#German pianists

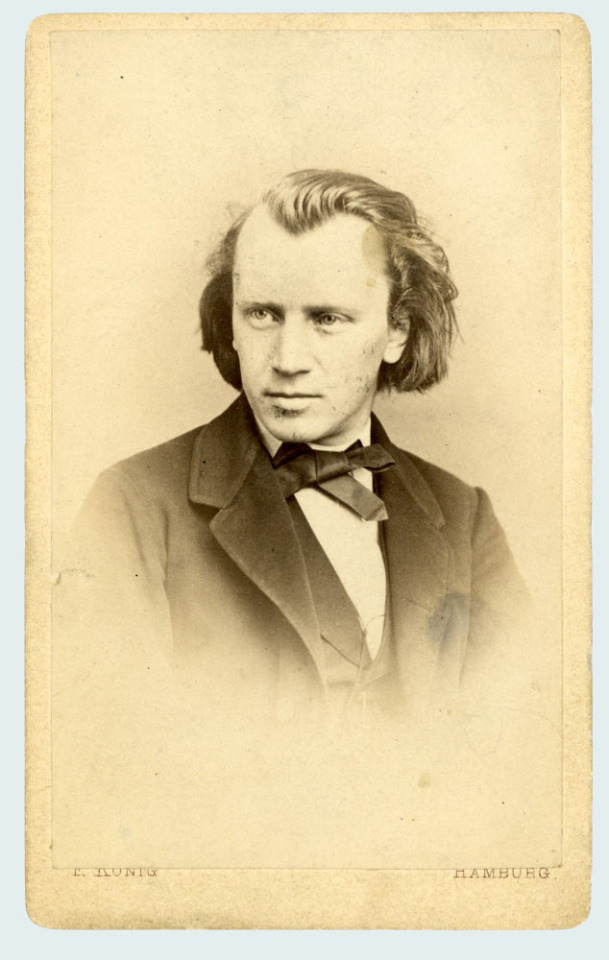

Photo

Johannes Brahms, 1862

Carte de visite by F. König Photograph, Adolphsplatz No. 7, Hamburg

Brahms-Institut an der Musikhochschule Lübeck

#Johannes Brahms#Brahms#composers#German composers#cartes de visite#portraits#portrait photographs#F. König Photograph#German Romanticism#Romantic composers#Romanticism#German pianists#Three Bs#1860s#19th century#19th-century composers#classical music#classical musicians#German music

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

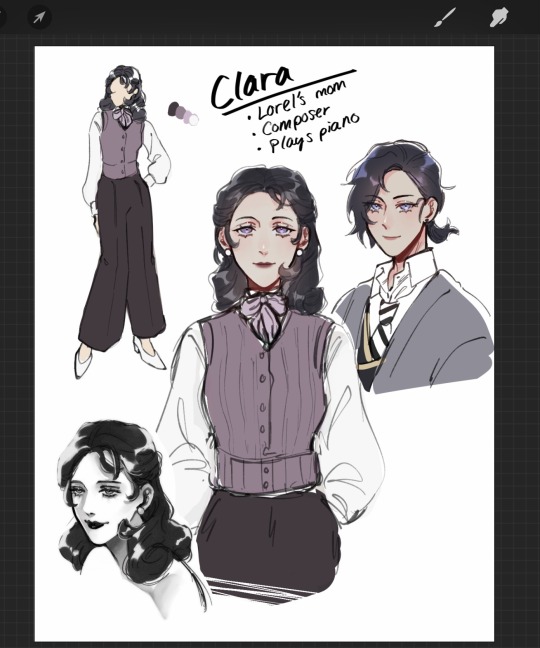

Oh right i should probably show yall lorel’s mom concept LOL, she’s a composer/pianist..music runs in the family.....

#my art#twst oc#lorel#clara#i named her clara just bc it was the first thing i thought of and it sounded pretty and thought it fit#but turns out there was a composer/pianist named clara schumann who composed music to the german poem die lorelei#and i named lorel after the myth of lorelei#unintentionally connected 🙊#also idk if I’ll keep the color scheme hghdhdh i had a hard time deciding on one 😭

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Dear listener, this will be my final musical post of this year and you know I’m gonna end it on an eternal banger. Godspeed to ALL my followers on Tumblr, happy holidays! Let’s have a great, and positive 24'. Fret thee not, I will be back with more tuneskis next year. That said, I’ve been commenting on classical music for the end of 23'. If you’re just joining me on my page I alluded to Bach and Vivaldi in previous weeks… along with a generous peppering of pejorative comments when I was describing myself listening to modern radio. Modern radio was the REASON I started listening to classical music again this year. Why? Because radio BLOWS. Actually, the programming blows and modern music SUCKS. Classical music on the other hand, for all its technological limitations and despite its clear crow’s feet, is at least quality music. Timeless even! So, for Christmas this year, let’s focus on the excellence of execution for music in the 1800’s, Johannes Brahms. Inventor of great individual and collectivized musical works, and the final exhibition in my three-part 23' classical showpiece. At the end of 24', join me for the likes of Mozart and Beethoven, but for now, smash play and enjoy the uniquely holiday and dream-time piece above. Recognize it? Thought you might, dear listener. For those of you who stay and read my little commentaries on these musical posts I really appreciate it. When you read them, you’re spending time with me in a way. Thanks for your time!

For his time, the mid to late 1800’s in Europe, Johannes Brahms became the tip of the spear in Germanic symphonies and sonatas. Writing something like two hundred songs in his lifetime, he started off in his young teens as a naturally talented pianist and played in inns and brothels around the docks of Hamburg to help his family generate money. For such humble beginnings, he also began composing his own music and performing concerts with other notable musicians such as Eduard Reményi. Through further networking, Brahms became closely associated with other virtuosos and composers like Joseph Joachim and Robert Schumann. Schumann helped boost Brahms’ career when his compositions were featured in a media periodical called Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Now, I’m not gonna lie, this guy is not my favoite composer and if I’m being 100% honest, I think his symphonies are a little boring. A lot of it is just too lite and plodding for my taste. Don’t get me wrong, the man was a God among normal humans, but when it comes to personal taste, I prefer orchestral symphonies by the likes of Bach and Vivaldi. However, where I think Brahms’ truly excelled was in his original solo piano works, as he was truly a master of vastly intricate mechanisms and capable of very technical applications with music. He invented harmonies with an almost entirely different kind of emotional resonance than other contemporary classical artists; often using instruments to create a warm and introspective noise rather than a lot of the LOUD AND GALIVANTING classical music that you can find a lot of in the 1700’s. In the 1800’s, the tail end of the Romantic period, concerts and festival overtures were the Taylor Swift venues of the time, and the music of Brahms sold BIG in an international way. He also held the Masters of Composition that came before him in high regard, attempting to cling hard and fast to the idea of ‘absolute music’ (the idea being that music should carry no specific or primary meaning) like composers before him. This conservative view of music put him at odds with composers like Wagner, who wrote program music (introducing literary ideas, a subjective drama, an actual scene, etc). Brahms never married but had a few flings. He was known as being prickly and reserved with adults, but kind-hearted and warm around children. He also died of liver carcinoma in Vienna in the late 1800’s after nearly three decades serving as a musical director, principal conductor, educator and perhaps one of the most influential European composers of all-time.

youtube

I should also be diligent and let you know that his most concentrated and vital works came along after he began visiting Vienna around the 1860’s. His mother passed in 1865, and he afterward created German Requiem, which is widely considered to be a mass for the living. His works such as Hungarian Dances, Violin Concerto, Wiegenlied (also known as Lullaby or the Cradle Song), and his Piano Quintet were all generated in his later years from 1860 to 1885 or so, gimme a break folks I’m not a historian. It’s all about subtle movements with Brahms, or just his harmonic movement in general. On Christmas this year, or every year, consider coming back to this post and clicking on the Best of Brahms. Spend time and mend with family folks! One more musical post and then I need a long break. Enjoy! Image source: https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/best-looking-composers-musicians/johannes-brahms/

#johannes brahms#brahms#music on tumblr#classical#classical music#lullaby#wiegenlied#music from the 1800's#audio video#audio on tumblr#classical composer#composer#baroque#legend#pianist#german composer

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

02/12/24

This is my oldest brother, Theo, watching some gaming live stream and Zues(our German shepherd husky mix) was apparently wanting to watch too😂

I just walked in to Theo's room to tell him I am getting door dash for dinner [it's just Theo and I home tonight- parents are out] and see if he wants me to order him food as well & I walked in to this! Too funny not to snap a picture & share...

