#decalogue

Text

the book of company, hymn 11.6.01 🍋🥦

[for @decaloguezine] ✨

#decalogue#sweet religion#citrinabeth#belizabeth brassica#citrina rocks#acoc#a crown of candy#dimension 20#d20#art

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catechism of the Catholic Church

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

1 I am the Lord your God: you shall not have strange Gods before me.

2 You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain.

3 Remember to keep holy the Lord's Day.

4 Honor your father and your mother.

5 You shall not kill.

6 You shall not commit adultery.

7 You shall not steal.

8 You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

9 You shall not covet your neighbor's wife.

10 You shall not covet your neighbor's goods.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decalogue 5

I’ve been chipping away at this “story” for three years now—it’s more a conceit that got out of hand, really, but ten years’ worth of regular fanfictional postings can send the conceptual car into some unreasonably esoteric cul-de-sacs. This one, as the title makes clear, has to do with ten commandments—not THE Ten Commandments, but one for each year of the Bering-and-Wells situation (I started this excursion on the tenth anniversary, intending to finish it soon after and wind up the ten, but...). Part 1 covered years one through five, with commandments as follows: one, meet at gunpoint; two, thou shalt not touch; three, suffer in silence; four, make mistakes; and five, thou shalt not hold grudges. Part 2 was year six: Thou shalt not damage. Part 3 dealt with year seven and instructed, “Thou shalt take nothing for granted.” Most recently, part 4 yielded year eight’s “Remember the anniversary,” which is always good advice, so here’s year nine, which via time’s-arrow shenanigans and bizarro chapter-math is part 5, being posted on the thirteenth anniversary.

Decalogue 5

Year 9: Calm down.

It would of course have been wise for Myka to have applied such a directive, spiritually, throughout most of her years with (and without) Helena. It would have been wise for her to have applied it throughout most of her interactions with Helena... and if anyone had asked her, she would have said she’d tried to do so. But apparently her efforts hadn’t met the universe’s expectations: such that by their ninth year, said universe saw fit to insist, insistently, that she work much, much harder at it.

That insistence came over time to manifest as an incessant tapping against her consciousness... naturally (or was it artificially? and was there a salient difference?) everything that happened served as a commentary on everything else that happened, for Myka would over the course of the year come to understand the heavy significance of a particular tapping sound.

Circumstances began to converge—though Myka didn’t realize they were converging, and that in itself ended up being salient—when she and Pete were driving home, late at night, from a retrieval that hadn’t mattered at all. Late at night, though: that mattered. Nearly midnight, in fact, which mattered most.

“Helena hasn’t called me yet,” she said. She hadn’t really intended to say it aloud, but there were only five minutes left in the day. And when Helena and Steve were away on a mission, Helena called Myka at some point during each and every day: a compromise, one designed to mitigate Myka’s urge to smother, at least as far as Helena’s health and safety were concerned. It wasn’t that Helena wouldn’t call, left to her own devices. But Myka was able, was allowed, to expect it. To rely on it.

Pete snorted. “Charlize Theron hasn’t called me yet, but you don’t see me checking my phone every ten seconds about it.”

Myka had given up trying to explain to Pete what a non sequitur was. Instead, she asked, “Why would Charlize Theron call you?”

“Why wouldn’t she? It’s like you’ve never looked at me. But also: get it?”

“I think there’s a significant difference with regard to roles in lives.”

“Only because Charlize hasn’t got the memo on her destiny with me. Don’t be acting snooty just because you and H.G. got all the memos. ‘Agent Bering,’” he pronounced, high-voiced, “‘we’re forever destined to meet at gunpoint.’”

Another thing she’d given up: getting offended and telling him his Helena impression was atrocious. Instead, she said, “I really wish Claudia hadn’t told you about that.” She did wish it. But she knew it was—

“Pfft. Water, bridge, under,” Pete said, reading her mind. “I really wish you’d quit checking your phone every ten seconds. You’re making me nervous.”

“You check your phone constantly!”

“But not for a reason.”

“I just want to know why she hasn’t called yet,” Myka said, hearing herself sound not a little desperate, aggravated that she hadn’t scrubbed—apparently couldn’t scrub—all that evidence from her voice.

Pete didn’t seem to care. “Maybe she’ll tell you when she calls. Or hey, I just realized, phones work both ways.”

That wasn’t the deal, but with three minutes—no, now two—to go, Myka gave in and called. Straight to voicemail. She then went entirely in-for-a-penny on it and called Steve, who picked up quickly, only to say, “Can’t talk; call you back when—”

And then the phone went dead.

Myka’s throat wasn’t really closing in panic, was it? It couldn’t have been. Through the obviously nonexistent clutching choke, she said to Pete, “I called Helena and she didn’t answer and then I called Steve and he said he couldn’t talk and he’d call me back but the line went dead. What do I do now?” She wasn’t really looking for advice, but she had to ask to at least try to force her heart back down.

He didn’t turn his eyes from the road. “Here’s an idea: calm down.”

“I’m very calm,” Myka lied.

Now he did look at her, with an eyeroll of oh please. “Another idea: quit lying.”

“As ideas go, you should quit Steving. And answer my question!”

“I don’t remember the question.”

Myka exhaled with purpose. “What do I do now?”

“Finally an easy one. Wait till Steve calls you back.”

She didn’t have much choice.

Myka had always taken pride in being practiced at simulating calm; that kind of fakery was practically part of an agent’s job description. But she was being forced to learn (and resisting being forced to learn) that such simulation wasn’t enough to resolve every situation... or, more broadly, that appearances unfortunately weren’t reality.

