Text

Tongues of the Moon, Philip Jose Farmer

Broward sat down by Ingrid Nashdoi. She was a short dark and petite woman of about thirty-three. Not very good-looking but, usually, witty and vivacious. Now, she stared at the floor, her face frozen.

"I'm sorry about Jim," he said. "But we don't have time to grieve now. Later, perhaps."

She did not look at him but replied in a low halting voice. "He may have been dead before the war started. I never even got to say goodbye to him. You know what that means. What it probably did mean."

"I don't think they got anything out of him. Otherwise, you and I would have been arrested, too."

He jerked his head towards Scone and said, "He doesn't know you're one of us. I want him to think you're a candidate for the Nationalists. After this struggle with the Russ is over, we may need someone who can report on him. Think you can do it?"

She nodded her head, and Broward returned to Scone. "She hates the Russians," he said. "You know they took her husband away. She doesn't know why. But she hates Ivan's guts."

"Good. Ah, here we go."

After the destroyer had berthed at Clavius, and the three entered the base, events went swiftly if not smoothly. Scone talked to the entire personnel over the IP, told them what had happened. Then he went to his office and issued orders to have the arsenal cleaned out of all portable weapons. These were transferred to the four destroyers the Russians had assigned to Clavius as a token force.

Broward then called in his four Athenians and Scone, his five Nationalists. The situation was explained to them, and they were informed of what was expected of them. Even Broward was startled, but didn't protest.

After the weapons had been placed in the destroyers, Scone ordered the military into his office one at a time. And, one at a time, they were disarmed and escorted by another door to the arsenal and locked in. Three of the soldiers asked to join Scone, and he accepted two. Several protested furiously and denounced Scone as a traitor.

Then, Scone had the civilians assembled in the large auditorium. (Technically, all personnel were in the military, but the scientists were only used in that capacity during emergencies.) Here, he told them what he had done, what he planned to do—except for one thing—and asked them if they wished to enlist. Again, he got a violent demonstration from some and sullen silence from others. These were locked up in the arsenal.

The others were sworn in, except for one man, Whiteside. Broward pointed him out as an agent and informer for both the Russians and Chinese. Scone admitted that he had not known about the triple-dealer, but he took Broward's word and had Whiteside locked up, too.

Then, the radios of the two scout ships were smashed, and the prisoners marched out and jammed into them. Scone told them they were free to fly to the Russian base. Within a few minutes, the scouts hurtled away from Clavius towards the north.

"But, Colonel," said Broward, "they can't give the identifying code to the Russians. They'll be shot down."

"They are traitors; they prefer the Russky to us. Better for us if they are shot down. They'll not fight for Ivan."

Broward did not have much appetite when he sat down to eat and to listen to Scone's detailing of his plan.

"The Zemlya," he said, "has everything we need to sustain us here. And to clothe the Earth with vegetation and replace her animal life in the distant future when the radiation is low enough for us to return. Her deepfreeze tanks contain seeds and plants of thousands of different species of vegetation. They also hold, in suspended animation, the bodies of cattle, sheep, horses, rabbits, dogs, cats, fowl, birds, useful insects and worms. The original intention was to reanimate these and use them on any Terrestrial-type planet the Zemlya might find.

"Now, our bases here are self-sustaining. But, when the time comes to return to Earth, we must have vegetation and animals. Otherwise, what's the use?

"So, whoever holds the Zemlya holds the key to the future. We must be the ones who hold that key. With it, we can bargain; the Russians and the Chinese will have to agree to independence if they want to share in the seeds and livestock."

"What if the Zemlya's commander chooses destruction of his vessel rather than surrender?" said Broward. "Then, all of humanity will be robbed. We'll have no future."

"I have a plan to get us aboard the Zemlya without violence."

An hour later, the four USAF destroyers accelerated outwards towards Earth. Their radar had picked up the Zemlya; it also had detected five other Unidentified Space Objects. These were the size of their own craft.

Abruptly, the Zemlya radioed that it was being attacked. Then, silence. No answer to the requests from Eratosthenes for more information.

Scone had no doubt about the attackers' identity. "The Axis leaders wouldn't have stayed on Earth to die," he said. "They'll be on their way to their big base on Mars. Or, more likely, they have the same idea as us. Capture the Zemlya."

"And if they do?" said Broward.

"We take it from them."

The four vessels continued to accelerate in the great curve which would take them out away from the Zemlya and then would bring them around towards the Moon again. Their path was computed to swing them around so they would come up behind the interstellar ship and overtake it. Though the titanic globe was capable of eventually achieving far greater speeds than the destroyers, it was proceeding at a comparatively slow velocity. This speed was determined by the orbit around the Moon into which the Zemlya intended to slip.

In ten hours, the USAF complement had curved around and were about 10,000 kilometers from the Zemlya. Their speed was approximately 20,000 kilometers an hour at this point, but they were decelerating. The Moon was bulking larger; ahead of them, visible by the eye, were two steady gleams. The Zemlya and the only Axis vessel which had not been blown to bits or sliced to fragments. According to the Zemlya, which was again in contact with the Russian base, the Axis ship had been cut in two by a tongue from Zemlya.

But the interstellar ship was now defenseless. It had launched every missile and anti-missile in its arsenal. And the fuel for the tongue-generators was exhausted.

"Furthermore," said Shaposhnikov, commander of the Zemlya, "new USO has been picked up on the radar. Four coming in from Earth. If these are also Axis, then the Zemlya has only two choices. Surrender. Or destroy itself."

"There is nothing we can do," replied Eratosthenes. "But we do not think those USO are Axis. We detected four destroyer-sized objects leaving the vicinity of the USAF base, and we asked them for identification. They did not answer, but we have reason to believe they are North American."

"Perhaps they are coming to our rescue," suggested Shaposhnikov.

"They left before anyone knew you were being attacked. Besides, they had no orders from us."

"What do I do?" said Shaposhnikov.

Scone, who had tapped into the tight laser beam, broke it up by sending random pulses into it. The Zemlya discontinued its beam, and Scone then sent them a message through a pulsed tongue which the Russian base could tap into only through a wild chance.

After transmitting the proper code identification, Scone said, "Don't renew contact with Eratosthenes. It is held by the Axis. They're trying to lure you close enough to grab you. We escaped the destruction of our base. Let me aboard where we can confer about our next step. Perhaps, we may have to go to Alpha Centaurus with you."

For several minutes, the Zemlya did not answer. Shaposhnikov must have been unnerved. Undoubtedly, he was in a quandary. In any case, he could not prevent the strangers from approaching. If they were Axis, they had him at their mercy.

Such must have been his reasoning. He replied, "Come ahead."

By then, the USAF dishes had matched their speeds to that of the Zemlya's. From a distance of only a kilometer, the sphere looked like a small Earth. It even had the continents painted on the surface, though the effect was spoiled by the big Russian letters painted on the Pacific Ocean.

Scone gave a lateral thrust to his vessel, and it nudged gently into the enormous landing-port of the sphere. Within five minutes, his crew of ten were in the control room.

Scone did not waste any time. He drew his gun; his men followed suit; he told Shaposhnikov what he meant to do. The Russian, a tall thin man of about fifty, seemed numbed. Perhaps, too many catastrophes had happened in too short a time. The death of Earth, the attack by the Axis ships, and, now, totally unexpected, this. The world was coming to an end in too many shapes and too swiftly.

Scone cleared the control room of all Zemlya personnel except the commander. The others were locked up with the forty-odd men and women who were surprised at their posts by the Americans.

Scone ordered Shaposhnikov to set up orders to the navigational computer for a new path. This one would send the Zemlya at the maximum acceleration endurable by the personnel towards a point in the south polar region near Clavius. When the Zemlya reached the proper distance, it would begin a deceleration equally taxing which would bring it to a halt approximately half a kilometer above the surface at the indicated point.

Shaposhnikov, speaking disjointedly like a man coming up out of a nightmare, protested that the Zemlya was not built to stand such a strain. Moreover, if Scone succeeded in his plan to hide the great globe at the bottom of a chasm under an overhang.... Well, he could only predict that the lower half of the Zemlya would be crushed under the weight—even with the Moon's weak gravity.

"That won't harm the animal tanks," said Scone. "They're in the upper levels. Do as I say. If you don't, I'll shoot you and set up the computer myself."

"You are mad," said Shaposhnikov. "But I will do my best to get us down safely. If this were ordinary war, if we weren't man's—Earth's—last hope, I would tell you to go ahead, shoot. But...."

Ingrid Nashdoi, standing beside Broward, whispered in a trembling voice, "The Russian is right. He is mad. It's too great a gamble. If we lose, then everybody loses."

