#classical music history

Text

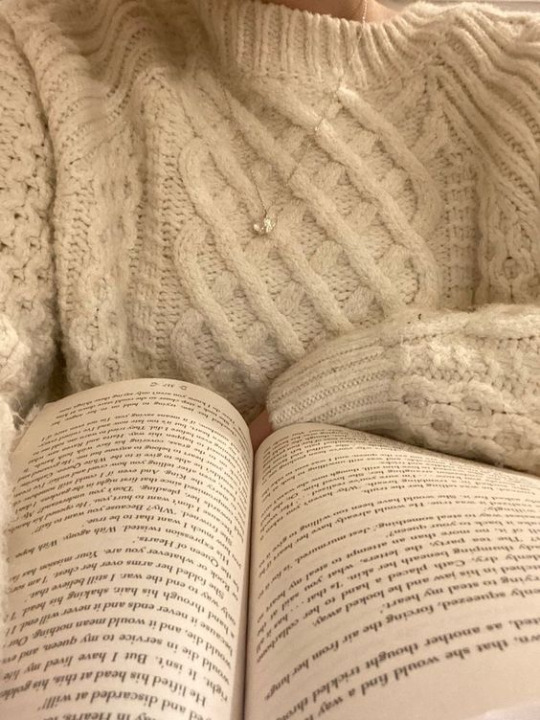

OKAY TUMBLR YOU'RE NOT READY FOR ISAAK GLIKMAN SIMPING FOR DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH. YOU HAVE TO SEE IT

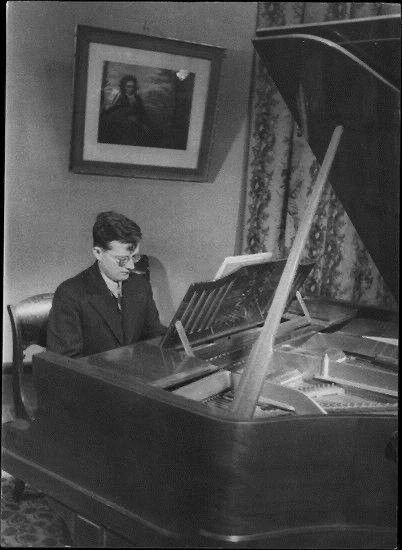

... so if you somehow don't know what shostakovich looks like

... all I'm saying is, he's not wrong.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#composer#classical composer#history#music history#classical music#classical music history#soviet history#goddd I'm such a simp

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

#that happened#maurice ravel#ravel#erik satie#satie#classical music memes#classical music history#music history#history memes#classical memes

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Produced, filmed and featured in a silly lil "(Un)hlepful Guide to Classical Music" for all my k-pop loving besties who are open to learning more about classical music.

Inspired by Cunk on Earth (& Between Two Ferns thanks to all the shade my friends threw at me).

Made in partnership with Apple Music Classical! Download for free here~ https://apple.co/ReactToTheK

#hiii guyyyssss#i'm a full time YTer now lol#but this is one of the first strictly classical music content ive made in a while#so posting about it here yay!#my acting is so cringe so be warned#classical music#omg horns#f horn#piano#music theory#kpop#reacttothek#classical music history#tchaikovsky#prokofiev#mussorgsky#uhhh#cunk on earth#between two ferns

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

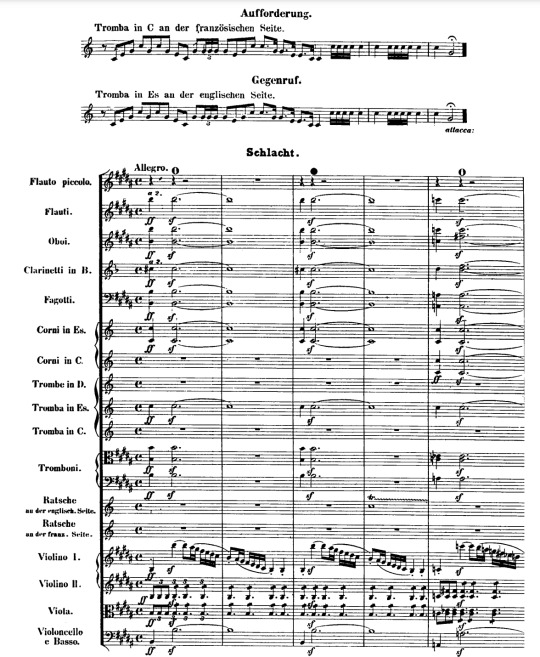

Comparing the intros to Eroica vs Wellingtons Sieg by Beethoven *fanboy screaming*

Inspired by @impetuous-impulse 's long-post essay on if Wellingtons Sieg was a certified banger or just liked because of its political ties. Very interesting, go read the post. Also literally don't worry about being socially awkward while interacting with me, my tumblr tag is literally diagnosed anxiety disorder, I understand if you get social anxiety in my notifs 😭

I'm going to put the post under a Keep reading so my mutuals don't get sieged with a wall of text on their dash ahaha

tldr: Wellingtons Sieg focuses more on imagery and takes a more cinematic/patriotic approach, sacrificing a bit of melodicism. While Eroica is very lyrical and musical, having a steady motif that it grows on, but I wouldn't know that it's about war if someone didn't tell me. Both pieces focus on different aspects of musicality and in their own domain, they perform quite well. I like Eroica more since it's more musical in my opinion, but Wellingtons Sieg is also really dramatic and cool. This is just my personal taste. I recommend listening to both and formulating your own opinion! Both pieces really do sound very Beethoven-esque though

ok coming at this from a musician's perspective and not a historical perspective (since there's plenty of you history buffs out there haha). I had to play a bit of Eroica for an orchestra audition and I just took the time to listening to a bit of Wellington's Victory and sight read the conductor's sheet music. I will now proceed to do a long post looking at the intros of Eroica and Wellingtons Sieg because I don't have the time to listen to both of them in their entirety right now

Just going to put it out there, Eroica and Wellingtons Sieg are both in Eb Major, which is practically known as the heroic key, but that's probably because of Beethoven. The only difference is that Wellingtons Sieg first starts in Eb, then goes to C major (bright and festive) then goes to B major (in this use it's similar in mood i think to C) and then it goes back to Eb.

First of all, I will tell you right now that I like Eroica more than Wellingtons Sieg. Not only am I biased but I've actually listened to Eroica in its entirety multiple times.

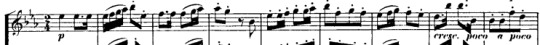

At the start of Wellingtons Sieg (after the dramatic snare drum and trumpet fanfare thingies) you have this nice cute little motif. The motif actually ends after the down beat in measure 8 but I wanted to include the crescendo poco a poco. Anyways, this is in Eb and it's backed up by a bunch of quarter note Eb's on the down beats as well. It's a simple melody and it kinda feels like a marching song honestly. During the whole crescendo part it kinda does a whole developmental twisty thingy with the motif and then lands on a forte and it ties it all together at the end with a small recapitulation of said motif. This whole intro just feels like the army marching into battle and whatnot.

Eb Major motif ^^^ I really like it! The staccatos and major key makes it feel very bouncy and lively

Then Beethoven decided that the army is not done marching actually and he's actually going to change the time signature entirely, giving the next upcoming C Major section an entirely different feel. In fact, an entirely different melodic motif, because it makes it ✨interesting✨. So after an even longer period of the snare drum going insane in a triplet-based time signature and then the trumpets follow up with their loud repeated notes since trumpets are good at doing that, then we have another motif!

C Major motif ^^^ (pretend like there's a quarter note C in the invisible measure 8, it was written on a different page so i had to cut off the resolution im sowwy) .

Similar to the first motif, it also has a light and bouncy feel with all the staccatos. The grace notes play a similar role as the 16th notes in the Eb motif as well. I mean, C is the 6th of the Eb major key, but I don't know enough music theory to know the significance of that :/ (im taking AP music theory next year though!!!). So this motif repeats itself a bunch of times in different modulations in 3rds (i think) while the violins either do nothing or echo the melody. Very big focus on the band, especially brass probably.

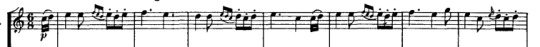

And then... we get into the part that is probably when the army actually reaches the battlefield. Now, we have our two soldiers right, the Eb motif and the C motif. These two soldiers were obviously on the front lines and got brutally one-shot killed by artillery or something because in the B major section there is literally no motif at all!!

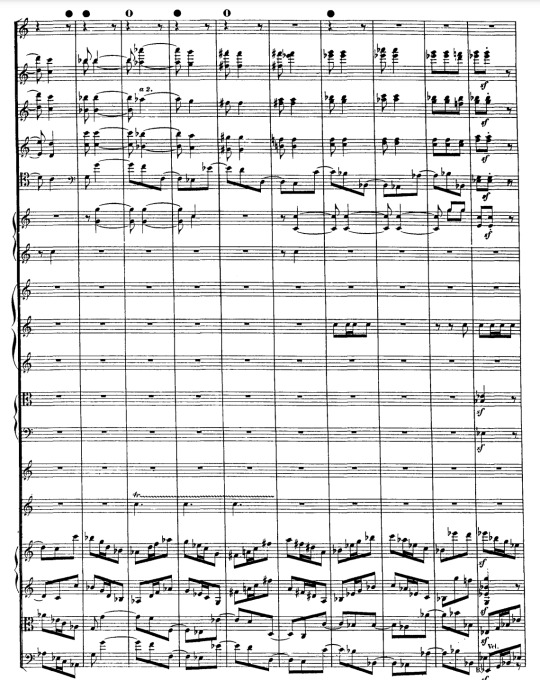

Ok, these two screenshots are 11 pages apart. Beethoven wanted to torture the violinists for a bit. He's literally doing what Wagner did for Ride of the Valkyries where he turns the violins into little Christmas ornaments and gives the brass section a field day. Moments like these are the reason why most of the violinists I know wish they picked the cello instead because wow look at all those juicy quarter notes and long notes ties, very chill. Also the second page that I screenshotted is when the key shifts from B major to Eb major. It's not written in the key signature but the accidentals suggest that the key is different because Beethoven wanted to make sure that no violinist was sight reading on the day of the concert, which is totally something I've never done before (haha... sorry maestro 💀)

I don't think you really need to read sheet music to understand what's going on. The winds are just holding long dramatic notes while the strings are having a stroke. This part of the piece is very cinematic and it very much sounds like the background music for a 1800s based war movie. A lot of times when pieces are based on.. uh... "things" they tend to ditch melodic lines for foley impressionistic sounds. There was this one concert I went to for my city's philharmonic orchestra and they played a piece based on Nazi Germany and they literally used two metronomes that were going off asynchronously as apart of the piece. I mean, the piece was very 1900s modern so... but that's the only example that's at the top of my mind right now.

What I'm trying to say is that there's no melody. Or at least there's no clear lyricism or melodic line that you can pinpoint, or there's no sense of melodicism that I can find with my mediocre knowledge of music theory and composition.

Overall, the intro of Wellingtons Sieg is very cinematic, in its sense that the musical lines paint a picture of the army marching to battle and then roughhousing it on the front lines in the section I just talked about. I really liked the motifs at the beginning, I hope Beethoven recapitulates on them at the end of the piece :(

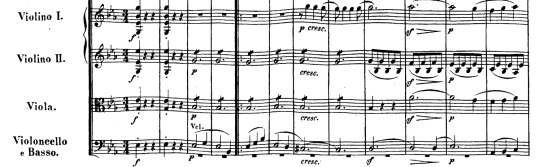

Alright onto Eroica– I love how it just jumps just straight into the theme after the grandiose entrance. I love the intro to this piece so much, the cellos have such a beautiful rich tone with the arpeggiated Eb 2nd inversion chord while the strings just have a bubbly metronomic portato touch, it's so satisfying. Then when the violin I's take over with the G to Ab dotted quarter notes and how it just leads into the next phrase. Then the end of the first motif is on the same beat as the repeat of said motif but the woodwinds play it instead, contrasting from the deep cello sound to a more free and gentle tone it's really beautiful.

Just listen to the Berlin Philharmoniker play it, they do such a good job with the phrasing and musicality. The Berlin Phil is one of if not the best orchestras out there in my opinion. Each section is so in time with each other it just sounds like a one person powerhouse from each instrument. I wish I can play in an orchestra even a fraction as well-refined as them one day. Nothing wrong with my school's orchestra, it's just aaaa Berlin Phil <333

I don't know where this happens in the sheet music, but after some developmental stuff building off of the Eb major chord motif that is juggled between the sections, the strings lead up to a tremolo-d Eb note and then the brass takes over and plays the Eb chord motif. It's so grandiose and probably sounds amazing live.

The melodic line moved from a soft but rich tone from the cellos to a calm interjection from the violins, sounding like a sigh that is carried on by the woodwinds. The woodwinds take their own artistic spin on the melody as the violins gradually crescendo in anticipation to the climax of the exposition. At the peak of the phrase, the brass section majestically explodes and sound goes everywhere and it's just... Beethoven. The piece feels like a really nice hug

With that being said, I kind of focused on two different things for the two pieces. Wellingtons Sieg tells a story through its music while Eroica is more melody based. Wellingtons Sieg does a great job on portraying a certain patriotic feel through its use of percussion and the brass section. It gets its point across that it is about a heroic war victory, listening to the piece is like watching the battle unfold in front of you. While Eroica, ah Eroica... it's majestic in itself. I don't know how else to describe it other than it really sounds like Beethoven. The way he stamps the epic Eb major motif all over the place and plays with the notes, always making it interesting, it's so nice to listen to.

These two symphonies are both musical in their own way. I believe these two symphonies were written roughly a decade apart, so a lot could've happened to Beethoven personally to influence how he sounds. Wellingtons Sieg definitely has its patriotic zeal thoroughly seasoned across the score while Beethoven's heart bled out on the pages of Eroica.

They're both beautiful in their own special Beethoven-esque way. I'm not historically educated enough to tell you what the audience of the time would prefer but what I think is the most important is to know your own opinion. Like how you don't read a book, the book reads you, music is interpreted differently for every pair of ears, or singular ear (not discriminating van Gogh). Music is for everyone, but at the same time, not for everyone. No matter the political introjections or emotional ties, art will always be art and will be seen differently by any audience. I think it's more important to just experience the music for yourself and figure out what you like.

Alright, this post is long enough. I'm not familiar with making long posts so I have no idea if I did this correctly ._. Thank you for reading this in its entirety if you did, I really appreciate it!

All this talk about Beethoven is making me want to relearn the Beethoven Sonatas I was working on on the piano and violin. Anyways, I gotta study for one of my final exams that is... uh... tomorrow.. and I totally studied for it hahaa.. ha... ... please wish me luck, I need it

ok, I'll shut up now, 再见

The End !

#ludwig van beethoven#classical music#wellington's victory#wellingtons sieg#eroica#eroica symphony#classical music history#music theory#music analysis#long post#ranting#symphony#eroica vs wellingtons sieg

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

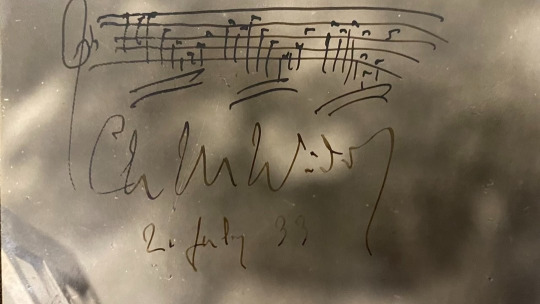

OTD in Music History: Notable French composer, organist, and pedagogue Charles-Marie Widor (1844 - 1937) dies in Paris.

As a composer, Widor wrote prolifically for organ, piano, voice, and various chamber and symphonic ensembles -- but he is undoubtedly most famous today for his ten solo "Organ Symphonies" (although it should be noted that he also wrote three *additional* Symphonies that were scored for *both organ and orchestra*). The glorious "Toccata" from the 5th Organ Symphony has become one of the most popular stand-alone works in the entire organ repertoire.

Widor also holds the title of longest-serving organist at the Church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, with a remarkable 63 year tenure that ran from 1870 to 1933. In January 1934, Widor was finally succeeded by his former student and assistant, Marcel Dupre (1886 - 1971)… who then held onto the position for nearly 40 years himself, thereby ensuring that it only changed hands *once* in the span of a century.

(Amazingly, Widor’s tenure was also only supposed to be an “interim” appointment!)

In addition to his service at Saint-Sulpice, for many years Widor also served as Professor of Organ and Composition at the Paris Conservatoire.

A fascinating 1932 recording of the 88 year old Widor performing his famous "Toccata" at Saint-Sulpice can be heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHEuwGSxUs0

PICTURED: A publicity photograph showing the elderly Widor seated before the organ in Saint-Sulpice.

Widor signed and dated this copy of the photograph to July 1933 -- just one year after he made the historic recording linked above, and five months before his retirement. He also penned the famous opening figuration from the "Toccata" above his signature.

#Charles-Marie Widor#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#organist#teacher#Romantic era#romantic period#Paris Conservatory#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#opera history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#classical music history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Bruckner – Symphony no.7 in E Major (1883)

Every now and then I see a composer described as “you love em or hate em”, and the longer I listen to classical music and see how people talk about it, the more I think this attitude can be used for any artist. Especially since extreme opinions are algorithmically given the most attention, and our way of communicating our tastes is equally encouraged toward extremes and hyperbolic language. Nothing can be “just” good, or ok, or interesting, or flawed; it’s either the best, or the worst thing ever. But maybe that attitude is more for Netflix shows or the latest Hollywood movie than for classical music.

Anton Bruckner didn’t escape this mentality despite living nearly two hundred years before the digital era began. When he was alive, the divisiveness in the public discourse was due to living and working in Vienna while loving Wagner. Side note on the “War of the Romantics”; on the aesthetic side there was the disagreement between developing traditional forms (the side of Brahms, C. Schumann, & supporters) versus letting new views on harmony and subject matter dictate how to structure music (Liszt, Wagner, & supporters). But there was another significant side that isn’t always focused on; being supportive of Jews, or being anti-Semitic. Not only was Wagner a musical radical in the way he conceived of opera, musical time, and harmonic development, but he was also a vocal anti-Semite, and his general dogmatic way of insisting on his views for every other subject was just as strong when it came to his bigotry against Jews. Supporting Wagner’s side of the ‘war of the Romantics’ didn’t only mean to support the new music aesthetics; it also implied that you were part of a growing movement of anti-Semitic German nationalism.

I only bring this up because I can assume that the hostility that Bruckner faced from the ‘conservative’ side of Vienna – including the ‘villain’ of Bruckner’s life story, music critic Eduard Hanslick – is more understandable if the stakes are higher and more consequential than “the music was too long and I don’t get it”. Despite his love for Wagner, Bruckner was more akin to the Wagner fans today who enjoy the music while ignoring or outwardly dismissing the evil side of Wagner’s art. I recall a story about Bruckner (one of the many stories used to talk about his ‘simple’ personality) where he had attended Gotterdammerung, and was enthralled by the music from beginning to end but asked “why did they burn her at the end?”. The music was more compelling to him than the content of the opera’s plot.

That could explain Bruckner’s musical aesthetic; taking after Beethoven’s 9th, focus on abstract music as the source of drama, but expand the use of harmonies, drama, and volume as if it were a Wagnarian opera. Its why, to me (and other fans), Bruckner’s symphonies feel like an emotional or spiritual journey despite being abstract music with no “meaning”. It also is why I’ve avoided writing and posting about Bruckner before. Like Mahler, it’s hard to capture the music in words and articulate how I feel about what’s happening in the music, but I’ve covered all of Mahler’s symphonies because I’d loved him a lot more than I did Bruckner. Only recently has my view of Bruckner warmed from “I like him sometimes if I’m in the mood” to “I love him and can’t get enough”.

Really by accident, or fate, I decided to listen to this symphony again two weeks ago, and Bruckner finally ‘clicked’ with me. I’d first heard him by picking up a few cds from my library, and putting him on in the background while I played old video games (in this case, Age of Empires 2). I thought he was epic, but hard to sit through and unless I was in a “Lord of the Rings” mood, I didn’t want to listen. A few weeks ago, Richard Atkinson came out with a video on Bruckner 6, which made me want to listen to him again. I decided to listen to the 7th again, and I finally connected with Bruckner’s soundworld.

One more note before going into the 7th; another reason Bruckner’s music was criticized in his life; it was for a relatively conservative orchestra where each section is noticeable. But that was because Bruckner was not trying to blend colors in an ‘orchestral’ way, but rather how one would write for the organ, which was his main instrument. So when we hear a Bruckner symphony, we are hearing the sounds he created for church services magnified through an orchestra, a kind of recreation of ‘sacred’ music but in a secularized context where one doesn’t have to think about any specific doctrine or view of the divine, instead you experience a sublime connection that is more uniquely ‘your own’. This is one example of how music was being treated as a replacement religion in Europe after the Enlightenment.

The opening movement of the 7th to me feels like a sunrise with the slow unveiling of the main melody. which rises in an arpeggio that evokes the drone prelude to Das Rhinegold. From this comes a seemingly endless melody that gradually develops with a group of themes played through. Long songlike melodies are rare for Bruckner’s opening movements – usually he uses motivic patterns – so the multiple distinct melodies in this work helped to give it the unofficial nickname “Lyric”. As the music builds tension we see another example of why some ‘hate’ Bruckner: intense build ups are created, but instead of climaxing they ‘stop’ and start over. After this first bursting episode, we get a dance-melody that, to me, sounds the most like “organ music”. Bruckner picks these melodies apart into his own way of development; counterpoint and modulation. In a way, bringing Bach and Schubert together. Every Bruckner opening movement ends with a grand coda where the music reaches its most extreme height, finally bringing us the climax we’d been denied by the previous build ups. Here it is only the first part of the opening melody, the rising arpeggio, over a long pedal point, and the volume and scope of the music rises with it into a transcendental glow of sound.

The adagio is the most famous movement of the work because it also has a long passionate melody, here in the minor and with darker colors from the use of Wagner tubas. Bruckner wrote this movement knowing that Wagner was dying, and it is like a musical memorial to him. That may sour the music for a lot of people, but it could be better to think of it as music in memorial of other music, for its own sake, and not for any toxic ideologies. This movement has two main melodies; a somber melody with unexpected modulations, and a bittersweet melody that tries to be uplifting. This movement is unique for a Bruckner symphony in having a cymbal clash, which was rumored to have been added to the score the moment Bruckner had heard the news of Wagner’s death. But that story isn’t true, the actual story is that a friend told him he should use a cymbal instead of a triangle for that moment. As usual, the more interesting ideas stick around to form a kind of mythos over music that we love.

The scherzo movement, again following Beethoven’s lead, is thunderous. The main melody is based on arpeggiated open fifths falling downward, and when the full orchestra blasts it, it feels like being under a cascading wave. Again, the writing is organ-like in the colors in the sections as they contrast each other like hands and feet over the keyboards and pedals. The trio makes me think of the kinds of ‘schmaltzy’ Viennese dances that would come up in Mahler’s symphonies, just one example of how Bruckner influenced Mahler’s style.

The last movement makes me think of the symphony as being symmetrical: the first half was made of two long movements, one bright and transcendent in the major, the other darker and tragic in the minor. The second half is made of two shorter and livelier movements that have the same major/minor characters. Here, the finale is a dance that opens with the violins playing the main melody, followed by a counter melody that’s more for rhythm than humming along. These ideas play in counterpoint in the winds until dying down in the strings, introducing a softer group of melodies. Later a large wave of unison octaves play out across the full orchestra, an inversion of the opening dance melody. This movement is in arch form, where the order of melody groups plays again in reverse order (1, 2, 3, 2, 1), though melodic ideas are used repeatedly, in the Bruckner fashion of breaking up motivic blocks. As with his other mature symphonies, the movement ends with another grand coda, where the arpeggio of the opening melody to the whole symphony returns, and reveals that the main theme of the final movement is based on this melody.

Movements:

Allegro moderato

Adagio: Sehr feierlicht und sehr langsam

Scherzo: Sehr schnell - Trio: Etwas langsame

Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell

#Bruckner#symphony#orchestra#classical#romantic#blog post#history#music history#classical music history#classical music#orchestra music#symphony orchestra#romantic music#romanticism#19th century music#Anton Bruckner#Bruckner symphony#Youtube#Happy Birthday

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

#dark academia#light academia#romantic academia#classic academia#dark academia aesthetic#dark academia vibes#dark academia music#academia#studyblr#light academia aesthetic#aesthetic#chaotic academia#literature academia#academia music#biblophile#poetry#tsh#the secret history

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

stevie nicks photographed by bob west, 1977.

#vintage#60s 70s 80s 90s#retro#history#classic rock#music#hollywood#vintage photography#vintage aesthetic#70s#stevie nicks#fleetwood mac#rockstar#groupie#hippie#girlfriend#1970s#stevie nicks aesthetic#hippie vibes#witch#i love this woman with my entire being#70s vintage#hippie style#witchy#stevie nicks style#MOTHER#she’s so cute#80s#silver springs

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jimi Hendrix, 29 April 1969, by Ed Thrasher.

#jimi hendrix#black tumblr#icons#black history#1960s#musicians#music#hey joe#black excellence#rock#black men#retro#style#hot celebs#fashion#black man#classic rock#hip hop#rap#cool#culture#👽

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gustave Jean Jacquet (French, 1846-1909) • The Cello Player • c. 1890 •

#art#painting#fine art#art history#gustave jean jacquet#french artist#student of bouguereau#classical painting#academicism#oil painting#portrait#female portrait#beautiful dresses in paintings#19th century european art#art blog#pagan sphinx art blog#art detail#art lovers on tumblr#musical instruments in artworks

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shostakovich-Sollertinsky letter translations (Russian to English)

So, I finally finished formatting my translations of the Shostakovich-Sollertinsky letters from a few years ago! These are letters from Shostakovich to his close friend, the polymath and scholar Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, from the late 1920s to 1943. They offer valuable insight on Shostakovich's opinions on subjects such as music, his personal life, and current events of the day.

The letters have been published in Russian and have also been translated and published in German; an official English translation does not exist as of posting this. I'm not a fluent Russian speaker and much of this was done with the help of a dictionary and the internet, but I believe I compiled a decent enough translation. I kinda had to rush the formatting towards the end, but it should be readable enough. Anyway, if anyone is interested, here it is!

For any Russian speakers who want to review my translations or would like to read the original letters, here is the PDF of the book.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#classical music#composers#classical composers#music history#classical music history#soviet history#soviet music history#translation#russian to english translation#russian history

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

some lesser known rachmaninoff facts?

Oh man. Idk where to even start lol

Once he went to a Russian bar in London with family and friends and the owner of the bar recognized him. The conversation went like:

"I think that you are Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninov."

"I'm very sorry, but that's not true," answered Rachmaninoff.

"Impossible... What a resemblance!"

"It’s a shame, I may look like him, but I don’t even know this man."

The owner then left him alone (not sure how convinced of this lie he was lol.)

I also find this story very funny:

Anecdotes from senar.ru

Many people today think of Rachmaninoff as an angry or irritated man, mainly because of his gloomy-looking pictures and some of his music, but in fact he was just shy!

#rachmaninoff#sergei rachmaninoff#rachmaninov#history#history facts#music history#classical music#classical music history#scherzina asks

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

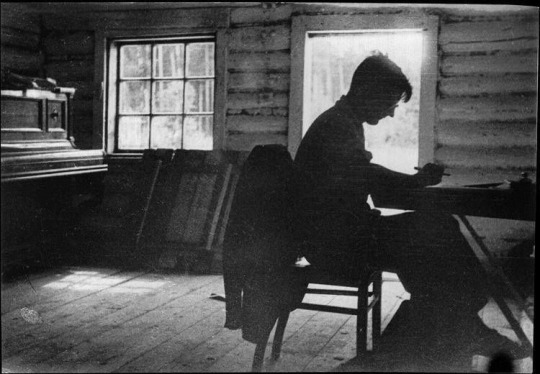

I love all the monochrome candid photos of Shostakovich, it really captures his essence well

#dmitri shostakovich#russian composer#classical music#classical music meme#classical music history#depressed russian composer whose early works are more happy than their later pieces

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTD in Music History: Jakob “Jacques” Offenbach (1819 – 1880) dies in Paris.

Offenbach is best remembered for two artistic achievements: First, for his pioneering work as the creator of a type of light burlesque French comic opera popularly known as “operetta,” which became one of the most characteristic "pop" musical products of the latter half of the 19th Century. Second, perhaps ironically, for his own masterpiece -- and one of only two operas he ever wrote that *wasn’t* an operetta -- “Les Contes d’Hoffmann” (“The Tales of Hoffmann”), a “grand opera” which remained unfinished at his death. (It was subsequently orchestrated and provided with recitatives and produced at the Opera-Comique in early 1881, where it proved to be a smash hit. It remains a part of the international operatic repertoire to this day.)

Offenbach combined a remarkably fluent and elegant musical style with a highly developed sense of both characterization and satire – indeed, no less an expert on matters of the theater than legendary "opera buffa" composer Giacchino Rossini (1792 - 1868) dubbed him “our little Mozart of the Champs-Elysees.” Offenbach produced his first full-length operetta, “Orphee aux enfers” (“Orpheus in the Underworld”) -- which features the (in)famous “Can-Can” dance -- in 1858, and it was perhaps the biggest hit of his career; it is certainly the most frequently performed of his many operettas today.

In many ways, both directly and indirectly, Offenbach can fairly be said to be the great-grandfather of the theatrical genre now commonly referred to as the “musical.”

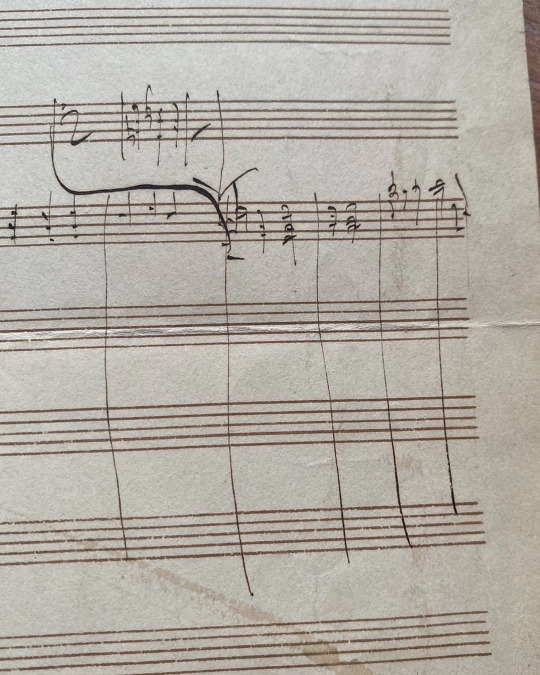

PICTURED: One of the many sheets of musical sketches written out by Offenbach over the years in connection with various projects (both realized and unrealized), which were then dispersed as "souvenirs" after his death. The completed work to which this particular sketch sheet is connected -- if any -- has not yet been identified.

#Jacques Offenbach#Orphée aux enfers#Romantic period#Les contes d'Hoffmann#Paris Conservatoire#Opéra-Comique#La belle Hélène#Operetta#composer#music history#classical music history

1 note

·

View note

Text

Frederick the Great Playing the Flute at Sanssouci by Adolph von Menzel, 1852.

#classic art#painting#adolph von menzel#german artist#19th century#realism#history#early modern period#frederick the great#people#musical instrument#concert#sanssouci#palatial interior

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

#dark academia#light academia#romantic academia#classic academia#dark academia aesthetic#dark academia vibes#dark academia music#academia#studyblr#light academia aesthetic#aesthetic#chaotic academia#literature academia#academia music#biblophile#poetry#tsh#the secret history

1K notes

·

View notes