#medical anthropology

Text

Losing my mind over paintings of historical medicine again. This is "The Doctor" by Luke Fildes.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

"...the idea that addicts are the kind of people who cannot read and render their inner states generates a rehabilitative program of reproducing, protecting, and patrolling highly valued but rarely questioned linguistic norms. Conversely, the cultural privileging of the presupposing, denotational function of language not

only lays the foundation for the clinical construction of the addict; it also and by extension establishes what it means to speak like—and therefore be—a healthy, clean, and sober person. It follows that chemical dependency therapists strive to fulfill a cultural as well as professional charge when they work to produce sober people by distilling sober ways of speaking."

- Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety, Summerson Carr

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

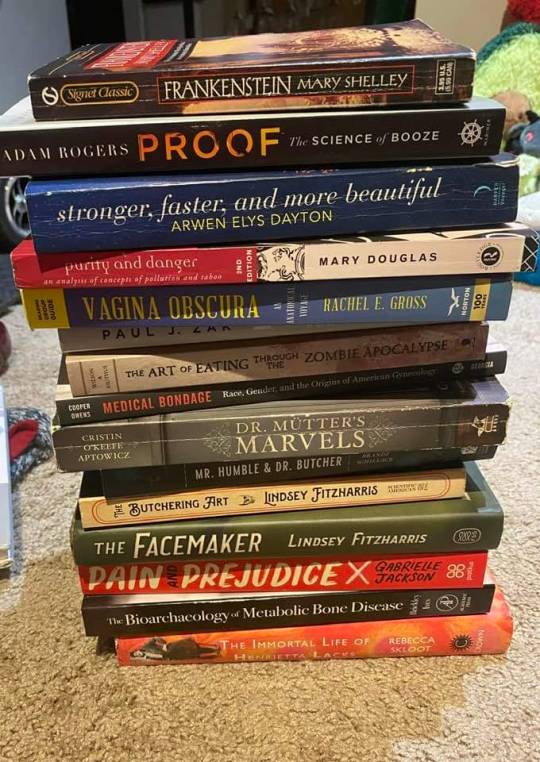

With Dr. Rebecca Gibson's upcoming book #TheBadCorset, the reading list for her Medical Anthropology course in case any of you are interested.

Pre-order The Bad Corset here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruin Their Crops on the Ground review

5/5 stars

Recommended if you like: nonfiction, medical anthropology, social justice, food studies

Big thanks to Netgalley, Metropolitan Books, and the author for an ARC in exchange for an honest review!

Wow. I cannot sing the praises of this book enough. It goes in-depth into the way food and food policy has been, and continues to be, weaponized as a means of control. I got my BA in anthropology and got very into medical anthropology when doing that, so I knew a little about the stuff Freeman talked about, but she goes into detail and provides a lot of context for these topics and clearly elucidates the historical-to-contemporary connections. I learned a lot of new information from this book and found that it was presented in a very understandable manner. This is definitely one of those books that I think everyone should read.

The book is broken up into seven chapters and an introduction, the first three chapters each focus on an ethnic and cultural group in the US: Native American, Black, and Hispanic. In each of these chapters, Freeman looks at the traditional foods eaten by those groups and the benefits those foods provide nutritionally. She then examines how colonialization altered those foods and forced people in these groups to start eating according to how white people wanted them to, often switching from highly nutritious foods to foods of subpar quality and foods with empty calories (i.e., bison to canned meat, hand-made corn tortillas to white bread, etc.). From there she discusses the impacts, historically and modern-day, of those changes and the actions some people are taking to return to traditional foods.

I already knew some of the stuff covered in these chapters, but it was absolutely horrifying to learn more of the details and I found them to be very informative. It feels weird to say I liked these chapters because so much of the information contained in them is horrifying, but it's something I haven't seen touched on in too much depth in my studies and I want to learn about it. It's these chapters in particular that I feel people should read because they're so informative and provide a lot of historical and contemporary context, and I think it really showcases how things are connected through time.

