#printing press

Text

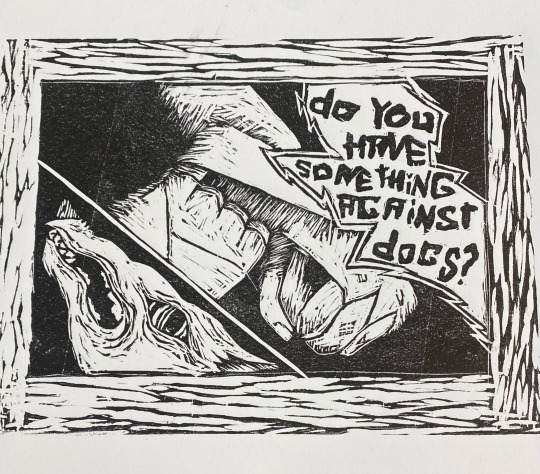

whats with this dog motif?

my 1st time linocut prints, excited 2 play w them more. 9x11", oil ink

#csh#my art#art#queer artist#art student#myart#car seat headrest#csh fanart#carseatheadrest#will toledo#indie music#linocut#linoleum#relief print#prints#printing press#art print#stonehenge

493 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hughnon sighed. "Words are too important to be left to machinery. We've got nothing against engraving, you know that. We've nothing against words being nailed down properly. But words that can be taken apart and used to make other words...well, that's downright dangerous. And I thought you weren't in favor, either?"

"Broadly, yes," said the Patrician. "But many years of ruling this city, Your Reverence, have taught me that you cannot apply brakes to a volcano. Sometimes it is best to let these things run their course. They generally die down again after a while."

"You have not always taken such a relaxed approach, Havelock," said Hughnon.

The Patrician gave him a cool stare that went on for a couple of seconds beyond the comfort barrier.

"Flexibility and understanding have always been my watchwords," he said.

"My god, have they?"

"Indeed."

Terry Pratchett, The Truth

#havelock vetinari#hughnon ridcully#the truth#discworld#terry pratchett#printing press#technology#progress#newspapers#words#power of words#power#change#government#flexibility#understanding#a relaxed approach#brakes on a volcano

286 notes

·

View notes

Text

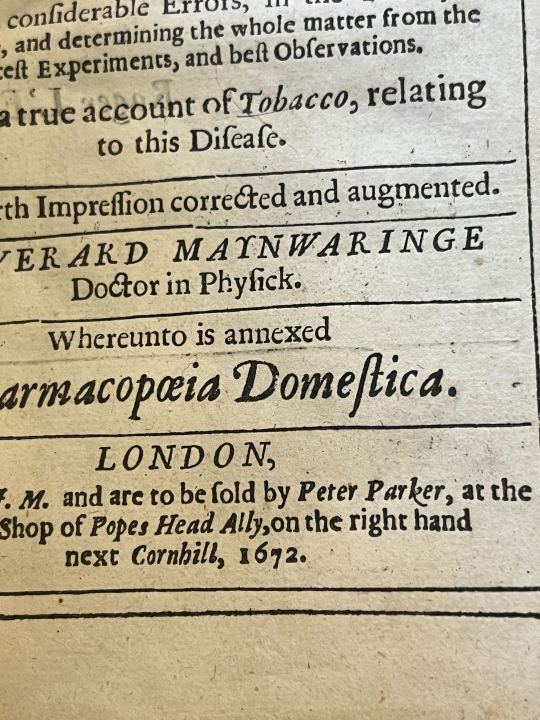

Looks like Peter Parker is both Spiderman and bookseller!

Found in A treatise of the scurvy, examining the different opinions and practice, of the most solid and grave writers... by Everhard Marynwaringe (1672).

#rare books#old books#peter parker#spiderman#booksellers#books#printing press#book history#othmeralia

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

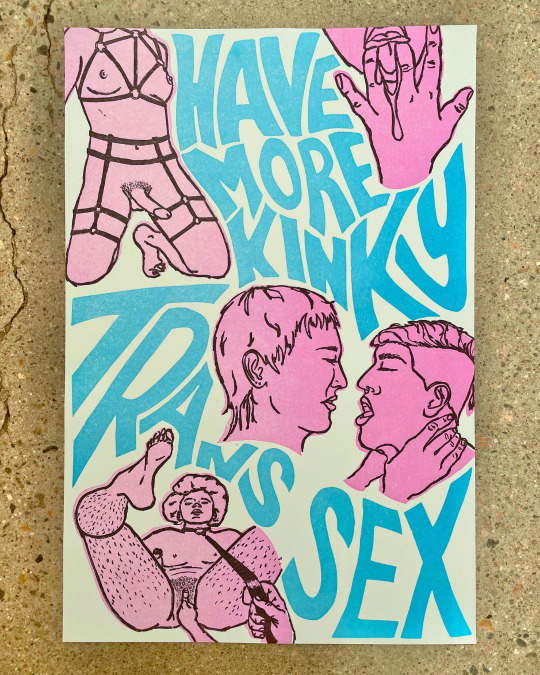

Can't believe this is the only social media site I can post the uncensored version of these prints on, but anyway...

This print is a collaborative project made utilizing linocut and photopolymer plate printing techniques. It emerged out of a conversation one day a few months ago in Nico's living room during a moment of particular grief and fear about the anti-trans hysteria we are living through. It is a straight-forward ode to our love for kinky trans sex and also an expression of our belief in continuing to live full, sexy, love-filled lives in the face of so much violence. You want to get rid of us? Still here, getting freakier.

~~~~

To see the full uncensored version, link in both of our bios!

The illustrations of the bodies were drawn by Celia Palmer and the text and linocut silhouettes were designed and carved by Nico Wilkinson. Nico and Celia printed the posters together on a Vandercook in the Press and Colorado College.

These posters are pay-what-you-can, $20-$50. (Please consider including an additional $5 for shipping!) To purchase your own, Venmo Celia at @celiapalmer with your name and address in the description. Posters will be shipped within two weeks, or are available for local pickup if you live in or near Colorado Springs - for local pickup, please include your phone number in the Venmo description.

The perfect gift for yourself, a friend, or a play partner!

#letterpress#t4t#printmaking#linocut#trans#trans sex#lgbtqia#queer art#queer prints#trans art#vandercook#printing press

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

study i did of a vandercook sp-15 printing press

[ ID: a drawing made with purple pen of a printing press. it is focused on the ink rollers, but the side and bed of the press are visible. the drawing is detailed and takes up most of the page that it is drawn on. ]

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

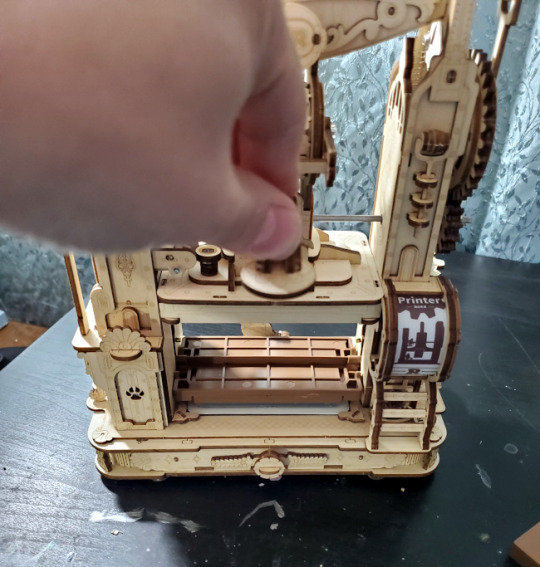

The mini DIY printing press is done! I don't have any batteries atm so no light effects for me.

The press part needed a bit more pressure to produce a good image on the paper, but other than that I think it works pretty well!

#diy#diy kit#printing press#letterpress#those letters are super tiny and will play hide and seek on carpeting

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

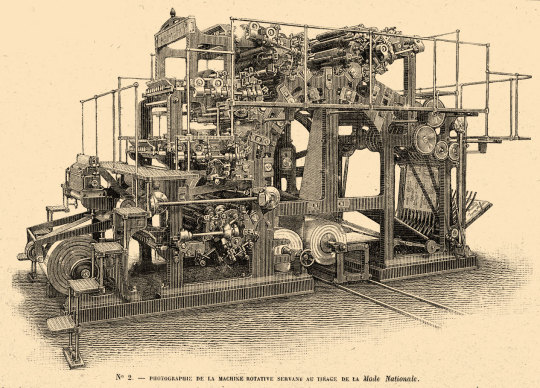

La Mode nationale, no. 3, 21 janvier 1899, Paris. No. 2. — Photographie de la machine rotative sertant au tirage de la Mode Nationale. Bibliothèque nationale de France

#this is the hottest picture i have posted here#look at this absolute unit#La Mode nationale#19th century#1890s#1899#on this day#January 21#periodical#printing press#web printing#design#industrial

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Harrison Ford photographed by Ruven Afanador for Esquire via @rw3ll on instagram]

— WDD

#harrison ford#harrisonford#esquire#esquire magazine#ruven afanador#stunning#photoshoot#photography#photos#interview#article#press#press tour#movie star#celebrity#celebrity interviews#celebrity photoshoot#print#printing#printing press#canvas#art#harrisance#witness the harrisance

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

Pressing matters: vintage printing presses.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

It has taken me a surprisingly long time to appreciate the degree of misunderstanding within this magnet for fantasy, this image of a heroine with superpowers—as witches are portrayed in all dominant cultural productions going. Half a lifetime to understand that, before becoming a spark to the imagination or a badge of honor, the word "witch" had been the very worst seal of shame, the false charge which caused the torture and death of tens of thousands of women. The witch-hunts that took place in Europe, principally during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, occupy a strange place in the collective consciousness. Witch trials were based on wild accusations of night-time flights to reach sabbath meetings, of pacts and copulation with the Devil—which seem to have dragged witches with them into the sphere of the unreal, tearing them away from their genuine historical roots. To our eyes, when we come across her these days, the first known representation of a woman flying on a broomstick, in the margin of Martin Le Franc's manuscript Le Champion des dames (The Champion of Women, 1441-2), appears unserious, facetious even, as though she might have swooped straight out of a Tim Burton film or from the credits to Bewitched, or even been intended as a Halloween decoration. And yet, at the time the drawing was made—around 1440–she heralded centuries of suffering. On the invention of the witches sabbath, historian Guy Bechtel says: "This great ideological poem has been responsible for many murders." As for the sexual dimension of the torture the accused suffered, the truth of this seems to have been dissolved into Sadean imagery and the troubling emotions that provokes.

In 2016, Bruges' Sint-Janshospitaal museum devoted an exhibition to "Bruegel's Witches," the Flemish master being among the first painters to take up this theme. On one panel, he listed the names of dozens of the city's women who were burned as witches in the public square. "Many of Bruges' inhabitants still bear these surnames and, before visiting the exhibition, they had no idea they could have an ancestor accused of witchcraft," the museum's director commented in the documentary Dans le sillage des sorcières de Bruegel. This was said with a smile, as if the fact of finding in your family tree an innocent woman murdered on grounds of delusional allegations were a cute little anecdote for dinner-party gossip. And it begs the question: which other mass crime, even one long past, is it possible to speak of like this—with a smile?

By wiping out entire families, by inducing a reign of terror and by pitilessly repressing certain behaviors and practices that had come to be seen as unacceptable, the witch-hunts contributed to shaping the world we live in now. Had they not occurred, we would probably be living in very different societies. They tell us much about choices that were made, about paths that were preferred and those that were condemned. Yet we refuse to confront them directly. Even when we do accept the truth about this period of history, we go on finding ways to keep our distance from it. For example, we often make the mistake of considering the witch-hunts part of the Middle Ages, which is generally considered a regressive and obscurantist period, nothing to do with us now—yet the most extensive witch-hunts occurred during the Renaissance: they began around 1400 and had become a major phenomenon by 1560. Executions were still taking place at the end of the eighteenth century—for example, that of Anna Göldi, who was beheaded at Glarus, in Switzerland, in 1782. As Guy Bechtel writes, the witch "was a victim of the Moderns, not the Ancients."

Likewise, we tend to explain the persecutions as a religious fanaticism led by perverted inquisitors. Yet, the Inquisition, which was above all concerned with heretics, made very little attempt to discover witches; the vast majority of condemnations for witchcraft took place in the civil courts. The secular court judges revealed themselves to be "more cruel and more fanatical than Rome" when it came to witchcraft. Besides, this distinction is only moderately useful in a world where there was no belief system beyond the religious. Even among the few who spoke out against the persecutions such as the Dutch physician Johann Weyer, who, in 1563, condemned the "bloodbath of innocents"—none doubted the existence of the Devil. As for the Protestants, despite their reputation as the greater rationalists, they hunted down witches with the same ardour as the Catholics. The return to literalist readings of the Bible, championed by the Reformation, did not favor clemency—quite the contrary. In Geneva, under Calvin, thirty-five "witches" were executed in accordance with one line from the Book of Exodus: "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" (Exodus 22:18). The intolerant climate of the time, the bloody orgies of the religious wars—3,000 Protestants were killed in Paris on St. Bartholomew's Day, 1572–only boosted the cruelty of both camps toward witches.

Truth be told, it is precisely because the witch-hunts speak to us of our own time that we have excellent reasons not to face up to them. Venturing down this path means confronting the most wretched aspects of humanity. The witch-hunts demonstrate, first, the stubborn tendency of all societies to find a scapegoat for their misfortunes and to lock themselves into a spiral of irrationality, cut off from all reasonable challenge, until the accumulation of hate-filled discourse and obsessional hostility justify a turn to physical violence, perceived as the legitimate defense of a beleaguered society. In Françoise d'Eaubonne's words, the witch-hunts demonstrate our capacity to “trigger a massacre by following the logic of a lunatic.” The demonization of women as witches had much in common with anti-Semitism. Terms such as witches "sabbath" and their "synagogue" were used; like Jews, witches were suspected of conspiring to destroy Christianity and both groups were depicted with hooked noses. In 1618, a court clerk, whiling away the longueurs of a witch trial in the Colmar region, drew the accused in the margin of his report: he showed her with a traditional Jewish hairstyle, "with pendants, trimmed with stars of David."

