#anti-psychiatry

Text

i think we should always take predominant sexes and races for psychiatric disabilities into question.

are men really more likely to be antisocial or narcissistic, or are women just overlooked because ASPD/NPD are seen as too "aggressive" for them?

are women really more likely to be borderline or histrionic, or are they just seen as so "hysterical" that they have to be feminine?

are black people more likely to have schizophrenia or ODD, or are labels of "psychosis" and "defiance" simply used to further dismiss, oppress, and imprison BIPOC?

are white people more likely to have autism and ADHD, or are doctors just more willing to accept that white children are disabled and not just "bad?"

oppressive biases are everywhere in psychiatry. never take psychiatric demographics at face value.

#hi i'm back. i got covid and also into anti-psychiatry#anti-psychiatry#antisocial personality disorder#narcissistic personality disorder#borderline personality disorder#histrionic personality disorder#schizophrenia#oppositional defiant disorder#autism#ADHD#sexism mention#racism mention#antipsych#ASPD#NPD#BPD#HPD#ASD#antipsychiatry#anti psychiatry#anti-psych#anti psych

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Patient-Therapist's Anti-Psych Manifesto

Okay yall, I broke out my laptop for this, so buckle up, I’m about to have opinions.

I don’t owe anyone my credentials, but because I know the first thing out of some folks’ mouths is always “what gives you the right” let’s nip that in the bud right now.

I have been in and out of psychiatric care since I was seven years old. I have severe medical trauma from the experimental treatments I was subjected to, and have spent time in outpatient, inpatient, and all manner of different kinds of care. I’m also a published anarchic anthropologist, and a fully credentialed and actively practicing private therapist. To many, these are rightfully mutually exclusive roles. To me it is survival. Let’s explore some dialectics.

Dialectic: Per Merriam-Webster, a dialectic is any systematic reasoning, exposition, or argument that juxtaposes opposed or contradictory ideas and usually seeks to resolve their conflict : a method of examining and discussing opposing ideas in order to find the truth

In this case, we’re holding a few irreconcilable realities in tension with each other and working to resolve those irreconcilabilities.

Dialectic 1

Creating a class of healthcare professionals whose job is to dispense care to the masses inherently creates a hierarchy.

Any hierarchy that exists can and will become unjust under enough stress, with enough bad actors, with enough systemic intersections, if it is made so, etc.

People still need healthcare, including mental healthcare.

Dialectic 2

Because we already have unjust hierarchies involved in our medical care and research system, the question of who gets to define what is “mental healthcare” and what isn’t is inherently skewed in favor of kyriarchical** values.

Kyriarchy: a social system or set of social systems built around domination, oppresion, and submission

Many non-hierarchical forms of mental health care are devalued in our society and therefore do not receive the resources to operate at scale despite being extremely effective tools.

There will likely always need to be some form of “service” healthcare model in our society, even if it is wildly different from what we have now, because the worst person you know deserves care and it may need to be from people who are incentivized to provide it, and in privacy or isolation from others in the community.

Dialectic 3

Indefinite and involuntary detention can never be ethically or humanely performed. Period.

Some people need episodic or long term intensive care that comes from having someone available to them 24/7, and this is extremely difficult to provide at scale to an entire society in their homes, and your answer cannot be to offload the work onto relatives.

Current inpatient and residential programs typically serve, at best a holding pattern, and at their worst are breeding grounds for abuse and we will be hard-pressed to create models that do not replicate this pattern in our current systems.

We could keep going several layers deeper, but this is already getting long, so now I want to ask the next question.

These all feel really impossible to work with, Butts, you said I was supposed to reconcile all this and that feels super intimidating. What do we do with these dialectics?

Great question imaginary reader!

There are a lot of things you can do about it! Start by going to the Blackfoot digital library and watching this video about indigenous influences on modern concepts of the basic hierarchy of needs (link)

One of the things I’ve learned as an anarchic anthropologist turned therapist is that if you take what we think we know now about mental health, the nervous system, and chronic stress, and look back to this moment when Maslow and the Blackfoot community tried to communicate the resiliency of their community to the world, we can learn a lot.

A huge amount of mental health care, in my experience, boils down to learning how to regulate your nervous system, provide for your hierarchy of needs in your life, including the accommodations you need for your physical, cognitive, spiritual, and social world, and seeking, traditional or non-traditional therapy, pharmacology, and/or traditional medicine for the remainder of your needs.

