#metro man of india

Link

Engineers Day reminds us of the vital role of Engineers in advancing society for being problem solvers and innovators, responsible for designing, creating, and maintaining everything from infrastructure to advanced technology. Their work impacts our daily lives, providing clean water, efficient transportation, and advanced communication systems.

#role of engineers#engineers day celebrations#mechanical engineer#mechanical engineering#verghese kurien#optical engineer#narinder singh kapany#civil engineer#civil engineering#sreedharan#computer engineer#computer engineering#metro man of india#sundar pichai#aerospace engineer#aerospace engineering#apjabdul kalam#famous engineers#indian engineers#Technical Training Promotion#technical training#Contributions of Engineers#Engineering for a Sustainable Future#sustainable future#National Engineer’s Day theme#national engineer’s day#indian engineer#engineers day#sir visvesvaraya#Sir Mokshadgundam Visvesvaraya

0 notes

Photo

“So, what dimension are you from?” ... “Los Angeles.”

Talk about a movie that blew MY BRAIN OUT OF MY SKULL. WOW. So, what was going to be a bg study of LA’s Griffith Observatory turned into Gwen and Miles taking a spidey field trip.

#my fanart#spiderverse#spiderman into the spiderverse#spiderman across the spiderverse#spiderverse spoilers#across the spiderverse#spider gwen#miles morales#spiderverse fanart#fanart#mona lisa#metro boomin#peter b parker#miguel o'hara#spider-man 2099#spider punk#hobie brown#spider man india#pravitr prabhakar#Peter b Parker#beyond the spiderverse#the spot spiderverse#griffith observatory#los angeles#what's up danger#gwen stacy#miles morales fanart#hobie brown fanart#gwen stacy fanart#spiderman 2099

468 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spider Verse soundtrack gon be like “METRO BOOMIN WANT SOME MORE, FELLA!” 😭

#IM EXCITED HUSH#moe rants#into the spider verse#across the spider verse#spiderverse#miles morales#gwen stacy#Peter b Parker#miguel o hara#metro boomin#black twitter#black tumblr#spider man India#spider byte#spider woman#spider women#sony animation#spider man#music

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

India: Alstom to Manufacture 78 Coaches for Chennai Metro Phase II

India: Alstom to Manufacture 78 Coaches for Chennai Metro Phase II

Chennai Metro Rail Limited (CMRL) has selected Alstom to design, manufacture and commission 78 metro coaches to operate on a 26-kilometre corridor between Poonamallee Bypass and Light House.

This second phase of the Chennai Metro will serve 28 stations, 10 of which will be underground.

Under a 98 million EUR contract, Alstom will manufacture 26 driverless metro trains to operate at speeds of up…

View On WordPress

#AC#alstom#bi#Chennai#Connectivity#Control Centre#design#Driverless Metro#Driverless Metro Train#EC#Environment#era#EU#GA#gr#ICE#India#IT#MAN#Metro#Metro Cars#Metro Trains#NEC#News#NS#ORR#People#Proje#RAI#RID

0 notes

Text

Propaganda

María Félix (Doña Barbara, La Mujer sin Alma, Rio Escondido, La Cucaracha)—Maria Felix is still possibly the most well-known Mexican film actress. She turned down multiple-roles in Hollywood and a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer in order to take roles in Mexico, France, and Argentine throughout the 1940s, 50s, 60s. She was so famous and so respected as a dramatic actress that she inspired painters, novelists and poets in their own art--she was painted by Diego Rivera, Jose Orozco, Bridget Tichenor. The novelist Carlos Fuentes used her as inspiration for his protagonist in Zona Sagrada. She inspired an entire collection by Hermes. In the late 1960s Cartier made her a custom collection of reptile themed jewels. She considered herself to be powerful challenger of morality and femininity in Mexico & worldwide--she routinely played powerful women in roles with challenging moral choices and free sexuality. But even still, years after he death, she is celebrated with Google Doodles, and appearances in the movie Coco, and holidays for the anniversary of her death.

Vyjayanthimala (Madhumati, Amrapali, Sangam, Devdas)—Strong contender for /the/ OG queen of Indian cinema for over 2 straight decades. Her Filmfare Lifetime Achievement Award came not a moment too soon with 62 movies under her belt. Singer, dancer, actor, and also has the most expressive set of eyes known to man

This is round 5 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Vyjayanthimala:

Linked gifset

Linked gifset 2

Linked gifset 3

Linked gifset 4

Linked gifset 5

Linked gifset 6

María Félix:

She's Thee Hot Vintage Movie Woman of México. She's absolutely gorgeous and always looks like she's about to step on you. you WILL be thankful if she does.

"María Félix is a woman -- such a woman -- with the audacity to defy the ideas machos have constructed of what a woman should be. She's free like the wind, she disperses the clouds, or illuminates them with the lightning flash of her gaze." - Octavio Paz

María Félix is one of the most iconic actresses of the Golden Era of Mexican Cinema. La Doña, as she was lovingly nicknamed, only had one son, and when her first marriage ended in divorce her ex-husband stole her only child, so she vowed that one day she’d be more influential than her ex and she’d get her son back. AND SHE DID! María Félix rejected a Hollywood acting role to start her acting career in Mexico on her own terms with El Peñón de las Ánimas (The Rock of Souls) starring alongside actor, and future third husband, Jorge Negrete. She quickly rose to incredible heights both in Mexico and abroad, later on rejecting a Hollywood starring role (Duel in the Sun) as she was already committed to the movie Enamorada at the planned filming time. Of this snubbing she said, quote: “I will never regret saying no to Hollywood, because my career in Europe was focused in [high] quality cinema. [My] india* roles are made in my country, and [my] queen roles are abroad.” (Translator notes: here the “india” role means interpreting a lower-class Mexican woman, usually thought of indigenous/native/mixed descent —which she had interpreted and reinvented throughout her acting career in Mexico— and what abroad was typically considered the Mexican woman stereotype, with the braids, long simple skirts, and sandals. This also references the expectation of her possibly helping Hollywood in perpetuating this stereotype for American audiences that lack the cultural and historical contexts of this type of role which would undermine her own efforts against this type of Mexican stereotypes while working in Europe) She was considered one of the most beautiful women in the world of her time by international magazines like Life, París Match, and Esquire, and was a muse to a vast number of songwriters (including her second husband Agustin Lara,), artists, designers, and writers. Muralist Diego Rivera described her as “a monstrously perfect being. She’s an exemplary being that drives all other human beings to put as much effort as possible to be like her”. Playwriter Jean Cocteau, who worked with her in the Spanish film La Corona Negra (The Black Crown) said the following about her, “María, that woman is so beautiful it hurts”. Haute Couture houses like Dior, Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Hérmes, among others, designed and dressed her throughout her life. She died on her birthday, April 8, 2002, at 88 years old, in Mexico City. She was celebrated by a parade from her home to the Fine Arts Palace in the the city’s Historic Downtown, where a multitude of people paid tribute to her. Her filmography includes 47 movies from 1942 until 1970, and only two television acting roles in 1970. She has 2 music albums, one recorded with her second husband, Agustín Lara, in 1964 titled La Voz de María y la inspiración de Agustín «The voice of María and the inspiration of Augustín», and her solo album Enamorada «In Love» in 1998. Her bespoke Cartier jewelry is exhibited alongside Elizabeth Taylor’s, Grace Kelly’s and Gloria Swanson’s. In 2018, Film Director Martin Scorsese presented a restored and remastered version of her film Enamorada in the Cannes Classics section of the Cannes Festival and Google dedicated a doodle for her 104th birthday. On august 2023 Barbie added her doll to the Tribute Collection.

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

they are eepy

i did the thing smile, thanks to @readingrobin for the idea and base!

image id and base under the cut!

[start image IDs]

base; a foto of 2 people in a train / metro . they are sitting in the accessible seat, both are asleep, on sitting with their legs to the walkway in the vehicle . the other has their legs over the plastic barrier and his arm over the back of the seat next to them. they are seemingly not leaning on the person under them.

digital drawing; Hobie Brown also known as ‘spiderpunk’ and Pavitr Prabhakar, the spiderman from ‘Spider-man; India. the two are their alternate version from the Spider-man; across the spiderverse. they are set in the same image as the base foto, hobie as the first person sitting down and Pavitr as the person hanging over the other. they both have their masks off as they are in their spider-man suits. [image IDs end]

#spiderman across the spiderverse#spiderverse#spiderverse meme#spiderverse spoilers#hobie brown#spiderpunk#pavitr prabhakar#spiderman; india#they are friends#they're getting soft tacos later

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

New SpaceTime out Wednesday...

