#history of science

Text

I'd like to introduce you to LJS 57, a compendium of Astronomical text in Hebrew, written in Spain around 1391. It's an interesting combination of astronomy and astrology, and illustrates how the division between "science" and "not science" was not nearly so clear in the past as it is today. It has some fantastic illustrations of constellations!

🔗:

#medieval#manuscript#medieval manuscript#14th century#hebrew#astronomy#astrology#stars#constellations#illustrations#illuminations#diagrams#history of science#book history#rare books

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

So, just wanted to share that early modern pop-up astronomy books were a thing and they are absolutely glorious.

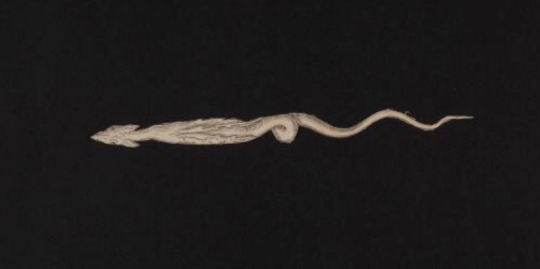

Here's a close-up of the little dragon-serpent guy, because he is especially magnificent.

#astronomy#early modern history#early modern period#dragon#astronomy book#pop up books#history of science#Leonhard Thurnheisser zum Thurn#astrolabium

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm too...skeptical of a person to vibe with much of the "witchcraft" adjacent spirituality that's popular nowadays

However, one of the most difficult things to understand about The Past is that for many of your ancestors, the distinction between "spiritual" and "mundane" phenomena did not exist.

and this does create problems for the idea that "science is for one set of questions, religion is for another" or at least the idea that "witchcraft" is a religion (exclusively). In The Past, philosophers speculated about the universe from the point of view that there were spiritual realities and that they weren't distinct from material realities. Before the modern idea of gravity, there was the idea that the four classical elements each had a particular nature, with earth being the heaviest and fire being the lightest. This also corresponded to a moral reality about the elements—the lighter elements were more "pure." (This is why in Dante's Inferno at the center of the Earth is Satan himself.) These people weren't assigning morals to substances in the way we now think of it. Their spiritual and moral realities were just "real" in the same way as the physical world.

People asked "From what we know of God, what can we hypothesize about the existence of extraterrestrial planets and beings, and what they are like?" And it's interesting to note that the belief in God didn't obstruct them from asking these questions; instead, it allowed them to ask these questions at a time when they didn't have naturalistic observations to go on.

But I'm getting off track—modern science is derived from things like alchemy and philosophy, and we are a bit biased here because we tend to see Aristotle and the like as precursors to "science," whereas when indigenous people maintain and pass down a collective body of naturalistic observations about their world, that's seen as some kind of cutesy pagan thing. Which is just racism.

In reality, ancient astronomers were also priests, medicine was practiced by shamans. They were people with knowledge that the average person did not possess. If there's a generic word for this type of person, it's "wise woman" or "wise man": the "three wise men" that are said to have visited Jesus were astronomers. The figures we see as "spiritual" often dealt primarily, and sometimes almost exclusively, with physical, natural phenomena. When they did deal with spiritual phenomena, it was for a lot of the same reasons that we do.

(Arguably, we have a worse understanding of some things, because we see everything in the physical world, including our own bodies, as unaffected by the meaning we assign them.)

What this means is that "witchcraft" can and should be to some extent "mundane" and evidence-based. But in my mind, "witchcraft" means possessing some kind of knowledge that is hands-on, practical, and not easily obtainable just by reading books or wikipedia, tempered by wisdom as a guide for when and how to apply it. It's also a social role; it suggests your knowledge makes you important to your community.

...

So I think an auto mechanic is technically some kind of witch.

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

▪︎ Lane's Pocket Terrestrial and Celestial Globe.

Date: 1811

Place of origin: London

Maker: Nathaniel Lane

#19th century#19th century art#history#art#history of art#history of Science#science#Geography#astronomy#globe#Terrestrial globe#celestial globe#Nathaniel Lane#1811

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The freedom to abandon one’s community, knowing one will be welcomed in faraway lands; the freedom to shift back and forth between social structures, depending on the time of year; the freedom to disobey authorities without consequence – all appear to have been simply assumed among our distant ancestors, even if most people find them barely conceivable today. Humans may not have begun their history in a state of primordial innocence, but they do appear to have begun it with a self-conscious aversion to being told what to do. If this is so, we can at least refine our initial question: the real puzzle is not when chiefs, or even kings and queens, first appeared, but rather when it was no longer possible simply to laugh them out of court.

