#Diatoma

Text

apokalypse

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tattoo girl masturbation

Tara Ashley rides hunk guys huge cock

Candid bbw white woman in tight jeans

This chastity device will stop you from jerking off permanently

Hot interracial amateur couple cum on belly

Eu dando aquela chupada e punhetando gostoso

Hairy granny tribbing cute teen

Bombshell brunette Gia Paige rubs her wet pussy

Gamer dude gets the best deep throat blowjob with hardcore cumshot

Bigtits brunette Crystal Rush anal fucked

#Naamana#ectiris#Nealey#beholds#Epirote#nonarticulately#exemptions#overaccelerating#cosmicality#chieftainries#nontribally#Diatoma#circumsphere#Jurdi#progressionism#Post-hittite#subchancel#Wellman#macabre#counterplay

0 notes

Text

[S04E06] The Gospel of Judah

"Just about three years, I been in this place. Long years, but fruitful."

Brother Judah entered Diatoma Penitentiary of their own volition, Called to help people there. Now the Call is telling them it’s time to leave.

[S04E6] The Gospel of Judah

This episode features eating noises, and a prolonged repetitive alarm sound.

A version without those elements can be found here:

This episode was written and directed by Kasha Mika, & edited by Sam Stark.

It features Kale Brown, Ari Ingalls, Aubrey Akers, Hera Alexander, Oz Stark, Max Newland, Rachel Scully, Jeremy Tucker, & Adam Steven Halecki.

It includes Emma Laslett, & Taylor Michaels.

It was transcribed by Cass Scott.

And join us tonight at 6pm pacific for our live listen premier.

youtube

We also are thrilled to have a trailer for Traveling Light by @monstrousproductions at the end of this episode, a science fantasy podcast following the Traveler as they explore their galaxy, collecting stories from the people they meet & adding them to their community archives.

More about the show and where to listen can be found here:

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

20k Leagues under the sea, Jules Verne

part 2, chapter 14-15

CHAPTER XIV

THE SOUTH POLE

I rushed on to the platform. Yes! the open sea, with but a few scattered pieces of ice and moving icebergs—a long stretch of sea; a world of birds in the air, and myriads of fishes under those waters, which varied from intense blue to olive green, according to the bottom. The thermometer marked 3° C. above zero. It was comparatively spring, shut up as we were behind this iceberg, whose lengthened mass was dimly seen on our northern horizon.

“Are we at the pole?” I asked the Captain, with a beating heart.

“I do not know,” he replied. “At noon I will take our bearings.”

“But will the sun show himself through this fog?” said I, looking at the leaden sky.

“However little it shows, it will be enough,” replied the Captain.

About ten miles south a solitary island rose to a height of one hundred and four yards. We made for it, but carefully, for the sea might be strewn with banks. One hour afterwards we had reached it, two hours later we had made the round of it. It measured four or five miles in circumference. A narrow canal separated it from a considerable stretch of land, perhaps a continent, for we could not see its limits. The existence of this land seemed to give some colour to Maury’s theory. The ingenious American has remarked that, between the South Pole and the sixtieth parallel, the sea is covered with floating ice of enormous size, which is never met with in the North Atlantic. From this fact he has drawn the conclusion that the Antarctic Circle encloses considerable continents, as icebergs cannot form in open sea, but only on the coasts. According to these calculations, the mass of ice surrounding the southern pole forms a vast cap, the circumference of which must be, at least, 2,500 miles. But the Nautilus, for fear of running aground, had stopped about three cable-lengths from a strand over which reared a superb heap of rocks. The boat was launched; the Captain, two of his men, bearing instruments, Conseil, and myself were in it. It was ten in the morning. I had not seen Ned Land. Doubtless the Canadian did not wish to admit the presence of the South Pole. A few strokes of the oar brought us to the sand, where we ran ashore. Conseil was going to jump on to the land, when I held him back.

“Sir,” said I to Captain Nemo, “to you belongs the honour of first setting foot on this land.”

“Yes, sir,” said the Captain, “and if I do not hesitate to tread this South Pole, it is because, up to this time, no human being has left a trace there.”

Saying this, he jumped lightly on to the sand. His heart beat with emotion. He climbed a rock, sloping to a little promontory, and there, with his arms crossed, mute and motionless, and with an eager look, he seemed to take possession of these southern regions. After five minutes passed in this ecstasy, he turned to us.

“When you like, sir.”

I landed, followed by Conseil, leaving the two men in the boat. For a long way the soil was composed of a reddish sandy stone, something like crushed brick, scoriae, streams of lava, and pumice-stones. One could not mistake its volcanic origin. In some parts, slight curls of smoke emitted a sulphurous smell, proving that the internal fires had lost nothing of their expansive powers, though, having climbed a high acclivity, I could see no volcano for a radius of several miles. We know that in those Antarctic countries, James Ross found two craters, the Erebus and Terror, in full activity, on the 167th meridian, latitude 77° 32′. The vegetation of this desolate continent seemed to me much restricted. Some lichens lay upon the black rocks; some microscopic plants, rudimentary diatomas, a kind of cells placed between two quartz shells; long purple and scarlet weed, supported on little swimming bladders, which the breaking of the waves brought to the shore. These constituted the meagre flora of this region. The shore was strewn with molluscs, little mussels, and limpets. I also saw myriads of northern clios, one-and-a-quarter inches long, of which a whale would swallow a whole world at a mouthful; and some perfect sea-butterflies, animating the waters on the skirts of the shore.

There appeared on the high bottoms some coral shrubs, of the kind which, according to James Ross, live in the Antarctic seas to the depth of more than 1,000 yards. Then there were little kingfishers and starfish studding the soil. But where life abounded most was in the air. There thousands of birds fluttered and flew of all kinds, deafening us with their cries; others crowded the rock, looking at us as we passed by without fear, and pressing familiarly close by our feet. There were penguins, so agile in the water, heavy and awkward as they are on the ground; they were uttering harsh cries, a large assembly, sober in gesture, but extravagant in clamour. Albatrosses passed in the air, the expanse of their wings being at least four yards and a half, and justly called the vultures of the ocean; some gigantic petrels, and some damiers, a kind of small duck, the underpart of whose body is black and white; then there were a whole series of petrels, some whitish, with brown-bordered wings, others blue, peculiar to the Antarctic seas, and so oily, as I told Conseil, that the inhabitants of the Ferroe Islands had nothing to do before lighting them but to put a wick in.

“A little more,” said Conseil, “and they would be perfect lamps! After that, we cannot expect Nature to have previously furnished them with wicks!”

About half a mile farther on the soil was riddled with ruffs’ nests, a sort of laying-ground, out of which many birds were issuing. Captain Nemo had some hundreds hunted. They uttered a cry like the braying of an ass, were about the size of a goose, slate-colour on the body, white beneath, with a yellow line round their throats; they allowed themselves to be killed with a stone, never trying to escape. But the fog did not lift, and at eleven the sun had not yet shown itself. Its absence made me uneasy. Without it no observations were possible. How, then, could we decide whether we had reached the pole? When I rejoined Captain Nemo, I found him leaning on a piece of rock, silently watching the sky. He seemed impatient and vexed. But what was to be done? This rash and powerful man could not command the sun as he did the sea. Noon arrived without the orb of day showing itself for an instant. We could not even tell its position behind the curtain of fog; and soon the fog turned to snow.

“Till to-morrow,” said the Captain, quietly, and we returned to the Nautilus amid these atmospheric disturbances.

The tempest of snow continued till the next day. It was impossible to remain on the platform. From the saloon, where I was taking notes of incidents happening during this excursion to the polar continent, I could hear the cries of petrels and albatrosses sporting in the midst of this violent storm. The Nautilus did not remain motionless, but skirted the coast, advancing ten miles more to the south in the half-light left by the sun as it skirted the edge of the horizon. The next day, the 20th of March, the snow had ceased. The cold was a little greater, the thermometer showing 2° below zero. The fog was rising, and I hoped that that day our observations might be taken. Captain Nemo not having yet appeared, the boat took Conseil and myself to land. The soil was still of the same volcanic nature; everywhere were traces of lava, scoriae, and basalt; but the crater which had vomited them I could not see. Here, as lower down, this continent was alive with myriads of birds. But their rule was now divided with large troops of sea-mammals, looking at us with their soft eyes. There were several kinds of seals, some stretched on the earth, some on flakes of ice, many going in and out of the sea. They did not flee at our approach, never having had anything to do with man; and I reckoned that there were provisions there for hundreds of vessels.

