wrote about it, often after visiting the Alps.

Photo by Steve Evans (CC-BY 2.0)

Addison’s Foreshadowing of the Sublime

It was Addison, the guy from the end of last week’s post that foreshadowed thoughts about the sublime. Addison was not an architect, and sought to leave debates about the techniques and praxis of architecture to the experts. His essay revolves around the idea that it isn’t just beauty we should be talking about here, and offers a view of art as being either “Great, Uncommon, or Beautiful.”

What’s most important of the three is what Addison calls “Greatness” referring to “the Bulk and Body of the Structure, or to the Manner in which it is built...”

By Greatness of Manner, Addison referred to that familiar feeling of walking into a great place, the “Disposition of Mind he finds in himself, at his first Entrance into the Pantheon at Rome, and how his Imagination is filled with something Great and Amazing.”

This idea was taken further by Alexander Gerard, a member of Hume’s Select Society, who proposed that in order for something to be truly sublime it had to be both massive and simple.

“Large objects can scarce indeed produce their full effect, unless they are also simple, or made up of parts in a great measure similar. Innumerable little islands scattered in the ocean, and breaking the prospect, greatly diminish the grandeur of the scene. A variety of clouds, diversifying the face of the heavens, may add to their beauty, but must take from their grandeur.“

Basically:

This was an important precursor to the most lasting ideas on the sublime from everybody’s favorite reactionary philosopher who thought the French Revolution was bad (and monarchy was good) but that the guillotine was #^$%#ing sweet:

EDMUND “PAIN AND DANGER” BURKE

This is the greatest thing I’ve ever done with my time.

Burke’s treatise A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) claims that there are not only “some invariable and certain laws” behind our judgements of taste, described by him as “that faculty or those faculties of the mind, which are affected with, or which form a judgment of, the works of imagination and the elegant arts.”

This essentially puts the smackdown on the classical ideas that beauty is somehow related to utility or reason, as well as form or proportions destroying all of the theory we’ve learned about in the last four posts.

Burke then goes ahead to lay out and define some qualities of art and the reactions they engender in us:

The Sublime

I’ll just let ol’ “Pain and Danger” Burke speak for himself on this one:

“Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. I say the strongest emotion, because I am satisfied the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those which enter on the part of pleasure.”

TL;DR: Sublime, is pain & danger, the strongest emotions we can have, and pain is way more powerful than pleasure.

Qualities of the sublime, according to Burke include: vastness, infinity, succession (or consistency/repetition), and uniformity.

Specifically related to buildings, Burke focused on concepts such as difficulty, which he describes as “When any work seems to have required immense force and labour to effect it, the idea is grand.” He cites Stonehenge as an example - the labor needed to move such huge stones is more impressive than the end product.

He also discusses (and is one of the first to do so specifically) the important role light plays in building, especially on mood:

“I think then, that all edifices calculated to produce an idea of the sublime, ought rather to be dark and gloomy, and this for two reasons; the first is, that darkness itself on other occasions is known by experience to have a greater effect on the passions than light.

The second is, that to make an object very striking, we should make it as different as possible from the objects with which we have been immediately conversant...to make the transition thoroughly striking, you ought to pass from the greatest light, to as much darkness as is consistent with the uses of architecture.”

AKA dude was a huge Goth.

Most importantly to this blog, Burke had this to say about McMansions:

“Designs that are vast only by their dimensions, are always the sign of a common and low imagination.”

Burke’s writing set the course of aesthetic and architectural thought from this point on, eclipsing many that came before him, including Hume. Now that architecture had been liberated from the ties of proportion and function (for now), a new era of thought (and building) could begin.

I’m not sorry lmao

Well, that does it for Part 5! Stay tuned for this week’s Certified Dank Massachusetts McMansion on Thursday, and next Monday’s wrapping up of the 18th Century in which we see what’s up with the rest of Europe. Have a great week, and sorry for the technical delays!

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon! Not into small donations and sick bonus content? Check out the McMansion Hell Store - 100% goes to charity.

Copyright Disclaimer: All photos without captioned credit are from the Public Domain. Manipulated photos are considered derivative work and are Copyright © 2017 McMansion Hell. Please email [email protected] before using these images on another site. (am v chill about this)

#architecture#history#architectural theory#theory#philosophy#18th century#edmund burke#david hume#burke#hume#empiricism#aesthetics#aesthetic theory#philosophy of art

615 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do People Actually Judge A Book By Its Cover? Why Your Book’s Cheap Exterior Might Be Hiding A Literary Gem

Photo by rawpixel.com from Pexel

“You can’t judge a book by its binding.”

Passage from the African journal American Speech, 1944.