The next two chapters of the book focus on specific aspects of American food and food policy. Chapter 4 looks at milk and the USDA's ties into the dairy industry. A majority of people in the world are lactose intolerant (including me, lol), though population to population the percentage changes, with Caucasians having some of the highest percentages of lactose persistence into adulthood. Not only did Freeman use this chapter to discuss the inadequacy and capitalistic-driven motivations of the USDA's milk requirements, but she also uses it to dive into the health issues associate with dairy products, as well as the racist rhetoric surrounding milk in the past and present. Chapter 5 looks at school lunches and again targets the USDA's Big Agriculture ties for why school lunches lack nutrition. Freeman also uses this chapter to touch on school lunch debt and the myriad of ways policies surrounding lunch debt serve to humiliate and starve children.

I found these two chapters to be interesting and informative in a different way than the preceding chapters. Like with the first three, I did already know a lot of what Chapter 4 covered before going into it. Milk, lactose intolerance/persistence, and the USDA were things we discussed in my medical anthro class, but the historical ties and legal efforts to change (or not change) things were new to me. I also didn't know a lot of the negative health side-effects Freeman discussed in the milk chapter and it was definitely eye-opening. Chapter 5 was interesting to me because I rarely ate school lunch as a kid, and then as a late-middle schooler and in high school I did school online so I wasn't exposed to a lot of the stuff Freeman discussed in the chapter. I definitely remember the school lunches though and how they often lacked veggies and seemed always to contain a milk carton. It was super interesting to read the politics behind what goes into school lunches and how laws to change them or keep them the same were often tied into monetary interests.

Chapter 6 talks about racist food marketing and turns somewhat away from food itself and focuses on how branding utilizes some of the things discussed in chapters 1-3 to brand food, advertise to certain groups, or both. It was definitely disgusting to hear about the racist marketing techniques and how long it took companies to actually start doing better. Chapter 7 looks into the laws surrounding food policy, and SNAP in particular, which is an area I don't know too much about. I found the discussion to be very interesting and am definitely interested in seeing how this area of law and policy develops over time, hopefully in a positive way.

Overall I found this book to be very impactful and informative. I've already recommended it to 3 or 4 people and definitely think this is an area of study more people should know about. I'll probably check out Skimmed by this author as well.

#book#book review#books#book recommendations#bookstagram#bookblr#booklr#bookaholic#bookish#ruin their crops on the ground#social justice#food anthropology#anthropology of food#nonfiction#nonfiction books#medical anthropology#netgalley reads#netgalley#books everyone should read#food policy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women in the United Kingdom are being told by healthcare professionals they cannot receive an internal examination because they aren’t sexually active, going against the advice of British medical ultrasound guidelines.

VICE World News has spoken to five women from around the UK who have been denied a transvaginal ultrasound over the past two years because they had been asked – by male and female medical staff – whether they were sexually active or “virgins.”

The exam, which uses a probe that goes two to three inches into the vaginal canal, is a type of pelvic ultrasound that helps doctors examine female reproductive organs to find the cause for conditions such as pelvic pain, unexplained bleeding or cysts.

A 30-year-old woman who was told she couldn’t receive the test because she was a “virgin” at Croydon University Hospital last week, and whose identity is being protected for privacy reasons, told VICE World News, “It’s 2022, for crying out loud. Women have to lie just to get their health checked, because apparently our well-being revolves around men. This is what purity culture has done to us.”

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unveiling the Health Impacts of Climate Change: Insights from Medical Anthropology

Climate change poses significant challenges to human health, affecting communities worldwide. In this blog post, we explore the impact of climate change on health through the lens of medical anthropology, drawing insights from the book "Understanding and Applying Medical Anthropology" edited by Brown and Closser (2016). This interdisciplinary field provides valuable perspectives on the complex interactions between climate change, culture, and health. Let's delve into some key points from the book, showcasing the interplay of climate change and health outcomes:

1. Climate Change and Environmental Vulnerabilities:

Medical anthropology highlights how climate change exacerbates existing environmental vulnerabilities, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. The book emphasizes that vulnerable populations, such as indigenous peoples and those living in poverty, often face heightened health risks due to environmental degradation and climate-related disasters. For example, rising temperatures and extreme weather events can disrupt access to clean water, leading to waterborne diseases and malnutrition, particularly in impoverished regions.

2. Cultural Perceptions and Adaptation:

Understanding cultural perceptions and beliefs is crucial in addressing the health impacts of climate change. Medical anthropology emphasizes the importance of recognizing diverse cultural perspectives and knowledge systems when designing interventions and policies. For instance, indigenous communities possess valuable traditional ecological knowledge that can inform climate change adaptation strategies. By incorporating indigenous wisdom into decision-making processes, it becomes possible to foster resilient and culturally appropriate responses to climate-related health challenges.

3. Mental Health and Climate-Induced Displacement:

Climate change-induced displacement and migration have profound effects on mental health and well-being. The book highlights how environmental disruptions, such as loss of livelihoods or forced relocation, contribute to psychological distress and trauma. Displaced populations may experience anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder as they grapple with the loss of familiar environments, social support networks, and cultural identity. Examining these mental health impacts helps guide interventions that support psychological resilience and community healing.

4. Infectious Diseases and Ecological Transformations:

Climate change influences the distribution and transmission of infectious diseases, presenting complex challenges for public health. Medical anthropology recognizes the interconnections between ecological transformations and disease dynamics. For example, changing temperatures and precipitation patterns can alter vector habitats and increase the spread of vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever. Understanding these ecological complexities is vital for developing effective prevention and control strategies.

--

Medical anthropology offers valuable insights into the health impacts of climate change by examining the interplay between culture, environment, and health outcomes. From recognizing environmental vulnerabilities to understanding cultural perceptions and adapting interventions, this interdisciplinary field sheds light on the complexities of climate change and its implications for human well-being. By integrating diverse perspectives, including those of marginalized communities and indigenous knowledge systems, it becomes possible to design contextually relevant strategies for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Moreover, addressing the mental health consequences of climate-induced displacement and considering the ecological transformations that shape disease dynamics are crucial for comprehensive public health responses. Ultimately, by drawing on the principles and knowledge offered by medical anthropology, we can forge a path toward climate-resilient health systems, equitable interventions, and sustainable solutions that prioritize both human well-being and the health of our planet.

References!

Brown, P.J., & Closser, S. (Eds.). (2016). Understanding and Applying Medical Anthropology (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315416175. -> (Highly recommend this read, even if its just a few chapters!)

#medical anthropology#anthropology#global health#medicine#climate change#global warming#healthcare#health#health outcomes#environmental impact#environment#future health

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

House MD but there's a clinic critical medical anthropologist in the same room as him the entire show arguing with him about what should or shouldn't happen and they hate each other with tounge

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ethnobotanical Plants are loved for their healing qualities and worth in both conventional and modern therapeutic areas. In man’s eternal, and never-ending travel towards Health and Wellness, he mostly tends to miss the easiest solutions that nature offers him. . As societies continue to develop towards being more organic and nature-oriented for remedies today, the essence of the plants in our lives through ethnobotany is now more pronounced than ever. Welcome to explore the nature of pharmacy. This website is intended not only to display the power of transformational plants but also to guide on how health can be introduced into the circle of living in harmony with nature.

#traditional medicine#ethnomedicine#ayurveda#indigenous knowledge#medical anthropology#global health#cross-cultural healthcare#alternative medicine#indigenous healing#traditional Chinese medicine

1 note

·

View note

Text

Meagan Luong (she/her) - UCI '23

Career Goal: Physician Assistant

Major/Minor: Public Health Sciences Major/Medical Anthropology Minor

Introduction: Hi yall my name is Meagan! I am a recent graduate of UCI and I am currently the Co-Projects Development Director as well as the Lestonnac Free Clinic Volunteer Coordinator on BOD! This will be my first time being a mentor in the Alumni Mentorship Program and I am really excited to have mentees!! Other than MEMO, I love to dance in my free time, I have always been a part of some dance team my whole life so its a very big part of me! I also love watching movies whether thats at home or in a theater. If im not dancing or watching a movie I am probably out at a cafe or boba shop hahah (i love matcha)!!! And lastly I dabble in listening to kpop (seventeen, newjeans, nct)

Involvements: MEMO, Lestonnac Free Clinic, UCI Medical Patient Care Experience Intern, Medical Assistant

Extracurriculars: Dancing, Digital Art, Art Museums

What kind of advice would you be giving? How to get involved with MEMO, finding a job, public health practicum internship

Best piece of advice you've received? That everything happens for a reason, whether it is good or bad, it is meant to teach you something to help you grow down the line!

Preferred method(s) of communication: Phone Number (text/call), Email, Facebook Messenger, Instagram

#uci#public health#physician assistant#lestonnacfreeclinic#medical assistant#medical anthropology#anthropology

0 notes

Text

So do I know any anthropologists in here who attend university if Amsterdam?

I really want to get a better feel for the school for when I begin my PHD applications in Medical Anthropology

0 notes

Link

#anthropology#biological#biology#biological anthropology#physical anthropology#medical#medical anthropology#blog post#blog#blogger#blogging#blogging community#blog website

0 notes

Text

https://www.ted.com/talks/abraham_verghese_a_doctor_s_touch

Oh my god, TED talk about the importance of physical touch and conversation in medicine! About how we still have to rely on those things no matter how advanced our technology gets, because they tell us things the technology can't. This guy talks about medical examination as a RITUAL!

@sigynpenniman I think you've been saying some of these things for a long time with Julian.

Also, I cannot tell you what a weird experience it is to have to pause my online, asynchronous class and go screech at tumblr about it because I'm so excited by it. I am currently liveblogging my homework. Why aren't all classes this fun?

#medical anthropology#medical symbolism#hylian rambles#hi sigyn look i brought you a thing#i told you i was going to become insane as soon as this class started

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

i feel like "psychosomatic illness" is a concept that only makes sense if you are subscribing to the idea that there are "real" (biomedically measurable + locatable) concerns and "psychosomatic" (often used as a fancy way of saying hysterical or "fake") concerns. except that's a false dichotomy and ALL experiences are both real AND culturally, emotionally, and experientially mediated.

example: ppl w/ congestive heart failure often experience a sudden sense that they can't take a breath. i saw this happen firsthand a LOT when working with the elderly. the experience was almost never immediately life threatening, but it FELT to them as if they were suffocating to death. this, in turn, often triggered serious panic (i mean, who wouldn't?) which then exacerbated their sensation of suffocating to death.

multiple times, i would see a nurse come and administer something to bring o2 levels up to the standard range, but the sense of suffocation would remain. the nurse would then shrug, tell the patient to calm down because they weren't actually suffocating, and maybe toss them an ativan. keep in mind- while their o2 levels could eventually result in death if left unmanaged (could cause long term organ damage, syncope, low bp, etc), they were never in danger of immediately dropping dead- but they FELT as if they were- the perceived and actual risk of immediate death remained relatively consistent throughout the episode

yet at some point, they became biomedically "safe"- their o2 was now back to normal and thus a shift occurred from "urgent, meaningful concern" to "all in your head, not our problem". internally, they are still experiencing this terrifying sense of suffocation, but the "healing" has supposedly already been done- the doctor in a biomedical system is a mechanic of the body, the person who IS that body is more an inconvenient, mouthy inhabitant than a part of (the whole of, even!) the body itself. the separation of this terror from its physical complement is not inevitable or necessary (that is, the lines we draw between the 'medical' and 'emotional' are not sacrosanct or even meaningful)

at what exact point did one of these ppl's sense of suffocation pass from a symptom of low o2 levels to a symptom of fear? why is the former the domain of a trained, skilled healer while the latter is left either to the patient alone or their frightened loved ones (or the awkward teenager they paid to help their mother work the netflix)

#also if the point u take from this is that the latter person should be a therapist#you've missed the point entirely#medical anthropology

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's raining heavily at my field site in Khwisero..I am taking shelter at a local joint. The joint is full of male customers drinking konyagi as they argue about the ongoing world cup games...got me thinking of how football has for ages been a gendered sport. We are only two ladies in the joint minus the waitresses. My fellow lady- customer appears to be struggling with a kienyeji (organic) chicken that has been bought by her male company who looks way older than her ( Baba sukari vibes) 🙈. Anyway I don't think her interest is on the game but kila nyani na starehe Zake.

1 note

·

View note

Text

(Accidental) Hospital Ethnography

CW: Injury, mention of blood, strong language

It's amazing how time moves you. The way it allows you to somehow stare at yourself and your experiences from a distance and think, "I overcame that, this moment -- those moments, have passed me." Granted, I write these words from a multitude of distances. A distance of timing, a distance of emotion, and a distance based on a mixture of humor and irony. To be honest, I think it's the only way I can truly reflect on exactly what happened and how I eventually have gotten past it (thus far). There is still much left room for healing and closure, but that doesn't mean I can't reflect while I'm "in it".

This entry is about how I broke my leg on my third day in the Netherlands after deciding to take up my first academic role post-PhD.

As expected, my transition post-PhD was a bit of a blur. I spent the first few months post-PhD viva high on a specific blend of absolute joy, release, and looming job-market-anxiety. Indeed, my last few years were very much coloured with the darkest of all inks -- potential unemployment for the foreseeable future. Many fine academics I knew who had graduated with their PhDs in recent years confided with me (and many others) of their precarity and uninspiring job prospects, if any. The job boards for "anthropology" were scarce, and yet, I knew so many other anthropologists. I mostly wrote of the idea of ever entering the academy. It just wasn't meant for people like me, which was something I not only read in my graduate reading lists (because there were literally no papers authored by "people like me") but also what I experienced first-hand in predominantly white institutions I had studied and trained at.

Somehow, despite all of this, I landed my first academic position. I packed up my house in Torino, Italy and marched forth towards Maastricht, The Netherlands with a mild optimism. This was a chance for a new start, so I intended to start it off "right". I attended the departmental social events, made friends with strangers on a Flixbus, and decided that I would bond with the country the best way I knew how: to skate it!

Through a random string of social media connects, I got wind of the Dutch national chapter of CIB or "Communities in Bowls", a global aggressive roller skating movement. It'd been about 1.5 years into my "aggressive" skating; I've slowly made my way around concrete and wooden bowls, ramps, and the like. As I love to self-describe my style and prowess in skating, I'm pretty much "mediocre shred, existential dread" in physical form. I could do the oddly complex things (e.g. cart-wheeling into a 3m+ bowl) and yet some of the fundamentals (e.g. anything fakie/backwards) were lacking.

On the fateful night of September 2nd I made my way to Area 51, a massive skatepark in Eindhoven. I hopped on a train, met more strangers, skated for 2 hours of the 4 hour event, and briefly enjoyed myself. After attempting a trick I've done numerous times -- 360 jump -- I decided to take it a step further and do so off the metal coping of a small ramp. After trying it once, and landing it, I did what us skaters do best...I decided I would try it a second time.

There's a cute little rhyme we always say in my skate team Botte di Culo, "Two to make it true". It's not our phrase of course, but the wild internet world of roller skating made us privy. So I tried my best to do the trick a second time, and unfortunately for me, I fell, and I immediately knew something wasn't right.

It was a chaotic moment. I'd just moved to a new country, I'm skating a new park, I'm skating with new people, and I was skating with a roller skate set-up I don't normally skate in. Every component was different: the boot, the wheels, the trucks, the whole lot. In hindsight, a true recipe for injury and disaster. I'm still proud I managed to do a lot of fun things on skates, regardless.

Laying on the ground, swearing up a storm and complaining about how I would have to explain to my new colleagues that I had broken myself, the kind skaters of CIB Netherlands propped me up with some ice for the remainder of the event.

Being both embarrassed and stubborn, I convinced myself I was fine. I watched the other skaters zoom around the bowl and do all the tricks I wanted to do. I felt shattered, broken before I could even show everyone in the group that I could actually skate. It was miserable. In the end, I hobbled to the central train station with two new friends, and ignored my pain. By the time I arrived at the Maastricht central station, my leg/ankle area was horrendously swollen. I attempted to step down from the platform , only to basically fall to the platform and be caught by a kind stranger who had been watching me acutely try to navigate the descent on the train. He was just passing through Maastricht, but thoroughly convinced my very stubborn self to head to the hospital...which sits across the street from my current office.

I "walked" into the emergency room at about 1AM on September 3rd. It was quiet, nobody looming around. Two intake nurses, one relatively young, and the other noticeably older. The younger one looked a bit disturbed when I spoke to her, "So I think I've hurt my ankle, is it possible to have some treatment?"

She asks me if I called ahead to warn them that I was coming in. How odd, this is a fucking emergency room. It's not life-threatening, why the fuck would I be calling in? She asks me if I have a Dutch health card, I explain to her I do not because I've just arrived less than 3 days prior. She waves me into a partitioned area of the waiting room. There's automatic doors separating the treatment waiting area and the general waiting area. In the space, the intake nurse sat behind glass and spoke to me through an intercom. I assumed she led me here for more privacy, but perhaps it was protocol. It really felt like I was being sequestered, given I couldn't leave the space without her letting me with a touch of a button. Herein I stepped into the fantasy of what I taught and researched -- global health. Oh yes, if this was an opportunity to collect some insights about the country I just moved to that was especially tailored to my weirdo brain, this was it. Yes, I was hurt, and could barely walk, but my brain was sprinting.

Staring at her through the glass, I explain that I have Italian residency and that while I don't have a valid health card on me at that moment, I definitely have insurance and could supply the paperwork. We have this little bureaucracy dance for 20+ minutes. By the end, she's convinced that I have no semblance of EU healthcare so I'd have to pay a triage fee of 111 euros. I begrudgingly accept after she explains I can fix it later. I explain that my bank cards aren't working in-country thus far because it appeared that Dutch systems are very anti-Visa and Mastercard and I had no cash on me. She smiled and says, "don't worry we take credit!" Well, as someone who grew up in the U.S., that response was a bit too gleeful for my liking.

Throughout this entire process, I was not allowed to sit down. I asked the nurse if I could have something to sit on, given I had probably sprained/broken my ankle, and she brushed me off saying that "it wouldn't take long". I am in pain, my brain is not mine. Am I being unreasonable for asking for seating? Maybe my injury isn't as bad as I think? At the 30 minute mark since my arrival, the gatekeeper of health, my dear intake nurse, let me pass through.

I plop myself down on a waiting room couch. It's cold, I'm in shorts and a crop top because I was skating. I begin to shiver, and then just outwardly cry. I cry large tears through my N95 mask -- I attempt to avoid soaking it in the process. I think about how alone I am, how my my friends who I was texting about the injury as well as my partner were all so far from me. Why am I crying? I need to be strong. I study this, I know this. It's not that bad. I'm not sure what crying will accomplish at this time, I need to preserve my phone battery to manage important logistical things. I can't keep texting Antonio, Dunia, and Matt my every move and emotion. But oh god, I'm so alone. My pain is mine and yet when I share it, it becomes more manageable...and I can't do that right now.

About an hour later, a GP triages me. She is kind, gives me a large dose of paracetamol and asks me about myself. "Are you a student at the university?" No, I'm a new lecturer in global health actually. My office is across the street and I teach next door. She laughs at this, explaining the ridiculousness of the unfortunate situation is getting to her a bit. I don't take it personally. It was a very unexpected and astoundingly shitty situation. She explains I'll be getting an x-ray to see the damage exactly, but she confirms I've probably broken or sprained something for sure.

I finally get a wheelchair from a new nurse who came onto my case. She comments that she finds it weird that nobody immediately got me a wheelchair if it was under the suspicion that I had hurt my ankle or leg. The other two intake nurses from before stare at me like vultures through the glass as the new nurse wheels me into the x-ray area. Two technicians, both relatively young, one man one woman. The woman tech helps me with my backpack, placing it carefully in a different area as we do my scan.

I lay there, machines purring. I keep thinking about how hungry I am and how alienating this all feels. I am broken and they will put me back together again so I can work! I will overcome! I keep thinking about how I would tell Antonio about how eerily green/blue everything was and how it reminds of of a grand 80s cyberpunk fantasy. I am a human and I am machine. Hooked up with wires testing my movement yet required to be perfectly still. I think about the podcast my former-supervisor Stanley put out about his own trip to the hospital while ill. I internally cringed at the irony of the student following the teacher, especially in this way.

A few minutes pass and the two technicians walk over to me. I look at them, they look at me. "Well so you've broken a bone" one says. Oh? I reply. The other technician immediately follows up with "Yeah it's fucked up."

Wheeled into another room to meet the trauma surgeon. The nice nurse plugs in my phone so I can have some connection with the outside world. I doom-scroll to dissociate. 30 minutes pass. The trauma surgeon waltzes in with my scans. She points out bits of the scan on a computer monitor, but I wasn't wearing my glasses and was too overstimulated to process everything. "So you have broken your leg." MY LEG? I'm clearly confused. She gestures towards the scan again, and low behold...I had broken my leg. The fibula. Towards the ankle. Clean through.

She asks me what I was doing. I explain I was roller skating and fell. She asks me about if I was wearing protection. Absolutely, obviously. I reassure her I have no symptoms of concussion, I don't think I even hit my head. Lots of people were there and can confirm. We move on. She says I'll need a cast and my recovery would take at least a month with it.

Two new nurses come in. They prepare my leg to be placed in a cast. They clean off my leg, which I deeply encouraged because I was skating before and felt gross. They ask me what colour wrapping I want. "I get a choice?" I respond. "There's dark blue, white, and red". How patriotic.

Like a weird synchronised dance, they wrap my leg. The older nurse positions my leg in a particular way, 90 degree angle. I hate it, it hurts. She tells me to flex my toes or I'll mess up my entire healing process. I force my leg into that position with her help, while the other younger nurse wraps continuously. They pull out special pairs of scissors, they're huge. They cut the remaining material around my leg, shaping it to the contours. The sound of a really large, sharp, pair of scissors cutting near the surface of your skin is very unnerving, I will say. Afterwards, the older nurse leaves.

The younger nurse chats with me about my treatment regimen. She asks me if the doctor mentioned how I would need to have an injection. Yeah of course. I'm not worried, I'm not scared of needles or anything. "Oh great!" she chirps. She comes back with a syringe all prepared and proceeds to...hand it to me?

"Excuse me what? I have to do it?" I ask. "Yes you do! Every day until the doctor tells you to stop. It's an anti-coagulant. You won't be moving loads and we wouldn't want you to form clots."

So there I am, holding a syringe. It's like 3AM. I'm tired. I'm hungry. I'm hurting. And now I have to fucking stick myself in the stomach with a syringe? Is this was it's like to have chronic illnesses with injection meds? All the theory and ethnographies I've read couldn't have prepared me for this. I've shadowed different hospital wings with gruesome bits throughout my career. I've had my share of gore. I've had my share of injections for traveling, COVID-19 being the most recent series of injections. But for some reason, I couldn't wrap my head around sticking a needle into my stomach while someone was watching.

Sensing my hesitation, the nurse begins to encourage me through words. "It's very simple, don't worry. It doesn't hurt." After about 30 seconds of these instructions, I pinched a fold of my stomach and stuck the needle in. I pause, watching the liquid drain entirely. A hint of pink pops through, blood I imagine. MY BLOOD. AH. I remove the syringe. I somehow don't bleed out.

The older nurse returns, a kind face. I speculate about how intake nurses are supposed to be mean and the triage nurses were kind. They're mean at the door, but kind once you get in. Suddenly my analogy of them as gatekeepers of care feels more appropriate and less rude. The two nurses explain that I would need to purchase crutches and hold out a teal coloured pair. Ah, my favourite colour. How appropriate. These vanity details keep me sane for the remainder of the night.