“Sir,” said Conseil, “will you tell me the names of these creatures?”

“They are seals and morses.”

It was now eight in the morning. Four hours remained to us before the sun could be observed with advantage. I directed our steps towards a vast bay cut in the steep granite shore. There, I can aver that earth and ice were lost to sight by the numbers of sea-mammals covering them, and I involuntarily sought for old Proteus, the mythological shepherd who watched these immense flocks of Neptune. There were more seals than anything else, forming distinct groups, male and female, the father watching over his family, the mother suckling her little ones, some already strong enough to go a few steps. When they wished to change their place, they took little jumps, made by the contraction of their bodies, and helped awkwardly enough by their imperfect fin, which, as with the lamantin, their cousins, forms a perfect forearm. I should say that, in the water, which is their element—the spine of these creatures is flexible; with smooth and close skin and webbed feet—they swim admirably. In resting on the earth they take the most graceful attitudes. Thus the ancients, observing their soft and expressive looks, which cannot be surpassed by the most beautiful look a woman can give, their clear voluptuous eyes, their charming positions, and the poetry of their manners, metamorphosed them, the male into a triton and the female into a mermaid. I made Conseil notice the considerable development of the lobes of the brain in these interesting cetaceans. No mammal, except man, has such a quantity of brain matter; they are also capable of receiving a certain amount of education, are easily domesticated, and I think, with other naturalists, that if properly taught they would be of great service as fishing-dogs. The greater part of them slept on the rocks or on the sand. Amongst these seals, properly so called, which have no external ears (in which they differ from the otter, whose ears are prominent), I noticed several varieties of seals about three yards long, with a white coat, bulldog heads, armed with teeth in both jaws, four incisors at the top and four at the bottom, and two large canine teeth in the shape of a fleur-de-lis. Amongst them glided sea-elephants, a kind of seal, with short, flexible trunks. The giants of this species measured twenty feet round and ten yards and a half in length; but they did not move as we approached.

“These creatures are not dangerous?” asked Conseil.

“No; not unless you attack them. When they have to defend their young their rage is terrible, and it is not uncommon for them to break the fishing-boats to pieces.”

“They are quite right,” said Conseil.

“I do not say they are not.”

Two miles farther on we were stopped by the promontory which shelters the bay from the southerly winds. Beyond it we heard loud bellowings such as a troop of ruminants would produce.

“Good!” said Conseil; “a concert of bulls!”

“No; a concert of morses.”

“They are fighting!”

“They are either fighting or playing.”

We now began to climb the blackish rocks, amid unforeseen stumbles, and over stones which the ice made slippery. More than once I rolled over at the expense of my loins. Conseil, more prudent or more steady, did not stumble, and helped me up, saying:

“If, sir, you would have the kindness to take wider steps, you would preserve your equilibrium better.”

Arrived at the upper ridge of the promontory, I saw a vast white plain covered with morses. They were playing amongst themselves, and what we heard were bellowings of pleasure, not of anger.

As I passed these curious animals I could examine them leisurely, for they did not move. Their skins were thick and rugged, of a yellowish tint, approaching to red; their hair was short and scant. Some of them were four yards and a quarter long. Quieter and less timid than their cousins of the north, they did not, like them, place sentinels round the outskirts of their encampment. After examining this city of morses, I began to think of returning. It was eleven o’clock, and, if Captain Nemo found the conditions favourable for observations, I wished to be present at the operation. We followed a narrow pathway running along the summit of the steep shore. At half-past eleven we had reached the place where we landed. The boat had run aground, bringing the Captain. I saw him standing on a block of basalt, his instruments near him, his eyes fixed on the northern horizon, near which the sun was then describing a lengthened curve. I took my place beside him, and waited without speaking. Noon arrived, and, as before, the sun did not appear. It was a fatality. Observations were still wanting. If not accomplished to-morrow, we must give up all idea of taking any. We were indeed exactly at the 20th of March. To-morrow, the 21st, would be the equinox; the sun would disappear behind the horizon for six months, and with its disappearance the long polar night would begin. Since the September equinox it had emerged from the northern horizon, rising by lengthened spirals up to the 21st of December. At this period, the summer solstice of the northern regions, it had begun to descend; and to-morrow was to shed its last rays upon them. I communicated my fears and observations to Captain Nemo.

“You are right, M. Aronnax,” said he; “if to-morrow I cannot take the altitude of the sun, I shall not be able to do it for six months. But precisely because chance has led me into these seas on the 21st of March, my bearings will be easy to take, if at twelve we can see the sun.”

“Why, Captain?”

“Because then the orb of day described such lengthened curves that it is difficult to measure exactly its height above the horizon, and grave errors may be made with instruments.”

“What will you do then?”

“I shall only use my chronometer,” replied Captain Nemo. “If to-morrow, the 21st of March, the disc of the sun, allowing for refraction, is exactly cut by the northern horizon, it will show that I am at the South Pole.”

“Just so,” said I. “But this statement is not mathematically correct, because the equinox does not necessarily begin at noon.”

“Very likely, sir; but the error will not be a hundred yards and we do not want more. Till to-morrow, then!”

Captain Nemo returned on board. Conseil and I remained to survey the shore, observing and studying until five o’clock. Then I went to bed, not, however, without invoking, like the Indian, the favour of the radiant orb. The next day, the 21st of March, at five in the morning, I mounted the platform. I found Captain Nemo there.

“The weather is lightening a little,” said he. “I have some hope. After breakfast we will go on shore and choose a post for observation.”

That point settled, I sought Ned Land. I wanted to take him with me. But the obstinate Canadian refused, and I saw that his taciturnity and his bad humour grew day by day. After all, I was not sorry for his obstinacy under the circumstances. Indeed, there were too many seals on shore, and we ought not to lay such temptation in this unreflecting fisherman’s way. Breakfast over, we went on shore. The Nautilus had gone some miles further up in the night. It was a whole league from the coast, above which reared a sharp peak about five hundred yards high. The boat took with me Captain Nemo, two men of the crew, and the instruments, which consisted of a chronometer, a telescope, and a barometer. While crossing, I saw numerous whales belonging to the three kinds peculiar to the southern seas; the whale, or the English “right whale,” which has no dorsal fin; the “humpback,” with reeved chest and large, whitish fins, which, in spite of its name, do not form wings; and the fin-back, of a yellowish brown, the liveliest of all the cetacea. This powerful creature is heard a long way off when he throws to a great height columns of air and vapour, which look like whirlwinds of smoke. These different mammals were disporting themselves in troops in the quiet waters; and I could see that this basin of the Antarctic Pole serves as a place of refuge to the cetacea too closely tracked by the hunters. I also noticed large medusæ floating between the reeds.

At nine we landed; the sky was brightening, the clouds were flying to the south, and the fog seemed to be leaving the cold surface of the waters. Captain Nemo went towards the peak, which he doubtless meant to be his observatory. It was a painful ascent over the sharp lava and the pumice-stones, in an atmosphere often impregnated with a sulphurous smell from the smoking cracks. For a man unaccustomed to walk on land, the Captain climbed the steep slopes with an agility I never saw equalled and which a hunter would have envied. We were two hours getting to the summit of this peak, which was half porphyry and half basalt. From thence we looked upon a vast sea which, towards the north, distinctly traced its boundary line upon the sky. At our feet lay fields of dazzling whiteness. Over our heads a pale azure, free from fog. To the north the disc of the sun seemed like a ball of fire, already horned by the cutting of the horizon. From the bosom of the water rose sheaves of liquid jets by hundreds. In the distance lay the Nautilus like a cetacean asleep on the water. Behind us, to the south and east, an immense country and a chaotic heap of rocks and ice, the limits of which were not visible. On arriving at the summit Captain Nemo carefully took the mean height of the barometer, for he would have to consider that in taking his observations. At a quarter to twelve the sun, then seen only by refraction, looked like a golden disc shedding its last rays upon this deserted continent and seas which never man had yet ploughed. Captain Nemo, furnished with a lenticular glass which, by means of a mirror, corrected the refraction, watched the orb sinking below the horizon by degrees, following a lengthened diagonal. I held the chronometer. My heart beat fast. If the disappearance of the half-disc of the sun coincided with twelve o’clock on the chronometer, we were at the pole itself.

“Twelve!” I exclaimed.

“The South Pole!” replied Captain Nemo, in a grave voice, handing me the glass, which showed the orb cut in exactly equal parts by the horizon.

