#dynastic China

Text

🌞 Sun and Moon Pagodas | 日月双塔 🌚

Originally built in Guilin, Guangxi during the Tang dynasty (618-917) the pagodas were reconstructed in 2001.

#chinese culture#chinese history#Chinese architecture#buddhism#pagodas#tang dynasty#asian architecture#China#east asia#east Asian cultures#dynastic china

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

FIRST BUDDHIST PERSECUTION: The emperor orders all Buddhists murdered.

SECOND BUDDHIST PERSECUTION: The emperor shuts down Buddhist temples because the Confucians convinced him that the Buddhists are wrong.

THIRD AND FOURTH BUDDHIST PERSECUTIONS: The emperor attmpets to bust monasteries for tax evasion. The Buddhist monasteries refuse to give up their copper reserves. Things escalate.

0 notes

Text

PSA - Don't Treat JTTW As Modern Fiction

This is a public service announcement reminding JTTW fans to not treat the work as modern fiction. The novel was not the product of a singular author; instead, it's the culmination of a centuries-old story cycle informed by history, folklore, and religious mythology. It's important to remember this when discussing events from the standard 1592 narrative.

Case in point is the battle between Sun Wukong and Erlang. A friend of a friend claims with all their heart that the Monkey King would win in a one-on-one battle. They cite the fact that Erlang requires help from other Buddho-Daoist deities to finish the job. But this ignores the religious history underlying the conflict. I explained the following to my acquaintance:

I hate to break it to you [name of person], but Erlang would win a million times out of a million. This is tied to religious mythology. Erlang was originally a hunting deity in Sichuan during the Han (202 BCE-220 CE), but after receiving royal patronage during the Later Shu (934-965) and Song (960-1279), his cult grew to absorb the mythos of other divine heroes. This included the story of Yang Youji, an ape-sniping archer, leading to Erlang's association with quelling primate demons. See here for a broader discussion.

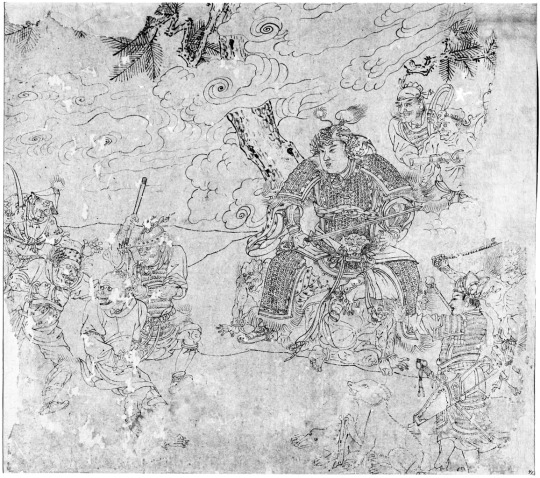

This is exemplified by a 13th-century album leaf painting. The deity (right) oversees spirit-soldiers binding and threatening an ape demon (left).

Erlang was connected to the JTTW story cycle at some point, leading to a late-Yuan or early-Ming zaju play called The God Erlang Captures the Great Sage Equaling Heaven (二郎神鎖齊天大聖). In addition, The Precious Scroll of Erlang (二郎寳卷, 1562), a holy text that predates the 1592 JTTW by decades, states that the deity defeats Monkey and tosses him under Tai Mountain.

So it doesn't matter how equal their battle starts off in JTTW, or that other deities join the fray, Erlang ultimately wins because that is what history and religion expects him to do.

And as I previously mentioned, Erlang has royal patronage. This means he was considered an established god in dynastic China. Sun Wukong, on the other hand, never received this badge of legitimacy. This was no doubt because he's famous for rebelling against the Jade Emperor, the highest authority. No human monarch in their right mind would publicly support that. Therefore, you can look at the Erlang-Sun Wukong confrontation as an established deity submitting a demon.

I'm sad to say that my acquaintance immediately ignored everything I said and continued debating the subject based on the standard narrative. That's when I left the conversation. It's clear that they don't respect the novel; it's nothing more than fodder for battleboarding.

I understand their mindset, though. I love Sun Wukong more than just about anyone. I too once believed that he was the toughest, the strongest, and the fastest. But learning more about the novel and its multifaceted influences has opened my eyes. I now have a deeper appreciation for Monkey and his character arc. Sure, he's a badass, but he's not an omnipotent deity in the story. There is a reason that the Buddha so easily defeats him.

In closing, please remember that JTTW did not develop in a vacuum. It may be widely viewed around the world as "fiction," but it's more of a cultural encyclopedia of history, folklore, and religious mythology. Realizing this and learning more about it ultimately helps explain why certain things happen in the tale.

#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#jttw#Erlang#Erlang shen#Buddhism#Taoism#Chinese mythology#Chinese religion

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note about periodization

I am going to start describing time periods in Chinese history with European historical terms like medieval, Renaissance, early modern, Georgian and Victorian and so on, alongside the standard dynastic terms like Song, Ming and Qing I usually use. So like something about the Ming Dynasty I will tag Ming Dynasty and Renaissance. I already do it sometimes but not consistently. Here’s why.

