#and how the medieval islamic world was like - so much more advanced than it's western counterpart it's hilarious how ppl mischaracterize it

Text

you know, i can handle a little bit of fun "Nandor is dumb" talk, but i have a net-zero tolerance for any implication that Nandor is not educated.

Nandor would have been incredibly educated in his lifetime.

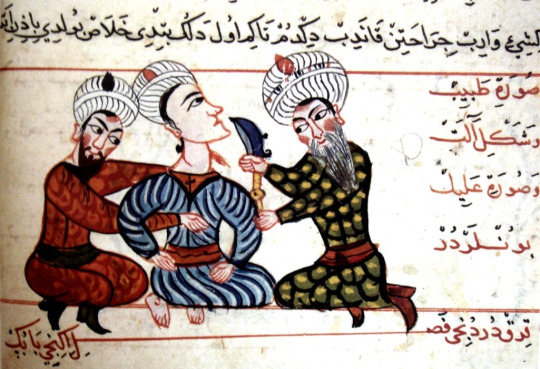

even (or especially) as a soldier in the Islamic World. being a soldier was more like getting sent to boarding school that's also a military camp. they weren't just concerned with creating loyal fodder for war. they were building the next government officials, generals, accountants, advisors, etc. it was important that young men knew how to read, write, speak multiple languages, learn philosophy...sometimes even studying art and music was mandatory.

if he was nobility (and its most likely he was), take all that shit and multiply it exponentially. Nandor would have been reading Plato at the same age most people are still potty training. he would have been specifically groomed in such a way to not be just a brilliant strategist and warrior, but also diplomate and ambassador of literally the center of scientific and cultural excellence of the age.

so like yeah, he can be a big dummy sometimes, sure. but that bitch is probably more educated than any of us will ever be.

#wwdits#nandor the relentless#Nandor#what we do in the shadows#i think its obvious by how much Nandor loves to read that he grew up educated#it's one of my favorite character traits of his#anyways#this was just your local psa abt the depth of Nandor's character and intelligence#and how the medieval islamic world was like - so much more advanced than it's western counterpart it's hilarious how ppl mischaracterize it#(by hilarious i mean it makes me want to break something)#this was in my drafts lolol what did i read that made me vent this? idk#also 'islamic world' is just a term some historians use to describe a specific geographical location and historical age#kind of how 'western world' is used today#it doesn't mean it's specific to one religion or nation but the broader time and location#meaning that Al Qolindar or Persia or Ilkhanate or w/e you want to call where Nandor came from#the same expectations of education and it's vibrant social/cultural world remain an accurate image of the middle east in the medieval age#if you come from the west like me#think The Forum + The Library of Alexandria + Paris/Florence + and idk anything else u think of when u think of 'Western Excellence'#and then imagine of all of that in one place at one time and then u might get close to what the world Nandor was living in as a human

222 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yo, I saw your post about orientalism in relation to the "hollywood middle-east" tiktok!

How can a rando and university dropout get into and learn more about? Any literature or other content to recommend?

Hi!! Wow, you have no idea how you just pressed a button. I'll unleash 5+ years on you. And I'll even add for you open-sourced works that you can access as much as I can!

1. Videos

I often find this is the best medium nowadays to learn anything! I'll share with you some of the best that deal with the topic in different frames

• This is a video of Edward Said talking about his book, Orientalism. Said is the Palestinian- American critic who first introduced the term Orientalism, and is the father of postcolonial studies as a critical literary theory. In this book, you’ll find an in-depth analysis of the concept and a deconstruction of western stereotypes. It’s very simple and he explains everything in a very easy manner.

• How Islam Saved Western Civilization. A more than brilliant lecture by Professor Roy Casagranda. This, in my opinion, is one of the best lectures that gives credit to this great civilization, and takes you on a journey to understand where did it all start from.

• What’s better than a well-researched, general overview Crash Course about Islam by John Green? This is not necessarily on orientalism but for people to know more about the fundamental basis of Islam and its pillars. I love the whole playlist that they have done about the religion, so definitely refer to it if you're looking to understand more about the historical background! Also, I can’t possibly mention this Crash Course series without mentioning ... ↓

• The Medieval Islamicate World. Arguably my favourite CC video of all times. Hank Green gives you a great thorough depiction of the Islamic civilization when it rose. He also discusses the scientific and literary advancements that happened in that age, which most people have no clue about! And honestly, just his excitement while explaining the astrolabe. These two truly enlightened so many people with the videos they've made. Thanks, @sizzlingsandwichperfection-blog

2. Documentaries

• This is an AMAZING documentary called Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Villifies A People by the genius American media critic Jack Shaheen. He literally analysed more than 1000 movies and handpicked some to showcase the terribly false stereotypes in western depiction of Arab/Muslim cultures. It's the best way to go into the subject, because you'll find him analysing works you're familiar with like Aladdin and all sorts.

• Spain’s Islamic Legacy. I cannot let this opportunity go to waste since one of my main scopes is studying feminist Andalusian history. There are literal gems to be known about this period of time, when religious coexistence is documented to have actually existed. This documentary offers a needed break from eurocentric perspectives, a great bird-view of the Islamic civilization in Europe and its remaining legacy (that western history tries so hard to erase).

• When the Moors Ruled in Europe. This is one of the richest documentaries that covers most of the veiled history of Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). Bettany Hughes discusses some of the prominent rulers, the brilliance of architecture in the Arab Muslim world, their originality and contributions to poetry and music, their innovative inventions and scientific development, and lastly, La Reconquista; the eventual fall and erasure of this grand civilization by western rulers.

3. Books

• Rethinking Orientalism by Reina Lewis. Lewis brilliantly breaks the prevailing stereotype of the “Harem”, yk, this stupid thought westerns projected about arab women being shut inside one room, not allowed to go anywhere from it, enslaved and without liberty, just left there for the sexual desires of the male figures, subjugated and silenced. It's a great read because it also takes the account of five different women living in the middle east.

• Nocturnal Poetics by Ferial Ghazoul. A great comparative text to understand the influence and outreach of The Thousand and One Nights. She applies a modern critical methodology to explore this classic literary masterpiece.

• The Question of Palestine by Edward Said. Since it's absolutely relevant, this is a great book if you're looking to understand more about the Palestinian situation and a great way to actually see the perspective of Palestinians themselves, not what we think they think.

• Arab-American Women's Writing and Performance by S.S. Sabry. One of my favourite feminist dealings with the idea of the orient and how western depictions demeaned arab women by objectifying them and degrading them to objects of sexual desire, like Scheherazade's characterization: how she was made into a sensual seducer, but not the literate, brilliantly smart woman of wisdom she was in the eastern retellings. The book also discusses the idea of identity and people who live on the hyphen (between two cultures), which is a very crucial aspect to understand arabs who are born/living in western countries.

• The Story of the Moors in Spain by Stanley Lane-Poole. This is a great book if you're trying to understand the influence of Islamic culture on Europe. It debunks this idea that Muslims are senseless, barbaric people who needed "civilizing" and instead showcases their brilliant civilization that was much advanced than any of Europe in the time Europe was labelled by the Dark Ages. (btw, did you know that arabic was the language of knowledge at that time? Because anyone who was looking to study advanced sciences, maths, philosophy, astronomy etc, had to know arabic because arabic-speaking countries were the center of knowledge and scientific advancements. Insane, right!)

• Convivencia and Medieval Spain. This is a collection of essays that delve further into the idea of “Convivencia”, which is what we call for religious coexistence. There's one essay in particular that's great called Were Women Part of Convivencia? which debunks all false western stereotypical images of women being less in Islamic belief. It also highlights how arab women have always been extremely cultured and literate. (They practiced medicine, studied their desired subjects, were writers of poetry and prose when women in Europe couldn't even keep their surnames when they married.)

4. Novels / Epistolaries

• Granada by Radwa Ashour. This is one of my favourite novels of all time, because Ashour brilliantly showcases Andalusian history and documents the injustices and massacres that happened to Muslims then. It covers the cultural erasure of Granada, and is also a story of human connection and beautiful family dynamics that utterly touches your soul.

• Dreams of Trespass by Fatema Mernissi. This is wonderful short read written in autobiographical form. It deconstructs the idea of the Harem in a postcolonial feminist lens of the French colonization of Morocco.

