#anime industry

Text

Finally watched the CSM opening, I'm blown away by the animation but it's more worrying than exciting. These shots are insanely detailed in animation and compositing, and there's already been reports of worker abuse at Mappa - a (french) article I read two days ago interviewed an animator saying they had to animate a whole minute by themself (for comparison the dayly average for hand drawn animation in France is around two seconds) and has contracted carpal tunnel syndrome at the layout stage. That is, the first stage of planning after a finished storyboard. This is before actually animating all frames.

Given Crunchyroll has also been exposed recently for paying it's dub actors a few hundreds of dollars per person, per role, and that regarding Mappa, actual information about working conditions are mostly kept secret, it could be way worst.

This isn't to say don't watch Chainsaw man, it does look extremely dope and beautifully made. But if you're enjoying the show and others like it, and are genuinely passionate about animation, please try to be mindful of the conditions in which these shows are made. I don't think I'll be able to watch it myself after learning about this without a ball in my throat and for now will opt out.

Translated excerpts from the linked article below.

To meet Mappa studio leads, you need to [present yourself as harmless]. Some topics, like working conditions in the studio, are taboo.

Mappa's style goes against traditional Japanese animation's style, most often semi-realistic. A demanding style, not for everyone [...] With eight series currently in production at Mappa and animators "in a state of utter fatigue", it is hard to follow this market undergoing constant expansion.

Mappa's working conditions are getting more and more called out [among animators]. "If you don't talk to the animators you will never hear about the working conditions", laments one of them, under the cover of anonymousity.

While Mappa does not necessarily pay more than other studios, its productions often have higher budgets. And if animators from all around the world rush to work there it's because of the aura of these projects. "That's precisely why I am not working for them," says a big name from the industry. "I find that Mappa abuses of the aura it has to enslave young people, who are fans of animation and of these franchises"

#chainsaw man#anime industry#it's the dashboard killjoy who can see the workload behind the cartoons again hi everyone

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I Worked on JUJUTSU KAISEN (Part 1)

This video was a long time coming and I'm sorry that it had to be two parts. I hope this video will provide a bit more insight of what it's like working on anime (in light of recent conversations about Studio Mappa and the overall working conditions in anime). Hopefully I can put out the second part soon. Until then, please be kind and give your support to the artists and production peeps who make your favorite pieces of media.

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think MAPPA has ruined an entire generation of anime watchers.

Yeah.

People should NOT be expecting their level of animation when you have brutal scheduling and low budget. No, I'd say watching the TV series of Neon Genesis Evangelian should be mandatory, not for the story, but what to expect when a show is running out of money and time.

Yes, you should be expecting a "slide show", aka a bunch of stills when you give staff a month or less to complete an entire episode. There should be shots of still characters with their heads turned away from the camera so mouths aren't even animated when you give an animator a day to a week to get a shot done. There is a REASON limited animation is used. But now people expect more and more without there being a change to anime scheduling or pay. Like every episode needs to be full of sakuga every second or else.

People are getting burnt out and the whole damn industry is collapsing, y'all.

#rant#anime#anime industry#mappa#hell animation industry in general#sometimes i get so mad yall#i see first hand how it affects ppl and it constantly makes me want to scream#i haven't even ranted about line milage yet either#that's a whole nother anime rant#also part of this is me getting annoyed at seeing ppl complaining about dungeon meshi#trigger is doing fine#like go watch some older anime#it is 3 in the morning and my brain woke me up with FEELINGS#probably delete this later

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

#anime#animation#sakuga#anime industry#yokohama kaidashi kikou#takashi anno#magical emi#ajia-dou#tomomi mochizuki

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

#cats#cat#anime and manga#anime#manga#art#anime community#manga community#animeblr#mangablr#cats are the best#cats are great#anime industry#cat meme#cat memes#cat humor#cat shitposts#funny but true#funny because it's true#meme#memes#tumblr memes#animemes#anime memes#anime humor#anime shitpost#manga meme#animal memes#animal humor#cats tumblr

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just got done watching a video on the state of the anime industry (spoilers: it's a fucking travesty) and it reminded me...

every once in a while, I remember the blog sailormooncrystalfailures (which apparently still exists?? haven't posted since 2021 tho) and while they may have had a point in the quality of Sailor Moon Crystal's animation sometimes (emphasis on "sometimes"), knowing what I know now about the industry, they come off in hindsight as really, REALLY dickish*

The people in the anime industry actually animating this shit have to push out stuff every week for sometimes as low as (the equivalent of) $5 a day. SMC was actually semi-lucky to have a bi-weekly release schedule as opposed to weekly. Of course some of the shots looked like ass, they had to rush it. You think the CEOs and investors gave a shit about the people at the bottom?

