Text

Villain Power Scaling (It's over 9000!)

@sarah-sandwich ask and you shall receive

Quick! We wrote an insanely, unexpectedly successful one-off fantasy series! How do we top the villain?

A bigger, badder giant space laser

The villain’s secret jealous sister

The same power, but purple now

The True Mastermind you’ve never heard of

JK, they’re not actually dead!

When you choose to continue on a series and have already committed to possibly destroying the legacy of the characters who fought and died to save the world once by undoing it for money, you had better have a damn good story to tell.

So if you decide your new threat is any of the above, you have quite the uphill battle ahead of you, my friend.

What is Power Scaling?

Power scaling is the nature of the ability of the heroes and the villains to grow more competent over the course of the story via new skills, new powers, or more training. Protagonist’s first fight (that they win, at least) will generally be against a baby, tier-one mook and not up against the main antagonist (*cough* Force Awakens *cough*)

As the story progresses, the mook that was so scary and so hard to beat oh so very long ago will become unnamed cannon fodder in the climax of the story. Generally speaking, this is a linear event and the hero and the villain are constantly one-upping each other until they come head to head in the unavoidable final fight.

Sometimes, things run askew. Maybe the hero’s super special power that saved them last time was a fluke, possible only in those specific circumstances, or one-time use.

Maybe they have amnesia, or the being that gave them that power revoked it, or using it cost them too much. Maybe they got seriously injured in the last fight using it and can no longer go near it if they want to not get hospitalized. Maybe the super power was another character that won the final fight for them last time, but died in the process.

It doesn’t have to be linear, but if you’re going to regress your character without creating a “why didn’t you do what you did last time” plot hole, you will need an ironclad excuse.

So, feast your eyes while I summon the Supernatural fandom back from the dead.

What not to do, as told by Supernatural

This show was originally written to last five seasons and five seasons only. No matter how die hard a fan you are or were, you cannot escape this fact, and neither could the writers.

Season one villain: A demon and her demonic minions

Season two villain: Psychic demon children and Papa Demon Yellow-Eyes

Season three villain: OG Demon Lilith, and Dean’s ticking demon-deal clock

Season four villain: OG Demon Lilith and preventing the rise of Satan

Season five villain: Satan and some douchebag Angels

Then you have Ten. More. Seasons. trying to do better than Satan and the douchebag angels to… varying levels of success and stupidity.

The problem: Supernatural tried to be linear with their power scaling, focusing on ramping up the threat level to nonsensical ends while undermining the threat level of all who came before.

The other problem: Sam, Dean, and Cas never stayed dead long enough for any of these threats to matter.

What I mean is this: In making the threat of the season so impossibly strong, by threatening the world over and over again no matter how many times they save it, by never committing to killing your three most important characters, by never letting the world go a little unsaved in the end, you’re left with a story that *says* it’s bigger, badder, bolder, but is really just a rinse and repeat that goes blander and blander each time.

Coming off Satan and the Douchebag Angels to… Cas and Crowley conspiring over the souls of Purgatory and the unseen war in Heaven because they didn’t have the budget for that, without any of the thematic weight of *why* it was angels and demons? Talk about a loss of momentum.

I rewatch a grand total of one episode of season six, “The French Mistake”. I have lost all context for the plot surrounding this episode and it’s virtually independent of the rest of the season because Sam and Dean get transported into the Real World as Jensen and Jared and poke fun at each other for 52 minutes. This episode is timeless.

The show wasn’t a complete disappointment for the remaining ten seasons or it wouldn’t have lasted that long. It had good beats, but they shot their load in Season Five. After five whole years of buildup to this main event it never recovered.

Alternatives to Linear Power Scaling

Anyone who has or even hasn’t seen Dragon Ball should know that series is famous for infinite power scaling. There’s always someone stronger, always some new secret powerup to unlock with the power of Screaming, always some new Super Sayan color that we promise is more powerful this time, for realsies.

That show is so dedicated to the bit that it’s gone full circle to being loved, not despite it, but because it’s so ridiculous.

You did not write Dragon Ball. Do not do this.

Instead of the infamous clashing multicolored power beams, what other ways can you up the ante of this new threat after your heroes have conquered all they thought stood in their way?

Give a damn good reason why this villain, who is no different than the last schmuck, is unbeatable by the macguffin this time.

As stated above, there’s no need to make the villain More Powerful* if your heroes have lost the world-saving abilities that helped them last time.

Exploit the hero’s other weaknesses

More Powerful* is never as exciting as you think it is. Often times, especially in superhero sequels, the villain isn’t necessarily stronger, but the niche power that they do have finds the chink in the hero’s armor that they didn’t have to worry about last time.

Make the hero’s niche skillset completely irrelevant

This time, the threat might not be something they can punch or shoot or smack with a hammer. This time, it’s their reputation at stake, or the villain is un-punchable because they’re simply unreachable, causing havoc the hero is helpless to stop.

Make the issue not the villain at all, but the hero or their team

Maybe the villain is just a schmuck that would be beatable on any other day, but team infighting means that they make utter asses of themselves and the villain doesn’t have to lift a finger to win because they’ve taken themselves out.

This can get very dramatic like in Captain America: Civil War or the Teen Titans epside "Divide and Conquer". Or, to comedic effect in the Spongebob Episode "Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy V" (the one with the International Justice League of Super Acquaintances).

Some would argue that the above options aren’t power scaling at all if it’s not linear, and that’s fair. You’re telling a story though—is your story going to be about the superpowers and how cool they are, or the people who wield them?

3. It’s not actually power scaling, it’s about stakes

Supernatural began to feel so stale because even though we were told the villain this time was bigger, badder, bolder, the stakes were always the same. OSP has talked about this, how threatening to end the world has a foregone conclusion of “never actually gonna happen” because what author is crazy enough to let the world get blown up and all their characters murdered?

Raising the stakes, too, is not linear. Last time it was the world, this time, it’s the life of the love interest, it’s someone’s sanity, it’s a ticking clock on a secret that’s about to go public.

That’s why the first five seasons of Supernatural were so engaging. Were Demons the problem every time? Yes. The Demons were causing the problem, but they were causing five different problems. It was finding and saving their missing dad, then it was uncovering the sinister plan of the psychic demon children, then it was trying to escape Dean’s deal, then it was trying to stop the rise of Satan, then it was trying to stop the apocalypse. It was not five seasons of demons trying to destroy the world.

The more personal the stakes, the more likely your audience will believe the hero could actually lose this time. That’s what will keep them engaged. Dean died at the end of season 3! They lost! There was no escaping that deal. Sure he came back in the pilot of season 4, but the entire 4th and 5th seasons are haunted by Dean’s PTSD and new pessimism about the world given what he’s seen and done in Hell.

4. Threatening the world without destroying a legacy

Covered in this post about timeskips and this post about sequels but it’s too important to not keep repeating.

So. The Star Wars sequels. Rain down your wrath like snow on a hot desert—these movies were a giant mess. The audience sat through six entire movies following the rise, fall, and redemption of one man who died to save his son and the galaxy.

Then, what, twenty years later, absolutely none of it mattered? New space Nazis are out for blood with the same equipment, same weapons, same soldiers, same reach, same motives. Within the theatrical release (because I am not paying money to buy content to do homework to understand a movie made for a layman audience) these movies undermined the legacy of the six that came before it.

It didn’t have to be a new galaxy-ending regime and the same rebels still rebelling for the same reasons—how the heck did they let another empire rise so fast?—it could have started small, inconsequential, and then the actions of the new cast then undermined everything Anakin worked for.

I feel like Mr. Incredible wondering why the world can’t just stay saved for ten minutes.

All of this is salvageable. End the world again if you want. There will always be bad actors out to do bad things, you can’t expect a utopia to last forever. But that bleak reality is for the real world, not fantasy. In fantasy, the sacrifice of beloved characters must matter. Otherwise, what’s the point of their story?