"Exactly what Scone is betting on," murmured Broward. "He knows the Russians and Chinese know it, too. Like you, I'm scared. If I could have foreseen what he was going to do, I think I'd have put a bullet in him back at Eratosthenes. But it's too late to back out now. We go along with him no matter what."

The voyage from the Moon and the capture of the Zemlya had taken twelve hours. Now, with the Zemlya's mighty drive applied—and the four destroyers riding in the landing-port—the voyage back took three hours. During this time, the Russian base sent messages. Scone refused to answer. He intended to tell all the Moon his plans but not until the Zemlya was close to the end of its path. When the globe was a thousand kilometers from the surface, and decelerating with the force of 3g's, he and his men returned to the destroyers. All except three, who remained with Shaposhnikov.

The destroyers streaked ahead of the Zemlya towards an entrance to a narrow canyon. This led downwards to a chasm where Scone intended to place the Zemlya beneath a giant overhang.

But, as the four sped towards the opening two crags, their radar picked up four objects coming over close to the mountains to the north. A battlebird and three destroyers. Scone knew that the Russians had another big craft and three more destroyers available. But they probably did not want to send them out, too, and leave the base comparatively defenseless.

He at once radioed the commander of the Lermontov and told him what was going on.

"We declare independence, a return to Nationalism," he concluded. "And we call on the other bases to do the same."

The commander roared, "Unless you surrender at once, we turn on the bonephones! And you will writhe in pain until you die, you American swine!"

"Do that little thing," said Scone, and he laughed.

He switched on the communication beams linking the four ships and said, "Hang on for a minute or two, men. Then, it'll be all over. For us and for them."

Two minutes later, the pain began. A stroke of heat like lightning that seemed to sear the brains in their skulls. They screamed, all except Scone, who grew pale and clutched the edge of the control panel. But the dishes were, for the next two minutes, on automatic, unaffected by their pilots' condition.

And then, just as suddenly as it had started, the pain died. They were left shaking and sick, but they knew they would not feel that unbearable agony again.

"Flutter your craft as if it's going out of control," said Scone. "Make it seem we're crashing into the entrance to the canyon."

Scone himself put the lead destroyer through the simulation of a craft with a pain-crazed pilot at the controls. The others followed his maneuvers, and they slipped into the canyon.

From over the top of the cliff to their left rose a glare that would have been intolerable if the plastic over the portholes had not automatically polarized to dim the brightness.

Broward, looking through a screen which showed the view to the rear, cried out. Not because of the light from the atomic bomb which had exploded on the other side of the cliff. He yelled because the top of the Zemlya had also lit up. And he knew in that second what had happened. The light did not come from the warhead, for an extremely high mountain was between the huge globe and the blast. If the upper region of the Zemlya glowed, it was because a tongue from a Russian ship had brushed against it.

It must have been an accident, for the Russians surely had no wish to wreck the Zemlya. If they defeated the USAF, they could recapture the globe with no trouble.

"My God, she's falling!" yelled Broward. "Out of control!"

Scone looked once and quickly. He turned away and said, "All craft land immediately. All personnel transfer to my ship."

The maneuver took three minutes, for the men in the other dishes had to connect air tanks to their suits and then run from their ships to Scone's. Moreover, one man in each destroyer was later than his fellows since he had to set up the controls on his craft.

Scone did not explain what he meant to do until all personnel had made the transfer. In the meantime, they were at the mercy of the Russians if the enemy had chosen to attack over the top of the cliff. But Scone was gambling that the Russians would be too horrified at what was happening to the Zemlya. His own men would have been frozen if he had not compelled them to act. The Earth dying twice within twenty-four hours was almost more than they could endure.

Only the American commander, the man of stone, seemed not to feel.

Scone took his ship up against the face of the cliff until she was just below the top. Here the cliff was thin because of the slope on the other side. And here, hidden from view of the Russians, he drove a tongue two decimeters wide through the rock.

And, at the moment three Russian destroyers hurtled over the edge, tongues of compressed light lashing out on every side in the classic flailing movement, Scone's beam broke through the cliff.

The three empty USAF ships, on automatic, shot upwards at a speed that would have squeezed their human occupants into jelly—if they had had occupants. Their tongues shot out and flailed, caught the Russian tongues, twisted, shot out and flailed, caught the Russian tongues, twisted as the generators within the USAF vessels strove to outbend the Russian tongues.

Then, the American vessels rammed into the Russians, drove them upwards, flipped them over. And all six craft fell along the cliff's face, Russian and American intermingled, crashing into each other, bouncing off the sheer face, exploding, their fragments colliding, and smashed into the bottom of the canyon.

Scone did not see this, for he had completed the tongue through the tunnel, turned it off for a few seconds, and sent a video beam through. He was just in time to see the big battlebird start to float off the ground where it had been waiting. Perhaps, it had not accompanied the destroyers because of Russian contempt for American ability. Or, perhaps, because the commander was under orders not to risk the big ship unless necessary. Even now, the Lermontov rose slowly as if it might take two paths: over the cliff or towards the Zemlya. But, as it rose, Scone applied full power.

Some one, or some detecting equipment, on the Lermontov must have caught view of the tongue as it slid through space to intercept the battlebird. A tongue shot out towards the American beam. But Scone, in full and superb control, bent the axis of his beam, and the Russian missed. Then Scone's was in contact with the hull, and a hole appeared in the irradiated plastic.

Majestically, the Lermontov continued rising—and so cut itself almost in half. And, majestically, it fell.

Not before the Russian commander touched off all the missiles aboard his ship in a last frenzied defense, and the missiles flew out in all directions. Two hit the slope, blew off the face of the mountain on the Lermontov's side, and a jet of atomic energy flamed out through the tunnel created by Scone.

But he had dropped his craft like an elevator, was halfway down the cliff before the blasts made his side of the mountain tremble.

Half an hour later, the base of Eratosthenes sued for peace. For the sake of human continuity, said Panchurin, all fighting must cease forever on the moon.

The Chinese, who had been silent up to then despite their comrades' pleas for help, also agreed to accept the policy of Nationalism.

Now, Broward expected Scone to break down, to give way to the strain. He would only have been human if he had done so.

He did not. Not, at least, in anyone's presence.

Broward awoke early during a sleep-period. Unable to forget the dream he had just had, he went to find Ingrid Nashdoi. She was not in her lab; her assistant told him that she had gone to the dome with Scone.

Jealous, Broward hurried there and found the two standing there and looking up at the half-Earth. Ingrid was holding a puppy in her arms. This was one of the few animals that had been taken unharmed from the shattered tanks of the fallen Zemlya.

Broward, looking at them, thought of the problems that faced the Moon people. There was that of government, though this seemed for the moment to be settled. But he knew that there would be more conflict between the bases and that his own promotion of the Athenian ideology would cause grave trouble.

There was also the problem of women. One woman to every three men. How would this be solved? Was there any answer other than heartaches, frustration, hate, even murder?

"I had a dream," said Broward to them. "I dreamed that we on the Moon were building a great tower which would reach up to the Earth and that was our only way to get back to Earth. But everybody spoke a different tongue, and we couldn't understand each other. Therefore, we kept putting the bricks in the wrong places or getting into furious but unintelligible argument about construction."

He stopped, saw they expected more, and said, "I'm sorry. That's all there was. But the moral is obvious."

"Yes," said Ingrid, stroking the head of the wriggling puppy. She looked up at Earth, close to the horizon. "The physicists say it'll be two hundred years before we can go back. Do you realize that, barring accident or war, all three of us might live to see that day? That we might return with our great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren? And we can tell them of the Earth that was, so they will know how to build the Earth that must be."

"Two hundred years?" said Broward. "We won't be the same persons then."

But he doubted that even the centuries could change Scone. The man was made of rock. He would not bend or flow. And then Broward felt sorry for him. Scone would be a fossil, a true stone man, a petrified hero. Stone had its time and its uses. But leather also had its time.

"We'll never get back unless we do today's work every day," said Scone. "I'll worry about Earth when it's time to worry. Let's go; we've work to do."

THE END

0 notes

Text

Tongues of the Moon, Philip Jose Farmer

America had fallen, prey more to its own softness and confusion than to the machinations of the Soviets. Then, in the turbulent bloody starving years that followed the fall with their purges, uprisings, savage repressions, mass transportations to Siberia and other areas, importation of other nationalities to create division, and bludgeoning propaganda and reeducation, only the strong and the intelligent survived.

Scone, Broward, and Nashdoi were of the second generation born after the fall of Canada and the United States. They had been born and had lived because their parents were flexible, hardy, and quick. And because they had inherited and improved these qualities.