What I mean by this is: mutual aid is mental health care, socializing with your friends is mental health care, taking a bubble bath is mental health care

But so are practices like MAST (link)- a non-hierarchical therapy style that allows people to support each other through therapeutic interventions via mutual aid (a genuine therapeutic concept we discuss in our training!!)

I imagine a world where we dare to question all of our assumptions about what therapeutic intervention needs to look like. Where “mental health care” looks like creating a society that seeks to meet every level of need for as many people as possible, and offers additional, voluntary community built and operated services to meet additional needs that arise.

What if we worked to minimize the need for inpatient services by providing ADL support crews for anyone who requests it? Need to just be a lump in bed for a week in order to be okay at the end? Ask for a crew to come do dishes and make meals and tidy and field calls and check in on you. Feeling manic and need someone to be your impulse control? Request one. Like theoretically these are things we can all do for each other regardless, but what if there were trained volunteers from the community, motivated and available who could be on call whenever they were needed for anybody no matter what? What if you didn’t NEED to have a friend who was available? What if you didn’t need to wonder if they would be annoyed because everyone is there by choice and by specialty?

Imagine if you didn’t have to wait until you were in crisis to call? You could just do it because you needed or wanted the help and that was fine too. Because the goal was prevention. Make sure no one gets so overwhelmed or stressed that they reach crisis in the first place. Make sure everyone has community resources.

The task rabbit mutual aid is the one I think is the most under-served in our communities. I think a lot of us are still afraid to truly take that last step into anarchic community building. After all, time is the most precious resource we have, and giving that to others without a guarantee of others giving back feels very scary. When I’ve done task-rabbit type mutual aid though, it’s always been my favorite experience, and I truly cannot recommend it enough. It provides such an immeasurable boost to the entire community’s resiliency.

I think another really useful direction is teaching yourself a little bit about polyvagal theory. It sounds like pop science, but it’s pretty cool stuff. Things like diaphragmatic breathing, certain manual manipulation techniques, etc can help you regulate your nervous system in moments of stress or intense emotion, as well as adjusting you into a better regulated state over time if you experience chronic dysregulation, such as from PTSD, ADHD, or Autism**

**This is not me saying it will cure your ADHD or Autism, it will not, but it can tone down the intensity of emotionally/autonomically dysregulated moments, or make them a little easier to end on your own time.

In the end, mental health, like so much, is deeply personal. There will be no "one size fits all" option. But we can create a society that provides a high quality standard of living for everyone, with the majority of their needs being met as a baseline, and create services that account for needs that may be episodic, additive, or unusual, as will almost certainly always eventually occur.

So the question is, when you begin to imagine outside the confines of the four walls of the psychiatrist's office

What does mental healthcare look like to you?

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mental health diagnoses are capitalist constructs

“Mental and physical diagnoses aren’t objective facts that exist in nature, even though we usually think of them this way. While the experiences and phenomena that fall under different diagnostic categories are, of course, real, the way that we choose to categorise them is often influenced by systems of power. The difference between ‘health’ and ‘illness’, ‘order’ and ‘disorder’ is shaped by which kinds of bodies and minds are conducive to capitalism and the state. For example, the difference between ‘ordinary distress’ and ‘mental illness’ is often defined by its impact on your ability to work. The recent edition of the DSM, psychiatry’s comprehensive manual of ‘mental disorders’, mentions work almost 400 times – work is the central metric for diagnosis.

“When we look across history, it becomes even more obvious that diagnosis is tied to capitalist metrics of productivity: certain categories of illness have come in and out of existence as the conditions of production have changed. In the 19th century, the physician Samuel A. Cartwright proposed the diagnosis of ‘drapetomania’, which would describe enslaved Black people who fled from plantations. While we might think of drapetomania as a historical outlier among ‘true’ and ‘objective’ diagnoses, it is underpinned by the same logic as other diagnoses: it describes mental or physical attributes that make us less exploitable and profitable. In the 1920s, medical and psychological researchers became interested in a pathology called ‘accident-proneness’, which was applied to workers who were repeatedly injured in the brutal and dangerous factory conditions of the industrial revolution. Dyslexia, a diagnosis I have been given, also didn’t emerge until the market began to shift from manual labour towards jobs that relied on reading and writing, when all children were expected to be literate. Despite having problems with reading, I understand that in a world where reading and writing weren’t so central to our daily life, there would be no need to name my dyslexia, no need to diagnose it.

