#Epirote

Text

Tattoo girl masturbation

Tara Ashley rides hunk guys huge cock

Candid bbw white woman in tight jeans

This chastity device will stop you from jerking off permanently

Hot interracial amateur couple cum on belly

Eu dando aquela chupada e punhetando gostoso

Hairy granny tribbing cute teen

Bombshell brunette Gia Paige rubs her wet pussy

Gamer dude gets the best deep throat blowjob with hardcore cumshot

Bigtits brunette Crystal Rush anal fucked

#Naamana#ectiris#Nealey#beholds#Epirote#nonarticulately#exemptions#overaccelerating#cosmicality#chieftainries#nontribally#Diatoma#circumsphere#Jurdi#progressionism#Post-hittite#subchancel#Wellman#macabre#counterplay

0 notes

Text

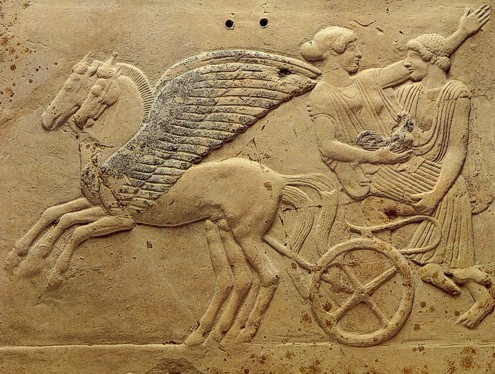

Locri, Calabria, Italy

Locri Epizefiri (Greek Λοκροί Ἐπιζεφύριοι; from the plural of Λοκρός, Lokros, "a Locrian" and ἐπί epi, "on", Ζέφυρος (Zephyros), West Wind, thus "The Western Locrians") was founded about 680 BC on the Italian shore of the Ionian Sea, near modern Capo Zefirio, in Southern Italy's Calabria, by the Locrians, apparently by Opuntii (East Locrians) from the city of Opus, but including Ozolae (West Locrians) and Lacedaemonians.

Due to fierce winds at an original settlement, the settlers moved to the present site. After a century, a defensive wall was built. Outside the city there are several necropoleis, some of which are very large.

Locris was the site of two great sanctuaries, that of Persephone and of Aphrodite. Perhaps uniquely, Persephone was worshiped as protector of marriage and childbirth, a role usually assumed by Hera, and Diodorus Siculus knew the temple there as the most illustrious in Italy.

In the early centuries Locris was allied with Sparta, and later with Syracuse. It founded two colonies of its own, Hipponion and Medma.

During the 5th century BC, votive pinakes in terracotta were often dedicated as offerings to the goddess, made in series and painted with bright colors, animated by scenes connected to the myth of Persephone. Many of these pinakes are now on display in the National Museum of Magna Græcia in Reggio Calabria. Locrian pinakes represent one of the most significant categories of objects from Magna Graecia, both as documents of religious practice and as works of art. In the iconography of votive plaques at Locri, her abduction and marriage to Hades served as an emblem of the marital state, children at Locri were dedicated to Persephone, and maidens about to be wed brought their peplos to be blessed.

During the Pyrrhic Wars (280-275 BC) fought between Pyrrhus of Epirus and Rome, Locris accepted a Roman garrison and fought against the Epirote king. However, the city changed sides numerous times during the war. Bronze tablets from the treasury of its Olympeum, a temple to Zeus, record payments to a 'king', generally thought to be Pyrrhus. Despite this, Pyrrhus plundered the temple of Persephone at Locris before his return to Epirus, an event which would live on in the memory of the Greeks of Italy. At the end of the war, perhaps to allay fears about its loyalty, Locris minted coins depicting a seated Rome being crowned by 'Pistis', a goddess personifying good faith and loyalty, and returned to the Roman fold.

The city was abandoned in the 5th century AD. The town was finally destroyed by the Saracens in 915. The survivors fled inland about 10 kilometres (6 mi) to the town Gerace on the slopes of the Aspromonte.

Today, the modern town of Locri boasts a National Museum and an Archaeological Park, etirely dedicated to the ancient Greek city. The museum preserves the most important findings of the time, such as vases, pinakes, tools used in everyday life, architectural remains from the various excavation area.

Follow us on Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#locri#calabria#italy#italia#south italy#southern italy#mediterranean#mediterranean sea#magna graecia#magna grecia#archaeology#archeology#ancient#art#ancient art#history#ancient history#greek#greek art#ancient greece#landscape#italian#italian landscape#landscapes#europe#persephone#olive trees#olive tree#nature#nature photography

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

In light of Marina Satti being chosen to represent Greece in Eurovision in 2024, maybe a less known fact about her is that the art / polyphonic folk music group Chóres is her creation, she is their founder and creative director.

Satti has also formed a polyphonic a capella band named Fonés, in which she is a performing member, aside from her solo career.

Satti has received distinguished education in music with a scholarship from Berklee College of Music in USA.

The video above is an ethnic song created from traditional Epirote verses, performed by Chóres.

#greece#europe#eurovision#esc#esc 2024#marina satti#music#songs#greek music#greek songs#folk song#greek culture#greek people#greeks#people#greek facts#Youtube

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi theitsa! Following up on your different islands in Greece ask - my cousin just started dating a guy from Kerkyra/Corfu and our yiayia in Athens was like. Spitting into the sea in despair (normal behaviour tbh) because they’re “definitely” Italian pirates(?) and don’t observe Lent, although she says this about p much everyone she doesn’t like. I’ve never visited and know almost nothing about it - do you have any hot takes on Corfu and if the people are actually Italian pirates

My Macedonian ass reading this

I had minimum contact with Corfu and know little about it, so I had to do some extra research..

Kerkyra has been under Enetian/Venetian occupation for quite some time and has many Enetian and Catholic influences, however, this doesn't make Kerkyreans Catholics. The Catholics on the island are only 5% at this point, and Catholics were never the majority. The Orthodoxes of Kerkyra celebrate everything according to the Orthodox calendar and they wish each other Καλή Σαρακοστή online and write articles about it, so they officially observe it. Now if the individuals observe it, that's another thing, and this also goes for Athenians ;)

Kerkyra's population is mainly Greek. Unless a Kerkyrean identifies as Italian because their family is Italian, they are not Italian 😂 But hey, for some Greeks Epirotes are "Albanians" and Macedonians are "Bulgarians" and Thracians/Pontians/Anatolians are "Turks" and Kerkyreans are "Italians"😂 (New ethnic slur dropped, "Italian"!!)

As for the pirate comment, yes, there were Kerkyrean pirates and corsairs but this was... centuries ago?? Like, AT LEAST two centuries ago. Hooow is this relevant?? 😂

Anyway, there's a 99,9999% chance your cousin's bf is NOT a Catholic Italian pirate who doesn't observe Lent. My deepest commiserations.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

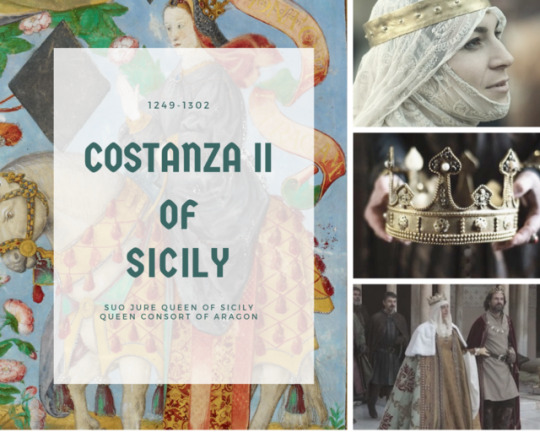

"I am Manfredi, grandson to the Queen

Costanza: whence I pray thee, when return'd,

To my fair daughter go, the parent glad

Of Aragonia and Sicilia's pride;

And of the truth inform her, if of me

Aught else be told. [...]

Look therefore if thou canst advance my bliss;

Revealing to my good Costanza, how

Thou hast beheld me, and beside the terms

Laid on me of that interdict; for here

By means of those below much profit comes.

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Purgatory, III, 112-117 & 141-145

Costanza was born around 1249 to Manfredi of Sicily and his first wife Beatrice of Savoy ("et filiam suam Constantiam, quam ex prima consorte sua Beatrice filiam quondam A. Comitis Sabaudiae"). The exact date is unknown, but historian Saba Malaspina attests that when she was born, her grandfather was still alive (“imperatore vivente"). As for the place, it might have been one of the Apulian castles where the Emperor settled down in the last period of his life.

Her wet nurse was Bella d’Amico, mother of admiral Roger of Lauria. Bella, while she was alive, never parted from Costanza, acting like a mother and confidante, especially since Beatrice of Savoy, Manfredi’s first wife, had died when her daughter was just months old.

Nothing is known about Costanza’s childhood. She’s first mentioned when Berthold von Hohenburg asked for her hand on behalf of his nephew Januarius, son of his brother Diepold VIII. Berthold had married Isotta Lancia, cousin of Manfredi’s mother Bianca, and certainly intended to deepen his relationship with the Hohenstaufen’s family. Manfredi, on the other hand, was strenghtening his position (to the point he would be crowned on August 1258 King of Sicily, despite the true heir, his nephew Corradino was still very much alive, although far away in Germany) and so he could afford to reject this marriage proposal.

From a princess of low importance (despite the pretentious name which honored her great-grandmother Costanza I), Costanza soon became a valuable asset and, until Manfredi’s second marriage to Epirote princess Elena Angelina Doukaina, her father’s heir. The Sicilian King then started looking for an important match for his daughter, and ended up selecting Peter, son of Aragonese King James I.