I looked at the last rays crowning the peak, and the shadows mounting by degrees up its slopes. At that moment Captain Nemo, resting with his hand on my shoulder, said:

“I, Captain Nemo, on this 21st day of March, 1868, have reached the South Pole on the ninetieth degree; and I take possession of this part of the globe, equal to one-sixth of the known continents.”

“In whose name, Captain?”

“In my own, sir!”

Saying which, Captain Nemo unfurled a black banner, bearing an “N” in gold quartered on its bunting. Then, turning towards the orb of day, whose last rays lapped the horizon of the sea, he exclaimed:

“Adieu, sun! Disappear, thou radiant orb! rest beneath this open sea, and let a night of six months spread its shadows over my new domains!”

CHAPTER XV

ACCIDENT OR INCIDENT?

The next day, the 22nd of March, at six in the morning, preparations for departure were begun. The last gleams of twilight were melting into night. The cold was great, the constellations shone with wonderful intensity. In the zenith glittered that wondrous Southern Cross—the polar bear of Antarctic regions. The thermometer showed 120 below zero, and when the wind freshened it was most biting. Flakes of ice increased on the open water. The sea seemed everywhere alike. Numerous blackish patches spread on the surface, showing the formation of fresh ice. Evidently the southern basin, frozen during the six winter months, was absolutely inaccessible. What became of the whales in that time? Doubtless they went beneath the icebergs, seeking more practicable seas. As to the seals and morses, accustomed to live in a hard climate, they remained on these icy shores. These creatures have the instinct to break holes in the ice-field and to keep them open. To these holes they come for breath; when the birds, driven away by the cold, have emigrated to the north, these sea mammals remain sole masters of the polar continent. But the reservoirs were filling with water, and the Nautilus was slowly descending. At 1,000 feet deep it stopped; its screw beat the waves, and it advanced straight towards the north at a speed of fifteen miles an hour. Towards night it was already floating under the immense body of the iceberg. At three in the morning I was awakened by a violent shock. I sat up in my bed and listened in the darkness, when I was thrown into the middle of the room. The Nautilus, after having struck, had rebounded violently. I groped along the partition, and by the staircase to the saloon, which was lit by the luminous ceiling. The furniture was upset. Fortunately the windows were firmly set, and had held fast. The pictures on the starboard side, from being no longer vertical, were clinging to the paper, whilst those of the port side were hanging at least a foot from the wall. The Nautilus was lying on its starboard side perfectly motionless. I heard footsteps, and a confusion of voices; but Captain Nemo did not appear. As I was leaving the saloon, Ned Land and Conseil entered.

“What is the matter?” said I, at once.

“I came to ask you, sir,” replied Conseil.

“Confound it!” exclaimed the Canadian, “I know well enough! The Nautilus has struck; and, judging by the way she lies, I do not think she will right herself as she did the first time in Torres Straits.”

“But,” I asked, “has she at least come to the surface of the sea?”

“We do not know,” said Conseil.

“It is easy to decide,” I answered. I consulted the manometer. To my great surprise, it showed a depth of more than 180 fathoms. “What does that mean?” I exclaimed.

“We must ask Captain Nemo,” said Conseil.

“But where shall we find him?” said Ned Land.

“Follow me,” said I, to my companions.

We left the saloon. There was no one in the library. At the centre staircase, by the berths of the ship’s crew, there was no one. I thought that Captain Nemo must be in the pilot’s cage. It was best to wait. We all returned to the saloon. For twenty minutes we remained thus, trying to hear the slightest noise which might be made on board the Nautilus, when Captain Nemo entered. He seemed not to see us; his face, generally so impassive, showed signs of uneasiness. He watched the compass silently, then the manometer; and, going to the planisphere, placed his finger on a spot representing the southern seas. I would not interrupt him; but, some minutes later, when he turned towards me, I said, using one of his own expressions in the Torres Straits:

“An incident, Captain?”

“No, sir; an accident this time.”

“Serious?”

“Perhaps.”

“Is the danger immediate?”

“No.”

“The Nautilus has stranded?”

“Yes.”

“And this has happened—how?”

“From a caprice of nature, not from the ignorance of man. Not a mistake has been made in the working. But we cannot prevent equilibrium from producing its effects. We may brave human laws, but we cannot resist natural ones.”

Captain Nemo had chosen a strange moment for uttering this philosophical reflection. On the whole, his answer helped me little.

“May I ask, sir, the cause of this accident?”

“An enormous block of ice, a whole mountain, has turned over,” he replied. “When icebergs are undermined at their base by warmer water or reiterated shocks their centre of gravity rises, and the whole thing turns over. This is what has happened; one of these blocks, as it fell, struck the Nautilus, then, gliding under its hull, raised it with irresistible force, bringing it into beds which are not so thick, where it is lying on its side.”

“But can we not get the Nautilus off by emptying its reservoirs, that it might regain its equilibrium?”

“That, sir, is being done at this moment. You can hear the pump working. Look at the needle of the manometer; it shows that the Nautilus is rising, but the block of ice is floating with it; and, until some obstacle stops its ascending motion, our position cannot be altered.”

Indeed, the Nautilus still held the same position to starboard; doubtless it would right itself when the block stopped. But at this moment who knows if we may not be frightfully crushed between the two glassy surfaces? I reflected on all the consequences of our position. Captain Nemo never took his eyes off the manometer. Since the fall of the iceberg, the Nautilus had risen about a hundred and fifty feet, but it still made the same angle with the perpendicular. Suddenly a slight movement was felt in the hold. Evidently it was righting a little. Things hanging in the saloon were sensibly returning to their normal position. The partitions were nearing the upright. No one spoke. With beating hearts we watched and felt the straightening. The boards became horizontal under our feet. Ten minutes passed.

“At last we have righted!” I exclaimed.

“Yes,” said Captain Nemo, going to the door of the saloon.

“But are we floating?” I asked.

“Certainly,” he replied; “since the reservoirs are not empty; and, when empty, the Nautilus must rise to the surface of the sea.”

We were in open sea; but at a distance of about ten yards, on either side of the Nautilus, rose a dazzling wall of ice. Above and beneath the same wall. Above, because the lower surface of the iceberg stretched over us like an immense ceiling. Beneath, because the overturned block, having slid by degrees, had found a resting-place on the lateral walls, which kept it in that position. The Nautilus was really imprisoned in a perfect tunnel of ice more than twenty yards in breadth, filled with quiet water. It was easy to get out of it by going either forward or backward, and then make a free passage under the iceberg, some hundreds of yards deeper. The luminous ceiling had been extinguished, but the saloon was still resplendent with intense light. It was the powerful reflection from the glass partition sent violently back to the sheets of the lantern. I cannot describe the effect of the voltaic rays upon the great blocks so capriciously cut; upon every angle, every ridge, every facet was thrown a different light, according to the nature of the veins running through the ice; a dazzling mine of gems, particularly of sapphires, their blue rays crossing with the green of the emerald. Here and there were opal shades of wonderful softness, running through bright spots like diamonds of fire, the brilliancy of which the eye could not bear. The power of the lantern seemed increased a hundredfold, like a lamp through the lenticular plates of a first-class lighthouse.

“How beautiful! how beautiful!” cried Conseil.

“Yes,” I said, “it is a wonderful sight. Is it not, Ned?”

“Yes, confound it! Yes,” answered Ned Land, “it is superb! I am mad at being obliged to admit it. No one has ever seen anything like it; but the sight may cost us dear. And, if I must say all, I think we are seeing here things which God never intended man to see.”

Ned was right, it was too beautiful. Suddenly a cry from Conseil made me turn.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Shut your eyes, sir! Do not look, sir!” Saying which, Conseil clapped his hands over his eyes.

“But what is the matter, my boy?”

“I am dazzled, blinded.”

My eyes turned involuntarily towards the glass, but I could not stand the fire which seemed to devour them. I understood what had happened. The Nautilus had put on full speed. All the quiet lustre of the ice-walls was at once changed into flashes of lightning. The fire from these myriads of diamonds was blinding. It required some time to calm our troubled looks. At last the hands were taken down.

“Faith, I should never have believed it,” said Conseil.

It was then five in the morning; and at that moment a shock was felt at the bows of the Nautilus. I knew that its spur had struck a block of ice. It must have been a false manœuvre, for this submarine tunnel, obstructed by blocks, was not very easy navigation. I thought that Captain Nemo, by changing his course, would either turn these obstacles or else follow the windings of the tunnel. In any case, the road before us could not be entirely blocked. But, contrary to my expectations, the Nautilus took a decided retrograde motion.

“We are going backwards?” said Conseil.

“Yes,” I replied. “This end of the tunnel can have no egress.”