"haha animation bad. r these guys amateurs or something 😂"

Fuckin hell...

[This Anime Exposed a $28B Slave Operation]

[Animation Dormitory Project]

(and please don't come on here with a 'this is why they need to unionize!' reply. it's not that simple. basically, they did... at toei... not at the dozens of other studios AND a lot of other labor is outsourced. basically, it's too fractured for unions to make a difference. the whole system is effed)

*i mean they came off like that back in the day too (they'd literally start using in-between shots as "proof" of lack of effort), but still

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

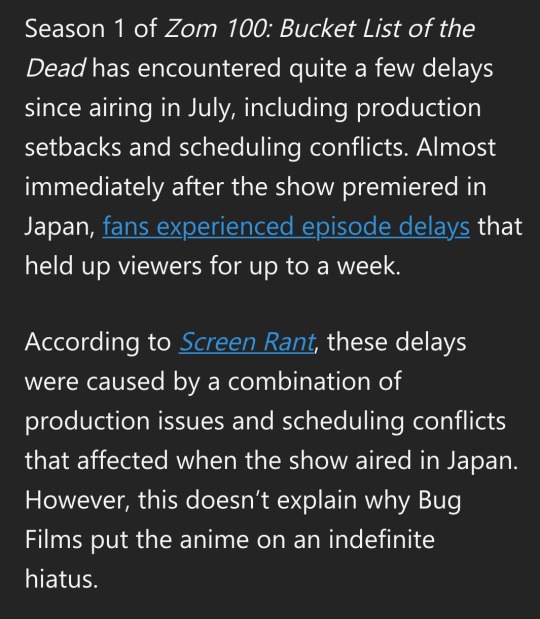

The anime about how the aggressive exploration of workers is dehumanizing, isolating and alienates them from their labor and traps them in cycles of abuse where they can't afford to leave, nor have the time to look for another job.... where the main character had a job at a production company.....

Has been delayed permanently due to *checks notes* "production issues" the irony is palpable

#Zom 100#Anime#Anime industry#It could be a normal reason#But also the last time an anime was delayed this significantly#It was because Cloverworks put someone in the hospital due to overwork#So. Im not optimistic

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway fuck the animation industry for exploiting artists

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#oof#anime#anime japan#japanese politics#anime industry#invoice system#tax increase#anime studios#anime production#voice actors#animators#japanese culture#Not about JJK#I know that thumbnail got me too#share#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Worked on Jujutsu Kaisen PART 2

Apologies for the long wait, everyone. Hope it was worthwhile!

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know why Jojo part 6 released in three batches of 12-14 eps many months apart instead of weekly like the previous parts?

Disclaimer: I'm not working on that series and I don't work for or with Netflix in any capacity, so please know everything I say here is just educated guesswork based on my experience in the anime industry at large, plus some logical observation thrown in.

But tbh? I'm guessing it's due to Netflix's dogged adherence to binge-model streaming.

In recent history, Netflix began licensing anime from Japanese licensors in a bid to enter the very lucrative anime space (valued in the tens of billions as of 2021). They kept their licensed titles in "Netflix Jail" until they could release the entire series in a binge-ready batch, foregoing weekly releases entirely. The "binge model" of streaming has worked well for them in the past, and they saw no reason to break from this tradition when they first started licensing simulcast anime in-season.

Carole & Tuesday, Beastars, and others received this treatment. The shows aired in their entirely in Japan, and months later, Netflix finally released them (with multiple foreign language dub options) in a big batch. Alas, anime fans accustomed to same-day simulcasts weren't happy they couldn't watch these series weekly during their seasonal debut (hence the term "Netflix Jail" entering anime community parlance). Because Netflix wanted to do batch-releases, fans missed out on the initial hype concurrent to the series' Japanese TV debut as a result.