Marriage agreements required that Manfredi supplied his daughter of a dowry of 50000 golden ounces (worth in gold, silver and jewels). On the other hand, the Aragonese crown committed to return the dowry to her family if Costanza were to die without heirs. She would also act as regent for her children (until they were 20 years old) in case Peter were to die before her. In addition, the Sicilian princess was given personal ownership of the city of Girona and the castle of Cotlliure.

Still, the future union presented some problems. First of all, that 50000 golden ounces dowry was indeed a large amount. Manfredi had an hard time collecting it (he had to increase taxes and that spread discontent among the population) and a lot of time passed before the Aragonese crown could collect it (alongside with the bride). The Papacy was obviously against this marriage, and Urban IV asked James I to give up to this union to avoid disgracing his House. Furthermore, in order to save the plans of the future marriage between his daughter Isabella and the heir to the French throne, James had to promise King Louis IX to not support Manfredi in his fight against the Papacy, as well as not helping Provençal rebel Bonifaci VI de Castellana against Charles of Anjou (the King’s younger brother).

Despite all the external pressure, James didn’t give up to the Sicilian match and on July 13th 1262, Peter and Costanza got married in the church of Notre-Dame des Tables (Montpellier). The difference between the lavish Hohenstaufen court and the more simple Aragonese one was huge (“And the said King Manfred lived more magnificently that any lord in the world, and with greater doings, and with greater expenditure”), but thanks to the accounting records of the time, we know that James and Peter tried their best to meet Costanza’s need, purchasing large amounts of luxury items. Since the incomes deriving from Girona and Cotlliure weren’t enough, she was given an annual pension worthy of 30000 Real de Valencia (a type of billon coin) which also soon wasn’t enough to cover the expenses.

Following the death of Manfredi in the Battle of Tagliacozzo (1266) against Charles of Anjou, many of his former supporters (or simply people linked to him, like the former Nicaean Empress as well as his sister Costanza) fled the Kingdom of Sicily and took refuge in Aragon. The death of Corradino (executed in Naples in 1268 by order of Charles after the Battle of Benevento) and the fact that Manfredi’s sons from Helena Doukaina were just children and in French hands (they will die in captivity years later), made Costanza the only legitimate heir to the Sicilian crown. Starting this moment Costanza started being referred as queen (not infanta or madama) in the documents of the Aragonese Chancellery.

In 1276 James I died, and so Peter was crowned king of Aragon. In the meantime, Costanza had already given birth in 1265 (November 4th) to the firstborn and heir, Alfonso. Followed by another male, James (April 10th 1267), and then Isabella, future Queen consort of Portugal (1271), Frederick (December 13th 1272), Yolanda (1273) and finally Peter (1275). According to historian Muntaner, although it wasn’t a love marriage, Peter and Costanza came to care for each a lot and “there were never was so great love between husband and wife as there was between them, and always had been”.

On Easter 1282, Sicilians started their revolt against the French rule, starting the so called Sicilian Vespers. Peter was quick to reclaim the crown of Sicily and Apulia on behalf of his wife. To the eyes of many Sicilian nobles the King of Aragon could be considered their legitimated master due his marriage to Queen Costanza (”nostre natural senyor, per raho de la regina e de sos fills” ). Before leaving headed for Africa (from where he would launch his invasion of Sicily), Peter named Costanza and their son Alfonso regents of the Kingdom of Aragon during his absence. As soon as he took possession of the island, Peter asked his wife and their children James, Frederick and Yolanda to join him. When the Queen arrived in Trapani in the spring of 1283, she received a warm welcome and was saluted by the people as their natural leader (”cela qui era lur dona natural”; Bernat Desclot, Llibre del rei en Pere d'Aragó e dels seus antecessors passats, ch. 103).

It is around this period that her strained relationship with lady-in-waiting and de facto second lady of the Island, Macalda di Scaletta (wife of Alaimo da Lentini, Grand Justiciar of the Kingdom of Sicily), was born. Macalda, who is described by historical sources as an ambitious and greedy woman, had tried to seduce Peter of Aragon, but without success. Since the King had declared himself devoted to his wife, the Sicilian baroness developed a burning hate towards her rival, the Queen.

In Messina, Costanza could finally embrance her husband again, but their meeting only lasted three days and it was their last. The King named his wife Regent of the Kingdom of Sicily (“Quant lo rey hac estat ab sa muller e ab sos infants en la ciutat de Mecina, e hac stablit sos balles e sos vicaris per tota Cecilia, si los feu comandament que tots fessen lo manament de la reyna e de son fill En Jaume, axi com perell, e comana la reyna als homens de Cecilia e de Mecina, e sos fills”) and returned to Aragon as his rival, Charles of Anjou, had proposed a trial by combat (who would never take take place) to be ideally fought in Bordeaux to decide the fate of the contended Kingdom. Peter died two years later in Villafranca del Penedès (Catalonia), on November 11th 1285.

Before leaving Sicily, Peter had declared that the Kingdom wouldn’t be merged into the Aragonese-Catalan territories, mantaining his autonomy, and that in thet future the succession of the two reigns would be handled separately, specifically with the Sicilian throne bequeated to the second son (at that time, James, already named Lieutenant of the Realm).

With Peter dead, Costanza didn’t choose to rule over Sicily by herself despite being its titular queen, but, as it had already been decided, relinquished her rights to her second son James (although she would keep managing the island on his behalf), while Alfonso succeeded his father. In accord to the pre-nuptial arrangements, the Dowager Queen supported her teen son in the matter of ruling the Kingdoms he had inherited.

In 1284, Costanza’s milk brother, Roger of Lauria carried out a successful expedition in the Gulf of Naples. The admiral captured Charles of Salerno, the Angevin heir, and took him in Messina, where he was saved by the angry mob thanks to the intervention of the Dowager Queen. During the same raid, Lauria had freed Princess Beatrice of Hohenstaufen, Costanza’s younger half-sister. The Queen soon put her unfortunate sister under her protection, arranging Beatrice’s marriage with Costanza’s half-nephew, Manfredo IV Marquis of Saluzzo. The wedding was celebrated in October 1286 in Messina, and during the celebration the Princess had to give up on her rights to the Sicilian throne.

In 1290 she deployed troops to defend the city of Acre, but given the excommunication of Pope Martin IV against Peter III of Aragon and the Sicilian people, those troops were sent back. The following year, 1291, Acre would be conquered by Mamluk forces.

Also that year, Alfonso III died heirless. James succeeded him as King of Aragon, Valencia and Majorca, Count of Roussillon, Cerdanya and Barcelona, and, in normal circumstances, his brother Frederick would have inherited the Sicilian Crown, but James had other ideas. The new King kept Sicily for himself, naming Frederick Lieutenant of the Realm. The dispossessed Prince then left the Kingdom headed to Sicily, where he joined his mother Costanza.

Her son’s death represented a turning point in her life. Although already a pious woman, she started pondering about a future in the cloister and retired in a Clarisse nunnery she had personally founded in Messina.

In 1295, James signed the Treaty of Anagni, an accord signed by Boniface VIII, James II of Aragon, James II of Majorca, Charles II of Anjou and Philip IV of France, which should have put to an end to the Vespers War. As part of the terms, the King of Aragon had to return the island of Sicily to the Pope (let’s remember the fact that officially, since Norman times, the Kingdom of Sicily was actually one of the Papacy’s many fiefs, and that its lords were just lieutenants), who would in turn give it to Charles of Anjou, in exchange for the annulment of the excommunication weighing over him and the concession of the licentia invadendi (the permission to invade) concerning the islands of Sardinia and Corsica. The treaty required moreover a double dinastic union, James would have married Princess Blanche of Anjou, while her brother Robert was wed to James’ sister Yolanda.

There was someone in particular, though, who wasn’t happy about this settlements. Backed up by the Sicilian population who refused to return under French domination, Infante Frederick was crowned King of Sicily in Palermo on March 25th 1296, de facto nullifyng any attempt to stop the war.

This had a huge impact in his mother’s life. Unlike her son, Costanza had always recognized the Papal authority. By not accepting the treaty’s terms, Frederick had in fact rebelled against the Pope (not mentioning his own brother). Costanza chose then not to support him and, because of this, she had to leave Sicily since, as Papal emissaries put it, if she stayed she could be considered an accomplice (“E madona la regina Costança fo absolta per lo Papa, é tots aquells qui eren de sa companyia , si que tots dies oya missa; que axi ho hach a fer lo Papa, per convinença a les paus quel senyor rey Darago feu ab ell. Per que madona la regina parti de Sicilia ab deu galees , e anassen en Roma per pelegrinatge” in Crónica de Ramon Muntaner, ch CLXXXV).

Together with her longtime supporters, Giovanni da Procida and Roger of Lauria, in february 1297, she traveled to Rome where the Pope had promised to economically support her staying in Rome (although apparently it was a short-lived promise) and where she witnessed her daughter Yolanda’s marriage to Robert of Anjou. In 1299 the Dowager Queen returned to Catalonia and died in Barcelona on April 8th 1302 (“Non sine cordis amaritudine vobis presentibus intimamus quod die Veneris Sancta, quasi in media nocte, serenissima et karissima domina et mater nostra domina Constancia, fidelis recordacionis Aragonum regina, diem clausit extremum, ex quo tanto nos pungit doloris ictus acerbus quanto per eius obitum sentimus nos tante matris solacio destitutos.” in La muerte en la Casa Real de Aragón..., p.20).