Not until nearly two in the morning—after Myka had showered, changed into her pajamas, pretended to read some pages of Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time (she and Helena were mutually bookclubbing that), and finally given in to doomscrolling news, because at least that didn’t require an attention span—did Steve call and say, “Everything’s fine. She’s about to call you, but I told you I’d call you back, so I am.”

Helena opened her own call by saying, “Via miscalculation, I broke our deal. I know it, and I apologize.”

“Miscalculations happen,” Myka said, because of course they did. Then she said, “I’m too rigid,” because of course she was. Probably.

“I’ll make it up to you,” Helena said, with a fervent affection.

“By calling twice tomorrow?” Myka asked, her own affection rich.

“It’s already tomorrow, and I’ll be home then. Or now: it’s today.”

“You make no sense.”

“Be that as it may, and it may, but: how was your appointment with the physician yesterday?”

Myka had figured that was going to be on the agenda, whenever this call happened. Earlier in the day, she’d been happy enough to put off talking to Helena about the results of her physical; now that wish for postponement returned full force. “Better than your retrieval, I bet,” she hedged, hoping that Helena might just... drop it. Drop it and regale Myka with retrieval exploits.

That was a vain hope, of course: first, Helena had an uncanny ear for reluctance and would seize it and shake it till it yielded a why; second, a full physical, with its palpations, percussions, auscultations, and analyses of the living breathing body, was jam-packed with the sort of trackable data Helena found endlessly enthralling.

“Steve and I are fine,” Helena said, of course declining to elaborate on the mission, of course dashing Myka’s hopes. “Are you?”

That was without question a shake in search of a why. “Do I look unhealthy to you?” she countered.

“I can’t see you. This isn’t a video call.”

“If the answer’s yes, just say it.”

“The answer is that to me, you look reasonably healthy. I’ve certainly seen you look far less healthy.”

“You have?” Because Myka had hardly been sick at all, these past several—

“I suspect you’d rather I didn’t talk about that.”

“I would?”

A breath. Then: “Boone.”

Stupid mistake, Myka chastised herself. You should have understood immediately. Should have understood—which still often took the place of “did understand”—even now, after so much time. She breathed out heavily, trying for that elusive calm. “Okay. Yes.” They had talked, at first poorly, about the cancer. Talked, continually poorly, about Pete’s role in making it go away. Talked about—argued about—who had the right to, who deserved to, save whom. “I can’t change the fact that he did,” Myka had said.

To which Helena had said, not enraged but resigned, “I can’t change the fact that I resent his doing what I couldn’t.”

“Because you didn’t know,” Myka had tried.

“For which I blame myself,” Helena had gloomed in response.

“Blame both of us,” Myka had tossed into the breach. Before, she would have said “you should,” but she’d seen how time could stretch the boundaries of fault, of responsibility, for so many acts. In this case, she’d made sure to push those boundaries herself. On purpose, hard and away. “Blame the Warehouse. Blame everybody everywhere. There’s so much blame to go around...”

Now, Myka was at least able to follow up with, “I can honestly say I’m glad I looked worse then. Because comparatively, this is not a big deal.”

It wasn’t. At any rate, it didn’t seem to be. Her primary care doctor, whom Myka trusted because he’d steered her through the non-Warehouse parts of the cancer without making any of it weird, had been factual: “Most everything looks fine, but your systolic blood pressure falls in a range we refer to as ‘elevated.’” He then perked up, like he’d been itching for an opportunity to have something to do, in these years she’d been untumored: “In younger people like you, this generally results from lifestyle issues, so I’ll link you to some articles in the portal outlining changes, steps to take so you don’t develop dangerous hypertension.” Myka had thought he’d sounded overly enthusiastic on the word “dangerous”... but she’d hoped that was a figment of her hyperactive imagination.

“And yet you’re telling it to me,” Helena said, after Myka explained what he’d said, trying to downplay it, omitting in particular his use of the word “dangerous.” Trying and failing to downplay it, apparently, despite the omission, because Helena followed up with, “And you sound a trifle agitated, most likely a bit about my failure to call as I should have... also a bit about the diagnosis itself. But perhaps something else as well?”

She was discerning, Helena was, reading Myka not like a cipher, rendering a single message, but like a novel, allowing for varying interpretations. What could Myka have done but reward her by telling the truth? “He wanted to know about family history,” she said. “I had to call my parents. Well. My mom’s blood pressure’s fine. I mean my dad.”

“Ah. A still-fraught proposition.”

“A useless proposition,” Myka said. “I got myself all geared up for it, but he wouldn’t tell me much of anything. Like I was trying to pry military secrets out of him.”

“You two do often seem to be at war.” And Helena added, as if she’d seen Myka’s immediate nod of agreement, “In keeping with that, perhaps you should try another sortie.”

“I’ll need to gear up again. Which I guess is in keeping too.” She harrumphed. “Won’t be good for my blood pressure, I bet.”

“Nor is being awake at this hour of the morning. We should end this call, and you should sleep.”

“But you’re on this call, and so am I. I don’t want to end it.”

“Nor do I, but you should sleep.”

“So should you,” Myka said.

“Lost cause. But we’ll both sleep better tomorrow night. No, tonight. It’s today.”

“You make no sense,” Myka accused again, but drowsily.

Helena rewarded her with a low chuckle. “And you make nothing but sense?”

“You wouldn’t know,” Myka said...

They continued on in that vein that for some time, until they finally agreed to end the call at a three-two-one same moment. Myka felt grateful, as she often did, for the way in which her life with Helena gave her access to some very typical experiences, ones that she probably wouldn’t have appreciated if she’d had them as a teenager. As an adult was better. As an adult with Helena was better still.