#Growing up military#Family#Greyson household pack of hounds#Zues#German shepherd mix#Husky mix#Writer#dancer#athlete#Volleyball#Soccer#Tennis#Pianist#Cellist#Motorcycle#motorcycle rider#motorcycle enthusiast#Life after heart surgery#Heart health problems#hyperthyroidism#malabsorption#Osteopenia#complex ptsd#reactive attachment disorder#generalized anxiety disorder#Anorexia recovery#Orthorexia recovery#ocd#depression

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

German pianist and composer Clara Schumann on a vintage postcard

#schumann#tarjeta#clara#postkaart#german#pianist#sepia#historic#clara schumann#photo#postal#briefkaart#photography#vintage#ephemera#ansichtskarte#old#postcard#composer#postkarte#carte postale

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

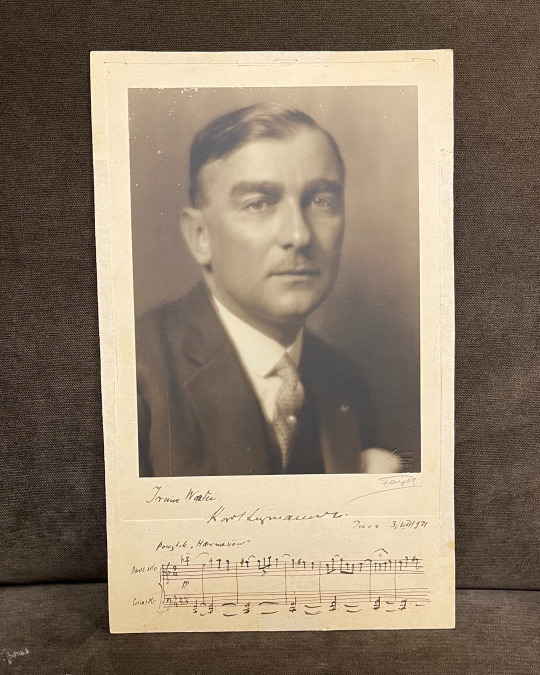

OTD in Music History: Important 20th Century pianist-composer Karol Szymanowski (1882 - 1937) – hailed in some circles as the greatest Polish composer after Frederic Chopin (1810 – 1849) – dies of tuberculosis at a sanitarium in Lausanne, Switzerland.

A member of the “Young Poland” modernist movement that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th century, Szymanowski's early works owe a clear debt to the late-Romantic German school (i.e., Richard Wagner [1813 - 1883], Richard Strauss [1864 - 1949], and Max Reger [1873 - 1916]) as well as eccentric Russian "mystic" pianist-composer Alexander Scriabin (1871 - 1915).

Later on, however, Szymanowski developed an increasingly personal style which blended elements of free atonality / polytonality, French “Impressionism” (drawing from the work of Claude Debussy [1862 - 1918] and Maurice Ravel [1875 - 1937]), and Polish folk music.

Indeed, to that last point, the establishment of an independent Polish state in 1918 inspired Szymanowski to consciously seek to forge a distinctly “Polish” style of “classical” composition – a daunting task that hadn’t been seriously attempted by any major composer since Chopin.

Polish musicologist Aleksander Laskowski has opined that Szymanowski "ultimately succeeded in his goal of inventing a musical language all his own [...] His works were true and ingenious creations, and his oeuvre shows an incredible development from the Straussian and Wagnerian aesthetic, through an interesting and very romantic 'Oriental' period, and finishing with a nationalist period.”

PICTURED: A publicity headshot of the middle-aged Szymanowski (photographed by the famous “Fayer of Vienna” atelier), which he signed and inscribed to a fan in 1931. Szymanowski has also written out a few measures from the opening of his folk-music-infused ballet “Harnasie," which was not publicly premiered until 1935.

Autograph material from Szymanowski is exceedingly rare.

#Karol Szymanowski#Szymanowski#composer#classical composer#pianist#classical pianist#classical music#music history#music#piano#Young Poland#Modernism#German school#Romantic music#Impressionism#Symphony#Violin Concerto#Concerto#King Roger#classical composer#opera#bel canto#aria#maestro#diva#prima donna#chest voice#Salome#Sonata#Overture

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

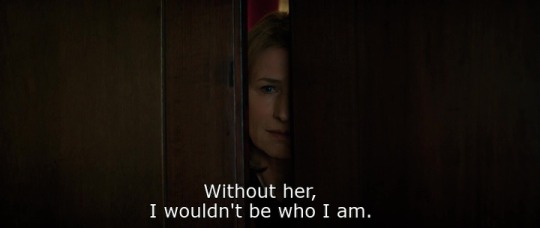

Lara (Jan-Ole Gerster - 2019)

#Lara#Jan-Ole Gerster#German drama film#2010s movies#mother son conflict#Corinna Harfouch#Tom Schilling#love#mother son relationship#Rainer Bock#André Jung#pianist#European cinema#Volkmar Kleinert#Gudrun Ritter#birthday#concert hall#creativity#classical concert#Europe#Berlin#classical music#Germany#performance#不愛鋼琴師#Λάρα#La profesora de piano#Лара#affection#European society

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 4/100 days of productivity

cooked all three meals today (and made my first successful omelet ever. it was a beautiful breakfast.)

5 hours of practice

accompanied day 2 of opera auditions

collaborative piano lesson

finished out semester scheduling

158-day streak on duolingo

counseling appointment

also last official day of being 22 :)

#that piano violin girl#that-piano-violin-girl#studyblr#musicblr#music major#piano#pianist#graduate student#100 days of productivity#grad student#grad school#german#practice makes progress#100 dop

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kimiko Douglass-Ishizaka (born 4 December 1976) is a German-Japanese composer, pianist, and former Olympic weightlifter[1] and powerlifter.[2]

580 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert von Keller (German 1844–1920) - The pianist

104 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the requests/open inbox, this may not be the lane you're looking for, but you made a throw a way mention in a response to the ask about Ice's enforcement of DADT that Bradley and Ice probably got into it at one point about Ice being totally okay with DADT as a policy (which I love your read on Ice being like, 'yeah, nobody should ask and nobody should tell. what's the problem here?') I would love to see that argument go down. Or honestly, just any Ice and Bradley interaction after the reconciliation that suits your fancy. I find that dynamic in your world super interesting. Bradley sees him as a father, Ice sees him as the person whose father I killed. I love the drama.

Five times Ice was so obviously Rooster’s dad + one time he explicitly wasn’t.

[Carole. 1994.]

He’s such a nervous man. Usually that’s not the word people associate with him. Nervous? Never! But he is. Carole Bradshaw’s more a religious woman than a spiritual one. She’s never put any stock into “chockras” or “ouras” or whatever the other girls her age were fooling around with in the late sixties and early seventies. But she does believe that you can understand a person just by looking at him or her, and when she looks at Tom Kazansky, she sees a little anxious creature, shivering in the cold, like one of those tiny spindly dogs who always needs a sweater. Maybe it’s her southern maternal instincts, something primal and animalistic inside her, I need to take care of you—and when he nudges her with a nervous shivering shoulder and whispers, “Can I bum a smoke?” —she reaches down to take his hand and says, “I only have one left. We’ll have to share.”