Aside from many donations to various religious houses, in her will (dated february 1st 1299) Queen Costanza would include a small bequest in favor of her son Frederick with the condition he had to make peace with the Pope, observing thus the terms of the Treaty of Anagni.

She was buried wearing the Franciscan habit in the convent of St. Francis in Barcelona (“E a Barcelona ella fina , e lexas a la casa dels frares menors, ab son fill lo rey Nanfos, e muri menoreta vestida ” Crónica de Ramon Muntaner, ch CLXXXV). In 1852 her remains would be moved to Barcelona Cathedral by order of Queen Isabella II of Spain.

Sources

Claramunt Rodríguez Salvador, Alfonso III de Aragón

Corrao Pietro, PIETRO I di Sicilia, III d'Aragona in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 83

Desclot Bernat, Crónica

Ferrer Mallol María Teresa, Constanza de Sicilia

Hinojosa Montalvo José, Jaime II

La Mantia Giuseppe, FEDERICO II d'Aragona, re di Sicilia in Enciclopedia Italiana

La muerte en la Casa Real de Aragón Cartas de condolencia y anunciadoras de fallecimientos (siglos XIII al XVI), ARCHIVO DE LA CORONA DE ARAGÓN

Malaspina Saba, Rerum Sicularum

Muntaner Ramon, Crónica / translation by Lady Goodenough

Sicily/Naples: Counts & Kings

Walter Ingeborg, COSTANZA di Svevia, regina d'Aragona e di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 30

#historicwomendaily#history#women#history of women#historical women#costanza ii#House of Hohenstaufen#house of aragon and sicily#peter iii of aragon#norman swabian sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#vespri siciliani#myedit#historyedit

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

Kind of related to the ask on Cleopatra, and even your one way earlier on Krateros… What do you think Alexander would’ve been like if he weren’t an Argead, and instead fated to be a Marshal for whoever else was meant for the throne? Do you think he would’ve been rebellious? Or cutthroat and ambitious like Krateros? Or more-so disciplined and loyal? I kind of see him as a combination of all three because I don’t peg Alexander for someone who can be contained, lol.

To answer this, we must keep in mind that, for the ancient Greeks, belief in divine parentage for certain family lines was very real. A given family and/or person ruled due to their descent. The heroes in Homer had divine parents/grandparents/great-grandparents. This notion continued into the Archaic period with oligarchic city-states ruled by hoi aristoi: “the best men.” (Yes, our word “aristocrat” comes from that.) Many of these wealthy families claimed divine ancestry; that’s why they were “best.”

In the south, this began to break down from the 5th century into the 4th. But not in Macedonia, Thessaly, or Epiros. In fact, even by Alexander’s day, many Greek poleis remained oligarchies, not democracies. And in democracies, “equality” was reserved for a select group: adult free male citizens. Competition (agonía) was how to prove personal excellence (aretȇ), and thereby gain fame (timȇ) and glory (kléos). All this was still regarded as the favor of the gods.

Alexander believed himself destined for great things because he was raised to believe that, as a result of his birth. Pop history sometimes presents only Olympias as encouraging his “special” status. But Philip also inculcated in Alexander a belief he was unique. He (and Olympias) got Alexander an Epirote prince as a lesson-master, then Aristotle as a personal tutor. Philip made Alexander regent at 16 and general at 18. That’s serious “fast track.” Alexander didn’t earn these promotions in the usual way; he was literally born to them.

If Alexander hadn’t been an Argead, that would have impacted his sense of his place in the world no less than it did because he was an Argead. What he might have reasonably expected his life path to take would have depended heavily on what strata of society he was born into.

Were he a commoner, in the Macedonian military system, his ambitions might have peaked at decadarch/dekadarchos (leader of a file). Higher officer positions were reserved for aristocrats through Philip’s reign. With Alexander himself, after Gaugamela, things started to change for the infantry, at least below the highest levels (but not in the cavalry, as owning a horse itself was an elite marker). Under Philip, skilled infantry might be tagged for the Pezhetairoi (who became the Hypaspists under ATG). But Alexander himself wouldn’t have qualified because those slots weren’t just for the best infantrymen, but the LARGEST ones. (In infantry combat, being large in frame was a distinct advantage.) So as a commoner, Alexander’s options would have been severely limited.

Things would have got more interesting if he’d been born into the ranks of the Hetairoi families, especially if from the Upper Macedonian cantons.

Lower cantons were Macedonian way back. If born into those, he (and his parents) would have been jockeying for a position as syntrophos (companion) of a prince. Then, he’d try to impress that prince and gain a position as close to him as possible, which could result in becoming a taxiarch/taxiarchos or ilarch/ilarchos in the infantry or cavalry. But he’d better pick the RIGHT prince, as if his wound up failing to secure the kingship, he might die, or at least fall under heavy suspicion that could permanently curtain real advancement.

That was the usual expectation for Lower Macedonian elites. Place as a Hetairos of the king and, if proven worthy in combat, relatively high military command. Yes, like Krateros. But hot-headedness could curtail advancement, as apparently happened to Meleagros, who started out well but never advanced far. The higher one rose, the more one became a potential target: witness Philotas, and later Perdikkas. In contrast, Hephaistion was Teflon (until his death). Yet Hephaistion’s status rested entirely on his importance to Alexander. And he probably wasn’t Macedonian anyway; nor was Perdikkas from Lower Macedonia, for that matter.

The northern cantons were semi-independent to fully autonomous earlier in Macedonian history. Their rulers also wore the title “basileus” (king); we just tend to translate it as “prince” to acknowledge they became subservient to Pella/Aigai. Philip incorporated them early in his reign, and I think there’s a tendency to overlook lingering resentment (and rebellion) even in Philip’s latter years. Philip’s mother was from Lynkestis, and his first wife (Phila) from Elimeia. Those marriages (his father’s and his) were political, not love matches.

Similarly, Oretis was independent, and originally more connected to Epiros. Note that Perdikkas, son of Orontes, was commanding entire battalions when he, too, was comparatively young. Like Alexander, he was “born” to it. Carol King has a very interesting chapter on him in the upcoming collection I’m editing, one that makes several excellent points about how later Successors really did a number on Perdikkas’s reputation (and not just Ptolemy).

If Alexander had been born into one of these royal families from the upper cantons, quasi-rebellious attitudes might be more likely. Much would depend on how he wanted to position himself. Harpalos, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Ptolemy…all were from upper or at least middle cantons. They faired well. For that matter, Parmenion himself may have been from an upper canton and decided to throw in his hat with Philip.

By Philip’s day, trying to be independent of Pella was not a wise political choice, but if one came from a royal family previously independent, we can see why that might be seductive. Lower Macedonia had always been the larger/stronger kingdom. But prior to Philip, Lynkestis and Elimeia both had histories of conflict with Macedonia, and of supporting alternate claimants for the Macedonian throne. At one point in (I think?) the Peloponnesian War, Elimeia was singled out as having the best cavalry in the north. Aiani, the main capital, had long ties WEST to Corinthian trade (and Epirote ports). It was a powerful kingdom in the Archaic/early Classical era, after which, it faded.

So, these places had proud histories. If Alexander had been born in Aiani, would he have been willing to submit to Philip’s heir? Maybe not. But realistically, could he have resisted? That’s more dubious. By then, Elimeia just didn’t have the resources in men and finances.

I hope this gives some insight into how much one’s social rank influenced how one learned to think about one’s self. Also, it gives some insight into political factions in Macedonia itself. As noted, I believe we fail to recognize just how much influence Philip had in uniting Lower and Upper Macedonia. Nor how resentment may have lingered for decades. I play with this in Dancing with the Lion: Rise, as I do think it had an impact on Philip’s assassination.

(Spoiler!)

Philips discussion with his son in the Rise, and his “counter-plot” (that goes awry) may be my own invention, but it’s based in what I believe were very real lingering resentments, 20+ years into Philip’s rule.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander alternate history#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedonian politics#Upper Macedonia#Lower Macedonia#Macedonian internal politics#Philip II of Macedon#ancient history#Classics

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Quilted Flowers: 1940s Albanian & Epirot Recordings from the Balkan Label LP Limited Edition

Ajdin Asllan was born in Leskovik near the present-day southern border of Albania on March 12, 1895. At the age of 30, on July 12, 1925, he married a girl named Emverije, who was one month shy of her 16th birthday, in her native town Korçë, about 80 miles north. He arrived in New York by himself less than a year later on September 20, 1926, and when he filed his Declaration of Intent to become an American citizen in 1928 as a resident of Detroit, he gave his occupation as "musician." Emverije joined him in New York City on July 27, 1931.

Asllan appears to have made his first recordings in November 1931 as a clarinetist on four songs issued as 12” discs by Columbia sung in Albanian by K. Duro N. Gerati. In January 1932 he recorded again, this time singing and playing oud on three Columbia 12”s along with several Albanian singers and the violinist Nicola Doneff (born March 21, 1891 Dichin, Bulgaria; died July 19, 1961 New York). In 30s Asllan launched an independent label called Mi-Re (roughly “With New” in Albanian) Rekord primarily to release his own recordings, but it stalled out after about 6 releases. In October 1941 he accompanied a Greek singer and songwriter named G.K. Xenopoulos as an oudist along with the beloved Greek clarinetist Kostas Gadinis and accordionist John Gianaros for the Orthophonic subsidiary of Victor Records run by Tetos Demetriades. The trio of Gadinis, Asllan, and Gianaros cut another four sides for Orthophonic May 1, 1942. Shortly thereafter, Asllan relaunched his label as Me Re with the help of Doneff and then quickly renamed it, more generically, Balkan. Gianaros came in as a business partner, and Balkan released scores of records, some of them seemingly selling thousands of copies in the mid-40s, but Gianaros split angrily with Asllan after just a few years over money problems.