How do you do this?

Make the utopia the old characters died for last up until the new inciting incident, and make sure it’s the new characters’ fault, not just due to the passage of time

Make the villain threaten something other than their legacy

Make that legacy the banner behind which the new cast rallies, determined to make sure it wasn’t in vain

5. Or, burn the world down this time

Some of the best middle beats of a story feature a “did we just lose” moment a la Infinity War. The villain has won, fan favorites are dead, their home is in ashes, and now they’re not only starting from the bottom, they’re doing it with righteous vengeance.

Then the loss of the original character’s legacy *is* the tragedy, instead of a side effect. Then, in a way, they’re still part of the story, a ghost on the sidelines cheering on their successors, and we, the audience, are right beside them.

—

I have a shiny, fresh-off-the-press Insta @chloe_barnes_books now for this blog and my upcoming novel. Go check it out!

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#fantasy#sci fi#heroes and villains#power scaling

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exposition 2: Naming New Characters

This post is brought to you by one of the worst line deliveries in the history of Supernatural: Sam’s reveal of Ruby 2.0 in “Lazarus Rising”. Also a companion post to not playing The Pronoun Game.

—

Introducing new characters to a scene and figuring out the precise moment to announce their name without sounding clunky can be very tricky. So let’s break it down into three scenarios:

Name is known by the narrator to be given in narration

Name is either known by the narrator, to be given in dialogue, or known by another character

Name is not known to anyone in the scene but the new character

Scenario 1: Name via narration

Personally I don’t have any problem whatsoever with: “This is character, they do X.” It’s quick, inoffensive, and doesn’t need to get convoluted and over complicated.

Now, if this is meant to be a reveal to the audience, you’ll have to play the Pronoun Game for a bit until you pull the trigger (so long as it is motivated and reflects back on the characters and isn’t just because the author is bad at suspense), but I’d recommend reworking the scene so your narrator discovers this information with the reader for the lowest risk of confusing your audience.

Generally I think if you introduce a new character into a scene via epithet, then in the next paragraph have the narrator use their name, I think the audience is smart enough to pick up on: “new entity has arrived on stage = unfamiliar name must belong to them” so you can even skip the exposition tag entirely.

The cook returned from the dining room, freshly traumatized by a wild Karen.

Tyler took a breath, steadied themselves, and resumed their station.

Scenario 2: Name via other character, or dialogue

This is the aforementioned Supernatural blunder. There doesn’t appear to be a clip for this specific scene on YouTube so the moment in question:

Ruby: [Walks in through the back door] “Getting pretty slick there, Sam. Better all the time.”

Sam: [Sighs, and contemplates all his life choices that led to this moment] “What the hell’s going on around here, Ruby?” [Pause for dramatic effect and damn-near looks into the camera]

Ruby’s “Sam” is delivered seamlessly and is flavored with some dry wit, in character for Ruby.

Sam, on the other hand, not only pauses before saying her name, but emphasizes her name in a completely unnatural way. I didn't do it justice here explaining how clunky this is, just trust me.

Nothing sounds or reads quite so juvenile like awkwardly tacking on a new character’s name to dialogue when no real person would talk like that. The line serves purely as exposition and it’s glaringly obvious and uncreative?

How to fix? As I said in my other exposition post: Make it motivated. Have the name reveal come with either inflection, tonality, or dual purpose so it’s not just exposition.

Meaning:

Have speaker be trying to get the person’s attention, and call their name

Have the speaker admonish the person, using their name

If this is a happy reunion, have the speaker excitedly exclaim the name

If this is a bad reunion, have the speaker mutter, growl, whisper, or grumble the name

If this is a surprise reunion, have them speak the name like a question

Have the speaker use a nickname the new character doesn’t like, prompting a correction to their real name

Have the speaker blank, prompting the new character to supply it, while offended that they forgot

Have the known character introduce the new character after a few exchanges that isolate the narrator, prompting an explanation a la “Sorry, this is X, they’ve been my friend for years.”

Scenario 3: Name via new character

Very similar to above with the same advice: Make it motivated and double as clueing us in on something either about the new character, or about the characters’ relationship with the scene, or how they see themselves, or how they expect this meeting to go.

If they’re bold, sassy, or snarky, they introduce themselves like they expect their audience to be impressed

Or, if they expect that name to already be known, and are surprised or irritated that they must introduce themselves

Straight up, have someone ask them who they are if they’re not supposed to be there

Or have someone ask them in a social faux pas, blurting out the question and then being embarrassed by doing so

Have the asker be rude, demanding an introduction where it might otherwise not be appropriate

Have them introduce themselves with uncertainty, if they’re shy or unsure about where they’re supposed to be

You get the idea? Whatever it be, make it be in character, and you’ll pull double-duty (as most exposition should) both naming your character and immediately establishing a relationship between your characters.

Scenario 4: When plot demands you must wait

Bonus! This happens when asking for a name would ruin the pacing and be wildly out of place in whatever’s happening (like mid-fight scene), or the narrator is unable to ask for plot reasons.

In which case, this still can pull double-duty by having your narrator come up with their own way of identifying the person: maybe they come up with a cute or insulting nickname, or a unique feature stands out that they’re jealous they don’t have, or there’s an identifiable piece of clothing or uniform to call them by their profession (works well for a group of distinct unknowns), or they’re acting in a suspicious fashion and can be labeled with a derogatory adjective.

At which point, narrator can either sleuth out their name themselves or it falls into one of the previous three scenarios.

Point being, once again, you are establishing a relationship between these two characters as soon as they’re on page together. Your exposition is pulling double-duty.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#character development#exposition#naming characters

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was looking at your posts and they're all really amazing--specifically the 'signs your sequel needs more work' post. would it be okay if i posted it to instagram (crediting/tagging you, obviously)? i run a writing blog and i don't think i could put it as eloquently as you did.

Absolutely!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pronoun Game

*This is not about preferred pronouns, this is writing advice.

I don’t actually know if this is the official term but it’s what we’re going with, otherwise known as contrived vagueness on a character’s identity to keep the secret from the audience.

“You know… ~him~.”

“Who?”

“HIM.”

“One more time.”

“HIIIIIIIM!”

“…”

Stop doing this. No one talks like this. Or at least come up with a better in-universe code name even if it’s just “the client” or “the target.” Anything is better than this glaring contrivance.

It’s not so much the secret name, it’s how clunky the dialogue becomes without it (ignoring when this is done for humor and supposed to be a little ridiculous).

This is a partner post to how to introduce new characters’ names and the point I’ll be making there applies here: exposition, including new character names, should tell us more about your story than just the information within the text.

But first: just stop doing this. Just name the character. Do it. Audiences will be as confused as if you use a vague “he/him they/them she/her,” but at least they have a name to keep track of, even if it’s faceless at the time they hear it.

It doesn’t even work as a mystery. Characters only play when they’re obfuscating the villain. It’s almost never a red herring. Sure you didn’t say the name, but by deliberately hiding it, you’ve shown your hand.

Real people don’t play the pronoun game unless it’s motivated. So? Make it motivated.

Best example in history: He-who-shall-not-be-named

Why? It’s not just a pronoun, it’s got lore and myths and mystery baked into it. There’s a plot-based reason to be vague. Everyone who says this moniker admits they’re at worst terrified of and at best spiteful of its owner.

I have my own "he who shan't be named" and, can confirm, it's born from glorious spite and satisfying to use every time it comes up.

You can’t copy the epithet, but you can learn from it. Give your characters a reason to be vague beyond preserving the secret for the audience.

Names have power, speaking theirs draws too much attention or bad vibes

Character f*cking hates them, and pronouns them out of spite

Character is being vague to mess with the narrator on purpose

Character fears eavesdroppers and is being careful

Character is testing whether they can trust another by being vague and checking if they’re in on the secret

Character is drunk/high/exhausted and cannot remember the name or care about it to save their life

Optional substitutes here can get quite creative, my personal favorite is “what’s-his-nuts” because I like the cadence but you get the idea

All of these reflect back on the story and the world you’ve built, to give an in-universe reason for the obfuscation.