“And then?”

“Then,” said I, “the working is easy. We must go back again, and go out at the southern opening. That is all.”

In speaking thus, I wished to appear more confident than I really was. But the retrograde motion of the Nautilus was increasing; and, reversing the screw, it carried us at great speed.

“It will be a hindrance,” said Ned.

“What does it matter, some hours more or less, provided we get out at last?”

“Yes,” repeated Ned Land, “provided we do get out at last!”

For a short time I walked from the saloon to the library. My companions were silent. I soon threw myself on an ottoman, and took a book, which my eyes overran mechanically. A quarter of an hour after, Conseil, approaching me, said, “Is what you are reading very interesting, sir?”

“Very interesting!” I replied.

“I should think so, sir. It is your own book you are reading.”

“My book?”

And indeed I was holding in my hand the work on the Great Submarine Depths. I did not even dream of it. I closed the book and returned to my walk. Ned and Conseil rose to go.

“Stay here, my friends,” said I, detaining them. “Let us remain together until we are out of this block.”

“As you please, sir,” Conseil replied.

Some hours passed. I often looked at the instruments hanging from the partition. The manometer showed that the Nautilus kept at a constant depth of more than three hundred yards; the compass still pointed to south; the log indicated a speed of twenty miles an hour, which, in such a cramped space, was very great. But Captain Nemo knew that he could not hasten too much, and that minutes were worth ages to us. At twenty-five minutes past eight a second shock took place, this time from behind. I turned pale. My companions were close by my side. I seized Conseil’s hand. Our looks expressed our feelings better than words. At this moment the Captain entered the saloon. I went up to him.

“Our course is barred southward?” I asked.

“Yes, sir. The iceberg has shifted and closed every outlet.”

“We are blocked up then?”

“Yes.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAPTER XIV THE SOUTH POLE

I rushed on to the platform. Yes! the open sea, with but a few scattered pieces of ice and moving icebergs—a long stretch of sea; a world of birds in the air, and myriads of fishes under those waters, which varied from intense blue to olive green, according to the bottom. The thermometer marked 3° C. above zero. It was comparatively spring, shut up as we were behind this iceberg, whose lengthened mass was dimly seen on our northern horizon.

“Are we at the pole?” I asked the Captain, with a beating heart.

“I do not know,” he replied. “At noon I will take our bearings.”

“But will the sun show himself through this fog?” said I, looking at the leaden sky.

“However little it shows, it will be enough,” replied the Captain.

About ten miles south a solitary island rose to a height of one hundred and four yards. We made for it, but carefully, for the sea might be strewn with banks. One hour afterwards we had reached it, two hours later we had made the round of it. It measured four or five miles in circumference. A narrow canal separated it from a considerable stretch of land, perhaps a continent, for we could not see its limits. The existence of this land seemed to give some colour to Maury’s theory. The ingenious American has remarked that, between the South Pole and the sixtieth parallel, the sea is covered with floating ice of enormous size, which is never met with in the North Atlantic. From this fact he has drawn the conclusion that the Antarctic Circle encloses considerable continents, as icebergs cannot form in open sea, but only on the coasts. According to these calculations, the mass of ice surrounding the southern pole forms a vast cap, the circumference of which must be, at least, 2,500 miles. But the Nautilus, for fear of running aground, had stopped about three cable-lengths from a strand over which reared a superb heap of rocks. The boat was launched; the Captain, two of his men, bearing instruments, Conseil, and myself were in it. It was ten in the morning. I had not seen Ned Land. Doubtless the Canadian did not wish to admit the presence of the South Pole. A few strokes of the oar brought us to the sand, where we ran ashore. Conseil was going to jump on to the land, when I held him back.

“Sir,” said I to Captain Nemo, “to you belongs the honour of first setting foot on this land.”

“Yes, sir,” said the Captain, “and if I do not hesitate to tread this South Pole, it is because, up to this time, no human being has left a trace there.”

Saying this, he jumped lightly on to the sand. His heart beat with emotion. He climbed a rock, sloping to a little promontory, and there, with his arms crossed, mute and motionless, and with an eager look, he seemed to take possession of these southern regions. After five minutes passed in this ecstasy, he turned to us.

“When you like, sir.”

I landed, followed by Conseil, leaving the two men in the boat. For a long way the soil was composed of a reddish sandy stone, something like crushed brick, scoriae, streams of lava, and pumice-stones. One could not mistake its volcanic origin. In some parts, slight curls of smoke emitted a sulphurous smell, proving that the internal fires had lost nothing of their expansive powers, though, having climbed a high acclivity, I could see no volcano for a radius of several miles. We know that in those Antarctic countries, James Ross found two craters, the Erebus and Terror, in full activity, on the 167th meridian, latitude 77° 32′. The vegetation of this desolate continent seemed to me much restricted. Some lichens lay upon the black rocks; some microscopic plants, rudimentary diatomas, a kind of cells placed between two quartz shells; long purple and scarlet weed, supported on little swimming bladders, which the breaking of the waves brought to the shore. These constituted the meagre flora of this region. The shore was strewn with molluscs, little mussels, and limpets. I also saw myriads of northern clios, one-and-a-quarter inches long, of which a whale would swallow a whole world at a mouthful; and some perfect sea-butterflies, animating the waters on the skirts of the shore.

There appeared on the high bottoms some coral shrubs, of the kind which, according to James Ross, live in the Antarctic seas to the depth of more than 1,000 yards. Then there were little kingfishers and starfish studding the soil. But where life abounded most was in the air. There thousands of birds fluttered and flew of all kinds, deafening us with their cries; others crowded the rock, looking at us as we passed by without fear, and pressing familiarly close by our feet. There were penguins, so agile in the water, heavy and awkward as they are on the ground; they were uttering harsh cries, a large assembly, sober in gesture, but extravagant in clamour. Albatrosses passed in the air, the expanse of their wings being at least four yards and a half, and justly called the vultures of the ocean; some gigantic petrels, and some damiers, a kind of small duck, the underpart of whose body is black and white; then there were a whole series of petrels, some whitish, with brown-bordered wings, others blue, peculiar to the Antarctic seas, and so oily, as I told Conseil, that the inhabitants of the Ferroe Islands had nothing to do before lighting them but to put a wick in.

“A little more,” said Conseil, “and they would be perfect lamps! After that, we cannot expect Nature to have previously furnished them with wicks!”

About half a mile farther on the soil was riddled with ruffs’ nests, a sort of laying-ground, out of which many birds were issuing. Captain Nemo had some hundreds hunted. They uttered a cry like the braying of an ass, were about the size of a goose, slate-colour on the body, white beneath, with a yellow line round their throats; they allowed themselves to be killed with a stone, never trying to escape. But the fog did not lift, and at eleven the sun had not yet shown itself. Its absence made me uneasy. Without it no observations were possible. How, then, could we decide whether we had reached the pole? When I rejoined Captain Nemo, I found him leaning on a piece of rock, silently watching the sky. He seemed impatient and vexed. But what was to be done? This rash and powerful man could not command the sun as he did the sea. Noon arrived without the orb of day showing itself for an instant. We could not even tell its position behind the curtain of fog; and soon the fog turned to snow.

“Till to-morrow,” said the Captain, quietly, and we returned to the Nautilus amid these atmospheric disturbances.

The tempest of snow continued till the next day. It was impossible to remain on the platform. From the saloon, where I was taking notes of incidents happening during this excursion to the polar continent, I could hear the cries of petrels and albatrosses sporting in the midst of this violent storm. The Nautilus did not remain motionless, but skirted the coast, advancing ten miles more to the south in the half-light left by the sun as it skirted the edge of the horizon. The next day, the 20th of March, the snow had ceased. The cold was a little greater, the thermometer showing 2° below zero. The fog was rising, and I hoped that that day our observations might be taken. Captain Nemo not having yet appeared, the boat took Conseil and myself to land. The soil was still of the same volcanic nature; everywhere were traces of lava, scoriae, and basalt; but the crater which had vomited them I could not see. Here, as lower down, this continent was alive with myriads of birds. But their rule was now divided with large troops of sea-mammals, looking at us with their soft eyes. There were several kinds of seals, some stretched on the earth, some on flakes of ice, many going in and out of the sea. They did not flee at our approach, never having had anything to do with man; and I reckoned that there were provisions there for hundreds of vessels.

“Sir,” said Conseil, “will you tell me the names of these creatures?”

“They are seals and morses.”