SpaceTime 20231101 Series 26 Episode 131

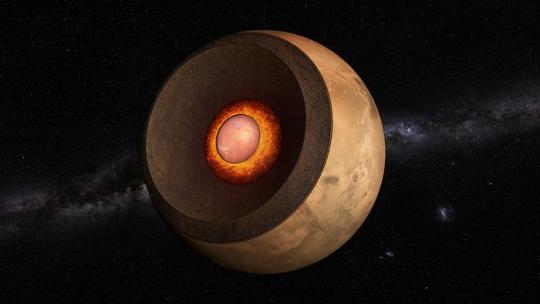

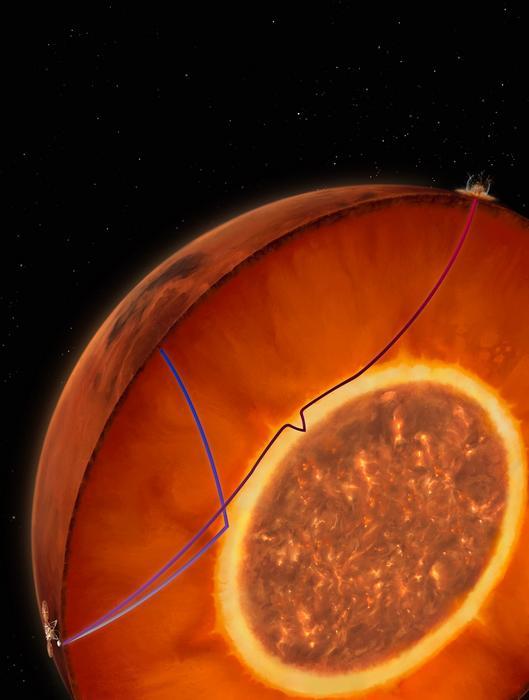

Mystery of the Martian core solved

A new study of data from NASA’s Mars Insight lander mission has concluded that the Martian liquid metallic core is both smaller and denser than previously thought -- but also that it’s surrounded by a layer of molten rock.

Protecting Europa Clipper from Jupiter’s immense radiation

Engineers have just completed the final piece of armour designed to protect NASA’s Europa clipper spacecraft from intense radiation during its mission to explore the Jovian ice moon Europa.

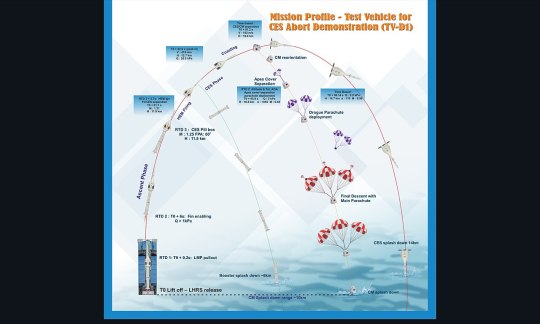

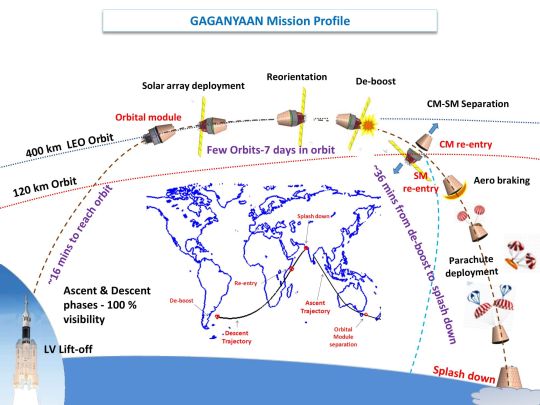

India launches its first crew capsule

India has carried out a successful test flight of its new manned capsule which will the subcontinent’s first astronauts into orbit in 2025.

The Science Report

A new study warns that future increases in ice-shelf melting in the West Antarctic are now potentially unavoidable.

Claims vegetarianism may be partly related to your genes.

Eastern Mediterranean was once a region of green savannahs and grasslands that provided an ideal passage for multiple early human movements out of Africa.

Alex on Tech new AI chips and happy 22nd birthday to the I-pod.

SpaceTime covers the latest news in astronomy & space sciences.

The show is available every Monday, Wednesday and Friday through Apple Podcasts (itunes), Stitcher, Google Podcast, Pocketcasts, SoundCloud, Bitez.com, YouTube, your favourite podcast download provider, and from www.spacetimewithstuartgary.com

SpaceTime is also broadcast through the National Science Foundation on Science Zone Radio and on both i-heart Radio and Tune-In Radio.

SpaceTime daily news blog: http://spacetimewithstuartgary.tumblr.com/

SpaceTime facebook: www.facebook.com/spacetimewithstuartgary

SpaceTime Instagram @spacetimewithstuartgary

SpaceTime twitter feed @stuartgary

SpaceTime YouTube: @SpaceTimewithStuartGary

SpaceTime -- A brief history

SpaceTime is Australia’s most popular and respected astronomy and space science news program – averaging over two million downloads every year. We’re also number five in the United States. The show reports on the latest stories and discoveries making news in astronomy, space flight, and science. SpaceTime features weekly interviews with leading Australian scientists about their research. The show began life in 1995 as ‘StarStuff’ on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) NewsRadio network. Award winning investigative reporter Stuart Gary created the program during more than fifteen years as NewsRadio’s evening anchor and Science Editor. Gary’s always loved science. He studied astronomy at university and was invited to undertake a PHD in astrophysics, but instead focused on his career in journalism and radio broadcasting. He worked as an announcer and music DJ in commercial radio, before becoming a journalist and eventually joining ABC News and Current Affairs. Later, Gary became part of the team that set up ABC NewsRadio and was one of its first presenters. When asked to put his science background to use, Gary developed StarStuff which he wrote, produced and hosted, consistently achieving 9 per cent of the national Australian radio audience based on the ABC’s Nielsen ratings survey figures for the five major Australian metro markets: Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, and Perth. The StarStuff podcast was published on line by ABC Science -- achieving over 1.3 million downloads annually. However, after some 20 years, the show finally wrapped up in December 2015 following ABC funding cuts, and a redirection of available finances to increase sports and horse racing coverage. Rather than continue with the ABC, Gary resigned so that he could keep the show going independently. StarStuff was rebranded as “SpaceTime”, with the first episode being broadcast in February 2016. Over the years, SpaceTime has grown, more than doubling its former ABC audience numbers and expanding to include new segments such as the Science Report -- which provides a wrap of general science news, weekly skeptical science features, special reports looking at the latest computer and technology news, and Skywatch – which provides a monthly guide to the night skies. The show is published three times weekly (every Monday, Wednesday and Friday) and available from the United States National Science Foundation on Science Zone Radio, and through both i-heart Radio and Tune-In Radio.

#science#space#astronomy#physics#news#nasa#esa#astrophysics#spacetimewithstuartgary#starstuff#spacetime

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daydream

(Stargirl Part 2 Modern!Aemond x F!Reader)

A/N: Reader lives in India, but no specification of her family or her appearance is there except for her residence in Delhi and Indian food. Reposting because the tags didn't work

Summary: You are back home, but thank gods for the miracle of texting. Later, Aemond gets a little surprise from his professor.

Word Count: 2.6k (almost)

Series Masterlist | HOTD Masterlist

Two days had passed since that party, and you had packed up to leave for home. After an entire year of grilling, you were finally able to go back to see your family. You still hadn’t reached out to Aemond, though, figuring it would be best to wait until you return. Or if he wanted to speak with you, he had your number.

He hadn’t texted you either.

Although, you kept the napkin with his handwriting in your wallet, looking at it as you sat in waiting for the gates to open. You had called your mother to let her know that you had reached the airport on time, and yes there was still a good hour left before the boarding would start. She said to call her once you were boarded before she hung up.

Next you called your roommate, Casey, and Haelena to let them know that you had safely reached the airport.

It wasn’t until the next morning, when you were in the comfort of your bed in your home, that you received a text from Aemond.

Aemond Targaryen: Hello Y/N. I hope you had a comfortable journey. You: Hey, Aemond! I did, I am with my parents now.

Aemond Targaryen: That’s good to know. Do you have any plans?

You: To sleep away the jet lag and then meet my friends. Do you have any plans for the month-long break?

Aemond Targaryen: Nothing much, just a bunch of family dinners and then I have to visit a historical site.

You: Ohh, that sounds great. Where are you thinking of going? Aemond Targaryen: I haven’t decided yet. Open for any suggestions. You: Well… what are the places that you haven’t been to?

Aemond Targaryen: I have been around Westeros, and seen whatever there is of Essos. I don’t feel like revisiting.

You: I am glad I don’t have such ‘rich people problems’.

Aemond Targaryen: Is that sarcasm that I detect?

You: You tell me, Mister.

You: Okay, my mom’s calling. Ttyl!

Later, you went to bed, tired of the jet lag. The next afternoon, as you were in the metro going to meet your friends, you texted him again.