“As a system of state power, many of us rely on diagnosis to get the material things that we need to survive in the world. When illness or disability interferes with our ability to work, we often need a diagnosis to justify our lack of productivity – and for some, diagnosis is the necessary pathway to getting state benefits. If we want to get access to medication, treatment or other healing practices provided by the state, diagnosis is also the token that we need to get there. This is made all the more complicated by the fact that doctors have the power to dispense and withhold diagnoses, regardless of our personal desires. When it comes to psychiatric diagnosis, most of us know someone who has had to fight or wait for years for a diagnosis that would improve their quality of life – particularly in the realm of autism, ADHD and eating disorders. The internalised racism, sexism, classism or ableism of doctors often gets in the way of our ability to access the diagnoses that we want and need. Then there are those of us that are given diagnoses that we reject, a process that we also have no say in ...

“When we understand that psychiatric diagnoses are constructed, contested, and aren’t grounded in biological measures, the idea of ‘self-diagnosis’ starts to feel less dangerous or controversial. Self-diagnosis is grounded in the idea that, while the institution of medicine may hold useful technologies and expertise, we also hold valuable knowledge about our bodies and minds. I know many people who have found solace and respite in communities for various diagnoses, even if they don’t have an official diagnosis from a doctor. These spaces, which respect the wisdom offered by lived experience, can be valuable forums of knowledge-sharing and solidarity. Self-diagnosis also pushes against an oppressive diagnostic system that is so centred around notions of productivity.”

#anti-psychiatry#psychiatry#psychology#mental health#mental illness#mental disorders#diagnosis#mental healthcare#healthcare#neurodivergence#drapetomania#dyslexia#autism#adhd#benefits#disability#capitalism

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. The beginning of ‘modern’ psychiatry – a descent into hell

This examination of the beginnings of modern psychiatry well into the first half of the 20th century does not provide us with momentous breakthroughs and heroic efforts to assist mankind. What we find instead is a subject based on speculation rather than science, unable to establish causes of mental illness and whose primary solution was to murder the very people it should have been caring for.

#psychiatry#false science#anti psychiatry#eugenics#anti psych#mental illness#mental health#anti-psych#anti-psychiatry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PDA Has No Place Within Neurodiversity

Something you’re likely to come across in online autistic self-advocacy spaces is PDA-otherwise known as pathological demand avoidance, or to some, pervasive demand for autonomy. This is not a new idea-in fact, it has been present in the field of psychology since at least the 1980s, before the neurodiversity movement began in earnest. You can see discussion of PDA in autistic spaces from the late 90s-including skepticism of the idea. It is not an official diagnosis listed in the DSM or the ICD. Some people want it to be. It is considered by some to be part of the autism diagnosis, much like PDD-NOS and Asperger’s, which used to be separate diagnoses in the DSM-IV. I’m unsure whether these advocates wish for PDA to be like that or for it to appear under autism. I think either way, it is not a good idea. There are several reasons why I am against the idea of PDA. I think the condition itself is too broad and more importantly, I am afraid of the implications behind it.

The way I see PDA described leaves open a lot of room for interpretation. This could lead to an overdiagnosis (or false diagnosis altogether), though that’s not so much of a concern of mine as it is that there are many reasons why someone may refuse demands or ignore obligations. It could be as simple as executive dysfunction-which I believe is diagnostic criteria for autism and ADHD. People describe PDA as extreme anxiety someone feels when given a task to complete. Again, there are several possible explanations for this behavior-simply chalking it up to “PDA” doesn’t really tell you much. Ok, someone tends to avoid demands-perhaps to a disabling degree-but I feel like the reason for that goes much deeper than just calling it PDA. A lot of things I do probably qualify as PDA to those who believe in it. I have a harder time than most staying on task or starting something I have to do. Also, no, framing it as a “pervasive demand for autonomy” does not change anything. If I don’t want to do something I’m asked to do, it’s definitely not because I only ever do things I want to do. It can sometimes mean that, but it still hardly qualifies as “PDA”. So this leads me to my next point, the implications of PDA.

