#exposition

Text

The Pronoun Game

*This is not about preferred pronouns, this is writing advice.

I don’t actually know if this is the official term but it’s what we’re going with, otherwise known as contrived vagueness on a character’s identity to keep the secret from the audience.

“You know… ~him~.”

“Who?”

“HIM.”

“One more time.”

“HIIIIIIIM!”

“…”

Stop doing this. No one talks like this. Or at least come up with a better in-universe code name even if it’s just “the client” or “the target.” Anything is better than this glaring contrivance.

It’s not so much the secret name, it’s how clunky the dialogue becomes without it (ignoring when this is done for humor and supposed to be a little ridiculous).

This is a partner post to how to introduce new characters’ names and the point I’ll be making there applies here: exposition, including new character names, should tell us more about your story than just the information within the text.

But first: just stop doing this. Just name the character. Do it. Audiences will be as confused as if you use a vague “he/him they/them she/her,” but at least they have a name to keep track of, even if it’s faceless at the time they hear it.

It doesn’t even work as a mystery. Characters only play when they’re obfuscating the villain. It’s almost never a red herring. Sure you didn’t say the name, but by deliberately hiding it, you’ve shown your hand.

Real people don’t play the pronoun game unless it’s motivated. So? Make it motivated.

Best example in history: He-who-shall-not-be-named

Why? It’s not just a pronoun, it’s got lore and myths and mystery baked into it. There’s a plot-based reason to be vague. Everyone who says this moniker admits they’re at worst terrified of and at best spiteful of its owner.

I have my own "he who shan't be named" and, can confirm, it's born from glorious spite and satisfying to use every time it comes up.

You can’t copy the epithet, but you can learn from it. Give your characters a reason to be vague beyond preserving the secret for the audience.

Names have power, speaking theirs draws too much attention or bad vibes

Character f*cking hates them, and pronouns them out of spite

Character is being vague to mess with the narrator on purpose

Character fears eavesdroppers and is being careful

Character is testing whether they can trust another by being vague and checking if they’re in on the secret

Character is drunk/high/exhausted and cannot remember the name or care about it to save their life

Optional substitutes here can get quite creative, my personal favorite is “what’s-his-nuts” because I like the cadence but you get the idea

All of these reflect back on the story and the world you’ve built, to give an in-universe reason for the obfuscation.

Now stop playing the pronoun game.

—

Thoughts on the shorter format? I can’t tell if #longpost is supposed to be an insult or not. I have a few of these coming.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#exposition#character names

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe Rousseau, 1816-1887 - The rat who withdrew from the world

#bizarre au havre#artist#art#painter#rat#exhibition#animal#animals in art#philippe rousseau#artiste#peintre#exposition#l'animal dans l'art

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

When to Info Dump

I was taught as a young writer to never ever ‘info dump’. An info dump is a paragraph (or several) that just runs the readers through info they need to know. While avoiding info dumps is typically a good practice—lots of information at once can be overwhelming, boring, or ‘cheap’—as with most things in writing, never say never. Recently, I finished a book that info dumps often, and with intention, and it worked.

To info dump well, you actually have to do it often (or relatively often). Just one info dump somewhere in the middle or beginning of the story is going to seem like a mistake. Using it as a literary technique however, and it adds a sort of intrigue, whimsy, or discordant tone to your story.

In this way, it becomes a quirk of your narrator’s voice. It should match or make sense with the character you are following. A super serious, meticulous character may info dump in the way they would list off the information they know. A more bubbly character may info dump out of excitement to share their interests.

Which brings us to the type of information you can reasonably info dump without getting in trouble. Of course, the information shared should be stuff that your character would know, but also, information that they would care to share.

For example, that serious character would info dump only pertinent, personally important information, whereas the bubbly character probably wouldn’t info dump about real estate or politics—unless of course it’s part of their special interests. A detail oriented character may only info dump about things they are noticing in the moment. A history buff would definitely info dump about culture and the past.

Essentially, use the right amount, for the right character, with the right information, and you can pull off an intentional and well-done info dump. Otherwise, avoid it!

�� What are your thoughts on exposition or info-dumping?

#writing#writers#writing tips#writing advice#writing inspiration#creative writing#writing community#books#film#filmmaking#screenwriting#novel writing#fanfiction#writeblr#info dump#exposition#when to info dump

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

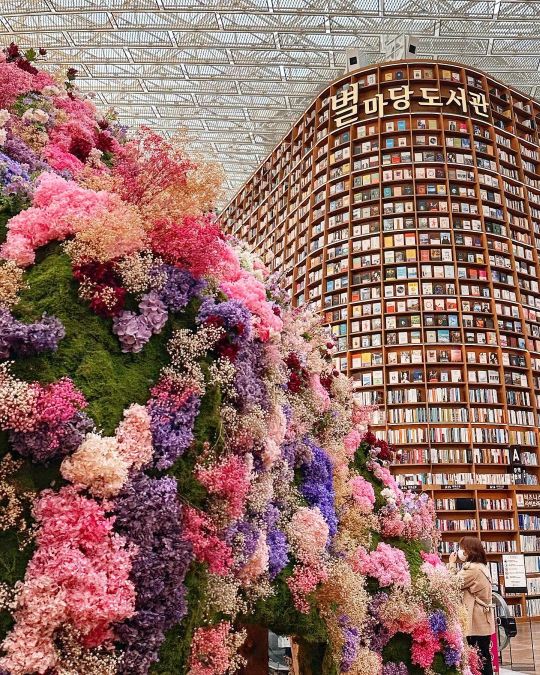

by melodyinsoko

#seoul#south korea#korea#book store#aesthetic#light academia#exposition#cottagecore#fairycore#flowers#photography#curators on tumblr#up