It was now eight in the morning. Four hours remained to us before the sun could be observed with advantage. I directed our steps towards a vast bay cut in the steep granite shore. There, I can aver that earth and ice were lost to sight by the numbers of sea-mammals covering them, and I involuntarily sought for old Proteus, the mythological shepherd who watched these immense flocks of Neptune. There were more seals than anything else, forming distinct groups, male and female, the father watching over his family, the mother suckling her little ones, some already strong enough to go a few steps. When they wished to change their place, they took little jumps, made by the contraction of their bodies, and helped awkwardly enough by their imperfect fin, which, as with the lamantin, their cousins, forms a perfect forearm. I should say that, in the water, which is their element—the spine of these creatures is flexible; with smooth and close skin and webbed feet—they swim admirably. In resting on the earth they take the most graceful attitudes. Thus the ancients, observing their soft and expressive looks, which cannot be surpassed by the most beautiful look a woman can give, their clear voluptuous eyes, their charming positions, and the poetry of their manners, metamorphosed them, the male into a triton and the female into a mermaid. I made Conseil notice the considerable development of the lobes of the brain in these interesting cetaceans. No mammal, except man, has such a quantity of brain matter; they are also capable of receiving a certain amount of education, are easily domesticated, and I think, with other naturalists, that if properly taught they would be of great service as fishing-dogs. The greater part of them slept on the rocks or on the sand. Amongst these seals, properly so called, which have no external ears (in which they differ from the otter, whose ears are prominent), I noticed several varieties of seals about three yards long, with a white coat, bulldog heads, armed with teeth in both jaws, four incisors at the top and four at the bottom, and two large canine teeth in the shape of a fleur-de-lis. Amongst them glided sea-elephants, a kind of seal, with short, flexible trunks. The giants of this species measured twenty feet round and ten yards and a half in length; but they did not move as we approached.

“These creatures are not dangerous?” asked Conseil.

“No; not unless you attack them. When they have to defend their young their rage is terrible, and it is not uncommon for them to break the fishing-boats to pieces.”

“They are quite right,” said Conseil.

“I do not say they are not.”

Two miles farther on we were stopped by the promontory which shelters the bay from the southerly winds. Beyond it we heard loud bellowings such as a troop of ruminants would produce.

“Good!” said Conseil; “a concert of bulls!”

“No; a concert of morses.”

“They are fighting!”

“They are either fighting or playing.”

We now began to climb the blackish rocks, amid unforeseen stumbles, and over stones which the ice made slippery. More than once I rolled over at the expense of my loins. Conseil, more prudent or more steady, did not stumble, and helped me up, saying:

“If, sir, you would have the kindness to take wider steps, you would preserve your equilibrium better.”

Arrived at the upper ridge of the promontory, I saw a vast white plain covered with morses. They were playing amongst themselves, and what we heard were bellowings of pleasure, not of anger.

As I passed these curious animals I could examine them leisurely, for they did not move. Their skins were thick and rugged, of a yellowish tint, approaching to red; their hair was short and scant. Some of them were four yards and a quarter long. Quieter and less timid than their cousins of the north, they did not, like them, place sentinels round the outskirts of their encampment. After examining this city of morses, I began to think of returning. It was eleven o’clock, and, if Captain Nemo found the conditions favourable for observations, I wished to be present at the operation. We followed a narrow pathway running along the summit of the steep shore. At half-past eleven we had reached the place where we landed. The boat had run aground, bringing the Captain. I saw him standing on a block of basalt, his instruments near him, his eyes fixed on the northern horizon, near which the sun was then describing a lengthened curve. I took my place beside him, and waited without speaking. Noon arrived, and, as before, the sun did not appear. It was a fatality. Observations were still wanting. If not accomplished to-morrow, we must give up all idea of taking any. We were indeed exactly at the 20th of March. To-morrow, the 21st, would be the equinox; the sun would disappear behind the horizon for six months, and with its disappearance the long polar night would begin. Since the September equinox it had emerged from the northern horizon, rising by lengthened spirals up to the 21st of December. At this period, the summer solstice of the northern regions, it had begun to descend; and to-morrow was to shed its last rays upon them. I communicated my fears and observations to Captain Nemo.

“You are right, M. Aronnax,” said he; “if to-morrow I cannot take the altitude of the sun, I shall not be able to do it for six months. But precisely because chance has led me into these seas on the 21st of March, my bearings will be easy to take, if at twelve we can see the sun.”

“Why, Captain?”

“Because then the orb of day described such lengthened curves that it is difficult to measure exactly its height above the horizon, and grave errors may be made with instruments.”

“What will you do then?”

“I shall only use my chronometer,” replied Captain Nemo. “If to-morrow, the 21st of March, the disc of the sun, allowing for refraction, is exactly cut by the northern horizon, it will show that I am at the South Pole.”

“Just so,” said I. “But this statement is not mathematically correct, because the equinox does not necessarily begin at noon.”

“Very likely, sir; but the error will not be a hundred yards and we do not want more. Till to-morrow, then!”

Captain Nemo returned on board. Conseil and I remained to survey the shore, observing and studying until five o’clock. Then I went to bed, not, however, without invoking, like the Indian, the favour of the radiant orb. The next day, the 21st of March, at five in the morning, I mounted the platform. I found Captain Nemo there.

“The weather is lightening a little,” said he. “I have some hope. After breakfast we will go on shore and choose a post for observation.”

That point settled, I sought Ned Land. I wanted to take him with me. But the obstinate Canadian refused, and I saw that his taciturnity and his bad humour grew day by day. After all, I was not sorry for his obstinacy under the circumstances. Indeed, there were too many seals on shore, and we ought not to lay such temptation in this unreflecting fisherman’s way. Breakfast over, we went on shore. The Nautilus had gone some miles further up in the night. It was a whole league from the coast, above which reared a sharp peak about five hundred yards high. The boat took with me Captain Nemo, two men of the crew, and the instruments, which consisted of a chronometer, a telescope, and a barometer. While crossing, I saw numerous whales belonging to the three kinds peculiar to the southern seas; the whale, or the English “right whale,” which has no dorsal fin; the “humpback,” with reeved chest and large, whitish fins, which, in spite of its name, do not form wings; and the fin-back, of a yellowish brown, the liveliest of all the cetacea. This powerful creature is heard a long way off when he throws to a great height columns of air and vapour, which look like whirlwinds of smoke. These different mammals were disporting themselves in troops in the quiet waters; and I could see that this basin of the Antarctic Pole serves as a place of refuge to the cetacea too closely tracked by the hunters. I also noticed large medusæ floating between the reeds.

At nine we landed; the sky was brightening, the clouds were flying to the south, and the fog seemed to be leaving the cold surface of the waters. Captain Nemo went towards the peak, which he doubtless meant to be his observatory. It was a painful ascent over the sharp lava and the pumice-stones, in an atmosphere often impregnated with a sulphurous smell from the smoking cracks. For a man unaccustomed to walk on land, the Captain climbed the steep slopes with an agility I never saw equalled and which a hunter would have envied. We were two hours getting to the summit of this peak, which was half porphyry and half basalt. From thence we looked upon a vast sea which, towards the north, distinctly traced its boundary line upon the sky. At our feet lay fields of dazzling whiteness. Over our heads a pale azure, free from fog. To the north the disc of the sun seemed like a ball of fire, already horned by the cutting of the horizon. From the bosom of the water rose sheaves of liquid jets by hundreds. In the distance lay the Nautilus like a cetacean asleep on the water. Behind us, to the south and east, an immense country and a chaotic heap of rocks and ice, the limits of which were not visible. On arriving at the summit Captain Nemo carefully took the mean height of the barometer, for he would have to consider that in taking his observations. At a quarter to twelve the sun, then seen only by refraction, looked like a golden disc shedding its last rays upon this deserted continent and seas which never man had yet ploughed. Captain Nemo, furnished with a lenticular glass which, by means of a mirror, corrected the refraction, watched the orb sinking below the horizon by degrees, following a lengthened diagonal. I held the chronometer. My heart beat fast. If the disappearance of the half-disc of the sun coincided with twelve o’clock on the chronometer, we were at the pole itself.

“Twelve!” I exclaimed.

“The South Pole!” replied Captain Nemo, in a grave voice, handing me the glass, which showed the orb cut in exactly equal parts by the horizon.

I looked at the last rays crowning the peak, and the shadows mounting by degrees up its slopes. At that moment Captain Nemo, resting with his hand on my shoulder, said:

“I, Captain Nemo, on this 21st day of March, 1868, have reached the South Pole on the ninetieth degree; and I take possession of this part of the globe, equal to one-sixth of the known continents.”

“In whose name, Captain?”