A common criticism levied against this practice is that periodization is geographically specific and that it’s wrong and eurocentric to refer to, say, late Ming China as Renaissance China. It is a valid criticism, but in my experience the result of not using European periodization is that people default to ‘ancient’ when describing any period in Chinese history before the 20th century, which does conjure up specific images of European antiquity that do not align temporally with the Chinese period in question. I have talked about my issue with ‘ancient China’ before but I want to elaborate. People already consciously or subconsciously consider European periodizations of history to be universal, because of the legacy of colonialism and how eurocentric modern human culture generally is. By not using European historical terms for non-European places, people will simply think those places exist outside of history altogether, or at least exist within an early, primitive stage of European history. It’s a recipe for the denial of coevalness. I think there is a certain dangerous naivete among scholars who believe that if they refrain from using European periodization for non-European places, people will switch to the periodization appropriate for those places in question and challenge eurocentric history writing; in practice I’ve never seen it happen. The general public is not literate enough about history to do these conversions in situ. I have accumulated a fairly large pool of examples just from the number of people spamming ‘ancient China’ in my askbox despite repeatedly specifying the time periods I’m interested in (not antiquity!). If I say ‘Ming China’ instead of ‘Renaissance China’ people will take it as something on the same temporal plane as classical Greece instead of Tudor England. How many people would be surprised if I say that Emperor Qianlong of the Qing was a contemporary of George Washington and Frederick the Great? I’ve seen people talk about him as if he was some tribal leader in the time of Tacitus. European periodization is something I want to embrace ‘under erasure’ so to say, using something strategically for certain advantages while acknowledging its problems. Now there is a history of how the idea of ‘ancient China’ became so entrenched in popular media and I think it goes a bit deeper than just Orientalism, but that’s topic for another post. Right now I’m only concerned with my decision to add European periodization terms.

In order to compensate for the use of eurocentric periodization, I have carried out some experiments in the reverse direction in my daily life, by using Chinese reign years to describe European history. The responses are entertaining. I live in a Georgian tenement in the UK but I like to confuse friends and family by calling it a ‘Jiaqing era flat’. A friend of mine (Chinese) lives in an 1880s flat and she burst out in laughter when I called it ‘Guangxu era’, claiming that it sounded like something from court. But why is it funny? The temporal description is correct, the 1880s were indeed in the Guangxu era. And ‘Guangxu’ shouldn’t invoke royal imagery anymore than ‘Victorian’ (though said friend does indulge in more Qing court dramas than is probably healthy). It is because Chinese (and I’m sure many other non-white peoples) have been trained to believe that our histories are particular and distant, confined to a geographical location, and that they somehow cannot be mapped onto European history, which unfolded parallel to the history of the rest of the world, until we had been colonized. We have been taught that European history is history, but our history is ethnography.

It should also be noted that periodization for European history is not something essentialist and intrinsic either, period terms are created by historians and arbitrarily imposed onto the past to begin with. I was reading a book about medievalism studies and it talked about how the entire concept of the Middle Ages was manufactured in the Renaissance to create a temporal other for Europeans at the time to project undesired traits onto, to distance themselves from a supposedly ‘dark’ past. People living in the European Middle Ages likely did not think of themselves as living in a ‘middle’ age between something and something, so there is absolutely no natural basis for calling the period roughly between the 6th and 16th centuries ‘medieval’. Despite questionable origins, periodization of European history has become more or less standard in history writing throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas around the same time colonial anthropological narratives framed non-European and non-white societies, including China, as existing outside of history altogether. Periodization of European history was geographically specific partially because it was conceived with Europe in mind and Europe only, since any other place may as well be in some primordial time.

Perhaps in the future there will develop global periodizations that consider how interconnected human history is. There probably are already attempts but they’re just not prominent enough to reach me yet. Until that point, I feel absolutely no moral baggage in describing, say, the Song Dynasty as ‘medieval’ because people in 12th century Europe did not think of themselves as ‘medieval’ either. I am the historian, I do whatever I want, basically.

#I was watching an unrelated video about dnd worldbuilding#and out of nowhere someone in the comment section called 1300s chinese people 'ancient asians'#*facepalm*#so I was reminded of this again#rant#colonialism#orientalism#chinese history#historiography

927 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is something you think it is cool or interesting but seems to be underrated?

In terms of egyptology, most of the stuff that isn't publically known. You know like, all the knowledge about Egypt that's in the public consciousness? pretty much everything else feels underrated to me.

People don't want to hear about the workmen's rosters of Deir el Medina, they want to hear about Tutankhamun or Ramses II. People don't want to hear about Tawosret's reign, they want to hear about Hatshepsut's bog standard time on the throne. People are extremely invested in the things that speak to the imagination, such as grand treasure, enormous statues, inscriptions with interesting stories about battles, and less invested in the bits that make up the day to day life in history.

Pot sherds? I fucking love them, not just the ostraca, but also the actual literal pot sherds that can tell us what period they're from by having one very specific lip or rim type. Iconography, epigraphy, being able to look at a relief or coffin and going "oh yeah that's X dynasty because Y bit of iconography, and also two different draughtsmen worked on this piece". The variance in Hieratic signs across dynasties. Grammatical intricacies. Diagnostics in the medical papyri. The fact they didn't have horses and chariots until the New Kingdom, the fact that donkeys weren't used as mounts but as beasts of burden. Flood plains, population numbers, emergence of the state, the economic structure and its development...