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

#the dawn of everything#David Graeber#David Wengrow#archeology#prehistory#anthropology#history#upper paleolithic#paleolithic#human history#sociology#book recommendations#book quotes#nonfiction#readings#reading list#reading recommendations#book rec#cultural anthropology#history of science#inequality#anarchism#writings

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact: The pronunciation of American English is closer to the pronunciation in William Shakespeare's time (1564-1616) than in British English. Today's American accent is more closely related to what Shakespeare heard while he wrote. People generally assume that Shakespeare's English is related to British English, but in Early Modern English the letter "r" is still pronounced. During the 18th century the "r" was dropped from pronunciation when it was the last syllable of a word in southern British English. American English froze in how we pronounce letters, which is why we sound more like Shakespeare than British English.

#histoire#history#history in the making#history is awesome#history of science#history stuff#historyposting#today in history#history lesson#connecticut#history lover#william shakespeare

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

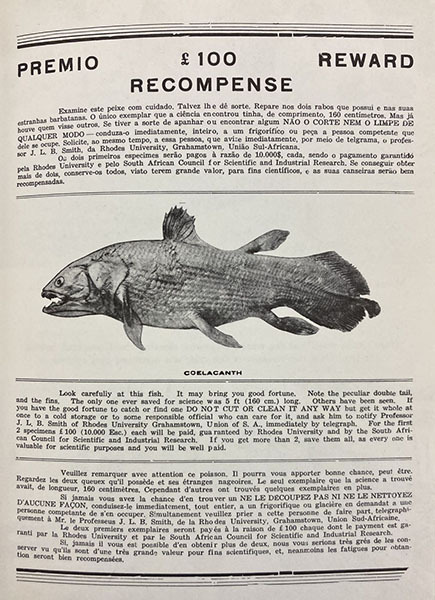

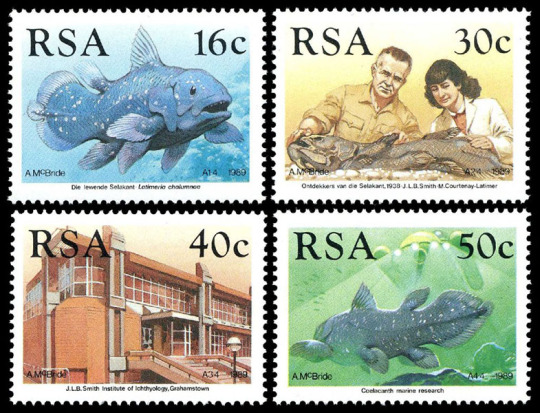

J.L.B. Smith – Scientist of the Day

James Leonard Brierley Smith, a South African ichthyologist usually referred to as J. L.B. Smith, was born Sep. 26, 1897.

read more...

#J.L.B. Smith#ichthyology#coelacanth#marine biology#histsci#histSTM#20th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

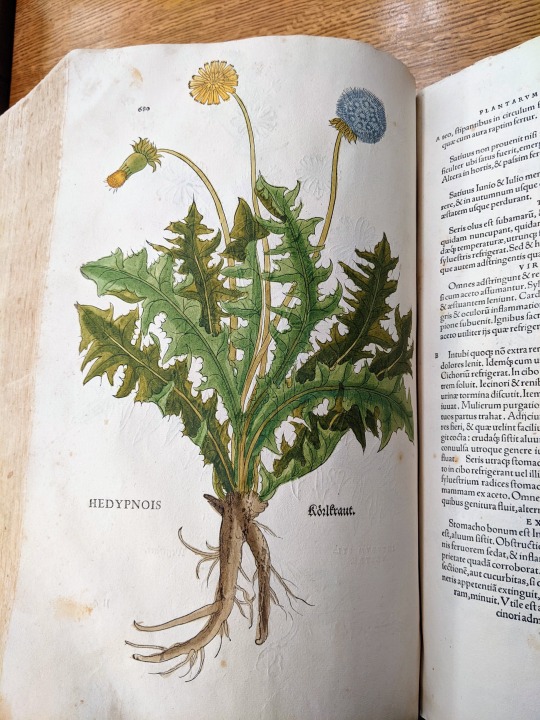

It's dandelion season here in Columbia, and thanks to a visitor to our reading room, we found a beautiful dandelion in our copy of Leonhart Fuchs' De Historia Stirpium (1542). Dandelions are native to Eurasia and may have been brought to North America for medicinal purposes by early colonizers. VAULT OVR QK41 .F7 1542