I imagine most fans who wanted to watch a series would just pirate it rather than wait for Netflix to release it from Netflix Jail and drop the whole thing at once months after it aired (I know I did with Carole & Tuesday). Because there was no legal way to watch the series, these series weren't as widely reviewed for American audiences during the peak of the hype surrounding them. The lack of media hype + rampant piracy likely ate into Netflix's bottom line once the series were released on the platform. People had already watched the shows by the time Netflix released them from Netflix Jail, making them old news.

Since Netflix is a business, they were likely interested in figuring out how to better monetize their content and prevent preemptive piracy. That leads us to current-day-Netflix's behavior surrounding anime simulcasts.

The series I talked about above were largely licensed by Netflix. Licensing a show means buying the rights to these shows after the shows are funded (AKA produced) by Japanese producers, licensors and studios. Netflix owns the rights to stream these series, but they don't own the shows themselves. They couldn't prevent them from being aired in Japan since they didn't actually own the shows.

More recently, Netflix has been installing themselves as a producer on shows, rather than just a licensor of them. That is, rather than buying the streaming rights to a series, they've been putting down money up-front and funding the production of the anime they've been buying. They are co-producing, which gives them more control and power over the series as a whole. In short, they own all or most of the series.

Two recent series come to mind: Ooku the Inner Chambers and JoJo Part 6. Both of these series debuted on Netflix (Ooku is an exclusive Netflix production and ONA). In the case of Jojo Part 6, it was shown on Japanese TV after it debuted exclusively on Netflix.

Because Netflix has a controlling stake in these shows, they can control how and when they are released. They're going to release the series in the way they think will make them the most money. Because batch-releases and the binge model have worked well for them, they organized the release of JoJo Part 6 around this strategy. They premiered it on Netflix in a binge-ready batch of episodes, rather than rolling it out weekly. Then, afterward, they gave it a weekly release on Japanese TV. By preventing the show from airing on TV before it arrived on Netflix, they basically prevented pirates from "leaking" the episodes before Netflix could get a bite at them. This move made Netflix the first and simplest place to consume these series.

Basically Netflix wants to stick to their binge-model when possible. With anime simulcast licensing, you just can't do that without missing out on simulcast seasonal hype and inviting piracy of shows before you can air them. Anime simulcasts are basically incompatible with the binge model...

... unless you're rich enough to change the game, and turn "Netflix Jail" into just... Netflix.

If you own the show, you can control how it's released. Netflix removed JoJo Part 6 from the simulcast game completely and structured its release on what they thought would make them the most money. They think (and probably have numbers that suggest) people subscribe in order to binge new shows. By breaking Part 6 up into batches, they have three "binge cycles" that'll earn them customers each time.

Long story short: Netflix controls their content based on what they think will make them the most money, and for them, that's the binge model.

Obviously they're doing SOME weekly rollouts (mostly with their reality series), but Netflix still appears to be prioritizing bingeable content, and they haven't shifted over to weekly simulcasts for anime.

In the future, I expect they'll back away from simulcast licensing and do far more co-producing when it comes to anime. We'll likely see most "Netflix anime" being released as platform-exclusive (or ONA) content with a delayed TV release in Japan. Licensing simulcasts that get stuck in "Netflix Jail" earns them ill-will from fans who prefer same-day simulcasts. Owning the series by co-producing, rather than just stream-licensing, makes more sense for them and their binge-model business practice since they can escape the simulcast and piracy trap baked into the simulcast model. They can do whatever they like with the series they own... even if it flies in the face of anime fans who prefer simulcasts to the binge model.

Capitalism ruins the party again, I suppose. Hope this helped!

(Disclaimer: I understand there were long delays between the parts of Part 6, and that could be Netflix trying to drag things out, but it's also likely there were production issues. I can't say for sure, but the anime world is still suffering a lost of delays because of COVID, so... throw that in there and you have a recipe for long-delayed batch releases. But I can't speak to the specifics of this project.)