But to name one specific example that I think is probably particularly underrated, it's stone quarries. The monuments of ancient Egypt are so evocatively Egyptian, and while people say "wow man how did they even do that" a lot, and the whole "how were the pyramids actually built" keeps cropping up every three months or so, no one really wants to hear or learn about the stone quarries in use throughout Dynastic Egypt.

And if you were asking in general terms, Robert van Gulik's Judge Dee books are extremely underrated lmao. Much as though I've enjoyed Agatha Christie, Van Gulik is objectively the better detective writer. Plus, bonus historical fiction because it's set in T'ang dynasty China*!

*While the eponymous Judge Dee is a T'ang dynasty historical figure, the books actually portray Ming dynasty China in terms of morals and fashion. This is because the books are based on the Chinese work Di Gong'an, which was written in the Ming dynasty, and in these fictional works the historical period is seen through the lense of the time the text was written in. The initial five books in the series are, in that same tradition, always prefaced by a chapter as written from a Ming dynasty official, and it is implied that the story that follows was written down by that official. Which is another reason why these books are cool because as a historian and a writer as well (Van Gulik was a sinologist himself), I think extrapolating your fiction from the historical tradition you're basing it on is fucking lit.

#talking about a general people here#i mean i assume you all are here following me bc you *do* want to hear about all that shit#and i wish i had more energy atm to give it to you but i'm working on it

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA on single-character Chinese names

The usage of single-character names BY THEMSELVES is considered a little odd in modern Mandarin. Multi-character names are fine, for example, Wangji is fine by itself, but if you’re referring to him by birth name, you wouldn’t usually refer to him as JUST Zhan. You will have to use his full name (Lan Zhan), or add a prefix or suffix to the name, like A-Zhan, or Zhan’er. Unfortunately, the Netflix subs of CQL tends to omit the prefixes / suffixes from the names, thus translating A-Ying, for example, as simply Ying. This is an inaccurate translation.

There ARE occasions when single-character names may be used by themselves. For example, when JFM is referring to WWX early in CQL while talking to LQR, he calls him “Ying” and in LWJ’s letter to WWX, inviting him to JL’s hundred day celebration, he also refers to him as just “Ying” near the end of the letter (see below). However, this is somewhat formal dated usage, and is no longer common in modern Mandarin. I believe this is part of a larger evolution of Chinese language away from a more single-character focused lexicon, which I will explain below.

THE EVOLUTION OF CLASSICAL TO MODERN CHINESE

The modern spoken form of Mandarin evolved from an olden form of written Chinese, which I’m going to refer to as classical Chinese for simplicity’s sake (I believe historians actually have different names for different eras of ancient written Chinese). At the same time though, modern Mandarin is VERY different from classical Chinese. Classical Chinese is pretty much like... an entirely different language from modern Mandarin. I’m going to quote this meta which I encourage you guys to read in full for an analysis on LWJ’s speaking style:

文言文 wenyanwen / classical/literary Chinese is related to but distinct from modern Mandarin… Modern Mandarin Chinese as we know and learn it today in classrooms is something that didn’t really get codified until the 20th century… classical Chinese can be summed up, like most things in Chinese, with a four-character idiom: 言简意赅 yanjianyigai. Broken down, we get:

言 yan - words, speech

简 jian - simple, brief

意 yi - meaning, intent

赅 gai - complete, full, comprehensive

Classical Chinese (which is heavily focused on single-character root words, thus condensing a lot of meaning into a relatively short sentence) was largely a written form of Chinese used by elites. Historians do not seem to believe that people spoke classical Chinese, but a vernacular form of Chinese which we don’t have record of. Typically though, languages tend to become increasingly diverse over large swaths of land, which leads to the emergence of dialects native to different regions. As a result, people from different regions may not actually understand each other.

However, China was united as a kingdom over vast swaths of land for many periods in dynastical history. It had a political system where magistrates stationed in even the faraway reaches of the kingdom reported to the emperor and his cabinet of ministers in the capital. As such, if you wanted to be a magistrate, you would have to learn this written form of Chinese, and take the imperial exam to be selected for the position. As a magistrate, you would be expected to correspond with officials from other regions in this written form of Chinese. This written form was thus able to bridge the differences in spoken Chinese.

But according to my Chinese teachers!!! (Disclaimer: they are high school language teachers, not Chinese history professors, so I cannot completely guarantee the historical accuracy of these claims,) When modernization happened, transportation became more advanced and urbanization became more and more of a thing. Thus, society saw a greater intermingling of people from different regions who couldn’t necessarily understand each other in spoken Chinese. This necessitated the emergence of a new common spoken tongue. Modern Mandarin, which is often referred to as putong hua (lit. common language), was thus born.

THE MOVE FROM SINGLE TO MULTI-CHARACTER WORDS

According to my Chinese teachers (see previous disclaimer again), modern Mandarin basically moved away from the single-character focused lexicon of classical Chinese, towards increased usage of multi-character words. For example, the modern word for “conflict” 战争 is made of root words 战 and 争 both of which rooooughly mean “conflict” as well. In a classical lexicon, the root words would likely be used by themselves, but modern Chinese mostly uses multi-character words.

And this, according to my Chinese teachers, was to improve the understandability of spoken Chinese. Chinese language has a GREAT NUMBER of homophones, which can get REALLY FUCKING CONFUSING. The Zhan (战) in “conflict” sounds exactly the same as 站 (to stand) 占 (to occupy) 湛 (as in Lan Zhan), and more. As such, while the root words 战 and 争 may carry the intended meaning perfectly well in writing, in speech, they individually sound like a bazillion other words. Which thus necessitates these multi-character words. 战 may have many homophones, but 战争 has a great deal less homophones.