You: Hello

Then you went to scroll through instagram, and found a new follow request: vhagaristhebest, and you smiled as you accepted the request and sent a request back. His profile picture held his side with the lilac eye and he looked down at his lovely doberman, Vhagar. He is dressed in a dark-grey sweatsuit from what you could make out, hair pushed back from his beautiful face. In your mutuals is shows haelenalovesbugs and heyjacaerys and you grin with your teeth despite yourself.

Your phone buzzes again and you check your messages, and you first text your friends that you are on your way and would be there in forty minutes.

Aemond Targaryen: Took you long enough to speak with your mom. You: I fell asleep. Why are you still awake vhagaristhebest?

Aemond Targaryen: I was up reading, hotgirlslovetoread. What are you doing right now?

You: I am going to meet with some of my friends. Currently in the metro

You: sent a photo

Aemond Targaryen: You look stunning, as usual. Is that the subway? You: Thank you, and yeah. Anyways, what book were you reading? Aemond Targaryen: Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy

You: No way! I love that book. What else does your reading might entail, Mr. Targaryen? Please tell me you love fiction.

Aemond Targaryen: I do, actually. And others, you know the basics - the Picture of Dorian Grey, Harry Potter, Percy Jackson yada yada. You: Percy Jackson is like holy scripture to me.

Aemond Targaryen: I am a religious man then. What do you like to read, Miss?

You: All sorts of things - mostly fantasy though. But I have read a few of the classics. Might I interest you in the Scarlet Pimpernel? Aemond Targaryen: Added to tbr.

You: How chivalrous of you. Alright, I should let you off now. Go to bed and get some rest. I am sure you need your beauty sleep for that flawless skin and hair.

Aemond Targaryen: Shh… Don’t go about spilling my secrets. Take care.

One of your friends entered the metro, and squealed as you hugged her. “King’s Landing seemed to have been kind to you,” she observed.

“And that is the biggest lie,” You said. “It’s all being-back-home. Man, I missed the food there. No one seems to get the paneer tikka right?!”

“Oh, the menace,” She sighed.

.

Half-way across the world, Aemond sat for dinner with his family, constantly checking his phone. Everyone was there: his father, mother, grandfather, step-sister, her husband, and their children. It was a mess, and he only found comfort with Haelena, Daeron and Aegon, as miserable as it was. He was quiet most of the time, keeping to himself like he normally did - only speaking to Haelena or Daeron or answering if he was asked something. He looked around the table once more, Aegon was busy stabbing his food and Haelena and Daeron conversed about something.

He looked at your profile picture for a long moment, admiring the way your hair looked as you faced away from the camera. He refreshed his feed once again, and saw that you had updated a story. With an excited heart, he opened it - finding you with your friends from back home. You were dressed in a green dress that reached a little above your knees and your hair was free of any confines. You looked so different from that night - you had been a temptress that night as you were now - but that night you were a storm, and today you were a gentle wind.

Aemond scrolled through the stories, screenshotting the one you had of yourself. The next picture was with a guy with his arm around you, and he looked at you with a soft smile on his face as you laughed at the camera. There was a sudden pang in his chest, but he ignored it. You wouldn’t have made the move on him if you had a boyfriend, would you?

He decided to reply to the story that you had of yourself. I know I said it already, but I’ll say it again - you look gorgeous, he sent, and put the phone down.

Daeron was applying for his subjects, more interested in Computer Science than finance like their mother wished to. Haelena told him that she had a lovely friend in the department and could speak to her regarding any queries that he had.

Jacaerys, who was seated across from them, looked up at Haelena’s mention of “my lovely friend,” and smiled. “Do you mean Y/N?”

“Oh yeah,” Haelena agreed. “She was a part of your project wasn’t she?”

“Yup,” Jace said, nodding dreamily. “She is so pretty – and of course talented too, she made all of us do the work, stayed up till 4 with us to integrate the Artificial Intelligence bit to the moving parts. Daeron, if you want any help for Computer Science, Y/N should be your favoured contact.”

“What did you say about Y/N?” Aegon asked, and Aemond internally groaned. He knew - 3, 2, 1 – there it was “I am sure Aemond knows a lot about her,” Aegon raised his glass as if for a toast, his brow raised and a smirk plastered on his face. “Don’t you brother? Or were you too busy eye-fucking each other to talk?”

“Aegon!” Their mother looked positively repulsed. “This is no manner of speaking for a man of your stature.”

“I am merely speaking the truth, mother,” Aegon said, shrugging. “Ask Aemond if it’s true or not. Don’t you find Y/N pretty?”

Aemond pursed his lips, glaring at his older brother. “Are you ashamed that she called you bad company?” he said, and their cousins snarked.

At that, the glare he received was full of spite, but Aegon seemed to have calmed down enough to sit back in his seat. He returned stabbing at his food, but Aemond was left to deal with a confused Haelena. “Why didn’t you tell me about this?”

“Haelena, it’s nothing.” He attempted to placate her. “I’ve only seen her at the party, and we exchanged phone numbers. We have barely even talked.”

“Because you were too busy eye-fucking?” Daeron added with a laugh. Aemond rolled his eye, lightly smacking his little brother.

“Oh not you too.” Aemond sighed. “And even if I wanted to, I couldn’t. She’s gone back to India to see her family.”

Daeron elbowed him in the ribs, grinning like a fool. “Sure, you keep telling yourself that, Aemond.”

“Come on, don't you have anything better to do than bully me?” Aemond sighed.

“I do, but this is more fun,” Daeron said.

Aemond’s phone buzzed, as he checked the notification to see your message an involuntary smile graced his usually stoic features.

.

Meanwhile, your group chat with the girls was exploding with messages as you slept the night away in Delhi, exhausted after a day of enjoying with your old friends. You were surprised to wake up to over five hundred messages from the group chat, confused as to what could have happened. Did someone die?

Shaking that thought away, you first did your business in the bathroom and started brushing as you opened the chat. There had been so many tags to you, all of it screaming, “BITCH WHO WAS GONNA UPDATE??”

You spat out the toothpaste immediately as you saw Helaena’s text. She was very, very mad, furious.

Helaena (Sweetheart): YOU HAVE BEEN TALKING TO AEMOND AND YOU DIDN'T TELL ME! TELL ME WHY I HAD TO FIND IT FROM AEGON OF ALL PEOPLE! (cussing emoji) NEITHER OF YOU DID! Roomie<3: BITCH Y/N WHAT THE FUCK-

Helaena (Sweetheart): IFKR? YOU TELL HER, CASEY. I AM FURIOUS WITH YOU Y/N, YOU ARE NOT GETTING AWAY FROM THIS

Rinsing out the remaining toothpaste, you quickly gathered yourself and thought of the best response that you could give. Perhaps the truth would be just fine.

You: I literally bumped into him at that party and then we exchanged phone numbers and we started texting like yesterday calm down guys, I didn’t tell you because there was nothing to tell.

Helaena (Sweetheart): Aegon said that he found you, and I quote, “eye-fucking”.

You: Well, Aegon’s an idiot. I literally bumped into Aemond and I would have fallen down the stairs if he didn’t hold me.

Roomie <3: How does that lead to number exchange. AND THEN THIS?

You: then what?

Helaena (Sweetheart): sent a photo

You gasped and nearly dropped your phone as you saw the napkin with your phone number and the red lipstick stain that was most certainly yours.

You: I WAS DRUNK! AND HE DID IT THE OLD FASHIONED WAY Helaena (Sweetheart): What did he do?

You: He had written his number on a napkin and gave it to me, and my drunk self thought it was only fair to return the favour.

Roomie <3: Spill. Everything.

You: *sent a voice note*

The group chat fell silent for a long moment as they listened to you speak, and then the two of your friends started yelling at you through the messages. As you want to have your breakfast chila, you read their commentary, waiting for them to calm down enough to let this go.

Aemond Targaryen: You seem really fond of “The Love Hypothesis”, hotgirlslovetoread. Might I enquire, why?

You: Read around and find out ;P

A gasp had left your mouth as you read his text, and now you stared at your risky response to it. I shouldn’t have done this, I shouldn’t have done this. You glared at it in horror, but it was too late and he had already seen the message. Have you gone too far? Stunning him into silence? What if he thinks you are weird and stops speaking to you altogether? Gods, why am I like this?

Helaena (Sweetheart): Tell us immediately if you get any message from Aemond. I would like to know what my little brother is up to these days.

Roomie <3: You want to see if you raised him right?

Helaena (Sweetheart): Fucking hell I do. Look at him acting all grown up and not telling me that he actually met Y/N. You: Well, we’re just talking about books and stuff. Heleana, you did raise him right with the manners, I must say.

Helaena (Sweetheart): Well, I must have gone wrong somewhere with the both of you since both of you met each other and decided not to tell me.