#jojo's part 6#jojo part 6#netflix#JoJo's Bizarre Adventure: Stone Ocean#anime#anime industry#simulcasts#netflix jail

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Through some stroke of luck I managed to see notices the “Anime Lockdown” “online convention” would be putting on another streaming presentation...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#anime#animation#sakuga#anime industry#tatsuya ishihara#george wada#manabu otsuka#masao maruyama#mitsuo iso#kyouko kotani#mizue ogawa

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#animation#mappa#studio mappa#anime#anime and manga#anime community#animeblr#current events#social justice#human rights#workers rights#animation industry#anime industry#video essay#chainsaw man#csm#attack on titan#shingeki no kyojin#aot#hells paradise#tumblr recommendations#recommend#recommendation#youtube recommendations#video recommendation#youtube#youtube content#youtube link

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Future of Anime Staff: A Foggy Forecast

This is a topic that I've really wanted to talk about for quite some time, and I was sat around thinking about what it was that I wanted to post today. So I figured screw it, I'll write that post now.

The plain and simple is that the anime industry is changing at a far quicker pace than it used to. Not that this change is new, but that it's happening faster. Think of the industry as a candle. Rather than a different candle being used, our candle is just burning far faster than it was. And I'd love to dive into the details of that.

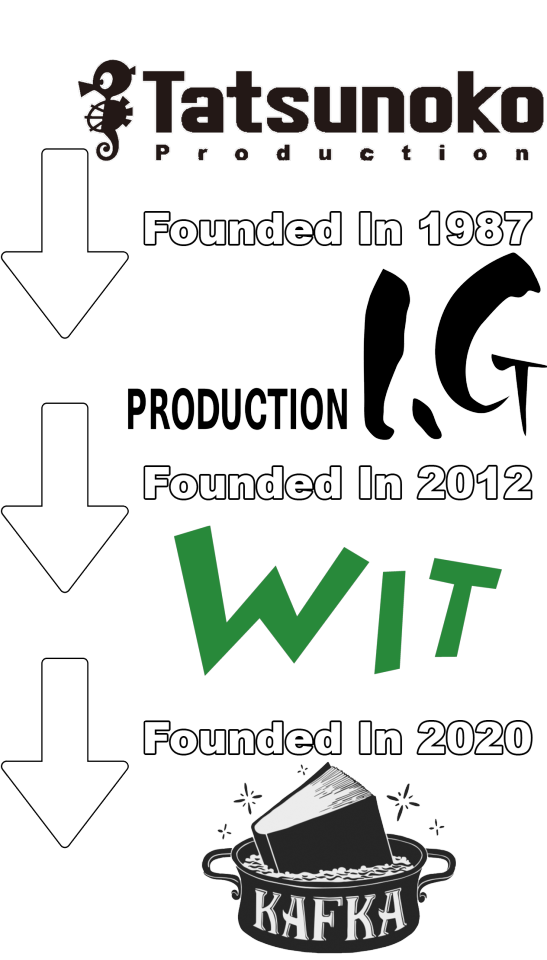

So, a faster pace of change, how can you say that? Well, the easiest marker is the creation of new animation studios from anime veterans. I mean, WIT was formed from Production I.G veterans, and Mappa came from Madhouse. And from there, Production I.G came from Tatsunoko Production, and Madhouse came from Mushi Production.

But we haven't stopped at this level yet, rather than going one further back, we're going on further forward. From WIT studios sprung Kafka, and from Mappa we have E&H Production. To help illustrate what I'm about to explain, please take a look at this (poorly made) graphic.

I think what's most apparent is the gaps in time between the formation of studios. Taking the Mushi Production side as an example, Mushi Pro was founded in 1961 while Madhouse was founded in 1972, making for a difference of just 11 years. Madhouse to Mappa is a far larger gap though at nearly 40 years. From there, it's a measly 10 years to the formation of E&H Production.

Looking at the Tatsunoko side, the studio was founded in 1962 while Production I.G appeared in 1987, making for a difference of 25 years. From there, WIT is founded in 2012 making for a difference of once again 25 years. Following WIT however, Kafka appears after only 8 years of WIT as a studio.

Overall, the numbers speak somewhat for themselves in broader strokes to how the anime industry has grown and changed. Though there was a reasonable era in the industry of stability and maintainable growth, in recent years that growth has been less sustainable.

More series are being produced, more staff members are unsatisfied with their working conditions, and so new studios are created. Now, there's a totally different conversation to be had about why new studios is the way for veterans to find creative freedom and less oppressive schedules, but that devolves into how producers view and interact with the anime industry.

Anyways, the point is that unsatisfied workers are more and more common, and branch and child studios appear more and more frequently. Just look at how BUGS FILMS spits a bit of fire at their parent company OLM via some little details in Zom 100.