So why do we generally not do single-character names in speech anymore? BECAUSE IT CAN GET REALLY FUCKING CONFUSING. Like if you wanted to say something as simple and functional as “go to Zhan” (去湛那边), the Zhan of his name (湛) is a perfect homophone for 站 (to stand), so it literally just sounds like “go stand there” 😭😭😭 At least if you use his surname (Lan Zhan), a prefix (A-Zhan), or a suffix (Zhan’er) it becomes a whole lot clearer that you’re referring to a person.

THE TLDR;

This is a very long and roundabout way to say: please don’t replicate the Netflix subs in your fics. If you’re referring to someone with a single-character name, add a prefix or suffix to the name, like A-Cheng, or Cheng’er, or else use the full name, Jiang Cheng. Multi-character names are generally fine, for example, Wanyin, Wangji, or Xichen are all fine. Wuxian seems to be a little bit of a grey area. It does not seem to be used by characters in the novel, probably because it sounds like 无线 (wireless), which is the reason why the Chinese fandom likes to refer to him as “WiFi” 🤣

476 notes

·

View notes

Text

WoT Musings: S2 Episode 3

GETTING CHILLS

This is one of my favorite sequences in TGH, one of my favorite Nynaeve moments, hell probably one of my favorite series moments, and I want them to nail it so bad.

Looks like the first test is going to be about Nynaeve loosing her father and mother. Makes sense since she never faced Aginor and Balthamel in the show. The choice was about letting go of the desire to persue revenge and fight, to choose being Aes Sedai over that.

Interesting choice to make the new 'Wisdom' Natti Cauthon instead of figment tyrant. It makes what's happening cut a little harder.

'How is Rand. is he happy?' FUCKING OUCH

Offfffffffff. On one hand they don't have a whole episode to commit to this bit, so their having to use shorthand hand.....but DAMN is that some knife twisting. I dig it though. Instead of a tyrant Nynaeve could fight off, it's something she can't fix because of her own block, her anger and fear. She has to choose between cold empty comfort for a dying man....and going back to seek the power to do actual good. Very very clever.

OHHHHHHHHH THAT THIRD TRIAL DO HAVE THOUGHTS

THE SOUTHERN TWANG ON THAT SENCHAN VOICE IS WOOF

Bye Uno! I would feel bad, but I'm afraid you're a funny bit part that's an easy sacrificial lamb here. It was gonna be you or Masema, and he's got problems to cause Perrin latter, so it's you!

I am really really REALLY digging the mix of Dynastic China and Versailles Era France in Cairhien's design in the show.

I am going to need SO MANY FICS of Logain and Rand fucking nasty during that garden scene you have NO IDEA

Asmodean is a going to be a good teacher to Rand solely because Logain is going to set the bar so fucking low.

Lanfear putting forward this chill cool innkeeper lady persona in Cairhien only to invade Rand's dreams to show off the true depths of her crazy where it's safe to do so, and ALSO to trick Rand into burning down her inn and thus leave him feeling guilt ridden/indebted to her is SO ON BRAND

Elayne and Egwene's friendship is already making me So Happy. I can't wait till we get Elayne and Nynaeve road trip shenanigans later on in the series.

Nynaeve's Acceptatron test is something I am going to have to sit with. I really really like the fact that just like in the books she let the arch fade away the first time, and I really like that once again it was HER that forced it to come back by channeling, something she wasn't supposed to be able to do in the test at all. The important part of this choice in the book is that it's Nynaeve DECIDING to go back, to claim the power she needs to protect those she loves, choosing that over paradise. The show's choice to instead demonstrate that such a paradise would be empty and fleeting if she DID choose it, is....one I am going to have to chew on.

Overall the show continues it's trend of adapting the core of the books, while changing the details to better suit the new medium, and I'm board with that.

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

What type of clothes did Chinese maids wear? Did they wear ruqun styles and wear their hair in two buns?

Hi, thanks for the question, and sorry for taking ages to reply!

The most common depiction of a maid in dynastic China, as often seen in books and tv/film, is that of a girl wearing ruqun with hair in double buns. However, in real life, Chinese maids' clothing and hairstyles changed according to fashion trends through history, so there's no one definite way to describe how they dressed. Generally, their clothes and hair were simpler as expected of their status, and they were also more likely to dress androgynously (x). For more specific details, you'd have to narrow down the time period first. I have a servant tag as well as a maid tag (for female servants in particular) that you can check out for more information and visual references. To give a few examples, below are depictions of maids from several different dynasties - note how they vary in style:

Southern dynasties court maid (x):

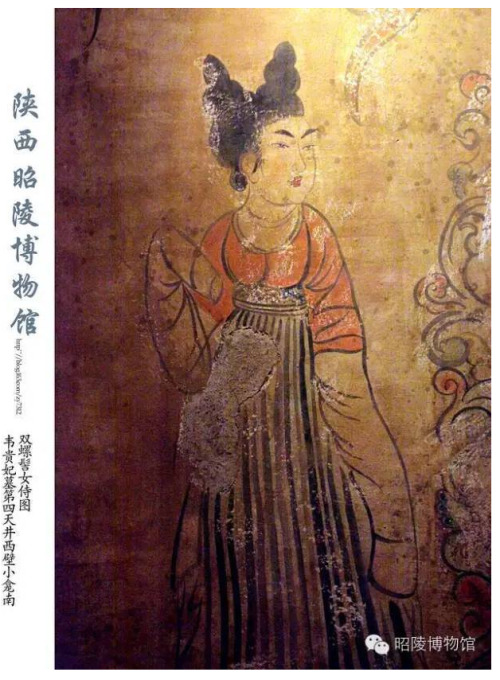

2. Tang dynasty court maid (x):

3. Song dynasty palace maids (1, 2):

4. Ming dynasty maid (x):

Hope this helps!