But just as Myka was about to slip into sleep, her mind began to race: she realized that she hadn’t asked Helena again about the retrieval, which had to have been more than a little fraught, and while she knew she wasn’t supposed to smother, she berated herself for what must have seemed like a total absence of real concern.

Thus when Helena and Steve arrived home, met by the cadre of Myka, Pete, and Claudia, the first thing Myka said, with a carefully calibrated mix of casual interest and earnest apology, was “I should have asked you before: what was the artifact, anyway?”

Helena didn’t say anything, but she glanced at Steve.

“You... what?” he said. Their imperfect communication—but communication all the same—reminded Myka of herself and Pete. What they’d had before they got it all wrong... what they were ever closer to fully getting back.

Helena shrugged, the very picture of resignation. “Go ahead.”

“It’s Nikolai Korotkoff’s sphygmomanometer—his Riva-Rocci cuff, they called it in his day. He’s the guy who discovered the sounds doctors listen for when they’re taking your—”

Myka’s knee-jerk response, she had to admit, was not ideal: exasperated, she interrupted, “This was about blood pressure? You’re kidding. You’re actually kidding.”

Steve turned to Helena, and while he wasn’t exactly panicked, he was clearly unsettled. “I want to tell her I am. I really want to. I feel like it would make your life easier if I do.”

Helena shrugged again. “Well. ‘Easier.’ Sorting out life’s relative ease, moment on moment, is a tricky business.”

“Is that a dig?” Myka snapped. “Why didn’t you say something last night? Or no, I mean this morning, because it wasn’t last night, which doesn’t matter now, but...”— she glanced at Helena, in a little apology for the snap—“...did. Look, if this thing lowers blood pressure, wrap it around my arm right now.”

That got her an eyebrow. “As someone tends to intone: not for personal gain.”

“Wouldn’t it be personal loss here though?” Claudia asked, with a surprising absence of snark.

That made Myka laugh, and she applauded, a triple-clap for emphasis. “See, this is what the Warehouse needs: a Caretaker who knows a loophole when she sees one.”

Claudia’s jaw dropped. “Who are you? The Myka I know and mostly love but am also driven nuts by because she’s such a rule snob hates loopholes.”

Obviously Myka was going to have to rethink her relationship with rules, if only to get some benefit from... something. “You know what? I’m just going to say—to postulate—that the Warehouse owes me one. Or several. I think it owes me several.”

Helena said, “Keeping score with the Warehouse is the very definition of a fool’s game.” That was her you are overreacting voice, rarely deployed except for when they were in Colorado. “But more importantly, that isn’t the cuff’s effect. It matters not at all to the one being measured, but rather to the measurer, in whom it increases sensitivity to, and the ability to interpret, diagnostically informative bodily processes. Hence our difficulty persuading the doctor who relied upon it to... relinquish it.”

Myka, reacting poorly both to the news and to the tone in which it was delivered, said, “It absolutely figures that the Warehouse would ping out something completely useless at a time like this.”

“Ping out?” Claudia asked. “Do we say that now?”

“I will say what I want. Stupid artifact,” Myka muttered.

Pete and Steve had been notably silent during all this. “Um,” Steve now said. “I feel like something’s out of proportion here, for reasons I’m not getting.”

Pete, apparently similarly confused, said, “Since when are you weird about blood pressure? Used to be anything about H.G. was your trigger, but now mostly it’s anything you think triggers her. So what gives?”

Myka was tempted to let him go hard on painful nostalgia, just to avoid having to talk about this ridiculous medical situation. But Helena gave her a look, one that said both “your reaction is out of proportion” and “you can’t hide this forever and certainly not if this is your response to related stimuli,” and even though Myka would have much preferred to hide it forever and was pretty sure she could if she worked hard enough, regardless of stimuli, she had to acknowledge that the whole thing was about what could stay hidden but would probably have adverse consequences if it did. So she grumped out, “My blood pressure. Is elevated. It’s a term of art,” she added, to try to forestall—

“Wow. That’s a biggie,” Pete said.

Oh well on the forestalling. “No it isn’t,” she told him.

“Except it is.”

“Except it isn’t. This is just a preliminary-warning type of thing.”

“A ping!” Claudia shouted. “Ping out!”

Steve said, “You sound a little too enthusiastic about that.”

“Kind of like my doctor,” Myka said, “who started going on about ‘lifestyle issues.’ I would like to state for the record that I do not have ‘lifestyle issues.’”

“Except for isn’t stress a thing? Working here’s a big part of your lifestyle,” Claudia pointed out, unhelpfully.

“And... you know,” Pete said. He nodded toward Helena, who spread her arms in an angelic “who, me?” gesture.

“‘Lifestyle’ is a stupid word,” Myka grumbled. “So I guess I’ll quit my job and break up with Helena, so I can live to a ripe old age and be broke and miserable. Excellent ideas. Thanks for the help.”

Steve—being his wise, confrontation-avoidant self—said, “I think I’ll just take this little artifact to the Warehouse so it can settle in.”

That had the unfortunate effect of reminding Myka of the artifact’s identity. “Did we all get whammied a long time ago with something that makes everything that happens in our lives rhyme in the most annoying way possible?” she asked. “Or was it just me?”

“I think it’s more repetition than rhyme,” Steve said, though in an I don’t want to be implicated in this way.

“Repetition with variation, however,” Helena said, and Myka wanted to be able to want to smack her.

“Right,” Steve said. “Would that be reprise? Maybe? Or am I thinking of something else?”

“None of this is lowering my blood pressure,” Myka informed them. Pointlessly.

Steve, to his credit, hotfooted it out of the situation, but Pete said, “You should look into stuff that would.”