Now stop playing the pronoun game.

—

Thoughts on the shorter format? I can’t tell if #longpost is supposed to be an insult or not. I have a few of these coming.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#exposition#character names

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Worldbuilding Gets Weird

Imagine you’ve created an urban fantasy world. Real countries and landmarks still exist, and your fantasy elements have evolved around it, within it, beneath it. You’ve got your simple yet incredibly robust magic system (which, tbh, tends to be incredibly fun to play with, idiot-proof, and immune to plot holes), your ‘good guys’ and your ‘bad guys’.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument… your bad guys are animal-themed witches. And your good guys are split into two camps: Weapons masters, and their partners who magically transform into those weapons. They fight the witches in a power struggle of a nebulous *madness* that threatens to eat the world.

Also the good guys are led by the Grim Reaper, who has a tweenage son with crippling OCD. The weapons don't just kill people, they consume the souls of evildoers, and witches. Also there’s clowns, straight out of your nightmares, and a handful of wizards. And Excalibur is a person (or at least alive, personhood is up for debate). He will probably call you a fool, then invite you to afternoon tea.

Sound good?

Now for just a little salt to taste.... Both the sun and the moon have faces and are in constant states of laughter. Occasionally, you will hear the sun going hehehehehe. And the mool will drool blood.

Why? Why not? Do the characters ever question this? Nope. Is there ever an explanation? Nope. Do we, the audience, just roll with this? Yup.

Go watch or read Soul Eater and enjoy it as much as the rest of us do.

—

When you’re worldbuilding, don’t be afraid to get positively weird, for no reason and with no explanation. Our sun and moon might not have faces, but reality has plenty of its own weird.

Mushrooms. Platypi (Platypuses? Platypeople?). Everything that lives below the Mezopelagic zone of the ocean. Jellyfish. Cicadas. Superb lyrebirds. That glitch in brain processing called Pareidolia. Using caffeine, nature’s poison, as an energy boost.

And on and on and on.

Don’t be afraid to not explain why your strange world element exists. If its mechanics or lore are central to the plot and could open a plot hole, then, yeah, some rules would be helpful. Otherwise? Let it be.

If your characters roll with the weird, your audience will too. Not every piece of worldbuild has to, or even should, mesh perfectly like a puzzle. Let historical archives contradict each other in laughably absurd ways. Make up a weird plant that just does that. Let the sky turn blood red for 20 minutes a day just because. Don't let anime keep a monopoly on the bizarre.

Get. Weird. Don’t explain or overcomplicate it. Just dream something up, say yeah that exists in my world now, and add it to the page.

#world building#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing#writing a book#writeblr#fantasy#anime#soul eater

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crutch Tropes #1: “I just want to be normal.”

One cannot write a sensical story that is completely devoid of tropes, much less completely immune to the audience presuming tropes whether you intend them or not. In short: Tropes are not, and have never been, the “problem”.

The problem isn’t even that some become clichés. The problem is when writers use tropes in place of actual character development and detail, because they think just stamping the trope on the page suffices. This isn’t usually done maliciously, either, it’s from inexperience at best, or ego at worst.

Every trope can be a writing crutch—as in, its mere existence gives the illusion of depth where there isn’t any—but there’s a whole subset of tropes that become annoying and exhausting clichés when they don’t have to be. I think they can still be implemented as solid story and character choices with a little TLC thrown their way.

I already wrote about lacking buildup for major character beats and how they’re clearly written to make the audience angry or scared or to pick a side or fall in love, and here is one of the most egregious.

—

No one who’s just been shown the secret otherworld of every fantasy reader’s dreams wants to be “normal”. This line gets thrown around to drive early conflict between the reluctant chosen one and their new badass friends, as if entering this new otherworld or accepting these new powers or responsibilities in any way makes their generic and “normal” life worse.

The writer knows this, otherwise they wouldn’t be banking on the super cool awesomeness of the world they just created to sell books.

The best instances of this trope are well into the story where the character can see and has likely suffered the downsides of this otherworld. Or, a seasoned veteran character comes to terms with the fact that they've given their life to this entity and never got the chance to be normal. By that point, the audience is already endeared to them and right in this mess with them. At the start of the story, we have no idea who this person is.

How to fix: These powers/attention/responsibilities are actually a serious threat and detriment to the character’s ability to live their life and being “normal” is something they have actually never known. “Normal” becomes a gift. Or, the character has a very clear idealized “normal” and the plot is in the way of it.

Without this addition, “I just want to be normal” feels empty and cheap, because most of us readers are “normal”, and can’t empathize with a whining protagonist who we all know will come around eventually.

This trope also loses its teeth when the character cannot define what “normal” they want. Many chosen ones are already written in the midst of their tragic backstory and already don’t live an average life compared to the average reader, but they don’t complain about not being “normal” until they’re dragged out of their miserable existence into the way cooler plot.

But many chosen ones are also just average people, who inexplicably turn down amazing adventures because they just… really want to be homecoming queen, or really love slinging burgers, or taking the bus to school, or doing homework. No one with that life wants to be “normal”, and none of those characters ever articulate just what’s so special about this life.

—

Perfect example of both versions of this solution:

Princess and the Frog: Tiana wants to open her restuarant and wants nothing to do with romance or an adventure. Naveen stands in the way of her "normal" every chance he gets. Tiana's quest is never for romance, it's to undo the magic spell that she got dragged into on accident, and romance is just a happy byproduct.

The Lightning Thief: Being a demigod sounds cool, but the survival rate of these tragic heroes into adulthood, much less 16, is very low, and the book narrative makes it very clear that these so-called heroes are really just beasts of burden doing the gods' dirty work. Percy may not want to continue living exactly the way he is, but at the start of the book, he doesn't give a damn about helping his deadbeat godly dad. When he yearns for normalcy, we can all see why.

—

What is their normal and why do they want it? What are they already doing, or what do they wish would happen, to obtain that idyllic normalcy? I wrote this post about humanizing your characters, and if you’re going to write this blip in the hero’s journey, this is your chance to get as vivid and specific as you can about what this character sees as their perfect life.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#character design#character development#hero's journey

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 More Character Types the World Needs More of

Part 1 was specifically character dynamics, but I’m considering this a sequel anyway.

1. Fiercely independent character’s lesson isn’t to “trust people”

I’m not projecting. You’re projecting. There is a divide wide enough to fit the Grand Canyon between “trusting that someone isn’t lying” and “trusting someone to follow through on a promise”. Most dumpster fire attempts at these characters (almost exclusively women) rely solely on mocking them for the former because “not all men” or something.

Being consistently let down in life makes you hesitant to a) gain friends, b) pursue romantic interests, c) maintain familial relationships, d) get excited about any event that demands participation from someone who isn’t you. None of this is simply a bad attitude—it’s a trauma response. There is no lesson to be learned, and not even exposure therapy can help because it’s a real, legitimate, and common stunt people pull, whether they mean it or not.

So write one of these characters and legitimize their fears, give them someone who proves the exception to the rule, but do not let the lesson be “well they just haven’t found the right person yet”. Even the “right person” can let them down. It's about not becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy by sabotaging a good thing to prove it will inevitably go bad.

2. Conventionally attractive men who aren’t horndogs

I’m going to find every way I can to tell you to write more aces. This is to fight the stigma that attractive people must be attracted to people. Give me gorgeous aces and demi’s, men, women, enbys and everyone in between, who put a crap ton of effort into looking their best, and yet happen to not have a very loud libido. They look good for themselves, and not to impress anyone else.

Give me someone who could have anyone they wanted, gender regardless, and just simply has no interest. Or, they do actually have a significant other, but sex, how hot their partner is, or how horny they are, isn’t their internal monologue. I don’t even care if it’s unrealistic, it’s annoying to read.