• Scheherazade Goes West by Mernissi. Mernissi brilliantly showcases the sexualisation of female figures by western depictions. It's very telling, really, and a very important reference to understand how the west often depicts middle-eastern women by boxing them into either the erotic, sensual beings or the oppressed, black-veiled beings. It helps you understand the actual real image of arab women out there (who are not just muslims btw; christian, jew, atheist, etc women do exist, and they do count).

• Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. This is a feminist travel epistolary of a British woman which covers the misconceptions that western people, (specifically male travelers) had recorded and transmitted about the religion, traditions and treatment of women in Constantinople, Turkey. It is also a very insightful sapphic text that explores her own engagement with women there, which debunks the idea that there are no queer people in the middle east.

---------------------

With all of these, you'll get an insight about the real arab / islamic world. Not the one of fanaticism and barbarity that is often mediated, but the actual one that is based on the fundamental essences of peace, love, and acceptance.

#orientalism#literature#arab#middle east#islam#feminism#book recommendations#reference#documentary#western stereotypes#eurocentrism#queer#queer studies#gender studies#women studies#cultural studies#history#christianity#judaism#books#regulusrules asks#regulusrules recs#If you need more recs#or can’t access certain references#feel free to message me and I’ll help you out!

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

I really don’t want to start a discourse™, but I want you to know that I really appreciate how you write joe and Nicky in deo volente. So many of the fics I’ve read have placed yusef in the role of more sexually experienced and less devoted to god, while Nicky is depicted as an inexperienced and virginal priest/knight/monk and so forth and so on. Your narrative of joe out there rescuing people and being faithful, while Nicky looks back on his life of gambling and pleasures of the flesh ...(1/?)

Not to say that there’s anything wrong with either, obviously. I love guilty priest Nicky and repressed Nicky and p much every Nicky. But in the vast array of fics out there, it’s rare to see the opposite. Not that you’re working in a binary morally good/religious vs. not way. Your writing in the fic is really subtle and and your characterizations reveal a lot of depth. I just think it’s cool to see Nicky, average second son of a duke, drinking and gambling and feeling terribly guilty (2/?)

Guilty about the crusades and the fucking horror of crusade 1 without being excessively devout. Just an average dude. Not some paragon of virtue (btw, I’m on chapter 2 of the fic, so I don’t know how much your characterization changes moving forward. You have a lovely ability to combine your incredible knowledge of history, your beautiful writing, and these intimate details of the characters that make them fit— fit the canon and fit the history. (3/? Shit I’m sorry this had gotten way too long)

I enjoy the way you’ve really inserted us into the quotidian aspect of history. Aaaaaanyway— the discourse that I was afraid of: I think that a lot of fans of the movie that are generating fan content (tysfm to all of you beauties, btw 🙏🙏♥️) are westerners (which is a whole nother kettle of fish) and that carries a sort of ignorance about the Muslim world in the Middle Ages and this desire to simplify Europe as “Christian” “fighters for faith” etc. (4/? Fuuuuck. One(??) more)

And when we do that, we end up as characterizing the brown people as “not that”. The thing I love about this fandom is that people are definitely down on the crusades. I feel like all the fic I’ve read has been particularly negative about those wars, but the thing I love about your fic is that you don’t just say war is bad because people died and it was despicable and this pious white dude says so and this one brown person agrees. (5/6, I see the end in sight I swear it)

Instead you give us a larger cast of Muslims and Arabs and really flesh them out and give them opinions and different interpretations of faith, and I really appreciate that. The crusades were terrible, and we know this because these regular dudes who struggle with their different faiths and lives say so. And I just. I think that’s really great. Also, I fucking love yusef’s mom. I feel like more people would be accepting of the gift in this fashion and I think she’s lovely and (god damn it 6/7)

Aaaaaaaand. The bit where yusef returns and she’s already gone breaks my fucking heart. Also the moment where he’s like “I’m not sure about Abraham’s god, but my mothers god is worth my faith”?? Just really fucking great. So. Excellent fic. Excellent characters. Excellent not-being-accidentally-biased-towards-white-Christians. That is what I came here to say. Thank you so much for your amazing stories. I love them and I love history. Sorry about the rambling. idek how I wrote so much. (7/7)

Epilogue: tl;dr: you’re great.

Oh man! What a huge and thoughtful comment (which will in turn provoke a long-ass response from me, so…) I absolutely agree that no matter what fandom, I don’t do Discourse TM; I just sit in my bubble and stay in my lane and do my own thing and create content I enjoy. And I don’t even think this is that so much as just… general commentary on character and background? So obviously all of this should be read as my own personal experience and choices in writing DVLA, and that alone. I really appreciate you for saying that you love a wide range of fan creators/fanworks and you’re not placing one over another, you understand that fans have diverse ranges of backgrounds/experience with history and other cultures when they create content, and that’s not the same for everyone. So I just think that’s a great and respectful way to start things off.

First, as a professional historian who has written a literal PhD thesis on the crusades, I absolutely understand that many people (and regular fans) will not have the same privilege/education/perspective that I do, and that’s fine! They should not be expected to get multiple advanced degrees to enjoy a Netflix movie! But since I DO have that background, and since I’ve been working on the intellectual genealogy of the crusades (and the associated Christian/Muslim component, whether racially or religiously) since I was a master’s student, I have a lot of academic training and personal feelings that inform how I write these characters. Aside from my research on all this, my sister lives in an Islamic country and her boyfriend is a Muslim man; I’ve known a lot of Muslims and Middle Easterners; and especially with the current political climate of Islamophobia and the reckoning with racism whether in reality or fandom, I have been thinking about all this a lot, and my impact on such.

Basically: I love Nicky dearly, but I ADORE Joe, and as such, I’m protective of him and certainly very mindful of how I write him. Especially when the obvious default for westerners in general, fandom-related or otherwise, is to write what you are familiar with (i.e. the European Christian white character) and be either less comfortable or less confident or sometimes less thoughtful about his opposing number. I have at times tangentially stumbled across takes on Joe that turn me into the “eeeeeeeh” emoji or Dubious Chrissy Teigen, but I honestly couldn’t tell you anything else about them because I was like, “nope not for me” and went elsewhere rather than do Discourse (which is pretty much a waste of time everywhere and always makes people feel bad). This is why I’m always selective about my fan content, but especially so with this ship, because I have SO much field-specific knowledge that I just have to make what I like and which suits my personal tastes. So that is what I do.

Obviously, there’s a troublesome history with the trope of “sexually liberate brown person seduces virginal white character into a world of Fleshly Decadence,” whether from the medieval correlation of “sodomite” and “Saracen,” or the nineteenth-century Orientalist depictions of the East as a land variously childishly simplistic, societally backward, darkly mysterious and Exotic, or “decadent” (read: code for sexually unlike Western Europe, including the spectrum of queer acts). So when I was writing DVLA, I absolutely did not want to do that and it’s not to my taste, but I’m not going to whip out a red pen on someone else writing a story that broadly follows those parameters (because as I said, I stay in my lane and don’t see it anyway). Joe to me is just such an intensely complex and lovely Muslim character that that’s the only way I feel like I can honestly write him, and I absolutely love that about him. So yeah, any depiction of hypersexualizing him or making him only available for the sexual use and education of the white character(s) is just... mmm, not for me.

For example, I stressed over whether it was appropriate to move his origin from “somewhere in the Maghreb” to Cairo specifically, since Egypt, while it IS in North Africa, is not technically part of the Maghreb. I realize that Marwan Kenzari’s family is Tunisian and that’s probably why they chose it, to honor the actor’s heritage, but on the flip side… “al-Kaysani” is also a specifically Ismai’li Shia name (it’s the name of a branch of it) and the Fatimids (the ruling dynasty in Jerusalem at the time of the First Crusade) were well-known for being the only Ismai’li Shia caliphate. (This is why the Shi’ites still ancestrally dislike Saladin for overthrowing it in 1174, even if Saladin is a huge hero to the rest of the Islamic world.) Plus I really wanted to use medieval Cairo as Joe’s homeland, and it just made more sense for an Ismai’li Shia Fatimid from Cairo (i.e. the actual Muslim denomination and caliphate that controlled Jerusalem) to be defending the Holy City because it was personal for him, rather than a Sunni Zirid from Ifriqiya just kind of turning up there. Especially due to the intense fragmentation and disorganization in the Islamic world at the time of the First Crusade (which was a big part of the reason it succeeded) and since the Zirids were a breakaway group from the Fatimids and therefore not very likely to be militarily allied with them. As with my personal gripes about Nicky being a priest, I decided to make that change because I felt, as a historian, that it made more sense for the character. But I SUPER recognize it as my own choices and tweaks, and obviously I’m not about to complain at anyone for writing what’s in graphic novel/bonus content canon!