“ON IT!!” was Claudia’s response.

Myka tried to head off whatever that was going to be with, “I’m supposed to check the online portal for links to what the doctor rec—”

“Links?!?” Claudia enthused. “I got all the links! Let’s run through some together!”

“Let’s not,” Myka said. Pointless again.

“Here’s the first one: ‘Lose extra pounds.’”

“She’s a pretty skinny drink of water,” Pete said. “Not much extra.”

“I guess,” Claudia said, sounding disappointed. “Next one: exercise regularly.”

Helena tilted her head a bit and said, “The regularity of her exercise is indisputable.”

“Come on,” Myka said. “I try really hard not to wake you up when I leave for my run.”

“I was not referring to your run.”

Claudia’s face pinked, and she said a quick, “Okay, okay! Moving on! Next really good idea: Eat fewer processed foods.”

That was patently ridiculous. “When was the last time I ate a processed food?” Myka asked.

“When I made bean dip in the food processor,” Pete said.

Myka sighed. “Look, this isn’t helping.”

Claudia nodded, despondent. “Yeah, you’re also supposed to quit smoking.”

“Like I said,” Myka agreed.

“But wait, here we go,” Claudia said, perking up, “like I said: reduce stress! And there’s a whole list!”

Myka waited for enlightenment.

For once, Claudia didn’t seem inclined to read aloud; in fact, she perked back down. “These are just... tips. Life-hacky,” she said, frowning. “How’s ‘plan your day’ supposed to do anything? And this one totally contradicts it: ‘Don’t experience future pain.’ Aren’t plans all about future pain?”

“Myka’s sure are,” Pete said. “So she’s doing everything right and wrong?”

“This is not a surprise,” Myka said.

“Maybe what’s next is simpler,” Claudia said. “Like, philosophically: ‘Make time to do the things you enjoy.’”

At that one, Pete leered, Myka groaned, and Helena objected, “I am not ‘things.’”

“I should’ve seen how that would go,” Claudia said, managing to refrain from turning red this time. “Okay, but this last one’s for all of us, except Steve, king of zen: practice gratitude.”

“Huh,” Pete said. “You know, I could probably stand to work on that.”

“I as well,” Helena agreed.

They all looked at Myka. “Fine,” she said. “I could too. In that spirit, thank you, Claudia, for caring enough about my blood pressure to find at least one thing that might lower it.”

“Score! And thank you for understanding how helpful I am.”

“Steve might not approve of your mixing gloating and gratitude,” Helena told her.

“No, no, I’m grateful for the gloating: it means we’re done,” Myka said.

Claudia said, “The internet’s a big place. I could find more!”

“Let’s end on success,” Myka said. “For everybody.”

She didn’t actually do very much practicing over the next while, not until she one evening received a surprise call from her father, right before she was ready to head upstairs to bed. She was tired—tempted to fend him off with “I’ll call you back tomorrow”—but it was a ready-made, if challenging, opportunity to practice. So she said, “Hi, Dad. Are you okay?”

He said an expectedly brusque “fine,” but then: “So, about what you were... asking about. The other day. I don’t like to talk about this kind of thing.”

Myka couldn’t quite hold back a dry “Really.”

“Don’t get smart with me,” he said, but with far less snap than he would have in the past. “Sorry. Look. Your... wife. Convinced me I should be a little more up front.”

“She... okay.” That presented a truckload of issues to process—and, she had to admit, to be grateful for.

First, the word “wife.”

That was new, as a word that applied—newly, quietly, it applied.

“I don’t want a wedding wedding,” Myka had said to Helena, once they’d got down to talking about the actual logistics. She knew it was likely to be a problematic position: knew and felt a powerful anxiety rise as she articulated it.

Helena had said, “Claudia does, and—”

“I know,” Myka began, her rebuttal at the ready, “but—”

“And,” Helena had interrupted. “Yet. While we owe her a great deal, that does not include dominion over how we enter into a legal union. And given all I’ve come to understand about modern weddings, I agree with you.”

Thus small it was, with Steve and Claudia—who continued to insist that she was, in fact, the flower ninja—their only witnesses.

Small, yet legal. About which Helena had evinced something very close to wonder: “A binding contract,” she had said, after words were pronounced and papers signed, as if the idea had just struck her.

“You’re the one who proposed,” Myka had reminded her, floating, light; she was in a bubble of something like wonder herself.

“I beg to differ,” Helena reminded back.

“The one who intended to propose. I have to believe you knew about that binding-contract endpoint of the proposal process.” That they could be these people. These word-trading, contractually bound, wonderstruck people.

“Of the proposal process,” Helena agreed. “Endpoint. Yes. But otherwise: beginning point.”

She’d said that last part quietly. But in the silence that followed, it swelled to a clarion.

Steve cupped his hands, as if to have and hold a bit of the air in which the words resonated.

“And here I was worried this—” Claudia had said, gesturing around the small conference room, which they would soon need to vacate for whoever was solemnifying next, “wouldn’t be enough.”

“Enough for what, darling?” Helena asked, though Myka was pretty sure they all knew the answer.

Now Claudia gestured at the two of them. “This.”

A decent enough word for it all, as words went.

Word-wise, and more salient to the present phone call, “wife” was new as a syllable her father would willingly pronounce of someone who was Myka’s. So: gratitude. There was also the matter of Helena having “convinced” her father of anything, although Myka was really unsure about where to place any appreciation for that. Further... well, no, that about covered it.

Her father then said, “I told you numbers. Befores, afters, but not what I did to move them.” He paused, and Myka had no trouble picturing his facial reluctance at having utter whatever might come next. What did come next: “Meditation.”