She knows she makes him nervous. His ears are red, and so’s the back of his neck. It’s early on a Saturday morning, and the church is crowded, and he’s self-conscious about the fact that she’s holding his hand. Good. It’s so rare she gets to make a man nervous anymore. She waves to Bradley, proud in his little striped button-down and his little blue bow-tie, where he’s lined-up with all the other aspiring pianists against the stage along the far wall, under the bare postmodern crucifix. The recital isn’t going to start for another five, ten minutes, and it’s organized by age, so Bradley’s somewhere in the middle. If Tom Kazansky needs a smoke, Carole Bradshaw will bum him a smoke.

They exit out the side door, and the low murmuring of the other proud parents in the church fades to the quiet of the alley. Birds chirping nearby. The sound of a latecoming car on gravel somewhere far away. Her cigarette and the flick of his lighter, her eyes on his mouth and his puff of smoke—it’s lit. He takes a drag, closes his eyes, then passes it to her. “Sorry to make you share,” she says, and she’s watching the red flush creep up the side of his throat with a silent pleasure. When she takes her own pull, she looks down to see that the filter’s gone the sweet red-pink of her old lipstick. Kind of like a kiss, sharing a cigarette.

“That’s okay,” he says. Nervous spindly little dog. “Uh, what’s he playing?”

“Beethoven. ‘Für Elise.’” Then, before he can think to judge, she goes on quickly: “It’s more complicated than you’d think. Goes up and down and all over the place.”

“It’s a good song,” Tom Kazansky says, “though I don’t know too much about piano.” He pauses. “I’m learning a little German, though. I think it’s E-leez-ah. She must’ve been an alright girl if Beethoven wrote a song for her.”

Carole Bradshaw doesn’t know what to say to that. So she says this instead: “Thank you for coming. It made Bradley—well, over the moon, I guess.”

Tom Kazansky smiles shyly. “Sorry Maverick couldn’t come. I know he wanted to.”

Of course he brings up Pete Mitchell. Drags her back into reality. “He’s in Washington again, isn’t he?”

“Correct.” He reaches out for the cigarette; she gives it to him. “TOPGUN’s biggest advocate. I keep telling him he should go into politics. I just talked to him yesterday—he told me he went to the Natural History Smithsonian on Wednesday—he bought Bradley a dinosaur picture book, I think. Does Bradley like dinosaurs?”

Carole Bradshaw shrugs. What nine-year-old boy doesn’t like dinosaurs, but… “He’s more into sea life these days. Whales, sharks, fish.”

“Some fish used to be dinosaurs, they think,” says Tom Kazansky, clearly just trying to fill the silence. Ears red, lips red. Smoke out of his mouth like a fire-breathing dragon.

Carole Bradshaw doesn’t know how much dinosaur history she actually believes. So she says, “It’s still really nice of you to come. You know, Bradley—Bradley thinks of you and Maverick as his—well, his fathers, I s’pose. So it’s nice for you to be here.”

She watches his reaction—just nervousness. Straight anxiety. He doesn’t meet her eyes, like she’s just kicked him in the ribs. He does not want to be Bradley’s father.

She says, “You don’t have to sign any papers, Tom. You don’t have to put a kid seat in your car. I’m just saying. Don’t worry about it.”

He says, “I can hear the kids starting inside—we should probably go back in.”

So Carole Bradshaw drops the cigarette butt to the ground and steps on it with the bottom of her flat. They go inside, and wait for a kindergartener to finish an overly simple “Canon in D” to take their seats again. She takes his hand. He lets her. After another half-hour, Bradley sits down on the bench in front of the hand-me-down Steinway and busts out “Für Elise” without a single missed note. It still shocks her, sometimes, to watch him play—it still shocks her, sometimes, that she is the mother of all that talent. And now maybe Tom Kazansky is the father of all that talent. How did that happen?

At the end of the recital, Tom Kazansky lets go of her hand. She knew he would. Knew his fatherhood is only temporary. But he lets go of her hand to accept Bradley’s great-big hug in the parking lot: “Gosling, that was so good.” Bradley’s proud smile is missing a few teeth. It makes Tom Kazansky laugh.

And after he drops them off at home, and peels away with a wave and a smile, Carole Bradshaw lights another cigarette from the half-full pack she’d brought with her to the recital and brings Bradley out to the backyard so he can play and she can watch him. But before she lets him go, she looks down at him and says flatly, “If kids at school ask you about Uncle Tom and Uncle Pete—you need to tell them they’re just friends.”

And in his eyes, she can see the confusion of a little boy who hadn’t been aware that Tom Kazansky and Pete Mitchell were anything other than just friends—the confusion of a little boy learning about duplicity for the first time in his life.

“Okay,” he says, so she lets him go.

—

[Maverick. 1998.]

“Don’t go easy on him,” Maverick hollers breathlessly over his shoulder, fishing around in the ice chest in the sand for two cans of Coors; “He just joined the J.R.O.T.C.; don’t go easy on him; he’s tougher than all your squadrons combined; beat him into the dirt…”

“Thanks, Uncle Mav,” shouts Bradley from across the volleyball court, where he’s getting initiated into one of the volleyball teams of younger fighter pilots.

Maverick flashes him a thumbs-up and finds his T-shirt on the first bleacher bench, pulls it on with one hand, and then hops up the rest of the benches to sit with Ice, who’s got his CVN-65 ballcap on and a book open in his lap and is offering informal career advice to one of the other lieutenants: “Yeah, so, in my opinion, it’s all down to what you think you can stomach… If you want me to look over your C.V., I can totally do that—I think I’m free Monday at around thirteen-hundred, if you want to stop in to talk. Not a problem. Not a problem. Alright. See you later.” He watches the lieutenant go, then lolls his head over to look at Maverick, who’s tossing an ice-cold can of Coors up and down. “Hey. Good game. —Coors, Mav? This is an insult.” But he takes the offered can anyway, looking out onto the court, where Bradley—fourteen and just entering his beanpole phase of evolution—is currently spiking the ball. “Cool.” It’s a nice summer Saturday, a casual opportunity for the officers of Miramar to socialize with their families (Ice is wearing a golf shirt and jeans), and by now pretty much everyone knows that Maverick Mitchell’s raising his friend’s kid and that he and Captain Kazansky are good friends, so this is pretty nice. Not much to hide.

“C’mon,” Maverick says, popping open his own can, “you and I were having a scintillating conversation, a few minutes ago.” He’s hunting around for the sunscreen so the tops of his feet don’t burn to ashes in the sun.

“Scintillating. That’s a big word for you. Wow.”

“You’re rubbing off on me, Sir Reads-a-lot—”

“See, that’s funny,” Ice interjects, “because I seem to recall, before you so-rudely interrupted me to go play volleyball with the kids, I was telling you that it’s really not that interesting. It’s actually, Maverick, quite boring.”

“Well, I’m intrigued now. Go on. Finish it off, I wanna know.”

Ice slaps his book shut and gives the long tired sigh of a man who is very self-conscious about the fact that he’s about to turn forty. He pops the tab on his can of Coors and huffs in exasperation when it foams all over his hand. “I mean it, my family history’s really not that interesting. Typical eastern-European immigrant shitshow. U.S. officials change one letter in our last name and everyone loses their goddamn minds… Actually, that story might be apocryphal, I keep forgetting which former Soviet Socialist Republic I’m actually from, I just can’t remember, all the borders got redrawn so many times, one of ‘em…”

Maverick smiles and pulls his TOPGUN ballcap back down onto his head, tugs the brim down low over his eyes so he can tip his head back and not go blind from the summer sunshine. He’d thought Ice would be reluctant to share his family history, but it turns out that most people are just afraid to ask him, and he’s actually pretty eager to talk, if you just ask. Maybe over-eager. He’s rambling. Maverick cuts him off: “Yeah, you do have a left curve to you, don’t you. Genetic.”