And, you know, giving men male characters who aren’t thinking about sex all the time can be good, right? Right?

3. Manly warrior men who also write poetry

A.K.A Aragorn, Son of Arathorn. Just give me more Aragorns, period. This dude is either covered in filth, blood, guts, and the last 30 miles of rugged terrain, or singing in Elvish at his own coronation while pink flower petals fall. A man can be both, and still be straight.

A man can also drink Respect Women juice, you know? He ticks off all the boxes—he’s gentle when he needs to be, not afraid to hide his emotions, kind to those who are vulnerable and afraid and need a strong figure to look up to, resolute in his beliefs, skilled and knowledgeable in his abilities without being arrogant or smug, and the first boots on the battlefield, leading from the front.

4. Characters who are characters when no one is watching

This is less a specific type and more a scene that doesn’t get written enough. This whole point comes from Pixar’s Cars. I. Love. This. Movie. It’s not Pixar’s best, for sure, but this is my comfort movie. The best scene, one that’s so unique, is when Doc (aged living legend) thinks he’s alone when he rolls out onto the dirt race track and comes alive tearing around the oval.

This character’s unbridled, unabashed glee and euphoria at proving to himself that he’s still got it, when he’s completely unaware of his audience, is perfection. Not enough credence is given to characters to just… enjoy being themselves. He’s not doing it to prepare for the climactic race, he’s not doing it for the plot, he’s doing it just to do it, not even to prove Lightning wrong—just for himself.

Give your characters a “Doc Racing” scene. Whatever their skill is. Maybe they’re a dancer, a skater, a swimmer, a painter, sprinter. Just let your character love being alive.

5. Characters whose neurodivergence isn't “cute”

A.K.A. Lilo Pelekai from Lilo and Stitch. Really, her relationship with Nani is peak sibling writing. But Lilo herself is just so realistic with how she interacts with the world, how she interprets her relationships with her so-called friends, how she organizes her thoughts and rationalizes what she can’t quite understand, and how friggen smart she is for an… 11-year-old?

But she’s not “cute”. As in, she wasn’t written by generic Suits who were trying to cash in on the ND crowd by writing what they think will sell, but also making her juuust neurotypical enough to still be palatable by the rest of the audience. Lilo’s earnestness is what endears her to everybody. But also, she doesn’t get a free pass for her behavior, either. Her “friends” aren’t forced to accommodate her and Nani isn’t written as the cold-hearted villain for trying to discipline her.

6. Straight male characters with female friends

Am I double-dipping a bit here? Yes. While I completely understand how tempting it can be, this type of character is in dire need of exposure and representation to prove it’s possible. No weird tense moments, no double-glances when she isn’t looking, no contemplations about cheating on his girlfriend (and no insecure jealous girlfriend either). Just two characters who enjoy each other’s company and are able to coexist in a space and be in each other’s spaces without hormones getting in the way. Peak example? Po and Tigress from Kung Fu Panda.

Let these two rely on each other for emotional strength in times of need, let them share inside jokes, let them have a night alone together at a bar, at home, cooking dinner, getting takeout, talking on the patio in a porch swing… with zero “will they/won’t they.”

7. The likable bigot

I’m actually on the fence with this one but it’s something I also don’t see done often enough and I’m adding it for one reason: Bigots aren’t always obvious mustache-twirling villains and the little things they do might seem inconsequential to them, but are still hurtful. So showing these characters is like plopping a mirror down in front of these people and, I don’t know, maybe something will click. They don’t have to be MAGAs to be dangerous, and only writing the extremes convinces the moderates that they aren’t also the problem.

Example: I have a “friend” who recently said something along the lines of “I have lots of gay friends” followed up shortly by “I don’t think this country should keep gay marriage because it’s a slippery slope to legalizing pedophilia.” You know. The quiet part being that she *actually* thinks being gay is as morally abhorrent as being a pedo. But she totally has lots of gay friends. Including one who was driving her during that conversation. (It’s me. Hi. I’m apparently the problem, it’s me.)

She’s absolutely homophobic, but the second she stops announcing it, she’s a very bubbly person. She’s a ~likable~ bigot and thus thinks she can distance herself from the more violent ones.

8. The motherly single father

I say “motherly” merely as shorthand for the vibe I’m going for here. “Motherly” as in dads who aren’t scandalized by the growing pains of their daughters, and who don’t just parent their sons by saying “man up boys don’t cry”. Dads who play Barbie with their kids of either gender. Dads who go to the PTA meetings with all the other Karens and know as much if not more than they do about the school and their kids’ education.

Dads who comfort their crying kids, especially their sons. Dads that take interest in “feminine” activities like learning how to braid their daughter’s hair, learning different makeup brands, going on nail salon trips together. Dads who do not pull out the rifle on their daughter’s new boyfriend and treat her like property. Dads who have guy friends that don’t mock him and call him gay. Dad who does all this stuff anyway and is *actually* gay, too, but the emphasis is on overly sensitive straight men’s masculinity here.

Wholesome dads: a shocking amount of single-parents to female anime protagonists.

9. The parent isn’t dead, they’re just gone

Treasure Planet is an awesome movie in its own right, but what’s even better? This is a Disney movie where the parent isn’t dead, he’s just a deadbeat who abandoned his son and isn’t at all relevant to the plot beyond the hole he left behind for Jim to fill. The only deadbeat dads Disney allows are villains and those guys are very vigorously chasing an aspiration, that aspiration just doesn’t include quality fatherhood. Or motherhood. Disney has yet to write a deadbeat mom, I’m almost certain.

I just wrote a post about the necessity of the “dead parent” cliche, but what is perhaps more relatable because it’s more common, and what earns even more sympathy and underdog points for the protagonist? The hero with the parent who left. Then there’s a whole extra layer of angst and trauma available when your hero can now plague themselves with the question of if the parent leaving is their fault. Death is usually an accident. Choosing to abandon your kid is on purpose.

10. Victim who isn’t victim-blamed or told by their friends (and the narrative) to forgive their abuser

Izuku Midoriya lost so much support from me the moment he told his friend, bearing the consequences of domestic violence across half his face, that Midoriya thinks he’ll be ready soon to forgive his abomination of a father. I am firmly in the “Endeavor is a despicable human and hero” camp and no I’m not taking criticism. I audibly gasped when I heard this line and realized Deku was serious. Todoroki needs friends like the Gaang to remind him that he's allowed to hate the man who's actions caused the burn scar across his f*cking face.

I understand that the mangaka apparently didn’t anticipate the vitriolic backlash toward Endeavor during his debut and reveal of his parenting tactics but the tone-deafness of telling a fifteen year old with crippling emotional management issues and a horrible home life that his abusive dad in any way deserves and is entitled to forgiveness on the grounds of being related is disgusting.

Take it back further to a more famous Tumblr dad: John Winchester. Another despicable human who got retroactively forgiven by his sons after his death in a “he wasn’t so bad, he really did try” campaign. It’s one thing if the character believes it, it’s a whole different matter if the narrative is also pushing this message.

Katara is a perfect example: She lets go of her grudge for her own peace of mind and stops blaming Zuko for something he had no hand in, stops blaming him simply because he’s a firebender and he’s around to be her punching bag. She doesn’t forgive the man who killed her mother, because that man doesn’t deserve her forgiveness. Katara heals in spite of him, not because of him, and had she let him off the hook, she would have gotten an apology for getting caught, not for what he did (which is exactly what happened).

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#character design#character development#aragorn#pixar cars#kung fu panda#lilo and stitch#treasure planet#atla#katara#my hero academia

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 Signs your Sequel Needs Work

Sequels, and followup seasons to TV shows, can be very tricky to get right. Most of the time, especially with the onslaught of sequels, remakes, and remake-quels over the past… 15 years? There’s a few stand-outs for sure. I hear Dune Part 2 stuck the landing. Everyone who likes John Wick also likes those sequels. Spiderverse 2 also stuck the landing.