#dandelion#dandelions#rare books#history of science#scientific illustration#mizzou#special collections#libraries#university of missouri#bookhistory#history#books#illustration#nature illustration#botany#biology

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm giving a lecture on Jewish Paleontology (Jews in Paleontology, Paleontology that involves Judaism, the whole SheBang) today (the 1st) at 3pm EDT! Should be a fun time! Feel free to join! (It is today, it says past event because I had to postpone it)

295 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I had a nickel for every element on the periodic table that was named for a goblin from miners' folklore, I'd have two nickels. Which isn't a lot, but it's weird that it happened twice.

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

LJS 64 is a book of diagrams, many with moving parts, designed to accompany the work Theoricae novae planetarum by 15th-century Austrian Georg von Peurbach, who is considered one of the first modern astronomers. He was particularly interested in simplifying the Ptolemic system (which places the Earth in the center of the solar system). The diagrams in the book demonstrate increasingly complex planetary motion.

🔗:

LJS 64 was recently featured in #CoffeeWithACodex, you can watch the complete 30 minute video here:

#medieval#renaissance#manuscript#volvelles#diagram#diagrams#illustrations#astronomy#astrological#science#history of science#book history#rare books#16th century

887 notes

·

View notes

Text

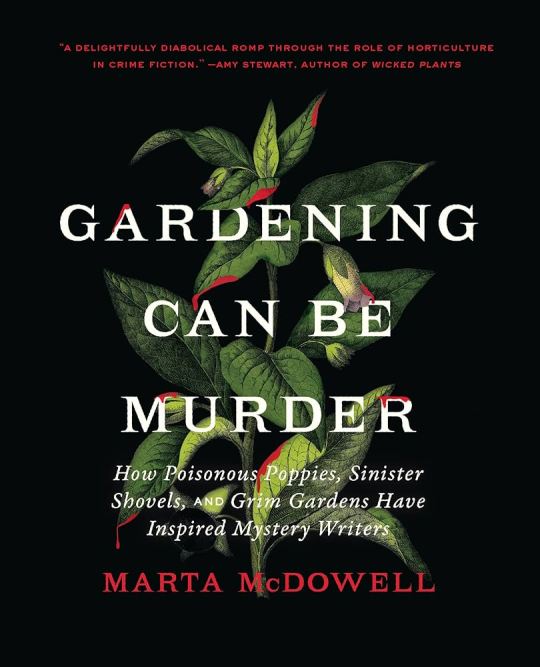

2024 Reading Log, pt 2

006. Gardening Can Be Murder by Marta McDowell. I honestly thought that this book was going to be about something else. With the subtitle “how poisonous plants, sinister shovels and grim gardens have inspired mystery writers”, I thought it was going to be about, you know, that. True crime themed to gardens, discussions of poisonous plants, that sort of thing. The book is actually about the mystery books that have gardening as a theme. And while the author’s dedication to not spoiling anything (seriously, anything, even 150 year old stories like The Moonstone or “Rappacini’s Daughter”) is admirable in its own way, this leaves the book feeling like endless buildup without any payoff. Big fans of murder mysteries might enjoy this—especially the last chapter, which interviews writers about their gardens—but I found it more boring than anything else, and finished it only because it was very short.

007. Antimony, Gold and Jupiter’s Wolf by Peter Wothers. This book is about how the elements got their names, and most of it deals with the early modern period, as alchemy transitioned to chemistry and then into the 19th century, when chemistry was a real science, but things like atomic theory were not yet understood. The book goes into fascinating detail, and has a lot of quotes from primary sources, as scientists then were just like scientists now, that is, opinionated and bickering with each other over their preferred explanations. And names! Many of the splits between elements and their symbols (like Na for sodium) are due to compromise attempts to appease two different factions with their preferred names. A book covering arcane minutia of history always has the risk of feeling like a slog, but this is a fast and fun read.