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

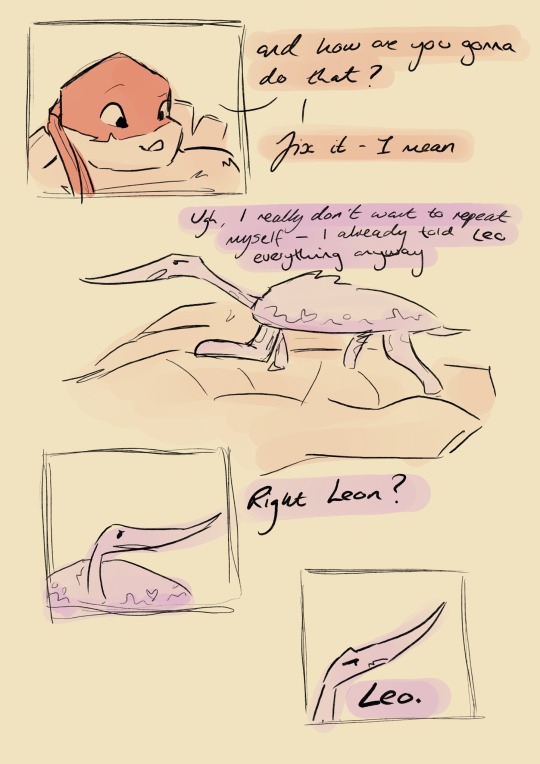

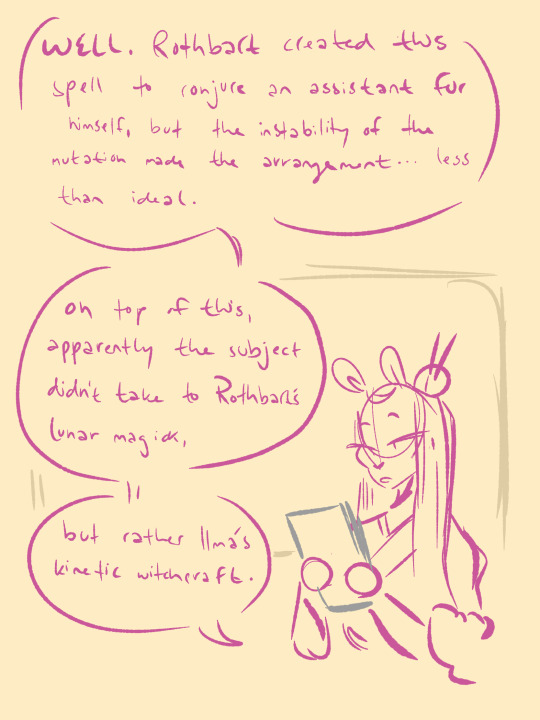

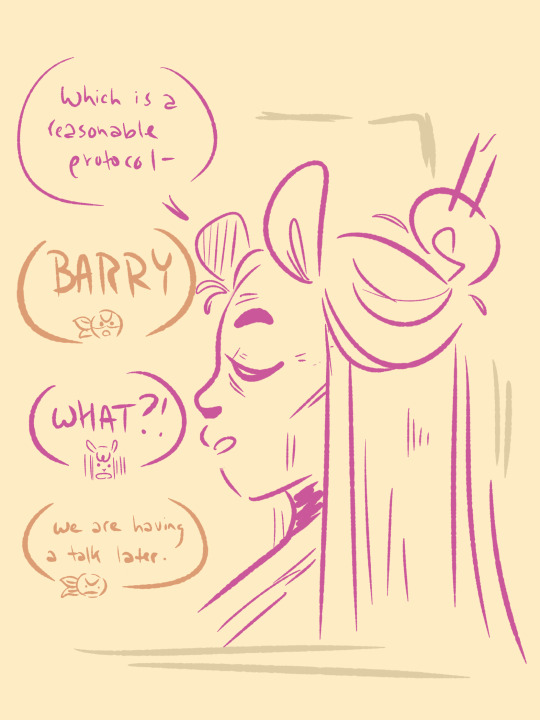

Part 11

(Prev) (First)

Leo your ADHD is showing

(Next)

#next part:#exposition#omg plot incoming#rottmnt#unmutated donnie au#rottmnt donnie#rottmnt donatello#rottmnt mikey#rottmnt michelangelo#rottmnt leo#rottmnt leonardo#rottmnt raphael#rottmnt raph#unmutated donnie comic

918 notes

·

View notes

Text

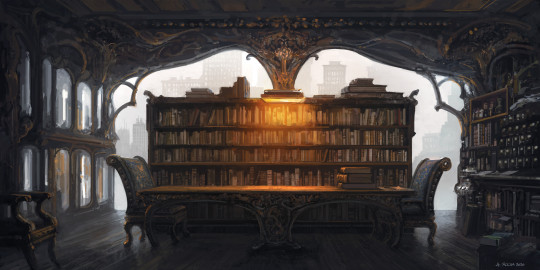

Homebrew Mechanic: Meaningful Research

Being careful about when you deliver information to your party is one of the most difficult challenges a dungeonmaster may face, a balancing act that we constantly have to tweak as it affects the pacing of our campaigns.