These are less tips and more fundamental pieces of your story that may or may not factor in because every work is different, and this is coming from an audience’s perspective. Maybe some of these will be the flaws you just couldn’t put your finger on before. And, of course, these are all my opinions, for sequels and later seasons that just didn’t work for me.

1. Your vague lore becomes a gimmick

The Force, this mysterious entity that needs no further explanation… is now quantifiable with midichlorians.

In The 100, the little chip that contains the “reincarnation” of the Commanders is now the central plot to their season 6 “invasion of the bodysnatchers” villains.

In The Vampire Diaries, the existence of the “emotion switch” is explicitly disputed as even existing in the earlier seasons, then becomes a very real and physical plot point one can toggle on and off.

I love hard magic systems. I love soft magic systems, too. These two are not evolutions of each other and doing so will ruin your magic system. People fell in love with the hard magic because they liked the rules, the rules made sense, and everything you wrote fit within those rules. Don’t get wacky and suddenly start inventing new rules that break your old ones.

People fell in love with the soft magic because it needed no rules, the magic made sense without overtaking the story or creating plot holes for why it didn’t just save the day. Don’t give your audience everything they never needed to know and impose limitations that didn’t need to be there.

Solving the mystery will never be as satisfying as whatever the reader came up with in their mind. Satisfaction is the death of desire.

2. The established theme becomes un-established

I talked about this point already in this post about theme so the abridged version here: If your story has major themes you’ve set out to explore, like “the dichotomy of good and evil” and you abandon that theme either for a contradictory one, or no theme at all, your sequel will feel less polished and meaningful than its predecessor, because the new story doesn’t have as much (if anything) to say, while the original did.

Jurassic Park is a fantastic, stellar example. First movie is about the folly of human arrogance and the inherent disaster and hubris in thinking one can control forces of nature for superficial gains. The sequels, and then sequel series, never returns to this theme (and also stops remembering that dinosaurs are animals, not generic movie monsters). JP wasn’t just scary because ahhh big scary reptiles. JP was scary because the story is an easily preventable tragedy, and yes the dinosaurs are eating people, but the people only have other people to blame. Dinosaurs are just hungry, frightened animals.

Or, the most obvious example in Pixar’s history: Cars to Cars 2.

3. You focus on the wrong elements based on ‘fan feedback’

We love fans. Fans make us money. Fans do not know what they want out of a sequel. Fans will never know what they want out of a sequel, nor will studios know how to interpret those wants. Ask Star Wars. Heck, ask the last 8 books out of the Percy Jackson universe.

Going back to Cars 2 (and why I loathe the concept of comedic relief characters, truly), Disney saw dollar signs with how popular Mater was, so, logically, they gave fans more Mater. They gave us more car gimmicks, they expanded the lore that no one asked for. They did try to give us new pretty racing venues and new cool characters. The writers really did try, but some random Suit decided a car spy thriller was better and this is what we got.

The elements your sequel focuses on could be points 1 or 2, based on reception. If your audience universally hates a character for legitimate reasons, maybe listen, but if your audience is at war with itself over superficial BS like whether or not she’s a female character, or POC, ignore them and write the character you set out to write. Maybe their arc wasn’t finished yet, and they had a really cool story that never got told.

This could be side-characters, or a specific location/pocket of worldbuilding that really resonated, a romantic subplot, whatever. Point is, careening off your plan without considering the consequences doesn’t usually end well.

4. You don’t focus on the ‘right’ elements

I don’t think anyone out there will happily sit down and enjoy the entirety of Thor: The Dark World. The only reasons I would watch that movie now are because a couple of the jokes are funny, and the whole bit in the middle with Thor and Loki. Why wasn’t this the whole movie? No one cares about the lore, but people really loved Loki, especially when there wasn’t much about him in the MCU at the time, and taking a villain fresh off his big hit with the first Avengers and throwing him in a reluctant “enemy of my enemy” plot for this entire movie would have been amazing.

Loki also refuses to stay dead because he’s too popular, thus we get a cyclical and frustrating arc where he only has development when the producers demand so they can make maximum profit off his character, but back then, in phase 2 world, the mystery around Loki was what made him so compelling and the drama around those two on screen was really good! They bounced so well off each other, they both had very different strengths and perspectives, both had real grievances to air, and in that movie, they *both* lost their mother. It’s not even that it’s a bad sequel, it’s just a plain bad movie.

The movie exists to keep establishing the Infinity Stones with the red one and I can’t remember what the red one does at this point, but it could have so easily done both. The powers that be should have known their strongest elements were Thor and Loki and their relationship, and run with it.

This isn’t “give into the demands of fans who want more Loki” it’s being smart enough to look at your own work and suss out what you think the most intriguing elements are and which have the most room and potential to grow (and also test audiences and beta readers to tell you the ugly truth). Sequels should feel more like natural continuations of the original story, not shameless cash grabs.

5. You walk back character development for ~drama~

As in, characters who got together at the end of book 1 suddenly start fighting because the “will they/won’t they” was the juiciest dynamic of their relationship and you don’t know how to write a compelling, happy couple. Or a character who overcame their snobbery, cowardice, grizzled nature, or phobia suddenly has it again because, again, that was the most compelling part of their character and you don’t know who they are without it.

To be honest, yeah, the buildup of a relationship does tend to be more entertaining in media, but that’s also because solid, respectful, healthy relationships in media are a rarity. Season 1 of Outlander remains the best, in part because of the rapid growth of the main love interest’s relationship. Every season after, they’re already married, already together, and occasionally dealing with baby shenanigans, and it’s them against the world and, yeah, I got bored.

There’s just so much you can do with a freshly established relationship: Those two are a *team* now. The drama and intrigue no longer comes from them against each other, it’s them together against a new antagonist and their different approaches to solving a problem. They can and should still have distinct personalities and perspectives on whatever story you throw them into.

6. It’s the same exact story, just Bigger

I have been sitting on a “how to scale power” post for months now because I’m still not sure on reception but here’s a little bit on what I mean.

Original: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy New York

Sequel: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy the planet

Threequel: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy the galaxy

You knew it wasn’t going to happen the first time, you absolutely know it won’t happen on a bigger scale. Usually, when this happens, plot holes abound. You end up deleting or forgetting about characters’ convenient powers and abilities, deleting or forgetting about established relationships and new ground gained with side characters and entities, and deleting or forgetting about stakes, themes, and actually growing your characters like this isn’t the exact same story, just Bigger.

How many Bond movies are there? Thirty-something? I know some are very, very good and some are not at all good. They’re all Bond movies. People keep watching them because they’re formulaic, but there’s also been seven Bond actors and the movies aren’t one long, continuous, self-referential story about this poor, poor man who has the worst luck in the universe. These sequels aren’t “this but bigger” it’s usually “this, but different”, which is almost always better.

“This, but different now” will demand a different skillset from your hero, different rules to play by, different expectations, and different stakes. It does not just demand your hero learn to punch harder.

Example: Lord Shen from Kung Fu Panda 2 does have more influence than Tai Lung, yes. He’s got a whole city and his backstory is further-reaching, but he’s objectively worse in close combat—so he doesn’t fistfight Po. He has cannons, very dangerous cannons, cannons designed to be so strong that kung fu doesn’t matter. Thus, he’s not necessarily “bigger” he’s just “different” and his whole story demands new perspective.

The differences between Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi are numerous, but the latter relies on “but bigger” and the former went in a whole new direction, while still staying faithful to the themes of the original.

7. It undermines the original by awakening a new problem too soon

I’ve already complained about the mere existence of Heroes of Olympus elsewhere because everything Luke fought and died for only bought that world about a month of peace before the gods came and ripped it all away for More Story.