The Americans had become a problem to the Russians. And to the Chinese. Those Americans transported to Siberia had, together with other nationalities brought to that area, performed miracles with the harsh climate and soil, had made a garden. But they had become Siberians, not too friendly with the Russians.

China, to the south, looking for an area in which to dump their excess population, had protested at the bringing in of other nationalities. Russia's refusal to permit Chinese entry had been one more added to the long list of grievances felt by China towards her elder brother in the Marx family.

And on the North American continent, the American Communists had become another trial to Moscow. Russia, rich with loot from the U.S., had become fat. The lean underfed hungry Americans, using the Party to work within, had alarmed the Russians with their increasing power and influence. Moreover, America had recovered, was again a great industrial empire. Ostensibly under Russian control, the Americans were pushing and pressuring subtly, and not so subtly, to get their own way. Moscow had to resist being Uncle Samified.

To complicate the world picture, thousands of North Americans had taken refuge during the fall of their country in Argentine. And there the energetic and tough-minded Yanks (the soft and foolish died on the way or after reaching Argentine) followed the paths of thousands of Italians and Germans who had fled there long ago. They became rich and powerful; Félipé Howards, El Macho, was part-Argentinean Spanish, part-German, part-American.

The South African (sub-Saharan) peoples had ousted their Communist and Fascist rulers because they were white or white-influenced. Pan-Africanism was their motto. Recently, the South African Confederation had formed an alliance with Argentine. And the Axis had warned the Soviets that they must cease all underground activity in Axis countries, cease at once the terrible economic pressures and discriminations against them, and treat them as full partners in the nations of the world.

If this were not done, and if a war started, and the Argentineans saw their country was about to-be crushed, they would explode cobalt bombs. Rather death than dishonor.

The Soviets knew the temper of the proud and arrogant Argentineans. They had seemed to capitulate. There was a conference among the heads of the leading Soviets and Axes. Peaceful coexistence was being talked about.

But, apparently, the Axis had not swallowed this phrase as others had once swallowed it. And they had decided on a desperate move.

Having cheap lithium bombs and photon compressors and the means to deliver them with gravitomagnetic drives, the Axis was as well armed as their foes. Perhaps, their thought must have been, if they delivered the first blow, their anti-missiles could intercept enough Soviet missiles so that the few that did get through would do a minimum of damage. Perhaps. No one really knew what caused the Axis to start the war.

Whatever the decision of the Axis, the Axis had put on a good show. One of its features was the visit by their Moon officers to the base at Eratosthenes, the first presumably, in a series of reciprocal visits and parties to toast the new amiable relations.

Result: a dying Earth and a torn Moon.

Broward belonged to that small underground which neither believed in the old Soviet nor the old capitalist system. It wanted a form of government based on the ancient Athenian method of democracy on the local level and a loose confederation on the world level. All national boundaries would be abolished.

Such considerations, thought Broward, must be put aside for the time being. Getting independence of the Russians, getting rid of the hellish bonephones, was the thing to do now. Or so it had seemed to him.

But would not that inevitably lead to war and the destruction of all of humanity? Would it not be better to work with the other Soviets and hope that eventually the Communist ideal could be subverted and the Athenian established? With communities so small, the modified Athenian form of government would be workable. Later, after the Moon colonies increased in size and population, means could be found for working out intercolonial problems.

Or perhaps, thought Broward, watching the monolithic Scone, Scone did not really intend to force the other Soviets to cooperate? Perhaps, he hoped they would fight to the death and the North American base alone would be left to repopulate the world.

"Broward," said Scone, "go sound out Nashdoi. Do it subtly."

"Wise as the serpent, subtle as the dove," said Broward. "Or is it the other way around?"

Scone lifted his eyebrows. "Never heard that before. From what book?"

Broward walked away without answering. It was significant that Scone did not know the source of the quotation. The Old and New Testaments were allowed reading only for select scholars. Broward had read an illegal copy, had put his freedom and life in jeopardy by reading it.

But that was not the point here. The thought that occurred to him was that, nationality and race aside, the people on the Moon were a rather homogeneous group. Three-fourths of them were engineers or scientists of high standing, therefore, had high I.Q.'s. They were descended from ancestors who had proved their toughness and good genes by surviving through the last hundred years. They were all either agnostics or atheists or supposed to be so. There would not be any religious differences to split them. They were all in superb health, otherwise they would not be here. No diseases among them, not even the common cold. They would all make good breeding stock. Moreover, with recent advances in genetic manipulation, defective genes could be eliminated electrochemically. Such a manipulation had not been possible on Earth with its vast population where babies were being born faster than defective genes could be wiped out. But here where there were so few....

Perhaps, it would be better to allow the Soviet system to exist for now. Later, use subtle means to bend it towards the desired goal.

No! The system was based on too many falsities, among which the greatest was dialectical materialism. As long as the corrupt base existed, the structure would be corrupt.

0 notes

Text

Tongues of the Moon, Philip Jose Farmer

The Argentinean straightened up from his weary slump and summoned all the strength left in his bleeding body. He spoke in Russian so all would understand.

"We told you pigs we would take the whole world with us before we'd bend our necks to the Communist yoke!" he shouted.

At that moment, his gaunt high-cheekboned face with its long upper lip, thin lipline mustache, and fanatical blue eyes made him resemble the dictator of his country, Félipé Howards, El Macho (The Sledgehammer).

Panchurin ordered two soldiers and the doctor to take him to the jail. "I would like to kill the beast now," he said. "But he may have valuable information. Make sure he lives ... for the time being."

Then, Panchurin looked upwards again to Earth, hanging only a little distance above the horizon. The others also stared.

Earth, dark now, except for steady glares here and there, forest fires and cities, probably, which would burn for days. Perhaps weeks. Then, when the fires died out, the embers cooled, no more fire. No more vegetation, no more animals, no more human beings. Not for centuries.

Suddenly, Panchurin's face crumpled, tears flowed, and he began sobbing loudly, rackingly.

The others could not withstand this show of grief. They understood now. The shock had worn off enough to allow sorrow to have its way. Grief ran through them like fire through the forests of their native homes.

Broward, also weeping, looked at Scone and could not understand. Scone, alone among the men and women under the dome and the Earth, was not crying. His face was as impassive as the slope of a Moon mountain.

Scone did not wait for Panchurin to master himself, to think clearly. He said, "I request permission to return to Clavius, sir."

Panchurin could not speak; he could only nod his head.

"Do you know what the situation is at Clavius?" said Scone relentlessly.

Panchurin managed a few words. "Some missiles ... Axis base ... came close ... but no damage ... intercepted."

Scone saluted, turned, and beckoned to Broward and Nashdoi. They followed him to the exit to the field. Here Scone made sure that the air-retaining and gamma-ray and sun-deflecting force field outside the dome was on. Then the North Americans stepped outside onto the field without their spacesuits. They had done this so many times they no longer felt the fear and helplessness first experienced upon venturing from the protecting walls into what seemed empty space. They entered their craft, and Scone took over the controls.

After identifying himself to the control tower, Scone lifted the dish and brought it to the very edge of the force field. He put the controls on automatic, the field disappeared for the two seconds necessary for the craft to pass the boundary, and the dish, impelled by its own power and by the push of escaping air, shot forward.

Behind them, the faint flicker indicating the presence of the field returned. And the escaped air formed brief and bright streamers that melted under the full impact of the sun.

"That's something that will have to be rectified in the future," said Scone. "It's an inefficient, air-wasting method. We're not so long on power we can use it to make more air every time a dish enters or leaves a field."

He returned on the r-t, contacted Clavius, told them they were coming in. To the operator, he said, "Pei, how're things going?"

"We're still at battle stations, sir. Though we doubt if there will be any more attacks. Both the Argentinean and South African bases were wrecked. They don't have any retaliatory capabilities, but survivors may be left deep underground. We've received no orders from Eratosthenes to dispatch searchers to look for survivors. The base at Pushkin doesn't answer. It must...."

There was a crackling and a roar. When the noise died down, a voice in Russian said, "This is Eratosthenes. You will refrain from further radio communication until permission is received to resume. Acknowledge."

"Colonel Scone on the United Soviet Americas Force destroyer Broun. Order acknowledged."

He flipped the switch off. To Broward, he said, "Damn Russkies are starting to clamp down already. But they're rattled. Did you notice I was talking to Pei in English, and they didn't say a thing about that? I don't think they'll take much effective action or start any witch-hunts until they recover fully from the shock and have a chance to evaluate.

"Tell me, is Nashdoi one of you Athenians?"

Broward looked at Nashdoi, who was slumped on a seat at the other end of the bridge. She was not within earshot of a low voice.