“In my own, sir!”

Saying which, Captain Nemo unfurled a black banner, bearing an “N” in gold quartered on its bunting. Then, turning towards the orb of day, whose last rays lapped the horizon of the sea, he exclaimed:

“Adieu, sun! Disappear, thou radiant orb! rest beneath this open sea, and let a night of six months spread its shadows over my new domains!”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sinanas diatomas

By Ripley Cook on @iguanodont

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Sinanas diatomas

Status: Extinct

First Described: 1980

Described By: Yeh

Classification: Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Anseriformes, Anseres, Anatoidea, Anatidae, Thambetochenini

Sinanas is a rather mysterious prehistoric duck, known from fairly limited material found somewhere in Lunqu, Shandong Province, China - unfortunately, the original location is lost. It lived at some point in the middle Miocene, between 16 and 12 million years ago, in the Langhian to Serravallian ages. Since it’s only known from scraps, it’s difficult to really piece together anything about this duck - it could belong to any duck group.

Buy the author a coffee: http://ko-fi.com/kulindadromeus

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinanas

Mlíkovsky, J., P. Švec. 1986. Review of the Tertiary Waterfowl (Aves: Anseridae) of Asia. Vest. cs. Spolec. zool. 50: 249 - 272.

#sinanas#sinanas diatomas#bird#duck#dinosaur#birblr#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#dínosaurio#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍恐龙#динозавр#dinosaurio

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Diatoma marinum on Ceramium rubrum, Anna Atkins, ca. 1853, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Photography

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Size: Image: 25.3 x 20 cm (9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Medium: Cyanotype

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/291558

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

çok konuşuyorduk ve bilgisizdik.

marcus tullius cicero - diatoma

#kitapkurdu#literary#edebiyat#poems#editorial#friedrich nietzche#society#blogger#book#lifestyle#cicero#kitap kurdu#kitaplar#kitaplık#kitap#litarature#literary quotes#literatura#literature#felsefe klübü#felsefe parçaları#felsefe notları#klasik alman felsefesi#felsefe#free books#bookworm#books#bookshelf#book quotes

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cara Budidaya Cacing Tubifex

Cara budidaya cacing tubifex ialah langkah memiara cacing sutra untuk hasilkan jumlah yang semakin banyak buat untuk menjadikan sumber makanan alami larva ikan. dengan nilai nutrisi yang tinggi cacing sutra benar-benar disukai pemberbudidaya sebagai salah satunya pilihan khusus pakan larva ikan.

Cacing sutera (Tubifex) sering disebutkan cacing rambut atau cacing darah sebagai cacing kecil seukur rambut warna kemerahan dengan panjang sekitaran 1-3 cm, Cacing rambut sebagai salah satunya alternative pakan alami yang bisa diputuskan untuk memberikan makan ikan babak larva sampai benih atau untuk ikan hias.

Cacing sutera umumnya didapat dengan menambang/ambilnya dari sungai.Cara budidaya cacing sutera pada umumnya bisa dilaksanakan pada media lumpur yang digabung dengan kotaran ayam dan bekatul. Sepanjang proses budidaya, media dialiri air dengan debet sekitaran 3 ltr per detik.

Panen cacing sutera bisa dilaksanakan satu minggu sampai dua minggu sesudah ditanamkan. Bila didiamkan kelamaan, karena itu jumlah cacing sutera akan menyusut kembali, karena dengan alami terjadi kompetisi antar-cacing tersebut.Hasil produksi dari budidaya cacing sutera capai 2x semakin banyak dibanding di komunitas aslinya. Jika budidaya dilaksanakan di tepi sungai, karena itu produksi semakin lebih banyak.

Cara budidaya cacing sutra

Persiapan Bibit cacing sutra

Bibit dapat diperoleh dari toko ikan hias atau diambil dari alam, Catatan : Seharusnya bibit cacing di karantina dulu karena ditakuti bawa patogen.

Persiapan Media cacing sutra

Media perubahan dibikin sebagai genangan lumpur sama ukuran 1 x 2 mtr. yang diperlengkapi aliran penghasilan dan pengeluaran air. Setiap genangan dibikin petakan petakan kecil ukuran 20 x 20 cm dengan tinggi bilikan atau tanggul 10 cm, antara bilikan dikasih lubang berdiameter 1 cm.

Tempat di pupuk dengan dedak lembut atau ampas tahu sekitar 200 - 250 gram/M2 atau mungkin dengan pupuk kandang sekitar 300 gram/ M2.

Cara pembuatan pupuknya

Siapkan kotoran ayam, jemur 6 jam. Siapkan bakteri EM4 untuk peragian kotoran ayam itu. Mencari di toko pertanian atau toko peternakan atau balai peternakan.

Aktifkan dahulu bakterinya. Triknya ¼ sendok makan gula pasir + 4ml EM4 + dalam 300ml air terus biarkan kurang lebih 2 jam. Campur cairan itu ke 10kg kotoran ayam yang telah dijemur barusan aduk sampai rata. Seterusnya masukan ke tempat yang tertutup rapat sepanjang 5 hari.

Kenapa harus difermentasi?

Karenanya fermetasi karena itu kandungan N-organik dan C-organik akan naik sampai 2 kali lipat

Fermentasi Kolam cacing sutra

Tempat dipendam dengan air dengan tinggi 5 cm sepanjang 3-4 hari.

Penebaran Bibit cacing sutra

Sepanjang Proses Budidaya tempat dialiri air dengan debet 2-5 Liter / detik

Tahapan Kerja Budidaya Cacing Sutra

Berikut tahapan kerja yang perlu dijalankan dalam pembudidayaan cacing sutra:

* Tempat eksperimen berbentuk kolam tanah ber ukuran 8 x 1,5 m dengan kedalaman 30 cm.

* Dasar kolam eksperimen berisi sedikit lumpur.Jika matahari cukup terik, jemur kolam minimal satu hari. Bertepatan dengan itu, kolam dibikin bersih dari rumput atau hewan lain, seperti keong mas atau kijing.

* Pipa Air Keluar (Pipa Pengeluaran /Toko) dilihat kemampuannya dan yakinkan berperan secara baik. dibuat dari paralon berdia- mtr. 2 inch dengan panjang sekitaran 15 cm.

* Selesai pengeringan dan penjemuran, upayakan keadaan dasar kolam bebas dari batu-batuan dan beberapa benda keras yang lain. Sebaiknya konstruksi tanah dasar kolam relatif datar atau mungkin tidak bergelombang.

* Dasar kolam berisi lumpur lembut yang dari aliran atau kolam yang dipandang banyak terkandung bahan organik sampai ketebalan capai 10 cm.

* Masukan kotoran ayam kering sekitar tiga karung, selanjutnya tebar secara rata dan seterusnya diaduk-aduk dengan kaki.

* Sesudah dipandang datar, genangi kolam itu sampai kedalaman air maksimal 5 cm, sama sesuai panjang pipa buangan.

* Pasang atap peneduh untuk menahan tumbuhnya lumut di kolam.

* Kolam yang telah tergenangi air itu didiamkan sepanjang 1 minggu supaya kandungan gas lenyap.

* Tebarkan 0,5 ltr gumpalan cacing sutra dengan menyiraminya lebih dulu dalam baskom supaya gumpalannya bubar.

* Selanjutnya mengatur saluran air dengan pipa paralon memiliki ukuran 2/3 inch.

* Tempat budidaya bisa berbentuk parit beton atau tempat yang dilapis plastik, lebar 0,5 mtr..

* Pakan cacing sutra berbentuk kombinasi kotoran ayam fresh 50% dan lumpur kolam 50%. Tinggi media 5 cm.

* Pemupukan ulangi dengan menambah kotoran ayam sekitar 9% dari volume awalnya, dilaksanakan tiap minggu.

* Media dialiri air irigasi, dengan debet air 900 ml/menit.

* Benih cacing rambut disebar satu hari setelah media kultur dialiri air, yakni sekitar 2 gr/ m2.

* Karena cacing sutra terhitung makhluk hidup, tentu saja cacing sutra itu perlu makan. Makanannya ialah bahan organik yang bersatu dengan lumpur atau sedimen di dasar perairan.

* Panen cacing sutera dilaksanakan sesudah beberapa minggu dan beruntun dapat dipanen tiap dua minggusekali.

* Langkah pemanenan dengan memakai serok lembut/halus. Cacing sutera masih bersatu dengan media budidaya ditempatkan di dalam ember atau bak yang diisi air, anggap -kira 1 cm di atas media. Ember ditutup sampai sisi dalam jadi gelap dan didiamkan sepanjang enam jam. cacing menggerombol di atas media diambil dengan tangan.