By 1947, Doneff had trademarked the Kaliphon label, which drew from much of the same roster of New York musicians of the Greek- and Turkish-speaking performers as Balkan and apparently collaborated in distribution, marketing, and manufacturing into the 1950s, but some business distinction had been drawn. A third label, Metropolitan, was launched and became at catchall for further Greek, Turkish, Armenian, and Ladino material by New York players, but it's not clear who was in charge or how things were divided up. Maybe Metropolitan was started by Asllan as a separate business to dodge the taxman or old creditors? We don’t know. All three labels shared a standard black-on-red color scheme that, it would seem reasonable to guess, was based on the Albanian flag and Asslan’s original, core purpose as an artist and impresario.

Adjin and Emverije lived during the 1930s into the 50s first at 143 Norfolk St. and then at 42 Rivington St. (where Asllan opened a record shop), in Manhattan's Lower East Side, where Eastern European Jewish immigrants surrounded the small Albanian community and Turkish-speaking Sephardic Jews, and abutting Little Italy and a strip of Greek coffee houses on Mulberry Street. He worked within a network of primarily Turkish- and Greek-speaking performers in New York and released recordings prolifically made both locally and overseas through the 40s and 50s. He corresponded with his brother Selim (who sings on track 1, side A, later worked on the radio in Tirana and co-founded the National Ensemble of Folk Songs and Dances) back home, who was able to secure masters of Albanian performers recorded in Istanbul and Athens along with performances by Turkish- and Greek-speaking stars including Rosa Eskenazi and Udi Hrant (both of whom subsequently made extended visits to the U.S.)

Greeks and Armenians had, even at the low ebb of immigration during the 1940s-50s, substantial immigrant populations in New York and around the country - Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, and many other cities. Those markets kept the Balkan label afloat for nearly 20 years. But Asllan also issued about 40 discs for the Albanian-language market ca. 1945-50 (at which point he retained a 500-series numbering scheme for them, picking up where he’d left off with his Me Ri label a decade earlier), including both folk music of southern Albania and choral music, much of the latter anti-Fascist Communist songs. In addition, three discs were issued as part of Balkan’s Greek series of uncredited musicians from Pogoni and Konitsa, towns about 30 miles south as the crow flies from where Asllan was born. The total Albanian-speaking population in the U.S. at the time was less than 10,000, and many couldn’t afford record players. But despite the small market for Albanian-language songs, he made sure to release discs for his countrymen. It was a time of immense political and social turbulence in both Albania and Greece, and the sense of duty to music is palpable in his work.

Balkan’s business model was haphazard. Its numbering system, if one can call it that, indicates a tendency to start a series, then add to it - or not - sporadically, driven largely the question, “can we sell 500 of these? (And if so, can we sell 1000?)” The last Balkan 78s were issued around 1959; a few LP releases appeared around 1960, more than 20 years after Asllan released his first discs. We know he visited his native home and family in 1951, 25 years after having become American. He died in New York in October 1976. He had no children, save the records.

=========

We have so far been able to trace a biographical narrative of only one of the other immigrant performer among those who play on this collection, Chaban Arif, who apparently sings on track 9.

He was born May 22, 1899 in Berat, Albania, attended school through the second grade, and arrived alone at Ellis Island on November 2, 1920 at the age of 19 under the name Aril Shaban. His intention upon arrival was to meet up with a cousin, Mahomet Hajrules (who, in turn, had arrived only six months earlier under the name Mehemet Airula) in Southbridge, Massachusetts. However, there was a family of four from Shaban’s hometown on the same steamship who were headed to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (via a stop first at the south Philadelphia home of a relative), so Shaban wound up in Pittsburgh.

He filed his first papers to become a U.S. citizen in Canton, Ohio in 1925, but he had returned to Albania in June of 1928, where he married an 18 year old woman named Nadire, and by 1931 had returned to Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, where he was working at the Duquesne, Pennsylvania Carnegie steel mill. (When his cousin Mehmet Hajrulla filed his Declaration of Intent to naturalize as a U.S. citizen in 1937, he was a widower living on Braddock Ave. in Pittsburgh and working as a painter.)

The 1940 census found Shaban Arif relocated to 55 Clinton St. on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, about seven blocks from Adjin Asllan’s place on Rivington. Arif told the census enumerator that he worked 60 hours a week, 52 weeks a year for $916 a year (about $17,000 a year in today’s money) at the counter of of a restaurant. The man he listed on his WWII draft registration card as his closest contact was named Kardi Braim, who gave his country of origin either as Albania and Macedonia on different documents, had himself worked for a brick manufacturer in Erie County, Pennsylvania in addition to a string of other laboring jobs and worked at the time at Stewart’s Restaurant. It would seem reasonable to guess that both Shaban Arif and Kardi Braim were in Adjin Asllan’s limited social circle of Albanians in the neighborhood in the early 1940s when he recorded on this song. The $1 that the disc cost could have represented three and a half hours of labor at the restaurant.

We know nothing else of Shaban Arif’s life except that he died in New York City in September, 1971. (Kardi Braim died in 1978.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Epirotes Society of Philadelphia ‘Omonia’ organized 16th Annual ‘Tsipourovradia’

https://travel-tourism.news-24.gr/epirotes-society-of-philadelphia-omonia-organized-16th-annual-tsipourovradia/

0 notes

Text

PAS Ioannina announced striker Claudio Balan

PAS Ioannina announced striker Claudio Balan

PAS Ioannina have announced the signing of Claudio Balan, with the Romanian forward on a two-year contract.

PAS Ioannina have extended their transfer window to look for a striker after Pedro Conte’s injury. Epirotes finally announced the acquisition of Claudio Christian Balan.

The 28-year-old Romanian striker has signed a two-year contract with Epirotes. He was released by Universitatea Craiova…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Hellenistic drachma of the Epirote League, depicting the heads of Dodonian Zeus (crowned with an oak wreath) and Dione (or Hera). Artist unknown; ca. 233-168 BCE. Now in the Staatliche Münzsammlung, Munich. Photo credit: ArchaiOptix/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Hellenistic period#Hellenistic Greece#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Hellenistic art#coins#ancient coins#Greek coins#Ancient Greek coins#numismatics#ancient numismatics#drachma#Epirote League#Staatliche Munzsammlung

171 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which are the most beautiful places in Greece? Aside from mykono and santorini which are beautiful but they are the obvious answer 😉

First, let me tell you what isn’t. Mykonos is generally not among the most beautiful places in Greece. It might come off as a surprise to foreign people but you don’t go to Mykonos because of its beauty. You go for the jet set / celebrity vibes. That’s not to say it isn’t beautiful or that you wouldn’t love it if you went there - it has gorgeous settlements and nice beaches - but compared to other places I wouldn’t even rank it in the top 25, let alone top 2.

Santorini is another case. It’s one of a kind, not only in Greece but worldwide too. But even that can’t guarantee one will definitely like it. For example, my dad can name almost 10 islands he likes more than Santorini, which seems insane to me, but beauty is a very subjective matter.

Which is why I have trouble coming up with an answer for you. There are so many things that make a place beautiful. How can I objectively compare coastal and mountainous regions or beautiful towns or other peculiar attractions (outstanding landscapes or major historical/ cultural regions)? It depends on what everybody prefers. As I’ve said before, Greece’s strong card is that it is more or less everywhere beautiful. You have to make a really odd touristic choice to land on a truly plain place.

The only thing I can do is find the best regarding specific types of beauty. The rankings are in no particular order.

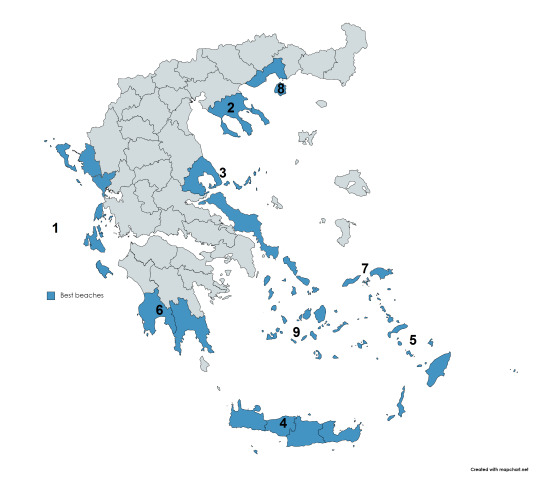

Best beaches and coastal regions:

Mostly found in the Heptanese (Ionian) islands and the Epirote coast opposite them [1], Chalcidice [2], Mount Pelion, the Sporades islands and Euboea island [3], Crete island [4], the Dodecanese islands [5], the South Peloponnese [6], Samos island [7], Thasos island [8] and some of the Cyclades islands (i.e the Small Cyclades) [9].