"No," said Broward. "I don't think she's anything but a lukewarm Marxist. She's a member of the Party, of course. Who on the Moon isn't? But like so many scientists here, she takes a minimum interest in ideology, just enough not to be turned down when she applied for psychological research here.

"She was married, you know. Her husband was called back to Earth only a little while ago. No one knew if it was for the reasons given or if he'd done something to displease the Russkies or arouse their suspicions. You know how it is. You're called back, and maybe you're never heard of again."

"What other way is there?" said Scone. "Although I don't like the Russky dictating the fate of any American."

"Yes?" said Broward. He looked curiously at Scone, thinking of what a mass of contradictions, from his viewpoint, existed inside that massive head. Scone believed thoroughly in the Soviet system except for one thing. He was a Nationalist; he wanted an absolutely independent North American republic, one which would reassert its place as the strongest in the world.

And that made him dangerous to the Russians and the Chinese.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

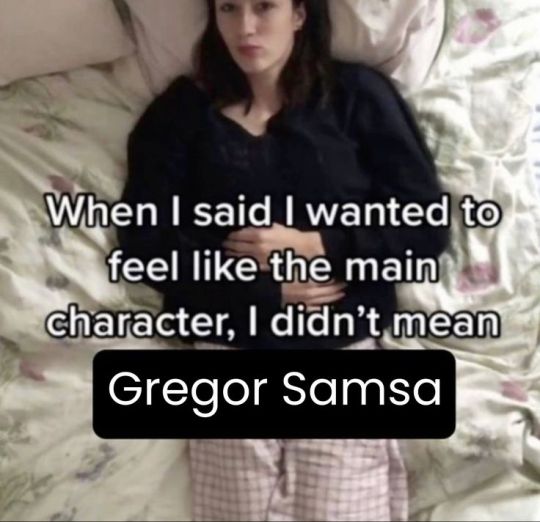

“Recently, when I got out of the elevator at my usual hour, it occurred to me that my life, whose days more & more repeat themselves down to the smallest detail, resembles that punishment in which each pupil must according to his offence write down the same meaningless (in repetition, at least) sentence ten times, a hundred times or even oftener; except that in my case the punishment is given me with only this limitation: “as many times as you can stand it.””

— Franz Kafka, Diaries (via kafkaesque-world)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tongues of the Moon, Philip Jose Farmer

"You won't have to untape your bomb," said Broward. "The transmitters are mined. So are the generators."

"How did you do it? And why didn't you tell me you'd already done it?"

"The Russians have succeeded in making us Americans distrust each other," said Broward. "Like everybody else, I don't reveal information until I absolutely have to. As to your first question, I'm not only a doctor, I'm also a physical anthropologist engaged in a Moonwide project. I frequently attend conferences at this base, stay here several sleeps. And what you did so permanently with your gun, I did temporarily with a sleep-inducing aerosol. But, now that we understand each other, let's get out."

"Not until I see the bombs you say you've planted."

Broward smiled. Then, working swiftly with a screwdriver he took from a drawer, he removed several wall-panels. Scone looked into the recesses and examined the component boards, functional blocks, and wires which jammed the interior.

"I don't see any explosives," Scone said.

"Good," said Broward. "Neither will the Russians, unless they measure the closeness of the walls to the equipment. The explosive is spread out over the walls in a thin layer which is colored to match the original green. Also, thin strips of a chemical are glued to the walls. This chemical is temperature-sensitive. When the transmitters are operating and reach maximum radiation of heat, the strips melt. And the chemicals released interact with the explosive, detonate it."

"Ingenious," said Scone somewhat sourly. "We don't ..." and he stopped.

"Have such stuff? No wonder. As far as I know, the detonator and explosive were made here on the Moon. In our lab at Clavius."

"If you could get into this room without being detected and could also smuggle all that stuff from Clavius, then the Russ can be beaten," said Scone.

Now, Broward was surprised. "You doubted they could?"

"Never. But all the odds were on their side. And you know what a conditioning they give us from the day we enter kindergarten."

"Yes. The picture of the all-knowing, all-powerful Russian backed by the force of destiny itself, the inevitable rolling forward and unfolding of History as expounded by the great prophet, the only prophet, Marx. But it's not true. They're human."

They replaced the panels and the screwdriver and left the room. Just as they entered the hall, and the door swung shut behind them, they heard the thumps of boots and shouts. Scone had just straightened up from putting the key back into the dead officer's pocket when six Russians trotted around the corner. Their officer was carrying a burp gun, the others, automatic rifles.

"Don't shoot!" yelled Scone in Russian. "Americans! USAF!"

The captain, whom both Americans had seen several times before, lowered her burper.

"It's fortunate that I recognized you," she said. "We just killed three Axes who were dressed in Russian uniforms. They shot four of my men before we cut them down. I wasn't about to take a chance you might not be in disguise, too."

She gestured at the dead men. "The Axes got them, too?"

"Yes," said Scone. "But I don't know if any Axes are in there."

He pointed at the door to the control room.

"If there were, we'd all be screaming with pain," said the captain. "Anyway, they would have had to take the key from the officer on guard."

She looked suspiciously at the two, but Scone said, "You'll have to search him. I didn't touch him, of course."

She dropped to one knee and unbuttoned the officer's inner coatpocket, which Scone had not neglected to rebutton after replacing the key.

Rising with the key, she said, "I think you two must go back to the dome."

Scone's face did not change expression at this evidence of distrust. Broward smiled slightly.

"By the way," she said, "what are you doing here?"

"We escaped from the dome," said Broward. "We heard firing down this way, and we thought we should protect our rear before going back into the dome. We found dead Russians, but we never did see the enemy. They must have been the ones you ran into."

"Perhaps," she said. "You must go. You know the rules. No unauthorized personnel near the BR."

"No non-Russians, anyway," said Scone flatly. "I know. But this is an emergency."

"You must go," she said, raising the barrel of her gun. She did not point it at them, but they did not doubt she would.

Scone turned and strode off, Broward following. When they had turned the first corner, Scone said, "We must leave the base on the first excuse. We have to get back to Clavius."

"So we can start our own war?"

"Not necessarily. Just declare independence. The Russ may have their belly full of death."

"Why not wait until we find out what the situation on Earth is? If the Russians have any strength left on Earth, we may be crushed."

"Now!" said Scone. "If we give the Russ and the Chinese time to recover from the shock, we lose our advantage."

"Things are going too fast for me, too," said Broward. "I haven't time or ability to think straight now. But I have thought of this. Earth could be wiped out. If so, we on the Moon are the only human beings left alive in the universe. And...."

"There are the Martian colonies. And the Ganymedan and Mercutian bases."

"We don't know what's happened to them. Why start something which may end the entire human species? Perhaps, ideology should be subordinated for survival. We need every man and woman, every...."

"We must take the chance that the Russians and Chinese won't care to risk making Homo sapiens extinct. They'll have to cooperate, let us go free.

"We don't have time to talk. Act now; talk after it's all over."

But Scone did not stop talking. During their passage through the corridors, he made one more statement.

"The key to peace on the Moon, and to control of this situation, is the Zemlya."

Broward was puzzled. He knew Scone was referring to the Brobdingnagian interstellar exploration vessel which had just been built and outfitted and was now orbiting around Earth. The Zemlya (Russian for Earth) had been scheduled to leave within a few days for its ten year voyage to Alpha Centaurus and, perhaps, the stars beyond. What the Zemlya could have to do with establishing peace on the Moon was beyond Broward. And Scone did not seem disposed to explain.

Just then, they passed a full-length mirror, and Broward saw their images. Scone looked like a mountain of stone walking. And he, Broward thought, he himself looked like a man of leather. His shorter image, dark brown where the skin showed, his head shaven so the naked skull seemed to be overlaid with leather, his brown eyes contrasting with the rock-pale eyes of Scone, his lips so thick compared with Scone's, which were like a thin groove cut into granite. Leather against stone. Stone could outwear leather. But leather was more flexible.

Was the analogy, as so many, false? Or only partly true?

Broward tended to think in analogies; Scone, directly.

At the moment, a man like Scone was needed. Practical, quick reacting. But, like so many practical men, impractical when it came to long range and philosophical thinking. Not much at extrapolation beyond the immediate. Broward would follow him up to a point. Then....

They came to the entrance to the dome. Only the sound of voices came from it. Together, they stuck their heads around the side of the entrance. And they saw many dead, some wounded, a few men and women standing together near the center of the floor. All, except one, were in the variously colored and marked uniforms of the Soviet Republics. The exception was a tall man in the silver dress uniform of Argentine. His right arm hung limp and bloody; his skin was grey.

"Colonel Lorentz," said Scone. "We've one prisoner, at least."

