#dark souls analysis

Text

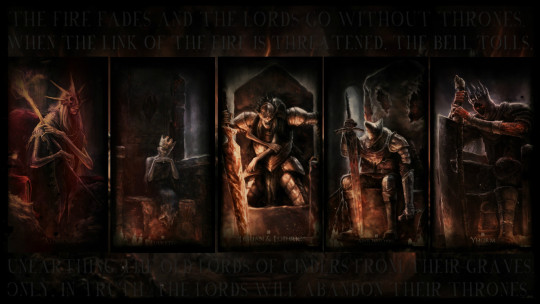

The Soul Still Burns: Analysis of the Lords of Cinder (DS3)

What follows is a short essay on the Lords of Cinder from Dark Souls 3, exploring their symbolism on spiritual and metatextual levels. After that is a related reading of Slave Knight Gael, the final adversary of the Dark Souls trilogy.

The Lords of Cinder are in many ways the primary adversaries of Dark Souls 3. This title they share, “Lord of Cinder,” refers to a personage who has rekindled the first flame, keeping the cycle of light and dark going.

Cinder is a substance which continues to burn without the presence of fire but does not reduce to ash. So euphemistically, it seems that the Lords are somehow stuck in their process of purification, and the game suggests that the world is stuck along with them; this is why it is the Ashen One’s task to “set them upon their thrones”—to hurry them along and thus allow the world to follow its natural decline. As individual characters, each of these Lords represents a different attitude that complicates and prolongs the cycle.

Through these stubborn Lords the game is commenting on at least two things. On the metaphysical level, it reflects the Buddhist idea that certain attitudes keep people reincarnating over and over again, unable to extricate themselves from the material world of suffering (samsara). While on the metatextual level, the game is suggesting that certain attitudes keep players coming back to Dark Souls again and again, starting new games, making new builds and revisiting old files.

The idea there on the metaphysical side finds an easy analogy in Buddhist doctrine: the “three poisons,” the three root causes of suffering. These are hatred, greed, and delusion. What’s interesting is that these essential vices also fit pretty easily onto the different types of players that are being caricatured by the Lords. We’ll break these correspondences down in a second.

But First: Why Do They Correspond?

So we have these sets of three. Three lords, three poisons in Buddhism, three types of Souls players. How convenient. When we analyze art, we sometimes ask, “Huh, is this structure really there, or am I projecting it into the material?” And if the structure is really there, baked into the work, that doesn’t mean that it’s due to developer intention. Archetypal forms sometimes show up in work via an unconscious influence, be it due to the cultural milieu, personal psychology, or some a priori biological disposition of the human being.

And the thing about Dark Souls is that it’s an unusually honest piece of art, in that its creative team allows their own free associations and intuitions to show up in the work without too much self-censorship or questioning. They make space for a mystery to show up on its own terms, and in leaving its riddles unanswered, there is more space for discovery by the people who play it.

It should also be said that cultural ideas persist for a reason. Beneath the ethics and ideology of the people who originally named the Buddhist “three poisons,” there may be something timeless, something perennially descriptive of human nature. If that is the case, then it would make sense for this same triplicity to unfurl itself in other cultural products. So for one reason or another, these three poisons, these addictions, show up diegetically in the characters and are also expressed in player psychology.

I say all this just because sometimes I feel very aware of the disconnect between much of Souls lore discourse and the broader field of mythological study. Since we are gamers first, there may be this tendency to want to “solve” the lore, but that’s not what we’re doing here. Myth functions because it elaborates our experience of the world through affective resonance; it attaches images and characters and stories which help us anchor our own prelinguistic impressions of the world, cultivating our sensitivity there.

Anyway, let’s look at these Lords.

Abyss Watchers

Poison: Hatred

The lore of the Abyss Watchers is pretty clear: they have an obsessive fixation on the abyss, and are ready to raze an entire town if they suspect abyssal encroachment. This obsession has literally possessed them, as they are now “abyss touched.” Gaze too much into the abyss, etc. They carry such strong contempt for the disavowed object that they don’t care what comes between it and their sword. This is clearly demonstrated by the fact that they are a brotherhood yet are unhesitatingly slaughtering themselves again and again. Hatred has made them blind, and has also caused them to resign their individuality (they are identical, mere instruments of a transpersonal grudge). They cannot die, their hatred keeps them locked in combat.

Type of Player: competitive | Interest: combat

The Abyss Watchers are a representation of PvP addicts. They have no powers other than tenacity; they perform the same combos repeatedly. When you are really gripped by a PvP binge in Souls, you often end up doing the same thing again and again. The fight takes place in a mausoleum, on top of many chambers filled with human remains. The fact that this boss fight is instructional about combat, specifically about looking for tells (a cloud of dust always signifies the end of their combos) might be another clue. There is no limit to how good you get at Souls PvP; every foe is an opportunity to improve timing and strategy. You can just keep stacking anonymous bodies under yourself.

Aldrich

Poison: Greed

Aldrich invokes the concept of supremacy many times: he is in the supreme area from Dark Souls 1; in the supreme boss room of that area; he wears as a crown the former supreme lord of that area. This is because he devours lords; he tries to take prestige upon himself through acquisition and incorporation—greed.

Type of Player: completionist | Interest: content

Aldrich is a commentary on completionist players. He is someone who “plays the game to death”, acquiring every object, reaching every achievement, devouring the soul of the game through taking everything into himself. He becomes bloated by consuming as much of the game’s content as possible. The old God whose likeness he has adopted is Gwyndolin, who was, in narrative terms, the one pulling the strings in the land of the Gods. And in gameplay terms, he is a secret boss. So on both counts we have someone who is elusive, and exists more or less at the boundary of the gameworld. When a player tries to see every last little morsel of a game, they become somewhat like Gwyndolin, a manipulator of a virtual world. If you know too much about a game, you have the risk of being less immmersed.

Yhorm

Posion: Delusion

In Buddhism, the poison of delusion secretly underlies the other two poisons, as the impulse toward hatred and greed are ultimately born of some false view about reality. This is akin to how the profaned capital sits below the rest of the kingdoms. To beat Yhorm you essentially have to “play pretend” with him, picking up a fake super-weapon, or fighting alongside Siegward, a knight who appears to be somewhat deluded about the state of the world, enthralled in the same fantasy as Yhorm himself.

Type of Player: lore researcher | Interest: meaning

The profaned capital is full of statues—fixed images of myth; and empty goblets—treasures with no utility. Not to mention the area with the swamp which is full of symbolic imagery, but serves no narrative or mechanical purpose. The entire profaned capital challenges us to make sense of it; it is the ultimate temptation of lorekeepers in DS3. It throws at us a disproportionate amount of reference to DS2, which is famous among Souls players as the least thematically sensible Souls game. The Greatshield of Glory is found right outside Yhorm’s room, in a conspicuous room full of treasure, and yet it is a very impractical shield and offers very little lore value. If a lore-minded player picks it up, it directs them to a legendary personage from the War of Giants, which raises far more questions than it answers. The same is true of much of this area—the Eleanora, the Monstrosities, the Profaned Flame itself—they are all there to get you to speculate. These are the players who come to Souls games again and again, trying to find the “ultimate meaning.” They seek the grail, claim to find it, and then chuck in a pile with the others.

Yhorm's story also imitates the primordial Artorias myth: forsaking his shield in preservation of something more valuable. Other than that Yhorm is largely a cipher when it comes to biography, with a void for a face, which itself epitomizes what must remain at the center of mythology and storytelling: mystery.

Sit Down and Seek Guidance

So we have the three reasons that people become fixated on Souls: the combat, the achievements, and the mystery. But there is a fourth lord of cinder boss, who is conceptually apart from these three: the Lothric Twins. They represent yet another kind of person who must keep playing Dark Souls: the developers. Lothric is striving to produce “a worthy heir,” a proper sequel to Dark Souls 1. The Princes are bound to their chamber as the developers are bound to their project, as that is their curse—“but you may rest here too, if you like.” In this context we can see their duality as the dual nature of having to work on the game and also play it to death. The privilege and the loftiness of the promise of a great piece of art (Lothric), and also having to go back "into the trenches" of the work itself (Lorian). Notably, neither of them can walk, they just teleport around. They are stuck at work, trying to bring the new world into being. Also I can’t go this whole essay without mentioning the obvious: that the Ashen One is bringing Lords to their thrones, and we players and developers have to assume our little chairs and couches when we access this world.

Playing Beyond the Point of Pleasure

Of course the most extreme example of someone stubbornly remaining in the world no matter what is Slave Knight Gael. He is looking for pigment, which seems to be a euphemism for the substance of humanity (the Dark Soul). He wants to give it to the painter, the world-creator, so that a new world can be made. He is willing to indulge in a wasteland of abject violence for as long as it takes in order to renew something. Ironic that he is probably only prolonging the current world in his obsessive drive to recycle it faster.

Let’s examine the relationship between the figure of the painter and her relationship to Gael. That she is a spiritual entity is obvious: we never see her touch the ground, she is always in an upper room and lifted on a piece of furniture. Among other things, she is a clear metaphor for life springing eternally. A creative child who continues to paint despite kidnapping and imprisonment. She is the heart of the painted world, itself a place that symbolizes the idea of the representation of reality.

I want to make sure this is clear, because it is a bit of a kaleidoscope to consider. Any subject in Dark Souls stands for many things, but something that the painted world specifically represents is the very concept of representation. So of course the places in our imaginations are painted worlds, but so is this physical world of appearance, the maya of mundane reality. Not to mention that a work of art is a painted world, and the game we’re discussing is a painted world. When a work of art is able to recreate itself in itself, we can see this funny effect of mirrors reflecting mirrors infinitely. This results in seemingly inexhaustible symbolic content—there is so much potential to find meaning and create connections. Because Moby Dick represents a work of literature; the Tempest represents a play; Twin Peaks represents a TV show, these works can offer extensive insights not only into their medium but into the nature of reality. In these and other examples, the representation of the medium within the work may or may not be a single subject, but since Dark Souls is formally a game about levels and level design, the painted world is the heart of its self-reflexivity. The painted world can be pointed to as the summary of this fractal device. And the personification of that device, its ambassador to the player, is the painter.

The miracle or divine child is also an archetype familiar to us from Lothric, in their struggle to produce the “worthy heir.” Reality seeks salvation through the appearance of grace. They want it in a clear, incontestable form—to be able to point at it and say, "thank goodness we went through all that, because look, now here is the meaning, here is that which validates all that came before." In the world of Dark Souls 3 the religion of the masses is the Lothric stuff; meanwhile knowledge of the painted world is much more obscure. Lothric’s religion is obviously regulated and hierarchical, while Gael’s devotion to the painter is highly personal and private: he carries around a scrap of painting; he prostrates to a hidden idol in a small chapel; he considers the painter his family. He is emotionally close to the object of his worship.

But whether it’s Lothric or Ariandel, they are anticipating the divine child to redeem the world. As an archetype, the child ultimately represents surprise. The possibility of being delighted by life in its creative novelty. The child as an archetype appears in our own behavior when we do something without any sort of contrivance or mental interference, doing something in the world which doesn’t seem to have come from who we conceive ourselves to be. This is miraculous. Such an action enchants the world, and there is no explaining it, even if it may weave all kinds of stories around itself, retroactively framing things that have led up to it as portents or promises. (Though not exclusive to him, this trait is well-known in characterizations of Christ, and DS3 is clearly indebted to Christian iconography, so do with that what you will). Regardless of the specific cultural invocation, the divine child is a personification of something that happens within the human spirit. TFW you are renewed by a fresh and spontaneous engagement with life.

The grace of the miraculous often comes to us through play. Play is more of an attitude than an activity; the feeling of play may come to us through making a painting, or chatting with a friend, or moving around in a video game. We can play video games idly, competitively, experimentally, creatively, studiously, whatever, the feeling of “play” can show up regardless. We can sit there playing a certain game from a certain motivation, and feel totally rote and joyless, and question, “Why am I doing this?” Or we might sit there and play the same game with the same motivation, feeling totally lit up by it, its purpose to us obvious and self-validating. We are not even questioning why we are doing it, we are enjoying life.

This is really the ground that the miraculous tends to land on. Grace, meaning, and an immanent love of life are more likely to show up when we are in flow and not exercising our capacity for self-assessment. But like everything in life, we mistake the images and objects around us for the feeling of grace. Any given object might only be the catalyst once; it’s not about the object. This is extremely easy to see in cases of acute nostalgia; adults chase enchantment through collecting Zelda memorabilia or going to Disneyland, in pursuit of what kindled their spirit as a child. It was never really the game or the character that was doing it, it was what they were able to access within themselves.

So anyway Gael has yet to realize this. He thinks the Dark Soul is out there in something else. That it will be yielded as a drop if he just kills the right enemy, or 10,000 enemies, or goes to the right place at the right time. You can see that this is something of a synthesis of all the other Buddhist defilements: there are elements of completionism/greed, violence/hatred, mysticism/delusion. There is even the suggestion of the developer of these games again, in that Gael is a “slave,” forced into participation in the world to assist some creative apotheosis. (Isn’t it funny that his weapon is a worn-down executioner’s sword?—whether the person coding or the person playing, we are all “executing” command after command). The thing that really keeps him on the wheel is something beyond any of the player types and their vices; it is almost some sort of pure, amoral automatism, a churning drive that on one side resembles wanton nihilism, and on another side single-minded piousness. Is one disguised as the other, or has Gael somehow stepped beyond this binary? Yet another dichotomy in Dark Souls that begs to be reconciled, but whose tension creates the opportunity to participate creatively in its expansive mythology. When things are held apart we can move between them.

To really understand Gael, we have to contend with the question of a person’s relationship to their own soul, since that relationship is so plainly suggested by Gael and the painter. (This question, by the way, is much elaborated in Elden Ring, with its repeated foregrounding of the image of the maiden or “consort”). If we were to see Gael and the painter as partitions within one person--whether she is his soul, or his inner life, or his better nature, whatever—then in any case Gael is the side which goes out into the world and experiences it. He is the creative extension into the world as its active participant and realizer. Yet he is clothed as the warrior, the executioner. While the one who is dressed as the artist, the painter, just stays in her room and imagines the world—but this is where the magic of creation is really felt. We involve ourselves in life, or in a game, but we are only really changed and renewed when that exterior experience is “brought home” into the inner life. We do something “in the game,” but the act of “painting,” in renewing the world through our creative interpretation, is a decidedly interior experience.

#dark souls#dark souls 3#lords of cinder#game entrainment#dark souls analysis#dark souls lore#ariandel#slave knight gael#the painted world

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the most primal, all-encompassing fears that we experience is that of change. It is connected to our other primal fears - death, the unknown - in an amalgam that looms over our every waking moment if we allow it to. It finds itself in a great many places, but, in this case, in two works of fiction in particular, where it fuels hierarchies that try their hardest to bring time to a shuddering halt by means of sacrifice and abuse and pain. The “rabble” doesn’t know just how futile it is, this house of cards that they help hold steadfast. But up and up the line, we find the most tightly controlled “puppets”, those who abuse and are abused for the sake of keeping everything exactly the same. Among their number, a stranger who is dragged in all too quickly, chosen by something between being in the wrong place at the wrong time and deliberate effort; a supporter who, at least at first, leads them as a lamb to slaughter; several others ranging from fencers to the disgruntled who nearly see through the system but cannot bring themselves to act against it; and at the very top, a man. Half-dead, half-alive, and very, very scared.

Even in his absence, however, the machine marches onward, looping over and over - not in time, but in something else, reset but moving ever forward and ripping itself apart in the process - until someone puts a spoke in the wheel and ends it once and for all. Or, alternatively, if the right person leaves, the system may very well crash and burn on its own.

Guy who has only played Dark Souls and Guy who has only watched Utena is a combo I would say I wouldn't wish upon anyone if I didn't want more people to suffer the way I have suffered

#revolutionary souls#dark souls#gwyn lord of cinder#fromsoftware#dark souls analysis#revolutionary girl utena#shoujo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#akio ohtori#utena tenjou#anthy himemiya#the chosen undead#no one is mentioned by name but boy are they mentioned#gwyn and akio are not the same guy at all but they are thematically related#gwyn has actual power lololol#utena analysis

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#dark souls#dark souls 3#dark souls meta#dark souls analysis#souls games#video essay#husband did this#Youtube

0 notes

Text

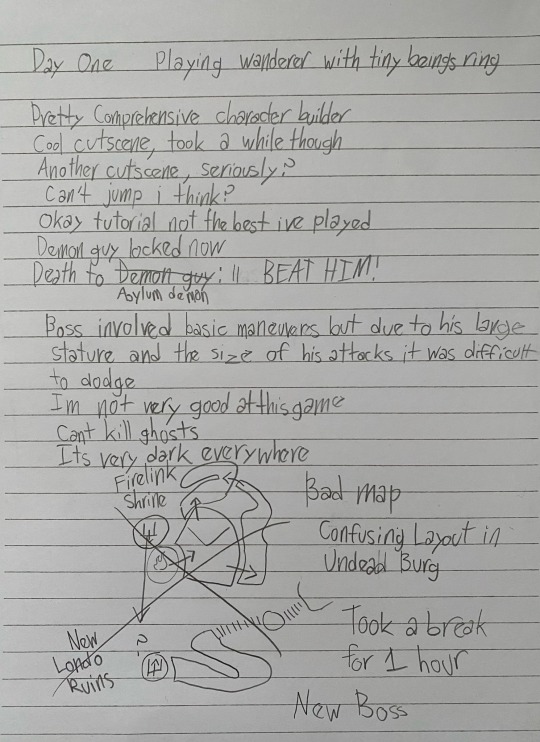

Playing Dark Souls Blind— Day One

First impressions: the game is hard, but not frustratingly so, at least for me. Most deaths just make you want to go back and hunt down what killed you. Combat is deliberate and strategic, but the downside is that it typically boils down to all movements taking a long time to complete. Overall a fun game.

0 notes

Text

Lord Gwyn: The Perfect Anticlimax

"Dark Souls is a hard game"

To anyone who's even a little bit familiar with the franchise, this is an obnoxiously obvious statement. The game has held the title of THE "hard game" for so long, that not only has the statement "X is the Dark Souls of Y" become a cliche, but so has every subsequent mocking subversion of that comparison. To even acknowledge its obviousness, as I did, is territory so well-worn, that I'm at risk of falling through, into the hackneyed void. But it's still worth mentioning. It's a well-earned reputation. Not only is Dark Souls, on a purely technical level, difficult to beat, but its entire identity is based around its difficulty, if the name of the "Prepare to Die" edition is any indication. Its world is a punishing one, seeking to beat the player character down at every single opportunity, until they can't stand to move another step forward, lest they get thwacked by a swinging axe, skewered by a demon, swept off a cliff, or obliterated by a dragon with teeth where its torso should be. It's a game that crushes you down, intending to make very clear just how easy your character can die, and, importantly, just how unimportant your death will be. To these bosses, these titans, these near-gods, you are nothing but an annoyance. Many of these fights feel like climactic struggles against an ancient, near-unbeatable foe, who existed long before you were born, and has a pretty solid chance of existing after you've expired. When you enter the arena of Ornstein and Smough, the music swells, and the two knights flex the skills that they're going to use to kill you over and over again. Many of the game's bosses, try to tap into that sense of scale, of importance, of grandiosity, each of their respective battles feeling like they could easily be the final one.

Then, after a long struggle, you make it to the end.

The game's final boss is Gwyn, a towering figure who's been hinted at throughout the game, through dialogue and item descriptions. Even if you didn't pay much attention to the little pieces of lore that the game hands you, you're able to put together that he's a pretty important guy: the mighty Lord of Cinder. The buildup to his fight hints at an even larger presence than the other bosses. You travel beneath Firelink Shrine, your home base for most of the game, where you find a massive expanse of land, cold and dark, a mysterious coliseum-like structure looming in the distance, which is impossibly large, even so far away. As you get closer, ghosts of old knights appear to attack you. They are easily dispatched, but still a shock. The structure towers over you, emphasizing just how much space is needed to house this mythologically strong figure, and the power that he holds. You enter, and find…….a hollowed old man. He's slightly taller than you, dressed in robes, and wielding a flaming greatsword, but he's nowhere near the scale of other bosses. However, he rushes at you all the same. When you begin the duel, it feels different from the others. There is no dramatic, sweeping music. All you get is a somber piano, like something that would play during a funeral, rather than a climactic duel. It feels like Gwyn's theme is actively pitying him. Granted, it's appropriate for the fight. All Gwyn can do is swing is flaming blade, which you can avoid with ease. There's been some easier bosses, but at least they didn't feel like they WANTED to die. Besides, this isn't the fragile Moonlight Butterfly, or the starting Asylum Demon, this is the final boss! He should be challenging you! Putting all the skills you've learned to the test! He's a fucking King! Why isn't he stronger? Fighting Gwyn after you've fought everyone else feels like walking into the home of an old, dilapidated hoarder, and kicking him while he's down. If you've been practicing your parrying, its like doing the same, except with cleats. He just seems………tired. As pathetically destitute as you were at the start. He might as well just keel over when you walk in the door. You beat him, naturally, and then the game just kinda….ends. If you got the ending I did, you just exit the area, look at all the nice snake friends you just made, and then roll credits. For all the work you've put into getting here, and all the struggles you've had to overcome, it feels like a severe anticlimax, like the game is playing a prank on you.

But if you know anything about the setting of Dark Souls, you'd know that there's really no other way this could end.

"The world of Dark Souls is dying"

This is a phrase that, while not as oft repeated as the above, is also pretty common knowledge at this point. Lodran, the game's setting, is a desolate place, long past its glory years. Once a powerful kingdom, teeming with life and magic, it is now in ruin, every citizen either dead, hollowed, or left to survive amongst the numerous deadly creatures that now roam the land. Everyone who's still around at the start of the game is either destined for misery, or already there (Unless you're Andre. He seems to be doing pretty well, all things considered). Somewhere around the time Lordran has reached the end of its life cycle, is when the player character enters the story, albeit with a rather unenviable role. Your job is to essentially be the world's janitor, cleaning out the world's former main characters, most of whom are insane, and all of whom are well past their useful days (or, if you have the DLC, you get to see Artorias right as he passes this point). Unfortunately, most of them would like to keep being alive, so they're going to make that difficult for you, by turning you into red mist until you stop trying to kill them. Even the grandiose presentation some of them have can't entirely hide the fact that this is a rather sad state of affairs for everyone, especially for those who haven't really done anything wrong (I nearly cried at having to kill Sif, and I will never fight Priscilla). Fortunately, some of these bastards contributed to the world's current bleakness, so killing them provides at least a twinge of catharsis, albeit one that will certainly be gone by the time you move onto the next bastard. The goal of this whole clean-up process, is to prepare the world to either continue with the age of fire with you as the catalyst, hopefully without those brutes who were clogging the power vacuums, or plunge the world into a new age of darkness, now that it has been cleansed of its polluting influences.

The only mean to either of these ends, is to kill Gwyn, the Lord of Cinder, former ruler of Lordran, and one of the primary reasons that this world is such a goddamn mess. To sum up his actions without getting too deep into the lore's intricacies; Gwyn knew that his kingdom was destined to fall, due to the world's oncoming transition from the age of fire into the age of shadow. This transition was represented by the dwindling light of the first flame, the lifeblood of the kingdom. After utterly failing to rekindle it, Gwyn entered a final gambit to prolong the life of his empire, linking himself with the first flame, but burning himself, and many of his knights, away in the process. This left him as a hollow, doomed to languish in his kiln, until another unfortunate soul took his place, linking the flame to further prolong the changeover. In doing this, Gwyn went against the natural laws of his world, which didn't react well to having its transitionary cycle interrupted. The world fell into a sharp decline, becoming a desolate, unhappy place, festering with demons and monsters (many of whom were the result of the last time someone tried to rekindle the first flame), making life hell for anyone unlucky enough to still be around afterwards. Gwyn wanted to prolong the inevitable, prevent the death of his kingdom, and continue its prosperity, so he sacrificed everything. His realm has persisted, but in a state of undeath, having stuck around long past its natural expiration date, just like him. Gwyn's story can be properly summarized as what happens when someone is psychotically obsessed with preserving their power, even when that preservation only serves to make the world a substantially worse place. Gwyn, in his hollow state, is a symbol of Lordran's persistent deterioration.

None of this information is directly handed to the player. Some bits are alluded to through snippets of dialogue and item descriptions, and the opening cutscene depicts one of the major inciting events of the narrative, but for the most part, it's a sprawling, multi-phased story, that is dolled out non-linearly, and piecemeal.

Now, with that context, let's cast a new lens on that fight…

After delving underneath Firelink Shrine for the final time, you come upon a desolate landscape, the Kiln of the First Flame looming in the distance. It's clearly well past its glory days, looking decrepit and sad. It is home of the world's lifeblood, but in name only. Now, it holds the last remnant of an age long past. As you approach, the spirits of old knights come to attack you, but they aren't much of a challenge, being just shadows of their former selves. They're victims, really; their loyalty has bound them to a sorry task, but they're in the way, and they weren't really living much of a life anyway. When you get closer to the kiln, it feels impossibly large, but also cold, and surprisingly dark, for something that's supposed to house an eternal flame. When you can see more details, it becomes clear just how long it's been falling into ruin. It feels abandoned, but you know its not. After all, you're here to end the life of its only resident. You enter, and find…. Lord Gwyn, a king who destroyed himself and cast the world into ruin, just to hold on to a formerly prosperous time. Lord Gwyn, whose refusal to let the fire die is the reason why you had to struggle through this entire journey. Lord Gwyn, whose death will mark the end of a era, no matter what you do afterwards. He charges at you, barely even conscious anymore, having been locked in this tomb for unknowable amounts of time. But he can't really fight you, at least not well. His strength isn't nearly what it used to be, now that he's a hollow, tired and worn-down, just like you were at the start. He's a pitiable figure, and the music knows. That sorrowful piano fades in, almost like something that would play at a funeral. But this isn't a funeral. This is a mercy killing. Spiritually, Gwyn died a long time ago. You're just putting his body to rest. When he's finally dispatched, it feels like an anticlimax. But of course it is. Gwyn is the embodiment of the world you've spent so much time exploring. Lordran has been denied a proper climax for so long, because he extended the story long past where it should have ended. He's been waiting to be killed for ages now. It feels only right that Gwyn be an easy, anticlimactic boss, because how could such a destitute figure be anything else?

"Dark Souls is a hard game for a reason"

The above statement is a simplified summation of why Dark Souls is one of my favorite games that I’ve ever played. It's set in a dying, hostile world, that's been brought to ruin by the violation of its natural laws. Thus, the game is insistent on making the player struggle at every turn, to make them feel just as downtrodden as the world they explore. Lord Gwyn is a example of just how thoroughly holding onto power can corrupt someone, leaving them as a husk, the scraps of their former glory existing only the in the memory of the people who are still forced to cope with the consequences of their selfish actions. Thus, his boss fight is an intentionally easy anticlimax, to emphasize just how far he's fallen, to the point that he can't even put up a good point. It's the themes of his character, perfectly melding with the gameplay. It's a perfect encapsulation of the game's best quality, how the experience of playing the game, reflects the themes and tone of its story. The reasons why the fight with Gwyn is the perfect anticlimax, and why Dark Souls is a near-perfect game, are one and the same.

#video games#gaming#dark souls#dark souls 1#fromsoftware#fromsoft games#Gwyn#game writing#game analysis#boss fight#videogame#game#long post

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Begging Soulsborne fans to actually think critically about the games they enjoy instead of just memorizing 15-hour lore videos

#lore is fun but for the love of god please learn what “subtext” and “authorial intent” are#media analysis is so fun#why do these people insist on avoiding it at all costs?#demons souls#dark souls#bloodborne#sekiro: shadows die twice#elden ring

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

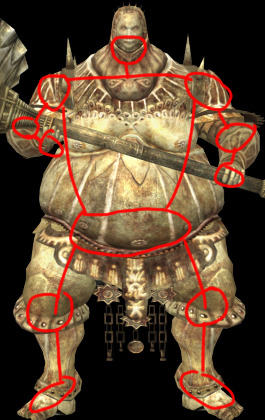

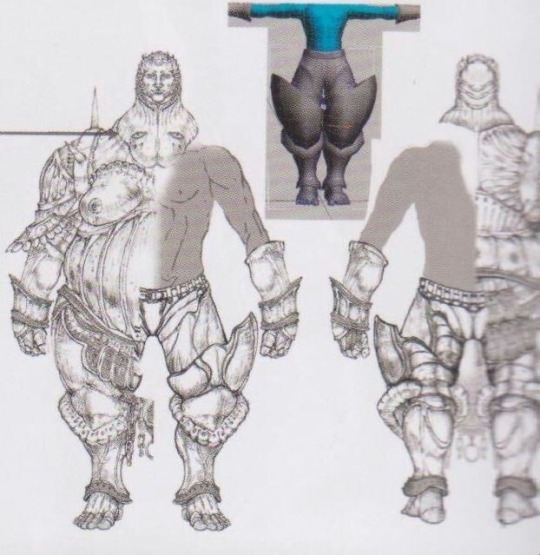

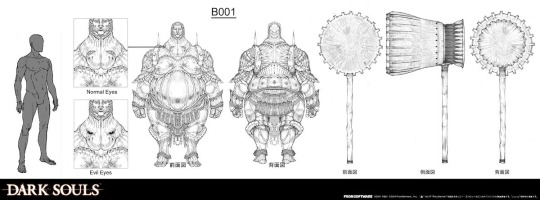

Smough's Armour is Deceptively Clever

First off, the helmet. It's common knowledge that the part with the face is actually ABOVE Smough's head, designed to draw blows away from his face, however his head ALSO isn't located by the eye-markings either:

It's a double fake-out! And best of all it's surprisingly well thought out. Armour works best when it leaves room between metal and body to absorb blows. The usual problem with full helms like Smough's is that the only way to see through them with any sort of efficiency is to press one's face right up against the holes/slits, leaving very little space for shock absorption.

Now notice how the part with the lower "eyes" bulges outwards. It's the EXACT shape you want when deflecting blows! So you either hit the upper "face" and miss completely, or hit the lower "face" and bounce right off.

For a massive fellow like Smough, aiming for his head is the most efficient way to take him down, and he KNOWS that.

This deceptive strategy is utilized ALL throughout Smough's armour, primarily because he isn't actually fat according to his concept art. The bulbous shape of his armour exists entirely to deflect blows and make enemies assume it reflects the anatomy within.

#dark souls#soulsborne#executioner smough#ornstein and smough#from software#armor design#armour design#design analysis

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psychology of... Willow?

When I set out to do this series, I had a few episodes noted down where I would use the analysis of that post to look into one specific character and their psychology, writing, and the cinematography surrounding that character. For example, I still plan on my analysis of Labyrinth Runners delving into Gus.

But one such episode that I had noted down was Understanding Willow. I planned on examining its eponym's struggle with bullying and how that impacted her mental health.

But this episode is more complicated than that, and I'm not entirely sure that it's about Willow.

Let me explain.

SPOILERS AHEAD

One criticism of The Owl House is that it starts slow, and while my contrarian streak leads me to disagree with that, it is difficult to argue that the series doesn't abruptly gain speed with Understanding Willow. The animation, visual metaphors and storytelling, and the direction all skyrocket.

This is the episode where the series brings its complex storytelling to the forefront, and a key example of this is that this is about Amity as much as it is about Willow.

The premise of this episode is memory. What if memories are tangible? Maybe they are tampered with, or damaged? What if memories could be seen by others? What power does a picture have? Put a pin in this.

In February 2022, Steam Forge games released the Dark Souls Role Playing Game, and bear with me, I promise this is relevant. It is based off the Dark Souls series and the Dungeons and Dragons 5th Edition system. But I would argue that it pales in comparison to Emanuele Galletto's Dark Souls Unofficial Role-Playing Game.

Galletto's system is a fascinating take on the series it is based on, and is surprisingly balanced, but I'm not here to give a review. Instead, I would like to focus on the rules for humanity and their implications.

Essentially, because death and rebirth are common in the game, in order for stakes to mean anything, Galletto implemented an idea called Sparks of Memory. When a character dies, they lose their memories. These can be sacrificed in exchange for abilities upon level ups, or they can be established through the game and through the adventure itself.

"When you die, you lose a Spark of Memory: a piece of your being will be forever lost, and you will be a step closer to losing yourself... With time, you might become an entirely different person, driven by a strong will but completely changed by the trauma of death and reshaped by your journey throughout this accursed land."

This system is called Humanity, the passage above is taken from a page literally entitled "Loss of Humanity", which means something, right? But weirdly enough, this is a system that forces optimism. Pessimism and fear that the world will only get worse are not particularly good motivators. Anger and grief at specific moments are all well and good, but at the end of the day, when they leave your character, why are you still moving forwards? Hope.

When I was playing this, I genuinely watched the power of friendship develop into a major force in the campaign, as the characters reassured each other and formed these memories together. If memories are who you are, then people who remember you are equally important in keeping you in check. These were people who developed into relentlessly determined heroes, with a grim focus on making the world a better place, together.

I have never really cared about the science fiction debate of what constitutes humanity, but this is a genuinely interesting take on the question that I highly recommend experiencing yourself.

But why have I just spent almost 400 words talking about Dark Souls? Because Understanding Willow displays some of the same ideas. Memories are what makes Willow who she is, and when those get damaged, she runs into problems. What is fascinating, is how much of Willow's memories were formed in relation to others. Her fathers (hey, gay male representation in cartoons, don't see that often) feature often, but so does Amity.

Bullying is one of those almost universal experiences in life. If you haven't been a subject of it, you have probably witnessed it.

Studies have been trying to ascertain the impact of bullying on mental health since at least the 1970s, with the oldest source I could find being Dan Olweus' 1973 Victims and Bullies: Research on School Bullying, although that was written in Swedish, and I haven't been able to find a copy of that original book. It was allegedly published in English in 1978, retitled Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys, of which the internet archive has a copy that is available.

Research into the subject has continued into the modern day and has been updated to modern scientific and psychological practices. For example, this study was published in 2021, and concluded that: "Reports of mental health problems were four times higher among boys who had been bullied compared to those not bullied. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.4 times higher."

What this means is that it is important to understand Willow in the context of Amity, and it is important for Amity to witness that effect directly in order to change herself.

Sorry, wrong image. How did that get in here? That's from a game called Melatonin, by the way.

There we go.

So, memories in the Owl House are tangible. They can be changed, or erased artificially, and "artificially" is the key word here, because memories can change naturally. A rare few people are infallible in that regard. But Willow is making an attempt to forget her life with Amity, she turns it away and avoids talking about it, rather than confront her past.

"That's my motto after all. Out of sight, out of mind."

It's notable that the illusion teacher governs the memory system, meaning that memories in this series use the same rules as the rest of illusion magic. I have another post going into detail about that, but TLDR: Illusions have an impact on real life in the same way that anything else can. They aren't representations of lies, but consequences. You can change yourself to match your true self, for example, but you need to understand what that means for everyone and everything around you.

So, memories associated with consequences? What a strange correlation, I wonder if that means anything.

You would think that the tragic memory would be of the bullying, right? A single moment crystalised into something awful, but what Willow wants to escape from, and what scares Amity the most, is the simple fact that these two used to be friends. It becomes a betrayal.

I think that the Inner Willow was a master stroke of the writing, because it gives agency to Willow's subconscious. It says the quiet things out loud in a way that Amity cannot get away from, and it is a creature that she will have to confront. It acts as a personification of consequence.

"Love, sadness, fear. I used to be a being made of all emotions. But ever since you set Willow's mind on fire, all I've been able to feel is anger."

There is a neat little double meaning here. Amity literally started burning Willow's memories of happiness accidentally, but she also did it figuratively a long time ago. The betrayal poisoned every other memory that Willow had of her and turned it sour, their relationship was shattered, perhaps permanently, and Willow suffered.

This actually links back to Galletto's Dark Souls. In the same passage where the mechanics are explained, Galletto gives this explanation:

"A Spark of Memory is something that keeps you human: funny thing is, they are rarely happy memories. Turns out pain, anger and regret take deep roots into our hearts, and the strength of these emotions can keep us going even when our body is broken"

Galletto isn't entirely false here, pain and suffering are powerful motivating forces, they can keep propelling you forwards. The Inner Willow would certainly agree with that sentiment. But I don't, and I don't think The Owl House as a whole, or even this episode, do either.

I mentioned above that gameplay displayed a contradicting view on powerful emotions, but Understanding Willow also argues this point. Anger is strong, don't get me wrong, but love can win out, and it does so through empathy. The thing that saves Willow in the end is Amity's declaration of understanding and desire to do better.

The strongest emotion that you will ever feel, is hope. Hope for a better tomorrow, hope for a better today, or hope that a relationship that you had thought doomed might be reconcilable. Hope will win out. Light, do not falter.

But, I said that this was an episode about Amity as well, and if you have seen this episode, you know exactly which scene I am going to talk about.

This scene pulls zero punches. From the fading away memories of young Amity and Willow to reveal their cynical, older selves; to the dialogue and the acting; to the construction of Amity's conversation with her parents. This is phenomenal.

This is the memory that started it all, this is the betrayal. Whoever did the expressions on the memories needs a prize because that is half of why this works so well. The other half of why this works is the lines, both what is said, and how it is delivered.

"I just... I just can't get the spells right"

"Well, yes. That... that is why. Because you're a weakling."

I keep saying this is a betrayal because it is. Friendships are built on trust and if that gets broken, good luck getting it back.

"Then you let your new friends pick on her, all because you thought she was weak."

It's important to understand what the Inner Willow is saying here. She's not complaining about the belittling or ambition, she's holding Amity accountable for her inaction. When Amity stood by and did nothing while Bosha bullied Willow, she was complicit in that bullying. Just because she didn't say anything doesn't make it any less her fault, for encouraging it by laughing, or by not standing up for Willow when she needed it.

Actions have consequences, but so does the choice to do nothing.

The camera pans back into the door and gives just a smidge of context, and there are some bold visual choices going on here.

First up, the limiting of the space makes amity feel boxed in and trapped, and it evokes a feeling of looking through a keyhole. You only see a fraction of what is going on, but it is enough to know what is happening.

Second, Amity is the only thing in colour here, meaning that she is still the centre point of the frame, despite being tiny.

Third, the Blights aren't shown in detail, only their shadows. It is their legacy that they leave behind on display, the shadows that they cast. But its also not the point. Showing the visual designs of the Blights would take away impact from what they are saying. This is a simple shot so that you understand exactly what is happening.

"Good children don't squabble, dear. Sever your ties with Willow, and if you don't..."

"Then we will."

Once again there is some reframing of Willow's life. Where Amity's betrayal tainted the memories of their times together, the Blights' words reframe everything after that point as out of her control.

"We'll make sure she never gets admitted into Hexide."

Amity is trying to protect Willow, and the actions that cause this episode's conflict become reframed as well. Amity wants Willow to forget her but doesn't comprehend how much of Willow's life was centred around her. She doesn't yet understand the consequences of her actions.

Final Thoughts

Willow and Amity are fascinating characters, and the depth that this episode brings to their actions and interactions sheds light on the series up to this point, and the series going forwards.

Willow has such a low level of self esteem that she is willing to hurt herself to support others, and this episode goes into why. But to that, I offer some advice. When I was researching this, I came across a motivational image by yogaspace.com. I had to search for the message's original source, which ended up being Penny Reid's Beard In Mind, but it reads as follows:

"Don’t set yourself on fire trying to keep others warm.”

Take from that what you will.

Next week, I will be looking at Enchanting Grom Fright, so stick around if you want my thoughts on that.

Previous - Next

#rants#literary analysis#literature analysis#character analysis#what's so special about...?#the owl house#toh#dark souls ttrpg#dark souls role playing game#bullying#amity blight#willow park#toh amity#toh willow#the owl house amity#the owl house willow#understanding willow#long post

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Firekeeper in ds3 is Gwyndolin from ds1

I know it sounds crazy but everyone's entitled to at least one insane fan theory and this is mine.

The Firekeeper in Darksouls 3 does not play by the same rules as firekeepers before her. She cannot die permanently, she does not leave behind a firekeeper's soul if killed, and she is able to exist even when the bonfire she keeps is unlit (even prompting you to light her bonfire when you first meet her).

It is also strange that we find a stray firekeeper's soul in the tower behind firelink shrine, one which takes a key sold at a high price by the shrine handmaiden. This tower also seems to hold the corpse of at least one other firekeeper.

When it comes to gwyndolin, it doesn’t make sense that she’d just fall ill out of nowhere. Even if she did, she is the god and leader of the darkmoon’s blades who server her every whim. Where she to fall ill, it does not make sense for them to abandon her in Anor Londo to get eaten by Aldritch, a known threat. Furthermore, it doesn’t really make sense that Gwyndolin would want to take over Anor Londo after she has confirmed Gwyn to be dead and the first flame to be linked. Gwyn treated her like shit her whole life and in Darksouls 1 it is no surprise that Gwyndolin would set up an elaborate smoke and mirror’s gambit to get her father killed and the age of gods extended.

That said, Gwyndolin does not draw her power from the sun like her father and sister do. Despite being called “Dark Sun” Gwyndolin, she draws her power from the moon and from darkness. We know that Gwyn is afraid of the power of the dark and very much wants to keep those who can harness it subservient or powerless. This is likely why Gwyndolin was given a moniker denoting her as part of the sun and why she was relegated to duties which kept her away from the public eye.

So, with all the background info out of the way, my basic headcannon goes like this:

After the events of Darksouls 1, Gwyndolin continues to run Anor Londo from the shadows for a time. When it comes time for a new undead to kindle the flame and no-one does so, Gwyndolin (knowing the emergency failsafe system will release Aldritch who she very much believes will be coming for her) creates a version of herself for Aldritch to eat and spreads the story that she has fallen ill as bait. (We know this to be within her power as she is both able to spread the chosen undead myth in DS1 and she is able to create a version of herself for us to fight, complete with a soul, without risking the illusions surrounding Anor Londo to all crumble at once upon her puppets defeat). Using this opportunity, she flees Anor Londo and replaces the firekeeper in Firelink Shrine. This lets her continue leading nameless undead into linking the flame and, because she is taking over the roll of firekeeper, it allows her to exist as a woman unquestionably (every firekeeper to date has been a woman). Like with linking the fire in ds1, this is a long-term goal and a personal goal of hers fulfilled at the same time.

So ye~

#dark souls#dark sousl 3#dark souls 3#dark sun gwyndolin#fire keeper#fan theory#speculation#headcanon#character analysis

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Problem with Lyra

Just to be clear, I think Dafne Keen is a terrific actor. This is in no way criticising her or her abilities. It’s more to do with the direction and the way her character was put together.

Adaptations of characters change according to the actor, or the vision the writer has i.e. There are different versions of Lizzie Bennet. I don't have a problem with a different vision of Lyra.

The problem I had was the Jack Thorne shaved away her prominent flaws - yet mentioned them at the same time. At the start, and throughout its mentioned that she's a liar, but we don't see it or rarely experience it. So when we do get moments where the storyline mentions that "she has to tell the truth", it doesn’t hit as hard as it should.

The whole concept in the 'Land of the Dead' sequence was her telling the dead true stories, but those story beats don't land as well because she's already truthful.

It was like the storyline wanted it both ways with her.

For example, comments that characters made in the show like "you are insufferable" "you don't apologise easily" or "LIAR" don't make sense because TV!Lyra is nothing like that.

And another thing, Lyra’s dislikable qualities are important to the story. 'His Dark Materials' is mostly driven by characters emotions and motivations rather than the plot. So things like, her lying, her selfishness, her rudeness even her EMOTIONS being toned down effects the entire story.

Lyra is first and fourmost an EMOTIONAL and impulsive person. She wears her heart on her sleeve. She doesn't filter herself. So her leaving Pan on the doc in the TV Show, kind of seems unnecessarily mean since we've never seen her do anything like that before. Which brings me to another point that I have.

Shaving away Lyra's flaws doesn't make her a kickass amazing character, it dehumanises her. I've seen this with other adaptations before. It presents a major problem that media has. "That women are just pawns to be pushed from one scene to the next. Their own agency never truly factoring in"

Lyra in the books undergoes through a massive character growth. Take her lying for example. She first lies to do wrong. She lies to save herself. She lies for good. Then she finally learns to tell the truth in the land of the dead. The whole irony of her being given the compass, is that it’s something that "tells her the truth".

So the TV show presented all these plot points to her, but none of the development or emotions to go with it.

So her character development is..I don't know really.

#had to get this off my chest#this is my only qualm with the series really#lyra belacqua#lyra silvertongue#bbc his dark materials#his dark materials#hbo his dark materials#tv show#analysis#critique#review#dafne keen#jack thorne#writing#they sucked out lyra's soul in this adaptation#which is ironic#really

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Am I the only one to have a video game art analysis todo list? Or am I too far beyond the geek nightmare border? I always come to it at some point and be like "I should make an essay of this." And then don't and come back "I really need this essay to prove some of my other points!" And STILL continue developing fragile arguments on a supposedly side-side project thing I started way too long ago.

Here it is btw:

Explain how the Stanley Parable establishes the definition of a video game.

How Dark Souls map design evolved with the psychology of the current age of each game.

The concept of Rapture in Bioshock and individual freedom to the extreme.

Bloodborne, every type of gore and what each expresses.

Every kind of death in Dark Souls and their meaning (it's not what it sounds like)

Outer Wilds, the breaking of conventions and the pinnacle of storytelling.

Some other lying here and there in the remnants of my mind.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

actually. and i’ll main tag this one. If anyone has any videos, essays, posts, analyses, etc about dark souls- any of the games, any subject, as long as it’s dark souls focused- that you like, send em my way. i want ‘em

#dark souls#fromsoftware#dark souls 2#dark souls 3#for context: i have a bigole analysis thing ive been sitting on for ages#and i want more points of view and different interpretations#and i mean it it can be about anything

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idk if this is a hot take anymore but I genuinely love and appreciate Anri of Astora and they’re one of my favorite characters from Dark Souls 3. They survived a horrific childhood and took up the sword, along with Horace, to make sure no one goes through what they went through again. Even when they lose Horace, their steadfast companion who’s been with them since the beginning, they venture on into Irithyll with the goal of finishing their quest once and for all. Depending on the player’s choice, they either become another pawn in service of Londor, quietly disappear, or, if you followed their questline and helped them defeat Aldrich, succeed at last. But with victory comes the inevitable fall - the purpose that was keeping them from going Hollow despite their past, despite losing their friend, despite every setback they experienced along the way, is finished. And with that, they either go to the grave near the Cleansing Chapel or the place where Horace went hollow and met his end to wait out their last moments, armed with nothing but a broken sword after giving their own sword to Ludleth to be granted to you. It is there where you exact mercy upon their hollowed form and grant them rest.

Also they’re genderfluid to me I don’t care that their gender changes to keep the marriage heterosexual

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I love about Dark Souls 1 is that it promotes growth from failure rather than success. It offers you a wide variety of options and paths and lets you find your own way through them. Most people start out very bad at Dark Souls, and you really do have to just keep trying and "get gud"

And thats kind of how it is in real life too. You grow from failing, and you reap from success.

Its not enough just to sow. You have to keep trying new things, getting better, and seeing what works. You cant reap without growing.

Try not to go hollow.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m currently working on a new project but while I get set up with it I’ll be studying the game design of dark souls! I’ll try to post a page of my analysis once in a while. Wish me luck :)

0 notes

Text

The Y-7 Psychopath - Cowardice or Humility

Don't know if anybody cares about some juvenile "media analysis" from me, but why not, especially on a idea I had in my mind, and finally think it is prudent to put it out there, to see how people feel about it.

So you know western cartoons? And Im not talking about "adult animated sitcoms" or the recent surge of "totally mature and bloody!!!" cartoons that in the end are the same juvenile superhero stuff lol just with exploding heads and awkward animated sex scenes lol.

Yeah, just the standard cartoons that people get really insecure about liking, and make video essays about how "actually it is a masterpiece of mature writting". But instead of me mocking this fact to try to hide my own anxiety over being somebody who makes a fanfic comic, lets go with this

So lets circle back to the title of this "essay" - and start with an example - Everybody loves Zuko from Avatar, I watched the show as a kid, you did, probably kids today do it when all their influencer idols force them too.

Perfect for exploring the point then: And that is the point, people claim how realistic and satisfieng Zuko's arc is, how the redemption is both earned and not without hurdles, not without fallbacks. So where is the issue?

Well I remember sometimes smugly thinking "Well what a coincidence that Zuko never actually on screen killed anyone so he never is really a bad guy...' And this I interpreted to be mostly the case of the rating - basically without the restriction the show would probably include Zuko killing what is at best combatants of the defending side or at worst even civilians. And this would probably kinda derail the arc or leave a bad taste in everybodys mouth...

But the question is left unanswered - is it at the end better, that Zuko gets redemeed in a way that is setup to leave out this elephant out of the room? Hell even I felt kinda weirded out about how nonchalant everyone was about the fact that Zuko hired an assassin, like it was kinda played off for laughs, but maybe that was to show "see we are redeeming him without writting out realistic evils like murder!" - still there is a difference between killing civilians and hiring some copyright free terminator.

So no answer? Well maybe lets look at the opposite case - anime, the cartoons that can kinda go away with showing unscreen murder and atrocities. And to bring it back, lets go with Soul Eater (and no manga spoiler this time cause Im generous and because this would open another can of worms, and I'll save that for the future)

Everybodys favorite charachter that gets reduced to one trait that ironically would be kinda problematic if one really was thinking about it in a certain way - Crona. Also know for killing people who were pointed out to be "not evil enough for it to be ok©®™"

So here we have this charachter, with a whole arc of being abused, having the famous trauma™, doing bad because of a parental figure and wanting to make that figure happy even if its in a twisted way, not getting what real love is...

Basically Im saying Zuko and Crona share a lot of simmilarities looked at this surface level. But only Crona has the problematic aspect of "mass murder". And even I kinda felt it being pushed under the rug no matter how I'll defend Crona from slander on the net while being sick both in body and soul lol.

But here is the thing - atleast I see Crona (atleast in the anime) as mostly some kind of child soldier - I dont think anybody thinks that some african boy that was forced at gunpoint to snort coke and kill his parents while being abused all his life, is "guilty" of the crimes in a way that an adult who does it for a less extreme reason.

Still, even if for me that is mostly justification enough (even if I kinda problematise the whole guilt thing in my comic), I still get it - even if explained it still leaves a bad aftertaste

Like even the most goodhearthed person would probably be weirded out if the person next to them would go "Thank God I was saved, cause till I was 14, I was forced to go from village to village and shoot everyone that moved!". One can say neither person is really at fault yet still it is a sticky topic.

And maybe thats where Im going with this - the problem isnt about depicting the redemption or whatever of killers, but if a story is mature and "deep" enough to handle it. So with my Avatar example I think that in a back handed way, it was good that Zuko wasnt a killer - becaue even if everybody loves the show (I mostly do to, shit was fun) - its kinda clear that in the end the writting and themes etc were on a level of a kid show - enough for kids, but not complex enough to actually deal with some things that other works could (and not even talking about something being grimdark or complex, cause nah everybody hates DBZ but that shit was so.good everybody felt Vegeta turning good and dont make essays about how bad that was, anyways that is why DBZ is too complicated for most western fans💅💅💅 ((but thats a topic for another day))

So to come back to the Crona question - was Soul Eater really prepared to deal with the topic of mass killing inocent people (mostly)? Especially when Ohkubo says himself that it was "a show where death isnt taken seriously"?

Cause I think, with Cronas struggle being mostly about abuse, doing bad things because of parental abandonment, fear etc, was it really necessary to add this baggage? Especially with a show that has that many visual metaphors?

And one example that I would use kinda proves my point and maybe implys that Ohkubo also kinda started backpedalling - the second time we see Crona, there are no wannabe gangsters, just souls of already killed people by another kishinegg which is just a wacky bad guy who isnt even really alive himself (and eve. comically survives)

Basically what I'm entertaining, is if wouldnt have been better to have Crona absorb souls that other Kishinseggs had collected, in this way preserving that they do something wrong (but reversible as later shown with the confiscation) yet never having to go to the extreme of "haha check out this wacky outfit our new friend Crona is wearing! Also twenty people were murdered in that church, shit was crazy"

But am I really basically saying 4kids Crona is the answer. Putting it this way lol, I dunno, I mean I like the pirate rap, but just sanitising everything seems off to me to. So yeah I dont even know.

And that is what leaves this whole question like the socratic dialogs, without any real answer with more confusion than before. But maybe it could "start a discussion" or whatever. But in case it was just a waste of time, without going anywhere:

Yeah... Sorry

Also quick manga spoilers as a bonus

This would aslo avoid making Cronas fate feel so cope-outish, cause that seemed to be the real reason - Ohkubo neither felt comfortable ignoring the whole message of overcoming fear and connecting no matter what, while also just saying that killing more people in Ukraine than in the last 2 years was just a big uppsie - hence the paradox of the non ending "I dont want to hurt. anybody, but actually I am evil.and care for Maka only or maybe Im just guiltu or maybe not and Im crazy xddd"

#media analysis#redemption#redemption arc#beyond redemption#killing#killer#murder in fiction#children stories with dark themes#meta#discussion#Soul Eater#crona#avatar the last airbender#Zuko#cop out#idk#any othet tags#you decide#Also Dbz is still king#one day I maybe explain#but you have to be from south america or eastern europe to truly get it#maybe the middle east to but not sure about the dub and time and age range it was shown too lol#also personally Im pro redemption if somebody is actually sorry#yes even the examples you come up with#but also purely theoretically cause Im a vindictive peace of shit and nearly couldnt forgive some old hag for screwing over a job prospect#lol#working on it#though#love everybody#turn the other cheek

5 notes

·

View notes