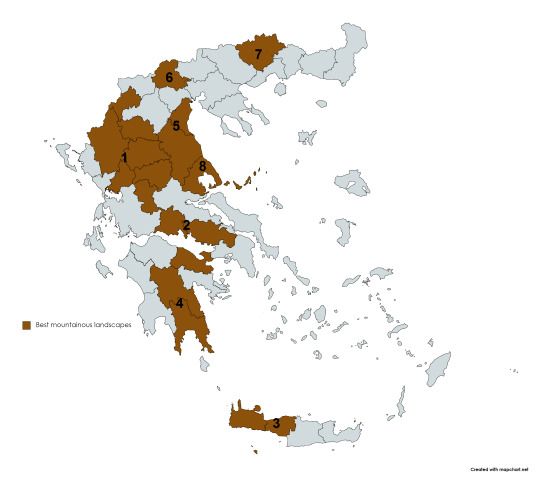

Best mountainous regions:

The Pindus mountain range and Agrafa mountains covering almost all of Epirus, Southwest Macedonia, West Thessaly, Northwest Sterea Hellas [1]. The rest of the mountains of Sterea Hellas [2]. The two mountain ranges of Crete island [3]. The mountainous core of Arcadia in Peloponnese, Feneos in Corinth and Mount Taygetus in Laconia [4]. Mount Olympus where Larissa meets Pieria [5]. Mount Voras in Pella [6] and Mount Falakro in Drama [7]. Mount Pelion in Magnesia [8].

Best forests, wetlands and ecoregions:

The forests in Thrace and East Macedonia [1], Kerkini in Serres, Skra lake in Kilkis and the waterfalls of Edessa [2], the Perspa lakes and the wildlife shelters in Kastoria and Florina [3], the National Woodland parks in Ioannina and Grevena [4], the Marine Park in Alonissos island and the forests in Mount Pelion [5], Plastira Lake in Karditsa [6], the many wetlands of Aetolia-Acarnania [7], the Marine Park of Zakynthos island [8], wetlands and forests in Elis [9], Feneos in Corinthia [10], Gorge of Samaria in Chania [11].

Prettiest towns or most interesting urban centers:

Kavala, Xanthi and the Pomak villages of Thrace [1], Thessaloniki [2], Kastoria, Ioannina, its surrounding Zagorohoria villages and Parga in Preveza [3], Kerkyra (Corfu) island [4], Volos and the traditional villages of Mount Pelion [5], Athens [6], Nafplion, the Saronic islands and the mountain villages of Arcadia [7], Lesvos and Chios islands [8], all the Cyclades islands and Skyros island [9], the Dodecanese islands [10] and Chania town [11].

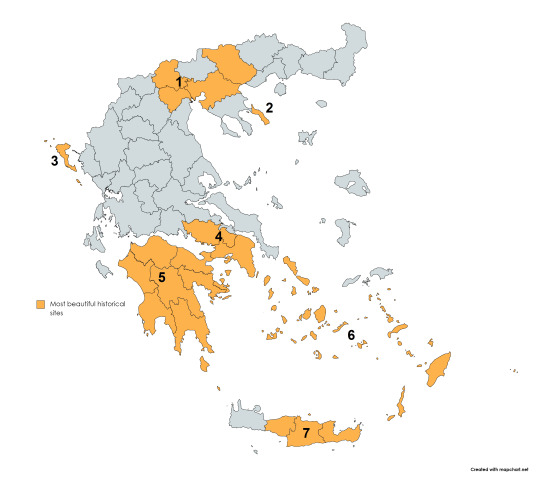

Best historical sites:

Ancient Pella, Vergina in Imathia, Amphipolis in Serres and all monuments and museums in Thessaloniki [1], the Monastic State of Mount Athos [2], Kerkyra (Corfu) island [3], Delphi and all historical sites in Athens [4], basically all of Peloponnese [5], many of the Cyclades islands and the largest of the Dodecanese islands [6] and all archaeological and historical sites in most of Crete [7].

Best unique regions, standalone areas, natural and cultural wonders etc:

Meteora in Trikala is a category on its own [1], Santorini but also other places in Cyclades islands too (i.e Milos) [2], Samothrace [3], Livaditis of Xanthi, the tallest waterfall in the Balkans, in a challenging to access region [4], the autonomous Monastic State of Mount Athos [5], the sand dunes in Lemnos island and the petrified forest in Lesvos island [6], Vikos Gorge in Ioannina [7], Melissani lake in Cephalonia island and the Blue Caves in Zakynthos island [8], Polylimnio in Messenia and Diros caves in Laconia [9], several features in Chania (i.e Balos lagoon, Elafonissi pink beach, Samaria gorge) [10], the Corinth Canal in Corinthia [11] and the Servia gorge and Bouharia in Kozani [12].

Important note: This was an attempt to narrow it down. I excluded dozens of locations with beautiful archaeological museums, ancient theatres, tombs etc. I excluded many areas with pretty mountain villages. I excluded half the good beaches. I have certainly forgotten stuff. For example, I haven't coloured even once a place I really like. But in general I think the result is decent. Not perfect but not that far off either.

194 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm sorry if you've already answered this but I couldn't find the answer anywhere, how do you find sources for foresies?

I'm a Greek immigrant to a country where there isn't a lot of resources about Greece, and I've been trying to find sources of what women from kalamata/koroni/xrisokelaria wore, but I cannot seem to find any!

Hello! Searching about Greek stuff, here and on different sites, I find them accidentally 😅 For many, I stumbled upon on them on Pinterest and queued/scheduled them as posts on the blog.

If one is actively searching, knowledge of the Greek language ane the Greek areas will greatly help. There are only a few results in English for traditional Greek clothing (nobody gives a shit globally about Greeks after 100AD as I often say 😂), so you'll need to Google in Greek.

For the places you mentioned, you can Google:

Παραδοσιακή φορεσιά Καλαμάτας

Παραδοσιακή φορεσιά Κορώνης

Παραδοσιακή φορεσιά Χρυσοκελλαριάς

(If you have googled and didn't find anything, let me know, and I will search about them 💙)

You can of course google area names and translate the text on the spot but learning these two things better will be an advantage for sure. It needs some time, naturally, to learn to distinguish the different Peloponnesian costumes from the Epirote ones, let's say. Sometimes the photo headers on Google Images are misleading, so usually further research is needed (like, going into the page and reading the descriptions, or separately searching more articles on the clothing).

Good luck in your research, and I am here to help more if you need it!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman History in a Nutshell: The Pyrrhic Wars - The Battle of Heraclea, 280 BCE

#Roman #History in a Nutshell: The #Pyrrhic #Wars - The #Battle of #Heraclea, 280 BCE - Covering the lead up to the Pyrrhic Wars, and the first battle. #Ancient #Rome and #Ancient #Greece were now, finally, bumping heads.

A little bit of where we are and a little bit of where we’re going! The Pyrrhic Wars lasted for approximately 5 years and saw the King of Epirus, Pyrrhus, cross the sea to air the Greek city of Tarentum. The first major battle took place at Heraclea (pictured southwest of Tarentum) (Credit: Piom By GDFL)

In order to know where we are with these pesky, war hungry Romans we need to talk about…

View On WordPress

#280 bc#280 bce#Alexander the Great#ancient greece#ancient rome#Appius Claudius Caecus#battle of heraclea#cause of the pyrrhic wars#Epirot#epirus#greece#Greek#hellenic#hellenic world#hellenistic#hellenistic empire#heraclea#historiography#History#laevinus#legion#macedonia#Macedonian Phalanx#Philip II#Philip II of macedon#Publius Valerius Laevinus#pyrrhic#pyrrhus#roman#roman empire

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What were the government systems of Alexander's day? Were most cities still ruled by kings?

The questioner asked about “cities,” but I’m not sure in what area. I’m assuming Greece? But Greece is part of a larger region: the Mediterranean Basin and Ancient Near East. The Ancient Near East in particular had a prior history of interconnectedness from the Middle Bronze Age forward, and certainly by the Late Bronze Age, that included Greece and Egypt (or the Eastern Mediterranean).

So some quick terminology:

A city-state is a large urban center and its dependent villages and rural countryside as an independent political entity.

A nation-state is a geographical area united by a concept of shared ethnicity and political independence.

A state is a geographical area that may include multiple ethnic groups united under a political hegemony.

These can be of varying sizes, although as you can gather, states tend to be much larger than city-states. They can, however, have different government systems. An “empire” is always a state. In fact, Rome invented that term: imperator = emperor. But city-states and even nation-states can have kings or other forms of gov’t.

Government styles vary. All of these are found in the ANE/Med Basin by Alexander’s day:

Priest-kings, dynastic kings, god-kings, subject kings, chieftain-style kingship (rule by clan), councilar-monarchy, mixed-government, oligarchy, tyranny, representative democracy, full democracy

If we look just at Greece, you won’t find the sort of “absolute” monarch that we see in the ANE at the time with subject kings in some areas.

In the southern Greek city-states, the dominant form was a sort of modified oligarchy where an oligarchic council made most decisions, but the assembly of the people still had voting power. Athenian democracy (invented in 510/9 BCE) had spread to various places where it competed with modified oligarchies; it was more popular in Attic-Ionic areas but not exclusive to them: Corinth and Syracuse both had democracies when they didn’t have a tyrant (Syracuse). Also, we have “leagues,” but these are made up of independent city-states (or later kingdoms, namely Macedon) and form for a given reason. They don’t constitute a form of ruling government in themselves.