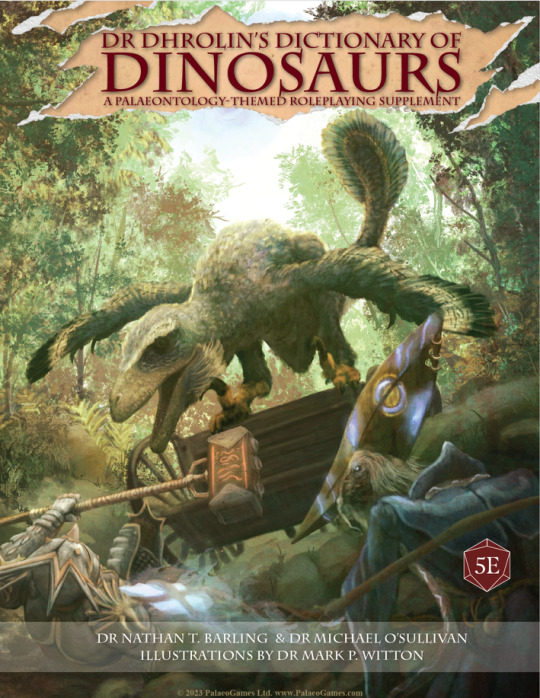

008. Doctor Dhrolin’s Dictionary of Dinosaurs by Nathan T Barling and Michael O’Sullivan, illustrations by Mark P Witton. This book is an odd concept, but one that I was immediately on board with—a D&D book written by paleontologists with the intention of bringing accurate and interesting stats for prehistoric reptiles to the game. The fact that it’s mostly illustrated by Mark Witton definitely clinched my backing that Kickstarter. And this book is a lot of fun. So much so, that I read it all in a single sitting. I don’t know how accurate the stats are (like, a Hatzegopteryx has a higher CR than titanosaurs or T. rexes), but they seem like they’d be fun in play, and the writing does a good job of combining fantasy fun with actual education. Even for someone not running a 5e game, the stuff on how to run animals as not killing machines, and the mutation tables, could be useful. There are multiple types of playable dinosaurs, all of which seem like they’d work well at the table and avoid typical stereotypes, and a lot of in-jokes and pop culture references (like the cursed staff of unspared expense, which looks like Hammond’s cane in the Jurassic Park movie).

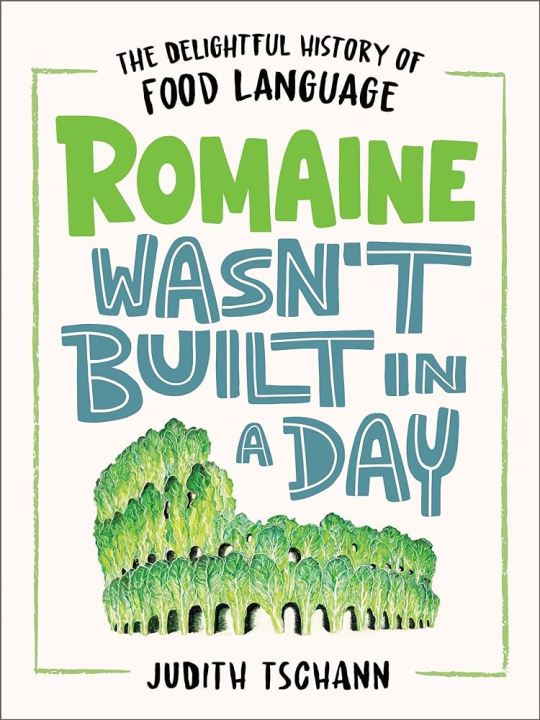

009. Romaine Wasn’t Built in a Day by Judith Tschann. I’m a sucker for books about etymology. And this one, on food etymology, is a pretty breezy read. I had fun with it, and it even busted some misconceptions that I had, etymologically speaking. Like, there’s no evidence that “bloody” as an explicative originated from “God’s blood”? Wild. Etymology books tend to be written in a sort of stream-of-consciousness style, where talking about one word may lead down a garden path to the next one. The book also has a couple of little matching quizzes, which is something I haven’t seen in a book since like the 90s.