You: I was a busy woman this past couple days, if anyone deserves these taunts it’s Aemond, not me.

.

Helaena sits in front of Aemond Daeron, carefully watching the chess game her little brothers are playing. Aemond moves his black pawn diagonally, taking Daeron's white queen. "Checkmate," He says, face stoic as ever.

"How do you always manage to win?" Daeron sighs, stretching in his chair.

"You missed important observations," He explained. "When you play, all of your mind should be on the board, trying to figure out my next move instead of yours. If you get that fine, you'll win."

"Enough of chess now," Helaena said. "I want to go out with you guys now."

"We can go in half an hour, I just need to be on a short call with Professor Leyland," Aemond says, going to his laptop desk. "Shouldn't take more than 10 minutes,"

"Would it be a problem if we stay here?" Daeron asks, looking at him with big pleading eyes.

"It's fine," He turns to his laptop, putting a finger to his lips to tell them to stay quiet.

"Good afternoon, Professor Leyland." Aemond speaks.

"Good afternoon, Mr. Targaryen." the other voice says. "You said you wanted a new topic for your research, and I was thinking of assigning you Indian history. It's a vast topic and I am hoping that you wouldn't have issues with the travel expenses."

"I am grateful that you think I am capable of covering that topic," He politely smiled, ignoring the burn of the glares being sent his way by his siblings. "Of course, expenses are not an issue."

"Good then, you will cover your project works in the subjects with the same. Feel free to choose any city for your report work." The old voice said. "That’s it Mr. Targaryen, have a good day."

"Good day, Professor." Aemond said as he hung up.

"What was that?" Helaena asked as he closed his laptop, looking at his too still hands. "This is some sorcery that you are doing."

“It’s fate!” Daeron said, clapping his hands together in his little drama queen fashion. “This is a sign from the universe, mate!”

Aemond couldn’t stop the heat that flooded his cheeks, but he cleared his throat as Helaena and Daeron shared a look. “Didn’t we have to go out?” he said instead. “You know what, we should go to the mall. I want to get… a new chain.”

“Sure,” Helaena commented, and Daeron snickered. “I will speak with Y/N,”

“Thank you,” Aemond said, straightening his straight sweater sleeve.

.

.

.

Tags:

@depressedperson88

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

16, 21, 26 ask game

thank you for the ask! these are all great questions

16. which stereotype about your country you hate the most and which one you somewhat agree with?

oooh. like @ashesandhackles said, it's very annoying when people are surprised we can speak english, lol. i've seen people being surprised at the fact that we have internet. almost every instagram reel about india will have comments about how the people all shit in the streets😂

ones i agree with? hmm the cows everywhere one is true 😂😂india also is genuinely quite dirty. it's very common for people to be casually racist 😂and we do shake our heads while talking

21. if you could send two things from your country into space, what would they be?

food and dance, i think. aliens deserve to see kathak and enjoy mutton seekh kebab

26. does your nationality get portrayed in Hollywood/American media? what do you think about the portrayal?

it does!

when i think of india in hollywood, inevitably i think of slumdog millionaire. now i fucking love that movie. and i love danny boyle (shout out to steve jobs 2015) but it does paint a certain picture of the country. which isn't...inaccurate, exactly, but it's a tiny little pixel of a massive painting. the events/setting of the movie is by no means unrealistic for a modern india but for someone like me who has only grown up in major cities in a pretty much upper middle class family, it feels like a completely different universe. all that to say, india contains multitudes and the usual poverty porn of the country you get is not at all relatable to a significant amount of the population. i think the very location of slumdog millionaire proves my point, really. dharavi is the largest slum in the world, and right across the street lives mukesh ambani, the 9th richest man in the world.

tangentially, my favourite portrayal of india in western film is wes anderson's 'the darjeeling limited'. it's not set in a major metro city but it's not poverty porn either. and i think, somehow, it really captures an essence of india! little scenes like adrien brody being amused at boys playing cricket with a tennis ball....it makes me feel so fond of my country <3

“hi, I’m not from the US” ask set

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

INDIANS OF TUMBLR hiii, I'm back with a request for some solid discourse / discussion, please :)

So it's about this whole underwear-burning nonsense that's going on. Here's what happened.

TLDR : An Indian men's rights group is protesting against the "women-centric gender-biased laws" in India, referring specifically to provisions in the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005, rape legislation, and alimony and maintenance laws. They have a range of issues, including "women being considered only as victims and men only as oppressors," the law being "skewed in women's favour in practice," women having "more rights and getting special treatment," demanding gender-neutral laws, and a separate civil body for "petty marriage disputes." They also say women take advantage of these laws by making false accusations against men in order to extract money or property. Men's rights activists around the country are supporting the NCM India Council in this move.

Now, I could tear their argument apart statement by statement - there's a lot of dum-dum in here. I can't believe they're complaining that women get free train tickets, and a separate metro compartment - for gods' sake, it's not like the women's metro compartment actually has only women in it. At least, not in my city. And as for women taking advantage of men, the proportion of such cases compared to the number of actual victims is tiny. Really, that man's statement is making me see red.

The only part that's tripping me up is the non-gender neutral nature of our laws. With the sociocultural context and long patriarchal history, it seems absurd to be inclusive of men rape victims, I guess - but ideally, the law should be inclusive, right?

I just want to understand different perspectives about this (as long as they aren't misogynistic). Are there any avenues where men's rights are truly an issue in India? Is there any other dimension to this where men are genuinely sidelined? I consider myself a feminist, and so I'd like to know if there's anything I'm missing. And asking y'all on Tumblr is more civil than arguing in Instagram and Reddit comment sections😭

Oh, and feel free to rant about this idiotic protest as well🤓

Some more articles I looked at. These also feel real petty, but I'm willing to give them the benefit of doubt :

A men's rights group in Pune staged protests

Older article about women taking advantage of men legally

Any and all respectful insight is appreciated, y'all🥺 (as long as it isn't misogynistic. Please don't be misogynistic)

#jaate jaate keh gayi#desi#desiblr#india#law#politics#gender#indian legal system#feminism#rights#men#men's rights#women#women's rights#women's movement#feminist movement#indiablr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

HONSIM ; MEMORIES

by dhalsimxhonda on tumblr

SUMMARY : while doing some housecleaning, dhalsim discovers his family pictures as his memory stirs.

SETTINGS : street fighter 6 with a flashback of street fighter alpha 3

dhalsim does his housecleaning on the village, ensuring that everything is clean before teleporting back to metro city to check on edmond honda and the children. the smile onto him and he enjoyed every moment of sweeping and taking out the dust away. it’s his favorite chore to do before getting ready for his yoga. he reached to the shelves and looked at the family photos. he stopped cleaning the bags of dust away and took a look at the picture of his husband and the children. dhalsim smiled and cleaned the picture frames carefully and his memories of the past stirred…

mumbai, india, eighteen years ago…

“and you’re my next opponent?” dhalsim turned around only to watch the sumo wrestler walking towards him. “you’re here to fight me?” the japanese man laughed. “i’m just here to show them the glory of sumo wrestling! why not i give you a slap, pretty boy?” the yoga master took a glance and placed his own hands like a prayer. “will you quit calling me that?”

edmond honda crossed his hands as he grabbed his salt. “you seem pretty handsome for a fighter. what’s your name anyways?” he asked. the yoga master sighed. “i am dhalsim. a monk. i only fight in this tournament for my village.” the sumo wrestler threw sand for purification before whipping his mouth. “how sweet… i’m the one and only edmond honda! just a sumo wrestler promoting sumo wrestling. wanna rumble in this fight, pretty monk?”

dhalsim sighed but took his turban off to begin the fight. “i accept this fight, honda. allow me to test your skills.”

“doisei!”

“namaste.”

SNAP!

dhalsim stopped and took a look at the picture again. taking aback by the memories he had with edmond honda and creating a family, he was lucky to fulfill it. the yoga master smiled and kissed edmond’s picture, placing his picture back on the shelves. all of those memories from the 90s have made dhalsim realize that he did find the perfect soulmate. with agni by his side, the yoga master knew that yoga and sumo wrestling work out perfectly.

LINKS FOR THE PROMPTS !

AO3 , WATTPAD .