That ties, however, into the fact that Nicky has a clearly defined city/region of origin (Genoa, which has a distinct history, culture, and tradition of crusading) and Joe is just said to be from “the Maghreb” which…. is obviously huge. (I.e. anywhere in North Africa west of Egypt all the way to Morocco.) And this isn’t a fandom thing, but from the official creators/writers of the comics and the movie. And I’m over here like: okay, which country? Which city? Which denomination of Islam? You’ve given him a Shia name but then point him to an origin in Sunni Ifriqiya. If he’s from there, why has he gone thousands of miles to Jerusalem in the middle of a dangerous war to help his religious/political rivals defend their territory? Just because he’s nice? Because it was an accident? Why is his motivation or reason for being there any less defined or any less religious (inasmuch as DVLA Nicky’s motive for being on the First Crusade is religious at all, which is not very) than the white character’s? In a sense, the Christians are the ones who have to work a lot harder to justify their presence in the Middle East in the eleventh century at all: the First Crusade was a specifically military and offensive invasion launched at the direct behest of the leader of the Western Roman church (Pope Urban II.) So the idea that they’re “fighting for the faith” or defending it bravely is…

Eeeeh. (Insert Dubious Chrissy Teigen.)

But of course, nobody teaches medieval history to anyone in America (except for Bad Game of Thrones History Tee Em), and they sure as hell don’t teach about the crusades (except for the Religious Violence Bad highlight reel) so people don’t KNOW about these things, and I wish they DID know, and that’s why I’m over here trying to be an academic so I can help them LEARN it, and I get very passionate about it. So once again, I entirely don’t blame people who have acquired this distorted cultural impression of the crusades and don’t want to do a book’s worth of research to write a fic about a Netflix movie. I do hope that they take the initiative to learn more about it because they’re interested and want to know more, since by nature the pairing involves a lot of complex religious, racial, and cultural dynamics that need to be handled thoughtfully, even if you don’t know everything about it. So like, basically all I want is for the Muslim character(s) to be given the same level of respect, attention to detail, background story, family context, and religious diversity as any of the white characters, and Imma do it myself if I have to. Dammit.

(I’m really excited to hear your thoughts on the second half of the fic, especially chapter 3 and chapter 6, but definitely all of it, since I think the characters they’re established as in the early part of the fic do remain true to themselves and both grow and struggle and go through a realistic journey with their faith over their very long lives, and it’s one of my favorite themes about DVLA.)

Anyway, about Nicky. I also made the specific choice to have him be an average guy, the ordinary second son of a nobleman who doesn’t really know what he’s doing with his life and isn’t the mouthpiece of Moral Virtue in the story, since as he himself realizes pretty quick, the crusades and especially the sack/massacre of Jerusalem are actually horrific. I’ve written in various posts about my nitpicking gripes with him being a priest, so he’s not, and as I said, I’m definitely avoiding any scenario where he has to Learn About The World from Joe. That is because I want to make the point that the people on the crusades were people, and they went for a lot of different reasons, not all of which were intense personal religious belief. The crusades were an institution and operated institutionally. Even on the First Crusade, where there were a lot of ordinary people who went because of sincere religious belief, there was the usual bad behavior by soldiers and secular noblemen and people who just went because it was the thing to do. James Brundage has an article about prostitution and miscegenation and other sexual activity on the First Crusade; even at the height of this first and holy expedition, it was happening. So Nicky obviously isn’t going to be the moral exemplar because a) the crusades are horrific, he himself realizes that, and b) it’s just as historically accurate that he wouldn’t be anyway. Since the idea is that medieval crusaders were all just zealots and ergo Not Like Us is dangerous, I didn’t want to do that either. If we think they all went because they were all personally fervent Catholics and thus clearly we couldn’t do the same, then we miss a lot of our own behavior and our parallel (and troubling) decisions, and yeah.

As well, I made a deliberate choice to have Nicky’s kindness (which I LOVE about him, it’s one of my favorite things, god how refreshing to have that be one of the central tenets of a male warrior character) not to be something that was just… always there and he was Meek and Good because a priest or whatever else. Especially as I’ve gotten older and we’ve all been living through these ridiculous hellyears (2020 is the worst, but it’s all been general shit for a while), I’ve thought more and more about how kindness is an active CHOICE and it’s as transgressive as anything else you can do and a whole lot more brave than just cynicism and nihilism and despair. As you’ll see in the second half of the fic, Nicky (and Joe) have been through some truly devastating things and it might be understandable if they gave into despair, but they DON’T. They choose to continue to be good people and to try and to actively BE kind, rather than it being some passive default setting. They struggle with it and it’s raw and painful and they’re not always saints, but they always come down on the side of wanting to keep doing what they’re doing, and I… have feelings about that.

Anyway, this is already SUPER long, so I’ll call it quits for now. But thank you so much for this, because I love these characters and I love the story I created for them in DVLA, since all this is personal to me in a lot of ways, and I’m so glad you picked up on that.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Columbus: Master Double Agent and Portugal’s 007

Henry IV of Spain – known as "The Impotent" for his weakness, both on the throne and (allegedly) in the marriage chamber – died in 1474. A long and inconclusive war of succession ensued, pitting supporters of Henry's 13-year-old heir, Juana de Trastámara, against a faction led by Princess Isabel of Castile and her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon. Portugal, Spain's much smaller antagonist for centuries already, sided with the loyalists.

(Wedding portrait of King Ferdinand II of Aragón and Queen Isabella of Castile.)

The civil war ended in 1480, with the Treaty of Alcáçovas/Toledo, whereby Portugal withdrew support for Juana; in exchange, Isabel and Fernando promised not to encroach on South Atlantic trade routes that Portugal had long been exploring and wished to monopolize.

Treaty Not Worth Much

Spain immediately began to violate the Treaty of Alcáçovas. Portugal's gold trade with Ghana was a powerful enticement, but the Spanish were also lured by the priceless knowledge that Portugal had painstakingly gathered about the currents, territories, winds and heavenly bodies relative to the Atlantic regions. The Portuguese were far advanced in the sciences of geography and navigation pertaining to the Atlantic Ocean, both south and west of Portugal itself.

Meanwhile, João II ascended to the throne of Portugal in 1481, reversing the policies of his father, another weak, late-Medieval ruler who'd surrendered excessive estates and privileges to the nobility. Large swaths of the noble class rebelled, but João II was an astute diplomat, with powerful alliances among the military and religious orders across Europe, along with an extensive network of spies. He sprang a trap on his adversaries, capturing and executing the ring leader.

(João II of Portugal)

Conspiracy!

Queen Isabel supported the traitors in Portugal, having obtained their promise to annul the Treaty of Alcáçovas. When the conspiracy was exposed, numerous traitors among the Portuguese nobility fled to Spain, where they found asylum, along with a base from which to continue their hostilities against João II. Prominent among the defectors were two nephews of the highly-born wife of Christopher Columbus – who would himself sacrifice the next twenty years of his life to join this exodus, faking desertion to his sovereign's most bitter foe. The internecine strife was so keen that after another occasion when his agents had tipped him off, which resulted in João II personally executing the Duke of Viseu, he threatened to charge his own wife with treason for weeping over her brother.

(Christopher Columbus was arrested at Santo Domingo in 1500 by Francisco de Bobadilla and returned to Spain, along with his two brothers, in chains)

The Mother of All Secrets

It's now been amply proven that evidence of hostility between Columbus and João II was fabricated. Columbus was, in fact, a member of João II's inner circle, in addition to being one of the most seasoned of all Portuguese mariners. After his false defection to Spain, Columbus attended three secret meetings with João II, the second of these, in 1488, being prompted by the mother of all maritime secrets: Dias having rounded the Cape of Good Hope, thereby establishing the shortest route to India by sea.