After shouting to those within the dome not to fire, the two walked in. Major Panchurin, the highest-ranking Russian survivor, lifted a hand to acknowledge their salute. He was too busy talking over the bonephone to say anything to them.

The two examined the dome. The visiting delegation of Axis officers was dead except for Lorentz. The Russians left standing numbered six; the Chinese, four; the Europeans, one; the Arabic, two; the Indian-East Asiatic, none. There were four Americans alive. Broward. Scone. Captain Nashdoi. And a badly wounded woman, Major Hoebel.

Broward walked towards Hoebel to examine her. Before he could do anything the Russian doctor, Titiev, rose from her side. He said, "I'm sorry, captain. She isn't going to make it."

Broward looked around the dome and made a remark which must, at the time, have seemed irrelevant to Titiev. "Only three women left. If the ratio is the same on the rest of the Moon, we've a real problem."

Scone had followed Broward. After Titiev had left, and after making sure their bonephones were not on, Scone said in a low voice, "There were seventy-five Russians stationed here. I doubt if there are over forty left in the entire base. I wonder how many in Pushkin?"

Pushkin was the base on the other side of the Moon.

They walked back to the group around Panchurin and turned on their phones so they could listen in.

Panchurin's skin paled, his eyes widened, his hands raised protestingly.

"No, no," he moaned out loud.

"What is it?" said Scone, who had heard only the last three words coming in through the device implanted in his skull.

Panchurin turned a suddenly old face to him. "The commander of the Zemlya said that the Argentineans have set off an undetermined number of cobalt bombs. More than twenty, at the very least."

He added, "The Zemlya is leaving its orbit. It intends to establish a new one around the Moon. It won't leave until we evaluate our situation. If then."

Every Soviet in the room looked at Lorentz.

0 notes

Text

Tongues of the moon, Philip Jose Farmer

Broward rose, though he wanted to cling to the floor. Directly below them—or, perhaps, to the side but still underground—a white-hot "tongue" was blasting a narrow tunnel through the rock. Behind it, also hidden within the rock, in a shaft which the vessel must have taken a long time to sink without being detected, was a battlebird. Only a large ship could carry the huge generators required to drive a tongue that would damage a base. A tongue, or snake, as it was sometimes called. A flexible beam of "straightened-out" photons, the ultimate development of the laser.

And when the tongue reached the end of the determined tunnel, then the photons would be "un-sprung". And all the energy crammed into the compressed photons would dissipate.

"Follow me!" said Scone, and he began running.

Broward took a step, halted in amazement, called out, "The suits ... other way!"

Then, he resumed running after Scone. Evidently, the colonel was not concerned about the dome cracking wide open. His only thought was for the bonephone controls.

Broward expected to be cut down under a storm of bullets. But the room was silent except for the groans of some wounded. And the ever-increasing rumble from deep under.

The survivors of the fight were too intent on the menace probing beneath them to pay attention to the two runners—if they saw them.

That is, until Scone bounded through the nearest exit from the dome in a great leap afforded by the Moon's weak gravity. He almost hit his head on the edge of the doorway.

Then, somebody shot at Broward. But his body, too, was flying through the exit, his legs pulled up, and the three bullets passed beneath him and blew holes in the rock wall ahead of him.

Broward slammed into the wall and fell back on the floor. Though half-stunned, he managed to roll past the corner, out of line of fire, into the hallway. He rose, breathing hard, and checked to make sure he had not broken his numbed wrists and hands, which had cushioned much of his impact against the wall. And he was thankful that the tongues needed generators too massive to be compacted into hand weapons. If the Axes had been able to smuggle tonguers into the dome, they could have wiped out every Soviet on the base.

The rumble became louder. The rock beneath his feet shook. The walls quivered like jelly. Then....

Not the ripping upwards of the floor beneath his feet, the ravening blast opening the rock and lashing out at him with sear of fire and blow of air to burn him and crush him against the ceiling at the same time.

From somewhere deep and off to one side was an explosion. The rock swelled. Then, subsided.

Silence.

Only his breathing.

For about six seconds while he thought that the Russian ships stationed outside the base must have located the sunken Axis vessel and destroyed it just before it blew up the base.

From the dome, a hell's concerto of small-gun fire.

Broward ran again, leaping over the twisted and shattered bodies of Russians and Axes. Here the attacking officers had been met by Soviet guards, and the two groups had destroyed each other.

Far down the corridor, Scone's tall body was hurtling along, taking the giant steps only a long-time Lunie could safely handle. He rounded a corner, was gone down a branching corridor.

Broward, following Scone, entered two more branches, and then stopped when he heard the boom of a .45. Two more booms. Silence. Broward cautiously stuck his head around the corner.

He saw two Russian soldiers on the floor, their weapons close to their lifeless hands. Down the hall, Scone was running.

Broward did not understand. He could only surmise that the Russians had been so surprised by Scone that they had fired, or tried to fire, before they recognized the North American uniform. And Scone had shot in self-defense.

But the corridors were well lit with electroluminescent panels. All three should have seen at once that none wore the silver of Argentine or the scarlet and brown of the South Africans. So...?

He did not know. Scone could tell him, but Broward would have trouble catching up with him.

Then, once more, he heard the echoes of a .45 bouncing around the distant corner of the hall.

When Broward rounded the turn as cautiously as he had the previous one, he saw two more dead Russians. And he saw Scone rifling the pockets of the officer of the two.

"Scone!" he shouted so the man would not shoot him, too, in a frenzy. "It's Broward!"

Coming closer, he said, "What're you doing?"

Scone rose from the officer with a thin plastic cylinder about a decimeter long in one hand. With the other hand, he pointed his .45 at Broward's solar plexus.

"I'm going to blow up the controls and the transmitters," he said. "What did you think?"

Choking, Broward said, "You're not working for the Axis?"

He did not believe Scone was. But, in his astonishment, he could only think of that as a reason for Scone's behavior. Despite his accusation about Scone's intentions, he had not really believed the man meant to do more than insure that the controls did not fall into Axis hands.

Scone said, "Those swine! No! I'm just making sure that the Axes will not be able to use the bonephones if they do seize this office. Besides, I have never liked the idea of being under Russian control. These hellish devices...."

Broward pointed at the corpses. "Why?"

"They had their orders," said Scone. "Which were to allow no one into the control room without proper authorization. I didn't want to argue and so put them on their guard. I had to do what was expedient."

Scone glared at Broward, and he said, "Expediency is going to be the rule for this day. No matter who suffers."

Broward said, "You don't have to kill me, too. I am an American. If I could think as coolly as you, I might have done the same thing myself."

He paused, took a deep breath, and said, "Perhaps, you didn't do this on the spur of the moment. Perhaps, you planned this long before. If such a situation as this gave you a chance."

"We haven't time to stand here gabbing," said Scone.

He backed away, his gun and gaze steady on Broward. With his other hand, he felt around until the free end of the thin tube fitted into the depression in the middle of the door. He pressed in on the key, and (the correct sequence of radio frequencies activating the unlocking circuit) the door opened.

Scone motioned for Broward to precede him. Broward entered. Scone came in, and the door closed behind him.

"I thought I should kill you when we were behind the bank," said Scone. "But you weren't—as far as I had been able to determine—a Russian agent. Far from it. And you were, as you said, a fellow American. But...."

Broward looked at the far wall with its array on array of indicator lights, switches, pushbuttons, and slots for admission of coded cards and tapes.

He turned to Scone, and he said, "Time for us to quit being coy. I've known for a long time that you were the chief of a Nationalist underground."

For the first time since Broward had known him, Scone's face cracked wide open.

"What?"

Then, the cracks closed up, the cliff-front was solid again.

"Why didn't you report me. Or are you...?"

"Not of your movement, no," said Broward. "I'm an Athenian. You've heard of us?"

"I know of them," said Scone. "A lunatic fringe. Neither Russ, Chinese, nor Yank. I had suspected that you weren't a very solid Marxist. Why tell me this?"

"I want to talk you out of destroying the controls and the transmitters," said Broward.

"Why?"

"Don't blow them up. Given time, the Russ could build another set. And we'd be under their control again. Don't destroy them. Plant a bomb which can be set off by remote control. The moment they try to use the phones to paralyze us, blow up the transmitters. That might give us time to remove the phones from our skulls with surgery. Or insulate the phones against reception. Or, maybe, strike at the Russkies. If fighting back is what you have in mind. I don't know how far your Nationalism goes."

"That might be better," said Scone, his voice flat, not betraying any enthusiasm for the plan. "Can I depend upon you and your people?"

"I'll be frank. If you intend to try for complete independence of the Russians, you'll have our wholehearted cooperation. Until we are independent."