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

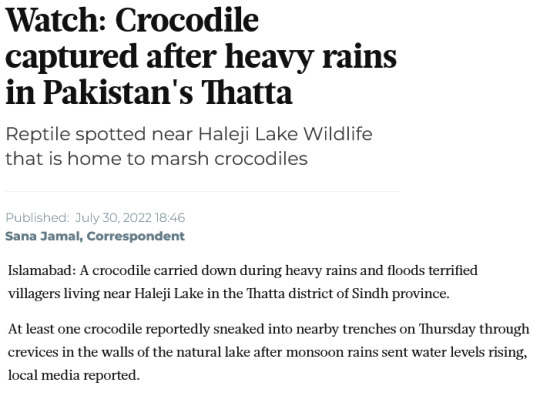

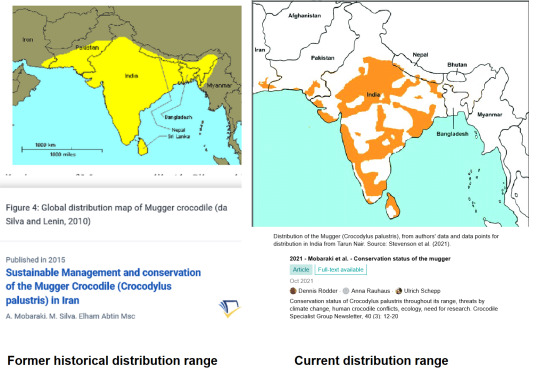

The Gando creatures -- the westernmost population of mugger crocodiles in Iran -- are a last outpost, bordering a “no-man’s land” without crocodiles stretching between southeastern Iran and the Nile crocodiles of Egypt. Muggers (Crocodylus palustris), the iconic freshwater crocodile of South Asia, are now extinct within Myanmar, Bhutan, and, likely, Bangladesh. There are about 500 muggers still surviving within Iranian borders, with a few also surviving in southern Pakistan; they are in unique peril, compared to the healthier muggers in India and Sri Lanka, given local drought conditions. Following the highly-publicized disappearance of the Zayandeh-Roud river in the metropolitan and cultural center of Isfahan, in late 2021, drought continues to endanger riparian corridors across Iran. But good news: Muggers continue to appear in drought-stricken Iranian refugia and in habitat near major metro areas near Pakistan’s Indus mouth.

From 29/30 July 2022, at Thatta, near Haleji Lake between Karachi and Islamabad:

-------

From 16 January 2022, in Iran.

Excerpt:

One would not usually associate Iran and its snow-clad mountains, arid deserts, high plateaus, lush green Hyrcanian forests and the Persian Gulf coast with crocodiles. But Sistan and Baluchestan, the country’s second-largest province by area, that borders Pakistan and Afghanistan, is home to the animals. [...] The BBC December 28, 2021 described how conflict had increased between crocodiles and humans in Sistan-Baluchestan due to extreme scarcity of water. Asghar Mobaraki, Iran’s foremost expert on crocodiles, noted in an academic article last year:

The (crocodile) population in southeastern Iran remains severely vulnerable to extreme climatic events, such as periodic droughts and floods. Iranian crocodiles are therefore directly impacted by climate change and are in critical need of immediate study to evaluate this threat. [...]

The province is home to the Baloch people, who make up the majority and overlap into the neighbouring Balochistan province of Pakistan. The province is also home to Chabahar on the Persian Gulf, where India is building a huge port. [...]

“The crocodile found in Iran is the same species that is present throughout the Indian subcontinent, the mugger crocodile or Crocodylus palustris. Regional differences are possible, depending on factors such as resource availability,” Sideleau said.

He noted:

The Iran muggers represent the westernmost population of mugger crocodiles and the westernmost population of crocodiles before you reach the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) in Africa. There is a “no man’s land” with no crocodilian species from Iran to Egypt, where Nile crocodiles are currently found in Lake Nasser, the reservoir created by the Aswan High Dam. This “no man’s land” is almost certainly due to the aridity of the region and the lack of habitat.

“Crocodiles in Sistan-Baluchestan are known by the Balochi term ‘Gando’, meaning ‘moving on a belly’,” Mobaraki told DTE.

“We estimated that there are 500 gandos in Iran currently, almost all of them in Sistan-Baluchestan,” Mobaraki said.

“An estimated 500 wild muggers remain within the southeastern part of Iran, in Sistan and Baluchestan Provinces (the Gandou Protected Area). They occupy ponds along two large rivers, namely Bahu-Kalat and Kaju, two dam reservoirs (Pishin and Zirdan), small artificial water dams, and some manmade local ponds in villages,” the article written by Mobaraki last year, noted.

He agreed with Sideleau’s view that the gandos of Iran were scientifically considered to be the same as the muggers of the Indian subcontinent. “But the Iranian populations are in an extreme habitat. Hence, they seem to be a bit polymorphically different. They are smaller than their Indian relatives,” Mobaraki said.

Iran had been in the news over climate change in November 2021, when the residents of Isfahan, the country’s third-largest city, had clashed with authorities over the ‘disappearance’ of the city’s river, the Zayandeh-Roud. [...] The Iran Meteorological Organization has estimated that some 97 per cent of the country is dealing with drought at some level, according to media reports.

-------

The preceding headling, image, caption, and text excerpt were published by: Rajat Ghai. “Yes, there are crocodiles in Iran and they are in trouble due to climate change.” DownToEarth. 16 January 2022.

The other two species of crocodilian in South Asia are the saltwater crocodile and the unique gharial. The saltwater crocodile has been eliminated throughout most of its Indian/South Asian distribution range, while the gharial has been driven to extinction in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Bhutan and now only lives in a couple of specific river systems in Nepal and the Ganges corridor of India. Though now apparently locally extinct in Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Bhutan, small populations of muggers persist in Pakistan and Iran. Former historical distribution range and current distribution range:

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“what are you listening to?”

#want my other earbud?#we could be unhinged ab atsv togetherrrr#txt#atsv#across the spider verse#spiderverse#Spotify#sir burg’s music takeover

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Across the Spider-Verse

Holy moly, what a good movie!

I loved the subversion that Hobie was initially set-up to be a romantic rival for Miles but ended up being just a really good friend to both of them

it’s also really refreshing to see anarchist values represented in a positive light

Dude looked like he was ripped straight out of a local punk zine

which brings me to the animation in general

easily the biggest leap in this style since Into The Spider-Verse, the additions here really added a lot

like the first film, there was the blending of animation styles and framerates

but this was done on a much grander scale

You had pop art, lego/stop-motion, Fleischer style worlds, the DIY aesthetic of Spider-Punk and a lot more

there was also comic-book like boxes that popped up like the ones below from the first film

this time though, they’re used more frequently, colour coded sometimes, even used to denote references to characters and events like how they usually stick in editors notes in comics -ed.

They really pushed the style of ‘pulled from the page’ even further

if this wins another animated film oscar I wouldn’t be too suprised

the soundtrack had some bops but no ‘Sunflower’

Metro Boomin did work on it though and right now I’m especially liking the credits song, ‘Am I Dreaming’

The way this film leans into the fan service, but pulls on the heartstrings is fantastic

it’s essentially about Spider-Man lore/history

it really leans into some great Spidey themes

Plus, The Spot turns out to be a fantastic choice of villain

the way he parallels Miles journey is really neat

I think it was especially important for the film to open with Gwen and her father, and how Spider-people deal with loss/family/fear of loss

Besides Hobie being the MVP (besides Miles, Gwen, and Peter B./Mayday), the other coolest Spider-folk introduced is Spider-Man India

dude is effortlessly cool

which he kind of points out =)

so many cameos

so many great gags

Spectacular Spider-Man and Insomniac Spider-Man

That ending too, woof

it’s going to be hard wait

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A man is calling home from the phone booth of a hospital. He is in the emergency room, but doesn’t want to scare his wife, so he tells her that he has a stomach problem, nothing more. The wife blames herself for not being there with him. He smiles and presses one hand against the glass partition of the booth. “Really, it’s not that bad,” he says. She asks him about the doctor. He pauses before answering. If not for the pause, you’d never suspect that something else is at stake. Now you understand that the man is lying: “Don’t worry, it’s nothing.” His hands are fumbling inside the booth for what he can’t bring himself to say.

Since Irrfan Khan died in 2020, I have returned often to this moment from The Namesake. Something about the man’s tact—part of what Khan once called the “rhythm” of every character he plays—has remained with me for months: something about those hands. Khan’s career was in many ways studded with tragic roles—a doomed lover in Maqbool, a stubborn outlaw in Paan Singh Tomar, a hands-on billionaire pursuing a dinosaur from a helicopter in Jurassic World—and yet I keep replaying the one death scene where his character doesn’t let the audience know what is about to come. The man persuades his wife that he is alright before putting back the receiver. Then he withdraws his hands into his pockets and walks away from us.

There was Khan fifteen years ago, just when his film career was starting to take off, somehow able to embody the sense of an ending. He would come to repeat the performance, this time for real, once he was diagnosed with cancer in 2018. In a span of two weeks, his calendar changed: his life, as he wrote then, quickly became “a suspense story.” He moved with his wife, Sutapa Sikdar, to London for treatment. But a year later, he was back in India, shooting a film, looking happy on set. For a while, as in that scene in The Namesake, his demeanour seemed to betray nothing untoward. After his death, Sikdar revealed that his medical reports “were like scripts which I wanted to perfect.” In his last months, while coming to terms with his illness, Khan was sparing his future biographers any qualms about pacing.