So, to the heart of the issue: what the hell does this have to do with the title? Well, great question me! The point is this: veteran staff are no longer remaining veteran staff for the required amount of time. You're not seeing high level staff members stick around with specific companies for longer periods of time. Similarly, we've seen production companies catapult the number of anime series licensed in a year well into the stratosphere, shown via this information from all the way back in 2021 about Kadokawa licensing 40 series a year until 2023.

So where does all this go, where does it all lead? Two roads. The first, overworked and undercompensated staff that will put out subpar and error-riddled work due to crunch times and other issues. The second, constant staff movement that erases the middle of the hierarchy.

If anime production is expressed in tiers you'd have three of them. The highest tier being directors, series composers, etc. etc. The next tier would be episode directors, script writers, assistant directors, and whatnot. The bottom tier would be LO, In-between, and even key animation.

Of course, you can't go from bottom tier to top tier in one go, and each tier used to require specific experience and ability. You'd need reasonable experience with episode direction to transition to lead director, sufficient experience with key animation to move to animation direction, a number of years with a given studio, etc etc.

The issue that this ridiculously expanded production produces is, simply put (as I did before), the erasure of the middle tier and the transition requirements to the top tier. A nasty side effect is the disappearance of studio employees as freelance work dominates, and as @444lpblue has effectively put, the blurring of lines in regards to studio style. More on that later, lets look at some examples of the former points first.

Shota Goshozono is the lead director for Jujutsu Kaisen Season 2. They've also only been in the industry for 8 years, and have a total of 5 episode direction credits prior to JJK S2. And Mappa shows through this decision how not to handle a new director.

Yes, you read that correctly. A total of 8 years in the business, and only a grand total of 5 episode direction credits prior to JJK S2. Even more interestingly is that their career starts with and is fleshed out at A-1 Pictures. They did some key animation on Mob Psycho, and some other work on the Cloverworks end of FGO stuff, capping off their freelance work with two episodes of Ousama Ranking before arriving at Mappa with JJK S1.

Yes, once more, you read that correctly. Gosso's first experience with Mappa was in 2021, and in 2023, after a total of 3 episodes directed under the studio, they're in the lead seat for Jujutsu Kaisen.

I think it's an understatement to say that it's a bit of a shocking development. I mean, to fill the shoes of Park it's a pretty ludicrous decision. Park is pretty well as close to Mappa royalty (even though they've only directed a total of 3 series) as you'll come across as they begin their tenure with the studio in 2014 working on Terror In Resonance. Just to sort of emphasize for context: Park started working with Mappa a year before Goshozono appears in the anime industry.

If Gosso and JJK is what not to do with first-time directors, Saitou and Bocchi The Rock is absolutely what to do with them.

Keiichirou Saitou, a person in a similar situation to Gosso, but producing a definitively different result. Just how do they do it?

Before I answer my own question once more, just a brief history of Saitou. They have a total of 7 episode direction credits prior to Bocchi The Rock, and started in the industry back in 2015, also like Gosso.

The massive difference though is where those credits lie and what they are. Cloverworks is a relatively new studio, so rather looking at productions under the same studio, it's more effective to look at staff that overlap with the core of Cloverworks. Most notably this includes the director of Akebi's Sailor Uniform as well as the assistant director for Spy x Family. But more than that is the tenure of these staff members. Being able to work under Shingo Natsume on not one, but two projects is definitely the highlight of Saitou's early work and undoubtedly the source of a great deal of their visual style.

So if Saitou has Nastume, and Gosso has Park, where's the real difference? Well, it's more a subjective opinion, but my belief is the breadth of productions that Saitou has been credited on. Not so much purely in terms of genre and whatnot, but more the number of unique series and how they're spread out. While it's only 2 more episodes directed than Gosso, they've directed on one more series than them, and have their direction credits spread from 2017 into 2021 (5 years total). Meanwhile, Gosso's episode direction credits take place within the span of 2 years.

And that's the very crux of my argument. Saitou has had 3 more years to refine and explore their creative direction under quality staff members. Gosso had less than half the time to do the same thing. And with that inexperience in mind, Gosso leads a larger and more established production with the goal of filling some very big shoes. Bocchi The Rock and Saitou were afforded the benefit of noticeably more freedoms and concessions in regards to production and approach than Gosso and JJK, and that just continues to play into the challenges and successes faced by each.