The dirty joke strikes Ice dumb for a second, but then he forges ahead, wisely choosing not to engage. He keeps going, oblivious to the fact that Maverick’s not really listening… “Anyway, my grandfather was Jewish, but he died literally the second he stepped foot in America, so it doesn’t count…my grandmother was Orthodox, crazy story how they ended up together; actually, that story’s probably apocryphal, too…she’s the one who raised me, pretty much. I told you that. She brought my dad out to Southern California when he was a little kid, but I don’t know if you’ve noticed, So-Cal’s not exactly the Mecca of Orthodox churches or anything, so he wasn’t very religious at all… My mom was from Milwaukee, I think. Or maybe Minneappolis. Some kinda Protestant. Forget which kind. The preachy kind. But then she died and I didn’t have to go to church anymore, so I didn’t.”

“You just never believed?” Maverick mumbles, half-joking.

“Nah. I mean, I always had too many questions no one wanted to answer. For instance: okay, say you’re bad. Say you commit sin…”

“I’ve never sinned, sir. You’re talking hypothetically.”

“Right. Me, neither. Hypothetically speaking. So you go to Hell. Well, the devil’s there, too, ‘cause he’s a sinner, too. But why’s he want to punish you? What does he get out of it? You’re both in the same boat!”

“Probably a sexual thing,” says Maverick, watching the purple-green imprints of the sun dance around behind his eyelids. “He probably gets off on it. The devil, I mean.”

Ice laughs and laughs. “Sure. Try saying that in front of my mom and see if you survived. I learned pretty early on that they don’t want you to be too curious. So I kept all my questions to myself.” He’s also joking, not taking this super seriously, but that’s a pretty in-character answer. “What about you, Mav?”

“If I’ve told you my family’s history once, I’ve told you a thousand times…” That’s a joke. Maverick’s the one who doesn’t like talking about his family history. Ice hasn’t heard any of it, and for good reason. Maybe someday he’ll tell him about it. “Later. But, remember, I used to be Southern Baptist? Jesus, I was serious into that shit, Ice.”

Ice snorts. “Yeah, right. You.”

“Not joking. I had about eighty girlfriends between fourteen and eighteen, but that’s the most pious I’ve ever been. Lotsa loopholes to make my relationships biblical. Was thinking about being a youth pastor. —I’m not joking. It was my whole personality, for a while. Most of my childhood, anyway.”

Ice is still laughing in disbelief. “Oh, yeah? And then what happened?”

Maverick smiles. “…Got hooked on sinning.”

“…Yeah,” Ice replies, and Maverick can hear the nervous smirk in his voice, “I guess I’d know a little something about that.”

And normally that would be the end of the conversation. But Maverick’s feeling a little sun-drunk, a little giddy, and he’ll never, ever, ever grow out of instigating stupid arguments with Ice just for the fun of it. From beneath the brim of his ballcap he mutters, “…You think Carole’s brainwashing her kid?”

Ice huffs a laugh, and says through a lazy yawn, “I’m not militant in my atheism, no.” But he, also, will never, ever, ever grow out of instigating stupid arguments with Maverick just for the fun of it, and his curiosity’s clearly been piqued. He stews in it for a second before he snaps, “Do you think Carole’s brainwashing her kid?”

“I’m just saying she has him readin’ outta the Bible, like, five times a day. She sends him to church camp. Does something to a kid.” He has no dog in this fight, but this is fun.

“And what did it do to you?” Ice says, reaching down to shove his shoulder good-naturedly. “Weren’t you just telling me not five seconds ago how you used to be the perfect model of Christian charity?” Maverick mumbles a retort sleepily; Ice pushes on through it: “Bradley’s a human being. Either he grows out of it like you did, or he doesn’t, in which case, whatever, land of the free. That’s the First Amendment. You swore an oath to the Constitution. Maybe you should read it.”

“I’ve read it. I’m not Congress, shithead. How’s it go, you want me to cite it to you directly, ‘Congress shall make no law…’ actually, I don’t know what comes after that. Got me there.”

“Don’t call me shithead, dipshit. And whatever. Good thing he’s Carole’s kid and not yours, then. He’s got a mom who wants him to go to church. It’s up to him if he wants to listen to her or not. That’s growing up.”

Maverick tips up the brim of his ballcap to look at him, sprawled out in the bleachers very unprofessionally for the CO of this entire volleyball court, and snaps back, “Well, he’s a little bit my kid. The same way he’s a little bit your kid.”

Ice just flicks his sunglasses down onto his nose and purses his lips and neither confirms nor denies this allegation.

They watch the game together for a while, Ice’s toes pressed against Maverick’s lower back discreetly, trying to work their way under Maverick’s T-shirt. Until one of the young pilots approaches a few minutes later: “Sir!” / “What’s that kid’s call sign again?” Ice mumbles to Maverick, prodding him with his foot. / “Hooker.” / “No shit.” / “Sir!” says Hooker again. / “Which one of us, kid?” says Maverick. / “Captain Kazansky, sir. We’ve got a spot opening up. Wanna play?”

Maverick looks up at Ice expectantly. Ice sighs and harrumphs and waffles for a minute— “I’m too old for this shit.”

“Sir,” says Maverick, “it’s not a competition, but if it were, I’d be winning.”

Lighting the fire of competition under Ice like that is always a good strategy. He rolls his eyes, but immediately stands and tugs off his shirt and rolls up the cuffs of his jeans; “I’ll only play if I can play with the kid.”

So Maverick watches the teams get scrambled again with a smile, and sits up to watch Ice join Bradley in the sand. Bradley’s only just now taller than Ice, and Ice clearly isn’t used to having to reach up to curl an arm around his shoulders to strategize, his eyes narrowed like an eagle’s, staring down the competition. Maverick can read his lips from across the pitch: Alright, kid, I’ve been watching for a while, and I think I know these guys’ strengths and weaknesses…okay, here’s what we’re gonna do… And the game begins when Bradley spikes the ball.

Ice won’t always be this fun, this down-to-earth, this human. The admiralty and the guilt and the grief of the years to come will strip it all away from him, bring him back to the cold, remove him from his own humanity. And maybe, even if it isn’t conscious, Maverick can recognize that, right now, watching Ice dive into the sand with a laugh: this summer sunshine is only temporary. It’s gonna have to end at some point. So he doesn’t take it for granted. He keeps his eyes open and watches and tries to commit it to memory.

And after the game, Ice and Bradley come over so Ice can finish his beer and put his shirt and his baseball cap back on, and Maverick can make fun of them for losing. And: “What were you guys talking about for so long before the game?” Bradley asks Maverick with a grin.

“Whether or not your mom’s brainwashing you,” Maverick says.

“Oh!” Bradley says mildly. “…No, I don’t think so!”

“Oh, that’s a great start,” Ice laughs. “You would’ve made a great Soviet. No, I don’t think I’m getting brainwashed. Hey, by the way, Gosling, if you want a beer, Maverick and I won’t tell anyone.”

“Aw, really?” whispers Bradley. “Thanks, Uncle Ice!” And he races down the bleachers towards the ice chest in the sand.

Maverick watches Ice watch him go, fingers still pinching the brim of his CVN-65 ballcap, clearly worrying about something the way Ice always is.

Then he looks down at Maverick, stares openly for a minute, and says, “You don’t think we’re teaching him to rebel too much, do you?”

—

[Bradley. 2000.]

“Kiddo! You’re here early!” It was Uncle Ice, walking through his own front door, catching a glimpse of Bradley watching the Astros-Nats game on the TV. He was still in uniform, but smiling wide, and he set his bag down near the couch and leaned over to ruffle Bradley’s hair goodnaturedly.