Actors’ lives do tend to mirror the imagined arcs of their movies, but Khan’s trajectory seems ultimately more redemptive than the elusive men he portrayed. To those of us who grew up in India at the turn of the millennium, Khan first proved that it was possible to be a protagonist in a popular film and not sing and dance in the rain; that a character could be brought to life as much by what they said as what they didn’t; that a scene you watched unfold swiftly on screen often involved years of contemplation and restraint. When Khan took up roles in international releases like The Namesake and A Mighty Heart, he didn’t undergo much of a makeover. He was still the outsider, born to middle-class Muslim parents in Jaipur. He seemed worlds apart from the prancing heroes of Bollywood musicals, the handful of families who maintained an incestuous grip over the studio system in Bombay, or the older generation of cosmopolitan Indian actors who spoke Edwardian English and contented themselves with supporting roles in British period films. In just over a decade, he became a presence on screens all over the world, with appearances in The Warrior, The Lunchbox, Slumdog Millionaire, Haider, Life of Pi, Jurassic World, even a sizeable part in The Inferno, where he outshone a glib Tom Hanks in scene after scene.

The first time I noticed Khan on a screen I thought he screamed like Al Pacino. Not the Pacino of Scarface or Dog Day Afternoon, braying out threats all over the place, but rather the don in The Godfather Part III: older, lonelier, the bravado all but invisible, howling skyward when his daughter dies in his arms. The scene I watched Khan in, from Life in a Metro, didn’t feature any deaths, but the moment I remember was inflected with a similar sadness—a need, paradoxically private, to exert one’s lungs out. Khan’s character, Monty, has dragged his work friend Shruti (played by Konkona Sen Sharma) out to the rooftop of their office building in Bombay. Shruti happens to be dealing with multiple disappointments in her life. Her sister’s marriage is falling apart; the last man she dated lied to her about his identity. “Who are you angry with?” Monty asks her. “Somebody in particular? Or just your luck? Whatever it is, just let it out.” At first, Shruti is reluctant—“It’s not so easy,” she tells him—but then the two of them scan the skyline for a moment and start shouting together at once. Their voices ring out in the quiet. The building is tall enough to drown out the city’s sounds and impose a simulated silence. When Shruti breaks down halfway through, you sense that she is facing up to her pain. But Monty’s yelling is tinged with the weariness of having tried a trick one too many times and still being doomed to try again.

From that moment on, you know that Monty and Shruti will fall for each other. The scene on the roof crackles with the thrill of seeing and being seen, the vulnerability usually associated with a first kiss. Later in the film, Monty asks her why she ghosted him after that first date. She replies that she’d caught him staring at her breasts once. “That?” Monty bursts out shouting. “You rejected me for just that?” Then he grins and steals a glance at her body again. Khan’s eyes carry that scene. You can’t really tell whether they seem glazed over because of the smoke from his cigarette, or because he is pretending to be upset.

I fell quickly for Khan: those pauses, those eyes. How they made you think there was more to him than he let on. As a teenager, I’d spend days watching the Godfather movies on a loop, mouthing Pacino’s lines, memorizing his gestures to try on friends. Now I modelled myself on an Indian counterpart who didn’t even need a good line to be noticed. When I moved to Bombay for college, I remember walking around the sea on my first evening and finding myself at the exact spot where they had filmed Monty confronting Shruti about her rejection of him. It felt like a meaningful sign in a city that seemed to desperately believe in portents. Everywhere you went, you could glimpse in people’s faces either a placid certainty or a fear of transformation. Inside crowded trains during office hours, unsure if the incoming rush will part for me to get down at my stop, I’d overhear lonely men consoling one another with their plans of getting married and rich. Couples lined the promenades and beaches late at night, their backs turned to the bright lights on land, as if their time together made more sense in the dark. Each time you passed by the studio lots, rows of would-be actors sized you up around the gates, in case you were a casting agent looking to give someone new a break.

I, too, had come looking for a break. But what was it that I wanted to do? One week I’d design a billboard campaign for an ice cream brand, aspiring to end up in an ad agency. The next week I was a documentary filmmaker, getting arrested while shooting undercover in a temple. I longed for the exhaustion of experience: perhaps a job where, at the end of the day, someone might invite me to the rooftop of the office building and let me yell my feelings out. Khan’s antics exuded depth, an air of having seen and lived through so much—precisely the image a college student, hungry for life, yearns to project.

Once, I asked a woman to meet me early in the morning near the waterfront. The idea was to find a quiet place and, I remember texting this, shout “our inner demons out.” It must have been a confusing message and yet she showed up more or less on time. We sat on two chairs overlooking the beach and risked stern glances from morning joggers to awkwardly launch our voices across the sea. The sun was already blazing on our backs and soon we gave up trying to impress one another. We started going out not long after, but never spoke of that day again.

Irrfan Khan was born Sahabzade Irfan Ali Khan at a time, long ago now, when Indian Muslims were perceived as Indian above all. His father was a lapsed aristocrat who had given up his family land and privileges but still liked to go on frequent hunting trips. His mother was more introverted and usually at home. Little Irfan, the second of four children and the first boy, would have liked nothing more than to be affirmed by her. “I desired to be close to her,” Khan once said in an interview, “but somehow we’d end up fighting with each other. I used to imagine her patting my head in approval—I think I’ve been looking for that feeling all my life.”

His mother imagined that her children would settle not far from her in Jaipur, taking up modest jobs that just about paid the bills. Years ago, her brother had travelled to Bombay, looking for work, and never returned. Her husband’s early death only added to her fear of abandonment. Irrfan was nineteen then, and as the oldest son, expected to look after his father’s tire shop. But his hopes had been stirred up watching leading men in Hindi matinees: a grandiose Dilip Kumar in Naya Daur, a raffish Mithun Chakraborty in Mrigayaa. Someone told Khan that he looked like Chakraborty: tall, dark, un-photogenic. He began to style his hair like the hero. After high school, he joined evening theatre classes in a local college and even witnessed a couple of Bollywood shoots in town. He wrote to the National School of Drama in New Delhi, bluffing in his application about plays he hadn’t acted in. They offered him a scholarship and Irrfan moved out of the house.

In Delhi, Khan nearly got his big break. The director Mira Nair had come to campus looking for actors to cast in her debut film, Salaam Bombay. One day, she noticed Khan in a classroom. “He wasn’t striving,” Nair later recalled watching him act. “His striving was invisible. He was in it.” She cast him in the main role and Khan went to Bombay in the middle of the semester to train with the crew. But after two months of rehearsals, Nair decided that Khan didn’t look the part. In the final film, Khan appears for a grand total of two minutes, as a letter writer who dupes the child protagonist. In life, however, it was Khan who might have felt deceived: he had travelled all the way to a new city, thinking he had bagged the role, only to end up on the train back to Delhi before the shoot. His first role, as he would say later, also “became my first setback.”

Nair took another twenty years to cast him again in The Namesake. That Khan would rough it out for so long should not come as a surprise, for actors remain dispensable in Bollywood, unless they become box office gold or belong to insider families. Squint at the backdrop of a scene in any Hindi film and you will spot a good actor—good, in spite of their measly roles. “Talent is insignificant,” James Baldwin once wrote. “I know a lot of talented ruins.” Thirty years ago in Bombay, around the production offices in the western precincts, you were likely to find just as many untalented plinths. There was the shirtless scion of a famous scriptwriter who showed off his abs in every other scene (and keeps doing so these days opposite women thirty years younger than him). There was the son of a powerful producer who became the country’s most bankable director by having his romantic leads tussle it out on a basketball court—then a rarity in India—and heralded the industry’s turn away from rural audiences to richer, albeit equally conservative, Indian expatriates. Then there was the middle-aged director who liked to appear in medias res in all his movies. He would pop up halfway through a song or a scene, staring at the camera from under a sun hat, just so you didn’t forget you were watching his film.

Khan tried his best to find an opening in this milieu. He was told, for instance, that the showman director in a sun hat had seen Khan act somewhere and was apparently considering him for a part. He spent the next few months waiting in vain for the director to call. Casting agents would glance at his portfolio and chide him for taking on diverse roles. He was told not to fiddle with his looks and angle for essentially the same character in every film. He survived those years doing television gigs, daytime soap operas where the action happened once in real time and then again—twice—in slo-mo, so that viewers could follow what was going on with their eyes closed. What was an actor’s actor doing in that world? Producers would tell Khan off on those sets for pausing between his lines. Cinematographers wanted him to look at the camera while talking.

He met Sikdar, a screenwriter, in drama school, and by the end of the millennium, they were married and had a son. Sikdar even brought him aboard a couple of shows where she was employed as a writer, but Khan didn’t land a leading role throughout the ’90s. One time he was so desperate for work that when someone pointed to a TV tower on a hill and joked that Khan might get a job there, he actually trekked up the mountain.