Not a word she’d ever expected to hear him utter—on a par with “wife” in its new application.

“Your mother makes me,” he said. “Thirty minutes a day, strictly enforced. You could try it.”

“Could,” he’d said, not “should.”

She knew she ought to have appreciated the call for what it was: seemingly sincere, part of an overall positive trend. But instead she worked herself up to offense, marching upstairs to find Helena—brushing her hair, innocent of any intent—and demanding, “You called my dad?” Petulant. An uptight whine. Definitely not her finest hour.

“I did not,” Helena said, not pausing her strokes for even a millisecond. “He called me.”

“He did?” So she’d climbed up to offense for no reason. The climb back down involved an awkward reset of her face and her breathing, but she did it, ending on a cringed, “Sorry.”

“He wanted to know if you were well,” Helena said, still conducting the stroke, stroke, stroke. “This was after he called your sister and asked her the same question.”

“He told you that?”

“No. Your sister did. When she called me to warn me that your father would be calling me, because she had told him she had no information on the point but that I most likely would. I asked her if she wanted me to tell her anything about said point, and she said no, that she would get it from your mother after your father told her what he found out from me.” Now she stopped the hair show and turned in Myka’s direction, brandishing the brush. “Your relations seem to take comfort in communication that is as indirect as possible.”

“I can’t even begin to argue with that. I sort of hate that everybody in my family—but especially my father—likes you more than they like me. But obviously I’m grateful for it too. It’s a slow-motion relief.”

“If your father’s concern for your health is any evidence, he likes you a great deal. I’ve never heard him inquire about my health.”

“Then again, maybe he doesn’t like you,” Myka said. “He thinks it’s your wifely duty to force me to meditate.”

“Coercion seems antithetical. And yet I do have every intention of fulfilling my wifely duties, including such new ones as arise—including this one. Given that it... has?”

“I guess it has. And I appreciate the intention. It’s important. Required, even. I honestly have a hard time believing this particular one’s going to have any tangible effect on the future, but I appreciate it.”

“Well, the future. What did Claudia say? ‘Don’t experience future pain.’ You should experience future effects—even pain, if necessary—when they happen. Not before.” Helena turned back to the mirror. She set the brush down and watched herself breathe in and out, very deliberately.

“Are we still talking about me?” Myka asked.

“I confess I’ve had to put effort into... braking trepidatious anticipation. With regard to effects.”

“Effects?”

“I can, for example, report that my blood pressure is fine.”

“Of course it is,” Myka groused, because of course it was.

Helena ignored that. “Fine for now, that is, which I know because Dr. Calder keeps a close eye. As part of her unplanned, yet obviously necessary, case study of the long-term effects of the Bronze, which she records as I... experience them.”

Myka felt her pulse speed at the thought. Not helpful.

Nor was the overall fact that the future, whatever pain it would or wouldn’t deliver, was unknowable.

“I try—often unsuccessfully, but more successfully with the passage of time—to remain securely in the present moment,” Helena went on. “Steve’s a great help.”

“Pete wouldn’t be,” Myka said immediately.

Helena turned fully around to face Myka; she leaned forward and said, “Wouldn’t he?

“Of course not,” Myka said, because the idea of Pete being helpful in some mindful pursuit of present-ness? Helpful like Steve would be? Preposterous.

“I believe you’re mistaken. Pete has many habits that vex every one of us, but you of all people should know that he does not fret. Certainly not about the future.”

Myka had to think that out for a minute, then a minute more. “You’re... right,” she said. “If something’s unknowable, he doesn’t try to know it. He forgets about it and reads a comic book.”

“A lesson for the both of us?”

“I don’t like comic books,” Myka said. “And neither do you.” But formulating this basic fact about her partner sparked Myka to think of her childhood, the way she would turn to a book in order to soothe herself, so as to simultaneously leave and fully inhabit as many present moments as possible... to Helena, she admitted, “It is a lesson. I used to be able to... lose myself. More. Better.”

A very small smile ghosted its way onto Helena’s face. “You lose yourself quite well.”

That was welcome, if (still, even now, a bit) embarrassing. “Thank you? But for the purposes of peace, maybe not ideal.”

“Well then, I suppose I’ll have to force you to meditate,” Helena said, and was that enthusiasm in her voice?

“Now?”

“No time like the present.”

Myka allowed herself to be manipulated toward the bed, then to be situated there cross-legged, even as she complained, “It seems like it’s going to take up a lot of time. Like the present. Thirty minutes a day, my dad said, but wasn’t one of Claudia’s tips about making time to do things I enjoy?”

“You just now rejected that,” Helena said. She put out the light and joined Myka on the bed, facing her, sitting similarly cross-legged.

“You’re just lucky ‘Things’ isn’t your new nickname. But come on, when you think about it, half an hour’s half an hour. Wouldn’t it just be stealing time from, you know, us?”

“Stealing present time—minimal present time—yes. But to increase the likelihood of maximal total time. For, you know, us,” she concluded.

It was a low blow; Helena knew how susceptible Myka was to having her own speech patterns mimicked by that voice. Nevertheless, she tried, “Didn’t you just say there’s no time like the present?”

“I did, and I was correct. Now focus.”

“Fine.” She closed her eyes. Then she cracked one open. “On what?”

Helena gave that some consideration. “At the risk of adding insult to injury, we might try Korotkoff sounds. I’ve been thinking on them since encountering Mr. Korotkoff’s instrument. We didn’t know them in my day... we could have produced them, used them for diagnoses, at any time. Yet to us, in our ignorance, blood moved ever silent.”