"And after that—what then?"

"We believe in violence only after all other means have failed. Of course, mental persuasion was useless with the Russians. With fellow Americans, well...."

"How many people do you have at Clavius?"

Broward hesitated, then said, "Four. All absolutely dependable. Under my orders. And you?"

"More than you," said Scone. "You understand that I'm not sharing the command with you? We can't take time out to confer. We need a man who can give orders to be carried out instantly. And my word will be life or death? No argument?"

"No time now for discussions of policy. I can see that. Yes. I place myself and my people under your orders. But what about the other Americans? Some are fanatical Marxists. Some are unknown, X."

"We'll weed out the bad ones," said Scone. "I don't mean by bad the genuine Marxists. I'm one myself. I mean the non-Nationalists. If anyone wants to go to the Russians, we let them go. Or if anybody fights us, they die."

"Couldn't we just continue to keep them prisoners?"

"On the Moon? Where every mouth needs two pairs of hands to keep breathing and eating? Where even one parasite may mean eventual death for all others? No!"

Broward said, "All right. They die. I hope...."

"Hopes are something to be tested," said Scone. "Let's get to work. There should be plenty of components here with which to rig up a control for the bomb. And I have the bomb taped to my belly."

2 notes

·

View notes

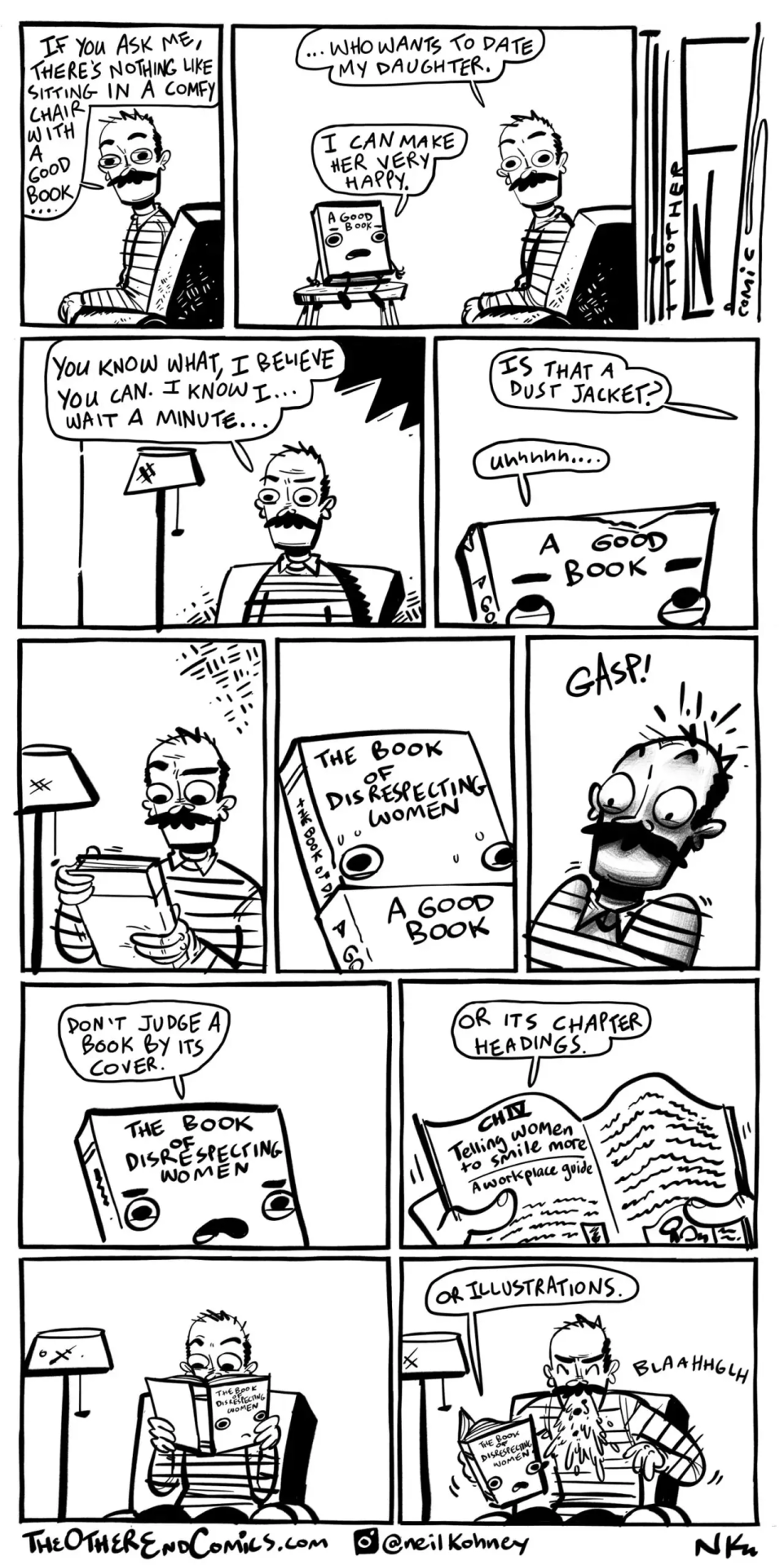

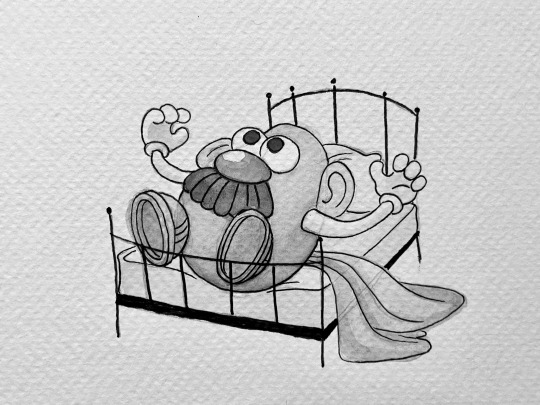

Text

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic Mr. Potato Head

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a short story while I sort out what I want to do here.

0 notes

Text

Tongues of the Moon, Philip Jose Farmer

Fireflies on the dark meadow of Earth....

The men and women looking up through the dome in the center of the crater of Eratosthenes were too stunned to cry out, and some did not understand all at once the meaning of those pin-points on the shadowy face of the new Earth, the lights blossoming outwards, then dying. So bright they could be seen through the cloudmasses covering a large part of Europe. So bright they could be located as London, Paris, Brussels, Copenhagen, Leningrad, Rome, Reykjavik, Athens, Cairo....

Then, a flare near Moscow that spread out and out and out....

Some in the dome recovered more quickly than others. Scone and Broward, two of the Soviet North American officers present at the reception in honor of the South Atlantic Axis officers, acted swiftly enough to defend themselves.

Even as the Axes took off their caps and pulled small automatics and flat bombs from clips within the caps, the two Americans reached for the guns in their holsters.

Too late to do them much good if the Argentineans and South Africans nearest them had aimed at them. The Axes had no shock on their faces; they must have known what to expect. And their weapons were firing before the fastest of the Soviets could reach for the butts of their guns.

But the Axes must have had orders to kill the highest ranking Soviets first. At these the first fire was concentrated.

Marshal Kosselevsky had half-turned to his guest, Marshal Ramírez-Armstrong. His mouth was open and working, but no words came from it. Then, his eyes opened even wider as he saw the stubby gun in the Argentinean's hand. His own hand rose in a defensive, wholly futile, gesture.

Ramírez-Armstrong's gun twanged three times. Other Axes' bullets also struck the Russian. Kosselevsky clutched at his paunch, and he fell face forward. The .22 calibers did not have much energy or penetrate deeply into the flesh. But they exploded on impact; they did their work well enough.

Scone and Broward took advantage of not being immediate targets. Guns in hand, they dived for the protection of a man-tall bank of instruments. Bullets struck the metal cases and exploded, for, in a few seconds, the Axes had accomplished their primary mission and were now out to complete their secondary.

Broward felt a sting on his cheek as he rolled behind the bank. He put his hand on his cheek, and, when he took it away, he saw his hand covered with blood. But his probing finger felt only a shallow of flesh. He forgot about the wound. Even if it had been more serious, he would have had no time to take care of it.

A South African stepped around the corner of the bank, firing as he came.

Broward shot twice with his .45. The dark-brown face showered into red and lost its human shape. The body to which it was now loosely attached curved backwards and fell on the floor.

"Broward!" called Scone above the twang and boom of the guns and the wharoop! of a bomb. "Can you see anything? I can't even stick my head around the corner without being shot at."

Broward looked at Scone, who was crouched at the other end of the bank. Scone's back was to Broward, but Scone's head was twisted far enough for him to see Broward out of the corner of his eye.