That said, unlike a novel or movie or videogame where the writers can carefully mete out exposition at just the right time, we dungeonmasters have to deal with the fact that at any time (though usually not without prompting) our players are going to want answers about what's ACTUALLY going on, and they're going to take steps to find out.

To that end I'm going to offer up a few solutions to a problem I've seen pop up time and time again, where the heroes have gone to all the trouble to get themselves into a great repository of knowledge and end up rolling what seems like endless knowledge checks to find out what they probably already know. This has been largely inspired by my own experience but may have been influenced by watching what felt like several episodes worth of the critical role gang hitting the books and getting nothing in return.

I've got a whole write up on loredumps, and the best way to dripfeed information to the party, but this post is specifically for the point where a party has gained access to a supposed repository of lore and are then left twiddling their thumbs while the dm decides how much of the metaplot they're going to parcel out.

When the party gets to the library you need to ask yourself: Is the information there to be found?

No, I don't want them to know yet: Welcome them into the library and then save everyone some time by saying that after a few days of searching it’s become obvious the answers they seek aren’t here. Most vitally, you then either need to give them a new lead on where the information might be found, or present the development of another plot thread (new or old) so they can jump on something else without losing momentum.

No, I want them to have to work for it: your players have suddenly given you a free “insert plothook here” opportunity. Send them in whichever direction you like, so long as they have to overcome great challenge to get there. This is technically just kicking the can down the road, but you can use that time to have important plot/character beats happen.

Yes, but I don’t want to give away the whole picture just yet: The great thing about libraries is that they’re full of books, which are written by people, who are famously bad at keeping their facts straight. Today we live in a world of objective or at least peer reviewed information but the facts in any texts your party are going to stumble across are going to be distorted by bias. This gives you the chance to give them the awnsers they want mixed in with a bunch of red herrings and misdirections. ( See the section below for ideas)

Yes, they just need to dig for it: This is the option to pick if you're willing to give your party information upfront while at the same time making it SEEM like they're overcoming the odds . Consider having an encounter, or using my minigame system to represent their efforts at looking for needles in the lithographic haystack. Failure at this system results in one of the previous two options ( mixed information, or the need to go elsewhere), where as success gets them the info dump they so clearly crave.

The Art of obscuring knowledge AKA Plato’s allegory of the cave, but in reverse

One of the handiest tools in learning to deliver the right information at the right time is a sort of “slow release exposition” where you wrap a fragment lore the party vitally needs to know in a coating of irrelevant information, which forces them to conjecture on possibilities and draw their own conclusions. Once they have two or more pieces on the same subject they can begin to compare and contrast, forming an understanding that is merely the shadow of the truth but strong enough to operate off of.

As someone who majored in history let me share some of my favourite ways I’ve had to dig for information, in the hopes that you’ll be able to use it to function your players.

A highly personal record in the relevant information is interpreted through a personal lens to the point where they can only see the information in question

Important information cameos in the background of an unrelated historical account

The information can only be inferred from dry as hell accounts or census information. Cross reference with accounts of major historical events to get a better picture, but everything we need to know has been flattened into datapoints useful to the bureaucracy and needs to be re-extrapolated.

The original work was lost, and we only have this work alluding to it. Bonus points if the existent work is notably parodying the original, or is an attempt to discredit it.

Part of a larger chain of correspondence, referring to something the writers both experienced first hand and so had no reason to describe in detail.

The storage medium (scroll, tablet, arcane data crystal) is damaged in some way, leading to only bits of information being known.

Original witnesses Didn’t have the words to describe the thing or events in question and so used references from their own environment and culture. Alternatively, they had specific words but those have been bastardized by rough translations.

Tremendously based towards a historical figure/ideology/religion to the point that all facts in the piece are questionable. Bonus points if its part of a treatise on an observably untrue fact IE the flatness of earth

#homebrew mechanic#d&d mechanics#research#tableskills#tabletop inspiration#dm tip#dm advice#exposition