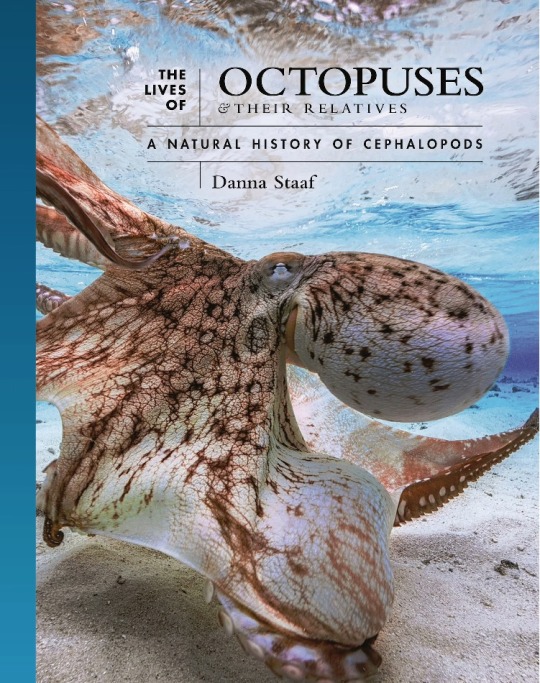

010. The Lives of Octopuses and their Relatives by Danna Staaf. I was previously a little disappointed in The Lives of Beetles, another book in this series, but I knew I liked Staaf, who wrote the excellent book Squid Empire about cephalopod evolution and paleontology. I’m pleased to report that this book is also excellent. Staaf takes the “lives” part seriously, and the book is arranged by ecology, looking at different marine habitats, the challenges that they pose to living things, and the cephalopods that live there. Cuttlefish get slightly short shrift in this book compared to squids and octopuses, but that’s about the biggest complaint I had. I like how the species profiles cover more obscure taxa, and information about the best studied (like Pacific giant octopus and Humboldt squid) is kept to the chapters.

#reading log#marine biology#cephalopods#etymology#food history#tabletop rpgs#dinosaurs#D&D 5e#chemistry#periodic table#history of science#mystery#horticulture

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

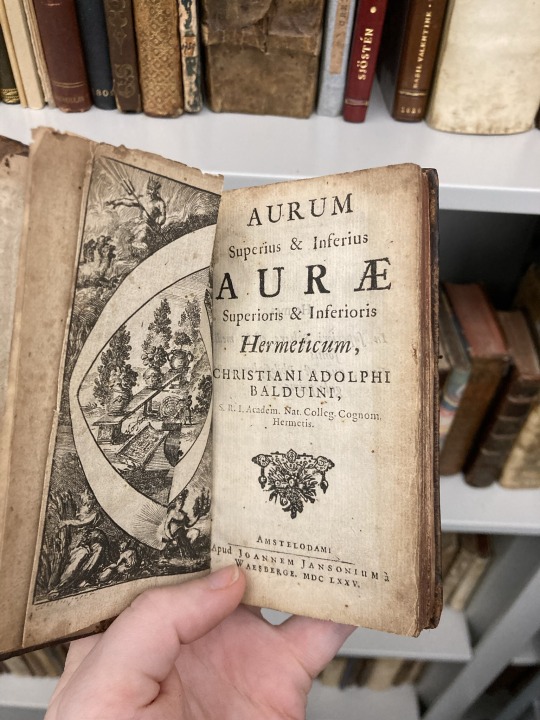

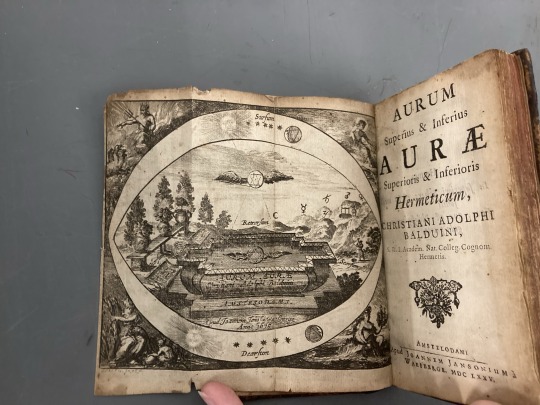

Aurum superius et inferius aurae superioris et inferioris hermeticum (1675) by Christiani Adolphi Balduini.

This is a second, slightly enlarged edition of Aurum Aurae, Vi Magnetismi (1674) and contains a folding frontispiece engraved by C. Dekker (1675) and two copperplates by C. Dekker.

#rare books#old books#frontispiece#engravings#17th century books#science#alchemy#history of science#books#pretty books#title page tuesday

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy #NationalUnicornDay!

De Monocerote (The Unicorn), from Conrad Gessner's Historiae animalium, 1551.

#unicorn#National Unicorn Day#animal holiday#mythical creatures#Conrad Gessner#Historiae Animalium#book plate#book illustration#lithograph#natural history art#scientific illustration#sciart#zoological illustration#history of zoology#history of science#European art#16th century art#animals in art

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

▪︎ Pocket compass and sundial.

Artist/Maker: Michael Butterfield (1635-1724)

Place of origin: Paris, France and England

Date: early 18th century

Medium: Engraved silver, engraved brass

#18th century#18th century art#18th century science#science#history of science#pocket compass#sundial#Michael Butterfield

323 notes

·

View notes