I’ve also complained that the Star Wars Sequels were always going to spit in the face of a character’s six-movie legacy to bring balance to the Force by just going… nah. Ancient prophecy? Only bought us about 30 years of peace.

Whether it’s too soon, or it’s too closely related to the original, your audience is going to feel a little put-off when they realize how inconsequential this sequel makes the original, particularly in TV shows that run too many seasons and can’t keep upping the ante, like Supernatural.

Kung Fu Panda once again because these two movies are amazing. Shen is completely unrelated to Tai Lung. He’s not threatening the Valley of Peace or Shifu or Oogway or anything the heroes fought for in the original. He’s brand new.

My yearning to see these two on screen together to just watch them verbally spat over both being bratty children disappointed by their parents is unquantifiable. This movie is a damn near perfect sequel. Somebody write me fanfic with these two throwing hands over their drastically different perspectives on kung fu.

8. It’s so divorced from the original that it can barely even be called a sequel

Otherwise known as seasons 5 and 6 of Lost. Otherwise known as: This show was on a sci-fi trajectory and something catastrophic happened to cause a dramatic hairpin turn off that path and into pseudo-biblical territory. Why did it all end in a church? I’m not joking, they did actually abandon The Plan while in a mach 1 nosedive.

I also have a post I’ve been sitting on about how to handle faith in fiction, so I’ll say this: The premise of Lost was the trials and escapades of a group of 48 strangers trying to survive and find rescue off a mysterious island with some creepy, sciency shenanigans going on once they discover that the island isn’t actually uninhabited.

Season 6 is about finding “candidates” to replace the island’s Discount Jesus who serves as the ambassador-protector of the island, who is also immortal until he’s not, and the island becomes a kind of purgatory where they all actually did die in the crash and were just waiting to… die again and go to heaven. Spoiler Alert.

This is also otherwise known as: Oh sh*t, Warner Bros wants more Supernatural? But we wrapped it up so nicely with Sam and Adam in the box with Lucifer. I tried to watch one of those YouTube compilations of Cas’ funny moments because I haven’t seen every episode, and the misery on these actors’ faces as the compilation advanced through the seasons, all the joy and wit sucked from their performances, was just tragic.

I get it. Writers can’t control when the Powers That Be demand More Story so they can run their workhorse into the ground until it stops bleeding money, but if you aren’t controlled by said powers, either take it all back to basics, like Cars 3, or just stop.

—

Sometimes taking your established characters and throwing them into a completely unrecognizable story works, but those unrecongizable stories work that much harder to at least keep the characters' development and progression satisfying and familiar. See this post about timeskips that take generational gaps between the original and the sequel, and still deliver on a satisfying continuation.

TLDR: Sequels are hard and it’s never just one detail that makes them difficult to pull off. They will always be compared to their predecessors, always with the expectations to be as good as or surpass the original, when the original had no such competition. There’s also audience expectations for how they think the story, lore, and relationships should progress. Most faults of sequels, in my opinion, lie in straying too far from the fundamentals of the original without understanding why those fundamentals were so important to the original’s success.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#sequels#kung fu panda

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

What No One Tells You About Writing #5

Part 4

Part 3

Part 2

Shorter list this time, but longer points. I expect this one to be more divisive, but it is what it is, and this is what ‘no one tells you’ about writing, after all. This one’s all about feedback and how to take it, and give it.

1. Not everyone will like your book, no matter how good it is

I’ve said this before, granted, but sometimes you can have very arbitrary reasons for not liking an otherwise great story. For example: I refuse to watch Hamilton. Why? Because everyone I knew and their dog was trying to cram it down my throat when it came out and I still don’t really like musicals, and didn’t appreciate the bombardment of insisting I’ll like it simply because everyone else does. I’m sure it’s great! I’m just not watching it until I want to watch it.

It can be other reasons, too. I won’t read fanfic that’s written in first person, doesn’t matter how good it is. Someone might not watch a TV show because the primary cast is white or not-white. Someone might not watch a movie because an actor they despise is in it, even if the role is fantastic. Someone might not watch or read a story that’s too heavy on the romance, or not enough, or too explicit. I went looking for beta readers and came across one who wouldn’t touch a book where the romance came secondary in a sci-fi or fantasy novel. Kept on scrolling.

Someone can just think your side character is unfunny and doesn’t hear the same music as everyone else. Someone can just not like your writing style with either too much or not enough fluff, or too much personality in the main narrator. Or they have triggers that prevent them from enjoying it the way you intend.

How someone expresses that refusal is not your job to manage. You cannot force someone to like your work and pushing too hard will just make it worse. Some people just won’t like it, end of story.

2. Criticism takes a very long time to take well

Some people are just naturally better at taking constructive criticism, some have a thick skin, some just have a natural confidence that beats back whatever jabs the average reader or professional editor can give. If you’re like me, you might’ve physically struggled at first to actually read the feedback and insisted that your beta readers color-coded the positive from the negative.

It can be a very steep climb up the mountain until you reach a point where you know you’re good enough, and fully appreciate that it is actually “constructive” and anything that isn’t, isn’t worth your time.

The biggest hurdle I had to climb was this: A criticism of my work is not a criticism of me as a person.

Yes, my characters are built with pieces of my personality and worldview and dreams and ideals, but the people giving you feedback should be people who either already know you as a person and are just trying to help, or are people you pay to be unbiased and only focus on what’s on the page.

Some decisions, like a concerning moral of your story, is inadvertently a criticism of your own beliefs—like when I left feedback that anxiety can’t just be loved away and believing so is a flawed philosophy. I did that with intent to help, not because I thought the writer incompetent or that they wrote it in bad faith.

I’m sure it wasn’t a fun experience reading what I had to say, either. It’s not fun when I get told a character I love and lost sleep over getting right isn’t getting the same reception with my betas. But they’re all doing it (or at least they all should be doing it) from a place of just wanting to help, not to insult your writing ability. Even if your writing objectively sucks, you’re still doing a lot more just by putting words on paper than so many people who can’t bring themselves to even try.

As with all mediums subjects to critique, one need not be an author to still give valuable feedback. I’m not a screenwriter, but from an audience’s standpoint, I can tell you what I think works. Non-authors giving you pointers on the writing process? You can probably ignore that. Non-authors giving you pointers on how your character lands? Then, yeah, they might have an opinion worth considering.

3. Parsing out the “constructive” from the criticism isn’t easy

This goes for people giving it as well. Saying things like “this book sucks” is an obviously useless one. Saying “I didn’t like this story because it was confusing and uncompelling” is better. “I think this story was confusing and uncompelling because of X, and I have some suggestions here that I think can make it better.”

Now we’re talking.

Everyone’s writing style is different. Some writers like a lot of fluff and poetic prose to immerse you in the details and the setting, well beyond what you need to understand the scene or the plot. Their goal is to make this world come alive and help you picture the scene exactly the way they see it in their minds.

There’s writers who are very light on the sensory fluff and poetry, trying to give you the impression of what the scene should look and feel like and letting you fill in the missing pieces with your own vision.

Or there’s stories that take a long time to get anywhere, spending many pages on the small otherwise insignificant slice-of-life details as opposed to laser-precision on the plot, and those who trim off all the fat for a fast-paced rollercoaster.

None of these are inherently bad or wrong, but audiences do have their preferences.

The keyword in “constructive criticism” is “construct”. As in, your advice is useless if you can’t explain why you think an element needs work. “It’s just bad” isn’t helpful to anyone.

When trying to decide if feedback has merit, try to look at whatever the critic gives you and explain what they said to yourself in your own words. If you think changing the piece in question will enhance your story or better convey what you’re trying to say, it’s probably solid advice.

Sometimes you just have to throw the whole character out, or the whole scene, whole plot line and side quest. Figuring out what you can salvage just takes time, and practice.