452 notes

·

View notes

Note

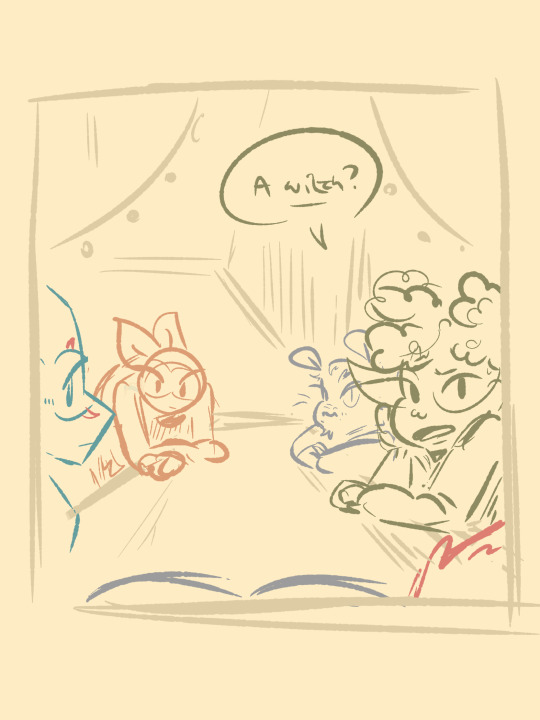

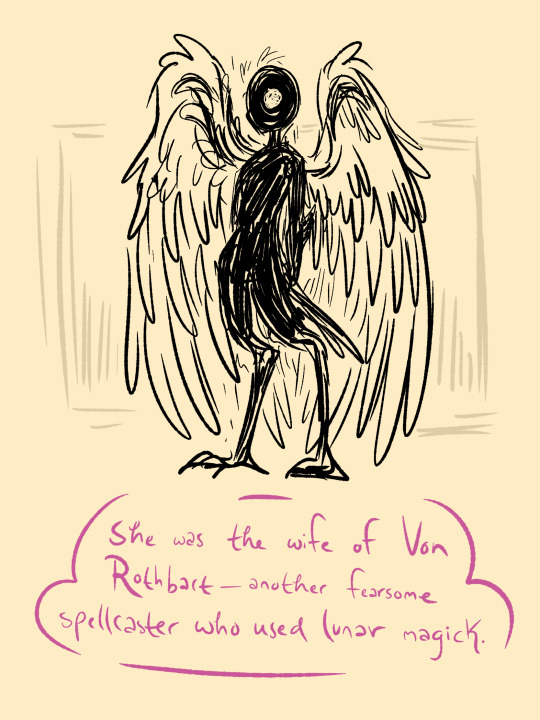

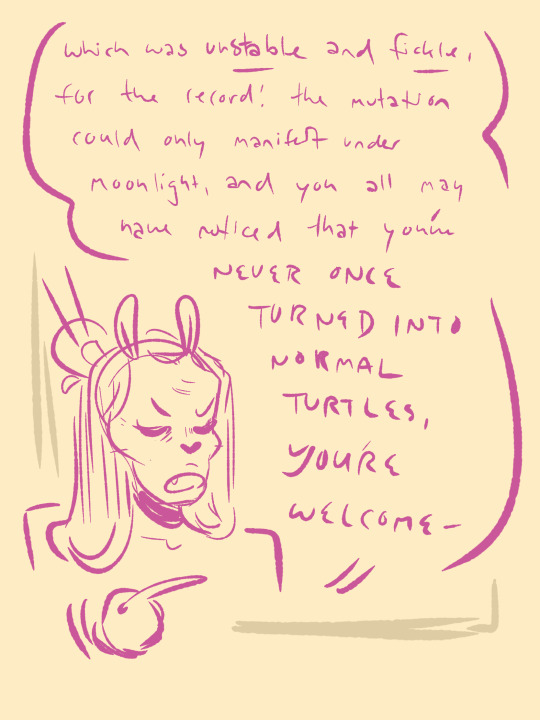

Here's the piece of Swanatello lore I can't make fit: why did the lake call him Othello? Why that name?

[ prev ]

swanatello.

[ start ] [ prev ] [ next ]

#god fucking#EXPOSITION#wipes brow#swanatello#rottmnt#rottmnt au#rottmnt comic#rise of the tmnt#rise of the teenage mutant ninja turtles#tmnt#tmnt 2018#donniesona#fidgetwing

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexová & Smetana, Moravská galerie Brno

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Exposition Ever Good? 4 Pros and Cons of Catching Your Readers Up to Speed

People often mention exposition as a bad thing. Can it ever work in a story? Here are a few things you need to know about writing exposition so you can use it purposefully or avoid it in your upcoming work.

What Is Exposition?

Exposition is any dialogue or part of a story that catches the reader up on what already happened. It’s received a bad reputation in the writing community, but it can serve a few purposes if done well.

Basically, imagine starting a chapter with the summary on the book’s jacket. Except sometimes that summary fits in other parts of the story.

Pros and Cons of Exposition

Pro: Readers Get a Recap

When you’re six books deep in a 10-book series, a little recap in the first chapter is very much needed. It’s even good when you’re starting a sequel. Readers aren’t going to remember every plot detail, rivalry, and moment of character development.

You’ll likely read it in the first chapter something like this:

Chapter One

I couldn’t believe I made it off that mountain, even weeks after scaring residents in the valley village of Straw Hollow. The blackened chunks of my face I nearly lost to frostbite would have been scary enough, but they also had to rush me to their physician with a bear trap around my ankle.

It was all worth it though. I’d left my hometown six months prior to find my sister on the top of that mountain. I’d rescued her and pulled her back with me on a makeshift sled of pine branches.

She was alive. That was all that mattered.