#hanfu#maid#servant#history#reference#ask#reply#>100#china#chinese fashion#chinese clothing#chinese culture

144 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re: hanfu: speaking on robes, it's not just my perception I'm going off of. I threw it into a couple of search programs to make sure that my opinion wasn't biasing it too much, and really, all that comes up is bathrobes, perhaps western fantasy on occasion. Yes, the word covers many different types of clothing, but conventionally, at least in terms of a Western audience, I don't believe that hanfu (or anything in that realm) is one of them.

2. Wuxia/xianxia canons are frequently set in ahistorical fantasy ancient China, so precise historical accuracy is often either handwaved or vaguely alluded to, and ahistorical references or articles of dress are fairly common.

I also don't mean to call all ancient Japanese clothing kimono, obviously. I'm using it as an example of a common, non-western broad category of traditional clothing that often pops up in fiction that has had its name directly romanized from the source language, that also is really just a broader type of clothing with oft-ignored categories.

Could people be more specific about its use? Yes, of course. But I do think it's at least less Americanizing to at least try, as opposed to handwaving it with "she wore a long robe" or something of the ilk.

3. I am Chinese, yes. I wasn't aware that hanfu blogs were saying that, however. While I can understand that opinion, I honestly don't think it matters so much re: the specifics as long as it's being popularized and actually used in the first place. And of course, context matters. A diatribe on the details of dynastic clothing would hopefully aspire to more accuracy than some random MDZS fluff fic on ao3. Sure, there are other, more specific types of clothing, and I wouldn't object to someone deciding to specify by throwing in paofu or something. But in the end, at least using the "approximately" right category's better than nothing, imo.

Is it a little wrong (or a lot historically inaccurate) to be calling xianxia-fied costumes hanfu? Sure, in some cases. Are they not applicable at all?

Well, I mean, if you're referring specifically to the Untamed, I recall there actually being a fair amount of clothing (whether it be from main/side/extra characters) that do fall into the category of hanfu. Certainly, some have some fantasy modifications that wouldn't follow ancient etiquette, but it's not nearly that indistinguishable. There are a lot of characters wearing clothes that aren't even particularly fantastical; you could pop them into the set of ROTK 1994 as long as you changed up their hair and some other details.

Picking hairs at it reminds me of seeing a lot of non-Chinese people criticizing some girl's qipao, while a bunch of Chinese netizens were just happy to see a qipao at all.

--

Nonnie, what? 'Robe' is a standard term for discussing anything from a thawb to a gunlongpao in English.

If bathrobes turn up in search results more, it's probably because more of them are for sale.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Qu Xiaofeng’s wedding dress in Goodbye My Princess was inspired to some extent by the “court ladies” statues from the Tang dynasty (618–907).

#china#chinese culture#east asia#chinese history#cdrama#chinese drama#hanfu#tang dynasty#wedding Hanfu#chinese wedding#dynastic China#goodbye my princess

318 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi hi, it seems like a few people ran to you due to chaos happening in LMK fandom, (nothing new) but I do have a question if you do not mind answering. Do you have any research links that not closely related to JTTW/FSYY?

People only provide JTTW/FSYY as if it’s ‘end to all meets’. But there’s so much more than that.

It doesn’t surprise me that people are coming to me to discuss those issues, but I truthfully have no interest in LMK or the fandom. It became very clear to me that people depend heavily on personal headcanon or, as you said, JTTW and FSYY holding a lot of water they really can’t. I’ve said it before but both stories were written by two different people in different time periods (the Ming and the Qing Dynasty respectively).

If you’re looking for other literature that concerns the same pantheon (assuming it’s the Daoist pantheon you’re interested in) and not solely Sun Wukong or Nezha, I can happily recommend reading Mountains and Seas Classics, The Lotus Lantern, The Emergence of the Universe as numerous gods exist once the universe does (the theory is split between the universe being born from a cosmic egg or a divine corpse), Pangu Born From the Cosmic Egg, the Separation of Heaven and Earth, Nüwa Repairing the Broken Sky, Shooting Down the Surplus Suns, and many other stories, deities, and even how China saw the Heavens and how the deities developed alongside the idea of the Heavens influencing the dynastic cycle.

I’m more than happy to discuss such myths if requested, as well as describe the many many deities that get “sidelined” because of how JTTW and FSYY were written and then held on the pedestal of the “be all end all”. The scope of when these stories were told and shared is massive and incredibly fluid, so numerous versions of these stories (and even JTTW and FSYY) exist. Daoism did not exist within a vacuum, and the many ethnic groups had their own unique identities in how these stories were retold.