Now, the Holy Grail of all commercial bonanzas was a sea route to the riches of India – sought because Christendom was at war with Islam, and Muslim armies blocked the much shorter land routes across the Middle East. What the most knowledgeable Portuguese pilots knew was top secret, state of the art, a scientific prize for international espionage.

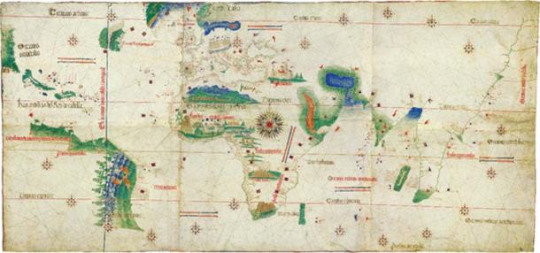

(The Portuguese discovered numerous territories and routes during the 15th and 16th centuries. Cantino planisphere, made by an anonymous cartographer in 1502.)

The Portuguese had been the first Europeans to launch expeditions in search of the Equator, which they reached around 1470, discovering while they were at it, the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. By 1485, expert Portuguese technicians had invented charts and tables – based on the height of the sun at the Equator – which allowed navigators to determine their location in the daytime. While King João II was keeping Columbus up to date with all of the cutting-edge developments in maritime science, he was at the same time spreading so much disinformation elsewhere—among friends and foes alike— that we are still unraveling it.

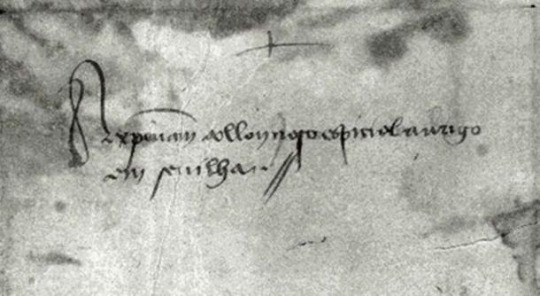

(This secret letter, written by King João II was found in Columbus’ archives. Here is the exterior, addressed in the hand of King João II to, “Xpovam Collon, our special friend in Seville.”)

João II’s agents spent years pursuing the most important traitors across Spain, France and England. With that in view, the following comparison is revealing. Both Columbus and his nephew Don Lopo de Albuquerque (Count of Penamacor) fled Portugal at the same time, took refuge at Isabel's court under false identities, and fostered invasions of the Portuguese Atlantic monopoly from foreign shores. Lopo was tenaciously pursued, finally cornered in Seville and assassinated; in contrast, Columbus disposed of Portuguese secrets, exchanged letters covertly with King João II throughout his eight-year residence in Spain, stopped in Portugal on three of his four voyages, and lied to the Spanish Monarchs about these secret contacts.

A Secret Identity

Christopher Columbus is the garbled pseudonym of a very wellborn, learned, seafaring Portuguese nobleman. The antidote to all subsequent confusion about this man's true identity and character is simply to recognize that the news of his "discovery," which broke like a thunderbolt across the rest of Europe, was in fact nothing more than the release of information that the Portuguese had been hoarding for decades, laced with a linguistic insinuation that Spain had just pioneered the shortest route to India.

Everything Falls into Place

This new perspective on Columbus – as a Portuguese double agent – results in a major paradigm shift. All of the lies perpetrated by Columbus, his family, and the royal chroniclers suddenly begin to make sense as elements in a single, grand design, whose architect was King João II.

It is remarkable that the wave of treasons occurring in Portugal during the mid-1480s – engaging both Queen Isabel and Columbus so deeply – has never been linked by Portuguese historians to the biography of Columbus. Yet, no serious historian today accepts that Columbus was the first European to reach the Americas. There is no excuse any longer for maintaining that he was, or for sustaining the obsolete, pseudo-historical pretense that Columbus invented the idea of sailing west or that he ever really believed he'd landed in India.

(The secret Memorial Portugués, advising Queen Isabel that Portugal engineered the Treaty of Tordesillas specifically to safeguard the best territories for herself. Note how King João II is called (A) “an evil devil,” malvado diablo , and (B) how the “Indies,” Indias”, that Columbus visited are described as NOT the real India)

Having skirted the western lands from Canada to Argentina, the Portuguese understood there were no established commercial ports, no ready-made commercial goods, and was thus no trade potential there to compare with that of India. Columbus – and his many other co-conspirators in Spain, easily identified in retrospect – guarded these secrets faithfully, secrets they had to be privy to if they would guide the Spanish Monarchs to the counterfeit of India. The trade for gold and other goods along the west coast of Africa was immensely profitable, but still more jealously guarded was knowledge that the sea route to India lay also in this direction. The Portuguese were intent on keeping Spanish ships out of these waters. With both war and treaties having failed, João II and Columbus launched an audacious ruse to obtain their objective through less obvious means.

How History is Shaped

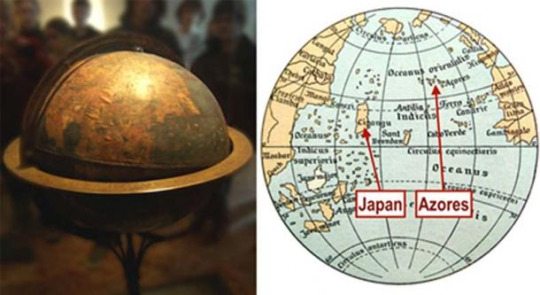

Colossal planning, nerve, and effort went into this accomplishment – seven years of convincing knowledgeable skeptics that the voyage was possible, outfitting a fleet and loading it with merchandise for trade (including cinnamon that would later be presented as evidence of contact with India). On a secret mission to Germany, Martim Behaim, another Templar knight member of the Portuguese Order of Christ, built a false globe based on Toscanelli's theory that East Asia lay just across the Atlantic. This globe still exists; it is the oldest one in the world. Genuine Portuguese traitors warned the Spanish Monarchs that they were being deceived.

(Martin Behaim’s globe intentionally placed the Azores islands, where Behaim lived and was married, on top of the Americas. This made Asia appear much closer to Europe than it really is, thus supporting the project that Columbus was advocating for: Map of Atlantic Ocean)

The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), observed fairly well by both sides, achieved João II's strategic objective: to engage the Spanish in the west while keeping them out of those regions that Portugal wished to dominate. Its effect on the linguistic, racial and cultural substance of an immense portion of the globe has scarcely been rivaled by any other treaty between two nations. No single factor did more to realize this outcome than the erudite seamanship, cunning, ruthless persistence, loyalty and sangfroid of the man whom we still remember today as "Christopher Columbus," a real-life 007, on May 20th, 1506.

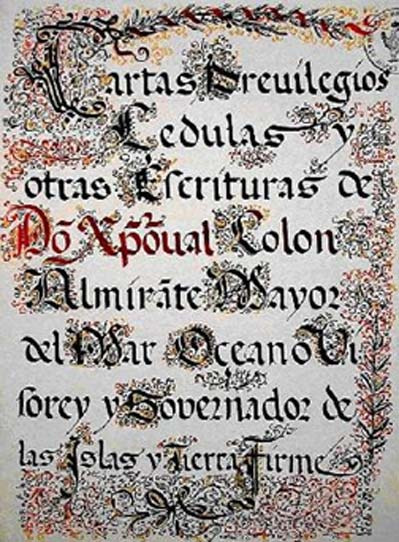

(Cover from the master spy and sailor's Book of Privileges , which clearly shows that the owner's pseudonym was "Colon." An international transmission of the stunning "discovery," in March of 1493, distorted the name in such a fashion as to leave us with "Columbus" in English today. Technically speaking, "Colón" as the Spanish still call him, is correct, and it will someday most likely replace "Columbus" in common usage)

Another particularly factor that King João II knew of existence of land on the west was that when the first Treaty of Tordesilhas came, the line that separate Spain and Portugal territory was just near the Cape Verde territory (already belonging to Portugal). King João II refuse that line and asked for more 370 nautical miles west from that line. The Spanish Monarchs, not knowing anything about the globe, accepted, thinking that it was just more water. When the new Treaty came, the line that King João II asked put Brasil over Portuguese domain. How King João II knew exactly the number of miles to put Brasil in Portugal territory? Because he already knew there was land on the west. The “discovery” of Brasil was NOT an accident.