* Dengan langkah ini didapatkan cacing sutera sekitar 30 - 50 gr/m2 per dua minggu.

* Untuk memperoleh cacing rambut yang cukup dan berkaitan, panjang parit perlu direncanakan sesuai kepentingan sehari-harinya.

Pakan alami dapat juga menjadi hama, berikut adala penanganan beberapa jenis pakan alami yang tepat :

* Untuk mencegah berkembangnya hama dan pengganggu, media dibubuhi dengan larutan tembaga sulfat atau trusi (CuSO4) sekitar 1,5 mg/l. Selain itu air baru yang hendak ditambahkan harus disaring dengan kain saringan 15 mikron.

* Hama yang kerap mengusik ialah Brachionus, Copepoda, dan lain-lain. Untuk memberantas hama itu dalam wadah 60 liter atau 1 ton bisa dilepas ikan mujair 4-5 ekor.

* Moina yang berkerumun di permukaan memperlihatkan kualitas media menurun.

* Cendawan yang bertambah di hari ketiga. Jika cendawan telah banyak, budidaya disetop dan bak dikeringkan.

* Jika ada Brachionus dan Ciliata, budidaya disetop dan kolam dicuci dengan larutan klorin 100 mililiter/m3 dan dikeringkan.

* Hama yang mengusik, diantaranya : semut, cecak, dan tikus. Penangkalan dilaksanakan dengan memolesi tempat dengan minyak mesin (Oli).

* Chlorella dipanen dari perairan masal 60 l/ 1 ton dan dapat segera diumpankan pada ikan.

* Langkah pemanenan langsung diumpankan dan diambil dari budidaya masal 1 ton.

* Pemanenan memakai alat penyaring pasir yang dibuat dari ember plastik 60 l, yang sisi bawahnya terpasang pipa PVC (d = 5 cm) yang berlubang-lubang kecil sebagai saluran buangan air.

* Ember diisi kerikil yang memiliki ukuran 2-5 mm dan pasir (d = 0,2 mm, koefisien keseragaman 1,80). Tinggi susunan pasir ± 4/5 sisi dari jumlahnya semua isi pasir dan kerikil, dan ± 8 cm di permukaan pasir dibikin lubang perluapan.

* Diatomae dari bak perawatan ditempatkan ke bak penyaring pasir dengan pompa air dan akan tersaring oleh susunan pasir.

* Dari lubang pengurasan dipompakan air yang hendak tembus susunan kerikil dan pasir dan menumpahkan air dan Diatomae lewat lubang peluapan selanjutnya dimuat dalam sebuah tempat.

* Panen Brachionus dilaksanakan di saat kepadatannya capai 100 ekor/ml dalam periode waktu 5-7 hari atau dua minggu selanjutnya dengan kepadatan ekor / ml.

* Panen beberapa bisa dilaksanakan sepanjang 45 hari, di mana 1-2 jam saat sebelum penangkapan, air diaduk-aduk , selanjutnya didiamkan. Brachionus yang bergabung di atas diseser dengan kain nilon no 200 / kain plankton 60 mikron.

* Panen keseluruhan dilaksanakan dengan mengisap air dengan selang plastik dan disisakan 1/3 sisi selanjutnya disaring dengan kain nilon 200 atau kain plankton 60 mikron.

* Hasil tangkapan dibersihkan sampai bersih dan dapat digunakan.

Usaha Pembesaran Cacing Sutra

* Panen dilaksanakan pada usia dua minggu dan ukuran Artemia capai 8 mm. Saat sebelum penangkapan, aerasi disetop sepanjang 30 menit, lalu Artemia yang naik ke atas diserok dengan seser kain lembut.

* Artemia dapat segera digunakan atau diletakkan dalam freezer.

* Penangkapan dilaksanakan dengan manfaatkan kotak keping penyaring yang diperlengkapi saringan 200 mikron pada ujung pipa peluapannya. Nauplius diambil sesudah yang terkumpul dengan jumlah banyak.

* Langkah penangkapan sama dengan produksi nauplius

* Telur dibersihkan sampai bersih dan dipendam 1 jam dalam larutan garam 115 permil, dikeringkan sepanjang 24 jam, derajat C.

* Penyimpanan dilaksanakan di kantong plastik yang diisi gas N2/kaleng hampa udara.

* Infusoria dipanen dalam kurun waktu satu minggu, diikuti dengan peralihan warna media jadi keputih-putihan.

* Pemanenan dilaksanakan dengan hentikan aerasi, penghisapan dan filtrasi media dengan saringan ukuran mikron dan mikron untuk pisahkan dari jentik-jentik nyamuk.

* Panen dilaksanakan sesudah 10 hari dengan mengambilnya dengan tangan dan lumpurnya, selanjutnya dicuci.

* Panen keseluruhan dilaksanakan jika keadaan tanah dan media tidak bisa sediakan makanan kembali.

* Pemanenan dilaksanakan bila larva ulat berusia dua bulan dan memiliki ukuran 1,5-2 cm. Triknya dengan memakai alat penyaring/ayakan dengan cukup besar.

* Hasil panen phytoplankton dapat segera digunakan atau diletakkan berbentuk basah/kering, sesudah dikonsentratkan dengan plankton net, plate separate, atau centrifuge.

* Penyimpanan stock murni phytoplankton dilaksanakan dalam media cair/supaya dan diletakkan dalam lemari pendingin dengan periode taruh 1 bulan.

Demikian artikel tentang cacing sutra, semoga bermanfaat.

0 notes

Text

💗 vday shenanigans

#from vday exchange my friends n i did last year!! i felt like coloring it this morning#diatoma#oc#valentines day#my art#their outfits were coordinated by soranker HEEHEE#was debating between drawing vday fanart for certain charas i like but decided hm actually ill post my ocs :]

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2pcs Diatoma Soap Dish Pad Mat Antibakterielle Feuchtigkeitsbeständige Soap Preis : 12.05 € jetzt kaufen Artikelmerkmale Artikelzustand: Neu: Neuer, unbenutzter und unbeschädigter Artikel in nicht geöffneter Originalverpackung (soweit eine …

#body cream#body creme#body pflegecreme#Bodylotion#bodylotion männer#enthaarungscreme#enthaarungspads#enthaarungswachs#Körpercreme#Körperlotion#Körperpflege

0 notes

Text

Peixes De Profundidade

Peixes De Profundidade

Peixes de profundidade são peixes que vivem na escuridão abaixo das Águas de superfície iluminadas pelo sol, ou seja, abaixo da zona epipelágica ou fótica do mar. Outros peixes de profundidade incluem o peixe-lanterna, tubarão-COO, cerdas , Tamboril , viperfish e algumas espécies de eelpout.

Apenas cerca de 2% das espécies marinhas conhecidas habitam o ambiente pelágico. Isso significa que eles vivem na coluna de água, em oposição aos organismos bentônicos que vivem dentro ou no fundo do mar. 1 organismos de profundidade habitam geralmente zonas de bathypelagic (1000-4000m de profundidade) e abyssopelagic (4000-6000m de profundidade).

No entanto, as características dos organismos de profundidade, como a bioluminescência, também podem ser vistas na zona mesopelágica (200-1000m de profundidade). A zona mesopelágica é a zona disfótica, o que significa que a luz é mínima, mas ainda mensurável. A camada mínima de oxigênio existe em algum lugar entre uma profundidade de 700m e 1000m de profundidade, dependendo do lugar no oceano. Esta área também é onde os nutrientes são mais abundantes.

As zonas batipelágicas e abissopelágicas são aphóticas, o que significa que nenhuma luz penetra nesta área do oceano. Estas zonas representam cerca de 75% do espaço oceânico habitável.

youtube

A zona epipelágica (0-200m) é a área onde a luz penetra a água e a fotossíntese ocorre. Esta também é conhecida como a zona fótica. Como isso normalmente se estende apenas algumas centenas de metros abaixo da água, o mar profundo, cerca de 90% do volume do oceano, está na escuridão.

O fundo do mar também é um ambiente extremamente hostil, com temperaturas que raramente ultrapassam os 3 °C (37.4 °F) e cair tão baixo como -1.8 °C (28.76 °F) (com a exceção dos ecossistemas das fontes hidrotermais que pode exceder os 350 °C, ou a 662 °F), baixos níveis de oxigênio, e pressões entre 20 e 1.000 atmosferas (entre 2 e 100 megapascals ).