“Practice ended early today.”

“Oh, okay. Cool. Maverick should be home soon, still at work—your mom’ll be here in about an hour—she told me to put the chicken breasts in the oven, but you know me, every time I use this oven I set off the fire alarm, so you oughta help me with that…”

“And,” Bradley said, watching Uncle Ice wash his hands in the kitchen sink, “I got here early because I wanted to talk to you.”

“Oh, sure!” chirped Uncle Ice. Then he paused, sensing a trap. “What about?”

“Advice,” Bradley mumbled. He took a deep breath, and stood to follow Uncle Ice into the kitchen “I was just—I was just curious. If you had any advice for me joining the Navy. You know, with me being gay, and all. How do I—I don’t know. I’ve been thinking about it a lot. It’s kinda been weighing on me. Do you have any advice?”

Uncle Ice was still drying his hands off on a kitchen towel. Rubbing them red and raw. And when he raised his head to speak, there was something dull and startled in his eyes: “I don’t, um—no, I don’t—I don’t know anything about that. —You should ask Uncle Maverick about that.”

“I did,” Bradley said desperately, because he had. Yes, he’d gone to Uncle Mav first. “He—he told me to talk to you.”

“…Oh,” said Uncle Ice, now standing in front of a shelf to return one of his books to it. This surprised him. Maybe hurt him a little. “No. I—I, I wouldn’t know anything about that.”

“But—”

“And there are probably better people to ask than me or Maverick. I—I don’t know—that’s not really my…I don’t know.”

“Okay.”

Uncle Ice swallowed, put the book back on the shelf, then clasped his hands together and set them on the shelf, too, as if leaning over his captain’s desk to chastise someone. He blinked for a long moment. Clearly shifting gears. Becoming someone else so easily. Why couldn’t Bradley do that? “But I can tell you this,” he said, and his voice had gone grave and dim, “and I know you and I don’t always see eye-to-eye on politics—but I can tell you this, professionally, because I respect you, and I care about you, a lot—you’re going to have to keep it a secret.”

Dismayed, Bradley said, “Why?”

“Why’s a funny question to ask about something like this,” said Uncle Ice curtly. He shrugged. “Why? Because it’s the law. That’s why.”

Bradley swung his bat at the hornets’ nest. This was always dangerous with Uncle Ice. “It shouldn’t be a law. Don’t you think?”

“Doesn’t matter what I think. It’s the law. And we get paid to enforce the law, internationally speaking. And the military doesn’t work if personnel refuse to follow the rules in broad daylight. So.” He trailed his fingertip along the spines of all his precious books, then eventually found a different one, started flipping through it absentmindedly. “And even if it weren’t the law, it’d still get enforced extrajudicially. You know what that means?” He did that, when he was intentionally being cruel; used big words that Bradley didn’t know to make himself sound smarter. “It means outside the law. The way people talk to you. The way people respect you or don’t respect you. And this business, the one you want to go into, is all about respect. Being a pilot is kind of like being a knight: you have to be noble, you have to be honorable, you have to respect your service and your adversaries and yourself. And because I respect you, and because I care about you a lot, I’m just telling you the truth—you’re going to have to keep it a secret.”

Bradley blinked. There was something crushing and overwhelming about the truth—maybe the fact that it was the truth, maybe the fact that he hated the fact that it was the truth. It made sense. But it also meant his future was unspeakably bleak. He tried to speak over the lump in his throat when he said, “Yeah. That’s what Maverick told me, too.” And what he’d wanted to hear from Uncle Ice was that Uncle Mav was telling a lie.

Something went soft and slightly wounded in Uncle Ice’s eyes. “I’m sorry,” Uncle Ice said gently. “I wish I could give you better advice than that. But that’s all I know. I don’t know any more than that.”

“Don’t you want to know more than that?”

“No.”

And thus did the generational gap widen into a chasm.

—

[February 2003.]

Dear SN Bradshaw, / Please call/email/write me back when you get a chance. / Love Uncle Iceman.

…

[August 2003.]

Dear AN Bradshaw, / I hope you’re doing all right. I hope at some point you and I can get in touch to talk. Please let me know if there is some other address I should be sending my letters to. I am not sure if they are finding you. / Love Uncle Iceman.

…

[May 2004.]

Dear AN Bradshaw, / I wanted to congratulate you on your acceptance to college. Yours is a very good AE program & you should feel very proud. Please let me know if there’s anything you might need as you prepare to start your first year. / Love Uncle Iceman.

…

[August 2010.]

Dear LT Bradshaw, / I wanted to let you know that I’ll be at NAS Oceana for a conference from December 6-9. I understand that’s your neck of the woods—would you be interested in having dinner with me on either that Tuesday or Wednesday night? I would love to hear how you’ve been doing. You can reach my secretary at the number below. / Love Uncle Iceman.

…

[October 2014.]

Dear LT Bradshaw, / We Maverick and I want to wish you a Happy Birthday 30th Birthday. We heard you are deployed out in the Atlantic now—we hope you will be able to enjoy the enclosed gift card when you make it back to terra firma. Our updated personal cell numbers are below. / HAPPY BIRTHDAY! FROM UNCLE MAVERICK & Uncle Iceman.

…

“Haven’t heard back from the kid yet.”

“…You think we ever will?”

The longest silence.

—

[Pacific Air Type Commander Beau Simpson. 2016.]

You could see it in the way they held themselves. An utmost similarity. Aristocratic propriety. Maybe a little sense of entitlement: look how hard we’ve worked to be here. All three of them had it. More accurately: Captain Mitchell and Admiral Kazansky both had it, and had passed it down to their son.

“Captain Mitchell.” Everyone was watching. The sun had only just set; the sky was melting from horizon-red through orange and yellow and teal up to midnight black above them.

“It’s an honor, sir,” said Captain Mitchell, accepting Admiral Kazansky’s handshake. God, you’d never know it by looking at them. Half the people here on this Roosevelt flight deck knew about them, but they were so convincing that more people weren’t sure. TYCOM Simpson glanced at Rear Admiral Bates, who glanced back in confusion—I thought they were…? They were, TYCOM Simpson signaled, just abnormally good at keeping it a secret.

“Honor’s all mine, Captain,” said Admiral Kazansky, and he passed by without a second glance.

And when he made it down the line of aviators to Lieutenant Bradshaw—you could see it. The similarity in the way they held themselves. Straight and rigid and unyielding. Cold and dismissive beyond belief, even to each other. Admiral Kazansky held out a hand. Lieutenant Bradshaw took it, but refused to make eye contact. Quiet rebellion under the radar: Admiral Kazansky had taught him well.

TYCOM Simpson glanced at Captain Mitchell, to gauge his reaction. And for once, he and Captain Mitchell were clearly thinking the exact same thing.

Like father, like son.

You could see it in their stubborn determination. How far they were willing to go. How hard they were willing to push. How long they were willing to hold their own hands to the fire, if it meant the familiar painful comfort of staying warm. “Ice-cold, huh?” TYCOM Simpson asked him the next morning, trying to pin down their strategy, trying to secure a guarantee that their family would do what their country asked of them, even if that meant death. Even if that meant the ultimate sacrifice.

“Only when I have to be,” replied Admiral Kazansky, which meant always, and—soon thereafter, he ordered Lieutenant Bradshaw to his death.

But also, Lieutenant Bradshaw went willingly, too.

“Dagger One is hit.”

“Dagger Two is hit.”

Loss is supposed to hit a man in stages. Isn’t that the truth? —Not so for Admiral Kazansky, whom grief obviously swallowed whole in just an instant. He did not break, or bend under its weight. Just stood there staring at the E-2D AWACS screen with wide wounded eyes—not disbelieving eyes. They were gone. Captain Mitchell and Lieutenant Bradshaw were gone. He was in no denial whatsoever. He had leapt straight to acceptance.