Until I woke up in the physician’s cabin and saw a poster hanging across the room. It had my face on it, along with a bounty of $5 million.

That summary doesn’t include every detail from the first book, but it includes the major points so readers remember why the protagonist left on their quest, what matters most to them (aka, their motivation), and what they’re up against now.

Con: They Don’t Always Need It

Sometimes writers include exposition that summarizes something from a previous chapter. Readers don’t always need that! Unless your last chapter was longer than ~10 pages, they may read your exposition and feel as though you’re talking down to them. The storytelling starts to baby the reader instead of entertaining them.

Even in the case of starting a new book in a series, lengthy exposition might not be necessary. A few quick sentences could summarize your first book and get the reader back in your world if the first book was a mega-hit that people can’t stop talking about.

Pro: Exposition Can Set the Scene

If you’re writing a fast-paced, high-stakes story right from the start, it’s important to set the scene quickly. Your exposition could look like the example above and lead into a fight scene. As soon as the protagonist sees the bounty poster, the physician walks into the room held at knifepoint. The attacker fights the protagonist, who wins—but barely.

It wouldn’t make sense to weave your exposition throughout the first chapter because your reader would quickly get left behind. They wouldn’t enjoy the action or fast pace because they don’t remember what’s at stake for the protagonist or why they’re doing what they’re doing.

Con: It Can Feel Like Page Filler Content

Imagine the first chapter from the example. The writing is exactly the same, but after the protagonist successfully escapes the attacker in the physician’s cabin, they find their sister and hide in a nearby forest. As they’re crouching in the shadows, they start whispering to each other.

“What happened in there?” my sister asked.

"I just woke up in that physician's cabin," I replied. "I remembered walking into the village and even checked for the bear trap. My ankle is in this hard cast now, so it's okay. But then I saw a poster with a bounty of $5 million. Whoever turns me in to the king gets the money. So an assassin held the doctor at knifepoint and I had to fight them off. They landed a few punches, but I think I'm all right. "

“A bounty?” she hissed. We waited for villagers with torches to pass by us before she spoke again. “For $5 million?”

“Yeah,” I confirmed.

“I’m really glad you found me at the top of that mountain and brought me back down on a sled of pine branches, but this is dangerous.”

“I’d do anything for you.”

“And it looks like those villagers would do anything for $5 million.”

That part of the chapter repeats everything the reader just read. The specific bounty price is even mentioned a few times as if the reader's going to forget how much it is between paragraphs. They know all of this information already, so this example of expository dialogue slows the pacing. Even more critically, it bores the reader.

You can also accidentally bore the reader if you’re repeating information that isn’t vital to the story. The next part of that chapter could describe how the sisters wander through the forest. The protagonist watches the stars pass by through the tree branches above and recalls a memory of watching stars with their mother in great detail.

The sister asks what the protagonist is thinking, who describes the memory a second time in exactly the same level of detail.

These situations often create the books we read where we go, “I liked it, but it could have been 100 pages shorter.” That’s likely because there was expository information scattered throughout, either in dialogue, internal monologue, or the storytelling itself.

-----

Don’t be afraid to use exposition when it’s to your reader’s advantage, but remember that it can be easily overdone. Beta readers are a great resource for catching those moments. You can also read the story out loud to hear what you’re repeating.

#exposition#dialogue#storytelling#writing#creative writing#writers of tumblr#writeblr#writing tips#writing advice

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectacle de Vermeer à Van Gogh aux Carrières de Lumières…

#photography#original photography#original photography on tumblr#provence#exposition#les baux de provence

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to handle info dumps that are rehashes for the audience, but needed for the characters

It’s incredibly common to tell a story where character A goes through something that deeply affects them. However, no one but character A and the audience know about this thing. A good portion of the story’s tension will come from the audience waiting to see character A confess the truth of The Thing to another character or even to a larger cast.

However, such info dumps often take a long time to write out in dialogue format and that presents a conundrum for the writer: you need to let character A tell their story in full, but the audience will be bored if you do that. Because the audience already knows the full story and they don’t really want to read a summary of it.

So what do you do?

You use one of my favorite writing techniques! I’ve never seen a name for this thing, so I’m going to call it “emotional exposition”. You can call it whatever you like. The basic idea is this: you skip the dialogue and focus on summarizing the events in an extremely short fashion that evokes the right emotions in the audience.

For example, say Alice saw someone get murdered and she’s kept that secret for a long time. This scene was the book’s opening, though, so the audience knows the full details. Alice is now confessing what happened to her friend, Sarah. Sarah gets the full dialogue and detailed information. The audience gets this:

Sarah watched in silence as Alice rose to her feet and crossed the room, coming to a stop beside the window. For a long while, the young woman didn’t say a word. She just stared out into the night. Finally, just as Sarah was considering saying something, Alice started to talk.

Her voice never rose above a whisper and yet Sarah could hear every word with perfect clarity. She sat there, horror growing, as her best friend spoke of a little girl hiding in a closet, smothering her sobs as a villain took away the only family she’d ever known.