Diagrama de escala das camadas da zona pelágica

No oceano profundo, as águas se estendem muito abaixo da zona epipelágica, e suportam tipos muito diferentes de peixes pelágicos adaptados para viver nessas zonas mais profundas.

Em águas profundas, a neve Marinha é um banho contínuo de detritos orgânicos que caem das camadas superiores da coluna de água. Sua origem está em atividades dentro da zona fótica produtiva neve marinha inclui plâncton morto ou moribundo, protistas( diatomas), matéria fecal, areia, fuligem e outras poeiras inorgânicas. Os" flocos de neve " crescem ao longo do tempo e podem atingir vários centímetros de diâmetro, viajando durante semanas antes de chegar ao fundo do oceano.

No entanto, a maioria dos componentes orgânicos da neve marinha são consumidos por micróbios , zooplâncton e outros animais que alimentam filtros nos primeiros 1.000 metros de sua viagem, ou seja, dentro da zona epipelágica. Desta forma, a neve marinha pode ser considerada a base de ecossistemas mesopelágicos e bentónicos de profundidade : como a luz solar não pode alcançá-los, os organismos de profundidade dependem fortemente da neve marinha como fonte de energia.

Alguns mar profundo pelágicos grupos, tais como o lanternfish , ridgehead , marinha hatchetfish , e lightfish famílias são muitas vezes apelidados de pseudoceanic porque, em vez de ter uma distribuição uniforme em águas abertas, elas ocorrem em um número significativamente maior abundância em torno estruturais oásis, nomeadamente os montes submarinos e sobre continental pistas que O fenômeno é explicado pelo da mesma forma, a abundância de espécies de presas que também são atraídos para as estruturas.

A pressão hidrostática Aumenta 1 atmosfera a cada 10 metros de profundidade. organismos do mar profundo têm a mesma pressão dentro de seus corpos que é exercida sobre eles do lado de fora, de modo que eles não são esmagados pela pressão extrema. Sua alta pressão interna, no entanto, resulta na fluidez reduzida de suas membranas porque as moléculas são espremidas juntas.

A fluidez nas membranas celulares aumenta a eficiência das funções biológicas, o mais importante é a produção de proteínas, por isso os organismos adaptaram-se a esta circunstância, aumentando a proporção de ácidos gordos insaturados nos lípidos das membranas celulares.

além das diferenças de pressão interna, estes organismos desenvolveram um equilíbrio diferente entre as suas reacções metabólicas dos organismos que vivem na zona epipelágica. David Wharton, author of Life at the Limits: Organisms in Extreme Environments, notes "Biochemical reactions are accompanied by changes in volume. Se uma reacção resultar num aumento de volume, será inibida pela pressão, enquanto que, se estiver associada a uma diminuição de volume, será potenciada". 7 Isto significa que os seus processos metabólicos devem, em última análise, diminuir o volume do organismo em algum grau.

Os seres humanos raramente encontram tubarões esfolados vivos, então eles representam pouco perigo (embora os cientistas acidentalmente se cortaram examinando seus dentes).

A maioria dos peixes que evoluíram neste ambiente duro não são capazes de sobreviver em condições laboratoriais, e as tentativas de mantê-los em cativeiro levaram à sua morte. Os organismos de profundidade contêm espaços cheios de gás (vacúolos). 9 gás é comprimido sob alta pressão e se expande sob baixa pressão. Por causa disso, estes organismos têm sido conhecidos por explodir se eles vêm à superfície.

Um diagrama anotado das características externas básicas de uma lagartixa-de-abissal e medições de comprimento padrão.

Gigantactis é um peixe de profundidade com uma barbatana dorsal cujo primeiro filamento se tornou muito longo e é inclinado com uma isca fotóforo bioluminescente.

O atum patudo cruza a zona epipelágica à noite e a zona mesopelágica durante o dia.

Os peixes das profundezas do mar evoluíram várias adaptações para sobreviver nesta região. Uma vez que muitos destes peixes vivem em regiões onde não há iluminação natural , eles não podem confiar apenas na sua visão para localizar a presa e companheiros e evitar predadores; peixes do mar profundo evoluíram de forma adequada para a extrema sub-fótica região em que vivem. Muitos desses organismos são cegos e dependem de seus outros sentidos, tais como sensibilidades a mudanças na pressão e olfato locais, para pegar seus alimentos e evitar ser pego.

Aqueles que não são cegos têm olhos grandes e sensíveis que podem usar luz bioluminescente. Estes olhos podem ser 100 vezes mais sensíveis à luz do que os olhos humanos. Além disso, para evitar a predação, muitas espécies são escuras para se misturarem com o seu ambiente.

Muitos peixes de profundidade são bioluminescentes, com olhos extremamente grandes adaptados à escuridão. Organismos bioluminescentes são capazes de produzir luz biologicamente através da agitação de moléculas de luciferina, que então produzem luz. Este processo deve ser feito na presença de oxigênio. Estes organismos são comuns na região mesopelágica e abaixo (200m e abaixo). Mais de 50% dos peixes de profundidade, bem como algumas espécies de camarão e lulas, são capazes de bioluminescência.

Cerca de 80% destes organismos possuem células glandulares produtoras de fotóforos-luz que contêm bactérias luminosas delimitadas por colorações escuras. Alguns destes fotóforos contêm lentes, muito semelhantes às dos olhos humanos, que podem intensificar ou diminuir a emanação da luz. A capacidade de produzir luz requer apenas 1% da energia do organismo e tem muitos propósitos: é usado para procurar comida e atrair presas, como o tamboril; reivindicar território através da Patrulha; comunicar e encontrar um companheiro, e distrair ou temporariamente cegos predadores para escapar.

Além disso, no mesopelágico onde alguma luz ainda penetra, alguns organismos camuflam-se de predadores abaixo deles, iluminando suas barrigas para combinar com a cor e intensidade da luz de cima para que nenhuma sombra seja lançada. Esta tática é conhecida como contra-iluminação.

O ciclo de vida dos peixes de profundidade pode ser exclusivamente águas profundas, embora algumas espécies nascem em águas mais rasas e afundam-se ao amadurecer. Independentemente da profundidade onde os ovos e larvas residem, eles são tipicamente pelágicos.

Este estilo de vida planktonic-drifting-requer flutuabilidade neutra. A fim de manter isso, os ovos e larvas muitas vezes contêm gotículas de óleo em seu plasma.

youtube

Quando estes organismos estão em seu estado de maturação completa, eles precisam de outras adaptações para manter suas posições na coluna de água. Em geral, a densidade da água provoca a elevação — o aspecto da flutuabilidade que faz os organismos flutuarem. Para neutralizar isso, a densidade de um organismo deve ser maior do que a da água circundante. A maioria dos tecidos animais são mais densos que a água, então eles devem encontrar um equilíbrio para fazê-los flutuar.

Muitos organismos desenvolvem bexigas de banho (cavidades de gás) para manter-se à tona, mas devido à alta pressão do seu ambiente, peixes de profundidade geralmente não têm este órgão. Em vez disso, exibem estruturas semelhantes aos hydrofoils, a fim de fornecer sustentação hidrodinâmica.

Também se descobriu que quanto mais profundo um peixe vive, mais geleia-como a sua carne e mais mínima a sua estrutura óssea. Reduzem a densidade dos tecidos através de um elevado teor de gordura, a redução do peso do esqueleto — realizada através de reduções de tamanho, espessura e teor mineral — e a acumulação de água torna-os mais lentos e menos ágeis do que os peixes de superfície.

0 notes

Photo

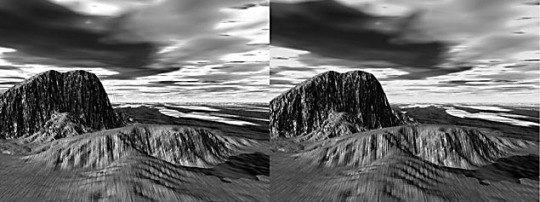

Diatoma, an illustration created by Gerald Marks for the book Virtual Reality by H. P. Newquist, Scholastic Publications, 1995. A photo of a microscopic diatom was used to seed the basic shape of the mountains [source]

0 notes

Photo

i got custom jewelry inspired by my oc Mobie and i loved how it turned out so much TT___TT so i drew him wearing it! made by geomi333 on ig <3

#my art#oc#diatoma#jewelry#illustration#I GOT A NECKLACE BY THEM TOO INSPIRED BY VALKYRIE... ITS SO CUTE MAN#when i have time hopefully i can draw an illust for the necklace too...

63 notes

·

View notes