Gosso and Saitou clearly come from similar backgrounds. Starting their careers around the same time, having a home-base/origin studio in the form of A-1/Madhouse respectively, and have had big breaks early on in their careers. Let me provide a totally different example now.

Mori Hirotaka, arguably the most infamous director of 2023, and the direct rival to Keiichirou Saitou's electric work on Bocchi The Rock. A veritable master of the craft, who presents a different story altogether.

Hirotaka is a far more interesting staff member to take a look at, because they jumped into the industry headfirst with their first credits being assistant episode direction One Piece (for a total of 17 episodes, no less).

From the moment Hirotaka appears in the industry, their focus is on episode direction and storyboarding. Though they originate with Toei, Hirotaka expands their reach to incorporate a trio with the former studio alongside Production I.G and A-1 pictures.

In terms of hard numbers though, they're credited with episode direction for 9 episodes (though one's an opening) across 8 unique series.

I don't think I really need to say it, but I will anyways. Hirotaka is a perfect example of my opinion/argument that time and breadth is the best possible way to encourage growth and exploration of creative foundations and the ability to effectively apply them to various projects. Having those assistant credits just doubles down on the sentiment.

But how about something more interesting? I mentioned Production I.G earlier in the studios that Hirotaka has worked with extensively. Hirotaka started with them in 2014 where they directed the second opening for the first season of Haikyuu!! before moving on to several other projects. Nearly a decade of experience and work under Production I.G. Compare that to Gosso who only has a single Mappa series prior to JJK S2, and Saitou who's a first time Cloverworks staff member.

This is where we tie back in to the freelance work. It took Hirotaka a decade to get the role of a lead director with production I.G, it took Park six years. Saitou got their lead director role with a first-time studio, before they got their lead role with Madhouse. Gosso worked on 3 episodes with Mappa before getting their lead role with them for JJK S2.

Though there's very little time separating these staff members, the idea of a "core" studio remains apparent with Hirotaka and Park, and does not exist with Saitou and Gosso. And it's something you can see happen consistently within this current climate for animation, especially with more "low level" things like key animators.

Let's circle back to get a better look at the bigger picture.

The nature of freelancing in the current industry outlook is to promote swift movement between studios and projects. This means that staff members have more freedom to take on different projects and the like, but at the same time means that without strong industry connections, they lack a foundational team that will provide them with an environment to grow and improve within. This means that we see more and more people placed in key roles where they don't have the keys to success and the ability to effectively manage it.

Great examples of this that are tied back into the comment on new studios appearing is the struggles faced by both Kafka and BUGS FILMS in their initial solo projects. Both are faced with the reality that they don't have experience managing at the scale that they are at, and in their own ways have (and are) struggling to meet expectations. Koichi Naruse is the CEO of Kafka, but has only been in the industry since 2017, and worked on a total of 5 series before moving on to lead Kafka. A similar story can be said of the situation that BUGS FILMS finds themselves in. Not that experience automatically equates to quality and ability, but the more time in industry the better understood it is.

At the end of the day, it's not something easily avoidable. Companies and individuals will struggle, and they will find their place amongst it all.

It's either work under an oppressive schedule in a not-so-great workplace, or job hop. At the end of it, the greats will stay great. Gosso will find their place in it, and Saitou will continue to try and match their initial work. It's just, sort of an aggravating thing to experience as an outsider when the solution is to tone down the number of series produced a year, and unionize all the staff so that they can have livable wages and fair and healthy workplaces.

But either way, here we are. And what does the future hold? Well, like the title says, there's not really anyone that knows for sure. It's one of those things that will only make or break at critical mass. I don't know when that will happen, and I doubt know if others will either. All I know for sure is that the rate of change in the industry continues to grow, and it becomes more and more hungry for high level staff to govern the endless flow of content, despite there not being enough. This gives freelancers much more freedom and opportunity but at the cost of further isolation of members of the industry from environments and workplaces that are meant to help them improve and grow as unique creatives.

#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#mappa#madhouse#呪術廻戦#bocchi the rock#bocchi the rock!#ぼっち・ざ・ろっく!#heavenly delusion#tengoku daimakyou#天国大魔境#anime and manga#anime#anime industry#cloverworks#production i.g#wit studio#studio kafka#e&h production

5 notes

·

View notes