Sparta had its own wacky “mixed” system that still included 2 kings, but also had a democratic arm (ephors) and oligarchic arm (gerousia). It’s pretty much unique to Sparta. Doric areas and especially Aeolic were more likely to be modified oligarchies, but as noted, that’s not a given. Then you get to the north and find the increasingly monarchal systems from Thessaly to Epiros to Macedon. Thessaly had 4 powerful clans who competed for power and tyranny (I think really ought to be called ‘princes’ not tyrants) and eventually co-ruled as a tetrarchy imposed by Philip. Epiros had a king, but that king answered to a council, and again you have ruling families.

Macedon, both lower and Upper (prior to Philip) had chieftain kingships, or rule-by-clan. This same form, even looser, was found north of them in Illyria, Paionia, and Thrace. Various clans had kings, who occasionally managed to create a hegemony over other clans due to a particular king’s charisma. Incidentally, the early Medes and Persians seem to have had a similar form.

It’s rare that a figure with enough charisma emerged, but we do get them: Cyrus I and Philip, most obviously—but also Bardylis I (of Illyria) and Sitalkes I (of Odrysian Thrace). In the latter two cases, however, the areas were briefly united, then fell apart again, either right after or after a few sons. Although really, we could say that of Macedon. Philip united the region, forced in several previously independent norther Macedonian kingdoms (Elimeia and Lynkestis, especially), stole one or two from Epiros (Orestis in particular), then gobbled up a bunch of Greek cities east. Alexander ran away with the toy…and that dynasty died.

Of all 4 of those charismatic uniters, only Cyrus’s kingdom lasted. And it lasted because Darius I stepped in and fixed it. Otherwise, it would have collapsed not unlike Bardylis’s Illyrian dynasty. While Darius claimed a family connection, most modern historians recognize it as strained at best, and possibly entirely made up. Why Persia may have succeeded where the other 3 fell apart is because Cyrus stepped into a looooong tradition of monarchal rule present in the ANE back into the Bronze Age. Cyrus, and especially Darius built the Achaemenid Persian Empire on the shoulders of the Babylonian, Assyrian, etc. before. We could even say that’s what Alexander was trying to do himself. But it got too big and collapsed.

I hope that helps explain the systems. I didn’t touch the west, but it had some unique systems of it’s own, such as the Etruscan Council of 12 Cities, which was a governing council, but within the cities, they were ruled by kings. We don’t know a lot about Carthage because Rome trashed a lot of their internal records; Aristotle did include them in his Politics.

#asks#ancient politics#city-state#ancient Greek political structures#Greek democracy#ANE politics#chieftain-level kingship#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#Greek political history#Athenian democracy#Spartan mixed-government#Etruscan government#Persian empire#Thessalian government#Epirote government#Greek oligarchy#Classics#Tagamemnon

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animals in Hellenic Languages