I know that tower on a hill: it was the landscape of my childhood. My mother worked as an engineer for India’s public broadcaster. Every few years she’d be transferred to a different TV station across the country, which meant that we had to move from one housing campus near a TV tower to another. At the same time Khan was struggling to find his bearings in soap operas, my mother was helping beam those episodes into homes week after week. Later, when he talked about these shows in interviews, I’d recognize their names, but have no memory of their protagonists or storylines, never mind any flashback of Khan stumbling through a scene. What I do remember is the tedium, the eternal blandness of those afternoons and evenings when a cricket game spread over five days would seem like the least onerous thing to watch. Cable channels had arrived some years ago with the opening up of the economy, but their content was still lacklustre: turgid comedies, lachrymose adaptations of Hindu myths, stale reruns of Santa Barbara and The Bold and the Beautiful. On weekdays, kids had just an hour of Disney cartoons—mostly DuckTales and TaleSpin—while on Saturdays, they could skip school to catch up with a preachy local superhero moonlighting as a buffoon in glasses.

Looking back on his lost decades, Khan felt that his biggest challenge was remaining interested in his craft: “I had to come up with ways to keep my inspiration going.” The first time he got paid for a role after moving to Bombay, he bought a VHS player, apparently to avoid getting “bored of my own profession.” The Indian viewer in those days was just as bored. I remember making do with little: listening to songs from forthcoming films, then watching the video sequences of the same songs on TV, so that by the time we caught the movie in a theatre, we’d get our money’s worth whistling and crooning when the songs came on.

The world opened up, at least for my generation, with the prevalence of CD and DVD burner drives on computers that freed us from the tyranny of television and the next Friday release. By the time I was eleven, I was hanging out at a friend’s house every afternoon just to copy out discs from his older brother’s collection of MP3s. Vendors on the street would sell bootlegged prints of everything from Rashomon to Home Alone to Deep Throat, and soon enough, grainy camera recordings of the newest movie in theatres, for the exact price of a balcony seat.

I remember watching a pirated print of The Warrior, the film Khan credits with reviving his career. The scenes were gorgeously rendered: Khan, long-haired and lanky, brandishing a sword in a forlorn expanse of sun and sand. Then later, with his hair cut, looking both lost and determined as he treks his way through cascading woods in the Himalayan hills. Khan didn’t need to puff up his arms or chest to play the part of an enforcer to a medieval warlord. His eyes gleam with menace when he goes plundering across villages on horseback, and afterwards with trauma, when he is forced to watch his little son being executed in an open field. Silences suffice in this world of mythical beauty and carnage. Feelings are conveyed with the slightest of frowns and hand movements; everyone speaks in hushed tones despite the bloodshed.

When the director Asif Kapadia—who later made the Oscar-winning documentary Amy on the singer Amy Winehouse—first auditioned Khan, he thought he looked like “someone who’s killed a lot of people, but feels really bad about it.” Kapadia had discerned something essential about Khan’s appearance in any movie: the story of a film often played out on his face.

The Warrior was never released in Indian theatres. (US rights were bought by Miramax, where it became another film that Harvey Weinstein shelved for years.) But a couple of new directors noted Khan’s ability to evoke menace and cast him in two films that gave him a footing in Bombay: Haasil and Maqbool. His characters in both films have killed a lot of people, but it is in Maqbool, where he plays the lead again, that you get to see how he feels about it. There is a moment when Maqbool is staring at the corpse of his best friend, having himself ordered the hit, and he imagines that the dead man has opened his eyes again. Maqbool falls tumbling backward in shock. Apparently on set, Khan was so persuasive while doing the scene that his co-actor Naseeruddin Shah thought he had really lost his balance and held out his arms to support him. Shah had been one of Khan’s idols in drama school, and there he was, taken in by the latter’s performance. “You’re bloody good,” he told Khan.

By the time I saw a pirated print of The Warrior, Khan had impressed many others with his breakout roles. He stood out in The Namesake as the withdrawn father. Wes Anderson wrote a part in The Darjeeling Limited just for him. He was cast as a cop in both A Mighty Heart and Slumdog Millionaire. In India, Life in a Metro showed that Khan need not always play the brooding murderer. He even appeared in a TV ad that became very popular because of its setup: sixty seconds of Khan just impishly chatting up the viewer from a screen.

Those were indulgent days. Bollywood was finally catering to the country’s craving for realism. Filmmakers could hope to break even by releasing a movie only to select audiences in cities, which meant that they could steer clear of big studios and song-and-dance routines, and instead cast new actors as leads.

In Bombay, a decade ago, I often had the sensation that we were making up for lost time: all those hours squandered in childhood when we were deprived of things to watch. I lived at the YMCA with a roommate who was glued to his laptop all day and night, watching something or the other. D. had a couple of 500 GB hard drives, stacked with torrent downloads of the latest Japanese anime series, episodes of every American TV show aired in the last thirty years, and an unbelievable archive of international movies grouped in alphabetical order by their directors’ last names. He would be at his desk early mornings, sipping tea, his eyes blazing red from the memory of the show or movies he had stayed up all night to watch. On weekends he’d head out to a friend’s place in the suburbs, to replenish his stock of content. The diligence with which he’d finish a series in the span of a day, or go looking for a director’s deep cut: I never thought of him as a passive binger. To D., watching was work.

Khan, too, was putting in the work. In Bollywood, this often involved playing to the gallery, for as he once admitted in an interview, “You don’t need nuance here as an actor. Attitude is enough.” He disliked repeating himself. If he was asked to do eight takes for a scene, he’d do them in eight different ways, letting the director figure out the rest. Even with subtler roles, Khan didn’t believe that an actor could always become the character and trusted his imagination more than research. Before playing an Indian-American man in The Namesake, for instance, Khan had never travelled to the US. He understood that getting the clothes and the accent right could go only so far in conveying the inward rift of an immigrant. He fell back on his memory, recalling a previous trip to Canada where he had noticed some dour-looking immigrant workers in shops. “Something stayed in my mind,” he told TIME magazine in 2010. “A strange sadness…A rhythm that middle-aged people have.” In The Warrior, he didn’t quite believe the scene where his character watches his son being killed. He approached the moment by telling himself that the experience of shooting a film was like life, and “sometimes you have to live a life because you have no choice.” My favourite Khan anecdote is from the set of 7 Khoon Maaf, where he was cast as the third of the seven husbands of the protagonist Susanna, played by Priyanka Chopra. Khan couldn’t relate to his role: a “wife beater” Urdu poet. The poet was just supposed to be persistent with his abuse, so that the audience could empathize with Susanna when she killed him. While getting ready for his scenes, Khan happened to be listening to a random ghazal by the singer Abida Parveen. “All of a sudden,” he told Kapadia later, “that ghazal created a whole world around me.” The song helped him delve into the inner life of the poet, find a pattern to his behaviour. He was able to transform himself within moments.

On talk shows, Khan would often recount the story of inviting his mother to the premiere of The Namesake in Bombay. After the screening, she apparently asked Khan to introduce her to the director, Mira Nair. “Let me talk to her,” his mother told him. “I want to ask her why, of all the people in the world, she had my son killed off in the film?” His mother was joking, of course, but something about the recurring deaths of his characters can seem, at first glance, manipulative. The scripts that came his way seemed to repeatedly indulge the fantasy of his eventual disappearance. But death is also the script everyone wants to perfect: it is the endpoint of “striving”—the word Nair used to contrast the experience of watching Khan act in drama school—and if you dig deep into many of Khan’s roles, you’ll find a striver, a man relentlessly searching for something. Whether he is projecting nonchalance (Maqbool), pain (The Warrior), or disdain (Slumdog Millionaire), signs of hustling are always evident. In Life in a Metro, Monty is even striving to find a wife. Towards the end of the film, Monty encourages Shruti to move on from her bad relationships and try dating someone new. “Take your chance, baby,” he tells her. You almost feel that it is Khan talking, counselling the viewer to keep looking for all there is to find.

What was Khan really striving toward? He seldom gave any straight answers. In public he offered zen disquisitions about the mystery of life. Hours after his death, a scene from Life of Pi, in which he delivers a heartfelt monologue about “letting go,” went viral. He went back and forth on his name, adding an extra r to “Irfan,” dropping the “Khan” because “I should be known for what I do, not for my background or caste or religion.” In Bombay, he refused the trappings of a star despite his American fame. He lived on Madh Island, a ferry ride away from the studio lots and the inland neighbourhoods where celebrities usually splurged on landmark mansions and apartments. The distance was partly self-imposed: he never got over his disdain for messianic Bollywood heroes. For all his cameo parts in franchise movies abroad, Khan first tasted blockbuster success in India with Hindi Medium, which was released just three years before his death. He didn’t seem to mind being typecast in big Hollywood projects, turning up invariably as the “international man.” But he turned down roles in The Martian and Interstellar when their production dates clashed with smaller projects. And there was that unforgettable photograph of him looking sullen when Slumdog Millionaire won Best Picture at the Oscars, while the rest of the crew are smiling and exulting around him.