Even at that moment, when Broward's thoughts should have excluded everything but the fight, he could not help comparing Scone's profile to a face cut out of rock. The high bulbous forehead, thick bars of bone over the eyes, Dantesque nose, thin lips, and chin jutting out like a shelf of granite, more like a natural formation which happened to resemble a chin than anything which had taken shape in a human womb.

Ugly, massive, but strong. Nothing of panic or fear in that face; it was as steady as his voice.

Old Gibraltar-face, thought Broward for perhaps the hundredth time. But this time he did not feel dislike.

"I can't see any more than you—Colonel," he said.

Scone, still squatting, shifted around until he could bring one eye to bear fully on Broward. It was a pale blue, so pale it looked empty, unhuman.

"Colonel?"

"Now," said Broward. "A bomb got General Mansfield and Colonels Omato and Ingrass. That gives you a fast promotion, sir."

"We'll both be promoted above this bank if an Axe lobs a bomb over," said Scone. "We have to get out of here."

"To where?"

Scone frowned—granite wrinkling—and said, "It's obvious the Axes want to do more than murder a few Soviets. They must plan on getting control of the bonephones. I know I would if I were they. If they can capture the control center, every Soviet on the Moon—except for the Chinese—is at their mercy. So...."

"We make a run for the BR?"

"I'm not ordering you to come with me," said Scone. "That's almost suicide. But you will give me a covering fire."

"I'll go with you, Colonel."

Scone glanced at the caduceuses on Broward's lapels, and he said, "We'll need your professional help after we clean out the Axes. No."

"You need my amateurish help now," said Broward. "As you see"—he jerked his thumb at the nearly headless Zulu—"I can handle a gun. And if we don't get to the bonephone controls first, life won't be worth living. Besides, I don't think the Axes intend taking any prisoners."

"You're right," said Scone. But he seemed hesitant.

"You're wondering why I'm falling in so quickly with your plan to wreck the control center?" said Broward. "You think I'm a Russky agent?"

"I didn't say I intended to wreck the transmitters," said Scone. "No. I know what you are. Or, I think I do. You're not a Russky. You're a...."

Scone stopped. Like Broward, he felt the rock floor quiver, then start shaking. And a low rumbling reached them, coming up through their feet before their ears detected it.

Scone, instead of throwing himself flat on the floor—an instinctive but useless maneuver—jumped up from his squatting position.

"Now! Now! The others'll be too scared to move!"

1 note

·

View note

Text

It Can't Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis

Chapter 37-38 End

CHAPTER XXXVII

HIS beard had grown again—he and his beard had been friends for many years, and he had missed it of late. His hair and mustache had again assumed a respectable gray in place of the purple dye that under electric lights had looked so bogus. He was no longer impassioned at the sight of a lamb chop or a cake of soap. But he had not yet got over the pleasure and slight amazement at being able to talk as freely as he would, as emphatically as might please him, and in public.

He sat with his two closest friends in Montreal, two fellow executives in the Department of Propaganda and Publications of the New Underground (Walt Trowbridge, General Chairman), and these two friends were the Hon. Perley Beecroft, who presumably was the President of the United States, and Joe Elphrey, an ornamental young man who, as "Mr. Cailey," had been a prize agent of the Communist Party in America till he had been kicked out of that almost imperceptible body for having made a "united front" with Socialists, Democrats, and even choir-singers when organizing an anti-Corpo revolt in Texas.

Over their ale, in this café, Beecroft and Elphrey were at it as usual: Elphrey insisting that the only "solution" of American distress was dictatorship by the livelier representatives of the toiling masses, strict and if need be violent, but (this was his new heresy) not governed by Moscow. Beecroft was gaseously asserting that "all we needed" was a return to precisely the political parties, the drumming up of votes, and the oratorical legislating by Congress, of the contented days of William B. McKinley.

But as for Doremus, he leaned back not vastly caring what nonsense the others might talk so long as it was permitted them to talk at all without finding that the waiters were M.M. spies; and content to know that, whatever happened, Trowbridge and the other authentic leaders would never go back to satisfaction in government of the profits, by the profits, for the profits. He thought comfortably of the fact that just yesterday (he had this from the chairman's secretary), Walt Trowbridge had dismissed Wilson J. Shale, the ducal oil man, who had come, apparently with sincerity, to offer his fortune and his executive experience to Trowbridge and the cause.

"Nope. Sorry, Will. But we can't use you. Whatever happens—even if Haik marches over and slaughters all of us along with all our Canadian hosts—you and your kind of clever pirates are finished. Whatever happens, whatever details of a new system of government may be decided on, whether we call it a 'Cooperative Commonwealth' or 'State Socialism' or 'Communism' or 'Revived Traditional Democracy,' there's got to be a new feeling—that government is not a game for a few smart, resolute athletes like you, Will, but a universal partnership, in which the State must own all resources so large that they affect all members of the State, and in which the one worst crime won't be murder or kidnaping but taking advantage of the State—in which the seller of fraudulent medicine, or the liar in Congress, will be punished a whole lot worse than the fellow who takes an ax to the man who's grabbed off his girl.... Eh? What's going to happen to magnates like you, Will? God knows! What happened to the dinosaurs?"

So was Doremus in his service well content.

Yet socially he was almost as lonely as in his cell at Trianon; almost as savagely he longed for the not exorbitant pleasure of being with Lorinda, Buck, Emma, Sissy, Steve Perefixe.

None of them save Emma could join him in Canada, and she would not. Her letters suggested fear of the un-Worcesterian wildernesses of Montreal. She wrote that Philip and she hoped they might be able to get Doremus forgiven by the Corpos! So he was left to associate only with his fellow refugees from Corpoism, and he knew a life that had been familiar, far too familiar, to political exiles ever since the first revolt in Egypt sent the rebels sneaking off into Assyria.

It was no particularly indecent egotism in Doremus that made him suppose, when he arrived in Canada, that everyone would thrill to his tale of imprisonment, torture, and escape. But he found that ten thousand spirited tellers of woe had come there before him, and that the Canadians, however attentive and generous hosts they might be, were actively sick of pumping up new sympathy. They felt that their quota of martyrs was completely filled, and as to the exiles who came in penniless, and that was a majority of them, the Canadians became distinctly weary of depriving their own families on behalf of unknown refugees, and they couldn't even keep up forever a gratification in the presence of celebrated American authors, politicians, scientists, when they became common as mosquitoes.

It was doubtful if a lecture on Deplorable Conditions in America by Herbert Hoover and General Pershing together would have attracted forty people. Ex-governors and judges were glad to get jobs washing dishes, and ex-managing-editors were hoeing turnips. And reports said that Mexico and London and France were growing alike apologetically bored.

So Doremus, meagerly living on his twenty-dollar-a-week salary from the N.U., met no one save his own fellow exiles, in just such salons of unfortunate political escapists as the White Russians, the Red Spaniards, the Blue Bulgarians, and all the other polychromatic insurrectionists frequented in Paris. They crowded together, twenty of them in a parlor twelve by twelve, very like the concentration-camp cells in area, inhabitants, and eventual smell, from 8 P.M. till midnight, and made up for lack of dinner with coffee and doughnuts and exiguous sandwiches, and talked without cessation about the Corpos. They told as "actual facts" stories about President Haik which had formerly been applied to Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini—the one about the man who was alarmed to find he had saved Haik from drowning and begged him not to tell.

In the cafés they seized the newspapers from home. Men who had had an eye gouged out on behalf of freedom, with the rheumy remaining one peered to see who had won the Missouri Avenue Bridge Club Prize.

They were brave and romantic, tragic and distinguished, and Doremus became a little sick of them all and of the final brutality of fact that no normal man can very long endure another's tragedy, and that friendly weeping will some day turn to irritated kicking.

He was stirred when, in a hastily built American interdenominational chapel, he heard a starveling who had once been a pompous bishop read from the pine pulpit:

"By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.... How shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land? If I forget thee O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy."

Here in Canada the Americans had their Weeping Wall and daily cried with false, gallant hope, "Next year in Jerusalem!"

Sometimes Doremus was vexed by the ceaseless demanding wails of refugees who had lost everything, sons and wives and property and self-respect, vexed that they believed they alone had seen such horrors; and sometimes he spent all his spare hours raising a dollar and a little weary friendliness for these sick souls; and sometimes he saw as fragments of Paradise every aspect of America— such oddly assorted glimpses as Meade at Gettysburg and the massed blue petunias in Emma's lost garden, the fresh shine of rails as seen from a train on an April morning and Rockefeller Center. But whatever his mood, he refused to sit down with his harp by any foreign waters whatever and enjoy the importance of being a celebrated beggar.