“Sir,” said TYCOM Simpson hesitantly, and he reached out to touch him—the stars on his shoulder—guide him back to reality—what must it be like, to lose a son?—to willingly forfeit your family?—

But before he could make contact, Admiral Kazansky drew a breath, moved away, and closed his eyes for just a second. Perfectly composed, even with the waters of grief closing over his head, even with three dozen observers in this C2 room all scrutinizing him for his response. Perfectly composed. How did he do it? How could he manage? How was he possibly still this proud?

“Vice Admiral Simpson,” he said calmly, “I relinquish my command to you, until you deem me necessary to return to my post.”

“Sir,” said Rear Admiral Bates, darting panicked, sympathetic eyes to TYCOM Simpson, but it was too late—Admiral Kazansky was already leaving the room. Head held high and steady.

Some confusing weeks later, after Captain Mitchell and Lieutenant Bradshaw returned from the dead, TYCOM Simpson and Rear Admiral Bates would casually debrief the mission together in the lobby bar of the Waldorf-Astoria in Washington, D.C. No hard liquor, just beers. Just barely enough alcohol to give them an excuse to philosophize. “You think pride is a sin or a virtue?” TYCOM Simpson found himself asking, tracing the rim of his gilt-edged Stella Artois glass with a finger, after having recounted the above testimony.

“Neither,” said Rear Admiral Bates. “Gotta be a vice.”

“A vice.”

“Yeah. Good men die because of pride, bad men die because of pride…we send our sons to battle because of pride…wars are fought and won and lost because of pride… every war in human history, when you boil it down, begins when someone says, ‘You’re wrong and I’m right, and I’m proud of my own righteousness, proud enough to kill, proud enough to die, proud enough to send my sons to die…’”

“Oh, okay. That’s the root of all human conflict, then, according to you, Warlock. Okay.”

Rear Admiral Bates smiled and laughed at himself, too. Pride, he mouthed. Then shook his head. “We’re a proud species. It’s our vice.”

TYCOM Simpson was thinking about the two proudest men he knew, Admiral Kazansky and Lieutenant Bradshaw, and wondered what it was, exactly, that had driven a wedge between them, you’re wrong and I’m right and I’m proud enough of my own righteousness to send you to your death/inflict my death upon you… And then he remembered the warnings he’d previously received about Lieutenant Bradshaw and Lieutenant Seresin and their open relationship, and then he remembered Admiral Kazansky coldly shaking Captain Mitchell’s hand… and he wondered if the wedge between them was exactly that: the matter of pride.

—

[Tom. 2018.]

“Merry Christmas and a happy new year, and all that,” says Pete, raising his glass and reaching over the dining table to clink rims with Tom and then Bradley. “A good year! A really good year! —Sorry your guy couldn’t be here, Rooster. We’ll call him tonight before you go. Tell him we miss him.”

“Where is he again?” Tom asks.

“Washington,” Bradley says with a smile. “Big conference at the Pentagon. I’ll see him next week.”

“You know,” Pete says with a sly grin directed at Tom, “I’ve never actually heard the story of how you two got together.”

“Oh,” Bradley says, shrugging as he tears open a dinner roll, “not that interesting. Pretty much what you’d expect. Inter-squadron competition-turned-sexual tension. Not exactly within regs, but we did meet each other before D.A.D.T. got repealed, so it wasn’t like we’d’ve ever been within regs, either…” (All the while, Tom’s smirking over the rim of his wine glass at Pete, No, Mav, I’m not gonna tell him I had them reassigned to the same boat…) “We broke up when I got sent to TOPGUN. But we figured it out eventually.”

“Glad you did. Sorry he couldn’t be here.”

Bradley hesitates, then says, “You know what I just realized? I never heard how you two got together…! You’ve never told me that story!”

Tom glances over at Pete, do you want to take this or shall I, and when Pete motions all yours, he sighs and says, “Uh, we don’t really know. We’ve just been telling people nineteen-eighty-six because it’s easy. But in a much more real sense…” He thinks about it, then shrugs. “Whatever. If you really want to know. In nineteen-ninety-three, right after I came back to San Diego to take command at Miramar, he and I had a drunken one-night stand. By accident. Which then turned into twenty-five years of accidental one-night stands. So.”

“Oh, c’mon. You guys bought a house together.”

“Yeah, that,” says Pete, “that was, uh, to facilitate the accidental one-night stands. Make it more convenient for everyone.”

“Cut out the middle-man,” Tom supplies, then shrugs again at the look on Bradley’s face. “That’s our story, kid. It’s not super romantic. We weren’t thinking about it that way. We didn’t know how.”

Pete raises the wine bottle to refill Tom’s glass—though it’s still halfway full—and then raises his eyebrows when he “notices” the bottle’s empty. Changes the subject as he stands: “Okay, what’s everyone feeling? Red, white, what’s next?”

“Red,” Tom says absently. “Anything big, I guess—first cab you see…” But then he thinks about it, and he amends his order before Pete leaves earshot: “Actually—we’ve got that petite sirah we gotta drink—two-thousand-four. Israeli. Might be somewhere in the back, sorry. But now’s a good occasion, I think, to bust it out for the holidays. No reason to save it.”

“Israeli sirah two-thousand-four,” Pete repeats, “okay. I got that.”

Then he steps outside, leaving Tom and Bradley alone. It’s not awkward—they’ve worked really hard over the last two years to make it not-awkward, after the mission—but human beings are human beings. Prideful, stubborn creatures. There will always be a little guilt between the two of them, and a little blame.

“I have to be honest,” Tom says after a moment, interested in being honest for Bradley’s sake, “sorry we don’t have a better story to give you, about us. It is a little hard to talk about.”

“Why?”

“Well—we don’t know the words we’re supposed to use, for one. It’s your generation who sets the standard for that kind of thing. You young people. We’re a little out-of-date. And…well. I guess we’re just jealous of you. It’s hard to talk about.”

“Jealous?” Bradley repeats quizzically. “Why?”

Tom leans back in his chair and really thinks through what he wants to say. This is one of those impromptu speeches you never really intend to make, but are probably still important to get off your chest. “Maverick and I,” he starts carefully, “will never stop feeling guilty about what we did to you. Ever. You need to know that.” And when Bradley scoffs and huffs and tries to interrupt, he goes on, “Not just pulling your papers from the Academy. It goes back further than that. We will always feel like we deprived you of your father. The merits of that feeling are debatable, sure, but it’s a fact of life. A fact of our lives, anyway. And it’s dictated so much of how we live, and how we’ve lived, over the past thirty years. Part of the reason I came back to Miramar in nineteen-ninety-three was to be with you and your mom. Because I felt I owed you that, in return for what I’d taken.”

“You didn’t kill him,” Bradley says. “Or, at least, I never blamed you for killing him. You or Maverick both. You guys were my dads. You didn’t take anything from me. —Excepting the obvious, the Academy, but that was mostly my mom, I guess, so, whatever.”

“I’m just telling you what our lives have been like since the day I met you. Why we did what we did.”

“Okay. But I still don’t understand why you’re jealous.”

Tom smiles, a little faintly. “Because the other part of the reason I came back to Miramar in nineteen-ninety-three was to be with Maverick,” he says, “and I’m jealous of you because I didn’t recognize that at the time. —Everyone hopes, when they have kids—because, look, I’m not your dad, but you are my kid, really—everyone hopes they can bring their kid into a better world than the one they had when they were a kid, and we did. But no one prepares you for how jealous you get when your kid grows up in a better world than you did. I’m not sure people your age understand how hard it was for us when we were your age.”

“I do.”