“My ignorance too. I’ve had my blood pressure taken a million times—and there’ll be a million more, and now more often—but I don’t know how it works. Tell me.”

“One imposes pressure by inflating the cuff around the arm, then one releases it, slowly, and listens. Silence at first, then five distinct phases of sounds, telling sounds, emerge as blood begins again to flow. The phases, the sounds. The same in all bodies. Yours. Mine. Everyone’s. Five. In succession.”

Her voice was slow. Lulling. This might not be meditation, but it was an easing. “Tell them to me,” Myka said. She closed her eyes again, imagining a wrapping, enveloping density, an inflating push of an determined cuff... yet even as she did so, a tendril of unease slipped its way in, an instinctive pre-flinch of discomfiture at what the release of pressure might reveal. She reheard “you lose yourself quite well”—felt the reflexive, nervous rise of self-consciousness—but she pressed against it, willing it down, down and away.

“In phase one,” Helena began, “the blood signals its return with clear taps, low but clear, knocks of announcement.”

Myka reached for the lull again, working to hear the silk-low voice both for itself (to be here) and for what it gave (to be elsewhere).

Helena thwarted her for a moment, becoming less hypnotist than lecturer as she said, “The pressure at which phase one occurs is the top number, that troublesome number of yours.”

Eyes still closed, Myka reached her hands out, feeling for Helena’s body, reaching her arms, and at the contact Helena seemed to understand. “In phase two,” she said, slow again, “the knocking softens, joined by a new sound, a swishing, soft, long, the blood taking its time, finding its way...”

Myka let her hands move, just a little, wayfinding.

“Phase three,” Helena said, with a small hitching throat-clear. “Here the knock returns, insistent now, the blood knowing its way, impatient to resume its course, pushing itself to phase four: an abrupt muffling, as if reassembling for a final push of sound.” Her hands now met Myka’s body, grasping her arms, tightening as she said, “But no, no final push, for phase five is the disappearance of all sound, the reestablishment of what the doctors of my day knew only as unrevealing silence. Yet not so unrevealing after all: that restoration is the diastolic pressure, the lower number, completing the diagnosis, culminating the story of how the blood speaks as it relearns to move: sound to less sound to more sound to no sound.”

That repetition of “sound”... it rang in Myka’s head. Sound, sound, sound...

She opened her eyes. Her hands were at Helena’s waist, and Helena’s hands had moved to her shoulders; now they were locked in the pose, statues waiting for a spell-break.

Myka willed herself not to move her hands as she said, “I didn’t meditate.”

Helena wasn’t moving either, but it seemed to be taking just as much effort. “I’m grateful,” she said.

“Are you calm?” Myka asked.

“Not at all.”

“Good.”

But later, later, in the still: yes. Calm. No sound.

TBC

#bering and wells#Warehouse 13#fanfic#Decalogue#part 5#I very nearly didn't finish this part in time#and it's less cohesive than I'd prefer#but it's yet another mark of time#my personal observation of occasion#apologies for the obsessive focus on the sounds#but they are quite striking#(no pun intended)#and honestly I think there's a sad lack of awareness#of how bodies are medically understood#such discoveries#and their revelations

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Michael Shermer

Published: Aug 9, 2023

There is arguably no better known set of moral precepts than the Ten Commandments. As an exercise in moral casuistry, in this essay, excerpted from my chapter on religion in my 2015 book The Moral Arc, let’s consider them again in the context of how far the moral arc has bent since they were decreed over three millennia ago. (The Ten Commandments are stated in two books of the Old Testament, Exodus 20:1-17 and Deuteronomy 5:4-21. I quote from Exodus, King James Version.) In the next essay I shall reconstruct them from the perspective of a science- and reason-based moral system.

I. Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

First, this commandment reveals that polytheism was commonplace at the time and that Yahweh was, among other things, a jealous god (see God’s own clarification in Commandment 2). Second, it violates the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution in that it restricts freedom of religious expression (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”), making the posting of the Ten Commandments in public places such as schools and courthouses unconstitutional.

II. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the LORD thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me.

This commandment is also in violation of the First Amendment’s guarantee of the freedom of speech, of which artistic expression is included by precedence of many Supreme Court cases (“Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech”). It also brings to mind what the Taliban did in Afghanistan when they destroyed ancient religious relics not approved by their Islamist masters. Elsewhere in the Bible, the word “idol” is synonymously used, with the Hebrew word pesel translated as an object carved or hewn out of stone, wood or metal.

What, then, are we to make of the crucifix, worn by millions of Christians as an image, an idol, a symbol of what Jesus suffered for their sins? The crucifix is a graven image of torture as it was commonly practiced by the Romans. If Jews today were suddenly to start sporting little gas chambers on gold necklaces the shocked public reaction would be as unsurprising as it would be unmistakable.

I the LORD thy God am a jealous God.

That might explain the genocides, wars, conquests, and mass exterminations commanded by the deity of the Old Testament. These humanlike emotions reveal Yahweh to be more like a Greek god, and much like an adolescent, who lacks the wisdom to control his passions.

The last part of this commandment—visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me—violates the most fundamental principle of Western jurisprudence developed over centuries of legal precedence that one can be only be guilty of one’s own sins and not the sins of one’s parents, grandparents, great grandparents, or anyone else for that matter.

III. Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain, for the LORD will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain.

This commandment is once again an infringement on our Constitutionally-guaranteed right to free speech and religious expression, and another indication of Yahweh’s petty jealousies and un-Godlike ways.

IV. Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Again, freedom of speech and religious expression means we may or may not choose to treat the Sabbath as holy, and the rest of this commandment—For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy—make it clear that its purpose is to once again pay homage to Yahweh.