Often, far from being the work of an uncouth, poorly educated community, the choice of scapegoat came from on high, from the educated classes. The origin of the witch myth coincides closely with that—in 1454–of the printing press, which plays a crucial role in it. Bechtel describes a "media campaign" which "utilized all the period's information vectors": "books for those who could read, sermons for the rest; for all, great quantities of visual representations." The work of two inquisitors, Heinrich Kramer (or Henricus Institor) from Alsace and Jakob Sprenger from Basel, the Malleus Maleficarum was published in 1487 and has been compared to Hitler's Mein Kampf. Reprinted upward of fifteen times, it sold around 30,000 copies throughout Europe during the great witch-hunts. "Throughout this age of fire, in all the trials, the judges relied on it. They would ask the questions in the Malleus and the replies they heard came equally from the Malleus." Enough to put paid to our idealized visions of the first uses of the printing press! By giving credence to the notion of an imminent threat that demanded the application of exceptional measures, the Malleus Maleficarum sustained a collective delusion. Its success inspired other demonologists, who became a veritable gold mine for publishers. The authors of these contemporary books—such as the French philosopher Jean Bodin—whose writings read like the ravings of madmen, were in fact scholars and men of great reputation, Bechtel emphasizes: "What a contrast with the credulity and the brutality demonstrated by every one of them in their demonological reports."

-Mona Chollet, In Defense of Witches: The Legacy of the Witch Hunts and Why Women are Still on Trial

#mona chollet#witch hunts#womens history#printing press#female oppression#male violence#anti semitism#misogyny#european history

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pátria Printing House, Dombóvár, 1981. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Hold on, hold on," said the Bursar. "Yes, indeed, figuratively a word is made up of individual letters but they have only a--" he waved his long fingers gracefully "--theoretical existence, if I may put it that way. They are, as it were, words partis in potentia, and it is, I'm afraid, unsophisticated in the extreme to imagine that they have any real existence unis et separato. Indeed, the very concept of letters having their own physical existence is, philosophically, extremely worrying. Indeed, it would be like noses and fingers running around the world all by themselves--"

That's three "indeeds," thought William, who noticed things like this. Three "indeeds" used by a person in one brief speech generally meant an internal spring was about to break.

Terry Pratchett, The Truth

#the bursar#william de worde#the truth#discworld#terry pratchett#academics#words#letters#linguistics#semiotics#language#philosophy#meaning#power#theoretical#wizards#magic#printing press#newspaper#extremely worrying#indeed#about to break

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uh oh! What happened here? Seems to be that there was a printing error that caused the typeset or page to slip/move while going through the printing press. What a cool find!

Found in our copy of Manuel du parfumeur (1825).

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

By the seventeenth century this symbolic world had been rendered almost completely unintelligible. There were a number of reasons for this. One important factor was the Protestant reformation: the reformers' attacks on allegorical readings of scripture; the Protestant principle of sola scriptura which denied the possibility of theological truths being represented in nature; an iconoclasm which privileged word over image. Other factors also played a role, including the vast additions to catalogs of creatures that resulted from the discovery of the New World. For these new creatures there were no traditional symbolic associations. Another relevant consideration was the advent of printing, and the growth in literacy which accompanied it. These developments promoted the elevation of written word over visual symbol.

- Peter Harrison ("Linnaeus as the Second Adam? Taxonomy and the Religious Vocation")

#Protestant Reformation#printing press#Age of Exploration#symbolism#iconoclasm#Christianity#history#bestiary

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#WordyWednesday

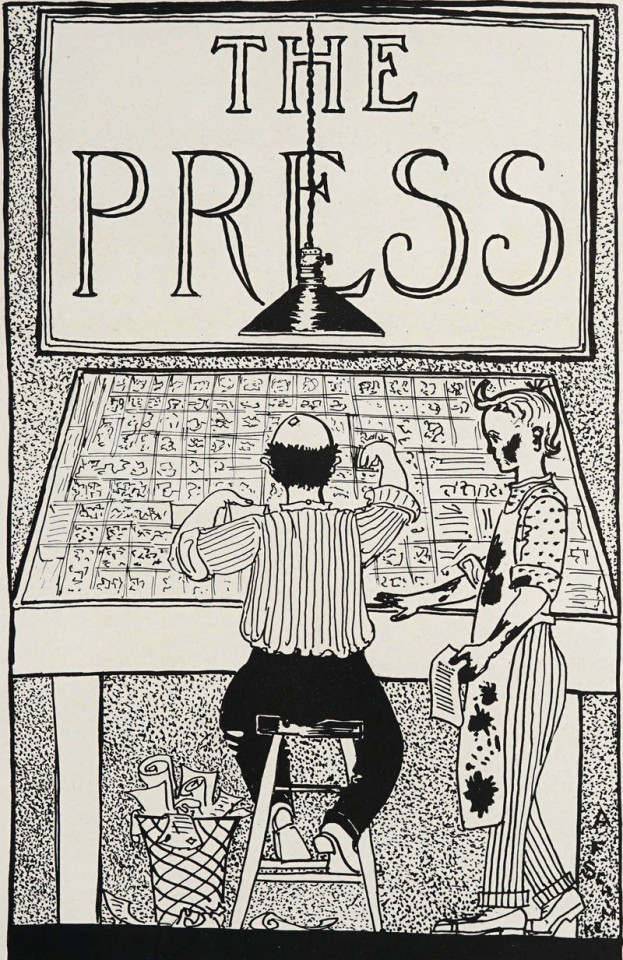

Printing: A term used to refer to the mechanical production of text or images. The word “printing” is derived from words meaning “impression,” referring to the shapes made by seals or stamps on clay or wax. Most forms of printing are a variation on the following procedure: ink or paint is applied to a three-dimensional pattern, which is then pressed against the material intended to be printed. Through contact and pressure, the ink is then transferred to the material, after which point, more ink can be applied to the pattern so that it can be transferred to a new piece of material. The cultural impact of widespread printing is hard to overstate as it allowed the mass production of books and other written materials, turning what had been an expensive luxury good into a cheap commodity.

Image: Garzoni, Tomaso, 1549?-1589. Piazza universale, das ist, Allegemeiner Schawplatz, Marckt, vnd Zusammenkunfft aller Professionen, Kunsten, Geschafften, Handeln, vnd Handtwercken. Frankfurt am Main: In Verlag Matthaei Merians Sel. Erben, Druckts Hieronymus Polich vnd Nicolaus Kuchenbecker, 1659. GT5780 .G315 1659

(via Page — Pulpboard · Rare Books: A Glossary · Special Collections and Archives)

#wordy wednesday#wordywednesday#john henry#special collections#specialcollections#rare books#rarebooks#bookhistory#printing history#illustration#printing#printing press#woodcut

16 notes

·

View notes