Because the audience already knows what happened, they don’t need to know exactly what Alice is saying. What they need to know is how Sarah is reacting to what she’s being told. That’s why you can do this dialogue skipping thing and just give a brief callback to the events that are being discussed. It’s enough to remind the audience of what happened, but you trust them to remember the important stuff. Then you can move straight to the fallout of Sarah’s reaction to Alice’s confession without bogging the story down by rehashing things the audience already knows.

I use this technique and similar stuff all the time when I’m writing and I highly, highly recommend it. It allows for these emotional moments to be far more impactful because they’re not bogged down in unnecessary details. It also lets you skip over explaining the same thing 10 times even though the characters might need to.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Exposition (Or Turning a Textbook into a Story)

Exposition concerns every facet of your work from character descriptions, backstories, and relationships, to world history, geography, religions/faiths/superstitions, politics, and current events. Whenever the author takes an aside to say “Joe, Bob’s second cousin, said ‘hello’,” the exposition is establishing that Joe is Bob’s cousin.

So shaming a story for its poor handling of exposition is like shaming a movie for bad visual effects. Yes, some of it is probably bad, but I guarantee that you did not notice every single VFX shot in the movie, and you weren’t supposed to.

Most examples of bad exposition occur when the following happens:

Informed Character A exposits to Informed Character B and tacks on “as you know” with full sincerity

Random Important Detail gets dropped in conversation that does not fit the tone or direction of conversation

Character suddenly monologues about The Thing unprompted

Convenient Breaking News Alerts

Character, out-of-character, begins monologuing about The Thing even when prompted

The pacing screeches to a halt so the Exposition Train can thunder past

Exposition exists to give information, and in order for a reader to understand a story, not all of it can or should be agonized over making perfect. Settings have to be established. Character names and relationships have to be understood. “Telling” over “showing” is, in my opinion, perfectly fine when the “showing” would take more lines, effort, and priority over a single inconsequential sentence. Heck, sometimes the “telling” is better than the “showing”. The trick to understanding when, how, and to what degree to give exposition is making it motivated.

What is motivated exposition?

See this post about character descriptions and the plight of the cliche “mirror” trope for unmotivated exposition.

Motivating your exposition means giving it a reason to exist where it does, prompted by the story you’re telling. Citing the “mirror” trope: I can have my character wake up and describe themselves to you, but in doing so, that rarely tells the audience anything more than just what to picture as they read. Or, I can have my character description spread out as those details become relevant. They’re describing their hair color and texture as it begins to irritate or distract them, telling us both what it looks like, and what our character thinks of it, and a little bit about their personality in how they treat it.

I can open the first chapter with a long-winded editorial about the long lost king destined to unite the shattered kingdoms, or I can wait until the tale becomes important to my characters to tell.

I can spin tapestries about politics before you’ve even met your hero, or I can wait until those politics begin to cause the hero problems and then invite the hero to talk about why those politics cause problems.

See this post about pacing and ensuring your scenes always do at least two things at once. Motivated exposition takes bland information’s singular purpose (to inform) and gives it flavor in coloring the personalities of the characters who give and receive it.

When to give exposition

Caveat: Not all front-loaded exposition is poorly-handled. Everyone loves the Star Wars title crawls because they’re a part of the episodic movie experience. Whether it’s a cheap way to deliver information is irrelevant.

Most prologues exist to front-load exposition and, because I love using Lord of the Rings as my shining example in every post, the trilogy opens with a lengthy speedrun of the main villain, some of the important pieces on the chessboard, the importance of the ring, the smeared reputation Aragorn must live up to and repair, and an idea of the stakes should the heroes lose. Not only is it a prologue, it’s a narrated prologue. There’s an impressive amount of information given in not a lot of time.

Last Airbender begins every single episode with a reminder about the 100 year war and the aggression of the Fire Nation and the purpose of the avatar.

With that said, prologues and title crawls are their own tangle of weeds.

As I said above, exposition should be given when the story gives it reason to exist. Don’t talk about the politics until you have a scene where discussing politics is relevant.

If you need to establish your cool, unique magic system, wait until you have a character using that magic and give it in little chewable bites. That character likely isn’t using every trick in the book right then and there. If they wrote Last Airbender as a novel and started explaining the other three bending styles the second Katara levitated some water, it would read sloppy and slog.

Or, leave the exposition as a mystery to be told later. Make your audience crave the hero’s backstory, piecing together little hints throughout the narrative until just the right moment comes along where your hero would realistically start spilling the beans about themselves. Have other characters frustrated at the lack of information. Have other characters missassume and be wrong about the information they think they know.

Have your characters crave knowledge about their world as much as your audience does.

How to give exposition

Exposition can be given three ways: Via the narrator, via dialogue, or via images or texts observed by the narrator (think news broadcasts or the front page of the paper, books, letters, videos, diary pages).

No matter which avenue you give exposition through, the less random it is, the less “hand of the author” the audience sees. Characters given a lucky break by a convenient breaking news alert is a mini deus ex machina —- the heroes do not earn their victory, it’s just given to them. They are not active in the plot making decisions, they are being railroaded by information as it falls into place before them.

Narrated exposition

The narrator’s internal monologue will interrupt the story to explain whatever needs explaining in that moment. The difference between it reading like a textbook and reading like a story is whether or not this information is important to the narrator.