Both In Treatment and The Lunchbox make good use of this enigma: the way Khan couldn’t help but look slightly disaffected everywhere. “He’s got the loneliest face I’ve ever seen,” Paul, a therapist played by Gabriel Byrne, says of Khan’s character, Sunil, in one episode of In Treatment. And indeed, Sunil is alone, even though he lives in Brooklyn with Arun and Julia, his son and daughter-in-law, six months after his wife passed away in Calcutta. Every few episodes, Sunil sits in Paul’s office and grudgingly reveals his woes—how his wife had in her last moments made sure that Sunil would move in with their son overseas, how he can’t stand the fact that Julia gives him a weekly allowance and monitors his time with the grandkids, how she goes around calling his son Aaron, how he is absolutely certain that she is having an affair. There is something bleak about Sunil’s obsession with Julia: his eyes visibly light up when he describes the way she talks, the visions he has of “smothering” her when he hears her laugh. The showrunners keep circling back to the creepiness of Sunil’s fixation, but they miss the fact that this revulsion gives him a reason to wake up every morning in a new country. Just for a while, he can forget that his wife of thirty years has died. The deeper rift is between Sunil and Arun; Julia is just a proxy for the repressed feelings. The son has travelled too far, too soon, and the father can’t keep up.

The distance between Sunil and Arun is precisely the one Khan covered in his lifetime: from Jaipur to Jurassic Park; from the rooftop of an office building in Bombay to a therapist’s couch in New York; from playing a melancholy gangster in Maqbool to swishing in and out of boardrooms as Simon Masrani in Jurassic World. Together his roles encompass the story of South Asian globalization in the last three decades: these are men whose lives look nothing like their fathers’. For all their striving and ambition, their private lives are stunted. They don’t quite know how to be well-rounded in a rapidly changing world. The journalist Aseem Chhabra writes in his book, Irrfan Khan: The Man, The Dreamer, The Star that Khan was squeamish about doing sex scenes. Perhaps this is why so many of his characters are literally learning to love. In Paan Singh Tomar, he has to teach his wife how to kiss. In Road to Ladakh, where he plays a fugitive on the run, a lover must demonstrate the correct way to lock lips. “I don’t suppose you watch too many movies,” she teases him in bed. “We watch movies to learn these things.”

In The Lunchbox, Saajan Fernandes neither cooks nor watches movies. He is a widower, with no children, no friends. He plans to retire from his job soon and move out of Bombay. Years ago, when his wife was alive, she used to record her favourite TV sitcoms on tapes, so that she could return to them on weekends and laugh at the same jokes again. Now he stays up at night watching those old tapes, smoking on his porch, counting the hours until morning when he can go back to work. (Saajan is what Monty in Life in a Metro might have become if he had never met Shruti. Sunil, from In Treatment, can also look forward to a similar existence once he is deported back to India.) After a lunch delivery service misplaces their orders, Saajan starts exchanging letters with a youngish housewife, Ila. He tells her about his past, how he keeps forgetting things because he has “no one to tell them to”; she shares her darkest impulses of sometimes wanting to jump from her apartment window upstairs. They decide to meet and run away together to Bhutan. They arrive at the same café for their first date, and he sees her waiting alone at a table. But he can’t bring himself to walk up to her and reveal his face. He sits at another table and watches her scanning the door for his arrival. He fears that he is too old for romance.

Saajan may have missed his chance with Ila, but Khan’s performance in the movie was universally acclaimed. The Lunchbox won an important award at Cannes. Sony Pictures Classics picked it up for distribution in the US where it did good business during Oscar week. The reviews in the American press were all so gushing that I couldn’t help but slightly wonder about the applause. Why were people in New York and Los Angeles connecting so much to this portrait of a loneliness I associated with Bombay? After all, not too long ago, Slumdog Millionaire, a lacklustre musical even by Bollywood’s standards, had been championed at the Academy Awards. But my doubts mostly stemmed from an immigrant’s anxiety about their new home, for by then I was a graduate student in the Midwest. From the moment I first landed at O’Hare Airport, I was conscious of being mistaken for someone else, someone who fitted a perceived notion of being Indian. “Creative writing, really?” The immigration officer who stamped my passport did a double take while scanning my I-20 form, no doubt more accustomed to incoming Indian students enrolled in engineering and life sciences courses. My landlord in Iowa City picked me up from the nearby airport and seemed surprised that I spoke “good English.”

It was in Iowa City that I first saw The Lunchbox, in a narrow one-room theatre at the Ped Mall. Richard Linklater’s Boyhood had been screened earlier in the afternoon, and a section of the audience, which included an author who was among the faculty at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, had stayed back to catch the evening show of an Indian film. After the screening, the author and his wife waved me over to their seats. We fell into the usual post-show chatter about the film. “Watching it I felt so hungry, you know,” the author said, “The food! The spices!” He turned to his wife. “Honey, do you mind eating out tonight?”

Where I had glimpsed something ineffable—two lonely people in a city—he had spotted something expedient: his dinner plans. And indeed, later that night, when I passed by the only South Asian restaurant downtown, he was seated at a table by the window, stuffing his face with a naan. When I watched the movie again, I realized there were barely any close-up shots of the spices or the food: mostly you saw Ila filling up the containers of the lunchbox in the mornings and Saajan licking his fingers clean at lunch. I guess, for the author, the spices were a part of what was clearly an Indian night.

“You look like the guy from Life of Pi.” I heard this often enough in Iowa City to know that it wasn’t just an old white man thing. Baby-faced theatre majors part-timing as baristas in cafés, international writers staying over on a residency during the fall: they’d all recall the last time they had seen an Indian on screen, moments after meeting me, and offer what they no doubt thought was a compliment. The child in me wished that they were talking about Khan, though they probably meant I reminded them of Suraj Sharma, who plays the half-naked kid stranded in the middle of the ocean for much of the film. I looked nothing like Sharma, but did feel some affinity for Pi during the shipwreck. Before boarding, the boy had watched his father’s zoo being loaded on the docks, all those animals that they hoped to carry over into their new lives.

I missed Bombay, and worried about forgetting the place during my time away. In the stories I wrote during those years, I was recreating the city in my head, street by street. To workshop those stories in the Midwest was to receive an education in distance: I grew aware of the difficulty of things travelling through intact, the quixotic task of carrying over one’s past. There was the time twelve graduate students sparred in a room for over two hours on whether my characters should be talking to one another in Hindi. Or the afternoon I lost my patience when someone suggested that a story by another writer about an Indian family in Alaska could be improved if the children ate more curry. Each morning I might return on the page to the roads and promenades I had moved through for years, but the American reader would be stuck wondering—this was a verbatim comment I received on one of my stories—if “the city of Mumbai allowed double parking.” I thought of Khan buying a VHS player decades ago, to keep up with actors abroad, or my friend D. staying up all night and watching movies in Bombay, to keep up with the world. We might spend our lives back home bridging the gap with the West. But not many here were keeping up with us.

The years just prior to Khan’s cancer diagnosis were his busiest. According to Chhabra, Khan acted in sixteen projects between 2015 and 2018. He turned producer with Madaari, a jingoistic thriller where he positioned himself as a man taking on a nexus between politicians and businessmen. In Haider, an adaptation of Hamlet set in Kashmir, he embodied the part of the ghost, apprising the protagonist of his uncle’s betrayal. Judging from his roles in films like Piku, Hindi Medium and Angrezi Medium, he was branching out in this period as a comic hero. The loneliness was again evident: his droll characters don’t come across as clowns so much as men cracking jokes to fill up an awkward silence.

Awkward silences were becoming a norm in Bollywood as India was succumbing to Hindu nationalism under a new leader. The country’s biggest actors and directors held their peace when more and more films began to be censored after Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014; they refrained from commenting when mobs of armed policemen stormed university campuses, when Muslims were stripped of their citizenship and lynched on streets; they chose to appear in group selfies with Modi and call him a “saint,” even as multiple dissenting activists ended up in prison without a trial or, worse, dead. They didn’t even speak up when a young male actor died of suicide in 2020, and his girlfriend, also an actor, found herself being vilified night after night on partisan TV news channels. One woman took the fall in a media trial fueled by wild insinuations and blinkered opinions. She was blamed for swindling her boyfriend’s finances and accused of practicing “black magic.” In the end she was arrested, allegedly for buying him marijuana, weeks before a crucial election in the deceased actor’s home state.