Dog

Σκύλαξ - Ancient Greek

Σκύλος - Modern Greek

Φιντέλης/Γουγούμης/Λυσσαγμάν - Kaliarda

Sciddho - Italiot

Sciddo/Sciḍḍo - Calabrian Griko

Κουλούκι - Cretan

Στσούλε - Maniot

Κούε - Tsakonian

Στσ̌ουλί/Σουλί - Old Athenian

Σκλι - Epirote

Şkli/Şkila - Patriot

Σκυλί - Naoussian

Σκλί/Ζαγάρι - Sarakatsani

Στσ̌ούλε/Στσύλε - Propontic Tsakonian

Σκλί/Στσλί - Tenediot

Σκύλος - Smyrniot

Σκούντους - Silliot

Σ̌κυλί - Cappadocian

Σ̌κυλί - Mistiot Cappadocian

Στσυλί - Delmesiot Cappadocian

Σκυλί - Pharasiot

Σ̌κύλον - Pontic

Şkilos - Romeyka

Шклы/Щилы - Mariupolitan

Σ̌ύλλος - Cypriot

Κήλπ/Κλεπ - Cypriot Arabic

Κιοπέκ̇ - Karamanlidika

Κιέν - Arvanite

Κάνε/ζαγάρου/χάρτα/λιγόνου - Aromanian

Τζιουκέλ/Τζουκέλ - Romani

Cat

Κατά - Ancient Greek

Γάτα - Modern Greek

Αδελφούλα - Kaliarda

Mùsci- Italiot

Κάτης - Cretan

Κατζούα - Tsakonian

Γάτα - Naoussian

Ğatus/Ğata - Patriot

Κάτα - Trigliot Bithynian

Κάτ̔ης - Lycian

Πισίκα - Cappadocian

Πσίκα - Axenitic Cappadocian

Πισίκα - Limniot Cappadocian

Π̔ισίκα - Mistiot Cappadocian

Κατά - Pontic

Kata - Romeyka

Ката - Mariupolitan

Κάττα - Cypriot

Καττ/Χτατ - Cypriot Arabic

Πισίκ̇/Κετ̇ί - Karamanlidika

Μάτσ̈ε̱ - Arvanite

Κατούσα/Μάτσα/Πίσα - Aromanian

Μᾱ́τσα/Μάτσ̇α - Romani

Mouse

Μῦς/Ποντικός- Ancient Greek

Μυῶν - Epic Greek

Ποντίκι - Modern Greek

Αδερφοτροφή - Kaliarda

Pondikò - Italiot

Κουφό/ Ποντικό - Maniot

Αρπετέ - Tsakonian

Πεντικός - Old Athenian

Pundik - Patriot

Ποντζικός - Silliot

Ποντικός - Cappadocian

Ποντζικός - Delmesiot & Aravaniot Cappadocian

Πινντικός - Mistiot Cappadocian

Πιντικός - Fertekiot, Semenderiot, & Ulugatshiot Cappadocian

Πεντικόν - Pontic

Pendiko - Romeyka

Пинко - Mariupolitan

Ποντίτζιν - Cypriot

Φιράν - Cypriot Arabic

Φαρέ - Karamanlidika

Μυ - Arvanite

Σοάρικου - Aromanian

Κερμουσό/Σιμιακό - Romani

Bee

*meliťťa - Proto-Greek

Μέλισσα- Ancient Greek

Μέλιττα - Attic Greek

Μέλισσα - Modern Greek

Σουκροζουζούνι - Kaliarda

Milìssi - Italiot

Μελισσά- Tsakonian

Meltsa - Patriot

Μίλισσα - Sarakatsani

Μέλισσα - Cappadocian

Ντώκι ογούλ - Mistiot Cappadocian

Μελισσόκκο - Pharasiot

Μέλισσα - Pontic

Şkepith - Romeyka

Мелыш - Mariupolitan

Μέλισσα- Cypriot

Νάχλε/Ναχλ - Cypriot Arabic

Ἀρή - Karamanlidika

Μπλέτε̱ - Arvanite

Αλγκίνα - Aromanian

Butterfly

Ψυχή - Ancient Greek

Πεταλούδα - Modern Greek

Παπίγια - Kaliarda

Ajarài - Italiot

Ψουχαρούδα - Tsakonian

Φλετουρίδα - Northern Epirot

Perpiras - Patriot

Πεταλαγκαρ - Cappadocian

Παχτσ̌ίτσ̌α - Pontic

Petalitsa - Romeyka

Петалудъа- Mariupolitan

Κελεπ̇έκ̇ - Karamanlidika

Παπεροάνα/Πιρπιρούνα/Φλίτουρα/Φίτουρου - Aromanian

Bear

Ἄρκτος - Ancient Greek

Αρκούδα- Modern Greek

Μπαλογουγούλφω - Kaliarda

Αρκούδα - Maniot

Αρκούδα - Tsakonian

Arkuda - Patriot

Αρκούδι - Sarakatsani

Αρκούδα - Cappadocian

Αρκούδι - Pharasiot

Αρκούδι - Afshar-Koi Pharasiot

Άρκος - Pontic

Аркдъыя - Mariupolitan

Αρκούος - Cypriot

Ἀγιοῦ/Ἀγ̇ή - Karamanlidika

Κουμπίλιε/Αρούσ̈ε̱ - Arvanite

Ούρσα - Aromanian

Ρισ̇νό - Romani

Wolf

Λύκος - Ancient Greek

Λύκος - Modern Greek

Γουγούλφης - Kaliarda

Liko - Italiot

Líko - Calabrian Griko

Λούκε - Maniot

Λιουκο - Tsakonian

Λιούκος - Old Athenian

Likus - Patriot

Λύκους - Naoussian

Ούκο - Propontian Tsakonian

Λύκους - Tenediot

Τζ̌αναβάριν - Lycian

Λύκος - Cappadocian

Λύκους - Mistiot Cappadocian

Λύκος - Pharasiot

Λύκους - Tshukuriot and Kiskiot Pharasiot

Λύκον - Pontic

Likos - Romeyka

Лыкус - Mariupolitan

Λύκος - Cypriot

Κούρτ - Karamanlidika

Ούλκου - Arvanite

Λούπου - Aromanian

Ρούβ/Ρούφ - Romani

Bird

Ὄρνεον - Ancient Greek

Πουλί - Modern Greek

Pikùli - Italiot

Puḍḍía - Calabrian Griko

Πουλί - Tsakonian

Πουλί - Propontic Tsakonian

Πλι - Epirote

Pli - Patriot

Πλι - Sarakatsani

Π'λι - Imbriot

Π'λι - Tenediot

Πουλί - Smyrniot

Πουλί - Silliot

Πουλί - Cappadocian

Πουλί - Pharasiot

Πουλί - Pontic

Плы/Пулыя - Mariupolitan

Πουλλίν - Cypriot

Κούς̇ - Karamanlidika

Ζοκ - Arvanite

Πούλιου/Πουπάζα - Aromanian

Τσ̇ιρικλί - Romani

Eagle

Ἀετός - Ancient Greek

Αἰετὸς - Ionic

Αἰετὸς - Doric

Αἰβετός - Pamphylian

Αετός - Modern Greek

Àkula - Italiot

Αϊτό/Ατιός - Maniot

Αετέ/Aϊτέ - Tsakonian

Αϊτός - Sarakatsani

Καρτάλι - Thracian

Καρτάλι - Trigliot Bithynian

Αετός - Silatiot Cappadocian

Κυνογάρ- Pharasiot

Αητέντς - Pontic

Айтос- Mariupolitan

Ορνίας - Cypriot

Καρτάλ - Karamanlidika

Σ̈κίπε - Arvanite

Αϊτό/Σκιποάνε - Aromanian

Horse

*íkkʷos - Proto-Greek

𐀂𐀦/𐂃 (i-qo/ikkwos) - Mycenaean

Ἵππος - Ancient Greek

Άλογο - Modern Greek

Ampàri - Salentiniot Italiot

Μπεγίρι/Φαρί - Cretan

Αλόγο - Maniot

Αόγο - Tsakonian

Άλογον - Old Athenian

Πράμα - Northern Epirot

Άλουγου - Naoussian

Aluğu - Patriot

Άτι/Άλουγου - Sarakatsan

Άλοο - Trigliot Bithynian

Άογο - Propontian Tsakonian

Άλιγου - Tenediot

Άλοα - Smyrniot

Παρίππα - Gyöldiot

Ἄλοουν/Ἀτ̔άϊ - Lycian

Άλογο - Cappadocian

Άλουγου - Mistiot Cappadocian

Άλουγου - Malakopiot Cappadocian

Άβγο - Pharasiot

Άβγου -Tshukuriot Pharasiot

Aloğon - Romeyka

Άλογον- Pontic

Алгу - Mariupolitan

Άππαρος - Cypriot

Γτίσ̲/Γτουσ̲ - Cypriot Arabic

Ἄτ - Karamanlidika

Καλj - Arvanite

Άτου/Κάλου/Μπινέκου/Ντούρο - Aromanian

Γράστ’ - Romani

Donkey

Ὄνος - Ancient Greek

Γαϊδούρι - Modern Greek

Gádaro - Calabrian Griko

Φόρτικας - Kerkyrot

Γαδιιάρος/Γάδαρο - Maniot

Γαϊδούρι - Tsakonian

Γουμάρ - Epirote

Ğumar/Ğumara - Patriot

Γουμάρι - Naoussian

Γουμάρι - Sarakatsani

Μερκέπι - Trigliot Bithynian

Γαϊδούρι- Propontian Tsakonian

Γάδαρους - Aivaliot

Γάσαρος - Smyrniot

Γαϊνταρους - Silliot

Γαϊντούρ - Mistiot Cappadocian

Γαϊντούρ - Axeniot Cappadocian

Γκαϊντούρ - Ulagatch

Γαϊρίδι/Γαϊδίρι - Pharasiot

Γαϊδούρ - Pontic

Ğaydzaro - Romeyka

Гайдъур - Mariupolitan

Γάρος - Cypriot

Χμαρ/Χμιρ - Cypriot Arabic

Γαϊδούρ - Arvanite

Γουμάρου/Τάρου - Aromanian

Χερ - Romani

Ox

*gʷous - Proto-Greek

𐀦𐀄/𐂌 (Gwu) - Mycenaean Greek

Βοῦς - Ancient Greek

Βῶς - Doric

Βόδι - Modern Greek

Vui - Salentiniot Italiot

Βούι - Cretan

Βόϊδι - Maniot

Βου - Tsakonian

Void - Patriot

Ντανάς - Smyrniot

Ουκούζ - Fertek Cappadocian

Βόϊ - Mistiot, Ulagachiot, & Axenitic Cappadocian

Βόϊδ/Βόδ - Delmesiot Cappadocian

Βόϊθ - Silatiot Cappadocian

Βόθ - Malakopiot Cappadocian

Βόϊχ - Axenitic Cappadocian

Βώρ - Aravaniot & Gurzoniot Cappadocian

Βόϊτ - Phloitiot & Potamiot Cappadocian

Βόϊδι - Pharasiot

Vuyidzo - Romeyka

Βούδ - Pontic

Водъ - Mariupolitan

Θορ/Πάκαρ - Cypriot Arabic

Ο̇̓κιȣ̇́ζ - Karamanlidika

Μπόου - Aromanian

Γκουρούβ - Romani

Cow

Ἀγελάς - Ancient Greek

Αγελάδα - Modern Greek

Μπαλοκάρνα/Γαλοκάρνα - Kaliarda

Aielàda- Salentiniot Italiot

Αελιά - Cretan

Αγελάδα - Maniot

Κούλικα - Tsakonian

Γελάδ’ - Epirote

Yilada - Patriot

Αγιλάδα - Naoussian

Γιλάδα - Sarakatsani

Αελάδα - Trigliot Bithynian

Αγεουάδα/Αγεβουάδα - Propontian Tsakonian

Γιλάδα - Tenediot

Ἀιλ̣ιὰ - Lycian

Χτήνου - Mistiot Cappadocian

Χτήνο - Limniot Cappadocian

Χτηνό- Cappadocian

Εϊλέτ/Εγιλέτ - Fertekiot Cappadocian

Γιάδι - Pharasiot and Tshukuriot Pharasiot

Αγελάδ - Pontic

Хтыно/Хно- Mariupolitan

Κατσέλλα - Cypriot

Πάκρα/Πακράτ - Cypriot Arabic

Ἰνέκ̇ - Karamanlidika

Λιόπε̱ - Arvanite

Βάκα - Aromanian

Γκουρουμνί/Γκουρουνί - Romani

Goat

𐁁𐀼/𐁒 (Aidza) - Mycenaean Greek

Αἴξ - Ancient Greek

Αιξ/Γίδι- Modern Greek

Μάτα - Kaliarda

Itza - Salentino Griko

Éga - Calabrian Griko

Αίγα - Cretan

Γίδι - Maniot

Χίμαιρε - Tsakonian

Αίγα - Northern Epirote

Kaçik - Patriot

Γίδα - Naoussian

Γίδι - Sarakatsani

Γίχ/Κετσί - Cappadocian

Τσίκιτς - Mistiot Cappadocian

Ίδι/Κετσί - Pharasiot & Tshukuriot & Kiskiot Pharasiot

Eyith - Romeyka

Αιίδ/Αιγίδ - Pontic

Зарка/Така- Mariupolitan

Αίγια - Cypriot

Γ̱άνζε/Μάγ̱αζεν - Cypriot Arabic

Κετσί - Karamanlidika

Δί - Arvanite

Μπουζνό - Romani

Lamb

Proto *warḗn

*warḗn - Proto-Greek

Ἀρήν - Ancient Greek

Ἄρνα - Epic Greek

Ϝαρήν - Doric