There are two main concerns I have with the implications behind a PDA diagnosis or label. Not only do I think it’s not specific enough, I am worried about how people use it as an excuse for genuinely shitty behavior. While this does happen with a number of disabilities, including autism, the broadness of PDA, as I previously described, only accentuates this. I’ve already seen it happen. I’ve seen somebody accuse people for their “PDA acting up” simply for not addressing an issue to their satisfaction. That leads me to the second issue-how staff could (and likely already do) use it against people in their care. Pathologization already leads to this in institutional settings. If, hypothetically, someone with a diagnosis of PDA doesn’t stick to their behavior plan, or generally just doesn’t follow directions, the staff could just shrug it off as PDA instead of thinking more critically about the actual cause of their behavior. Alternatively, they could use that against them. This is far from an unrealistic expectation. This already happens with other disabilities. This would just make it worse. Calling it a “pervasive demand for autonomy” would yield the same result. This is also the issue with Cluster B Personality Disorders, which are actual diagnoses. The psychiatric system exists to pathologize and strip people of their self-determination. This isn’t to say the entire DSM is invalid-just that there's a severe power imbalance at play here.

There are traits that are distinctively neurodivergent. Even then, just chalking behaviors up to diagnosis is unhelpful. However, there’s enough evidence that a neurodivergent brain works differently from a neurotypical brain to justify calling it autism, ADHD, tourettes, etc. PDA is not that. It reeks of Asperger’s and PDD-NOS. I thought we were done using Asperger’s? Apparently the only reason why many people don’t like Asperger’s is simply because of Hans Asperger possibly being a nazi and not for the actual issue with it-which was the false sense of hierarchy and separatism that came with it. Supporting the use of PDA is proof of that.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone describing ASPD criteria to me: holy shit that me🥰

Someone discribing ASPD criteria to me: holy shit that me💀

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Even before DSM-V was released, the American Journal of Psychiatry published the results of validity tests of various new diagnoses, which indicated that the DSM largely lacks what in the world of science is known as "reliability"-- the ability to produce consistent, replicable results. In other words, it lacks scientific validity. Oddly, the lack of reliability and validity did not keep the DSM-V from meeting its deadline for publication, despite the near-universal consensus that it represented no improvement over the previous diagnostic system. Could the fact that the APA had earned $100 million on the DSM-IV and is slated to take in a similar amount with the DSM-V (because all mental health practitioners, many lawyers, and other professionals will be obliged to purchase the latest edition) be the reason we have this new diagnostic system?"

(The Body Keeps The Score, 2014. Van Der Kolk, page 166, 167)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tell me I’m wrong in saying psychiatrists are the cops of the mental health world. Say something wrong or offkey and they’ll send you to jail.

#alter: xiv#anti-psych#anti-psychiatry#for the record#hating psychiatrists doesn't mean hating medication#its just the truth

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

aside from the arrogant and patronizing assumptions it makes, it's really strange to me that people say "suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem" like that's a bad thing. isn't a permanent solution good? why would i want a solution with an expiry date?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

my ex psychiatrist really was like „this person is so fuuuuuucked uuup operate their fucking brain!!!!!!!!“

#why do i joke about this#this is why it’s best for me to stay to myself#😂#psychiatry#anti-psychiatry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man, I know like all psychiatric diagnoses are like basically kind of arbitrary but Oppositional Defiance Disorder feels like an esp. bullshit one. I mean it’s like among all these serious difficulties navigating daily life they just threw in Hates The Cops Disease. It’s some hysteria shit.

Like “oh sorry dad, I can’t serve in the military, turns out I’ve got Too Cool 4 School Syndrome.”