Meaning, what does my hero feel about this new information? Katniss Everdeen in Hunger Games exposits the entire book because she’s alone for a fair chunk of it with no one to talk to, and she’s no stranger to the politics and history of her world. And yet, she has such strong feelings about everything she says that it doesn’t feel like she’s just giving information for the sake of informing. Everything she says and how she says it reflects on her personality and how she views her world.

Dialogue exposition

When Katniss is clueless about the tribute parade process and all the nuances of Capital life, how she asks about this information and how Effie, Cinna, and Haymich tell her also speaks to their personalities and biases about what they’re saying. In essence: Their exposition is in-character, and, thus, services their characters.

This is the complete opposite of when two informed characters exposit to each other information both already know for the sake of the audience because the author has no other way to give said information. A prime example is the hero happening to overhear two minions discussing The Plan dropping lines like “as you know” (which makes it worse every time).

The only time “as you know” works is when it’s in character. As in, the villain expositing to their minion they think is stupid and the minion reacting to that assumption appropriately. Or, the heroes are gathered to discuss The Plan and the leader of the meeting goes “as you know” because that happens in the real world. Bonus points if some characters are irritated by the redundant recap.

Exposition via dialogue also opens the door for lies, half-truths, and characters simply being wrong or blinded by their biases. Or, characters simply being ignorant of the world they live in. In Lord of the Rings, Gandalf is like 3,000 years old and has been all over Middle Earth. It doesn’t break the plot to have Gandalf exposit because he would realistically have witnessed or have deep knowledge about historical events and politics. Aragorn, too, is 87, and has ranged all over the place. He’s the future king and thus had better know his history and politics. Aragorn expositing makes sense.

Say what you will about Last Jedi but it has a prime example of nuanced exposition: Kylo Ren and Luke Skywalker have incredibly different perspectives on if/how Luke attempted murder on his nephew. There’s 3 sides to every story and the audience is never shown the truth. Had this been given in the title crawl, it would have lost much of its potency.

Dialogue also nurtures the relationships between the characters talking. Telling stories brings people together. If a character is sharing their backstory, why are they telling the narrator, and what does this mean to them as they tell it? If a soldier is sharing his grizzled leader’s backstory around a campfire, how does his relationship with his leader impact how he tells that story, what language he uses, how he sounds, the expressions on his face?

Third party exposition

Information given from an object can be incredibly hit or miss, depending on how hard the heroes worked to obtain it, and whether or not the object in question is meaningful to the heroes.

In the Assassin's Creed games, you abandon the gameplay in whatever historical era you're playing in to watch cutscene after cutscene of exposition (specifically referencing the Ezio Trilogy) by characters no one cares about, giving information that no one cares about, when we'd all rather just keep playing the game.

You can literally have a character read from a textbook, logbook, or daily minutes. What matters is how that info reads, and how the character responds to it. Is the information prejudiced or saturated with bigoted language? Is the mere existence of it where it is horrifying?

In the Mines of Moria (Lord of the Rings) Gimli learns that all his kin have been murdered by goblins once he sees their corpses all impaled with goblin arrows. Later, he finds his dead cousin’s crypt containing a dead dwarf cradling a book that tells of the downfall of Moria. The log entry isn’t finished, and the penmanship rapidly degrades as the dwarf writing it likely dies from his wounds, ending with the ominous, “We cannot get out, we cannot get out, they are coming.”

Had Gandalf warned Gimli ahead of time that all the dwarves were dead, or had they never found the crypt or figured out the owners of the arrows and simply were told “oh yeah we’re about to be attacked by goblins, I suspect they’re the reason Moria is a ghost town” that would have lost all emotional impact, and character development for Gimli.

This doesn’t have to be just objects, get creative! Have the hero watch a parody retelling of the Big Event. Have someone tell it like a ghost story around a campfire. Have it be a crazed rant all across live TV that no one takes seriously. Have six different characters remember it differently and all argue over who’s right. Have someone tell it poorly, thinking it “just a stupid rumor”.

When to withhold exposition

Satisfaction is the death of desire and sometimes uncovering the details of an enticing tidbit of information ruins whatever the audience had imagined to fill in the blanks. In terms of “showing” vs “telling” concerning worldbuilding, deciding whether to have a character speak about the information, or actually writing the scene they’re referring to, is entirely dependant on the story you’re telling.

If you are going to write a flashback, or describe a video of the event, that flashback and video has to be *packed* with as much information as you can cram in there as artfully as you can. Flashbacks and dream sequences take up space and entire scenes and settings need establishing so the audience isn’t floating in the ether trying to follow along. Which tends to mean that the meat of the flashback is barely half of the words you’re now forced to read.

Decide how important it is that the audience sees the incident as it happened, versus told in the aftermath through the biases and flawed memory of another character.

Sometimes the fewest amount of words pack the biggest punch. You can have a shattered soldier describe the battle of which they’re the last survivor in gory detail, or you can have them simply say “it was hell” and let the oomph hit in their expression, how their voice cracks, how vacant their eyes look. The injuries they sustained, the traumas visible in how they hold themselves. At that point, the audience can imagine whatever hell they want. At that point, what you are "showing" (the emotional and physical toll taken on the speaker) is likely way more important than the battle itself.