Αρνί - Modern Greek

Arnì - Salentino Italiot

Arní - Calabrian Griko

Κουράδι - Cretan

Αρνί - Maniot

βάννε - Tsakonian

Arni - Patriot

Αρνί - Smyrniot

Κουζὶν - Lycian

Αρνί/Γουζού - Cappadocian

Αρνίχ - Ulugatchiot Cappadocian

Γουζί- Pharasiot

Αρνίν - Pontic

Арныц- Mariupolitan

Κουζοῦ - Karamanlidika

Μλιόρου/Νιέλου/Νουάτινου/Σουγκάρου - Aromanian

Turtle

Χέλυς - Ancient Greek

Χελώνα - Modern Greek

Chelòna - Salentiniot Italiot

Χεούνα - Tsakonian

Gahilona - Patriot

Αχιλώνα - Naoussian

Χεούνα - Propontian Tsakonian

Αχιλώνα - Smyrniot

Σ̌ολώνα - Silliot

Χελώνα - Cappadocian

Σ̌ώνα - Pharasiot

Tosbağaı - Romeyka

Τοσπαγάνος - Pontic

Мега шлона - Mariupolitan

Σ̌ελώνα - Cypriot

Μπρε̱σ̈κε̱ - Arvanite

Κάθα/Μπροάσκα - Aromanian

Χέλγκα/Ζ̇άμμπα - Romani

Spider

Ἀράχνη - Ancient Greek

Αράχνη - Modern Greek

Karrukèddha - Italiot Sal

Σφαλάγκι - Kerkyrot

Αρογαλίδα - Cretan

Αράχνα/Κομπίο - Tsakonian

Σφάλιαγκας - Epirote

Μερμάγκα - Northern Epirote

Baiangas - Patriot

Κατράγκαθους - Imbriot

Αλυφαντής - Tenediot

Καματιρή - Lycian

Τυλιγάρ/Κολαχός- Cappadocian

Τσάντσαρος - Pontic

Руи - Mariupolitan

Ο̇̓ρȣμδζέκ̇ - Karamanlidika

Μαρμάγγε̱ - Arvanite

Αράχνε/Μεριμάγκα/Πάγγου/Πάνγκανου - Aromanian

Puppy

Κυνίδιον - Ancient Greek

Κουτάβι - Modern Greek

Figghjazzúni - Calabrian Griko

Κουνάρι - Tsakonian

Κταβ - Epirote

Κουτσιαβέλι - Northern Epirote

Κ'τάβ' - Rumeliot

Κτάβ - Tenediot

Κουλάκ/Κουλούκι - Cappadocian

Κουτάβιν - Pontic

Кулуч - Mariupolitan

Κοκόνι/Κουλίσσι - Arvanite

Κατσάλου/Κατσαλίκου - Aromanian

Ρικονό - Romani

Chicken

Κόττος - Ancient Greek

Κότα - Modern Greek

Κάκνα/Κακνή - Kaliarda

Ὸrnisa - Italiot

Όρνιθα - Cretan

Κότα - Tsakonian

Kota/Arnitha - Patriot

Ουρνίθα - Naoussian

Όρνιθα - Constantinopolitan

Ορνίθι/Ροβίθι - Trigliot Bithynian

Όρθα - Aivaliot

Όρνιθα - Smyrniot

Ορνίχ - Mistiot Cappadocian

Όρνι'το - Limniot Cappadocian

Κολόκκα - Ulagatchiot & Axenitic Cappadocian

Kosara - Romeyka

Κοσσάρα - Pontic

Арнытъ - Mariupolitan

Όρνιθα - Cypriot

Ζ̱έζ̲ε/Ζ̱εζ̲ - Cypriot Arabic

Ταούκ/Ταγούκ - Karamanlidika

Πούλε̱ - Arvanite

Γκαλίνα - Aromanian

Καχνί/Κχαγινί/Κχανί - Romani

Goose

*kʰā́n - Proto-Greek

𐀏𐀜 (Khan) - Mycenaean

Χήν - Ancient Greek

Χάν - Doric

Χήνα - Modern Greek

Χήνα - Maniot

Γάζ - Mistiot Cappadocian

Γαζ' - Limniot Cappadocian

Κάς - Ulagatsiot Cappadocian

Κάζα- Pharasiot

Κάζ- Pontic

Хаз/Шнар- Mariupolitan

Σ̌ήνα - Cypriot

Κάζ - Karamanlidika

Γκάσκα/Χήνα/Μίσκα/Πάτα - Aromanian

Παπίν - Romani

Fox

*alōpēḱos - Proto-Greek

Ἀλώπηξ/Βασσάρα - Ancient Greek

Αλεπού - Modern Greek

Πονηροντόγκα/Τσουρνόκοτα - Kaliarda

Αλουπού - Northern Epirote

Alipùna - Italiot

Alupuda - Calabrian Griko

Αλεπού - Tsakonian

Αλπού - Epirote

Alupu - Patriot

Αλουπού - Naoussian

Ἀλαπού - Lycian

Ντιλκίς - Cappadocian

Αλιμπήκα - Phloitiot Cappadocian

Αληπήκα - Silatiot Cappadocian

Ἀλ̣ημπίκ-κα - Axenitic Cappadocian

Αλημπίκ-κα - Limniot Cappadocian

Αλυμπύκια - Mistiot Cappadocian

Αωπός - Afshar-Koi Pharasiot

Απός- Pharasiot

Parthi/Thepekos - Romeyka

Αλεπουδόπον - Pontic

Алэпу - Mariupolitan

Αλουπός - Cypriot

Τ̇ιλκ̇ί/Τιλκ̇ί - Karamanlidika

Dέλπιρε̱ - Arvanite

Βούλπε - Aromanian

Lion

𐀩𐀺 (re-wo/lewon)

Λέων - Ancient Greek

Λιοντάρι - Modern Greek

Ζουγκλογουγούλφης - Kaliarda

Λιοντάρι - Tsakonian

Λεοντάρι - Rumeliot

Ασλάνι - Trigliot Bithynian

Ασλάνος - Delmesiot Cappadocian

Ασλάνης - Ghurzoniot Cappadocian

Ασλάν - Axenitic Cappadocian

Ασλάν - Pharasiot

Ασλάνης/Λεοντάριν - Pontic

Аслан - Mariupolitan

Λιοντάριν - Cypriot

Ἀρσλάν - Karamanlidika

Hare

Λαγώς - Ancient Greek

Λαγωός - Homeric

Λαγός - Ionic

Λαγός - Modern Greek

Alaò - Italiot

Λάγος - Maniot

Αγό - Tsakonian

Lağos - Patriot

Λαγός - Imbriot

Λαγός - Cappadocian

Νταφσ̌άν - Ulagatshiot Cappadocian

Αγός - Pharasiot

Tağuşanos - Romeyka

Лаго - Mariupolitan

Λαός - Cypriot

Άρνεπ/Ράνεπ - Cypriot Arabic

Ταβσ̇άν - Karamanlidika

Λιέπουρι - Arvanite

Λιέπουρου/Λιέπρε/Λιόπουρου - Aromanian

Σ̇οσ̇όγι - Romani

Crow

Κορώνη- Ancient Greek

Κοράκι/Κουρούνα - Modern Greek

Kràulo - Italiot

Κόρακα - Tsakonian

Κρούνα - Epirote

Τζιερμπούνι - Northern Epirote

Κάργα - Thracian

Κάργα - Trigliot Bithynian

Καργάς - Cappadocian

Γαργάς - Limniot Cappadocian

Курона - Mariupolitan

Κάργα - Karamanlidika

Κόρακου/Κόρμπου/Κουάρμπου - Aromanian

Snake

ὄφις- Ancient Greek

Φίδι - Modern Greek

Βιβοσέρμελο - Kaliarda

Afidi- Italiot

Όφις - Cretan

Ούϊθι - Tsakonian

Fid - Patriot

Όφιους - Sarakatsani

Φίθ - Propontian Tsakonian

ὄφιους - Lycian

Φίρι - Silliot

Φΐι - Mistiot Cappadocian

Φίδ - Potamiot Cappadocian

Φίθ - Phloitiot & Silatiot Cappadocian

Φί/Φίχ - Ulagatshiot & Axenitic Cappadocian

Φίζ - Semenderiot Cappadocian

Οφίρ- Ghurzoniot & Aravaniot Cappadocian

Φίδι- Pharasiot & Afshar-Koi Pharasiot

Ofis - Romeyka

Οφίδ - Pontic

Фидъ - Mariupolitan

Φίιν - Cypriot

Γ̱άφα/Φάγ̱ι - Cypriot Arabic

Γιλάν - Karamanlidika

Γκιάρπε̱ρι - Arvanite

Σάρπε - Aromanian

Σαπ - Romani

Frog

Βάτραχος- Ancient Greek

Βάθρακος/Βότραχος/Βρόταχος - Ionian

Βριαγζόνη - Phocaean

Βάβακος - Ancient Pontic

Βράταχος - Ancient Cypriot

Βάτραχος - Modern Greek

Μπαλοκουάκης/Γκροσοκουάκης - Kaliarda

Κάρλακας - Kerkyrot

Σπορδακάς - Zakynthiot

Αβοθρακός/Αφορδακός - Cretan

Μπάκακας - Maniot

Βαθρακός/Βάρθακας - Old Athenian

Μπακακάκι - Epirote

Ζιάπα - Northern Epirote

Jiabakas - Patriot

Μπάκακας - Sarakatsani

Μαθρακός - Tenediot

Βάρθακας - Smyrniot

Βοθρακός - Kalymniot

Τσάφλακας - Lycian

Φάρτακα - Silliot

Πάρτλακα - Mistiot Cappadocian

Βάρτλακα - Ghurzoniot Cappadocian

Βαρχιάκα - Axenitic Cappadocian

Βατράκα - Fertekiot Cappadocian

Βαθράκα - Silatiot Cappadocian

Μαθράκα- Pharasiot

Furnos - Romeyka

Φουρνός - Pontic

Багачуна/Баркакана - Mariupolitan

Κουρπ̇αγά - Karamanlidika

Βόρτακας - Cypriot

Καραγ̱ούλα/Καραγ̱ούλες - Cypriot Arabic

Μπε̱ρτε̱κοσε̱ - Arvanite

Μπροάσκα/Μπάμπα - Aromanian

#language#languages#greek#hellenic languages#greek language#tsakonian#griko#Cappadocian#cappadocian greek#Pontic#Pontic Greek#ancient greek#Cypriot

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today we also celebrate the Holy Queen Theodora of Arta. Theodora was born in Thessaloniki sometime between 1210 and 1216, and married Michael II Komnenos Doukas, the ruler of Epirus and Thessaly shortly after his accession in 1231, while still a child. Despite her being pregnant with Michael's son Nikephoros, she was soon banished from the court by her husband, who preferred to live with his mistress. Living in poverty, she endured her hardship without complaint, sheltered by a priest from the village of Prinista. Her exile lasted for five years, after which Michael repented and called her back to him. The couple thereafter lived together. As consort of Epirus, Theodora is reported to have favoured closer ties with Epirus' traditional rival for the succession of the Byzantine imperial heritage, the Empire of Nicaea. She is also recorded by the contemporary historian George Akropolites as accompanying her son Nikephoros for his betrothal and later his marriage to Maria, the daughter of the Nicaean emperor Theodore II Laskaris (r. 1254–1258). The rapprochement brought about a settlement of the two realms' ecclesiastical disputes and led to the conferment of the title of despotes on Michael, but did not last long. Theodora also founded the convent of St. George in the Epirote capital, Arta, where she retired after Michael's death, and where she was buried. It later became known as the Church of St. Theodora, and her tomb became the site of pilgrimage, as many miracles have been attributed to it. May she intercede for us always + Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodora_of_Arta (at Megalóchari, Arta, Greece) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ca8F_prvaUV/?utm_medium=tumblr

17 notes

·

View notes