“Sure, but I don’t think you do. I—I didn’t…” He sighs. “I never meant to fall in love with Mitchell. He never meant to fall in love with me. There certainly were men in relationships in the Navy back then who could make it work—we weren’t those guys. We looked down on those guys. Most people did. And when you were an officer, your job security and your paycheck relied on your subordinates’ respect for you. If we’d rocked the boat, traded away our respect for our relationship, well, we’d have each other, but we’d be out of a job. And then, if we’d been fired—what did we kill all those people for? For nothing! What a waste of all the lives we took! It wouldn’t have been honorable. Would’ve disrespected the Navy, our careers, the men we killed. So we didn’t talk about our relationship. You know that. Didn’t talk about who we were, or what we were doing, or why, because we were afraid of losing our own honor. Didn’t talk about it until the day you two died and came back from the dead. That’s what it took. Maverick still hates talking about some of that stuff, all the labels, all the words—that’s why I sent him to get a bottle at the back of the fridge, he might be out there a while…”

“Cunning,” Bradley says softly, but leaves the space open after he speaks.

Tom looks away. “Maybe this is getting too deep into the weeds. I’m just trying to tell you what it’s been like for us. Not sure how much of this you want to hear.”

“All of it. —All of it.”

Tom clears his throat. “…Well, Maverick keeps trying to convince me that we never wasted any time. And I know there is some truth to that—we didn’t start out liking each other at all—even if we’d been as brave as people your age are nowadays, even if we’d been open with each other about that kind of stuff, we still probably wouldn’t have ended up together. I mean, we really didn’t like each other. Especially right after your dad died, and especially after you left, in two-thousand-two. So maybe it was better for us in the long run that we didn’t talk about it. But I look back on the thirty years I’ve spent with him, and…it still all feels like a waste to me.” Maybe he really is too deep into the weeds. But he just wants Bradley to understand. “Look, Mitchell is, beyond any possible shadow of a doubt, the love of my life. Always has been and always will be. Right? —I just wish I’d known that at the time. I’m jealous of you because you’re exactly the age I was when I came back to Miramar to be with you and your mom and Maverick, and you’re already married, and you won’t ever have to sacrifice any of your honor for your marriage. You’re one of the most respected men in the Navy.”

“So are you, Ice, and you’re also married to another man.”

“I’ll remind you, though it hurts a little, that I’m almost exactly a quarter-century older than you, and you and I got married within a week of each other. I had to wait for times to change.” He holds Bradley’s gaze for a moment, then finishes the last of his dinner and sets his fork down on his plate. “So, if you were ever wondering why Mav and I are a little bitter around you and Jake, well, it’s because we are.”

“Oh,” says Bradley. “See, I always thought it was just because you and Maverick are both notoriously bitter people.”

“We are,” Tom admits through a laugh. Then he continues, “But—you should also know how proud of you we both are. How proud of you we’ve both always been. We’re not very brave men—well, we are, of course, but maybe not in the way that matters. It’s pretty gratifying to have a kid who’s braver than you are. Every parent’s dream, whether we want to admit it or not. You’re brave enough for all of us.”

It’s at this moment that Pete opens the garage door and sticks his head inside and hollers, “Ice, I can’t find it. What about a merlot? Can we do a merlot?”

“No, baby, the sirah,” Tom answers without turning his head. “It’s on the second shelf, you might—have to rearrange some of the bottles—we have too much wine. We need to drink more, me and you.”

“Not a problem,” says Pete, and he shuts the door again.

“It’s on the third shelf,” Tom tells Bradley in an aside. “He’ll find it eventually. He would’ve tried to change the subject six times by now. —The previous Secretary of the Army—he actually just got married this week, I think; I need to send a card—also gay. He and his partner invited Maverick and me out to dinner the last time we were in D.C. Most uncomfortable I’ve ever seen Mav in my whole life. Asking us questions like, ‘How did you guys get together…?’ ‘Was it easier for you guys because you were in the Navy…?’ ‘When did you…know…?’” When Bradley laughs, Tom does, too. It’s really nice, it turns out, to joke about this stuff with someone who understands. “We just made our answers up out of thin air. I was uncomfortable too, admittedly. That’s what I’m saying. Mav and I never learned the vocabulary to answer questions like that.”

Bradley starts taking their plates to the sink. What a good kid. “You know,” he says from the kitchen, glancing over his shoulder when Tom joins him at the counter, “it’s so funny you bitch that you and Mav don’t have a romantic love story, or whatever. When I was a kid, you and him were literally the pinnacle of romance.”

“Oh, really.”

“Yeah. There’s something romantic about the secret, too. When Jake and I made our relationship official—the first time—I begged him to keep it a secret just for a little while. You know; it was sexy, for a few minutes! Something only he and I knew!”

“And you immediately discovered how awful it is, I’m sure,” Tom says noncommittally. “I’m jealous of you that you learned that lesson young. —Yeah, real romantic. Maverick and I could’ve ended each other’s careers fourteen thousand times over. Real romantic.”

“And trusted each other not to,” Bradley points out—

—which makes Tom reconsider.

Yeah, okay, maybe it’s a little romantic. The way Grimm’s fairytales, once you wipe away all the blood, are just a little romantic. “I’m of the opinion that the only thing getting old is good for is looking back on your life through rose-colored glasses. Sure. Historical revisionism it is. It was a little romantic.”

“What’s a little romantic?” says Pete, stepping into the kitchen and triumphantly brandishing his 2004 petite sirah; “Have I missed something funny? —It was on the third shelf, by the way. Could’ve told me that before I went and reorganized the whole fridge.”

Tom graciously accepts the half-annoyed kiss to the cheek, and answers, “Nothing you would’ve laughed at, I’m afraid.”

“Oh, one of those conversations,” says Pete, hunting around in the drawer for the corkscrew. “If you were planning on continuing, I can go out and rearrange the wine bottles by region instead of by year—” and scoffs when Tom kisses him back to reassure him, conversation’s over.

“Did you know,” Bradley says, “your husband is now openly calling you the love of his life?”

“Oh, yeah,” says Pete with a smile, popping the cork from the bottleneck, “he tells me that all the time. Nothing new.” Tops up their glasses, then deftly changes the subject: “Oh, gosh. I never asked. This is the big news. How are you and Hangman enjoying SOUTHCOM?”

“Oh, God,” says Bradley, rolling his eyes. “Let me tell you…”

“I think we did good,” Pete says later that night—they’re alone now, so he’s fine talking—as he tugs loose the tucked sheets to clamber into bed, and when Tom moves to turn off the light he adds, “No, you can keep reading.”

Tom sets his book down onto his chest and pulls his glasses off anyway. “Well, you and I are known for doing ‘good,’” he muses after a second. “We’re pretty universally renowned for being good at stuff. But, regarding what in particular? —Raising our kid?”

“Yeah. We did good.”

Actually, they didn’t do very well at all. But of course that’s not what Pete means. Pete means: it’s shocking and stunningly fortunate that they did as poorly as they did and still somehow ended up with such a good kid. Tom’s looking up at the ceiling and feeling very small. “How did that happen? Genuinely, how did that happen? I did always build getting married into my plan for my life—but I never thought far enough ahead to consider having kids. And now you and I have a kid who’s in his thirties. How’d that happen? I remember when he could barely walk!”

Pete yawns and rolls over onto his side and closes his eyes. “You and I have a kid who earned a Medal of Honor.”

“I know exactly how that happened” —and doesn’t like to think about it too much. “I suppose we’re just a family of overachievers. A lot of failing upwards, you and me. Somehow we failed our way upwards into a very happy lifelong relationship, a superstar kid…a few dozen medals each, ourselves…”

“That’s life,” says Pete sleepily.

“That is not most people’s lives. You’re aware that our lives look nothing like the average person’s life, right? You understand that?”

“That’s our life.”

Tom considers this. Yeah, it is their life. Wild how that happens.