Just two years after this phrase was coined, it would go on to be adapted into mainstream idiom and pop culture, first and most notably in the book Murder In the Glass Room, by Edwin Rolfe and Lester Fuller, which featured the phrase “You can never tell a book by its cover.” On the surface, of course, this is a self-explanatory term, and even as a metaphor for any large number of scenarios and character assessments, its meaning is clear. However, metaphors and analogies aside, perhaps ironically, a field in which it is quite difficult to simply nod agreement with this is when actually judging a book by its cover.

WHY JUDGING A BOOK BY ITS COVER SAYS MORE ABOUT YOU THAN IT DOES ABOUT THE BOOK

To many, the answer may be straightforward: yes, we do judge books by their covers and no, perhaps we shouldn’t, but that doesn’t stop us. Absolutely, this is true on both counts for many people. However, there are many reasons why the answer to this question is actually more profound than it may first appear, and why its answer – individual to each of us - actually reveals far more about our own personality traits than it does about the writer, the book, the designer who created it, the publisher who chose it, or even the decision to print it. What it raises in us - those actually making the judgement - is questions of how much importance we place on perceptive visual importance, stereotypical presumptions, patience, openness to and tolerance of new talent, respect for opportunity, assumptions of financially social inferiority and perhaps more than anything else, loyalty.

IS READER LOYALTY EXCLUSIVE TO THE RICH AND FAMOUS?

To add a measure of context to that list, let’s first consider the last of them: loyalty. If I explain that in this case I mean loyalty to authors with which we have already established our position in their fandom – most likely famous – then perhaps the list might start to make more immediate sense. Consider the newest novel you bought by your favourite best-selling author – you may remember the title (you actually might not), but can you recall, without checking, the cover? Try to, right now. One thing which will almost certainly have been true of it, assuming your best-selling author is a famous one, is that his or her name was in much larger font than the actual title of the book, itself. Check your latest Stephen King or Michelle Obama book – it is a safe bet that the author’s name is at least 30-40% larger than the title. What kind of a message does this send, then? That if you are a famous, established author the cover doesn’t matter – even the title of your book doesn’t matter? If it’s a horror, it used Chiller font and a dark theme… probably; perhaps there were pictures of balloons or a pram, but who can remember? All that matters is the author who wrote it, and that it is the one you don’t own yet. The book might be bad – the cover might be terrible - but you’ll still probably buy his or her next one.

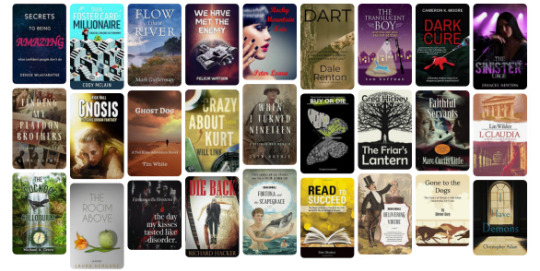

Compare this, now, to a new, unknown author. Those of us fortunate enough to work in the literary industry with up-and-coming authors should see things – including shabby book covers - very differently, and should pride ourselves on an inclination to appreciate the less superficial qualities mentioned in that list: openness, opportunity and new creative talent; this is, of course, a vital element of our profession. As a book reviewer, beta-reader and copy-editor, I myself am acutely aware that amongst every dozen or so rough stones there is a diamond (to shamelessly use yet another clichéd metaphor). That diamond may be hidden within a low-resolution crust of an exterior, which is offensive to the eye and needs not just polishing, but entirely discarding – of course, I won’t know this unless I dig. Many new authors may be unpublished; they may also be broke financially, unable to commission anything more expensive than some free or cheap Photoshop-alternative. So, rubbing their hands in excitement and anticipation of their new graphic design hobby, they become hands-on and expand their skillset to include book covers. With glee and relish, the author then prides himself that he is able to make a cover and can now do Photoshop-ish. But, is it right? Quite simply, is it good enough?

WHY BOOKS BY UNKNOWN AUTHORS HAVE TO LOOK TWICE AS GOOD – AND BE INSTANTLY RECOGNIZABLE!

By this rationale, is it therefore fair to say that if you are a famous author - probably wealthy with a loyal fan base - we have a right to judge your cover critically and view it cynically, whereas if you are an up-and-coming new face, we should afford you leniency for your budget and withhold judgement until we have read it? After all, for all we know behind that cover may be one of those hidden gems – and, behind some there absolutely, undoubtedly will be. Well, no actually; this is the very reason why you should not expect leniency! You don’t have the luxury of a half-page author name self-selling your new book – you have yet to achieve that status. Besides, the better your book is, the more enticing your cover should be! I designed all of my own book covers, and whilst deeply proud of every single one of them, they have been upgraded and reissued over the years. Why? Because they weren’t good enough to reflect what was inside them. Whilst you should always strive to create the best art you can – both inside and outside of the cover – your book’s cover is invariably little more than a shop window, with one primary objective: to get people inside it. And, even whilst those in the business are less likely to judge a book so harshly by its cover, they are still going to have an inevitable, innate aversion to really bad covers; avoiding creating a terrible cover is a good place for you to start selling your book. In fact, I’ll admit that there is undoubtedly still some degree to which a cover might help me select my next review read. In spite of this, take a look at the BOOK REVIEW BLOG – seek out the books which have been awarded 5-star reviews and take a look at the poor quality of some of their covers; they gave no indication of the immense quality of what I was about to read.