4. Just when you think you’re done, there’s more

There’s a quote out there that may or may not belong to Da Vinci that goes “art is never finished, only abandoned.” Even when you think your book is as good as it can be, you can still sleep on it and second-guess yourself and wonder if something about it could have been done better or differently.

There is such a thing as too much editing.

But it also takes a long time to get there. Only 10-15% of writing is actually penning the story. The rest is editing, agonizing over editing, re-editing, and staring at the same few lines of dialogue that just aren't working to the point that you dream about your characters.

It can get demoralizing fast when you think you’ve fixed a scene, get the stamp of approval from one reader, only for the next one to come back with valid feedback neither of you considered before. So you fix it again. And then there’s another problem you didn’t consider. And then you’re juggling all these scene bits and moments you thought were perfect, only for it to keep collapsing.

It will get there. You will have a manuscript you’re proud of, even if it’s not the one you thought you were going to write. My newest book isn’t what I set out to write, but if I stuck to that original idea, I never would have let it become the work that it is.

5. “[Writing advice] is more like guidelines than actual rules.”

Personally, I think there’s very few universal, blanket pieces of writing advice that fit every book, no exceptions, no conditions, no questions asked. Aside from: Don’t sacrifice a clear story for what you think is cool, but horribly confusing.

For example, I’m American, but I like watching foreign films from time to time. The pacing and story structure of European films can break so many American rules it’s astonishing. Pacing? What pacing? It’s ~fancy~. It wants to hang on a shot of a random wall for fifteen seconds with no music and no point because it’s ~artsy~. Or there is no actual plot, or arc, it’s just following these characters around for 90 minutes while they do a thing. The entire movie is basically filler. Or the ending is deeply unsatisfying because the hoity-toity filmmaker believes in suffering for art or… something.

That doesn’t fly with mainstream American audiences. We live, breathe, and die on the Hero’s Journey and expect a three-act-structure with few novel exceptions.

That does not mean your totally unique or subversive plot structure is wrong. So much writing advice I’ve found is solid advice, sure, but it doesn’t often help me with the story I’m writing. I don’t write romance like the typical romance you’d expect (especially when it comes to monster allegories). There’s some character archetypes I just can’t write and refuse to include–like the sad, abusive, angsty, 8-pack abs love interest, or the comedic relief.

Beyond making sure your audience can actually understand what you’re trying to say, both because you want your message to be received, and you don’t want your readers to quit reading, there is an audience for everything, and exceptions to nearly every rule, even when it comes to writing foundations like grammar and syntax.

You don’t even have to put dialogue in quotes. (Be advised, though, that the more ~unique~ your story is, the more likely you are to only find success in a niche audience).

Lots of writing advice is useful. Lots of it is contradictory. Lots of it is outdated because audience expectations are changing constantly. There is a balance between what you *should* do as said by other writers, and what you think is right for your story, regardless of what anyone else says.

Just don’t make it confusing.

—

I just dropped my cover art and summary for my debut novel. Go check it out and let me know what you think!

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#editing#constructive criticism

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

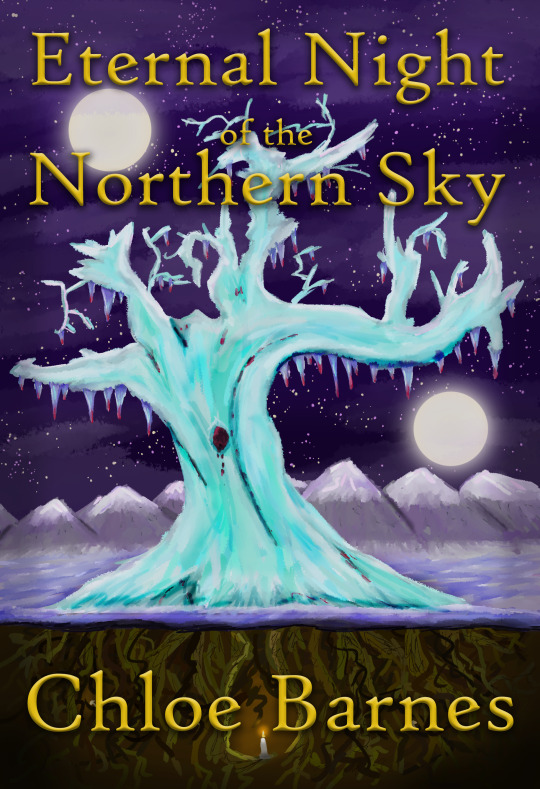

200 Follower Special — Cover Reveal!

I did not think we’d get here this quickly at all! This blog started back in October and I’ve gotten a more positive reception than I ever expected. So in honor of, well, everything, here it is: book title, book cover, and summary!

Eternal Night of the Northern Sky

Art done by yours truly. Thanks to @aneenasevla for the feedback!

—

300 years ago, the vampire covens of the North took the sun from the sky. In the frozen wasteland left behind, clans of the living cling to warmth in a way the vampires never predicted—hunting the undead down for the stolen fire in their veins. When Clan Maewag’s last blood slave takes their own life, Elias joins the hunting party braving the surface and finds himself fighting against vampires for his freedom and right to live.

Conflict brews between a coven thriving on the glittering utopia of equality and a coven enduring on blood slave servitude, with Elias trapped in the middle. What makes a monster in the sunless, frozen North, when survival demands betraying Elias’ home, his people, and every truth he’s ever known?

—

Stay tuned for updates on the novel and website, chapter 1 excerpt, concept art, and release date—tentatively Steptember of this year.

Thanks again for all the support!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me writing a scene with two or more people of the same gender and trying not to get the readers confused, while also trying not to overuse the characters' names or epithets

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hero with Dead Parents is not Cliché, it’s Necessary

The staggering number of protagonists in sci-fi and fantasy with dead parents grows every single year. Frodo Baggins, Harry Potter, Luke Skywalker (before the retcon in ESB), almost every Disney Prince and Princess, the Baudelaire children. Beyond the realm of fantasy into action, thriller, romance, mystery, slice-of-life, and bildungsromans.

Dead parents, or parent, is the curse of being the hero of the story and for a very good reason:

Parents are inconvenient as f*ck.

Unless the mom and/or dad is the villain of the story or the entire story is about the relationship with the parent/parents, the “dead parent” trope serves many purposes and while it may be “cliché” that doesn’t mean this trope is bad or, in my opinion, overused.

It’s one less liability the hero has to worry about protecting

It’s one less obstacle in the hero’s path to their adventure

It’s one (or two) less characters to find excuses to stay relevant in the story

It’s a juicy backstory a lot of people can relate to

Trauma. Is. Compelling.

It’s an excellent motivation

And their murder is an excellent inciting incident

Living parents and guardians get killed off both for internal plot reasons, and meta writing reasons: Living parents are a pain in the ass to keep up with. You’re stuck with a character your hero should still keep caring about, keep thinking about, keep acting in relation to how their actions will be seen and judged by that parent. That parent becomes an obvious liability by any villain who notices or cares.

Living parents can of course be done well, unless they’re the villain, but they just kind of sit there on the fringes of the plot, waiting around to be relevant again and they kind of come in four flavors:

There when the plot demands for pie and forehead kisses (Sally from Percy Jackson)

A suffocating but well-meaning obstacle in between the character and their independence trying to do right (Abby from The 100, Katniss’ mom from Hunger Games, Spirit from Soul Eater)

A mentor figure (Valka from HTTYD 2, Hakoda from ATLA)

The only rock this character has left (Ping from Kung Fu Panda)

*Notice how many of my examples lost their partners shortly before or during the plot, thus still giving the hero the “dead parent” label.

Most of these are self-explanatory so I’ll say this: I think this trope gets exhausting when the parents are written out without enough emotional impact on the hero. These are their parents and a lot of the time, the emotional toll of losing them isn’t there, like just slapping a “dead parents” sticker is all you need to justify a character’s tragic backstory and any behavioral issues they might have.