Being so rigid and unwilling to accept different interpretations will truly only hurt you in the long run.

#chinese religion#chinese mythology#chinese folklore#chinese literature#chinese history#chinese culture#lmk discourse#lego monkie kid#lego monkie kid discourse

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'M FROM THE CENSORATE AND I'M HERE TO HELP

#chinese history#middle dynastic china#chinese history shitposting#control agency#cory doctorow#shitposting

0 notes

Note

Why does Zhu Baije wield a rake as a weapon? Is there some sort of symbolism, or did some ancient Chinese guy just think it'd be cool?

That's a good question. My guess is that the storytellers who developed Zhu Bajie thought it would be funny to associate a farm animal with a farming tool.

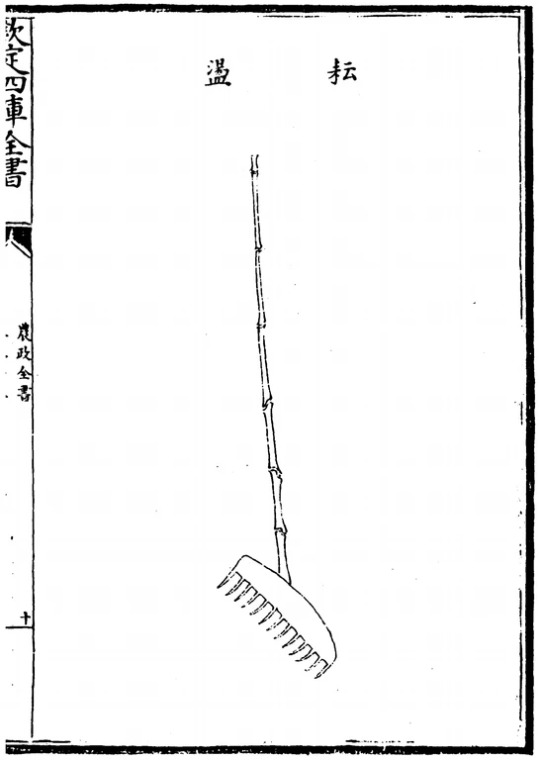

The rake imagery goes back to the Yuan dynasty, as evidenced by this Cizhou ware ceramic pillow.

The kind of rake that he carries is similar to the "hand yarrow" (yundang (耘盪), a bamboo-handled rake with metal teeth designed to weed rice crops. It appears in The Book of Agriculture (Nongshu, 農書, 1313), which was written in response to the devastation that the Mongols had wrought on China during the Song and Yuan dynasties. So the featured tools were meant to help make life easier for farmers toiling away in the fields (Bray & Needham, 2004, pp. 59-60).

What's interesting is that published dynastic sources depict Zhu's rake differently. For instance, the original 1592 edition of JTTW illustrates it as a war rake.

And Mr. Li Zhuowu’s Literary Criticism of Journey to the West (late-16th-c. or early-17th-c.) depicts it as a toothed club:

By the way, I saw your prior question. I don't know much about the subject. Sorry.

Source:

Bray, F. & Needham, J. (2004). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology; Part 2 – Agriculture. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

I find it funny that Portugal is disappointed on not beheading Netherlands when he got stranded on the Islands of Japan Lol...

😂 lmao, Port tried—he and Johan/Jan (Ned) were technically at war back home then—Eighty Years War, and all, thanks to Port’s dynastic union with Spain that the fledging Dutch Republic was rebelling against. it seems to be the reason the Portuguese Jesuits in Japan were hostile to the crew of the De Liefde. for the Dutch, it probably helped that from the Japanese POV, they appeared fucking pathetic by that point; even though the ship had some impressive guns, like 4/5 of the original crew had died, and many of the survivors were weakened by scurvy and malaria and had to be helped off the ship when they reached Japan.

further, Kiku (and historically, the real soon-to-be shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu) is no stranger to this kind of political shit-stirring and rivalries between nations. Some things really are the same on either side of the Eurasian landmass. Hell, he himself recently got beaten up (deservedly) by Yong-soo and Yao (in Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s hubristic attempt to invade Korea and China). I like to think that puts Kiku in a more cautious mood when De Liefde gets shipwrecked. And from Kiku’s POV, he doesn’t owe Port anything, even if Jan was intending to fuck Port up (as he would later)—they’re not allies, it’s a more pragmatic trading dynamic (guns etc). He’s well aware of Port’s own imperial ambitions in the region, and if this new guy who washed up might be a good way to establish trade relations with other nations to counterbalance Port if he causes trouble...well why not make sure this strange new guy doesn’t die of scurvy and question him a little about European politics?

honestly, as I see it, it starts out rather pragmatic—and neither Kiku nor Jan realise just how enduring and deep their relationship is going to become. all of it beginning from that fateful meeting in 1600 that could so easily not have happened, or gone very differently.