Image property of MJV Literary Author Services

Whilst you are there, by the same inverted principle, look for the lower scoring reviews; those with a professionally created and undoubtedly more expensive high-res cover – it would perhaps be a safe bet to assume that these would have more sales on Amazon than the rough gems do. This is a tragic waste, and all the more reason why a good cover is so important. By earlier asking “is it good enough”, of course the question refers to its defining measure: good enough to sell. As far as the paying readership goes, sadly, and often inaccurately, they undoubtedly judge a book by its cover, if not totally, then to enough of an extent that this factor cannot be simply ignored when conducting your analytics – the number of Amazon sales will probably speak for themselves, as far as professional covers goes. Whilst I am certain there is a huge number of people with the sense to acknowledge that an extremely good quality book may be hindered by its unknown author’s lack of budget, there are also most definitely particular universal expectations of the cover, which are consistent with genre – if you can’t tell your reader how good the book is, at least tell them what it is about, by its cover; at the very, very least, your cover must ascertain genre, even to be visible to your market audience. Too many books hide their action-thriller credential behind a stock cover of a mountain – this means very little to a browsing reader. I earlier mentioned the horror theme, briefly; sci-fi fans will probably expect high-resolution, technologically stunning imagery and artwork; period or romantic readers may be looking for beautiful scenery or lavish, costume-wearing characters; action readers will prefer a gripping, rousing cover, maybe featuring weapons or cash; family drama may invoke expectations of emotional people in melancholy and poignant poses; take a look at the colour themes of other books in yours’ genre, because they all have them… The point is, if there is only one piece of advice to be taken from this article, it is that your cover, at the very least, must be recognizable to your target reader at first glance – or at least enticing - otherwise your marketing work is going to be a whole lot more difficult! When you are rich and famous, your cover might not need to be memorable or even good, but at first glance it will still meet the genre theme, and that will be enough.

A GOOD BOOK COVER IS AN INVESTMENT

As far as goes any degree of importance readers place on the character traits mentioned - perceptive visual importance, stereotypical presumptions, patience, openness to and tolerance of new talent, respect for opportunity, assumptions of financially social inferiority and loyalty – all people are different, and each respects some of these qualities more than others; this is a calculation you must make for yourself, as the author or indie publisher paying to produce your book, and adapt to your buyers’ persona. One thing is clear, though, and probably made more so by looking at the not-so-good books which are selling well, rather than by the good ones which aren’t: a professional book cover may not be a creative necessity, but it is a business one - a relatively cheap investment, too, considering it is your book’s shop window. Take a look at some AFFILIATED COVER DESIGNERS and their rates – you might be surprised.

Posted by Matt McAvoy: 31st July 2019

#book cover#cover designer#author#writer#publishing#books#book creation#judge a book by its cover#ReturnToRealBooks

0 notes

Text

This AntiSocial Life: Revenge of the Outsider

I’m furious today. I’m rarely ever mad but today I’m furious. In the light of the horrifying terrorist attack by an extremist in New Zealand that resulted in the death of 49 innocent people, I’m more furious than I’ve ever been in one of these public massacres. It’s easy to be cold and cynical and let the numbers pass by in the background at work while you move on with your daily life but today I’m stewing in my anger.

Christchurch, New Zealand

A monstrous white nationalist and self-described “eco-fascist” psychopath (and apparently three of his friends) sought to end the lives of dozens of innocent people and succeeded. What followed was the usual cavalcade of cynical bi-partisan political pandering. The side loosely affiliated with the attacker obfuscates any involvement and/or distances themselves from their actions. The other side begins pandering about how the violence proves their arguments right and tries to push legislation that goes nowhere. We’ve all seen this song and dance dozens of times at this point.

What became more frustrating in the hours that followed was the slow realization of just how bad things had gotten. Even beyond the horror that was the Australian Senator blaming Islamic immigration for the massacre, it quickly settled over the situation that the normal debate and bi-partisan dehumanization was something the shooter was actively seeking to perpetuate. In the shooter’s own manifesto he stated that the entire purpose of the shooting was to be as politically calculated as possible to spark mutual disdain and purposely accelerate reactions.