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

What are the key drivers of economic prosperity? Why do societies that were at one point world economic leaders often end up falling behind? What role do factor markets play in this process? These are the questions addressed in Bas van Bavel’s fascinating entry into the “big think” literature, The Invisible Hand? How Market Economies Have Emerged and Declined since AD 500. In this book, van Bavel proposes a theory of cyclical economic growth and decline, and he supports this theory with three case studies: early medieval Iraq (c. 500-1100), high medieval northern Italy (c. 1000-1500), and the late medieval and early modern Low Countries (c. 1100-1800).

Van Bavel’s framework can be conceptualized as an economics counterpart to Ibn Khaldun’s political cyclical theory of empires. The (somewhat neo-Marxian) argument suggests that economic decline is a natural consequence of the type of economic growth that happens via factor markets. In other words, the growth of factor markets is a self-undermining process. This is a fairly significant departure from conventional economic history accounts, which largely view the development of market economies as more of a linear process.

Van Bavel’s argument can be summarized as follows. In societies with some sufficiently high level of personal and economic freedom as well as some degree of prosperity (due to non-market mechanisms of exchange for land, labor, and capital) factor markets are likely to emerge. In the process, a positive feedback loop occurs in which underutilized resources are more productively used, specialization and division of labor arise, economic growth results, which results in greater use of factor markets, and so on. However, with factor market growth comes inequality — both economic and political. As those who own the factors of production gain more political power, they use this power to dominate the markets for land, labor, and capital, as well as financial markets, making these markets less free in the process. This precipitates the economic decline of the society, as vested interests squeeze the little remaining productive power out of the economy, leaving little for the rest of society. The decline that van Bavel proposes is therefore endogenous to the very processes that contributed to the rise in the first place.

Perhaps the most ambitious aspect of The Invisible Hand? is the cases to which van Bavel applies the theory: early Islamic Iraq, Commercial Revolution Italy, and the late medieval and early modern Low Countries. These are not randomly plucked cases: one could make the case that they represent the world’s (or, at a minimum, western Eurasia’s) economic frontier from about 750 to 1700. Van Bavel must be commended for picking these three cases: few scholars have the breadth of knowledge to dig so deeply into three such vastly disparate cases. And indeed, the cases work quite well for the theory. Iraq of the Abbasid period was probably the wealthiest and most advanced region of the world. Indeed, in 800 the population of Baghdad was greater than the top thirteen Christian cities of Western Europe combined! Yet, it clearly started to fall behind at some point well before the Mongol invasion crushed what remained of the Abbasid Empire in 1258. Van Bavel convincingly points to the rise and decline of factor markets as a culprit. Although the evidence is scanter than it is for the others cases, van Bavel makes a strong case that the development of markets in labor, capital, finance, and especially land (and land lease) played an important role in the region’s growth, while the accumulation of these factors of production in a small number of hands ended up stifling growth and, ultimately, the very markets that spurred growth in the first place. Indeed, van Bavel presents data indicating that the Gini coefficient on wealth inequality in tenth century Iraq was a startling 0.99, making it one of the most unequal societies in world history.

Similar evidence is provided for the cases of northern Italy during and after the Commercial Revolution and the Low Countries in the late medieval and early modern periods. For these cases, the data and secondary sources are much more complete and the narratives are quite compelling. Indeed, one might suspect that the Low Countries case that van Bavel has researched so deeply was the motivating example behind the book (and it is indeed a good example). In both of these cases, societies that were wealthier than their neighbors — but not by much — saw a growth in factor and financial markets, with the resulting proceeds initially being relatively widely distributed. Over time, it was precisely access to these factor and financial markets that enabled the accumulation of wealth in a small amount of hands. This gave the economic elites access to political power and the capacity to buy up most of the rural hinterlands, which ultimately led to the (relative) decline of factor markets and, more generally, these economies. Seen from this perspective, the cultural achievements of the Renaissance or the Dutch Golden Age — funded as they were by the ultra-wealthy — were a symptom of decline, not vibrancy.

As one is reading the book, it is natural to think, “an economic rise followed by the accumulation of factors of production in a small amount of hands sounds a lot like the modern day U.S.” While historians are often hesitant to make such conjectures on more recent events, van Bavel provides a quite welcome chapter overviewing (in only slightly less depth) the trajectories of the UK and U.S. since the eighteenth century. Not surprisingly, he argues that both are reflective of the cyclical theory of economic development propounded throughout the book. These are important insights, as they suggest that modern day inequality may be a structural feature of the American and British economic rise.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle for the Soul of Islam

By James M. Dorsey

This story was first published in Horizons

TROUBLE is brewing in the backyard of Muslim-majority states competing for religious soft power and leadership of the Muslim world in what amounts to a battle for the soul of Islam. Shifting youth attitudes towards religion and religiosity threaten to undermine the rival efforts of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran and, to a lesser degree, the United Arab Emirates, to cement their individual state-controlled interpretations of Islam as the Muslim world’s dominant religious narrative. Each of the rivals see their efforts as key to securing their autocratic or authoritarian rule as well as advancing their endeavors to carve out a place for themselves in a new world order in which power is being rebalanced.

Research and opinion polls consistently show that the gap between the religious aspirations of youth—and, in the case of Iran other age groups—and state-imposed interpretations of Islam is widening. The shifting attitudes amount to a rejection of Ash’arism, the fundament of centuries-long religiously legitimized authoritarian rule in the Sunni Muslim world that stresses the role of scriptural and clerical authority. Mustafa Akyol, a prominent Turkish Muslim intellectual, argues that Ash’arism has dominated Muslim politics for centuries at the expense of more liberal strands of the faith “not because of its merits, but because of the support of the states that ruled the medieval Muslim world.”

Similarly, Nadia Oweidat, a student of the history of Islamic thought, notes that “no topic has impacted the region more profoundly than religion. It has changed the geography of the region, it has changed its language, it has changed its culture. It has been shaping the region for thousands of years. [...] Religion controls every aspect of people who live in the Arab world.”

The polls and research suggest that youth are increasingly skeptical towards religious and worldly authority. They aspire to more individual, more spiritual experiences of religion. Their search leads them in multiple directions that range from changes in personal religious behavior that deviates from that proscribed by the state to conversions in secret to other religions even though apostasy is banned and punishable by death, to an abandonment of organized religion all together in favor of deism, agnosticism, or atheism.

“The youth are not interested in institutions or organizations. These do not attract them or give them any incentive; just the opposite, these institutions and organizations and their leadership take advantage of them only when they are needed for their attendance and for filling out the crowds,” said Palestinian scholar and former Hamas education minister Nasser al-Din al-Shaer.

Atheists and converts cite perceived discriminatory provisions in Islam’s legal code towards various Muslim sects, non-Muslims, and women as a reason for turning their back on the faith. “The primary thing that led me to atheism is Islam’s moral aspect. How can, for example, a merciful and compassionate God, said to be more merciful than a woman on her baby, permit slavery and the trade of slaves in slave markets? How come He permits rape of women simply because they are war prisoners? These acts would not be committed by a merciful human being much less by a merciful God,” said Hicham Nostic, a Moroccan atheist, writing under a pen name.

Revival, Reversal

The recent research and polls suggest a reversal of an Islamic revival that scholars like John Esposito in the 1990s and Jean-Paul Carvalho in 2009 observed that was bolstered by the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, the results of a 1996 World Values Survey that reported a strengthening of traditional religious values in the Muslim world, the rise of Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and the initial Muslim Brotherhood electoral victories in Egypt and Tunisia in the wake of the 2011 popular Arab revolts.

“The indices of Islamic reawakening in personal life are many: increased attention to religious observances (mosque attendance, prayer, fasting), proliferation of religious programming and publications, more emphasis on Islamic dress and values, the revitalization of Sufism (mysticism). This broader-based renewal has also been accompanied by Islam’s reassertion in public life: an increase in Islamically oriented governments, organizations, laws, banks, social welfare services, and educational institutions,” Esposito noted at the time.

Carvalho argued that an economic “growth reversal which raised aspirations and led subsequently to a decline in social mobility which left aspirations unfulfilled among the educated middle class (and) increasing income inequality and impoverishment of the lower-middle class” was driving the revival. The same factors currently fuel a shift away from traditional, Orthodox, and ultra-conservative values and norms of religiosity.

The shift in Muslim-majority countries also contrasts starkly with a trend towards greater religious Orthodoxy in some Muslim minority communities in Europe. A 2018 report by the Dutch government’s Social and Cultural Planning Bureau noted that the number of Muslims of Turkish and Moroccan descent who strictly observe traditional religious precepts had increased by approximately eight percent. Dutch citizens of Turkish and Moroccan descent account for two-thirds of the country’s Muslim community. The report suggested that in a pluralistic society in which Muslims are a minority, “the more personal, individualistic search for true Islam can lead to youth becoming more strict in observance than their parents or environment ever were.”

Changing attitudes towards religion and religiosity that mirror shifting attitudes in non-Muslim countries are particularly risky for leaders, irrespective of their politics, who cloak themselves in the mantle of religion as well as nationalism and seek to leverage that in their geopolitical pursuit of religious soft power. The 2011 popular Arab revolts as well as mass anti-government protests in various Middle Eastern countries in 2019 and 2020 spotlighted the subversiveness of the change. “The Arab Spring was the tipping point in the shift [...]. It was the epitome of how we see the change. The calls were for ‘dawla madiniya,’ a civic state. A civic state is as close as you can come to saying [...], we want a state where the laws are written by people so that we can challenge them, we can change them, we can adjust them. It’s not God’s law, it’s madiniya, it’s people’s law,” Oweidat, the Islamic thought scholar, said.

Akyol went further, noting in a journal article that “too many terrible things have recently happened in the Arab world in the name of Islam. These include the sectarian civil wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, where most of the belligerents have fought in the name of God, often with appalling brutality. The millions of victims and bystanders of these wars have experienced shock and disillusionment with religious politics, and more than a few began asking deeper questions.”

The 2011 popular Arab revolts reverberated across the Middle East, reshaping relations between states as well as domestic policies, even though initial achievements of the protesters were rolled back in Egypt and sparked wars in Libya, Yemen, and Syria.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt imposed a 3.5 year-long diplomatic and economic boycott of Qatar in part to cut their youth off from access to the Gulf state’s popular Al Jazeera television network that supported the revolts and Islamist groups that challenged the region’s autocratic rulers. Seeking to lead and tightly control a social and economic reform agenda driven by youth who were enamored by the uprisings, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman “sought to recapture this mandate of change, wrap it in a national mantle, and sever it from its Arab Spring associations. The boycott and ensuing nationalist campaign against Qatar became central to achieving that,” said Gulf scholar Kristin Smith Diwan.

Referring to the revolts, Moroccan journalist Ahmed Benchemsi suggested that “the Arab Spring may have stalled, if not receded, but when it comes to religious beliefs and attitudes, a generational dynamic is at play. Large numbers of individuals are tilting away from the rote religiosity Westerners reflexively associate with the Arab world.”

Benchemsi went on to argue that “in today’s Arab world, it’s not religiosity that is mandatory; it’s the appearance of it. Nonreligious attitudes and beliefs are tolerated as long as they’re not conspicuous. As a system, social hypocrisy provides breathing room to secular lifestyles, while preserving the façade of religion. Atheism, per se, is not the problem. Claiming it out loud is. So those who publicize their atheism in the Arab world are fighting less for freedom of conscience than for freedom of speech.” The same could be said for the right to convert or opt for alternative practices of Islam.

Syrian journalist Sham al-Ali recounts the story of a female relative who escaped the civil war to Germany where she decided to remove her hijab. Her father, who lives in Turkey, accepted his daughter’s decision but threatened to disown her if she posted pictures of herself uncovered on Facebook. “His issue was not with his daughter’s abandonment of religious duty, but with her publicizing that before her family and society at large,” Al-Ali said.

Neo-patriarchism

Neo-patriarchism, a pillar of Arab autocratic rule, heightens concern about public appearance and perception. A phrase coined by American-Palestinian scholar Hisham Sharabi, neo-patriarchism involves projection of the autocratic leader as a father figure. Autocratic Arab society, according to Sharabi, was built on the dominance of the father, a patriarch around which the national as well as the nuclear family are organized. Relations between a ruler and the ruled are replicated in the relationship between a father and his children. In both settings, the paternal will is absolute, mediated in society as well as the family by a forced consensus based on ritual and coercion.

As a result, neo-patriarchism often reinforces pressure to abide by state-imposed religious behavior and at the same time fuels changes in attitudes towards religion and religiosity among youth who resent their inability to chart a path of their own. Primary and secondary schools have emerged as one frontline in the struggle to determine the boundaries of religious expression and behavior. Recent developments in Egypt, a brutal autocracy, and Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority democracy, offer contrasting perspectives on how the tug of war between students and parents, schoolteachers and administrations, and the state plays out.

Mada Masr, Egypt’s foremost independent news outlet, documented how in 2020 Egyptian schoolgirls who refused to wear a hijab were being coerced and publicly shamed in the knowledge that the education ministry was reluctant to enforce its policy not to mandate the wearing of a headdress. “The model, decent girl is expected to dress modestly and wear a hijab to signal her pride in her religious identity, since hijab is what distinguishes her from a Christian girl,” said Lamia Lotfy, a gender consultant and rights activist. Teachers at public high schools said they were reluctant to take boys to task for violating dress codes because they were more likely to push back and create problems.

In sharp contrast, Indonesian Religious Affairs Minister Yaqut Cholil Qoumas issued in early 2021 a decree together with the ministers of home affairs and education threatening to sanction state schools that seek to impose religious garb in violation of government rules and regulations. The decree was issued amid a public row sparked by the refusal of a Christian student to obey her school principal’s instructions requiring all pupils to wear Islamic clothing. Qoumas is a leader of Nahdlatul Ulama, the world’s largest Muslim movement and foremost advocate of theological reform in line with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “Religions do not promote conflict, neither do they justify acting unfairly against those who are different,” Qoumas said.

A Muslim nation that replaced a decades long autocratic regime with a democracy in a popular revolt in 1998, Indonesia is Middle Eastern rulers’ worst nightmare. The shifting attitudes of Middle Eastern youth towards religion and religiosity suggest that experimentation with religion in post-revolt Indonesia is a path that it would embark on if given the opportunity. Indonesia is “where the removal of constraints imposed by an authoritarian regime has opened up the imaginative terrain, allowing particular types of religious beliefs and practices to emerge [...]. The Indonesian cases study [...] brings into sharper relief processes that are happening in ordinary Muslim life elsewhere,” said Indonesia scholar Nur Amali Ibrahim.

A 2019 poll of Arab youth showed that two-thirds of those surveyed felt that religion played too large a role in their lives, up from 50 percent four years earlier. Nearly 80 percent argued that religious institutions needed to be reformed while half said that religious values were holding the Arab world back. Surveys conducted over the last decade by Arab Barometer, a research network at Princeton University and the University of Michigan, showed a growing number of youths turning their backs on religion. “Personal piety has declined some 43 percent over the past decade, indicating less than a quarter of the population now define themselves as religious,” the survey concluded.

With the trend being the strongest among Libyans, many Libyan youth gravitate towards secretive atheist Facebook pages. They often are products of the UAE’s failed attempt to align the hard power of its military intervention in Libya with religious soft power. Said, a 25-year-old student from Benghazi, the stronghold of the UAE and Saudi-backed rebel forces led by self-appointed Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, turned his back on religion after his cousin was beheaded in 2016 for speaking out against militants. UAE backing of Haftar has involved the population of his army by Madkhalists, a branch of Salafism named after a Saudi scholar who preaches absolute obedience to the ruler and projects the kingdom as a model of Islamic governance. “My cousin’s death occurred during a period when I was deeply religious, praying five times a day and studying ten new pages of the Qur’an each evening,” Said said.

A majority of respondents in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, and Iran said in a 2017 poll conducted by Washington-based John Zogby Associates that they wanted religious movements to focus on personal faith and spiritual guidance and not involve themselves in politics. Iraq and Palestine were the outliers with a majority favoring a political role for religious groups.

The response to polls in the second half of the second decade of the twenty-first century contrasts starkly with attitudes expressed in a survey of the world’s Muslims by the Pew Research Center several years earlier. Pew’s polling suggested that ultra-conservative attitudes long promoted by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar that legitimized authoritarian and autocratic regimes remained popular. More than 70 percent of those surveyed at the time in South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa favored making Sharia the law of the land and granting Sharia courts jurisdiction over family law and property disputes.

Those numbers varied broadly, however, when respondents were asked about specific issues like apostasy and corporal punishment. Three-quarters of South Asians favored the death sentence for apostasy as opposed to 56 percent in the Middle East and only 27 percent in Southeast Asia, while 81 percent in South Asia supported physical punishment compared to 57 percent in the Middle East and North Africa and 46 percent in Southeast Asia. South Asia emerged as the only part of the Muslim world in which respondents preferred a strong leader to democracy while a majority of the faithful in all three regions viewed religious freedom as positive. Between 65 and 79 percent in all regions wanted to see religious leaders have political influence.

Honor killings may be the one area where attitudes have not changed that much in recent years. Arab Barometer’s polling in 2018 and 2019 showed that more people thought honor killings were acceptable than homosexuality. In most countries polled, young Arabs appeared more likely than their parents to condone honor killings. Social media and occasional protests bear that out. Thousands rallied in early 2020 in Hebron, a conservative city on the West Bank, after the Palestinian Authority signed the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Nonetheless, the assertions by Saudi Arabia that projects itself as the leader of an unidentified form of moderate Islam that preaches absolute obedience to the ruler and by advocates of varying strands of political Islam such as Turkey and Iran ring hollow in light of the dramatic shift in attitudes towards religion and religiosity.

Acknowledging Change

Among the Middle Eastern rivals for religious soft power, the United Arab Emirates, populated in majority by non-nationals, may be the only one to emerge with a cleaner slate. The UAE is the only contender to have started acknowledging changing attitudes and demographic realities. Authorities in November 2020 lifted the ban on consumption of alcohol and cohabitation among unmarried couples. In a further effort to reach out to youth, the UAE organized in 2021 a virtual consultation with 3,000 students aimed at motivating them to think innovatively over the country’s path in the next 50 years.

Such moves do not fundamentally eliminate the risk that the changing attitudes may undercut the religious soft power efforts of the UAE and its Middle Eastern competitors. The problem for rulers like the UAE and Saudi crown princes, Mohammed bin Zayed and Mohammed bin Salman, respectively, is that the loosening of social restrictions in Saudi Arabia—including the emasculation of the kingdom’s religious police, the lifting of a ban on women’s driving, less strict implementation of gender segregation, the introduction of Western-style entertainment and greater professional opportunities for women, and a degree of genuine religious tolerance and pluralism in the UAE—are only first steps in responding to youth aspirations.

“People are sick and tired of organized religion and being told what to do. That is true for all Gulf states and the rest of the Arab world,” quipped a Saudi businessman. Social scientist Ellen van de Bovenkamp describes Moroccans she interviewed for her PhD thesis as living “a personalized, self-made religiosity, in which ethics and politics are more important than rituals.”

Nevertheless, religious authorities in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, Qatar, Iran, and Morocco continue to project interpretations of the faith that serve the state and are often framed in the language of tolerance and inter-faith dialogue but preserve outmoded legal categories, traditions, and scripture that date back centuries. Outdated concepts of slavery, who is a believer and who is an infidel, apostasy, blasphemy, and physical punishment that need reconceptualization remain in terms of religious law frozen in time. Many of those concepts, with the exception of slavery that has been banned in national law yet remains part of Islamic law, have been embedded in national legislations.

While Turkey continues to, at least nominally, adhere to its secular republican origins, it is no different from its rivals when it comes to grooming state-aligned clergymen, whose ability to think out of the box and develop new interpretations of the faith is impeded by a religious education system that stymies critical thinking and creativity. Instead, it too emphasizes the study of Arabic and memorization of the Qur’an and other religious texts and creates a religious and political establishment that discourages, if not penalizes, innovation.

Widening the gap between state projections of religion and popular aspirations is the fact that governments’ subjugation of religious establishments turns clerics and scholars into regime parrots and fuels youth skepticism towards religious institutions and leaders.

“Youth have [...] witnessed how religious figures, who still remain influential in many Arab societies, can sometimes give in to change even if they have resisted it initially. This not only feeds into Arab youth’s skepticism towards religious institutions but also further highlights the inconsistency of the religious discourse and its inability to provide timely explanations or justifications to the changing reality of today,” said Gulf scholar Eman Alhussein in a commentary on the 2020 Arab Youth Survey.

Pooyan Tamimi Arab, the co-organizer of an online survey in 2020 of Iranian attitudes towards religion that revealed a stunning rejection of state-imposed adherence to conservative religious mores as well as the role of religion in public life noted the widening gap “becomes an existential question. The state wants you to be something that you don’t want to be [...]. “Political disappointment steadily turned into religious disappointment [...]. Iranians have turned away from institutional religion on an unprecedented scale.”

In a similar vein, Turkish art historian Nese Yildiran recently warned that a fatwa issued by President Erdogan’s Directorate of Religious Affairs or Diyanet declaring popular talismans to ward off “the evil eye” as forbidden by Islam fueled criticism of one of the best-funded branches of government. The fatwa followed the issuance of similar religious opinions banning the dying of men’s moustaches and beards, feeding dogs at home, tattoos, and playing the national lottery as well as statements that were perceived to condone or belittle child abuse and violence against women.

Although compatible with a trend across the Middle East, the Iranian survey’s results, which is based on 50,000 respondents who overwhelmingly said they resided in the Islamic republic, suggested that Iranians were in the frontlines of the region’s quest for religious change.

Funded by Washington-based Iranian human rights activist Ladan Boroumand, the Iranian survey, coupled with other research and opinion polls across the Middle East and North Africa, suggests that not only Muslim youth, but also other age groups, who are increasingly skeptical towards religious and worldly authority, aspire to more individual, more spiritual experiences of religion.

Their quest runs the gamut from changes in personal religious behavior to conversions in secret to other religions because apostasy is banned and, in some cases, punishable by death, to an abandonment of religion in favor of agnosticism or atheism. Responding to the survey, 80 percent of the participants said they believed in God but only 32.2 percent identified themselves as Shiite Muslims—a far lower percentage than asserted in official figures of predominantly Shiite Iran.

More than one third of the respondents said that they either did not belong to a religion or were atheists or agnostics. Between 43 and 53 percent, depending on age group, suggested that their religious views had changed over time with 6 percent of those saying that they had converted to another religious orientation.

In addition, 68 percent said they opposed the inclusion of religious precepts in national legislation. Moreover 70 percent rejected public funding of religious institutions while 56 percent opposed mandatory religious education in schools. Almost 60 percent admitted that they do not pray, and 72 percent disagreed with women being obliged to wear a hijab in public.

An unpublished slide of the survey shows the change in religiosity reflected in the fact that an increasing number of Iranians no longer name their children after religious figures.

A five-minute YouTube clip uploaded by an ultra-conservative channel allegedly related to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards attacked the survey despite having distributed the questionnaire once the pollsters disclosed in their report that the poll had been supported by an exile human rights group.

“Tehran may well be the least religious capital in the Middle East. Clerics dominate the news headlines and play the communal elders in soap operas, but I never saw them on the street, except on billboards. Unlike most Muslim countries, the call to prayer is almost inaudible [...]. Alcohol is banned but home delivery is faster for wine than for pizza [...]. Religion felt frustratingly hard to locate and the truly religious seemed sidelined, like a minority,” wrote journalist Nicholas Pelham based on a visit in 2019 during which he was detained for several weeks.

In yet another sign of rejection of state-imposed expressions of Islam, Iranians have sought to alleviate the social impact of COVID-19 related lockdowns and restrictions on face-to-face human contact by acquiring dogs, cats, birds, and even reptiles as pets. The Islamic Republic has long viewed pets as a fixture of Western culture. One of the main reasons for keeping pets in Iran is that people no longer believe in the old cultural, religious, or doctrinal taboos as the unalterable words of God. “This shift towards deconstructing old taboos signals a transformation of the Iranian identity—from the traditional to the new,” said psychologist Farnoush Khaledi.