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, big fan of your blog! read some of your qianqiu metas, and was thinking lately about the presentation of the statist consolidation of power and framing of political unification as an unproblematic moral good in a lot of the wuxia/xianxia I've engaged with. having grown up with these genres, I know that censorship and sociopolitical circumstances are big influences on the message that gets put out. (1/3)

but also as an anti-authoritarian looking to art and literature for countercultural inspiration, I guess I've found a lot of wuxia lacking in a vision for a radical future. this certainly isn't to say that art needs to be radical to have value, or that wuxia spaces haven't created avenues of self-expression and joy for oppressed groups in an airtight society where there are dire risks attached to political activity. (2/3)

wuxia/xianxia are my favorite genres, but many aspects of its narratives seem to uphold structures of oppression (i.e. ableism, colorism, xenophobia, misogyny, etc). but hey, 嫌货人才是买货人, no such thing as perfect, best thing to do, I suppose, is to engage with art with a critical eye. thanks for your time! (3/3)

an anon after my own heart, hello! you're definitely getting at certain themes, assumptions, and values that in a way were built in to the wuxia genre as it has evolved today. whether you’re reading classic authors like 金庸 Jin Yong or remixers like 梦溪石 Meng Xishi, I’ve definitely noticed that wuxia as a genre has, well, complicated relationships with the structures of oppression that you brought up

(I'm leaving xianxia out of the discussion atm as I’m less familiar with it as a whole, but also I don't think it has the same concerns of nationalism and historicism that wuxia does)

in many ways, the modern wuxia genre is a heavily compensatory genre, which I mean specifically in a “hey, compensating much?” kind of way. it took me a very long time to realize and process this, diaspora kid that I am, but so much of contemporary Chinese culture is still profoundly affected by the events of the past 200-250 years. I mean, when you think about it, the imperial dynastic system wasn’t all that long ago; in many ways, Chinese society is still reeling from the century of humiliation, the breakneck industrialization, the mass deaths of the 20th century in war and famine and revolution and government abuse (there is also the matter of the government deliberately evoking public memory of past atrocities to fan nationalistic sentiment for its convenience, which not only keeps historical national humiliations top-of-mind but also disrupts processes of collective memory and collective grieving).

Stephen Teo, in Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition, tracks the origins of wuxia as a genre, and from the beginning wuxia has been bound up with anxieties over masculinity and national agency, which in literature can often be one and the same. Teo, in tracing early forerunners of wuxia and the historical context of its emergence, notes that "[i]ntellectuals initially regarded the warrior tradition in the genre as one of the elements that could provide a positive counterweight to China's image as the 'sick man of Asia'" (Teo 37).

Given the repeated incursions and invasions onto Chinese soil and China’s status as a semicolony for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, it’s almost too obvious how the wuxia genre provides a balm for those exact anxieties: the martial warrior tradition (the 武 wu in 武侠 wuxia, if you will) directly addresses fears regarding the emasculation of Chinese men; the historical settings of wuxia novels often set during or against a backdrop of past imperial Chinese glories; the featuring of military triumphs over “foreign barbarians” who sought to invade or occupy imperial land, or even better — the protagonist, raised among the “wolfish barbarians,” is uniquely positioned to combine the “raw, savage strength” of “barbarian” culture with the “cultured civility” of Han Chinese culture; the strong emphasis on tradition(al aesthetics) and traditional Confucian ethics of morality and righteousness as contrast and counterpoint to the rapid modernization and Westernization of 20th/21st century Chinese culture... you get the idea

Teo’s book surveys the wuxia genre over the past century, particularly through film, and he discusses how wuxia in the 21st century begins “to manifest as made-in-China historicist blockbusters mixing the epic form with wuxia" — which is to say, wuxia has increasingly become intertwined with the genres of period dramas and historical epics:

"Having been grafted onto the period epic, wuxia becomes a showcase of Chinese history, seeking to be universally accepted while at the same time locating itself within the historicist confines of the nation-state." (168)

wuxia’s increasing hybridization/conflation with historical epics (particularly in Zhang Yimou’s 2002 film 《英雄》 Hero, John Woo’s 2008 - 2009 《赤壁》 Red Cliff duology) increasingly politicizes the genre, and that politicization thereby links wuxia to national issues of structural oppression, like the ones you mentioned: the statist consolidation of power and framing of political unification as an unproblematic moral good, ableism, colorism, xenophobia, misogyny... any one of these could carry a research paper on their own, and I don’t presume to be able to solve or explain away any of them in a tumblr post, but I do think there are many ways in which the wuxia genre’s (often uncritical) support of structures of oppression are directly linked to the origins of wuxia as a genre that was in many ways wish-fulfillment for a 20th/21st century Chinese culture wracked with political turmoil, economic disaster, and cultural uncertainties

I particularly like Teo’s discussion here:

"...The grand historicist self-fashioning of the genre in a film like Hero and its offshoots Curse of the Golden Flower, The Banquet, The Warlords [...and] Red Cliff demonstrate the kind of nationalistic self-aggrandisement that critics find so disturbing, particularly so when the nature of the regime is authoritarian and autocratic, ever ready to invoke militaristic power as the means to their end of a unitary nation state.