He smiles at the singular word life, sets his book on the nightstand, presses a kiss to Pete’s bare shoulder, and turns off the light.

#happy Father's Day!#some light discussion of religion in this one but u should be used to that with me#this one is long bc it hits a LOT of prompts sry it took a minute#going thru my inbox: for this anon obv#and FTAW (for the anon who) wanted more competitive icemav#for the FOUR anons who wanted ice and bradley to talk about queerness in the navy#FTAW wanted rooster to explain how hangster came to be#FTAW wanted more ice breaking the rules (‘management tier asshole’ lol)#for the THREE anons who wanted more soft 90s icemav#which is hard for me to write bc those years are kinda boring#it’s literally just: they wake up together. Go to work together. raise their kid together. eat dinner together. fall asleep in the same bed#occasionally fuck. Keep it a secret. don’t talk about it.#for 5 years. like… narratively speaking it’s v boring but yeah they’re happy :)#FTAW wanted more of ices prenavy backstory (this isn’t really much but…)#FTAW wanted icemav’s relationship with religion#tom iceman kazansky#pete maverick mitchell#top gun maverick#top gun#icemav#top gun fanfiction#you guys sure love ur anonymity don’t u#i wanna know who’s sending in asks!!! my dms are open!!! Please come say hi!!!#there are some timeline issues wrt Carole in this one sorry. u can deal.

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weird things about my dogs/funny things they do post #929

In the past week Zues, our german shepherd husky mix, has just discovered the existence of the mail man and the fact that he comes to the door every day. Since Zues has realized these things every day between 10-11am(the hour which at some point the mail comes) Zues can be found sitting near the front door and looking out the window for the mail man{pictured below 👇}. When the mail man comes Zues gets very excited and let's out a bark or two like He is this brave guard dog but then he realizes he is literally scared of everything and He quickly turns and runs to hide under the piano bench but still growling and letting out little baby quiet barks smh😆 Zues is literally a skittish cat in dog form.

#growing up millitary#Greyson household pack of hounds#doglover#family#zues#german shepherd mix#husky mix#writer#dancer#athlete#volleyball#soccer#tennis#pianist#cellist#motorcycle rider#motorcycle enthusiast#life after heart surgery#heart health problems#hyperthyroidism#malabsorption#osteopenia#complex ptsd#reactive attachment disorder#generalized anxiety disorder#anorexia recovery#orthorexia recovery#ocd#depression

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

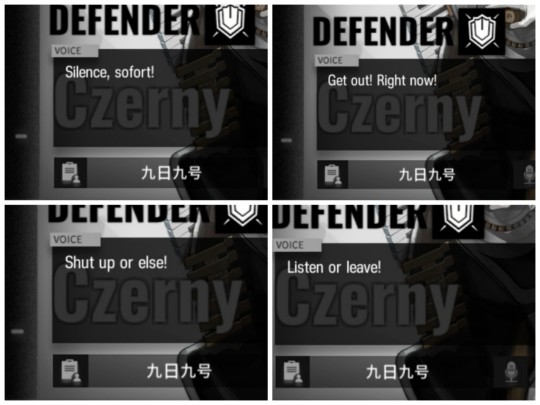

Czerny really, despite the two band camp twinks being great, the standout character for me this event.

I just love how well-crafted he is. You can just feel that whoever wrote him knew very well how to make a interesting and engaging character.

He's Infected, so he is by fated doomed to a life of poverty and anonymity despite his musical genius. But with just pure excellence and a small amount of targeted ass-kissing he manages to claw himself into position as one of Leithanien's greatest composers and musicians.

He is actively dying. He's throwing his farewell consert in all haste because he knows that if he waits he will be too sick to do so. Oripathy is merciless. Czerny might live on then for another decade, but won't be able to perform, and for a man that lives and breathes music, his life would be over.

He is... A character. He is unfailingly rude when he can get away with it, critiques easily but accurately and is only diplomatic as absolutely needed. But he is never cruel and never unfair in his critique. And it is obvious that he lives for music alone and is willing to overlook anything for its sake.

He is also deeply, deeply angry at his fate, that every noble still looks down on him despite his excellence and the fact that his infection will rob him of a long and succesful life as a master composer. He is so angry that he's boiling inside.

But he hides it very well.

Until you put him on the battlefield. As a musical maestro one might think that Czerny would be all lyrical, talking about the musicality of war or lamenting its cruelty. But no

On the battlefield, away from all need to fake politeness, Czerny goes full angry German shouting.

And it's great.

He is also, and there's no other way to really put this, a big damn hero.

When he was told that his band twinks were infested by the power and mind of the Witch King, my man did not hesitate at all to match his musical genius against that of the greatest Caster, Musician and Tyrant that has ever lived.

He listened to the Witch King's music, which almost killed him. He then went home, sat at his piano, put down a bucket to catch the blood and spent the entire night matching his musical skill to the Witch King's, composing a counter-score to foil His' plans and try to pull His influence from the two boys and into Czerny himself. My man was completely ready to sacrifice his own life to save the two boys.

And then having not slept at all and fought the Witch King music-to-music the entire night and coughed up about twice his body-weight in blood, Czerny goes "Yeah, I'm ready to play a concert now" because that's just how concert hall pianists are.

And then he takes to the battlefield dressed to the nines and wielding what looks like some demented one-man orchestra Frankencreation to accompany his angry German shouting.

He's just so great.

686 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the last photograph ever taken of Liszt. Here is the story behind the picture…

In July 1886 Franz Liszt visited the Munkácsy's home in Paris on his return from his last visit to England, where he had been fêted by the country's musical establishment, the general public, and even Queen Victoria (Queen Victoria and Liszt had last met over 40 years earlier during the unveiling of the Beethoven Statue in Bonn in 1845, at the height of 'Lisztomania'). Munkácsy's wife, Cécile, had accompanied Liszt on his England visit. Liszt then accepted an invitation to visit the Munkácsys' chateau at Colpach, Luxemburg and rest after all the musical activity in London and Paris. On the last day of his stay in Colpach, 19 July 1886, a photograph was taken of everyone as they left the church, with Cécile Munkácsy on Liszt's arm (Liszt's pupil and secretary Bernhard Stavenhagen can be seen behind, as can Cécile's dog, a Brussels Griffon). Liszt by now had extremely poor vision and was anxiously awaiting cataract surgery, scheduled for September 1886. At the end of his Colpach visit Liszt had caught a bad cold, and then endured a freezing cold train ride on his way to his next port of call, Bayreuth (a travelling companion insisting on keeping the carriage window open the whole journey). Liszt had promised his daughter Cosima (widow of Richard Wagner) that he had would spend time at Bayreuth during the Wagner Festival she was organising. Liszt, even at this grand old age, was without a permanent home, spending most of each year in three different locations: Rome, Weimar and Budapest (Liszt called this his "vie trifurquée" or threefold life, travelling around 4000 miles every year!).

Unfortunately the cold that he had caught at the Munkácsy's in Colpach quickly developed into pneumonia at Bayreuth. Relations with his daughter Cosima were strained, to say the least, and Bayreuth was the worst possible place to be ill, without adequate medical care, and living in a less than salubrious guest house across the street from his daughter's huge mansion. Liszt's final days were spent in great suffering as his condition deteriorated rapidly. He died on 31 July 1886 and was buried (against his wishes, according to some) in Bayreuth, where his tomb remains today, despite repeated attempts to have his remains transferred to Weimar or Budapest. Liszt's funeral, taking place amid the Wagner Festival, became a great excuse to promote Wagner's music and, not for the first or last time, Liszt's own great contribution to the musical world, was totally overshadowed.

#Ferenc Liszt#Franz Liszt#composer#pianist#teacher#Romantic era#romantic period#Romanticism#symphonic poem#New German School

5 notes

·

View notes