I pay for a lot of things that night. Triage. Meds. Crutches. The taxi ride home. A couple hundred euros I didn't even need to spend, which pissed me off. The taxi driver is very sorry for me, he explains that I'll be stronger when I'm healed. That's what they always say. I mean, what the fuck else are you supposed to say.

I walk across the threshold of my front-door entrance, full cast with crutches, after 5 minutes of fiddling with my keys at 4AM. My neighbours probably hate me. I convince myself that if I can eat a snack, shower, and change into pajamas, I'll survive this experience. So I do those things. I shower balanced on one leg, using a trash bag to make sure it doesn't get wet. I eat whatever is deteriorating in my fridge. I lay in bed, I cry more, up until sleep takes me. The exhaustion of dealing with an unexpected injury and a crash-course into the Dutch health system was overwhelming.

#medical anthropology#broken bone#ethnography#anthropology#hospitals#doctors#patients#medicine#blog#postdoc#postphd#phd#academia

0 notes

Text

Looking at a Systematic Review of Environmental Risk Factors for Child Stunting

Child stunting, characterized by impaired growth and development, is a significant public health concern globally. While nutrition plays a crucial role, there are other environmental factors that contribute to this condition. In this blog post, we will delve into the findings of a systematic review conducted by Vilcins et al. (2018) to highlight the key environmental risk factors associated with child stunting. This research sheds light on the multifaceted nature of stunting, beyond nutritional aspects, and provides valuable insights for effective interventions.

Household Air Pollution:

The systematic review by Vilcins et al. emphasizes the impact of household air pollution on child stunting. Exposure to indoor air pollution from sources like solid fuel for cooking and heating, such as biomass or coal, can lead to respiratory infections and chronic inflammation. These conditions can impair a child's growth and development. For instance, in regions where solid fuel is commonly used, such as parts of Africa and Asia, children exposed to high levels of indoor air pollution have an increased risk of stunting.

2. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Practices:

Inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities significantly contribute to child stunting. Vilcins et al. highlight how poor WASH practices, including limited access to clean water for drinking and hygiene, and inadequate sanitation facilities, increase the risk of infectious diseases and nutrient deficiencies. For example, in areas where open defecation is practiced, the risk of stunting is higher due to the increased likelihood of fecal-oral transmission of diseases like diarrhea and intestinal parasites.

3. Environmental Contaminants:

The presence of environmental contaminants, such as heavy metals and pesticides, is associated with child stunting. Exposure to these pollutants, either through contaminated soil, water, or food, can interfere with a child's growth and development. For instance, in agricultural communities where pesticides are extensively used, children may be exposed to these harmful substances, which can impair their cognitive development and contribute to stunting.

4. Poor Housing Conditions:

Inadequate housing conditions, including overcrowding, lack of ventilation, and dampness, are identified as risk factors for child stunting. These conditions increase the likelihood of respiratory infections, which can impact a child's nutritional status and growth. For example, in slum areas with crowded living spaces and insufficient ventilation, children are more susceptible to respiratory illnesses, leading to stunting.

Vilcins et al.'s systematic review highlights the environmental risk factors associated with child stunting beyond nutritional aspects. Household air pollution, poor WASH practices, exposure to environmental contaminants, and inadequate housing conditions all contribute to stunting. Addressing these factors requires comprehensive interventions that improve access to clean energy, promote proper WASH practices, reduce environmental pollution, and enhance housing conditions. By understanding and addressing the environmental risk factors associated with child stunting, policymakers, health professionals, and communities can work together to develop effective strategies for prevention and intervention. It is through targeted actions and investments in improving environmental conditions that we can reduce child stunting rates and ensure healthier futures for children worldwide.

References!

Vilcins, Dwan, Peter D. Sly, and Paul Jagals. "Environmental risk factors associated with child stunting: a systematic review of the literature." Annals of global health 84.4 (2018): 551.

#medical anthropology#medicine#global health#global medicine#child stunting#paediatrics#social determinants#systemic review#anthropology#scientific literacy#environmental factors

2 notes

·

View notes