“However, if we see the wuxia genre as a mirror of the nation, it shows China in perpetual crisis, torn apart by internal strife and the urge to cohere as a unitary state." (186)

the framing of political unification as an unproblematic moral good is something I find particularly interesting, because a lot of that has to do with Chinese history. the famous opening line of 《三国演义》 / Romance of the Three Kingdoms references this directly: 天下大势,分久必合,合久必分 / “All great movements under heaven [follow this rule]: that which has fallen apart for a long time must come together, and that which has been together for a long time must fall apart.” The entire cyclical narrative of imperial China has been this: a dynasty rises, a dynasty falls, the land fractures into squabbling kingdoms, out of which a single dynasty eventually rises, to eventually fall, to eventually fracture again. and so, a dynasty’s collapse and the subsequent societal fracturing into warring territories is naturally paired with the crisis and violence that ensues with the fall of a state. simply put, there just isn’t a period of Chinese history (or if there is, I don’t know of it) where political fragmentation has not been associated with civil unrest; therefore political unification must be an unproblematic good as it eliminates domestic warfare and returns order to the central plains. handily, this supports the current regime’s nationalistic and authoritarian agenda, and so we see this particular moral value reflected in much of wuxia fiction

not to simply brush aside ableism, colorism, xenophobia, and misogyny all with a wave of a hand, but I do think that much of this has to do with contemporary Chinese society’s current attitudes towards these issues. when a society privileges pale complexions in its beauty standards (see: the triptych of 白富美, the omnipresence of beauty products that advertise skin tone lightening, the entire entertainment/idol industry), colorism is a natural (and shitty) result. government-spurred nationalism, historical racism, and Han chauvinism all contribute to the rampant xenophobia of much of Chinese media, especially when it comes to depictions of non-Chinese Asia (Central Asia, Japan, SE Asia in particular). when wuxia needs a faceless enemy, it reaches for the barbarians on the border. ableism and misogyny are issues that contemporary Chinese society struggle with now; the issue of ableism in particular feels stifled in the cutthroat nature of the current job market (the flipside of China’s massive labor force is the knowledge that every person is fundamentally replaceable), and the depths to which cultural misogyny runs in China is growing steadily more and more evident as the gender gap widens

and when it comes to fiction, when it comes to literature, widespread change often doesn’t occur until there is a societal call for it. I’m thinking of the U.S. science fiction and fantasy scene, which went through its own reckoning with diversity and genre-reified prejudice over the past decade and a half. and now we have brilliantly diverse authors and searingly postcolonial works, queer characters on the regular, Tor Books itself advertising to us soft sad queer freaks on tumblr. the journey wasn’t easy though, nor is the journey remotely close to over, but the fact remains — there was, in a sense, a collective cultural awakening about the ways in which more classic SF/F often utilized and reified racism, prejudice, misogyny, ableism; and subsequently, there was a conscious effort towards holding the genre(s) and its creators accountable, towards writing and supporting and amplifying voices previously shunned and silenced

and, well, to be fully honest, I don’t think that cultural moment has arrived yet for wuxia. this is not to say that there are no wuxia creators out there trying to decolonize the genre, but that we haven’t reached the turning point where decolonizing the genre and examining its history of misogyny, xenophobia, ableism, and colorism is expected, accepted, even celebrated, and I don’t think we’ll get there until contemporary Chinese society goes through a cultural reckoning with these same issues

I also think it’s worth mentioning that whatever that collective cultural awakening/reckoning looks like, it must be and will be distinctively Chinese. Chinese culture maintains different moral values from Western (Euroamerican) culture; contemporary China faces different social issues and political problems than contemporary Euroamerica. whatever this journey looks like, I don’t think it will look like or should look the same as what the U.S. went through/is going through. decolonizing/deimperializing East Asia is inherently different from decolonizing/deimperializing the West, so I would like to stop short of making prescriptive statements on what that cultural turning point should look like

that being said: if anyone’s run into some good postcolonial wuxia lately, I’d be VERY interested to hear more about it

#ack this got long#please take my armchair political/social theory with a Costco container of garlic salt#both Teo and this great article about 英雄 get into the whole political messiness of tianxiaism which is FASCINATING but also TOO MUCH#I do think a major reason why I didn't enjoy 'saving your kingdom while burnt out' much is because of the rampant nationalism#which I think is absolutely fascinating on a theoretical level — the Ni Zhange article dissects it thoroughly#like the absolute galaxy-brain daring of priest to rewrite an alternate historical steampunk version of the century of humiliation#but at the same time.........#moof I didn't really talk about danmei or gender but I ONLY HAVE THE ONE THINKY TAG#hunxi thinks about danmei and gender#心怀杂念 字数无量

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural Diversity?

Okay so, I've seen some criticism about the 'lack' of diversity in AtLA: Netflix Addition.

Are you blind!!!

Starting off with the costumes... they are literally ripped straight from the source material. You have Inuit, Japanese, Indian/Sri Lankan, Indonesian, and several Chinese Dynastic interpretations represented in the Earth Kingdom. The Fire Nation itself is a mix of some of these things. So I'm not sure what people are complaining about.

Bumi's Palace, for example, has elements of both Hindu and Middle Eastern (even Moorish) architecture. There are some designs that reminded me of Alhambra in Spain.

Roku's temple... Japanese, Southern China, and some Taiwanese architecture. Like I guess it takes someone with half a BA in Fine Arts to see this, but these criticisms are seriously flawed.

My goodness, Kyoshi Island is basically a Japanese fishing village. You have people wearing Yukatas and Hoaris for crying out loud. Even the homes you see are very Japanese. It was purposely designed that way because Japan was the inspiration behind Kyoshi.

The Water Tribes are so Inuit they even got a well know Native American actor to play Chief Arnook.

Like I'm not getting it?

Am I spinning lose wheels here?

#this is coming from someone who spent a lot of time authenticating art and cultural aritfacts#dont take it personally#cultural diversity is not the shows problem#avatar the last airbenber netflix#avatar the last airbender

16 notes

·

View notes