Thus far, the first four commandments have nothing whatsoever to do with morality as we understand it today in terms of how we are to interact with others, resolve conflicts, or improve the survival and flourishing of other sentient beings. At this point the Decalogue is entirely concerned with the relationship of humans and god, not humans and humans.

V. Honor thy father and thy mother.

As a father myself, this commandment feels right and reasonable, since most of us parents appreciate being honored by our children, especially because we’ve invested considerable love, attention, and resources into them. But “commanding” honor—much less love—doesn’t ring true to me as a parent, since such sentiments usually come naturally anyway. Plus, commanding honor is an oxymoron, made all the worse by the hint of a reward for so doing, as in the rest of that commandment: “that thy days may be long upon the land which the lord thy God giveth thee.” Honor either happens naturally as a result of a loving and fulfilling relationship between parents and offspring, or it doesn’t. For a precept to be moral, it must involve an element of choice between doing something entirely self-serving and doing something that helps another, even at the cost of oneself.

VI. Thou shalt not kill.

Finally, we get a genuine moral principle worth our attention and respect. Yet even here, much ink has been spilled by biblical scholars and theologians about the difference between murder and killing (such as in self-defense), not to mention all the different types of killing, from first-degree murder to manslaughter, along with mitigating circumstances and exclusions, such as self-defense, provocation, accidental killings, capital punishment, euthanasia, and of course war.

Many Hebrew scholars believe that the prohibition is against murder only. But what are we to make of the story in Exodus (32:27-28) in which Moses brought down from the mountain top the first set of tablets, which he smashed in anger, and then commanded the Levites: “Thus saith the lord God of Israel, put every man his sword by his side, and go in and out from gate to gate throughout the camp, and slay every man his brother, and every man his companion, and every man his neighbor. And the children of Levi did according to the word of Moses: and there fell of the people that day about three thousand men.”

How can we reconcile God’s commandment not to kill anyone with his commandment to kill everyone? In light of this account, and many others like it, the sixth commandment should perhaps read thus: Thou shalt not kill—not unless the Lord thy God says so. Then shalt thou slaughter thine enemies with abandon.

VII. Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Coming from a deity who impregnated somebody else’s fiancé, that’s a bit rich. However, the bigger issue is that this commandment, like all the others, is a blunt instrument that doesn’t take into account the wide variety of circumstances in which people find themselves. Surely grownups in intimate relationships can and should negotiate the details of their relationship for themselves, and one hopes that they’ll act honorably toward their partner out of a sense of integrity, and not because a deity told them to.

VII. Thou shalt not steal.

Again, do we really need a deity to command this? All cultures had and have moral rules and legal codes about theft.

IX. Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Anyone who has been lied to or gossiped about can explain why this moral commandment makes sense and is needed, so chalk one up for the Bible’s authors whose insights here were spot on.

X. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s.

Consider what it means to covet something—to crave or want or desire it—so this commandment is the world’s first thought crime, which goes against centuries of Western legal codes. More to the point, the very foundation of capitalism is the coveting or desire for things and, ironically, it is Bible-quoting Christian conservatives who most defend the very coveting forbidden in this final mandate.

The late Christopher Hitchens best summed up the implications of taking this commandment seriously, in an April 2010 Vanity Fair essay: “Leaving aside the many jokes about whether or not it’s okay or kosher to covet thy neighbor’s wife’s ass, you are bound to notice once again that, like the Sabbath order, it’s addressed to the servant-owning and property-owning class. Moreover, it lumps the wife in with the rest of the chattel (and in that epoch could have been rendered as ‘thy neighbor’s wives,’ to boot).”

After demolishing the Decalogue in his inimitable style, Hitchens proffered his own list of commandments:

• Do not condemn people on the basis of their ethnicity or color.

• Do not ever use people as private property.

• Despise those who use violence or the threat of it in sexual relations.

• Hide your face and weep if you dare to harm a child.

• Do not condemn people for their inborn nature—why would God create so many homosexuals only in order to torture and destroy them?

• Be aware that you too are an animal and dependent on the web of nature, and think and act accordingly.

• Do not imagine that you can escape judgment if you rob people with a false prospectus rather than with a knife.

• Turn off that fucking cell phone—you have no idea how unimportant your call is to us.

• Denounce all jihadists and crusaders for what they are: psychopathic criminals with ugly delusions.

• Be willing to renounce any god or any religion if any holy commandments should contradict any of the above.”

Hitchens caps his list in summary judgment: “In short: Do not swallow your moral code in tablet form.”

Now, that is a rational prescription! In my next Skeptic column here I will offer my own “Provisional Rational Decalogue.” So you don’t miss it please consider subscribing below.

#Michael Shermer#Christopher Hitchens#decalogue#ten commandments#the ten commandments#morality#christianity#judaism#old testament#bible#bible study#religion#religion is a mental illness

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I AM THE LORD THY GOD; THOU SHALT HAVE NO OTHER GOD BUT ME

𝙳𝚎𝚔𝚊𝚕𝚘𝚐 (𝟷𝟿𝟾𝟿) 𝙳𝚒𝚛. 𝙺𝚛𝚣𝚢𝚜𝚣𝚝𝚘𝚏 𝙺𝚒𝚎ś𝚕𝚘𝚠𝚜𝚔𝚒

𝙳𝚎𝚌𝚊𝚕𝚘𝚐𝚞𝚎 𝙸 :

"I AM THE LORD THY GOD; THOU SHALT HAVE NO OTHER GOD BUT ME."

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wolf archangel

Finished full render (colored, textured, lineless…ed?) for Mistress Snow on Telegram. Based on line art by Olivia Wolfe entitled "The Archangel".