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

"When, twelve years ago, I first went to prison, I began to remember what I had heard and read about convicts, prisons and prison reform. I knew that Thomas Mott Osborne had spent a week of voluntary imprisonment in Auburn (New York) Prison. I had read the book in which he describes what he experienced and learned during that week. One of the things he learned was that crime is due, among other things, to the individual criminal's maladjustment to his environment; from which Mr. Osborne concluded that crime is a problem in abnormal behavior for the solution of which society should look to the psychiatrist. I knew, too, that leaders in penological thought considered this idea sound and were trying to reform American prisons in accordance with it. It seemed to me that it was an idea which ought to meet with ready response from the convict, since it offered him a chance to learn what, as a maladjusted individual, was wrong with him; and a chance, with the help of the psychiatrist, to readjust and eventually to rehabilitate himself. But I heard, to my great surprise that, for the most part, my fellow convicts were unfriendly to the idea that there was anything wrong with them or that they needed any help from the psychiatrist. I found that their typical attitude was very aptly illustrated by the dictum I have already quoted: "Bug tests are strictly the bunk!" Upon what, I am asked, is this attitude based? What lies behind this contempt for and hostility toward the psychological tests and the psychiatric examinations? After a great deal of close contact with every known type of criminal, I believe that I can answer these questions.

At the very outset, it is well to bear in mind the fact that the average prison inmate is keenly aware of some of the purposes of these tests and examinations. He knows, for example, that if he fails to make a good showing in the psychological test he may be classified as incapable of holding certain desirable intramural jobs. He knows, too, that if the psychiatrist discovers him to be abnormal in his mental or emotional reactions, or antisocial in his attitude toward law and order, he may be classified as incapable of so conducting himself in the free world as to be safely recommended for parole. He knows, in other words, that the psychiatrist and the psychologist have the power (from his point of view) to hurt him. To the extent, moreover, that he fears somehow that he is feeble-minded or queer, and believes that the discovery of his true condition will result in his transfer to a less desirable institution, he concedes to the psychiatrist and the psychologist even greater power to hurt him. Out of this knowledge arises a fear of the mental specialists and of the tests themselves.

This is one fact which underlies the average convict's attitude toward tests and examining specialists. Another fact, the importance of which is not generally understood, is that the average convict regards the psychologist and the psychiatrist as representatives of law and order. He fears, hates, or is bound by the underworld code at least to pretend to fear and hate policemen, prison guards, and other enforcers of the punishing law and order. He makes no subtle distinctions. The warden, the chaplain, the prison physician, any one in authority unless he clearly demonstrates his friendliness is the convict's natural enemy; and thus he numbers the psychologist and the psychiatrist among his enemies.

This hostility toward the officials who represent law and order is based upon reasons which, from the viewpoint of the criminal, are entirely logical. As all experienced criminals know, crime thrives best in social darkness and needs a grim secrecy. Even the younger and less experienced criminals know that it is dangerous to give information about themselves to their enemies, the enforcers of law and order. Thus it is that such axioms as "Keep your mouth shut!" and "Death to informers!" constitute the first and second commandments of the underworld code of behavior. This means that the average criminal deems it not only weak and foolish, but positively dangerous, to be honest and truthful in his dealings with any individual from the ranks of his enemies; and since he usually considers the psychologist and the psychiatrist his enemies, he is pretty sure to be dishonest and untruthful in his dealings with them. This is a fact which these examining specialists will do very well to keep in mind.

There is, finally, the general attitude of the convict toward plans to reform him. Without going into a detailed discussion of this attitude, it is perhaps sufficient to say that the convict is, on the whole, indifferent to any plan of prison reform which does not promise an immediate amelioration of his own present condition. He is not interested in any far-reaching, general plan for classifying and segregating criminals for society's benefit. To such a plan he is often deeply hostile and at best lazily indifferent. He is interested only in plans which promise immediate and personal only in plans which promise immediate and personal benefit to himself; such as better food and entertainment, or a shortening of the length of his imprisonment. Since the psychological tests and the psychiatric examinations not only do not promise him any immediate, personal benefit, but, on the contrary, threaten to bar him from a soft prison job or a chance for release on parole, he is not merely suspicious of them, but actively opposed to them.

The convict is thus seen to have developed an attitude of fear, hatred, active antagonism toward the tests and the examining specialists.