Beyond the obvious uncontionable violence he inflicted on an innocent house of worship, he did everything he could to make his event as infuriating as possible. He used weapons he knew would start firearms debates across the world. He namedropped contentious political and cultural figures like Candace Owns and Pewdiepie. At a time when the edgiest parts of the internet are hotly contested (in Europe, copyright laws are about to become so strict that they could effectively ban memes) he lined the weapons he used with memes just to draw attention to them. He did everything in his power to make sure his act of violence translated into vicious political discourse in a purposeful attempt to get contentious conversations about gun control and social media censorship rolling as a backdoor means of brewing hostility.

We’re at the point in discourse where vicious politics are so predictable that psychopaths can read the room enough to direct the outrage to purposely make discourse of difficult topics more broken. He actually thought he could go as far as to start a race war with his actions. Remember, the second bloodiest war in human history was caused by one man being assassinated. It could’ve worked. We’re already so far beyond the pale already that there’s hardly been any discussion of the actual people who were victimized in the massacre. Nobody cares about the dead and wounded beyond how useful they are as tools for political gain. Ask yourself, what did you hear first: the names of the victims or calls for a political response? For all the discussions of gun control, far right extremism, far left extremism, radical Islam, toxic masculinity, mental health reform, overzealous media coverage and hate speech that spins every time these events happen there’s never a truthful discourse about the most important things that matter. What is causing young men to actually become so nihilistic and disenfranchised in the first place?

The Revenge of the Outsider

I’m primarily a film writer but I do most of my writing for websites that primarily cover politics and religion. Outside of my Flawed Faith series, I very rarely talk about these issues outside of the venues in which I’m generally encouraged to do so. Simply put, I’m not a confrontational person and I don’t want to spend my entire life litigating contentious issues. My entire ethos as an entertainment writer and TV host has been that entertainment is the last bastion of shared culture in the modern world. There is a reason that films become hotly debated topics like Ghostbusters, The Last Jedi and Captain Marvel. People recognize the politicization of films is effective and either see it as useful or as innately divisive. Historically I’ve attempted to stay out of these conversations because they’ve seemed innately useless to me. Today however I need to make an exception.

Prior to today, I’d been deliberating a lot about the messages of a number of recent films. I’d been thinking of it ever since I saw The LEGO Movie 2 last month. That movie crystalized an interesting idea in my mind about the nature of villainy in recent popular films. There's an undercurrent of satire that covers a number of the most popular films of the past several years. In this movie, I finally understood it in the character of Rex Dangervest. Spoiler for The LEGO Movie 2 but it turns out that Rex Dangervest is an older version of Emmet who was lost for several years and decided to take revenge on his friends for abandoning him to suffer alone for years without hope of rescue. In order to do this, he foments hostility between The Man Upstair’s children to cause the LEGO equivalent of the apocalypse as retribution. With this character, I suddenly began to realize how much this story is repeated in recent films.

In Black Panther, we have a version of this with Killmonger, a man who was abandoned as a child by Wakanda after his father betrayed them and who was left alone to suffer in poverty now seeking his claim to the throne as a means of overthrowing the world and fomenting a worldwide revolution.

In Star Wars, we see this embodied in the character of Kylo Ren, a young man once destined to inherit the ways of the Jedi who was failed by every adult and institution in his life except for the leader of the First Order who offered him the opportunity to blow up the system that betrayed him. His most famous lines in the recent movies have all been variations of letting the past die. The moment the power reaches his hands and he takes control of the Imperial Death Cult, all he wants to do with it is reign destruction down on the Galaxy and destroy every institution before him.

Of course, the most famous example of this story is unquestionably The Dark Knight. In that film, the battle of the soul of Gotham City is literally played out by a battle of minds between symbols of order and chaos. It predicted the modern world of escalation and reactionary impulses that drive radical movements across the political spectrum. The Joker in that film doesn’t actually have a singular motivation for his impulse but that doesn’t matter in that film. He’s the embodiment of chaos, meant to call the hypocrisies of the world out as he sees them and create some semblance of equilibrium as he sees it.

It struck me just how frequently this kind of story pops up in modern fiction. What’s interesting in these stories is that at the end of the day, the heroes facing off against these villains ultimately come to the conclusion that society itself is at fault for the disenfranchisement of the villains. The order they perceived in the world was a lie that could only be set straight by ending the circumstances that gave the ideologies of each of these characters are very different, coming from identity, abandonment, oppression of the minority at the fringe of society, etc. What’s important is what they have in common. Regardless of the ideology of the viewer, there is a shared collective sense that society is fomenting the forces that seek to destroy it unintentionally. These characters all share a combined desire to destroy order and rule over the ruins.

Unfortunately, this is the very story we’re watching play out in Christchurch.

The Crisis of Modernity