Concerning pacing — no matter how hard you worked on designing your politics and royal lineages and fantasy geography, odds are if that information isn’t important to your characters, it isn’t important to your readers. It’s not motivated.

I love trivia and fantasy maps as much as everyone else, but I like them on the wikis and next to the table of contents, not interrupting an engaging story.

And, give your audience credit where credit is due. How many fan theories stand on the basis of a few scant lines of narration or zoomed-in snippets of background characters (R+L=J anyone?) and pieces of costume? The mystery is what makes it fun, and I just watched the criminally disappointing second adaptation of the Lightning Thief completely robbed of that mystery every chance they had.

—

In short, the amount of exposition isn’t what makes it well or poorly handled, it’s how and when it’s delivered. Inception is my favorite sci-fi movie and the entire script is exposition, but the way it’s given is entertaining. Motivating your details to exist for a reason, to be given exactly when the time is right and not a moment before, is the spoonful of sugar helping the medicine go down.

Make it timely

Make it relevant

Make it important to the cast

Make it earned by the cast

Make it entertaining

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nadia Lee Cohen, (Carole), 2022.

#contemporary art#sculpture#installation#artist#bizarre au havre#exhibition#nadia lee cohen#art contemporain#artiste#exposition

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backstory is Revealed When You Need It, Not Before

Recently I shared my first 30 pages with my writing mentor, and now I'm sharing her advice with all of you (This is part 2! Find part 1 here). She told me my beginning read very slowly because I was giving backstory before it was relevant in the story, rather than intertwining it with the action.

What I mean by that is, I was giving a lot of exposition on my world just through my character noting it to herself. I worried that if I didn’t lay down the basics right away, when I did mention it later it would come as a bad shock to readers.

While that might have a logic to it, it's very slow to read just exposition on the world. To get these details through naturally and when they're relevant, while still conveying them in the beginning, we needed to create a conflict for my main character to react to right away.

This way, I could spend the first couple pages revealing the essentials of my world and main character without halting the pacing to a stop.

Okay, consider these two examples:

Character A avoided the alleyways as they travelled to the store. The city was overrun by gangs who liked to lurk in their dark corners, jumping out at unaware passerby’s for coin or favours.

Vs.

The back of Character A’s neck prickled as they passed an alleyway that swallowed all light. They were steps away when they heard a raspy voice, “don’t you know you gotta pay the fee to pass through our turf?”

How this character resolves this conflict will betray who they are as a person. Do they cower? Do they fight back? Do they reveal they have connections to another gang, or the police?

This little conflict, as well as establishing a vital part of your world and character, should in some small way connect to the bigger conflict up ahead, aka the inciting incident.

In this example, this specific gang would probably be where the main antagonist is from—or the consequences of how they deal with this follow them into the inciting incident in some way.

Backstory only when it’s most relevant, not to anticipate when it will be important later.

Good luck!

#writing#creative writing#writers#screenwriting#writing community#writing inspiration#filmmaking#books#film#writing advice#writing backstory#backstory#exposition#writing exposition#backstory when you need it not before

876 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please stop telling us what shit is and let us discover 😭

I get that the limited time is annoying, but too much exposition is just told :(

Last week a friend and I were talking about how easy the Lotus Hotel bit would be. Take out the 3min exposition at the beginning where they just tell you "Oh no, it's the Lotus Hotel" and put it to the end, there would literally be NO change in the time of the episode, just let them discover "Oh shit, we keep forgetting -WAIT THERE WAS THIS THING ABOUT LOTUS IN MYTHOLOGY WE NEED TO LEAVE!" Like:

We literally have the same thing going on: they enter the Hotel, need to find Hermes, split up. P&A meet with Hermes, Grover meets Augustus and is like "Huh, what's going on -WAIT" but he dismisses/forgets his line of thought. Back to A&P who had the conversation w/Hermes, then we get the "Let's get Grover - wait, who's Grover" convo, they look at each other, realise sth is wrong, find Grover, leave Hotel. THEN we get the explanation on wtf happened. See, no extra time needed, just some rearranging.

Now this episode again, what WAS this opening. You could've just left him out completely, if you just dump all the exposition on us about the dude anyway and he literally plays NO relevance to the plot of the episode.

I liked the rest of the episode, I really did. (Like, the flashbacks to Young!Percy and Sally? Sooo good. Sally's struggle feels so real, so AUTHENTIC! And not just that! The confrontation with Hades? Sooo well done. It happens too often in Movies or Shows that a Misunderstanding just. Isn't explained at all: One party gets angry, doesn't believe the other, it gets loud ... But this. Is was calm. The confusion was so real. The understanding was so real. The entire confrontation regarding this just. It felt so REALISTIC! Aah. Loved the episode over all) But. Just stoooopp with the tell don't show thing you've got going on😭

#percy jackson#pjo tv show#pjo spoilers#exposition#percy jackon and the olympians#annabeth chase#grover underwood#percy and annabeth#percy and grover#grover and annabeth#sally jackson#hades#rick riordan#my post

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

50 notes

·

View notes