Ironically, what gave me the most trouble here was the many tiny mountains Olivia drew on the planet to show just how far the angel towers over everything (yes, this was harder for me than the rays of light, the many little hairs, or even handwriting in Latin). I think I found a good solution by using height bands and defining that winds blow away from the viewer

Concept and design: Mistress Snow

Composition: Olivia Wolfe

Color and shading: Me

Want one like this? I'm open for commissions!

Share this on Twitter, Deviant Art, Fur Affinity, Ko-fi, and Mastodon!

Posted using PostyBirb

#macro#megamacro#wolf#protecting#world#planet#earth#lush#green#blue marble#decalogue#moses staff#cobra staff#snake staff#blonde#gold hair#halo#shining#glowing#stars#milky way#angel#wings#feathers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mercy Seat

10 “They shall make an ark of acacia wood. Two cubits and a half shall be its length, a cubit and a half its breadth, and a cubit and a half its height. 11 You shall overlay it with pure gold, inside and outside shall you overlay it, and you shall make on it a molding of gold around it. 12 You shall cast four rings of gold for it and put them on its four feet, two rings on the one side of it, and…

View On WordPress

#Ark of the Covenant#atonement#Day of Atonement#Decalogue#Exodus#Exodus 25#forgiveness#high priest#Holy of Holies#Jesus Christ#Mercy Seat#Sinai#Tabernacle#the Lamb of God#the Law

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments

1) Thou shalt love Yah-Hovah Elohim with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might;

2) Thou shalt not take the name of Yah-Hovah Elohim in vain;

3) Thou shalt keep thy feasts to sanctify them;

4) Honor thy father and thy mother;

5) Thou shalt not murder;

6) Thou shalt not fornicate;

7) Thou shalt not steal;

8) Thou shalt not lie nor bear false witness against thy neighbor;

9) Thou shalt not commit adultery;

10) Thou shalt not desire anything that is thy neighbor;

Two more commandments:

11) Do thy duty;

12) Thou shalt make my light shine.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Double (2013) // Decalogue VI (1989)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Basic Rules for Just and Prosperous Societies- Exodus 20:13-17

Honor Your Mother and Father- Exodus 20:12

–

Daily Devotionals with Andrew Cannon

God instructs the Israelites to honor their mothers and fathers–because that's what leads to a long life in the promised land. It's for their good, longevity, and prosperity.

Honor Your Mother and Father- Exodus 20:12

02:00

The Sabbath Is For Man- Exodus 20:8-11

02:59

Do Not Take God's Name in Vain- Exodus…

View On WordPress

#bear false witness#commit adultery#covet#daily devo#Daily Devotional#decalogue#devotional#do not#entitlement#Exodus 20#expository#Israel#jealousy#kill#lie#Moses#mount sinai#murder#quiet time#selfishness#short#steal#storm#ten commandments#thou shalt not

0 notes

Text

Catechism of the Catholic Church

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

1 I am the Lord your God: you shall not have strange Gods before me.

2 You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain.

3 Remember to keep holy the Lord's Day.

4 Honor your father and your mother.

5 You shall not kill.

6 You shall not commit adultery.

7 You shall not steal.

8 You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

9 You shall not covet your neighbor's wife.

10 You shall not covet your neighbor's goods.

0 notes

Text

Our people are falsely accused of prohibiting good works. For their writings on the Decalogue and others on similar subjects bear witness that they have given useful instruction concerning all kinds and walks of life: what manner of life and which activities in every calling please God.

~Augsburg Confession 20:1-2 (Latin Text)

0 notes

Text

The Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-21)

Since relationships are important and necessary, we need a way to be in community together so that everyone can get along and thrive as human beings.

The Ten Commandments by He Qi

Then God gave the people all these instructions:

“I am the Lord your God, who rescued you from the land of Egypt, the place of your slavery.

“You must not have any other god but me.

“You must not make for yourself an idol of any kind or an image of anything in the heavens or on the earth or in the sea. You must not bow down to them or worship them, for I,…

View On WordPress

#decalogue#exodus#exodus 20#freedom#god&039;s instructions#god&039;s commands#heidelberg catechism#interpersonal relations#moses#relational connection#relationships#social expectations#social relationships#spiritual life#ten commandments#ten words

0 notes

Text

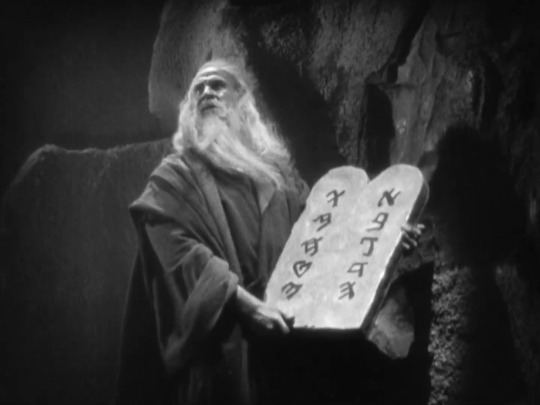

The Tenth Commandment

The Ten CommandmentsScreenshot from the Silent Film (1923).Director: Cecil B. DeMille

In my study of the Deuteronomic concern for the status of women in Israelite society, I will discuss a few of the laws enacted in the book of Deuteronomy that seek to improve the legal rights of women in Israelite society in the seventh century BCE. Today I will continue my study with a review of the Tenth…

View On WordPress

#Decalogue#Deuteronomy#Hebrew Bible#Israelite Law#Old Testament#Ten Commandments#Tenth Commandment#Wife#Women#Women’s Rights

1 note

·

View note