Like, yes, the hero has dead parents, but you still have to tell me what that means to them beyond obligate angst and sadness. When the “dead parents” trope reads as very by-the-numbers, usually the rest of the story is, too.

How present the parents were in the character’s life should be proportional to the death’s impact on the narrative (as with any character you kill off). If they were virtually nonexistent? No need to waste a ton of time. If they didn’t matter to the character before, they don’t need to matter now unless the plot revolves around some knowledge or secret their parent never shared.

Sometimes, the hero’s dead parents are a non issue. Frodo being raised by Bilbo doesn’t impact his character at all. It’s a detail given and tossed away. On the other hand, sometimes the entire centerpiece of the work is revenge/justice/catharsis surrounding the parent’s death—Edward and Alphonse Elric’s entire story is defined by the consequences of trying to bring their mother back from the dead.

As someone who kept one of my protagonist’s parents alive and didn’t make them villains just to spite the trope, I have all the more respect for this enduring legacy of fiction.

You can of course keep the parents alive, but I don't think it's seen as lazy or cheating or taking a shortcut just killing them off, so long as you remember that your hero is human and should react to losing them like a real person.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#character design#character development#fantasy#scifi#dead parents

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Writing Theme (Or, Make it a Question)

An element of story so superficially understood and yet is the backbone of what your work is trying to say. Theme is my favorite element to design and implement and the easiest way to do that? Make it a question.

A solid theme takes an okay action movie and propels it into blockbuster infamy, like Curse of the Black Pearl. It turns yet another Batman adaptation into an endlessly rewatchable masterpiece, seeing the same characters reinvented yet again and still seeing something new, in The Dark Knight. It’s the spiraling drain at the bottom of classic tragedies, pulling its characters inevitably down to their dooms, like in The Great Gatsby.

Theme is more than just “dark and light” or “good and evil”. Those are elements that your story explores, but your theme is what your story *says* with those elements.

For example: Star Wars takes “dark vs light” incredibly literally (ignoring the Sequels). Dark vs Light is what the movies pit against each other. How the selfish, corrupted, short-sighted nature of the Dark Side inevitably leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy of doom—that’s what the story is about.

A story can have more than one theme, more than one statement it wants to make and more than one question to answer. Star Wars is also about the inevitable triumph of unity and ‘goodness’ over division and ‘evil’.

Part of why I love fantasy is how allegorical it can be. Yes I’m writing a story with vampires, but my questions to my characters are, “What makes a monster? Why is it a monster?” My characters’ arcs are the answer to my theme question.

Black Pearl is a movie that dabbles in the dichotomy between law-abiding soldiers and citizens, and the lawless pirates who elude them. Black Pearl’s theme is that one can be a pirate and also a good man, and that neither side is perfect or mutually exclusive, and that strictly adhering to either extreme will lead you to tragedy.

Implementing your theme means, in my opinion, staging your theme like a question and answering it with as many characters and plot beats as possible. In practice?

Q: Can a pirate be a good man?

A: Jack is. Will is. Elizabeth is. Barbossa is selfish and short-sighted, and he loses. Norrington is too focused on propriety and selfless duty, and he loses.

Or, in Gatsby.

Q: Is life fulfilled by living in the past?

A: Mr. Buchanan clings to his old-money ways and is a sour lout with no respect for anyone or himself. Daisy clings to a marriage that failed long ago, to retain an image and security she thinks she needs. Myrtle chases a man she can’t ever have. Her husband lusts after a wife who’s no longer his. Gatsby… well we all know what happens to him.

The more characters and plot beats you have to answer your theme’s question, the more cohesive a message you’ll send. It can be a statment the story backs up as well, as seen below, questions just naturally invite answers.

—

Do you need a theme?

Not technically, no. Plenty of stories get by on their other solid elements and leave the audience to draw their own conclusions and take their own meaning and messages. Your average romance novel probably isn’t written with a moral. Neither are your 80s/90s action thrillers. Neither are many horror movies. Theme is usually reserved for dramas, and usually in dramatic fantasy and sci-fi, where the setting tends to be an allegory for whatever message the author is trying to send. That, and kids movies.

Sometimes you just want to tell a funny story and you don’t set out with any goals of espousing morals and lessons you want your readers to learn and that is perfectly okay. I still think saying *something* will make the funny funnier or the drama more dramatic or the romance more romantic, but that’s just me and what I like to read.

When it is there, it’s right in front of your face way more often than you might think. Here’s some direct quotes succinctly capturing the main theses of a couple famous works:

“He’s a good man.” / “No, he’s a pirate.” - Curse of the Black Pearl

“What are we holding onto, Sam?” / “That there’s some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for.” - LotR, Two Towers

“Even the smallest person can change the course of the future.” - LotR, Fellowship of the Ring

“A person’s a person, no matter how small.” - Horton Hears a Who

“You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.” - The Dark Knight

“Can’t repeat the past? Why of course you can!” - The Great Gatsby

“Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” & “Life finds a way.” - Jurassic Park

"Ohana means family. Family means nobody gets left behind." - Lilo & Stitch

“But… I’m supposed to be beautiful.” / “You are beautiful.” - Shrek

“I didn’t kill him because he looked as scared as I was. I looked at him, and I saw myself.” - How to Train Your Dragon

“There are no accidents.” & “There is no secret ingredient.” & “You might wish for an apple or an orange, but you will get a peach.” - Kung Fu Panda

*If any of those are wrong, I did them entirely from memory, sue me.

Some of the best scenes in these stories are where the theme synthesizes in direct dialogue. There’s this moment of catharsis where you, the audience, knew what the story has been saying, but now you get to hear it put into words.

Or, these are the lines that stick in your head as you watch the tragedy unfold around the characters and all they didn’t learn when they had the chance.

When it comes to stories that have a very strong moral and never feel like they’re preaching to you, look no further than classic Pixar movies.

“Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.” - Ratatouille

“I’m not strong enough.” / “If we work together, you don’t have to be.” - The Incredibles

“Just keep swimming!” - Finding Nemo

Ellie’s adventure book, to live your own adventure, even if it’s not the one you thought it would be - Up

The Wheel Well montage, to slow down every once in a while, because in a flash, it’ll be gone - Cars

The entire first dialogue-less section of Wall-E, to stop our endless consumption or else

The real monsters are corporate consumption - Monsters Inc

One cannot fully appreciate happiness without a little sadness - Inside Out

With enough loud voices, the common man can overthrow The Man - A Bug’s Life

A person’s worth is not determined by their value to other people - Toy Story

These are the themes that I, personally, took from these movies as a kid and later in life. If I remembered the scripts any better I could probably pull some direct dialogue to support them, but, sadly, I do not have the entire Pixar catalog memorized.

—

After you’ve suffered through rigorous literary analysis classes for years on end, the “lit analyst” hat kind of never comes off. Sometimes you try to find a theme where none exists, coming up with your own. Sometimes you can very easily see the skeleton attempt at having a theme and a message that came out half-baked, and all the missed opportunities to polish it.

Whatever the case, while theme isn’t *necessary*, having that through line, an axis around which your entire story revolves, can be a fantastic way to examine which elements of your WIP aren’t meshing with the rest, why a character is or isn’t clicking, how you want to end it, or, even, how you want to approach a sequel.

Unfortunately, very, very often, a movie, book, or season of TV has a fantastic execution of a theme in its first run, and the ensuing sequels forget all about it.

No one here is going to defend Michael Bay’s Transformers movies as cinematic masterpieces, however, the first movie did actually have a thematic through line: “No sacrifice, no victory.” They didn’t stick the landing but, you know, the attempt was made. Where is that theme at all in the sequels? Nonexistent. They could have even explored a different theme and they abandoned it altogether.

Black Pearl’s thematic efforts fell away to lore and worldbuilding in its two sequels. Not that they’re bad! I love Dead Man’s Chest, but to those who don’t like the sequels, that missing element may be part of why.