Pets are one form of dissent; clandestine conversions are another. Exiled Iranian Shiite scholar Yaser Mirdamadi noted that “Iranians no longer have faith in state-imposed religion and are groping for religious alternatives.”

A former Israeli army intelligence chief, retired Lt. Col. Marco Moreno, puts the number of converts in Iran, a country of 83 million, at about one million. Moreno’s estimate may be an overestimate. Other studies in put the figure at between 100,000 and 500,000. Whatever the number is, the conversions fit a trend not only in Iran but across the Muslim world of changing attitudes towards religion, a rejection of state-imposed interpretations of Islam, and a search for more individual and varied religious experiences. Iranian press reports about the discovery of clandestine church gatherings in homes in the holy city of Qom suggest conversions to Christianity began more than a decade ago. “The fact that conversions had reached Qom was an indication that this was happening elsewhere in the country,” Mirdamadi, the Shiite cleric, said.

Seeing the converts as an Israeli asset, Moreno backed production of a two-hour documentary, Sheep Among Wolves Volume II, produced by two American Evangelists, one of which resettled on the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, that asserts that Iran’s underground community of converts to Christianity is the world’s fastest growing church.

“What if I told you the mosques are empty inside Iran?” said a church leader in the film, his identity masked and his voice distorted to avoid identification. Based on interviews with Iranian converts while they were travelling abroad, the documentary opens with a scene on an Indonesian beach where they meet with the filmmakers for a religious training session.

“What if I told you that Islam is dead? What if I told you that the mosques are empty inside Iran? [...] What if I told you no one follows Islam inside of Iran? Would you believe me? This is exactly what is happening inside of Iran. God is moving powerfully inside of Iran?” the church leader added. Unsurprisingly, given the film’s Israeli backing and the filmmaker’s affinity with Israel, the documentary emphasizes the converts’ break with Iran’s staunch rejection of the Jewish State by emphasizing their empathy for Judaism and Israel.

Reduced Religiosity

The Iran survey’s results as well as observations by analysts and journalists like Pelham stroke with responses to various polls of Arab public opinion in recent years and fit a global pattern of reduced religiosity. A 2019 Pew Research Center study concluded that adherence to Christianity in the United States was declining at a rapid pace.

The Arab Youth Survey found that, despite 40 percent of those polled defining religion as the most important constituent element of their identity, 66 percent saw a need for religious institutions to be reformed. “The way some Arab countries consume religion in the political discourse, which is further amplified on social media, is no longer deceptive to the youth who can now see through it,” Alhussein, the Gulf scholar, said.

A 2018 Arab Opinion Index poll suggested that public opinion may support the reconceptualization of Muslim jurisprudence. Almost 70 percent of those polled agreed that “no religious authority is entitled to declare followers of other religions to be infidels.” Similarly, 70 percent of those surveyed rejected the notion that democracy was incompatible with Islam while 76 percent viewed it as the most appropriate system of governance.

What that means in practice is, however, less clear. Arab public opinion appears split down the middle when it comes to issues like separation of religion and politics or the right to protest.

Arab Barometer director Michael Robbins cautioned in a commentary in the Washington Post, co-authored with international affairs scholar Lawrence Rubin, that recent moves by the government of Sudan to separate religion and state may not enjoy public support.

The transitional government brought to office in 2020 by a popular revolt that topped decades of Islamist rule by ousted President Omar al-Bashir agreed in peace talks with Sudanese rebel groups to a “separation of religion and state.” The government also ended the ban on apostasy and consumption of alcohol by non-Muslims and prohibited corporal punishment, including public flogging.

Robbins and Rubin noted that 61 percent of those surveyed on the eve of the revolt believed that Sudanese law should be based on the Sharia or Islamic law defined by two-thirds of the respondents as ensuring the provision of basic services and lack of corruption. The researchers, nonetheless, also concluded that youth favored a reduced role of religious leaders in political life. They said youth had soured on the idea of religion-based governance because of widespread corruption during the region of Al-Bashir who professed his adherence to religious principles.

“If the transitional government can deliver on providing basic services to the country’s citizens and tackling corruption, the formal shift away from Sharia is likely to be acceptable in the eyes of the public. However, if these problems remain, a new set of religious leaders may be able to galvanize a movement aimed at reinstituting Sharia as a means to achieve these objectives,” Robbins and Rubin warned.

Writing at the outset of the popular revolt that toppled Al-Bashir, Islam scholar and former Sudanese diplomat Abdelwahab El-Affendi noted that “for most Sudanese, Islamism came to signify corruption, hypocrisy, cruelty, and bad faith. Sudan is perhaps the first genuinely anti-Islamist country in popular terms. But being anti-Islamist in Sudan does not mean being secular.”

It is a warning that is as valid for Sudan as it is for much of the Arab and Muslim world.

Saudi columnist Wafa al-Rashid sparked fiery debate on social media after calling in a local newspaper for a secular state in the kingdom. “How long will we continue to shy away from enlightenment and change? Religious enlightenment, which is in line with reality and the thinking of youth, who rebelled and withdrew from us because we are no longer like them. [...] We no longer speak their language or understand their dreams,” Al-Rashid wrote.

Asked in a poll conducted by The Washington Institute of Near East Policy whether “it’s a good thing we aren’t having big street demonstrations here now the way they do in some other countries”—a reference to the past decade of popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq and Sudan—Saudi public opinion was split down the middle. The numbers indicate that 48 percent of respondents agreed and 48 percent disagreed. Saudis, like most Gulf Arabs, are likely less inclined to take grievances to the streets. Nonetheless, the poll indicates that they may prove to be more empathetic to protests should they occur.

Tamimi Arab, the Iran pollster, argued that his Iran survey “shows that there is a social basis” for concern among authoritarian and autocratic governments that employ religion to further their geopolitical goals and seek to maintain their grip on potentially restive populations. His warning reverberates in the responses by governments in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere in the Middle East to changing attitudes towards religion and religiosity. They demonstrate the degree to which they perceive the change as a threat, often expressed in existential terms.

Mohammad Mehdi Mirbaqeri, a prominent Shiite cleric and member of Iran’s powerful Assembly of Experts that appoints the country’s supreme leader, described COVID-19 in late 2020 as a “secular virus” and a declaration of war on “religious civilization” and “religious institutions.”

Saudi Arabia went further by defining the “calling for atheist thought in any form” as terrorism in its anti-terrorism law. Saudi dissident and activist Rafi Badawi was sentenced on charges of apostasy to ten years in prison and 1,000 lashes for questioning why Saudis should be obliged to adhere to Islam and asserting that the faith did not have answers to all questions.

Analysts, writers, journalists, and pollsters have traced changes in attitudes in the Middle East and North Africa as well as the wider Muslim world for much of the past decade, if not longer. A Western Bangladesh scholar resident in Dacca in 1989 recalled Bangladeshis looking for a copy of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses as soon as it was banned by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, who condemned the British author to death. “It was the allure of forbidden fruit. Yet, I also found that many were looking for things to criticize, an excuse to think differently,” the scholar wrote.

Widely viewed as a bastion of ultra-conservatism. Malaysia’s top religious regulatory body, the Malaysian Islamic Development Department (Jakim), which responsible for training Islamic teachers and preparing weekly state-controlled Friday sermons, has long portrayed liberalism and pluralism as threats, pointing to a national fatwa that in 2006 condemned liberalism as heretical. “The pulpit would like to state today that many tactics are being undertaken by irresponsible people to weaken Muslim unity, among them through spreading new but inverse thinking like Pluralism, Liberalism, and such. The pulpit would like to state that the Liberal movement contains concepts that are found to have deviated from the Islamic faith and shariah,” read a 2014 Friday sermon drafted and distributed by Jakim.

The fatwa echoed a similar legal opinion issued a year earlier by Indonesia’s semi-governmental Council of Religious Scholars (MUI) labelled with SIPILIS as its acronym to equate secularism, pluralism, and liberalism with the venereal disease. The council was headed at the time by current Vice President Ma’ruf Amin, a prominent Nahdlatul Ulama figure.