- Victor F. Nelson, Prison Days and Nights. Second edition. With an introduction by Abraham Myerson, M.D. Garden City: Garden City Publishing Co., 1936. p. 271-273

#words from the inside#prisoner autobiography#prison days and nights#victor nelson#history of crime and punishment#reading 2024#prison psychiatry#psychiatric examination#psychiatric power#research quote#rehabilitation#failure of rehabilitation#classification and segregation#psychiatry#penal reform#american prison system#anti-psychiatry

0 notes

Text

these in depth report of the medicalisation of ADHD by the manufacturers of adderall and the spurious science behind the drug is uh, enlightening

#anti-psychiatry#tldr adderall has very little scientific backing and the company historically and currently spends millions promoting ADHD

1 note

·

View note

Text

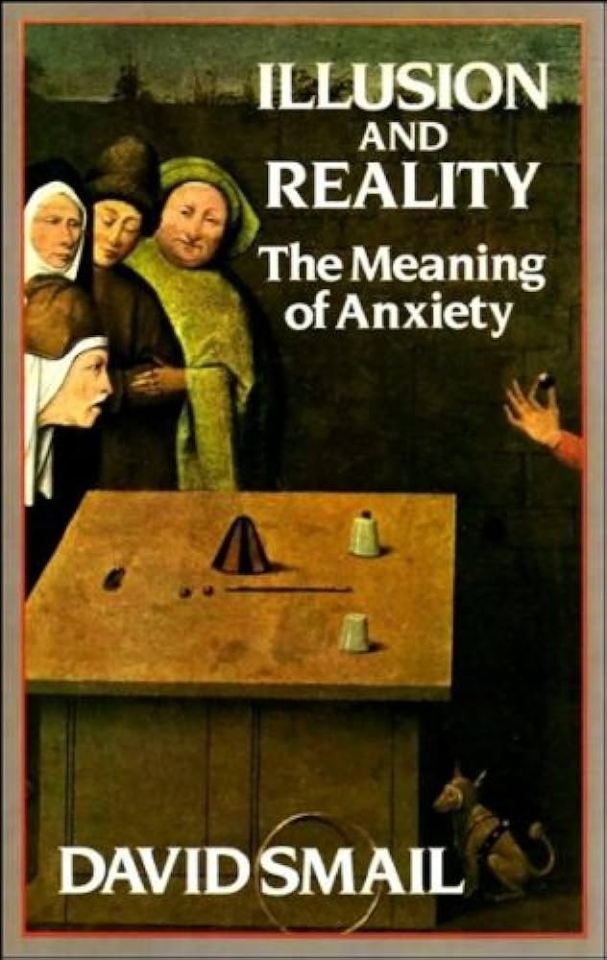

"We tend to blame only those we have not taken the trouble to understand."

#David Smail#Illusion and Reality#Anxiety#The Meaning of Anxiety#NHS#Psychotherapy#anti-psychiatry#psychology#Smail

1 note

·

View note

Text

i'm just thinking abt how many providers i've had who heard my story abt psychiatric abuse + immediately individualized it. "oh, you're so smart + kind+ obviously sane! you didn't deserve that! i can't believe they gave you that diagnosis when you're obviously not like that! they shouldn't have treated u like that when all you did was xyz! they shouldn't have assumed you were crazy like that!"

there is always a third person haunting this interaction- the patient who does deserve that, who is "actually" that evilscary diagnosis, who did Have To be treated like that. if i want to soak up the affirmations of these providers, i must be careful to never become this third person. i must affirm myself by setting myself apart from her- i did not deserve to be treated like that because i am not like that.

i reject this. not only was i like that, she + everyone else like that deserve everything i deserve. they are my siblings + my friends + my lovers. i do not need to cut them out of me to believe i deserved better. i refuse to comfort myself through the lens of someone else's dehumanization. the tragedy is not that psychiatric violence was applied to someone who not insane enough to warrant it. the tragedy is the violence.

#this is sooo common in prison stuff too#like our obsession with the falsely convicted#the third person in the room is the prisoner who deserves to be tortured#anti psychiatry

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Neurotypes are social constructs as they are the interpretation of neurology.

For instance is autism a disability or is it another form of diversity. Well it depend on who you ask. That because autism is a social construct.

DID/OSDD1/pDID is just a shattered personality form trauma or is it multiple people in your head.

Are cluster B disorder abusive or are they a consequences to childhood trauma.

The interpretation of neurology is a social construct not a biological reality. Neurodivergent people are the final authority on the interpretation of neurotypes. Not neuroscientists, therapist, the government or psychiatrist.

#Anti-psychiatry#neurotypical#neurospicy#neurodiverse stuff#neurodivergent#neurodiversity#neuroscience#therapists

1 note

·

View note