He'd get back to America and chance another prison. Meantime he neatly sent packages of literary dynamite out from the N.U. offices all day long, and efficiently directed a hundred envelope-addressers who once had been professors and pastrycooks.

He had asked his superior, Perley Beecroft, for assignment in more active and more dangerous work, as secret agent in America—out West, where he was not known. But headquarters had suffered a good deal from amateur agents who babbled to strangers, or who could not be trusted to keep their mouths shut while they were being flogged to death. Things had changed since 1929. The N.U. believed that the highest honor a man could earn was not to have a million dollars but to be permitted to risk his life for truth, without pay or praise.

Doremus knew that his chiefs did not consider him young enough or strong enough, but also that they were studying him. Twice he had the honor of interviews with Trowbridge about nothing in particular—surely it must have been an honor, though it was hard to remember it, because Trowbridge was the simplest and friendliest man in the whole portentous spy machine. Cheerfully Doremus hoped for a chance to help make the poor, overworked, worried Corpo officials even more miserable than they normally were, now that war with Mexico and revolts against Corpoism were jingling side by side.

In July, 1939, when Doremus had been in Montreal a little over five months, and a year after his sentence to concentration camp, the American newspapers which arrived at N.U. headquarters were full of resentment against Mexico.

Bands of Mexicans had raided across into the United States—always, curiously enough, when our troops were off in the desert, practice-marching or perhaps gathering sea shells. They burned a town in Texas—fortunately all the women and children were away on a Sunday-school picnic, that afternoon. A Mexican Patriot (aforetime he had also worked as an Ethiopian Patriot, a Chinese Patriot, and a Haitian Patriot) came across, to the tent of an M.M. brigadier, and confessed that while it hurt him to tattle on his own beloved country, conscience compelled him to reveal that his Mexican superiors were planning to fly over and bomb Laredo, San Antonio, Bisbee, and probably Tacoma, and Bangor, Maine.

This excited the Corpo newspapers very much indeed and in New York and Chicago they published photographs of the conscientious traitor half an hour after he had appeared at the Brigadier's tent... where, at that moment, forty-six reporters happened to be sitting about on neighboring cactuses.

America rose to defend her hearthstones, including all the hearthstones on Park Avenue, New York, against false and treacherous Mexico, with its appalling army of 67,000 men, with thirty-nine military aeroplanes. Women in Cedar Rapids hid under the bed; elderly gentlemen in Cattaraugus County, New York, concealed their money in elm-tree boles; and the wife of a chicken- raiser seven miles N.E. of Estelline, South Dakota, a woman widely known as a good cook and a trained observer, distinctly saw a file of ninety-two Mexican soldiers pass her cabin, starting at 3:17 A.M. on July 27, 1939.

To answer this threat, America, the one country that had never lost a war and never started an unjust one, rose as one man, as the Chicago Daily Evening Corporate put it. It was planned to invade Mexico as soon as it should be cool enough, or even earlier, if the refrigeration and air-conditioning could be arranged. In one month, five million men were drafted for the invasion, and started training.

Thus—perhaps too flippantly—did Joe Cailey and Doremus discuss the declaration of war against Mexico. If they found the whole crusade absurd, it may be stated in their defense that they regarded all wars always as absurd; in the baldness of the lying by both sides about the causes; in the spectacle of grown-up men engaged in the infantile diversions of dressing-up in fancy clothes and marching to primitive music. The only thing not absurd about wars, said Doremus and Cailey, was that along with their skittishness they did kill a good many millions of people. Ten thousand starving babies seemed too high a price for a Sam Browne belt for even the sweetest, touchingest young lieutenant.

Yet both Doremus and Cailey swiftly recanted their assertion that all wars were absurd and abominable; both of them made exception of the people's wars against tyranny, as suddenly America's agreeable anticipation of stealing Mexico was checked by a popular rebellion against the whole Corpo régime.

The revolting section was, roughly, bounded by Sault Ste. Marie, Detroit, Cincinnati, Wichita, San Francisco, and Seattle, though in that territory large patches remained loyal to President Haik, and outside of it, other large patches joined the rebels. It was the part of America which had always been most "radical"—that indefinite word, which probably means "most critical of piracy." It was the land of the Populists, the Non-Partisan League, the Farmer-Labor Party, and the La Follettes—a family so vast as to form a considerable party in itself.

Whatever might happen, exulted Doremus, the revolt proved that belief in America and hope for America were not dead.

These rebels had most of them, before his election, believed in Buzz Windrip's fifteen points; believed that when he said he wanted to return the power pilfered by the bankers and the industrialists to the people, he more or less meant that he wanted to return the power of the bankers and industrialists to the people. As month by month they saw that they had been cheated with marked cards again, they were indignant; but they were busy with cornfield and sawmill and dairy and motor factory, and it took the impertinent idiocy of demanding that they march down into the desert and help steal a friendly country to jab them into awakening and into discovering that, while they had been asleep, they had been kidnaped by a small gang of criminals armed with high ideals, well-buttered words and a lot of machine guns.

So profound was the revolt that the Catholic Archbishop of California and the radical Ex-Governor of Minnesota found themselves in the same faction.

At first it was a rather comic outbreak—comic as the ill-trained, un-uniformed, confusedly thinking revolutionists of Massachusetts in 1776. President General Haik publicly jeered at them as a "ridiculous rag-tag rebellion of hoboes too lazy to work." And at first they were unable to do anything more than scold like a flock of crows, throw bricks at detachments of M.M.'s and policemen, wreck troop trains, and destroy the property of such honest private citizens as owned Corpo newspapers.

It was in August that the shock came, when General Emmanuel Coon, Chief of Staff of the regulars, flew from Washington to St. Paul, took command of Fort Snelling, and declared for Walt Trowbridge as Temporary President of the United States, to hold office until there should be a new, universal, and uncontrolled presidential election.

Trowbridge proclaimed acceptance—with the proviso that he should not be a candidate for permanent President.

By no means all of the regulars joined Coon's revolutionary troops. (There are two sturdy myths among the Liberals: that the Catholic Church is less Puritanical and always more esthetic than the Protestant; and that professional soldiers hate war more than do congressmen and old maids.) But there were enough regulars who were fed up with the exactions of greedy, mouth-dripping Corpo commissioners and who threw in with General Coon so that immediately after his army of regulars and hastily trained Minnesota farmers had won the battle of Mankato, the forces at Leavenworth took control of Kansas City, and planned to march on St. Louis and Omaha; while in New York, Governor's Island and Fort Wadsworth looked on, neutral, as unmilitary-looking and mostly Jewish guerrillas seized the subways, power stations, and railway terminals.

But there the revolt halted, because in the America, which had so warmly praised itself for its "widespread popular free education," there had been so very little education, widespread, popular, free, or anything else, that most people did not know what they wanted— indeed knew about so few things to want at all.

There had been plenty of schoolrooms; there had been lacking only literate teachers and eager pupils and school boards who regarded teaching as a profession worthy of as much honor and pay as insurance-selling or embalming or waiting on table. Most Americans had learned in school that God had supplanted the Jews as chosen people by the Americans, and this time done the job much better, so that we were the richest, kindest, and cleverest nation living; that depressions were but passing headaches and that labor unions must not concern themselves with anything except higher wages and shorter hours and, above all, must not set up an ugly class struggle by combining politically; that, though foreigners tried to make a bogus mystery of them, politics were really so simple that any village attorney or any clerk in the office of a metropolitan sheriff was quite adequately trained for them; and that if John D. Rockefeller or Henry Ford had set his mind to it, he could have become the most distinguished statesman, composer, physicist, or poet in the land.

Even two-and-half years of despotism had not yet taught most electors humility, nor taught them much of anything except that it was unpleasant to be arrested too often.

So, after the first gay eruption of rioting, the revolt slowed up. Neither the Corpos nor many of their opponents knew enough to formulate a clear, sure theory of self-government, or irresistibly resolve to engage in the sore labor of fitting themselves for freedom.... Even yet, after Windrip, most of the easy-going descendants of the wisecracking Benjamin Franklin had not learned that Patrick Henry's "Give me liberty or give me death" meant anything more than a high-school yell or a cigarette slogan.

The followers of Trowbridge and General Coon—"The American Cooperative Commonwealth" they began to call themselves—did not lose any of the territory they had seized; they held it, driving out all Corpo agents, and now and then added a county or two. But mostly their rule, and equally the Corpos' rule, was as unstable as politics in Ireland.

So the task of Walt Trowbridge, which in August had seemed finished, before October seemed merely to have begun. Doremus Jessup was called into Trowbridge's office, to hear from the chairman: