#lionel baudelaire

Text

Lionel: How’s my princess doing, Sister?

Cattleya, smiles: I’m no princess, dearest.

Lionel: Why not? You’re marrying Hodgins, aren’t you? So you must be a princess!

Cattleya, slightly blushes: Oh, you! You’ve got quite the honeyed-tongue.

Lionel, winks: What better to compliment you with, dear Sister.

#submission#noctusfury#violet-evergarden-typo-quotes#violet evergarden#incorrect quotes#violet evergarden incorrect quotes#cattleya baudelaire#cattleya#lionel#lionel baudelaire#lionel blackthorne#original character#lionel is noctus's original character#violet evergarden fandom#anime#violet evergarden anime#violet evergarden funny#violet evergarden funny quotes

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We live, understandably enough, with the sense of urgency; our clock, like Baudelaire's, has had the hands removed and bears the legend, "It is later than you think." But with us it is always a little too late for mind, yet never too late for honest stupidity; always a little too late for understanding, never too late for righteous, bewildered wrath; always too late for thought, never too late for naïve moralizing. We seem to like to condemn our finest but not our worst qualities by pitting them against the exigency of time. Lionel Trilling

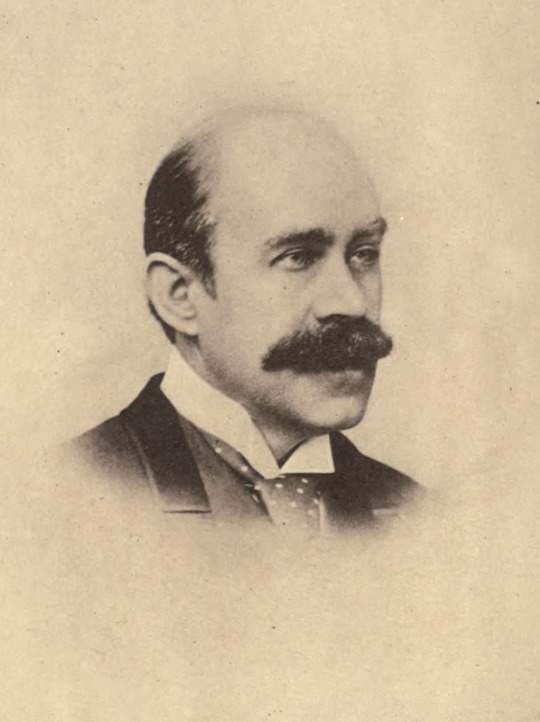

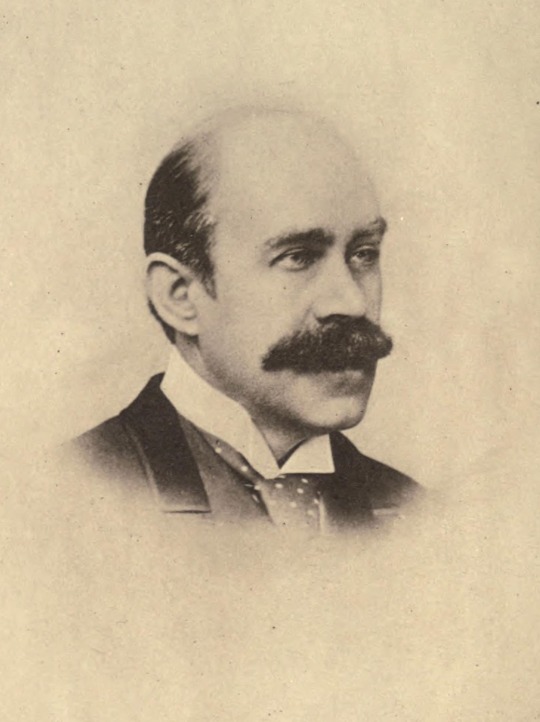

Takato Yamamoto

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les groupes

Baudelaire

La vie ne leur a jamais fait de cadeau, que ce soit à cause de drames familiaux, de difficultés dans le travail, de pauvreté. Ces habitant.e.s ont plutôt tendance à être pessimistes, pas très investi.e.s dans la vie au village de Saint Lionel sur Mer. Iels essaient de faire de leur mieux pour tenir le coup, attendant que le temps passe.

Musset

De manière générale, ces habitant.es vont plutôt bien dans leur vie. Tout n'est pas toujours rose, et certain.e.s regrettent souvent leur enfance, ou une période de leur existence où tout était mieux. Il y a des jours avec, il y a des jours sans, et iels l'ont plutôt accepté. Iels sont investi.e.s ou non dans la vie au village, mènent leur vie plutôt normalement.

Rimbaud

Ces habitant.e.s sont rayonnant.e.s, solaires, toujours très optimistes, iels semblent mener une vie parfaite, au moins en apparence. Chaque jour, iels essaient de rendre leur vie ainsi que celle des autres meilleures. Iels sont très investi.e.s dans les activités de la ville, participant au moindre évènement, et leur joie de vivre ferait presque d'elleux les petites célébrités de Saint Lionel sur Mer.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

LA MAUVAISE GRAINE

Lionel Bourg, La faute à Ferré, p7,13..: J'avais quinze ans. Seize peut-être. Ou dix-sept.. L'âge où Rimbaud fracasse l'ennui des jeunes gens, renversant tables et pupitres… Et puis.. C'était un soir d'hiver…Il faisait sombre dans la salle. Le rideau s'ouvrit. Le type debout chantait…Je n'en suis pas revenu. C'est qu'il chuchotait ou toutes voiles dehors cinglait mieux que ce grand bateau descendant la Garonne dont la chanson parlait, / qu'ils étaient beaux à n'y pas croire, à haleter comme au cours des plus folles escapades, ces mots qu'il lançait devant lui, / et Baudelaire alors, les araignées qui tendent leur filet au fond du moindre cerveau, / ou cette enfance, c'était la mienne, pantelante (souviens-toi, souviens-toi, “les souliers usés, l'innocence rapiécée”…), / il chantait, sur la scène, toi rivé à ton siège: “j'suis ni l'oeillet ni la verveine/ je ne suis que la mauvaise graine”…

#Léo Ferré#La mauvaise graine#Arthur Rimbaud#LE BATEAU ESPAGNOL#Charles Baudelaire#Spleen#L'enfance#LIONEL BOURG#LA FAUTE À FERRÉ

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

My List of Future Anime/Manga Fanfics

NOTE: Most of these titles are temporary and may not be official titles.

.

.

Cattleya and Her Dandelion (a Violet Evergarden series)

This story focuses on the backstory of Cattleya Baudelaire. This is slightly based from the light novels, where Cattleya ran away from her parents, ultimately becoming a dancer, before eventually meeting Hodgins. But there’s another addition to this very vague backstory — one that I believe is not only plausible, but also has a beautiful message behind it.

This trilogy is about Cattleya’s past, but she’s not the only one. Her younger brother, Lionel, is also involved. When Cattleya has a breakdown after watching a play that reminds her so much of her brother, she tells the Gang her story and how she came to be a Doll. She tells them where she’s originally from — Bociaccia (my personal headcanon) — and of her family. She tells them that her name isn’t really Cattleya, but her real name is Cornelia DeGaul, but changed it when she ran away. She told them of her family and how they treated her, and how she did not know love until her little brother came along. She took care of him and became like a mother to him. When he could use words, he misspoke her name and called her “Cattleya”, and thus her name. And she called him “her Dandelion” due to his coloring and his personality and how he made her happy.

Eventually, when her parents plan on sending her to a special school to prepare her for marriage, she plans on running away, and does so, planning on returning once she’s older so that she can rescue her brother, knowing that currently she can’t do anything. She travels around until she eventually becomes a dancer and eventually meets Hodgins during the Great War. Once the Great War is nearing its end, they go to her hometown to find her home destroyed and her parents dead with the possibility of Lionel being dead, too. And she grieves that she had gotten here too late and regrets not have taken him with her.

Then many years later, Iris gets a client who’s in Bociaccia and gets excited to go some place outside of Leiden. She then discovers something that will change her whole world.

Also, as far as pairings go, Iris will get together with someone, along with Cattleya/Hodgins, Benedict/Erica, Luculia/Unnamed Fiance, and either Violet/Gilbert or Leon/Violet.

Iris College AU (a Violet Evergarden AU story)

Modern AU. In her childhood, Iris met a boy called Leon who visited family during summer vacation and became great friends. But unfortunately he had to return home and through circumstances never saw him again. With him still in the recesses of her mind, Iris goes to college. And it’s a new and fascinating experience for her. She does judo and has a part-time job in a maid cafe.

In her third year, a young man by the name of Lionel Baudelaire enters her college as a freshman. And, for some reason, seems to have taken a shine to her, and embarrassingly calls her “Senpai”. Iris runs into him wherever she goes: her Judo classes, at the cafe where she works, at the cafe she dines at with some friends, even the library. Why does this man have such a fascination with her? Is he a stalker? Or will this end up blooming into an unlikely friendship?

Pairings: Iris/OC, Cattleya/Hodgins, Benedict/Erica, Luculia/Unnamed Fiance and either Gilbert/Violet or Leon/Violet.

Wormwood’s Shadow (a Violet Evergarden story)

This story will be OC-focused and will be about a Leidenschaftlich officer who is forced by his superiors to lead his battalion with other units through a forest on faulty intel and get ambushed by Gardarik forces. The officer (who I’ll name Wormwood for now) is one of the only few who survive the tragic onslaught, his unit all-but annihilated. But he was badly scarred and lost an eye. As he recovers from his injuries, he grieves, and resolves to go to the families of his unit and support them as best as he can. To any whom are still alive, he offers them a job so that they can provide for their families. He also builds a memorial for his lost battalion. He eventually meets the wife-turned-widow of his superior, who sent him on that ill-fated mission and they eventually get married.

A few years after the Great War ended, General Munter sends for him and informs him of his plan to resurrect the Sturmtruppen special units and offers him a commission and a command of one of the two regiments being formed. After thinking about it, and consulting with his wife, he agrees and works together with a revealed and definitely-not-dead Gilbert Bougainvillea, now a colonel like him. However, their superior is yet another stupid and glory-hungry idiot that they have to contend with.

When war breaks out again a year later — a small one breaking out between Salbert Holy State vs Gnizen Union and Bociaccia — Wormwood’s and Gilbert’s forces, among others, are sent to quell the conflict. Will he be able to change the past and prevent history from repeating itself?

There’s more, but that’s the jist of it. Pretty much an angst/drama fic.

Conflict in Leiden (a Violet Evergarden story)

This story will be on the escalating and gradually accumulating conflict in the Leidenschaftlich government as a Pro-Monarchy faction rises up to advocate the reinstallation of the Royal Family, who centuries ago were forced to become an aristocratic family as the aristocrats insisted on being in charge of the nation due to their power. But due to several calamities, cries for the reinstitution of the monarchy have been voiced, resulting in a potential civil war. And I plan on Gilbert making a comeback.

Another Great War (a Violet Evergarden story)

It is 30 years after the First Great War during Violet’s generation. Now Gilbert and Violet’s children have to experience another Great War that looms on their doorstep. What must they do to overcome it? Can they survive this second international conflict?

I’m not really sure whether to have Gardarik be the aggressor again, or Salbert Holy State, or Ctrigall, one of the Southern nations, or even an entity outside of the continent. Hmm...

(Seriously, I’d LOVE to know if other nations inhabit those land masses north and south of Telesis or not.)

—

—

The Third Great War (A Violet Evergarden Story)

It is 25 years later and Violet experiences yet a THIRD Great War — and this time, Leidenschaftlich is the aggressor due to several key events. And she has to watch her children and grandchildren go through the trial of fire yet again, and reminisces on her own memories — especially now that her beloved Gilbert is on his sickbed, gravely ill.

The Lost Letters (A Violet Evergarden Fiction/Nonfiction Hybrid Story)

This will be a “nonfiction” work based on the special episode 14 where Mr. Roland shows Violet the abandoned warehouse full of letters and packages that will never reach their destination. I felt super sad about that, so I thought of the idea to write a work where the letters will have a chance to reach people (you). People from various walks of life and in various occupations will write. Let me know what you’d like to see!

The Ctrigallian Chronicles (a Violet Evergarden Fiction/Nonfiction Hybrid Story)

A nonfiction/fiction/biography that goes into the POVs of various Ctrigallian soldiers fighting during the sudden and violet civil war and also dealing with the Gardarik insurgents. Every one-shot will tell their story. Based on episodes 11-13, particularly episode 11. Might even have it where Aidan Field stays alive. (Because I kinda want that to happen.)

Into Telesis (A Violet Evergarden Nonfiction)

This nonfiction will essentially get into detail about the various nations of Telesis, getting into their history, culture, politics, customs, etc. Since much of this world has been left blank, it’ll be up to me to detail it as best as I can while keeping it loyal to the VE world.

The Phantom Son (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

Part of the “Chronicles of Clarines” series.

(OMC-centric)

[Himawari (OMC) & Everyone, Zen / Shirayuki, Mitsuhide / Kiki, Himawari (OMC) & Zen, Izana / Haki, eventual Himawari (OMC) / Kiharu | Kihal, and others]

Cursed with an unknown condition that forces him to avoid the sun, Himawari, eldest son of a baron in one of Clarines’ easternmost fiefs, has had to live his whole life semi-alone and forced to live with shame for not being normal and cursed with being unable to live a normal life. When his father decides to disown him and gives his birthright to his younger brother, and kicks him out of their family estate in disgrace, Himawari, with his Companions who decide to follow him, and his hawk, rides out into unknown horizons, eager to meet other people, make new experiences, and hoping to find a cure for his ailment.

When trouble strikes, Fate leads him to Zen and Shirayuki, and the others. Grateful for their assistance, and already having a great admiration for Prince Zen, pledges himself in eternal service as Zen’s vassal. An opportunity comes to test that loyalty when the “Yuris Island” debacle came to Wistal Castle. It’s also when he meets Kiharu Toghrul, Yuris Island local representative, for the first time — though they never have any direct contact at first. Once the debacle’s over, surprisingly, Prince Zen names Sir Himawari as Lord of both Yuris Island and the rest of Lord Brecker’s lands, and gives him the title of Baron, tasking him with the important duty of protecting Yuris Island’s becoming-endangered Blue Parrots as a new asset to the Crown.

Will Himawari be able to be accepted for who he is despite his condition? Will he be able to fulfill the duty that his master has given him and exceed his expectations? Will Lord Brecker or the other nobles give him trouble? But more importantly, will Himawari ever find a cure for his “sun sickness”? Or is he cursed to live out this fate for the rest of his life?

The Blue-Haired Omen (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

Part of the “Chronicles of Clarines” series. And part of the “Tales From Other Nations” series.

(OMC-centric)

[Roruko (OMC) & Everyone, Zen / Shirayuki, Mitsuhide / Kiki, Himawari (OMC) / Kiharu | Kihal, Izana / Haki, eventual Roruko / OFC, and others]

This story — set one year after the events of Book 1 — focuses on a young prince in a foreign nation who’s a neighbor to Clarines. Called Roruko, he’s the sixth son of seven sons and one girl — for a total of eight children. His elder brothers, though, are only half-bloods, since he and his younger siblings were birthed by their father’s second wife and queen. And with the exception of the eldest, the others don’t like them at all. What’s worse is that due to his birth being heralded by natural disasters, his blue hair — which would’ve usually been held as a sign of good fortune — is considered a bad omen and is thus shunned and scorned by everyone. Only his Companion, parents, eldest brother, and his younger siblings love him and aren’t swayed by this prejudice.

Then his elder brother summons him and gives him his first fief to rule over: a backwoods district that would be a good starting point for Roruko to hopefully make a name for himself as a prince and a ruler. The problem? The condition it’s in is nowhere near what the reports say, and even worse is that the populace look at him in askance, and crime rate is moderate, with reports of people getting abducted, missing, or killed. And Roruko has no choice but to roll up his sleeves, roll with the criticisms and prejudice, and do what he came here to do.

However, just as his subjects start thawing to him, an epidemic rolls in, forcing Roruko to ride to Clarines and beg for their help in dealing with it. And if it weren’t enough, news just comes to him from the capital: his country is now at war with another nation invading their borders!

In this coming-of-age story, can Roruko survive? Can he overcome and sway the prejudice towards him through his actions and drive? Or will he fail and lose both reputation, home, and family?

—

Other fics in the “Chronicles of Clarines” series:

Book 3 “The Unwanted War” || (CC-and-OC-centric) || [Zen / Shirayuki, Izana / Haki, Mitsuhide / Kiki (or Hisame / Kiki temp), Himawari (OMC) / Kihura | Kihal, and others] || Set two years after the events of Book 2, a prince of a foreign nation is struggling in a war against an enemy that they’ve been fighting for 30-odd years. And they’re losing. Not only that, but his father was assassinated, leaving him to take the reins and inherit their war. With their land being invaded and much of it taken by the enemy, the new ruler of the principality has to find a way to win the war and end it permanently. When the enemy nation’s relations with Clarines starts deteriorating — to the point that war starts being declared — the prince rescues Clarines from that and offers an alliance with them against their now-mutual adversary. What will happen to Clarines and their new ally? Will they win the war, or will the enemy be victorious? How did Clarines even end up in this war to begin with? Can their new ally even be trusted?

Book 4 “The Conspiracy” || (CC-centric) || [Zen / Shirayuki, Izana / Haki, Mitsuhide / Kiki, Himawari (OMC) / Kihura | Kihal, and others] || Set after the events after Book 3, it’s not long after the war, and Zen and Shirayuki are finally ready to tie the knot. However, dissent begins to rise from the North as there are some who still disapprove of the union (and just want the excuse to rebel), and also wanting to avenge Touka Bergatt. And Zen and Izana are their targets. Can they be able to withstand another Northern rebellion and conspiracy? Or will the North finally be victorious and be able to either establish a new dynasty or secede from Clarines and form their own entity?

Book 5 “The Missing Princess” || (CC-and-OC-centric) || [Eventual OMC / OFC pairing, as well as Zen / Shirayuki and other pairings] || A story set 15 years after the events of Book 4, a princess was travelling to another realm via ship when a fierce storm blew and caused it to sink. When she wakes up, she doesn’t remember anything except her name and later finds out that she’s in Clarines. Thinking that she may be a woman of high rank, she’s sent to the palace of Wilant — Prince Zen’s residence — where Shirayuki can take care of her. Can this unknown woman remember her identity? And what is this news about a missing foreign princess? Could the two be connected, or just a coincidence? And why does Prince Zen and Shirayuki’s son seem to take such an interest in her?

There MIGHT be more books after this, but we’ll see. These last 3 books are more story ideas than anything else. I literally haven’t done anything past that. They’re not fleshed out or outlined at all compared to the first two books of this series.

Other future stories in the “Tales From Other Nations” series:

Book 3 “The Diarchal Succession” || (OC-centric) || [Several OMC / OFC pairings, as well as mentions or possible showings of Zen / Shirayuki and other pairings] || A story of twins who will end up thrown in a conspiracy when their father makes the decision to have them both be his successors and later rule the Kingdom as one, rather than having the eldest twin rule as is the usual custom of succession. Naturally, the court opposes this, even though the king has already made it a decree and can’t be revoked, saying that it would only cause friction and dissention if there is more than one ruler. Can the twins be able to prove their father correct, or will they be forced to compete for the throne? Or will they simply perish in this game of thrones?

Book 4 “The Exile” || (OC-centric) || [Several OMC / OFC pairings, as well as mentions or possible showings of Zen / Shirayuki and other pairings] || A story of a royal family who has ruled their nation in complete peace and safety, until a radical political body attempts to seize power of the country for itself, and thus starts a coup to overthrow the current monarchs. Caught totally off-guard, the royal family is forced into hiding and take refuge in another country. Will they be able to return and defeat their enemies and reclaim the stability of the nation? Or will they be found and slain?

Book 5 “The Dictator” || (OC-centric) || [Several OMC / OFC pairings, as well as mentions or possible showings of Zen / Shirayuki and other pairings] || A story of a nation in need of a leader during a dark period — and a man who’s ambition for power and a legacy as a ruler of his country knows no bounds. In his fight for the top, he uses his silver tongue, charisma, luck, and sheer cunning to keep up with his rivals. A chronic opportunist able to turn any situation, no matter how dire or disadvantageous, into an advantage, he is a shrewd politician. This is his story.

Book 6 “The Hidden Royal” || (OC-centric) || [Several OMC / OFC pairings, as well as mentions or possible showings of Zen / Shirayuki and other pairings] || A story of a young prince/princess who has secretly been sent to another nation for an education. When a family member starts a cue and slaughters most of the royal family to take power for himself, the usurper is unaware of the existence of the royal, thinking him/her to have been killed or died. But when the royal hears of the tragic news of his family’s deaths, they’re conflicted on whether they ought to return home, or remain in the kingdom that has been like a second home and family to them. What decision will they make? And what happens if he ends up found?

There MIGHT be more books after this, but we’ll see. These last 4 books are more story ideas than anything else. I literally haven’t done anything past that. They’re not fleshed out or outlined at all compared to the first two books of this series.

Raj’s Story (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

Part of the “Tales of Tanbarun” series.

This story follows Prince Raj after the events of Season 2 as he begins to metamorphosis into the Crown Prince that Tanbarun needs, and that Shirayuki can be proud of. As he grows, as he learns, as he’s conflicted over his feelings for Shirayuki (and his family’s schemes to get them together), he goes on a figurative journey as his life takes on a new course of self-discovery. His fame for his daring confrontation and elimination of the pirate threat on the seas has skyrocketed and Tanbarun is the focus on new recognition by other countries. One of whom is an island nation south of Tanbarun who’s heard of his exploits and have sent envoys to not only praise him for his heroic deed but also request a formal alliance and a trade agreement, and also offers their princess’s hand in marriage to him. How will Prince Raj react to this proposal? Will he fulfill his Quest that he gave himself? Will he become the Prince that his people can be proud of?

More stories in the “Tales of Tanbarun” series:

Book 2 “Blind Ambition” || (OC-centric) || [Several OMC / OFC pairings, as well as Raj / OFC and mentions of Zen / Shirayuki] || This is a story independent from the rest of the series, but is still part of the world. (I’m not sure where to set this story at yet, but probably before or after Book 4. Maybe.) A blind princess who has a tendency for trouble and impish pranks is eager to show everyone that she won’t let them think that she can’t do something just because she’s a woman, and often drags her hapless and harassed Companion around while she does it.

ZenYuki Mulan AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

In order to escape the pursuit of Prince Raj of Tanbarun, she disguises herself as a man, and becomes the Royal Guard’s healer, where she meets Prince Zen as he trains his unit in preparation for war as his brother leaves with the army. Will she be discovered? Will she fall in love? Will Prince Raj find her?

(Might also do a ZenKiki version of this as well.)

MitsuKiki Mulan AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

A story where Kiki runs away to be a Knight, and runs into Mitsuhide, who trains their unit in preparation for war.

RajiYuki Beauty and the Beast AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

A story where Prince Raj becomes a Beast due to his lifestyle, causing himself and the entire castle to be put under a curse, and he feels like he has no hope of ever lifting it. Until one day, a girl named Shirayuki comes to the castle. Can she be the prophesied one who can lift the curse? Can she heal Raj’s insecure and immature heart and transform him into the Crown Prince that Tanbarun needs?

Narnia AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime/Narnia Story)

A story where Zen, Shirayuki, Mitsuhide and Kiki (or Raj and Kihal, or Raj and Kiki), with the addition of Obi, end up in Narnia and become its Kings and Queens there.

WWII AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

A story — or even a series of stories — where Zen, Shirayuki, and the cast of ANS are in various scenarios in WWII. Anywhere from pilots, tankers, infantry, paratroopers, or even navy personnel.

Sengoku Period AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

A story where the ANS world is in Feudal Japan during the Sengoku Jidai Period. I’m still unsure as to the roles yet. Not sure if the Wistalia family should be an Imperial, a Shogunate, or a Daimyo family.

RajiYuki Book of Esther AU (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Story)

A story inspired from the Book of Esther in the Bible, where Shirayuki becomes an eventual Princess of Prince Raj, but the Chief of the Court — the King’s Chief Administrator — seeks the destruction of her people, the Lions of the Mountain, viewing them as a threat to his power and wants them eliminated. Can Shirayuki rescue her family and clan from their fate?

Clarines and Other Kingdoms (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Nonfiction)

A nonfiction detailing the customs, cultures, summaries, geographies, and other info concerning every country, including Clarines and Tanbarun. Will mostly include OC kingdoms and nations that you may or may not see in my stories.

The Histories of Clarines and Tanbarun (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Nonfiction)

A nonfiction detailing the histories of Clarines and Tanbarun, respectively. Will also include the history of the ANS story thus far.

A Noble Alliance: The History of the Friendship Between Clarines and Tanbarun (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Nonfiction)

A nonfiction focusing and detailing the history of the relationship and friendship between Clarines and Tanbarun.

The Prince and the Healer: Behind the Story of Prince Zen and Lady Shirayuki’s Fateful Meeting (An Akagami no Shirayuki-hime Nonfiction)

A nonfiction detailing the famous story of Prince Zen and Lady Shirayuki, of their history together, and their eventual union.

The Drakers (a Drifting Dragons Nonfiction)

Essentially a “history” of the Drakers and the art of Draking. I don’t plan on this being a long story. Probably no more than a long one-shot or three chapters and certainly no more than 5. Unless, of course, this work speaks to me and lets me know that it needs to be bigger.

The Life of A Draker (a Drifting Dragons One-Shot Collection)

This is going to be a whump one-shot collection of characters of every kind experiencing various kinds of whump. I won’t get too graphic or dark or anything, but I thought it’d be neat. Let me know what platonic pairings you’d like to see and who to whump.

What Your Searching For (A Drifting Dragons story)

I haven’t really flushed this idea much except I plan on an OC who signs up aboard the Quin Zaza to search for his long-lost brother. He’s a surgeon and an ex-Royal Marine and is well-connected. (I’m rather annoyed that these guys don’t have a qualified surgeon aboard. I mean, what if any of them got seriously injured?!) He becomes great friends with Yoshi and Takita, Capella and Mannie have a thing for him, and Vannie is curious about him. And an annoyed Mika watches on. lol XD

Again, I don’t really have much fleshed out on this. This was more of a recent idea.

The Princess & the Draker (A Drifting Dragons story)

Kinda inspired by “Princess and the Pauper”. Kinda. I’ve only just come up with thia idea, so I don’t know the gist of it. Basically, Vannie’s a princess and meets Mika who’s a Draker.

Or I could have Mika be the Captain of the Guard or whatever. Have it be an AU. Or something.

Yeah, probably.

<><><><><><>

Anyway, besides these, I’ll also be doing fanfics for other animes such as

Drifting Dragons

Cells At Work

Demon Slayer

Teasing Master Takagi-san

Garden of Words

Your Name

...and a few others.

#noctusfury#anime#manga#fanfics#anime fanfic ideas#manga fanfic ideas#anime / manga#anime and manga#fanfiction#list of anime and manga fanfic ideas#violet evergarden#violet evergarden fandom#'violet evergarden fanfics#violet evergarden story ideas#akagami no shirayukihime#akagami no shirayukihime fandom#akagami no shirayukihime fanfics#akagami no shirayukihime story ideas#snow white with the red hair#snow white with the red hair fandom#snow white with the red hair fanfics#snow white with the red hair story ideas#drifting dragons#kuutei dragons#kuutei dragons fandom#kuutei dragons fanfics#kuutei dragons story ideas#drifting dragons fandom#drifting dragons fanfics#drifting dragons story ideas

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aestheticism

"the aesthetic end is the perfection of sensuous cognition, as such: this is beauty." - Alexander Baumgarten, Aesthetica [1750]

Having its chief headquarters in France aestheticism, or alternatively known as the aesthetic movement was a European movement during the latter part of 19th century. In opposition to Science, and in defiance of the widespread indifference or hostility of the middle class society of their time to any art that was not useful and that did not teach any morals.

French writers developed the view that a work of art is the supreme value among human products precisely because it is self sufficient and has no use or moral aim outside it's own being.

The end of the work of art is simply to exist in its formal perfection; that is, to be beautiful and be contemplated as an end in itself - "l'art pour l'art" art for art's sake.

Historical Roots

Aestheticism was developed by Baudelaire, who was greatly influenced by Edgar Alan Poe's claim that the supreme work is a "poem per se" a poem written solely for the poem's sake. Immanuel Kant in his Critique of judgement [1790] said that "pure" aesthetic experience consists of a "disinterested" contemplation of an object that "pleases for it's own sake" without reference to reality or to the "external" ends of utility.

The views of French Aestheticism were introduced into Victorian England by Walter Pater.

The artistic and moral views of Aestheticism were also expressed by Algernon Charles Swinburne, and by English writers of 1890 such as Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons and Lionel Johnson [OAL]. The influencers of this idea stressed the view of autonomy [self-sufficiency] for a work of art.

#literary#english literature#literary theory#aestheticism#victorian era#studyblr#aesthetic notes#personal

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Bonjour! est-ce que vous savez le poète Richard Siken? je cherche pour plus de poèsie française et modern par les poètes lgbt, si vous pouvez m'aider!

Hello,

Careful, to talk about people, you want to use the verb Connaître!

Here are some resources (politics, movies, novels, theory); when it comes to classic poetry, I think immediately of naughty naughty boys Paul Verlaine (Mille et Tre for example) and Arthur Rimbaud (Jeune goinfre) - whose relationship can remind you of Wilde and Douglas. You can also check Cocteau, Villon (I wasn’t able to find free content for him) and Pierre Louys’ incredible Chansons de Bilitis (potential translation of queer antique poems).

When it comes to modern poetry, I can recommend the works of Gabriel Kevlec and Lionel Briois. I’ll come back and add more stuff if I find any.

Now if you want to read the works of queer figures regardless of their content, you can check Baudelaire, Proust, Colette, and many many more.

Hope this helps! x

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aestheticism

"the aesthetic end is the perfection of sensuous cognition, as such: this is beauty." - Alexander Baumgarten, Aesthetica [1750]

Having its chief headquarters in France aestheticism, or alternatively known as the aesthetic movement was a European movement during the latter part of 19th century. In opposition to Science, and in defiance of the widespread indifference or hostility of the middle class society of their time to any art that was not useful and that did not teach any morals.

French writers developed the view that a work of art is the supreme value among human products precisely because it is self sufficient and has no use or moral aim outside it's own being.

The end of the work of art is simply to exist in its formal perfection; that is, to be beautiful and be contemplated as an end in itself - "l'art pour l'art" art for art's sake.

Historical Roots

Aestheticism was developed by Baudelaire, who was greatly influenced by Edgar Alan Poe's claim that the supreme work is a "poem per se" a poem written solely for the poem's sake. Immanuel Kant in his Critique of judgement [1790] said that "pure" aesthetic experience consists of a "disinterested" contemplation of an object that "pleases for it's own sake" without reference to reality or to the "external" ends of utility.

The views of French Aestheticism were introduced into Victorian England by Walter Pater.

The artistic and moral views of Aestheticism were also expressed by Algernon Charles Swinburne, and by English writers of 1890 such as Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons and Lionel Johnson [OAL]. The influencers of this idea stressed the view of autonomy [self-sufficiency] for a work of art.

0 notes

Text

Des classiques censurés http://revue.leslibraires.ca/articles/sur-le-livre/des-classiques-censures

Candide (1759) Voltaire

Ce conte sera jugé trop subversif ainsi que « pernicieux » par l’Église et se retrouvera ainsi sur la fameuse liste de l’Index. Le parlement ainsi que la Chambre syndicale des imprimeurs et libraires séviront également contre Voltaire. À la mort de ce grand auteur en 1778, l’Église lui refusera les obsèques religieuses à Paris : ultime réplique aux écrits de celui qui a souvent mis à mal l’autorité religieuse.

Ne tirez pas sur l’oiseau moqueur (1960) Harper Lee

Bien qu’il ait reçu le Pulitzer, ce roman n’a pas toujours fait l’unanimité, au Canada comme aux États-Unis, en raison des sujets abordés – viol et inceste – et du langage outrageant et raciste utilisé, qui reflétait pourtant la réalité de l’Amérique des années 30. Si plusieurs parents ont demandé aux écoles de retirer ce titre, c’est tout de même plus de 30 millions d’exemplaires qui ont été vendus dans le monde entier!

Lolita (1955) Vladimir Nabokov

Ils sont nombreux, les pays à avoir banni, plusieurs années durant, Lolita : France, Angleterre, Argentine, Nouvelle-Zélande, Afrique du Sud. Cette histoire, habilement écrite, d’un écrivain qui tombe follement amoureux d’une fille de 12 ans est encore de nos jours controversée en raison de son caractère pédophile, voire incestueux, puisque Humbert est le beau-père de Lolita...

Les aventures de Sherlock Holmes (1881) Arthur Conan Doyle

Les premières aventures du célèbre détective n’ont pas été appréciées par l’Union soviétique. Les autorités jugent que M. Doyle fait l’apologie du spiritisme et de l’occultisme et interdisent le livre en 1929. Or, il semblerait que les États-Unis aient aussi censuré l’auteur britannique. En effet, une circonscription scolaire de l’État de Virginie a retiré Une étude en rouge de son programme en 2011, invoquant la représentation négative de la religion mormone.

Les fleurs du mal (1857) Charles Baudelaire

En 1857, deux ouvrages majeurs de la littérature française se retrouvent sur le banc des accusés. Si Madame Bovary de Flaubert n’est finalement pas condamné pour outrage à la morale publique, Les fleurs du mal n’aura pas cette chance. En plus d’écoper d’une amende, le poète maudit doit faire le deuil de six poèmes frappés d’interdiction, et ce, jusqu’en 1949, c’est-à-dire pendant près de cent ans.

Sa majesté des mouches (1954) William Golding

Après un écrasement d’avion, un groupe de jeunes garçons survit sur une île. S'ils sont d’abord enchantés, c'est leurs besoins primaires qui prennent ensuite le dessus sur leur civilité. Démonisé pour sa saveur profane, banni des écoles pour violence extrême et mauvais langage, taxé de raciste, d’antiféministe et de diffamatoire à l’endroit des handicapés (le souffre-douleur est asthmatique…), ce roman a de quoi faire peur à certains : il démontre que l’humain, après tout, est possiblement un être sauvage…

Classiques québécois censurés

La Scouine (1909) Albert Laberge

Anticipant que l’Église n’apprécierait pas son portrait volontairement sinistre de la vie rurale, l’auteur – pionnier du réalisme et du naturalisme québécois – décide de publier les chapitres de son livre dans différentes publications, et ce, durant plusieurs années. Il s’attire néanmoins les foudres de l’archevêque de Montréal en 1909 avec le chapitre « Les foins » publié dans l’hebdomadaire La semaine, dès lors interdit.

L’appel de la race (1922) Lionel Groulx

Écrit sous un nom d’emprunt, le premier roman de Lionel Groulx secoue la bourgeoisie québécoise avec son personnage ultranationaliste qui sacrifie son mariage avec une Anglaise convertie pour répondre à « l’appel de la race ». Les jésuites irlandais, particulièrement, ont entrepris des mesures pour faire interdire l’ouvrage, allant même jusqu’à cogner aux portes du Vatican.

Classiques jeunesses censurés

Les aventures d’Alice au pays des merveilles (1865) Lewis Carroll

Alice n’a pas que traversé de l’autre côté du miroir, elle a aussi traversé le temps. Ce classique de la littérature a étrangement attiré les foudres de certains. En 1931, la Chine interdit ce titre sous prétexte

qu’il était indécent de faire parler des animaux comme des humains, et donc de les rendre égaux. Une raison qui nous apparaît aujourd’hui insolite… Après tout, tout est possible dans l’imaginaire. Surtout au pays des merveilles.

Jeanne, fille du Roy (1974) Suzanne Martel

À la traduction de ce roman historique hautement réaliste, l’éditeur anglophone, sans en avertir l’auteure, coupe et modifie certains passages où la narratrice, qui arrive tout juste au Canada et n’a pas encore apprivoisé cette terre et les Amérindiens qui y vivent, fait preuve de préjugés à leur égard. Mais ça ne suffit pas : la commission scolaire de Régina retire tout de même le livre, criant au racisme. « On ne peut réécrire l’Histoire pour qu’elle soit "politiquement correcte" », défend Martel.

Ève Paradis (1987) Reynald Cantin

La trilogie de Cantin, rééditée depuis en un seul tome, fut interdite d’achat par les bibliothèques du Conseil scolaire Chauveau et boycottée en 1991 par une école secondaire québécoise. Que l’auteur ait été professeur durant quinze dans cette même école n’y change rien : le langage, l’inceste abordé et l’avortement décrit sont montrés du doigt.

Ani Croche (1985) Bertrand Gauthier

L’Association des parents catholiques du Québec porte plainte contre ce roman signé par le fondateur et éditeur de la courte échelle. On reproche à Ani Croche son non-respect de l’autorité mais, surtout, la chanson que l’héroïne invente pour parodier les dix commandements. Le roman n’a finalement été ni banni ni censuré, et l’immense brouhaha médiatique autour de ces récriminations aura certainement contribué à la vente des 60 000 exemplaires!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

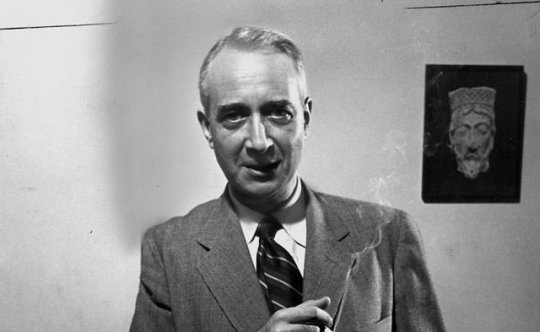

Lionel Trilling was born 4 July 1905, and died 5 November 1975

Nine Quotes

It is now life and not art that requires the willing suspension of disbelief.

Where misunderstanding serves others as an advantage, one is helpless to make oneself understood.

Literature is the human activity that takes the fullest and most precise account of variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty.

The poet is in command of his fantasy, while it is exactly the mark of the neurotic that he is possessed by his fantasy.

We live, understandably enough, with the sense of urgency; our clock, like Baudelaire’s, has had the hands removed and bears the legend, “It is later than you think.”

What marks the artist is his power to shape the material of pain we all have.

The function of literature, through all its mutations, has been to make us aware of the particularity of selves, and the high authority of the self in its quarrel with its society and its culture. Literature is in that sense subversive.

The poet may be used as a barometer, but let us not forget that he is also part of the weather.

After all, no one is ever taken in by the happy ending, but we are often divinely fuddled by the tragic curtain.

Trilling was an American literary critic, short story writer, essayist, and teacher.

Writers Write

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

(i will squeeze the life out of you) so shed your skin and let's get started

or: four times lena luthor was hugged by someone, and one time she hugged someone.

i meant to post some smut on the occasion of my birthday, but no one had had an orgasm 1200 words in so instead here is the saddest, most unsexy ficlet i could manage. this was mostly written post medusa as part of #hugs4lena2k17.

...

She doesn't remember where or when it was, she just remembers.

Her mother is a giant in her memory, towering above her. In a photo that is currently in storage with the rest of her Metropolis apartment, the woman is small, with sharp eyes and dark hair just like Lena's— the source of Lena's— but in her memory the woman is the whole world.

Her arms enveloped, and held Lena in her lap so tight that Lena had squealed to be let free even as she burrowed and clung, closer and closer though her arms were too small to reach back.

If it was cold that day, Lena can't remember. The whole world was within those arms, and when she left them the world was gone.

…

She manages to forget.

Paris is beautiful, but it could be the ugliest city on this and any other planet and still she would love it. In Paris, she is the American girl with the bad French accent and a name that means nothing.

In Paris, she has an apartment to herself and a boulangerie across the street that sells her croissants, and every morning she walks to class, a trail of flaky pastry crumbs in her wake. She learns how to solder a circuit board in the morning and what Baudelaire was writing about in the afternoon.

In Paris she has friends.

They meet between classes at a cafe near the park, and they laugh at Lena's terrible French accent but they don't switch to English for her and they don't make her feel bad when she can't keep up. They don't care what her name is, and so she manages to forget what it is.

She is the funny American girl, and when they leave for their afternoon classes, they say au revoir like they mean it, they kiss her cheeks like they aren't afraid of her, they hug her, each and every one of them, like they don't want anything from her.

And she forgets. For a while.

…

She isn't allowed to speak.

There are important people who must speak, and there is Lex, there is Lillian, and at her own father's funeral, Lena is not permitted to speak.

(The day before, the will was read. Half to Lex, half to Lena, and all of Lillian's fury to Lena, also. She would thank him, if he weren't dead.)

(She would sit in his chair until he found her in his office, as always. "What are you doing in here?" he would always ask, kiss her hair instead of waiting for an answer. "I wanted to thank you," she would say, "for the gift of Mom's eternal rage."

It wouldn't matter when this fantastic conversation took place. At seven or at twenty-seven, along with everything else Lionel had given her, that is what he had gifted her, too.)

The grave is still open, the casket inside doing nothing but sitting there, and everyone is gone. If she didn't have her own driver, she wonders how she might have made her way home, but then there are footsteps on the dry grass.

"Come on," Lex says. "Lolly, let's go home."

And at that, she breaks. She doesn't have a home to go to, not in Metropolis, not— the list is too long, and she feels untethered from the planet, and cries harder for it, and more still when Lex wraps his arms around her.

He holds her, tighter and tighter until it hurts and until she can feel herself again.

"You're going to be fine," he says, and she doesn't mention who he's leaving out of that statement.

…

She set the sky on fire.

Alone in her lab like a thief, she mixed one wrong enzyme and now everybody lives. Alone in her office after the sky stops burning, she wonders how long she has left before she is excluded from that reprieve.

While expecting the arrival of someone to kill her, Supergirl lands on her terrace.

It's not the same thing, she tells herself. It's not.

(It's not.

Aliens are no more of a threat to humans than humans are to themselves. Which is to say: everyone is dangerous, just different kinds of dangerous. But still, the voice in her ear says this is danger and she reminds herself that the only person who's ever actually tried to kill her is Lex.

The voice in her ear belongs to her would-be killer.)

"You stopped her," Supergirl, Kara, Supergirl says. "Lena—"

And she's close, so close, and the air is warmed by her, and then she's too, too close, gripping her in an embrace that is too, too strong, or maybe just strong enough.

She's never been touched by an alien before. Not that she knows of, and she doesn't know what to do, but the voice in her head doesn't whisper danger, danger, danger anymore. The voice is silent, gone, the sound of Kara— Supergirl's breathing the only thing left.

…

She finds Kara waiting in her office.

It's been days since Lena last saw her, and at the sight of her something aches, as it always does now, in a space where Lena cannot find the edges.

At the sound of her, feet clattering to a silence, Kara looks up, and that endless, amorphous space solidifies. She looks tired, more than tired, and Lena remembers she doesn't know why Kara has been absent for days, missing from Lena's life.

She could guess, but Lena doesn't dabble is speculation.

"I'm sorry I— I would have come sooner if I could."

The problem with Kara Danvers is that the knowledge Lena's being lied to doesn't stop her from believing Kara, and that aching, crystallized thing won't let her keep the distance.

"It's okay," she says instead of the many things she wishes to say instead.

But Kara doesn't look like it's okay, doesn't look like she believes Lena, bowed and broken on Lena’s couch, and that distance wittles right down until it’s gone, Lena curling her arms around Kara's shoulders.

And it's such a different sensation, to hug instead of to be hugged, and her arms feel awkward, muscles uncertain about how to bend her limbs correctly. Different, but— Kara's arms settle around her, fingers curling into the wool of Lena's sweater and knuckles pressed against her back, and Lena soaks in the warmth of the body in her arms, feels the flex of that strength it possesses, and it lets her believe.

"It will be," she says, more truthfully, not quite to the woman in her arms.

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOOK REVIEW: THE MISSING MUSEUM BY AMY KING Reviewed by Emma Bolden @ Los Angeles Review

BOOK REVIEW: THE MISSING MUSEUM BY AMY KING

Reviewed by Emma Bolden

The Missing Museum

Poems by Amy King

Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2016

$14.00; 114 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1939460080

In February 2012, the Russian feminist punk/performance art/protest group Pussy Riot staged an act of protest against the re-election of Vladimir Putin. Between services at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a Russian Orthodox church destroyed by Stalin and rebuilt in the 1990s, the women entered and walked up to the altar, jumping and jabbing their fists in the air. Filmed footage of the performance was included in the music video for their song, “Punk Prayer: Mother of God Drive Putin Away.” The song implores the Virgin Mary to “banish Putin” and “become a feminist, we pray thee.” Although Cathedral guards removed the group in less than a minute, three group members were arrested, charged with hooliganism, and sentenced to two years in prison.

After the American election of 2016, Pussy Riot warned Americans to prepare themselves: Trump’s presidency, they predicted, would resemble Putin’s in ways that many Americans might not even be able to imagine. In a December 2016 interview, Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova told New York Times reporter Jim Rutenberg that it was “important not to say to yourself, ‘Oh, it’s O.K.’ [ . . . ] in Russia, for the first year of when Vladimir Putin came to power, everybody was thinking that it will be O.K.” It isn’t safe, Tolokonnikova continued, to trust that America’s institutions will protect its citizens and their freedoms, as “a president has power to change institutions and a president moreover has power to change public perception of what is normal, which could lead to changing institutions.”

Pussy Riot’s work serves as a frame for Amy King’s riotous, rapturous, and radical fifth full-length collection, The Missing Museum. I mean “frame” quite literally: a passage from the poem that shares part of its title with the first section of the book, “PUSSY PUSSY SOCHI PUSSY PUTIN SOCHI QUEER QUEER PUSSY,” is printed on the back cover. “I HAVE A WITCH-CHURCH HAND,” the speaker declares in the poem, “& / PUSSIES RIOTING A PUTIN PRAYER / ON A NATION OF PEOPLE.” Just as Pussy Riot composed the clarion call of an iconoclastic culture countering Russian authoritarianism and repression, so too does Amy King’s work spur, capture, and curate the artifacts of a burgeoning resistance movement in the United States.

Also like Pussy Riot, King’s use of the term “pussy” serves as a shibboleth for revolutionary feminism, reclaiming a term used as a slur against women—and, as the 2016 release of Access Hollywood footage shows, one often linked linguistically to sexual assault and rape. Through reclamation, feminists empty the term of its misogynistic implications, empowering themselves by taking ownership of the language of the oppressor. Now, “pussy” has become a common part of the American vernacular, wielded by women fighting to preserve their fundamental rights to control their own bodies and speech. Likewise, Pussy Riot’s music carries great meaning for the American resistance and for the poems in this collection, which serve, in many ways, as a museum preserving the gathering motion of resistance.

Unlike many museums, King’s isn’t a collection of evidence of an unchanging monolithic culture. Instead, the book protests the very idea that any culture or subculture is, was, or ever will be stable, static, and homogeneous. King’s poetry sweeps through cultural references from surrealist painter Leonora Carrington to soul singer and activist Nina Simone to pop singer Lionel Richie. The sheer breadth of references in King’s work echoes the idea that no culture is singular or stationary. The disparate works—songs, paintings, poems, acts of civil disobedience—of all of these artists cross through the collection as separate but equally essential works and workers of culture. As King writes in “You Make the Culture,” “The words become librarians, custodians of people.” If any representation of a culture is to be accurate, she continues, it is to involve movement: “I will walk with the sharks of our pigments / [ . . . ] until we leave rooms that hold us apart.” Inclusivity, and the ability to envision all groups in terms of belonging, is essential, as lines near the end of the poem show: “Nothing comes from the center / that doesn’t break most everything apart.”

After all, culture is the product of changeable, mutable human beings who, King argues in the collection’s prologue, “Wake Before Dawn & Salt the Sea,” are more action than object: “Our limits may not be expandable, but before you say, / ‘Blood and sinew,’ remember you’re making a mistake. / We are not edges of limbs or the heart’s smarts only.” As such, a worthwhile life is a life beyond “noise,” beyond “dying full of money but no one will give a shit, rich asshole.” To be stationary, to live untroubled while following the American exhortation to gain money and power without examining the dangers this philosophy poses or the system purporting this philosophy, is anathema to progress. The poem ends with a couplet that brings to mind Herman Melville’s enjoinder at the end of “Art,” in which he calls for a fusion of opposites within the self and between the self and the heavens. “Be somebody,” King implores of us, “be one who wrestles and make love to the dark / that is your deepest part, the uselessness of love and art.” The idea that the most beautiful things we as human beings bring to the light—beauty, love, art—are utterly useless comes as a shock, especially as it also comes at the end of a gorgeously-wrought poem serving as the collection’s prologue. The location of these lines creates the same kind of shock as the location of Pussy Riot’s “Punk Prayer” in an Orthodox cathedral. Both performances don’t just shock: they shift. The juxtaposition of lyric and location creates a moment in which the mind bends, allowing disparate realities to coexist.

King calls upon the work of the Surrealists to illustrate this juxtaposition. In “And Then We Saw The Daughter of the Minotaur,” a poem named after a painting by Surrealist Leonora Carrington, King writes of the need to move beyond accepted meanings, “to grow branches / between worlds on the backs of nurtured equations.” She calls for us to “[s]ay another elsewhere. Open the broom, sick with sorceries.” In “Pussy Riot Rush Hour,” King speaks of a woman traveling the Lexington Avenue Line while “hitting / herself, buck up head heavy against / the number 5 train downtown.” She describes her “self-infliction” as “a cause / that brings us away from our senses.” Here, King references Arthur Rimbaud, who called for poets to transform themselves into “seers” through a “long, immense, and reasoned derangement of all the senses.”

King’s collection carries out Rimbaud’s call through the velocity of its juxtapositions, racing through shifts in voice, structure, theme, and tone, sometimes within the same poem. In “Understanding the Poem,” “this world is anything but a poem” —and then, in the next line, “This world is this, this world is poem, and I am unusual today, at least.” The frenetic movement of King’s work—from popular culture to high culture, from Georgia pines to New York streets, from all-caps alert to expertly-groomed almost-sonnets—recalls the cry of Baudelaire’s soul to travel “Anywhere, anywhere, as long as it be out of this world!” The speed and span of juxtapositions in the collection reveals what is missing from museums: movement, derangement, change.

By this dynamic derangement of our assumptions about culture, King’s museum reveals what culture really is: an ever-changing multiplicity of perspectives that cannot be carved into different, disparate wings. The narrative of culture as a series of singular, separate factions and philosophies leads to the violence of othering and violence against others. In “Perspective,” this moves beyond theory to a matter of actual life and death:

When I see two cops laughing

after one of them gets shot

because this is TV and one says

while putting pressure on the wound,

Haha, you’re going to be fine,

and the other says, I know, haha!,

as the ambulance arrives—

I know the men are white.

At the end of the poem, King asks us to wrestle with questions about this narrative, about the curation of our culture, essential for the survival of our nation and ourselves.

Who gets to see and who follows

what script? I ask my students.

Whose lines are these and by what hand

are they written?

In that 2016 New York Times interview, Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova herself echoed this idea: “‘You are always in danger of being shut down,’ she said. ‘But it’s not the end of the story because we are prepared to fight.’” With her work and words, King shows her readers how to join the fight.

Emma Bolden is the author of medi(t)ations (Noctuary Press 2016) and Maleficae (GenPop Books 2013). Her work has appeared in The Best American Poetry, The Pinch, and Prairie Schooner, among others. Her honors include a 2017 Creative Writing Fellowship from the NEA and the Barthelme Prize for Short Prose. She serves as Senior Reviews Editor for Tupelo Quarterly.

http://losangelesreview.org/book-review-missing-museum-amy-king/

0 notes

Quote

We live, understandably enough, with the sense of urgency; our clock, like Baudelaire's, has had the hands removed and bears the legend, "It is later than you think." But with us it is always a little too late for mind, yet never too late for honest stupidity; always a little too late for understanding, never too late for righteous, bewildered wrath; always too late for thought never too late for naive moralizing. We seem to like to condemn our finest but not our worst qualities by pitting them against the exigency of time.

Lionel Trilling, Reality in America (1946)

0 notes

Video

amy king

BOOK REVIEW: THE MISSING MUSEUM BY AMY KING

Reviewed by Emma Bolden

The Missing Museum

Poems by Amy King

Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2016

$14.00; 114 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1939460080

In February 2012, the Russian feminist punk/performance art/protest group Pussy Riot staged an act of protest against the re-election of Vladimir Putin. Between services at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a Russian Orthodox church destroyed by Stalin and rebuilt in the 1990s, the women entered and walked up to the altar, jumping and jabbing their fists in the air. Filmed footage of the performance was included in the music video for their song, “Punk Prayer: Mother of God Drive Putin Away.” The song implores the Virgin Mary to “banish Putin” and “become a feminist, we pray thee.” Although Cathedral guards removed the group in less than a minute, three group members were arrested, charged with hooliganism, and sentenced to two years in prison.

After the American election of 2016, Pussy Riot warned Americans to prepare themselves: Trump’s presidency, they predicted, would resemble Putin’s in ways that many Americans might not even be able to imagine. In a December 2016 interview, Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova told New York Times reporter Jim Rutenberg that it was “important not to say to yourself, ‘Oh, it’s O.K.’ [ . . . ] in Russia, for the first year of when Vladimir Putin came to power, everybody was thinking that it will be O.K.” It isn’t safe, Tolokonnikova continued, to trust that America’s institutions will protect its citizens and their freedoms, as “a president has power to change institutions and a president moreover has power to change public perception of what is normal, which could lead to changing institutions.”

Pussy Riot’s work serves as a frame for Amy King’s riotous, rapturous, and radical fifth full-length collection, The Missing Museum. I mean “frame” quite literally: a passage from the poem that shares part of its title with the first section of the book, “PUSSY PUSSY SOCHI PUSSY PUTIN SOCHI QUEER QUEER PUSSY,” is printed on the back cover. “I HAVE A WITCH-CHURCH HAND,” the speaker declares in the poem, “& / PUSSIES RIOTING A PUTIN PRAYER / ON A NATION OF PEOPLE.” Just as Pussy Riot composed the clarion call of an iconoclastic culture countering Russian authoritarianism and repression, so too does Amy King’s work spur, capture, and curate the artifacts of a burgeoning resistance movement in the United States.

Also like Pussy Riot, King’s use of the term “pussy” serves as a shibboleth for revolutionary feminism, reclaiming a term used as a slur against women—and, as the 2016 release of Access Hollywood footage shows, one often linked linguistically to sexual assault and rape. Through reclamation, feminists empty the term of its misogynistic implications, empowering themselves by taking ownership of the language of the oppressor. Now, “pussy” has become a common part of the American vernacular, wielded by women fighting to preserve their fundamental rights to control their own bodies and speech. Likewise, Pussy Riot’s music carries great meaning for the American resistance and for the poems in this collection, which serve, in many ways, as a museum preserving the gathering motion of resistance.

Unlike many museums, King’s isn’t a collection of evidence of an unchanging monolithic culture. Instead, the book protests the very idea that any culture or subculture is, was, or ever will be stable, static, and homogeneous. King’s poetry sweeps through cultural references from surrealist painter Leonora Carrington to soul singer and activist Nina Simone to pop singer Lionel Richie. The sheer breadth of references in King’s work echoes the idea that no culture is singular or stationary. The disparate works—songs, paintings, poems, acts of civil disobedience—of all of these artists cross through the collection as separate but equally essential works and workers of culture. As King writes in “You Make the Culture,” “The words become librarians, custodians of people.” If any representation of a culture is to be accurate, she continues, it is to involve movement: “I will walk with the sharks of our pigments / [ . . . ] until we leave rooms that hold us apart.” Inclusivity, and the ability to envision all groups in terms of belonging, is essential, as lines near the end of the poem show: “Nothing comes from the center / that doesn’t break most everything apart.”

After all, culture is the product of changeable, mutable human beings who, King argues in the collection’s prologue, “Wake Before Dawn & Salt the Sea,” are more action than object: “Our limits may not be expandable, but before you say, / ‘Blood and sinew,’ remember you’re making a mistake. / We are not edges of limbs or the heart’s smarts only.” As such, a worthwhile life is a life beyond “noise,” beyond “dying full of money but no one will give a shit, rich asshole.” To be stationary, to live untroubled while following the American exhortation to gain money and power without examining the dangers this philosophy poses or the system purporting this philosophy, is anathema to progress. The poem ends with a couplet that brings to mind Herman Melville’s enjoinder at the end of “Art,” in which he calls for a fusion of opposites within the self and between the self and the heavens. “Be somebody,” King implores of us, “be one who wrestles and make love to the dark / that is your deepest part, the uselessness of love and art.” The idea that the most beautiful things we as human beings bring to the light—beauty, love, art—are utterly useless comes as a shock, especially as it also comes at the end of a gorgeously-wrought poem serving as the collection’s prologue. The location of these lines creates the same kind of shock as the location of Pussy Riot’s “Punk Prayer” in an Orthodox cathedral. Both performances don’t just shock: they shift. The juxtaposition of lyric and location creates a moment in which the mind bends, allowing disparate realities to coexist.

King calls upon the work of the Surrealists to illustrate this juxtaposition. In “And Then We Saw The Daughter of the Minotaur,” a poem named after a painting by Surrealist Leonora Carrington, King writes of the need to move beyond accepted meanings, “to grow branches / between worlds on the backs of nurtured equations.” She calls for us to “[s]ay another elsewhere. Open the broom, sick with sorceries.” In “Pussy Riot Rush Hour,” King speaks of a woman traveling the Lexington Avenue Line while “hitting / herself, buck up head heavy against / the number 5 train downtown.” She describes her “self-infliction” as “a cause / that brings us away from our senses.” Here, King references Arthur Rimbaud, who called for poets to transform themselves into “seers” through a “long, immense, and reasoned derangement of all the senses.”

King’s collection carries out Rimbaud’s call through the velocity of its juxtapositions, racing through shifts in voice, structure, theme, and tone, sometimes within the same poem. In “Understanding the Poem,” “this world is anything but a poem” —and then, in the next line, “This world is this, this world is poem, and I am unusual today, at least.” The frenetic movement of King’s work—from popular culture to high culture, from Georgia pines to New York streets, from all-caps alert to expertly-groomed almost-sonnets—recalls the cry of Baudelaire’s soul to travel “Anywhere, anywhere, as long as it be out of this world!” The speed and span of juxtapositions in the collection reveals what is missing from museums: movement, derangement, change.

By this dynamic derangement of our assumptions about culture, King’s museum reveals what culture really is: an ever-changing multiplicity of perspectives that cannot be carved into different, disparate wings. The narrative of culture as a series of singular, separate factions and philosophies leads to the violence of othering and violence against others. In “Perspective,” this moves beyond theory to a matter of actual life and death:

When I see two cops laughing

after one of them gets shot

because this is TV and one says

while putting pressure on the wound,

Haha, you’re going to be fine,

and the other says, I know, haha!,

as the ambulance arrives—

I know the men are white.

At the end of the poem, King asks us to wrestle with questions about this narrative, about the curation of our culture, essential for the survival of our nation and ourselves.

Who gets to see and who follows

what script? I ask my students.

Whose lines are these and by what hand

are they written?

In that 2016 New York Times interview, Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova herself echoed this idea: “‘You are always in danger of being shut down,’ she said. ‘But it’s not the end of the story because we are prepared to fight.’” With her work and words, King shows her readers how to join the fight.

Emma Bolden is the author of medi(t)ations (Noctuary Press 2016) and Maleficae (GenPop Books 2013). Her work has appeared in The Best American Poetry, The Pinch, and Prairie Schooner, among others. Her honors include a 2017 Creative Writing Fellowship from the NEA and the Barthelme Prize for Short Prose. She serves as Senior Reviews Editor for Tupelo Quarterly.

http://losangelesreview.org/book-review-missing-museum-amy-king/

0 notes